Abstract

Rationale:

While teachers are heralded as key drivers of student learning outcomes, little attention has been paid to teachers’ mental health, especially in less-developed countries such as Ghana. Professional background, workplace environment, and personal life stressors may threaten teachers’ mental health and subsequent effectiveness in the classroom.

Objectives:

The objectives of this study were to investigate 1) whether and how professional background, workplace environment, and personal life stressors predicted teachers’ anxiety and depressive symptoms, and 2) whether participation in a professional development intervention predicted change in teachers’ symptoms over the course of one school year in Ghana.

Method:

We used multilevel models to examine predictors of depressive and anxiety symptoms among 444 kindergarten teachers (98% female; age range: 18–69) who participated in the Quality Preschool for Ghana (QP4G) Study. QP4G was a school-randomized control trial (n = 108 public schools; n = 132 private schools) evaluating a one-year teacher professional development intervention program implemented with and without parental-awareness meetings. Teacher depressive and anxiety symptoms were assessed at baseline before the intervention and at the end of the school year.

Results:

Poor workplace environment was associated with increased anxiety and depressive symptoms. Social support also predicted symptoms, with lack of support from students’ parents and being new to the local community associated with more anxiety symptoms. Within teachers’ personal lives, household food insecurity predicted more depressive symptoms. Finally, anxiety and depressive symptoms increased for all teachers over the school year. However, randomization to either intervention was linked to a significantly smaller increase in symptoms over the school year.

Conclusions:

Results suggest that teachers’ personal and professional lives are consequential for their mental health, and that professional development interventions that provide training and in-class coaching and parent engagement may benefit teachers’ mental health.

Keywords: Health impact assessment, Teachers, Mental health, Material hardship, Social support, Ghana, sub-Saharan Africa

1. Introduction

Teaching is a highly demanding profession, with teachers regularly reporting worse mental health than individuals in other professions (McLean et al., 2017). Studying the mental health of educators is therefore important not only for informing efforts to support teachers, but also because poor teacher mental health has been linked to worse student learning outcomes (Beilock et al., 2010; Harding et al., 2019; McLean and Connor, 2015; Sandilos et al., 2015). Although recent studies have examined teachers’ mental health in Western high-income countries, virtually no attention has been paid to the mental health of teachers in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as Ghana.

Ghana has emerged as a leader in early childhood education (ECE) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with recent education reforms resulting in an impressive increase in the gross enrollment rate in pre-primary schools from 56% in 2007 to 95% in 2014 (UNESCO, 2015). While this education reform undoubtedly represents positive change, it has also brought notable workplace challenges for Ghana’s teachers. The rapid expansion of the ECE workforce has left little time for adequate preparation, with the majority (nearly 70%) of teachers struggling to implement new curriculum without any formal training (Aheto-Tsegah, 2011). Such workplace hardship is often coupled with lack of support from administrators and parents, as well as personal life stressors, such as food insecurity, that may harm teachers’ mental health (Schwartz et al., 2019).

Recent studies have examined workplace and personal life predictors of teachers’ mental health in high-income countries (e.g., McLean et al., 2017; Jeon et al., 2018), but gaps in the literature remain. First, practically no studies have examined the mental health of teachers in LMICs such as Ghana. This lack of research is problematic because education reforms in recent decades in LMICs have led to additional personal and professional hardships for teachers that may threaten their mental health and subsequent effectiveness in the classroom. Second, teacher professional development (TPD) interventions to improve children’s learning outcomes have become the focus of many LMICs, including Ghana. Although these TPD interventions theoretically provide support to teachers, it is unknown whether or how they may influence teachers’ mental health.

To address these gaps, we used data from the Quality Preschool for Ghana Study (QP4G) randomized controlled trial to examine whether and how teachers’ professional background, workplace environment, and personal life stressors predicted depressive and anxiety symptoms, and whether exposure to a TPD intervention predicted changes in these symptoms over the course of one school year. Our results can inform efforts to support teachers’ mental health, with the hope that better teacher mental health will contribute to higher quality education and child development in LMICs.

2. Background

2.1. Teacher mental health

The social-ecological framework for occupational health underscores the link between workplace conditions and worker health (Grzywacz and Fuqua, 2000; Landsbergis et al., 2014). Exposure to workplace stressors such as excessive job demands have been shown to negatively influence workers’ mental health (LaMontagne et al., 2014; Landsbergis et al., 2014). Moreover, there is evidence of “spillover” and “crossover” between workplace and family domains, which emphasizes the need to consider the separate and joint influences of work and personal life stress on health (Grzywacz and Fuqua, 2000; Landsbergis et al., 2014). Though the job stress literature has expanded in recent decades, it does not specifically focus on mental health in the teaching profession. Mounting evidence from the field of education suggests that mental health is considerably worse among teachers (Jeon et al., 2018; Kidger et al., 2016; Whitaker et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2019). For example, Whitaker et al. (2015) found that 25% of U.S. Head Start teachers in their survey reported clinically significant levels of depression. Taken together, findings from the field of education suggest that there is merit in applying the social-ecological framework for occupation research to the mental health of educators.

2.2. Predictors of teachers’ mental health

Teachers’ professional background characteristics, workplace environments, and personal life stressors may shape their mental health. Although studies have explored the influence of teachers’ professional background (i.e., years of teaching experience) on classroom practices and child outcomes (e.g., Kelley and Camilli, 2007), less is known about whether professional characteristics are related to teachers’ mental health. Experienced teachers may have developed useful coping strategies for managing the challenges of teaching (Friedman-Krauss et al., 2014). Furthermore, as described in the job stress literature, the workplace environment is crucial to employees’ mental health. A positive workplace environment is essential in education settings because it promotes teachers’ well-being, and teachers, in turn, set the tone for the classroom environment (Kidger et al., 2016; McLean et al., 2020). Studies have found that perceived negative work conditions predicted more depressive symptoms among ECE teachers (Jeon et al., 2018), as well as worse mental health over time (Hindman and Bustamante, 2019). Importantly, the workplace environment encompasses social support (or lack thereof) from administrators and parents. Teachers may feel distressed when parents do not communicate with them or engage with their child’s education (Roberts et al., 2019). Finally, less attention has been paid to stress in teachers’ personal lives. Low wages and working multiple jobs have been linked to a higher risk of depression among ECE teachers in the United States (McLean et al., 2020; Roberts et al., 2019). Personal life stressors may be especially important for the mental health of teachers in LMICs because hardships, such as food insecurity and poverty, are more frequent and severe in LMICs compared to high-income countries (Atuoye and Luginaah, 2017; Yang et al., 2019).

2.3. Teacher mental health in Ghana

As is the case in many other LMICs, mental health in Ghana has emerged as a major public health issue. Depression alone is projected to be the third leading cause of disease burden in LMICs by 2030 (Mathers and Loncar, 2006). Many challenges exist in addressing mental health in LMICs, including a lack of culturally-sensitive treatments for mental health disorders and few mental health laws to direct services (Rathod et al., 2017). Although Ghana’s government passed the Mental Health Act in 2012 in an effort to integrate mental health care into the national public Ghana Health Service (Republic of Ghana, 2012), there remains little research about the prevalence of mental health conditions. To the best of our knowledge, Sipsma et al. (2013) is the only empirical study on mental health in Ghana that uses nationally representative data. Their study found that 20% of the adult population reported moderate or severe psychological distress. Recent evidence from the Women’s Health Study of Accra revealed that women aged 35 to 54 were 1.95 times more likely to be depressed compared to women aged 18 to 24, underscoring the risk of depression among working-age women (Bonful and Anum, 2019). There exists limited knowledge regarding the reasons for poor mental health in Ghana, but studies have highlighted economic hardship (Bonful and Anum, 2019) and food insecurity (Atuoye and Luginaah, 2017) as contributing factors. Thus, a small but growing body of evidence suggests that mental health is an important public health issue in Ghana.

