Abstract

Background

Evidence-based health system guidelines are pivotal tools to help outline the important financial, policy and service components recommended to achieve a sustainable and resilient health system. However, not all guidelines are readily translatable into practice and/or policy without effective and tailored implementation and adaptation techniques. This scoping review mapped the evidence related to the adaptation and implementation of health system guidelines in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review following the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews. A search strategy was implemented in MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase, CINAHL, LILACS (VHL Regional Portal), and Web of Science databases in late August 2020. We also searched sources of grey literature and reference lists of potentially relevant reviews. All findings were reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews.

Results

A total of 41 studies were included in the final set of papers. Common strategies were identified for adapting and implementing health system guidelines, related barriers and enablers, and indicators of success. The most common types of implementation strategies included education, clinical supervision, training and the formation of advisory groups. A paucity of reported information was also identified related to adaptation initiatives. Barriers to and enablers of implementation and adaptation were reported across studies, including the need for financial sustainability. Common approaches to evaluation were identified and included outcomes of interest at both the patient and health system level.

Conclusions

The findings from this review suggest several themes in the literature and identify a need for future research to strengthen the evidence base for improving the implementation and adaptation of health system guidelines in low- and middle-income countries. The findings can serve as a future resource for researchers seeking to evaluate implementation and adaptation of health system guidelines. Our findings also suggest that more effort may be required across research, policy and practice sectors to support the adaptation and implementation of health system guidelines to local contexts and health system arrangements in low- and middle-income countries.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12961-022-00865-8.

Keywords: Health systems, Global health, Scoping review, Implementation science, Evidence-informed guidelines

Background

Evidence-informed guidelines are pivotal to reforming healthcare and strengthening health systems for healthier communities worldwide [1, 2]. WHO conceptualizes guidelines as a set of evidence-informed recommendations related to practice, public health or policy for informing and assisting decision-makers (e.g. policy-makers, healthcare providers or patients) [3]. In contrast to clinical practice guidelines focused on the appropriateness of clinical care activities, health system guidelines outline the required system, policy and/or finance components recommended to address health challenges [4, 5].

Despite the rigorous systematic synthesis of current research evidence focused on the development of high-quality guidelines, not all guidelines are readily and directly translatable into practice and/or policy [6, 7]. According to Balas and Boren, the small proportion of published evidence (approximately 14%) that does translate into practice can take upwards of 17 years from start to finish [8, 9]. Understanding implementation and adaptation strategies that facilitate the uptake of evidence-informed guidelines and recommendations is an urgent research and policy priority [10–13]. Implementation strategies are often defined as “methods or techniques used to enhance the adaptation, implementation, and sustainability of a program or practice” [14]. Guideline adaptation strategies involve systematically modifying guidelines developed in a specific environment to be suitable for application in other contextual settings (e.g. organizational or cultural) [15].

A review of WHO guidelines by Wang et al. [16] revealed a lack of implementation strategies that were evidence-based and involved active techniques (e.g. workshops, evaluation surveys, training) within their relevant implementation sections. WHO is currently focused on enhancing the adaptability of guidelines [17] and integrating adaptation strategies into their implementation plans [18]. For successful uptake, even high-quality international guidelines require adapting and tailoring to local contexts or circumstances [19]. To help achieve success, the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research (a WHO-hosted partnership) created the Research to Enhance the Adaptation and Implementation of Health Systems Guidelines (RAISE) portfolio, which aims to support decision-making on policy and systems in six low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [20]. However, much remains to be known about the factors and processes to enhance their adaptation and implementation [16, 20]. Additional evidence is needed to inform good practices, effective methods and evidence-based implementation and adaptation recommendations for the utilization of health system guidelines.

Neglecting to consider the interaction between contextual factors and guideline uptake is likely to lead to underperformance or failure [21–25]. It is important to recognize political, cultural and socioeconomic contexts and how these intersectional factors can influence health system guideline implementation and adaptation processes. Several methods have been derived for the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies to address these contextual needs [26]. Various taxonomies have been established as a means to better describe and categorize implementation strategies [27–33] and to conceptualize context to allow for the analysis of determinants (e.g. barriers and enablers) of implementation outcomes [34]. Frameworks have also been identified for adapting health-related guidelines, but often lack guidance on implementation [18, 35]. Therefore, the best methods for developing tailored implementation strategies and selecting adaptation frameworks remain to be identified [12, 18].

We conducted a preliminary search of PROSPERO, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. No reviews were identified that addressed adapting and implementing health system guidelines in LMICs. The search revealed a related overview of systematic reviews examining the effects of implementation techniques for health system initiatives that were deemed relevant to low-income countries (LICs) [36]. Despite this review and the acknowledged contextual differences between LICs and high-income countries (HICs), the findings were derived primarily from studies conducted in HICs, leaving a significant gap in the literature examining any contextual nuances of implementation and adaptation of health system guidelines specifically in LMICs.

The objective of this scoping review is unique, as it provides an overview of available evidence related to the implementation and adaptation of health system guidelines evaluated in LMICs. A focus on adaptation and implementation processes is a novel contribution in the literature by examining both of their strategies, interactions and influences. Recognizing the intricacy of contextual factors, we will only be examining implementation and adaptation strategies that directly happened in LMICs. We adopted an integrated knowledge translation approach by collaborating with a broad range of key informants, including the lead of each partner country in the WHO RAISE portfolio, throughout the review process to help ensure that the findings were relevant to knowledge users. Integrated knowledge translation is an approach to research where researchers and end-users work collaboratively to identify relevant knowledge gaps and ensure the production of actionable knowledge [37]. The results of this scoping review provide critical insight into the development of evidence-based implementation and adaptation recommendations for health system guidelines in LMICs.

Review aims

This scoping review assessed and mapped the available evidence related to adapting and implementing health system guidelines and recommendations in LMICs. The following research questions guided the review:

What are the common strategies and approaches for implementing health system guidelines and recommendations in LMICs?

What are the common strategies and approaches for adapting health system guidelines and recommendations in LMICs?

What are the commonly reported outcomes or indicators of success in adaptation and/or implementation of health system guidelines and recommendations in LMICs?

What are the commonly reported barriers and facilitators with respect to adaptation and/or implementation of health system guidelines and recommendations in LMICs?

Methods

This scoping review was guided by the methodological framework outlined by the JBI [38]. The framework includes six phases: (i) identifying the research question; (ii) searching for studies; (iii) selecting studies; (iv) extracting, charting and appraising data; (v) synthesizing and reporting findings; (vi) consulting with experts and key stakeholders [38].

Inclusion criteria

Population

In alignment with the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy of health system interventions [39], this review considered articles including any healthcare organizations, healthcare professionals or healthcare recipients targeted for change by health system guidelines within LMICs.

Concept

The concepts relevant for this review consist of the implementation and adaptation strategies, frameworks, and barriers and/or facilitators related to the adaptation and/or implementation of health system guidelines, policies and/or recommendations. Articles were required to explicitly state their intent to implement and/or adapt any evidence-informed health system guideline to be considered for inclusion. Health systems were conceptualized to encompass any system responsible for the provision of health services, finances, and/or governance [40]. Our review considered any evidence-informed (as reported by author) health system guidelines, regardless of the developer. Articles that described their intent to implement and/or adapt clinical practice guidelines were excluded.

Implementation and adaptation, while often undertaken simultaneously, are two distinct concepts being examined by this review. Implementation strategies were defined as any “methods or techniques used to enhance the adaptation, implementation, and sustainability” [14]. Adaptation strategies were defined as a “process of thoughtful and deliberate alteration to the design or delivery of an intervention, with the goal of improving its fit or effectiveness in a given context” [41]. Articles were required to report on the implementation and/or adaptation of health system guidelines to be considered for inclusion.

Context

Context in this review involved adaptation and/or implementation strategies applied in LMICs at a health system level. LMICs were defined by the World Bank standards based on gross national income for the 2021 fiscal year [42]. Studies or data related to HICs were excluded from this review.

Types of sources

This scoping review considered any quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods studies that evaluated the implementation and/or adaptation of health system guidelines in any LMICs. Articles that were descriptive in nature (e.g. editorials, commentaries, opinion papers) or did not have evaluation processes for assessing the implementation/adaptation strategy were excluded. Literature reviews that reported on relevant concepts were first reviewed for primary studies and then ultimately excluded. Studies published in English, not restricted by date of publication, were included.

