Abstract

Despite initial concerns about older adult’s emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic, reports from the first months of the pandemic suggested that older adults were faring better than younger adults, reporting lower stress, negative affect, depression, and anxiety. Using a convenience sample of 1,171 community-dwelling adults in the United States, ages 18–90, we examined whether this pattern would persist as the pandemic progressed. We created time bins to account for the occurrence of significant national events, allowing us to determine how age would relate to affective outcomes when additional national-level emotional events were overlaid upon the stress of the pandemic. Results showed that older age was associated with lower stress, negative affect, and depressive symptomatology, and with higher positive affect, and this effect was consistent across time points measured from March, 2020 through April, 2021. Age was less associated with measures of worry and social isolation, but older adults were more worried about their personal health throughout the pandemic. These results are consistent with literature suggesting that older age is associated with increased resilience in the face of stressful life experiences and show that this pattern may extend to resilience in the face of a prolonged real-world stressor.

Keywords: age, aging, COVID-19, emotional well-being, positivity effect

Introduction

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic took root in North America, extensive conversation was focused upon the disproportionate risks to older adults. From early in the pandemic, it was known and widely reported that older age was associated with a higher incidence of mortality and severe health consequences from the virus (Nikolich-Zugich et al., 2020; Wu & McGoogan, 2020), and there were concerns that this disproportionate risk might lead older adults to have particularly high anxiety. As societal measures were implemented to prevent viral spread—including stay-home orders and physical distancing requirements—there was also concern that these measures would disproportionately isolate older adults (Lee, Jeong, & Yim, 2020; Vahia, Jeste, & Reynolds, 2020).

Instead, study after study that surveyed adults in high-income countries during the first wave of the pandemic reported that older adults were actually faring better than younger adults in multiple metrics of mental health (Vahia et al., 2020). Using survey data collected in March-May 2020, we reported that older age was associated with lower rates of stress, negative affect, and worry, and with higher rates of positive affect (Cunningham, Fields, Garcia, & Kensinger, in press). Similar results were revealed in a 7-day diary study conducted in March-April 2020 (Klaiber, Wen, DeLongis, & Sin, 2021), in a one-time survey conducted in March-April 2020 (Wilson, Lee, & Shook, 2021), and in surveys from April 2020 (Carstensen, Shavit, & Barnes, 2020; Varma, Junge, Meaklim, & Jackson, 2021) and May 2020 (Birditt, Turkelson, Fingerman, Polenick, & Oya, 2021). In other studies, rates of anxiety and depressive disorders were found to be lower among older versus younger adults in Spain in late March 2020 (González-Sanguino et al., 2020), and in the United States in a survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control in June 24–30, 2020 (Czeisler et al., 2020). (See also Carney, Graf, Hudson, & Wilson, 2021; Nelson & Bergeman, 2021; Pearman, Hughes, Smith, & Neupert, 2021; Wolfe & Isaacowitz, in press; Young et al., 2021).

The goal of the present study was to examine whether these age-related patterns would persist as the pandemic progressed. We sought to distinguish between two primary alternate trajectories for the age-related patterns.

On the one hand, the pattern of age-related benefits in metrics of mental well-being may remain throughout the duration of the pandemic, with older age associated with better mental health (i.e., lower stress, worry, and negative affect, and higher positive affect). Increased age is often associated with markers of improved mental well-being, including lower negative affect or lower levels of depression or anxiety symptomatology (see reviews in Blazer, 2003; Piazza & Charles, 2006). It might be expected that if any moment in the pandemic would have created a boundary condition on this age-related pattern, it would be at the beginning of the pandemic with its abrupt upheavals to daily life caused by stay-home ordinances, physical distancing, and shifts to telehealth and virtual socializing. These disruptions may have been easier to navigate for younger adults, who likely started the pandemic with more experience using technology for socializing and completing many other tasks of daily life. In addition, there was a particularly strong focus in the media and from public health authorities on the danger of COVID-19 to older adults early in the pandemic, with more evidence of the danger to younger adults (e.g., long-term effects of COVID-19) emerging as the pandemic continued. If older adults maintained greater affective well-being than younger adults despite these challenges at the start of the pandemic, it might be expected that those gains would persist throughout the many months of the pandemic.

On the other hand, the reports from those earlier months may have overestimated the age-related differences in mental well-being. It is possible that age differences early in the pandemic were due in part to younger adults’ experience of greater disruption in their lives (e.g., changes in school and/or work), especially compared to people of retirement age. In addition, older age may have been less protective as the stressors of the pandemic were prolonged. While having more dire predictions about the pandemics’ trajectory in March corresponded with higher concurrent stress and negative affect (Whitehead, 2021), in the early months, most people still underestimated the duration of time over which these changes to daily life would be required. For instance, when we looked at our participants who enrolled prior to May 1, 2020, they estimated a “return to normal” in an average of approximately 4 months (median = 122 days), with fewer than 15% of participants estimating that the pandemic would continue for over a year.1 It is possible that as the pandemic dragged on, and as older adults continued to be warned of the risks of going into public spaces or of seeing close family in person, the relation of age to mental well-being may have shifted. While older adults tend to engage in emotion regulation strategies that enhance their well-being (e.g., avoiding stressful situations), prior literature suggests that when a stressor is prolonged and unavoidable, the age-related benefits to mental well-being may be attenuated (Charles, 2010). It may not be the abrupt transition at the start of the pandemic that creates a boundary condition for the generally-positive relation between older age and mental wellbeing but instead the prolonged and unavoidable nature of the pandemic and its disruptions to daily life.

