Abstract

A fluorogenic probe-based PCR assay was developed and evaluated for its utility in detecting Bacillus cereus in nonfat dry milk. Regions of the hemolysin and cereolysin AB genes from an initial group of two B. cereus isolates and two Bacillus thuringiensis isolates were cloned and sequenced. Three single-base differences in two B. cereus strains were identified in the cereolysin AB gene at nucleotides 866, 875, and 1287, while there were no species-consistent differences found in the hemolysin gene. A fluorogenic probe-based PCR assay was developed which utilizes the 5′-to-3′ exonuclease of Taq polymerase, and two fluorogenic probes were evaluated. One fluorogenic probe (cerTAQ-1) was designed to be specific for the nucleotide differences at bases 866 and 875 found in B. cereus. A total of 51 out of 72 B. cereus strains tested positive with the cerTAQ-1 probe, while only 1 out of 5 B. thuringiensis strains tested positive. Sequence analysis of the negative B. cereus strains revealed additional polymorphism found in the cereolysin probe target. A second probe (cerTAQ-2) was designed to account for additional polymorphic sequences found in the cerTAQ-1-negative B. cereus strains. A total of 35 out of 39 B. cereus strains tested positive (including 10 of 14 previously negative strains) with cerTAQ-2, although the assay readout was uniformly lower with this probe than with cerTAQ-1. A PCR assay using cerTAQ-1 was able to detect approximately 58 B. cereus CFU in 1 g of artificially contaminated nonfat dry milk. Forty-three nonfat dry milk samples were tested for the presence of B. cereus with the most-probable-number technique and the fluorogenic PCR assay. Twelve of the 43 samples were contaminated with B. cereus at levels greater than or equal to 43 CFU/g, and all 12 of these samples tested positive with the fluorogenic PCR assay. Of the remaining 31 samples, 12 were B. cereus negative and 19 were contaminated with B. cereus at levels ranging from 3 to 9 CFU/g. All 31 of these samples were negative in the fluorogenic PCR assay. Although not totally inclusive, the PCR-based assay with cerTAQ-1 is able to specifically detect B. cereus in nonfat dry milk.

Bacillus cereus is a gram-positive spore-forming rod that is ubiquitous in the environment. B. cereus has been implicated in many foodborne outbreaks involving cooked foods such as rice, meat loaf, turkey loaf, and mashed potatoes (9, 23). In addition to these types of foods, B. cereus is a common contaminant in dairy products (3). Food poisonings from the consumption of B. cereus-contaminated milk products have been rarely reported. Holmes et al. (16) reported an outbreak in which eight people developed acute food poisoning symptoms after the consumption of a macaroni-and-cheese dish. The epidemiological investigation resulted in the incrimination of the macaroni and cheese based upon the identification of high levels of B. cereus (108 to 109 organisms/g) within the food that was not served. Bacteriological analysis of the ingredients identified the powdered milk as the source. Schmitt et al. (20) reported two cases of food poisoning that resulted from the consumption of powdered milk products. B. cereus-like organisms were identified in the milk products; however, positive identification of the isolates was not performed (20). There is great concern, since many infant formulas are milk based and infants have a higher susceptibility risk than the general population (3).

Conventional methods for the identification of B. cereus consist of biochemical tests and microscopic analysis of cell morphology. Microscopic analysis is necessary since the closely related Bacillus thuringiensis has similar biochemical characteristics. Discrimination between these two species by classical methods is based upon the visual identification of a crystalline protein toxin produced by B. thuringiensis (24). There are two commercially produced kits for the identification of B. cereus, the TECRA VIA kit (International Bioproduct, Inc., Redmond, Wash.) and the BCET-RPLA kit (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom). The TECRA VIA kit is specific for a 45-kDa protein of nonhemolytic three-component enterotoxin, while the BCET-RPLA kit is specific for the L2 protein of three-component hemolysin (5, 14). Schraft and Griffiths (21) have developed a PCR-hybridization assay that is specific for organisms within the B. cereus group (B. cereus, Bacillus mycoides, and B. thuringiensis).

We have developed a highly sensitive probe-based fluorogenic PCR assay which can discriminate B. cereus from B. thuringiensis based upon two single-base differences within cereolysin AB gene. Initially, the sequences of the hemolysin BL and cereolysin AB genes were examined to differentiate B. cereus from B. thuringiensis. These two genes were chosen based upon their presumptive association with the ability of B. cereus to cause illness. Hemolysin BL has been shown to lyse sheep erythrocytes and elicit a vascular permeability reaction in rabbits, which correlates with the enterotoxigenicity of B. cereus (12). It has been suggested that hemolysin BL is responsible for the diarrheal food poisoning syndrome (4). The cereolysin AB gene encodes phospholipase C and sphingomyelinase, which constitute a biologically functional two-component cytolysin (11, 21). B. cereus phospholipase C and sphingomyelinase act synergistically in lysing human erythrocytes (11). Three single-base, species-specific differences between B. cereus and B. thuringiensis were identified within the cereolysin AB gene. A fluorogenic probe was designed based on the sequence differences. This fluorogenic PCR assay was used to test nonfat dry milk (NFDM) samples for the presence of B. cereus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The bacterial isolates used in this study are listed in Table 1. All bacterial isolates were grown in Trypticase soy broth (TSB) (Difco, Detroit, Mich.). A total of 72 B. cereus isolates and 5 B. thuringiensis isolates were tested as pure cultures in this study (Table 1). Strains were identified to species level by using a number of methods as described in the Bacteriological Analytical Manual (1). The putative B. mycoides strains are noted in Table 1 only on the basis of rhizoid growth.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in the study and fluorogenic assay results using CerTAQ-1 and CerTAQ-2