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to locate both published and unpublished studies. An initial search of MEDLINE (Ovid) was undertaken by a librarian scientist to identify relevant studies of interest. The search strategy was developed using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles. A full search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid) is included in our Additional file 1. This search strategy underwent peer review by another librarian using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) [43] to ensure its accuracy. The search strategy was then adapted for each included information source. Lastly, primary studies from identified literature reviews were scanned for additional studies.

Information sources

We employed our search strategy in MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature; VHL Regional Portal), and Web of Science databases. Sources of grey literature included a search of the CADTH (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health) Grey Matters Tool, Google, Google Scholar, and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. These databases were chosen to capture potential articles across relevant countries.

Study selection

Search results were uploaded into Covidence systematic review software [45] for reference management. To ensure that eligibility criteria were uniformly applied by all reviewers, team members independently pilot-tested 20 citations and met to resolve any areas in need of clarification. Two reviewers then independently screened all titles and abstracts for assessment against the inclusion criteria. Full-text articles of potentially relevant studies were retrieved, and two reviewers independently assessed the full-text studies for eligibility. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion at each stage of the study selection process. If consensus could not be achieved, a third reviewer made the final decision. Reasons for exclusion of full-text studies were documented and are reported in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram [46].

Data extraction

Data were extracted using a predetermined extraction form to collect key findings relevant to the scoping review questions (Additional file 2). The main concepts in the data extraction form included year of publication, country, study aim(s), study population, setting, funding source, use of theoretical/conceptual frameworks, guideline description, implementation strategies, adaptation strategies, outcomes of interest, study methods, barriers and enablers, key results and stakeholder engagement [38]. Details regarding implementation strategies were extracted based on Proctor and colleagues’ recommendations for operationalizing and reporting implementation techniques [14]. This data extraction framework facilitated the collection of specific and pertinent data related to reported implementation strategies, such as duration, dose and justification. Further, the Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications–Enhanced (FRAME) was used to guide data extraction of adaptation strategies to capture the who, where, when, why and how aspects of modifications [41]. As this review seeks to examine implementation and adaptation as two distinct concepts, data on implementation and adaptation strategies were extracted independently of each other. If articles reported on both implementation and adaptation strategies, concepts related to processes such as barriers, enablers and outcomes were extracted independently. This could only be accomplished if authors explicitly stated which indicators (e.g. barriers, enablers and outcomes) related to which concepts (implementation or adaptation). If this level of detail was not provided, the data were still extracted but we were unable to infer which indicators related to which concepts. Data were also extracted if authors reported using a theoretical/conceptual framework to guide/justify their implementation and/or adaptation techniques. Two reviewers independently extracted details from the included articles, and disagreements were resolved with a third reviewer.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed using the JBI’s critical appraisal tools and the mixed-methods appraisal tool [47, 48]. Two reviewers independently completed the quality assessment. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. The results of this quality assessment were not used to exclude studies from the review but rather to provide greater insight into the current body of literature on this topic.

Data analysis

We began by categorizing each health system guideline based on the six “building blocks” that WHO identifies as core components to strengthening health systems: (1) service delivery, (2) health workforce, (3) health information systems, (4) access to essential medicines, (5) financing and (6) leadership or governance [49]. Health system guidelines were categorized into these building blocks based on their primary aim. Subsequently, directed content analysis was used to map implementation strategies according to the list of 73 implementation strategies and definitions outlined in the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project [28]. The ERIC framework was developed through iterative consultations with experts and literature to derive a comprehensive list of known implementation strategies [28]. Analysis was completed by two reviewers independently, and disagreements were resolved through consensus. Guided by the FRAME, thematic analysis was used to examine and group similarities in adaptation strategies and the who, what, where, why and when of any modification that took place. Lastly, the Capability, Opportunity and Motivation Behaviour (COM-B) model guided the coding of the reported barriers to and enablers of implementation and adaptation [30, 50]. The COM-B model is a theoretically driven, evidence-based framework that outlines a systematic process to identify and understand barriers and enablers with respect to implementation/adaptation of health initiatives [30, 50]. This model also links the identified barriers and enablers to the required mechanisms needed to enact change [51]. Mapping the findings onto published taxonomies, such as the ERIC framework to classify implementation strategies, the FRAME to detail important considerations to adaptation techniques, and the COM-B model to map barriers and enablers, allows for the identification of possible gaps in current knowledge and opportunities for future research [52]. Further, results summaries were stratified per LMIC lending groups (low-, lower-middle and upper-middle-income) and by using WHO’s six building blocks to assess for potential trends [49].

Descriptive summary tables of all included studies were created to outline extracted data specific to the health system guidelines, implementation strategies, adaptation strategies, outcomes/results, and article characteristics. Narrative summaries were included to address each research question.

Results

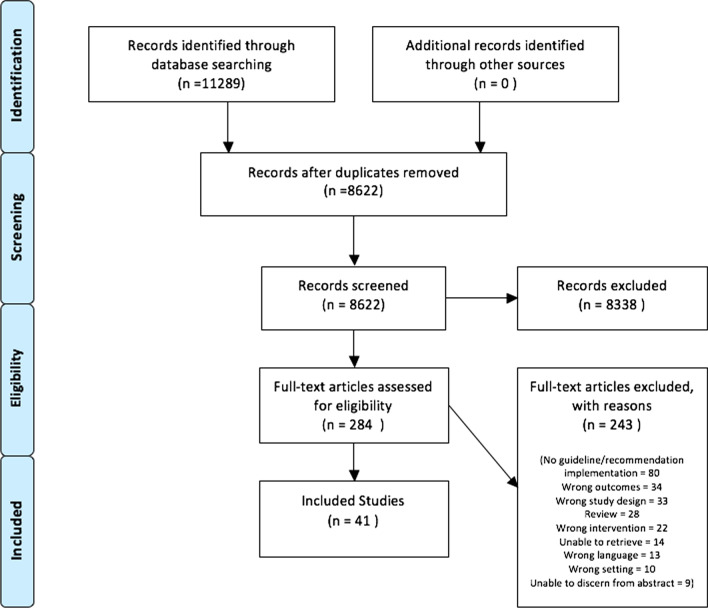

A total of 8622 unique references were identified from the search strategy. No additional citations were uncovered by searching the reference lists of relevant reviews or grey literature sources. After title and abstract screening, 284 papers remained for full-text review. Following this second stage of review, 41 articles were included for data analysis (see Fig. 1 for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [PRISMA] diagram) [53].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram

