Abstract

Introduction

Repositioning practice is an essential pressure ulcer prevention intervention that has emerged in the history of nursing. Numerous terms are employed to indicate its meaning, such as turning, positioning, or posturing. However, there is no available analysis that distinguishes these terms or analyzes repositioning practice attributes.

Objective

To analyze repositioning practice as a concept of bedridden patients in hospitals by combining methods from Foucault's archeology of knowledge and Rodger's concept analysis.

Concept Description

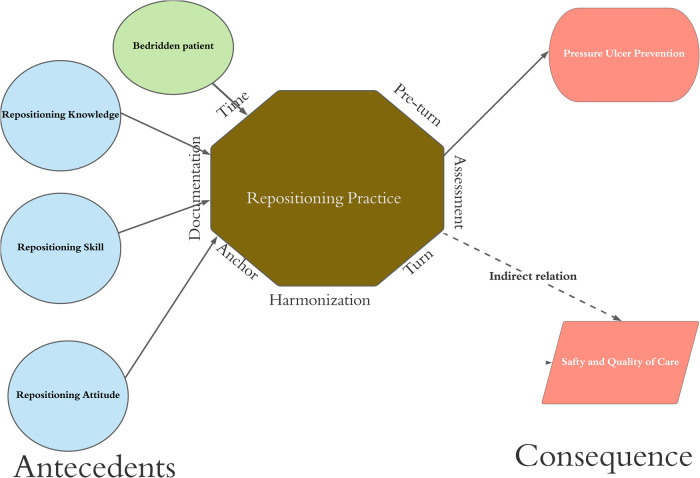

Repositioning practice passes through three eras: classical, modern, and research. The repositioning practice is “turn a bedridden patient in a harmonized way and ends with anchor and documentation.” The analysis concludes seven attributes for the repositioning practice: pre-turn, assessment, turn, harmonization, anchor, documentation, and time. The analysis assumes bedridden patients, and assigned nurses on duty are the antecedents. Moreover, the main consequence is pressure ulcer prevention, while patient safety and quality of care are the secondary consequences.

Discussion

Repositioning practice understanding has grown with time. Each era has added to or removed from nursing's understanding for repositioning practice until it appears as it now. The current analysis expects further development in repositioning practice understanding and applications.

Conclusion

Repositioning practice is an important nursing intervention and has shown a dynamic movement over history. It is expected that this dynamic will continue in the future.

Keywords: bedridden, patient safety, pressure ulcer, quality of health care

Introduction

A pressure injury, pressure ulcer, or pressure sore refers to cellular death due to pressure and shear (Gefen, 2018). Experts have suggested a skin assessment (Kim et al., 2018), repositioning practice, offloading mattresses, nutritional support, and skincare (EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019) to prevent it. Even though evidence shows positive consequences from these measures in prevention (Gunningberg et al., 2017; Renganathan et al., 2018; Sving et al., 2014; Webster et al., 2017), repositioning practice has faced challenges related to its definition.

Nurses have been practicing repositioning for more than 200 years. Nevertheless, the evidence shows disagreements in defining repositioning either based on frequency (Jocelyn Chew et al., 2018), quality (Gunningberg et al., 2017), techniques (Weiner et al., 2017), or even the used term (Jocelyn Chew et al., 2018). However, it is used in combination with the term “turn,” such as “repositioning and turning” (Kozier et al., 2018) or “turning and repositioning” (White, 2011).

Nurses are receiving contradictory information about the repositioning practice. It starts from time (either every two, three, or based on the patient's condition) and passes through all attributes, which negatively impact the compliance. For instance, reports indicate that only 40% of patients needing repositioning are treated appropriately (Schutt et al., 2018). Furthermore, in India, a study found that 70% of patients did not get the required level of repositioning practice (Renganathan et al., 2018). Similar results have been obtained in Belgium (Beeckman et al., 2011), Sweden (Källman et al., 2016), Egypt (Ali et al., 2018), China (Feng et al., 2016), Australia (Chaboyer et al., 2016), Hong Kong (Kwong et al., 2016), and the Netherlands (Meesterberends et al., 2013). No one can compare these results or evaluate the improvement strategies among those studies without standardizing the intended meaning. Therefore, repositioning is a cornerstone in the ulcer prevention (Gefen, 2018) and crucial to the patient safety (Duncan, 2007). Standardizing the concept is a beneficial aspect to nursing science.

Objectives

The current paper applied a hybrid analysis approach that utilizes the archeology of knowledge exploration (Gutting, 1989) and Rodger's evaluation concept analysis (Tofthagen & Fagerstrøm, 2010) to clarify the contemporary meaning of repositioning. Moreover, the current paper presents the repositioning as performed by nurses for pressure ulcer prevention. Even though it might be performed by others or for different reasons such as grooming or feeding, the main concern is done by nurses or under nurses’ supervision for pressure redistribution to achieve ulcer prevention (White, 2011). Therefore, the aim is to analyze repositioning in the nursing context.

Literature Review

A literature search was conducted using the PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, and Google Scholar databases, together with the E-library database of Chulalongkorn University. Moreover, there was a shelf search of the nursing textbooks available in the library of Chulalongkorn University. The terms “repositioning,” “positioning,” “turning,” and “move out” were searched for in the keywords and titles of articles. Searchers were performed in April 2021, and two independent investigators conducted the article selections based on presenting the following inclusion criteria: (a) definitions and attributes of repositioning, (b) antecedents, consequences, and empirical evidence of repositioning, and (c) published in English. The exclusion criteria were: (a) letters to the editors, (b) non-peer-reviewed articles, (c) commentaries, (d) discussing the repositioning out of pressure ulcer prevention context, and (e) discussing the repositioning performed by non-nursing personnel or for other than pressure ulcer prevention purpose. Fifty-six out of 176 potential references were selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All of the authors performed the screening. First, the researchers checked for duplicate references and studies conducted on a different topic. Then, the title was screened for its inclusion of at least one of the search terms (“repositioning” or “positioning” or “turning” or “move out” and “patients”). Finally, references were screened against the exclusion criteria. The references that were not written in English were also excluded.