Ghana is considered a leader in ECE in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), making it a unique context for examining teachers’ mental health (UNESCO, 2015). In 2008, the government added two years of pre-primary education to the country’s free universal basic education, resulting in the gross enrollment rate in pre-primary schools increasing from 56% in 2007 to 95% in 2014 (Ghana Education Service, 2012; Ghana Ministry of Education, 2014). Due to the rapid expansion of pre-primary education, however, the majority of the ECE teacher workforce struggles to implement new curriculum without adequate training, basic classroom supplies, or support from administrators and parents (Aheto-Tsegah, 2011; Schwartz et al., 2019). Such workplace stress is often coupled with low and infrequent remuneration, forcing many teachers to find other part-time jobs to supplement their salaries (Osei, 2006). Overall, Ghana’s teachers face personal and professional risks that may not only harm their mental health, but also hinder the ongoing development of the country’s teacher workforce.

2.4. Teacher professional development programs

Teacher professional development (TPD) interventions to improve children’s learning outcomes have become the focus of many countries in SSA (Sandefur, 2016). TPD programs refer to approaches for improving teaching practice, with success defined by whether programs improve student learning outcomes (Seidman et al., 2018). A recent meta-analysis of studies in SSA found that TPD programs that successfully transformed teachers’ instructional techniques in the classroom had an effect size approximately 0.30 standard deviations greater on student learning outcomes than all other types of programs combined (Conn, 2017). It remains unknown whether TPD programs, which theoretically provide support to teachers, may mitigate or aggravate teachers’ mental health. On the one hand, TPD programs may worsen teachers’ mental health due to the added stress of implementing new teaching techniques and undergoing assessments by program evaluators (e.g., Klassen and Chiu, 2011). On the other hand, TPD programs may improve teachers’ mental health through providing additional in-person support (e.g., through in-classroom coaching, parent engagement) and helping them learn effective teaching practices (Kennedy, 2016).

2.5. The Quality Preschool for Ghana study

Given the rapid expansion in the demand for kindergarten in Ghana, a large number of teachers entered the profession with inadequate training (Ghana Education Service, 2012). The Quality Preschool for Ghana (QP4G) project aimed to build capacity and support for implementation of the 2004 kindergarten (KG) curriculum (Republic of Ghana, 2004) and to enhance the quality of KG education. The goals of QP4G were (a) to develop and rigorously evaluate a teacher training program and (b) to test the benefits of engaging parents via an awareness campaign designed to align parental expectations with the KG curriculum. This school-randomized controlled trial assessed the impact of a teacher training intervention program on teachers’ instructing practices and children’s developmental outcomes (see Wolf et al., 2019 for more details).

The teacher-training program (TT treatment condition) included training workshops and in-classroom coaching. The training workshops were administered for five days in September, two days in January, and one day in May. The workshops were led by professional teacher trainers from the National Nursery Teacher Training Center, which is a teacher-training facility affiliated with the Ghana Ministry of Education that provides ECE certification courses for teachers. The context of these workshops focused on integrating play- and activity-based, child-centered teaching practices into the teaching of instructional content. The first half of each training day consisted of lectures and discussions, while the second half focused on practicing the techniques learned and creating materials to implement activities in the classroom.

The in-classroom coaching visits occurred two times per term (six total visits over the school year) and were administered by district government ECE coordinators. These ECE coordinators attended the teacher training workshops in addition to their own two days of training on their roles as monitors and coaches. They were trained on the same content as the teachers, as well as on their role in guiding teachers and answering teachers’ questions about implementing the curriculum. At each visit, teachers were observed for a minimum of one hour, followed by debriefing sessions where teachers reflected on their practices and were provided with feedback on their performances and areas for improvement.

The parental-awareness meetings consisted of three meetings administered through school parent–teacher associations (PTAs) over the school year and offered to all parents with kindergarten children. The meetings were implemented at the school and administered by the same district-government ECE coordinators who conducted the in-class teacher coaching. At each meeting, the ECE coordinators screened a video developed for the intervention and led a discussion about the key messages with the parents. The ECE coordinators received instructions for how to guide the discussions. The video themes were (a) the importance of play-based learning, (b) parents’ role in children’s learning, and (c) encouraging parent–teacher and parent–school communication. The videos and discussions aimed to increase parental involvement at home and in school, and to enhance communication between parents and teachers.

2.6. The present study

Wolf et al. (2019) examined impacts of the QP4G teacher professional development intervention on classroom quality and child outcomes. In the present study, we extend the work of Wolf et al. (2019) to focus on the mental health of the teachers who participated in this study. Specifically, we examined (a) whether and how teachers’ personal, professional, and workplace environments predicted their depressive and anxiety symptoms, and (b) whether participation in the TPD program predicted change in depressive and anxiety symptoms over the course of one school year.