| Straina | Sourceb | Origin | ΔRQ using:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CerTAQ-1 | CerTAQ-2 | |||

| W1-1-3 | LMT | Whey | 0.11 | 0.66 |

| ATCC 10987 | ATCC | Unknown | 0.08 | NDc |

| W24-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.14 | 1.63 |

| W39-1-2 | LMT | Whey | 0.04 | 0.20 |

| W41-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 4.88 | 0.67 |

| W44-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.30 | ND |

| W45-2-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.34 | ND |

| W30-1-3 | LMT | Whey | 0.11 | 1.03 |

| W32-2-3 | LMT | Whey | 0.01 | ND |

| W35-1-2 | LMT | Whey | 0.08 | ND |

| W47-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.72 | ND |

| W50-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.79 | ND |

| W50-2-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.83 | ND |

| W48-2-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.81 | ND |

| W51-1-3 | LMT | Whey | 0.76 | ND |

| W49-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.33 | ND |

| W39-1-3 | LMT | Whey | 0.09 | 0.19 |

| W46-1-2 | LMT | Whey | 0.72 | ND |

| W52-2-2 | LMT | Whey | 0.18 | ND |

| 7-P | USDA | Unknown | 0.05 | 0.43 |

| 7-V | USDA | Unknown | 0.17 | 0.50 |

| F4433/73 | USDA | Meat loaf | 0.48 | 0.97 |

| F837/76 | Wong | Prostate infection | 0.29 | ND |

| W38-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.23 | 1.03 |

| F58 | LMT | Unknown | 0.83 | ND |

| F58-2 | LMT | Unknown | 0.80 | ND |

| ATCC 14579 | ATCC | Unknown | 3.55 | ND |

| 17-BM | USDA | Unknown | 3.45 | 1.03 |

| 17-P | USDA | Unknown | 3.21 | 0.90 |

| W27-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 4.59 | 1.32 |

| W37-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 5.21 | 1.42 |

| W42-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 4.69 | ND |

| W5-2-1 | LMT | Whey | 3.24 | 0.98 |

| B4ac-1 | USDA | Pea soup | 4.02 | 0.82 |

| B4ac-2 | USDA | Pea soup | 4.95 | 0.86 |

| B6acM | USDA | Unknown | 4.47 | 0.80 |

| H129M | LMT | Unknown | 5.29 | ND |

| H224M | LMT | Unknown | 5.60 | ND |

| R-96M | USDA | Unknown | 3.47 | 0.83 |

| Soc 67 | Wong | Periodontal | 3.40 | ND |

| S232M | LMT | Unknown | 0.21 | ND |

| AM232 | LMT | Unknown | 5.57 | ND |

| SSA-70 | USDA | Unknown | 0.13 | 0.48 |

| T-2M | USDA | Unknown | 0.1 | ND |

| F4370/75 | USDA | Barbecue chicken | 0.48 | 1.39 |

| NCTC11145M | USDA | Meat loaf | 0.37 | 0.92 |

| ATCC 10876 | ATCC | Unknown | 3.70 | ND |

| 45814/70 | USDA | Unknown | 3.85 | 1.00 |

| F4810/72M | USDA | Rice | 3.97 | 0.83 |

| MGBC142 | Wong | Endophthalmitis | 3.28 | ND |

| MGBC145 | Wong | Endophthalmitis | 3.24 | ND |

| NCTC11143 | USDA | Cooked rice | 4.37 | 1.03 |

| JAP-IV | USDA | Unknown | 0.16 | 0.62 |

| F4552/75 | USDA | Vomitus | 0.18 | 0.60 |

| 3-V | USDA | Unknown | 0.45 | 1.42 |

| 5056 | USDA | Meat loaf | 3.49 | 1.22 |

| H-13 | USDA | Unknown | 4.33 | 0.85 |

| 6-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.16 | 1.99 |

| ATCC 11778 | ATCC | Unknown | 3.75 | ND |

| 2-O | USDA | Unknown | 3.14 | 0.95 |

| 2-P | USDA | Unknown | 4.33 | 0.43 |

| 2-V | USDA | Unknown | 2.64 | 0.92 |

| 53-1-3 | LMT | Whey | 4.89 | ND |

| MAC-1M | USDA | Macaroni and cheese | 3.62 | 0.93 |

| T-1 | USDA | Unknown | 4.05 | ND |

| RAL-14 | USDA | Unknown | 0.15 | 0.39 |

| W15-1-2 | LMT | Whey | 3.72 | 0.92 |

| W2-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.01 | ND |

| W7-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 3.53 | 0.90 |

| W20-2-3 | LMT | Whey | 0.23 | 0.14 |

| W43-1-1 | LMT | Whey | 0.23 | ND |

| W43-1-2 | LMT | Whey | 0.27 | ND |

| B. thuringiensis 824 | Qualicon | Unknown | 0.19 | 0.14 |

| B. thuringiensis 639 | Qualicon | Unknown | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| B. thuringiensis 713 | Qualicon | Unknown | 0.23 | 0.14 |

| B. thuringiensis 833 | Qualicon | Unknown | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| B. thuringiensis 826 | Qualicon | Unknown | 3.82 | 1.05 |

