SUMMARY

In South Korea, the resurgence of mumps was noted primarily among school-aged children and adolescents since 2000. We analyzed spatial patterns in mumps incidence to give an indication to the geographical risk. We used National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System data from 2001 to 2015, classifying into three periods according to the level of endemicity. A geographic-weighted regression analysis was performed to find demographic predictors of mumps incidence according to district level. We assessed the association between the total population size, population density, percentage of children (age 0–19 years), timely vaccination rate of measles–mumps–rubella vaccines and the higher incidence rate of mumps. During low endemic periods, there were sporadic regional distributions of outbreak in the central and northern part of the country. During intermediate endemic periods, the increase of incidence was noted across the country. During high endemic period, a nationwide high incidence of mumps was noted especially concentrated in southwestern regions. A clear pattern for the mumps cluster shown through global spatial autocorrelation analysis from 2004 to 2015. The ‘non-timely vaccination coverage’ (P = 0·002), and ‘proportion of children population’ (P < 0·001) were the predictors for high mumps incidence in district levels. Our study indicates that the rate of mumps incidence according to geographic regions vary by population proportion and neighboring regions, and timeliness of vaccination, suggesting the importance of community-level surveillance and improving of timely vaccination.

Key words: Geographical, mumps, spatial, vaccine

INTRODUCTION

Mumps is an acute febrile illness characterized by swelling of parotid glands. The mumps incidence decreased dramatically after the widespread use of vaccine, mostly in combination with vaccines for measles and rubella (measles–mumps–rubella (MMR) vaccine). Mumps vaccination has been used globally during several decades, but the disease is still one of the leading pathogen among vaccine-preventable outbreaks in the world today [1]. More recently, mumps resurgence was noted in many countries despite high two-dose MMR vaccination coverage [2]. Suggested causes of resurgence vary by country and region, but there are evidences that insufficient vaccine efficacy, mismatch between vaccine and circulating virus, and intense social contacts may have contributed to the mumps outbreaks [3–5].

In South Korea, MMR vaccine has been included in NIP (National Immunization Program) since 1985 [6]. The vaccination schedule was updated with two MMR doses given at 12–15 months and 4–6 years in 1997. Following that, reported mumps cases decreased from 5000 to 8000 cases annually to <2000 cases per year [7]. In 2000s, however, the resurgence of mumps was noted primarily among school-aged children and adolescents.

The geographic differences in outbreak during the 2000s resurgence have not been assessed previously. As mumps tend to cluster geographically where susceptible population reside in close proximity, spatial analyses may bring important insight to detect and predict the incidence patterns of mumps. In this study, we sought to understand spatial patterns in mumps incidence to give an indication to the geographical risk of the disease in the settings with high MMR vaccination coverage.

METHODS

South Korea occupies around 100 032 km2, with population of approximately 50·2 million in 2013. It is divided into 16 provinces (si-do), which are subdivided into 252 districts (si-gun-gu). We grouped the provincial level according to their geographical proximities: Seoul-Incheon-Gyeonggi (northwest); Daejeon-Chungcheong (midwest); Gwangju-Jeolla (southwest); Gangwon (northeast); Daegu-Gyeongbuk (mideast); and Busan-Gyeongnam (southeast) (Supplementary Material).

In Korea, the case-based surveillance that used a set of case definition for suspected and confirmed mumps cases is being practiced. It is obligatory for all physicians to report the laboratory-confirmed or clinically suspected mumps cases to the KCDC (Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). The clinical case definition for diagnosis of mumps have been based on WHO (World Health Organization) definitions which were adapted for use in Korea: a case with acute onset of unilateral or bilateral tender, self-limiting swelling of the parotid or other salivary gland and without any other apparent cause.

Number of reported mumps cases was collected at district level from the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, from 2001 to 2015 [8]. The data cover population distribution by age, sex, and the date of disease onset. The address field contained in the dataset was used to locate the geographical region of occurrence. We used data from census to calculate the annual incidence rate. Indirect standardization was used to control for age [9].

We classified the 15 years of the surveillance period into three periods according to the level of endemicity: low endemicity (2001–2006; <20 cases per 100 000 per year), intermediate endemicity (2007–2012; 20–59 cases per 100 000 per year), and high endemicity (2013–2015; ⩾60 cases per 100 000 per year). For the direct comparison with a 3-year period of high endemicity, 6 years of low and intermediate endemicity periods were divided into two, respectively (2001–2003, 2004–2006; 2007–2009, 2010–2012). We grouped the 12 months of the year into four seasons according to academic calendar system in South Korea: Winter Break (January–February), the First Semester (March–July), Summer Break (August), and the Second Semester (September–December).

