This post hoc secondary analysis of the AFIRE randomized clinical trial investigates if rivaroxaban monotherapy is associated with a lower incidence of cardiovascular/bleeding events than combination anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and stable coronary artery disease.

Key Points

Question

Is rivaroxaban monotherapy associated with a lower incidence of total cardiovascular and/or bleeding events than combination anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and stable coronary artery disease?

Findings

In this post hoc secondary analysis of the Atrial Fibrillation and Ischemic Events With Rivaroxaban in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease (AFIRE) trial including 2215 participants, rivaroxaban monotherapy was associated with a 38% lower risk of total cardiovascular and bleeding events, which remained statistically significant after adjusting for the first event as a time-dependent variable. The mortality risk after a bleeding event was higher than after a thrombotic event.

Meaning

Rivaroxaban monotherapy was associated with lower risks of total thrombotic and/or bleeding events in patients with atrial fibrillation and stable coronary artery disease.

Abstract

Importance

Appropriate regimens of antithrombotic therapy for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and coronary artery disease (CAD) have not yet been established.

Objective

To compare the total number of thrombotic and/or bleeding events between rivaroxaban monotherapy and combined rivaroxaban and antiplatelet therapy in such patients.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a post hoc secondary analysis of the Atrial Fibrillation and Ischemic Events With Rivaroxaban in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease (AFIRE) open-label, randomized clinical trial. This multicenter analysis was conducted from February 23, 2015, to July 31, 2018. Patients with AF and stable CAD who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting 1 or more years earlier or who had angiographically confirmed CAD not requiring revascularization were enrolled. Data were analyzed from September 1, 2020, to March 26, 2021.

Interventions

Rivaroxaban monotherapy or combined rivaroxaban and antiplatelet therapy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The total incidence of thrombotic, bleeding, and fatal events was compared between the groups. Cox regression analyses were used to estimate the risk of subsequent events in the 2 groups, with the status of thrombotic or bleeding events that had occurred by the time of death used as a time-dependent variable.

