Abstract

Introduction:

Burns affecting the head and neck (H&N) can lead to significant changes in appearance. It is postulated that such injuries have a negative impact on patients’ social functioning, quality of life, physical health, and satisfaction with appearance, but there has been little investigation of these effects using patient reported outcome measures. This study evaluates the effect of H&N burns on long-term patient reported outcomes compared to patients who sustained burns to other areas.

Methods:

Data from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research Burn Model System National Database collected between 1996 and 2015 were used to investigate differences in outcomes between those with and without H&N burns. Demographic and clinical characteristics for adult burn survivors with and without H&N burns were compared. The following patient-reported outcome measures, collected at 6, 12, and 24 months after injury, were examined: satisfaction with life (SWL), community integration questionnaire (CIQ), satisfaction with appearance (SWAP), short form-12 physical component score (SF-12 PCS), and short form-12 mental component score (SF-12 MCS). Mixed regression model analyses were used to examine the associations between H&N burns and each outcome measure, controlling for medical and demographic characteristics.

Results:

A total of 697 adults (373 with H&N burns; 324 without H&N burns) were included in the analyses. Over 75% of H&N injuries resulted from a fire/flame burn and those with H&N burns had significantly larger burn size (p<0.001). In the mixed model regression analyses, SWAP and SF-12 MCS were significantly worse for adults with H&N burns compared to those with non-H&N burns (p<0.01). There were no significant differences between SWL, CIQ and SF-12 PCS.

Conclusions:

Survivors with H&N burns demonstrated community integration, physical health, and satisfaction with life outcomes similar to those of survivors with non-H&N burns. Scores in these domains improved over time. However, survivors with H&N burns demonstrated worse satisfaction with their appearance. These results suggest that strategies to address satisfaction with appearance, such as reconstructive surgery, cognitive behavior therapy, and social skills training, are an area of need for survivors with H&N burns.

Keywords: Face burns, Head & neck burns, Quality of life, Satisfaction with appearance, Community integration, Patient reported outcomes, Burn rehabilitation, Visible burns

1. Introduction

Despite advances in acute burn care and treatment of burn-related sequelae, many burn survivors experience disabling scarring deformities [1,2]. Extensive scarring not only causes functional impairment, limiting patients’ abilities to perform daily tasks and activities, but can also cause significant psychological and social distress [3-5]. In general, the head and neck (H&N) region is a highly specialized body area that holds key psychological and social functions [6]. Post-burn scarring can significantly impact each of these functions, as well as impairing patients’ respiratory functio [7], vision, oral continence [8], and the ability to express emotions [5].

H&N burns are common and affect many individuals every year [9]. Heilbronn et al. reported that over 200,000 patients were assessed in emergency departments in the United States due to H&N burns from 2009 to 2013 [10]. The high number of affected patients and the potential lifelong impact of H&N injuries highlight the need for the development and refinement of dedicated therapeutic strategies that can improve patient outcomes.

Secondary reconstructive surgery can help attenuate negative results such as scarring [11]. Although current techniques have demonstrated effectiveness in correcting functional disabilities, they have demonstrated suboptimal capacity to address psychological and social outcomes [12]. In a recent qualitative study on burn survivors with visible burns in Australia, the authors reported persistence of social and emotional challenges [14]. In a young adult burn population in the United States, burn survivors with facial burns experienced increased anger and sadness compared to those without facial injuries [14].

To our knowledge, limited research exists investigating long-term psychological, social, and physical outcomes for H&N burn survivors. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to evaluate psychosocial outcomes for H&N burn survivors using a longitudinal, multi-center burn outcomes database to explore the psychosocial and physical complications of those with H&N burns in comparison to those with non-H&N burns at long-term follow-up. Our hypothesis is that those with H&N burns will demonstrate worse psychosocial and physical outcomes than those with non-H&N burns.

2. Methods

2.1. Database

Data was obtained from the Burn Model System (BMS) National Database, funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. The BMS Database was established in 1993 to examine the functional and psychosocial outcomes of burn survivors and it includes both adults and children [15]. Data are collected from subjects at the time of hospital discharge and at 6, 12, and 24 months after injury. Informed consent is obtained from all included subjects, and each center’s Institutional Review Board oversees the data collection. Adult participants with burns between 1996 and 2015 were included in the study; the “head/neck burn” variable was used to stratify subjects into two groups: those with and without H&N burns. The enrollment criteria for the BMS National Database include those with more severe injuries. The current BMS Database enrollment criteria includes those who require autografting surgery for wound closure and are

0–64years of age with a burn ≥20% total body surface area (TBSA) OR

≥65years of age with a burn ≥10% TBSA OR

any age with a burn injury to their face/neck, hands, or feet OR

any age with a high-voltage electrical burn injury.

Modifications have been made to the BMS Database inclusion criteria over time. Details of the inclusion criteria, data collection process, and data collection sites can be found at http://burndata.washington.edu/. The BMS Database is an electronic, centralized database, that utilizes REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the BMS National Data and Statistical Center at the University of Washington [16]. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.

2.2. Demographic and clinical variables

Demographic data included age, gender, race/ethnicity, and employment status pre-injury. Medical data included the presence of H&N burn, burn size (TBSA burned), burn etiology, and length of hospital stay.

2.3. Outcome measures

The following patient-reported outcome measures were used to assess long-term functional and psychosocial outcomes.

