Abstract

Precise and selective manipulation of colloids and biological cells has long been motivated by applications in materials science, physics and the life sciences. Here we introduce our harmonic acoustics for a non-contact, dynamic, selective (HANDS) particle manipulation platform, which enables the reversible assembly of colloidal crystals or cells via the modulation of acoustic trapping positions with subwavelength resolution. We compose Fourier-synthesized harmonic waves to create soft acoustic lattices and colloidal crystals without using surface treatment or modifying their material properties. We have achieved active control of the lattice constant to dynamically modulate the interparticle distance in a high-throughput (>100 pairs), precise, selective and reversible manner. Furthermore, we apply this HANDS platform to quantify the intercellular adhesion forces among various cancer cell lines. Our biocompatible HANDS platform provides a highly versatile particle manipulation method that can handle soft matter and measure the interaction forces between living cells with high sensitivity.

The ability to assemble colloidal particles with well-controlled shapes and material properties1-10 has been studied as an excellent model for exploring how matter organizes in materials science1,2, condensed-matter physics3,6 and biophysics11. Unlike nanoparticles, microscale particles cannot easily self-assemble into high-quality crystals1. To direct the colloidal assembly of microscale particles, various methods including the use of specific surface functionalities5, such as DNA linkers and attractive ‘patches’1, different liquid solvents10, complex anisotropic particles6 or the modification of colloids using phototactic7, electric8 and magnetic9 mechanisms, have been reported. However, these approaches possess challenges, such as synthetic difficulties associated with specific colloidal shapes1 or materials5, poor control and tunability of interactions1,6, and can be ultra-difficult to generalize. Additionally, these colloid manipulation approaches5-10 cannot be directly applied to cell manipulation applications to understand cell–cell interactions or build ordered biological structures. Thus, a more versatile method that can precisely manipulate both colloid materials and cells, without any surface treatment or modification of the particles’ material properties, into desired formations is needed and has not been previously reported.

Acoustic tweezers, the acoustic analogue of the optical tweezers11, eliminate the need for optical tables, high-powered lasers and complicated and time-consuming optical alignment, and offer a contact-free, highly biocompatible approach for performing particle manipulation. However, current standing wave-based acoustic tweezers12,13 and the recently developed acoustic force spectroscopy method14,15 can only trap and manipulate particles as a group, limiting their ability to control individual particles for precise colloidal assembly selectively. To overcome this limitation, phased array transducers16 and acoustic hologram17 methods have been developed to manipulate millimetre-scale particles individually. However, these methods cannot be used to select single cells (roughly 10 μm diameter) or micrometre-scale colloidal particles due to their millimetre-level spatial resolution. Additionally, all the methods above, either by adjusting the phase16,18,19 or by moving the transducer20, have difficulty with the precise assembly of colloidal matter and with reversible cell–cell pairing and separation due to the steady-state nature of the acoustic wavefield12,21 and/or the imprecision of acoustic streaming22,23 or vortex generation24.

Herein, we present HANDS particle manipulation. Different from applications in the quantum field25-28, such as delicate nanomechanical waveform generation27,28 by harmonic acoustics for photon emission in solid-state, we applied time-effective Fourier-synthesized harmonics to achieve HANDS manipulation for the generation of reconfigurable acoustic lattices and spatial control of particles and cells suspended in liquid (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). With the gentle and dexterous HANDS platform, we have achieved the formation, reconfiguration and precise rotational control of colloidal crystals or soft condensed matter (Fig. 1b, top). We can also actively control the lattice constant (Fig. 1b, bottom) by the frequency or amplitude modulation of multi-harmonic waves (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 2) to pair two target cells selectively with tuneable intercellular distances (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Video 1) or collectively manipulate an array of colloidal clusters or cells (Fig. 1e). We can control cells with more than 100 pairs in a suspension for reversible pairing and separation in a high-throughput, precise, programmable and repeatable (>1,000 cycles) manner, all of which are challenging for using existing colloid assembly5-10 or single-cell manipulation methods29-33.