We used GeoDa software (version 1.8, The University of Chicago, IL, USA) to investigate for mumps clusters by spatial analyses. To visualize the difference in age-adjusted incidence between districts, we have divided into seven color scales. A geographic-weighted regression (GWR) analysis was performed to find demographic predictors of mumps incidence according to district level. Because mumps is a highly transmissible disease with spatial dependency according to variable population susceptibility, GWR explains the changes in the independent variable depending on the geographic location. Total population size, population density, percentage of children (age 0–19 years), and timely vaccination rate of MMR vaccines (12–15 months and 4–6 years, surveyed in 2005–2012) were tested for correlations to the higher incidence rate of mumps in corresponding district.

The population, density, childhood percentage, and the timely vaccination coverage rate data were derived from the National Statistics database [9]. The current vaccination schedule recommends the administration of one dose of MMR by age 12–15 months and an additional dose at 4–6 years. Therefore, the defined non-timely vaccination coverage was not receiving of the recommended number of doses of MMR doses by age of 15 month and 6 year.

To examine if incidence is clustered into specific regions, we have performed spatial autocorrelation analysis using Moran's Index. To find the ‘hot spots’ (high values next to high, HH), and ‘cold spots’ (low values next to low, LL), local indicators of spatial association (LISA) analysis was performed.

This study was approved by Seoul National University Institutional Review Board (IRB No. SNU 16-01-050).

RESULTS

For the low endemic periods of 2001–2003 and 2004–2006, the total numbers of cases were 3950 and 5696 cases, respectively (Table 1). The reported cases have increased during intermediate endemic periods of 2007–2009 and 2010–2012 by 15 498 and 19 723 cases, and during high endemic period of 2013–2015, the total reported number was 65 758 cases. Around half of cases were reported from Seoul-Incheon-Gyeonggi area during low and intermediate endemic period, whereas during high endemic period of 2013–2015, around 45% of cases were reported from Gwangju-Jeolla and Busan-Ulsan-Gyeongnam areas. Change in the seasonal variation in the number of cases was apparent, with proportion of cases occurring during the second semester (September–December) has increased from 26·8% in 2001–2003 to 40·1% in 2013–2015.

Table 1.

Characteristics of mumps cases during the three periods in the Republic of Korea: low (2001–2006), intermediate (2007–2012), and high endemicity (2013–2015)

| 2001–2003 | 2004–2006 | 2007–2009 | 2010–2012 | 2013–2015 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) |

| Total cases | 3950 | 5696 | 15 498 | 19 723 | 65 758 | |||||

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||

| 0–5 | 897 | (22·7) | 895 | (15·7) | 1928 | (12·4) | 3136 | (15·9) | 9304 | (14·1) |

| 6–11 | 1819 | (46·1) | 1721 | (30·2) | 4153 | (26·8) | 4895 | (24·8) | 12 504 | (19·0) |

| 12–14 | 717 | (18·2) | 1471 | (25·8) | 2799 | (18·1) | 3537 | (17·9) | 12 105 | (18·4) |

| 15–17 | 361 | (9·1) | 1298 | (22·8) | 5033 | (32·5) | 5117 | (25·9) | 20 036 | (30·5) |

| ⩾18 | 156 | (3·9) | 311 | (5·5) | 1585 | (10·2) | 3038 | (15·4) | 11 809 | (18·0) |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 1463 | (37·0) | 1915 | (33·6) | 5081 | (32·8) | 6486 | (32·9) | 22 281 | (33·9) |

| Male | 2487 | (63·0) | 3781 | (66·4) | 10 417 | (67·2) | 13 237 | (67·1) | 43 477 | (66·1) |

| Geographic area | ||||||||||

| Seoul-Incheon-Gyeonggi | 2076 | (52·6) | 3196 | (56·1) | 8169 | (52·7) | 9487 | (48·1) | 21 659 | (32·9) |

| Daejeon-Chungcheong | 336 | (8·5) | 621 | (10·9) | 1046 | (6·7) | 2506 | (12·7) | 5935 | (9·0) |

| Gwangju-Jeolla | 469 | (11·9) | 191 | (3·4) | 680 | (4·4) | 974 | (4·9) | 16 467 | (25·0) |

