Abstract

Two PCR primer sets were developed for the detection and quantification of cytochrome cd1-denitrifying bacteria in environmental marine samples. The specificity and sensitivity of these primers were tested. Both primer sets were suitable for detection, but only one set, cd3F–cd4R, was suitable for the quantification and enumeration of the functional community using most-probable-number PCR and competitive PCR techniques. Quantification of cytochrome cd1 denitrifiers taken from marine sediment and water samples was achieved using two different molecular techniques which target the nirS gene, and the results were compared to those obtained by using the classical cultivation method. Enumerations using both molecular techniques yielded similar results in seawater and sediment samples. However, both molecular techniques showed 1,000 or 10 times more cytochrome cd1 denitrifiers in the sediment or water samples, respectively, than were found by use of the conventional cultivation method for counting.

It is generally believed that only a small fraction of environmental bacteria are recovered by current cultivation techniques and that the quantification of microorganisms is therefore biased. The most prominent methods which have been suggested for studying this noncultivated fraction of indigenous community bacteria are based on using nucleic acids. Techniques such as most-probable-number (MPN) PCR and competitive PCR have been developed to quantify specific groups of bacteria by amplifying the 16S fragment in the ribosomal DNA (17, 25, 28, 31) or in the functional gene (15, 21, 35). In using studies which target metabolic function, in some cases all the organisms of a species or genus possess the same metabolic function (nitrification or sulfate reduction, for example). Using a probe which targets a specific part of the ribosomal gene can therefore give an indication of the presence of the bacterial group which is capable of that function. On the contrary, if the function is spread among a variety of bacterial species, and only a small number of strains of each species possess that function, it is not possible to perform the classic approach of targeting the ribosomal gene. In this case the conserved region of a functional gene may serve as a suitable target. The use of a functional gene requires sufficient genetic homology of the structural genes and the availability of multiple sequences in order to reliably design primers. When the function is widely spread over the phylogenic groups, the primers used for molecular detection become more degenerated. This increases the risk of nonspecific annealing of the primer onto nontarget sequences, which in turn leads to low specificity and low sensitivity of the technique. Denitrification is a good example of a process which is performed by a great diversity of bacterial strains which come from all the major physiological groups, with the exception of Enterobacteriaceae. The nitrite reductase gene is a key enzyme for this metabolic process. Depending on the strain, denitrifying bacteria possess either cytochrome cd1 or copper nitrite reductase (NirS or NirK). Different PCR primer systems for the amplification of the two nitrite reductase genes have been designed (8, 16, 34). These primers can be used to amplify nir genes in denitrifying strains from culture collections (8, 16), unidentified isolates from different wastewater treatment plants, and DNA extracts from activated sludge (16) or aquatic samples (8, 34). These primers have not yet been tested for the quantification of denitrifying bacteria. In this study, we compared the different methods used in the quantification of denitrifying bacteria which contain the nirS gene encoding the cd1 type Nir in environmental samples. Enumeration using the classical cultivation method is compared to two quantitative molecular techniques, MPN-PCR and competitive PCR (cPCR). The specificities and sensitivities of the two primer sets used in the two molecular methods for counting are examined. This report not only compares bacterial enumeration by traditional cultivation with enumeration by molecular techniques but also, for the first time, compares two different PCR-based methods for quantification.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

A variety of denitrifying and nondenitrifying bacterial strains (Table 1) were used to evaluate the specificity of the designed PCR primers. All strains were grown aerobically at 30°C. Pseudomonas stutzeri ATCC 14405, P. stutzeri ATCC 11607, Pseudomonas fluorescens AK15, Paracoccus denitrificans ATCC 19367, Flavobacterium sp. strain ATCC 33514, Achromobacter cycloclastes ATCC 13867, Pseudomonas denitrificans ATCC 13867, Alcaligenes faecalis ATCC 8750, Bacillus azotoformans ATCC 29788, and Escherichia coli K-12 were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (29). Pseudomonas nautica 617 IPC 617/1.85, Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus ATCC 49840, Marinobacter sp. strain CAB DSMZ 11572, marine isolates Al1, P3, 5, and P4, and Vibrio sp. strain 45 (6) were grown in BHA medium (24).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study and test of the PCR primer sets to amplify a fragment of the nirS gene

| Strains | Nir type (reference) | Result of PCRb with:

|

Result of hybridizationc with the:

|

N20 productiond | DDC inhibition of NirS activitye | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cd8F–cd2R primers | cd3F–cd4R primers | cd8F–cd2R fragment | cd3F–cd4R fragment | ||||

| P. stutzeri ATTC 14405 | cd1 (12) | + | + | + | + | ND | ND |

| P. stutzeri ATCC 11607 | cd1 (29) | + | + | + | + | ND | ND |

| P. fluorescens AK15 (TG) | cd1 (32) | + | + | + | + | ND | ND |

| P. nautica 617 IPC 617/1.85 | cd1 (3) | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Paracoccus denitrificans ATCC 19367 | cd1 (5) | + | + | + | + | ND | ND |

| M. hydrocarbonoclasticus ATCC 49840 | cd1a | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Marinobacter sp. strain CAB | cd1a | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Flavobacterium sp. strain ATCC 33514 | cd1 (5) | + | − | + | − | ND | ND |

| Marine isolate Al1 | cd1a | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Marine isolate P3 | cd1a | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Marine isolate 5 | cd1a | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| A. cycloclastes ATCC 13867 | Cu (5) | − | 0 | − | − | + | + |

| Marine isolate P4 | Cua | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| Pseudomonas denitrificans ATCC 13867 | Cu (5) | − | − | − | − | ND | ND |

| A. faecalis ATCC 8750 | Cu (12) | 0 | 0 | − | − | ND | ND |

| B. azotoformans ATCC 29788 | Cu (5) | 0 | 0 | − | − | ND | ND |

| E. coli | None | − | 0 | − | − | ND | ND |

| Vibrio marine isolate | Nonea | − | − | − | − | − | ND |

Our work based on the DDC inhibition of nitrite reductase activity.