A total of 53 literatures were analyzed and divided become three groups, which included classical era (Basil, 1888; Bradford, 2016; Domville, 1881; Elliot, 1896; Nightingale, 1860; Rogers, 1849; Sanders, 1916; Scanlan, 1886), modern (Bardsley et al., 1964; Bliss et al., 1967; Burston et al., 1950; Carpendale, 1974; Cope, 1939; Exton-Smith, 1961; Matheson & Lipschitz, 1956; Newell Jr et al., 1970; Silver, 1967; Souther et al., 1973), and research (Beeckman et al., 2013; Berman et al., 2010; Bours et al., 2002; Carpenito, 2013; DeWit & Williams, 2013; Diepenbrock, 2011; Eckman & Aldinger, 2013; EPUAP, 2009; EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA., 2019; Hall & Clark, 2016; Jocelyn Chew et al., 2018; Kozier et al., 2018; Langemo et al., 2015; Lewis et al., 2016; Lynn, 2010; Lynn, 2018; Manderlier et al., 2017; Miles et al., 2013; Mogotlan, 2015; Moore & Cowman, 2015; Moore et al., 2011; Morton et al., 2017; NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPI, 2014; O’Neil, 2004; Potter et al., 2013; Rhoads & Meeker, 2008; Saliba et al., 2003; Samuriwo & Dowding, 2014; Soban et al., 2011; Springhouse, 2006; Tayyib & Coyer, 2017; Tayyib et al., 2016; Treas & Wilkinson, 2012, 2013; White, 2011; Wilkinson & Van Leuven, 2016; Yarkony, 1994).

Authors agreed to point out these epistemological events as follows; the year 1930 is the transition between the classical to modern era. That was due to shifting the nature of ulcer development understanding, as characterized by shifting the used expression from bedsore to be pressure sore. Therefore, the classical era ended in 1929. The modern era started in 1930 and ended by inventing the first classification system for pressure ulcers in 1974 (Shea, 1975). The classification still influences the modern classifications until nowadays. That classification opens the gate for massive studies in the field of pressure ulcer prevention (including repositioning). At that time, a panel of experts (EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019) proposed improvements for pressure ulcer understanding (Kottner et al., 2020), which influenced changes in the understanding of the nature of repositioning (Foucault, 2002). Authors assume that this period ended in 2020 due to proposed changes in repositioning techniques based on the presence of the last pandemic (Moore et al., 2020).

Concept Description and Model

Literature that compound these words are textbooks used in teaching and hold in the title “fundamental of nursing” (Burton & Ludwig, 2014; DeWit & Williams, 2013; Kozier et al., 2018; Nugent & Vitale, 2014; Potter et al., 2013; Suresh, 2017; Wilkinson & Van Leuven, 2016; Wilkinson, 2016; Yoost & Crawford, 2019) or “foundation of nursing” (Cooper & Gosnell, 2014; White, 2011). Therefore, passing these terms from writing and several revisional rounds reveals that the ambiguity of defining repositioning (or mixing it with turning) might be a stream in nursing science. Nevertheless, it appears as moving, positioning, and changing patient posture to refer to the same meaning (Kozier et al., 2018).

Repositioning practice specifies the behavior of repositioning. Therefore, instead of using repositioning expression, which might refer to the frequency (Jocelyn Chew et al., 2018) of turn or duration between each performance (Hanna et al., 2016), authors agreed that repositioning practice specifies the actual performance (Avsar et al., 2019).

The analysis divided the historical period based on the changes in the preconceptual level. The preconceptual level was attribution, articulation, designation, and derivation of the context (where the concept belongs). Foucault believed that the changes in the preconceptual level depend on how people understand particle expression or deal with it. Understanding a concept is influenced by how people preserve it (Foucault, 2002).

Classical Era Until 1929

Florence Nightingale adopted “moved about” (Nightingale, 1860) to refer to repositioning practice. While others utilized other terms such as; changed position, turn, moving, and turning (Scanlan, 1886) which shows disagreements on the terms for descripting the intervention. Conceptualizing the content meaning shows that a patient who is unable to move will have bedsores in the forms of successions. Therefore, nurses have to do the intervention “move out” (Nightingale, 1860). If the nurse fails to do the “move out,” the patients will have pressure ulcer “bedsore” (Nightingale, 1860). For the nature of relation “Type of dependences,” bedsore depends on the nursing care (Scanlan, 1886). Therefore, the meaning contains the turn as physical action from nurses. The combination of repositioning practice depends on nursing efforts to prevent ulcer formation.

The second aspect of archeology is in the form of the “enunciative” (Foucault, 2002). Repositioning practice at that time appeared limited and depended on personal input. Also, there are no available discussions about doing “procedure of intervention.” As well there was a strong “dogmatic” belief in its importance with no reasons why that was necessary (Scanlan, 1886) accompanied by a weak scientific rationalization on when and how it should happen (Scanlan, 1886).

Modern Era (1930–1974)

The aim of repositioning practice was exposing the skin to light, which (the light) would prevent pressure ulcers (Grossman & Lightfoot, 1945). The analysis explicates that repositioning practice intends to be a practice (Bliss et al., 1967). It appeared as a teamwork intervention, not an individual task (Carpendale, 1974; Exton-Smith, 1961). Also, the frequency of turn was within two hours, which appears quite obvious (Silver, 1967) with scientific rationalizations (Bardsley et al., 1964; Exton-Smith, 1961; Matheson & Lipschitz, 1956). Also, documentation is appressed as an essential element (Silver, 1967).

Literature mentioned the need to offload the pressure by pads, mattresses, or other devices (Bliss et al., 1967), which implicitly proposes reducing the repositioning practice frequency every two hours. Also, the literature did not describe the techniques for fixing the patient's posture “after the turn.” Trumble (1930) described all aspects of repositioning practice except the fixation. Finally, literature eliminates expressions that blame nurses for pressure ulcer development, which means a transfer in the field of memory “disappears.”

Research Era (1975–2020)

In 1975, pressure ulcers were classified based on the anatomical aspect (Shea, 1975). Later, the risk assessment tools (Braden et al., 1987) generated revolutionary thoughts in pressure ulcer prevention. Then, the advisory panels were founded which transferred the concern to the global level (Moore, 1988). All those changes remodified pressure ulcer prevention and, as a result, impacted repositioning practice. Those reformations were characterized by clinical, academic, and organizational significant changes in pressure ulcer prevention. The endpoint was chosen as 2020, where the coronavirus disease 2019 (Tripathi et al., 2020) impacted pressure ulcer prevention, which includes the repositioning practice (Moore et al., 2020). Until the time of analysis, this consequence is not precise yet.