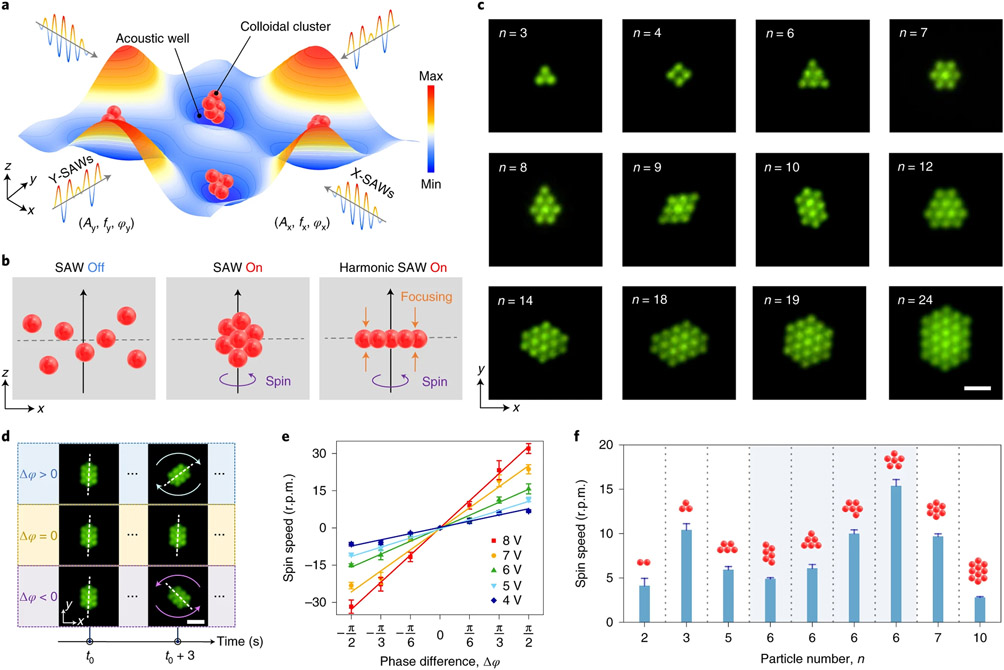

Fig. 1 ∣. Fourier synthesis of harmonic acoustic waves of HANDS to create soft flexible lattices for colloidal crystals or cell–cell pairing and separation.

a, Schematic of HANDS manipulation with Fourier-synthesized harmonic acoustic waves. b, Top, a colloidal crystal with controllable particle numbers and conformation can be assembled. Bottom, large area patterning with a tuneable lattice constant can be generated for colloidal clusters or single cells. c, The modulation of frequency and amplitude of harmonic waves can generate soft lattices and reconfigurable colloidal crystal or tuneable patterning of single particles or cells. d, Fluorescent imaging showing selective pairing of two U937 cells among six cells by localized modulation of the intercellular distance. The positions of the cells are indicated by the fluorescent intensity profile (averaged from five cell groups). Scale bars, 10 μm. e, Comparison of two patterned colloidal clusters with equal trapping spacing and tuneable trapping spacings, as analytically simulated and experimentally generated using HANDS manipulation. Colloidal clusters are formed with 2 μm fluorescent polystyrene particles in each trapping acoustic wells. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Results

Assembly and dynamic control of colloidal crystals.

This dexterous HANDS platform assembled colloidal crystal monolayers with high precision and dynamic rotational control. As shown in Fig. 2a, the three-dimensional (3D) colloidal crystal assembly can be formed in acoustic wells by applying standing surface acoustic waves (SAWs) in both the x and y directions. Here, acoustic wells are acoustic potential fields established in a fluidic medium. Where the acoustic radiation force is a minimum, this location functions as a node for trapping objects12. The colloidal assemblies are vertically focused by switching from the standing SAWs to time-effective Fourier-synthesized harmonic SAWs (Supplementary Fig. 1), and we can create a two-dimensional (2D) colloidal crystal monolayer from the initial cluster of trapped microparticles (Fig. 2b). With HANDS manipulation, we directly formed numerous colloidal crystal monolayers using 2-μm diameter polystyrene particles (Fig. 2c). By tuning the frequencies and amplitudes of the five-component harmonic SAWs (such as f2 to f6 illustrated in Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 2), the shapes and sizes of the harmonic acoustic wells can be modulated, which enables the generation of diverse crystal monolayers with different numbers of particles. Due to the secondary acoustic radiation forces generated by the scattering of the acoustic field between the particles3, the monolayer assemblies can be stabilized as close-packed colloidal crystals. HANDS manipulation can also spin the entire colloidal crystal assembly by applying a phase difference (Δϕ = ϕx − ϕy) between the x and y direction harmonic SAWs. This acoustic-induced rotation allows us to create various colloidal crystals from the initial cluster by further shaping the colloidal assemblies with the stabilized monolayer patterns (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Video 2). Additionally, the rotational direction of an assembly can be easily tuned by changing the phase difference of the applied harmonic SAWs. As illustrated in Fig. 2d and Supplementary Video 3, a positive phase difference (Δϕ > 0) results in a clockwise rotation and a negative phase difference (Δϕ < 0) causes a counterclockwise rotation for a ten-particle cluster monolayer. After the further quantitative study, we demonstrated that the rotational speed of the colloidal assembly is linear with respect to the phase difference, and this speed can be proportionally tuned by varying the amplitudes of the applied excitations (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2 ∣. Creation of colloid crystal monolayers with cluster and spin dynamics studies via HANDS manipulation.

a, Schematic of colloidal clusters being trapped in acoustic wells by applying SAWs in the x and y directions. b, Illustration of the generation of colloidal crystal monolayer by vertical focusing of particles with applied harmonic SAWs. c, Fluorescent imaging of colloidal crystal monolayers using 2 μm polystyrene particles formed by HANDS manipulation. Scale bar, 5 μm. d, Illustration of the spin directions, controlled by the phase difference (Δϕ = ϕx − ϕy) between X-SAWs and Y-SAWs. Scale bar, 5 μm. e, Characterization of the spin speed as a function of the phase difference at different excitation signal amplitudes ranging from 4 to 8 V. f, Comparison of the spin speed of colloidal crystal monolayers with different particle numbers and configurations.

