Abstract

In order to test our hypothesis that Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin Cry1Ca domain III functions as a determinant of specificity for Spodoptera exigua, regardless of the origins of domains I and II, we have constructed by cloning and in vivo recombination a collection of hybrid proteins containing domains I and II of various Cry1 toxins combined with domain III of Cry1Ca. Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac, Cry1Ba, Cry1Ea, and Cry1Fa all become more active against S. exigua when their domain III is replaced by (part of) that of Cry1Ca. This result shows that domain III of Cry1Ca is an important and versatile determinant of S. exigua specificity. The toxicity of the hybrids varied by a factor of 40, indicating that domain I and/or II modulate the activity as well. Cry1Da-Cry1Ca hybrids were an exception in that they were not significantly active against S. exigua or Manduca sexta, whereas both parental proteins were highly toxic. Incidentally, in a Cry1Ba-Cry1Ca hybrid, Cry1Ca domain III can also strongly increase toxicity for M. sexta.

Bacillus thuringiensis forms crystalline inclusions during sporulation which contain one or more insecticidal delta-endotoxins or Cry proteins (21). The members of the cry gene family encode proteins which show homology in the primary sequence and probably have similar three-dimensional structures. Nonetheless, Cry proteins show a great deal of host specificity, with each protein being toxic for only one or a few insect species. Specificity is determined to a large extent, although not entirely, by the interaction of the gut protease-activated toxin with receptors on the target insect gut epithelial cells (23, 24). Following binding to such a receptor, a toxin can insert into the epithelial cell membranes and form pores, eventually killing the insect.

The three-dimensional structures of three members of the Cry family, which may well prove to be representative of all Cry proteins, reveal the presence of three structural domains (13, 18, 19a). The N-terminal domain, domain I, consists of seven alpha helices and is probably partially or entirely inserted into the target cell membrane. Domain II consists of three beta sheets in a so-called Greek key conformation. This domain is assumed to interact with receptors, thereby contributing to toxin specificity. Indeed, there is much evidence implicating domain II residues in specific toxicity and in high-affinity binding (8, 21).

The C-terminal domain, domain III, which consists of two beta sheets in a jellyroll conformation, has also been implicated in determining specificity. Swapping domain III between toxins, such as by in vivo recombination between the encoding genes, can result in changes in specific activity (3, 10, 12, 19). Binding experiments with such hybrids have shown that domain III is involved in binding to putative receptors of target insects, suggesting that domain III may exert its role in specificity through receptor recognition (1, 10, 11, 17). Most notably, domain III of Cry1Ac has been shown to be involved in binding to the putative receptor in the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta, which is an aminopeptidase N (6, 9).

We have shown previously that substitution of domain III of toxins which are not active or are only weakly active against the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua, such as Cry1Ea and Cry1Ab, with domain III of Cry1Ca, which is active, can produce hybrid toxins that are active against this insect (3, 10). These results identified domain III of Cry1Ca as a major determinant of specificity for S. exigua. So far this observation has been made for two different parental toxins (Cry1Ea and Cry1Ab), suggesting that domain III of Cry1Ca may function in toxicity against S. exigua regardless of the origin of domains I and II. To test this hypothesis, we have used a combination of cloning and in vivo recombination to make an extended collection of hybrids of Cry1 toxins with (part of) domain III of Cry1Ca. Our results show that several, but not all, Cry1 toxins become more toxic to S. exigua when their domain III is replaced by that of Cry1Ca. Moreover, a similar effect was incidentally observed for M. sexta.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Construction of plasmid pRM8, encoding Cry1Ab-Cry1Ca hybrid H04, and of plasmid pHK13, encoding Cry1Ac-Cry1Ca hybrid H130, has been described before (9, 10). All wild-type protoxins were cloned in an Escherichia coli expression vector based on pBD10, a derivative of pKK233-2 (3). All clones contain full-length protoxin-encoding genes with an NcoI site at the start. pBD140, containing cry1Ab, pBD150, containing cry1Ca, and pBD160, containing cry1Ea, have been described before (3, 4). For production of Cry1Ac, an NcoI-KpnI (bases 1 to 2174) fragment of cry1Ab in pBD140 was replaced with the corresponding fragment of cry1Ac (bases 1 to 2177), resulting in cry1Ac expression vector pB03. For production of Cry1Ba, an NcoI-BstXI (bases 1 to 1974) fragment of cry1Ca in pBD150 was replaced with the corresponding fragment of cry1Ba (bases 1 to 2037), resulting in cry1Ba expression vector pMH19. For production of Cry1Da, the EcoNI site at the end of the cry1Da gene (position 3487) was used to modify the 3′ end and to create a BglII site, using a synthetic EcoNI-BglII linker; the NcoI-BglII fragment encompassing the whole gene was cloned into the NcoI-BglII vector fragment of pBD10, resulting in Cry1Da expression vector pMH15. For production of Cry1Fa, a DraI-KpnI (bases 44 to 2153) fragment of cry1Ea in pBD160 was replaced with the corresponding fragment of cry1Fa, resulting in Cry1Fa expression vector pMH21.