3. Method

3.1. Sample

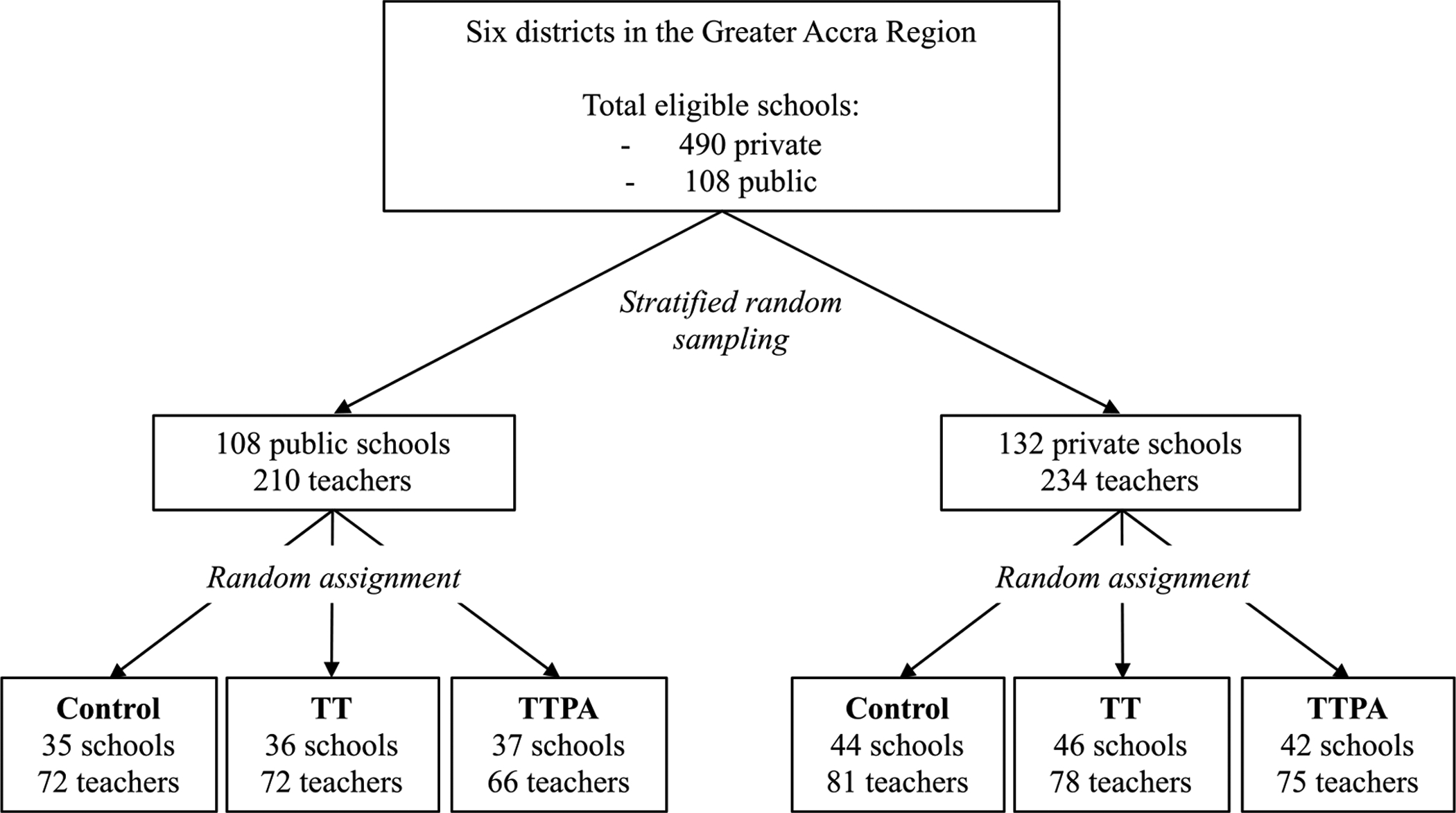

All schools in the six districts were identified using the Ghana Education Service Educational Management Information System Database. Eligible schools had to be registered with the government and have at least one kindergarten (KG) class. Additionally, schools with the necessary qualifications were randomly sampled within each district and by public and private school. Every public school was sampled (N = 108) and private schools (490 total) were sampled within districts in proportion to the total number of private schools in each district relative to the total for all districts (N = 132).

All KG teachers in selected schools were invited to participate in the training. The majority of schools had two KG teachers, though the possible range was from one to five. If there were more than two KG teachers in the school, two teachers were randomly sampled per school for the evaluation. Thirty-six schools had only one KG teacher, and in these cases the one teacher was sampled. Of the 444 teachers who were recruited for the study at baseline in September 2015, 348 remained in the study for follow-up in June 2016. Teachers were missing from follow-up for various reasons, including switching to teach a different grade level, moving into a school administrative position, or leaving the teaching profession. Fig. 1 depicts the sampling and randomization process.

Fig. 1.

Sampling at baseline and randomization of schools. Notes. TT = Teacher training condition; TTPA = Teacher training plus parent awareness meetings condition. Total sample includes 240 schools and 444 teachers.

3.2. Randomization

The implementation and first-year evaluation of the intervention occurred between September 2015 and June 2016. In this cluster randomized control trial, 240 schools were randomly assigned to one of two treatment arms or the control group: (a) TT condition, 82 schools; (b) TTPA condition, 79 schools; and (c) control group, 79 schools. The trial was preregistered in the American Economic Associations’ registry for randomized controlled trials (RCT ID: AEARCTR-0000704). Randomization was stratified by district and sector (private and public). Six of the 16 districts in the Greater Accra region were selected. These districts were rated as the most disadvantaged in the 2014 Ghana District League Table (a social accountability index that ranks regions and districts based on development and delivery of key basic services; UNICEF, 2015) that were within a two hour drive from Accra, the capital city where the training took place.

3.3. Ethical approval and consent

The project was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Innovations for Poverty Action (#1328; “Quality Preschool for Ghana”), the University of Pennsylvania (#825679; “Quality Preschool for Ghana”), and New York University (#FY2015–10; “An Intervention to Improve Preschool Quality in Peri-urban Ghana”). Given the support of the district and national governments for the project, all public schools were required to participate in the study. Private schools were not required to participate, but only three refused participation when sampled for the study. Importantly, no individual was required to participate in any data collection, and informed consent was sought for all individuals who participated in the surveys.

3.4. Procedure

The school year in Ghana begins in September and ends in July. All data in the present study were collected in September 2015 (baseline) and June 2016 (follow-up). The TPD intervention was implemented throughout the 2015–2016 school year and began in October 2015 after baseline data collection. All data were collected by the Ghana office of Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA), a research and policy nonprofit that brings together researchers and decision-makers to design, rigorously evaluate, and refine solutions and their applications. All surveys were administered within the schools by IPA enumerators who were blinded to the treatment status of the schools. Teachers received a small token for their time participating in the surveys (the equivalent of ~ $1.50 in phone credit).

All items were pilot tested before the baseline assessment. First, five cognitive interviews (Willis et al., 2005) were conducted with teachers to assess whether they understood the questions consistently across subjects and in the ways intended (Collins, 2003). We then piloted the survey by administering it to 20 teachers through one-on-one surveys. From both of these exercises, we concluded that these items were suitable for use in this sample. All items had been used in previous research with teachers in SSA (e.g., Wolf et al., 2015).

All questionnaires for teachers were conducted in English, which is the language of the education system in Ghana. Within our sample, 90% of the teachers assessed their level of English as “proficient” or “intermediate,” while the remaining 10% described their level as “basic.” Therefore, key phrases for each survey item were also translated into the three most common local languages in the region to aid teachers in interpreting the items when necessary. All enumerators were Ghanaian and spoke at least one local language.

3.5. Power analysis

A sample size of 160 schools (for two-way comparisons) with two teachers per school was assumed. With 80% power at the 5% significance level, and assuming an intraclass correlation (ICC) of 0.10 for teacher outcomes, effect sizes as small as 0.33 can be detected.

3.6. Measures

Teacher mental health was evaluated using the Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Questionnaires (Goldberg et al., 1988), which have been validated and used in other countries in SSA (De Rouvray et al., 2014; Nubukpo et al., 2004; Rafael et al., 2010). Depressive symptoms were evaluated using nine items about how the respondent felt in the past month, such as “How often during the past month have you felt you have lost interest in your usual activities?” Anxiety symptoms were also evaluated using nine items, such as “How often during the past month have you been having difficulty relaxing?” Potential responses for both sets of items were “Never,” “Rarely,” “Sometimes,” “Very Often,” and “Always.” Participants’ total scores were averaged across items, and these mean scores were used in the analyses, with higher scores indicating greater depressive or anxiety symptoms. Within this sample, Cronbach’s alpha estimates showed adequate reliability for both depressive (α = 0.71 and 0.70 at baseline and follow-up, respectively) and anxiety symptoms (α = 0.78 and 0.79 at baseline and follow-up). We kept these two scores as continuous because specific cut-points for mental health symptomology may vary within LMICs (Patel, 2017).

Professional background characteristics included educational attainment, years of teaching experience, and ECE training. Educational attainment included categories for below senior secondary, post-secondary/diploma, and bachelor’s degree or higher. Years of teaching experience was a continuous variable. Whether teachers had ECE training was a dichotomous variable (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Workplace environment measures included lack of parental support, poor objective work conditions, and the number of “big problems” at the school. These measures were chosen based on research highlighting the unique set of workplace challenges facing teachers in SSA (Schwartz et al., 2019; Wolf et al., 2015). Participants were asked seven questions about how much their pupils’ parents support their work as a teacher, such as “How much do parents support your work as a teacher by visiting school to talk to you about their concerns for their children?” Response categories were “not at all,” “very little,” “sometimes,” “a fair amount,” and “quite a lot.” These responses were reverse coded and summed such that higher scores indicated less parental support (α = 0.83). Objective work conditions were measured using a summed scale of seven items: being a temporary worker, being responsible for 36 or more students, sometimes receiving pay late, working for pay outside of the teaching job, having a salary level less than 100 Ghanaian Cedi per month (~$19 USD), working more than 37 hours per week in school, and working more than 10 hours per week outside of school. Higher scores indicated worse objective work conditions. The development of this scale was based on research from the Democratic Republic of Congo (Wolf et al., 2015). Participants were asked seven questions about problems at their respective schools; examples of these issues included “classes are taught by poorly trained teachers” and “school lacks financial resources to create a good environment for teachers and children.” For each of these problems, participants could choose to describe it as “not a problem,” a “little problem,” or a “big problem.” The “big problem” responses were coded as 1 and all other responses were coded as 0, and then summed and top-coded at 3 or more big problems within the school.

