Abstract

Black adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) are disproportionately affected by HIV in the southern U.S.; however, PrEP prescriptions to Black AGYW remain scarce. We conducted in-depth interviews (IDIs) with Black AGYW ages 14-24 in Alabama to explore opportunities for and barriers to sexual health care including PrEP prescription. Twelve AGYW participated in IDIs with median age 20 (range 19-24). All reported condomless sex, 1-3 sexual partners in the past 3 months, and 6 reported prior STI. Themes included: 1) Stigma related to sex contributes to inadequate discussions with educators, healthcare providers, and parents about sexual health; 2) Intersecting stigmas around race and gender impact Black women's care-seeking behavior; 3) Many AGYW are aware of PrEP but don't perceive it as an option for them. Multifaceted interventions utilizing the perspectives, voices, and experiences of Black cisgender AGYW are needed to curb the HIV epidemic in Alabama and the U.S. South.

Keywords: adolescents, HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual health, women and girls, U.S. South

Introduction

Black adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) experience a disproportionate risk of HIV exposure and acquisition in the United States (U.S.). In 2019, Black women accounted for 55% of HIV diagnoses among females, despite making up only 13% of the U.S. female population. 1 These disparities are amplified in the South, which accounts for the greatest regional HIV incidence. 2 In the South, Black women account for 67% of incident HIV diagnoses among women. 3 In Alabama, adolescents and young adults are at high risk of contracting HIV, with more than half (52%) of all new HIV infections occurring in those 13-29 years old in 2018. 4

Effective HIV prevention interventions are critical within the southern U.S., which continues to underperform in the provision of prevention and treatment services despite higher rates of HIV diagnosis. 3 HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) dramatically reduces the risk of HIV transmission, 5 but only 27% of U.S. PrEP use is in the South, despite accounting for more than half of incident HIV cases.3,6 Black men and women are nearly six times less likely than their White counterparts to receive a PrEP prescription. 7 A nationwide study of Black women's preferences for PrEP products found that 32% of 315 respondents were aware of PrEP, and 41% were interested in using it. 8 Despite interest in PrEP, only 2% of women with PrEP indications were prescribed the medication in 2016, 7 and less than one fifth of all PrEP prescriptions are prescribed to those ages 12-24, with <2% to those under 18 years of age. 9 A recent analysis of 429 adolescents at an adolescent primary care center in urban Alabama found 45% were eligible for PrEP based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guidelines from 2018, 10 77% were female and 95% identified as heterosexual, 11 but zero eligible adolescents received prescriptions. 11

Qualitative research exploring barriers to PrEP use among Black AGYW in the South is limited, and more data are needed to understand the intersecting stigmas experienced by this population. Understanding intersectional stigmas requires analysis of the racial, sexual, gender, and class-based systems of oppression that influence the behaviors and health of Black AGYW.12,13 In the southern U.S., intersectional stigma is greatly influenced by faith-based organizations that have historically denounced behaviors associated with HIV, including sexual activity among youth.14,15 While sexual health education is not mandated in Alabama public schools, those that do offer this curriculum are required to emphasize abstinence as the “expected social standard” for unmarried people, 16 despite studies indicating an association between abstinence-only education and higher rates of sexual activity among youth.17,18 The state continues to interfere in the sexuality and gender of youth, including passing AL SB184 in April 2022, which criminalizes the prescription or administration of gender-affirming medications and procedures for the treatment of gender dysphoria in youth under the age of 19. 19 This example of intervention stigma, which affects providers and clients who engage in a medical treatment that is deemed socially unacceptable, 20 highlights the stigmatization of sexual health in Alabama. The culture of shame and guilt around sex, influenced by religiosity, shapes young women's sexual behaviors and mental health into their adulthood,21,22 and such stigma towards sex and sexual health interventions may impact interest in and uptake of PrEP.

Lagging PrEP uptake in the South has been attributed to multiple factors, including high rates of poverty, low rates of health insurance, poor healthcare capacity, geographical barriers, low health literacy, and stigma surrounding sex and sexuality, especially for minoritized populations. 23 Disparities in PrEP usage between high and low uptake states have only increased over time, suggesting that underperforming regions will not improve without intervention. 24 Compared to other regions of the country, the South reports the greatest proportion of residents living in rural areas and has the highest number of “PrEP deserts,” in which one-way drive times to the nearest PrEP provider exceed 60 minutes. 25 Limited PrEP knowledge is an additional barrier to PrEP uptake.26,27 Further exacerbating this issue is the high prevalence of HIV-related medical mistrust present in the Black community, levels of which correlate with willingness to initiate PrEP.27,28 Low self-perceived risk was the most commonly cited reason for PrEP avoidance in individuals with PrEP indications. 26 Though barriers and promoters of PrEP prescription are well studied among adult men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women, this study fills an important gap in research on PrEP for adolescent populations, especially Black AGYW, who are disproportionately vulnerable to HIV infection.

The aim of this research was to explore potential barriers and facilitators to PrEP usage among Black AGYW across rural and urban communities in Alabama. In order to promote PrEP uptake among Black AGYW, we conducted a qualitative study to evaluate youth understandings of and experiences with sexual health including PrEP access in Alabama. Using qualitative data gathered from AGYW across Alabama, we hope to illuminate the complex socioeconomic and cultural barriers to PrEP usage among Black AGYW.

Methods

Participants

We recruited Black AGYW ages 14-24 living in Alabama who either used PrEP in the past or met criteria for PrEP use in the past year (>35 kg, HIV-negative, prior sexually transmitted infection(s), sexually active with inconsistent condom use, injection drug use, or transactional sex work). Participants were solicited through Facebook advertisements, university-related social media, flyers distributed within student activity groups related to sexual health, national pan-Hellenic societies, and through community partnerships and campus health centers in Tuskegee, Birmingham, and Tuscaloosa. Additionally, participants were invited to share the study information with peers.