| Gangwon | 150 | (3·8) | 321 | (5·6) | 537 | (3·5) | 823 | (4·2) | 2309 | (3·5) |

| Daegu-Gyeongbuk | 451 | (11·4) | 504 | (8·8) | 3668 | (23·7) | 1268 | (6·4) | 4492 | (6·8) |

| Busan-Ulsan-Gyeongnam | 327 | (8·3) | 768 | (13·5) | 1319 | (8·5) | 3471 | (17·6) | 13 694 | (20·8) |

| Jeju | 141 | (3·6) | 95 | (1·7) | 79 | (0·5) | 1194 | (6·1) | 1202 | (1·8) |

| Seasonality | ||||||||||

| Winter Break (January–February) | 316 | (8·0) | 408 | (7·2) | 970 | (6·3) | 1703 | (8·6) | 6725 | (10·2) |

| First Semester (March–July) | 2357 | (59·7) | 2903 | (51·0) | 9003 | (58·1) | 9152 | (46·4) | 28 220 | (42·9) |

| Summer Break (August) | 220 | (5·6) | 349 | (6·1) | 931 | (6·0) | 1291 | (6·5) | 4176 | (6·4) |

| Second Semester (September–December) | 1057 | (26·8) | 2026 | (35·6) | 4594 | (29·6) | 7577 | (38·4) | 26 337 | (40·1) |

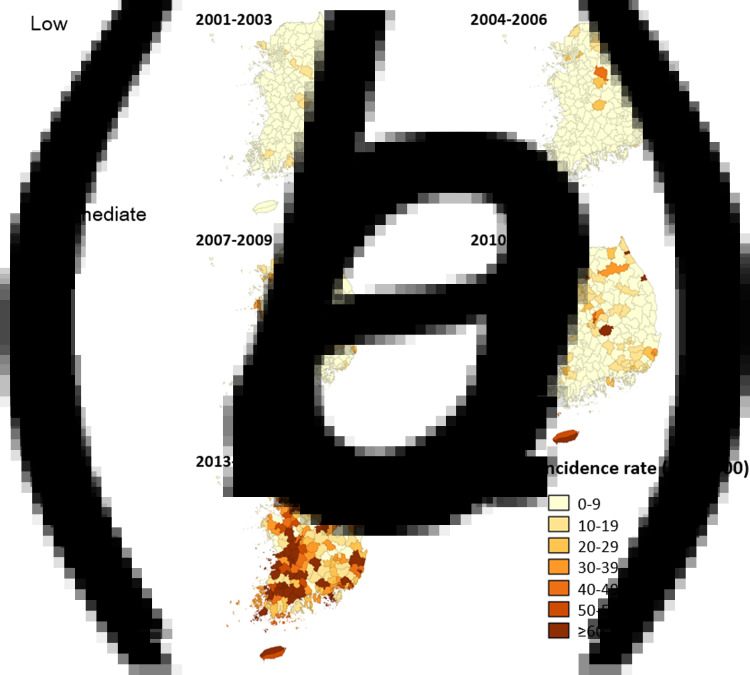

Figure 1 showed variation in mumps incidence rates of districts according to surveillance years. During low endemic periods of 2001–2003 and 2004–2006, there were sporadic regional distributions of outbreak in the central and northern part of the country. During intermediate endemic periods of 2007–2009 and 2010–2012, the increase of incidence was noted across the country from Seoul-Incheon-Gyeonggi region to Busan-Ulsan-Gyeongnam region. During high endemic period of 2013–2015, a nationwide high incidence of mumps was noted especially concentrated in Gwangju-Jeolla and Busan-Ulsan-Gyeongnam regions that reported more than 60/1 00 000 cases per year.

Fig. 1.

Incidence rate per 100 000/year of mumps during the three periods in the Republic of Korea: (a) low (2001–2006), (b) intermediate (2007–2012), and (c) high endemicity (2013–2015).

There was a clear pattern for the mumps cluster shown through global spatial autocorrelation analysis (Table 2). A significant autocorrelation was found within the mumps incidence in four surveillance periods of 2004–2006, 2007–2009, 2010–2012, and 2013–2015.

Table 2.