These possibilities are important to adjudicate between, as they would lead to different conclusions regarding the nature of older adults’ resilience to stressors (Carstensen et al., 2020). The first alternative would suggest that older age buffers from the negative effects of chronic stressors, while the second alternative would suggest that older age primarily buffers from the stressors associated with an abrupt change (cf. Charles, 2010). Beyond contributions to understanding the psychology of aging, these alternatives are important to distinguish because there can be danger in basing current policies on data that reflects outcomes during only a narrow slice of time. There is no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected mental health outcomes, with overall rates of reported anxiety and depression much higher in January 2021 than in pre-pandemic months, and with approximately half of adults reporting that the pandemic has had a negative impact on their mental health (Panchal, Kamal, Cox, & Garfield, 2021). Yet the question remains as to whether older age may, throughout the pandemic, help to buffer from some of the more negative mental-health consequences of the pandemic, or whether the age-related benefits were short-lived.

To adjudicate between the two possible trajectories of age-related benefits on affective outcomes (i.e. persistent age-related benefits for duration of assessment vs. attenuated benefits over time), we continued data collection for the Boston College COVID-19 Sleep and Well-Being Study (Cunningham, Fields, & Kensinger, 2021). This longitudinal survey study launched during the first weeks of the pandemic in the United States, and results from those early months have been previously reported (Cunningham et al., in press). In the present study, we binned data collected from March 23, 2020 through April 17, 2021 into 10 pre-registered time bins. We enrolled a convenience sample of community-dwelling adults. Participants were primarily well-educated, White, and female. Because of the online nature of the survey study, only those with access to technology were invited to participate. Although the study followed participants over the course of a year, and in that sense is longitudinal, the age-related patterns all rely on cross-sectional data and therefore cohort effects or other influences confounded with age cannot be disambiguated. Despite the limitations of this sample, it is notable that in the early weeks of the pandemic, the age-related patterns revealed in this sample (Cunningham et al., in press) were quite similar to those seen in other samples (González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Klaiber et al., 2021; Vahia et al., 2020; Varma et al., 2021), including nationally representative samples in the United States (Birditt et al., 2021; Carstensen et al., 2020; Czeisler et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2021).

This dataset was further strengthened by the relatively early start and frequent nature of assessment over the course of more than a year from the onset of the pandemic in the US. An important consideration that few studies published to-date have taken into account is that the pandemic did not occur in isolation, and a number of other major national events occurred that likely had significant impacts on public mood and stress. As such, it is necessary to take the influence of these distinct national events into consideration to attempt to disentangle the effects of the pandemic from the effects of other stressors that occurred concurrently, especially when considering aggregate scores over an extended period of time. Further, distinguishing these events provides an opportunity to examine how age relates to emotional well-being metrics when there are novel stressors overlaid upon a continuing stressor. Here, we extended our previous work and the work of others to determine the long-term influence of age on measures of affective outcomes across more than a year of assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic, while taking these potentially novel, co-occurring stressors into consideration.

Methods

Participants

Recruitment for the study began on March 20, 2020, and occurred via four primary methods: 1) emails sent to those who had expressed an interest in being contacted about future studies being conducted by our research laboratory, 2) social media posts, 3) posts to listservs targeting those interested in cognitive and clinical psychology or related topics, and 4) word-of-mouth. All English-speaking adults age 18 or older were invited to participate.

The present data include survey responses from 1,171 participants who were located in the United States and who responded in at least one of the time bins analyzed. Analyses were restricted to participants in the United States given that the time course of the pandemic differed by country (see Supplementary Materials for exploratory analyses with international participants). Detailed demographics are presented in Table 1. The age of participants in this sample ranged from 18 – 90 years old (M = 36.4, SD = 15.9). While there was a skew toward adults under the age of 40, 162 adults were 40–59 years of age, and 161 adults were over age 60 (see Figure 2 for a histogram of the age distribution). Participants were compensated with entries into raffles for gift cards. The Boston College Institutional Review Board approved all testing procedures.

Table 1. Demographics.

Age was treated as a continuous variable in all models; age bins are presented simply to give an idea of how demographics varied across age.

| All | 18–39 | 40–59 | 60+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1171 | 848 | 162 | 161 |

| Age | ||||

| mean | 36.40 | 27.95 | 47.54 | 69.75 |

| std | 15.89 | 5.20 | 5.95 | 6.63 |

| min | 18 | 18 | 40 | 60 |

| 25% | 25 | 24 | 43 | 64 |

| 50% | 31 | 28 | 46 | 69 |

| 75% | 42 | 32 | 52 | 74 |

| max | 90 | 39 | 59 | 90 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 6.3% | 7.7% | 3.7% | 1.2% |

| not Hispanic | 91.9% | 90.8% | 95.1% | 95.0% |

| prefer not to say (ethnicity) | 1.8% | 1.5% | 1.2% | 3.7% |

| Race | ||||

| African American | 2.1% | 2.2% | 3.1% | 0.6% |

| Asian | 8.8% | 11.8% | 1.2% | 0.6% |

| White | 79.4% | 75.0% | 87.0% | 95.0% |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 2.1% | 2.4% | 2.5% | 0.6% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.6% | 0.0% |