Next, we investigated the spin speed of the colloidal monolayers with different numbers of particles (from n = 2 to n = 10) and configurations (four monolayer configurations with n = 6). Under the same excitation, we observed that the spin speed of the assemblies is strongly correlated with the colloidal crystal configurations rather than with the particle numbers. As shown in Fig. 2f and Supplementary Video 4, for all the investigated different configurations of six-particle clusters, the highest spin speed is achieved by a flower-shaped arrangement with the rotational symmetry of order five. This observation suggests that clusters with higher orders of rotational symmetry tend to have a faster spin speed. It also demonstrates the capability of HANDS manipulation for different crystal configurations of the colloidal crystal monolayer by varying the spin speeds. With this capability for precise particle assembly, we can use HANDS manipulation to explore the fundamental soft condensed-matter physics behind colloidal interactions and assembly.

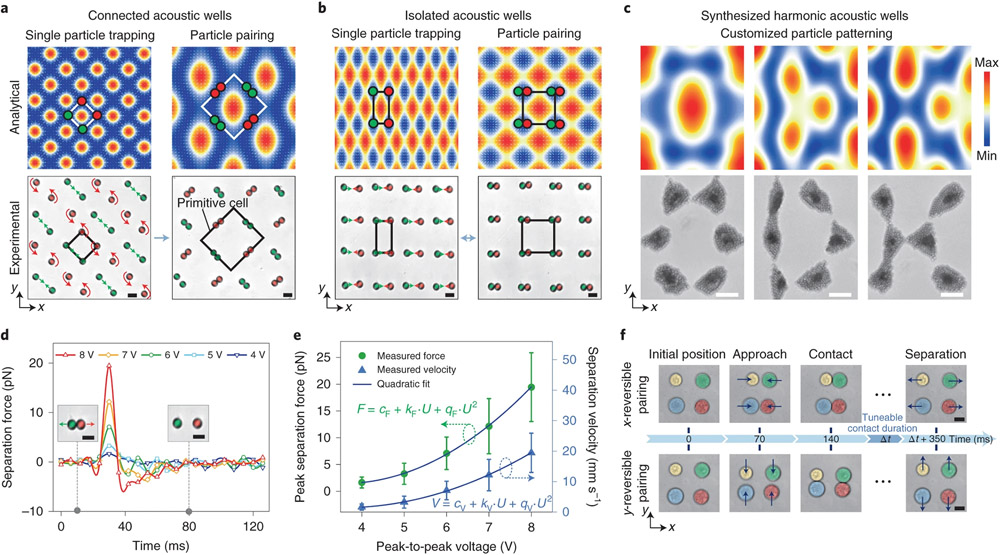

Reversible pairing and separation of single colloids.

In addition to dynamic rotational control of close-packed colloidal crystals, we can also dynamically modulate the distance between individual colloids or cells with subwavelength manipulation resolution. This subwavelength manipulation resolution is achieved with a time-effective Fourier-synthesized acoustic potential field (see Supplementary Notes 1 and 2 for further details) that was realized by sequentially applying nanosecond pulsing of SAWs, f1 and f2, with a time-division multiplexing method (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b) during a period T. By modulating the time-division Δt1, Δt2 and their ratio κ, spectrum trapping occurs (Supplementary Fig. 1c) and enables positional tuning to precisely manipulate objects in a half-wavelength range of applied SAWs. On the basis of our analytical simulations (Supplementary Fig. 1d), this spectrum trapping method can provide spatial control with nanometre precision. By shaping the acoustic potential field on demand34,35, we can actively control the configuration of an acoustic-well array. As shown in Fig. 3a, a mesh-like arrangement of connected acoustic wells can be generated by using the same frequency to excite standing SAWs in the x and y directions. By switching from the second harmonic () to base () frequencies, the lattice constant of the acoustic-well array changed from (√2/4)λ1 to (√2/2)λ1, causing the reconfiguration of the pattern from single-colloid trapping (Fig. 3a, left) to pair (Fig. 3a, right and Supplementary Video 5). Specifically, at higher harmonics, each colloid occupies an acoustic well. However, the number of acoustic wells is reduced with a decrease in frequency, which forces the colloids to settle the same acoustic well at lower harmonics. When using harmonics () in the x direction that are slightly shifted from the harmonics () in the y direction, a dot-like array of isolated acoustic wells can form a uniform rectangular pattern that enables repeatable switching between trapping of a single colloid (Fig. 3b, left) and pairing (Fig. 3b, right). Notably, via dynamic switching among nanosecond pulsing harmonics, a time-effective Fourier-synthesized acoustic potential field can be formed (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, the generated harmonic acoustic wells can be programmed with tuneable sizes and spacings between neighbouring wells. To demonstrate the dynamic patterning capability of HANDS manipulation, we created customized colloid patterns that form the shapes of the letters, ‘O’, ‘D’ and ‘K’, respectively, via modulating the five-component harmonic SAWs (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 3 ∣. HANDS for manipulation of soft matter and living cells for precision quantitative measurements.

a,b, Analytical simulations and experimental results for single-colloid trapping and pairing with connected (a) and isolated (b) acoustic wells for colloidal particles (9.51 μm). The green and red arrows indicate the directions of the acoustic radiation forces. Scale bar, 10 μm. c, Analytical simulations and experimental results with synthesized harmonic acoustic wells for the generation of customized colloidal patterns of 2 μm polystyrene particles, with the letters ‘O’, ‘D’ and ‘K’. Scale bar, 20 μm. d, Separation forces (averaged from six particles) for the colloidal particles with various excitation signal amplitudes ranging from 4 to 8 V. e, Quantitative characterization of the peak separation forces (F) and the corresponding separation velocities (V) with varied peak-to-peak voltage (U) for the 9.51-μm-diameter polystyrene particles (averaged from six particles). From a quadratic fit of the peak separation forces (e), the force quadratic constant qF is 0.91 ± 0.05 pN V−2 (fit value ± s.d.). A quadratic fit of the separation velocities gives a velocity quadratic constant qV of 0.25 ± 0.04 mm s−1 V−2 (fit value ± s.d.). f, Reversible pairing of U937 cells along both the x and y directions. The blue arrows indicate the direction of the acoustic radiation forces during reversible pairing. Scale bar, 10 μm.

