Abstract

Objectives

To synthesize knowledge describing the impact of social distancing measures (SDM) during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on acute illness in children by focusing on the admission to pediatric emergency departments (PED) and pediatric intensive care units (PICU).

Methods

We searched Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, EPOC Register, MEDLINE, Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews, EMBASE, WHO database on COVID-19, Cochrane Resources on COVID-19, Oxford COVID-19 Evidence Service, Google Scholar for literature on COVID-19 including pre-print engines such as medRxiv, bioRxiv, Litcovid and SSRN for unpublished studies on COVID-19 in December 2020. We did not apply study design filtering. The primary outcomes of interest were the global incidence of admission to PICU and PED, disease etiologies, and elective/emergency surgeries, compared to the historical cohort in each studied region, country, or hospital.

Results

We identified 6,660 records and eighty-seven articles met our inclusion criteria. All the studies were with before and after study design compared with the historical data, with an overall high risk of bias. The median daily PED admissions decreased to 65% in 39 included studies and a 54% reduction in PICU admission in eight studies. A significant decline was reported in acute respiratory illness and LRTI in five studies with a median decrease of 63%. We did not find a consistent trend in the incidence of poisoning, but there was an increasing trend in burns, DKA, and a downward trend in trauma and unplanned surgeries.

Conclusions

SDMs in the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the global incidence of pediatric acute illnesses. However, some disease groups, such as burns and DKA, showed a tendency to increase and its severity of illness at hospital presentation. Continual effort and research into the subject should be essential for us to better understand the effects of this new phenomenon of SDMs to protect the well-being of children.

Systematic Review Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov, identifier: CRD42020221215.

Keywords: social distancing measures, school closure, lockdown, pediatrics, emergency care, pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), SARS-CoV-2, pandemic (COVID-19)

Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-Cov-2) and its pandemic have severely affected the healthcare system worldwide as well as our social lives. Studies have demonstrated that children with COVID-19 are responding differently from the elderly population with less severity of illness requiring less emergency and critical care resources (1–4). Preventing transmission particularly to the elderly population and slowing the rate of infections in the community to maintain the healthcare system resulted mainly in social distancing measures (SDMs) including school closures (SCs), which came from the experience of the influenza epidemic and other previous pandemics, particularly during the first wave of this pandemic (5–7). Hospitals have also taken specific measures to decrease their activity in the prevision of an increase in COVID-19 admissions and workforce shortage (8). Both SDMs and hospital measures have come with many trade-offs that have impacted acute illness of children requiring Pediatric Emergency Department (PED) or Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) admission. After the first wave, various countries and regions have reported their results and insights into the consequences of their respective SDMs. This review aims to synthesize knowledge describing the impact of the SDMs together with other various measures of the first wave of the pandemic, defined in each country by the pandemic outbreak until the specific peak and secondary decline, on acute illness requiring hospital admission in children by focusing on PED and PICU admissions as well as on the main type of acute illness or injury in children.

Methods

In this review, we followed the methodology for data collection and analysis in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (9). The study protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (registration number: CRD42020221215).

Eligibility Criteria

Participants

We included pediatric patients including neonates, infants and children/adolescents regardless of gender, countries, regions, and ethnic groups.

Intervention

The impacts of the “pandemic” itself, and other medical and social measures such as social distancing measures (e.g., school closure or mandatory mask-wearing) and hospital-based clinical measures such as postponing planned surgery or restricting the planned surgery related to the COVID-19 pandemic first wave in 2020.

Comparators

The historical cohort in each studied region, country, or hospital.

Outcomes

The global incidence of admission to PED and PICU.

Incidence of PED admission of children with i) acute respiratory illness including respiratory illness, bronchiolitis and asthma, ii) viral infections, iii) injuries including trauma, burns and poisoning, iii) diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), and iiii) unplanned surgery.

Incidence of elective/emergency surgeries like neurosurgery and cardiac surgery.

These categories of illness were chosen according to the usual epidemiology of children admitted to PED and to PICU and included diseases that had consensual definitions.

Search Sources

Studies were identified from journal literature and conference proceedings via systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register and the EPOC Register), MEDLINE, Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews (OVID) and Embase. On top of those databases, WHO database on COVID-19, Cochrane Resources on COVID-19, Oxford COVID-19 Evidence Service, Google Scholar for literature on COVID-19 including pre-print engines such as medRxiv, bioRxiv, Litcovid and SSRN for unpublished studies on COVID-19 were searched. Electronic databases were explored for all studies published articles before December 8, 2020, using the search terms addressed in Appendix 1.

Study Selection

To be included in the review, studies needed to compare the number of admissions for the main selected diseases within two time periods: during the COVID-19 pandemic first wave period of SDM, as compared to the previous year(s), or to the period just before. Only articles in the English language were included.

Following the removal of duplicate studies, two authors (AK and ML) independently assessed the eligibility of the studies using Rayyan (https://rayyan.qcri.org/welcome). Studies were selected as being potentially relevant by screening the titles and abstracts. A third reviewer (VL) assessed all the titles and abstracts that remained in disagreement between the two investigators. We obtained the full text of the article for review when a decision cannot be made by screening the title and the abstract. The two review authors retrieved the full texts of all potentially relevant articles and independently assessed their eligibility by filling out eligibility forms designed by the specified inclusion criteria.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data from the eligible studies were extracted by two investigators using a prespecified data extraction form to record demographic data (including age, country/region), study details (aims/study question, country of origin, methods/study designs), and study outcomes.

Study quality and risk of bias was undertaken according to the Johanna Briggs Institute appraisal tool for analytical cross-sectionals studies (10). However, we did not include the assessment results of the study quality and risk of bias for each included study because all the corresponding studies were with before and after the design of the study with historical cohorts, indicating a high risk of bias without exceptions.