All strains are B. cereus except for five B. thuringiensis strains. A superscript M indicates that the strain displayed rhizoid-like growth typical of B. mycoides.

USDA, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Philadelphia, Pa.; Qualicon, Qualicon, Inc., Wilmington, Del.; LMT, Laboratory for Molecular Typing, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.; Wong, Amy C. Lee Wong, Department of Food Microbiology and Toxicology, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

ND, not determined.

PCR for hemolysin and cereolysin sequences.

GenBank sequences for the B. cereus hemolysin (accession no. L20441) and cereolysin AB (accession no. M24149) genes were used to design primers (Table 2) for the amplification of 780- and 639-bp fragments from the hemolysin and cereolysin AB genes, respectively. All PCRs were performed in a Perkin-Elmer (Foster City, Calif.) model 2400 thermal cycler. The PCRs were carried out in a 50-μl volume consisting of 1× PCR buffer; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 100 μM (each) dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 1 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.); 500 nM each primer; and 1 μl of bacterial lysate. Lysates were prepared by the lysozyme-proteinase K treatment described previously by Czajka et al. (6). The cycling conditions were as follows: one cycle at 94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 63°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and one cycle at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining.

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide sequences and locations of PCR primers and fluorogenic probes

| Primer or probe | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Location (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Hemolysin primers | ||

| Hemolysin forward | GAAGGGTGCTATTTTGGGTCTAC | 706–728 |

| Hemolysin reverse | AGGGTATGGGTTCAAGTTCTAATC | 1485–1262 |

| Cereolysin primers | ||

| Cereolysin forward | CATGCGGCAAACTTTACGAACCT | 696–718 |

| Cereolysin reverse | TAATCTGCCGCCCCGAATAAAT | 1334–1313 |

| Cereolysin AB genes | ||

| B. cereus 17-B | 866 ACAAGATTAC 875......1287 GAAC 1290 | 866–1290 |

| B. thuringiensis 713 | 866 GCAAGATTAT 875......1287 AAAC 1290 | 866–1290 |

| Fluorogenic probes | ||

| cerTAQ-5′ | ATACAGCTGCTCTTACGAACCAATC | 927–903 |

| cerTAQ-3′ | TTATGCTGCTGACTATGAAAATCCTTA | 467–493 |

| cerTAQ-1 | CFGTAATCTTGTTTTCGCAACTACTGC | 876–852 |

| cerTAQ-2 | (AC) FGTAATCTTGTTTTCGC (ACG) ACTACTGC | 876–852 |

Nucleotides identified in boldface and underlined are B. cereus-specific nucleotides within the cereolysin gene. CF, nucleotide labeled with the reporter dye FAM; TT, nucleotide labeled with the quencher dye TAMRA.

Cloning and sequencing of PCR fragments.

PCR amplicons from B. thuringiensis strains 713 and 833 and B. cereus strains 17-B and 17-P were cloned using T vector plasmids (Promega, Madison, Wis.) according to the protocol described by the manufacturer. The sequences of the inserts were determined by dye termination using an Applied Biosystems (Foster City, Calif.) model 373 DNA sequencer and GENESCAN 672 software (Applied Biosystems).

NFDM spore counts.

The number of B. cereus spores per gram of NFDM was estimated for each sample using the three-tube most-probable-number (MPN) technique as follows (24). Two grams of NFDM was resuspended in 20 ml of TSB. Ten milliliters of the suspension was removed for testing with the fluorogenic PCR assay (see below). Of the remaining 10 ml, three 1-ml aliquots were inoculated into 10 ml of TSB containing polymyxin B sulfate (100 U/ml) (Sigma) (19). The sample was then serially diluted in sterile saline. Triplicate 1-ml aliquots from each dilution tube were inoculated into 10 ml of TSB containing polymyxin B sulfate (100 U/ml) and incubated for 48 h at 30°C. Tubes showing growth were streaked on B. cereus selective agar (Oxoid) and were incubated at 30°C for 48 h. Colonies typical of B. cereus colonies (large, crenated colonies, with failure to ferment mannitol and precipitation of hydrolyzed lecithin) were microscopically examined for the presence of lipid globules, spores, and the B. thuringiensis crystalline protein toxin. The number of positive tubes for each dilution was then used to calculate the CFU per gram of NFDM according to the MPN chart.

Spiked NFDM.

