Abstract

Background

Infectious diseases (ID) physicians are important for hepatitis C virus (HCV) care delivery in Canada. Our study describes their current and intended patterns of practice, attitudes, and barriers to care.

Methods

The study population includes 372 practicing ID physicians who are members of the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease (AMMI) Canada. A random sample from each province was invited to participate in a web-based survey. Our outcome of interest was level of HCV care provided, and related intentions for the next 12 months. Additional survey domains included attitudes toward treatment and perceived barriers to care.

Results

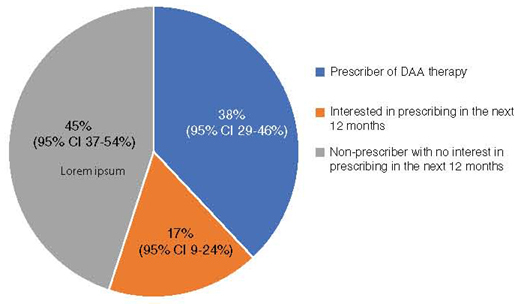

Of 205 invitations to complete the survey, 64 (31%) physicians responded to the full survey and 81 to an abbreviated survey on the main outcomes of interest (overall response rate 71%). After adjusting for non-response, we estimate that 38% (95% CI 29% to 46%) are prescribing direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy, and 17% (95% CI 9% to 24%) are interested in starting to prescribe. Of full survey respondents, 100% of prescribers and 79% of non-prescribers agreed that people who inject drugs should be offered DAA therapy. Common barriers to care include patients’ competing priorities, mental health comorbidities, poor access to harm reduction services, and insufficient physician training.

Conclusions

A large proportion of Canadian ID physicians are not currently prescribing DAA therapy for HCV. While some of these physicians are interested in starting to prescribe, we need strategies to improve physician training and address other barriers to care as provincial restrictions on DAA eligibility are being eliminated.

Keywords: barriers to care, direct-acting antiviral therapy, hepatitis C virus, infectious diseases physicians, patterns of practice

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has targeted eliminating hepatitis C virus (HCV) as a major public health threat by 2030. Reaching the 2030 target will require diagnosing 90% of people living with HCV and treating 80% of diagnosed people with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy, along with drastically reducing new HCV infections (1). Although a diagnosis gap remains in Canada, with at least 21% of prevalent chronic HCV undiagnosed (2), the major gap in reaching these elimination targets is the large number of the estimated 250,000 Canadians with chronic HCV who have yet to be treated (3).

The landscape for hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment is rapidly changing. The simplicity of efficacious, safe, all oral DAA therapy greatly expands the array of health providers that could offer HCV treatment. In February 2017, the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance secured a new pricing agreement with leading pharmaceutical companies, making DAAs more affordable for public health plans in Canada. Reduced prices will allow the removal of a major barrier to scaling up treatment—fibrosis restrictions (4)—thus broadening the types of patients who can be treated, provided there are sufficient numbers of physicians able and willing to do so.

Canadian HCV practice guidelines have called for improving the treatment capacity for HCV (5). During the interferon era, a limited subset of Canadian physicians was engaged in HCV care. For example, among gastroenterology, hepatology, and infectious diseases (ID) physicians, only 43% of respondents to a national survey reported providing HCV treatment services, and the majority (77%) were either gastroenterologists or hepatologists (6). Only 28% of ID physicians who responded to the survey provided HCV treatment, suggesting there is potential to scale up treatment provision among this group.

ID physicians are particularly well suited to prescribe HCV DAA therapy, since many have experience with the key populations affected, and are accustomed to combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection. However, many feel unprepared to manage HCV. A survey of American ID physicians, conducted as the first DAA therapies were approved, found that only 54% evaluate or treat HCV, and the majority (61%) felt that they did not receive adequate training to manage HCV (7). Additional challenges for scaling up treatment include negative attitudes toward treating people who inject drugs (PWID) (6), and inconsistent application of clinical practice guidelines (8).

The aim of our survey was to investigate current and anticipated HCV practice patterns, attitudes toward and perceived barriers to treatment among Canadian ID physicians. We hypothesized that the majority of these physicians are not prescribing DAA therapy, but that there is a subset who is interested in starting. The information collected in this study will help guide how to build capacity for HCV treatment in Canada.

