Abstract

Objective

To assess association between Hashimoto thyroiditis (HT) and clinical outcomes of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC).

Methods

Databases including Pubmed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science were searched. Weighed mean differences (WMDs) and odds ratios (ORs) were used to evaluate association between HT and clinical outcomes of PTC, and the effect size was represented by 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity test was performed for each indicator. If the heterogeneity statistic I2≥50%, random-effects model analysis was carried out, otherwise, fixed-effect model analysis was performed. Sensitivity analysis was performed for all outcomes, and publication bias was tested by Begg’s test.

Results

Totally 47,237 patients in 65 articles were enrolled in this study, of which 12909 patients with HT and 34328 patients without HT. Our result indicated that PTC patients with HT tended to have lower risks of lymph node metastasis (OR: 0.787, 95%CI: 0.686–0.903, P = 0.001), distant metastasis (OR: 0.435, 95%CI: 0.279–0.676, P<0.001), extrathyroidal extension (OR: 0.745, 95%CI: 0.657–0.845, P<0.001), recurrence (OR: 0.627, 95%CI: 0.483–0.813, P<0.001), vascular invasion (OR: 0.718, 95%CI: 0.572–0.901, P = 0.004), and a better 20-year survival rate (OR: 1.396, 95%CI: 1.109–1.758, P = 0.005) while had higher risks of multifocality (OR: 1.245, 95%CI: 1.132–1.368, P<0.001), perineural infiltration (OR: 1.922, 95%CI: 1.195–3.093, P = 0.007), and bilaterality (OR: 1.394, 95%CI: 1.118–1.739, P = 0.003).

Conclusions

PTC patients with HT may have favorable clinicopathologic characteristics, compared to PTCs without HT. More prospective studies are needed to further elucidate this relationship.

Background

Hashimoto thyroiditis (HT) is a chronic inflammation of the thyroid gland initially described over a century ago, which is now considered the most common autoimmune disease [1, 2]. An incidence is estimated to range from 0.3 to 1.5 cases per 1,000 people, with a prevalence of 5–10% in the overall population [3]. HT is characterized by hypothyroidism, the presence of serum antithyroglobulin and antiperoxidase antibodies, and widespread lymphocytic infiltration with depletion of follicular cells [4, 5]. Thyroid cancer (TC) is the most common malignancy of the endocrine system, with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) being the most prevalent form that accounts for 80% of all diagnosed TCs [6]. The incidence of PTC and HT is rapidly increasing in many countries [7, 8]. The disease of PTC coexisted with HT presents an increasing trend year by year [9]. The coexistence of these two diseases has also been reported to range from 10% to 58% [10, 11], which has aroused great concern.

The relationship between HT and PTC was investigated in several studies. Coexistent HT has been reported to be significantly associated with the less aggressive clinicopathologic characteristics of PTC [10, 12]. Whereas several scholars observed HT is associated with a significantly increased risk of PTC [13]. Other studies have shown no connection between the presence of HT and PCT [14, 15]. Moreover, the association with prognosis between HT and PC remains unclear. It is uncertain whether coexisting with HT in PTC represents a good prognosis or is simply the concurrence of both diseases. It is therefore reasonable to further evaluate the association between HT and PTC.

Herein, we conducted a meta-analysis with a multitude of outcome assessments included to explore the association between HT and PTC prognosis.

Methods

Search strategy

Published literature search was performed on Pubmed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases from inception to December 11, 2020. The search words were as follows: “Thyroid Cancer, Papillary” OR “Cancer, Papillary Thyroid” OR “Papillary Thyroid Cancer” AND “Hashimoto Disease” OR “Hashimoto Struma” OR “Hashimoto Thyroiditis” OR “Hashimoto Thyroiditides” OR “Autoimmune thyroid disease”. The detailed search terms from PubMed are listed in S1 File.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) studies with patients with PTC; (2) studies including patients with HT in the case group, and those without HT in the control group; (3) studies with the latest research results for the same studies by the same authors; (4) studies published in English; (5) cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies.

Exclusion criteria: (1) animal experiments; (2) studies in which data were incomplete; (3) reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, conference reports, editorial materials, and letters.

Quality assessment and data extraction

The Chinese version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the quality of the literature in cohort studies and case-control studies. The total score of the scale was 10, with < 5 as low quality and ≥5 as high quality. Regarding quality evaluation of cross-sectional studies, the Business Integration (JBI) scale was adopted, with 1–14 as low quality and 15–20 as high quality.

For each study, the following information was extracted, including author, year, country, study design, group, the number of patients, gender, age, subtype, tumor size, extent of surgery, tumor node metastasis stage, follow up, quality, outcomes.

Outcomes

The association between HT and clinical outcomes of PTC was assessed by lymph node metastasis (including lymph node metastasis, central lymph node metastasis, lateral lymph node metastasis), distant metastasis, extrathyroidal extension, recurrence, multifocality, invasion (includes vascular invasion, capsular invasion, perineural infiltration), bilaterality, number of deaths, AMES stage and MACIS score.

Statistical analysis

Software Stata (version 15.1, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Weighed mean differences (WMDs) were statistics for measurement data, odds ratios (ORs) were used as effect indicators for continuous variables and frequency of events, and effect sizes were represented by 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A heterogeneity test was performed for each indicator. If THE heterogeneity statistic I2≥50%, random-effects model analysis was carried out, otherwise, fixed-effects model analysis was performed. Each meta-analysis may create a false-positive or negative conclusion. Given this, TSA was conducted to reduce these statistical errors [16]. TSA is a methodology that combines an information size calculation (accumulated sample sizes of all included trials) to reduce type I error and type II error for a meta-analysis with the threshold of statistical significance (http://www.ctu.dk/tsa). TSA was used to quantify the statistical reliability of data in the cumulative meta-analyses by adjusting significance levels for sparse data and repetitive testing on accumulating data. Sensitivity analysis was performed for all outcomes, and publication bias was tested by Begg’s test. Given the age imbalance between the case group and control group, an age-based sensitivity analysis was also applied (S2 File). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

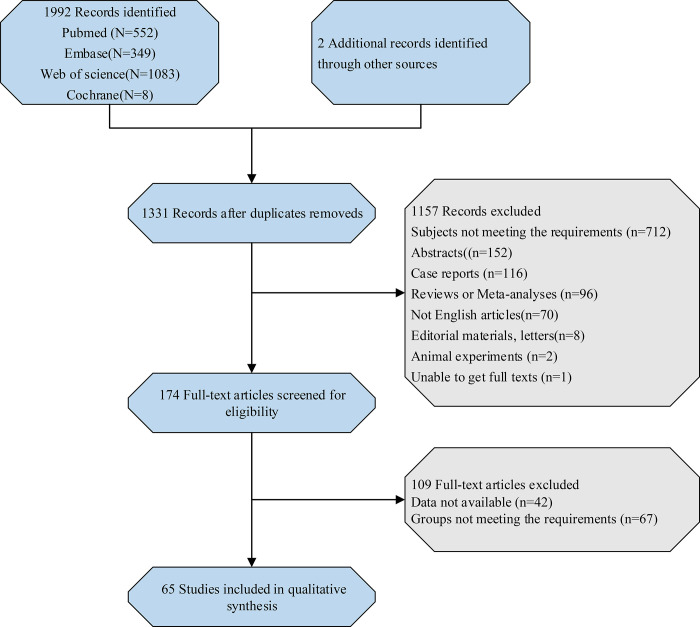

Initially, 1992 studies were searched according to the search strategy, and after duplicated removed, 1331 records were identified. With 174 full-text articles eligible for screening, 65 articles [5, 8, 9, 12, 13, 17–76] were finally included in this meta-analysis, including 32 case-control studies, 27 cohort studies, and 6 cross-sectional studies. The flow chart depicting the study selection process is shown in Fig 1. Totally 47,237 patients were enrolled in this study, of which 12909 patients with HT and 34328 patients without HT. The characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1.

Fig 1. Flow chart of the study selection process.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Study design | Group | Diagnosis of HT | No | Sex(female/male) | Age | Subtype of PTC | Tumor size (cm) | Extent of surgery | TNM stage | Follow up (months) | QA | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn | 2011 | Korea | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 211 | 170/41 | 48.32±14.4 | conventional 203, follicular variant 7, tall cell variant 1 | 1.8±1.5 | TT 178, thyroid lobectomy with isthmusectomy 33 | I 127, II/III/IV 84 | 62.8±27.0 | 9 | ①③④⑤⑧⑨⑩ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, germinal centres, and enlar ged epithelial cells with large nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Askanazy or Hurthle cells) | 58 | 55/3 | 42.8±12.7 | conventional 55, follicular variant 2, tall cell variant 1 | 1.6±1.0 | TT 47, thyroid lobectomy with isthmusectomy 11 | I 35, II/III/IV 23 | 59.0±25.4 | ||||||

| Babli | 2018 | Canada | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 309 | 258/58 | 49.3±13.87 | - | 2.06±1.62 | TT 475 | I 192, II 47, III 51, IV 19 | 25.5±19.5 | 7 | ①②③④⑤⑥⑦⑨ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic and plasma cell infiltration, lymphoid follicle formation with ger minal centers, varying degree of fibrosis, parenchymal atrophy, and the presence of large follicular cells with abundant oxyphilic cell changes | 166 | 146/20 | 48±13.78 | 1.96±1.53 | I 120, II 16, III 24, IV 6 | 24.6±16.3 | ||||||||

| Bircan | 2014 | Turkey | retrospective case-control | PTMC only | - | 105 | 81/24 | 51.06±13.24 | papillary 70, FVPC 27, follicular 8 | < 0.5 58 | - | - | - | 5 | ①⑥⑦ |

| PTMC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, germinal centres, and enlarged epithelial cells with large nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Askanazy or Hurthle cells) | 67 | 62/5 | papillary 38, FVPC 27, follicular 2 | < 0.5 35 | ||||||||||

| Cai | 2015 | China | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 823 | 827/225 | 46.2±11.4 | - | 1.1±0.8 | TT or lobectomy with prophylactic CLND and/or therapeutic LLND | I/II 753, III/IV 299 | - | 5 | ①③⑤ |

| PTC+HT | diffused lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with germinal centers, parenchymal atrophy with oncocytic changes, and variable amounts of stromal fibrosis throughout the thyroid gland | 229 | 1.1±0.8 | ||||||||||||

| Carvalho | 2017 | Brazil | prospective cohort | PTC only | - | 442 | 347/95 | median 46 (14–76) | - | ≤2 132, 2–4 228, >4 82 | TT 633 | T1bN0 35, T1N1 62, T2N0 87, T2N1 53, T3N0 119, T3N1 80, T4N0 1, T4N11 | 66 (24–120) | 8 | ①③④⑥⑦ |

| PTC+HT | histological criteria included diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration | 191 | 160/31 | median 48 (13–80) | ≤2 62, 2–4 96, >4 33 | T1bN0 18, T1N1 24, T2N0 38, T2N1 24, T3N0 52, T3N1 35 | |||||||||

