Abstract

Background:

Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention requires engagement throughout the PrEP care continuum. Using data from a PrEP navigation program, we examine reasons for PrEP discontinuation.

Setting:

Participants were recruited from New York City Health Department Sexual Health Clinics with PrEP navigation programs.

Methods:

Participants completed a survey and up to three interviews about PrEP navigation and use. This analysis includes 94 PrEP initiators that were PrEP-naïve prior to their clinic visit, started PrEP during the study, and completed at least two interviews. Interview transcripts were reviewed to assess reasons for PrEP discontinuation.

Results:

Approximately half of PrEP initiators discontinued PrEP during the study period (n=44; 47%). Most participants (71%) noted systemic issues (insurance or financial problems, clinic or pharmacy logistics, and scheduling barriers) as reasons for discontinuation. One-third cited medication concerns (side effects, potential long-term side effects, and medication beliefs; 32%) and behavioral factors (low relevance of PrEP due to sexual behavior change; 34%) as contributing reasons. Over half (53.5%) highlighted systemic issues alone, while an additional 19% attributed discontinuation to systemic issues in combination with other factors. Of those who discontinued, approximately one-third (30%) restarted PrEP during the follow-up period, citing resolution of systemic issues or behavior change that increased PrEP relevance.

Conclusion:

PrEP continuation is dependent on interacting factors and often presents complex hurdles for patients to navigate. To promote sustained engagement in PrEP care, financial, clinic, and pharmacy barriers must be addressed and counseling and navigation should acknowledge factors beyond sexual risk that influence PrEP use.

Keywords: Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), Discontinuation, Restart, Barriers, Patterns of Use

INTRODUCTION

Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention is effective in reducing HIV acquisition when taken consistently.1 Successful PrEP care requires patient engagement throughout the PrEP care continuum, from identifying HIV infection risk to initiating PrEP to retention in care.2 While PrEP use in the United States has steadily increased since its approval, substantial unmet need remains3–6 and several studies have documented the challenges in PrEP uptake, retention in care, and continued use, particularly among women and communities of color.7–15 Furthermore, evidence suggests that patterns of PrEP use are not continuous,16 and some patients may prefer to use PrEP episodically or adjust their use as their HIV exposure and behaviors shift.17–22 Existing studies report wide variation in discontinuation rates depending on the population studied and length of follow-up, ranging from 4% of initiators to 69%; less is known about the proportion of patients who discontinue and then restart PrEP use.8,11,13,23–27

Several studies have explored demographic correlates of PrEP persistence, and have found higher discontinuation rates associated with factors traditionally associated with lack of health care access, including younger age, Black race, lack of insurance, lower education, and homelessness.11,12,14,15,28,29 Fewer have looked at behavioral correlates, and these data are equivocal, with some studies finding higher discontinuation among individuals who report substance use or recent STI infection, and others finding no relationship or lower discontinuation rates associated with these factors.11,12,28

Limited research has examined specific patient-provided reasons for stopping PrEP using interview data. In past research, reasons given for PrEP discontinuation include insurance and financial barriers; limited access to providers, facilities, and medication; changes in perceived HIV risk; medication concerns; preference for other methods of HIV prevention; and seroconversion.8–10,12,13,15,26,30,31 However, many existing studies rely on medical record data to track continuation and reasons for discontinuation and therefore provide little context for the decision to discontinue and have large amounts of missing data.8,11,13,15,23 Others rely on small samples of those that discontinue10,23,30 or explore correlates of discontinuation, not reasons provided by the patient.27,32 Furthermore, these studies frequently report one reason for discontinuation and seldom explore the multiple factors that contribute to the decision to stop or pause PrEP use.

This analysis examines patterns of PrEP use, specifically discontinuation, among patients enrolled in a PrEP Navigation program at publicly funded Sexual Health Clinics (SHCs) in New York City (NYC). We analyzed qualitative interview data to assess reasons for discontinuation, allowing participants to identify important factors in their own words through open-ended prompts, and observed the proportion that subsequently restarted PrEP use. Our mixed methods design allows for a more nuanced understanding of patterns of use, including the ways in which these motivations interact.

METHODS

Study Design

Project IMPrOVE was a longitudinal mixed-methods study conducted as a supplemental evaluation of a novel PrEP navigation program implemented in eight public SHCs in NYC. PrEP navigation services included PrEP education (information about PrEP; adherence and decision-making counseling; potential side effects; and required clinical follow up) and benefits counseling (payment options and assistance programs for PrEP). Patients that opted to start PrEP received a referral to another clinic for ongoing PrEP prescriptions and monitoring; some sites provided a 30-day supply of PrEP (and up to two refills) for immediate PrEP start. Further details of the SHC PrEP navigation program have been reported elsewhere.33 Between February 2017 and August 2018, participants who attended one of the SHCs and were eligible for the navigation program were recruited for Project IMPrOVE during triage at the start of their appointment, regardless of their decision to use PrEP; 283 individuals were recruited. Approximately four weeks after their SHC visit, participants completed an online survey and 30-minute interview about their experience with the PrEP navigation program, including whether or not they had initiated PrEP. Participants were contacted to schedule their second interview approximately three months after their initial interview and their third interview roughly three months later. Participants were compensated up to $100 for their participation in the survey and interviews. All study participants provided informed consent and study procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and approved by the Hunter College and the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Institutional Review Boards.