Methods

Survey design

Data for this study were collected using a web-based survey with response-guided questions involving true/false, multiple choice, and short answer responses. The survey instruments are available as Supplement files. The survey was offered in English and French. Survey development was based on reviewing (a) available published HCV surveys of physicians (9–13), (b) current Canadian screening and treatment guidelines (5), and (c) a conceptual framework on factors affecting practice guideline adherence (9). Content and face validity of the survey instrument was optimized by soliciting feedback from HCV treaters as well as physicians who do not manage or treat HCV (six ID physicians, one addiction medicine physician, and one family physician).

Sampling population

The study population included practicing ID and medical microbiology physicians who are members of the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease (AMMI) Canada, the largest national specialty association that represents physicians and researchers specializing in medical microbiology and infectious diseases. Total membership is 655, including retired members, non-practicing members, and members in training, such as residents and fellows. According to the latest Canadian Medical Association data, there were 641 medical microbiology and ID physicians in Canada in 2016 (14). Of the 372 active members of AMMI Canada who are practicing ID physicians, located in Canada, and consented to receiving surveys (all but 31 members), we selected a random sample of 205 members. Random sampling was stratified by province, with a sample of 40 from each province. For provinces with fewer than 40 members, we included the entire provincial membership.

The study was approved by the Ethics Board of the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre in Montreal, Québec. Study protocols to protect respondent anonymity and privacy were explained to all potential participants, and no personally identifiable information was collected. Participant completion of the survey was accepted as informed consent to participate in the study.

Survey domains

All respondents were asked questions about their demographics and practice characteristics, and awareness and agreement regarding recommended HCV screening and treatment practices. Respondents were also surveyed on perceived barriers to care, attitudes toward the care of PWID, and preferred ways to receive educational updates on HCV.

The following were the main outcomes of interest with their corresponding survey items, assessed in both the full survey and two-question survey (described in Survey Administration section of this article):

Level of HCV care provided. All respondents were asked to indicate whether they prescribe HCV DAA therapy (referred to as “prescribers”) or not (referred to as “non-prescribers”) (two categories).

- Intentions regarding HCV care in the next 12 months.

- Prescribers were asked about whether they would treat more, the same, or fewer HCV patients (three categories).

- Non-prescribers were asked whether they were interested in starting to prescribe DAA therapy (yes or no).

Survey administration

An initial e-mail invitation to complete the survey was sent by AMMI Canada. Thereafter, three follow-up reminder requests were sent. If there was no response after the reminder emails, physicians were encouraged to respond to a short, two-question survey instead, which measured the main outcomes of interest described in the survey domains section of this article. Each participant who completed the full survey received a $50 Amazon gift card, while respondents to the two-question survey received a $10 Amazon gift card. These strategies were designed to maximize the overall response rate and mitigate the effects of non-response bias, especially for the main outcomes of interest.

Statistical analysis

We report proportions for responses to selected survey questions. All estimates were weighted to reflect the stratified sample. We combined smaller provinces into regional strata, in order to generate more stable estimates. Saskatchewan and Manitoba were combined into a “Prairie province” stratum, while Newfoundland, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia were combined into an “Atlantic province” stratum. We calculated 95% confidence intervals for our main outcomes (described in the section on survey domains) using data from the two-question survey to adjust estimates for non-response, assuming that those answering these two questions were a random sample of non-respondents (15). Our calculations were carried out using the Survey Means procedure in SAS 9.4.

Results

The survey was open from January 11 to February 15, 2018. Of the 205 invited members, 64 responses to the full survey were received (31% response rate). We also received 81 responses to our two-question survey, yielding an overall response rate of 71% on the main outcomes of interest. The highest response rate was from New Brunswick (100%) and the lowest response rate from Québec (65%).