2.3.1. Satisfaction with life (SWL)

The SWL score measures life satisfaction and has previously demonstrated reliability and validity [17]. Psychometric evaluation in spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, and burn populations has shown the instrument to be useful in evaluating trauma outcomes [18]. There are different factors that define life satisfaction: social relationships, work or school, personal satisfaction with religious or spiritual life, learning in addition to growth, and leisure [17]. Items are scored on a 1–7 Likert scale with a total of 5 items and a maximum score of 35; higher scores indicate greater life satisfaction.

2.3.2. Satisfaction with appearance (SWAP)

The SWAP scale is a validated and reliable tool used to determine satisfaction with appearance in the burn population [19]. Participants are asked to rate each item on the basis of their thoughts and feelings in regards to their appearance post-burn. Each of the 14 items is rated on a 7-point scale, 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (Table 4). Subscales include social distress, facial features, non-facial features, and perceived social impact. Scores for facial and non-facial features can range from 0 to 24 and scores for social distress and perceived social impact range from 0 to 18. Higher scores suggest greater dissatisfaction with appearance and body image following injury. Total scores range from 0 to 84.

Table 4 –

Comparison of high Satisfaction with Appearance Scale (SWAP) item scores between groups.

| SWAP item, percent high score (> = 5) | H&N burn 6 months, n=399 12 months, n=374 24 months, n=295 |

Non-H&N burn 6 months, n=334 12 months, n = 284 24 months, n=229 |

p-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Uncomfortable in the presence of family | |||

| 6-months | 20.5 | 13.4 | 0.009 |

| 12-months | 17.0 | 14.7 | 0.420 |

| 24-months | 19.4 | 10.6 | 0.006 |

| 2. Uncomfortable in the presence of friends | |||

| 6-months | 30.3 | 24.7 | 0.081 |

| 12-months | 30.8 | 23.2 | 0.028 |

| 24-months | 30.8 | 22.5 | 0.032 |

| 3. Uncomfortable in the presence of strangers | |||

| 6-months | 42.1 | 36.9 | 0.150 |

| 12-months | 43.9 | 34.9 | 0.019 |

| 24-months | 41.6 | 30.9 | 0.011 |

| 4. Satisfied with overall appearance | |||

| 6-months | 43.3 | 28.2 | 0.000 |

| 12-months | 40.9 | 26.8 | 0.000 |

| 24-months | 37.1 | 28.1 | 0.028 |

| 5. Satisfied with appearance of scalp | |||

| 6-months | 13.8 | 7.6 | 0.006 |

| 12-months | 16.9 | 6.2 | 0.000 |

| 24-months | 14.7 | 6.0 | 0.001 |

| 6. Satisfied with appearance of face | |||

| 6-months | 25.7 | 5.2 | 0.000 |

| 12-months | 24.5 | 6.6 | 0.000 |

| 24-months | 26.1 | 4.3 | 0.000 |

| 7. Satisfied with appearance of neck | |||

| 6-months | 28.7 | 4.4 | 0.000 |

| 12-months | 30.0 | 5.5 | 0.000 |

| 24-months | 28.6 | 3.9 | 0.000 |

| 8. Satisfied with appearance of hands | |||

| 6-months | 40.2 | 26.2 | 0.000 |

| 12-months | 40.7 | 25.5 | 0.000 |

| 24-months | 39.2 | 23.1 | 0.000 |

| 9. Satisfied with appearance of arms | |||

| 6-months | 42.3 | 21.3 | 0.000 |

| 12-months | 45.4 | 24.8 | 0.000 |

| 24-months | 40.2 | 20.9 | 0.000 |

| 10. Satisfied with appearance of legs | |||

| 6-months | 35.2 | 34.6 | 0.857 |

| 12-months | 35.8 | 32.5 | 0.381 |

| 24-months | 31.3 | 32.2 | 0.830 |

| 11. Satisfied with appearance of chest | |||

| 6-months | 30.3 | 9.6 | 0.000 |

| 12-months | 31.9 | 11.0 | 0.000 |

| 24-months | 30.6 | 9.0 | 0.000 |

| 12. Appearance interferes with relationships | |||

| 6-months | 30.9 | 23.6 | 0.027 |

| 12-months | 29.1 | 21.2 | 0.020 |

| 24-months | 32.0 | 23.9 | 0.041 |

| 13. Feel burn is unattractive to others | |||

| 6-months | 57.4 | 55.0 | 0.512 |

| 12-months | 53.8 | 51.0 | 0.477 |

| 24-months | 59.3 | 50.4 | 0.042 |

| 14. Don’t think people would want to touch me | |||

| 6-months | 35.9 | 28.5 | 0.029 |

| 12-months | 33.9 | 26.7 | 0.044 |

| 24-months | 29.3 | 26.4 | 0.458 |

H&N=head and neck.

Wilcoxon–Mann Whitney tests used to test differences between the two samples.

The Satisfaction with Appearance Scale (SWAP) contains 14 items rated on a 7-point scale with 1 indicating strongly disagree and 7 indicating strongly agree. Total scores range from 0-84 with higher scores indicating greater dissatisfaction with appearance and body image following injury.

2.3.3. Community integration questionnaire (CIQ)

The CIQ score is intended to provide a measure on an individual’s level of social integration (home and community integration). Gerrard et al. have validated this questionnaire in the adult burn injury population [20]. The overall score can range from 0 to 29, with a higher score indicating greater social integration. For the purposes of this study, the social integration sub-score was used (items 6 through 11 were summed, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 12). Most items are scored on a 3-point scale from 0 to 2. Sub-scores include home integration, social integration, and productivity. Most questions touch on individual performance on a specific activity within the household or community and whether it’s performed alone or by someone else.