Global spatial autocorrelation analysis of mumps incidence in the Republic of Korea, 2001–2015

| Moran's Index | Z | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2003 | −0·01 | −0·14 | 0·462 |

| 2004–2006 | 0·20 | 5·76 | <0·001 |

| 2007–2009 | 0·48 | 13·75 | <0·001 |

| 2010–2012 | 0·12 | 3·58 | 0·003 |

| 2013–2015 | 0·24 | 7·00 | <0·001 |

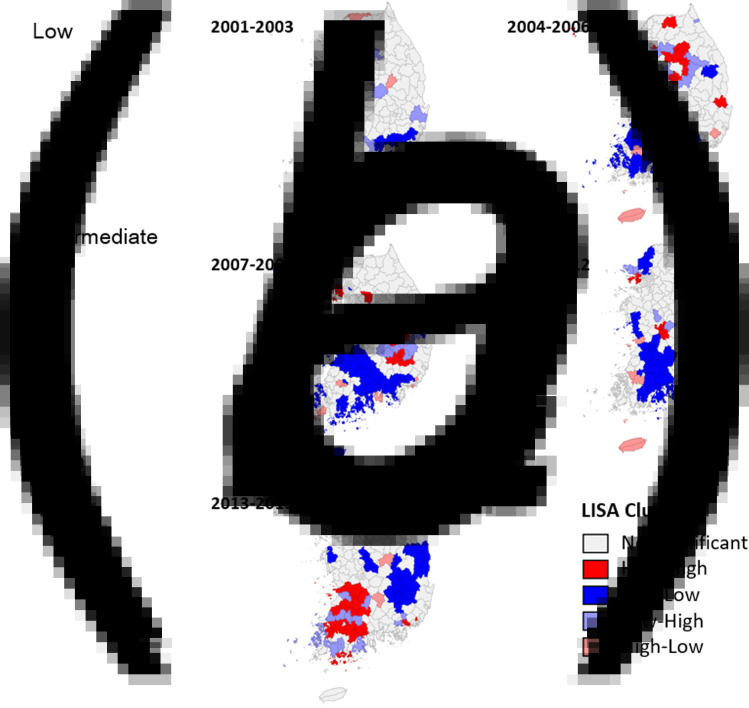

Map showing the dynamics of clustering are summarized in Fig. 2. During low endemic periods, the HH clusters were mostly confined to Seoul-Incheon-Gyeonggi and Gangwon regions. During high endemic period of 2013–2015, most of the Gwangju-Jeolla regions were with high-low (HL) or high-high (HH) clusters. These regions showed the core ‘cold spot’ clusters consistently during 2004–2006, 2007–2009, and 2010–2012.

Fig. 2.

Cluster map of mumps incidence during the three periods in the Republic of Korea: (a) low (2001–2006), (b) intermediate (2007–2012), and (c) high endemicity (2013–2015). Hot spots, marked with red color, are the regions where prevalence of self and neighboring regions were all high; cold spots, marked with blue color, are the regions where prevalence of self and neighboring regions were all low.

The result of GWR model to detect demographic predictor of mumps incidence is summarized in Table 3. The ‘un-timely vaccination coverage’ was a significant predictor of mumps incidence during 2010–2012 period (Coeff. 0·66, P = 0·002). The ‘proportion of children population’ was a predictor during high endemic period of 2013–2015 (Coeff. 2·68, P < 0·001).

Table 3.

Geographic-weighted regression of demographic predictors of mumps incidence in the Republic of Korea, 2001–2015

| Variables* | Coeff. | s.e. | t | P value | Log-likelihood | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2003 | ||||||