By dynamically and reversibly switching between the single-colloid trapping and pairing modes (Fig. 3b), repeatable (operating for more than 1,000 pairing cycles, Supplementary Video 6) and high-throughput (>100 pairs simultaneously, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Video 7) studies can be performed. We characterized the separation force during this reversible pairing process for polystyrene particles with an average diameter of 9.51 μm. As shown in Fig. 3d, we experimentally measured the force–time curves, and the peak separation force is calculated to range from 1.6 to 19.5 pN with variable excitation amplitudes. Note that the separation force scales with the square of the SAW excitation amplitudes (Fig. 3e). The separation force applied on cells can also be calculated (Supplementary Notes 3-6). The time for particles to be fully separated was approximately 12 ms when using an 8 V SAW excitation signal. Combining this short exposure time with the piconewton separation forces decreases the likelihood that this acoustic manipulation method would interfere with cell sample measurements.

Next, we investigated selective manipulation for single cell–cell pairings. Individual U937 cells (marked with different colours in Fig. 3f) were trapped in four adjacent acoustic wells. By switching the frequency of the harmonic standing SAWs between 39.8 and 79.6 MHz in the x direction, while keeping the frequency constant at 40.0 MHz in the y direction, two pairs of U937 cells can be periodically brought into contact and then separated in the x direction (Fig. 3f, top). To perform reversible cell–cell pairing in the y direction, we swapped the applied excitations in the x and y directions (Fig. 3f, bottom) and demonstrated that each cell could be paired with cells from different directions (Supplementary Video 8). Furthermore, we can selectively pair U937 cells while keeping neighbouring cells intact by modulating the synthesized six-component harmonic SAWs (Fig. 1d). In summary, with our non-invasive HANDS particle manipulation platform, we can reversibly pair cells in a high-throughput manner and can also selectively target any two neighbouring cells by simply modifying the applied multi-harmonic waves.

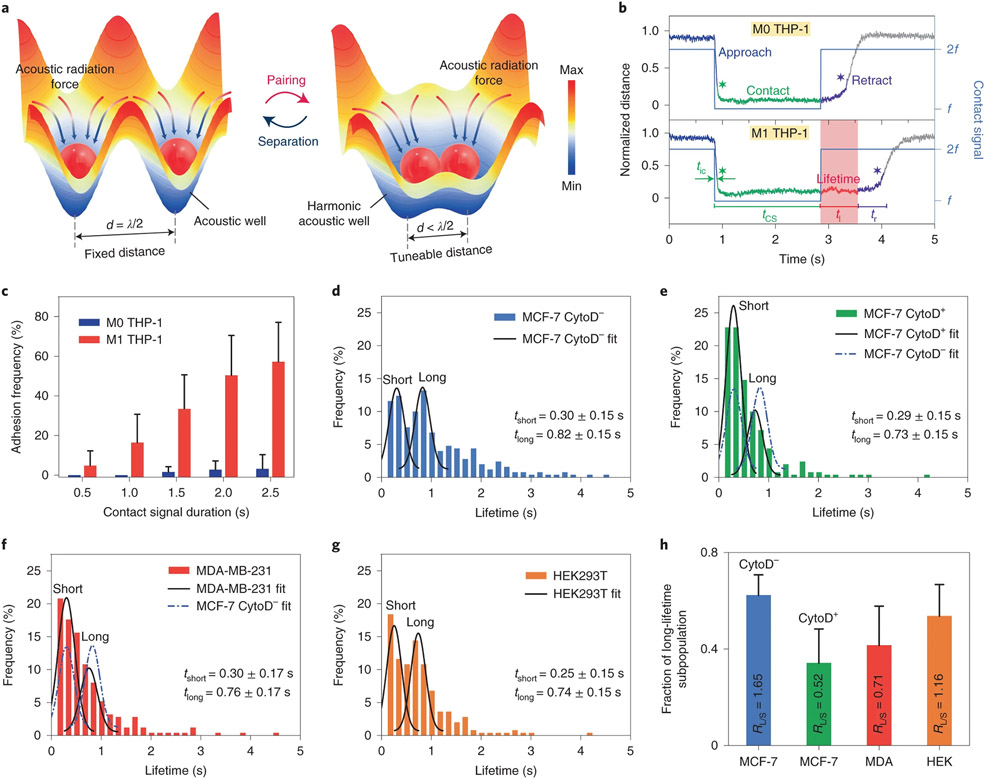

High-throughput quantification of cell-to-cell adhesion.