Eligible participants were 14-24 years old and able to provide informed consent, identified as Black or African American and as a cis- or transgender female, and had either accessed or met criteria for PrEP, as described above.

Conceptual Frameworks

This research was grounded in Andersen's Behavioral Model of Health Service Utilization, 29 which describes three main factors that contribute to accessing health services. Predisposing factors focus on demographic and social information. Enabling factors illustrate larger organizational structures including policies, finances, and infrastructure. Need factors describe both an objectively measured and individually perceived need for a service. 30 This framework has been used previously to describe HIV care utilization.29,31,32 Further we use constructs from the Situated Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skill Theoretical Framework for Intervention Development which describes a feedback loop between information, motivation and skills in the continuity of care. 33

Interview and Analysis Procedures

Potential participants could scan a QR code on the recruitment flyer to access an information sheet about the study and complete an eligibility screening questionnaire, which asked about their HIV serostatus, prior PrEP use, sexual behaviors (ie, condom use, number of partners, STI experiences, etc), and substance use. Eligible AGYW were invited to participate in an in-depth interview (IDIs) and, if interested, could provide their contact information at the end of the screener. Interested participants were then automatically directed to a brief demographic questionnaire, which collected their age, race/ethnicity, gender identity, home zip code, education, who they live with, occupation, marital status, and gravidity/parity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of Interviewed Participants.

| N = 12 | ||

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | ||

| Age | Median (Range) | 20 (19-24) |

| Education | 12th grade | 1 (8) |

| Some college | 7 (58) | |

| Associate degree | 1 (8) | |

| Bachelor's degree | 3 (25) | |

| Who do you live with? | Parents | 6 (50) |

| Roommates | 2 (17) | |

| Alone | 4 (33) | |

| Rurality of home zip code | Urban/suburban | 11 (92) |

| Rural | 1 (8) | |

| Have you ever used PrEP? | No | 12 (100) |

The research coordinator contacted interested participants to schedule IDIs, which were administered by gender-concordant research assistants with prior experience working with AGYW. Informed consent was collected verbally prior to the start of the IDI. Interview guides were developed by our research team using the conceptual frameworks mentioned above and piloted with adolescents. Guides examined general and sexual health experiences and preferences, parental involvement, social support, HIV prevention, partnership dynamics, and understandings and perceptions about PrEP. Interviews were conducted using Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant institutional Zoom or telephone calls, recorded via handheld audio recorder, and lasted for approximately 1 hour. After completing the IDI, the research coordinator provided a PrEP Facts information sheet and offered participants the opportunity to ask any outstanding questions regarding PrEP access. After completion of the interview, participants received a copy of the informed consent document for their records. Participants were provided with a $30 reimbursement for their time. Interviews were transcribed by the research coordinator and subsequently reviewed by three team members for quality and accuracy. Any potentially identifying information, including the names of participants or their family members, or any details regarding locations were anonymized.

Descriptive statistics were generated using initial survey data. An inductive content analysis approach was utilized to analyze transcripts.34,35 All interview transcripts were read and discussed by four team members to identify emergent themes. A codebook was developed based on these themes and constructs from our conceptual frameworks, including environment and population characteristics, sources of information, PrEP-use motivations, and HIV risk-perception. The transcripts were analyzed using the developed codebook, and quotes were assigned to specific constructs within the broader themes. Two interviews (17%) were coded by two team members (intercoder reliability kappa statistic of 0.96), and the remaining 9 transcripts were coded by one team member each, with frequent discussion among the team to ensure consistency across transcripts. NVivo 12 software was used to organize the analysis. The overarching themes were mapped back to constructs from the conceptual frameworks described above. The identified emergent themes are described below.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

This study was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham's Institutional Review Board (Approval Number IRB-300004672). All participants verbally provided voluntary informed consent to participate in the study. Written consent was waived as all interviews were conducted remotely due to COVID-19 precautions.

Results

Participant Characteristics

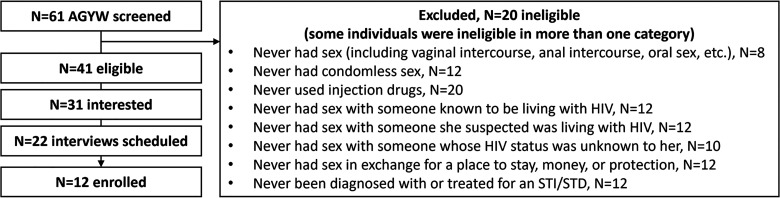

Sixty-one AGYW were screened for eligibility, 41 were eligible to participate, 31 were interested in participating and completed the demographic questionnaire, 22 interviews were scheduled, and twelve AGYW enrolled and completed an interview (Figure 1). Interested participants were contacted at least three times by email and telephone to schedule an interview, and up to three attempts were made to reschedule canceled or missed interviews.

Figure 1.

Participant eligibility and enrollment.

Twelve young women ages 19-24 participated in in-depth interviews (IDIs). All self-identified as a Black/African American girl/woman, HIV-negative, and sexually active. All had finished at least 12th grade, and four had a two- or four-year degree (Table 1). Nine (75%) had 1 sexual partner in the last three months, and all reported past condomless sex. Half (N = 6, 50%) reported ever having been diagnosed with or treated for an STI, and none had used PrEP (Table 2). Participants represented nine Alabama counties.

Table 2.

