Abstract

Context.

Emergency Departments (EDs) care for people at critical junctures in their illness trajectories, but Advanced Care Planning (ACP) seldom happens during ED visits. One barrier to incorporating patient goals into ED care may be locating ACP documents in the electronic health record (EHR).

Objectives.

To determine the ease and accuracy of locating ACP documentation in the EHR during an ED visit.

Methods.

Academic ED with 82,000 visits per year. The EHR system includes a Storyboard with the patient’s code status and a link to ACP documents. A real-time chart audit study was performed of ED patients who were either ≥65 years old or had a cancer diagnosis. Data elements included age, Emergency Severity Index, ACP document location(s) in the EHR, Storyboard accuracy, ED code status orders, and discussions of ACP or code status.

Results.

Of the 160 audited charts, 51 (32%) were for adults <65 years old with a cancer diagnosis. Code status was discussed and updated during the ED visit in 68% (n=108). ACP documents were found in 3 different EHR places. Only 30% (n=48) had ACP documents in the EHR, and of these (22%, n=13) were found in only one of the three EHR locations. The Storyboard was inaccurate for 5% (n=8). ED case managers frequently discussed APC documentation (78%, 43/55 charts).

Conclusions.

Even under optimal conditions with social work availability, ACP documents are lacking for ED patients. Multiple potential locations of ACP documents and inaccurate linkage to the Storyboard are potentially addressable barriers to ACP conversations.

Keywords: Advance care planning, palliative medicine, electronic health records, emergency department, quality improvement, healthcare power of attorney

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) consists of discussion and documentation of a patient's treatment preferences in the context of prognosis and quality of life. Legal documentation such as living wills, guardianship, or healthcare power of attorney forms along with documented advance care planning discussions are intended to guide clinicians to provide medical care consistent with a patient’s values, goals, and preferences during serious illness, especially in emergency situations.1 Prior studies have found that despite 50-60% of older adults endorsing completion of an ACP document, these documents are only present in the electronic health records (EHR) 4%–13% of the time.2,3 EHR documentation is also often difficult to access, inconsistent, or lost in the transition from home or nursing facility to the Emergency Department (ED).4,5 While confirming the presence of ACP documents and code status is only one of 8 steps in assessing and applying patient’s wishes, difficulties in finding ACP documentation could increase the risk of goal discordant care in time-sensitive settings such as the ED.6 Evaluating the EHR fits under the Health Systems pillar of advanced care planning.7 As part of a quality improvement program, we wished to evaluate facilitators and barriers to ED physicians reviewing ACP documents in real-time during ED care. Though ACP studies have produced mixed results, especially in quality of life and goal concordant care outcomes, there is evidence it is helpful in improving communication and is desired by both patients and surrogates as well as clinicians. Furthermore, even detractors feel that the identification of an appropriate surrogate decision-maker is vital for high-value end-of-life care.6 As the concept of ACP has broadened and evolved, the complexity of the ACP process has become apparent and considered a possible factor contributing the mixed results of previous studies. To help with this complexity, stakeholders and intervention targets within the ACP process have been identified. Some of these targets, including the health system, have been identified as under-targeted in previous ACP interventions and studies.7