Analytic Sample

In our analytic sample, we retained participants who completed at least one follow-up interview and were first time PrEP users (excluding those with current or prior PrEP use at study enrollment). We decided to limit our sample to PrEP-naïve participants in order to focus on reasons for discontinuation among first-time PrEP users and reduce ambiguity in our analysis regarding the definition of a “re-start.” We further restricted our sample by removing participants who declined to start PrEP at any point during the study period. This analysis of PrEP use patterns includes 94 PrEP initiators that started PrEP at any point during the study period. The qualitative analysis focuses on the 44 participants who reported discontinuing PrEP during the study period. The vast majority (86%, n=38) of these participants completed all three interviews, while 11% (n=5) and 3% (n=1) completed only the initial and 3-month interview and initial and 6-month interview, respectively.

Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis

Participants completed an online survey at the time of their first interview that asked about demographics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, gender identity), recent sexual behavior (e.g., number of partners and total and condomless insertive and receptive sex acts in the last 30 days), and scales assessing HIV risk perception and PrEP knowledge and attitudes. Analyses of the impact of the above quantitative measures on PrEP initiation and other cascade outcomes are reported elsewhere.34 In this analysis, these measures are used to describe the sample (using frequencies) and examine any demographic differences in our key outcome, PrEP discontinuation, using independent T-tests and Chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

Initial semi-structured interviews assessed participants’ experience with PrEP navigation and referral at SHCs, their decision-making around accepting or rejecting PrEP, and their experience receiving PrEP at a referral clinic (if applicable). For those who declined a PrEP referral, follow-up interviews probed whether they had reconsidered or started PrEP since their prior interview. For those who accepted PrEP, follow-up interviews explored whether or not the participant had continued PrEP and the barriers or facilitators to PrEP use, including reasons for medication “breaks,” PrEP discontinuation, or PrEP restarts. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish by trained interviewers, audio recorded, and transcribed. Transcripts of participants who had any PrEP use throughout the study were reviewed to understand the PrEP use trajectory, including initiation, continuation, discontinuation, restart, and breaks in PrEP use. Data analysis was conducted by one primary coder (ZDU) who inductively developed codes for reasons for discontinuation and restart of PrEP. Codes were reviewed by another member of the research team (SAG) and revised to ensure conceptual clarity. The codebook was then applied by ZDU and reviewed for consistency, meaning, and precision by SAG; any differences were resolved through discussion.

Operationalization of PrEP continuation, discontinuation, and restarts

Based on interview transcripts, a dichotomous variable was created for our primary outcome, PrEP discontinuation, which was defined as the participant reporting a stop in PrEP use for a period of at least two weeks since their last interview; participants who did not discontinue were coded as “continuers.” Participants who discontinued PrEP and then reported resuming PrEP use at any interview were coded as both “discontinuers” and “restarters.” Participants who reported stopping PrEP for less than two weeks were coded as having a “break” in PrEP use, but not a discontinuation. Existing research has not consistently defined PrEP discontinuation. Our two-week criterion for defining PrEP discontinuation was informed by our qualitative analysis; participants who stopped PrEP use for two weeks or less discussed these breaks as “temporary” stops in use, with the intention of continuing taking PrEP (i.e., missing occasional pills due to not going home after work or a dislike of taking pills; delays in obtaining prescription refill). In contrast, the vast majority of participants that had gaps in their PrEP use of longer than two weeks described their behavior as a discontinuation with no intent to restart at the time (i.e., no longer sexually active) or no anticipation of restarting in the immediate future (i.e., issue with insurance that is not easily resolved), whether or not they eventually restarted PrEP use. Furthermore, we observed that participants who had intentions to continue using PrEP but had a gap in use of longer than two weeks were required by their provider to get retested before restarting and therefore aligned with our distinction between a break and a discontinuation. One similar study that explored discontinuation defined it as greater than 14 days off PrEP based on pharmacodynamic data.13

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

We enrolled 283 participants; this analysis excludes participants that did not complete at least one follow-up interview (n=64, 23%) and those who were currently using PrEP or had a history of PrEP use (n=44, 16%). Of the remaining 175 participants, we excluded approximately half (n=81, 46%) who did not start PrEP at any point during the study period. The remaining 94 PrEP initiators ranged in age from 18 to 64 (M=30.4, SD=8.7). Consistent with other data on PrEP patients at NYC SHCs, almost 94% of participants were cisgender men and the majority identified as racial/ethnic minorities: 40.6% Hispanic/Latinx, 22.9% non-Hispanic Black, 22.9% non-Hispanic White, and 13.6% other non-Hispanic races. Thirty-six participants (38.3%) reported four or more sexual partners in the past 30 days, with 51.1% reporting condomless insertive sex, and 42.6% reporting condomless receptive sex. Other demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of PrEP Initiators (n=94)

| Total Sample (n=94) n (%) | PrEP Continuers1 (n=50) n (%) | PrEP Discontinuers2 (n=44) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age 18–29 years 30 years and older |