The ability to distinguish variations in cell–cell adhesion29,30 is a substantial quantitative capability for any single-cell manipulation and analysis technique. However, existing techniques, such as atomic force microscopy29, micropipette aspiration30 and optical tweezers31, typically require direct physical contact with the cells. They can only probe one cell pair each time, which is time-consuming and labour-intensive for any practical assay. With the ability to simultaneously perform repeated and reversible cell–cell pairing (Fig. 4a) in a large array in suspension, we conducted cell–cell adhesion assays with our HANDS platform on various cell lines. We first investigated whether HANDS manipulation could distinguish adhesion differences between adherent THP-1 macrophages (M1 THP-1) and non-adherent THP-1 monocytes (M0 THP-1). Here, THP-1 macrophages are differentiated from THP-1 monocytes with phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) as a stimulus36. As shown in Fig. 4b, top, non-adherent M0 THP-1 cells begin their retraction period immediately after a 2-s contact signal is deactivated since their intrinsic adhesion forces are not adequate to balance the acoustic separation forces. Conversely, M1 THP-1 cells cannot be immediately separated due to the significantly increased adherence with the PMA stimulation. The cell–cell distance trace for M1 THP-1 cells is a flat line for the period immediately after contact signal deactivation (Fig. 4b, bottom). This is due to the force clamp (the balance between the separation force and the adhesion force), and we define the duration of this force clamp period as the adhesion lifetime (t1). Using this value, we can distinguish differences in adhesion forces between cell types consistently and quantitatively. Additionally, we varied the applied contact signal duration tcs (0.5–2.5 s) to investigate variations in adhesion lifetimes (Supplementary Fig. 5a-f). Both heatmaps of the adhesion lifetimes (Supplementary Fig. 5a,b) and histogram of the adhesion frequency (Fig. 4c, defined here as the percentage of adhesion lifetime events per cell pair for 50 contact and separation cycles) present that the adhesion strength of M1 THP-1 cells increased with the duration of the applied contact signal. A western blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 5g) with a high expression of the intercellular adhesion molecule ICAM-1 confirmed that there should be a higher cell–cell adhesion strength in the M1 THP-1 cells than that in the M0 THP-1 cells. Altogether, these results support that the HANDS manipulation can successfully measure and distinguish adhesion differences between adherent and non-adherent cells.

Fig. 4 ∣. Reversible cell–cell pairings via HANDS for the quantification of intercellular adhesion strength in different cell lines.

a, Illustration of harmonic acoustic wells generated by the HANDS platform for tuning of particle or cell spacings. Single particles or cells can be reversibly paired or separated with HANDS manipulation. b, Representative normalized traces of cell–cell separation distances for M0 and M1 THP-1 cells. c, Dependence of the lifetime adhesion frequency with respect to the contact signal duration for M0 and M1 THP-1 cells. d–g, Histograms of cell adhesion lifetimes for MCF-7 (CytoD−) (d), MCF-7 (CytoD+) (e), MDA-MB-231 (f) and HEK293T (g) cells. The black lines are the Gaussian fits for each cell line, and the dashed blue lines are the Gaussian fits for MCF-7 CytoD− cells. tshort and tlong represent the average values of short and long lifetimes from the histograms with bimodal distribution, as determined by a double Gaussian kernel function. h, Fraction of long lifetime subpopulations for MCF-7 (CytoD−), MCF-7 (CytoD+), MDA-MB-231 and HEK293T cells.

In addition to cell surface proteins, cell–cell adhesion strength could also be affected by other intrinsic properties of cells, such as the actin cytoskeleton organization37. Thus, we applied the HANDS platform to examine and quantify the variation of cell–cell adhesion strength caused by perturbations in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton. We first explored the adhesion differences in MCF-7 cells with and without a Cytochalasin D (CytoD) treatment (Supplementary Fig. 5h). The CytoD treatment affects the organization of the cytoskeletal network and inhibits actin polymerization in cells38,39. Previous experiments have demonstrated that actin polymerization regulates the rapid cell–cell adhesion during cell migration37. Without the CytoD treatment (CytoD−), the histogram of the adhesion lifetimes for MCF-7 cells shows a bimodal distribution of short (tshort) and long (tlong) lifetimes with average values of 0.30 ± 0.15 and 0.82 ± 0.15 s, respectively, as determined by a Gaussian fit (Fig. 4d). In sharp contrast, CytoD+ MCF-7 cells had a lower fraction (34.2 versus 62.3%) of long lifetimes than CytoD− MCF-7 cells, which indicates a reduction in adhesion strength after CytoD treatment (Fig. 4e).

Since intercellular adhesion forces are critical information about cell–cell attachment and detachment, we also investigated the capability of HANDS manipulation to quantify the variations in cell adhesion forces among different cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 5i). MDA-MB-231 and human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells were tested following the same protocol as used with the MCF-7 cells. Compared with CytoD− MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4d), MDA-MB-231 cells show a lower fraction (41.5 versus 62.3%) of long adhesion lifetimes (Fig. 4f), which suggests a lower cell adhesion than CytoD−MCF-7 cells. Additionally, the adhesion lifetimes of HEK293T cells show an almost equally populated bimodal distribution with similar short (46.4%) and long (53.6%) lifetime subpopulations (Fig. 4g). For each cell line tested above, the bimodal Gaussian distribution in the lifetime enables a detailed comparison of the fractions of short and long lifetimes. In Fig. 4h, the adherent cells are compared on the basis of their fractions of lifetime subpopulations, and the average lifetime fraction ratio RL/S (the ratio of the long lifetime fraction to the short lifetime fraction) is calculated for each cell type. This average lifetime fraction ratio could be used as an indicator for indirectly measuring the differences in cell–cell adhesion behaviour and strength. Notably, the adhesion strength decreased (as indicated by RL/S decreasing from 1.65 to 0.71) as the metastatic potential increased for the human breast cancer cell lines from MCF-7 to MDA-MB-231, which is consistent with measurements taken by micropipette aspiration and static methods40.