Data Syntheses and Analyses

Data regarding incidence in all the included studies were expressed in mean daily admissions during each study period (Period of social distancing measures = SDM period versus control period). The comparison was made using the percentage of change between the SDM period and the control periods. Median differences and interquartile ranges [IQR] were calculated for each outcome. For all the variables expressed in absolute numbers and percentages (i.e., hospital admission following PED attendance, very urgent triage codes (including patients that either required immediate resuscitation or had life-threatening conditions that required prompt evaluation by the emergency team) and PICU admissions), effects of the study period on these outcomes were reported using odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) estimates.

Results

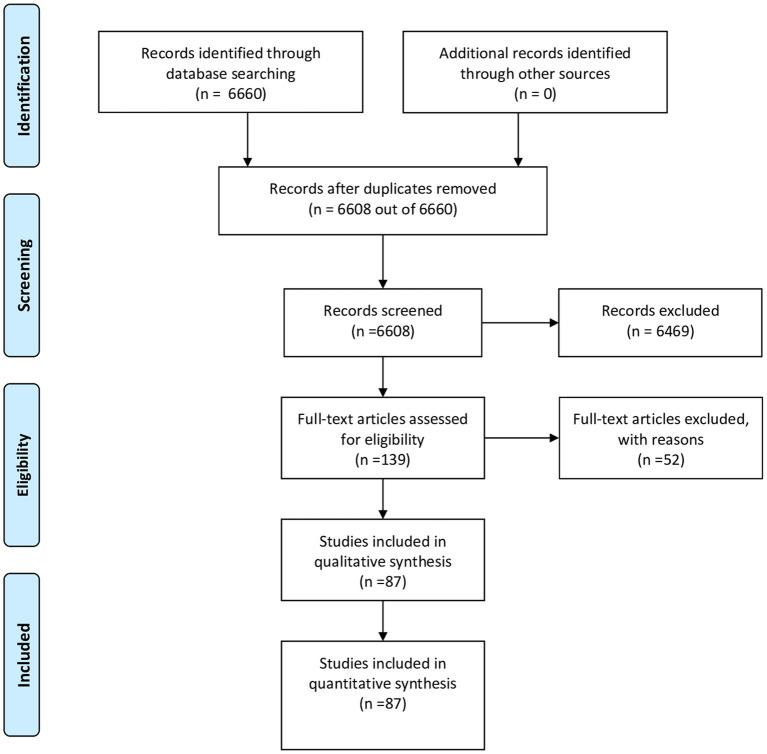

We identified 6,660 records through a systematic database search (Figure 1). We removed 52 duplicates, and the titles and abstracts of the remaining 6,608 records were screened for eligibility. We identified 139 potentially eligible articles for the full-text review. After independent assessment by the two investigators, 87 articles met our inclusion criteria and presented actionable data. All the studies were included in this review and were with before and after design with historical cohorts as expected, indicating a high risk of bias without exceptions.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram.

Countries and Regions

Of the 87 included studies (Table 1), three were international studies. Reports from 26 different countries were identified. To be specific, 15 (17%) were, respectively from the USA and Italy, 13 (15%) from the UK, 4 (5%) from Australia, 3 (3%), respectively from China, France, Ireland, and Spain, 2 (2%), respectively from Brazil, Finland, Germany, India, Japan, New-Zealand, and Turkey. The remaining studies were from Argentina, Cameroon, Canada, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Malta, Morocco, Scotland, Slovenia, and South Africa (n = 1 in each country).

Table 1.

Included studies.

| References | Countries (level of income)* | Multicenter study | Number of patients included | Age of cohort | Settings | Type of admission | Method used | SDM period | Comparison period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akuaake et al. (11) | South Africa (MIC) | No | 9,982 | Children <13 yrs. | ED | ED | Before-after | March 27 to April 30, 2020 | February 21 to March 26, 2020 |

| March 27 to April 30, 2019 | |||||||||

| March 27 to April 30, 2018 | |||||||||

| Angoulvant et al. (12) | France (HIC) | Yes | 871,543 | Children | ED n = 6 | ED | Time-series analysis | March 17 to April 19, 2020 | February 15 to March 16, 2020 |

| Araujo et al. (13) | Brazil (MIC) | Yes | 8,654 | Children | PICU n = 15 | PICU, bronchiolitis, asthma | Interrupted time-series method | March 1 to May 31, 2020 March 1 to May 31, 2020 |

March 1 to May 31, 2017-19 |

| Bastemur E | UK (HIC) | No | 136 | Children | transportation team | DKA | Before after | March 1 to July 31, 2020 | March 1 to July 31, 2015-19 |

| Baxter et al. (14) | UK (HIC) | No | 329 | Children | ED | Trauma | Before after | March 24 to May 10, 2020 | March 24, 2020, to May 10, 2019 |

| Bram et al. (15) | USA (HIC) | No | 1,745 | Children | ED + Clinic + virtual | Trauma | Before after | March 15 to April 15, 2020 | March 15 to April 15, 2018-19 |

| Bressan et al. (16) | Italy (HIC) | No | 3,713 | Children > 1 yr. | ED | Trauma, Burn, Poisoning | Before after | March 8 to April 20, 2020 | March 8 to April 20, 2019 |

| Britton et al. (17) | Australia (HIC) | No | NA | Children | ED | Bronchiolitis, RSV | Time-series analysis | April 1 to June 30, 2020 | Jan 1, 2015, to March 30, 2020 |

| Chavasse et al. (17) | UK (HIC) | No | NA | Children 1–17 yrs. | ED | Asthma | Before after | Week 12 to 19, 2020 | Week 12 to 19 2017-19 |