Risk Factors for HIV Acquisition.

| N = 12 | ||

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | ||

| Number of sexual partners in last 3 months | 1 | 9 (75) |

| 2 | 1 (8) | |

| 3 | 2 (17) | |

| Have you ever had sex without a condom? | Yes | 12 (100) |

| Have you ever had sex with someone known to be living with HIV? | No | 12 (100) |

| Have you ever had sex with someone who you suspected might be living with HIV? | No | 12 (100) |

| Have you ever had sex with someone whose HIV status was unknown to you? | Yes | 7 (58) |

| Have you ever had sex in exchange for a place to stay, money, or protection? | No | 12 (100) |

| Have you ever been diagnosed with or treated for a sexually transmitted infection, or an STI or STD? | Yes | 6 (50) |

| What type of substances, if any, have you used in the past? | Tobacco | 3 (25) |

| Alcohol | 11 (92) | |

| Marijuana | 8 (67) | |

| Other | 0 (0) |

Emerging Themes

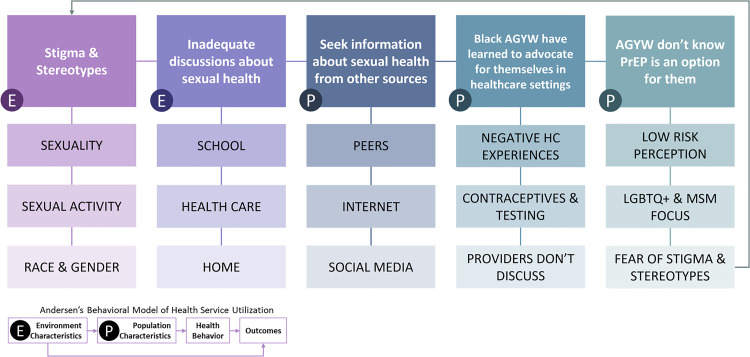

Participants described their desire to learn about sexual health at an early age from trusted sources like parents, educators, and healthcare teams. Most participants described a lack of providers or other advocates who could provide sexual health advice, and AGYW participants learned how to navigate their own sexual health care. The intersectional stereotypes, stigma, racism, and sexism experienced by participants and their peers, family members, and social media influencers impacted their willingness to seek care. Nonetheless, they wanted providers to discuss sexual health and HIV prevention options with them, even when they did not perceive themselves as at risk for HIV acquisition. Figure 2 maps these intersecting factors to Andersen's Behavioral Model of Health Service Utilization, 29 including environment characteristics like community stigma related to sex and sexuality and population characteristics like self-advocacy and HIV risk perception. The themes below explore these constructs in more depth.

Stigma around sexuality and sexual activity in young cisgender women contributes to inadequate discussions with educators, healthcare providers, and parents about sexual health.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model of Intersecting Themes

Legislation in Alabama limits sexual education in public settings, emphasizing abstinence as the “expected social standard”. 16 Most participants described inadequate sexual education and reported negative experiences with school-based sexual education that perpetuated heteronormative and outdated gender norms and potentially exacerbated gender-based violence.

You get kind of burned out from all the scare tactics that you’re given, especially in high school, especially as a woman in the South … you just don't care after a while. … Having comprehensive sex ed in schools, having someone who actually knows about it, not just your football coach … someone who actually cares; someone who's going to talk about consent first day of class, talk about rape. – #62, age 22

AGYW want knowledgeable, trusted adults to initiate and continue discussions about sexual health starting at a young age to normalize the topic and stimy the stigma.

I think doctors should be the one[s] to lead sex ed in high schools. I think it needs to be a mandatory class taught for sex ed, because in the South, it's pretty “abstinence, abstinence.” But, let's be honest, teenagers have hormones, teenagers are curious. People are curious. I’m not saying everybody's having sex. But it's a pretty fairly open topic now in today's world. So, if they come into the schools and actually talk to students and let them know the myths and actual facts about different things when it comes to sex, I think people will be more willing to open up and speak in those discussions. – #06, age 22

For many of the young women, sexual health discussions at home are limited, leaving them wanting more information but not feeling comfortable asking for it. This is exacerbated in their communities where race, gender, religious, and cultural norms intersect often making sexuality a taboo topic.

One participant described the sources of information that taught her about sexual health. She explained that discussions at school, in healthcare, and with her parents were brief and uninformative, so she turned to social media as her primary resource.

[Sex ed in school] was really just us studying a diagram of a vagina or a penis. It wasn't really about sexual health, or reproduction, or anything. It was just “these are your sexual organs”. … I remember being 12 or 13 years old and my mom being like, “You have to have sex to make a baby. It might hurt. You should avoid having sex at all costs.” That was it. … On Snapchat, there's different articles and magazines and stuff. There's Teen Vogue and Refinery29, all that stuff. They actually give in-depth, pretty good information regarding sexual health, and pleasure, and all of those things. It seems like it's aimed towards teenagers, so I learned a lot of stuff from that. Just social media in general, Instagram, Tumblr… – #37, age 20

This participant experiences that the cultural taboo around sex and sexuality is lessened on social media, where more sources of information give youth opportunities to learn in a more casual environment.

I think that society, as a whole, should just be super comfortable with talking about sex, because it's been here forever and it's going to be here forever… We should be able to talk about it… I think the thing about putting [sexual health] information on Instagram, is it's sandwiched in with everything else, so it's not a big deal. It's just casual sexual health. Here's what you need to know. – #37, age 20

Limited healthcare provider engagement in sex-positive discussions, possibly influenced by widespread community stereotypes and stigma related to adolescents having sex, may diminish the breadth and number of discussions happening in the lives of AGYW.