| Consorti | 2010 | Italy | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 76 | 57/19 | 56.27±12.79 | - | 1.265±1.203 | TT 101 | I 57, II 3, III/IV 16 | - | 6 | ①⑥ |

| PTC+HT | dense focal or diffuse lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration of the thyroid, with formation of lymphoid follicles including germinal centres, follicular hyperplasia and damage to the follicular basement membrane | 25 | 20/5 | 54.48±13.37 | 1.571±1.271 | I 15, II 1, III/IV 9 | |||||||||

| Cordioli | 2013 | Brazil | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 59 | 49/10 | 44.7±14.7 | - | 2.51±2.09 | - | T1/T2 26, T3/T4 33 | - | 6 | ①⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate with the presence of lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers, as well as occasional Hürthle cells | 35 | 31/4 | 45.8±13.2 | 1.56±1.30 | T1/T2 23, T3/T4 12 | |||||||||

| Cortes | 2018 | Brazil | prospective cohort | PTC only | - | 68 | 61/7 | median 48 (18–74) | - | - | TT 113 | I 40, II 6, III 14, IV 8 | 96 (62–140) | 7 | ①② |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration | 45 | 42/3 | median 46 (13–72) | I 24, II 4, III 9, IV 8 | 96(60–140) | |||||||||

| Dobrinja | 2016 | Italy | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 90 | 56/34 | 54 (12–84) | - | median 1.34 (0.05–6.5) | TT 85, loboistmectomy 5 | I 55, II 3, III 21, IV 11 | 39 (18–343) | 8 | ①④⑤⑧ |

| PTC+HT | laboratory tests and postsurgical histological examination, histopathological criteria included epithelial cell destruction and mononuclear lymphocytic infiltrate accompanied by lymphoid germinal center formation and variable degree offibrosis | 70 | 61/9 | 52 (19–86) | median 1.54 (0.06–10.0) | TT 68, loboistmectomy 2 | I 50, II 4, III 14, IV 2 | 47 (18–156) | |||||||

| Dvorkin | 2013 | Israel | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 98 | 90/8 | 50.5±15 | - | 1.95±1.3 | TT 196 | I 55, II 11, III 23, IV 9 | ≥12 | 8 | ③⑤ |

| PTC+HT | patient’s history of hypothyroidism with positive antithyroid antibodies or when there was a diffuse lymphocytic infiltration bilaterally on the pathology report | 98 | 91/7 | 50.5±15 | 1.78±1.2 | I 57, II 9, III 22, IV 8 | |||||||||

| Fiore | 2011 | Italy | cross-sectional | PTC only | - | 554 | 405/149 | 39.6±13.1 | classic 312, tall cell 73, follicular 80, mixed form 79, other 10 | - | - | T1 211, T2 72, T3 271 | - | 13 | ① |

| PTC+HT | a) high titer of TAb (>100 U/ml of both TgAb and TPOAb) or hypothyroid, or b) positive TAb not fulfilling the criteria reported in point a), but presented a clear hypoechoic ‘thyroiditis’ pattern at thyroid ultrasound | 112 | 91/21 | - | classic 59, tall cell 19, follicular 16, mixed form 16, other 1 | T1 46, T2 13, T3 53 | |||||||||

| Giagourta | 2014 | Greece | retrospective cross-sectional | PTC only | - | 939 | 817/122 | 54±14 | papillary 610, papillary/follicular 329 | 2.12±1.62 | TT 1380 | I 410, II 364, III/IV 165 | - | 15 | ①②⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | dense or diffuse lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration, oxyphilic cells, and formation of lymphoid follicles in the tissue of both lobes | 441 | 379/62 | 42±10 | papillary 282, papillary/follicular 159 | 1.83±1.53 | I 206, II 190, III/IV 45 | ||||||||

| Girardi | 2015 | Brazil | retrospective cross-sectional | PTC only | - | 269 | 203/66 | 47.15±14.14 | - | 1.91±1.70 | TT 269, lymphadenectomy 102 | I 181, II 10, III 63, IV 15 | - | 14 | ①②③⑤⑥ |

| PTC+HT | an association of lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with germinative center formation, oxyphilic cell metaplasia (Hürtle), atrophy, and fibrosis of thyroid follicles | 148 | 136/12 | 45.97±14.10 | 1.40±1.15 | TT 148, lymphadenectomy 79 | I 119, II 5, III 22, IV 2 | ||||||||

| Han | 2019 | China | case-control | PTC only | - | 89 | 63/26 | 42.3±12.3 | - | 1.2±0.7 | - | I/II 88, III/IV 1 | - | 4 | ①③⑤ |

| PTC+HT | pathological diagnosis | 49 | 47/2 | 39.9±12.5 | 1.3±0.9 | I/II 47, III/IV 2 | |||||||||

| Huang | 2011 | China | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 1703 | 1366/337 | 40.8±14.2 | - | 2.3±0.04 | TT 411, LND/radical neck dissection 1292 | I 1278, II 140, III 76, IV 205 | 116.4±2.4 | 7 | ④⑧ |

| PTC+HT | histological diagnosis | 85 | 84/1 | 39.5±12.6 | 2.1±0.1 | TT 14, LND/radical neck dissection 71 | I 70, II 4, III 7, IV 4 | 104.4±7.2 | |||||||

| Ieni | 2017 | Italy | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 337 | 253/84 | 47.21±13.76 | classic variant 180, follicular variant 118, sclerosing 23, tall cell 6, Warthin-like 3, hobnail/micropapillary 6, cribriform 1 | 1.2±0.971 | - | T1a 168, T1b 67, T2 22, T3 79, T4 1 | - | 5 | ① |

| PTC+HT | lymphocytic infiltration with germinal center formation and Hürthle cell metaplasia | 168 | 146/22 | 44.42±13.72 | classic variant 76, follicular variant 65, sclerosing 16, tall cell 3, Warthin-like 6, hobnail/micropapillary 2 | 0.939±0.61 | T1a 110, T1b 38, T2 12, T3 8 | ||||||||

| Jara | 2013 | USA | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 269 | 192/77 | median 47(11–86) | conventional 205, follicular variant 48, tall cell variant 16 | 2.08(1.0–2.5) * | TT 257, hemithyroidectomy 12 | I 169, II 13, III 55, IV 32 | - | 6 | ①③⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | pathological diagnosis | 226 | 199/27 | median 43(17–80) | conventional 159, follicular variant 45, tall cell variant 18, trabecular variant 3, warthin-like features 1 | 1.56(0.8–2.0) * | TT 219, hemithyroidectomy 7 | I 180, II 7, III 23, IV 16 | |||||||

| Jeong | 2012 | Korea | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 402 | 332/70 | 48.56±11.02 | - | 1.12±0.77 | TT 402 | I 227, II 2, III 163, IV 10 | 58.12±8.12 | 8 | ①③④⑤⑨⑩ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, oxyphilic cells, formation of lymphoid follicles with germinal centers and atrophic changes in the area of normal thyroid tissue | 195 | 188/7 | 47.24±9.84 | 0.99±0.61 | TT 195 | I 107, III 84, IV 3 | 58.55±7.19 | |||||||

| Kashima | 1998 | Japan | case-control | PTC only | - | 1252 | 1123/129 | 48.6 | - | 2.82 | - | - | 82.8±56.4 | 6 | ①③⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | obvious lymphoid follicles with germinal centers and coexisting atrophie follicular epithelium | 281 | 279/2 | 42.6 | 2.42 | 127.2±72 | |||||||||

| Kebebew | 2001 | USA | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 95 | 61/34 | 54 | - | ≤1 37, 1–4 44, >4 7, unknown 7 | TT/near TT 64, subtotal thyroidectomy 5, lobectomy 26 | I 61, II 12, III 13, IV 5 | 52.8 | 8 | ⑥⑧⑩ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, oxyphilic cells, formation of lymphoid follicles with germinal centers and atrophic changes in the area of normal thyroid tissue | 41 | 34/7 | 45.5 | ≤1 19, 1–4 19, >4 1, unknown 2 | TT/near TT 26, subtotal thyroidectomy 4, lobectomy 11 | I 27, II 6, III 6 | ||||||||

| Kim | 2009 | Korea | case-control | PTC only | - | 64 | 54/10 | 44.1±13.4 | - | 1.48±1.13 | - | I/II 38, III/IV 26 | - | 6 | ①③ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with germinal centers, parenchymal atrophy with oncocytic change, and variable amounts of stromal fibrosis throughout the thyroid gland | 37 | 36/1 | 49.4±12.7 | 1.22±0.88 | I/II 17, III/IV 20 | |||||||||

| Kim | 2010 | Korea | case-control | PTMC only | - | 218 | 174/44 | <45 81 | - | 0.8–1 100 | TT 128 | - | - | 6 | ③⑤⑥ |

| PTMC+HT | heavy infiltration of lymphocytes with varying degrees (including germinal centers) in thyroid tissue, the presence of Hurthle cells and varying degree of acini atrophy | 105 | 100/5 | <45 37 | 0.8–1 46 | TT 57 | |||||||||

| Kim | 2011 | Korea | case-control | PTC only | - | 254 | 219/35 | 48.1±11.5 | - | 1.13±0.86 | TT 397, bilateral CLND 395, lateral or modified LND 95 | I/II 125, III/IV 129 | - | 6 | ①②③⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | any 1 of the following criteria: (1) positive for anti-TPO antibody, (2) positive for antithyroglobulin antibody, (3) pathologic confirmation of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | 146 | 138/8 | 45.9±11.6 | 1.10±0.64 | I/II 88, III/IV 58 | |||||||||

| Kim | 2011 | Korea | case-control | PTC only | - | 721 | 527/194 | 48.0±12.1 | - | 1.24±0.96 | - | III/IV 312 | - | 6 | ①③⑤ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrations with germinal centers, parenchymal atrophy with oncocytic changes, and variable amounts of stromal fibrosis throughout the thyroid gland | 307 | 294/13 | 47.5±10.3 | 1.08±0.72 | III/IV 118 | |||||||||

| Kim | 2013 | Korea | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 931 | 778/153 | 46.80±11.01 | - | 1.01±0.75 | lobectomy 106, TT+MRND 824 | - | - | 7 | ③④⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, oxyphilic cells, formation of lymphoid follicles with germinal centers and atrophic changes in the area of normal thyroid tissue | 316 | 304/12 | 46.41±10.48 | 0.93±0.63 | lobectomy 19, TT+MRND 297 | |||||||||

| Kim | 2014 | Korea | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 125 | 114/11 | 48.6(25–75) | - | 0.93(0.2–4) | TT 144 | - | 68.9±8.1 | 8 | ①③④⑤ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphocytic thyroiditis with follicular atrophy, diffuse destruction of thyroid follicles, fibrosis, and follicular cell regeneration | 19 | 19/0 | 43.0(28–65) | 0.86(0.3–1.5) | ||||||||||