52 (55.9%) 41 (44.1%) |

23 (46.9%) 26 (53.1%) |

29 (65.9%)† 15 (34.1%) |

|

Gender Cisgender Man Cisgender Woman Transgender/Gender Fluid |

88 (93.6%) 2 (2.1%) 4 (4.3%) |

45 (90.0%) 2 (4.0%) 3 (6.0%) |

43 (97.7%) -- 1 (2.3%) |

|

Race Hispanic/Latinx Non-Hispanic Black Non-Hispanic White Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander Non-Hispanic Multiracial/Other |

39 (41.5%) 20 (21.3%) 22 (23.4%) 6 (6.4%) 7 (7.4%) |

22 (44.0%) 12 (24.0%) 12 (24.0%) 2 (4.0%) 2 (4.0%) |

17 (38.6%) 8 (18.2%) 10 (22.7%) 4 (9.1%) 5 (11.4%) |

|

Insurance Status at study enrollment Uninsured Privately Insured Publicly Insured |

26 (28.6%) 43 (47.3%) 22 (24.2%) |

11 (23.4%) 21 (44.7%) 15 (31.9%) |

15 (34.1%) 22 (50.0%) 7 (15.9%) |

|

Number of Sex Partners in last 30 days at study enrollment

0 1–3 4 or more |

7 (7.4%) 51 (54.3%) 36 (38.3%) |

3 (6.0%) 28 (56.0%) 19 (38.0%) |

4 (9.1%) 23 (52.3%) 17 (38.6%) |

|

Any condomless insertive sex in last 30 days at study enrollment

No Yes |

44 (48.9%) 46 (51.1%) |

22 (46.8%) 25 (53.2%) |

22 (51.2%) 21 (48.8%) |

|

Any condomless receptive sex in last 30 days at study enrollment

No Yes |

54 (57.4%) 40 (42.6%) |

29 (58.0%) 21 (42.0%) |

25 (56.7%) 19 (43.2%) |

| How likely do you think you are to get HIV in your lifetime (range 0–100)? (Mean, Standard Deviation) | 27.1, 24.5 | 25.5, 24.1 | 29.0, 25.1 |

|

I worry about getting HIV... Most/All of the time Rarely/Some of the time |

40 (42.6%) 54 (57.4%) |

26 (52.0%)* 24 (48.0%) |

14 (31.8%) 30 (68.2%) |

p < .05.

p = .07

PrEP Continuers: Participants who initiated and continued using PrEP throughout the study period

PrEP Discontinuers: Participants who initiated PrEP and reported a stop in PrEP use for a period of at least two weeks, regardless of whether they restarted at a later point.

PrEP Continuation and Discontinuation

Of the 94 PrEP initiators, 46.8% (n=44) reported discontinuing PrEP during the study period. As presented in Table 1, there were no statistically significant differences between PrEP continuers and PrEP discontinuers by demographic factors (age, race/ethnicity, insurance status), sexual behavior or HIV risk perception. A higher percentage of continuers reported that they worry about HIV all or most of the time at study start (52.0%), compared to discontinuers (31.8%).

The most common reasons for PrEP discontinuation fell into three broad categories: systemic issues, medication concerns, and behavioral factors. Illustrative quotes for each category, as well as the sub-themes within each category, are presented in Table 2. One participant declined to give any reason for discontinuation and is excluded from percentages, tables, and figures. The majority of participants (n=31, 72.1%) reported that systemic issues contributed to their PrEP discontinuation. Descriptions of systemic issues fell into three sub-themes. First, insurance or financial problems (n=18, 41.9%) included sub-optimal insurance coverage, lapses in insurance, earning too much to qualify for medication assistance but not enough to pay for PrEP, and problems using the pharmaceutical manufacturer’s patient assistance program or co-pay card. The second sub-theme that arose was barriers related to clinic or pharmacy access (n=15, 34.9%), which included long clinic wait times, limited hours, delays in prescription refills, difficulties navigating patient assistance programs, and miscommunication with pharmacy providers or navigators. And third, 32.6% (n=14) reported discontinuing PrEP due to scheduling barriers. Participants described work, school, or travel schedules, as well as competing priorities on their time that made attending clinic during regular business hours difficult.

TABLE 2.