B. cereus isolate 17-P was inoculated into 10 ml of TSB and grown at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.2. The culture was serially diluted, and 100-μl aliquots from each dilution were inoculated into 10 ml of reconstituted NFDM (1 g in 10 ml of TSB). One-hundred-microliter aliquots from the same dilutions were plated in triplicate on Trypticase soy agar to determine the inoculation level.

NFDM testing.

One hundred microliters of trypsin (200 mg/ml) (Sigma) was added to the 10-ml sample of reconstituted NFDM set aside during the MPN preparation. The solution was then incubated at 55°C for 60 min to allow the trypsin to digest the proteins in the NFDM. The solution was incubated for 1 h at 37°C to allow for spore germination. The 1-h germination time was chosen based upon the results of In't Veld et al. (17), in which 90% of the spore population germinated within 30 min; 1 h was chosen in an attempt to achieve >90% spore germination (the 1-h incubation at 37°C was omitted for the samples spiked with vegetative cells). The solution was then centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at room temperature to remove any remaining particulate. The supernatant was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 15 min at room temperature to collect the bacterial cells. The cells were washed with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature.

The cell pellet was then processed by the following protocol, which is a modification of the method described by Herman et al. (15). The cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of water, to which 100 μl of 30% ammonium hydroxide was added, and mixed by vortexing. One hundred microliters of ethanol and 3.5 μl of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were added, and the solution was mixed by vortexing and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at room temperature. The supernatant was removed by aspiration, and the pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of a precipitation buffer consisting of 6 M urea, 1% SDS, 0.3% sodium acetate, 25% ethanol, and bacteriophage λ DNA (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) (80 ng/ml). The solution was then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at room temperature. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of a denaturing solution (0.1 M NaOH, 0.4% SDS) and microwave heated for eight 30-s intervals. Four hundred fifty microliters of 0.2 M NaCl was added to the microwave-treated solution, to which 600 μl of cold ethanol was added. The solution was incubated at −20°C for 30 min and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed by aspiration, and the pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and dried under vacuum. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of 10 mM Tris–1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Ten microliters was used for the PCR.

PCR detection with fluorogenic probe.

The probes and primer sequences are described in Table 2. Probe synthesis (Applied Biosystems) was described previously (2). The PCRs were carried out in 50-μl volumes consisting of 1× PCR buffer; 4 mM MgCl2; 100 μM (each) dATP, dGTP, and dCTP; 200 μM dUTP, 0.5 U of uracil DNA-glycosylase (New England Biolabs, Inc.), 2.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), 500 nM each primer, and 200 nM fluorogenic probe. The cycling conditions were as follows: one cycle of 50°C for 2 min and 94°C for 3 min; 45 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 59°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and one hold for 10 min at 72°C. After PCR cycling, the fluorescence intensities of the reporter dye FAM (6-carboxy-fluorescein) (λem = 518) and quencher dye TAMRA (6-carboxytetramethyl-rhodamine) (λem = 582) were quantified with a Perkin-Elmer LS-50B luminescence spectrometer, and ΔRQ values were calculated as previously described (2). The ΔRQ is defined as the difference in the ratio of the fluorescence intensity of the reporter dye over the quencher dye for the probe in the sample as compared to the ratio of the fluorescence intensity of the reporter dye over the quencher dye for the probe when no target is added. A ΔRQ threshold was calculated based upon the 99% confidence interval above the mean value for three no-template controls. ΔRQ values greater than the threshold are considered positive. The generation of the 461-bp PCR product was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining.

RESULTS

Hemolysin and cereolysin AB gene sequences.

The hemolysin BL and cereolysin AB genes were chosen based upon their presumptive association with the ability of B. cereus to cause illness. Since both of these genes are inherently associated with the B. cereus group, we cloned and sequenced fragments of each gene to identify nucleotide differences in a collection of B. cereus and B. thuringiensis strains. A fragment of each gene was chosen so that the entire amplicon sequence could be determined by sequencing from the 5′ and 3′ ends of the amplicon. Sequence analysis of the 780-bp hemolysin amplicon demonstrated that there were no species-specific differences between B. cereus and B. thuringiensis (data not shown). However, three single-base, species-specific differences were identified within the 639-bp cereolysin amplicon at nucleotide locations 866, 875, and 1287 (Table 2).

Fluorogenic PCR results for pure cultures.

A total of 72 B. cereus strains and 5 non-B. cereus strains were tested with the fluorogenic PCR as pure cultures, using the cerTAQ-1 and cerTAQ-2 probes. Table 1 lists the corresponding ΔRQ values and assay results. The fluorogenic PCR assay using the cerTAQ-1 probe was optimized as follows. The initial PCR conditions, consisting of an annealing temperature of 55°C, a 1.5 mM MgCl2 concentration, and a total of 30 cycles, resulted in ΔRQ values of 0.16 and 0.00 for B. cereus 17-P and B. thuringiensis 713, respectively. The annealing temperature, MgCl2 concentration, and number of cycles were increased in order to determine which conditions provided the greatest fluorescence signal for B. cereus while maintaining a minimal fluorescence production for B. thuringiensis. The final reaction conditions, as described above, consisted of an annealing temperature of 59°C, 4 mM MgCl2, and 45 cycles. A total of 51 out of 72 B. cereus isolates were positive according to assay calculations. Of these, some B. cereus strains had ΔRQ values in the range of 3 to 5, while others were much lower but above the threshold value. All of the isolates used in this study were tested with the fluorogenic PCR as pure cultures (Table 1). Forty-four B. cereus strains were positive, with a ΔRQ value higher than 0.4, using the cerTAQ-1 probe. Five B. thuringiensis strains were tested, and four of the five were negative with the cerTAQ-1 probe. One strain, B. thuringiensis 826, that tested positive was confirmed as a B. thuringiensis strain on the basis of crystal toxin production.