| Kim | 2016 | Korea | case-control | PTC only | - | 1576 | 1289/287 | 47.2±12.0 | - | 0.9±0.6 | TT 1466, <TT 110 | I/II 957, III/IV 619 | - | 5 | ①③⑤ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with germinal centers, parenchymal atrophy with oncocytic changes, and variable amounts of stromal fibrosis throughout the thyroid gland | 204 | 198/6 | 44.8±11.9 | 0.8±0.5 | TT 190, <TT 14 | I/II 149, III/IV 55 | ||||||||

| Kim | 2016 | Korea | case-control | PTC only | - | 2326 | 1687/639 | 47.6±11.9 | - | 1.2±0.8 | TT+bilateral CND 3332 | - | - | 6 | ①③⑥ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse parenchymal infiltration by lymphocytes (particularly plasma B-cells), a germinal center formation, follicular destruction, Hurthle cell change and variable amounts of stromal fibrosis throughout the thyroid gland | 1006 | 912/94 | 46.0±11.4 | 1.1±0.7 | ||||||||||

| Kim | 2018 | Korea | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 124 | 107/17 | 50.06±11.51 | - | 0.92±0.73 | TT 172 | I/II 71, III 40, IV 13 | - | 6 | ①③⑤⑥ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate, oxyphilic cells and the formation of lymphoid follicles or reactive germinal centers in the area of normal thyroid tissue | 48 | 45/3 | 46.44±10.62 | 0.88±0.69 | I/II 36, III 11, IV 1 | |||||||||

| Konturek | 2014 | Poland | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 643 | 574/69 | <45 278, ≥45 365 | - | 0.94±0.69 | TT+CLND, subtotal bilateral lobectomies | T1a 391, T1b 57, T2 78, T3 108 | - | 7 | ①⑤ |

| PTC+HT | (1) high anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies titers(anti-TPO), (2) lesions visualized by ultrasonography showing a hypoechoic or hyperechoic nodular pattern at least 5 mm in diameter, identification of a perinodular hypoechogenic or hyperechogenic halo and presence of an anechoic lesion with a reinforced posterior wall, (3) histology: presence of a diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate in the thyroid parenchyma and stroma with reaction foci and lymphatic follicles, presence of small follicles with a decreased colloid volume, foci of fibrosis and oxyphilic cytoplasm-containing cells | 130 | 110/20 | <45 52, ≥45 78 | 0.87±0.59 | T1a 80, T1b 22, T2 12, T3 16 | |||||||||

| Kurukahvecioglu | 2007 | Turkey | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 162 | 123/39 | 46.6±13.5 | follicular variant 37 | <1 18, ≥1 114 | TT 199 | - | - | 6 | ⑥ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse mononuclear cell infiltration with fibrosis, occasional well-developed germinal centers, and enlarged follicular cells with abundant eosinophilic, granular cytoplasms | 37 | 36/1 | follicular variant 4 | <1 19, ≥1 48 | ||||||||||

| Kwak | 2015 | Korea | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 1493 | 1187/306 | 46.12±12.13 | classical 1369, follicular variant 84, cystic 14, oncocytic 4, others 22 | 0.935±0.7 | thyroid lobectomy or TT with cervical LND 1945 | I 648, II 9, III 736, IV 100 | 27(9–55) | 8 | ③④⑤⑦⑧ |

| PTC+HT | pathological diagnosis included chronic lymphocytic infiltration | 452 | 412/40 | 45.25±11.63 | classical 412, follicular variant 31, cystic 4, oncocytic 1, cribriform 1, others 3 | 0.003±0.762 | I 229, II 2, III 205, IV 16 | ||||||||

| Kwon | 2014 | Korea | cohort | PTC only | - | 86 | 72/14 | 48.8±12.2 | conventional 79, variants 7 | <2 70, 2–4 15, >4 1 | - | - | 64.8±8.6 | 7 | ①③⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with germinal centers, parenchymal atrophy with oncocytic change, and variable amounts of stromal fibrosis throughout the thyroid gland | 84 | 80/4 | 47.1±11.6 | conventional 71, variants 13 | <2 76, 2–4 6, >4 2 | 64.3±11.1 | ||||||||

| Kwon | 2016 | Korea | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 473 | 350/123 | 48.4±10.5 | - | 1.23±0.93 | TT+CLND 433 | - | 69.1±23.5 | 5 | ①③⑤⑥⑦ |

| PTC+HT | histological diagnosis | 215 | 200/15 | 46.9±10.4 | 1.11±0.96 | TT+CLND 198 | |||||||||

| Lee | 2018 | Korea | case-control | PTC only | - | 1296 | 967/329 | 47.3±12.0 | - | 0.83±0.53 | - | - | - | 5 | ①③⑤ |

| PTC+HT | pathology reports or chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis | 563 | 528/35 | 46.4±11.3 | 0.83±0.58 | ||||||||||

| Lee | 2020 | Korea | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 1754 | 1286/468 | 46.4±0.28 | - | 1.06±0.022 | TT 854, <TT 900 | T1 1426, T2 86, T3 184, T4 58 | 24(1–90) | 5 | ①③④⑤⑥⑦ |

| PTC+HT | lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with germinal center and the presence of large follicular cells with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm on histologic examination | 1174 | 1082/92 | 45.5±0.32 | 0. 96±0.021 | TT 822, <TT 352 | T1 918, T2 46, T3 189, T4 21 | ||||||||

| Liang | 2017 | China | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 1035 | 789/246 | 45.34±12.63 | - | 1.94±1.14 | thyroid lobectomy with isthmusectomy 520, TT 872, CLND without LLND 785, comprehensive neck dissections 495 | I 644, II 51, III 175, IV 165 | 38.4 (3.1–125.3) | 8 | ①②③④⑤⑧⑨⑩ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, germinal centres and enlarged epithelial cells with large nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm | 357 | 323/34 | 44.14±11.95 | 1.58±0.97 | I 252, II 7, III 67, IV 31 | |||||||||

| Lim | 2013 | Korea | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 1983 | 1476/507 | median 45 | - | 0.83 | bilateral TT 2316, unilateral TT 751 | III/IVA 698 | - | 4 | ①③⑤ |

| PTC+HT | pathology reports | 964 | 873/91 | median 45 | 0.79 | III/IVA 311 | |||||||||

| Liu | 2014 | China | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 1141 | 840/301 | 45.25±13.63 | - | 1.508±0.0358 | - | - | - | 6 | ①⑥ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphocytic infiltration with the formation of lymphoid follicles and reactive germinal centers | 581 | 535/46 | 41.40±13.26 | 1.392±0.0421 | ||||||||||

| Liu | 2016 | China | retrospective case-control | PTMC only | - | 119 | 77/42 | 46.35±11.23 | - | 0.87±0.22 | - | - | - | 5 | ①⑤⑦ |

| PTMC+HT | 49 | 38/11 | 42.18±9.84 | 0.65±0.12 | |||||||||||

| Lu | 2020 | China | case-control | PTC only | - | 89 | 63/26 | 42.6±12.4 | - | 1.1±0.7 | - | I/II 88, III/IV 1 | - | 4 | ①③⑤ |

| PTC+HT | pathology reports | 51 | 47/4 | 39.5±13.1 | 1.4±1.0 | I/II 49, III/IV 2 | |||||||||

| Lun | 2013 | China | case-control | PTC only | - | 549 | 419/130 | 44.8±13.3 | - | 2.24±1.38 | - | III/IV 101 | - | 6 | ① |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphocytic infiltration, germinal centers, enlarged epithelial cells with large nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Askanazy or Hurthle cells), and variable amounts of stromal fibrosis throughout the thyroid gland | 127 | 118/9 | 41.3±12.5 | 1.84±0.93 | III/IV 8 | |||||||||

| Ma | 2018 | China | case-control | PTC only | - | 365 | 306/59 | <45 180, ≥45 185 | - | <1 150, ≥1 215 | - | - | - | 4 | ① |

| PTC+HT | 85 | 79/6 | <45 40, ≥45 45 | <1 41, ≥1 44 | |||||||||||

| Marotta | 2013 | Italy | case-control | PTC only | - | 92 | 66/26 | 56.1 | - | 1.12ml | - | I 54, II 19, III 19 | - | 6 | ①③⑤ |

| PTC+HT | lymphoplasmacytic infiltrations with germinal centers, and serum antithyroperoxidase antibodies measured by an immunoenzymatic assay | 54 | 50/4 | 50.2 | 0.84ml | I 36, II 4, III 14 | |||||||||

| Marotta | 2017 | Italy | multicentre retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 173 | 133/40 | median 37 (15–71) | classic 96, follicular 36, hürthle cells 9, warthin-like 6, tall cell 12, solid 9, diffuse sclerosing 5 | median 1.3 (0.7–4) | - | - | 75±59 | 8 | ⑤ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse/focal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, oxyphilic cells, lymphoid follicles with germinal centres and atrophic changes involving normal thyroid tissue | 128 | 120/8 | median 39.5 (17–64) | classic 61, follicular 42, hürthle cells 5, warthin-like 18, tall cell 1, solid 1 | median 1 (0.6–4) | |||||||||

| Mohamed | 2020 | Egypt | cross-sectional | PTC only | - | 64 | 44/20 | ≤ 45 24, > 45 40 | follicular variant 24, classic variant 40 | ≤ 2 38, > 2 26 | TT or near TT 80 | I/II 44, III/IV 20 | 120 (84–120) | 15 | ①②③④⑤⑥⑧ |

| PTC+HT | lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with the formation of germinal center, oxyphilic cell metaplasia (Hürthle cells), atrophy, and fibrosis of thyroid follicles | 16 | 14/2 | ≤ 45 6, > 45 10 | follicular variant 4, classic variant 12 | ≤ 2 12, > 2 4 | I/II 10, III/IV 6 | ||||||||

| Molnar | 2019 | Hungary | case-control | PTC only | - | 190 | 164/26 | 48.03±16.74 | classic 143, follicular variant 34, other 13 | - | - | 1.33±0.79 | - | 7 | ①⑤ |

| PTC+HT | chronic lymphocytic infiltration, secondary lymphatic follicules and follicular atrophy, occasionally extended by the additional presence of Hürthle cell metaplasia | 40 | 36/4 | 44.03±16.18 | classic 28, follicular variant 9, other 3 | 1.20±0.61 | |||||||||

| Nam | 2016 | Korea | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 15 | 10/5 | 47.13±13.84 | - | median 1.4 (0.7–4.5) | TT + unilateral/bilateral CLND 37 | I 5, II 1, III 4, IV 5 | 51.81±16.35 | 8 | ①②③⑤ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, oxyphilic cells, formation of lymphoid follicles with germinal centres and atrophic changes in the area of normal thyroid tissue | 22 | 21/1 | 44.18±13.64 | median 1.1 (0.3–3.5) | I 14, III 6, IV2 | 47.65±14.45 | ||||||||