2.3.4. The short form-12 (SF-12) version 2

The validated SF-12 Health Survey was created as a shorter version of the SF-36 to measure health status and well-being [21]. The SF-12 includes 2 sub-scores: the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS). Scores are standardized with a t-score transformation with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 with a maximum of 100 based on a U.S. population [22]. Scores greater than 50 represent above average health status.

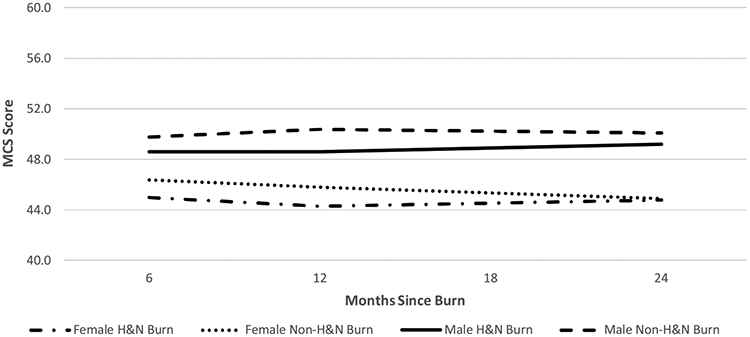

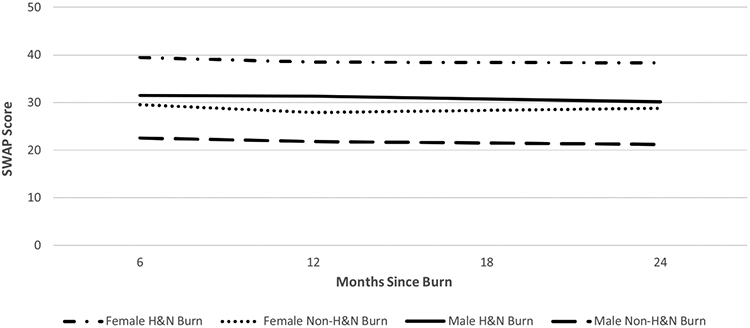

BMS Database subjects completed follow-up outcome questionnaires at 6±2months, 12±3months, and 24±6months post-injury. Subjects were divided into four groups: adult males with and without H&N burn and adult females with and without H&N burn. For each group and outcome measure, mean scores at each follow-up time point were determined and portrayed graphically (Figs. 1 and 2). The preliminary examination of raw data did not use tests of statistical significance given that the primary analyses utilized mixed models, controlling for confounding variables, to examine significance.

Fig. 1 – Mental composite summary (MCS) score of the SF-12 over time by gender and group.

H&N=head and neck.

*The mental component summary (MCS) score is one of 2 sub-scores of the short form 12 (SF-12). Scores are standardized with a t-score transformation with a mean of 50 (SD: 10) with a maximum score of 100. Higher scores indicate better quality oflife with scores greater than 50 representing above average health status.

Fig. 2 – Satisfaction with appearance scale (SWAP) score over time by gender and group.

H&N=head and neck

*The satisfaction with appearance scale (SWAP) contains 14 items rated on a 7-point scale with 1 indicating strongly disagree and 7 indicating strongly agree. Total scores range from 0 to 84 with higher scores indicating greater dissatisfaction with appearance and body image following injury.

3. Procedures

3.1. Regression analyses

Mixed models were employed for statistical analyses due to the study’s repeated measures design and uneven follow-up intervals. This statistical methodology also handles missing data and does not require imputation [23]. A model was created for each outcome measure (SWAP, SWL, CIQ, SF-12 PCS, and SF-12 MCS). If the interaction term (H&N burn by time) was not significant (p > 0.05), it was removed and the model was re-calculated. analyses was completed using STATA/SE version 13.1. Models included the following demographic and medical variables: age in 10-year increments, gender, race/ethnicity, employment status pre-injury, time since burn, presence of H&N burn, TBSA burned in 10% increments, burn etiology, and length of hospital stay.

3.2. Item and subscale level analyses

For outcome measures that were statistically different between the H&N and non-H&N populations in the mixed models, an item or subscale level analyses was used to explore the significant differences between the two groups. If the SWAP, SWL or CIQ were different between groups, the percentage of subjects reporting poor functioning for each item in the scale was examined for the H&N and non-H&N groups at all three follow-up time points. If the MCS or PCS was statistically different between groups, the eight component scales (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health) were examined because all items contribute to both the MCS and PCS scores. The Wilcoxon-Mann Whitney test was used to test differences between the two samples. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Results

4.1. Patients with H&N burns and non-H&N burns show dissimilar demographics

A total of 697 adults were included in the study; 373 subjects had H&N burns while 324 had burns elsewhere. The two groups were similar in age (H&N burns, 44.6±15.0years; non-H&N burns, 44.8±15.9years) and gender (H&N burns, 73.7% male; non-H&N burns, 71.6% male). However, the subjects with H&N burns had larger burn sizes (26.0±17.4 vs. 13.3±13.9; p<0.001), were more likely to have a fire/flame injury (76.7% vs. 42.6%; p<0.001), and had longer lengths of stay in the hospital (37.5±30.9 vs. 24.0±19.4; p<0.001). Full demographic and medical characteristics of the study populations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 –

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population.