Unconsciously, bias can impact how you interact with your patients. There are some providers that can separate their opinions and feelings from their practice. But then, the ones that don't make it difficult for people who need sexual health information, or birth control, or to get tested, because their personal belief is, maybe, someone your age shouldn't be [having sex]. Or maybe someone your age couldn't be having any issues related to sex, because you’re so young. …They’re like, “Oh, you’re too young to do anything, I’m not going to test you for that…” – #07, age 21

Cultural norms in the South, heavily rooted in racism and stereotypes, influence AGYW's interactions with the healthcare system, and providers’ implicit biases pervade the care decisions they make for and with Black female clients. Stereotypes about the promiscuity of Black women may lead some providers to dismiss the sexual healthcare needs of this population, even when the client directly asks for what they need. Such experiences have taught Black AGYW to advocate for themselves, even when their providers do not.

For example, in society, they have ideas that Black women are promiscuous and it's innate. There might be a time when I’m with a physician that genuinely believes something like that, so when I bring up something, they’ll dismiss it and think it's nothing, because in their mind, they’re like, “Oh, well, people like that be doing stuff, so it's not as important.” – #07, age 21

2. Intersecting stereotypes and stigmas around race and gender impact young Black women's intentions to seek out healthcare for their sexual health needs.

Racism, racial profiling, and stereotypes in the U.S., and specifically the South, contribute to the viewpoints of Black AGYW on the health of their communities. Further, community dialogues surrounding Black women's sexuality are heavily influenced by race and gender stereotypes, contributing to internalized stigmas experienced by AGYW. Below, one participant describes HIV and sexuality within the Black community. The language she uses to discuss her community suggests she has internalized some of these stereotypes that she has heard and experienced. Her full interview offers insight into her experiences with stigma, stereotypes, health disparities, sexual trauma, mistrust, and STIs. The following quotes capture some of the racist messaging present in Alabama that the participant applies to her understandings of sexual health in Black communities.

Nowadays, it's like the rate for AIDS [or] any sexually transmitted diseases, they’re in African Americans due to not really caring about their health and us having a lower rate of good health. Our good health is not really up to par with others. It's just we have low health. We have that “don't care” attitude. – #15, age 19

[To lower rates of HIV] in Alabama specifically, for more [people] to remain abstinent because can't nothing happen if you’re abstinent and to lower the [number] of sexual partners… Not to be cruel, but just make sure they get off the streets. If a police officer sees them, I prefer them be locked up instead of them being on their deathbed from a sexually transmitted disease. – #15, age 19

Other participants describe the stereotypes they face and how they expect to be treated by healthcare providers if they bring up topics related to sexual health. The following participants describe how racist and gender-based stereotypes impact access to care and create health disparities. These women call for the broader community to be more culturally competent and nonjudgmental to improve health disparities.

A lack of cultural competence can definitely make going to the doctor more difficult, especially as an African American woman. I have to say that we don't have good health literacy, but sometimes they don't seem like they want to put too much effort into helping us prevent getting STDs in the future. I think more health education is needed in that sense, and kind of understanding our culture more. They could just assume that us as Black people, we don't really care about our health, and we just have a lot of unprotected sex with people we don't know. They might not even take the time to really educate us on how to stay safe. They kind of just prescribe us this, and then they might have an expectation that we’ll be back again. – #25, age 23

Since I am Black, I feel that the stereotype is, like, we get pregnant young, and we have HIV and also, we are not knowledgeable because we don't read books or whatever. Or we don't seek out help or go to the doctor to ask for help. We just feel like we can do it on our own. So, it really affects us when we’re trying to go get help, because we feel like everybody's going to judge us, everybody's going to have something negative to say. I know some of my decisions aren't the best decisions, but when we try to seek out help, there's always somebody that's going to judge you… We don't be needing anyone to judge us, we need somebody there to help and hold our hand and take us to the right path. That's what we really need. – #39, age 19

Negative healthcare experiences shared by social media influencers, peers, family, and past personal encounters, impact how AGYW perceive healthcare providers and the care they receive. Several participants described hearing stories on social media of Black women being mistreated in healthcare, ultimately making them question their own experiences and anticipate the worst in healthcare situations. They suggest cultural competence and implicit bias training may be a step towards improving Black women's relationships with healthcare.

You always hear that Black women go and they’re most likely to not get the proper care that they need, so I will say that that language, just hearing it will kind of have you second-guessing yourself and does this doctor really care about me. …It's just really disheartening when you’re going to the doctor as a young woman because you’re focusing on, “Am I getting the proper care I need, are they telling me this because I’m a Black woman?” – #26, age 24

My mother's gynecologist is a White man. He dismisses her at times. She doesn't feel like she's being heard. This has been going on for years. She's had some issues and her doctor brushed it off. … I didn't really want to go through any of that. Especially since this is my first time discussing sexual health with the doctor. – #37, age 20

Many participants describe how they ask providers for the care they need, specifically related to different birth control options and STI testing. They have learned to request specific STI tests, as routine panels often exclude HIV and herpes simplex virus.

I think that there should be more emphasis on HIV testing, because … a lot of people don't know that HIV testing is separately done. They think if nothing came back for the STI check-up, then they don't have anything… It's not really emphasized in doctors’ offices either because I know for me when I get my STI check-ups done, I’ve never been asked, “Do you want to get an HIV checkup?” … They don't really tell you, they just kind of go along with what you ask for. – #05, age 20

Some participants describe advocating for their sexual health needs when providers weren't taking them seriously.