Results

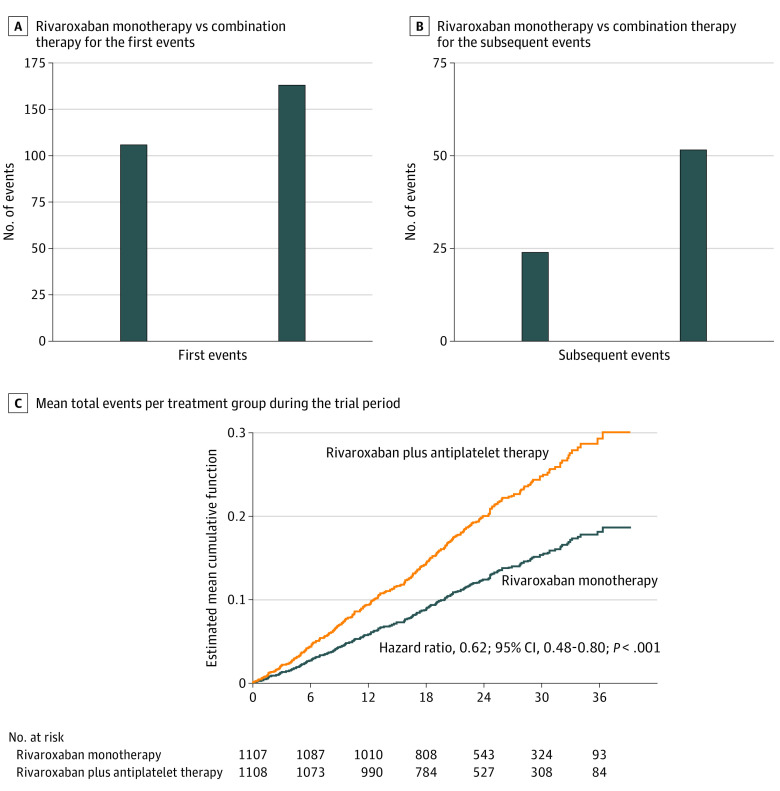

A total of 2215 patients (mean [SD] age, 74 [8.2] years; 1751 men [79.1%]) were included in the modified intention-to-treat analysis. The total event rates for the rivaroxaban monotherapy group (1107 [50.0%]) and the combination-therapy group (1108 [50.0%]) were 12.2% (135 of 1107) and 19.2% (213 of 1108), respectively, during a median follow-up of 24.1 (IQR, 17.3-31.5) months. The mortality rate was 3.7% (41 of 1107) in the monotherapy group and 6.6% (73 of 1108) in the combination-therapy group. Rivaroxaban monotherapy was associated with a lower risk of total events compared with combination therapy (hazard ratio, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.48-0.80; P < .001). Monotherapy was an independent factor associated with a lower risk of subsequent events compared with combination therapy. The mortality risk after a bleeding event (monotherapy, 75% [6 of 8]; combination therapy, 62.1% [18 of 29]) was higher than that after a thrombotic event (monotherapy, 25% [2 of 8]; combination therapy, 37.9% [11 of 29]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Rivaroxaban monotherapy was associated with lower risks of total thrombotic and/or bleeding events than combination therapy in patients with AF and stable CAD. Tapered antithrombotic therapy with a sole anticoagulant should be considered in these patients.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02642419

Introduction

Optimal antithrombotic therapy has been sought in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) complicated by coronary artery disease (CAD). Recently, the Atrial Fibrillation and Ischemic Events With Rivaroxaban in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease (AFIRE) trial demonstrated that in patients with AF with CAD, rivaroxaban monotherapy was associated with a lower risk of the first cardiovascular and major bleeding event as compared with standard combination therapy.1 However, primary efficacy and safety assessment are usually based on an investigation of time to first clinical event, as traditionally performed in clinical trials, only capturing the occurrence of the first event.2,3,4 Therefore, subsequent clinical events for the same patients are not accounted for, resulting in failure to capture the true burden of disease, such as multiple thromboembolisms, bleeding events after thromboembolism, and thrombotic events after bleeding. Analysis of recurrent events may accurately represent the true burden of CAD with AF. In fact, the US Food and Drug Administration has also accepted the use of recurrent events as a primary outcome because total events more fully reflect the disease burden of the patient over time.5,6

The aim of this secondary analysis of the AFIRE study was to determine whether anticoagulant therapy alone, compared with combination anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy, was associated with a lower incidence of total cardiovascular and/or bleeding events.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

This was a post hoc secondary analysis of the AFIRE trial, a multicenter, open-label, randomized clinical trial in which we enrolled patients with AF and stable CAD. After the exclusion of patients who had a technical reason for not participating in the trial, patients were randomly assigned to treatment groups. Details of the trial methodology were previously described (Supplement 1).1,7 In brief, we included men and women 20 years or older diagnosed with AF and stable CAD, those with a baseline CHADS2 score of 1 or more (includes the following categories: congestive heart failure, hypertension, age older than 75 years, diabetes, and prior stroke or transient ischemic attack), and those who met at least 1 of the following criteria: a history of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), including angioplasty with or without stenting, at least 1 year before enrollment; a history of angiographically confirmed CAD (stenosis of 50% or greater) not requiring revascularization; or a history of coronary artery bypass grafting at least 1 year before enrollment. Key exclusion criteria were a history of stent thrombosis, a coexisting active tumor, or poorly controlled hypertension. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment. The trial was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, Japan, and the institutional review boards of all participating institutions. Data were reviewed by an independent data and safety monitoring committee. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines.

Randomization and Treatment

In the primary AFIRE study, patients were registered in an online allocation system after the inclusion criteria were confirmed, and they signed the informed consent form. Patients were randomly assigned in equal numbers to either receive monotherapy with rivaroxaban (10 mg once daily for patients with a creatinine clearance of 15 to 49 mL/min or 15 mg once daily for patients with a creatinine clearance ≥50 mL/min) or combination therapy with rivaroxaban and an antiplatelet agent (aspirin or a P2Y12 inhibitor, according to the discretion of the treating physician).