| H&N burn (n = 373) | Non-H&N burna (n = 324) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (SD) | 44.6 (15.0) | 44.8 (15.9) | 0.80 |

| Burn size, mean percent (SD) | 26.0 (17.4) | 13.3 (13.9) | <0.01 |

| Length of stay, mean days (SD) | 37.5 (30.9) | 24.0 (19.4) | <0.01 |

| Male Gender, percent (n) | 73.7 (275) | 71.6 (232) | 0.53 |

| Etiology, percent (n) | |||

| Fire/flame | 76.7 (286) | 42.6 (138) | <0.01 |

| Scald | 1.6 (6) | 18.2 (59) | |

| Contact with hot object | 3.0 (11) | 10.5 (34) | |

| Grease | 5.6 (21) | 16.4 (53) | |

| Other | 13.2 (49) | 12.3 (40) | |

| Ethnicity/race, percent (n) | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 66.0 (246) | 63.9 (207) | 0.52 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 12.3 (46) | 15.1 (49) | |

| Hispanic | 15.6 (58) | 14.8 (48) | |

| Other | 6.1 (23) | 6.0 (20) | |

| Working pre-injury, percent (n) | 69.2 (258) | 61.7 (200) | 0.09 |

H&N=Head and Neck.

Non-H&N burn includes burns to the torso (31.8%, n=103), arms (48.5% n=157), hands (63.3%, n=205), legs (59.3%, n=192), or feet (53.7%, n=174). Individuals may have burns to more than one area.

4.2. Mixed model regression analyses

In the mixed models regression analyses, SWAP and MCS outcome measures were significantly worse for adults with H&N burns compared to those with non-H&N burns, controlling for demographic and clinical factors (p<0.01) (Tables 2 and 3). SWL, CIQ, and SF-12 PCS demonstrated no significant differences between those with and without H&N burns. Additionally, time was associated with improved scores for all five measures (p<0.05).

Table 2 –

Comparison of outcomes between head & neck and non-head & neck burn populations at 6, 12, and 24 months.

| Outcome | H&N burn |

Non-H&N burn |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months |

12 months |

24 months |

6 months |

12 months |

24 months |

|||||||

| Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | |

| MCS | 47.7 (11.8) | 394 | 47.5 (11.6) | 371 | 48.1 (11.9) | 287 | 49.0 (11.6) | 334 | 48.8 (12.3) | 273 | 48.4 (11.2) | 226 |

| PCS | 41.9 (10.7) | 394 | 43.2 (10.7) | 371 | 45.4 (11.2) | 287 | 44.0 (11.4) | 334 | 45.2 (11.6) | 273 | 47.2 (10.8) | 226 |

| SWAP | 33.3 (18.5) | 399 | 33.6 (19.6) | 374 | 32.3 (19.8) | 295 | 24.6 (16.7) | 334 | 23.5 (16.7) | 284 | 23.6 (16.5) | 229 |

| CIQ | 7.8 (2.6) | 397 | 7.7 (2.5) | 375 | 8.0 (2.5) | 298 | 7.8 (2.5) | 340 | 7.8 (2.4) | 285 | 7.8 (2.4) | 231 |

| SWL | 20.6 (8.4) | 402 | 20.3 (8.5) | 381 | 21.8 (8.5) | 296 | 21.2 (8.5) | 346 | 21.7 (8.7) | 286 | 21.5 (8.6) | 236 |

H&N=head and neck, MCS=mental component summary of the SF-12, PCS=physical component summary of the SF-12, SWAP=satisfaction with appearance scale, CIQ=community integration questionnaire, SWL=satisfaction with life scale.

Table 3 –

Mixed effects linear regression analyses examining association between head and neck burn and outcomes, controlled for demographic and clinical factors.

| MCS |

PCS |

SWAP |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff | Rob SE |

95% CI | p- Value |

Coeff | Rob SE |

95% CI | p- Value |

Coeff | Rob SE |

95% CI | p- Value |

|

| Head & neck burn | −3.01 | 1.09 | −5.16, −0.87 | <0.01 | −0.15 | 0.75 | −1.63, 1.33 | 0.85 | 6.91 | 1.25 | 4.46, 9.36 | <0.01 |

| Time since burn | −1.00 | 0.46 | −1.91, −0.1 | 0.04 | 2.36 | 0.29 | 1.78, 2.93 | <0.01 | −1.06 | 0.42 | −1.89, −0.23 | 0.01 |

| Age (units of 10years) | 0.10 | 0.65 | 0.05, 2.60 | 0.68 | −1.20 | 0.24 | −1.66, −0.74 | <0.01 | −0.84 | 0.38 | −1.58, −0.09 | 0.03 |

| Female gender | −3.33 | 0.85 | −5.0, −1.65 | <0.01 | −1.22 | 0.77 | −2.72, 0.29 | 0.11 | 8.02 | 1.37 | 5.32, 10.71 | <0.01 |

| Length of hospital stay | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.01 | 0.48 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.08, −0.02 | <0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.001, 0.08 | 0.04 |

| TBSA burned (units of 10%) | 0.33 | 0.27 | −0.20, 0.85 | 0.23 | −1.21 | 0.27 | −1.74, −0.68 | <0.01 | 1.20 | 0.45 | 0.33, 2.08 | 0.01 |

| Fire/flame burna | −0.79 | 0.86 | −2.47, 0.90 | 0.36 | 1.06 | 0.76 | −0.42, 2.54 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 1.30 | 2.85, 7.79 | 0.92 |

| Race/Ethnicityb | −2.10 | 0.79 | −3.64, −0.57 | 0.007 | −1.42 | 0.69 | −2.77, −0.072 | 0.04 | 5.32 | 1.26 | 2.85, 7.79 | <0.01 |