| Constant | −0·53 | 4·47 | −0·12 | 0·906 | −674·3 | 1360·66 |

| Coverage | 0·04 | 0·06 | 0·65 | 0·513 | ||

| Population | −2·83e−006 | 2·25e−006 | −1·26 | 0·207 | ||

| Density | 0·06 | 0·04 | 1·41 | 0·160 | ||

| Children | 0·02 | 0·08 | 0·31 | 0·756 | ||

| 2004–2006 | ||||||

| Constant | −9·74 | 6·23 | −1·56 | 0·118 | −761·9 | 1535·9 |

| Coverage | 0·14 | 0·08 | 1·78 | 0·075 | ||

| Population | −2·16e−006 | 3·13e−006 | −0·68 | 0·491 | ||

| Density | 0·07 | 0·06 | 1·15 | 0·248 | ||

| Children | 0·07 | 0·11 | 0·65 | 0·517 | ||

| 2007–2009 | ||||||

| Constant | −12·87 | 11·37 | −1·13 | 0·258 | −916·6 | 1845·2 |

| Coverage | 0·22 | 0·14 | 1·50 | 0·133 | ||

| Population | 9·41e−006 | 5·729e−006 | 1·64 | 0·100 | ||

| Density | 0·01 | 0·10 | 0·14 | 0·892 | ||

| Children | −0·03 | 0·19 | −0·17 | 0·866 | ||

| 2010–2012 | ||||||

| Constant | −50·45 | 16·69 | −3·02 | 0·003 | −1008·3 | 2028·6 |

| Coverage | 0·66 | 0·21 | 3·09 | 0·002 | ||

| Population | −6·59e−006 | 8·34e−006 | −0·79 | 0·430 | ||

| Density | 0·09 | 0·15 | 0·56 | 0·570 | ||

| Children | 0·48 | 0·28 | 1·69 | 0·091 | ||

| 2013–2015 | ||||||

| Constant | 16·55 | 46·11 | 0·36 | 0·720 | −1263·3 | 2538·6 |

| Coverage | −0·38 | 0·58 | −0·64 | 0·521 | ||

| Population | −7·58e−006 | 2·32e−005 | −0·33 | 0·744 | ||

| Density | −0·34 | 0·42 | −0·81 | 0·421 | ||

| Children | 2·68 | 0·78 | 3·41 | <0·001 |

AIC, Akaike Information Criterion.

Coverage, timely vaccination coverage (first dose by 15 month, second dose by 6 years); population, annual mid-year population; density, population density; children, proportion of childhood population (0–19 years).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that there were clusters in mumps incidence across the different geographical regions in South Korea, which may have been affected by the untimely vaccination and the regional proportion of childhood population. Our spatial scan statistic identified that during the intermediate and high endemic period, the regions with lower degree of timely MMR vaccination and higher proportion of childhood population was significantly susceptible to mumps incidence.

The adequate level of herd protection is attained by the MMR vaccination coverage which can result in outbreak in small clusters without widespread transmission of the mumps. As the MMR vaccination coverage becomes close to the level for herd protection in South Korea by 98·3% in 2012, small changes may become important [10]. Timeliness of MMR vaccination is of great significance in such circumstances. In a survey conducted in USA in 2000, only 73·2% of children have received at least one dose of MMR at recommended age [11]. Extending the survey up to 2002, there were geographical differences in timeliness of MMR vaccination across the country [12]. In 2005 mumps outbreak in the USA, some of severely affected states were with lower timely MMR vaccination coverage rate compared with national average of 74·1% (s.e., 0·3): Illinois (73·4%), Iowa (69·3%), Kansas (73·7%), Minnesota (73·5%), Missouri (77·0%), Nebraska (70·7%), South Dakota (66·4%), and Wisconsin (70·1%) [2, 12]. A survey that assessed 753 Korean children in 2007 showed that parental unawareness of necessity for vaccination and its schedule was amongst the most important factor for non-timely administration of MMR vaccine [13]. Although there are other possibilities for the recent increase of mumps with geographic clusters, improving heterogeneity in the timely receipt of MMR vaccine may induce a better herd protection in the community which will then affect the mumps incidence at the national level as well.

As the age structures within the community vary, the districts with high childhood population showed vulnerability to mumps outbreak during high endemic period in South Korea. The population age structure and composition were known to affect the disease transmission and vaccine impact in various levels. The changes to a population's demographic structure may affect the spread of disease through change in the patterns of household and the community contacts [14]. During the pandemic influenza A/H1N1 outbreak in 2009, a Canadian modeling study suggested the difference in age distribution of the population and pre-existing immunity level will affect the disproportionate transmission of the disease [15]. As many reports suggest shift in age distribution of mumps in countries with high MMR vaccination coverage rate, the regional population age structure may pose vulnerability to mumps outbreak over time [2, 16].

LISA analysis compared between local averages to global averages for mumps incidence, thereby assessing the local association between data. Our study has identified geographic areas of significant clustering of mumps incidence loco-regionally. Our finding, the recent increased incidence of mumps in Gwangju-Jeolla area, showed a cluster analysis of LL during low and intermediate endemicity during 2004–2012, which has dramatically changed to HH across the region. The low endemicity demonstrated as ‘LL’ in these areas may have reduced circulation of mumps virus, thus less natural boostering effect of mumps. The accumulation of such ‘more susceptible’ individuals may have affected outbreak-prone state in these geographic regions. Previously, it has been suggested that resurgence in pertussis incidence may be due to less chance of natural immune boosting [17]. This has not been demonstrated in case of mumps, however from our data, it is plausible that the diminished outbreaks for 10 years may have led to accumulation of vulnerable susceptible in southwestern area, and then turned into the ‘hot spot’ during the high endemic period in 2013–2015. Although our analysis has not fully elucidated the role of population immunity on the geographic difference in mumps incidence, it may suggest that immune waning and susceptibility to mumps may be important determinant of outbreak dynamics.

