Abstract

The challenges of managing varices during the COVID-19 pandemic are reviewed, and a treatment algorithm is presented to best manage patients with advanced liver disease during periods of limited access to endoscopy.

Keywords: carvedilol, nadolol, pandemic, portal hypertension

Variceal bleeding is a life-threatening complication in patients with cirrhosis and may occur in as many as 40% of patients with compensated cirrhosis and 70% of patients with decompensated cirrhosis (1). Evaluation and subsequent intervention to prevent either a first bleed (primary prophylaxis) or recurrent bleeding (secondary prophylaxis) play a critical role in the outcome for patients with cirrhosis. Current recommendations from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) suggest a screening endoscopy in high-risk patients and, depending on the presence of decompensation, size of the varices, and presence of high-risk stigmata, recommend the use of either variceal ligation or non-selective beta blockers (NSBBs) for primary prophylaxis to prevent bleeding. After a variceal bleed, both therapies are used in combination for secondary prophylaxis (2).

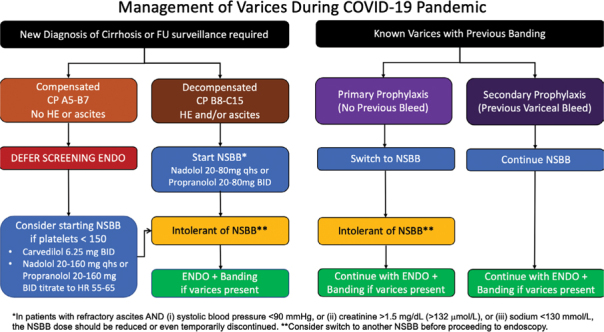

With the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic, most gastrointestinal professional societies, including the American Gastroenterology Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, American College of Gastroenterology, and AASLD have recommended that endoscopy be performed only in urgent situations to reduce the potential risk of COVID-19 infection to either the patient or health care providers involved in endoscopy (3–5). Acute variceal bleed is considered an urgent indication for endoscopy, but the role of upper endoscopy and variceal ligation in either primary or secondary prophylaxis is less clear (4,6,7). Trying to reduce the risk of hospitalization of patients with advanced liver disease during this pandemic is critical, given the potential worse prognosis of these patients. As such, we have developed provincial guidelines to manage varices in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, balancing the risks of performing elective outpatient procedures and the risk of variceal bleeding (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Suggested management of varices during COVID-19 pandemic

No Known Varices

In patients who have no known varices or who have had a previous screening endoscopy with no clinically significant varices, we recommend that screening endoscopy be deferred because the risk of endoscopy outweighs the benefit. Given that it is unlikely that transient or shear wave elastography will be readily available during the pandemic, for patients who are compensated, consideration could be given to starting an NSBB (eg, nadolol, propranolol) or carvedilol if their platelets are less than 150 × 109/L. The threshold platelet count of 150 x 109/L was selected on the basis of unpublished data from the ANTICIPATE study (8), showing that the risk of varices needing treatment substantially increased with a platelet count below 150 × 109/L (see Supplementary Material).

We feel that patients who are decompensated without previous banding should be empirically started on a NSBB or carvedilol, given the high likelihood of varices and the potential risk of upper endoscopy. If the initial agent is not tolerated, we would suggest a trial of an alternative medication (2,9). If a patient is intolerant to all NSBBs and carvedilol, endoscopy can be considered. See Table 1 for details regarding NSBB and carvedilol.

Table 1:

Medical management of varices

| Medication | Starting dose | Maximum dose | Treatment target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nadolol | 20–40 mg qhs Increase every 3 days until at goal |

160 mg/day without ascites 80 mg/day with ascites |

Resting heart rate of 55–65/min SBP >90 |

| Propranolol | 20–160 mg twice daily Increase every 3 days until at goal | 320 mg/day without ascites 160 mg/day with ascites |

Resting heart rate of 55–65/min SBP >90 |

| Carvedilol | 6.25 mg daily | 6.25 mg twice daily Avoid in refractory ascites | SBP >90 |

Note: Consider reduction/temporary discontinuation of agent in patients with refractory ascites if (a) SBP <90, (b) serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dL (>132 mmol/L), or (c) sodium <130 mmol/L.