Reasons for PrEP Discontinuation (n = 43)

| Reason Category | Illustrative Quote | |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic issues |

Insurance or financial problems n = 18, 41.9% |

In the meantime, obviously, I can’t take it because my insurance won’t cover it, and it’s very expensive for me. – 33-year-old Hispanic/Latinx gay cisgender man |

| My [pharmaceutical manufacturer] coupon had run out. So that hasn’t been fun. And I would really, really like to get back on PrEP again. – 21-year-old Hispanic/Latinx gay cisgender man | ||

| I haven’t been on [PrEP] for, like, about two months now. I spoke to someone this week…to get my insurance back reinstated…so I can try and get back on it. – 24-year-old Hispanic/Latinx bisexual cisgender man | ||

|

Clinic or Pharmacy problems n = 15, 34.9% |

I always had problems getting the prescription filled. I would show up to the pharmacy to pick it up, and it wouldn’t be ready. – 25-year-old non-Hispanic White gay cisgender man |

|

| The pharmacy that I got the medication prescribed at, they don’t seem to have any directions or know how to utilize the [pharmaceutical manufacturer] coupon. They say that it just doesn’t work. So I haven’t been able to refill or get the prescription from the pharmacy now that it’s been prescribed to me. – 31-year-old non-Hispanic Black gay cisgender man | ||

|

Scheduling barriers n = 14, 32.6% |

I work 12-hour shifts. It rotates days and nights. So when I try to schedule an appointment, there’s a scheduling conflict. – 32-year-old non-Hispanic Multiracial bisexual cisgender man |

|

| Yeah. I have to make an appointment for that, but I have to wait because I kind of used up a lot of personal sick days with my job. – 26-year-old non-Hispanic Multiracial bisexual cisgender man | ||

| Medication Concerns |

Side Effects n = 10, 23.3% |

It was making me very lightheaded and dizzy. And I had to stop taking it because of that matter. – 44-year-old non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander gay cisgender man |

| It was just the first pill that I took. Probably maybe a couple of hours after. I already was apprehensive about taking it. The pill never felt like it was digested, but it felt like it was just stuck in my stomach. Like I could feel it. And I felt nauseous. – 33-year-old Hispanic/Latinx cisgender man; “other” sexual identity | ||

| I stopped taking it because of the risk of other potential side effects, like the buffalo hump, I think, was one, and kidney and liver damage, I think, was another. – 20-year-old Hispanic/Latinx gay cisgender man | ||

|

Contraindications or Interactions n = 4, 9.3% |

The doctor told me – I forgot what the exact two readings were -- but that it’s impacting my liver function. That it’s stressed or being attacked. – 26-year-old non-Hispanic White gay cisgender man |

|

| I was told that…if I use creatine it’s going to affect my health or something like that…So it’s either I continue using the PrEP or I stop the supplements. So I just stopped the PrEP, and I continued my supplements. – 25-year-old Hispanic/Latinx gay cisgender man | ||

|

Medication Beliefs/Associations n = 3, 7.0% |

I just don’t feel strongly that preventative medicine is necessary or that it is beneficial for our bodies to be putting something in my system that would prevent the potential infection of a disease that I didn’t have nor had contracted. – 27-year-old non-Hispanic White queer cisgender man |

|

| [I plan to] take some time off from it, because it’s kind of stressful. Even though it’s only once a day, it made me feel like an old person or a sickly person. So I was like, it’s too much. – 22-year old non-Hispanic Multiracial bisexual cisgender man | ||

| Behavioral Factors |

Low perceived PrEP relevance n = 14, 32.6% |

Yes, I did stop overall taking it. I still have it at home, but, you know, there’s no need for us because we’re not -- you know, we’re mono. We’re just together. We’re not out there exploring. So he doesn’t take it and neither do I, and we’re 100 percent, you know, clean, so we decided not to go ahead and continue taking it. – 36-year-old Hispanic/Latinx bisexual cisgender man |

| I decided that I don’t want to engage in hook-ups anymore, so I don’t have any more apps, I deleted them all, and…I’m not active sexually right now. So there is no point to be taking it every day, so I’m not going to continue. – 39-year-old Hispanic/Latinx bisexual cisgender man | ||

|

Concerns about disinhibition n = 2, 4.7% |

I felt like it would just allow me to engage in unhealthy behavior; I definitely opened up some of those doors for myself. And, you know, we are our own masters and I do believe that, and so I, you know -- I don’t blame PrEP or my use of PrEP for the choices I was making. I just know that for myself, having that crutch of a medication like that was taking me down directions that I didn’t need to be going down. So I ended up stopping it after a month, and then I haven’t been on it since, nor do I have any desire to. – 27-year-old non-Hispanic White queer cisgender man |

|

The second category of reasons for PrEP discontinuation was medication concerns, which were mentioned by 32.6% (n=14) of participants. Again, this category contained three sub-themes. The most common sub-theme within this category was side effects (n=10, 23.3%), including experienced drowsiness and fatigue, nausea and diarrhea, abdominal pain, back pain, headache and migraines, low concentration, anxiety, and depressive symptoms; additionally, participants were concerned about potential long-term side effects. Some participants (n=4, 9.3%) reported discontinuing PrEP because of contraindications (i.e., organ function), drug interactions (i.e., with attention deficit medication or exercise supplements), or seroconversion. And three participants (7.0%) reported medication beliefs or associations that motivated them to stop taking PrEP. This included wanting to avoid medication, and associating the act of pill-taking with feeling old or sick.