End Points

The primary end point was the total number of first and subsequent events, including death, bleeding, and thrombotic events. The bleeding events were a composite of hemorrhagic stroke or major bleeding, as defined according to the criteria of the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. The thrombotic events were a composite of ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularization, or death from any cause. Blinded adjudication of the end points was conducted by an independent clinical events committee.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) values, whereas categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. We used the Poisson regression model to calculate rates and rate ratios for total thrombotic events and bleeding events and compared these between the monotherapy and combination-therapy groups. To investigate the association between the occurrence of thrombotic and bleeding events and the risk of mortality, we performed a Cox multivariate analysis, with the status of thrombotic or bleeding events having occurred as the first events as the time-dependent covariate. We constructed a multivariable model, including the time-dependent covariate and the following independent variables: assigned treatment group in the AFIRE trial, age (<75 years or ≥75 years), sex, diabetes type 1 and type 2, heart failure, hypertension, and a history of stroke and myocardial infarction.

The mean cumulative function was estimated using the Nelson-Aalen nonparametric method. We used the unadjusted Andersen-Gill model, including only the assigned treatment group as independent variable. The Andersen-Gill model originates from the common Cox proportional hazards regression model and assumes that the baseline intensity is the same across time, independent of the number of events.8,9

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4, for Windows (SAS Institute). All tests were 2-sided, and P values <.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Data were analyzed from September 1, 2020, to March 26, 2021.