Personal life stressors included household poverty risk, being new to the local community, and household food insecurity. Household poverty risk was assessed using the poverty scorecard for Ghana (Schreiner, 2015), which takes into account household size, if school-aged children are in the household, literacy of the male household head, type of construction material used for the home, type of toilet, main source of fuel, and material goods owned. All scores were coded such that higher scores indicated more household poverty (range 1–100) and then a cut-point of 60+ was applied. Households at or above this cut-point are at a “high risk of poverty” based on Ghana’s household poverty line (Schreiner, 2015). The “new to the local community” stressor was assessed by the question: “Were you living at your current community/town before you began teaching at this school?” “No” responses were coded as 1 and “yes” responses were coded as 0. Teachers do not choose their teaching placement in Ghana, but rather are placed by the government based on areas of need (Schwartz et al., 2019). Therefore, this measure attempts to capture whether teachers have the social support that comes from being connected to the community where they are employed. Participants were classified as living in food insecure households if they answered yes to least one of three questions about food in the past month, including whether there was ever no food in the house, whether a household member went to sleep hungry, and whether a household member went a whole day and night without eating anything because there was not enough food.

Treatment status was operationalized with an indicator for whether teachers were sampled from a school that was randomly assigned to the control group (Control), teacher training and coaching program (TT condition), or teacher training and coaching program plus parental awareness meetings (TTPA condition).

Additional covariates from baseline included teacher age, teacher sex (female = 1), whether the school is public or private (private = 1), KG level (KG1, KG2, or combined KG class), and the district in which the school is located (Adenta, Ga Central, Ga East, Ga South, La Nkwantanang-Madina, or Ledzokuku-Krowor).

3.7. Missing data imputation

Multiple imputation (with Stata’s “ice” command) was used to address missing data. Although the data were not missing completely at random (MCAR), if variables that strongly predict attrition are incorporated into the missing data strategy, the plausibility of a missing at random (MAR) assumption increases (Young and Johnson, 2015). The assumptions of MAR have been shown to be robust when including a large set of covariates in estimating multiple chains of models, including those that predict differential attrition. This imputation approach meets the standards of the What Works Clearinghouse Version 4.0 Standards Handbook (Clearinghouse, 2017). We imputed 20 teacher-level datasets using teacher demographic and background variables, outcome scores for professional well-being and classroom quality, and treatment status indicators. All models were estimated using these 20 datasets (using Stata’s “mi estimate” command).

3.8. Statistical analysis

Baseline equivalency across school and teacher characteristics was established and is described in detail in Wolf et al. (2019). The results confirmed that randomization successfully yielded three treatment groups equivalent on observable characteristics.

Frequencies for all variables were first examined by treatment condition. Descriptive statistics are presented at baseline for all variables, and for baseline and follow-up for depressive and anxiety symptoms. Correlations among the independent variables were small (all r < 0.21). Diagnostic tests revealed no issues with multi-collinearity.

After examining the means and standard deviations for all study variables, we estimated a series of multilevel regression models where two observations of anxiety and depressive symptoms were nested within teachers. We modeled depressive and anxiety symptoms at baseline, and change in depressive and anxiety symptoms between baseline and follow-up. We interacted each independent variable of interest with a dichotomous variable for time (0 = baseline, 1 = follow-up) to examine change in symptoms over the school year. Therefore, we tried to limit the bias caused by the single source of data by examining how stressors reported at baseline predicted future mental health outcomes. Anxiety and depressive symptoms were allowed to vary across participants (i.e., random intercept), but all slopes were fixed because random slopes cannot be estimated without a third wave of mental health data. Intraclass correlations for each outcome revealed that a very small portion of variance was explained by the school level (range = 0.035–0.052). Therefore, the inclusion of the school-level nesting in the models was not needed. We used the vce-cluster method to cluster robust standard errors by school. This method relaxes the independence assumption of errors within designated group membership, accounting for the small correlation within schools.

For each outcome, we estimated a series of four models where we examined whether the independent variables predicted baseline symptoms and changes in symptoms over the school year. Therefore, each model shows two coefficients for each independent variable: the estimated effect of the independent variable on symptoms at baseline and the estimated effect on the change in symptoms over time. All models controlled for treatment group, age, sex, KG level taught, whether school is private or public, and district. Model 1 examined teachers’ professional background characteristics, Model 2 examined the workplace environment measures, and Model 3 examined the personal life stressor measures. Model 4 included all three sets of independent variables and controls. This modeling strategy allowed us to examine how personal and professional challenges separately and jointly predicted anxiety and depressive symptoms. Model 4 also included an interaction between time and the treatment. We focused on analyzing the effect of the intervention on change in symptoms over time because baseline anxiety and depressive symptoms were assessed before the intervention was implemented.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

As shown in Table 1, anxiety and depressive symptoms increased, on average, for all teachers between baseline and follow-up. Nearly 50% of the teachers had below senior secondary schooling. Teachers had an average of seven years of teaching experience, and more than half had some ECE training. The average scores on the lack of parental support scale were slightly above the midpoint of possible scores. The average scores for the poor objective work conditions scale were below the midpoint of possible scores. About 10% of teachers reported three or more major problems in their respective schools. Nearly 10% lived in foodinsecure households, and 12% were new to the local community where they were teaching. About 13% of the teachers were living in households that were at a high risk of poverty.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of respondents in the study sample by treatment condition (N = 444).

| Control | TT Condition | TTPA Condition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 142) | (N = 154) | (N = 148) | |

| % or M (SD) | % or M (SD) | % or M (SD) | |

| Mental health | |||

| Depressive symptoms | |||

| Baseline | 1.92 (0.52) | 1.96 (0.55) | 2.01 (0.54) |

| Follow-up | 2.13 (0.56) | 2.01 (0.57) | 2.08 (0.53) |

| Anxiety symptoms | |||

| Baseline | 2.04 (0.61) | 2.08 (0.64) | 2.10 (0.75) |

| Follow-up | 2.33 (0.70) | 2.12 (0.71) | 2.22 (0.69) |

| Personal life stressors | |||

| Household is food insecure | 9.86 | 10.39 | 7.43 |

| New to local community | 12.68 | 13.93 | 12.16 |

| Household at risk of poverty | 13.38 | 10.39 | 13.51 |

| Professional background | |||

| Education | |||

| Below senior secondary | 44.37 | 41.56 | 48.65 |

| Post-secondary/diploma | 35.21 | 33.77 | 34.46 |

| BA or higher | 20.42 | 24.68 | 16.89 |

| Years of teaching experience | 6.60 (6.80) | 6.16 (6.41) | 6.60 (6.80) |

| Has ECE experience | 66.20 | 72.08 | 63.51 |

| Workplace environment | |||

| Lack of parental support | 3.13 (0.90) | 3.07 (0.80) | 3.03 (0.86) |

| Poor objective work conditions | 2.09 (1.21) | 2.11 (1.19) | 1.99 (1.13) |

| Major problems at school | |||

| 0 | 35.21 | 44.16 | 46.62 |

| 1 | 38.73 | 37.66 | 28.38 |

| 2 | 12.68 | 10.39 | 16.89 |

| 3+ | 13.38 | 7.79 | 8.11 |

| Teacher personal characteristics | |||

| Age | 38.55 (10.82) | 35.98 (10.95) | 35.94 (10.98) |

| Female | 99.00 | 97.66 | 96.67 |

| School characteristics | |||

| Private school | 52.11 | 52.60 | 52.70 |

| Public school | 47.89 | 47.40 | 47.30 |

| District of school | |||

| Adenta | 11.97 | 16.88 | 12.84 |

| Ga Central | 12.68 | 12.99 | 12.84 |

| Ga East | 17.61 | 16.23 | 12.84 |

| Ga South | 23.24 | 22.73 | 27.03 |

| La Nkwantanang-Madina | 13.38 | 9.09 | 10.81 |

| Ledzokuku-Krowor | 21.13 | 22.08 | 23.65 |

Notes. All covariates are held at baseline values except depressive and anxiety symptoms. M = Mean; SD = Standard deviation; ECE = early childhood education; TT = teacher training group; TTPA = teacher training plus parental awareness meetings group.