| Week 8 to 11, 2020 | |||||||||

| Chelo et al. (18) | Cameroon (MIC) | No | 33,363 | Children | HA | ED | Time-series analysis | March 1 to May 31, 2020 | March 1 to May 31, 2016–19 |

| Christey et al. (19) | New Zealand (HIC) | No | 83 | Children <14 yrs. + adults | ED | Trauma | Before after | March 26 to April 8, 2020 | March 5 to March 18, 2020 |

| Ciofi degli Atti et al. (20) | Italy (HIC) | No | 18,825 | Children | ED | ED, Trauma | Before after | March 11 to April 20, 2020 | January 1 to February 19, 2020 |

| February 20 to March 10, 2020 | |||||||||

| Claudet e tal. (21) | France (HIC) | No | 3,137 | Children | ED | ED, Trauma | Before after | March 17 to April 19, 2020 | March 17 to April 19, 2017-19 |

| Clavenna et al. (22) | Italy (HIC) | No | 7,092 | Children | ED | ED | Before after | January 1 to March 31, 2020 Feb 23 to March 31, 2020 | January 1 to March 31, 2019 January to Feb 23, 2020 |

| February 24 to March 31, 2020 | January 1 to Feb 23, 2020 | ||||||||

| D'asta F | UK (HIC) | No | 10,063 | Children | ED | ED, Burn | Before after | March 23 to April 30, 2020 | March 23 to April 30, 2019 |

| Dann et al. (23) | Ireland (HIC) | No | 21,766 | Children | ED | ED, injury and poisoning, surgical, respiratory illnesses | Before after | March 1 to April 30, 2020 | March 1 to April 30, 2019 |

| Davico et al. | Italy (HIC) | Yes | 15,523 | Children <14 | ED n = 2 | ED, seizures | Before after | January 6 to April 19, 2020 | January 7 to April 21, 2019 |

| (24) | yrs. | January 6 to February 23, 2020 | January 7 to February 24, 2019 | ||||||

| February 24 to April 19, 2020 | February 25 to April 21 2019 | ||||||||

| Dean et al. (25) | USA (HIC) | No | 210,358 | Children | ED | ED | Time series analysis | December 31, 2019, to May 14, 2020 | December 31, to May 14, 2015-19 |

| Degiorgio et al. (26) | Malta (HIC) | No | 995 | Children <15 yrs. | ED | Medical ED, respiratory illnesses | Before after | March 1 to May 9, 2020 | March 1 to May 9, 2019 |

| Dhillon et al. (27) | India (MIC) | No | 74 | Children 0-12 yrs. | ED | Trauma | Before after | March 25 to May 3, 2020 | March 25 to May 3, 2019 |

| May 4 to May 31, 2020 | May 4 to May 31, 2019 | ||||||||

| Dopfer et al. (28) | Germany (HIC) | No | 5,424 | Children | ED | ED | Before after | January 1 to April 19, 2020 | January 1 to April 19, 2019 |

| Dyson et al. (29) | UK (HIC) | No | 146 | Children | Neurosurgery admission | Neurosurgery admission | Before after | March 23 to May 3, 2020 | March 25 to May 5, 2019 |

| Ferrero et al. (30) | Argentina (MIC) | No | Children 0–18 yrs. | ED | ED | Before after | January 1 to May 31, 2020 | January 1 to May 31, 2019 | |

| Fisher et al. (31) | USA (HIC) | Yes | 1,346 | Children | ED n=3 | Appendicitis | Before after | March 1 to May 7, 2020 | January 1, 2014, to June 1, 2019 |

| Friedrich et al. (32) | Brazil (MIC) | Yes | 167,870 | Children 0–1 yr. | ED / National database n = NA | Bronchiolitis | Times series analysis | March 1 to June 30, 2020 | March 1 to June 30, 2016-2019 |

| Gerall et al. (33) | USA (HIC) | No | 89 | Children | Surgery | Appendicitis | Before after | March 1 to May 31, 2020 | March 1, 2019, to May 31, 2019 |

| Giamberti et al. (34) | Italy (HIC) | Yes | Children | Cardiac surgery n = 14 | Cardiac surgery | Before after | March 9 to May 4, 2020 | March 9 to May 4, 2019 | |

| Goldman et al. (35) | Canada (HIC) | Yes | 88,368 | Children 0–16 yrs. | ED n = 18 | ED | Before after | March 17 to April 30, 2020 | March 17 to April 30, 2019 |

| December 1, 2019, to January 27, 2020 | |||||||||

| January 28, 2020, to March 16, 2020 | |||||||||

| Graciano et al. (24) | USA (HIC) | No | 1,487 | Children | PICU | PICU, bronchiolitis, asthma | Before after | March 1 to May 31, 2020 | March 1 to May 31, 2015-2019 |

| Gunadi et al. (36) | Indonesia (MIC) | No | 152 | Children | Surgery | Pediatric surgery | Before after | March 1 to May 31 2020 | March 1, 2019 – February 29, 2020 |

| Hampton et al. (37) | UK (HIC) | No | 5,165 | Children + adults | ED | ED, trauma | Before after | March 24 to April 7, 2020 | March 24 to April 7, 2019 March 10 to March 23, 2020 |

| Hartnett et al. (38) | USA (HIC) | Yes | >1,600,000 | Children 0–14 yrs. + adults | ED n = 3552 | ED | Before after | March 29 to April 25, 2020 | March 31 to April 27, 2019 |

| Hughes et al. (39) | UK (HIC) | Yes | 8,915 | Children 0-14 yrs. + adults | ED n = 109 | ED | Before after | March 12 to April 26, 2020 | March 14 to April 28, 2019 |