The analysis noticed the presence of colored pictures combined with written texts (Burton & Ludwig, 2014; Kozier et al., 2018; Nugent & Vitale, 2014; Potter et al., 2013; Wilkinson & Van Leuven, 2016; Yoost & Crawford, 2019). That denotes that the words cannot explain the repositioning practice alone and so the photos were required (Moore et al., 2015). References also focus on nurses’ compliance (Bergstrom et al., 2013; Cyriacks & Spencer, 2019; Jocelyn Chew et al., 2018), quality (Schutt et al., 2018), and its consequences (Moore et al., 2015).

On the other hand, literature had not shared a similar “field of memory,” for the time. For instance, international guidelines proposed an individualized plan for repeating the intervention “repositioning practice” (EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA., 2019). That meant there was no definite cut off point to determine the time between each repositioning practice, while others declared a specific predetermined point of time for the repositioning practice either every two hours (Kozier et al., 2018) or more (Bergstrom et al., 2013; Dancy et al., 2010; Fragala & Fragala, 2014; Jocelyn Chew et al., 2018; Ostadabbas et al., 2011; Pickham et al., 2016; Vanderwee et al., 2007). As for the quality of pressure distribution, international guidelines present the highest focus on its need, which had almost disappeared from nursing textbooks.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram.

Attributes

The analysis applied summative content analysis for the references from the last research era to explore the attributes, assuming that the knowledge accumulated appears in the work of literature at that particular point. The analysis showed that 577 different locations highlight a repositioning practice component. These points are categorized for 72 codes to generate seven defining attributes as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summative Content Analysis for Repositioning Practice Attributes.

| Attribute | Code | Frequency | % in the attributes | % in the overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-turn = 15 codes | Identify patient | 4 | 4.49% | 0.69% |