4.2. Predictors of teacher mental health

Our first aim was to examine whether and how teachers’ personal, professional, and workplace environments predicted both their depressive and anxiety symptoms at baseline and any change in those symptoms over the school year. Table 2 shows the results of the multilevel models for anxiety symptoms at baseline and change over time. Table 3 shows the same set of models for depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Multilevel models predicting anxiety symptoms at baseline and change over the school year (N = 444).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | |

| baseline | change | baseline | change | baseline | change | baseline | change | |

| Professional background | ||||||||

| Education (ref: below senior secondary) | ||||||||

| Post-secondary/diploma | 0.07 (0.09) | −0.05 (0.08) | 0.09 (0.09) | −0.03 (0.09) | ||||

| BA or higher | 0.06 (0.11) | −0.02 (0.09) | 0.09 (0.10) | 0.02 (0.11) | ||||

| Years of teaching experience | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01)+ | −0.01 (0.01) | ||||

| Has ECE experience | −0.08 (0.08) | −0.02 (0.08) | −0.06 (0.07) | −0.02 (0.08) | ||||

| Workplace environment | ||||||||

| Lack of parental support | 0.12 (0.04)*** | −0.08 (0.05) | 0.10 (0.04)*** | −0.08 (0.05) | ||||

| Poor objective work conditions | 0.06 (0.03)+ | −0.02 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.04) | ||||

| Problems at school (ref: none) | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.01 (0.09) | 0.05 (0.08) | 0.01 (0.08) | ||||

| 2 | 0.23 (0.10)* | 0.07 (0.13) | 0.23 (0.10)* | 0.07 (0.13) | ||||

| 3+ | 0.42 (0.12)** | −0.14 (0.14) | 0.41 (0.11)*** | −0.16 (0.13) | ||||

| Personal life stressors | ||||||||

| New to local community | 0.16 (0.09)+ | 0.05 (0.12) | 0.19 (0.09)* | 0.03 (0.12) | ||||

| Household at risk of poverty | 0.15 (0.09) | −0.02 (0.12) | 0.13 (0.08) | −0.03 (0.12) | ||||

| Household is food insecure | 0.41 (0.12)*** | −0.16 (0.13) | 0.37 (0.11)*** | −0.14 (0.13) | ||||

| Treatment × Time (ref: Control) | ||||||||

| TT × Time | −0.26 (0.09)*** | |||||||

| TTPA × Time | −0.19 (0.09)* | |||||||

| Constant | 2.20 (0.23)*** | 1.70 (0.25)*** | 2.24 (0.22)*** | 1.41 (0.28)*** | ||||

| Time (school year) | 0.22 (0.08)*** | 0.42 (0.16)*** | 0.17 (0.05)*** | 0.65 (0.19)*** | ||||

| Random effects parameters | ||||||||

| sd (constant) | 0.43 (0.03)*** | 0.42 (0.03)*** | 0.42 (0.03)*** | 0.40 (0.03)*** | ||||

| sd (residual) | 0.52 (0.02)*** | 0.52 (0.02)*** | 0.51 (0.02)*** | 0.51 (0.02)*** | ||||

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Notes. N = 444; ECE = early-childhood education experience; TT = teacher training group; TTPA = teacher training plus parental awareness meetings group; all models control for treatment group, teacher age, sex, whether the school is public or private, and school district.

Table 3.

Multilevel models predicting depressive symptoms at baseline and change over the school year (N = 444).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | |

| baseline | change | baseline | change | baseline | change | baseline | change | |

| Professional background | ||||||||

| Education (ref: below senior secondary) | ||||||||

| Post-secondary/diploma | 0.02 (0.07) | −0.04 (0.07) | 0.01 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.07) | ||||

| BA or higher | −0.03 (0.09) | 0.10 (0.08) | −0.03 (0.08) | 0.12 (0.08) | ||||

| Years of teaching experience | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | ||||

| Has ECE experience | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.07) | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.07) | ||||

| Workplace environment | ||||||||

| Lack of parental support | 0.05 (0.03)+ | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.03) | ||||

| Poor objective work conditions | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.03) | ||||

| Problems at school (ref: none) | ||||||||

| 1 | −0.01 (0.06) | 0.10 (0.07) | −0.01 (0.06) | 0.08 (0.07) | ||||

| 2 | 0.26 (0.09)*** | −0.11 (0.09) | 0.27 (0.09)*** | −0.11 (0.09) | ||||

| 3+ | 0.28 (0.09)*** | −0.07 (0.11) | 0.29 (0.08)*** | −0.09 (0.10) | ||||

| Personal life stressors | ||||||||

| New to local community | 0.20 (0.08)* | 0.02 (0.11) | 0.24 (0.08)*** | −0.03 (0.11) | ||||

| Household at risk of poverty | 0.19 (0.07)* | −0.16 (0.10) | 0.17 (0.07)* | −0.16 (0.09) | ||||

| Household is food insecure | 0.25 (0.08)*** | −0.13 (0.09) | 0.22 (0.08)*** | −0.12 (0.09) | ||||

| Treatment × Time (ref: Control) | ||||||||

| TT × Time | −0.19 (0.07)*** | |||||||

| TTPA × Time | −0.13 (0.07)+ | |||||||

| Constant | 1.99 (0.19)*** | 1.82 (0.20)*** | 1.94 (0.17)*** | 1.61 (0.22)*** | ||||

| Time (school year) | 0.14 (0.07)* | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.14 (0.04)*** | 0.19 (0.15) | ||||

| Random effects parameters | ||||||||

| sd (constant) | 0.34 (0.02)*** | 0.33 (0.03)*** | 0.33 (0.03)*** | 0.32 (0.05)*** | ||||

| sd (residual) | 0.41 (0.02)*** | 0.41 (0.02)*** | 0.41 (0.02)*** | 0.40 (0.02)*** | ||||

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Notes. N = 444; ECE = early childhood education; TT = teacher training group; TTPA = teacher training plus parental awareness meetings group; all models control for treatment group, teacher age, sex, whether the school is public or private, and school district.

According to the time coefficients for Model 1, both anxiety (b = 0.22, p < 0.001) and depressive symptoms (b = 0.14, p = 0.046) increased, on average, for all teachers over the course of the school year. Model 1 for both anxiety and depressive symptoms showed that none of the teacher professional background characteristics were associated with baseline symptoms nor change in symptoms over time. Regarding the workplace environment, Model 2 revealed that lack of parental support was associated with more anxiety (b = 0.12, p = 0.002), but not depressive symptoms at baseline. Three or more major problems at the school was associated with higher anxiety (b = 0.42, p = 0.001), with this coefficient corresponding to a roughly 0.5 standard deviation increase in anxiety symptoms compared to no major problems at the school. Similarly, three or more major problems at the school was associated with about a 0.5 standard deviation increase (b = 0.28, p < 0.001) in depressive symptoms at baseline. None of the workplace environment variables predicted change in anxiety or depressive symptoms over the school year.