The final category of reasons for PrEP discontinuation was behavioral factors, which were mentioned by 34.9% (n=15) of participants. The vast majority of these participants (n=14, 32.6% of all participants who discontinued) reported that they discontinued PrEP because they did not believe PrEP was important or relevant for them, given their current sexual behavior. Participants mentioned changes in relationship status, including becoming monogamous or ending a particular relationship, as well as changing their sexual patterns or decreasing their level of sexual activity. Two participants (4.7%) reported discontinuing PrEP because they were worried they would stop engaging in other risk reduction strategies if they continued taking PrEP.

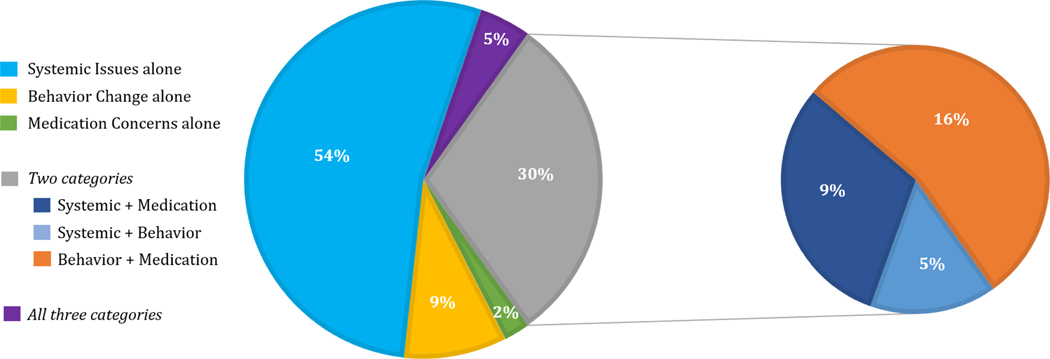

Figure 1 presents the distribution and co-occurrence of the three categories as reasons for PrEP discontinuation. The majority of participants (n=23, 53.5%) cited systemic issues alone as the reason for PrEP discontinuation. An additional 19% (n=8) cited systemic issues in combination with medication concerns (n=4, 9.3%), behavior change (n=2, 4.7%), or both (n=2, 4.7%). When participants spoke about the combination of systemic issues and other factors, medication concerns or behavioral factors were often used to justify why overcoming logistical or financial barriers was not worth the effort.

Figure 1.

Distribution and Co-occurrence of Reasons for PrEP Discontinuation (n = 43)

…so I took the first 30-day bottle that they gave me… then they wanted me to go back for an appointment so that they could make sure my blood work was good and I could continue taking it. But I wasn’t able to make it because of school, so they rescheduled. I went to that one, [but] because I had been off of PrEP for already, like, a month, they wanted me to get blood work done [again]. So I went and did that, and they were, like, supposed to call me after they got my results or, like, contact me, but they never did. So -- I just, like, forgot about it… and then I just decided, like, I wasn’t going to use PrEP because I’m not, like, that sexually active anymore.

-- 20-year-old Hispanic/Latinx gay cisgender man

To obtain a bottle, it just was very difficult because I don’t have good insurance, and this and that. And it’s just been difficult to navigate that. And I’m just very, very busy with things in my life. It wasn’t top priority and I wasn’t really having a lot of sex anyways. So I wasn’t really in need. I didn’t feel like I was at high risk anyway at the time.

-- 36-year-old non-Hispanic White gay cisgender man

As these statements demonstrate, participants found the process of continuing PrEP both challenging and burdensome, and weighed that burden against their perceived risk and need for PrEP. Only four participants (9.3%) cited behavioral factors alone as the reason for their discontinuation, and only one participant cited medication concerns alone. Seven participants (16.3%) cited a combination of behavioral factors and medication concerns.

I just don’t feel that I have enough -- I am not active enough, especially since I was in a relationship. And it just really didn’t make me feel good. I don’t believe in taking something that’s supposed to help you if it makes you feel like you’re sick every day.

-- 37-year-old non-Hispanic Black cisgender man; “other” sexual identity

All participants who discussed behavioral factors in combination with other issues talked about not being sexually active or high-risk “enough” to overcome other barriers to PrEP use. They arrived at this decision either because they perceived their sexual behaviors did not justify overcoming the systemic issues or medication concerns or because these barriers prompted them to reconsider their behaviors and, ultimately, their PrEP use in a different manner than previously.

PrEP Restarts

Of the 44 participants who reported discontinuing PrEP, 13 (29.5%) reported restarting PrEP during the follow-up period [Table 3]. Eight of the participants who restarted PrEP (61.5%) reported restarting because their systemic issues had been resolved. For example, one participant tried to continue PrEP at two referral clinics that did not take his insurance; he ultimately received PrEP through his primary care doctor, who he had avoided asking for fear of feeling judged. Three participants (23.1%) reported re-starting because they experienced a change in their behavior that made them feel “riskier” or in need of PrEP. Two participants (15.4%) declined to provide a reason for restart.