| Introduce nurse | 3 | 3.37% | 0.52% | |

| Explain the procedure | 5 | 5.62% | 0.87% | |

| Prepare the bed | 17 | 19.10% | 2.95% | |

| Adjust the arm | 7 | 7.87% | 1.21% | |

| Place draw sheet | 8 | 8.99% | 1.39% | |

| Securing patients’ buttocks | 1 | 1.12% | 0.17% | |

| Adjusting patients’ knees | 6 | 6.74% | 1.04% | |

| Adjusting patient's legs | 1 | 1.12% | 0.17% | |

| Remove the pillows | 10 | 11.24% | 1.73% | |

| Side raise | 7 | 7.87% | 1.21% | |

| Guaranteeing patients privacy | 7 | 7.87% | 1.21% | |

| Appropriate starting posture | 5 | 5.62% | 0.87% | |

| Prone position consideration | 6 | 6.74% | 1.04% | |

| Hand wash | 2 | 2.25% | 0.35% | |

| Total of pre-turn locations | 89 | 100.00% | 15.42% | |

| Assessment = 4 codes | Ability to assist | 7 | 17.07% | 1.21% |

| Pressure ulcer risk | 8 | 19.51% | 1.39% | |

| Turn restriction | 11 | 26.83% | 1.91% | |

| Skin | 15 | 36.59% | 2.60% | |

| Total of assessment locations | 41 | 100.00% | 7.11% | |

| Turn = 12 codes | Hand on shoulder hand on hip | 14 | 15.73% | 2.43% |

| Hold head and neck | 7 | 7.87% | 1.21% | |

| Move the arm | 5 | 5.62% | 0.87% | |

| One hand under the patient | 2 | 2.25% | 0.35% | |

| Move the leg | 3 | 3.37% | 0.52% | |

| Move the knees | 4 | 4.49% | 0.69% | |

| Monitoring patient condition | 2 | 2.25% | 0.35% | |

| Lift by sheet or device | 28 | 31.46% | 4.85% | |

| Rolling | 21 | 23.60% | 3.64% | |

| Pressure mapping | 1 | 1.12% | 0.17% | |

| Range of motion | 1 | 1.12% | 0.17% | |

| Heels | 1 | 1.12% | 0.17% | |

| Total of turns | 89 | 100.00% | 15.42% | |

| Harmonization = 4 codes | Two to three staff | 23 | 36.51% | 3.99% |

| Count to three | 10 | 15.87% | 1.73% | |

| Body mechanism proper use | 20 | 31.75% | 3.47% | |

| One at each side of bed | 10 | 15.87% | 1.73% | |

| Total | 63 | 100.00% | 10.92% | |

| Anchor = 13 codes | Assure comfort | 16 | 13.68% | 2.77% |

| Head and shoulder | 14 | 11.97% | 2.43% | |

| Support the leg | 8 | 6.84% | 1.39% | |

| Support the back | 12 | 10.26% | 2.08% | |

| Heel | 14 | 11.97% | 2.43% | |

| Feet | 4 | 3.42% | 0.69% | |

| Knees | 6 | 5.13% | 1.04% | |

| Hand and forearm | 3 | 2.56% | 0.52% | |

| Wait to be sure | 2 | 1.71% | 0.35% | |

| Patient bed angel | 16 | 13.68% | 2.77% | |

| Secure the device | 14 | 11.97% | 2.43% | |

| Eliminate sheet effect | 2 | 1.71% | 0.35% | |

| Boney prominence | 6 | 5.13% | 1.04% | |

| Total | 117 | 100.00% | 20.28% | |

| Documentation = 13 cods | How that happen | 3 | 4.92% | 0.52% |

| Skin condition | 15 | 24.59% | 2.60% | |

| What is the current position | 7 | 11.48% | 1.21% | |

| When that happen | 17 | 27.87% | 2.95% | |

| Describe the body condition | 2 | 3.28% | 0.35% | |

| Who participate in doing? | 3 | 4.92% | 0.52% | |

| Presence of pain or discomfort | 3 | 4.92% | 0.52% | |

| Document unusual findings | 1 | 1.64% | 0.17% | |

| Based on policy | 1 | 1.64% | 0.17% | |

| Level of cooperation | 2 | 3.28% | 0.35% | |

| Equipment used | 3 | 4.92% | 0.52% | |

| Record physician notification | 1 | 1.64% | 0.17% | |

| Reminders | 2 | 3.28% | 0.35% | |

| Factors influencing the decision | 1 | 1.64% | 0.17% | |

| Total | 61 | 100.00% | 10.57% | |

| Time = 10 codes | Within 30 min | 4 | 3.40% | 0.69% |

| Within 1 h. | 2 | 1.70% | 0.35% | |

| Every 1 to 2 h. | 5 | 4.30% | 0.87% | |

| Every 2 h. | 33 | 28.20% | 5.72% | |

| Within 3 | 7 | 6.00% | 1.21% | |

| Within 2 to 4 h. | 8 | 6.80% | 1.39% | |

| Every 4 h. | 3 | 2.60% | 0.52% | |

| Frequent (no specification) | 36 | 30.80% | 6.24% | |

| Based on individualized plan | 17 | 14.50% | 2.95% | |

| Reminders | 2 | 1.70% | 0.35% | |

| Total | 117 | 100.00% | 20.28% | |

| Total of codes = 72 | All score | 577 | 100% |

Pre-turn. Pre-turn is what nurses do before starting the turn to make the patients ready (Lynn, 2010). Statements or text that refers to pre-turn features appear in 89 locations to consist of 15.7% of the total frequencies. (The detailed information can be seen in Supplementary File Table S1). Authors formulated these texts to 15 codes: identifying the patients, introducing the nurse, explaining the procedure, preparing the patient's bed, adjusting the arm, placing sheet, securing the patient's buttocks, adjusting the patient's knees, removing the pillows, elevating side rail, guaranteeing patient's privacy, the appropriate starting position, special considerations for the prone position, securing the patient's leg, and handwashing.

Patient Assessment. Assessing the patient is a primary step in nursing care (Doenges et al., 2019), including repositioning practice. Assess the patients’ general condition appears in 41 locations to formulate 7.11% of the total over four codes: assess patient ability, assess pressure ulcer risk, revise the turn restrictions, and skin assessment (the detailed information can be seen in Supplementary File Table S2).

Turn. Turn is the brightest attribute, and it reflects the procedure to hold the patient and change his posture. It appears in many places in combination with repositioning (Lynn, 2010). Turn appeared in 89 locations to formulate 15.5% of the total. The authors categorized these points over twelve codes: hand on the shoulder, hand on hip, hold head and neck, move the arm, one hand under the patient, move the leg, move the knees, monitoring the patients’ conditions during the turn, lift by sheet or device, rolling the patients, pressure mapping, check the range of motions, and move the heels (the detailed information can be seen in Supplementary File Table S3).

Harmonization. Harmonization refers to the proper coordination between nurses during the action of turn (Berman et al., 2010; Burton & Ludwig, 2014; DeWit & Williams, 2013; Kozier et al., 2018; Nugent & Vitale, 2014; Potter et al., 2013; Wilkinson & Van Leuven, 2016; Wilkinson, 2016). Texts and pictures impersonate the harmonization as vital attributes. Although the term harmonization was not applied among the revised references, the authors preferred it to describe the current thematic meaning. Sixty-three locations mentioned the meaning of harmonization. Authors categorized them into four codes: two to three staff participate in the move, count to three, proper use of body mechanism, and one nurse at each side of the bed. The frequencies equal 10.8% of the total (the detailed information can be seen in Supplementary File Table S4).

Anchor. An anchor is a heavy metal piece used by ships to assure stability over the sea (King, 2019). Although the anchor is not a famous description for fixing patients on specific posture, authors assumed it displays the intended meanings. Therefore, the anchor is fixing the patient on a specific posture. It allows the revascularization of body organs, which were under pressure (Schwartz & Gefen, 2019). The literature mentioned anchor meaning in 116 different location. The analysis categorized them over 13 codes: assure the comfort, support the head, shoulder, and arms (one code), support the leg, support the back, support the heel, support the feet, support the knees, support the forearm, wait to be sure, revise the angle between patient and the bed, secure devices, eliminate the sheeting effect, and secure the boney prominences. The percentages of those codes are equal to 20.28% (the detailed information can be seen in the Supplementary File Table S5).

Documentation. Documentation is what nurses do to inform about the actualization of repositioning practice (Collier, 2016). Several studies rely on what nurses document as evidence of actualization (Jocelyn Chew et al., 2018). Documentation related issues appear for 60 locations among the revised texts to formulate 13 codes: how that happened, skin condition, current posture, describe the body condition, who participated, clarifying any pain or discomfort, policy-based, level of patient's cooperation, equipment used, record physician notification, reminders, and factors influencing the decision. The percentages of those codes equal to 10.57% (the detailed information can be seen in Supplementary File Table S6).

Time. Repositioning practice is a time-dependent intervention (Moore, 2010; Moore et al., 2020; Moore & Van Etten, 2014). Nevertheless, there is disagreement in the proper time. Literature from the modern era presents exact time points, starting from 30 min (Burston et al., 1950) to 2 h (Bardsley et al., 1964; Bliss et al., 1967; Newton, 1938). The 2-h recommendations kept appearing in the research era (Baillie, 2011; Baillie et al., 2014; Bergstrom et al., 2013; Carpenito, 2013; Herman & Rothman, 1989). However, others suggested different time points (De Meyer et al., 2019; Fragala & Fragala, 2014; Moore et al., 2013; Palfreyman & Stone, 2014; Peterson et al., 2013).

Issues related to time appear in 117 different locations. Those were categorized over ten codes as follows: within 30 min, within one hour, every one to two hours, every two hours 33 times, within 2 to 4 h eight-times, every 4 h, based on individualized plans, and two locations mentioned based on time reminding, and there were 36 locations, which mentioned the time with no specifications for the duration. The frequency of all these points equals 20.28% (the detailed information can be seen in Supplementary File Table S7).

Antecedents

Antecedents are the pre-request issues to actualize the construct “Repositioning practice.” From the literature, it appears that repositioning practice required having a patient at risk for pressure ulcer development (White, 2011). Also, it required someone to perform the procedure (Jocelyn Chew et al., 2018). As the analysis focused only on cases that nurses performed and excluded the literature arguing about others, competent nurses are assigned to deliver the care for that patient who exists physically near the nurse. Furthermore, satisfying the harmonization required secondary nurse(s) that help in the performance. Absence of these preconditions might not satisfy the intended meaning of the repositioning practice as presented above. Figure 1 shows the antecedents’ relations with the central construct.

Consequences

The consequence of the repositioning practice is evident. If the repositioning is performed, it will directly enhance pressure ulcer prevention. Also, it will impact the quality of care (Duncan, 2007), patient satisfaction (Kalisch et al., 2014), and patient safety (Kalisch et al., 2011), as it appears in Figure 1.

Model case

Ms. X is a nurse in the ward. She is assigned to a bedridden patient. Ms. X realizes that the patient is unable to turn or move. At 08:00, Ms. X planned the turning procedure for the patients every two hours. Ms. X performed the turning with the help of her colleagues. Ms. X rolled the patients according to the protocols and followed the steps one by one to change the posture. Ms. X anchored the patient to the new position. After that, Ms. X documented the procedure done. She recorded the help by other nurses’ initials. Also, Ms. X documented the coming time and suggested the new posture. This procedure was repeated by the same techniques for all days, and the patient did not develop any pressure ulcers.