| more than one race/prefer to self-describe | 6.1% | 7.4% | 3.1% | 1.9% |

| prefer not to say (race) | 1.0% | 0.9% | 1.2% | 1.2% |

| not reported | 0.3% | 0.1% | 1.2% | 0.0% |

| Gender | ||||

| female | 79.1% | 79.2% | 79.6% | 77.6% |

| male | 18.0% | 17.5% | 19.1% | 19.9% |

| non-binary/third gender | 1.5% | 2.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| prefer to self-describe | 0.3% | 0.2% | 1.2% | 0.0% |

| prefer not to say | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| not reported | 1.0% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 2.5% |

| Biological Sex | ||||

| female | 81.6% | 82.2% | 79.6% | 80.1% |

| male | 18.4% | 17.8% | 20.4% | 19.9% |

| Gender Identity | ||||

| cisgender | 97.5% | 96.9% | 100.0% | 98.1% |

| transgender | 1.0% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| prefer not to say | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.0% | 0.6% |

| not reported | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 1.2% |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||

| straight/heterosexual | 78.9% | 74.8% | 88.9% | 90.7% |

| bisexual | 12.8% | 15.6% | 9.3% | 1.9% |

| gay/lesbian | 3.5% | 3.8% | 1.2% | 4.3% |

| prefer to self-describe | 2.0% | 2.6% | 0.0% | 0.6% |

| prefer not to say | 1.5% | 1.7% | 0.6% | 1.9% |

| not reported | 1.3% | 1.7% | 0.0% | 0.6% |

| Education | ||||

| some high school | 0.4% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| high school diploma or GED | 2.3% | 2.1% | 1.9% | 3.7% |

| some college | 14.7% | 15.7% | 13.6% | 10.6% |

| bachelor's degree | 29.3% | 32.2% | 25.3% | 18.0% |

| some post-bachelor | 10.4% | 9.7% | 10.5% | 14.3% |

| graduate, medical, or professional degree | 42.9% | 39.7% | 48.8% | 53.4% |

| Relationship Status | ||||

| single | 34.1% | 41.0% | 16.7% | 14.9% |

| in a relationship | 26.7% | 34.0% | 10.5% | 5.0% |

| married | 32.4% | 23.8% | 61.1% | 48.4% |

| separated/divorced | 4.9% | 1.1% | 10.5% | 19.3% |

| widowed | 2.0% | 0.1% | 1.2% | 12.4% |

| Serious medical problems? | ||||

| yes | 8.2% | 6.4% | 12.3% | 13.7% |

| no | 91.8% | 93.6% | 87.7% | 86.3% |

| Income | ||||

| $0 – 25,000 | 7.9% | 8.7% | 6.8% | 5.0% |

| $25,001 – 50,000 | 14.8% | 15.1% | 6.8% | 21.1% |

| $50,001 – 75,000 | 18.0% | 18.9% | 12.3% | 19.3% |

| $75,001 – 100,000 | 16.1% | 15.1% | 18.5% | 18.6% |

| $100,001 – 150,000 | 19.2% | 19.6% | 19.8% | 16.8% |

| $150,001 – 250,000 | 15.2% | 13.9% | 25.9% | 11.2% |

| $250,000+ | 8.8% | 8.7% | 9.9% | 8.1% |

| Are you a full time student? | ||||

| yes | 24.3% | 33.0% | 2.5% | 0.0% |

| no | 75.7% | 67.0% | 97.5% | 100.0% |

| Are you currently employed? | ||||

| yes | 59.5% | 58.8% | 83.3% | 39.1% |

| no | 16.2% | 8.1% | 14.2% | 60.9% |

| not reported | 24.3% | 33.0% | 2.5% | 0.0% |

| Political Ideology | ||||

| Very Liberal | 12.6% | 12.6% | 13.0% | 11.8% |

| Liberal | 13.2% | 10.7% | 13.0% | 26.7% |

| Slightly Liberal | 3.6% | 3.1% | 3.7% | 6.2% |

| Moderate | 5.1% | 3.8% | 8.6% | 8.7% |

| Slightly Conservative | 1.4% | 1.1% | 3.1% | 1.2% |

| Conservative | 1.1% | 0.6% | 1.9% | 3.1% |

| Very Conservative | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| not reported | 63.0% | 68.2% | 56.8% | 42.2% |