It was at [campus health center] that they put in my new Nexplanon as a freshman, and I continuously bled. I kept going back telling them, “It's been three months, I’ve continuously had a period. I can't even be sexually active if I wanted to. I would like to do something about it.” But the ladies kept pushing it to where it's almost after a year of being on it, I was still bleeding. Then they were like, “Okay, we can move to a different one.” …That was one experience that was very uncomfortable for me. – #07, age 21

Sometimes when you do ask questions about sexual health, [providers] will just give you a general answer, and then I just have to go off of that. Even when I was going to the [campus health center] my freshman year or my sophomore year, I was having recurring yeast infections coming back. I probably went to the [campus health center] at least six times in like four or five months. They just kept telling me the same thing over and over, basically saying that it was an overgrowth of good bacteria, or something of that nature, but it's like, me having to come back continuously for the same issue. I was kind of getting a little bit upset, because why is this the only answer that you’re able to give me? Like there's a reason that it keeps coming back around. I’m having to constantly come back and get a prescription and take medication to get it to go away? Are there not any other remedies? But without me asking those questions, they weren't really giving me the information. – #05, age 20

Participants describe ways they think clinical care and provider interactions can be improved.

I think one thing is putting those biases aside and actually listening to [women and girls], making it a shared decision-making process versus it being just [providers] pushing what they think, without hearing [the patients]. Because you can't make a diagnosis on something properly without actually hearing what the person is saying or hearing what's going on. Even as a doctor, you may not want to go through a procedure, you may not want to do this. But if you have a patient saying, “Hey, I would like to try this, or I feel this,” then it is your duty to actually go through it, and be like, “We’ll see how it is,” not just dismiss them, because that's how people die. Or that's how people get worse. That's how Black people don't want to go to the doctor. – #06, age 22

3. While many AGYW are aware of PrEP, they don't perceive it as an option for them.

Many participants describe a lack of conversations about HIV with their providers, contributing to low rates of PrEP prescription and unfamiliarity with PrEP as an HIV prevention method.

[HIV] hasn't come up [with a provider]. And this kind of goes back to that it's just not talked about enough; it's not brought up enough. Because even after finding out that I had human papillomavirus (HPV) or when I was going to the health and wellness center every few months or whatsoever, it was never brought up. I didn't think about bringing it up. Because you know, in my head, I’m dealing with what's currently going on right now at the moment. But it was also never brought up by a physician either. I think before [providers] even go into more information on PrEP, there should be more information on HIV itself… I think that’ll be the first step. Because if you’re just asking someone, “Are you interested in the PrEP?” If they’re not even fully aware of what HIV is, they’re probably going to say no. – #05, age 20

Providers do not often bring up PrEP up with their AGYW clients, and sources of PrEP information outside of healthcare often target MSM and transwomen, leading AGYW to believe it is not an option for them unless they research PrEP on their own.

I feel like something like PrEP might only be brought up if you’re a gay man or something like that, obviously. If you’re obviously like having sex with gay men, or you’re in a part of the LGBTQ community, then that might be the only time that it's brought up. – #37, age 20

Many participants discussed how most people in their communities have never heard of PrEP. Potential community reactions to PrEP prescriptions were expected to be negative, and the women described potential stigmas related to sexuality, sexual activity, and HIV that might make some people hesitant to initiate or even learn more about PrEP. HIV stigma intersects with sex-related stigma, creating intervention stigma that may deter clients and providers from engaging in PrEP prescription and care.

I think that nobody wants to have a conversation about, “I’m trying to protect myself from HIV,” because then it's like you’re out there having sex with people with HIV. That could be frowned upon… It's still looked down upon. Even chlamydia or things that people can “get rid of,” it's like if you’re preparing yourself for that possibility, it's going to be viewed as you’re having sex with people who have HIV, which then you’ll be looked at as “dirty”. – #26, age 24

I guess to most people, [PrEP] is associated with the queer community. I guess people don't wanna be outed or associated with the queer community… I’m surrounded by a lot of conservatives, religious, anti-sex people, so I think my community would be very hesitant to learn anything about it or to talk about it at all. – #37, age 20

Others described how their peers feel invulnerable to HIV infection, leading them to be disinterested in PrEP and other prevention strategies.

Some people feel like medicine doesn't work. Some people feel that they don't need to take it because like I said, they can't be touched, like, nothing wrong is going to happen. And they can't catch anything. Like they’re invincible to all the diseases and infections and all that. – #39, age 19

[My peers think] they don't need PrEP. They don't need it until they do need it. They trust their partners. They think that it's just for men who have sex with men. They just don't think it's necessary for them. – #62, age 22

While AGYW perceive their peers as at-risk for HIV acquisition, their perceived self-vulnerability is low. Many participants described how their risk of acquiring HIV is low because they use condoms, get tested, and have discussions with their partners, which are effective mechanisms of HIV prevention.

For the most part, I openly communicate with my partners. I’ve seen their test results; I get tested after I have sex with them because I know … it's my consequence too, I can't just blame it all on them… I think my chances are just like anybody else. But I would say I do take the safety precautions of being tested when I need to be tested, using condoms. – #06, age 22

Others discussed how STI experiences led them to abstain from sex for the time being, making their risk of HIV acquisition very low. Some mentioned their interest in PrEP might be different if they were “having sex all the time” (#39) or had multiple partners (#25, #37).

I don't care to have sex because, I’m not trying to get anything else… [A prior STI] really opened my eyes to what's really going on. I’m trying to be very careful about things… if I’m really not having sex, I don't feel the need to take more medicine [PrEP]. – #39, age 19

This sample of AGYW discuss their use of multiple methods of HIV prevention and cite monogamy as a reason for low interest in PrEP use, despite 58% (N = 7) reporting ever having sex with someone whose HIV status was unknown to them. One participant explains that her chances of getting HIV are low, but she recognizes that the risk is not only linked to her individual behaviors, but also to the behaviors of her partner.