| Iozzi et al. (40) | Italy (HIC) | No | 2,956 | Children | ED | ED, trauma | Before after | March 10 to May 3, 2020 | March 10 to May 3, 2019 |

| Izba et al. (24) | UK/USA (HIC) | Yes | NA | Children 0–16 yrs. | ED n = 2 | ED | Before after | January 1 to May 20, 2020 | January 1 to May, 2019 |

| Weeks 1–12, 2020 | Weeks 1–12, 2019 | ||||||||

| Weeks 13–20, 2020 | Weeks 13–20, 2019 | ||||||||

| Kamrath et al. (31) | Germany (HIC) | Yes | 1,491 | Children | ED n = 217 | DKA | Before after | March 13 to May 13, 2020 | March 13 to May 13, 2018–19 |

| Rose et al. (41) | UK (HIC) | No | 4,690 | Children 0–16 yrs. | ED | ED, head trauma | Before after | March 21 to April 26, 2020 | March 21 to April 26, 2019 |

| Kishimoto et al. (14) | Japan (HIC) | Yes | 75,053 | Children 0-15 yrs. | HA n = 210 | Appendicitis, influenza | Interrupted time series analysis | March 1 to June 30, 2020 | July 1, 2018, to February 29, 2020 |

| Korun et al. (42) | Turkey (MIC) | No | 696 | Children | Cardiac surgery | Cardiac surgery | Before after | March 11 to May 11, 2020 | March 11, 2019, to March 10, 2020 |

| Krivec et al. (43) | Slovenia (HIC) | No | 27 | Children | HA | Asthma | Before after | March 16 to April 20, 2020 | March 16 to April 20, 2017–19 |

| Kruchevsky et al. (44) | Israel (HIC) | No | 8,291 | Children + adults | ED | ED, Burn, Trauma | Before after | March 14 to April 20, 2020 | March 14 to April 20, 2017–19 |

| Kuitunen et al. (24) | Finland (HIC) | Yes | 1,174 | Children | ED n=2 | ED | Before after | March 16 to April 12, 2020 | February 17 to March 15, 2020 |

| Kvasnovsky et al. (45) | USA (HIC) | No | 205 | Children | Surgery | Appendicitis | Before after | March 31 to May 3, 2020 | March 31 to May 3, 2017–2019 |

| Lalarukh et al. (46) | UK (HIC) | No | NA | Children <18 yrs. | ED | ED | Before after | March 1 to May 31, 2020 | March 1 to May 31, 2019 |

| Lawrence et al. (47) | Australia (HIC) | No | 43 | Children <18 yrs. | ED | ED, DKA | Before after | March 1 to May 31, 2020 | March 1 to May 31, 2015-19 |

| Lee et al. (48) | USA/Singapore/ Australia/France (HIC) |

Yes | NA | Children | ED n = 5 | ED, PICU | Time series analysis | December 1, 2017, to August 10, 2020 | |

| Lee-Archer et al. (49) | Australia (HIC) | No | 105 | Children | Surgery | Appendicitis | Before after | March 16 to May 5, 2020 | March 16 to May 5, 2019 |

| Lv et al. (24) | China (MIC) | Yes | 194 | Children + adults | ED n = 11 | Fractures | Before after | January 20, to February 19, 2020 | January 31 to March 2, 2019 |

| Mann et al. (50) | UK (HIC) | No | 147 | Children | ED | Burns | Before after | March 23 to May 31, 2020 | March 23 to May 31, 2019 |

| Manzoni et al. (48) | Italy (HIC) | Yes | 1,654 | Children | ED n = 2 | ED, Trauma, Urgent surgery | Before after | March 1 to April 30, 2020 | March 1 to April 30, 2019 |

| Matthay et al. (51) | USA (HIC) | No | 20,129 C+A | Children <15 yrs. + adults | ED | Trauma | Interrupted time-series analysis | March 17 to June 30, 2020 | January 1, 2015, to March 17, 2020 |

| McDonnell et al. (52) | Ireland (HIC) | Yes | 61,317 | Children | ED n = 5 | ED | Before after | February 29 to March 12, 2020 | February 29 to March 12, 2018–19 |

| March 13 to March 27, 2020 | March 13 to March 27, 2018–19 | ||||||||

| March 28 to May 17, 2020 | March 28 to May 17, 2018–19 | ||||||||

| Mekaoui et al. (53) | Morocco (MIC) | No | 5,342 | Children <16 yrs. | ED | ED | Before after | March 16 to April 15, 2020 | March 16 to April 15, 2019 |

| Memeo et al. (54) | Italy (HIC) | Yes | 1,380 | Children 0-17 yrs. | Trauma ED n = 2 | Trauma | Before after | February 23 to April 15, 2020 | February 23 to April 15, 2019 |

| Molina Gutiérrez et al. (55) | Spain (HIC) | No | 6,493 | Children <18 yrs. | ED | ED, trauma, poisoning | Before after | March 14 to April 17, 2020 | March 14 to April 17, 2019 |

| Montalva et al. (49) | France (HIC) | No | 108 | Children | Surgery | Appendicitis | Before after | January 20 to March 16, 2020 | March 17 to May 11, 2020 |

| Nabian et al. (56) | Iran (MIC) | No | 877 | Children <18 yrs. | Trauma ED | Trauma | Before after | March 1 to April 15, 2020 | March 1 to April 15, 2018-19 |

| Nelson et al. (57) | USA (HIC) | No | 94 | Children | Surgery | Testicular torsion | Before after | March 1 to May 31, 2020 | January 1, 2018, to February 29, 2020 |

| Nolen et al. (58) | USA (HIC) | No | NA | Children <3 yrs. | ED | RSV, ARI | Time series analysis | January 1 to May 31, 2020 | January 1 to May 31, 2009-19 |