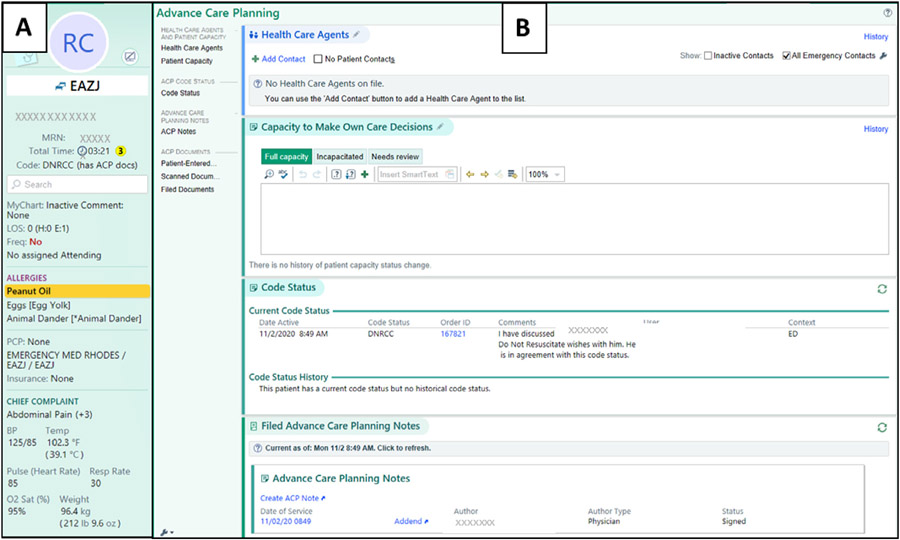

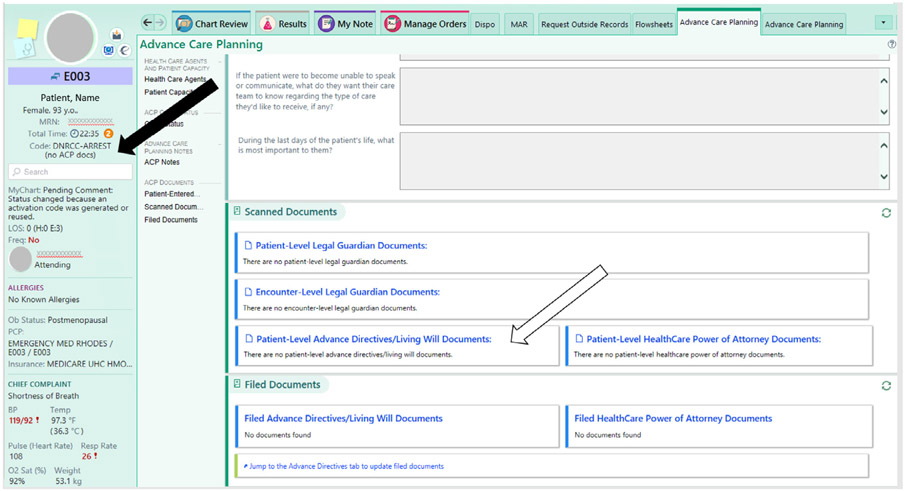

Our EHR launched a platform in May 2019 to improve access to ACP documents. This feature, called the Storyboard, states the presence or absence of scanned ACP documents and provides a direct link to them (Fig. 1). Scanned ACP documents include healthcare power of attorney paperwork and Ohio’s living will document. ACP information is collated on an ACP tab which displays all prior code status orders, uploaded ACP documents, and other contextual information such as ACP notes, health care agents, and medical decision-making capacity. Despite this attempt to streamline access, our team received anecdotal reports that the Storyboard could be incorrect. For example, ACP documents were in the EHR but not listed as present on the Storyboard, or vice versa (Fig. 2).We wished to determine the accuracy of the EHR Storyboard and its linkage to uploaded ACP documentation. Secondly, we wished to determine the proportion of patients with ACP documents and how often our healthcare team discussed/verified these documents and patient code status. This study was undertaken as part of a larger study of dissemination of ACP training and evaluation of potential IT tools to improve the identification of ED patients who would benefit from early palliative medicine interventions.8

Fig. 1.

The Storyboard (a) is a column on the left-hand side of the EPIC Electronic Health Record system that is displayed constantly and provides a quick view of the patient identifiers and current vital statistics. The patient’s last recorded code status and a link to advance care planning (ACP) documents are featured prominently under the patient’s name and medical record number, and clicking on these links to the Advance Care Planning tab (b). This page collates capacity assessments, code status orders, notes on goals of care or advance care planning, and ACP document links. Image from EPIC, © 2020 Epic Systems Corporation.

Fig. 2.

An example of Storyboard discordance (redacted), with the Storyboard listing, that the patient has no ACP documents scanned in (black arrow) and no documents are found under the ACP tab (white arrow). However, a living will from less than a year ago was found under the media tab by searching “living will.” Image from EPIC, © 2020 Epic Systems Corporation.

Methods

Setting

A tertiary care, academic ED with an annual volume of 82,000 patient visits, of which 15,000 have active cancer. Specialization includes a 15-bed oncology unit and the ED is Level 1 Geriatric Accredited. The ED has unit clerks to scan ACP documents brought in by patients and 24-hour social work and case manager coverage. Every patient with active cancer is evaluated by a specialized oncology social worker and case management team, and confirming ACP documentation is part of their standard assessment. Additional social workers and case managers for non-oncology patients are also available, but while trained and capable, ACP documentation is not part of their standard evaluation.