Patterns of practice and readiness to prescribe DAA therapy

Among full survey participants, 58% (95% CI 44% to 72%) are current prescribers of DAA therapy, and 18% (95% CI 5% to 30%) are interested in prescribing in the next 12 months. Among current prescribers, 62% intend to treat more HCV patients, 35% intend to treat the same number of patients, and 3% intend to treat fewer patients, in the next 12 months. In marked contrast, only 17% (95% CI 11% to 23%) of respondents to the two-question survey prescribe DAA therapy, and 16% (95% CI 8% to 23%) are interested in prescribing in the next 12 months. Given the difference in proportions of prescribers responding to the two survey types, there is a potential for considerable non-response bias in answers from the full survey. Assuming that respondents of the two-question survey are likely to be more representative of non-respondents than respondents of the full survey, we adjusted for non-response and estimate that 38% (95% CI 29% to 46%) of our study population are current prescribers of DAA therapy and 17% (95% CI 9% to 24%) are interested in prescribing in the next 12 months (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Estimates of current and anticipated patterns of HCV care among actively practicing Canadian ID physicians.

ID = infectious diseases

Full survey results

Demographics and practice characteristics

Demographic characteristics and practice characteristics of the full survey respondents are shown in Table 1. Age groups were broken down into the categories < 40 years, 40–59 years, and > 60 years. Forty-nine percent of respondents were female, and there was a balance between those completing training before 2001, between 2001–2010, and after 2010. The vast majority practised in urban, academic-affiliated centres. Non-prescribers were more often female, completed their training before 2001 and are salaried. In the last year, non-prescribers cared for fewer HCV-infected patients on average and were less likely to have PWID in their care than prescribers.

Table 1:

Characteristics and patterns of practice of full survey respondents

| Characteristic/pattern of practice | All respondents (N = 64) |

Non-prescribers (N = 28) |

Prescribers (N = 36) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent characteristics, weighted % of respondents | |||

| Age, y | |||

| < 40 | 33 | 23 | 48 |

| 40–59 | 59 | 68 | 46 |

| ≥ 60 | 9 | 10 | 6 |

| Female | 49 | 67 | 34 |

| Post-graduate training completion | |||

| After 2010 | 32 | 23 | 39 |

| 2001–2010 | 25 | 22 | 28 |

| Before 2001 | 43 | 56 | 33 |

| Location | |||

| Urban | 87 | 100 | 78 |

| Suburban | 9 | 0 | 16 |

| Rural | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| Has an academic affiliation | 92 | 100 | 91 |

| Method of compensation | |||

| Fee-for-service | 61 | 62 | 57 |

| Salary | 56 | 73 | 43 |

| Sessional (i.e., by hour or day) | 20 | 18 | 23 |

| Combination | 37 | 53 | 26 |

| Number of patients cared for in the past year, weighted % of respondents | |||

| HCV monoinfection | |||

| None | 5 | 13 | 0 |

| 1–10 | 19 | 41 | 5 |

| 11–50 | 47 | 34 | 55 |

| > 50 | 29 | 12 | 40 |

| HIV-HCV coinfection | |||

| None | 23 | 28 | 3 |

| 1–10 | 40 | 32 | 42 |

| 11–50 | 32 | 37 | 37 |

| > 50 | 6 | 3 | 18 |

| PWID | |||

| None | 9 | 22 | 2 |

| 1–10 | 25 | 27 | 12 |

| 11–50 | 25 | 32 | 27 |

| > 50 | 41 | 18 | 59 |

HCV = hepatitis C virus; HIV-HCV = human immunodeficiency virus – hepatitis C virus; PWID = people who inject drugs

Training

Overall, 53% of respondents feel sufficiently trained to prescribe DAA therapy. The percentage who reported feeling sufficiently trained did not vary much by when post-graduate training was completed (e.g. 57% and 53% of those completing training after 2010 and before 2001, respectively). Of all respondents, prescribers reported feeling sufficiently trained much more frequently than non-prescribers (75% of prescribers vs. 21% of non-prescribers). We then compared those who feel sufficiently trained versus those who do not feel sufficiently trained. Overall, those who feel sufficiently trained more frequently reported managing > 10 HCV-infected patients in the past year (97% vs. 51%), and prescribing DAA therapy (82% vs. 28%), compared to those who do not feel sufficiently trained. However, few survey respondents (24% of prescribers and 2% of non-prescribers) feel adequately trained to manage patients with substance abuse issues.