Article summary characteristics

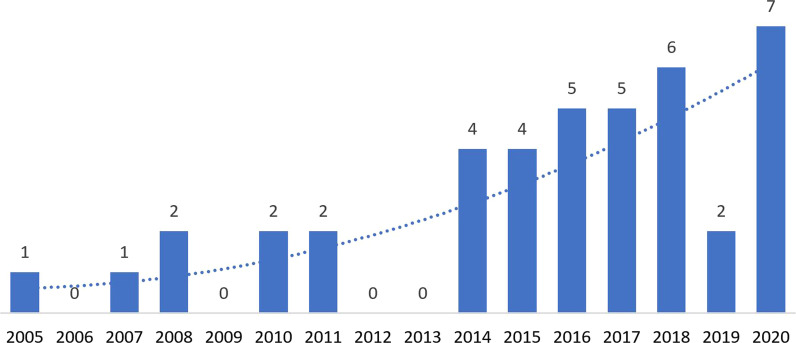

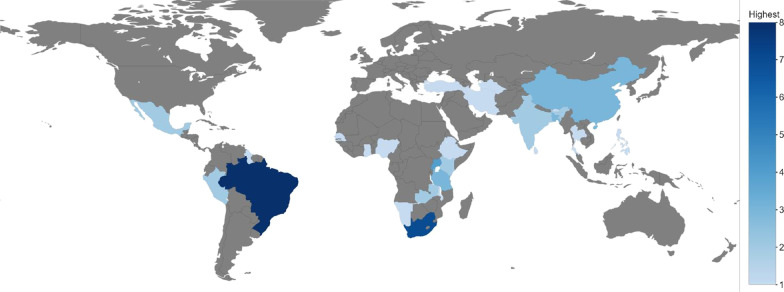

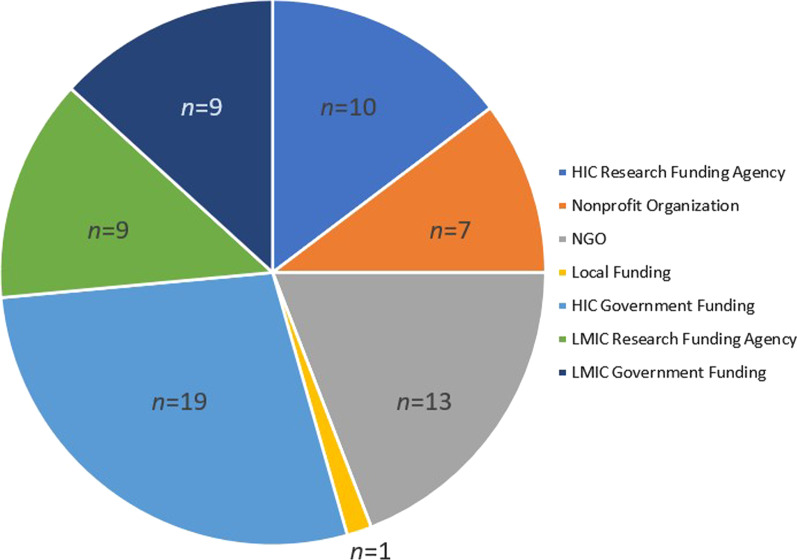

Identified articles were published between 2005 and 2010 (n = 6), 2011–2015 (n = 10), and 2016 and beyond (n = 25) (see Fig. 2). Studies were most frequently conducted in upper-middle-income countries (n = 21), followed by lower-middle-income countries (n = 14) and LICs (n = 5) (see Fig. 3). One study reported on case study findings from low-, middle-, and upper-middle-income countries. Twenty-two studies used qualitative methods, 14 studies employed mixed methods, and five used cross-sectional methods to answer their research questions. Sources of funding varied among studies and often included multiple sources (see Fig. 4). Most studies reported funding from an HIC source (n = 21) (e.g. Irish Aid, and United Kingdom’s Wellcome Trust). Other studies reported funding from local country/context initiatives (n = 6) and high-income and local country partnerships (n = 5). The remaining reported that no funding was received (n = 2) or did not report information on funding (n = 7). Healthcare workers and end-users were the most commonly targeted study populations. Settings varied across urban and rural locations and community and hospital sites. Articles reported implementing health system guidelines in urban hospitals (n = 7), both urban and rural communities (n = 7), only urban communities (n = 7), and both urban and rural hospitals (n = 5). Only one article reported on implementation of a guideline in both urban and rural clinics and hospitals. Please refer to Table 1 for a full summary of article characteristics. Any acronyms used in the tables can also be found in Additional file 3.

Fig. 2.

Yearly publication trend

Fig. 3.

Geographical clustering of health system initiatives

Fig. 4.

Reported funding sources. *One article may have reported multiple funding sources

Table 1.

Summary of article characteristics

| Year | Author(s) | Country (income bracket) | Funded by | Study methods | Study population | Study setting | Quality appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Amaral et al. [82] | Brazil (upper-middle-income) | Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation | Cross-sectional ecological study | Healthcare professionals, health system organization, family and community practice | Municipalities with a population between 5000 and 50,000 inhabitants | 100% (high) |

| 2011 | Blanco-Mancilla [84] | Mexico (upper-middle-income) | Not reported | Qualitative | Medical professionals who interact with service users or patients | Hospitals and health centres | 100% (high) |

| 2007 | Leethongdee [83] | Thailand (upper-middle-income) |

Royal Thai Government Office of Educational Affairs (Kor-Por London) Civil Service Commission Office (Kor-Por Thailand) |

Qualitative | Personnel who worked in the public healthcare system overseen by the ministry of health | Public health | 100% (high) |

| 2018 | Zakumumpa et al. [85] | Uganda (low-income) |

Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA) Wellcome Trust (United Kingdom) Department for International Development (DFID) Carnegie Corporation of New York Ford Foundation MacArthur Foundation |

Mixed-methods sequential explanatory | Heads of the ART clinic, head nurses, HR managers, clinicians, finance managers, strategy directors | Various health facilities in peri-urban settings or urbanized parts of rural areas | 100% (high) |

| 2020 | Miguel-Esponda et al. [69] | Mexico (upper-middle-income) | No financial support received | Mixed-methods convergent study design | Service users registered in the health information system (HIS) | Ten rural primary healthcare (PHC) clinics supported by CES [Compañeros En Salud] | 93% (high) |

| 2020 | Callaghan-Koru et al. [86] | Bangladesh (lower-middle-income) | United States Agency for International Development (USAID) | Qualitative case study | Mothers with children giving birth | In hospital setting—birthing units | 90% (high) |

| 2020 | Mutabazi et al. [87] | Sub-Saharan Africa (low-income) |

Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) (Canada) Integrated Intervention for Diabetes Risk after Gestational Diabetes in South Africa (IINDIAGO) (South Africa) |

Descriptive qualitative study | Pregnant women, women in labour/delivery and breastfeeding, frontline workers | Public health facilities | 90% (high) |

| 2018 | Saddi et al. [88] | Brazil (upper-middle-income) |

Graduate Studies Coordination Board (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel [CAPES]) Brazilian Ministry of Education Federal University of Goiás (UFG) Office of the Dean of Extension and Research |

Contingent mixed-methods approach | Frontline health workers; managers, nurses | Healthcare units in Goiânia; primary care setting | 86% (high) |

| 2015 | Xia et al. [89] | China (upper-middle-income) | Centre for Environment and Population Health (Griffth University) | Mixed methods | Pregnant women service users | Maternal and child healthcare hospitals | 86% (high) |

| 2014 | Armstrong et al. [90] | Tanzania (lower-middle-income) | Evidence for Action Tanzania | Qualitative | Healthcare professionals, health system coordinators, district, region and zonal health administrators | One regional referral hospital, one government district hospital and one faith-based district hospital | 80% (high) |

| 2011 | Ditlopo et al. [91] | South Africa (upper-middle-income) | Irish Aid | Qualitative case study design | Policy-makers, hospital managers, nurses and doctors | Predominantly district rural hospitals | 80% (high) |

| 2017 | Doherty et al. [92] | Uganda (low-income) |

Swedish and Norwegian government agencies South African Medical Research Council |

Descriptive qualitative | Implementation partners, Ministry of Health, multilateral agencies (UNICEF and WHO), district management, community- and facility-based health workers | All four regions of the country | 80% (high) |

| 2019 | Lovero et al. [93] | South Africa (upper-middle-income) |

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Wainberg/Arbuckle Training Grant United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) |

Mixed-methods exploratory design | District-level programme managers (DPMs) | Urban and rural primary care clinics throughout district | 80% (high) |

| 2014 | Mkoka et al. [94] | Tanzania (lower-middle-income) | Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) | Qualitative approach | District medical officer (DMO), district nursing officer (DNO), district health officer (DHO), district health secretary (DHS), and district pharmacist (DP) | A typical rural district | 80% (high) |

| 2016 | Moshiri et al. [95] | Iran (upper-middle-income) | School of Public Health Research Deputy of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) | Qualitative | Designers of public health facilities, provincial health managers, community health workers and two former health ministers | Rural healthcare facilities | 80% (high) |

| 2020 | Muthathi et al. [96] | South Africa (upper-middle-income) |

South African Research Chairs Initiative (SARChI) Department of Science and Innovation (South Africa) National Research Foundation (South Africa) Atlantic Philanthropies |

Nested qualitative study | Health policy actors: national government, provincial government head office, district, subdistrict and local government | Urban and rural provinces | 80% (high) |

| 2017 | Schneider and Nxumalo [97] | South Africa (upper-middle-income) |

Canadian International Development Research Centre (IDRC) Funded through a variety of other mechanisms that were not reported |

Qualitative case study | Community health | Community care, primary care clinics | 80% (high) |

| 2010 | Sheikh et al. [98] | India (lower-middle-income) |

Aga Khan Foundation’s International Scholarship Programme DFID TARGETS Consortium at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) University of London Central Research Fund |

Qualitative case study | Public health authorities, hospital administrators, medical practitioners |