+, visible band of the expected size; 0, band of any other size; −, no visible band.

A positive hybridization signal (+) was defined as a visible band of the expected size (50°C).

ND, not determined; positive production of nitrous oxide (+) corresponds to the reduction of at least 50% of the nitrate in N2O.

Positive inhibition (+) corresponds to 100% inhibition after DDC addition (10 mM).

Denitrification and nitrite reductase activity.

The strains which had been isolated from the environmental samples were screened for denitrifying activity. After anaerobic growth in the presence of 20 kPa of acetylene (in order to block the last step of denitrification), nitrous oxide accumulation was measured using gas chromatography (as described by Michotey and Bonin [22]). For the detection of nitrite reductase activity, enzymatic assays were used. The cells were harvested at the end of the exponential phase of growth, washed twice with artificial seawater (ASW) (1), and resuspended in 0.04 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6) containing benzamidine (10 mM). Cell suspensions were passed through a French press. Any intact cells and debris were eliminated by centrifuging for 10 min at 11,000 × g. The nitrite reductase activity of the extracts was assayed spectrophotometrically (600 nm) using benzyl viologen as the artificial electron donor in the presence of 20 mM nitrite (2). Any copper nitrite reductase activity was identified by becoming inhibited by the addition of 10 mM diethyldithiocarbamate (DDC) (30, 38). In this experiment A. cycloclastes and P. nautica were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

DNA extraction from culture strains.

Genomic DNA was obtained from pure cultures by treatment with lysozyme-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and subsequent precipitation using ethanol (29). The concentration of DNA was determined spectrophotometrically following treatment with RNase.

A standard curve was constructed using a mixture of six marine cultures of denitrifying strains of bacteria (P. nautica, M. hydrocarbonoclasticus, Marinobacter sp. strain CAB, and marine isolates Al1, P3, and 5). The total number of cells in this mixture was quantified by staining the cells with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride) and counting the bacteria using an epifluorescence microscope as described previously (26). Extraction of bacterial DNA was carried out using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). A 0.4-ml volume of culture was centrifuged, and the subsequent pellet was resuspended in 180 μl of buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1.2% Triton, and 20 mg of lysozyme/ml) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. A 20-μl volume of proteinase K and 200 μl of buffer AL (Qiagen) were added, and further incubation was performed at 56°C for 30 min. This was followed by an additional incubation at 90°C for 15 min. A 200-μl volume of ethanol was then added to the lysate, and DNA purification was carried out accordingly (Qiagen). Following the purification of nucleic acids, RNA was removed by the addition of RNase (Boehringer Mannheim).

Oligonucleotide primers.

Two primer sets were designed following the alignment of NirS amino acid sequences, which were available in the gene banks. These sequences were retrieved from GenBank and EMBL, and amino acid sequences were aligned with Clustal W (32). Consensus regions that contained amino acids with less degenerated codons were chosen. Primer sequences corresponded to degenerate sequences of amino acids in the conserved regions of the enzyme. The first (cd2R–cd8F) and the second (cd3F–cd4R) set of primers correspond to the middle and the carboxyl half of the protein, respectively. During completion of this article, Braker et al. (8) reported the development of primers for nirS detection, and their primer nirS6R appears to be the same as cd4R (Table 2). In constructing an internal standard, an additional primer, cdst, was used. The sequence of the cdst primer corresponds to that of the cd4R primer, but cdst has an additional sequence on the 3′ end corresponding to the sequence found from position 1386 to position 1397 on the nirS gene of P. stutzeri ATCC 14405 (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Primer sequences and positions used to amplify fragments from nirS

| Primera | Positionb | Primer sequencec (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| cd2 R | 826–844 | CCNGTYTCYTTNACRTTNAC |

| cd8 F | 475–491 | GGNTAYGCNGTNCAYAT |

| cd3 F | 826–844 | GTNAAYGTNAARGARACNGG |

| cd4R | 1549–1565 | ACRTTRAAYTTNCCNGTNGG |

| cdst | 1386–1397/1548–1563 | ACRTTRAAYTTNCCNGTNGGATYGCCTTG |

Forward and reverse primers are indicated by the last letters F and R, respectively.

Positions in the nirS gene of P. stutzeri Zobell (EMBL accession no. X56813).

R represents A or G; Y represents C or T; N represents A, C, G, or T.

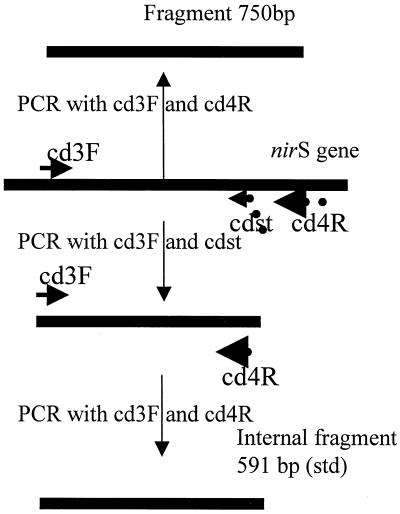

Construction of an internal standard for quantification of nirS.