I feel my chances are highly unlikely. I do protect myself, and not that it means that the person won't go out, but I’m in a relationship that we’re on our way to marriage. … It still can happen, but less likely. – #26, age 24

A few participants described how taking PrEP might be beneficial for them, even if they are not at a high risk of HIV acquisition, again recognizing that HIV risk in monogamous relationships is contingent upon the behaviors of both partners.

I think it would be beneficial only because when you look at disparities in HIV and AIDS within communities, Black people have higher risk of getting it in encounters and things of that nature. Even outside of that, when you look at young people, like a lot of us when it comes to sex, we make risky decisions in the moment. I think being able to have that resource would be beneficial on lowering the risk of it… But I also know the risk of me even having one partner, I could still get it. … I think it would be beneficial for everyone who's sexually active. Because once you start drinking and people smoke, and then they’re having sex, too, that can increase your risk as well. So, yeah … I think it would be something I want to do. – #07, age 21

Many participants were eager to have more information about PrEP, for themselves and AGYW like them.

I’m always open to all types of information regarding sexual health. So, everything that somebody can tell me that will help me and make me more knowledgeable. I’m willing to sit and talk, understand what they’re saying… – #39, age 19

I wouldn't mind speaking with the physician [about PrEP]. Even if I decided not to do it, there's nothing wrong with having the information in your hand … I think it's important to know your options. – #05, age 20

Discussion

Though Black cisgender AGYW are disproportionately impacted by HIV, 1 PrEP prescriptions for this population remain low.7,9,11 This qualitative study explored the sexual health experiences and perspectives of a sample of Black AGYW in Alabama. Young cisgender women experience unique internalized, anticipated, and enacted stigmas shaped by cultural, racial, and community stereotypes and norms that complicate their interactions with the health care system. Lack of discussions about sexual health across multiple settings leaves clients feeling unprepared for their sexual health appointments, leading them to seek out information from more accessible sources like friends and social media. Prior experiences with and/or anticipated poor quality healthcare influences the way this population interacts with their providers. Despite many barriers, this sample of women describe advocating for themselves, asking for what they want and need, and navigating complex systems of sexual health care. Clients are eager to learn more about PrEP, despite perceiving it as mostly for LGBTQ + populations, based on current marketing. They ask that providers listen to them, hear them without judgment, and help them achieve their sexual health goals, including pregnancy, STI, and HIV prevention. Our findings suggest that there are opportunities for PrEP prescriptions for this population, especially alongside routine contraceptive care that is already in place.

Cultural and religious norms and abstinence-only sexual health teachings drive sexual health stigma in the South and are not effective in mitigating sexual risk behaviors. 36 Most of the existing literature highlights stigma around sexual minority behaviors, especially among men who have sex with men; our findings show that sexuality-related stigma in the South spreads beyond these minoritized groups, impacting Black communities as a whole, including cisgender women having sex with men. Alabama's emphasis on abstinence as the “expected social standard” 16 may drive stigma against sexuality, especially among young Black women who experience intersectional stereotypes related to their sexual behaviors and reproductive choices. 37 Black youth in another rural southern state also cite abstinence-only sex education in public schools as a major barrier to HIV prevention within their community. 38 Other studies support our finding that sexual health discussions are also limited at home, though many participants in this study and others described surface-level discussions with mothers and trusted female adults about sexual health and contraception. 39 Stigma related to race and gender contributes to negative experiences with health care. There is a long history in the U.S. of Black patients facing discrimination and lower standards in U.S. health care systems, resulting in wide health disparities.40,41 A recent analysis of provider in-depth interviews (IDIs) explores provider comfort discussing sex with Black AGYW and multifactorial barriers to quality sexual health care for this population. 42 Black women who have sex with men are an overlooked population in discussions about HIV prevention who, in the South, may face similar stigma related to sexuality and sexual activity experienced by LGBTQ + communities.

Other studies support our finding that, while many Black AGYW may have heard of PrEP, they do not perceive it as an option for them. Among college-aged Black women surveyed in Georgia, 67% reported that they had not heard of PrEP and 72% felt unsure or apprehensive about starting the medication. 43 Women who had knowledge of PrEP were often only aware of the indication for MSM and did not realize it was available for women. 44 Awareness alone does not appear to be enough to motivate initiation of PrEP. Within a population of young adults attending Historically Black Colleges and Universities, 52% indicated prior knowledge of PrEP, however, only 3% reported current PrEP usage. 45 Among our sample of AGYW, many did not perceive themselves as at risk for HIV because they were in monogamous relationships. While having fewer partners may decrease their risk of HIV acquisition, relationships among this age group may be more transient than AGYW perceive, and heterosexual women's HIV vulnerability is more closely linked to their sexual networks than their individual behaviors. 27 Additionally, these AGYW were motivated to discuss sexual health, indicated by their willingness to participate in this study, and therefore are likely to be at lower risk of HIV acquisition than the majority of AGYW in Alabama, explaining their lack of interest in PrEP use for themselves.