| US Region | ||||

| Northeast | 47.7% | 44.6% | 42.6% | 68.9% |

| South | 15.9% | 17.1% | 15.4% | 9.9% |

| Midwest | 11.8% | 11.2% | 20.4% | 6.2% |

| West | 14.2% | 15.2% | 15.4% | 7.5% |

| not reported | 10.5% | 11.9% | 6.2% | 7.5% |

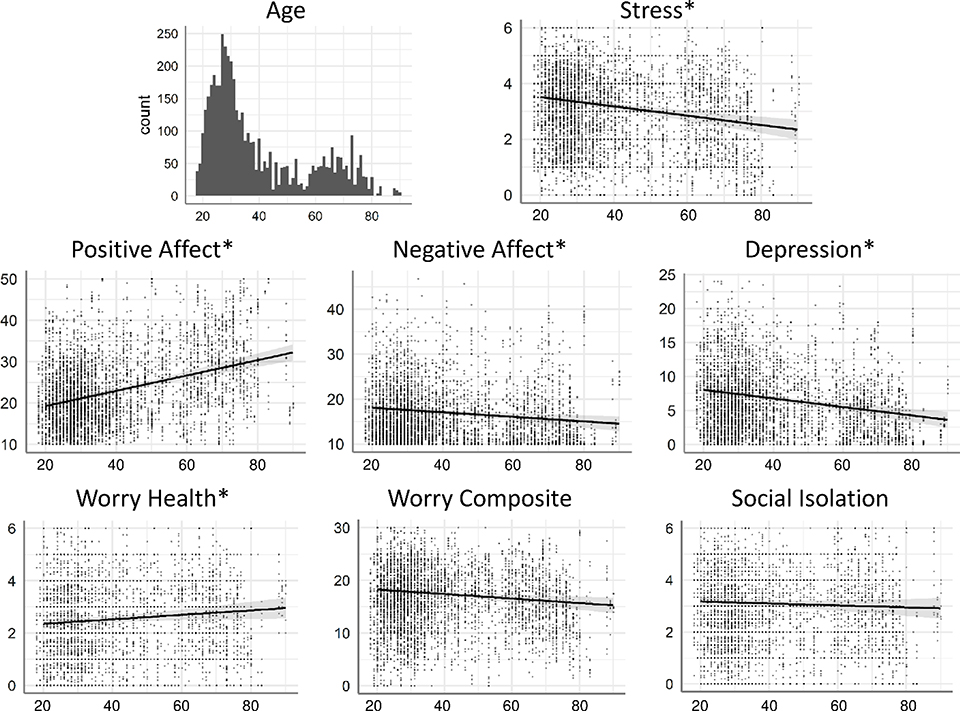

Figure 2. Effects of age.

The histogram at the top left shows the distribution of age among participants included in the main analysis. For all other plots, age is on the x-axis and score on each DV is on the y-axis. The dots show raw data averaged across time bins (darker dots represent overlapping data points). Lines show the marginal effect of Age and the 95% confidence interval from the Age x Time Bin mixed models (see Methods). Asterisks indicating DVs with a significant effect of age.

Assessment Materials and Design

All data reported here are from the Boston College COVID-19 Sleep and Well-Being Dataset (Cunningham et al., 2021) and are publicly available at Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/gpxwa/.

Demographic Survey:

The demographic survey included reports of age, current country of residence, sex and gender, sexual orientation, race, socioeconomic status, marital status, military status, education, number of dependents, previous diagnoses of serious mental health and medical conditions, the impact that COVID-19 has had on education and employment status, and their expectations for how long the pandemic would prevent things from “returning to normal”.

Longitudinal Survey:

To reduce participant burden, we utilized two versions of our primary recurring survey. For a majority of the data collection periods, the surveys were sent daily with a “Full” Version of the survey sent approximately 2 days/week and a “Short” version of the survey sent the remaining days of the week (but see Survey Distribution below for more details). The Full Version of the survey included all questions analyzed here: a question regarding subjective experience of stress, the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson & Clark, 1994), questions about the subjective experience of worry related to COVID-19 (Cunningham et al., 2021), subjective perception of social isolation, and symptoms of depression using a modified version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) that omitted the question assessing suicidality (as requested by the Boston College IRB). Of these, the Short Version included only the question regarding subjective experience of stress.

In addition to these regular assessments, larger assessment batteries were administered at less frequent intervals. Relevant to the measures collected here, we assessed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 Scale on three occasions (released May 19 2020, September 28 2020, and February 27 2021) and the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) on two occasions (released on June 16 2020 and February 27 2021). As only a subset of participants opted to complete these assessments on each occasion, more information and results from these assessments are reported in the Supplementary Materials. PDF versions of each of these assessments can be found at https://osf.io/gpxwa/.

Longitudinal Survey Distribution:

When the study was initially launched on March 20, 2020, we had only created the Full Version of the longitudinal survey and it was sent every day for the initial week of data collection (March 21 - March 27, 2020). Once it became apparent that the pandemic was going to extend beyond a few weeks of data collection, we developed the Short Version of the survey to reduce participant burden. The Short or Full version of the survey was then sent daily from March 28 - May 20, 2020. The Full version of the survey was sent to all registered participants approximately two times per week, with the Short version of the survey sent the remaining days of the week. The days of the week that the Full version of the survey (as opposed to the Short version) was sent was established pseudorandomly such that the initial days were determined using a random number generator which then eliminated those days from contention the next week and so on until the full survey was assessed once on each day of the week, and then the schedule started over to ensure equal distribution of Full survey data collection by day of the week.

To further reduce participant burden, from May 21 - June 23, 2020 the Short Version of the survey was dropped and we just continued the collection of the Full Version of the survey 2–3 times per week, with no additional assessment the remaining days of the week. Then, at what appeared to be the trough of the first wave of the pandemic and due to logistic and funding considerations and to further reduce participant burden, we scheduled a break in this daily/weekly data collection schedule. As we were still interested in the long-term effects of the pandemic, we transitioned to more targeted periods of data collection. From September 30, 2020 - April 17, 2021 we collected 8 more weeks of data collection broken up into four 2 week periods of daily assessments that returned to a mixed distribution of the Full Version of the survey 2–3x per week and the Short Version of the survey sent the remaining days of the week.

Enrollment in the study was open throughout the entire course of data collection reported here, and participants began receiving notification of the longitudinal surveys after consenting and completion of the demographic survey. Participants were regularly reminded that completion of each Full and Short Version of the survey was entirely optional, that they were free to skip days, and that they were welcome to only complete the survey on the days in which they had the time and energy to do so. Participants received an invitation for each survey via email at 8am in their respective time zone every day it was assessed during the time bins described below. Given the optional nature of each survey, no reminders were sent on a given day. Duplicate responses on the same day were removed from analysis (see Cunningham et al., 2021). A summary of the number of participants in each time bin, the number of responses from each participant in each time bin, and the number of time bins with responses from each participant can be found in Tables S1–S4 in the Supplementary Materials.