Discussion

The current paper aims to analyze the repositioning practice as concept of bedridden patients during hospitalizations. The current analysis displays the defragmentation of the terms, descriptions, and included attributes. The current analysis shows the importance of turn as the main component, but turn alone did not satisfy the purpose of the interventions in assuring the offloading. Therefore, using the term “turn” would not refer to the repositioning practice. Moreover, the data taken from nurses’ notes would be limited in reflecting the repositioning compliance, as it did not tell the evaluators about presenting other attributes rather than the documentation. Thus, it highlights the need for a suitable measurement approach for measuring performance.

The impact of repositioning practice is understood by its absence. Several studies express the impact of long-standing pressure on the tissues, leading to pressure ulcer development (Gefen, 2009), so lacking repositioning practice increases the chance of pressure ulcer development. Therefore, the realization of repositioning practice leads to the absence of pressure ulcers (or at least minimizes its chance) (Chaboyer et al., 2016). That minimization for pressure ulcer development impacts the patient, health organizations, and quality of care in general.

Pre-turn is the preparation of the nurse and the patient. It is the time between deciding to reposition and making the turn. Second, repositioning practice required nurses to assess patients that included assessing the patient's capacity to assist during the turn, assessing pressure ulcer risk areas, assessing turn restriction, and assessing skin condition. Third, change the patient's posture by holding and turning him/her or repositioning (Lynn, 2010). Four, harmonization is needed when a repositioning practice is done if it takes more than one person to achieve. In some conditions, anchor is used to help facilitate the pressure distribution (Gefen, 2009) and revascularization of the pressed organs (Schwartz & Gefen, 2019).

Nurses have to record their actions. The documentation would help the nurse to evaluate their performance. It will become worse or better in a matter of time. The last and the most crucial factor is time. Time for giving repositioning practice is a conflicting issue in the literature. It could be 30 min or more than six hours. The current analysis clarifies the structure of repositioning practice that might be used in education, training, measurements, or improvement projects. In assuring the proper descriptions for the repositioning practice, applicable sharing of the study result will have much potential.

Implications for Practice

The current study impacts the state of nursing science over three levels: nursing administration, nursing education, and nursing research. First, nursing leaders are responsible for ensuring nurses’ compliance in repositioning practice for immobilized patients. Leaders applied several projects and approaches to enhance nurses’ performance, but the lack of unified description for the concept limits their abilities for improvements.

In addition, repositioning practice concept analysis clarifies the critical boundaries between repositioning practice and related concepts, such as turn. These clarifications enhance the description for the nursing students. Last but not least, the current analysis unified the description for the repositioning practice. Experts will generate comparative studies and evaluate the consequence of the any related interventions focused on improving the repositioning practice by unified the terms and agreed on its meaning.

Limitations

The current analysis had three limitations: the nature of included literature (input concern), the nature of changes in the future, and the nature of the analyzer. Firstly, the current analysis included studies that varied from textbooks, studies, and editorial articles. These manuscripts differ in their nature and the methods of describing the concept. Even with the authors’ efforts to systematically analyze these articles but lacking a standardized methodical evaluation for the grade of reference interrupted the quality of analysis. Secondly, the concept changes according to time. Therefore, the concept is sensitive to further changes in the future based on the advances in the technology or development in information technology. The analysis failed to predict these suspected changes and the nature of their influence. Finally, the analysis depends on the authors’ subjective understanding of the nature of the concept based on their background, which might differ if authors with different backgrounds reconduct the analysis.

Conclusion

Repositioning practice is a challenging concern in pressure ulcer domains. Even though the term looks straightforward, it needs further clarification. The analysis adopted archeology of knowledge with Rodger concept analysis to conclude that the term passes through three eras (classical, modern, and research). Each of these eras adds or removes for the repositioning practice until it is defined as turning for bedridden patients that contains harmonization, anchor, documentation, and a time-dependent intervention.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-son-10.1177_23779608221106443 for Repositioning Practice of Bedridden Patients: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis by Abdulkareem S. Iblasi, Yupin Aungsuroch, Joko Gunawan, I. Gede Juanamasta and Cheryl Carver in SAGE Open Nursing

Acknowledgments

This concept analysis is a part of dissertation entitled “Scale development of nursing repositioning practice for bedridden patients, Saudi Arabia.”

Footnotes

Ethical Statement: We declare that an ethical statement is not applicable as this manuscript does not involve human or animal research.

Author Contribution: Abdulkareem S. Iblasi (ASI), Yupin Aungsuroch (YA), Joko Gunawan (JG), I. Gede Juanamasta (IGJ), and Cheryl Carver (CC) made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or the analysis and interpretation of data. ASI, YA, JG, IGJ, and CC involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. ASI, YA, JG, IGJ, and CC gave final approval of the version to be published. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Abdulkareem S. Iblasi https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3360-1462

Joko Gunawan https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6694-8679

I. Gede Juanamasta https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5445-7861

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Ali K. A. G., Helal W. E. S. H., Salem F. A., Attia H. (2018). Applying interdisciplinary team approach for pressure ulcer assessment, prevention and management. International Journal of Novel Research in Healthcare and Nursing, 5(3), 640–658. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331715726 [Google Scholar]