| Park | 2015 | Korea | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 484 | 401/83 | 46.06±10.56 | - | 1.055±0.715 | TT 294, lobectomy 153, subtotal thyroidectomy 37 | T1a 219, T1b 59, T2 11, T3 192, T4 2 | - | 6 | ①⑤⑥ |

| PTC+HT | a progressive loss of thyroid follicular cells with replacement by lymphocytes and formation of germinal centers associated with fibrosis | 49 | 48/1 | 43.80±9.92 | 0.875±0.398 | TT 38, lobectomy 10, subtotal thyroidectomy 1 | T1a 30, T1b 9, T3 10 | ||||||||

| Paulson | 2012 | USA | historical cohort | PTC only | - | 78 | 57/21 | 45.6 | classic 65, follicular variant 12, other 1 | 2.8 | TT+ CLND 139 | - | - | 8 | ①②⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, oxyphilic cells, formation of lymphoid follicles with germinal centres and atrophic changes in the area of normal thyroid tissue | 61 | 54/7 | 39.6 | classic 43, follicular variant 17, other 1 | 2.2 | |||||||||

| Pilli | 2018 | Italy | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 300 | 209/91 | 45.1±16.9 | - | - | TT 375 | - | 75.36±46.32 | 7 | ④ |

| PTC+HT | a rich lymphocytic infiltrate diffuse throughout the thyroid gland, commonly organized in follicles with a germinal center. | 75 | 68/7 | 45.7±14.3 | |||||||||||

| Qu | 2016 | China | retrospective cohort | PTMC only | - | 886 | 621/265 | 44.2±10.6 | - | 0.77±0.22 | TT 84, non-TT 802 | T1 782, T3 83, T4 21 | 63.7±18.6 | 8 | ①③④⑤⑥ |

| PTMC+HT | any one of the following criteria: (1) positive for anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody, (2) positive for antithyroglobulin antibody, (3) pathologic confirmation of HT | 364 | 320/44 | 44.3±10.5 | 0.72±0.21 | TT 39, non-TT 325 | T1 337, T3 18, T4 9 | 61±17.1 | |||||||

| Ryu | 2020 | Korea | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 370 | 293/77 | ≤55 299, >55 71 | - | ≤1 230, >1 140 | TT + bilateral CLND 850 | I 323, II 43, III 4 | 95.5 (12–158) | 8 | ①③④⑤⑥⑦ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphocytic infiltration in the area of the normal thyroid tissue irrespective of the presence of anti-thyroid antibodies | 480 | 445/35 | ≤55 382, >55 98 | ≤1 352, >1 129 | I 444, II 33, III 3 | |||||||||

| Singh | 1999 | USA | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 331 | 222/109 | median 43 | - | median 2 | total 158, <total 173 | median II | 43.6 | 8 | ①②③ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate, oxyphilic cells, and the formation of lymphoid follicles and reactive germinal centers | 57 | 45/12 | median 41 | median 2 | total 26, <total 31 | median II | ||||||||

| Song | 2018 | Korea | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 1064 | 854/210 | median 49.0 | - | median 1.2 | TT + CLND 1369 | - | 96 | 8 | ①③⑤ |

| PTC+HT | bilaterally diffuse lymphocytic infiltrates and lymphoid follicles with germinal centres in the area of normal thyroid tissue | 305 | 283/22 | median 49.1 | median 1.2 | ||||||||||

| Wang | 2018 | China | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 119 | 91/28 | <45 59, ≥45 60 | - | 1.924±0.993 | bilateral thyroidectomies 206 | I/II 86, III/IV 33 | - | 6 | ①⑥ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphocytic infiltration in the thyroid parenchyma and stroma, with formation of reactive germinal centers and lymphoid nodules and presence of oxyphilic cells | 87 | 81/6 | <45 36, ≥45 51 | 1.518±1.101 | I/II 71, III/IV 16 | |||||||||

| Yang | 2016 | Korea | case-control | PTC only | - | 10 | - | 47(35–59) | conventional 10 | 0.61(0.1–1.5) | - | - | - | 4 | ①③ |

| PTC+LT | pathology reports | 13 | conventional 11, follicular variant 2 | 0.55(0.2–1.1) | |||||||||||

| Ye | 2013 | China | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 817 | 646/171 | <30 65, 30–44 362, 45–59 291, >60 99 | - | ≤1 496, 1–4 304, >4 17 | - | I 687, II 25, III 70, IV 35 | - | 6 | ①③⑦ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration, oxyphilic cells, and lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers | 187 | 182/5 | <30 23, 30–44 76, 45–59 74, >60 14 | ≤1 126, 1–4 59, >4 2 | I 160, II 4, III 15, IV 8 | |||||||||

| Yoon | 2012 | Korea | case-control | PTC only | - | 139 | 112/27 | 49.6±11.3 | - | 0.95±0.60 | TT + bilateral CLND 195 | - | - | 6 | ①③⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | lymphoid follicles with germinal centers and atrophic changes in the area of normal thyroid parenchyma | 56 | 54/2 | 45.9±11.1 | 0.77±0.41 | ||||||||||

| Zeng | 2016 | China | retrospective cross-sectional | PTC only | - | 397 | 289/108 | 45.5±11.8 | - | 1.57±0.89 | thyroidectomy + CLND 619 | I/II 240, III/IV 158 | - | 14 | ①③⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | diffused lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with germinal centers, parenchymal atrophy with oncocytic changes, and variable amounts of stromal fibrosis throughout the thyroid gland | 222 | 195/27 | 45.9±12.1 | 1.43±0.86 | I/II 140, III/IV 81 | |||||||||

| Zeng | 2018 | China | case-control | PTC only | - | 39 | 33/6 | <45 14, ≥ 45 25 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | ① |

| PTC+HT | pathological diagnosis | 46 | 36/10 | <45 25, ≥ 45 21 | |||||||||||

| Zeng | 2018 | China | cross-sectional | PTC only | - | 106 | 83/23 | < 15 14, 15–20 92 | - | < 2 25, ≥2 80 | thyroidectomy 129 | I 98, II 8 | - | 16 | ①②③ |

| PTC+HT | diffuse lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration in the thyroid parenchyma and stroma, oxyphilic cells, and lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers | 23 | 23/0 | < 15 3, 15–20 20 | < 2 13, ≥2 10 | I 23 | |||||||||

| Zhang | 2014 | China | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 1488 | - | 46.6±12.4 | - | 1.34±1.05 | unilateral lobectomy with isthmusectomy + cervical LND 1274, unilateral lobectomy of the affected side with isthmusectomy 248, TT + bilateral selective cervical LND 109 | I 1228, II–IV 260 | 36 (8–95) | 6 | ①③④⑤ |

| PTC+HT | pathological diagnosis | 247 | 220/27 | 43.1±12.0 | 1.10±0.77 | I 228, II–IV 19 | |||||||||

| Zhu | 2016 | China | retrospective case-control | PTC only | - | 486 | 356/130 | ≥ 45 237, <45 249 | - | ≤1 319, >1 167 | TT + bilateral CLND 763 | - | - | 4 | ①⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | histological diagnosis | 277 | 222/55 | ≥ 45 125, <45 152 | ≤1 170, >1 107 | ||||||||||

| Zhu | 2016 | China | retrospective cohort | PTC only | - | 963 | 729/234 | <45 469, ≥ 45 494 | classical 857, other variants 106 | 1.37±0.92 | TT/near TT + 1276 ipsilateral or bilateral CLND | I 625, II 30, III 298, IV 10 | 105 (3–156) | 7 | ①③⑤⑦ |

| PTC+HT | pathological diagnosis | 313 | 288/25 | <45 155, ≥ 45 158 | classical 258, other variants 55 | 1.32±0.88 | I 223, II 12, III 77, IV 1 |

Notes: QA, Quality assessment; HT, Hashimoto thyroiditis; CLT, chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis; PTC, papillary thyroid cancer; PTMC, papillary thyroid microcarcinoma; FVPC, follicular variant of papillary cancer; ETE, extrathyroidal extension; TT, total thyroidectomy; LND, lymph node dissection; CLND, central-compartment lymph node dissection; LLND, lateral-compartment lymph node dissection; MRND, modified radical neck dissection; TgAb, antithyroglobulin antibodies ① lymph node metastasis ② distant metastasis ③ extrathyroidal extension ④ recurrence ⑤ multifocality ⑥ bilaterality ⑦ invasion ⑧ deaths ⑨ MACIS score ⑩ AMES stage.

Lymph node metastasis

Lymph node metastasis

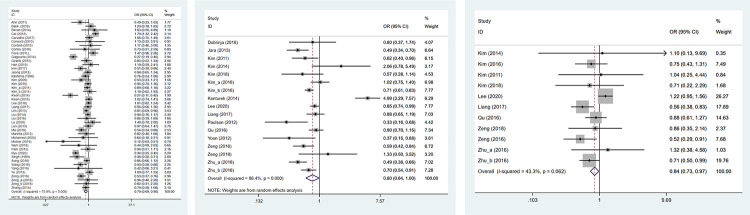

Lymph node metastasis was assessed in 44 studies including 11254 patients. The heterogeneity test results were statistically significant (I2 = 75.9%), so the random-effects model was adopted. The result showed that HT group had a lower risk of lymph node metastasis than non-HT group (OR: 0.787, 95%CI: 0.686–0.903, P = 0.001) (Table 2, Fig 2A).