| Not employed at time of injuryc | −1.63 | 0.86 | −3.31, 0.05 | 0.06 | −2.85 | 0.80 | −4.42, −1.29 | <0.01 | −0.21 | 1.34 | −2.84, 2.42 | 0.88 |

| Constant | 55.13 | 1.76 | 51.69, 58.58 | <0.01 | 53.36 | 1.58 | 50.55, 56.76 | <0.01 | 14.10 | 2.71 | 8.78, 19.41 | <0.01 |

| CIQ |

SWL |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | Robust SE |

95% CI | p-Value | Coeff. | Robust SE |

95% CI | p-Value | |

| Head & neck burn | 0.26 | 0.18 | −0.09, 0.61 | 0.15 | −0.30 | 0.62 | −1.51, 0.92 | 0.63 |

| Time since burn | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.01, 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.61 | 0.21 | 0.20, 1.01 | <0.01 |

| Age (units of 10years) | −0.26 | 0.05 | −0.36, −0.16 | <0.01 | −0.19 | 0.19 | −0.55, 0.18 | 0.32 |

| Female gender | −0.003 | 0.17 | −0.35, 0.34 | 0.99 | −0.23 | 0.65 | −1.50, 1.04 | 0.72 |

| Length of hospital stay | −0.01 | 0.003 | −0.01, −0.002 | 0.007 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.04, −0.01 | 0.003 |

| TBSA burned (units of 10%) | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.21, 0.02 | 0.10 | −0.11 | 0.20 | −0.50, 0.27 | 0.57 |

| Fire/flame burna | −0.03 | 0.17 | −0.37, 0.31 | 0.85 | −0.09 | 0.62 | −1.30, 1.12 | 0.88 |

| Race/Ethnicityb | −0.88 | 0.16 | −1.19, −0.57 | <0.01 | −0.56 | 0.58 | −1.71, 0.58 | 0.34 |

| Not employed at time of injuryc | −0.45 | 0.18 | −0.81, −0.09 | 0.013 | −1.89 | 0.63 | −3.13, −0.65 | 0.003 |

| Constant | 10.10 | 0.36 | 8.87, 10.29 | <0.01 | 23.69 | 1.33 | 21.1, 26.3 | <0.01 |

MCS=mental component summary of the SF-12, PCS=physical component summary of the SF-12, SWAP=satisfaction with appearance scale, CIQ=community integration questionnaire, SWL=satisfaction with life scale, Coeff. = coefficient, TBSA = total body surface area.

Other burn is reference category to which fire/flame is compared. Other burn includes: scald, contact with hot object, grease, and other (including: tar, chemical, hydrofluoric acid, electricity, radiation, UV light, frostbite, TENS/Stevens Johnson, abrasions, flash burn, necrotizing fasciitis, meningococcemia, other skin disease, and missing/unknown).

Caucasian ethnicity is reference category to which non-white ethnicity is compared.

Employed is reference category to which not employed is compared.

4.3. Item and subcale level analyses

Item level data for SWAP was examined because scores were significantly different between H&N and non-H&N groups. SWAP items are scored on a 1–7 Likert scale with higher scores indicating greater dissatisfaction with appearance. The percentages of subjects with high scores (5, 6, or 7) were compared between the H&N and non-H&N groups. For all statistically significant items, the H&N group exhibited worse scores than the non-H&N group and most SWAP items were significantly different between the two groups at each of the time points (6 months: 10 of 14 items; 12 months: 11 of 14 items; 24 months: 12 of 14 items) (Table 4). The eight SF-12 scales were examined because MCS scores were statistically different between those with and without H&N burns. SF-12 scale scores are standardized to a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10; scores greater than 50 indicate an individual is doing better than the average of a national population-based sample. For all statistically significant scales between groups, the H&N group had worse scores than the non-H&N group, indicating a lower quality of life. The H&N group exhibited worse scores in 6 of 8 scales at 6 months, 3 of 8 scales at 12 months, and 2 of 8 scales at 24 months (Table 5).

Table 5 –

Comparison of SF-12 scores between groups.