Data Analyzed:

We preregistered analysis of the following measures: the subjective experience of stress question from the Short and Full Version of the longitudinal surveys, as well as the PANAS positive scale, PANAS negative scale, worry questions (Worry Composite and individual health worry question), and the modified PHQ-9 scale questions from the Full Version of the longitudinal survey. Though not pre-registered, we also examined subjective social isolation. We used age as reported in the demographic survey as a predictor.

Time Bins:

In this dataset, 21 weeks of Full and Short surveys were assessed across more than a year of data collection. As pre-registered and detailed in Table 2, to look at the change in the outcome metrics over the course of the pandemic, we separated these data collection periods into discrete time bins. These time bins break up the initial 3 months of data collection into smaller components and include the additional periods of targeted daily assessment from September 2020 to April 2021.

Table 2.

Time bins used for analyses.

| Time Bin | Start | End | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 3/23/20 | 4/12/20 | 3 weeks | Overlaps with the beginning of significant institutional responses to the pandemic. Many schools and universities closed or went to remote education in mid- to late-March, and most US states implemented some kind of lockdown order or stay at home order/advisory during this period. |

| T2 | 4/13/20 | 5/3/20 | 3 weeks | Initial discussions and implementations of “re-opening” after lockdowns in many states, but case numbers and deaths were still rising in most parts of the country. |

| T3 | 5/4/20 | 5/24/20 | 3 weeks | Re-opening plans continued in this period. Case numbers and deaths were declining in some parts of the country, but still rising in others. |

| T4 | 5/25/20 | 6/14/20 | 3 weeks | George Floyd was killed on May 25, setting off nation-wide protests and a wide-ranging national discussion on race. |

| T5 | 6/16/20 | 6/22/20 | 1 week | The last week of data collection in the spring period. Initial examination of trends suggest that much of the increased stress and negative mood following George Floyd’s murder had resided by this time period. |

| T6 | 9/30/20 | 10/13/20 | 2 weeks | Our first period of daily data collection since June. This marked the end of a period where COVID cases had been down (relative to the spring or mid-summer) in most of the country and is mostly before they started to rise again in October. |

| T7 | 10/30/20 | 11/5/20 | 1 week | The US election was on November 3. Uncertainty about the result continued through November 6. |

| T8 | 11/7/20 | 11/13/20 | 1 week | The US presidential race was called for Joe Biden by all major networks on November 7. |

| T9 | 2/22/21 | 3/7/21 | 2 weeks | Our first period of data collection since November. This marked the beginning of vaccinations becoming available to older adults. |

| T10 | 4/4/21 | 4/17/21 | 2 weeks | Our final period of data collection before vaccines became available to all adults on April 19, 2021. This time bin was also selected to be well matched, seasonally, to the T1 assessment. |

As discussed above, the pandemic has not persisted without the co-occurence of additional stressors that may have had an influence on public mood and well-being in the United States. We identified two important events with significant national attention that were overlaid upon the COVID-19 pandemic that we believed were important to account for in our analysis: (1) on May 25, 2020, George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis, MN, setting off nation-wide protests that peaked in early June (Kishi & Jones, 2020) and (2) on November 3, 2020, the United States Election took place, and due primarily to the processing of mail-in ballots, the presidential race was not called by all major news networks until November 7. By marking these events in the time-course analyses, we also could ensure that we were not misattributing mental health outcomes to the COVID-19 pandemic if, in fact, they were heavily influenced by these other national events. For instance, it was plausible to us that the CDC survey administered in late June (Czeisler et al., 2020), which asked participants to report on their mental health over the past 30 days, could have detected higher rates of anxiety and depression among younger adults not specifically because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also because of the stress surrounding the murder of George Floyd. Thus, as detailed in Table 2, we established and pre-registered our time bins to determine the relation between age and emotional well-being over time, in the context of the chronic stress of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic while taking into account co-occurring stress in the periods surrounding the murder of George Floyd and the 2020 U.S. election. Finally, we scheduled our final time bin to overlap with the same time of year as our initial data collection period from the launch of the study, such that we would be able to make comparisons with overlapping seasonal influences.

Data Analysis

The data analysis plan for this study was pre-registered at https://osf.io/68yz5/. Scripts and materials used for analyses reported here are available at the same link.

The PANAS metrics of positive and negative affect were scored as recommended. The eight assessed PHQ-9 questions were summed as a modified depression score (referred to as “depression” in the results). The questions on subjective experience of stress and perception of social isolation were reported on 7-point Likert scales. The worry questions also were presented on 7-point Likert scales and were specifically designed to assess worry in different domains (individual health, family/friend health, community health, national health, financial impact) as it related to COVID-19 (Cunningham et al., 2021). To assess overall worry we created a Worry Composite by summing the responses to all worry questions on the longitudinal surveys except for the worry question on individual health. Given the presentation of COVID-19, we expected worry about individual health to be impacted differently by age (https://osf.io/68yz5/), and thus it was analyzed separately.