The EHR (EPIC, Verona, WI) includes a prominent Storyboard with the patient’s name, code status, and presence of ACP documents (Fig. 1). ACP documents are scanned in and tagged as Living Will, Health Care Power of Attorney, or Guardianship forms. The state in which this study was performed does not endorse Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST or POLST) forms. Healthcare providers can document a specific ACP discussion note in the EHR, but these notes also do not trigger a positive link to ACP documentations at the time of our study. Only the specifically tagged documents above triggered the Storyboard to say ACP documentation was present.

Population

A convenience sample of consecutive ED patients roomed for ≥4 hours who were either 1) ≥65 years old and/or 2) had a cancer diagnosis at any stage. The length of stay criteria was to ensure that the patients had a serious medical issue requiring significant emergency care and to allow the ED team time to obtain and scan any available ACP documentation. This was not expected to limit our patient population significantly as the median length of stay for discharged patients is 4.75 hours. We did not limit inclusion to only admitted patients as disposition should not change whether or not the documentation was accessible in the EHR and because our goal was to focus on real-time accessibility for any ED patient.

Methods

This was a process improvement activity exempt from institutional review board review. The data were approved for release by the institution’s Quality and Patient Safety Committee. The release of EHR images was approved by EPIC. Auditors were non-physicians with prior experience in quality audits and chart reviews. A standardized audit sheet was created with defined data variables. The auditors completed one hour of training consisting of reviewing charts simultaneously to develop accuracy and consistency in data extraction. Only one auditor was assigned per day to avoid double auditing. Charts were audited in real-time during the ED visit to simulate the ED physicians’ ability to access the data. Study times were weekdays in June 2019 during business hours to ensure that every relevant serviceable to improve accessibility to ACP documentation would be available (e.g., ability to call extended care facilities or contact medical records at transferring institutions). Because this study evaluated real-time availability, retrospective quality checks were not feasible.

Data elements included patient age, triage Emergency Severity Index (ESI, range 1–5 with level 1 being the most severe illness), where and when ACP documents were scanned and found in the EHR, the accuracy of the Storyboard, presence of a case management or social work note and whether this note addressed ACP documentation. Notes were categorized as addressing ACP if the text specifically mentioned discussing, uploading, or confirming ACP documents. Per State of Ohio DNR rules, code status in our EHR is categorized as Full Code, Do Not Resuscitate Comfort Care-Arrest (DNR-CCA, where the patient will receive all disease directed therapy up until an arrest occurs when comfort care will be initiated), Do Not Resuscitate Comfort Care (DNR-CC, where comfort care is employed exclusively even prior to arrest), and unknown. Which status was ordered and when (this visit, prior ED visit, or prior hospitalization) was recorded?

Result

Of the 160 audited charts, 51 (32%) were for adults <65 years old with a cancer diagnosis (Table 1). Average ESI was 2.5 (range 2–4). Mean age was 66.1 years and ranged 22–94 years old. ACP documents were found in three EHR locations: 1) Demographics tab under Advance Directives, 2) ACP tab, and 3) Media tab (an area for scanned-in documents and photos). The ACP tab included the following categories of documents: Advance Directives/Living Will, Healthcare Power of Attorney, and Guardianship forms.

Table 1.

Presence of Advance Care Planning (ACP) Documentation in the Electronic Health Record (EHR) of Adults in the Emergency Department at Higher Risk for Need for Goals of care Discussions

| Total cohort (n=160) | Age <65 with cancer cohort (n=51) | Age ≥65 yrs cohort (n=109) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESI | 2.48 | 2.46 | 2.50 |

| ACP label in EHR Storyboard accurate | 95% (n=152) | 98.0% (n=50) | 93.6% (n=102) |

| ACP documents in the EHR | 30.0% (n=48) | 23% (n=12) | 33.0% (n=36) |

| Code status discussed or changed | 68% (n=108) | 63.3% (n=69) |

Abbrevations: yrs = years; ESI = Emergency Severity Index; ACP = Advance Care Planning; HER = Electronic Health Record.

Overall, the accuracy of the Storyboard was 95% (8 charts found in error) with the majority of errors (6 of the 8) were when the Storyboard listed no ACP documents but they were found in one of the three locations. Only 30% (n=48) of patients had ACP documents in the EHR, and this differed insignificantly between the subgroup of adults age <65 years with cancer and those age ≥65 (23% vs. 33%, P=0.22). Of those with ACP documents, a fifth (22%, n=13) had documents found in only one of the three EHR locations.