When it comes to their sexual health, Black AGYW have learned to advocate for themselves. Our findings highlight the importance of including Black AGYW in conversations about improving sexual health education and healthcare and the need to address the underlying stigma AGYW face related to sex. Multi-level interventions are needed that prioritize empowerment of Black AGYW, their interpersonal relationships with guardians and healthcare providers, and community-level changes and advocacy for comprehensive sexual health education. Alabama needs policy changes to promote comprehensive sexual education that is accurate and evidence-based, with broad resources from health professionals to supplement school teachings. Education campaigns targeted at parents are needed to address the gap in the home setting. Academic healthcare programs need to prioritize training and retaining Black providers, particularly women. This will help establish an environment where Black AGYW share similar lived experiences with their providers, helping to develop an atmosphere of trust. Further training efforts among providers are needed to help promote uptake of PrEP among AGYW. All approaches need to consider race, gender, and socioeconomic status as intersecting identities that influence the risk of HIV infection and engagement with HIV prevention and care systems.27,46

The CDC's most recent PrEP guidelines recommend that all sexually active individuals, including men, women and adolescents, receive education from their providers about PrEP, 47 which may eliminate some experienced and anticipated stigmas and stereotypes faced by Black women regarding their sexuality, sexual activity, and risk of HIV infection. Routinizing discussions of PrEP with all patients may reduce provider biases related to HIV prevention for specific populations, especially in the South where AGYW experience discrimination and fear inadequate healthcare based on the negative experiences of themselves and their peers. Providers must familiarize themselves with these new guidelines, and medical residents should receive education on prescribing PrEP. Our team has been funded to implement an intervention with family medicine residents to encourage PrEP prescription and advocacy.

Limitations

We conducted this study during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this time period provided unique challenges, including virtual recruitment, enrollment, and interviews. Virtual recruitment required digital devices that could read a QR code, internet connectivity for screening and demographic surveys and Zoom interviews, and/or telephone service for phone interviews. We aimed to recruit AGYW from rural settings, but the technology requirements may have limited the ability to participate from rural locations. Our small sample may have been more interested in sexual health than the average Black AGYW in Alabama, and thus may not accurately represent the perspectives of all Black AGYW in Alabama. Further, our participants were older than our initial priority population, limiting our ability to reflect on the experiences of younger adolescents (14-18 years old). Social desirability bias may have played a role in these sensitive interviews. Additionally, qualitative data analysis is limited by presenting a small snapshot of the stories of many people; therefore, the quotes presented in this analysis may not capture the entire storyline for each individual participant, and all aspects of their discussions cannot be adequately discussed at one time. Despite these limitations, our study included a unique sample of individuals who provided rich information and insight into the sexual health experiences of Black AGYW living in Alabama.

Conclusions

Black cisgender AGYW are often overlooked when it comes to PrEP for HIV prevention. This qualitative study highlights the underlying intersectional stigma and stereotypes, lack of evidence-based sexual health education, and low risk perception which may contribute to the disparities in PrEP uptake among Black AGYW in the South. There are many opportunities for PrEP prescriptions for this population, driven by sex-positive provider-initiated discussions, social media campaigns, empowerment of AGYW, and legislative changes to school-based sexual health education. A multifaceted approach utilizing the perspectives, voices, and experiences of Black cisgender women and girls can catalyze forward progress in sexual health and curbing the HIV epidemic in Alabama and the South.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: MCP: Data collection; Analysis; Manuscript Preparation.

SJ: Analysis; Manuscript Drafting and Review.

SVH: Conceptualization; Analysis; Manuscript Review.

EG: Manuscript Drafting and Review.

LE: Conceptualization; Manuscript Review.

TS: Conceptualization; Manuscript Review.

RL: Conceptualization; Manuscript Review.

LTM: Conceptualization; Analysis; Manuscript Review.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: LT Matthews: Operational support from Gilead Sciences for unrelated projects.

SV Hill: Support from Gilead Sciences for MedIQ.

L Elopre: Support from Merck Foundation for unrelated project.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, (grant number P30 AI027767).

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham's Institutional Review Board (Approval Number IRB-300004672). All participants verbally provided voluntary informed consent to participate in the study. Written consent was waived as all interviews were conducted remotely due to COVID-19 precautions.

Consent for Publication: Participants consented to allow their deidentified data be presented in a manuscript or other dissemination.

Data Availability: Participants did not provide consent for transcripts to be publicly available.

ORCID iD: Madeline C Pratt https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2255-0401

References

- 1.CDC. HIV in the United States and dependent areas. Accessed December 13, 2021.https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/ataglance.html

- 2.CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, 2017, 2018. 29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. HIV in the Southern United States. September 2019, 2019.

- 4.Alabama Department of Public Health Division of STI/HIV Prevention and Control (DoSHPaC). Brief Facts on African-Americans and HIV in Alabama. 2019. Accessed September 15, 2021. https://www.alabamapublichealth.gov/hiv/assets/brieffactsonafricanamericansandhiv.pdf

- 5.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, et al. HIV Protective efficacy and correlates of tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(3):340–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elopre L, Kudroff K, Westfall AO, Overton ET, Mugavero MJ. Brief report: the right people, right places, and right practices: disparities in PrEP access among African American men, women, and MSM in the deep south. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(1):56–59. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang YA, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N, Hoover KW. HIV Preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity - United States, 2014-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(41):1147–1150. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6741a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irie WC, Calabrese SK, Patel RR, Mayer KH, Geng EH, Marcus JL. Preferences for HIV preexposure prophylaxis products among black women in the U.S. AIDS Behav. 2022. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03571-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magnuson DHT, Mera R, editors. Adolescent use of Truvada (FTC/TDF) for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in the United States: (2012-2017). Presented at: International AIDS Conference, Amsterdam; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 Update: a clinical practice guideline. 2018.