Sequences were determined for the probe binding site for B. cereus strains 3-V, JAP-IV, 7-V, SSA-70, T-2, and 7-P, which gave a ΔRQ value lower than 0.5 (Table 3). Interestingly, all six isolates possessed a thymine at the 3′ base (nucleotide 876) of the probe binding site. There was also one additional base difference at nucleotide 860 for the B. cereus 3-V sequence (Table 3). The other B. cereus strains had sequence differences at nucleotides 859 and 860 (cytosine and adenosine), while B. cereus strain JAP-IV was different only at nucleotide 860 (adenine) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Probe binding site sequences for fluorogenic PCR-negative isolates

| Probe or B. cereus strain |

Sequencea |

|---|---|

| cerTAQ-1 probe | 5CGTAATCTTGTTTCGCAACTACTGC3 |

| 3-V | 3TCATTAGAACAAAGCGGTGATGACG5 |

| JAP IV | 3TCATTAGAACAAAGCGATGATGACG5 |

| 7-V | 3TCATTAGAACAAAGCGACGATGACG5 |

| SSA-70 | 3TCATTAGAACAAAGCGACGATGACG5 |

| T-2 | 3TCATTAGAACAAAGCGACGATGACG5 |

| 7-P | 3TCATTAGAACAAAGCGACGATGACG5 |

Boldface indicates additional polymorphic sequences in the cereolysin probe target.

Based on the sequence variations, a new fluorogenic probe, cerTAQ-2, was designed to increase the detection spectrum for B. cereus, covering the varying bases (Table 3). The 3′ end base of the probe was designed to be either C or A, and the 17th base was designed to be A, C, or T. The 18th base of the probe was designed to be either A or G. A mixture of 12 different probes was produced. The initial PCR conditions for the cerTAQ-2 probe consisted of an annealing temperature of 55°C, a 4 mM MgCl2 concentration, and a total of 45 cycles. This resulted in ΔRQ values of 0.83 and 0.18 for B. cereus 17-B and B. thuringiensis 639, respectively. The annealing temperature and MgCl2 concentration were varied to optimize the ΔRQ for B. cereus while minimizing the ΔRQ for B. thuringiensis. The ΔRQ values obtained with an annealing temperature of 57°C for cerTAQ-2 are presented in Table 1. A total of 35 out of 39 B. cereus strains tested were positive, with a ΔRQ value of >0.4, with the cerTAQ-2 probe. The cerTAQ-2 probe could detect more B. cereus strains than the cerTAQ-1 probe, but the ΔRQ values were less than half of the values obtained with cerTAQ-1.

Spiked-NFDM analysis.

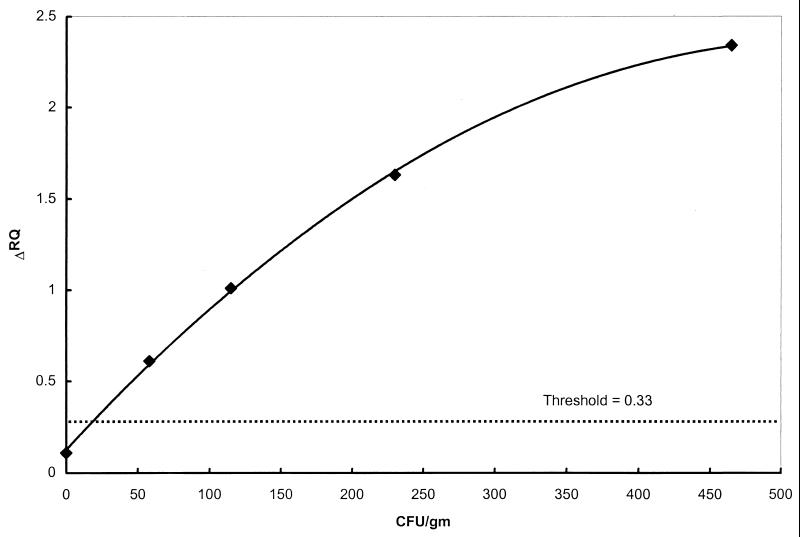

Reconstituted NFDM samples were inoculated with decreasing levels of B. cereus 17-B from an initial inoculum of 465 CFU/g. Figure 1 shows the fluorogenic PCR results for the spiked and nonspiked samples. The average ΔRQ values for triplicate PCRs are shown. ΔRQ values ranged from 2.34 to 0.61 for samples inoculated with 465 and 58 CFU/g (the lowest inoculum level) CFU/g, respectively. The average ΔRQ value for the nonspiked sample was 0.11, well below the threshold of 0.33. The ΔRQ values showed a linear relationship with cell numbers, indicating the possibility of quantification of contamination levels with this assay.