TABLE 3.

Reasons for PrEP Restart (n = 13)*

| Reason Category | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|

|

Change in Systemic Issues n = 8, 61.5% |

“[My PrEP use] was off and on for a while, but then I’m back on…[It was] just, like, anxiety of turning in grad school applications.” – 26-year-old Hispanic/Latinx gay cisgender man |

| “I had to stop -- discontinue PrEP because my health insurance company reset their deductible and wanted me to pay full price. And then I contacted [the clinic] to see if there’s anything they could do for me, and they signed me up for the Gilead program…which paid the difference on what my health insurance company wasn’t paying for. I was able to get back on PrEP.” – 23-year-old Hispanic/Latinx gay cisgender man | |

|

Change in behavioral factors n=3, 23.1% |

“To obtain a bottle, it just was very difficult because I don’t have good insurance, and this and that. And it’s just been difficult to navigate that. And I’m just very, very busy with things in my life. It wasn’t top priority and I wasn’t really having a lot of sex anyways. So I wasn’t really in need. I didn’t feel like I was at high risk anyway at the time. So that’s how I evaluated it. I wasn’t having a lot of intercourse. And I try not to have anal sex or anything, so I felt like I was not at high risk. But lately, I started to date one person. So I thought I would start it again.” – 36-year-old non-Hispanic White gay cisgender man |

| “And then my behavior and stuff started to get a little bit riskier, and I started to feel more nervous. So I went back and made it a point to go on it for it the last three months.” – 20-year-old non-Hispanic White queer cisgender man |

2 participants did not provide reasons for restarting PrEP

DISCUSSION

Patterns of PrEP use in our sample reveal that PrEP continuation is dependent on several interacting factors. Approximately half of participants who initiated PrEP discontinued during the study follow up period, with one-third of discontinuers later restarting. Participant-reported reasons for PrEP discontinuation fell into three categories – systemic issues, medication concerns, and behavioral factors. As with previous studies, systemic issues, such as financial barriers or clinic and pharmacy access issues were paramount and frequently cited. The majority of participants who restarted in the project period did so as a result of resolving the systemic issues that had prompted discontinuation. Similar to reasons for discontinuation, often participants’ motivation for PrEP changed and prompted them to figure out ways to surmount systemic barriers in order to restart PrEP. These findings re-frame the prevailing narrative that patients are not motivated or compliant enough to continue taking PrEP and, instead, draw attention to the incredibly complex hurdles that patients are forced to navigate in order to sustain PrEP use. While the systemic issues that hinder PrEP use have been well documented,7,9–11 this study demonstrates that while some patients can overcome these hurdles, others are forced to reevaluate their need within this challenging access landscape.

Relatedly, this study sheds additional light on the ways in which barriers to PrEP use interact to influence PrEP continuation. While participants commonly reported behavioral factors as a reason for discontinuation, behavior change was rarely cited as the sole reason for stopping PrEP. Instead, sexual behavior was discussed in the context of other concerns and participants evaluated their risk in terms of whether or not it justified the efforts needed to overcome other barriers to PrEP use (e.g., difficulties paying for PrEP). A similar pattern was found with medication concerns: almost all participants who cited medication concerns as a factor in discontinuation did so in conjunction with other factors.

These findings provide an alternative understanding of reports that patients are stopping PrEP because they do not adequately understand their HIV risk. In contrast, our data indicate that patients may be internalizing a focus on epidemiological risk factors that has guided public health messaging and clinical PrEP eligibility tools. Participants seem to be considering whether they are high risk enough to warrant the potential or experienced financial, logistic, physical, and emotional costs of PrEP. One comparable survey study that asked participants via a free text field to explain why they discontinued PrEP use found that most commonly participants cited lower sexual risk.31 Perhaps the format of in-depth interviews in our study allowed participants to provide more nuanced responses and contextualize their risk perception within other barriers to care that they experienced. Increasing PrEP retention means reducing systemic barriers or medication concerns, while simultaneously reframing messages to promote PrEP “relevance” to a broader sexually active population as a protective measure or health promotion tool.35,36 Motivation for continuing PrEP can be increased by engaging patients in discussions of its benefits for them and its relevance to their sexual health, independent of assessment algorithms or eligibility criteria.37

Given the interplay of systemic issues, medication concerns, and behavioral factors, event-driven or episodic PrEP use should be considered as an option for patients.17,18,38 This strategy can prolong access to often limited or high-priced medication supply, limits daily PrEP for those that are experiencing or concerned for side effects, and allows for patients to use PrEP intermittently to align with changes to sexual behaviors and periods of PrEP relevance. Importantly, this strategy had not been embraced by the larger medical community at study recruitment; the SHCs currently offer provider guidance on this method.39