SBP = Systolic blood pressure; qhs = every night at bedtime

Known Varices

For patients who have known varices and have not had a previous variceal bleed, stopping the banding program and switching to a NSBB would be the lowest risk option, given that the data are unclear as to whether variceal banding or NSBB is superior for primary prophylaxis (2). If the patient is intolerant to all NSBBs, endoscopy with variceal ligation can be considered. Patients who have had a previous variceal bleed should continue on their NSBB, because NSBBs are a key component of reducing the risk of repeat variceal bleeding during secondary prophylaxis (10). The variceal banding program should continue because the risk of recurrent bleeding is significantly elevated, and the benefits of endoscopy outweigh the risks.

Triage of Patients with Potential Reduction of Endoscopy Access

Depending on the local burden of COVID-19, endoscopy resources may be more or less limited. As access to endoscopy diminishes, the patients at highest risk of having a variceal bleed should be given the highest priority for endoscopy.

We would prioritize groups for whom the benefit of endoscopy outweighs the risk of COVID-19 infection as follows: (1) recent variceal bleed, secondary prophylaxis; (2) decompensated cirrhosis, intolerant of NSBB; and (3) compensated cirrhosis, intolerant of NSBB. As the need to cancel or defer elective procedures increases, this prioritization can help with the triage process.

Supplementary Material

Unpublished data from the ANTICIPATE study (8), showing that the risk of varices needing treatment substantially increased with platelet count below 150 x 109 (kindly provided by the authors of the ANTICIPATE study).

Funding Statement

Funding: None to declare.

Footnotes

FU = Follow-up; HE = Hepatic encephalopathy; ENDO = Endoscopy; NSBB = Non-selective beta blocker

Ethics Approval:

N/A

Informed Consent:

N/A

Registry and Registration No. of The Study/Trial:

N/A

Funding:

None to declare.

Disclosures:

Dr Congly reports grants from Gilead Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genfit, and Sequana Medical and personal fees from Intercept Pharmaceuticals and Eisai outside the submitted work; Dr Sadler reports grants from Gilead Sciences, CymaBay, and Eiger and personal fees from AbbVie outside the submitted work; Dr Abraldes reports grants from Gilead and personal fees from Gilead, Pfizer, Intercept, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lupin Pharma Canada, and Genfit outside the submitted work; Dr Tandon reports personal fees from Lupin Pharma Canada outside the submitted work; Dr Lee reports grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, and Merck and personal fees from London Drugs, Pendopharm, and Oncoustics outside the submitted work; Dr Burak has nothing to disclose.

Peer Review:

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kovalak M, Lake J, Mattek N, Eisen G, Lieberman D, Zaman A. Endoscopic screening for varices in cirrhotic patients: data from a national endoscopic database. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(1):82–8. 10.1016/j.gie.2006.08.023. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65(1):310–35. 10.1002/hep.28906. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bezerra JA, El-Serag HB, Pochapin MB, Vargo, JJ II. Joint GI Society message: COVID-19 clinical insights for our community of gastroenterologists and gastroenterology care providers. https://www.aasld.org/about-aasld/media/joint-gi-society-message-covid-19-clinical-insights-our-community (Accessed April 5, 2020).

- 4.American Association for the Study of Liver Disease COVID-19 Working Group. Clinical insights for hepatology and liver transplant providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/AASLD-COVID19-ClinicalInsights-4.07.2020-Final.pdf (Accessed April 5, 2020).

- 5.Repici A, Maselli R, Colombo M, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: what the department of endoscopy should know. Gastrointest Endosc. Forthcoming 2020. 10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tse F, Borgaonkar M, Leontiadis GI. COVID-19: advice from the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology for endoscopy facilities, as of March 16, 2020. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2020. Mar 27 [cited 2020 Apr 5]. 10.1093/jcag/gwaa012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro Filho EC, Castro R, Fernandes FF, Pereira G, Perazzo H. Gastrointestinal endoscopy during COVID-19 pandemic: an updated review of guidelines and statements from international and national societies. Gastrointest Endosc. Forthcoming 2020. 10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraldes JG, Bureau C, Stefanescu H, et al. Noninvasive tools and risk of clinically significant portal hypertension and varices in compensated cirrhosis: The “Anticipate” study. Hepatology. 2016;64(6):2173–84. 10.1002/hep.28824. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosch J, Abraldes JG, Groszmann R. Current management of portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2003;38(Suppl 1):S54–68. 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00430-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albillos A, Zamora J, Martínez J, et al. Stratifying risk in the prevention of recurrent variceal hemorrhage: results of an individual patient meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;66(4): 1219–31. 10.1002/hep.29267. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Unpublished data from the ANTICIPATE study (8), showing that the risk of varices needing treatment substantially increased with platelet count below 150 x 109 (kindly provided by the authors of the ANTICIPATE study).