pMH23, containing a cry1Fa-cry1Ca hybrid gene, was constructed by replacing the NcoI-SacI fragment of cry1Ab (bases 1 to 1348) present in hybrid H04 expressing plasmid pRM8 with the corresponding fragment of cry1Fa (bases 1 to 1327).

Tandem plasmids and in vivo recombination.

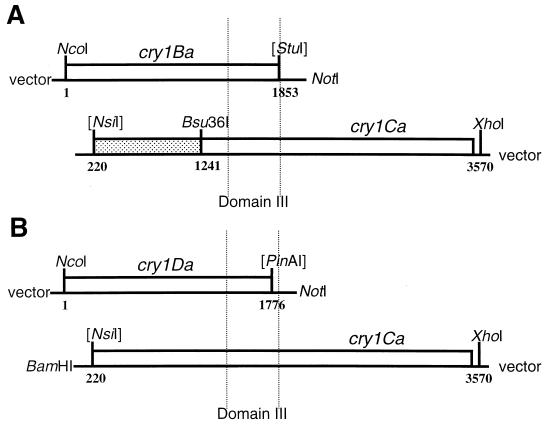

cry1Ba-cry1Ca tandem plasmid pMH22 (Fig. 1A) was made by replacing the NcoI-SacII fragment containing cry1Ea in cry1Ea-cry1Ca tandem plasmid pBD650 (3) with a corresponding NcoI-StuI (bases 1 to 1853) fragment of cry1Ba and a synthetic StuI-SacII linker fragment. E. coli strain JM101 (recA+) was transformed with pMH22, and plasmid DNA was purified. To select for recombinant plasmids, the DNA was digested with NotI and Bsu361, which have unique sites in the polylinker region between the cry1Ba and cry1Ca parts and in cry1Ca (position 1241), respectively (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of tandem plasmids and in vivo recombination strategy. Locations of domain III borders are indicated by dotted vertical lines. For clarity, the overlapping regions of the two involved genes are aligned vertically, and the polylinker between the two genes is shown as cut by NotI (A) or by NotI and BamHI (B). (A) cry1Ba-cry1Ca tandem plasmid pMH22. Since recombinants were selected by cutting with NotI and Bsu36I, recombination within the dotted area of cry1Ca was not found. (B) cry1Da-cry1Ca tandem plasmid pMH18.

cry1Da-cry1Ca tandem plasmid pMH18 was made by replacing the NcoI-BglII fragment containing cry1Ea in pBD650 (see above) with a corresponding NcoI-PinAI (bases 1 to 1776) fragment of cry1Da and a synthetic PinAI-BglII linker fragment (Fig. 1B). E. coli strain JM101 was transformed with pMH18, and plasmid DNA was purified. To select for recombinant plasmids, the DNA was digested with NotI and BamHI, which have unique sites in the polylinker region between the cry1Da and cry1Ca parts (Fig. 1B).

For both recombination experiments, digested DNA was transformed into E. coli strain XL-1, and transformants were screened for the production of soluble protoxin as described earlier (10). Restriction analysis and DNA sequencing determined the locations of crossover points in hybrids.

Toxin production, purification, and bioassays.