| SF-12 Scale Score, Mean (SD) SF |

H&N burn 6-months, n=394 12-months, n=371 24 months, n=287 |

Non-H&N burn 6-months, n=334 12-months, n=273 24 months, n=226 |

p-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Functioning | |||

| 6-months | 42.9 (12.1) | 44.6 (12.5) | 0.0237 |

| 12-months | 44.4 (11.8) | 45.6 (11.8) | 0.1212 |

| 24-months | 46.1 (11.4) | 47.8 (11.4) | 0.0252 |

| Role Physical | |||

| 6-months | 41.0 (12.0) | 42.9 (12.2) | 0.0247 |

| 12-months | 42.4 (11.7) | 44.8 (12.1) | 0.0050 |

| 24-months | 44.4 (11.4) | 46.3 (11.8) | 0.0226 |

| Bodily Pain | |||

| 6-months | 41.4 (12.7) | 43.3 (12.8) | 0.0259 |

| 12-months | 42.1 (13.4) | 44.6 (13.6) | 0.0070 |

| 24-months | 45.5 (12.7) | 45.2 (13.1) | 0.8790 |

| General Health | |||

| 6-months | 45.9 (11.5) | 47.7 (11.0) | 0.0383 |

| 12-months | 45.9 (11.5) | 46.9 (12.0) | 0.1600 |

| 24-months | 47.0 (12.0) | 48.0 (11.3) | 0.5353 |

| Vitality | |||

| 6-months | 48.5 (11.1) | 50.4 (11.8) | 0.0084 |

| 12-months | 48.8 (11.4) | 50.0 (11.9) | 0.1377 |

| 24-months | 49.0 (11.8) | 51.1 (11.0) | 0.0619 |

| Social Functioning | |||

| 6-months | 44.8 (13.1) | 45.5 (13.3) | 0.3442 |

| 12-months | 44.0 (13.0) | 46.3 (13.3) | 0.0047 |

| 24-months | 45.1 (13.1) | 46.7 (12.3) | 0.1533 |

| Role Emotional | |||

| 6-months | 43.7, 12.8 | 45.2 (12.1) | 0.1191 |

| 12-months | 44.4, 11.5 | 45.8 (12.4) | 0.0315 |

| 24-months | 45.5, 11.8 | 45.6 (12.6) | 0.5650 |

| Mental Health | |||

| 6-months | 47.0 (11.5) | 48.3 (11.8) | 0.0660 |

| 12-months | 47.1 (12.0) | 48.9 (11.9) | 0.0594 |

| 24-months | 48.6 (12.4) | 48.4 (11.7) | 0.6594 |

H&N=head and neck.

Wilcoxon–Mann Whitney tests used to test differences between the two samples.

The Short Form 12 (SF-12) was created as a shorter version of the SF-36 to measure health and well-being. Scores are standardized with a t-score transformation with a mean of 50 (SD: 10) with a maximum score of 100. Higher scores indicate better quality of life with scores greater than 50 representing above average health status.

4.4. Post-hoc analyses

Given that gender was often a predictor in many of the mixed models examining outcomes, a post-hoc analyses was conducted examining gender differences in mean scores at each timepoint. For all five outcome measures, females with H&N burns had mean scores indicating worse outcomes than males. For four of the five outcomes, females with and without H&N burns had worse outcomes than males. Mean SWAP and MCS scores by gender and H&N group are illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2.

5. Discussion

It has long been postulated that patients with extensive facial burns confront a particular and more impairing set of challenges given the roles the face plays in social interactions, personal identity, and essential physiological functions [25,41]. Even so, objective data to corroborate these assumptions has been lacking, particularly in the U.S. population. This study employs a database containing self-reported patient outcome data to examine long-term psychosocial and functional outcomes of those with and without H&N burns.

The authors hypothesized that individuals with H&N burns would experience worse outcomes than individuals with non-H&N burns. The results, however, suggest that some elements of long-term physical and psychosocial well-being of patients with H&N burns are similar to those of patients with non-H&N burns indicating a degree of resiliency. Burn survivors with and without H&N burns reported similar satisfaction with life, community integration, and physical function outcomes when controlling for demographic and medical factors, including severity of injury. Importantly, however, adult H&N burn survivors demonstrated greater dissatisfaction with their appearance compared to patients with non-H&N burn injuries, and this dissatisfaction persisted over time. This dissatisfaction has also been shown to affect quality of life [24]. This finding is important in that scars often continue to change and improve with time and many reconstructive options are not available until a person’s scars have matured for a year.

Our findings support the results of several other studies that have found that survivors with facial burns experience more challenges with appearance [25,26]. Additionally, findings specific to the differences seen by race/ethnicity and gender are consistent with the literature. Studies in the burn population have shown burn survivors identifying as non-white to be more dissatisfied with their appearance than their white counterparts [27,28]. Studies in other populations have shown similar results as well as identify the face/head as a common area of concern in regard to appearance. Female sex is also often a predictor of body image dissatisfaction [29]. When asked about satisfaction with appearance, women with burn injury often report higher levels of dissatisfaction than men [30]. Further, in a study of social recovery after burn injury, women scored worse than men in several areas of social recovery such as social interactions and romantic and sexual relationships [32].

In a factor analyses using a burn population, SWAP was shown to be made up of four factors: subjective satisfaction with appearance– facial features, subjective satisfaction with appearance – non-facial features, social discomfort due to appearance, and social impact of appearance [19]. The scale items that are related to facial features are likely large contributors to the large differences in scores between those with and without H&N burns (coefficient: 6.91). However, in the examination of item level data, there were significant differences in scores of all items probing social impact of appearance at 24 months post-burn.H&N burn survivors also exhibited lower scores on the SF-12 MCS. The MCS has been shown to be a useful screening tool for both depression and anxiety in adults, indicating that survivors with burns in the H&N region may require more psychological support and intervention [32]. Similarities in patterns between the SWAP and SF-12 MCS scores in the adult H&N burn population indicate a possibility of interplay between facial appearance, social interactions, and mental health. This is consistent with other research, which suggests facial differences are linked with social withdrawal and psychological distress [33-35].

The findings of this study suggest that the adult H&N burn population may require significantly more resources in managing appearance and psychosocial health after a burn injury. One consideration is to increase access to secondary interventions, such as reconstructive surgery and laser treatments, to improve facial appearance and reduce the disfiguring impact of scarring. Continuous re-assessment of patients’ satisfaction with their appearance and post-acute reconstructive surgical interventions may benefit burn survivors and enhance their quality of life. There is a need to study the effects of surgical interventions on satisfaction with appearance.