Discussion

With our HANDS platform, we have demonstrated reversible, dexterous (such as pairing and separating) formation of colloidal crystals and precise manipulation of single cells in a high-throughput, dynamic, selective, accurate manner, analogous to tactile human hands. We achieved this by using intelligent modulation of harmonic acoustic waves to generate time-effective Fourier-synthesized acoustic potential fields. The HANDS platform can precisely handle soft matter to generate colloidal crystal monolayers with prescribed particle numbers and rotational speeds without using surface treatment or modifying their material properties. HANDS can also perform reversible cell–cell pairing and separation to accurately measure the values of intercellular adhesion forces, with a throughput 100 times higher than available single-cell manipulation techniques, such as atomic force microscopy, micropipette aspiration or optical tweezers. By simply modifying the applied multi-harmonic waves, we can reversibly pair cells in a high-throughput manner or selectively pair any two neighbouring cells. With its soft yet powerful, precise yet high-throughput particle manipulation mechanism, the HANDS platform provides a practical solution to provide deeper insights into intercellular adhesion forces, predict cancer metastasis and establish a platform for personalized medicine via precision 3D biomaterial synthesis for organoid engineering. The ability to create flexible lattices will revolutionize the discovery of colloidal and photonic crystals, providing a deeper understanding of soft matter and bring together non-living and living matter.

Methods

Device fabrication and experiment set-up.

A schematic and a photo of one HANDS device are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a. To fabricate the device, two orthogonal pairs of segmented interdigital transducers (see Supplementary Note 1 for further details), with a 10-nm-thick Cr adhesion layer and an 80-nm-thick Au conductive layer, were deposited onto a 128° Y-cut lithium niobite (LiNbO3) piezoelectric substrate (Precision Micro-Optics) using standard photolithography, e-beam evaporation and lift-off techniques19. Each pair of segmented interdigital transducers can generate harmonic standing SAWs of any order (from the specified base frequency up to the Nth harmonic). In the centre of two orthogonal pairs of interdigital transducers, a 400 × 400 × 20 μm3 polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chamber, fabricated using soft lithography techniques from a silicon mould, was bonded to the LiNbO3 substrate. To enhance the bonding between the LiNbO3 substrate and the PDMS chamber, the LiNbO3 substrate was immersed in a 5% (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES, Sigma-Aldrich) aqueous solution at 90 °C for 20 min. After rinsing with deionized water and drying the substrate, the APTES coated LiNbO3 and PDMS chamber can be firmly affixed using an oxygen plasma-activated surface treatment.

To actuate the HANDS device, two independent time-division multiplexed excitations, which were generated by radio-frequency signal generators (N9310A and E4422B, Keysight) or a dual-channel function generator (AFG3102C, Tektronix) and amplified by power amplifiers (30W1000B, Amplifier Research), were applied to the two orthogonal pairs of interdigital transducers, respectively. The frequency, amplitude, pulsing period and timing sequence of the excitations can all be programmed via the MATLAB controlled function generator. During the experiments, the signals were monitored by an oscilloscope (MSOX2024A, Keysight) in real-time. The HANDS device was operated under an inverted microscope (Eclipse Ti, Nikon). A ×40/0.95-NA (numerical aperture) objective lens (CFI, Nikon) was used to focus an image onto a CMOS camera (DS-Qi2, Nikon) for long-term video recording or a fast camera (FASTCAM Mini AX200, Photron) for high-frame-rate video recording, depending on the experiment. For all experiments under the microscope, a polarizer chip was used to eliminate the double image caused by reflections from the LiNbO3 surface.

Device operation.

Before sample loading, a 5% Pluronic F-127 (Sigma-Aldrich) aqueous solution was injected into the chamber through 0.28-mm (0.011-inch) inner-diameter polyethylene tubing (Warner Instruments) to coat the microfluidic chamber. Then, PBS was injected to flush the tubing and chamber for 10 min. After loading colloids or cells into the microfluidic chamber, programmed harmonic signals, generated from both the x and y directions, were applied to all the interdigital transducers to manipulate the colloids and cells. All cell manipulation experiments were conducted in 30 min after cells were loaded into the microfluidic chamber.

Cell culture and chemical perturbations.

Human breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231 (ATCC-HTB26) and MCF-7 (ATCC-HTB22)) and human embryonic kidney cell line (HEK293T (ATCC-CRL11268)) were cultured in DMEM (Gibco), containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Mediatech) in 100-mm tissue culture dishes (Falcon). Human monocytic leukaemia cell line (THP-1 (ATCC-TIB202)) was cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2-mercaptoethanol (0.05 mM, Sigma-Aldrich), 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Human myeloid leukaemia cell line (U937 (ATCC-CRL1593.2)) was cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin with T-25 flasks (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All cell lines were obtained from ATCC and maintained in a cell incubator (Heracell VIOS 160i, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C and a CO2 level of 5%.