In order to obtain an internal standard, a shorter fragment with the same primers at the ends was constructed. This fragment (591 bp) is constructed by truncating the 3′ end of a 750-bp fragment of nirS of P. stutzeri ATCC 14405. Using PCR with the cd3F and cdst reverse primer (see Table 2), the sequence corresponding to the cd4R primer was added to the 3′ end (Fig. 1). The internal standard was synthesized by PCR using a “touchdown” protocol (12). The hybridization temperature of the reaction was decreased 1°C every second cycle from 60°C to a “touchdown” of 57°C, at which temperature 20 cycles were carried out. The denaturation, hybridization, and elongation steps were performed for 30, 20, and 30 s, respectively. The main product from PCR was the 591-bp fragment. After electrophoresis, the band was excised from the gel and purified using an agarose gel DNA extraction kit (Boehringer Mannheim). A 10-fold dilution of this fragment extract was used for amplification with the cd3F and cd4R primers. The concentration of the internal standard was estimated by comparing the intensity of its band on an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel to that of the 500-bp band from the calibrated molecular weight standard.

FIG. 1.

Scheme showing the construction of the internal standard of 591 bp used for cPCR with primer set cd3F–cd4R. Dots represent identical sequences.

PCR amplification of nirS genes.

The two sets of primers used for PCR (cd2R–cd8F and cd3F–cd4R) are based on cytochrome cd1 gene sequences from denitrifying bacteria and amplify nirS fragments of approximately 272 and 750 bp. PCR amplifications of nir fragments were carried out with 25 μl of reaction mixture (20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2) containing 0.2 mM each deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate, 160 pmol of each oligonucleotide primer, and 0.5 U of Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim). For PCR on the DNA from pure cultures of denitrifiers, 50 ng of template DNA was used. To prepare a standard curve for nirS quantification, DNA of marine nondenitrifying bacteria (marine isolate Vibrio) was added to the PCR mixture. This DNA corresponded to 106 cells of marine isolate Vibrio. One microliter of the internal standard, corresponding to 2.4 × 104 DNA templates, was also introduced in the PCR tube for cPCR.

Amplification was achieved using a minicycler (MJ Research) for 30 cycles. Template DNA was initially denatured for 2 min at 94°C, and each cycle consisted of a 30-s denaturing step at 94°C, a 30-s annealing step at 50°C for the cd3F–cd4R set of primers and 40°C for the cd2R–cd8F set of primers, and a 40-s elongation step at 72°C. The final elongation step was extended for 3 min. The amplification products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1 or 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gels (Eurogentec) depending on the quantity of the PCR products.

Quantification of bacterial numbers.

In order to compare classical and molecular methods for enumeration of denitrifying bacteria, both techniques must be used on the same bacterial extract. Methods used to extract bacteria from the environmental samples should not damage the cell or DNA (breakage). For this reason, bacterial extraction has been carried out in the absence of chemicals and sonification. Microorganisms from 500 ml of a water sample collected in the plume of the Rhône River (March 1999) were either centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min or filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size cellulose nitrate Whatman filter. The filters were incubated in 5 ml of 0.2-μm-pore-size-filtered water from the same sampling station for 3 h at 4°C. Cells remaining on the filter were scraped off with a razor blade and pelleted by centrifugation at 22,000 × g for 10 min. Quantification of the denitrifying bacteria in the sediment samples was performed using a sediment taken from the mouth of the Rhône River (collected in March 1999). A subsample of sediment (6.3 g [dry weight]) was obtained by mixing with approximately 10 ml of the upper 2.5-cm layer of sediment. Bacteria were removed from the sediment by the extraction technique of Doria and Bianchi (13) modified as follows. Thirty milliliters of sterile (0.2-μm-pore-size-filtered) seawater was added to the sediment and mixed with a vortex agitator (Maxi-Mix Bioblock) at 1,200 rpm at 4°C for 1 h. Three consecutive extractions were performed, and the three washings were mixed together. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 22,000 × g for 10 min. Bacterial counts using the culture and molecular methods were performed on the suspended pellet.

For the bacterial count using cultivation techniques, aerobic heterotrophic bacterial numbers were measured using the MPN culture method. The medium was made up in filtered seawater (0.22-μm-pore-size cellulose nitrate Whatman filter) supplemented with NH4Cl (3 g/liter), sodium acetate (0.2 g/liter), sodium succinate (0.2 g/liter), and Biotrypticase (2 g/liter). Numbers of denitrifying bacteria were measured by the N2O-MPN technique using the same medium amended with 10 mM nitrate and acetylene according to Bonin et al. (5). Triplicate tubes for each dilution were incubated 20°C for 15 days, and the positive tubes were counted. Subsequent quantification could be made using Cochran tables according to reference 9.

For bacterial counts using molecular techniques, cells were concentrated either by filtration and centrifugation or by centrifugation alone and were lysed using the same protocol as that for the purification of bacterial DNA for the standard curve. For the MPN-PCR technique, amplification was tested using three tubes per dilution. Enumeration of denitrifiers was performed according to the number of positive amplifications per dilution and the minimal number of targets that could be amplified with the primers, and with the help of Cochran tables (9). For cPCR, PCR was performed on a serial dilution of the DNA from the samples and with a constant number (2.4 × 104) of internal fragments. For the quantification of denitrifiers, the intensities of the two amplified bands were measured and the number of target cells was calculated according to the standard curve.

Densitometry.

To quantify PCR products, photographs of the ethidium bromide-stained gels were scanned (Scanjet II CX; Hewlett-Packard) and measurements of each band density were made according to a vertical axis. Integrations were performed with PC software (Image Master; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). In order to compare the band intensities from separate agarose gels, the calibration band of the molecular weight standard, which was 700 bp long and contained 70 ng (DNA QuantLadder; GenSura, Del Mar, Calif.), was run on each gel.

Hybridization analysis of the nir products from total DNA in bacterial cultures and environmental samples.