In regards to code status, 68% (n=108) had narrative documentation of a discussion of code status or an updated code status order placed during the ED visit. Ten percent (n=16) had no code status documented ever in the system, and the remaining 22% (n=36) had a prior code status order in the EHR that was not confirmed or updated during the ED visit. The social work and case management team met with 34% (n=55) of the patients. These team members were large drivers of exploring the presence of ACP documentation, as 78% (43/55) of social work or case management notes documented a discussion of ACP documents.

Discussion

Our quality audit of the real-time availability and ease of locating ACP documents during an ED visit found that 70% of patients did not have ACP documents in the EHR. This is consistent with prior studies that also identified a lack of ACP documentation during hospital admissions (80%–96%).2,9,10 This is interesting because the rates of ACP planning in community practice settings are reportedly higher: 33%–50% and up to 43%–71% in clinical trials of ACP interventions.3,4,11,12 This discordance between what is discussed in the community and what is available to physicians upon hospitalization or during the ED visit is likely multifactorial. Our data points to EHR systems as one factor that may be amenable to intervention. Making these documents easily accessible to the people who need them during acute care events to support goal concordant care is essential. In addition, nearly 75% of physicians cite EHR systems as contributing to their feelings of burnout.17 Frustration with needing to search the EHR for necessary advanced care planning documents during a critical patient encounter and navigating inaccurate labeling could certainly contribute to this in ED providers.

How can discordances in the EHR’s presentation of ACP documents be fixed? Many of the patients with documents available only had them in 1 of 3 places in the EHR, which could result in physicians not being able to find them. This supports findings from a 2013 study evaluating the ease of finding ACP documents in a primary care clinic. In that system, ACP documents could end up in a progress note, problem list, or as a scanned document.13 Some of this inconsistency may be due to legacy categorization not recognized by more recent software updates. Some are also likely due to human factors, such as staff labeling scanned documents incorrectly. In our auditing, we found that documents not properly labeled as “Living Will,” “Healthcare Power of Attorney” or “Guardianship” were not interpreted by the EHR as ACP documentation and subsequently not pulled through to all three locations. For this quality improvement project, ED social workers, case managers, and registration personnel were educated to address this problem.

Other potential interventions for improving ACP documentation are centralizing these documents across different EHRs and leveraging the patient’s abilities to contribute to their medical record.14 Most EHRs now have patient portals which allow patients to upload ACP documents to their medical charts. This study did not look into that feature, but it may be a helpful way to increase access to these documents. Educating patients on how to do this may be difficult in the ED setting, but could be done by ED social workers or promoted in other clinical settings.

This audit was designed to give a best-case scenario: daytime hours, a tertiary care ED with available case management and social work teams, and a patient population that is at a higher likelihood of having ACPs (older adults and those with cancer). Our audit suggests that documenting code status even in ideal situations is still low, as a third of patients did not have their code status listed or confirmed. Prior studies have found that a patient’s code status changes the options provided and care initiated for the patient and also could change disposition.15 For example, an ACP discussion could change a patient with symptomatic choledocolithiasis (gallstones) from an aggressive approach of admission for cholecystectomy to a conservative approach of discharge with pain and nausea medication. Limiting studies of ACP discussions to admitted patients only excludes patients whose care planning priorities result in different dispositions. One strength of this study is that we evaluated ED patients regardless of disposition status. One limitation to this approach is that we cannot estimate the impact that EHR issues have on admitted patients.

As of 2021, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services criteria do not adjust for patient wishes and code status at time of admission, but studies have found that initial code status greatly affects hospital rankings. Excluding patients that had a DNR-CC or DNR-CCA order upon admission would change 70% of hospitals’ mortality quality rating deciles.16 Therefore hospitals may soon be incentivized to improve access to ACP documentation and to train their providers in ACP discussions.

Limitations of this study include a small sample size compared to overall ED volume. Additionally, given the variability of labeling and locations within the EHR that documentation can be found, there could be instances where ACP documentation was available but wasn’t found by the study auditors. However, neither of these issues limit our main conclusions. One strength of our methodology was in the study’s inclusion criteria. We audited patients with an ED length of stay of ≥4 hours, which ensures that the patients had, at minimum, moderately complex problems that took hours to address in the ED. Low complexity patients with short stays were presumed to be a lower yield population for ACP discussions.