Results

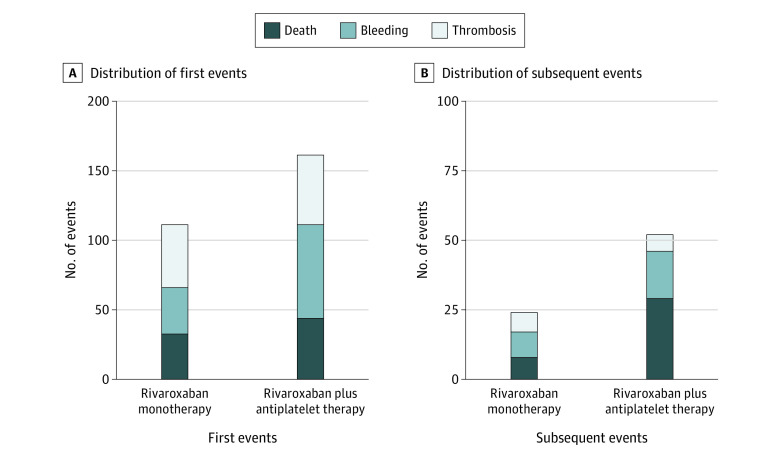

From February 23, 2015, to September 30, 2017, a total of 2 240 patients were enrolled at 294 centers; of these, 2215 patients (mean [SD] age, 74 [8.2] years; 1751 men [79.1%]; 464 women [20.9%]) were included in the modified intention-to-treat analysis. A total of 1107 patients (50.0%) were in the monotherapy group, and 1108 patients (50.0%) were in the combination-therapy group. Baseline characteristics did not differ statistically significantly among patients who experienced no events, only 1 event, and multiple events (Table). The number of total events, including death, bleeding, and thrombotic events, was 348 (first events, 272 [78.2%]; subsequent events, 76 [21.8%]) among 2215 patients, during a median follow-up of 24.1 (IQR, 17.3-31.5) months. The total event rate for the rivaroxaban monotherapy group was 12.2% (135 of 1107) and for the combination-therapy group was 19.2% (213 of 1108). Monotherapy demonstrated lower rates than combination therapy for the first and subsequent events by 31% (rate ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.55-0.87) and 54% (rate ratio, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.29-0.74), respectively (Figure 1A-B). The mortality rate was 3.7% (41 of 1107) in the monotherapy group and 6.6% (73 of 1108) in the combination-therapy group. Death accounted for 28.3% of the first events (77 of 272) and 48.7% of the subsequent events (37 of 76). Rivaroxaban monotherapy was associated with a 38% lower cumulative hazard of total events, including death from any cause, hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularization, and major bleeding, than combination therapy (hazard ratio [HR], 0.62; 95% CI, 0.48-0.80; P < .001) (Figure 1C). A breakdown of the events (death, bleeding, and thrombosis) is given in Figure 2. Among the first events, the incidence of thrombotic events was higher than that of bleeding or death in monotherapy group, whereas the incidence of bleeding events was higher than that of death and thrombosis in the combination-therapy group (thrombosis: monotherapy, 4.1% [45 of 1107] vs combination therapy, 4.5% [50 of 1108]; bleeding: monotherapy, 3.0% [33 of 1107] vs combination therapy, 6.0% [67 of 1108]; death: monotherapy, 3.0% [33 of 1107] vs combination therapy, 4.0% [44 of 1108]) (Figure 2A). For the subsequent events, death occurred more frequently in the combination-therapy group, whereas the incidences of death, bleeding, and thrombosis were similar in the monotherapy group (thrombosis: monotherapy, 0.6% [7 of 1107] vs combination therapy, 0.5% [6 of 1108]; bleeding: monotherapy, 0.8% [9 of 1107] vs combination therapy, 1.5% [17 of 1108]; death: monotherapy, 0.7% [8 of 1107] vs combination therapy, 2.6% [29 of 1108]) (Figure 2B). Time-adjusted, multivariable Cox regression analysis, including the first nonfatal bleeding event as the time-dependent variable, revealed that monotherapy was associated with lower risks of death than the combination therapy (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.39-0.83; P = .004) (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Similarly, monotherapy was associated with lower risks of death in a time-adjusted, multivariable Cox regression analysis with the first thrombotic event as the time-dependent variable (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.42-0.90; P = .01) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Table. Baseline Characteristics in Patients With No Events, 1 Event, or 2 or More Events.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monotherapy | Combination therapy | |||||

| No eventsa | 1 Eventa | ≥2 Eventsa | No eventsa | 1 Eventa | ≥2 Eventsa | |

| No. | 996 | 89 | 22 | 947 | 119 | 42 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 74.0 (8.3) | 75.9 (8.0) | 78.9 (7.4) | 73.9 (8.1) | 76.1 (8.6) | 78.6 (8.0) |

| ≥75 y | 512 (51.4) | 54 (60.7) | 16 (72.7) | 476 (50.3) | 72 (60.5) | 33 (78.6) |

| Male sex | 795 (79.8) | 66 (74.2) | 14 (63.6) | 748 (79.0) | 95 (79.8) | 33 (78.6) |

| Female sex | 201 (20.2) | 23 (25.8) | 8 (36.4) | 199 (21.0) | 24 (20.2) | 9 (21.4) |

| BMI, mean (SD)b | 24.6 (3.7) | 23.4 (3.7) | 24.1 (3.5) | 24.5 (3.7) | 24.8 (4.2) | 23.0 (3.3) |

| Type of AF | ||||||

| Paroxysmal | 546 (54.8) | 40 (44.9) | 10 (45.5) | 517 (54.6) | 43 (36.1) | 20 (47.6) |

| Persistent | 147 (14.8) | 13 (14.6) | 4 (18.2) | 142 (15.0) | 24 (20.2) | 9 (21.4) |

| Permanent | 303 (30.4) | 36 (40.4) | 8 (36.4) | 288 (30.4) | 52 (43.7) | 13 (31.0) |

| Hypertension | 854 (85.7) | 76 (85.4) | 17 (77.3) | 812 (85.7) | 99 (83.2) | 33 (78.6) |

| Diabetes | 408 (41.0) | 44 (49.4) | 9 (40.9) | 380 (40.1) | 63 (52.9) | 23 (54.8) |

| Dyslipidemia | 697 (70.0) | 69 (77.5) | 15 (68.2) | 647 (68.3) | 83 (69.7) | 27 (64.3) |