Respondents identified a number of preferred methods of receiving information updates on HCV, with the most popular methods being published guidelines (86%), live seminars (77%), and online self-directed learning courses (57%).

Screening patterns

All respondents perform HCV screening as part of their practice (Table 2). All respondents would perform one-time screening on patients who have ever used injection drugs. Almost all respondents would perform annual screening on patients who report using injection drugs during the past year and on HIV-positive men who report engaging in condomless sex with men. The majority (73%) support one-time screening of the birth cohort of patients born between 1945–1975, with 83% of prescribers and 62% of non-prescribers agreeing with this practice. There were few respondents who endorse universal one-time screening (3%).

Table 2:

Screening practices of full survey respondents (N = 64)

| Patient population to be screened | Respondents who answered “yes” (%)* |

|---|---|

| Which patients would you test for HCV at least once (one-time screening)? | |

| Every patient | 3 |

| Patients who have used injection drugs | 100 |

| Children born to HCV-positive mothers | 89 |

| Patients who were born, travelled, or resided in HCV-endemic countries | 89 |

| Patients who are HIV-positive | 95 |

| Patients on hemodialysis | 90 |

| Patients who have been in prison | 98 |

| Recipients of an organ transplant or blood product transfusion before 1992 in Canada | 99 |

| All patients born between 1945–1975 | 73 |

| Patients who have had a needle-stick injury | 100 |

| Which patients would you test for HCV at least once a year (annual screening)? | |

| Patients using injection drugs during the past year | 97 |

| Patients using intranasal illicit drugs during the past year | 81 |

| HIV-positive men who have condomless sex with men | 95 |

* Weighted % of respondents who answered “yes” to the given question

HCV = hepatitis C virus; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Barriers to care

Both prescribers and non-prescribers noted that co-morbid mental health problems and competing medical or social priorities are important patient-related barriers to care (Table 3). At the health system level, non-prescribers note insufficient HCV training for support staff (e.g. nursing and administrative staff) (54% of respondents), and physicians (52%) as important barriers. On the other hand, prescribers identified poor access to harm reduction services (55% of respondents) and mental health treatment (45% of respondents) for patients most frequently.

Table 3:

Most common barriers to care identified by full survey respondents (N = 64)

| Barrier to care | Non-prescribers (N = 28) (%)* | Prescribers (N = 36) (%)* |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-related barriers | ||

| Patients have other more urgent medical or social priorities. | 61 | 40 |

| Patients have mental health problems that limit their ability to engage in HCV care. | 51 | 63 |

| Patients continue to use injection drugs. | 31 | |

| Patients are poorly adherent to lab or clinic appointments. | 29 | |

| Health system-related barriers | ||

| I have not had enough training to provide good HCV care. | 52 | |

| I have insufficient or inadequately trained support staff (e.g., nursing and administrative staff). | 54 | |

| Patients have poor access to mental health treatment (e.g., psychiatry, psychology, and social work). | 43 | 45 |

| Provincial restrictions on HCV treatment eligibility make it difficult for me to treat my patients. | 41 | |

| Patients who use injection drugs have poor access to harm reduction services or opioid substitution therapy. | 55 | |

* Weighted % of respondents who rated the given statement as “very important” or “most important”

HCV = hepatitis C virus

Attitudes toward people who inject drugs (PWID)

Most respondents have favourable attitudes toward treating PWID (Table 4). All prescribers and 79% of non-prescribers agree that patients with HCV who are actively injecting drugs should be offered HCV treatment, along with linkage to harm reduction services and opioid substitution therapy. Regarding PWID who become reinfected with HCV, 83% of prescribers and 60% of non-prescribers agree that they should be candidates for retreatment of HCV.