Products from the amplification procedure, 50 ng of template DNA from pure cultures, and 4 or 6.4 ng of DNA extracted from environmental samples (seawater or sediment, respectively) were analyzed on agarose gels (1% [wt/vol]). After electrophoresis, the DNA was transferred onto a positively charged polyamide membrane (Schleicher & Schuell) by vacuum transfer. The DNA was cross-linked to the membrane by UV light. The probe corresponding to the nirS fragment of P. stutzeri ATCC 14405 was labeled by PCR with digoxigenin dUTP. The membrane was hybridized using 30 ml of hybridization solution (Boehringer Mannheim) containing the specific probe (25 ng ml−1). Hybridization was carried out at 50°C overnight. Following hybridization, the membrane was washed twice for 5 min at room temperature in 100 ml of a solution containing 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS and twice for 15 min at 50°C with 100 ml of a solution containing 0.5× SSC and 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS. Subsequently, the hybridization of the digoxigenin-labeled probe was detected by an enzyme-linked immunoassay with nitroblue tetrazolium/X-phosphate as the substrate as specified by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim).

RESULTS

Testing the specificity of the PCR primers used for nirS detection.

We developed PCR primers to amplify the nir fragment coding for cytochrome cd1-Nir. The PCR primers were tested for specificity on denitrifying strains containing either the cytochrome cd1 or the Cu nitrite reductase gene, and on nondenitrifying strains (Table 1). Among the screened strains, some had already been identified as denitrifying (6, 10, 16), but we also tested both primer sets on seven strains that we had previously isolated from marine sediment and that could grow anaerobically in the presence of nitrate.

These strains were tested for nitrate utilization in anaerobiosis and for nitrous oxide production when grown in the presence of acetylene and nitrate (Table 1). Six out of seven strains were identified as denitrifiers because they could utilize nitrate in anaerobiosis and stoichiometrically reduce it to nitrous oxide. The seventh strain, the marine isolate Vibrio sp. strain 45, did not accumulate nitrous oxide under these conditions and was identified as being a nitrate-ammonifying strain (6). All the tested marine isolates exhibited nitrite reductase activity. The type of nitrite reductase was determined using DDC, which selectively inhibits copper nitrite reductase. The reductase activity of five out of six strains was not inhibited by DDC (Table 1). The nitrite reductase activity of the marine isolate P4 was inhibited by DDC, indicating that this strain possesses a Cu nitrite reductase.

For PCR amplification, different annealing temperatures were evaluated at intervals between 30 and 55°C. Some nonspecific bands disappeared at temperatures higher than 40°C and at 50°C for the cd2R–cd8F and cd3F–cd4R primer sets, respectively; however, some specific bands were also lost. Therefore, annealing was performed at 40°C for the cd2R–cd8F primer set and at 50°C for the cd3F–cd4R primer set. The specificity of amplified fragments was checked by hybridization with a fragment of P. stutzeri ATCC 14405 nirS. All fragments of the expected size were recognized by the probe, indicating that the amplified fragment corresponded to the nirS fragment (data not shown).

Sensitivity of the primer sets with pure target DNA, in the presence of nontarget DNA.

In order to perform quantitative PCR, it is necessary to test the sensitivity of the primers. Suitable primer sets must be sensitive in order to detect the specific target DNA of the sample, and their sensitivity must not vary with the proportion of target DNA to nontarget DNA, since the percentage of denitrifiers is not constant in environmental samples.

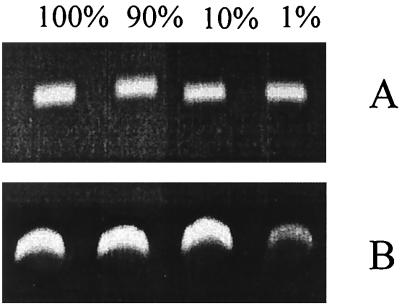

The sensitivity of both primer sets for the limit of detection of denitrifiers was first tested with a constant number of target genes of a mixture of marine cytochrome cd1 type denitrifiers from our lab collection (corresponding to 7.2 × 104 cells of cytochrome cd1 type denitrifiers) in the presence of DNA corresponding to various numbers of nontarget marine microorganisms (between 0 and 7 × 106 cells of marine isolate Vibrio sp. strain 45). The tested percentage corresponded to that normally measured in environmental samples. Figure 2 shows the results of the amplification of nirS under these conditions. With the cd2R–cd8F and cd3F–cd4R primer sets, the intensity of the band was constant when the percentage of target organisms varied from 100 to 10%. At 1%, a significant decrease of 28% in intensity was observed and a nonspecific band of approximately 1 kb appeared with the cd2R–cd8F primer set, whereas with the cd3F–cd4R primer set a slight decrease in band intensity (about 8%) was observed.

FIG. 2.

Effect of the proportion of target to nontarget DNA on the efficiency of PCR with primer sets cd3F–cd4R (A) and cd2R–cd8F (B). Target DNA corresponds to 7.2 × 104 cells of a mixture of six marine cytochrome cd1-denitrifying bacteria. Nontarget DNA was extracted from a Vibrio marine isolate.

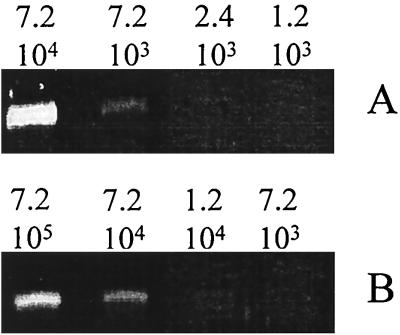

In order to determine the minimum number of target genes that yielded fragment amplification (Fig. 3), in the absence or in the presence of 106 nontarget DNA molecules, PCRs were performed with serial dilutions of DNA. PCR of each dilution was performed in triplicate. For the cd2R–cd8F primer set, fragment amplification was obtained with a minimum of 120 target DNA molecules present; for the same primer set in the presence of nontarget DNA, 7.2 × 103 target DNA molecules were necessary, i.e., 60-fold more. On the other hand, using the cd3F–cd4R primer set, the detection limits were 1.2 × 103 and 2.4 × 103 in the absence or in the presence of 106 DNA molecules of nontarget cells, respectively, i.e., only twofold more. The detection limit of the latter primer is almost constant in the presence of various amounts of nontarget DNA.