- 11.Hill SV, Westfall AO, Coyne-Beasley T, Simpson T, Elopre L. Identifying missed opportunities for human immunodeficiency virus Pre-exposure prophylaxis during preventive care and reproductive visits in adolescents in the deep south. Sex Transm Dis. 2020;47(2):88–95. doi: 10.1097/olq.0000000000001104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Logie CH, Earnshaw V, Nyblade L, et al. A scoping review of the integration of empowerment-based perspectives in quantitative intersectional stigma research. Glob Public Health. 2021:1–16. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1934061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turan JM, Elafros MA, Logie CH, et al. Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pichon LC, Williams Powell T, Williams Stubbs A, et al. An exploration of U.S. Southern faith Leaders’ perspectives of HIV prevention, sexuality, and sexual health teachings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5734. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pryor JB, Gaddist B, Johnson-Arnold L. Stigma as a barrier to HIV-related activities among African-American Churches in South Carolina. J Prev Interv Community. 2015;43(3):223–234. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2014.973279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Code of Alabama. Title 16. Education; chapter 40A responsible sexual behavior and prevention of illegal drug use; section: 16-40A-2. In: Alabama State Code Section 16-40A-2, 16 AL Code § 16-40A-2 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atkins DN, Bradford WD. The effect of state-level sex education policies on youth sexual behaviors. Arch Sex Behav. 2021;50(6):2321–2333. doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01867-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox AM, Himmelstein G, Khalid H, Howell EA. Funding for abstinence-only education and adolescent pregnancy prevention: does state ideology affect outcomes? Am J Public Health. 2019;109(3):497–504. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2018.304896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alabama Senate Bill 184 (2022).

- 20.Madden EF. Intervention stigma: how medication-assisted treatment marginalizes patients and providers. Soc Sci Med. 2019;232:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearson J. High school context, heterosexual scripts, and young women’s sexual development. J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47(7):1469–1485. doi: 10.1007/s10964-018-0863-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parent MC, Moradi B. Self-objectification and condom use self-efficacy in women university students. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(4):971–981. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0384-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan PS, Mena L, Elopre L, Siegler AJ. Implementation strategies to increase PrEP uptake in the south. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16(4):259–269. doi: 10.1007/s11904-019-00447-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powers SD, Rogawski McQuade ET, Killelea A, Horn T, McManus KA. Worsening disparities in state-level uptake of human immunodeficiency virus preexposure prophylaxis, 2014-2018. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(7):ofab293. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegler AJ, Bratcher A, Weiss KM. Geographic access to preexposure prophylaxis clinics among men who have sex with men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(9):1216–1223. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ojikutu BO, Bogart LM, Higgins-Biddle M, et al. Facilitators and barriers to Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among black individuals in the United States: results from the National Survey on HIV in the Black Community (NSHBC). AIDS Behav. 2018;22(11):3576–3587. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2067-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bond KT, Gunn A, Williams P, Leonard NR. Using an intersectional framework to understand the challenges of adopting Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) among young adult black women. Sex Res Social Policy. 2022;19(1):180–193. doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00533-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ojikutu BO, Amutah-Onukagha N, Mahoney TF, et al. HIV-Related Mistrust (or HIV conspiracy theories) and willingness to use PrEP among black women in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(10):2927–2934. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02843-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen R, Bozzette S, Shapiro M, et al. Access of vulnerable groups to antiretroviral therapy among persons in care for HIV disease in the United States. HCSUS consortium. HIV cost and services utilization study. Health Serv Res. 2000;35(2):389–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting andersen’s behavioral model of health services use: a systematic review of studies from 1998-2011. Psychosoc Med. 2012;9:Doc11. doi: 10.3205/psm000089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anthony MN, Gardner L, Marks G, et al. Factors associated with use of HIV primary care among persons recently diagnosed with HIV: examination of variables from the behavioural model of health-care utilization. AIDS Care. 2007;19(2):195–202. doi: 10.1080/09540120600966182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, Katz MH, et al. The impact of competing subsistence needs and barriers on access to medical care for persons with human immunodeficiency virus receiving care in the United States. Med Care. 1999;37(12):1270–1281. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivet Amico K. A situated-information motivation behavioral skills model of care initiation and maintenance (sIMB-CIM): an IMB model based approach to understanding and intervening in engagement in care for chronic medical conditions. J Health Psychol. 2011;16(7):1071–1081. doi: 10.1177/1359105311398727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santelli JS, Kantor LM, Grilo SA, et al. Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage: an updated review of U.S. Policies and programs and their impact. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(3):273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenthal L, Lobel M. Stereotypes of black American women related to sexuality and motherhood. Psychol Women Q. 2016;40(3):414–427. doi: 10.1177/0361684315627459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lloyd SW, Ferguson YO, Corbie-Smith G, et al. The role of public schools in HIV prevention: perspectives from African Americans in the rural south. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(1):41–53. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.1.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldfarb E, Lieberman L, Kwiatkowski S, Santos P. Silence and censure: a qualitative analysis of young Adults’ reflections on communication with parents prior to first sex. J Fam Issues. 2018;39(1):28–54. doi: 10.1177/0192513X15593576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tangel V, White RS, Nachamie AS, Pick JS. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal outcomes and the disadvantage of peripartum black women: a multistate analysis, 2007-2014. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(8):835–848. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1675207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moaddab A, Dildy GA, Brown HL, et al. Health care disparity and pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2005-2014. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(4):707–712. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000002534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill SV, Pratt M, Elopre L, et al. Barriers to PrEP use among young African American girls and young women in Alabama: provider perspectives. 2021.

- 43.Chandler R, Hull S, Ross H, et al. The pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) consciousness of black college women and the perceived hesitancy of public health institutions to curtail HIV in black women. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1172. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09248-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, Charles V. Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(2):102–110. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okeke NL, McLaurin T, Gilliam-Phillips R, et al. Awareness and acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among students at two historically Black universities (HBCU): a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):943. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10996-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rao D, Andrasik MP, Lipira L. HIV Stigma among Black women in the United States: intersectionality, support, resilience. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):446–448. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 Update: a clinical practice guideline. 2021.