Table 4:

Perceptions and attitudes of full survey respondents toward the care of people who inject drugs (N = 64)

| Perception or attitude | Non-prescribers (N = 28) (%)* | Prescribers (N = 36) (%)* |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with HCV who actively inject drugs should be offered treatment for HCV, and linked to harm reduction services or opioid substitution therapy. | 79 | 100 |

| HCV treatment is less likely to be successful if patients continue to use injection drugs. | 55 | 35 |

| If patients who actively inject drugs are treated for HCV, they will just get reinfected. | 5 | 24 |

| Patients who become reinfected with HCV should be candidates for retreatment. | 60 | 83 |

| I have received adequate training to manage patients who have drug abuse issues. | 2 | 24 |

| The time and resources required to care for patients with drug abuse issues discourage me from caring for more of these patients in my clinic. | 29 | 37 |

* Weighted % of respondents who rated the given statement as “agree” or “strongly agree”

HCV = hepatitis C virus

Discussion

In this national survey of practicing ID physicians who are members of AMMI Canada, we found that a large proportion of respondents (62%) are not currently prescribing DAA therapy for HCV, and relatively few non-prescribers are interested in starting to prescribe. In general, non-prescribers follow fewer patients with HCV, which may explain in part why they are not involved in DAA treatment. However, the main issue appears to be that most non-prescribers do not feel sufficiently trained to prescribe DAAs. Indeed, a large proportion of recent ID training graduates who responded to our survey do not feel sufficiently trained. ID fellowship training programs may need to include more training on recent developments in HCV management and treatment. Non-prescribers frequently noted that their support staff also have inadequate training to support HCV care. Those who are interested in treating highlight the need for additional training. Given 46% and 40% of non-prescribers follow more than 10 HCV mono-infected and co-infected patients, respectively, per year, there is a large group of ID physicians that could potentially serve to augment the workforce providing HCV care in Canada, provided they were trained to do so. Respondents indicated they would like to receive such training through a variety of means, such as published guidelines, live seminars, and online learning courses. While most non-prescribers indicated the need for more HCV training, this training should be designed to meet the needs of both prescribers and non-prescribers, since a significant proportion of prescribers (25%) also indicated that they do not feel sufficiently trained. The use of some forms of social media may help encourage more physicians to engage with evidence-based continuing medical education resources (16). Training also needs to extend to support staff, such as nursing and administration, given that lack of adequately trained staff was identified as a significant barrier to providing treatment.

Screening for HCV infection does not appear to be an area of significant disagreement among ID physicians. Reported HCV screening practices among full survey respondents include the patient risk groups identified by the recent Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care screening recommendations (17). In addition, the majority agree with one-time screening of the 1945–1975 birth cohort, and most would perform annual screening for those with ongoing HCV parenteral and sexual exposure risks, even though these screening practices are not part of the Canadian Task Force recommendations.

While provincial restrictions on HCV treatment eligibility remain a barrier to care, these are progressively being eliminated. Québec removed any restrictions in March 2018, while Ontario and British Columbia have announced removal of fibrosis restrictions within the next year (18). The easing of restrictions was facilitated by lowered DAA pricing negotiated by the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance, announced in February 2017 (19). Expanding treatment to patients in early stages of HCV may particularly enhance the role of ID physicians in DAA therapy, as patients with more advanced liver disease generally require care by hepatologists and gastroenterologists.

Other barriers to care may be less easily overcome, such as patients having more urgent medical or social priorities. Studies during the current DAA therapy era have found that recent active drug use is associated with a lower odds of initiating HCV therapy (20–21). Injection drug use has been identified as independently associated with severe food insecurity in the HIV-HCV co-infected population (22), so securing access to food may be a more urgent priority than seeking HCV treatment for some patients. Poor access to mental health treatment and harm reduction services was also identified by survey respondents as a significant barrier to HCV care, which may be a challenging health system-related barrier to address.