FIG. 3.

Determination of the detection limit of nirS amplification from DNA extracted from a mixture of six marine cytochrome cd1-denitrifying bacteria with primer set cd3F–cd4R (A) or cd2R–cd8F (B), in the presence of nontarget DNA extracted from 106 cells of a Vibrio marine isolate. The number of target DNA molecules in each PCR tube is indicated above each lane.

In conclusion, our results show that both sets of primers are suitable for the detection of denitrifiers in marine samples, but only one set of primers (cd3F–cd4R) is suitable for their quantification. The sensitivity of this primer and the intensity of the amplified band are almost completely unaffected by the presence of differing quantities of nontarget DNA. This primer set should therefore be used for the quantification of denitrifiers in marine water and sediment samples by molecular techniques (cPCR and MPN-PCR).

cPCR with the cd3F–cd4R primer set and construction of the standard curve.

cPCR was performed with the cd3F–cd4R primer set, which amplifies the 5′ end of the nirS gene. In noncompetitive PCR, this primer allowed the amplification of a number of target DNA molecules ranging from approximately 2 × 103 to 107. It has been reported that cPCR is more accurate when target and standard DNAs are present in equal quantities in the PCR tube. In order to adjust the number of standard DNA fragments to the center of the amplification range, 2.4 × 104 standard fragments were introduced into all the PCR tubes. Under these conditions a standard curve was established using the coamplification of the standard and of cytochrome cd1 type denitrifier nirS genes extracted from known numbers of cells (a mixture of six denitrifying strains) in the presence of nontarget DNA (DNA extracted from 106 cells of a Vibrio marine isolate) or in the presence of DNA extracted from 5 ml of a water sample (6 × 104 heterotrophic bacteria). PCR under these conditions (with a constant amount of standard fragment) yielded amplification products that were detectable on ethidium bromide-stained gels. These corresponded to 7.2 × 106 to 1.2 × 104 cells in the amplification reaction mixture (Fig. 4). Each PCR was performed three times. From the intensity of the two bands, the 750-bp/591-bp fragment ratios were calculated and plotted against the number of target cells in the PCR tube. The standard curve was fitted by the least-squares method (Fig. 5). The standard curve was log-log over almost 3 orders of magnitude. Amplification in the presence of nontarget DNA, corresponding to DNA from a Vibrio marine isolate or DNA from 5 ml of natural water (containing 6 × 104 heterotrophic bacteria), gave similar results.

FIG. 4.

cPCR with primers cd3F–cd4R for construction of the standard curve. The standard band (591 bp) corresponds to the amplification of the internal standard (2.4 × 104 copies), and the 750-bp fragment corresponds to nirS amplification of a mixture of six marine cytochrome cd1-denitrifying bacteria added in different amounts. PCR was performed in the presence of bacterial nontarget DNA extracted from 106 cells of a Vibrio marine isolate. MW, molecular weight standard. The number of target DNA copies in each PCR tube is indicated above each lane.

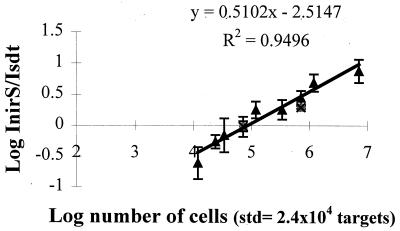

FIG. 5.

Standard curve for quantitative cPCR. The ratio of the intensity of PCR products of target DNA (750-bp nirS fragment) to standard DNA (591-bp fragment) was plotted against the initial amount of target DNA (extracted from a known number of cells in a mixture of six marine cytochrome cd1-denitrifying bacteria) on a log scale. The number of standard fragments was kept constant at 2.4 × 104 copies per tube. PCR was performed in the presence of nontarget DNA extracted from 106 Vibrio sp. strain 45 cells (triangles) or from 5 ml of seawater containing 6 × 104 heterotrophic bacteria (squares). Error bars, standard deviations.

Enumeration of cytochrome cd1-denitrifying bacteria in two environmental samples by classical microbiological and MPN-PCR and cPCR methods.

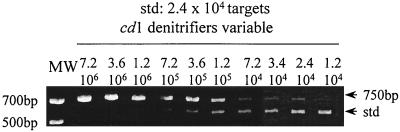

The partial extraction of bacteria from sediment was performed by a very gentle technique in order to prevent damage to bacteria which would result in underestimation in counting by the cultivation technique. Enumerations of aerobic heterotrophic and denitrifying bacteria were performed in seawater and sediment samples by traditional MPN cultivation techniques (Table 3). The lower and upper limits correspond to theoretical maximal and minimal limits calculated from Cochran tables (9). The percentages of denitrifiers determined by classical cultivation methods were 1 and 0.16% for the water and the sediment sample, respectively. Cytochrome cd1 denitrifiers were also quantified by MPN-PCR and cPCR with the standard curve previously obtained (Fig. 6). Enumerations with cPCR were performed in triplicate. Table 3 gives the means and the measured maximal and minimal experimental values. For MPN-PCR, the lower and upper limits were calculated from the characteristic number with 3 tubes per dilution according to statistical tables (9). The 750-bp bands amplified from environmental samples and the 591-bp band from the internal standard were recognized by the probe of P. stutzeri ATCC 14405 nirS (data not shown). For all natural samples, enumeration of cytochrome cd1 denitrifiers by MPN-PCR and cPCR gave similar results. For water and sediment samples, results of quantification by these molecular techniques were, respectively, 1 and 3 orders of magnitude higher than those obtained by classical culture methods, which also included the total number of denitrifiers (those possessing Cu nitrite reductase and those possessing cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase). cPCR has been performed on water samples treated by filtration and centrifugation, and counts were not significantly different (data not shown). The results suggest that a large portion of denitrifiers in natural samples could not be cultivated; only 0.1 to 10% of denitrifiers were recoverable on the culture medium.