Table 2. Overall and sensitivity analysis result.

| Variables | OR/WMD (95%CI) | P | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| Overall | 0.787(0.686,0.903) | 0.001 | 75.9 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 0.787(0.686,0.903) | ||

| Publication bias | Z = 0.86 | 0.39 | |

| Central lymph node metastasis | |||

| Overall | 0.796(0.636,0.995) | 0.045 | 86.4 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 0.796(0.636,0.995) | ||

| Publication bias | Z = 1.52 | 0.127 | |

| Lateral lymph node metastasis | |||

| Overall | 0.845(0.733,0.973) | 0.02 | 43.3 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 0.845(0.733,0.973) | ||

| Publication bias | Z = 0.78 | 0.436 | |

| Distant metastasis | |||

| overall | 0.435(0.279,0.676) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 0.435(0.279,0.676) | ||

| Publication bias | Z = 0.08 | 0.938 | |

| Extrathyroidal extension | |||

| Overall | 0.745(0.657,0.845) | <0.001 | 74.1 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 0.745(0.657,0.845) | ||

| Publication bias | Z = 0.82 | 0.412 | |

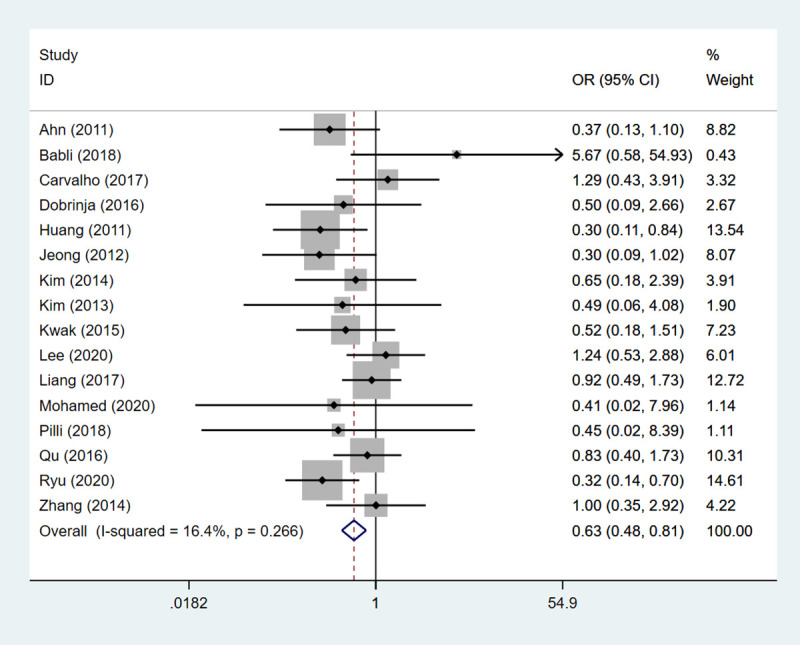

| Recurrence | |||

| Overall | 0.627(0.483,0.813) | <0.001 | 16.4 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 0.627(0.483,0.813) | ||

| Publication bias | Z = 0.32 | 0.753 | |

| Multifocality | |||

| Overall | 1.245(1.132,1.368) | <0.001 | 61.3 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 1.245(1.132,1.368) | ||

| Publication bias | Z = 1.16 | 0.245 | |

| Invasion | |||

| vascular invasion | |||

| Overall | 0.718(0.572,0.901) | 0.004 | 62 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 0.718(0.572,0.901) | ||

| Publication bias | Z = 0.29 | 0.773 | |

| Capsular invasion | |||

| Overall | 1.234(0.829,1.835) | 0.3 | 88.5 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 1.234(0.829,1.835) | ||

| Publication bias | Z = 0.73 | 0.466 | |

| Perineural infiltration | |||

| Overall | 1.922(1.195,3.093) | 0.007 | 0 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 1.922(1.195,3.093) | ||

| Bilaterality | |||

| Overall | 1.394(1.118,1.739) | 0.003 | 78.9 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 1.394(1.118,1.739) | ||

| Publication bias | Z = 2.20 | 0.028 | |

| Deaths | |||

| Overall | 0.827(0.386,1.773) | 0.626 | 16.8 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 0.827(0.386,1.773) | ||

| Disease-specific death | |||

| Overall | 0.305(0.059,1.585) | 0.158 | 0 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 0.305(0.059,1.585) | ||

| AMES stage | |||

| Low risk | |||

| Overall | 1.396(1.109,1.758) | 0.005 | 0 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 1.396(1.109,1.758) | ||

| MACIS score | |||

| overall | -0.221(-0.306, -0.137) | <0.001 | 37.8 |

| Sensitivity analysis | -0.221(-0.306, -0.137) | ||

| <6 | |||

| Overall | 1.568(0.930,2.645) | 0.092 | 56.7 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 1.568(0.930,2.645) |

Notes: OR: odds ratio; WMD: weighed mean difference.

Fig 2.

The forest plot of lymph node metastasis between HT group and non-HT group; (a) overall analysis of lymph node metastasis; (b) central lymph node metastasis; (c) lateral lymph node metastasis.

Central lymph node metastasis

Seventeen studies involving 7328 patients were identified to assess central lymph node metastasis. The random-effect model result indicated that PTC patients with HT had a lower risk of developing central lymph node metastasis than those without (I2 = 86.4%, OR: 0.796, 95%CI: 0.636–0.995, P = 0.045) (Table 2, Fig 2B).

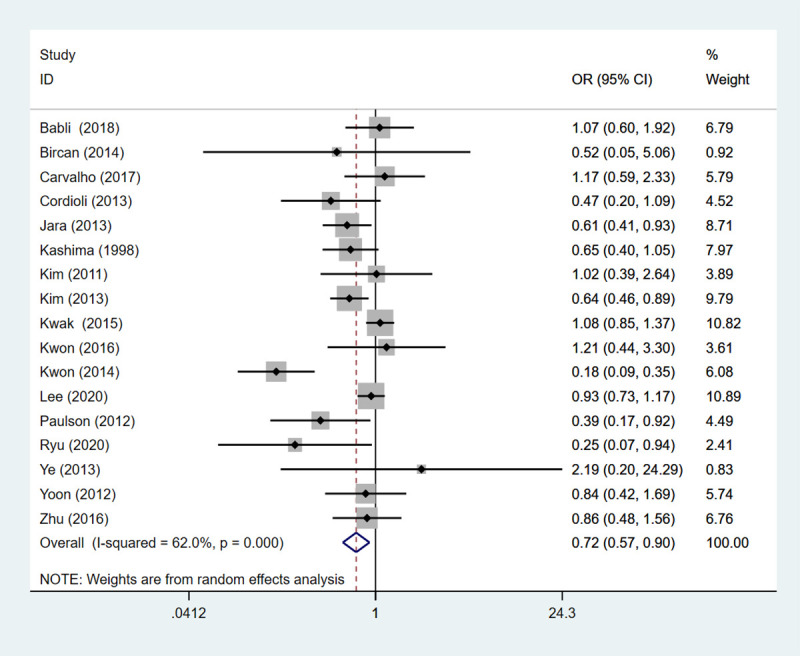

Lateral lymph node metastasis

A total of 11 studies consisting of 1362 patients provided data to assess lateral lymph node metastasis. The heterogeneity test results were not statistically significant (I2 = 43.3%), so the fixed-effect model was adopted. It was shown that HT was associated with a decreasing risk of lateral lymph node metastasis in PTC patients (OR: 0.845, 95%CI: 0.733–0.973, P = 0.02) (Table 2, Fig 2C).

Distant metastasis

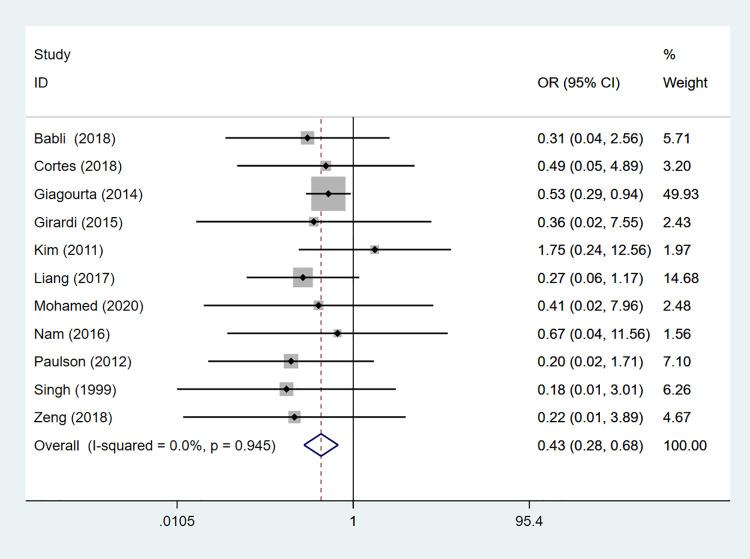

Distant metastasis was assessed in 11 studies comprising 151 patients. The fixed-effects model result showed that the HT group was at a lower risk of distant metastasis than the non-HT group (OR: 0.435, 95%CI: 0.279–0.676, P<0.001) (Table 2, Fig 3).

Fig 3. The forest plot of distant metastasis between HT group and non-HT group.

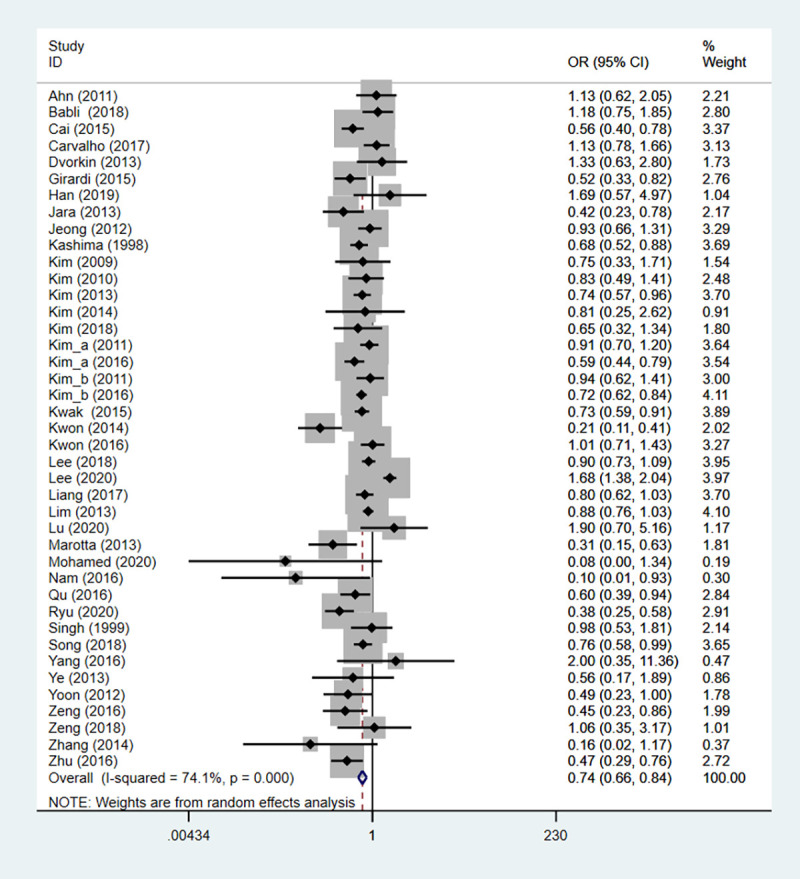

Extrathyroidal extension

Totally 41 studies covering 13940 patients identified the association between HT and clinical outcome of PTC. The heterogeneity test results were statistically significant (I2 = 74.1%), so the random-effect model was utilized. The result revealed that the risk of extrathyroidal extension in the HT group was lower than that in the non-HT group (OR: 0.745, 95%CI: 0.657–0.845, P<0.001) (Table 2, Fig 4).

Fig 4. The forest plot of extrathyroidal extension between HT group and non-HT group.

Recurrence

Sixteen studies containing 577 patients have assessed the recurrence. The result of fixed-effects model demonstrated that HT could decrease the risk of recurrence in PCT (OR: 0.627, 95%CI: 0.483–0.813, P<0.001) (Table 2, Fig 5).

Fig 5. The forest plot of recurrence between HT group and non-HT group.