Our study has several limitations. While our sample is relatively large for a qualitative analysis, it is small for drawing quantitative conclusions about the reasons for PrEP discontinuation. Our study was conducted in New York City, primarily among gay and bisexual cisgender men, which may limit generalizability. However, even with New York City’s numerous PrEP providers and financial resources (e.g., the PrEP Patient Assistance Program [PrEP-AP]), systemic issues were the most common reason for discontinuation, suggesting that these could be even greater barriers in other parts of the United States. Second, the SHC PrEP navigation model requires that patients seek ongoing PrEP care at a referral clinic, necessitating linkage to a new site, and may therefore have contributed to discontinuation in a way that another facility that provided co-located PrEP prescriptions and maintenance care would not have. Third, our analysis excluded prior PrEP users or those who were currently using PrEP, who may have had different PrEP use trajectories and reasons for discontinuation and restart than the PrEP-naïve sample we analyzed. Fourth, though we asked open-ended questions about barriers and facilitators to continued PrEP use, interviewers may have had different approaches to probing and it is possible that other important barriers were not mentioned; nonetheless, the open-ended nature of our questioning reduced bias from suggestion and allowed participants to share their decision-making process and reasons for discontinuation in their own words. Finally, the follow-up interviews in our study design included questions about PrEP continuation and reconsideration that may have influenced participants’ patterns of use, such as increasing PrEP restart. Nonetheless, our study’s strengths include that it relies on patient-reported reasons for discontinuation and does not rely on electronic medical record data that are inputted by providers and clinics. Additionally, our reliance on follow-up data collection rather than attendance at a specific clinic allows us to understand the PrEP use pathways of patients who may otherwise be considered lost to follow up.

CONCLUSIONS

To increase patients’ desire and ability to remain engaged in PrEP care, systemic issues – such as financial support for PrEP and ease of appointment scheduling and obtaining a prescription – must be addressed. The health care system can alleviate these barriers by training clinic and pharmacy staff to be conversant in available financial resources, offering expanded clinic hours and/or telemedicine appointments, reducing unnecessary follow-up and lab visits, and offering navigation assistance for overcoming systemic issues. In the wake of COVID-19, many facilities have adapted clinical protocols to facilitate access when in-person visits are not feasible; it is our hope that many of these accommodations, and the payment and coverage policies that enable them, continue beyond the pandemic to increase access to care. Additionally, language from risk assessments has been internalized by patients when describing their PrEP use decisions; a move away from this approach of classifying and stigmatizing individuals may provide patients with space to decide for themselves whether PrEP is right for them, acknowledging that multiple factors, not just risk, influence PrEP use. Furthermore, an approach that emphasizes personal PrEP relevance and contextual factors may be particularly valuable for certain populations who may not perceive themselves to have individual risk, such as cisgender women.

Acknowledgments:

We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of Hunter Alliance for Research & Translation (HART) ream members Gina Bonilla, Ashanay Allen, Chibuzo Enemchukwu, and Christopher Rincon for their assistance in collecting these data. The authors wish to thank and acknowledge our collaborators from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, including: Oni Blackstock, Susan Blank, Sarah Braunstein, Demetre Daskalakis, Anisha Gandhi, Kelly Jamison, Tarek Mikati, and Preeti Pathela for their facilitation of and commitment to this project. We are also grateful to the participants who gave their time and energy to this research. Many thanks to Drs. Susannah Allison and Michael Stirratt.

Sources of support: The study was supported by grant funding from NIH (R01MH106380–02S1; Golub, PI). The funder had no input into the development or content of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Effectiveness of Prevention Strategies to Reduce the Risk of Acquiring or Transmitting HIV. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/estimates/preventionstrategies.html. Published 2019. Accessed June 10, 2020.