In addition to surgical treatment options, there is a need for further research regarding non-surgical interventions for coping with a changed body image. The Phoenix Society for Burn Survivors is a national organization that provides resources for coping and peer support to burn survivors. The organization runs an online social skill training program, “Beyond Surviving: Tools for Thriving” that contains techniques to help burn survivors gain confidence in social situations [36]. Also, changing faces is an organization that provides various services for individuals with facial disfigurement, such as self-help guides for adults and children to assist with social interactions [37]. For example, one guide describes five techniques for social situations: explain, reassure, distract, assert, and humor. These methods attempt to empower those that have been affected by disfigurement and to help them feel comfortable with their appearance. Preliminary research on peer support after burn injury has demonstrated benefits in the realms of emotional and social recovery [38-41]. It is important to note that these interventions are targeted to social integration and do not attempt to change one’s internal appraisal of their appearance. To our knowledge, there are no interventions that focus on improving body appreciation after an acquired change in appearance, such as that from trauma or cancer. Body appreciation is defined as holding favorable opinions toward the body regardless of its appearance, accepting the body along with its deviations from societal body ideals, respecting the body by attending to its needs and engaging in healthy behaviors, and protecting the body by rejecting unrealistic media appearance ideals [42]. In nontrauma populations, interventions that promote self-compassion and mindfulness have been shown to improve body appreciation [43]. Similarly, interventions to reduce anxiety and appearance-related distress such as FaceIT, a computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy based intervention that offers psychosocial support for individuals with disfigurement, have been shown to be effective [44]. These interventions need to be explored in the burn population; researchers have advocated for establishing body image assessment and rehabilitation as a standard of care for patients with various medical disorders [45].

There are several limitations of this study. The inclusion criteria that the BMS Database uses selects those with more severe injuries. Therefore, results should be interpreted within the context of the population studied. The variable “head/neck burn” was used to define the study population since there is no variable for burns solely affecting the face. A longer follow-up could possibly detect additional significant differences. Additionally, it is likely that most survivors have not completed their reconstructive procedures by two years after burn, which may impact satisfaction with appearance at longer follow-up. Further, the BMS Database does not contain detailed information about burn-related surgeries, so it is not possible to determine if satisfaction with appearance was impacted by reconstructive procedures.

6. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that adult burn survivors with H&N burns show similar community integration, satisfaction with life and physical outcomes to those with non-H&N burns. However, survivors with H&N burns exhibit worse satisfaction with their appearance compared to those without H&N burns. Based on these results, it may be beneficial to incorporate cognitive behavioral therapy and social skills training into the long-term care plan of those with head and neck injuries. Future studies are needed to assess the efficacy of such interventions on satisfaction with appearance. This study adds to the growing literature in helping better define the longterm needs of burn survivors.