There are several limitations to our study. The observed clusters may have been overestimated or underestimated because the data were derived from passively reported surveillance, which cannot exclude the possibility of biased reporting of the cases. Mumps cases can be missed by surveillance, or other viral or bacterial pathogen may present the symptoms that resemble those of mumps. Further, the vaccination factors related to mumps incidence have not been well demonstrated because of unavailability of vaccination coverage data at individual level. Despite the limitations, our data have certain strengths. This is the first attempt to conduct exploratory data analysis on transmission of mumps according to time and space from a country with population of approximately 50 million with relatively strong vaccination system. During the surveillance period, there were no significant changes in mumps surveillance system and vaccination coverage rates. Moreover, our data show that there is a clear correlation between the quality of vaccination program and the population structure and the incidence of mumps. For pathogens directly transmitted from person-to-person such as mumps, disease outbreak may cluster in geographic place where the susceptible population is large and dense. Timely and adequate vaccination coverage may interrupt these processes over large geographic areas.

In this study, we intended to demonstrate the transmission pattern of mumps by space in South Korea during the past 15 years that might inform public health planning and future vaccination strategies. Our study indicates that the rate of mumps incidence according to geographic regions vary by population proportion and neighboring regions, and timeliness of MMR vaccination, suggesting the importance of community-level surveillance and strengthening of vaccination program. For instance, in regions with higher proportion of childhood population, an enhanced surveillance of mumps can be introduced that include active surveillance and timely reporting of suspected cases. Improving of timely vaccination coverage may be attained through public programs such as text message reminders and pre-school certificate of the second dose MMR vaccination. We recommend further researches to determine if population structure and non-timely coverage rate are associated with the temporal and spatial variation in other vaccine-preventable disease epidemiology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study did not receive any financial support.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268817000899.

click here to view supplementary material

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Galazka AM, Robertson SE, Kraigher A. Mumps and mumps vaccine: a global review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 1999; 77: 3–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dayan GH, et al. Recent resurgence of mumps in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 2008; 358: 1580–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cordeiro E, et al. Mumps outbreak among highly vaccinated teenagers and children in the central region of Portugal, 2012–2013. Acta Medica Portuguesa 2015; 28: 435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sane J, et al. Epidemic of mumps among vaccinated persons, The Netherlands, 2009–2012. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2014; 20: 643–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braeye T, et al. Mumps increase in Flanders, Belgium, 2012–2013: results from temporary mandatory notification and a cohort study among university students. Vaccine 2014; 32: 4393–4398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi KM. Reemergence of mumps. Korean Journal of Pediatrics 2010; 53: 623–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park SH. Resurgence of mumps in Korea. Infection and Chemotherapy 2015; 47: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (http://is.cdc.go.kr). Accessed 16 April 2003.

- 9.National Statistical Office. Korean Statistical Information Service (http://www.kosis.kr). Accessed 16 April 2003.

- 10.Choe YJ, et al. Comparative estimation of coverage between national immunization program vaccines and non-NIP vaccines in Korea. Journal of Korean Medical Science 2013; 28: 1283–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luman ET, et al. Timeliness of childhood immunizations. Pediatrics 2002; 110: 935–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luman ET, et al. Timeliness of childhood immunizations: a state-specific analysis. American Journal of Public Health 2005; 95: 1367–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeong YW, et al. Timeliness of MMR vaccination and barriers to vaccination in preschool children. Epidemiology and Infection 2011; 139: 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omran AR. The epidemiologic transition. A theory of the Epidemiology of population change. 1971. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2001; 79: 161–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geard N, et al. The effects of demographic change on disease transmission and vaccine impact in a household structured population. Epidemics 2015; 13: 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takla A, et al. Mumps epidemiology in Germany 2007–11. Eurosurveillance 2013; 18: 20557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavine JS, King AA, Bjørnstad ON. Natural immune boosting in pertussis dynamics and the potential for long-term vaccine failure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2011; 108: 7259–7264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268817000899.

click here to view supplementary material