- 2.Nunn AS, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Oldenburg CE, et al. Defining the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care continuum. AIDS. 2017;31(5):731–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang YA, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N, Hoover KW. HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis, by Race and Ethnicity - United States, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(41):1147–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan PS, Giler RM, Mouhanna F, et al. Trends in the use of oral emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection, United States, 2012–2017. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):833–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanny D, Jeffries WLt, Chapin-Bardales J, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex with Men - 23 Urban Areas, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(37):801–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, et al. The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis-to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serota DP, Rosenberg ES, Thorne AL, Sullivan PS, Kelley CF. Lack of health insurance is associated with delays in PrEP initiation among young black men who have sex with men in Atlanta, US: a longitudinal cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(10):e25399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spinelli MA, Scott HM, Vittinghoff E, et al. Missed Visits Associated With Future Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Discontinuation Among PrEP Users in a Municipal Primary Care Health Network. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(4):ofz101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Angelo AB, Lopez-Rios J, Flynn AWP, Holloway IW, Pantalone DW, Grov C. Insurance- and medical provider-related barriers and facilitators to staying on PrEP: results from a qualitative study. Transl Behav Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Laborde ND, Kinley PM, Spinelli M, et al. Understanding PrEP Persistence: Provider and Patient Perspectives. AIDS Behav. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Hojilla JC, Vlahov D, Crouch PC, Dawson-Rose C, Freeborn K, Carrico A. HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Uptake and Retention Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in a Community-Based Sexual Health Clinic. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1096–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitfield THF, Parsons JT, Rendina HJ. Rates of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Use and Discontinuation Among a Large U.S. National Sample of Sexual Minority Men and Adolescents. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(1):103–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serota DP, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and discontinuation among young black men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia: A prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Chan PA, Patel RR, Mena L, et al. Long-term retention in pre-exposure prophylaxis care among men who have sex with men and transgender women in the United States. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(8):e25385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan PA, Mena L, Patel R, et al. Retention in care outcomes for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation programmes among men who have sex with men in three US cities. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shover CL, Shoptaw S, Javanbakht M, et al. Mind the gaps: prescription coverage and HIV incidence among patients receiving pre-exposure prophylaxis from a large federally qualified health center in Los Angeles, California. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(10):2730–2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haberer JE. Current concepts for PrEP adherence in the PrEP revolution: from clinical trials to routine practice. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(1):10–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman PA, Guta A, Lacombe-Duncan A, Tepjan S. Clinical exigencies, psychosocial realities: negotiating HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis beyond the cascade among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Canada. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(11):e25211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Namey E, Agot K, Ahmed K, et al. When and why women might suspend PrEP use according to perceived seasons of risk: implications for PrEP-specific risk-reduction counselling. Cult Health Sex. 2016;18(9):1081–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reyniers T, Nostlinger C, Laga M, et al. Choosing Between Daily and Event-Driven Pre-exposure Prophylaxis: Results of a Belgian PrEP Demonstration Project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;79(2):186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaccher SJ, Gianacas C, Templeton DJ, et al. Baseline Preferences for Daily, Event-Driven, or Periodic HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Gay and Bisexual Men in the PRELUDE Demonstration Project. Frontiers in Public Health. 2017;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Hoornenborg E, Achterbergh RC, Van Der Loeff MFS, et al. Men who have sex with men more often chose daily than event-driven use of pre-exposure prophylaxis: baseline analysis of a demonstration study in Amsterdam. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2018;21(3):e25105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hevey MA, Walsh JL, Petroll AE. PrEP Continuation, HIV and STI Testing Rates, and Delivery of Preventive Care in a Clinic-Based Cohort. AIDS Educ Prev. 2018;30(5):393–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Epps P, Maier M, Lund B, et al. Medication Adherence in a Nationwide Cohort of Veterans Initiating Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to Prevent HIV Infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(3):272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shover CL JM, Shoptaw S, Bolan R, Gorbach P,. High Discontinuation of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis within Six Months of Initiation. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2018; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgan E, Ryan DT, Morgan K, D’Aquila R, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Trends in PrEP Uptake, Adherence, and Discontinuation among MSM in Chicago. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2018; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Hare CB, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in a Large Integrated Health Care System: Adherence, Renal Safety, and Discontinuation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):540–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serota DP, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, et al. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Uptake and Discontinuation Among Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men in Atlanta, Georgia: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(3):574–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shover CL, Shoptaw S, Javanbakht M, et al. Mind the gaps: prescription coverage and HIV incidence among patients receiving pre-exposure prophylaxis from a large federally qualified health center in Los Angeles, California. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(10):2730–2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holloway IW, Dougherty R, Gildner J, et al. Brief Report: PrEP Uptake, Adherence, and Discontinuation Among California YMSM Using Geosocial Networking Applications. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(1):15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitfield THF, John SA, Rendina HJ, Grov C, Parsons JT. Why I Quit Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)? A Mixed-Method Study Exploring Reasons for PrEP Discontinuation and Potential Re-initiation Among Gay and Bisexual Men. AIDS Behav. 2018. Nov;22(11):3566–3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang YA, Tao G, Smith DK, Hoover KW. Persistence with HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis in the United States, 2012–2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Pathela P, Jamison K, Blank S, Daskalakis D, Hedberg T, Borges C. The HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Cascade at NYC Sexual Health Clinics: Navigation Is the Key to Uptake. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;83(4):357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golub SA, Unger ZD, Allen AS, Enemchukwu CU, Borges CM, Pathela P, Hedberg T, Gandhi A, Edelstein ZR, Myers J. Optimizing PrEP Cascade Outcomes for Sexual Health Clinic Navigation. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2020; Boston, Massachusetts. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golub SA. PrEP Stigma: Implicit and Explicit Drivers of Disparity. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15(2):190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calabrese SK, Tekeste M, Mayer KH, et al. Considering Stigma in the Provision of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: Reflections from Current Prescribers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33(2):79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golub SA, Myers JE. Next-Wave HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Implementation for Gay and Bisexual Men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33(6):253–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molina JM, Charreau I, Spire B, et al. Efficacy, safety, and effect on sexual behaviour of on-demand pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in men who have sex with men: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(9):e402–e410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygeine. “On-Demand” Dosing for PrEP: Guidance for Medical Providers. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/ah/prep-on-demand-dosing-guidance.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed January 15, 2021.