TABLE 3.

Quantification of aerobic heterotrophic and denitrifying bacteria by traditional cultivation and quantitative molecular techniques with cd3F–cd4R primers

| Sample | No. of bacteria counted by cultivation techniques (95% CI)a

|

No. of bacteria counted by quantitative molecular techniques

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic heterotrophic bacteria, by MPN | Denitrifying bacteria, by N2O–MPN | Denitrifying bacteria, by MPN-PCR | Denitrifying bacteria, by cPCRb | |

| Water sample (no. of bacteria ml−1) | 2.5 × 104 (0.5 × 104–12 × 104) | 2.5 × 102 (0.5 × 102–12 × 103) | 1.2 × 103 (2.5 × 102–5.7 × 103)a | 6.8 × 102 (5.4 × 102–8.4 × 102) |

| Bacteria removed from sediment sample (no. of bacteria g−1 [dry wt]) | 5.9 × 106 (1.2 × 106–28 × 106) | 1.0 × 104 (0.21 × 104–50 × 104) | 15.8 × 106 (3.6 × 106–80 × 106)a | 27.2 × 106 (17.7 × 106–34.9 × 106) |

95% confidence limits, calculated according to limits given by Cochran tables.

Upper and lower limits correspond to experimental higher and lower values.

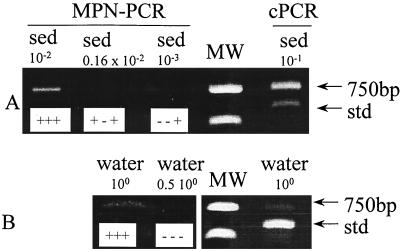

FIG. 6.

Quantification by MPN-PCR and cPCR of cytochrome cd1 denitrifiers in marine sediment (sed) (A) and seawater (B) samples. For cPCR, 2.4 × 104 copies of the internal standard (std) fragment were introduced initially into the PCR tube. For MPN-PCR, results of triplicates of each dilution are shown in the corresponding lane (+, positive amplification; −, negative amplification). The dilution of each DNA extract is indicated above the lane. MW, molecular weight standards (700 and 500 bp).

DISCUSSION

Our main objective was to test the different quantification methods (culture as well as molecular techniques) for bacteria sharing the same metabolic pathway in marine samples. This study was performed using phylogenetically diverse denitrifying bacteria. Denitrifiers are ubiquitous facultatively anaerobic bacteria, and they reduce nitrate to gaseous products only in anaerobiosis or in aerobic-anaerobic interface environments. In marine samples, denitrifying populations are found mainly in sediments but also in the water column, where their activities are associated with particles (22). Marine denitrifiers usually represent between 0.1 and 10% of the total bacterial population in sediments (3), as well as being found in the water column (our unpublished data on water of the Mediterranean Sea or from the Rhône River plume). In order to perform quantitative PCR on cytochrome cd1 denitrifiers, it was necessary to (i) use degenerated primers, increasing the risk of nonspecific annealing of these primers onto nontarget sequences, leading to putative low specificity and loss of sensitivity in the techniques and (ii) to choose primers able to amplify the nirS gene in the presence of a large background of nontarget bacterial DNA, in the same proportion as that found in environmental samples (90 to 99.9%). Furthermore, the efficiency of the PCR should not depend on the proportion of target to nontarget DNA.

To quantify by using molecular techniques, the capacity of the primer must be tested extensively in order to obtain reliable interpretable results. In this study, we have tested the specificities and the sensitivities of two sets of primers in order to use them for quantitative PCR. The tested primers show the same range of specificity as those already published (8, 16), but our designed primers differ in that they allow not only detection but quantification. The sensitivities of the two primer sets appeared to be quite different: without nontarget DNA addition, amplification is 10-fold more sensitive with the cd2R–cd8F primer set than with the cd3F–cd4R primer set; after addition of nontarget DNA, the sensitivity with the cd3F–cd4R primer set is slightly affected, whereas amplification is 10-fold less sensitive using the cd2R–cd8F primer set. For quantification, the amplification efficiency must stay constant whatever the proportion of target to nontarget organisms. As it is probably impossible to find environmental samples without denitrifying DNA, we have chosen to introduce a bacterial marine DNA into PCR samples as the nontarget DNA source. In order to approximate as closely as possible the conditions encountered in particles or in sediment, we have chosen to introduce a nondenitrifying strain that shares the same ecological microniches and the same growth conditions as the denitrifiers. Nitrate-ammonifying bacteria outcompete denitrifiers for nitrate in aerobic-anaerobic interface marine environments (7, 22, 23) and can be isolated from the same samples as denitrifiers. Thus, we have chosen to use a nitrate-ammonifying bacterium (Vibrio sp. strain 45) that was isolated from the same sediment and at the same time as the other marine isolates used in this study (P3, 5, and P4) (6).