FIG. 1.

Fluorogenic PCR assay for artificially contaminated NFDM. Ten-milliliter aliquots of reconstituted NFDM (1 g of NFDM in 10 ml of water) were inoculated with various concentrations of B. cereus strain 17-P ranging from 0 to 465 CFU per sample. The ΔRQ values are the averages for triplicate PCRs for each sample preparation. The threshold value for this experiment was 0.33.

Analysis of naturally contaminated NFDM samples.

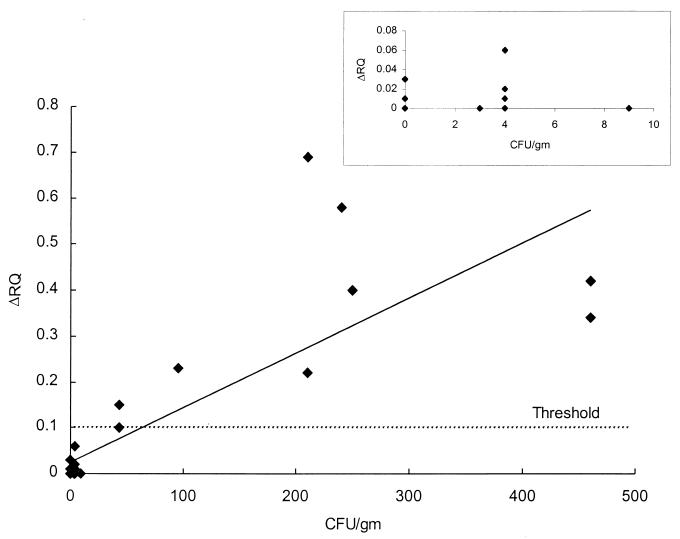

Forty-three NFDM samples were tested for the presence of B. cereus by the MPN technique. Twelve of the 43 samples tested were B. cereus negative; however, two of these samples contained high levels of B. thuringiensis (93 and 1,100 CFU/g). Nineteen samples were contaminated with B. cereus at levels ranging from 3 to 9 CFU/g. The remaining 12 samples were contaminated with B. cereus at levels ranging from 43 to 460 CFU/g.

The NFDM samples were also tested with the fluorogenic PCR assay. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the ΔRQ values from the fluorogenic PCR assay and the number of B. cereus spores per gram of NFDM. Threshold values for the fluorogenic PCR assay varied slightly, so the average of all of the calculated thresholds (0.10 ± 0.03) was used in Fig. 2. All NFDM samples that were contaminated with B. cereus at levels of 9 CFU/g or less were negative by the fluorogenic PCR assay. No samples were found to contain B. cereus at levels between 9 and 43 CFU/g. ΔRQ values for samples contaminated with B. cereus at levels of 43 CFU/g (0.11 and 0.15) were just above the calculated threshold of 0.10, suggesting a positive sample. While this level of contamination was positive, the ΔRQ values were lower than expected, since the extrapolation of the sensitivity curve indicated a minimum sensitivity of 25 CFU/g. ΔRQ values increased proportionally to the number of B. cereus CFU per sample to 460 CFU/g (Fig. 2). The B. cereus-negative samples containing B. thuringiensis at levels of 93 and 1,100 CFU/g produced ΔRQ values of 0.00 and 0.03, respectively. These ΔRQ values demonstrate the assay's specificity even when high levels of B. thuringiensis are present.

FIG. 2.

Fluorogenic PCR assay for naturally contaminated NFDM samples. Forty-three NFDM samples were tested for the presence of B. cereus with the fluorogenic PCR assay. The number of B. cereus CFU per g of NFDM was determined using the MPN technique. PCRs were conducted in duplicate for each NFDM sample. The inset includes the samples which range from 0 to 9 CFU/g.

DISCUSSION

B. cereus has been implicated in many food poisoning outbreaks involving rice, meat loaf, chicken, and pasta (9, 23). Food poisoning resulting from the consumption of B. cereus-contaminated milk products has not been well documented. The incrimination of B. cereus is often through epidemiological investigation, without the recovery of B. cereus from the patient, the food source, or both. While reported cases of food poisonings resulting from the consumption of B. cereus-contaminated milk products are few, the prevalence of B. cereus-contaminated milk products is quite high. Becker et al. (3) have found that 54% of dried milk products and infant formulas tested were contaminated with B. cereus at levels ranging from 0.3 to 600 CFU/g. Since B. cereus is a common contaminant in NFDM products and infant formulas are often NFDM based, regulations have been established that allow a maximum of 100 B. cereus spores/g of infant formula (10).