However, the attitudes of ID physicians toward PWID appear to be highly favourable. Among our respondents, all DAA prescribers, and most non-prescribers, would support prescribing DAA therapy to patients who are actively injecting drugs—a key population that has been under-treated and for whom treatment will need to be scaled up to meet elimination targets set out by the WHO. This is a particularly encouraging finding given that a national survey, conducted before the DAA era, among a group consisting mostly of gastroenterologists and hepatologists, found that fewer than 20% would prescribe HCV treatment to PWID using needle and syringe exchange services (6). The attitudes observed in our study may be influenced by newer HCV guidelines encouraging the treatment of PWID (23), improved tolerability and shorter duration of DAA therapy, and growing evidence that treating PWID for HCV can be highly successful. For example, a recent clinical trial demonstrated high SVR rates of DAA therapy in people with recent injection drug use (24). ID physicians also report caring for a large number of PWID, particularly those who are currently prescribing DAAs. However, most prescribers, and nearly all non-prescribers, feel they have not received adequate training to manage patients who have substance abuse issues. Therefore, in addition to increasing training related to DAA treatment, providing more training in addiction medicine and engaging more addiction physicians in HCV care is needed. We are planning a similar survey of Canadian addiction physicians to assess interest and readiness to manage HCV.

Our study has limitations. Although the overall response rate was high (71%), only 31% responded to the full survey. Non-response bias therefore may be important and could limit the generalizability of our results. It is likely that the full survey respondents are representative of physicians who are more involved and interested in HCV care, and practice in urban, academic centres, compared to non-respondents. Knowledge and interest in providing DAA therapy may be lower among Canadian ID physicians practicing in rural, non-academic settings, and in certain provinces with lower response rates. We were able to use the two-question survey responses to reasonably estimate the proportion of DAA prescribers in our target population by correcting for non-response bias. This may be a promising strategy to adopt for future studies, due to the low response rate often observed in physician web-based surveys. Given that a high percentage of surveyed physicians did not wish to complete the full survey despite repeated reminders and financial incentives, shorter surveys or alternative ways of obtaining key information related to provision of DAA treatment should be used in future studies. Some basic information on those not responding to a full survey might also be collected to better characterize this group. Future studies should further explore specific training deficiencies to help guide development of training interventions. These strategies may be useful when considering surveying other groups who might potentially be interested in providing HCV care (e.g. addiction physicians, family physicians, and nurse practitioners).

Conclusions

Among respondents to our survey of Canadian ID physicians, a large proportion are not currently prescribing HCV DAA therapy. While some would like to start prescribing DAA therapy, most do not feel sufficiently trained to do so. Given appropriate training, this modifiable barrier to scaling up DAA treatment could be addressed. ID physicians, many of whom are caring for key populations affected by HCV, represent a pool of potential prescribers who could help expand HCV treatment capacity in Canada, especially as provincial treatment eligibility criteria are broadened.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the MMI Canada leadership and staff Caroline Quach, Riccarda Galioto, Paul Glover, and Melanie Desjardins for their assistance in survey distribution. We thank Chantal Burelle for assistance with French translation.

This article is part of a special topic series commissioned by the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C (CanHepC). CanHepC is funded by a joint initiative of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (NHC-142832) and the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Funding Statement

Gift cards for respondents were funded by unrestricted grants from Merck Canada and Gilead Canada.

Funding:

Gift cards for respondents were funded by unrestricted grants from Merck Canada and Gilead Canada. Both entities had no role in the conception and design of the survey, or publication of the data. J Chan was supported by a post-doctoral trainee award from the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C (CanHepC).

Disclosures:

J Cox has received consulting fees from ViiV Healthcare, Gilead and Merck; grants from ViiV Healthcare, Gilead and Merck; and payment for lectures from Gilead. MB Klein has received grants for investigator-initiated trials from ViiV Healthcare and Merck, as well as consulting fees from ViiV Healthcare, Merck, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, and AbbVie. J Chan, R Nitulescu, and J Young have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.WHO. Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016–2021. 2016. http://www.who.int/hepatitis/strategy2016-2021/ghss-hep/en/ (March 18, 2018).