To test our hypotheses, we averaged across all responses for each participant in each time bin (see Table 2 for time bins) for each variable. These time bins were based on the time course of the pandemic and other national events in the United States and were preregistered (https://osf.io/68yz5/) prior to examining age effects. The average responses in each time bin for each DV were analyzed with linear mixed models with a random intercept for subject (we did not include random slopes since each participant had only one age and only one value per time bin). As done in Cunningham et al. (in press), each dependent variable of interest was analyzed in a separate model. The fixed effects were Age as a mean-centered continuous predictor and Time Bin as a backward difference coded categorical predictor. Models were estimated with restricted maximum likelihood, and degrees of freedom and p-values were estimated via the Kenward-Rogers method. Analyses were conducted in R version 4.0.5 (see Supplementary Materials for full details of software implementation). All code used for analysis is available on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/68yz5/.

Results

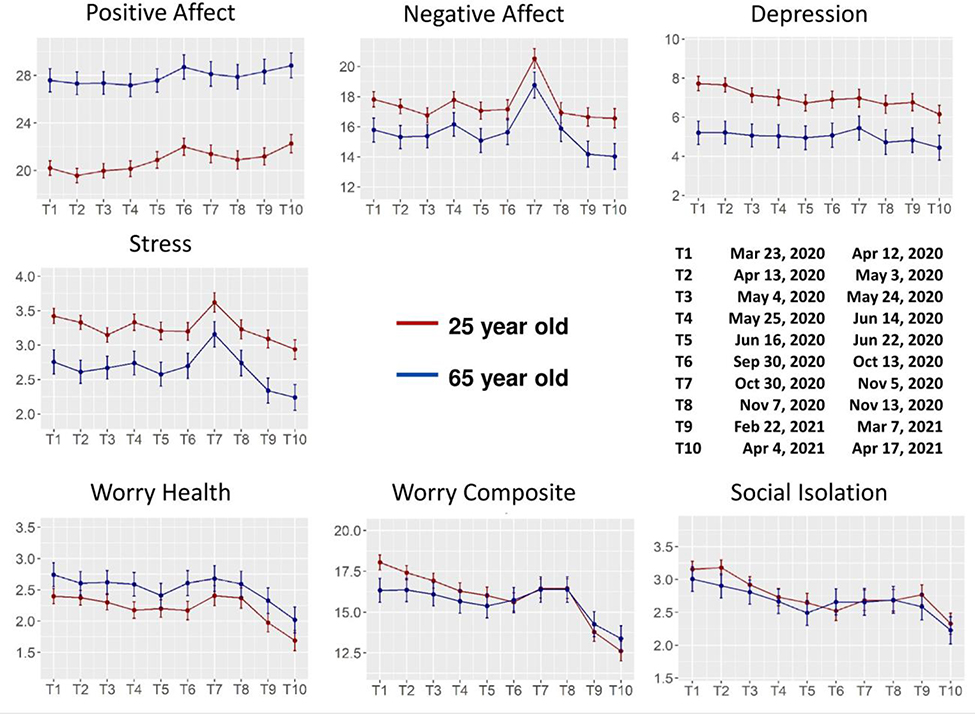

Change in each DV examined across time bins in younger and older adults are shown in Figure 1. Main effects of Age are shown in Figure 2. Coefficients, standardized effect sizes, and inferential statistics for each Age x Time model are reported for all DVs in Supplementary Materials.

Figure 1. Model estimates by time bin and age.

Plots show the model estimate for a 25 year old (in red) and a 65 year old (in blue) for each time bin (T1-T10), along with the confidence interval for each estimate (note that age was a continuous linear predictor in the analyses, and these two ages were chosen purely for visualization purposes). Older age was associated with higher positive affect and lower negative affect, depression, and stress. This effect was largely consistent across time bins and the Age x Time Bin interaction was not significant. Age differences in the worry composite were reduced over time, while older adults maintained greater worry about their personal health. There were no age differences in subjective social isolation. The possible range of scores for each scale was as follows: Positive affect: 10–50; Negative affect; 10–50; Depression: 0–24; Stress: 0–6; Worry Health: 0–6; Worry Composite: 0–24; Social Isolation: 0–6.

Positive and Negative Affect, Depression, and Stress

As shown in Figure 1, stress, negative affect, and depression tended to decrease across the course of the pandemic while positive affect increased across the pandemic (main effect of Time Bin: all ps < .001). Overlaid on these long-term trends, stress and negative affect showed a small increase at the time of the George Floyd murder (T4) and a larger increase during the time of the US Election (T7)2, while depression and positive affect appeared less sensitive to these events.

Despite the significant change in these measures across time bins, and their differential sensitivity to the progression of the pandemic and current events, effects of Age were remarkably consistent over time (see Figure 1). Increasing age was associated with greater positive affect and reduced negative affect, stress, and depression (main effect of Age: all ps < .001). These effects only differed significantly across time bins for stress (Age x Time Bin interaction: p = .044), which showed a greater decrease for younger adults early in the pandemic (T3-T2) and a greater decrease later in the pandemic for older adults (T9-T8). However, these differences remained relatively small in relation to the overall main effect of Age. Main effects of Age collapsed across time bins can be seen in Figure 2.

Worry and Social Isolation

As shown in Figure 1, worry measures and social isolation generally decreased across the span of the pandemic (main effect of Time Bin: p < .001 for all measures). Worry measures increased somewhat in the fall of 2020 (T7 and T8) and showed particularly large decreases in the 2021 time bins (T9 and T10).

Worry about individual health was the only measure examined in this paper to show worse affective outcomes with increased age (main effect of Age: p = .002). This effect did not differ across time bins. The Worry Composite and Social Isolation showed no main effect of age (ps >0.3). Social Isolation also showed no significant Age x Time Bin interaction (p = 0.104). For the Worry Composite, there was an Age X Time Bin interaction (p < .001). This appeared to be driven by reduced worry with older age early in the pandemic with a diminishing age effect over time, but none of the individual coefficients for this interaction were significant.