| Nourazari et al. (59) | USA (HIC) | Yes | 501,369 | Children + adults | ED n = 12 | ED | Before after | January 1 to August 9, 2020 | January 1 to September 9, 2019 |

| Okonkwo et al. (60) | UK (HIC) | No | 3,826 | Children | Surgery | emergency surgery | Before after | March 23 to May 25, 2020 | March 23 to May 25, 2019 |

| Palladino et al. (61) | Italy (HIC) | No | 57 | Children 4–14 years | ED | ED, seizures | Before after | March 9 to May 4, 2020 | March 9 to May 4, 2019 |

| Park et al. (62) | UK (HIC) | No | 39 | Children + adults | ED | Trauma | Before after | March 17 to April 15, 2020 | March 17 to April 15, 2019 |

| Peiro-Garcia et al. (63) | Spain (HIC) | No | NA | Children | Orthopedic surgery | Orthopedic surgery & Trauma | Before after | March 14 to April 14, 2020 | March 14 to April 14, 2018–19 |

| Pines et al. (64) | USA (HIC) | Yes | 383,033 | Children + adults | ED n = 144 | ED, asthma, influenzae, viral infection, DKA, Appendicitis, Intussepstion, testicular torsion | Before after | March 13 to June 30, 2020 | March 13 to June 30, 2019 |

| Place (65) | USA (HIC) | No | 160 | Children <18 yrs. | ED | Appendicitis | Before after | March 16 to June 7, 2020 | March 16 to June 7, 2019 |

| Qasim et al. (66) | USA (HIC) | Yes | 336 | Children + adults | ED n = 2 | Trauma | Before after | March 9 to April 19, 2020 | March 9 to April 19, 2019 |

| Raitio et al. (67) | Finland (HIC) | Yes | 1,755 | Children | Surgery n = 5 | Trauma | Before after | March 1 to May 31, 2020 | March 1 to May 31, 2017–19 |

| Raman et al. (68) | India (MIC) | No | 1,070 | Children | ED | ED, PICU | Before after | April 1 to July 31, 2020 | April 1 to July 31, 2019 |

| Pediatric Surgery Trainee Research Network | UK (HIC) | Yes | 87 | Children | Surgery n = 10 | Pyloric stenosis | Before after | March 23 to May 31, 2020 | March 23 to May 31, 2019 |

| Scaramuzza A | Italy (HIC) | Yes | 3,912 | Children <15 yrs. | ED n = 2 | ED | Before after | February 20 to March 30, 2020 | February 20 to March 30, 2019 |

| Bun et al. (43) | Japan (HIC) | Yes | 10,481 | Children <15 yrs. | ED n = 67 | Asthma | Interrupted time-series analysis | July 1, 2019, to June 30, 2020 | July 1, 2018, to June 30, 2019 |

| Sheridan et al. (69) | Ireland (HIC) | No | 423 | Children | ED | Trauma | Before after | March 13 to April 13, 2020 | March 13 to April 13, 2009–19 |

| Sherman et al. (70) | USA (HIC) | No | 224 | Children + adults | ED | Trauma | Before after | March 20 to May 14, 2020 | March 20 to May 14, 2017–19 |

| Shi et al. (42) | China (MIC) | Yes | 4,877 | Children | Cardiac surgery n = 13 | Cardiac surgery | Before after | January 23 to April 8, 2020 | January 23 to April 8, 2018–19 |

| Smarrazzo A | Italy (HIC) | No | Children | ED | ED | Before after | March 1 to May 31, 2020 | March 1 to May 31, 2019 | |

| Sperotto et al. (71) | Italy (HIC) | Yes | 1,001 | Children | PICU n = 4 | PICU, Seizures, Surgical, Trauma, Respiratory lower tract | Before after | February 24 to April 20, 2020 | December 30, 2019, to February 24, 2020 |

| February 24 to April 20, 2019 | |||||||||

| Williams et al. (72) | Scotland (HIC) | Yes | ED 462,437 | Children 0–14 yrs. | ED n=NA, PICU n = 2 | ED, PICU, Surgical ED, Bronchiolitis, Asthma, Seizures | Before after | March 23 to August 9, 2020 | March 23 to August 9, 2016–19 |

| PICU 413 | February 2 to August 9, 2020 | February 2 to August 9, 2016–19 | |||||||

| March 23 to June 30, 2020 | March 23 to June 30, 2016–19 | ||||||||

| Trenholme et al. (17) | New Zealand (HIC) | No | 5,248 | Children <2 yrs. | Hospital | LRTI, RSV, Influenza A, B, Rhinovirus/enterovirus, adenovirus | Interrupted time-series analysis | March 1 to August 31, 2020 | March 1 to August 31, 2015–019 |

| Turgut et al. (73) | Turkey (MIC) | No | 2,216 | Children <16 yrs. | Hospital | Orthopedic surgery & Trauma | Before-after | March 16 to May 22, 2020 | March 16 to May 22, 2018 & 2019 |

| Valitutti et al. (74) | Italy (HIC) | Yes | 38,501 | Children | ED n = 2 | ED, trauma, burn, seizure | Before-after | March 1 to May 31, 2020 | March 1 to May 31, 2019 |

| Vásquez-Hoyos (58) | Colombia, Bolivia, Chile, Uruguay (MIC) | Yes | 3,041 | Children <18 yrs. | PICU | PICU, LRTI, bronchiolitis, RSV, influenza | Before-after | January 1 to August 31, 2020 | January 1 to August 31, 2018-19 |

| Velayos et al. (75) | Spain (HIC) | No | 66 | Children <18 yrs. | Surgery | Appendicitis | Before-after | January 1 to March 14, 2020 | March 15 to April 30, 2020 |