Public health facilities Private health |

80% (high) |

| 2016 | Shelley et al. [99] | East Africa (lower-middle-income) | DFID (United Kingdom) | Qualitative approach | Healthcare workers | Rural community healthcare | 80% (high) |

| 2019 | Zhou et al. [67] | China (upper-middle-income) |

China Medical Board China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Central South University Post-Doctoral Science Foundation |

Mixed methods | Senior leaders, department directors from a town hospital, family members of patients | Liuyang Mental Health Prevention and Treatment Center (MHC) | 80% (high) |

| 2018 | Carneiro et al. [100] | Brazil (upper-middle-income) | Not reported | Cross-sectional quantitative descriptive | Physicians | Isolated primary care facilities in Marajó | 75% (high) |

| 2014 | Costa et al. [101] | Brazil (upper-middle-income) | No financial support received | Cross-sectional evaluative quantitative study | Doctors completing home visits and nurses providing individual care | Municipalities within Brazil | 75% (high) |

| 2018 | Sami et al. [102] | South Sudan, Africa (low-income) |

Save the Children’s Saving Newborn Lives programme ELMA Relief Foundation |

Mixed-methods case study | Newborns and mothers | Community/facility-based settings including PHC centre, community health programme centres, hospital and camps | 73% (high) |

| 2015 | Febir eta al. [103] | Ghana (lower-middle-income) |

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation ACT [artemisinin-based combination treatment] Consortium |

Qualitative study | Healthcare workers | District hospital, health centres and community-based health services | 70% (high) |

| 2017 | Pyone et al. [104] | Kenya (lower-middle-income) |

DFID UKAid |

Qualitative methods | 10 national-level policy-makers, 10 county health officials and 19 healthcare providers | 10 district- and county-level hospitals and other health facilities in selected counties | 70% (high) |

| 2020 | Rahman et al. [105] | Bangladesh (lower-middle-income) | GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) through PATH (Seattle, USA) | Qualitative descriptive | Key stakeholders, health service providers and caregivers | At both the national and district levels of Khulna and Lakshmipur, specifically in two subdistrict public healthcare facilities | 70% (high) |

| 2008 | Stein et al. [106] | South Africa (upper-middle-income) | IDRC (Canada) | Qualitative methods | PHC nurses | Urban and rural PHC settings | 70% (high) |

| 2017 | Bergerot et al. [79] | Brazil (upper-middle-income) | Not reported | Mixed methods | Psychologists and oncology staff; patients aged 18 or older, with cancer treatment plan | Hospitals and cancer centres from different Brazilian cities | 66.66% (medium) |

| 2010 | Halpern et al. [77] | Guyana (upper-middle-income) | Not reported | Cross-sectional | Doctors, nurses and data entry clerks from each care and treatment site | Clinics across the nation | 62.50% (medium) |

| 2020 | Ejeta et al. [107] | Ethiopia (low-income) | Not reported | Qualitative descriptive |

Three hospitals in Ethiopia Families within |

The health facility sites located in Addis Ababa, Bishoftu and Hawassa | 60% (medium) |

| 2016 | Smith Gueye et al. [108] | Bhutan, Mauritius, Namibia, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Turkey and Turkmenistan (low-, middle- and upper-middle-income) |

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Malaria Elimination Initiative of the Global Health Group (USA) |

Qualitative case study review | Healthcare and programme staff | Mostly in decentralized health systems | 60% (medium) |

| 2020 | Ryan et al. [109] | Nigeria (lower-middle-income) |

CBM Consultancy (Australian Government department) Comprehensive Community Mental Health Programme (CCMHP)’s monitoring and evaluation budget |

Mixed-methods manualized case study | Project coordinator, community mental health project officer, self-help group, development project officer and six community psychiatric nurses | Urban and semi-urban mental health clinics (some rural) | 60% (medium) |

| 2017 | Andrade et al. [75] | Brazil (upper-middle-income) | Not reported | Cross-sectional observational case study | Pregnant women or women with children under 2, suffering from chronic conditions and/or diabetes and hypertension | Primary and secondary healthcare | 50% (medium) |

| 2014 | Roman et al. [66] | Africa (lower-middle-income) | USAID | Qualitative observational case study | Pregnant women in Africa | Health system area | 50% (medium) |

| 2016 | Investigators of WHO Low Birth Weight (LBW) Feeding Study Group [110] | India (lower-middle-income) | WHO (Geneva) | Mixed-methods before-and-after study | Healthcare practitioners and parents of LBW babies | First-referral-level health facilities | 33% (low) |

| 2016 | Lavôr et al. [111] | Brazil (upper-middle-income) | Not reported | Mixed-methods multiple-case study | Nurses | Basic health units and four outpatient clinics, called specialty polyclinics | 27% (low) |

| 2005 | Bryce et al. [58] | Bangladesh, Brazil, Peru, Tanzania, Uganda (lower-middle-income) |

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation USAID |

Mixed methods | Health facilities with or without integrated management of childhood illness | Health facilities | 20% (low) |

| 2018 | Kihembo et al. [57] | Uganda (lower-middle-income) |

DFID WHO-AFRO Continuum of Care for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Adolescent and Child Health (RMANCH) USAID UNICEF Global Polio Eradication Initiative United Nations Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) WHO (Uganda) |

Qualitative descriptive study | Health workforce | District- and regional-level referral hospitals | 20% (low) |

| 2015 | Li et al. [112] | China (upper-middle-income) |

Law Department of National Health and Family Planning Committee Jinan Science & Technology Planning Project |

Mixed-methods field observation | Personnel of the health department of Shandong Province and health departments, directors, medical personnel of township hospitals | Six township hospitals and three village clinics | 6.60% (low) |

| 2015 | Wingfield et al. [113] | Peru (upper-middle-income) |

Wellcome Trust Innovation for Health and Development (FHAD) and the Joint Global Health Trials Consortium of the Wellcome Trust United Kingdom Medical Research Council DFID Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation British Infection Association Imperial College Centre for Global Health Research |

Mixed methods | Project team, project participants, civil society and stakeholders | Two suburbs of Peru’s capital, Lima | 6.60% (low) |

| 2018 | Kavle et al. [114] | Kenya (lower-middle-income) | USAID | Qualitative | Mothers | Community care health facilities | 0% (low) |

Health system guidelines

Table 2 summarizes the health system guidelines implemented in the included studies. While specific guidelines varied across studies, out of the total 41 studies, three reported on implementation of the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines and another three outlined the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV/AIDS guidelines.

Table 2.

Health system guideline/recommendation overview

| Author/year | Guideline/recommendation name | Study aim and objectives | Description | Health system building block |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaral et al. (2008) [82] | Integrated management of childhood illnesses (IMCI) | Describe factors associated with the implementation of IMCI in north-eastern Brazil | IMCI aims to reduce mortality and morbidity associated with childhood diseases by improving three key components: (1) performance of health professionals using standardized protocols; (2) improving the health system organization by means of adequate support for the availability of resources; (3) health promotion practices through family and community-based activities | Service delivery |

| Andrade et al. (2017) [75] | Attention to chronic conditions model (ACCM) was adapted to create lab for innovations in chronic conditions (LIACC) |

Address implementation of LIACC Document the main challenges and lessons learned to suggest a more suitable chronic care model at the municipal level |

Adapted from the seven steps of ACCM, LIACC implements four macro processes used as a management tool in primary healthcare (PHC) for chronic conditions: (1) evaluation of infrastructure; (2) focus on primary care to acute health services; (3) management and monitoring of chronic conditions; (4) management and monitoring of home healthcare visits | Service delivery |

| Armstrong et al. (2014) [90] | Maternal and perinatal death reviews (MPDR) | Explore the current implementation of MPDRs in Tanzania | MPDR encourages multidisciplinary team discussions from staff involved in the patients’ care as well as a review of the patients’ documentation to identify avoidable factors and opportunities for improvement | Health workforce |

| Bergerot et al. (2017) [79] | Psycho-oncology programme |

Characterize the use of screening measures for psychologists from different oncology services Present the preliminary results from this programme implementation and development |

The programme was subdivided into six actions: screening of distress, anxiety, depression, quality of life; classification of risk criteria; discussion by the psychology team; synthesis and discussion with healthcare team; evidence-based results analysis; treatment plan and record in medical records | Service delivery |

| Blanco-Mancilla (2011) [84] | Popular health insurance (PHI) programme |

Understand why health policies differ across Mexico City Identify issues that contribute to the success or failure of translating policy into practice |