Discussion

Multiple studies conducted in the spring of 2020 revealed that, at least in high-income countries, older age was associated with better self-reported affective outcomes in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Birditt et al., 2021; Carstensen et al., 2020; Cunningham et al., in press; Czeisler et al., 2020; González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Klaiber et al., 2021; Vahia et al., 2020; Varma et al., 2021; Wilson et al., 2021). Here, we reveal that this age-related pattern can persist across the course of the pandemic and in response to more short-term current events that impact emotional well-being. This study reveals that increased positive and decreased negative affective outcomes associated with older age were remarkably consistent across multiple metrics and across metrics that show different trajectories over the course of the pandemic. Importantly, these benefits related to older age existed even though older age was not associated with decreased feelings of social isolation or worry about the pandemic. In other words, while adults of all ages experienced worry and social isolation, older age was associated with fewer negative mental health outcomes.

Prior work has suggested that older adults can show resilience in the face of stressors, but it has been hard to ascertain how well these findings would hold under the presentation of chronic stressors. Of course, aging brings with it the presence of multiple stressors (e.g., the majority of older adults experience pain, Molton & Terrill, 2014), but the nature and time course of these stressors will vary, making a real-time, large-group assessment of their impact on mental wellbeing hard to implement. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided an important opportunity for such a study, with the entire U.S. population experiencing some level of elevated stress during the past year (e.g., Czeisler et al., 2020). The results of this study clearly demonstrate that the COVID-19 pandemic does not create a boundary condition on older adults’ ability to show resilience and better mental wellbeing. In line with prior findings (e.g., Carstensen et al., 2020), these results suggest that older age continues to be associated with better emotional well-being during a sustained and unavoidable stressor.

Two strengths of this study are particularly worth noting. First, we relied on real-time reports of affective experience rather than on retrospective reports. Because older adults can show a tendency to focus on positive content in memory (Ford, DiGirolamo, & Kensinger, 2016; Mather & Carstensen, 2005), asking older adults to retrospectively report how they were feeling may create biases that could exaggerate age differences in mental wellbeing. By asking adults how they are feeling right now, we were able to avoid this possible bias.

Second, by sampling frequently, and by tracking other co-occurring national events, we were able to disambiguate affective responses to the pandemic from affective responses related to other events. Had we not collected data at this frequency, it would have been easy to misattribute the increases in stress and negative affect in early November to the COVID-19 pandemic, as that corresponded to a time-period when many parts of the US were experiencing surges in case-rates (Stobbe, 2020). However, the transient nature of those increases instead suggests that they were likely connected to the U.S. election and not to the pandemic (see also analysis of international participants in the Supplementary Materials). Regardless of the cause of the spike in stress and negative affect in early November (and the smaller peak in early June), these changes provide further evidence of the robustness of age effects: For most measures we examined, age was associated with improved affective outcomes, and these differences were remarkably consistent across measures with different time-courses across the pandemic and across both long-term trends and short-terms spikes in affective outcomes.

At the same time, we must emphasize limitations of the population sampled here. We used a convenience sample of community-dwelling adults with access to technology, and our recruitment efforts, which relied heavily on recruitment of our former research participants and on word of mouth and social media posts, led us to a biased sample of primarily well-educated, White females, many residing in the Northeast. We would not necessarily expect the positive outcomes associated with older age in this sample to extend, for instance, to older adults without access to technology or to those who live in nursing homes and may have been surrounded by losses due to COVID-19. We also cannot speak to the relation between age and mental health among underrepresented minorities, who have experienced more negative consequences of the pandemic (Czeisler et al., 2020). While our results suggest that older adults demonstrate emotional resilience even in the context of a year-long, chronic stressor, these results do not imply that older adults will not benefit from or do not need policies and resources to buffer them from the stressors of the pandemic and future long-term stressors. They may, however, underscore that we cannot overlook the mental-health challenges that have been pronounced for younger and middle-aged adults.

In summary, the present results extend those reported earlier in the pandemic (Birditt et al., 2021; Carstensen et al., 2020; Czeisler et al., 2020; González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Klaiber et al., 2021; Vahia et al., 2020; Varma et al., 2021; Wilson et al., 2021), demonstrating age-related increases in emotional well-being. Throughout the ongoing stress of the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing age was associated with lower stress, lower negative affect, and lower depressive symptoms, as well as more positive affect. These relationships with age remained across measured time points from March 2020 to April 2021, and persisted during parts of the year that contained other co-occurring national events that elevated overall stress and negative affect across all ages. Though we cannot make claims about the specific mechanisms that underlie these age-related benefits, the current data provide important evidence on potential boundary conditions for increases in measures of emotional well-being with age by showing that these advantages were maintained and consistent even in response to a sustained stressor that presented particular dangers to the health of older people.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from Boston College and a Small Research Grant from the Sleep Research Society Foundation. ECF and TJC would like to thank their NIH T32 funding sources for supporting their work and ongoing training. ECF was funded by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) NRSA T32 NS007292 through Brandeis University during this work. TJC was funded by the Research Training Program in Sleep, Circadian and Respiratory Neurobiology (NHLBI T32 HL007901) through the Division of Sleep Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham & Women’s Hospital.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

These estimates were weakly correlated with age, with older adults being slightly more likely to estimate a longer duration (Kendall’s tau = .048, p = .030).