Model 3 examined the predictive power of personal life stressors. Being new to the local community (b = 0.20, p = 0.14), living in a household at high risk of poverty (b = 0.19, p = 0.011), and household food insecurity (b = 0.25, p = 0.004) were all associated with more depressive symptoms at baseline, with the magnitudes of these coefficients corresponding to roughly a one-third standard deviation increase in symptoms. In contrast, Model 3 for anxiety showed a significant association only between household food insecurity and increased symptoms at baseline (b = 0.41, p < 0.001). This effect size was notable, corresponding to roughly a half standard deviation increase in anxiety symptoms. Once again, none of the personal life stressors predicted change in anxiety or depressive symptoms over time. In Model 4, which included all predictors, lack of parental support, three or more major problems at the school, and household food insecurity all remained significant predictors of anxiety symptoms. There was also evidence of a suppression effect, as being new to the local community was associated with increased baseline anxiety (b = 0.19, p = 0.031) after including the professional and workplace environment measures. However, the magnitude of this coefficient was only half the size of the coefficient for food insecurity, suggesting that food insecurity had a much larger association with depressive symptoms than did being new to the community. In Model 4 for depressive symptoms, three or more major problems in the school and the three personal life stressors all remained significant predictors of baseline symptoms.

4.3. The impact of the TPD intervention

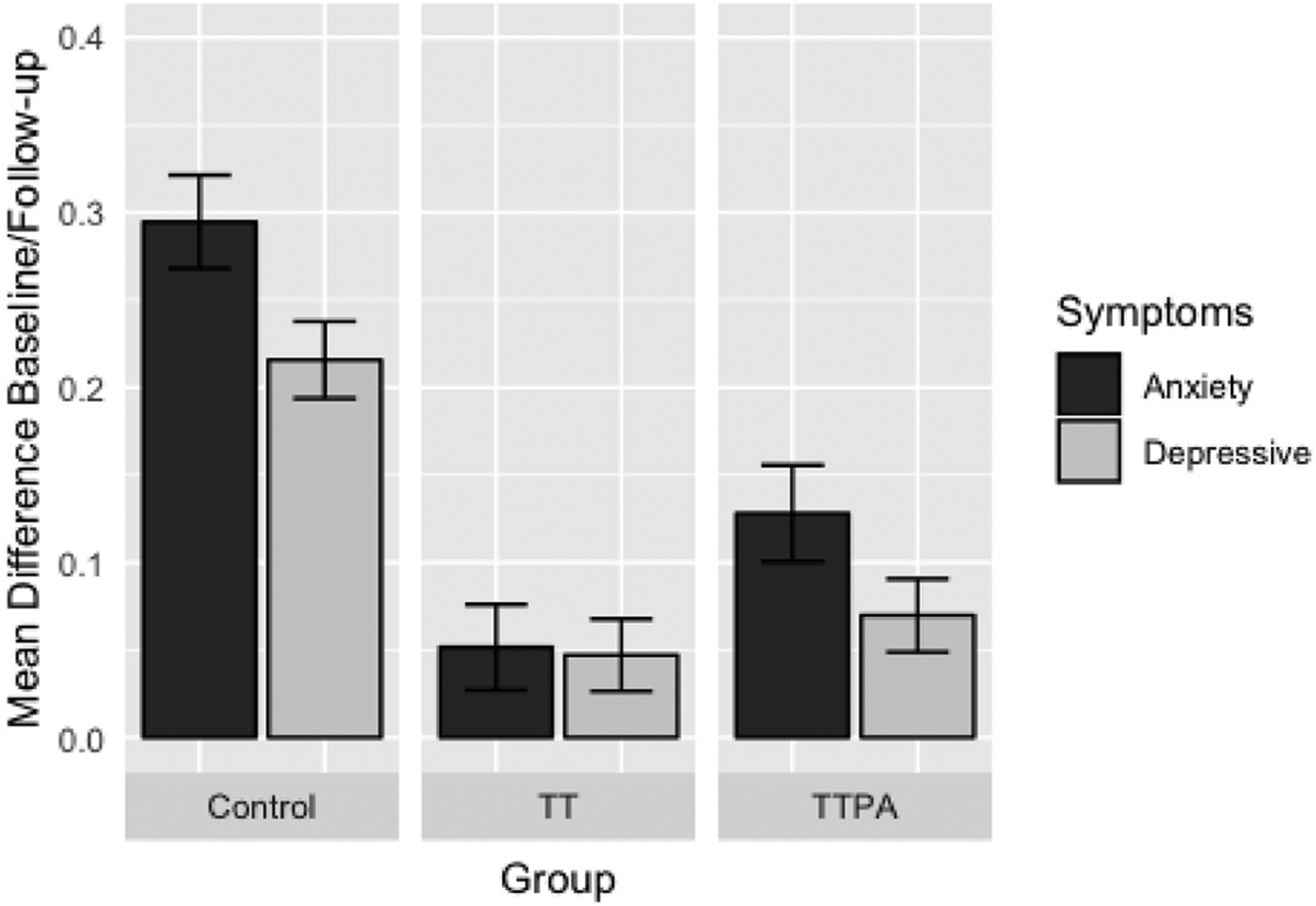

Our second aim was to examine whether either of the two treatment conditions (TT and TTPA) predicted change in teachers’ mental health symptoms over the school year. Although anxiety symptoms increased, on average, for all teachers over the school year, this increase was about one-third of a standard deviation smaller for teachers in the TT treatment group (b = −0.26, p < 0.001) and TTPA treatment group (b = −0.19, p = 0.029) compared to the control group. Being in the TT treatment group was also linked to roughly one-third of a standard deviation fewer depressive symptoms over time (b = −0.19, p < 0.001) compared to the control group. The coefficient for the TTPA treatment group was also negative but only marginally significant (b = −0.13, p < 0.10), suggesting a similar trend. Fig. 2 displays the mean differences in anxiety and depressive symptoms between baseline and follow-up for each of the treatment groups, highlighting that symptoms increased for all groups but less so for the teachers who participated in the intervention.

Fig. 2.

Mean differences in anxiety and depressive symptoms between baseline and follow-up for each of the treatment groups.

5. Discussion

The present study examined mental health among ECE teachers in Ghana, an interesting context because education reform was implemented at the same time that mental health emerged as a public health concern. Guided by the social-ecological framework for occupational health, we identified potential predictors of teachers’ mental health from the literature in high-income countries. We then examined whether these predictors were associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms among teachers at the start of the school year in the fall, as well as change in symptoms over the course of the school year. We also leveraged the school-level randomized controlled trial design of the dataset (Wolf et al., 2019) to explore whether two variations of a TPD intervention predicted teachers’ symptoms over time. To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study on teacher mental health in SSA. Our results suggest that teachers’ personal life stressors and workplace environments are consequential to their mental health, and that TPD interventions that provide training and in-class coaching and parent engagement may benefit teachers’ mental health.

Consistent with recent studies from high-income countries (Hindman and Bustamante, 2019; Jeon et al., 2018), none of the professional background characteristics predicted teachers’ anxiety or depressive symptoms at baseline. Studies from Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo have linked lower education and fewer years of experience to higher levels of burnout among teachers, even after controlling for personal life stressors and workplace conditions (Lee and Wolf, 2019; Wolf et al., 2015). Our results may differ from these studies due to different measures of teacher well-being. Although burnout and depression cover overlapping phenomena, they are distinct. While burnout is an established correlate of overall psychological well-being, depression diagnoses are more likely when burnout is particularly severe (Ahola et al., 2005). Formal anxiety and depressive symptoms constitute a separate domain of psychological well-being, and our results suggest that they should be examined alongside measures of professional well-being such as burnout.

All of the significant workplace environment and personal life measures predicted only baseline mental health symptoms and not changes in symptoms over time. The lack of longitudinal associations was surprising given that two recent studies from the United States found that depression decreased over the school year for teachers in more positive workplace climates (Hindman and Bustamante, 2019; McLean et al., 2017). Because treatment status was the only significant predictor of change in mental health symptoms, it is possible that our results differ due to the TPD intervention. Teachers who were in the TT group experienced fewer depressive symptoms over time, while those in the TTPA group experienced fewer anxiety and depressive symptoms over time, possibly suggesting that the interventions had a larger effect on school climate than any other factor.