- Arkony G. M. (1994). Pressure ulcers: A review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 75(8), 908–917. 10.1016/0003-9993(94)90117-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avsar P., Patton D., O'Connor T., Moore Z. (2019). Do we still need to assess nurses’ attitudes towards pressure ulcer prevention? A systematic review. Journal of Wound Care, 28(12), 795–806. 10.12968/jowc.2019.28.12.795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillie L. (2011). Developing practical adult nursing skills third edition. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baillie L., Ozenbaugh R. L., Pullen T. M. (2014). Developing practical nursing skills. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bardsley C., Fowler H., Moody E., Teigen E., Sommer J. (1964). Pressure sores: A regimen for preventing and treating them. The American Journal of Nursing, 64(5), 82–84. 10.2307/3419146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basil M. (1888). Aids to nursing. The Hospital, 3(74), 363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeckman D., Clays E., Van Hecke A., Vanderwee K., Schoonhoven L., Verhaeghe S. (2013). A multi-faceted tailored strategy to implement an electronic clinical decision support system for pressure ulcer prevention in nursing homes: A two-armed randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(4), 475–486. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeckman D., Defloor T., Schoonhoven L., Vanderwee K. (2011). Knowledge and attitudes of nurses on pressure ulcer prevention: A cross-sectional multicenter study in Belgian hospitals. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 8(3), 166–176. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom N., Horn S. D., Rapp M. P., Stern A., Barrett R., Watkiss M. (2013). Turning for Ulcer ReductioN: A multisite randomized clinical trial in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(10), 1705–1713. 10.1111/jgs.12440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman, A., Snyder, S. J., Kozier, B., Erb, G., Levett-Jones, T., Dwyer, T., Hales, M., Harvey, N., Luxford, Y., Moxham, L., & Park, T., . . . Moxham L. (2010). Kozier and Erb’s fundamentals of nursing (Vol. 1). Pearson Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss M. R., McLaren R., Exton-Smith A. (1967). Preventing pressure sores in hospital: Controlled trial of a large-celled ripple mattress. British Medical Journal, 1(5537), 394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bours G. J., Halfens R. J., Abu-Saad H. H., Grol R. T. (2002). Prevalence, prevention, and treatment of pressure ulcers: Descriptive study in 89 institutions in the Netherlands. Research in Nursing & Health, 25(2), 99–110. 10.1002/nur.10025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braden B. J., Bergstrom N., Demuth P. (1987). A clinical trial of the Braden scale for predicting pressure sore risk. The Nursing Clinics of North America, 22, 417–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford N. K. (2016). Repositioning for pressure ulcer prevention in adults—A Cochrane review. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 22(1), 108–109. 10.1111/ijn.12426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burston I., Austin E., Leonard Huddleston O., Bower A. G. (1950). Treatment of bedsores in respirator patients. Physical Therapy, 30(7), 272–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton M. A., Ludwig L. J. M. (2014). Fundamentals of nursing care: Concepts, connections & skills. FA Davis. [Google Scholar]

- Carpendale M. (1974). A comparison of four beds in the prevention of tissue ischaemia in paraplegic patients. Spinal Cord, 12(1), 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenito L. J. (2013). Handbook of nursing diagnosis (14 ed.). Wolters Kluwer / Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Chaboyer, W., Bucknall, T., Webster, J., McInnes, E., Gillespie, B. M., Banks, M., Whitty, J. A., Thalib, L., Roberts, S., & Tallott, M. (2016). The effect of a patient centred care bundle intervention on pressure ulcer incidence (INTACT): A cluster randomised trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 64, 63–71. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier M. (2016). Pressure ulcer prevention: Fundamentals for best practice. Acta Medica Croatica, 70(Suplement 1), 3–10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29087640 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope V. Z. (1939). Prevention and treatment of bed-sores. British medical journal, 1(4083), 737–738. 10.1136/bmj.1.4083.737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper K., Gosnell K. (2014). Foundations of nursing-E-book. Elsevier Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Cyriacks B., Spencer C. (2019). Reducing HAPI by cultivating team ownership of prevention with budget-neutral turn teams. Medsurg Nursing, 28(1), 48–52. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&site=eds-live&db=a49h&AN=134771003&custid=s136224580 [Google Scholar]

- Dancy G., Kim H., Wiebelhaus-Brahm E. (2010). The turn to truth: Trends in truth commission experimentation. Journal of Human Rights, 9(1), 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- De Meyer D., Van Hecke A., Verhaeghe S., Beeckman D. (2019). PROTECT–Trial: A cluster RCT to study the effectiveness of a repositioning aid and tailored repositioning to increase repositioning compliance. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(5), 1085–1098. 10.1111/jan.13932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWit S. C., Williams P. A. (2013). Fundamental concepts and skills for nursing. Elsevier Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Diepenbrock N. H. (2011). Quick reference to critical care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Doenges M., Moorhouse M. F., Murr A. (2019). Nursing care plans: Guidelines for individualizing client care across the life span (10th ed.). FA Davis. [Google Scholar]

- Domville E. J. (1881). A manual for hospital nurses.

- Duncan K. D. (2007). Preventing pressure ulcers: The goal is zero. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 33(10), 605–610. 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33069-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckman M., Aldinger Megan L., K K. J., & Jeri O’Shea Linda K. Ruhf. (2013). Lippincott manual of nursing procedures. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot G. S. (1896). The nursing of imbeciles under the asylums board. British Medical Journal, 2(1871), 1414. [Google Scholar]

- EPUAP, N. (2009). International guideline treatment of pressure ulcers: Quick reference guide. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. [Google Scholar]

- EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA (2019). Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/ injuries: Clinical practice guideline. The international guideline. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- Exton-Smith A. (1961). The prevention of pressure sores. Gerontologia Clinica, 3(2), 65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H., Li G., Xu C., Ju C. (2016). Educational campaign to increase knowledge of pressure ulcers. British Journal of Nursing, 25(12), S30–S35. 10.12968/bjon.2016.25.12.s30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. (2002). Archaeology of knowledge.

- Fragala G., Fragala M. (2014). Improving the safety of patient turning and repositioning tasks for caregivers. Workplace Health & Safety, 62(7), 268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gefen A. (2009). Reswick and Rogers pressure-time curve for pressure ulcer risk. Part 1. Nursing Standard (Through 2013), 23(45), 64. 10.7748/ns2009.07.23.45.64.c7115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M. O., Lightfoot L. H. (1945). A treatment for bed sores. The American Journal of Nursing, 45(2), 106–108. 10.2307/3416443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gefen A. (2018). The future of pressure ulcer prevention is here: Detecting and targeting inflammation early. EWMA Journal, 19(2), 7–13. https://ewma.org/fileadmin/user_upload/EWMA.org/EWMA_Journal/articles_previous_issues/Gefen_A.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gunningberg L., Sedin I.-M., Andersson S., Pingel R. (2017). Pressure mapping to prevent pressure ulcers in a hospital setting: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 72, 53–59. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutting G. (1989). Michel Foucault’s archaeology of scientific reason: science and the history of reason. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall K. D., Clark R. C. (2016). A prospective, descriptive, quality improvement study to investigate the Impact of a turn-and-position device on the incidence of hospital-acquired sacral pressure ulcers and nursing staff time needed for repositioning patients. Ostomy/ Wound Management, 62(11), 40–44. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/wmp/article/prospective-descriptive-quality-improvement-study-decrease-incontinence-associated [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna D. R., Paraszczuk A. M., Duffy M. M., DiFiore L. A. (2016). Learning about turning: Report of a mailed survey of nurses’ work to reposition patients. Medsurg Nursing, 25(4), 219. [Google Scholar]