| Angina | 609 (61.1) | 60 (67.4) | 18 (81.8) | 608 (64.2) | 84 (70.6) | 31 (73.8) |

| Heart failure | 337 (33.8) | 42 (47.2) | 10 (45.5) | 315 (33.3) | 62 (52.1) | 22 (52.4) |

| Bleeding diathesis | 15 (1.5) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (4.5) | 10 (1.1) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (2.4) |

| Previous stroke | 131 (13.2) | 15 (16.9) | 2 (9.1) | 145 (15.3) | 20 (16.8) | 10 (23.8) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 345 (34.6) | 35 (39.3) | 4 (18.2) | 332 (35.1) | 48 (40.3) | 13 (31.0) |

| Previous peripheral arterial disease | 58 (5.8) | 8 (9.0) | 1 (4.5) | 56 (5.9) | 12 (10.1) | 4 (9.5) |

| Previous PCI | 704 (70.7) | 64 (71.9) | 13 (59.1) | 662 (69.9) | 89 (74.8) | 32 (76.2) |

| Type of stent, No./total No. (%) | ||||||

| Bare metal | 155/651 (23.8) | 15/59 (25.4) | 1/13 (7.7) | 140/610 (23.0) | 24/79 (30.4) | 7/32 (21.9) |

| Drug-eluting | 451/651 (69.3) | 39/59 (66.1) | 10/13 (76.9) | 408/610 (66.9) | 50/79 (63.3) | 19/32 (59.4) |

| Both types | 14/651 (2.2) | 3/59 (5.1) | 2/13 (15.4) | 30/610 (4.9) | 2/79 (2.5) | 4/32 (12.5) |

| Unknown | 31/651 (4.8) | 2/59 (3.4) | 0/13 (0) | 32/610 (5.2) | 3/79 (3.8) | 2/32 (6.3) |

| Previous CABG | 111 (11.1) | 13 (14.6) | 1 (4.5) | 107 (11.3) | 15 (12.6) | 5 (11.9) |

| Initial dose of rivaroxaban | ||||||

| 10 mg/d | 436 (43.8) | 47 (52.8) | 14 (63.6) | 426 (45.0) | 63 (52.9) | 24 (57.1) |

| 15 mg/d | 551 (55.3) | 40 (44.9) | 8 (36.4) | 512 (54.1) | 55 (46.2) | 18 (42.9) |

| CHADS2 score, median (IQR) | 2 (2-3) | 3 (2-3) | 3 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, median (IQR) | 4 (3-5) | 4 (3-6) | 4 (4-5) | 4 (3-5) | 4 (3-6) | 5 (4-6) |

| HAS-BLED, median (IQR) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) |

| CrCl | ||||||

| Mean (SD), mL/min | 63.9 (25.9) | 53.5 (22.2) | 51.3 (21.7) | 63.0 (24.3) | 55.2 (21.3) | 51.3 (19.4) |

| Distribution, No./total No. (%) | ||||||

| <30 mL/min | 42/946 (4.4) | 9/85 (10.6) | 3/22 (13.6) | 44/886 (5.0) | 12/112 (10.7) | 4/41 (9.8) |

| 30-<50 mL/min | 254/946 (26.8) | 36/85 (42.4) | 10/22 (45.5) | 241/886 (27.2) | 34/112 (30.4) | 18/41 (43.9) |

| ≥50 mL/min | 650/946 (68.7) | 40/85 (47.1) | 9/22 (40.9) | 601/886 (67.8) | 66/112 (58.9) | 19/41 (46.3) |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CHA2DS2-VASc, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age >75, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke or transient ischemic attack, vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, female sex score; CHADS2, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age older than 75 years, diabetes mellitus, and prior stroke or transient ischemic attack score; CrCl, creatinine clearance; HAS-BLED, hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, elderly, drugs/alcohol concomitant score; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

SI conversion factor: To convert creatinine clearance to milliliter per second per meter squared, multiply by 0.0167.