M0 phase THP-1 cells were differentiated into macrophages (M1 phase THP-1) via incubation with 50 ng ml−1 phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 h and subsequent incubation in RPMI 1640 cell culture medium for another 48 h. For cell–cell adhesion measurement, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and HEK293T cells were firstly detached from 100-mm tissue culture dishes with a 12-min treatment in TrypLE (Gibco) and incubated at 37 °C. After cell washing and resuspension, the cells were incubated in DMEM for 1 h with 100 mm low attachment tissue culture dishes (Falcon). CytoD+ MCF-7 cells were incubated under the same conditions but pretreated with 10 μg ml−1 CytoD (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Before loading cells into the microfluidic chamber, cells were washed and resuspended in PBS. For all wash and resuspension steps, cells were centrifuged at 800 r.p.m. for 5 min.

Intercellular distance trace plot.

To obtain the intercellular distance trace plot from reversible cell–cell pairing, we monitored cell pairs with a microscope and recorded videos focused on regions of interest using a CMOS camera. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4c and Supplementary Video 7, 12 pairs of U937 cells with 50 contact and separation cycles were obtained in 6 min. By processing the regions of interest video with ImageJ, we measured the intercellular distance between the two opposite ends of a cell–cell pair. Two representative intercellular distance trace plots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4d.

Adhesion lifetime measurement.

The adhesion lifetime, t1, is defined as the time difference between the deactivation of the contact signal and the beginning of retraction for the cell pair (Fig. 4b):

| (1) |

where tc is the cell–cell contact duration, tcs is contact signal duration, tr is retraction time and tic is initial contact time. The contact duration tc is measured directly from the duration between initial and final cell–cell contact. The contact signal duration tcs is the excitation duration of base frequency for cell–cell pairing, which can be programmed into the signal generator. For Fig. 4b,d-h, the contact signal duration tcs is 2 s. For Fig. 4c, the contact signal duration varied from 0.5 to 2.5 s with a 0.5 s interval. The retraction time tr is 0.49 s, which is an average value calculated from non-adhesion M0 THP-1 cells of 250 pairing cycles. For each cell pairing cycle, the initial contact time, tic, is defined as the time difference between the activation of base frequency excitation and initial cell–cell contact. The initial contact time indicates the travelling time from original single-cell trapping position to cell–cell pairing position and it is measured directly through the recorded video.

Adhesion lifetime analysis with varied contact signal duration.

For M0 THP-1 and M1 THP-1, we obtained the lifetime data by varying the contact signal duration from 0.5 to 2.5 s with a 0.5-s interval. We repeatedly tested five cell pairs with over 50 contact-separation cycles, for each pair and each contact duration, respectively, to obtain the adhesion lifetime data. With these data, the lifetime heat map with varied contact signal duration can be obtained. Each value of the heat map pixel represents the number of lifetimes () among its lifetime range: []. Here, heat map parameters, such as the separation signal duration and lifetime range number, are given as tss = 5 s and W = 30, respectively, with integer i = 1, …, 30. The adhesion frequency Pa is calculated using:

| (2) |

where Ntot = 250.

Adhesion lifetime analysis among different adhesion cell lines.

For each cell line, the adhesion lifetime events were collected from five cell pairs with a total of 250 contact and separation cycles. The lifetime distribution was analysed using a histogram (Fig. 4d-g), and fitted using a double Gaussian kernel function:

| (3) |

where P is the frequency (%) of lifetimes per 250 events for an analysed cell line. , σi and Ai (i = 1, 2) are the mean lifetime, the standard deviation and the weight of the ith subpopulation, respectively. To classify the short versus long lifetimes, we used the average of two fitted mean lifetimes as the threshold: . For the short lifetime, P1 is defined as the frequency of lifetimes that t1 < tth; and for the long lifetime, P2 is the frequency of lifetimes that t1 ≥ tth. The fraction of short or long lifetime subpopulation can then be calculated as Pi/(P1 + P2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the Shared Materials Instrumentation Facility at Duke University. We thank S. Suresh, M. Dao, Z. Mao and J. Rich for their critical feedback and helpful discussions. We acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01GM141055 (T.J.H.), R01GM132603 (T.J.H.), U18TR003778 (T.J.H.) and UH3TR002978 (T.J.H.)) and the National Science Foundation (grant numbers ECCS-1807601 (T.J.H.) and CMMI-2104295 (T.J.H.)).

Footnotes

Competing interests

T.J.H. has cofounded a start-up company, Ascent Bio-Nano Technologies Inc., to commercialize technologies involving acoustofluidics and acoustic tweezers. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Code availability

The acoustic wave simulations were performed with commercial software MATLAB. Computation details can be made available from the corresponding authors on request.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-022-01210-8.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-022-01210-8.