All protoxins were produced in E. coli strain XL-1. Protoxin isolation, trypsin treatment, and fast protein liquid chromatography purification of activated toxin were performed as described earlier (3). The toxicity of proteins was tested by spreading activated toxin dilutions on an artificial diet. Since trypsin digestion may inactivate Cry1Ba and its derivatives (see below), Cry1Ba and the Cry1Ba-Cry1Ca hybrids were also tested as protoxins. Neonate larvae of S. exigua were used, and mortality was scored after 6 days at 28°C. For M. sexta bioassays, 1-day-old larvae were used, and mortality was scored after 6 days at 28°C. The concentration causing 50% mortality (LC50) and its 95% fiducial limits were determined by probit analysis of results from three or more independent experiments with the POLO PC program (20).

RESULTS

Cry1Ac-Cry1Ca hybrid.

Cry1Ac-Cry1Ca hybrid H130 (Fig. 2) was constructed for an earlier study through replacement of the Cry1Ab domain I- and II-encoding parts of the H04 cry1Ab-cry1Ca hybrid gene with the corresponding fragment of the cry1Ac gene (11). While the parental toxin Cry1Ac has no significant activity against S. exigua, hybrid H130 is active. Yet, although this toxin differs from H04 in only six amino acids, because domains I and II of Cry1Ab and Cry1Ac are very homologous, H130 was approximately 3.5 times less toxic to S. exigua than H04 and comparable in toxicity to the parental toxin Cry1Ca (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

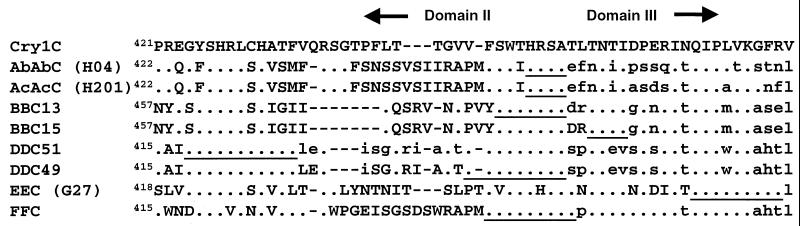

Amino acid alignment of Cry1Ca and its domain III hybrids in the area of the border between domains II and III. Amino acid identity to Cry1Ca is represented by dots. The homologous area that contains the crossover is underlined for each hybrid. For the hybrids, the parental toxin sequence is shown in lowercase beyond the crossover site.

TABLE 1.

Toxicities of wild-type and hybrid proteins for S. exigua and M. sexta

| Toxin or hybrid | Reference or source | LC50 (95% fiducial limits) fora:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| S. exigua | M. sexta | ||

| Cry1Ca | 55 (39–73) | 155 (94–152) | |

| Cry1Ab | This study | 601 (214–1,014) | NDb |

| AbAbC (H04) | 10 | 23 (17–30) | ND |

| Cry1Ac | >2,000 | ND | |

| AcAcC (H130) | This study | 80 (54–104) | ND |

| Cry1Bab | >8,000 | >1000 | |

| BBC13b | This study | >8,000 | 85 (85–115) |

| BBC15b | This study | 968 (642–1,240) | 128 (101–156) |

| Cry1Da | 111 (78–147) | <25 | |

| DDC49 | This study | >8,000 | >1,000 |

| DDC51 | This study | >8,000 | >1,000 |

| Cry1Fa | 219 (158–290) | ND | |

| FFC1 | This study | 40 (28–57) | ND |

Toxicity is indicated as LC50 (in nanograms per square centimeter). ND, not determined.

Tested as a protoxin.

Cry1Ba-Cry1Ca hybrids.