Categorized according to the number of major bleeding, hemorrhagic stroke, ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularization, and death from any cause.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Figure 1. Rate Ratios of the Monotherapy for the First and Subsequent Events Compared With Those of Combination Therapy and Mean Total Events per Treatment Group During the Trial Period.

A, Rivaroxaban monotherapy compared with combination therapy yielded 31% lower event rates for the first events. B, Rivaroxaban monotherapy compared with combination therapy yielded 54% lower event rates for the subsequent events. C, The mean cumulative function was estimated using the Nelson-Aalen nonparametric method. Total events included death from any cause, hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularization, and major bleeding, as defined according to the criteria of the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. Monotherapy yielded a significantly lower hazard of total events compared with combination therapy.

Figure 2. Distribution of First and Subsequent Events.

Breakdown of the first (A) and subsequent (B) events are shown for rivaroxaban monotherapy compared with rivaroxaban plus antiplatelet therapy.

Among the patients who had first thrombotic or bleeding events and subsequently died, bleeding events accounted for 75% (6 of 8) in the monotherapy group and 62.1% (18 of 29) in the combination-therapy group, indicating that bleeding events are clinically more impactful than thrombotic events in patients with AF and stable CAD receiving antithrombotic agents (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). The percentages of additional bleeding or thrombotic events in patients who experienced either nonfatal bleeding or thrombotic events as their first events are illustrated in eFigure 2 in Supplement 2. Bleeding events occurred more frequently than thrombotic events regardless of the types of the first event.

Discussion

The main findings of this post hoc secondary analysis of the AFIRE randomized clinical trial were that (1) rivaroxaban monotherapy as compared with combined rivaroxaban and an antiplatelet therapy was associated with a lower risk of total events, including both the first and the subsequent events; (2) bleeding events occurred more frequently than thrombotic events regardless of the type of first event; and (3) mortality rates after nonfatal bleeding events were higher than those after nonfatal thrombotic events. This study extends the main findings of the AFIRE study, showing a reduction in not only the first events but in the total events. These results reinforce the treatment benefit of rivaroxaban alone with respect to thrombosis and bleeding reduction.

Despite a relatively short median follow-up of 24.1 months, multiple nonfatal thrombotic and/or bleeding events occurred in the AFIRE trial. Thus, time-to-first-event analyses may underestimate the absolute benefit of therapy. As the relative risk reduction of total events was identical to that of first events with monotherapy, monotherapy contributed to the prevention of a substantial number of total events. It is noteworthy that death accounted for 28.3% of the first events and 48.7% of the subsequent events; thus, treatment effects of the monotherapy on death were underestimated in traditional Cox regression analyses for time to first event. Recurrent events may have implications not only for clinical decision-making but also for quality of life and health care costs, by requiring more interventions or hospitalizations. Evaluating the total number of events may provide a more comprehensive estimate of the treatment benefit when the study medication has been shown to reduce the first occurrence of the end point. Our findings are supported by those of a subanalysis of the PIONEER AF-PCI study in which total bleeding events, including those beyond the first event, were reduced with rivaroxaban-based dual antithrombotic therapy compared with triple therapy with warfarin.10 Specifically, reductions in first and total bleeding events were associated with antithrombotic drug reduction.

Optimal Regimen of Antithrombotic Therapy

A key issue for patients with AF and stable CAD is bleeding, which arises from multiple antithrombotic therapies consisting of antiplatelet and anticoagulation agents. Multiple antithrombotic therapies, compared with antiplatelet or anticoagulation monotherapy, are accompanied by a higher risk of bleeding events.11 Additionally, in a large, international PCI registry, major bleeding was reported as the main cause of in-hospital mortality compared to nonbleeding events.12 Moreover, bleeding events are associated with long-term mortality.13 Thus, reducing bleeding events may be a key factor in improving the prognosis in patients with AF and stable CAD, which was one of the rationales for the AFIRE study. A 2021 update of North American Perspective on antithrombotic therapy in patients with AF undergoing PCI states that (1) antiplatelet therapy should be discontinued at 1 year after PCI in most patients, (2) earlier discontinuation (eg, 6 months) can be considered in patients at low ischemic or high bleeding risk, and (3) continuation of antiplatelet therapy beyond 1 year should be considered only in select patients with high risk for ischemic recurrences and low bleeding risk.14 Similarly, a 2020 European Society of Cardiology guideline recommends dual therapy with oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy for the first 12 months after PCI for acute coronary syndrome, or 6 months after PCI in patients with chronic coronary syndrome.15