The cd2R–cd8F primer set does not seem suitable for MPN-PCR and cPCR, since the minimal number of target DNA molecules necessary to obtain amplification varies with the proportion of target DNA to nontarget microorganisms. In contrast, the intensity of the amplified band with the cd3F–cd4R primer set is almost constant in the percentage range usually encountered in marine environments. Our cd3F–cd4R primer set would therefore be suitable for quantification of cytochrome cd1 type denitrifiers in natural samples. Our results doubtless show that a primer set might be suitable for detection but not for quantification.

A standard log-log curve was constructed by using the cd3F–cd4R primer set with a constant quantity of internal standard and nontarget DNA. Using cPCR the yield of the two products is described as follows: log(Nn1/Nn2) = log(N01/N02) + n × log(eff1/eff2) (21, 37). If the amplification efficiency of the target amplicon (eff1) and that of the internal standard (eff2) are equal, the ratio of products (Nn1/Nn2) during any cycle (n) depends solely on the ratio (molar or mass) of the initial templates (N01/N02). In this study, there is a slight difference in amplification efficiency, since for Nn1 = Nn2 the number of target nirS copies (N01) is slightly lower than the number of copies of the internal fragment (N02). In this case, the quantification is still valid assuming that the eff1/eff2 ratio is a constant value and the amplification is in the exponential phase (37). Few points of the standard curve were compared with results obtained in the presence of nontarget DNA from natural water instead of DNA from a marine isolate (Vibrio). The data can be plotted on the curve showing that the PCR efficiencies in the presence of nontarget DNA from a culture strain or from a natural sample are comparable.

Quantification of cytochrome cd1 denitrifiers in water samples or sediment samples was performed using MPN-PCR and cPCR and was compared with the results of counts from classical cultivation techniques. Prior to enumeration, bacteria should be extracted from the sediment without extracting the free DNA which is associated with the sediment itself. In our experiments, due to the comparison of very different methods for the quantification of bacteria, the method of extraction and the concentration of bacteria must not interfere with the cultivation or with the molecular enumeration techniques. Cell damage which could cause an underestimate in the enumeration with culture techniques should be avoided. The addition of detergents such as Tween 80 can lead to an underestimation of 2 orders of magnitude for cultivable bacteria with MPN compared to direct counting (our unpublished results), and ultrasound treatment can lyse cells (14). Vigorous shaking with filtered seawater is used in this study for the extraction of bacteria from sediment. According to Doria and Bianchi (13), about 60% of bacteria extracted from the sediment are from the interstitial water.

In this study, the two molecular techniques tested for quantifying cytochrome cd1 denitrifiers gave very similar results in both environmental samples. In the sediment sample, quantification of denitrifiers by molecular techniques gave bacterial counts 3 orders of magnitude higher than that found with classical cultivation techniques. For water samples, the molecular techniques gave numbers 5- to 10-fold higher than cultivation techniques. In these experiments, enumeration using molecular techniques does not take into account the denitrifiers with the copper nitrite reductase enzyme, whereas cultivation methods count both types of denitrifier. It is difficult to estimate the proportion of cytochrome cd1 denitrifiers among the denitrifying community, since, to our knowledge, no study has been specifically dedicated to this subject. Several authors have, however, noticed that cytochrome cd1 denitrifiers are more numerous among isolated strains (10, 34). In our samples, it is difficult to know whether cytochrome cd1 denitrifiers are a minority or if counting using the culture methods underestimates the number of denitrifiers. Previous studies which have compared enumeration using molecular and classical culture techniques have shown that in some cases the two approaches give similar results (17, 19), but in other cases, authors found varying correlations between DNA assay and CFU counting (15, 27). In contrast, quantification by cPCR has shown a relatively strong correlation with the number of bacteria introduced (20, 21). In this study, we have obtained approximately the same counts using the two quantitative molecular methods, but cPCR seems to be more precise (lower variation of the result) and provides an internal control that corrects the putative variation in the efficiency of the PCR due to the inhibitory compounds present in the environmental samples. The discrepancy in enumerations obtained by classical versus molecular techniques varies with sample type. Differences may be due to the physiological states of natural bacterial communities. Indeed, it is well known that bacteria may be in a viable state but not be cultivable on a specific medium. Using molecular techniques, every bacterium that contains the target DNA, whatever its physiological state, can be counted. Conversely, counts using MPN culture techniques may give varying results due to differences in the physiological state of the bacteria, depending on the sample and the composition of the culture medium.