Providing healthcare coverage to previously excluded populations | Service delivery |

| Bryce et al. (2005) [58] | MCI strategy | Compare the programme (IMCI) expectation findings of the Multi-Country Evaluation of IMCI Effectiveness, Cost and Impact (MCE-IMCI) to the five most important programme expectations from the IMCI impact model |

IMCI is a strategy for reducing mortality among children under the age of 5 years UNICEF, WHO and their technical partners developed the strategy in a stepwise fashion, seeking to address limitations identified through experience with disease-specific child health programmes, and those addressing diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infections |

Service delivery |

| Callaghan-Koru et al. (2020) [86] | Chlorhexidine (CHX) cleansing policy | Identify and compare facilitators of and barriers to the institutionalization and expansion strategies of the national scale-up of CHX | Prioritizes several newborn health interventions such as kangaroo mother care, management of newborn infections and ensuring essential newborn care including the application of CHX to the umbilical cord | Service delivery |

| Carneiro et al. (2018) [100] | More physicians for Brazil programme (MPBP) as part of the Family Health Strategy (FHS) | To evaluate the performance of the FHS, through the deployment of MPBP in Marajó-Pa-Brazil | Broadening the access to basic healthcare services and connecting the teams to individuals, families and communities in the complex task of taking care of life | Access to essential medicine |

| Costa et al. (2014) [101] | FHS | To re-evaluate the implementation of the FHS in the state of Santa Catarina between 2004 and 2008 by considering indicators of potential coverage, evidence of change in the care model, and the impact on hospitalizations |

Characteristics of the FHS are teamwork and ascribed distribution of patients, with a forecasted number of families/individuals under its responsibility Proactive approach to the health of the community ascribed which relies on territorialization, family registers, diagnoses of health situations and health initiatives developed in partnership with the community |

Service delivery |

| Ditlopo et al. (2011) [91] | Rural allowance policy | Analyse policy implementation and effectiveness and its influence on motivation and retention | Attract and retain health professionals to work full-time in public health services in rural, underserved and other inhospitable areas identified by provincial health departments | Financing |

| Doherty et al. (2017) [92] | Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV/AIDS (PMTCT) (Option B+) | Present findings from a rapid assessment of PMTCT Option B+ implementation in Uganda 3 years after policy adoption | PMTCT evolved progressively from single-dose nevirapine prophylaxis in 2000 to the current recommendation that all pregnant and breastfeeding women, irrespective of CD4 count, should receive lifelong antiretroviral treatment (ART), known as Option B+ | Service delivery |

| Ejeta et al. (2020) [107] | Strengthening Ethiopia’s Urban Health Promotion (SEUHP) implemented the Urban Community Health Information System (UCHIS) | Document the challenges and lessons learned in the UCHIS implementation process | Each of the 15 health service packages identified contained service cards and tally sheets to help improve data collection and standardization | Health information system |

| Febir et al. (2015) [103] | Integration of rapid diagnostic test (RDT) in IMCI | Evaluate and report the issues health workers faced in integrating RDT management into their working practices | In 2010 IMCI was adapted wherein case management of malaria should be a test-based approach, and therefore the integration of a rapid diagnostic test (RDT)-based intervention was undertaken | Service delivery |

| Gueye et al. (2016) [108] |

Malaria elimination programmes: Global technical strategy for malaria (GTS) Action and Investment to defeat Malaria (AIM) Global Malaria Eradication Programme (GMEP) |

Examine countries in different socioeconomic, political and ecological contexts and evaluate how the health system has operated within the context of different political, financial and human resources activities Identify how countries have implemented elimination programmes, and adapted their malaria elimination strategies |

GTS: provided the framework for achievement of elimination and establishing an elimination goal for 35 countries. Programme to reach global goals for malaria control, elimination and eventually eradication AIM: an action framework to reduce malaria through the Roll Back Malaria Partnership GMEP: based on vertical time-limited interventions deployed through centralized health systems at the national level |

Service delivery |

| Halpern et al. (2010) [77] | The patient monitoring system (PMS) for patients with HIV |

Describe the process used to implement PMS Provide examples of the programme-level data Highlight benefits for national programmes |

PMS is used for patient care and data collection The physical components of the WHO HIV care and ART PMS include a patient chart, two patient registers, and cross-sectional and cohort analysis reporting form |

Health information system |

| Investigators of WHO Low Birth Weight (LBW) Feeding Study Group (2016) [110] | LBW feeding guidelines in first-referral-level health facilities | Evaluate the effect of implementing WHO LBW feeding guidelines |

Guidelines aim to improve knowledge and skills of health workers Guidelines for optimal feeding of LBW infants, to improve care and survival of LBW infants |

Health workforce |

| Kavle et al. (2018) [114] | Baby-Friendly Community Initiative (BFCI) |

Describe the implementation process Discuss success, challenges, lessons learned and opportunities for integration into other health areas |

Through mother-to-mother community support groups, BFCI addresses breastfeeding and nutrition challenges by providing educational interventions in community gardens, water, sanitation and hygiene | Service delivery |

| Kihembo et al. (2018) [57] | Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) | Describe the design and process of IDSR revitalization, highlighting the rollout of the revised IDSR guidelines through structured training of the health workforce up to the operational level nationwide |

Strategy aimed at strengthening integrated, action-oriented public health surveillance and response at all levels of the health system Focused on detection, registration, conformation, reporting, data analysis and provision of feedback |

Service delivery |

| Lavôr et al. (2016) [111] | Directly observed treatment, short-course (DOTS) | Assess the degree of implementation of the DOTS strategy for tuberculosis (TB) in a large city | DOTS is based on five fundamental components: sustained political and financial commitment; diagnosis through quality-ensured sputum-smear microscopy; standardized short-course anti-TB treatment; a management system for uninterrupted supply of anti-TB drugs; information system that allows monitoring and evaluation of actions and their impacts | Access to essential medicine |

| Leethongdee (2007) [83] | Universal coverage (UC) healthcare reform |

Understand the factors influencing the implementation at a local level Build a general account of the reforms that fit each of three individual provincial cases |

UC reform objective was to reduce geographical inequalities in funding and workflow distribution, problems in resource allocation, lack of progress in developing primary care, and tension between curative and preventative care approaches | Financing |

| Li et al. (2015) [112] | WHO essential drugs policy |

Analyse the impact on village-level and township-level health service system Summarize the effectiveness of implementing essential drugs policy; identify the problems of various aspects Conduct an in-depth analysis of the causes, and provide ways to improve the essential drugs policy |

Essential drug policy aims to improve the availability of essential drugs and to promote rational drug use | Access to essential medicine |

| Lovero et al. (2019) [93] | The National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2013–2020 (the Strategic Plan) |

Gain knowledge on stepped-care procedures for management of mental illness in primary care services Determine the degree to which integrated procedures have been implemented Identify challenges encountered in coordination of integration efforts |

The Strategic Plan aims to fully integrate mental health assessment and management services, including screening, management of mental disorders, referral pathways and training, into all aspects of primary care, with an emphasis on TB, HIV and antenatal care services The strategic plan was to be coordinated at the district administrative level |

Service delivery |

| Miguel-Esponda et al. (2020) [69] | Compañeros En Salud (CES) mental health programme |

Assess the implementation of the CES programme to understand the extent of success in integrating mental health into PHC Determine strengths and limitations of the success or failure of integration To determine managers’ and providers’ perspectives on the programme Determine the key strengths and remaining challenges to the implementation of the CES mental health programme |

CES aims to strengthen the PHC system to improve access to quality healthcare The organization facilitates the delivery of general health services (including mental health) in 10 PHC clinics. For mental health, a coordinator oversees the delivery of mental health services and capacity-building activities and provides support for the management of complex cases All mental health services are delivered by medical doctors (MDs) Services are designed according to adapted clinical guidelines and include case identification, diagnosis, pharmacological treatments, individual and group talk-based interventions, and home visits |