Multifocality

Multifocality referred to two or more foci found in the same lobe of the gland. A total of 44 studies embracing 10320 were included to evaluate multifocality. The heterogeneity test results were statistically significant (I2 = 61.3%), so the random-effects model was used. The result illustrated that that the HT group had a higher risk of multifocality than the non-HT group (OR: 1.245, 95%CI: 1.132–1.368, P<0.001) (Table 2).

Invasion

Vascular invasion

Totally 17 studies embodying 1837 patients probed into the vascular invasion. The result demonstrated that PTC patients with HT had a lower risk of vascular invasion than those without (OR: 0.718, 95%CI: 0.572–0.901, P = 0.004) (Table 2, Fig 6).

Fig 6. The forest plot of vascular invasion between HT group and non-HT group.

Capsular invasion

Nine studies including 2273 patients assessed the capsular invasion. No difference was found between the HT and non-HT groups in capsular invasion (OR: 1.234, 95%CI: 0.829–1.835, P = 0.300).

Perineural infiltration

Two studies comprising 132 patients assessed the perineural infiltration.The perineural infiltration risk of the HT group was higher than that of the non-HT group (OR: 1.922, 95%CI: 1.195–3.093, P = 0.007) (Table 2).

Bilaterality

Bilaterality referred to the presence of PTC in both thyroid lobes. Totally 18 studies involving 3421 were enrolled to assess bilaterality. Because the heterogeneity test results were statistically significant (I2 = 78.9%), the random-effects model was adopted. The result showed that HT increased the risk of bilaterality in PTC patients (OR: 1.394, 95%CI: 1.118–1.739, P = 0.003) (Table 2).

Deaths

Deaths

Death was identified in 6 studies containing 42 patients. There was no statistically significant in death between HT and non-HT groups (OR: 0.827, 95%CI: 0.386–1.773, P = 0.626).

Disease-specific death

Two studies including 82 patients were included to assess disease-specific death. The result of fixed-effects model demonstrated that HT was not associated with disease-specific death in PTC (OR: 0.305, 95%CI: 0.059–1.585, P = 0.158).

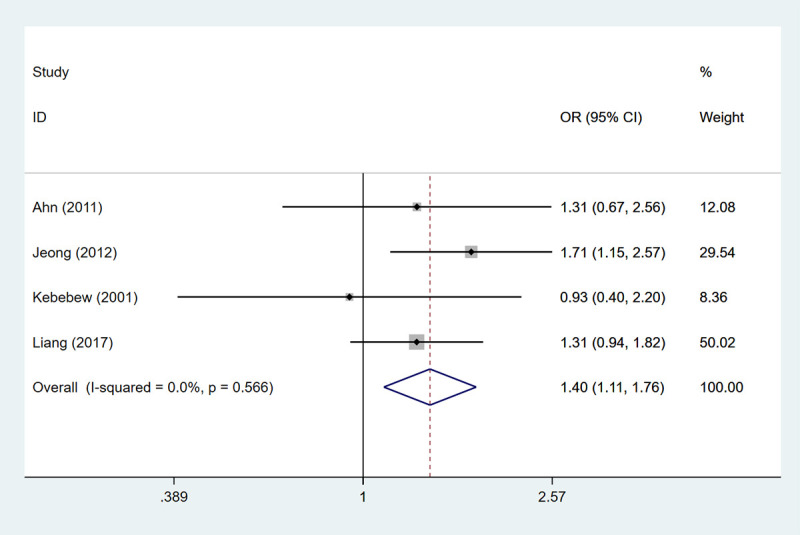

AMES stage-low risk

A total of 4 studies embracing 1874 patients were enrolled to assess AMES stage-low risk. The heterogeneity test results showed that the differences were not statistically significant (I2 = 0.0%), so the fixed-effects model was used for analysis. The low risk in the AMES stage represents a 20-year survival rate of 99%. The HT group had an advantage over the non-HT group in improving 20-year survival (OR: 1.396, 95%CI: 1.109–1.758, P = 0.005) (Table 2, Fig 7).

Fig 7. The forest plot of AMES stage-low risk between HT group and non-HT group.

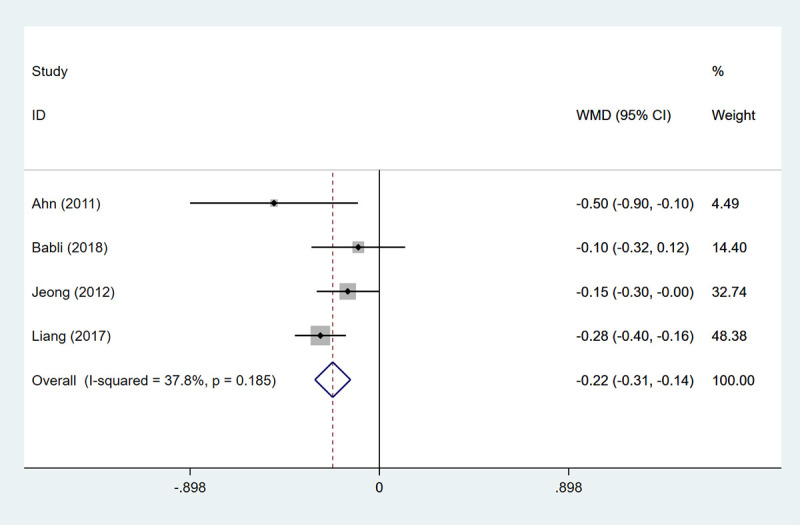

MACIS score

MACIS score

The higher the MACIS score, the worse the survival. Four studies involving 2733 patients were included to assess the MACIS score. The result uncovered that the the HT group had an advantage over the non-HT group in improving 20-year survival (WMD: -0.221, 95%CI: -0.306- -0.137, P<0.001) (Table 2, Fig 8).

Fig 8. The forest plot of MACIS score between HT group and non-HT group.

MACIS score <6

MACIS score <6 was assessed in 3 studies including 2321 patients. When MACIS score was <6, there was no difference in 20-year survival between HT and non-HT groups (OR: 1.568, 95%CI: 0.930–2.645, P = 0.092).

Publication bias

Begg’s test was used for the assessment of publication bias. The result showed that there was no publication bias for lymph node metastasis (Z = 0.86, P = 0.39), central lymph node metastasis (Z = 1.52, P = 0.127), lateral lymph node metastasis (Z = 0.78, P = 0.436), distant metastasis (Z = 0.08, P = 0.938), extrathyroidal extension (Z = 0.82, P = 0.412), recurrence (Z = 0.32, P = 0.753), multifocality (Z = 1.16, P = 0.245), vascular invasion (Z = 0.29, P = 0.773), capsular invasion (Z = 0.73, P = 0.466) (Table 2). However, there was a publication bias for bilaterality (Z = 2.20, P = 0.028) (Table 2). The trim and fill method was applied to adjust data for publication bias. The OR value of the random effects model before the trim and fill method was 1.394 (95%CI: 1.118–1.739). The random effects model was used to estimate the number of missing studies after 7 iterations, and the meta-analysis of all studies was conducted again. The OR value of the random-effects model after the trim and fill method was 2.858 (95%CI: 1.999–3.718), there was no significant change before and after the results, indicating that publication bias had little influence and the conclusions in the literature were relatively robust.

TSA

Lymph node metastasis

A total of 44 articles were included, with a total sample size of 28,813 cases. The required information size (RIS) was 34,021. The estimation of RIS was based on the following variables: Type I error of 0.05, Type II error of 0.2, Power of 80%, Relative Risk Reduction of 20%, and Incidence in Control arm of 10%. The TSA results showed that the cumulative Z curve crossed the traditional boundary line and intersected the TSA boundary line, but did not reach the RIS line, indicating that although the expected sample size was not reached, the positive results were obtained in advance, which further verified that the HT group was better in the low risk of lymph node metastasis than the HT group.

Central lymph node metastasis

Seventeen articles with a total sample size of 15947 cases were included, the RIS was 61030 cases, and the RIS was estimated based on the following variables: Type I error of 0.05, Type II error of 0.2, Power of 80%, Relative Risk Reduction of 20%, Incidence in Control arm of 10%. The TSA results showed that the cumulative Z curve crossed the traditional boundary line, but did not reach the TSA boundary line and the RIS line, revealing that the expected sample size was not reached. In the future, more experiments are needed to verify the risk of central lymph node metastasis in the HT group versus the non-HT group.

Extrathyroidal extension

Forty-one articles were included, with a total sample size of 35,547 cases, and the RIS was 34,408 cases. It was shown that the cumulative Z curve crossed the traditional boundary line, but did not reach the TSA boundary line and the RIS line, indicating that the expected sample size was not reached. More trials are needed in the future to verify the reliability of the conclusion that the HT group has a lower risk of central lymph node metastasis than the non-HT group.

Recurrence

Sixteen studies were included, with a total sample size of 15,856 cases, and the RIS was 8,342 cases. TSA results demonstrated that the cumulative Z curve crossed the traditional boundary line, intersected the TSA boundary line, and reached the RIS line, indicating that the expected sample size had been reached, and the result was true positive, further verifying that the HT group had a lower risk of recurrence than the non-HT group.

Multifocality

Concerning multifocality, 44 articles with 34,235 cases were included. The RIS was 20,849 cases. The TSA results illustrated that the cumulative Z-curve crossed the traditional threshold line, intersected with the TSA threshold line, and reached the RIS line, indicating that the expected sample size had been reached. The result was positive, further verifying that the HT group had a higher multifocality risk than the non-HT group.

Vascular invasion

Seventeen studies were included for vascular invasion, with 14,105 cases sample size, and the RIS was 24,373 cases.The TSA results showed that the cumulative Z-curve crossed the traditional threshold line and intersected with the TSA threshold line, but did not reach the RIS line, indicating that although the expected sample size was not reached, positive results were obtained in advance, further verifying that the risk of vascular invasion in the HT group was lower than that in the non-HT group.

Bilaterality

Eighteen studies were included to evaluate bilaterality, with a total sample size of 12783 cases, and the RIS was 42465 cases. TSA results showed that the cumulative Z-curve did not reach the TSA threshold line and RIS line, indicating that the expected sample size was not reached. In the future, required to validate the reliability of the conclusion that the risk of bilaterality is higher in the HT group than that in the non-HT group.

Discussion

No consensus exists on the association between PTC and HT. To resolve this controversy, this study was performed to evaluate the relationship between the two conditions using a meta-analysis. Our analysis revealed that HT was associated with improvements in the clinicopathological characteristics and better prognosis of patients with PTC with lower risk of extrathyroidal extension, lower risk of distant metastasis, lower risk of lymph node metastasis, lower risk of vascular invasion, lower risk of recurrence rate, and a higher 20-year survival rate. Multifocal and bilaterality were positively correlated with HT. Since multifocal and bilaterality are thought to be features associated with PTC development, rather than with its deterioration, these findings are consistent with previous reports of a positive association between HT and PTC development and a protective effect of HT on PTC development [48]. Besides, PTC with HT had a risk of perineural infiltration.