Notably, anxiety and depressive symptoms increased over the school year for all teachers in the study, although this increase was smaller for teachers in the treatment groups. This result likely reflects that the benefits of increased training and support extended beyond professional development to also buffer teachers against this increase in symptoms. Training workshops, in-classroom coaching, and parental awareness meetings may have improved teachers’ abilities to cope with the hardships of teaching in a low-resource context. This finding underscores the importance of social support for teachers’ mental health, particularly support from parents, as we also found that lack of parental support was associated with more baseline anxiety symptoms but not depressive symptoms. Therefore, it is possible that teachers in the TTPA group felt more supported and less anxious over the course of the school year as parents learned how to engage with their children’s teachers. A large body of literature highlights the strong, positive effects of parental involvement on children’s education and development (see Castro et al., 2015). Our results suggest that increased parental support for children’s education is linked to fewer anxiety symptoms in children’s teachers. This relationship between parental support and teacher anxiety is an especially salient point for the context of Ghana where many parents do not meet with their child’s teacher and are less likely to play an active role in their child’s education (Wolf, 2019). In sum, our results show that TPD programs focused on improving children’s education may also have the unintended (but positive) outcome of benefiting teachers’ mental health, highlighting an additional pathway through which educational interventions can be successful, particularly in LMICs.

Beyond the classroom, hardships in teachers’ personal lives predicted both anxiety and depressive symptoms at baseline. Particularly, moving to a new community for employment predicted poorer mental health among teachers. As noted above, teachers in Ghana have little choice in their placement, as the government assigns teachers to schools around the country that have openings. Moving to a different area for employment often means leaving behind the support of family, friends, and community. As studies from the United States have shown, support in teachers’ personal lives is important for their mental health, especially when their workplace environments are challenging (McLean et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2019). Using the same data from the QP4G study, Schwartz et al. (2019) showed that teachers who were placed in schools in their home communities were more successful in implementing new classroom practices. It is possible that mental health was the pathway underlying these findings; in other words, teachers who felt better supported in their personal lives had better mental health and were therefore more successful in the classroom.

Finally, that food insecurity and poverty were linked to higher baseline depressive symptoms was not surprising given extensive literature documenting the negative consequences of poor nutrition and low socioeconomic status on health (see Jones, 2017 for a recent review). In particular, that household food insecurity predicted increased depressive symptoms among teachers is consistent with previous work on food insecurity and mental health in Ghana (Atuoye and Luginaah, 2017), although no studies to date have considered the implications for the education system. Although studies from the United States have linked low family income to depressive symptoms among teachers (i.e., Jeon et al., 2018), our specific measures highlight the unique challenges (and the severity of these challenges) facing teachers in LMICs compared to their counterparts in high-income countries. Our results suggest that teachers’ personal hardships are an important lever for addressing teacher mental health and possibly teaching practice, and that providing food supplements or increased income to teachers may be a policy worth considering.

5.1. Strengths and limitations

This study has numerous strengths: a randomized experimental design, two measures of mental health symptomatology, measurements across the school year, and a focus on a LMIC. There are also limitations that should be acknowledged. First, there was notable attrition of the teachers in the sample (about one-fourth of the baseline sample). Although the use of multiple imputation and multiple controls likely limits any bias due to attrition, this level of attrition does still limit our conclusions. We re-ran the analyses with the unimputed data, and the results were very similar. Second, it is important to acknowledge the role of temporality with regards to the workplace environment variables, as the nature and directionality of these associations remain unclear. It is possible that negative work environment conditions exacerbated poor mental health symptoms, but it is also possible that teachers with poor mental health were more likely to have negative perceptions of their workplace environments. Third, all variables in this study were self-reported. It is possible that participants’ mental health affected the way they answered the questionnaires. We tried to limit the bias caused by the single source of data by examining how stressors reported at baseline predicted future mental health outcomes. Finally, the study’s sample is limited to six peri-urban and semi-rural districts in the Greater Accra Region in Ghana, which has implications for generalizability. The findings cannot be extrapolated to teachers in rural areas, who have even higher rates of personal and professional stressors (Cooke et al., 2016), or to teachers in other countries.

6. Conclusions

Our findings have important implications for education and population health more broadly. In order for leaders to fulfill their promise to ensure that every child receives a quality education, they must first make and fulfill promises to the teachers who educate these children. This study adds to the growing body of literature on mental health in the teaching profession in a context where teacher mental health rarely receives consideration. More research in this area is needed; enhanced knowledge is crucial in order to design the most effective educational programs and policies. Our results revealed that teachers in Ghana experience professional and personal hardships that pose risks to their mental health, and suggest that teacher mental health should be explored as an important dimension of the teacher workforce and education system.

Acknowledgment

UBS Optimus Foundation (UBSOF): UBS9307, World Bank Strategic Impact Evaluation Fund (SEIF): WBK5595, National Science Foundation: DGE-1845298.

References

- Aheto-Tsegah C, 2011. Education in Ghana–status and challenges. Commonwealth Educ. Partnersh. 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ahola K, Honkonen T, Isometsä E, Kalimo R, Nykyri E, Aromaa A, Lönnqvist J, 2005. The relationship between job-related burnout and depressive disorders—results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. J. Affect. Disord 88 (1), 55–62. 10.1016/j.jad.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atuoye KN, Luginaah I, 2017. Food as a social determinant of mental health among household heads in the Upper West Region of Ghana. Soc. Sci. Med 180, 170–180. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilock SL, Gunderson EA, Ramirez G, Levine SC, 2010. Female teachers’ math anxiety affects girls’ math achievement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am 107 (5), 1860–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonful HA, Anum A, 2019. Sociodemographic correlates of depressive symptoms: a cross-sectional analytic study among healthy urban Ghanaian women. BMC Public Health, 19(1) 50. 10.1186/s12889-018-6322-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro M, Expósito-Casas E, López-Martín E, Lizasoain L, Navarro-Asencio E, Gaviria JL, 2015. Parental involvement on student academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev 14, 33–46. 10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clearinghouse WW, 2017. Standards Handbook (Version 4.0). Institute of Education Sciences, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Collins D, 2003. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Life Res. 12 (3), 229–238. 10.1023/A:1023254226592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conn KM, 2017. Identifying effective education interventions in sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analysis of impact evaluations. Rev. Educ. Res 87 (5), 863–898. 10.3102/0034654317712025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke E, Hague S, McKay A, 2016. The Ghana poverty and inequality report: Using the 6th Ghana living standards survey. University of Sussex. [Google Scholar]