Service delivery |

| Mkoka et al. (2014) [94] | Emergency obstetric care (EmOC) | Explore the experiences and perceptions of a council health management team (CHMT) in working with multiple partners while illuminating some governance aspects that affect implementation of EmOC at the district level | Strategy aims to strengthen all dispensaries and health centres through provision of basic EmOC (BEmOC) by strengthening the capacity of district hospital and upgrade by 50% health centres to provide comprehensive EmOC and strengthening health workers competencies | Service delivery |

| Moshiri et al. (2016) [95] | PHC |

Investigation of context, content, actors and process of PHC implementation Investigation of the referral system situation in Iran from 1982 to 1989 |

In order to tackle physician shortages, foreign doctors were being hired en masse to support PHS implementation | Service delivery |

| Mutabazi et al. (2020) [87] | PMTCT | Explore the perspective of experts and other key informants on the PMTCT integration into PHC | Strategy involving the integration of testing to reduce mother-to-child transmission during different phases of pregnancy | Service delivery |

| Muthathi et al. (2020) [96] | Ideal clinic realization and maintenance (ICRM) programme |

Generate knowledge on the policy implementation Examine the influence of motivation, cognition and perceived power of the policy actors and how it influenced ICRM implementation Explore policy coherence in the ICRM programme Explore the perceptions of stakeholders at the national, provincial and local government levels |

The goal of the ICRM programme is to prepare all PHC facilities to meet the quality standards set by the Office of Health Standards Compliance (OHSC) An ideal clinic is defined as a clinic with good infrastructure, adequate staff, adequate medicines and supplies, and good administrative processes, with sufficient bulk supplies; it uses applicable clinical policies, protocols and guidelines, and it harnesses partner and stakeholder support |

Health workforce |

| Pyone et al. (2017) [104] | Free maternity services (FMS) policy | Understand how the policy changed health system governance in Kenya and use the insights to inform policy implementation in Kenya and in other LMICs | FMS was part of a national strategy to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality, alleviate poverty and achieve the Millennium Development Goal targets; abolish user fees for all health services and dispensaries, and provide FMS in all levels of care of the government health sector | Financing |

| Rahman et al. (2020) [105] | Maternal, neonatal, child and adolescent health (MNC&AH) and community-based healthcare (CBHC), reproductive and adolescent health (MCR&AH) |

Understand key drivers for implementation of WHO recommendations for the case management of childhood pneumonia and possible serious bacterial infection (PSBI) with amoxicillin dispersible tablets (DT) Generate evidence to strengthen newborn and child health programmes in Bangladesh |

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) in Bangladesh provides healthcare services for childhood pneumonia and PSBI in the PHC setting through both the directorate of health services and directorate of family planning, under three operational plans Incorporate child-friendly amoxicillin DT for the case management of childhood pneumonia and PSBI when referral for oral amoxicillin is not feasible |

Service delivery |

| Roman et al. (2014) [66] | Malaria in pregnancy (MIP) |

Assess how three countries in Africa were able to achieve greater progress in MIP control Identify the practices and strategies that supported the success of the MIP programme Identify bottlenecks in MIP programme implementation processes Share lessons learned |

The MIP framework aims to prevent and control malaria during pregnancy by focusing on three methods that stabilize transmission: (1) intermittent preventative treatment with sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (SP) antimalarial drug; (2) use of physical insecticide nets; (3) effective case management based on signs and symptoms | Service delivery |

| Ryan et al. (2020) [109] | Comprehensive community mental health programme (CCMHP) | Aims to help inform the utilization of public–private partnerships (PPPs) for mental health policy implementation in Nigeria and other low-resource settings by documenting a promising example from Benue |

Two community-based rehabilitation facilities operate under CCMHP CCMHP procures medicines from CHAN Medi-Pharm and sets up Drug Revolving Fund at each health centre to ensure constant supply Referrals are made directly between the community psychiatric nurse (CPN) or community health extension worker (CHEW) and specialists at Federal Medical Centre Makurdi or Benue State University Teaching Hospital CPNs receive formal training, retraining and accreditation, funded by CCMHP CCMHP trains people as community-level mental health advocates for promotion, identification and referral. CPNs and CHEWs conduct community outreach for follow-up |

Service delivery |

| Saddi et al. (2018) [88] | Brazilian national programme for improving primary care access and quality (PMAQ) |

To determine frontline worker adherence to PMAQ and their perception of the impact of the programme Determine the relationship between the impact of the PMAQ as perceived by frontline workers and the way they evaluate the organizational capacity of the FHS at the front line |

This programme was adopted in 2011 to improve the quality and performance of PHC in Brazil, which is broadly known through its main policy: the FHS PMAQ objectives are (1) to promote quality and innovation in primary care management, strengthening self-assessment, monitoring and assessment, institutional support and permanent education processes; (2) to improve the use of information systems as a primary care management tool; (3) to institutionalize a primary care assessment and management culture; (4) to stimulate the focus of primary care on the service user, promoting management processes and transparency |

Service delivery |

| Sami et al. (2018) [102] | WHO standards for community- and health facility-based newborn care | Examines the feasibility of implementing a package of community- and facility-based neonatal interventions | WHO standards for community- and health facility-based newborn care prioritized the most critical services (neonatal interventions for reducing mortality) during a humanitarian crisis | Service delivery |

| Schneider and Nxumalo (2017) [97] | Ward-based outreach team (WBOT) strategy—adaptation for community health worker programme |

Understand the leadership and governance structure Assess the provincial experiences with adoption and implementation of the WBOT strategy |

Established set of proposals for the reorganization of community-based services | Leadership/governance |

| Sheikh et al. (2010) [98] | HIV testing policies | Investigate problems in the implementation of standardized public health practice guidelines from the perspective of the participant actors | Focused on the following aspects of the policy: (1) informed consent; (2) HIV testing as a precondition to preforming a medical procedure; (3) strict confidentiality | Health workforce |

| Shelley et al. (2016) [99] | National community health worker (NCHW) strategy |

Evaluate implementation process Determine barriers and facilitators Assess how evidence was used to guide ongoing implementation and scale-up decisions |

A strategy developed to recruit community health assistants for assistance with disease burden through a comprehensive PHC curriculum Strategy aimed to reduce maternal and child mortality by providing PHC services as close to the family as possible |

Health workforce |

| Stein et al. (2008) [106] | Practical Approach to Lung Health in South Africa (PALSA) PLUS programme |

Explore the value of PALSA PLUS guideline training approach from a PHC nurse perspective Evaluate the strategies used for adoption |

Health system-based approach to training for primary care providers with two components: (1) a comprehensive set of algorithm-based syndromic guidelines for PHC nurse clinical management of respiratory disease and HIV/AIDS; (2) a training programme to facilitate guideline implementation | Service delivery |

| Wingfield et al. (2015) [113] | CRESIPT: community randomized evaluation of a socioeconomic intervention to prevent TB |

Evaluate a socioeconomic intervention to support prevention and cure of TB in TB-affected households Describe the challenges of implementation, lessons learned and refinement of TB intervention |

The CRESIPT project aimed to evaluate a socioeconomic intervention (via cash transfers) to support prevention and cure of TB in TB-affected households and, ultimately, improve community TB control | Financing |

| Xia et al. (2015) [89] | PMTCT; prenatal HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B testing (PHSHT) | Examine the challenges and effectiveness of integrating PHSHT services | A priority strategy (promoted by WHO) involving the integration of services including testing to reduce mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) | Service delivery |

| Zakumumpa et al. [85] | ART scale-up | Explore how different health system components interact in influencing the sustainability of ART scale-up implementation | Provision of free antiretroviral drugs, workforce training in ART management, enhancing laboratory capacity and strengthening ART programme reporting | Access to essential medicine |

| Zhou et al. (2019) [67] | The mid- and long-term policy and development plan for mental health in Liuyang Municipality (Liuyang policy and Liuyang plan) |

Address the gap in China’s mental health policy literature with respect to local-level promotion and implementation Provide a deeper understanding of China’s problems and general lessons for implementing mental health policy at the local level |

The four main objectives of Liuyang policy and Liuyang plan include (1) establishing a leadership and coordination mechanism for mental health work; (2) constructing a three-level network of mental health services; (3) management and intervention for patients with psychosis (PWP); and (4) improving the public’s awareness and knowledge of mental health | Leadership/governance |

Service delivery was the health system building block most frequently targeted by the identified guidelines (n = 24). The remaining building blocks were targeted as follows, in descending order: health workforce (n = 5), financing (n = 4), access to essential medicine (n = 4), health information system (n = 2), and leadership and governance (n = 2).