- 2.Shah HA, Heathcote J, Feld JJ. A Canadian screening program for hepatitis C: is now the time? CMAJ. 2013;185(15):1325–8. 10.1503/cmaj.121872. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myers RP, Krajden M, Bilodeau M, et al. Burden of disease and cost of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(5):243–50. 10.1155/2014/317623. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall AD, Saeed S, Barrett L, et al. Restrictions for reimbursement of direct-acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in Canada: a descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4(4):E605–14. 10.9778/cmajo.20160008. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers RP, Shah H, Burak KW, Cooper C, Feld JJ. An update on the management of chronic hepatitis C: 2015 consensus guidelines from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29(1):19–34. 10.1155/2015/692408. Medline:. Erratum in: Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29(2):68. Corrected at: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myles A, Mugford GJ, Zhao J, Krahn M, Wang P. Physicians’ attitudes and practice toward treating injection drug users with hepatitis C virus: results from a national physician survey in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25(3):135–9. 10.1155/2011/810108. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chastain CA, Beekmann S, Wallender EK, Hulgan T, Stapleton JT, Polgreen PM. Hepatitis C management and the infectious diseases physician: a survey of current and anticipated practice patterns. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(5):792–4. 10.1093/cid/civ384. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young J, Potter M, Cox J, et al. Variation between Canadian centres in the uptake of treatment for hepatitis C by patients coinfected with HIV: a prospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2013;1(3):E106–14. 10.9778/cmajo.20130009. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox J, Graves L, Marks E, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours associated with the provision of hepatitis C care by Canadian family physicians. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18(7):e332–40. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01426.x. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joukar F, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Soati F, Meskinkhoda P. Knowledge levels and attitudes of health care professionals toward patients with hepatitis C infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(18):2238–44. 10.3748/wjg.v18.i18.2238. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naghdi R, Seto K, Klassen C, et al. A hepatitis C educational needs assessment of Canadian healthcare providers. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:5324290. 10.1155/2017/5324290. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parkes J, Roderick P, Bennett-Lloyd B, Rosenberg W. Variation in hepatitis C services may lead to inequity of health-care provision: a survey of the organization and delivery of services in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:3. 10.1186/1471-2458-6-3. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson M, Konerman MA, Choxi H, Lok AS. Primary care physician perspectives on hepatitis C management in the era of direct-acting antiviral therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(12):3460–8. 10.1007/s10620-016-4097-2. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Medical Association. Medical microbiology & infectious diseases profile. 2016. https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/profiles/medical-microbiology-e.pdf (March 4, 2018).

- 15.Bethlehem JG, Kersten HM. On the treatment of nonresponse in sample surveys. J Off Stat. 1985;1(3):287–300. http://www.scb.se/contentassets/ca21efb41fee47d293bbee5bf7be7fb3/on-the-treatment-of-nonresponse-in-sample-surveys.pdf (October 26, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn S, Hebert P, Korenstein D, Ryan M, Jordan WB, Keyhani S. Leveraging social media to promote evidence-based continuing medical education. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0168962. 10.1371/journal.pone.0168962. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grad R, Thombs BD, Tonelli M, et al. Recommendations on hepatitis C screening for adults. CMAJ. 2017;189(16):E594–E604. 10.1503/cmaj.161521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CATIE. Improved access to hepatitis C treatment coming to B.C. and Ontario. 2017. http://www.catie.ca/en/catienews/2017-03-06/improved-access-hepatitis-c-treatment-coming-bc-and-ontario (February 6, 2018).

- 19.Cision. A statement from the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance. 2017. https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/a-statement-from-the-pan-canadian-pharmaceutical-alliance-614373463.html (4 March 2018).

- 20.Wansom T, Falade-Nwulia O, Sutcliffe CG, et al. Barriers to hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment initiation in patients with human immunodeficiency virus/HCV coinfection: lessons from the interferon era. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(1):ofx024. 10.1093/ofid/ofx024. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saeed S, Strumpf EC, Moodie EE, et al. Disparities in direct acting antiviral uptake in HIV-hepatitis C co-infected populations in Canada. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(3):e25013. 10.1002/jia2.25013. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLinden T, Moodie EE, Hamelin A-M, et al. Injection drug use, unemployment, and severe food insecurity among HIV-HCV co-infected individuals: a mediation analysis. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:3496–3505. 10.1007/s10461-017-1850-2. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). When and in whom to initiate HCV therapy. 2017. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/evaluate/when-whom (February 6, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grebely J, Dalgard O, Conway B, et al.; SIMPLIFY Study Group. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for hepatitis C virus infection in people with recent injection drug use (SIMPLIFY): an open-label, single-arm, phase 4, multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(3):153–61. 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30404-1. Medline:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]