| Vierucci et al. (76) | Italy (HIC) | No | 1,418 | Children | ED | ED, LRTI, Trauma, Febrile Seizure, Appendicitis | Before-after | March 9 to May 31, 2020 | January 1 to March 8, 2020 |

| March 1 to May 31, 2020 | January 1 to February 29, 2019 | ||||||||

| Wei et al. (3) | China (MIC) | No | 4,527 | Children | Surgery | Urgent surgery | Before after | January 23 to May 21, 2020 | January 23 to May 21, 2019 |

| Wong et al. (67) | Australia (HIC) | No | 621 | Children | Orthopedics ED | Trauma | Before after | March 16 to April 26, 2020 | March 18 to April 28, 2019 |

| Zampieri et al. (77) | Italy (HIC) | No | 95 | Children | Surgery | Appendicitis | Before-after | March 1 to April 30, 2020 | March 1 to April 30, 2011-19 |

*LIC, low-income country; MIC, middle-income country; HIC, High-income country.

Study Settings and Data Sources

Among all the included studies, 59 were studies performed in PEDs, five in PICUs, 17 used institutional surgical databases (including three studies on congenital heart disease and one on neurosurgery), and three used a hospital-based administrative database.

Impact on Pediatric Emergency and Intensive Care Unit Admission

Admissions to Pediatric Emergency Department

We included 39 studies from 19 countries including 15 multicenter studies (11, 12, 16, 18, 20–26, 28, 30, 35, 37–41, 44, 46–48, 52, 53, 55, 59, 61, 64, 65, 68, 72, 74, 76, 78–82) (Supplementary Table 1). All the included studies found a decrease in daily PED admissions during the SDM period with a median reduction of 65% [IQR: 52–72%] compared to historical cohorts. When focusing on studies including the largest number of patients (i.e., more than 200 mean daily admissions in the control period) (12, 20, 24, 35, 64, 65, 74), the reduction in PED attendance ranged from 38 to 77%.

Of these studies, 15 presented data on hospital admission following PED attendance (22, 23, 28, 35, 41, 52, 53, 55, 65, 68, 72, 74, 76, 79, 80) (Supplementary Table 2). Overall, during the SDM period, we observed a significant increase in the proportion of patients admitted to the hospital after PED visits with median ORs ranging from 1.12 to 3.51 (n = 13/15).

Ten studies looked at the proportions of very-urgent triage code on the presentation at PEDs (11, 22, 23, 25, 35, 41, 53, 59, 72, 74) but results were not consistent (Supplementary Table 3). In particular, compared with the same period in previous years, four studies found a significant increase in the proportion of very-urgent triage code (35, 41, 59, 74) whereas others found no difference (11, 22, 23, 53, 72) or even a decrease (25). However, when comparing to the period just before the SDM period, three studies found a significant increase in these urgent PED admissions (11, 22, 35).

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Admissions

We included eight studies with data regarding PICU admission (13, 26, 48, 58, 71, 81–83) with two international studies and six studies, respectively from Brazil, India, Italy, Malta, Scotland, and the USA including data from a total of 51 PICUs. All the studies found a reduction in daily PICU attendances with a median reduction of 54% [IQR: 48–65%] compared with controlled periods (Table 2). Two large multicenter studies from South America including 15 and 22 PICUs found, respectively a decrease of 53% of all the PICU admissions (13) and 83% of respiratory PICU admissions (58). Only one out of all the 51 study sites included in these studies from France found an increase of 2% in the mean number of daily admissions (48). Of note, one study from India found an overall decrease of PICU admissions of 26% in the SDM period but a significantly higher proportion of patients admitted to PICU after PED attendance (20%) compared with the control period (9, 6%) (OR: 2.35, 95%CI: 1.61–3.42) (81).

Table 2.

PICU Admissions.

| Study | Study periods | Comparison (absolute reduction or OR (IQR) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDM period | Control period | Mean daily admission | |||||||||

| References | Country & region | Setting | Period | Number of patients | Age of cohort | Period | Number of patients | Age of cohort | SDM period | Control period | |

| Araujo et al. (13) | Brazil | PICU n = 15 | March 1 to May 31, 2020 | 1181 | 4.3 (+/-6.9) | March 1 to May 31, 2017–2019 | 7,473 | NA | 12.98 | 27.37 | −53% |

| March 1 to May 31, 2019 | 2,564 | 2.5 (+/-3.7) 2019 | 28.18 | −54% | |||||||

| March 1 to May 31, 2018 | 2,599 | 2.6 (+/-6.7) 2018 | 28.56 | −55% | |||||||

| March 1 to May 31, 2017 | 2,310 | 2.8 (+/-3.8) 2017 | 25.38 | −49% | |||||||

| Degiorgio | Malta | PICU n = 1 | March 1 to May 9, 2020 | 3 | NA | March 1–May 9, 2019 | 8 | NA | 0.04 | 0.12 | −63% |

| Graciano AL | USA | PICU n = 1 | March 1 to 31 May, 2020 | 101 | NA | March 1 to 31 May, 2019 | 195 | NA | 1.11 | 2.14 | −48% |

| March 1 to 31 May, 2018 | 275 | 3.02 | −63% | ||||||||

| March 1 to 31 May, 2017 | 309 | 3.40 | −67% | ||||||||

| March 1 to 31 May, 2016 | 299 | 3.29 | −66% | ||||||||

| March 1 to 31 May, 2015 | 308 | 3.38 | −67% | ||||||||

| Lee L | USA/Singapore/ Australia/France |

ED n = 5 | Singapore, May 4, 2020 | NA | NA | Singapore, March 15, 2020 | NA | NA | NA | NA | −38 % |