There have been a number of proposed hypotheses to explain the linkage between HT and PTC. From a histological perspective, Tamimi et al. [77] assessed the prevalence and severity of thyroiditis among three types of surgically resected thyroid tumors and found a significantly higher rate of lymphocytic infiltration in patients with PTC. Nevertheless, PTC with concurrent HT is associated with less aggressive disease, less frequent capsular invasion, and less nodal metastasis [22]. Our result supported the result that HT may decrease the risk of lymph node metastasis and vascular invasion in patients with PTC. Similarly, Yoon et al. [70] and Donangelo et al. [78] reported that PTC with HT was significantly associated with a lower incidence of lymph node metastasis.

Furthermore, our findings showed that PTC patients with HT were also less likely to develop recurrence and have a higher 20-year survival rate, which were in agreement with prior studies [41, 66]. Although we did not find the presence of HT indicates lower disease-specific deaths, a recent study by Hu et al. reported that patients with HT had lower rates of tumor recurrence, and lower disease-related mortality compared with patients without HT [79]. Kashima et al. [13] reported a 0.7% cancer specific mortality and a 95% relapse-free 10-year survival rate in patients with HT compared to a 5% mortality and 85% relapse-free 10-year survival rate without chronic thyroiditis. The lymphocytic infiltration of HT may be an immunological response with a cancer-retarding effect, contributing to a favorable outcome of PTC versus other thyroid cancers [80].

Hypotheses about the mechanism of a better prognosis in PTC patients with HT have been evaluated in different ways [17]. HT is a kind of autoimmune disease that leads to the destruction of thyroid follicles through an immune response to a thyroid specific antigen. As PTC cells originating from the follicular cells would express the thyroid specific antigen, auto-antibodies from coexisting HT might destroy the tumor cells in much the same way as in HT alone [81]. Additionally, the infiltrated lymphocytes in patients with PTC are likely to be cytotoxic T cells acting as carcinoma cell killers, secreting interleukin-1 that inhibits thyroid cancer cell growth [82]. In a study on BRAFV600E, Xing et al. reported a significantly lower prevalence of BRAFV600E mutation in patients with PTC and HT, suggesting that HT is less likely to be associated with poor prognostic outcomes [83].

Interestingly, we observed that PTC patients with HT were younge than PTC patients without HT. We found that the results among age-balanced were similar to our original outcomes. Nevertheless, in the age-imbalanced groups, there were no differences in lateral lymph node metastasis, extrathyroidal extension, extrathyroidal extension, recurrence, multifocality, and bilaterality between PTC patients with HT and PTC alone. A study by Lun et al. also demonstrated that patients with PTC and HT were younger [56]. Zhang et al. reported older age is a risk factors for BRAF mutation in PTC patients, especially in those without HT [84]. This result suggests that age may be one of the potential sources of bias. More studies are needed in the future with a larger sample size and rigorous design to confirm our findings.