In order to produce Cry1Ba-Cry1Ca hybrids, we constructed the cry1Ba-cry1Ca tandem plasmid pMH22, which contains the toxin-encoding part of the cry1Ba gene (bases 1 to 1853), followed by a polylinker and most of the cry1Ca gene (bases 220 to 3570) (Fig. 1A). Recombination in this plasmid was selected for by digestion with NotI and Bsu361, which have unique sites in the polylinker and in the cry1Ca gene at position 1242, respectively. By choosing Bsu361, which cuts in the 3′ end of the domain II-encoding part of the cry1Ca gene, we could effectively select for recombination events behind this position, i.e., in or close to domain III. Digested DNA was retransformed into E. coli XL-1. Restriction analysis of transformants confirmed that most of them represented a recombination event in the targeted area. Of the 13 recombinants initially screened, 5 produced a soluble protoxin. Sequencing subsequently showed that those recombinants had an identical crossover site at the approximate border between domain II and domain III. Only one of them, BBC13 (Fig. 2), was selected for toxicity studies. Restriction analysis of another 24 recombinants identified 1 recombinant with a crossover close to but different from the crossover in BBC13. This recombinant, BBC15 (Fig. 2), also produced a soluble protoxin and was therefor selected for toxicity studies. Crossovers further into the domain III-encoding region were also observed but resulted in no soluble protoxin.

Trypsin treatment of Cry1Ba and Cry1Ba-Cry1Ca hybrid toxins resulted in the production of a stable product of only approximately 55 kDa, as opposed to the expected size of approximately 65 kDa for an activated toxin. A 65-kDa intermediary product was frequently observed during trypsin treatment but could not be purified in large quantities as a stable product. The purified 55-kDa protein fractions from Cry1Ba and the Cry1Ba-Cry1Ca hybrids showed no or little toxicity to either S. exigua or M. sexta. Since the lack of activity of Cry1Ba and the Cry1Ba-Cry1Ca hybrids BBC13 and BBC15 could be due to processing in domain I inactivating them (14), the toxins were retested as protoxins (Table 1). Cry1Ba protoxin had no significant activity against both insects, but hybrids BBC13 and BBC15 showed very different activities against S. exigua. BBC13 protoxin, which has the entire domain III from Cry1Ca (Fig. 2), had no significant activity. Surprisingly, BBC15 protoxin, which has a more C-terminal crossover point and thus less Cry1Ca sequence, did have significant activity against S. exigua, although it was still about 18-fold less toxic than Cry1Ca toxin on a weight-for-weight basis. Additionally, both BBC13 and BBC15 protoxins had higher activities than the parental toxin Cry1Ba against M. sexta, with their toxicities being comparable to that of the parental toxin Cry1Ca.

Cry1Da-Cry1Ca hybrids.

For construction of Cry1Da-Cry1Ca hybrids, we made a cry1Da-cry1Ca tandem plasmid, pMH18 (Fig. 1B), which contains the toxin-encoding part of cry1Da, followed by a polylinker and most of the cry1Ca gene (bases 220 to 3570). Recombination in this plasmid was selected for by digestion with NotI and BamHI, which have unique sites in the polylinker, and retransformation of E. coli XL-1. Restriction analysis of plasmids from transformants confirmed that most of them (>95%) represented recombination events, with crossover sites throughout the overlap between the two genes. Small-scale screening of 17 recombinants showed that 12 formed a soluble protoxin; 9 of the 12 yielded a stable toxin upon activation by trypsin. Restriction analysis showed that six of the nine stable-toxin-producing recombinants had a crossover site in or close to the domain I-encoding region. Therefore, these were not studied further. The three other recombinants were sequenced and were shown to have one of two different crossover sites at or just in front of the border between domains II and III (Fig. 2). Two recombinants, DDC49 and DDC51, having the two different crossover sites were selected for toxicity studies. Both produced stable toxins upon activation by trypsin and were purified. Surprisingly, although both parental toxins, Cry1Ca and Cry1Da, are active against S. exigua as well as against M. sexta, both Cry1Da-Cry1Ca hybrid toxins showed no significant activity against those insects (Table 1).

Cry1Fa-Cry1Ca hybrid.

A Cry1Fa-Cry1Ca domain III hybrid was constructed by replacing the domain I- and II-encoding fragment of the H04 cry1Ab-cry1Ca hybrid gene with the homologous fragment of cry1Fa. This procedure resulted in a hybrid gene encoding protoxin FFC1, containing domains I and II from Cry1Fa and domain III from Cry1Ca. Trypsin-activated toxin FFC1 was tested for activity against S. exigua and found to be 5.5 times more toxic than its parental toxin Cry1Fa; this toxicity level was comparable to that of its other parental toxin, Cry1Ca.