| Paris, May 4, 2020 | Paris, March 15, 2020 | NA | NA | NA | +2% | ||||||

| Boston, May 4, 2020 | Boston, March 15, 2020 | NA | NA | NA | −12 % | ||||||

| Seattle, May 4, 2020 | Seattle, March 15, 2020 | NA | NA | NA | −36 % | ||||||

| Melbourne, May 4, 2020 | Melbourne, March 15, 2020 | NA | NA | NA | −34 % | ||||||

| Raman et al. (68) | India | ED n = 1 | April 1 to July 31, 2020 | 280 | NA | April 1 to July 31, 2019 | 790 | NA | 0.46 | 0.63 | −26% |

| 56/280 (20%) | 76/790 (9.6%) | 2.35 (1.61, 3.42), p <0.001 | |||||||||

| Sperotto et al. (71) | Italy | PICU n = 4 | February 24 to April 20, 2020 | 166 | NA | December 30, 2019, to February 24, 2020 | 277 | NA | 2.96 | 4.95 | −40% |

| February 24 to April 20, 2019 | 259 | 4.71 | −36% | ||||||||

| Williams e tal. (72) | Scotland | PICU n = 2 | March 23 to June 30, 2020 | 413 total | NA | March 23 to June 30, 2016-2019 | 413 total | NA | 413 total | NA | 0.52 (0.37–0.70), p <0.001 |

| Vásquez-Hoyos P | Colombia, Bolivia, Chile, Uruguay | PICU 22 | January 1 to August 31, 2020 | 234 | NA | January 1 to August 31, 2018–2019 | 2,807 | NA | 0.96 | 5.80 | −83% |

OR, Odds Ratio.

Impacts on Each Etiology of Illness

Respiratory Illness

Acute Respiratory Illness

Seven studies presented data regarding acute respiratory illnesses including 5 focusing on lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) (17, 23, 26, 58, 76, 83, 84) reported from Malta, Ireland, Italy, New Zealand and four South American countries (Colombia, Bolivia, Chile, and Uruguay) (Supplementary Table 4). There was a significant decline reported in acute respiratory illness and LRTI in the five studies, all of which examined data in the PED (17, 23, 26, 76, 84) during the SDM period compared with the control periods (median decrease of 63% [50–80%]). A study from the US found that the proportion of admissions related to respiratory illness was 3.6% of all the PED admissions during the SDM period compared with 22.8% during the same period during the 10 previous years (p < 0.001) (84). The two studies performed in PICU also found a marked reduction in PICU admissions due to LRTI during the SDM period (52 and 83%) (58, 83).

Bronchiolitis

Seven studies presented data regarding acute bronchiolitis admissions (13, 23, 32, 58, 71, 82, 85) from Brazil, Australia, Ireland, USA, Scotland and four South American countries (Colombia, Bolivia, Chile, and Uruguay) (Supplementary Table 5). Three studies were performed in PEDs and found a significant reduction in hospital admissions during the SDM period ranging from 34 to 85% (23, 32, 85). The other studies looked at the data in PICU and found a similar significant reduction in children requiring critical care admission for acute bronchiolitis with a median decrease of 73% [69–78%] (13, 58, 71, 82).

Asthma

Seven studies presented data regarding pediatric asthma admissions (13, 43, 65, 71, 86, 87) in Brazil, the USA, the UK, Slovenia, Japan, and Scotland. Four studies performed in PED found a decrease in admissions due to asthma from 32 to 90% (43, 65, 86, 87) and two studies performed in PICUs found similar findings with a decrease of 58 to 100% (13, 82) (Supplementary Table 6).

Viral Infections

Seven studies (14, 17, 23, 32, 58, 65, 84) showed data regarding viral infections in Australia, Ireland, Japan, USA, New Zealand, and four South American countries (Colombia, Bolivia, Chile, and Uruguay) (Supplementary Table 7), found a significant decrease in the number of admissions due to viral infection (23, 65).

Four studies (17, 32, 58, 84) included data on RSV infections requiring PED or PICU admission during the SDM period, all of which presented a significant reduction in the incidence of presentation with RSV infections in PED (17, 32, 84) as well as in PICU (58). Similarly, PED and PICU presentations for Influenza infection reduced dramatically during the SDM period in three studies (17, 58, 65) and more mildly in a Japanese study (14). On the contrary, a study performed in New Zealand found that hospitalizations for Adenovirus or Rhinovirus/Enterovirus infections during the SDM period stayed at a similar level to the previous years (17).

Injuries (Trauma, Burns and Poisoning)

Trauma

We included 32 studies with data regarding trauma admissions to PED (n = 29) (15, 16, 19–21, 23, 27, 29, 37, 40, 41, 44, 51, 52, 54, 56, 59, 62, 63, 65–67, 69, 70, 73, 74, 76, 88, 89), PICU (n = 2) (82, 83), and a study specifically looking at neurosurgery for head trauma in children (n = 1) (50) (Supplementary Table 8). Of the studies in the PED, 93% of the studies (27/29) found a significant decline in admissions linked to trauma with SDMs (median reduction of 48% [35–63%]). On the contrary, 7% (2/29) reported an increase in trauma admission (16, 40, 50).

The two studies including data from patients admitted to PICU found a decrease of trauma admissions from 17 to 61% (82, 83) during the SDM period.