The detection of B. cereus in food by classical methods often requires selective enrichments of up to 48 h followed by selective plating for 24 to 48 h. Presumptive B. cereus isolates must then be tested by several biochemical and microscopic procedures to confirm whether or not the isolate is B. cereus (24). Crystal formation is one key test that positively identifies B. thuringiensis. Acrystalliferous variants of B. thuringiensis or nonrhizoid variants of B. mycoides may be misidentified as B. cereus (1). In addition to these variants, B. thuringiensis does not produce the crystalline toxin until late in the growth phase, when nutrients are diminishing. Improper growth conditions, such as a rich medium, might result in the lack of crystal production. The BCET-RPLA kit (Oxoid) and the TECRA VIA kit (International BioProduct, Inc.) are two commercially produced immunoassays that are currently available for the detection of B. cereus. Both kits require the culture of presumptive B. cereus isolates for 6 to 18 h prior to testing. The culture supernatants are then tested for the enterotoxin-related proteins. The BCET-RPLA kit uses antiserum which is specific for L2 of three-component hemolysin (containing components B, L1, and L2), while the TECRA-VIA kit uses antiserum specific for the 45-kDa component of nonhemolytic three-component enterotoxin (13, 14, 19). An evaluation of the BCET-RPLA test conducted by Granum et al. (13) resulted in the positive identification of 95% of the toxigenic B. cereus strains tested. There were two isolates associated with the diarrheal syndrome that lacked the L2 of three-component hemolysin, resulting in false-negative reactions. In addition to these two false negatives, there was one false positive resulting from an isolate that did not produce the enterotoxin, as confirmed by Western blotting, but was positive in the BCET-RPLA test (13).

Several studies have compared the BCET-RPLA and TECRA-VIA kits for their ability to detect the B. cereus enterotoxin (5, 8, 19). Buchanan and Schultz reported the positive identification of 8 out of 10 and 9 out of 10 enterotoxigenic B. cereus strains by the BCET-RPLA and TECRA-VIA kits, respectively (5). Day et al. reported that 6 of 13 enterotoxigenic B. cereus strains were positive according to the BCET-RPLA, while all 13 produced positive results in the TECRA-VIA assay (8). Rusul and Yaacob also found similar results after testing 194 B. cereus isolates. Of the 194 isolates tested, 84.5 and 91.8% were positive according to the BCET-RPLA and TECRA-VIA kits, respectively (19). All of these studies suggested that the TECRA-VIA kit has a greater ability to identify enterotoxigenic B. cereus. Aside from the study conducted by Buchanan and Schultz (5), which tested only one B. thuringiensis isolate, none of these studies tested B. thuringiensis and B. mycoides isolates to determine the rates of false-positive results produced by these species.

In this study, a highly sensitive probe-based fluorogenic PCR assay was developed to detect B. cereus, based on species-specific nucleotides within the cereolysin AB gene. Initially, the cereolysin AB genes of a collection of B. cereus and B. thuringiensis strains were examined, since this gene is inherently associated with the B. cereus group. The cereolysin AB gene encodes a two-component cytolysin, containing phospholipase C and sphingomyelinase, which has a close relationship with Clostridium perfringens α-toxin (22). In addition to possessing both cereolysin AB activities and metal binding properties, clostridial α-toxin is similar in size to the sum of mature cereolysin AB phospholipase C and sphingomyelinase components, that is, about 43,000 Da (11, 25). With the close relationship between two cytolysins, it was suggested that a cereolysin AB-type determinant may have evolved to the clostridial α-toxin as the result of deletion of the intergenic spacer (766 bp) and additional sequences not required for enzymatic activity (11). Assuming that the cereolysin AB gene may undergo an evolutionary process, sequence divergence was expected to occur around the intergenic spacer region of this gene. There were no sequence differences observed within the intergenic spacer regions of the cereolysin AB genes of B. cereus and B. thuringiensis. Instead, two nucleotides in cereolysin A (nucleotides 866 and 875) and one nucleotide in cereolysin B (nucleotide 1287) were found to be specific for B. cereus. Since these three single-base differences in cereolysin AB genes were consistent among the tested B. cereus and B. thuringiensis strains, it is interesting to speculate that the sequence polymorphism found in the cereolysin AB gene may reflect the evolutionary mutagenic drift in the B. cereus group.

The ability of the fluorogenic PCR assay to specifically identify B. cereus rather than B. thuringiensis is very useful when testing NFDM products. As seen by the MPN testing of NFDM samples, two samples were contaminated with high levels of B. thuringiensis, at 93 and 1,100 CFU/g. The specificity of the fluorogenic PCR assay is a key feature, since the misidentification of B. thuringiensis (at levels of ≥100 CFU/g) as B. cereus would be a false positive.

The B. cereus fluorogenic PCR assay was able to detect at least 58 CFU/g of NFDM. Extrapolation of the sensitivity curve to the threshold (Fig. 1) results in an approximate sensitivity of 25 CFU/g. In addition to detecting as few as 25 B. cereus CFU/g of NFDM, the fluorogenic PCR assay is relatively quantitative and provides a rapid means of detecting B. cereus in NFDM compared to conventional methods that require several days of incubation or enrichment. Sample results can be obtained within 9 h from the start of the protocol. While not totally inclusive for all strains which are biochemically and microscopically identified as B. cereus, the assay did detect all of the culture-positive NFDM samples tested.