Funding source

This work was supported by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (grant numbers 90DP0035, 90DP0055, 90DPBU0001). The contents of this journal article were developed under grants from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant numbers 90DP0035, 90DP0055, 90DPBU0001). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this journal article do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- [1].Goel A, Shrivastava P. Post-burn scars and scar contractures. Indian J Plast Surg 2010;43(3):63, doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.70724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Van Baar ME, Essink-Bot ML, Oen IMMH, Dokter J, Boxma H, Van Beeck EF. Functional outcome after burns: a review. Burns 2006;32(1):1–9, doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fauerbach JA, Lezotte D, Hills RA, Cromes GF, Kowalske K, de Lateur BJ, et al. Burden of burn: a norm-based inquiry into the influence of burn size and distress on recovery of physical and psychosocial function. J Burn Care Rehabil 2004;26(1):21–32, doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000150216.87940.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Esselman PC. Community integration outcome after burn injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2011;22(2):351–6, doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gilboa D. Long-term psychosocial adjustment after burn injury. Burns 2001;27(4):335–41, doi: 10.1016/S0305-4179(00)00125-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Borah GL, Rankin MK. Appearance is a function of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;125:873–8, doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181cb613d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rosenberg M, Ramirez M, Epperson K, Richardson L, Holzer III C, Anderson CR, et al. Comparison of long-term quality of life of pediatric burn survivors with and without inhalation injury. Burns 2015;41(4):721–6, doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Burd A Burns: treatment and outcomes. Semin Plast Surg 2010;24 (3):262–80, doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1263068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sethi RKV, Kozin ED, Fagenholz PJ, Lee DJ, Shrime MG, Gray ST. Epidemiological survey of head and neck injuries and trauma in the United States. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;151(5):776–84, doi: 10.1177/0194599814546112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Heilbronn CM, Svider PF, Folbe AJ, Shkoukani MA, Carron MA, Eloy JA, et al. Burns in the head and neck: a national representative analysis of emergency department visits. Laryngoscope 2015;125(7):1573–8, doi: 10.1002/lary.25132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yamin MRA, Mozafari N, Mozafari M, Razi Z. Reconstructive surgery of extensive face and neck burn scars using tissue expanders. World J Plast Surg 2015;4(1):40–9. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4298864&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Xie B, Xiao SC, Zhu SH, Xia ZF. Evaluation of long term health-related quality of life in extensive burns: a 12-year experience in a burn center. Burns 2012;38(3):348–55, doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ryan CM, Lee A, Stoddard J Jr, Li NC, Schneider JC, Shapiro GD, et al. The effect of facial burns on long-term outcomes in young adults: a 5-year study. J Burn Care Res. 2018;39(4):497–506, doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irx006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Goverman J, Mathews K, Holavanahalli RK, Vardanian A, Herndon DN, Meyer WJ, et al. The National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research Burn Model System: twenty years of contributions to clinical service and research. J Burn Care Res 2017;38(1):e240–53, doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377–81, doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 1985;49(1):71–5, doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Amtmann D, Bocell FD, Bamer A, Heinemann AW, Hoffman JM, Juengst SB, et al. Psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale in people with traumatic brain, spinal cord, or burn injury. Assessment 2017, doi: 10.1177/1073191117693921 February 1:1073191117693921 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lawrence JW, Heinberg LJ, Roca R, Munster A, Spence R, Fauerbach JA. Development and validation of the satisfaction with appearance scale: assessing body image among burn-injured patients. Psychol Assess 1998;10(1):64–70, doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.10.1.64. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gerrard P, Kazis LE, Ryan CM, Shie VL, Holavanahalli R, Lee A, et al. Validation of the community integration questionnaire in the adult burn injury population. Qual Life Res 2015;24(11):2651–5, doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0997-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].WareJJ Kosinski MM, Keller SSD. A 12-Item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34(3):220–33, doi: 10.2307/3766749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ware J, Kosinski M, Dewey J. How to score version 2 of the SF-36® health survey. Medical Outcomes Trust and QualityMetric Incorporated; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61(3):310–7, doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fauerbach JA, Heinberg LJ, Lawrence JW, Munster AM, Palombo DA, Richter D, et al. Effect of early body image dissatisfaction on subsequent psychological and physical adjustment after disfiguring injury. Psychosom Med 2000;62(July–August (4)):576–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Warner P, Stubbs TK, Kagan RJ, Herndon DN, Palmieri TL, Kazis LE, et al. The effects of facial burns on health outcomes in children aged 5 to 18 years. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73(3 Suppl. 2):S189–96, doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318265c7df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lawrence JW, Fauerbach JA, Heinberg L, Doctor M. Visible vs hidden scars and their relation to body esteem. J Burn Care Rehabil 2016;25(1):25–32, doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000105090.99736.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jewett LR, Kwakkenbos L, Carrier ME, Malcarne VL, Bartlett SJ, Furst DE, et al. Examination of the association of sex and race/ethnicity with appearance concerns: a Scleroderma Patient-centered Intervention Network (SPIN) Cohort Study. Clin Ex Rheumatol 2016;34(September–October Suppl. 100 (5))92–9 Epub 2016 August 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wiechman S, Holavanahalli R, Roaten K, Rosenberg L, Rosenberg M, Meyer W, et al. The relation between satisfaction with appearance and ethnicity. J Burn Care Res 2018;39(April Suppl._(1)):S36. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Thombs BD, Notes LD, Lawrence JW, Magyar-Russell G, Bresnick MG, Fauberbach JA. From survival to socialization: a longitudinal study of body image in survivors of severe burn injury. J Psychosom Res 2008;64(February (2)):205–12, doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ghriwati NA, Sutter M, Pierce BS, Perrin PB, Wiechman SA, Schneider JC. Two-year gender differences in satisfaction with appearance after burn injury and prediction of five-year depression: A latent growth curve approach. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;98:2274–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gill SC, Butterworth P, Rodgers B, Mackinnon A. Validity of the mental health component scale of the 12-item short-form health survey (MCS-12) as measure of common mental disorders in the general population. Psychiatry Res 2007;152(1):63–71, doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Islam S, Ahmed M, Walton GM, Dinan TG, Hoffman GR. The association between depression and anxiety disorders following facial trauma—a comparative study. Injury 2010;41(1):92–6, doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Berscheid E, Gangestad S. The social psychological implications of facial physical attractiveness. Clin Plast Surg 1982;9(3):289–96. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7172580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Thompson AR, Clarke SA, Newell RJ, Gawkrodger DJ. Appearance Research Collaboration (ARC). Vitiligo linked to stigmatization in British South Asian women: a qualitative study of the experiences of living with vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 2010;163(3):481–6, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Phoenix Society for Burn Survivors. Beyond surviving: tools for thriving after burn injury. https://www.phoenix-society.org/our-programs/online-learning/beyond-surviving-tools.

- [37].Faces Changing. Self-Help Guides. https://www.changingfaces.org.uk/adviceandsupport/self-help-guides. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tolley JS, Foroushani PS. What do we know about one-to-one peer support for adults with a burn injury? A scoping review. J Burn Care Res 2014;35(1559-0488 (Electronic)):233–42, doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182957749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Badger K, Royse D. Helping others heal: burn survivors and peer support. Soc Work Health Care 2010;49(1):1–18, doi: 10.1080/00981380903157963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kornhaber R, Wilson A, Abu-Qamar MZ, McLean L. Coming to terms with it all: adult burn survivors’ ‘lived experience’ of acknowledgement and acceptance during rehabilitation. Burns 2014;40(4):589–97, doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Davis T, Gorgens K, Shriberg J, Godleski M, Meyer L. Making meaning in a burn peer support group: qualitative analysis of attendee interviews. J Burn Care Res 2014;35(5):416–25, doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Avalos L, Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow N. The body appreciation scale: development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 2005;2(3):285–97, doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Homan KJ, Tylka TL. Self-compassion moderates body comparison and appearance self-worth’s inverse relationships with body appreciation. Body Image 2015;15:1–7, doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bessell A, Brough B, Clarke A, Harcourt D, Moss TP, Rumsey N. Evaluation of the effectiveness of FaceIT, a computer-based psychosocial intervention for disfigurement-related distress. Psychol Health Med 2012;17(5):565–77, doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.647701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Pruzinksy T. Enhancing quality of life in medical populations: a vision for body image assessment and rehabilitation as standards of care. Body Image 2004;1(January (1)):71–81, doi: 10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00010-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]