DISCUSSION

The study of the biological properties of Cry protein hybrids is a helpful tool in understanding how the interaction between the different toxin domains determines insect specificity. Results from such studies not only give insight into the mode of action of Cry proteins but can also result in hybrid toxins with possible applications in agriculture. As this study shows, domain III of Cry1Ca is capable of forming biologically active hybrids with domains I and II of various Cry1 toxins. The increased toxicity for S. exigua of most of these hybrids, compared to that of the parental toxin from which domains I and II are derived, clearly shows the importance of domain III for activity against this insect. However, the variation in activity levels of the different hybrids also clearly indicates a role of domain I and/or domain II in determining specific toxicity. Thus, the LC50s of the hybrids described in this study (not including the inactive hybrids BBC13, DDC49, and DDC51) vary by a factor of 40 or more.

Whereas Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac, Cry1Ba, Cry1Ea, and Cry1Fa all form biologically active hybrids with domain III of Cry1Ca, Cry1Da is a surprising exception. While both Cry1Ca and Cry1Da are active against S. exigua, their hybrids, DDC49 and DDC51, are not. In this study, we tested all S. exigua-inactive hybrids on M. sexta as well, in order to establish whether such hybrids have any biological activity. The Cry1Da-Cry1Ca hybrids also have no activity against M. sexta, while the parental toxins are active. Apparently, the toxicity of a hybrid toxin cannot be fully accurately predicted from the activities of the parental toxins. Since the nature of the interaction between domains I and II and domain III is still unknown, it is not clear why Cry1Da and Cry1Ca together form inactive hybrids. One might speculate that these specific combinations are incompatible with proper protein folding, which would be necessary for their biological function. Although this notion would explain why only a limited number of crossovers usually results in trypsin-stable toxins, as described in this study, it is a less likely explanation for the inactivity of the Cry1Da-Cry1Ca hybrids. Both hybrids appeared to be fully stable after activation by trypsin. Moreover, they retained activity against the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (unpublished results). This finding may well fit with data from other studies of hybrid toxicity for P. xylostella. In those studies, the toxicity and binding properties of hybrids were comparable to those of the parental toxins from which domains I and II were derived, and substitution of domain III appeared to have little effect as far as the studied combinations were concerned (2, 22). The suggestion of these data that domain III plays little or no role in specificity for P. xylostella would explain why the DDC hybrids retained their activity against this insect.

Cry1Ba shows no activity against S. exigua and M. sexta, either as a toxin or as a protoxin. Cry1Ba and the hybrids derived from its domains I and II show processing by trypsin leading to a smaller-than-expected stable toxin. This result is probably due to trypsin cleavage within domain I, between alpha helices 3 and 4, as reported earlier for Cry1B as well as for Cry3A (7). In contrast to its neutral effect on activity of Cry3A against coleopterans (7), trypsinization of Cry1Ba was shown to reduce its activity against lepidopterans (5, 14). Therefore, Cry1Ba and its hybrids were retested as protoxins, yielding different results. Of the two isolated Cry1Ba-Cry1Ca hybrids, only BBC15 has some, although low, activity against S. exigua. This hybrid differs in only two amino acids from the inactive hybrid BBC13 but contains less of domain III of Cry1Ca. Apparently, this small change in crossover site drastically changes toxicity for S. exigua. Unexpectedly, both Cry1Ba-Cry1Ca hybrids were at least as active against M. sexta as the parental toxin Cry1Ca. Since the hybrids were tested as protoxins, on a molar basis they would be more toxic than Cry1Ca. These results show that in certain combinations, domain III of Cry1Ca can be a determinant for M. sexta toxicity as well, although Cry1Ca toxicity for M. sexta has generally been found to be lower than that of Cry1Ab and Cry1Ac (K. van Frankenhuyzen and C. Nystrom, the Bacillus thuringiensis toxin specificity database [http://www.glfc.forestry.ca/Bacillus/Bt_HomePage/netintro99.htm]).