Adaptation strategies

Only 14 articles explicitly reported on the concept of adaptation. Rarely did articles specifically comment on the strategies used to determine what and why adaptations were necessary. Those that reported how adaptations occurred often described any modifications as being suggested solutions to identified challenges during both pre- and post-implementation. Three articles also described a dedicated multidisciplinary working group aimed to gather feedback and identify required modifications. Six articles reported adaptations to be reactive in nature and another six reported them to be proactively planned. Modifications made were frequently reported as adding, tailoring or tweaking content elements, such as the addition of training sessions, expanding scope of practices and restructuring funding sources. None of the included articles reported using a guiding framework to help identify areas where adaptation could be beneficial and/or necessary. A full summary of the adaptation strategies and their related concepts according to the FRAME is given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Health system guideline/recommendation adaptation strategies (FRAME)

| Author | Adaptation strategies | Justification | When the modification occurred; was adaptation planned | Who participated in the decision to modify | What was modified; content of modification | Level of delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrade et al. (2017) [75] | Attention to chronic conditions model (ACCM) | Lack of resources | Not reported; planned proactive | Steps were conditioned for the ability of health professionals to understand the seven macro processes and their engagement based on available resources | The seven steps of the ACCM (they cut three of the steps to adapt to this health system); removing/skipping elements | Health professionals are the primary and secondary level of care |

| Armstrong et al. (2014) [90] | Maternal and perinatal death reviews (MPDR) system implementation | Adaptations based on challenges that were identified through a case review including lack of training | These are suggested solutions to challenges that were identified—may or may not have been put into practice; reactive | Determined these during an MPDR meeting | Training and evaluation—providing skills and education to maternity staff and women in the community, respectively; adding elements—training and education | Community (women) and clinic/unit level (maternity staff at hospital/reproductive and child health coordinator) |

| Bryce et al. (2005) [58] |

IMCI generic guidelines can be adapted by any country or area to reflect their specific epidemiological profile and health system characteristics WHO worked to develop guidelines for the country adaptation process, including evidence for intervention choices, models for how to incorporate additional diseases and conditions into the training materials, and how to conduct local studies to identify terminology and local foods Cadres of “IMCI adaptation consultants” were trained at regional and global levels |

Review of the guideline expectations | Pre-implementation and early implementation; proactive | Countries that implement this programme adapt it to fit their local context | Contextual—setting; tailoring to their local context | Target intervention group |

| Carneiro et al. (2018) [100] | The more physicians in Brazil programme (MPBP) has resulted in changes in the work processes of the Family Health Strategy (FHS), including changes to the management and control models used in the region | Municipalities experienced strong ascending trends in the number of prenatal consultations and lack of access to resources | Implementation; reactive | Ministry of Health (MoH) | Contextual—how treatment is delivered; tailoring/tweaking/refining—reorganization of the prenatal care | Target intervention group |

| Gueye et al. (2016) [108] |

Strategies were adapted to implement management of malaria programme Introducing new or adapting strategies, from insecticide rotation to lessen the risk of insecticide resistance, to an increase in parasitological screening in development areas to curtail the risk of transmission, to collaborations with the private sector |

None reported | Early implementation; reactive | Staff | Contextual; tailoring to local context | Organization |

| Halpern et al. (2010) [77] |

Adaptation of a standardized HIV patient monitoring system (PMS) WHO provided training on the HIV care and antiretroviral treatment (ART) PMS, and the technical working group adapted each component for Guyana System tools and functions were modified based on feedback from the training session participants, and a pilot PMS was subsequently implemented at one site |

None reported | Pre-implementation; planned/proactive | Technical working group | Contextual—patient chart data elements and functionality to PMS system; tailoring/tweaking, adding elements to patient chart | Clinic-unit level—HIV care ART |

| Kihembo et al. (2018) [57] |

Implement nationwide ISDR training to health facilities based on the revised guidelines developed Post-training support through integrated supervision |

Two challenges from the first implementation: Lack of funding resulted in a lack of resources and capacities at the operational level A need for a harmonized outbreak response and information flow at the district level |

Pre-implementation; planned | Ministry of health along with key partners | Aimed to enhance the capacity of districts to promptly detect, access and effectively respond to public health emergencies; adding elements—training | Health workforce all the way up to the operational national level |

| Leethongdee (2007) [83] | Government decided to fund the scheme by pooling the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) budgets for public hospitals, other health facilities, and Medical Welfare Scheme (MWS) and voluntary health card scheme and providing additional money | The initial plan met resistance from quarters such as the civil service and the labour unions | Pre-implementation; reactive | Civil service and labour unions rejected the initial plan, government then had to reassess | Implementation and scale-up activities; substituting the funding structures | Target intervention group |

| Mutabazi et al. (2020) [87] | Over the years, the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV/AIDS (PMTCT) guidelines have been adapted, but no strategies reported | None reported | None reported | None reported | None reported | None reported |

| Ryan et al. (2020) [109] |

Comprehensive community mental health programme (CCMHP) A scale-up initiative for the general mental health policy implementation in Nigeria through public–private partnership in healthcare delivery |

Absence of more clinical resources | Scale-up; reactive | None reported | Phone psychiatrists as needed; adding element | Community psychiatric nurses (CPNs) and community health extension worker (CHEWs) |

| Schneider and Nxumalo (2017) [97] | Re-engineering of primary healthcare (PHC) | To meet the needs and demands of each community health programme | Not reported; planned proactive | District managers, senior provincial managers, PHC facility managers, outreach team leaders, senior district official, subdistrict managers, PHC facility supervisors, professional nurses, environmental health officers |

Health posts vs PHC re-engineering Roles of nongovernmental organizations were redefined Change in the method of payment of CHW New curricula and training processes; tailoring leadership and governance changes |

Healthcare workers—specifically community-based workers |

| Stein et al. (2008) [106] |

Incorporating counselling skills into the Practical Approach to Lung Health in South Africa (PALSA) PLUS model Ongoing onsite training provides emotional support |

Given the limiting understanding of nurse counselling skills (i.e. they often threatened patients instead of making recommendation), nurses conceive counselling as “advice” that must be complied with rather than the patient feeling empowerment in decision-making | During the implementation of the PALSA PLUS programme and this evaluation; reactive | Not reported | Ongoing site training and counselling; adding elements—incorporation of a prayer into nurse-training sessions, as a means of accessing spiritual reserves for emotional support | Primary healthcare nurses |

| Wingfield et al. (2015) [113] |

Innovative socioeconomic intervention against TB (ISIAT) strategy was evaluated under the community randomized evaluation of a socioeconomic intervention to prevent TB (CRESIPT) project Regular steering meetings, focus group discussions and contact in the health posts |

Increase adherence and participation in the programme | Pre-implementation and implementation; proactive | Stakeholders + recipients | Contextual—increased the speed of bank transfers; substituting the funding structures | Target intervention group |

| Zakumumpa et al. [85] |

ART scale-up Nonphysician cadre were prescribing antiretroviral therapy |

The shortage of physician-level cadre was identified as a constraint | Scale-up; reactive | Individual practitioners | Implementation and scale-up activities; tweaking—nonphysician cadre were prescribing ART due to rapidly expanding patient volumes | Clinic/unit level, individual practitioner |

Implementation strategies

Eleven articles included in our review did not provide sufficient detail to adequately discern the strategies used to implement their health system guideline. 38 out of the 72 ERIC-defined implementation strategies were utilized across all 41 studies. A small number of reported implementation strategies were determined by consensus to fall under two separate ERIC categories and were coded as such. Studies reported a range of one to eight strategies to implement their health system initiative, with an average of four distinct implementation strategies. Conducting ongoing training was identified as the most frequent implementation strategy (n = 11), followed by building a coalition (n = 8), use of advisory boards and workgroups (n = 6), conducting educational meetings (n = 6) and developing educational materials (n = 5). The least prevalent ERIC-defined implementation strategies included, but were not limited to, revision of professional roles (n = 2), alterations of incentives/allowance structure (n = 2), assessments for readiness and identification of barriers and facilitators (n = 1), and tailoring of strategies (n = 1). A full breakdown of all 38 implementation strategies and their frequencies can be found in Table 4. None of our included studies explicitly reported the use of a theoretical/conceptual framework to guide their selection of implementation strategies.

Table 4.