- Herman L. E., Rothman K. F. (1989). Prevention, care, and treatment of pressure (decubitus) ulcers in intensive care unit patients. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine, 4(3), 117–123. 10.1177/088506668900400306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jocelyn Chew H. S., Thiara E., Lopez V., Shorey S. (2018). Turning frequency in adult bedridden patients to prevent hospital-acquired pressure ulcer: A scoping review. International Wound Journal, 15(2), 225–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch B. J., Tschannen D., Lee H., Friese C. R. (2011). Hospital variation in missed nursing care. American Journal of Medical Quality, 26(4), 291–299. 10.1177/1062860610395929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch B. J., Xie B., Dabney B. W. (2014). Patient-reported missed nursing care correlated with adverse events. American Journal of Medical Quality, 29(5), 415–422. 10.1177/1062860613501715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Källman U., Bergstrand S., Ek A. C., Engström M., Lindgren M. (2016). Nursing staff induced repositionings and immobile patients’ spontaneous movements in nursing care. International Wound Journal, 13(6), 1168–1175. 10.1111/iwj.12435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.-G., Park S., Ko J. W., Jo S. (2018). The relationship of subepidermal moisture and early stage pressure injury by visual skin assessment. Journal of Tissue Viability, 27(3), 130–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King H. (2019). Global health engagement missions: Lessons learned aboard US naval hospital ships. The Geneva Foundation Tacoma United States.

- Kottner, J., Cuddigan, J., Carville, K., Balzer, K., Berlowitz, D., Law, S., Litchford, M., Mitchell, P., Moore, Z., Pittman, J., Sigaudo-Roussel, D., Yee, C.Y., & Haesler, E. (2020). Pressure ulcer/injury classification today: An international perspective. Journal of Tissue Viability, 29(3), 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozier B., Erb G., Berman A., Snyder S. J., Buck M., Yiu L., Stamler L. L. (2018). Fundamentals of Canadian nursing. Concepts, Process, and Practice-Pearson. (pp. 1096–1119). http://www.pearsoncanada.ca/media/highered-showcase/9780133249781/Kozier_Nursing_Flyer_Revised.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kwong E. W., Hung M. S., Woo K. (2016). Improvement of pressure ulcer prevention care in private for-profit residential care homes: An action research study. BMC geriatrics, 16(1), 192. 10.1186/s12877-016-0361-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langemo D., Haesler E., Naylor W., Tippett A., Young T. (2015). Evidence-based guidelines for pressure ulcer management at the end of life. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 21(5), 225–232. 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.5.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. L., Bucher L., Heitkemper M. M., Harding M. M., Kwong J., Roberts D. (2016). Medical-surgical nursing-e-book: Assessment and management of clinical problems, Single Volume. Elsevier Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn P. (2010). Taylor’s handbook of clinical nursing skills. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn P. (2018). Taylor's clinical nursing skills: A nursing process approach. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Manderlier B., Van Damme N., Vanderwee K., Verhaeghe S., Van Hecke A., Beeckman D. (2017). Development and psychometric validation of PUKAT 2· 0, a knowledge assessment tool for pressure ulcer prevention. International Wound Journal, 14(6), 1041–1051. 10.1111/iwj.12758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson A., Lipschitz R. (1956). The nature and treatment of trophic pressure sores. South African Medical Journal, 30(11), 1129–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meesterberends E., Halfens R. J. G., Spreeuwenberg M. D., Ambergen T. A. W., Lohrmann C., Neyens J. C. L., Schols J. M. G. A. (2013). Do patients in Dutch nursing homes have more pressure ulcers than patients in German nursing homes? A prospective multicenter cohort study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 14(8), 605–610. 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles S. J., Nowicki T., Fulbrook P. (2013). Repositioning to prevent pressure injuries: evidence for practice. Australian Nursing and Midwifery Journal, 21(6), 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Z. (1988). Pressure area care and tissue viability. Perioperative Care, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Z. (2010). Bridging the theory–practice gap in pressure ulcer prevention. British Journal of Nursing, 19(15), S15–S18. 10.12968/bjon.2010.19.sup5.77703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore Z., Cowman S. (2015). Repositioning for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1). 10.1002/14651858.CD006898.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore Z., Cowman S., Conroy R. M. (2011). A randomised controlled clinical trial of repositioning, using the 30 tilt, for the prevention of pressure ulcers. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(17–18), 2633–2644. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03736.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore Z., Cowman S., Posnett J. (2013). An economic analysis of repositioning for the prevention of pressure ulcers. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(15–16), 2354–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Z., Patton, D., Avsar, P., McEvoy, N. L., Curley, G., Budri, A., Linda, N., Walsh, S., & O’Connor, T. (2020). Prevention of pressure ulcers among individuals cared for in the prone position: Lessons for the COVID-19 emergency. Journal of Wound Care, 29(6), 312–320. 10.12968/jowc.2020.29.6.312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore Z., Van Etten M. (2014). Ten top tips: Repositioning a patient to prevent pressure ulcers. Wounds International, 5(3), 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Morton P. G., Fontaine D. K., Hudak C., Gallo B. (2017). Critical care nursing: A holistic approach (Vol. 1). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- Newell Jr, Thornburgh P., & Fleming J., W. (1970). The management of pressure and other external factors in the prevention of ischemic ulcers. 10.1115/1.3425080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newton M. E. (1938). Pressure areas: Practical suggestions on how to prevent bed sores. The American Journal of Nursing, 38(8), 888–892. 10.2307/3413937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale F. (1860). Notes on nursing. What it is and what it is not… A facsimile of the first edition published in 1860 by D. Appleton and Co., etc . https://books.google.co.th/books?hl=en&lr=&id=_9pUAAAAcAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA57&dq=Nightingale+1860&ots=VSCRFjjA0E&sig=7w__SQPqFtNqOA56pm41CD4KW2c&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Nightingale%201860&f=false

- NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPI. (2014). Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: Clinical practice guideline. Cambridge Media. 10.1111/jan.12614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent P., Vitale B. (2014). Fundamentals of nursing (pp. 745–760). FA Davis Company. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil C. K. (2004). Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 17(2), 137–148. 10.1177/0897190004263217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostadabbas S., Yousefi R., Faezipour M., Nourani M., Pompeo M. (2011). Pressure ulcer prevention: An efficient turning schedule for bed-bound patients [Paper presentation]. The 2011 IEEE/NIH Life Science Systems and Applications Workshop (LiSSA). (pp. 159–162). IEEE. Dallas, TX, 75231, USA [DOI] [PubMed]