The strengths of the current study need to be mentioned. This was an updated meta-analysis including more studies and more outcomes. There was no apparent publication bias, leading to the research results being more reliable and convincing. Besides, we used TSA to further validate our findings. However, residual confounding variables were a problem. Uncontrolled or unmeasured confounding factors have the potential for bias, and the possibility that residual confounders influenced the results cannot be ruled out. Our analysis was largely limited by the retrospective nature of most of the included studies where clinical details were usually not available. More prospective studies with longer follow-ups are needed to further elucidate this relationship.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis shows a clinical relationship between two disease entities. PTC patients with HT may have lower incidence of extrathyroidal extension, distant metastasis, lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion, and better prognosis than patients with PTC alone.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Ehlers M, Schott M. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and papillary thyroid cancer: are they immunologically linked? Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2014;25(12):656–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moon S, Chung HS, Yu JM, Yoo HJ, Park JH, Kim DS, et al. Associations between Hashimoto Thyroiditis and Clinical Outcomes of Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea). 2018;33(4):473–84. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2018.33.4.473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiersinga W.M. Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. In: HL Vitti P. Thyroid Diseases. Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. editorsSpringer; New York, NY, USA. 2018:205–47. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed R, Al-Shaikh S, Akhtar M. Hashimoto thyroiditis: a century later. Advances in anatomic pathology. 2012;19(3):181–. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3182534868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molnár C, Molnár S, Bedekovics J, Mokánszki A, Győry F, Nagy E, et al. Thyroid Carcinoma Coexisting with Hashimoto’s Thyreoiditis: Clinicopathological and Molecular Characteristics Clue up Pathogenesis. Pathology oncology research: POR. 2019;25(3):1191–7. doi: 10.1007/s12253-019-00580-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim H, Devesa SS, Sosa JA, Check D, Kitahara CM. Trends in Thyroid Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the United States, 1974–2013. Jama. 2017;317(13):1338–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skarpa V, Kousta E, Tertipi A, Anyfandakis K, Vakaki M, Dolianiti M, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of children with autoimmune thyroid disease. Hormones (Athens, Greece). 2011;10(3):207–14. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng R, Zhao M, Niu H, Yang KX, Shou T, Zhang GQ, et al. Relationship between Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and papillary thyroid carcinoma in children and adolescents. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2018;22(22):7778–87. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201811_16401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L, Li W, Ye H, Niu L. Impact of Hashimotoas thyroiditis on clinicopathologic features of papillary thyroid carcinoma associated with infiltration of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2018;11(5):2768–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Kim Y, Choi JW, Kim YS. The association between papillary thyroid carcinoma and histologically proven Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: a meta-analysis. European journal of endocrinology. 2013;168(3):343–9. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cipolla C, Sandonato L, Graceffa G, Fricano S, Torcivia A, Vieni S, et al. Hashimoto thyroiditis coexistent with papillary thyroid carcinoma. The American surgeon. 2005;71(10):874–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song E, Jeon MJ, Park S, Kim M, Oh HS, Song DE, et al. Influence of coexistent Hashimoto’s thyroiditis on the extent of cervical lymph node dissection and prognosis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Clinical endocrinology. 2018;88(1):123–8. doi: 10.1111/cen.13475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang J, Zeng W, Fang F, Yu T, Zhao Y, Fan X, et al. Clinical analysis of Hashimoto thyroiditis coexistent with papillary thyroid cancer in 1392 patients. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica: organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2017;37(5):393–400. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-1709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anil C, Goksel S, Gursoy A. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is not associated with increased risk of thyroid cancer in patients with thyroid nodules: a single-center prospective study. Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2010;20(6):601–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Rio P, Cataldo S, Sommaruga L, Concione L, Arcuri MF, Sianesi M. The association between papillary carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis: does it modify the prognosis of cancer? Minerva endocrinologica. 2008;33(1):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wetterslev J, Jakobsen JC, Gluud C. Trial Sequential Analysis in systematic reviews with meta-analysis. BMC medical research methodology. 2017;17(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0315-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahn D, Heo SJ, Park JH, Kim JH, Sohn JH, Park JY, et al. Clinical relationship between Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and papillary thyroid cancer. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden). 2011;50(8):1228–34. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.602109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babli S, Payne RJ, Mitmaker E, Rivera J. Effects of Chronic Lymphocytic Thyroiditis on the Clinicopathological Features of Papillary Thyroid Cancer. European thyroid journal. 2018;7(2):95–101. doi: 10.1159/000486367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bircan HY, Koc B, Akarsu C, Demiralay E, Demirag A, Adas M, et al. Is Hashimoto’s thyroiditis a prognostic factor for thyroid papillary microcarcinoma? European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2014;18(13):1910–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai YF, Wang QX, Ni CJ, Guo GL, Li Q, Wang OC, et al. The Clinical Relevance of Psammoma Body and Hashimoto Thyroiditis in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Large Case-control Study. Medicine. 2015;94(44):e1881. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carvalho M, Rosario P, Mourão G, Calsolari MJE. Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis does not influence the risk of recurrence in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma and excellent response to initial therapy. 2017;55(3):954–8. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1185-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Consorti F, Loponte M, Milazzo F, Potasso L, Antonaci A. Risk of malignancy from thyroid nodular disease as an element of clinical management of patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. European surgical research Europaische chirurgische Forschung Recherches chirurgicales europeennes. 2010;45(3–4):333–7. doi: 10.1159/000320954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordioli MI, Cury AN, Nascimento AO, Oliveira AK, Mello M, Saieg MA. Study of the histological profile of papillary thyroid carcinomas associated with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Arquivos brasileiros de endocrinologia e metabologia. 2013;57(6):445–9. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302013000600006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Côrtes MCS, Rosario PW, Mourão GF, Calsolari MR. Influence of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis on the risk of persistent and recurrent disease in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma and elevated antithyroglobulin antibodies after initial therapy. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2018;84(4):448–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobrinja C, Makovac P, Pastoricchio M, Cipolat Mis T, Bernardi S, Fabris B, et al. Coexistence of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis and papillary thyroid carcinoma. Impact on presentation, management, and outcome. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2016;28 Suppl 1:S70–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dvorkin S, Robenshtok E, Hirsch D, Strenov Y, Shimon I, Benbassat CA. Differentiated thyroid cancer is associated with less aggressive disease and better outcome in patients with coexisting Hashimotos thyroiditis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98(6):2409–14. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiore E, Rago T, Latrofa F, Provenzale MA, Piaggi P, Delitala A, et al. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is associated with papillary thyroid carcinoma: role of TSH and of treatment with L-thyroxine. Endocrine-related cancer. 2011;18(4):429–37. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giagourta I, Evangelopoulou C, Papaioannou G, Kassi G, Zapanti E, Prokopiou M, et al. Autoimmune thyroiditis in benign and malignant thyroid nodules: 16-year results. Head & neck. 2014;36(4):531–5. doi: 10.1002/hed.23331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girardi FM, Barra MB, Zettler CG. Papillary thyroid carcinoma: does the association with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis affect the clinicopathological characteristics of the disease? Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2015;81(3):283–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han LT, Hu JQ, Ma B, Wen D, Zhang TT, Lu ZW, et al. IL-17A increases MHC class I expression and promotes T cell activation in papillary thyroid cancer patients with coexistent Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Diagnostic pathology. 2019;14(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s13000-019-0832-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang BY, Hseuh C, Chao TC, Lin KJ, Lin JD. Well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma with concomitant Hashimoto’s thyroiditis present with less aggressive clinical stage and low recurrence. Endocrine pathology. 2011;22(3):144–9. doi: 10.1007/s12022-011-9164-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ieni A, Vita R, Magliolo E, Santarpia M, Di Bari F, Benvenga S, et al. One-third of an Archivial Series of Papillary Thyroid Cancer (Years 2007–2015) Has Coexistent Chronic Lymphocytic Thyroiditis, Which Is Associated with a More Favorable Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2017;8:337. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jara SM, Carson KA, Pai SI, Agrawal N, Richmon JD, Prescott JD, et al. The relationship between chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis and central neck lymph node metastasis in North American patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Surgery. 2013;154(6):1272–80. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeong JS, Kim HK, Lee CR, Park S, Park JH, Kang SW, et al. Coexistence of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis with papillary thyroid carcinoma: clinical manifestation and prognostic outcome. Journal of Korean medical science. 2012;27(8):883–9. Epub 2012/08/10. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.8.883 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3410235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kebebew E, Treseler PA, Ituarte PH, Clark OH. Coexisting chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis and papillary thyroid cancer revisited. World journal of surgery. 2001;25(5):632–7. doi: 10.1007/s002680020165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kashima K, Yokoyama S, Noguchi S, Murakami N, Yamashita H, Watanabe S, et al. Chronic thyroiditis as a favorable prognostic factor in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 1998;8(3):197–202. doi: 10.1089/thy.1998.8.197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim HS, Choi YJ, Yun JS. Features of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma in the presence and absence of lymphocytic thyroiditis. Endocrine pathology. 2010;21(3):149–53. doi: 10.1007/s12022-010-9124-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HG, Kim EK, Han KH, Kim H, Kwak JY. Pathologic spectrum of lymphocytic infiltration and recurrence of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Yonsei medical journal. 2014;55(4):879–85. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.4.879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SS, Lee BJ, Lee JC, Kim SJ, Jeon YK, Kim MR, et al. Coexistence of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with papillary thyroid carcinoma: the influence of lymph node metastasis. Head & neck. 2011;33(9):1272–7. doi: 10.1002/hed.21594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim SJ, Myong JP, Jee HG, Chai YJ, Choi JY, Min HS, et al. Combined effect of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and BRAF(V600E) mutation status on aggressiveness in papillary thyroid cancer. Head & neck. 2016;38(1):95–101. doi: 10.1002/hed.23854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim SK, Song KH, Lim SD, Lim YC, Yoo YB, Kim JS, et al. Clinical and pathological features and the BRAF(V600E) mutation in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma with and without concurrent Hashimoto thyroiditis. Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2009;19(2):137–41. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim SK, Woo JW, Lee JH, Park I, Choe JH, Kim JH, et al. Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis and BRAF V600E in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Endocrine-related cancer. 2016;23(1):27–34. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim KW, Park YJ, Kim EH, Park SY, Park DJ, Ahn SH, et al. Elevated risk of papillary thyroid cancer in Korean patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Head & neck. 2011;33(5):691–5. doi: 10.1002/hed.21518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim WW, Ha TK, Bae SK. Clinical implications of the BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. Journal of otolaryngology—head & neck surgery = Le Journal d’oto-rhino-laryngologie et de chirurgie cervico-faciale. 2018;47(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40463-017-0247-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim YS, Choi HJ, Kim ES. Papillary thyroid carcinoma with thyroiditis: lymph node metastasis, complications. Journal of the Korean Surgical Society. 2013;85(1):20–4. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2013.85.1.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Konturek A, Barczyński M, Nowak W, Wierzchowski W. Risk of lymph node metastases in multifocal papillary thyroid cancer associated with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Langenbeck’s archives of surgery. 2014;399(2):229–36. doi: 10.1007/s00423-013-1158-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kurukahvecioglu O, Taneri F, Yüksel O, Aydin A, Tezel E, Onuk E. Total thyroidectomy for the treatment of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis coexisting with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Advances in therapy. 2007;24(3):510–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02848773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kwak HY, Chae BJ, Eom YH, Hong YR, Seo JB, Lee SH, et al. Does papillary thyroid carcinoma have a better prognosis with or without Hashimoto thyroiditis? International journal of clinical oncology. 2015;20(3):463–73. doi: 10.1007/s10147-014-0754-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwon H, Choi JY, Moon JH, Park HJ, Lee WW, Lee KE. Effect of Hashimoto thyroiditis on low-dose radioactive-iodine remnant ablation. Head & neck. 2016;38 Suppl 1:E730–5. doi: 10.1002/hed.24080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee I, Kim HK, Soh EY, Lee J. The Association Between Chronic Lymphocytic Thyroiditis and the Progress of Papillary Thyroid Cancer. World journal of surgery. 2020;44(5):1506–13. doi: 10.1007/s00268-019-05337-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee YK, Park KH, Park SH, Kim KJ, Shin DY, Nam KH, et al. Association between diffuse lymphocytic infiltration and papillary thyroid cancer aggressiveness according to the presence of thyroid peroxidase antibody and BRAF(V600E) mutation. Head & neck. 2018;40(10):2271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lim JY, Hong SW, Lee YS, Kim BW, Park CS, Chang HS, et al. Clinicopathologic implications of the BRAF(V600E) mutation in papillary thyroid cancer: a subgroup analysis of 3130 cases in a single center. Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2013;23(11):1423–30. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hua Liu C-LQ, Zhi-Yong Shen, Fu Ji. The clinical evaluation of the relationship between papillary thyroid microcarcinoma and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9(5):8348–54. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu X, Zhu L, Cui D, Wang Z, Chen H, Duan Y, et al. Coexistence of Histologically Confirmed Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis with Different Stages of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma in a Consecutive Chinese Cohort. International journal of endocrinology. 2014;2014:769294. doi: 10.1155/2014/769294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lu ZW, Hu JQ, Liu WL, Wen D, Wei WJ, Wang YL, et al. IL-10 Restores MHC Class I Expression and Interferes With Immunity in Papillary Thyroid Cancer With Hashimoto Thyroiditis. Endocrinology. 2020;161(10). doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqaa062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lun Y, Wu X, Xia Q, Han Y, Zhang X, Liu Z, et al. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis as a risk factor of papillary thyroid cancer may improve cancer prognosis. Otolaryngology—head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2013;148(3):396–402. doi: 10.1177/0194599812472426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ma H, Li L, Li K, Wang T, Zhang Y, Zhang C, et al. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, nodular goiter or follicular adenoma combined with papillary thyroid carcinoma play protective role in patients. Neoplasma. 2018;65(3):436–40. doi: 10.4149/neo_2018_170428N317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marotta V, Guerra A, Zatelli MC, Uberti ED, Di Stasi V, Faggiano A, et al. BRAF mutation positive papillary thyroid carcinoma is less advanced when Hashimoto’s thyroiditis lymphocytic infiltration is present. Clinical endocrinology. 2013;79(5):733–8. doi: 10.1111/cen.12194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marotta V, Sciammarella C, Chiofalo MG, Gambardella C, Bellevicine C, Grasso M, et al. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis predicts outcome in intrathyroidal papillary thyroid cancer. Endocrine-related cancer. 2017;24(9):485–93. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mohamed SY, Ibrahim TR, Elbasateeny SS, Abdelaziz LA, Farouk S, Yassin MA, et al. Clinicopathological characterization and prognostic implication of FOXP3 and CK19 expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma and concomitant Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Scientific reports. 2020;10(1):10651. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67615-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nam HY, Lee HY, Park GC. Impact of co-existent thyroiditis on clinical outcome in papillary thyroid carcinoma with high preoperative serum antithyroglobulin antibody: a retrospective cohort study. Clinical otolaryngology: official journal of ENT-UK; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 2016;41(4):358–64. doi: 10.1111/coa.12520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park JY, Kim DW, Park HK, Ha TK, Jung SJ, Kim DH, et al. Comparison of T stage, N stage, multifocality, and bilaterality in papillary thyroid carcinoma patients according to the presence of coexisting lymphocytic thyroiditis. Endocrine research. 2015;40(3):151–5. doi: 10.3109/07435800.2014.977911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paulson LM, Shindo ML, Schuff KG. Role of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis in central node metastasis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Otolaryngology—head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2012;147(3):444–9. doi: 10.1177/0194599812445727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pilli T, Toti P, Occhini R, Castagna MG, Cantara S, Caselli M, et al. Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (CLT) has a positive prognostic value in papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) patients: the potential key role of Foxp3+ T lymphocytes. Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2018;41(6):703–9. doi: 10.1007/s40618-017-0794-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qu N, Zhang L, Lin DZ, Ji QH, Zhu YX, Wang Y. The impact of coexistent Hashimoto’s thyroiditis on lymph node metastasis and prognosis in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2016;37(6):7685–92. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4534-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ryu YJ, Yoon JH. Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis protects against recurrence in patients with cN0 papillary thyroid cancer. Surgical oncology. 2020;34:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2020.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh B, Shaha AR, Trivedi H, Carew JF, Poluri A, Shah JP. Coexistent Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with papillary thyroid carcinoma: impact on presentation, management, and outcome. Surgery. 1999;126(6):1070–6. doi: 10.1067/msy.2099.101431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang SW, Kang SH, Kim KR, Choi IH, Chang HS, Oh YL, et al. Do Helper T Cell Subtypes in Lymphocytic Thyroiditis Play a Role in the Antitumor Effect? Journal of pathology and translational medicine. 2016;50(5):377–84. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2016.07.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ye ZQ, Gu DN, Hu HY, Zhou YL, Hu XQ, Zhang XH. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, microcalcification and raised thyrotropin levels within normal range are associated with thyroid cancer. World journal of surgical oncology. 2013;11:56. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoon YH, Kim HJ, Lee JW, Kim JM, Koo BS. The clinicopathologic differences in papillary thyroid carcinoma with or without co-existing chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology: official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 2012;269(3):1013–7. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1732-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeng R, Lyu Y, Zhang G, Shou T, Wang K, Niu H, et al. Positive effect of RORγt on the prognosis of thyroid papillary carcinoma patients combined with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. American journal of translational research. 2018;10(10):3011–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zeng RC, Jin LP, Chen ED, Dong SY, Cai YF, Huang GL, et al. Potential relationship between Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and BRAF(V600E) mutation status in papillary thyroid cancer. Head & neck. 2016;38 Suppl 1:E1019–25. doi: 10.1002/hed.24149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Y, Dai J, Wu T, Yang N, Yin Z. The study of the coexistence of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2014;140(6):1021–6. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1629-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhu F, Shen YB, Li FQ, Fang Y, Hu L, Wu YJ. The Effects of Hashimoto Thyroiditis on Lymph Node Metastases in Unifocal and Multifocal Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Retrospective Chinese Cohort Study. Medicine. 2016;95(6):e2674. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhu Y, Zheng K, Zhang H, Chen L, Xue J, Ding M, et al. The clinicopathologic differences of central lymph node metastasis in predicting lateral lymph node metastasis and prognosis in papillary thyroid cancer associated with or without Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2016;37(6):8037–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kwon JH, Nam ES, Shin HS, Cho SJ, Park HR, Kwon MJ. P2X7 Receptor Expression in Coexistence of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. Korean journal of pathology. 2014;48(1):30–5. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2014.48.1.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tamimi DM. The association between chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis and thyroid tumors. International journal of surgical pathology. 2002;10(2):141–6. doi: 10.1177/106689690201000207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]