To follow up these experiments, we can begin by improving the protocol used for the removal of bacteria from the sediment, using one specifically dedicated to DNA studies (11). Then, using the PCR techniques, it will be possible to quantify cytochrome cd1 type denitrifiers in additional environmental samples using our cd3F–cd4R primer set along with new primer sets which allow the amplification of the nitrite reductase gene (nirK). This should enable the quantification of the whole population of denitrifiers and have an important part to play in determining the proportions of different types of denitrifying bacteria in the functional community.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baumann P, Baumann L. The marine gram negative eubacteria: genus Photobacterium, Beneckea, Alteromonas, Pseudomonas and Alcaligenes. In: Mortimer P S, et al., editors. The prokaryotes: a handbook on habitats, isolation and identification of bacteria. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag KG; 1981. pp. 1302–1330. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonin P, Bertrand J C, Giordano G, Gilewicz M. Specific sodium dependence of nitrate reductase in a marine bacterium. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;48:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonin P, Gilewicz M, Rambeloarisoa E, Mille G, Bertrand J C. Effect of crude oil on denitrification and sulfate reduction in marine sediments. Biogeochemistry. 1990;10:161–174. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonin P, Gilewicz M. A direct demonstration of “co-respiration” of oxygen and nitrogen oxides by Pseudomonas nautica: some spectral and kinetic properties of the respiratory components. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;80:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonin P, Rambeloarisoa Ranaivoson E, Raymond N, Chalamet A, Bertrand J C. Evidence for denitrification in marine sediment highly contaminated by petroleum products. Mar Pollut Bull. 1994;28:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonin P. Anaerobic nitrate reduction to ammonium in two strains isolated from coastal marine sediment: a dissimilatory pathway. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;19:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonin P, Omnes P, Chalamet A. Simultaneous occurrence of denitrification and nitrate ammonification in sediments of the French Mediterranean Coast. Hydrobiology. 1998;389:169–182. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braker G, Fesefeldt A, Wittzel K P. Development of PCR primer systems for amplification of nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) to detect denitrifying bacteria in environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3769–3775. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3769-3775.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochran W G. Estimation of bacterial densities by means of the “most probable number.”. Biometrics. 1950;1950(March):105–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyne M S, Arunakumari A, Averill A, Tiedje J M. Immunological identification and distribution of dissimilatory heme cd1 and non-heme copper nitrite reductase in denitrifying bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2924–2931. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.11.2924-2931.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devereux R, Mundfrom G W. A phylogenetic tree of 16S rRNA sequence from sulfate-reducing bacteria in a sandy marine sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3437–3439. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3437-3439.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Don R H, Cox P T, Baker K, Mattick J S. “Touchdown” PCR to circumvent spurious priming during gene amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4008–4009. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doria E V, Bianchi A. Comparison between two methods of bacterial extraction from sediments. C R Acad Sci Paris. 1982;294:467–470. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein S S, Rossel J. Enumeration of sandy sediment bacteria: search for optimal protocol. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1995;117:289–298. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallier-Souliers S, Ducrocq S, Mazure N, Truffaut N. Detection and quantification of degradative genes in soils contamined by toluene. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;20:121–133. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallin S, Lidgren R E. PCR detection of genes encoding nitrite reductase in denitrifying bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1652–1657. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1652-1657.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnsen K, Enger Ø, Jacobsen C S, Thirup L, Torsvik V. Quantitative selective PCR of 16S ribosomal DNA correlates well with selective agar plating in describing population dynamics of indigenous Pseudomonas spp. in soil hot spots. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1786–1789. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1786-1788.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Junst A, Wakabayashi S, Matsubara H, Zumft W G. The nirSTBM region coding for cytochrome cd1-dependent nitrite respiration of Pseudomonas stutzeri consists of a cluster of mono-, di-, and tetraheme proteins. FEBS Lett. 1991;279:205–209. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lechner S, Conrad R. Detection in soil of aerobic hydrogen-oxidising bacteria related to Alcaligenes eutrophus by PCR and hybridization assays targeting the gene of the membrane-bound (NiFe) hydrogenase. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;22:193–206. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S Y, Bollinger J, Bezdicek D, Ogram A. Estimation of the abundance of an uncultured soil bacterial strain by a competitive quantitative PCR method. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3787–3793. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3787-3793.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leser T D. Quantitation of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 (FR1) in the marine environment by competitive polymerase chain reaction. J Microbiol Methods. 1995;22:249–262. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michotey V, Bonin P. Evidence of anaerobic bacterial processes in the water column: denitrification and dissimilatory nitrate ammonification in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1997;160:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omnes P, Slawyk G, Garcia N, Bonin P. Evidence of denitrification and nitrate ammonification in the river Rhône plume (northwestern Mediterranean Sea) Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1996;141:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oppenheimer C, Zobell C E. The growth and viability of sixty-three species of marine bacteria as influenced by hydrostatic pressure. J Mar Res. 1952;11:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reilly K, Attwood T. Detection of Clostridium proteoclasticum and closely related strains in the rumen by competitive PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:907–913. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.907-913.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rontani J F, Bonin P, Volkman J. Production of wax esters during aerobic growth of marine bacteria on isoprenoid compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:221–230. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.1.221-230.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosado A S, Seldin L, Wolters A C, Elsas J D. Quantitative 16S rDNA-targeted polymerase chain reaction and oligonucleotide hybridization for the detection of Paenobacillus azotofixans in soil and the wheat rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;19:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudi K, Skulberg O M, Larsen F, Jakobsen K S. Quantification of toxic cyanobacteria in water by use of competitive PCR followed by sequence-specific labelling of oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2639–2643. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2639-2643.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shapleigh P J, Payne W J. Differentiation of cd1 cytochrome and copper nitrite reductase production in denitrifiers. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;26:275–279. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sidhu M K, Rishidbaigi A, Testa D, Liao M J. Competitor internal standard for quantitative detection of mycoplasma DNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;128:207–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward B B, Cockcroft A R, Kilpatrick K A. Antibody and DNA probes for detection of nitrite reductase in sea water. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2285–2293. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-9-2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward B B. Diversity of culturable denitrifying bacteria. Limits of rDNA RFLP analysis and probe for the functional gene, nitrite reductase. Arch Microbiol. 1995;163:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe K, Yamamoto S, Hino S, Harayama S. Population dynamics of phenol-degrading bacteria in activated sludge determined by gyrB-targeted quantitative PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1203–1209. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1203-1209.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye R, Arunakumari A, Averill B A, Tiedje J M. Mutants of Pseudomonas fluorescens deficient in dissimilatory nitrite reduction are also altered in nitric oxide reduction. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2560–2564. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2560-2564.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zachar V, Thomas R, Goustin A. Absolute quantification of target DNA: a simple competitive PCR for efficient analysis of multiple samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2017–2018. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.8.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zumft W G, Gotzman D J, Kroneck P M H. Type 1 blue copper proteins constitute a respiratory nitrite-reducing system in Pseudomonas aureofaciens. Eur J Biochem. 1987;168:301–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]