Cry1Fa has considerable activity against S. exigua yet becomes more toxic with domain III of Cry1Ca. This hybrid has a toxicity level comparable to that of Cry1Ca and to that of hybrids of Cry1Ca with Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac, and Cry1Ea.

There is a growing amount of evidence for an important role of domain III in insect specificity through its role in binding of the toxin to insect gut receptors. Most of this evidence comes from studies of Cry1Ac binding, where domain III is responsible for the recognition of an N-acetylgalactosamine moiety on the receptor (6, 9, 16, 17). With S. exigua brush border membrane vesicles, we found that the replacement of domain III of Cry1E with that of Cry1C increases binding affinity (unpublished results). It is not always clear what the respective roles of domains II and III in binding and toxicity are, how important they are relative to each other in every insect, and if and how they may interact in binding to a common receptor. An interesting hypothesis put forward recently (15) suggests that the binding of Cry1Ac to its Lymantria dispar receptor aminopeptidase N may be a two-step reaction in which both domain II and domain III are involved. The first step would be mediated by domain III and would be a rapid, rate-limiting step for the overall binding reaction; domain II would mediate the second step. Following this line of thinking, one could hypothesize that for many Cry1 toxins, activity against S. exigua is limited by their respective third domains mediating an inefficient (slow) first step of binding, a problem that is (often) alleviated by domain III of Cry1Ca. Although in such a case it might be considered surprising that such a variety of second domains is functional in conjuction with Cry1Ca domain III, at the same time it could explain part of the variation in toxicity of the hybrids studied here. Binding of domains II and III to a common receptor might require a particular sterical conformation of these domains relative to each other, a condition that might not be met in the inactive Cry1Da-Cry1Ca hybrids. Confirmation of this hypothesis would require extensive study of different (purified) receptor-toxin interactions and the three-dimensional structure of toxin-receptor complexes.