Differentiation of isolates from the B. cereus group based upon morphological characteristics is questionable at times, since there is a possibility that these characteristics may not be expressed or may even be completely lost. Isolates of B. mycoides and B. thuringiensis that lost the ability to produce rhizoid colonies and crystal toxins, respectively, have been reported (1). Without these discriminatory characteristics, the isolates would be identified as B. cereus. The difficulty in clearly identifying isolates within the B. cereus group is also increased due to the recent identification of enterotoxin-producing B. thuringiensis strains (7, 18). In light of the present findings, further research is needed to clearly determine the relationship between isolates of the B. cereus group and the possible health threats that each species might possess.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Bruce and A. Miller for providing the strains used in this study and T. Arvik, N. Cady, and S. Trotter for their valuable technical assistance throughout this project.

This work was supported by the Northeast Dairy Foods Research Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Bacteriological analytical manual. 7th ed. Arlington, Va: AOAC International; 1992. pp. 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassler H A, Flood S J A, Livak K J, Marmaro J, Knorr R, Batt C A. The use of a fluorogenic probe in a PCR-based assay for the detection of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3724–3728. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3724-3728.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker H, Schaller G, von Wiese W, Terplan G. Bacillus cereus in infant foods and dried milk products. Int J Food Microbiol. 1994;23:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beecher D J, Schoen J L, Wong A C L. Enterotoxic activity of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4423–4428. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4423-4428.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchanan R L, Schultz F J. Comparison of the Tecra VIA kit, Oxoid BCET-RPLA kit and CHO cell culture assay for the detection of Bacillus cereus diarrhoeal enterotoxin. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;19:353–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1994.tb00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czajka J, Bsat N, Piani M, Russ W, Sultana K, Wiedmann M, Whitaker R, Batt C A. Differentiation of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua by 16S rRNA genes and intraspecies discrimination of Listeria monocytogenes strains by random amplified polymorphic DNA polymorphisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:304–308. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.304-308.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damgaard P H. Diarrhoeal enterotoxin production by strains of Bacillus thuringiensis isolated from commercial Bacillus thuringiensis-based insecticides. FEMS Immun Med Microbiol. 1995;12:245–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day T L, Tatani S R, Notermans S, Bennett R W. A comparison of ELISA and RPLA for detection of Bacillus cereus diarrhoeal enterotoxin. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;77:9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb03037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drobniewski F A. Bacillus cereus and related species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:324–338. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.4.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Food and Drug Administration. Current good manufacturing practice, quality control procedures, quality factors, notification requirements, and records and reports, for the production of infant formula. Proposed rule. Fed Regist. 1996;61:36173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilmore M S, Cruz-Rodz A L, Leimeister-Wachter M, Kreft J, Goebel W. A Bacillus cereus cytolytic determinant, cereolysin AB, which comprises the phospholipase C and sphingomyelinase genes: nucleotide sequence and genetic linkage. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:744–753. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.744-753.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glatz B A, Spira W M, Goepfort J M. Alteration of vascular permeability in rabbits by culture filtrates of Bacillus cereus and related species. Infect Immun. 1974;10:299–303. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.2.299-303.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granum P E, Brynestad S, Kramer J M. Analysis of enterotoxin production of Bacillus cereus from dairy products, food poisoning incidents and non-gastrointestinal infections. Int J Food Microbiol. 1993;17:269–279. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90197-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granum P E, Lund T. Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:223–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman L M, De Block J H G E, Moermans R J B. Direct detection of Listeria monocytogenes in 25 milliliters of raw milk by a two-step PCR with nested primers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:817–819. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.817-819.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes J R, Plunkett T, Pate P, Roper W L, Alexander W J. Emetic food poisoning caused by Bacillus cereus. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:766–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.In't Veld P H, Soentoro P S S, Notermans S H W. Properties of Bacillus cereus spores in reference materials prepared from artificially contaminated spray dried milk. Int J Food Microbiol. 1993;20:23–36. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90057-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson S G, Goodbrand R B, Ahmed R, Kasatiya S. Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis isolated in a gastroenteritis outbreak investigation. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1995;21:103–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1995.tb01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rusul G, Yaacob N H. Prevalence of Bacillus cereus in selected foods and detection of enterotoxin using TECRA-VIA and BCET-RPLA. Int J Food Microbiol. 1995;25:131–139. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)00086-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitt N, Bowmer E J, Willoughby B A. Food poisoning outbreak attributed to Bacillus cereus. Can J Public Health. 1976;67:418–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schraft H, Griffiths M W. Specific oligonucleotide primers for detection of lecithinase-positive Bacillus spp. by PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:98–102. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.98-102.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi T, Sugahara T, Ohsaka O. Phospholipase C from Clostridium perfringens. Methods Enzymol. 1981;71:710–725. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(81)71084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor A J, Gilbert R J. Bacillus cereus food poisoning: a provisional serotyping scheme. J Med Microbiol. 1975;8:543–550. doi: 10.1099/00222615-8-4-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanderzant C, Splittstoesser D F. Compendium for the microbiological examination of foods. 3rd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamakawa Y, Ohsaka A. Purification and some properties of phospholipase C (α-toxin) of Clostridium perfringens. J Biochem. 1977;81:115–126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]