Potential Benefits of Anticoagulation Monotherapy

In the AFIRE study, we reported that rivaroxaban monotherapy was noninferior to combination therapy for the primary efficacy end point.1 The results were consistent with those in a recent study revealing that anticoagulation monotherapy was noninferior to anticoagulation plus antiplatelet therapy for the primary composite end points of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke or bleeding events in patients with AF and CAD who underwent coronary stent implantation, with a follow-up of 12 or more months.16 In the present study, we further investigated efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban monotherapy with regard to total event analyses, which may be more representative of real-world clinical practice, as patients receiving antithrombotic therapy often experience multiple clinical events.

Patients enrolled in AFIRE and treated with antithrombotic therapy not only had a high risk for recurrent cardiovascular and bleeding events but remained at an elevated risk for recurrence of those events over time. The approach of measuring just the first cardiovascular event often underestimates the burden of the disease and risks of the treatment on the patients. The evaluation of the first and subsequent events allows a broader assessment of the efficacy and safety of the treatment. This post hoc subanalysis of the AFIRE trial demonstrates that rivaroxaban monotherapy significantly reduced the total number of events.

Interestingly, bleeding events occurred more frequently than thrombotic events regardless of the nature of the first event in this study. In addition, the mortality rates after a nonfatal bleeding event were higher than those after a nonfatal thrombotic event. Bleeding events were clinically more important than thrombotic events in terms of mortality risk. As societies continue to age around the world, bleeding may be a prominent issue on which to focus. Thus, clinicians will have to consider tapering antithrombotic agents in patients after PCI to minimize their bleeding events.17

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. Analyses of recurrent events have an advantage over the traditional time-to-first-event approach in capturing treatment effects on the total disease burden, and it may increase statistical power. However, a consensus on the optimal statistical method for recurrent events has not yet been established. Therefore, we are not able to recommend any statistical method over another based on the present study, and statistical analysis will depend on trial-specific regulatory guidance. However, sensitivity analyses using the Prentice-Williams-Petersen total time model and the Prentice-Williams-Petersen gap time model as alternative statistical methods for recurrent event analyses demonstrated similar results to that of the Andersen-Gill model applied in the present study. Owing to the open-label design of the AFIRE study, our results may have been biased, although all events were adjudicated by the members of an independent committee who were unaware of trial-group assignments. In general, many patients discontinue drugs in blinded studies after a nonfatal event in double-blind studies, which can result in a higher proportion of subsequent events occurring with off-study drugs compared with the first event. However, in this study, many patients continued the study drug after a nonfatal event. Furthermore, our analyses did not take the severity of nonfatal events into consideration, although the prognostic effect of bleeding or thrombotic events are assumed to differ. Thus, we might have missed the true effects of the events analyzed in this study. Additionally, the study population received the rivaroxaban dose approved in Japan (10 mg or 15 mg once daily, according to the patient’s creatinine clearance) rather than the globally approved once-daily dose of 20 mg. However, pharmacokinetic modeling has shown that the level of rivaroxaban in blood samples obtained from Japanese patients who were taking rivaroxaban at the 15-mg dose was similar to the level in White patients who were taking the 20-mg dose.18 Finally, because our findings were from the cohort in the AFIRE trial conducted in Japan, they may not be generalizable to various populations with different thrombotic or bleeding risks and different comorbidities.

Conclusions

In conclusion, results of this post hoc secondary analysis of the AFIRE randomized clinical trial conducted in Japan showed that rivaroxaban monotherapy was associated with lower risks of total events, including both the first and subsequent events, than combination therapy. Bleeding events were more important than thrombotic events in terms of mortality risk. As societies continue to age around the world, bleeding may be a prominent issue on which to focus. Thus, clinicians will have to consider tapering antithrombotic agents in patients with AF after PCI to minimize their bleeding events.