In conclusion, this quality assessment of real-time accessibility of ACP documents and code status in ED patients with cancer or older age found that despite optimal conditions, the majority of patients lacked ACP documents, and those that were available were often difficult to find in the EHR. Further efforts to improve communication of ACP documents to ED physicians are needed.

Key Message.

Real-time chart audits during Emergency Department visits simulated physicians finding advanced care planning (ACP) documents. In a high-risk population, only 30% had ACP documents uploaded in the electronic health records (EHR), and these were difficult to find in 22% of cases. Improved communication of ACP documents is needed.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory by cooperative agreement UG3AT009844 from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, and the National Institute on Aging. This work also received logistical and technical support from the NIH Collaboratory Coordinating Center through cooperative agreement U24AT009676. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Presentations

This was presented as an abstract at the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting, Denver, Colorado, May 2020.

Contributor Information

Olivia Pyles, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Christopher M. Hritz, Division of Palliative Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Peg Gulker, Department of Emergency Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio USA.

Jansi D. Straveler, Clinical Analytics, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, Ohio USA.

Corita R. Grudzen, Ronald O. Perelman Department of Emergency Medicine, New York University School of Medicine, Department of Population Health, New York, New York, USA.

Lauren T. Southerland, Department of Emergency Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio USA.

References

- 1.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331. :821–32.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grudzen CR, Buonocore P, Steinberg J, et al. Concordance of advance care plans with Inpatient directives in the electronic medical record for older patients admitted from the Emergency Department. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:647–651. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Platts-Mills TF, Richmond NL, LeFebvre EM, et al. Availability of advance care planning documentation for older emergency department patients: a Cross-Sectional Study. J Palliat Med 2017;20:74–78. 10.1089/jpm.2016.0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker E, McMahan R, Barnes D, et al. Advance care planning documentation practices and accessibility in the electronic health record: implications for patient safety. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:256–264. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McQuown CM, Frey JA, Amireh A, Chaudhary A. Transfer of DNR orders to the ED from extended care facilities. Am J Emerg Med 2017;35:983–985. 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison RS, Meier DE, Arnold RM. What's wrong with advance care planning? JAMA 2021;326:1575–1576. 10.1001/jama.2021.16430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMahan RD, Tellez I, Sudore RL. Deconstructing the complexities of advance care planning outcomes: what do we know and where do we go? A Scoping Review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69:234–244. 10.1111/jgs.16801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grndzen CR, Brody AA, Chung FR, et al. Primary Palliative Care for Emergency Medicine (PRIM-ER): protocol for a pragmatic, cluster-randomised, stepped wedge design to test the effectiveness of primary palliative care education, training and technical support for emergency medicine. BMJ Open 2019;9: e030099. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinerman AS, Dhalla IA, Kiss A, et al. Frequency and clinical relevance of inconsistent code status documentation. J Hosp Med 2015;10:491–496. 10.1002/jhm.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins SA, Bentley A, Phillips V, Barclay S. Advance care plans and hospitalized frail older adults: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020;10:164–174. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis JR, Downey L, Back AL, et al. Effect of a patient and clinician communication-priming intervention on patient-reported goals-of-care discussions between patients with serious illness and clinicians: a randomized clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:930–940. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudore RL, Schillinger D, Katen MT, et al. Engaging diverse english- and spanish-speaking older adults in advance care planning: The PREPARE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1616–1625. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson CJ, Newman J, Tapper S, et al. Multiple locations of advance care planning documentation in an electronic health record: are they easy to find? J Palliat Med 2013;16:1089–1094. 10.1089/jpm.2012.0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver MS, Anderson B, Cole A, Lyon ME. Documentation of advance directives and code status in electronic medical records to honor goals of care. J Palliat Care 2019. 10.1177/0825859719860129. 825859719860129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neufeld MY, Sarkar B, Wiener RS, Stevenson EK, Narsule CK. The effect of patient code status on surgical resident decision making: a national survey of general surgery residents. Surgery 2020;167:292–297. 10.1016/j.surg.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuller R, Hughes J. DNR orders known at the time of admission can improve hospital mortality ratings. Health Serv Res 2020;55:96. 10.1111/1475-6773.13466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]