Exploratory analyses revealed that participants outside the United States did not show the increase in T4 and showed a smaller increase in T7, supporting the interpretation that these spikes were due to these U.S.-based current events (see Supplementary Materials).

Data availability statement

All data used in this study is part of the Boston College COVID-19 Sleep and Well-Being Study, which is available at https://osf.io/gpxwa/.

References

- Birditt KS, Turkelson A, Fingerman KL, Polenick CA, & Oya A (2021). Age differences in stress, life changes, and social ties during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for psychological well-being. The Gerontologist, 61(2), 205–216. 10.1093/geront/gnaa204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG (2003). Depression in late life: Review and commentary. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 58(3), 249–265. 10.1093/gerona/58.3.M249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney AK, Graf AS, Hudson G, & Wilson E (2021). Age moderates perceived COVID-19 disruption on well-being. The Gerontologist, 61(1), 30–35. 10.1093/geront/gnaa106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Shavit YZ, & Barnes JT (2020). Age advantages in emotional experience persist even under threat from the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Science, 31(11), 1374–1385. 10.1177/0956797620967261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST (2010). Strength and vulnerability integration: A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 136(6), 1068–1091. 10.1037/a0021232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham TJ, Fields EC, Garcia SM, & Kensinger EA (in press). The relation between age and experienced stress, worry, affect, and depression during the spring 2020 phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Emotion. 10.1037/emo0000982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham TJ, Fields EC, & Kensinger EA (2021). Boston College daily sleep and well-being survey data during early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific Data, 8(110). 10.1038/s41597-021-00886-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler ME, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, … Rajaratnam SMW (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(32), 1049–1057. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JH, DiGirolamo MA, & Kensinger EA (2016). Age influences the relation between subjective valence ratings and emotional word use during autobiographical memory retrieval. Memory, 24(8), 1023–1032. 10.1080/09658211.2015.1061016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos MA, Saiz J, López-Gómez A, Ugidos C, & Muñoz M (2020). Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 87, 172–176. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi R, & Jones S (2020). Demonstrations & political violence in America: New data for summer 2020. ACLED: Bringing Clarity to Crisis. Retrieved from https://acleddata.com/2020/09/03/demonstrations-political-violence-in-america-new-data-for-summer-2020/ [Google Scholar]

- Klaiber P, Wen JH, DeLongis A, & Sin NL (2021). The ups and downs of daily life during COVID-19: Age differences in affect, stress, and positive events. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(2), e30–e37. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Jeong GC, & Yim J (2020). Consideration of the psychological and mental health of the elderly during COVID-19: A theoretical review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21). 10.3390/ijerph17218098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, & Carstensen LL (2005). Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(10), 496–502. 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molton IR, & Terrill AL (2014). Overview of persistent pain in older adults. American Psychologist, 69(2), 197–207. 10.1037/a0035794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson NA, & Bergeman CS (2021). Daily stress processes in a pandemic: The effects of worry, age, and affect. The Gerontologist, 61(2), 196–204. 10.1093/geront/gnaa187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolich-Zugich J, Knox KS, Rios CT, Natt B, Bhattacharya D, & Fain MJ (2020). SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 in older adults: what we may expect regarding pathogenesis, immune responses, and outcomes. GeroScience, 42(2), 505–514. 10.1007/s11357-020-00186-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchal N, Kamal R, Cox C, & Garfield R (2021). The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/ [Google Scholar]

- Pearman A, Hughes ML, Smith EL, & Neupert SD (2021). Age differences in risk and resilience factors in COVID-19-related stress. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(2), E38–E44. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza JR, & Charles ST (2006). Mental health among the baby boomers. In Whitbourne SK & Willis SL (Eds.), The Baby Boomers Grow Up: Contemporary Perspectives on Midlife (pp. 111–146). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Stobbe M (November 11, 2020). US hits record COVID-19 hospitalizations amid virus surge. Associated Press. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/doctors-better-equipped-virus-surge-743c0448c3ada001d327d73a6f2ed9d7 [Google Scholar]

- Vahia IV, Jeste DV, & Reynolds CF (2020). Older adults and the mental health effects of COVID-19. Journal of the American Medical Association, 324(22), 2253–2254. 10.1001/jama.2020.21753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma P, Junge M, Meaklim H, & Jackson ML (2021). Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: A global cross-sectional survey. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 109, 110236. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, & Clark LA (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule - Expanded Form. University of Iowa. Retrieved from 10.17077/48vt-m4t2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead BR (2021). COVID-19 as a stressor: Pandemic expectations, perceived stress, and negative affect in older adults. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(2), e59–e64. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Lee J, & Shook NJ (2021). COVID-19 worries and mental health: The moderating effect of age. Aging & Mental Health, 25(7), 1289–1296. 10.1080/13607863.2020.1856778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe HE, & Isaacowitz DM (in press). Aging and emotion regulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging & Mental Health. 10.1080/13607863.2021.1910797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZY, & McGoogan JM (2020). Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(13), 1239–1242. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young NA, Waugh CE, Minton AR, Charles ST, Haase CM, & Mikels JA (2021). Reactive, agentic, apathetic, or challenged? Aging, emotion, and coping during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Gerontologist, 61(2), 217–227. 10.1093/geront/gnaa196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study is part of the Boston College COVID-19 Sleep and Well-Being Study, which is available at https://osf.io/gpxwa/.