Implementation strategies coded using the ERIC framework

| ERIC category | Occurrences | Implementation strategies (author/year) |

|---|---|---|

| Conduct ongoing training | 11 |

Conduct ongoing training (Ejeta et al. 2020 [107]; Lovero et al. 2019) [93] Training sessions (Xia et al. 2015) [89] Education and retraining (Callaghan-Koru et al. 2020) [86] Training (Kavle et al. 2018 [114]; Rahman et al. 2020 [105]) Clinical training (Sami et al. 2018) [102] Staff in primary care settings to receive training and supervision for basic mental health screening, diagnosis and treatment (Lovero et al. 2019) [93] Trained in key modules of WHO’s Mental Health Gap Action Programme Intervention Guide (Ryan et al. 2020) [109] Capacity-building of medical doctors (MDs) through high-intensity training and onsite supervision (Miguel-Esponda et al. 2020) [69] Develop and conduct tailored training for nurse midwives and clinical officers at dispensaries (Mkoka et al. 2014) [94] |

| Build a coalition | 8 |

Establishment of task teams, appointing leaders and NGO partnerships to lead and manage change (Schneider and Nxumalo 2017) [97] The programme proposal was presented and discussed with the staff. With the approval of the team, the process was gradually implemented (Bergerot et al. 2017) [79] Mutual promotion between national and local policies (Zhou et al. 2019) [67] Partnering with community associations (Lavôr et al. 2016) [111] Support for referrals to specialist services (Miguel-Esponda et al. 2020) [69] Collaboration and support from international development partners; national procurement planning and coordination (Rahman et al. 2020 [105]) Establish primary healthcare (PHC) network in one district of each province in the first year (Moshiri et al. 2016) [95] Integrated into curative health services provided by the national government (Gueye et al. 2016) [108] |

| Develop educational materials | 7 |

Develop educational materials (Ejeta et al. 2020 [107]; Andrade et al. 2017 [75]) Standardization of materials (Roman et al. 2014) [66] New training methods to create a more harmonized and educated workforce (Kihembo et al. 2018) [57] Written policy statement that is routinely communicated (Kavle et al. 2018) [114] Designed training materials (self-reading, teaching aids and videos) based on the principles of participatory learning (investigators of WHO Low Birth Weight [LBW] Feeding Study Group, 2016) [110] Treatment guidelines (Rahman et al. 2020) [105] |

| Use of advisory boards | 6 |

Stakeholder engagement (Roman et al. 2014) [66] Community groups and activist and healthcare professional acceptance and support; obtaining assistance from community health workers (Mutabazi et al. 2020) [87] Development of a chlorhexidine technical working group (Callaghan-Koru et al. 2020) [86] Promote collaboration between healthcare staff, support groups and local community; orientation of national policy- and decision-makers, management and community committees (Kavle et al. 2018) [114] Strategic planning workshops (Sami et al. 2018) [102] Elicited feedback on any site-specific concerns not addressed by the proposed system (Halpern et al. 2010) [77] |

| Conduct educational meetings | 6 |

Education to healthcare providers (Roman et al. 2014) [66] Health education sessions (Kavle et al. 2018) [114] A national training and feedback session (Halpern et al. 2010) [77] Participatory community meetings for information (Wingfield et al. 2015) [113] Conducting educational activities for adherence to directly observed therapy (DOT ; Lavôr et al. 2016) [111] Countries conducted orientation meetings (Bryce et al. 2005) [58] |

| Distribute educational material | 5 |

Distributed educational material (Ejeta et al. 2020) [107] Routinely distributed policy statement (Kavle et al. 2018) [114] Designed training materials (self-reading, teaching aids and videos) based on the principles of participatory learning (investigators of WHO LBW Feeding Study Group, 2016) [110] Printed educational materials for clinical decision-making (Miguel-Esponda et al. 2020) [69] Treatment guidelines (Rahman et al. 2020) [105] |

| Promote network-weaving | 5 |

Leading and managing change—establishment of task teams, appointing leaders and NGO partnerships (Schneider and Nxumalo 2017) [97] Collaboration between national reproductive health programmes and national malaria control programmes (Roman et al. 2014) [66] Coordination of Community Cadres within the health system (Shelley et al. 2016) [99] Multi-department participation and collaboration to better implement the national essential drugs policy (Li et al. 2015) [112] Targeted interactions of PHC designers with local actors shaped a wide network of friends before the implementation phase (Moshiri et al. 2016) [95] |

| Conduct educational outreach visits | 4 |

Education to healthcare providers (Roman et al. 2014) [66] Ongoing onsite training provides emotional support (Stein et al. 2008) [106] Monthly visits from a member of the working group to validate reports and address any implementation issues (Halpern et al. 2010) [77] Developed management and training capacity in a limited number of districts (Bryce et al. 2005) [58] |

| Access new funding | 4 |

Ensuring financial stability (Roman et al. 2014) [66] Financial guarantee from the central government (Zhou et al. 2019) [67] Distribution of amoxicillin by UNICEF (Rahman et al. 2020) [105] Programme financing (Miguel-Esponda et al. 2020) [69] |

| Stage implementation scale-up | 4 |

Implementation scale-up (Callaghan-Koru et al. 2020) [86] Pilot project was evaluated first; when it was deemed successful, the guideline was implemented at all existing care sites, one site at a time (Halpern et al. 2010) [77] End of one phase was marked with a review meeting with the objective of synthesizing early implementation experience and planning for expansion (Bryce et al. 2005) [58] Policies were implemented in a series of stages (Leethongdee, 2007) [83] |

| Develop and organize monitoring systems | 4 |

Surveillance system and performance and monitoring framework (Kihembo et al. 2018) [57] Programme monitoring (Kavle et al. 2018 [114]; Bryce et al. 2005) [58] Following each assessment, quality improvement plans are generated and provided to facility managers to guide their improvement actions (Muthathi et al. 2020) [96] |

| Develop resource-sharing agreements | 4 |

Management of resource availability; commodities/resources availability (Roman et al. 2014) [66] Distribution of medical commodities (Sami et al. 2018) [102] Ensuring medication supply (Miguel-Esponda et al. 2020) [69] Supply and distribution of amoxicillin dispersible tablets (Rahman et al. 2020) [105] |

| Provide clinical supervision | 4 |

Provide clinical supervision (Sami et al. 2018 [102]; Lovero et al. 2019 [93]) Staff in primary care settings to receive training and supervision (Lovero et al. 2019) [93] Capacity-building of MDs through high-intensity training and onsite supervision (Miguel-Esponda et al. 2020) [69] |

| Develop a formal implementation blueprint | 3 |

Five-year strategic plan with workplans (Kihembo et al. 2018) [57] Planning and early implementation, developed national strategy and plan (Bryce et al. 2005) [58] Network expansion plan; required budget was estimated and suggested to government; establish PHC network in one district of each province in the first year (Moshiri et al. 2016) [95] |

| Develop and implement tools for quality monitoring | 3 |

Develop and implement tools for quality monitoring (Ejeta et al. 2020) [107] Standardization of materials; performance assessments (indicators); monitoring and evaluating (Roman et al. 2014) [66] Monitoring through a health information system (Miguel-Esponda et al. 2020) [69] |

| Change physical structure and equipment | 3 |

Provide essential equipment and supplies; build/improve infrastructure for service delivery (Mkoka et al. 2014) [94] Availability of basic equipment (Rahman et al. 2020) [105] Providing containers to collect sputum and other inputs in the laboratory (Lavôr et al. 2016) [111] |

| Use train-the-trainer strategies | 2 | Train-the-trainer strategies (Ejeta et al. 2020 [107]; Kihembo et al. 2018) [57] |

| Recruit, designate and train for leadership | 2 |

Recruit, designate and train for leadership (Ditlopo et al. 2011) [91] Top-down supervision from the central government (Zhou et al. 2019) [67] |

| Promote adaptability | 2 |

Development and adaptation of guidelines to make them specific for low-income contexts (Callaghan-Koru et al. 2020) [86] Adapted the guidelines to their national context (Bryce et al. 2005) [58] |

| Alter incentive/allowance structures | 2 |

Conditional cash transfers to reduce TB vulnerability; incentivize and enable care (Wingfield et al. 2015) [113] Alter incentive/allowance structures (Ditlopo et al. 2011) [91] |

| Centralize technical assistance | 2 |