- De Rouvray C, Jésus P, Guerchet M, Fayemendy P, Mouanga AM, Mbelesso P, Desport JC, 2014. The nutritional status of older people with and without dementia living in an urban setting in Central Africa: the EDAC study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 18 (10), 868–875. 10.1007/s12603-014-0483-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman-Krauss AH, Raver CC, Morris PA, Jones SM, 2014. The role of classroom-level child behavior problems in predicting preschool teacher stress and classroom emotional climate. Early Educ. Dev 25 (4), 530–552. 10.1080/10409289.2013.817030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Education Service, Accra: Ghana, 2012. Programme to Scale-Up Quality Kindergarten Education in Ghana. Ghana Ministry of Education. Retrieved August 14, 2016, at https://issuu.com/sabretom/docs/10_12_12_final_version_of_narrative_op. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Ministry of Education, 2014. Ghana 2013 National Education Assessment: Technical Report. Accra, Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D, Bridges K, Duncan-Jones P, Grayson D, 1988. Detecting anxiety and depression in general medical settings. BMJ 297 (6653), 897–899. 10.1136/bmj.297.6653.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Fuqua J, 2000. The social ecology of health: leverage points and linkages. Behav. Med 26 (3), 101–115. 10.1080/08964280009595758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding S, Morris R, Gunnell D, Ford T, Hollingworth W, Tilling K, Campbell R, 2019. Is teachers’ mental health and wellbeing associated with students’ mental health and wellbeing? J. Affect. Disord 242, 180–187. 10.1016/jjad.2019.03.046.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindman AH, Bustamante AS, 2019. Teacher depression as a dynamic variable: exploring the nature and predictors of change over the head start year. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol 61, 43–55. 10.1016/j.appdev.2018.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon L, Buettner CK, Grant AA, 2018. Early childhood teachers’ psychological well-being: exploring potential predictors of depression, stress, and emotional exhaustion. Early Educ. Dev 29 (1), 53–69. 10.1080/10409289.2017.1341806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AD, 2017. Food insecurity and mental health status: a global analysis of 149 countries. Am. J. Prev. Med 53 (2), 264–273. 10.1016/j.amepre2017.04.008.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley P, Camilli G, 2007. The impact of teacher education on outcomes in center-based early childhood education programs: a meta-analysis. New Brunswick, NJ: Natl. Inst. Early Educ. Res. Rutgers Univ. http://nieer.org/research-report/the-impact-of-teacher-education-on-outcomes-in-center-based-early-childhood-education-programs-a-meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MM, 2016. How does professional development improve teaching? Rev. Educ. Res 86 (4), 945–980. 10.3102/0034654315626800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kidger J, Brockman R, Tilling K, Campbell R, Ford T, Araya R, Gunnell D, 2016. Teachers’ wellbeing and depressive symptoms, and associated risk factors: a large cross sectional study in English secondary schools. J. Affect. Disord 192, 76–82. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassen RM, Chiu MM, 2011. The occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching context. Contemp. Educ. Psychol 36 (2), 114–129. 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LaMontagne AD, Martin A, Page KM, Reavley NJ, Noblet AJ, Milner AJ, Smith PM, 2014. Workplace mental health: developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1) 131. 10.1186/1471-244X-14-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsbergis PA, Grzywacz JG, Lamontagne AD, 2014. Work organization, job insecurity, and occupational health disparities. Am. J. Ind. Med 57 (5), 495–515. 10.1002/ajim.22126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Wolf S, 2019. Measuring and predicting burnout among early childhood educators in Ghana. Teach. Teach. Educ.: An International Journal of Research and Studies 78 (1), 49–61. 10.1016/j.tate.2018.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Loncar D, 2006. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 3 (11), e442. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean L, Abry T, Taylor M, Gaias L, 2020. The influence of adverse classroom and school experiences on first year teachers’ mental health and career optimism. Teach. Teach. Educ 87 (102956). 10.1016/j.tate.2019.102956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLean L, Abry T, Taylor M, Jimenez M, Granger K, 2017. Teachers’ mental health and perceptions of school climate across the transition from training to teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ 65, 230–240. 10.1016/j.tate.2017.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLean L, Connor CM, 2015. Depressive symptoms in third-grade teachers: relations to classroom quality and student achievement. Child Dev. 86 (3), 945–954. 10.1111/cdev.12344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nubukpo P, Preux PM, Houinato D, Radji A, Grunitzky EK, Avode G, Clement JP, 2004. Psychosocial issues in people with epilepsy in Togo and Benin (West Africa) I. Anxiety and depression measured using Goldberg’s scale. Epilepsy Behav. 5 (5), 722–727. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osei GM, 2006. Teachers in Ghana: issues of training, remuneration and effectiveness. Int. J. Educ. Dev 26 (1), 38–51. 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2005.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, 2017. Talking sensibly about depression. PLoS Med. 14 (4), e1002257. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafael F, Houinato D, Nubukpo P, Dubreuil CM, Tran DS, Odermatt P, Preux PM, 2010. Sociocultural and psychological features of perceived stigma reported by people with epilepsy in Benin. Epilepsia 51 (6), 1061–1068. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathod S, Pinninti N, Irfan M, Gorczynski P, Rathod P, Gega L, Naeem F, 2017. Mental health service provision in low-and middle-income countries. Health Serv. Insights 10. 10.1177/1178632917694350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Ghana, 2004. Early Childhood Care and Development Policy. Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs, Accra, Ghana. Retrieved September 11, 2018, from http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/88527/101252/F878960202/GHA88527.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Ghana, 2012. Mental health Act. Retrieved October 19, 2019, from. https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/528f243e4.pdf.

- Roberts AM, Gallagher KC, Daro AM, Iruka IU, Sarver SL, 2019. Workforce well-being: personal and workplace contributions to early educators’ depression across settings. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol 61, 4–60. 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandefur J, 2016. Internationally Comparable Mathematics Scores for Fourteen African Countries (Working Paper No. 444). Center for Global Development, Washington, DC. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/math-scores-fourteen-african-countries0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Sandilos LE, Cycyk LM, Scheffner Hammer C, Sawyer BE, López L, Blair C, 2015. Depression, control, and climate: an examination of factors impacting teaching quality in preschool classrooms. Early Educ. Dev 26 (8), 1111–1127. 10.1080/10409289.2015.1027624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner M, 2015. A simple poverty Scorecard™ for Ghana. http://www.simplepovertyscorecard.com/GHA_2012_ENG.pdf.

- Schwartz K, Cappella E, Aber JL, Scott MA, Wolf S, Behrman JR, 2019. Early childhood teachers’ lives in context: implications for professional development in under-resourced areas. Am. J. Community Psychol 63, 270–285. 10.1002/ajcp.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman E, Kim S, Raza M, Ishihara M, Halpin PF, 2018. Assessment of pedagogical practices and processes in low and middle income countries: findings from secondary school classrooms in Uganda. Teach. Teach. Educ 71, 283–296. 10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sipsma H, Ofori-Atta A, Canavan M, Osei-Akoto I, Udry C, Bradley EH, 2013. Poor mental health in Ghana: who is at risk? BMC Public Health, 13(1) 288. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M, McLean L, Bryce CI, Abry T, Granger KL, 2019. The influence of multiple life stressors during teacher training on burnout and career optimism in the first year of teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ 86. 10.1016/j.tate.2019.102910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO, 2015. Education for All Global Monitoring Report Regional Overview: Subsaharan Africa. UNESCO, Paris. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF, 2015. Ghana’s District League Table 2015. Retrieved from. https://www.unicef.org/ghana/media_9697.html.

- Whitaker RC, Dearth-Wesley T, Gooze RA, 2015. Workplace stress and the quality of teacher–children relationships in Head Start. Early Child. Res. Q 30, 57–69. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willis G, Lawrence D, Thompson F, Kudela M, Levin K, Miller K, 2005, November. The use of cognitive interviewing to evaluate translated survey questions: lessons learned. In: Conference of the Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology, Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, 2019. The perils and promises of listening to parents: encountering unexpected barriers to improving preschool in Ghana. In: Paper Presented at the Comparative International Education Society, April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, Aber JL, Behrman JR, Tsinigo E, 2019. Experimental impacts of the “Quality preschool for Ghana” interventions on teacher professional well-being, classroom quality, and children’s school readiness. J. Res. Educ. Effect 12 (1), 10–37. 10.1080/19345747.2018.1517199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, Torrente C, McCoy M, Rasheed D, Aber JL, 2015. Cumulative risk and teacher well-being in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Comp. Educ. Rev 59 (4), 717–742. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/682902. [Google Scholar]

- Yang R, You X, Zhang Y, Lian L, Feng W, 2019. Teachers’ mental health becoming worse: the case of China. International Journal of Educational Development, 70. 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.102077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young R, Johnson DR, 2015. Handling missing values in longitudinal panel data with multiple imputation. J. Marriage Fam 77, 277–294. 10.1111/jomf.12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]