- Palfreyman S. J., Stone P. W. (2014). A systematic review of economic evaluations assessing interventions aimed at preventing or treating pressure ulcers. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(3), 769–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson M. J., Gravenstein N., Schwab W. K., van Oostrom J. H., Caruso L. J. (2013). Patient repositioning and pressure ulcer risk-monitoring interface pressures of at-risk patients. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 50(4), 477–488. 10.1682/jrrd.2012.03.0040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickham D., Ballew B., Ebong K., Shinn J., Lough M. E., Mayer B. (2016). Evaluating optimal patient-turning procedures for reducing hospital-acquired pressure ulcers (LS-HAPU): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 17(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter P. A., Perry A. G. E., Hall A. E., Stockert P. A. (2013). Fundamentals of nursing. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Renganathan B., Nagaiyan S., Preejith S., Gopal S., Mitra S., Sivaprakasam M. (2018). Effectiveness of a continuous patient position monitoring system in improving hospital turn protocol compliance in an ICU: A multiphase multisite study in India. Journal of the Intensive Care Society, 20(4), 309–315. 10.1177/1751143718804682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads J., Meeker B. J. (2008). Davis's guide to clinical nursing skills. FA Davis. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J. H. (1849). Remarks on cottam's spring-bed, and on the prevention of bed-sores. The Lancet, 54(1372), 633–634. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)71788-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saliba D., Rubenstein L. V., Simon B., Hickey E., Ferrell B., Czarnowski E., Berlowitz D. (2003). Adherence to pressure ulcer prevention guidelines: Implications for nursing home quality. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(1), 56–62. 10.1034/j.1601-5215.2002.51010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuriwo R., Dowding D. (2014). Nurses’ pressure ulcer related judgements and decisions in clinical practice: a systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(12), 1667–1685. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders G. J. (1916). Modern methods in nursing. WB Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan J. (1886). On decubitus acutus (acute bed-sore), with an unusual case. Glasgow Medical Journal, 26(4), 269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutt S. C., Tarver C., Pezzani M. (2018). Pilot study: Assessing the effect of continual position monitoring technology on compliance with patient turning protocols. Nursing Open, 5(1), 21–28. 10.1002/nop2.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D., Gefen A. (2019). The biomechanical protective effects of a treatment dressing on the soft tissues surrounding a non-offloaded sacral pressure ulcer. International Wound Journal, 16(3), 684–695. 10.1111/iwj.13082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea J. D. (1975). Pressure sores: Classification and management. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 112, 89–100. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1192654/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver J. (1967). Preventing pressure sores. British Medical Journal, 1(5541), 697. [Google Scholar]

- SM, Mokoena I. M.-M., Chauke J. D., Matlakala M. E., & Randa M. C, B M.. (2015). Juta's manual of nursing Volume 2: The practical manual (Vol. 1). Juta and Company Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Soban L. M., Hempel S., Munjas B. A., Miles J., Rubenstein L. V. (2011). Preventing pressure ulcers in hospitals: A systematic review of nurse-focused quality improvement interventions. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 37(6), 245-AP216. 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37032-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souther S. G., Carr S. D., Vistnes L. M. (1973). Pressure, tissue ischemia, and operating table pads. Archives of Surgery, 107(4), 544–547. 10.1001/archsurg.1973.01350220028007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springhouse. (2006). Nurse’s quick check - skills (Kelly W. J., Ed. Vol. 1). Lippincott William & Wiklins. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh S. (2017). Potter and Perry's fundamentals of nursing: second south Asia edition-E-book. Elsevier India. [Google Scholar]

- Sving E., Idvall E., Högberg H., Gunningberg L. (2014). Factors contributing to evidence-based pressure ulcer prevention. A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(5), 717–725. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayyib N. A. H. (2016). Use of an interventional patient skin integrity care bundle in the intensive care unit (Doctoral dissertation, Queensland University of Technology). [Google Scholar]

- Tayyib N., Coyer F. (2017). Translating pressure ulcer prevention into intensive care nursing practice. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 32(1), 6–14. 10.1097/ncq.0000000000000199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofthagen R., Fagerstrøm L. M. (2010). Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis—A valid method for developing knowledge in nursing science. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 24, 21–31. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00845.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treas L. S., Wilkinson J. M. (2012). Pocket Nursing Skills, what you need to know now. FA Davis. [Google Scholar]

- Treas L. S., Wilkinson J. M. (2013). Basic nursing: Concepts, skills, & reasoning. FA Davis. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi R., Alqahtani S. S., Albarraq A. A., Meraya A. M., Tripathi P., Banji D., . . . Alnakhli F. M. (2020). Awareness and preparedness of COVID-19 outbreak among healthcare workers and other residents of south-west Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional survey. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 482. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trumble H. C. (1930). The skin tolerance for pressure and pressure sores. Medical Journal of Australia, 2(22), 724–726. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1930.tb41843.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwee K., Grypdonck M., De Bacquer D., Defloor T. (2007). Effectiveness of turning with unequal time intervals on the incidence of pressure ulcer lesions. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 57(1), 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster J., Bucknall T., Wallis M., McInnes E., Roberts S., Chaboyer W. (2017). Does participating in a clinical trial affect subsequent nursing management? Post-trial care for participants recruited to the INTACT pressure ulcer prevention trial: A follow-up study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 71, 34–38. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner C., Kalichman L., Ribak J., Alperovitch-Najenson D. (2017). Repositioning a passive patient in bed: Choosing an ergonomically advantageous assistive device. Applied Ergonomics, 60, 22–29. 10.1016/j.apergo.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L. (2011). Foundations of basic nursing. Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson J., Van Leuven K. (2016). Fundamentals of nursing: Theory, concepts, & applications (vol. 2). FA Davis. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson J. M. (2016). Fundamentals of nursing. FA Davis Company. [Google Scholar]

- Yoost B. L., Crawford L. R. (2019). Fundamentals of nursing E-book: Active learning for collaborative practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-son-10.1177_23779608221106443 for Repositioning Practice of Bedridden Patients: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis by Abdulkareem S. Iblasi, Yupin Aungsuroch, Joko Gunawan, I. Gede Juanamasta and Cheryl Carver in SAGE Open Nursing