In conclusion, domain III of Cry1Ca is an important, but not universal, determinant for specific activity against S. exigua. In vivo recombination is a powerful method for exploring the variety in crossover sites that will give a soluble, trypsin-stable toxin, which differs for different Cry1-Cry1Ca combinations (Fig. 2). Moreover, subtly different hybrids with very different activities may be found (BBC13 versus BBC15). Although solubility and stability may be good indicators for potential biological activity, predicting specificity remains somewhat elusive. Cry1Ca domain III hybrids may be biologically active against another insect, such as M. sexta (BBC13) or P. xylostella (BBC13, DDC49, and DDC51), without being active against S. exigua. In order to understand these phenomena, study of the function of domain III at the molecular level and how it is affected by its context (domains I and II) is essential. A collection of different hybrid toxins, such as those described here, may prove to be a useful tool for such study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The technical assistance of Petra Bakker and Bert Schipper is greatly appreciated. We are also grateful to Ine Derksen (Department of Virology, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands) for supplying us with S. exigua eggs and to S. Reynolds and A. Meredith (University of Bath, Bath, United Kingdom) for supplying us with M. sexta eggs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson A I, Wu D, Zhang C. Mutagenesis of specificity and toxicity regions of a Bacillus thuringiensis protoxin gene. J Biol Chem. 1995;177:4059–4065. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4059-4065.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballester V, Granero F, de Maagd R A, Bosch D, Mensua J L, Ferré J. Role of Bacillus thuringiensis toxin domains in toxicity and receptor binding in the diamondback moth. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1900–1903. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1900-1903.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosch D, Schipper B, van der Kleij H, de Maagd R, Stiekema W. Recombinant Bacillus thuringiensis crystal proteins with new properties: possibilities for resistance management. Bio/Technology. 1994;12:915–918. doi: 10.1038/nbt0994-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosch D, Visser B, Stiekema W. Analysis of non-active engineered Bacillus thruringiensis crystal proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;118:129–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley D, Harkey M A, Kim M K, Biever K D, Bauer L S. The insecticidal Cry1B crystal protein of Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. thuringiensis has dual specificity to Coleopteran and Lepidopteran larvae. J Invertebr Pathol. 1995;65:162–173. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1995.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton S L, Ellar D J, Li J, Derbyshire D J. N-Acetylgalactosamine on the putative insect receptor aminopeptidase N is recognised by a site on the domain III lectin-like fold of a Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxin. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:1011–1022. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll J, Convents D, Vandamme J, Boets A, van Rie J, Ellar D J. Intramolecular proteolytic cleavage of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry3A delta-endotoxin may facilitate its coleopteran toxicity. J Invertebr Pathol. 1997;70:41–49. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1997.4656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean D H, Rajamohan F, Lee M K, Wu S J, Chen X J, Alcantara E, Hussain S R. Probing the mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal proteins by site directed mutagenesis: a minireview. Gene. 1996;179:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00442-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Maagd R A, Bakker P L, Masson L, Adang M J, Sangadala S, Stiekema W, Bosch D. Domain III of the Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin Cry1Ac is involved in binding to Manduca sexta brush border membranes and to its purified aminopeptidase N. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:463–471. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Maagd R A, Kwa M S G, van der Klei H, Yamamoto T, Schipper B, Vlak J M, Stiekema W J, Bosch D. Domain III substitution in Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin Cry1A(b) results in superior toxicity for Spodoptera exigua and altered membrane protein recognition. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1537–1543. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.5.1537-1543.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Maagd R A, van der Klei H, Bakker P L, Stiekema W J, Bosch D. Different domains of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxins can bind to insect midgut membrane proteins on ligand blots. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2753–2757. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.2753-2757.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ge A Z, Rivers D, Milne R, Dean D H. Functional domains of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal crystal proteins. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17954–17958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grochulski P, Masson L, Borisova S, Pusztai-Carey M, Schwartz J L, Brousseau R, Cygler M. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A(a) insecticidal toxin—crystal structure and channel formation. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:447–464. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Höfte H, van Rie J, Jansens S, Houtven A V, Vanderbruggen H, Vaeck M. Monoclonal antibody analysis and insecticidal spectrum of three types of lepidoptera-specific insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2010–2017. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.2010-2017.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins J, Dean D. The binding mechanism of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin to Lymantria dispar APN. In: Ziniu Y, Ming S, Zidua L, editors. Proceedings of the 3rd Pacific Rim Conference on Biotechnology of Bacillus thuringiensis, Wuhan. Beijing, China: Science Press; 1999. p. 268. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee M K, You T H, Gould F L, Dean D H. Identification of residues in domain III of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin that affect binding and toxicity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4513–4520. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4513-4520.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee M K, Young B A, Dean D H. Domain III exchanges of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A toxins affect binding to different gypsy moth midgut receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;216:306–312. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Carroll J, Ellar D J. Crystal structure of insecticidal delta-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature. 1991;353:815–821. doi: 10.1038/353815a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masson L, Mazza A, Gringorten L, Baines D, Aneliunas V, Brousseau R. Specificity domain localization of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxins is highly dependent on the bioassay system. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:851–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Morse R J, Powell G, Ramalingam V, Yamamoto T, Stroud R M. Crystal structure of Cry2Aa from Bacillus thuringiensis at 2.2 Ångstroms: structural basis of dual specificity. In: Lizuka T, editor. Proceedings of the VIIth International Colloquium on Invertebrate Pathology and Microbial Control and IVth International Conference on Bacillus thuringiensis. Japan: Sapporo; 1998. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russel R M, Robertson J L, Savin N E. POLO: a new computer program for probit analysis. ESA Bull. 1977;23:209–213. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnepf E, Crickmore N, van Rie J, Lereclus D, Baum J, Feitelson J, Zeigler D R, Dean D H. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:775–806. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.775-806.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabashnik B E, Malvar T, Liu Y B, Finson N, Borthakur D, Shin B S, Park S H, Masson L, de Maagd R A, Bosch D. Cross-resistance of the diamondback moth indicates altered interactions with domain II of Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2839–2844. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.2839-2844.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Rie J, Jansens S, Höfte H, Degheele D, van Mellaert H. Receptors on the brush border membrane of the insect midgut as determinants of the specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1378–1385. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1378-1385.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Rie J, Jansens S, Höfte H, Degheele D, van Mellaert H. Specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin. Eur J Biochem. 1989;186:239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]