Data availability

All the data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its Supplementary Information. Further information is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Li B, Zhou D & Han Y Assembly and phase transitions of colloidal crystals. Nat. Rev. Mater 1, 15011 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hou J, Li M & Song Y Recent advances in colloidal photonic crystal sensors: materials, structures and analysis methods. Nano Today 22, 132–144 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim MX, Souslov A, Vitelli V & Jaeger HM Cluster formation by acoustic forces and active fluctuations in levitated granular matter. Nat. Phys 15, 460–464 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozcelik A et al. Acoustic tweezers for the life sciences. Nat. Methods 15, 1021–1028 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo J et al. Modular assembly of superstructures from polyphenol-functionalized building blocks. Nat. Nanotechnol 11, 1105–1111 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manoharan VN Colloidal matter: packing, geometry, and entropy. Science 349, 1253751 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aubret A, Youssef M, Sacanna S & Palacci J Targeted assembly and synchronization of self-spinning microgears. Nat. Phys 14, 1114–1118 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu B et al. Switching plastic crystals of colloidal rods with electric fields. Nat. Commun 5, 3092 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demirors AF, Pillai PP, Kowalczyk B & Grzybowski BA Colloidal assembly directed by virtual magnetic moulds. Nature 503, 99–103 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang D, Ye S & Ge J Solvent wrapped metastable colloidal crystals: highly mutable colloidal assemblies sensitive to weak external disturbance. J. Am. Chem. Soc 135, 18370–18376 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashkin A, Dziedzic JM & Yamane T Optical trapping and manipulation of single cells using infrared laser beams. Nature 330, 769–771 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo F et al. Controlling cell-cell interactions using surface acoustic waves. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 43–48 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins DJ et al. Two-dimensional single-cell patterning with one cell per well driven by surface acoustic waves. Nat. Commun 6, 8686 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sitters G et al. Acoustic force spectroscopy. Nat. Methods 12, 47–50 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamsma D et al. Single-cell acoustic force spectroscopy: resolving kinetics and strength of T cell adhesion to fibronectin. Cell Rep. 24, 3008–3016 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marzo A & Drinkwater BW Holographic acoustic tweezers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 84–89 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melde K, Mark AG, Qiu T & Fischer P Holograms for acoustics. Nature 537, 518–522 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirayama R, Plasencia DM, Masuda N & Subramanian S A volumetric display for visual, tactile and audio presentation using acoustic trapping. Nature 575, 320–323 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian Z et al. Wave number–spiral acoustic tweezers for dynamic and reconfigurable manipulation of particles and cells. Sci. Adv 5, eaau6062 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baudoin M et al. Folding a focalized acoustical vortex on a flat holographic transducer: miniaturized selective acoustical tweezers. Sci. Adv 5, eaav1967 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friend JR & Yeo LY Microscale acoustofluidics: Microfluidics driven via acoustics and ultrasonics. Rev. Mod. Phys 83, 647–704 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang PH et al. Acoustofluidic synthesis of particulate nanomaterials. Adv. Sci 6, 1900913 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu Y et al. Acoustofluidic centrifuge for nanoparticle enrichment and separation. Sci. Adv 7, eabc0467 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan X-D, Zou Z & Zhang L Acoustic vortices in inhomogeneous media. Phys. Rev. Res 1, 032014 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delsing P et al. The 2019 surface acoustic waves roadmap. J. Phys. D 52, 353001 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuetz MJ et al. Acoustic traps and lattices for electrons in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. X 7, 041019 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schülein FJ et al. Fourier synthesis of radiofrequency nanomechanical pulses with different shapes. Nat. Nanotechnol 10, 512–516 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiß M et al. Optomechanical wave mixing by a single quantum dot. Optica 8, 291–300 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosseini BH et al. Immune synapse formation determines interaction forces between T cells and antigen-presenting cells measured by atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 17852–17857 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu B, Chen W, Evavold BD & Zhu C Accumulation of dynamic catch bonds between TCR and agonist peptide-MHC triggers T cell signaling. Cell 157, 357–368 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dholakia K & Reece P Optical micromanipulation takes hold. Nano Today 1, 18–27 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng Y et al. Mechanosensing drives acuity of αβ T-cell recognition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E8204–E8213 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen S & Lee LP Non-invasive microfluidic gap junction assay. Integr. Biol 2, 130–138 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glynne-Jones P, Boltryk RJ, Harris NR, Cranny AW & Hill M Mode-switching: a new technique for electronically varying the agglomeration position in an acoustic particle manipulator. Ultrasonics 50, 68–75 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marzo A, Caleap M & Drinkwater BW Acoustic virtual vortices with tunable orbital angular momentum for trapping of mie particles. Phys. Rev. Lett 120, 044301 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Auwerx J The human leukemia cell line, THP-1: a multifacetted model for the study of monocyte-macrophage differentiation. Experientia 47, 22–31 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chu YS et al. Force measurements in E-cadherin-mediated cell doublets reveal rapid adhesion strengthened by actin cytoskeleton remodeling through Rac and Cdc42. J. Cell Biol 167, 1183–1194 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Casella JF, Flanagan MD & Lin S Cytochalasin D inhibits actin polymerization and induces depolymerization of actin filaments formed during platelet shape change. Nature 293, 302–305 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang JH et al. Noninvasive monitoring of single-cell mechanics by acoustic scattering. Nat. Methods 16, 263–269 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmer CP et al. Single cell adhesion measuring apparatus (SCAMA): application to cancer cell lines of different metastatic potential and voltage-gated Na+ channel expression. Eur. Biophys. J 37, 359–368 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its Supplementary Information. Further information is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.