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Percentages of Bleeding or Thrombotic Events as the First Events in Patients Who Subsequently Died

eFigure 2. Percentages of Additional Bleeding or Thrombotic Events in Patients Who Experienced Either Nonfatal Bleeding or Thrombotic Events as Their First Events

eTable 1. Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis for Mortality Risk With the First Nonfatal Thrombotic Event Treated as a Time-Dependent Variable

eTable 2. Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis for Mortality Risk With the First Nonfatal Bleeding Event Treated as a Time-Dependent Variable

Nonauthor Collaborators

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Yasuda S, Kaikita K, Akao M, et al. ; AFIRE Investigators . Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1103-1113. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. ; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators . Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in Type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-2128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. ; LEADER Steering Committee; LEADER Trial Investigators . Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311-322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. ; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators . Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1834-1844. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg B, Butler J, Felker GM, et al. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in patients with cardiac disease (CUPID 2): a randomised, multinational, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10024):1178-1186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00082-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon SD, Rizkala AR, Gong J, et al. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: rationale and design of the Paragon-HF trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(7):471-482. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yasuda S, Kaikita K, Ogawa H, et al. Atrial fibrillation and ischemic events with rivaroxaban in patients with stable coronary artery disease (AFIRE): protocol for a multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label, parallel group study. Int J Cardiol. 2018;265:108-112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.04.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozga AK, Kieser M, Rauch G. A systematic comparison of recurrent event models for application to composite endpoints. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0462-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amorim LD, Cai J. Modeling recurrent events: a tutorial for analysis in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(1):324-333. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi G, Yee MK, Kalayci A, et al. Total bleeding with rivaroxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2018;46(3):346-350. doi: 10.1007/s11239-018-1703-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toyoda K, Yasaka M, Iwade K, et al. ; Bleeding with Antithrombotic Therapy (BAT) Study Group . Dual antithrombotic therapy increases severe bleeding events in patients with stroke and cardiovascular disease: a prospective, multicenter, observational study. Stroke. 2008;39(6):1740-1745. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.504993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chhatriwalla AK, Amin AP, Kennedy KF, et al. ; National Cardiovascular Data Registry . Association between bleeding events and in-hospital mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2013;309(10):1022-1029. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Généreux P, Giustino G, Witzenbichler B, et al. Incidence, predictors, and impact of postdischarge bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(9):1036-1045. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angiolillo DJ, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with oral anticoagulation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a North American perspective: 2021 update. Circulation. 2021;143(6):583-596. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373-498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsumura-Nakano Y, Shizuta S, Komasa A, et al. ; OAC-ALONE Study Investigators . Open-label randomized trial comparing oral anticoagulation with and without single antiplatelet therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and stable coronary artery disease beyond 1 year after coronary stent implantation. Circulation. 2019;139(5):604-616. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasea L, Chung SC, Pujades-Rodriguez M, et al. Personalising the decision for prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy: development, validation, and potential impact of prognostic models for cardiovascular events and bleeding in myocardial infarction survivors. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(14):1048-1055. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanigawa T, Kaneko M, Hashizume K, et al. Model-based dose selection for phase III rivaroxaban study in Japanese patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2013;28(1):59-70. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.DMPK-12-RG-034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Percentages of Bleeding or Thrombotic Events as the First Events in Patients Who Subsequently Died

eFigure 2. Percentages of Additional Bleeding or Thrombotic Events in Patients Who Experienced Either Nonfatal Bleeding or Thrombotic Events as Their First Events

eTable 1. Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis for Mortality Risk With the First Nonfatal Thrombotic Event Treated as a Time-Dependent Variable

eTable 2. Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis for Mortality Risk With the First Nonfatal Bleeding Event Treated as a Time-Dependent Variable

Nonauthor Collaborators

Data Sharing Statement