Burns

We included five studies with data regarding burns (16, 44, 74, 78, 90) respectively from the UK, Italy, and Israel (Supplementary Table 9). Four studies (44, 74, 78, 90) reported a decrease in the number of burns presenting to the PED (from 22 to 66%); while one found a slight increase in the number of burns (16) during the SDM period. However, the severity of burns at the time of hospital presentation was higher for the SDM cohorts compared to the historical (44, 78, 90). A study from the UK (78) reported that more patients presented with burns with greater total body surface area (TBSA); 50% of the patients with >5% TBSA burns in the COVID-19 pandemic compared with 5% in the control period. The study in Israel reported that the majority of burns were scalded during the SDM period; while, during previous years, causes of burns were more diverse, including scald, contact, fire, sun, and chemical injuries (44).

Poisoning

We included three studies with data regarding poisoning (16, 23, 59) respectively from Italy, Ireland, and Spain (Supplementary Table 10). Two of them (16, 23) did not find a significant change in the number of PED presentations for poisoning; while one found a 76% decrease in the number of hospital admissions (59). One study differentiated accidental from deliberate poisoning (23) with no differences found in both series. An Italian study found an increased incidence ratio for hospitalization in intoxicated children during the SDM period (9.0 (0.5 to 167.2), p = 0.14).

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

We found 4 studies with data regarding diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) (31, 47, 65, 91) each from the UK, Germany, Australia, and the USA (Supplementary Table 11). Three of them found an overall increase in the referral of DKA to ED compared with previous years (93 to 264% increase). These studies also found an increase in admission of severe DKA; and the initial pH, bicarbonate and glucose levels at hospital presentations were significantly worse in the SDM group compared to the historical cohort (31, 47).

Surgery

Unplanned Surgery

A total of 20 studies met the inclusion criteria looking at unplanned surgeries, in Australia, China, France, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Scotland, the UK, and the USA (14, 23, 33, 36, 45, 49, 52, 57, 60, 65, 66, 68, 75–77, 82, 83, 92–95) (Supplementary Table 12). These examined data on PED/PICU admissions for acute surgical conditions, appendicitis, intussusception, testicular torsion, and pyloric stenosis as well as data on emergency surgeries performed.

Regarding studies including data on acute surgical disease, two studies found a decrease in the number of admission for acute surgical disease to PED and PICU from 9 to 40% although non-significant in the PICU (23, 83). Regarding the number of emergency surgeries performed for acute conditions, most studies found a decrease from 25 to 70% in the SDM period (77, 92, 93).

Four studies found an increase in the number of admissions with acute appendicitis during the SDM period ranging from 18 to 64% (33, 36, 45, 68). Two studies also addressed the significant increase in the proportion of perforated appendicitis (33, 68). On the contrary, three studies found a decrease in the number of admissions for appendicitis from 16 to 71% (49, 65, 76).

In addition, two studies found an increase in the number of testicular torsions (60, 65), one study found an increase in the number of pyloric stenosis (94) and one study found a decrease in the number of intussusception (65) during the SDM period compared with control periods.

Neurosurgery and Cardiac Surgery

Three studies reported the data of incidence of cardiac surgery for congenital heart disease during the SDM period in China, Italy, and Turkey (34, 42, 96). All three found a decrease in mean daily cases of cardiac surgery performed during the SDM period with a reduction of 52 to 88%.

Regarding studies on pediatric neurosurgery, only one study was included (50). The study reported an increase in the number of hospital admission in a pediatric neurosurgical unit during the SDM period by 14.7%.

Discussions

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially during the first wave, several modes of SDMs have been issued in most countries and regions, including school closures and restrictions on children's social activities (97). The COVID-19 pandemic was the first global pandemic in modern society with such a great impact on contemporary medical infrastructures. Therefore, facing the threat to healthcare systems capacities, SDMs were widely imposed worldwide as emergency measures and their consequences on other diseases than COVID-19 had never been described. Since then, the effects of SDM on the epidemiological dynamics of patients have been examined in various countries and regions. This systematic review summarized these studies and integrated the knowledge on the effect of SDM on acute illness in children to prepare for potential future pandemic threats during which the question of implementing SDM might arise again.

We found that SDMs in both developed and developing countries brought down the incidence of PED visits while the severity of illness at the time of the visit increased. Regarding the number of PED visits, this phenomenon might have occurred due to the decrease of morbidity or due to the avoidance of hospital visits associated with the current pandemic. The increased severity of patients might have resulted from the fact that parents tended to wait to present to the PED when their children got sick instead of immediate visits. Public communication and outreach are warranted to encourage parents/guardians to seek appropriate medical attention for emergencies of their children (28).

Likewise, a decrease in PICU admissions was also observed in almost all the reports. These results suggested that the reduction of the incidence of seasonal viral infections, and the resulting decline in the number of patients with respiratory diseases, one of the most common causes of admission to PICU, were the possible major factors behind. There was nearly a 50% decrease in general in the number of PICU admissions, and this can be important preliminary information for securing hospital beds in the event of a future pandemic or disaster, for instance, as a consequence of SDMs. These results have been confirmed by other studies published more recently (98–100).

In this study, we also compiled information on poisoning, trauma, and burns. Despite the isolation of children at home and its associated consequences both on mental health and on the access to potential accidental poisons, none of the included studies found a significant increase in accidental or deliberate poisoning. However, with the repetition of SDMs and the duration of the pandemic, the mental health of children and teenagers was strongly impacted and many studies were published since then reporting an increased incidence of mental health disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic (101, 102) but this does not seem to result in intentional poisoning increase (103).

As for burns, the number of cases decreased, but the severity at the time of consultation increased. It was encouraging that pandemic with SDMs did not translate into an increase of pediatric burn; however, parents might have chosen to seek advice from other services such as local pharmacies to avoid visits to the PED, which might explain the severity of burn at a hospital visit. The causes were more likely to be scald which might be explained by the increase in time spent at home. As for traumatic injuries, there was a general downward trend, and we believe that this was largely due to the eviction from school and the drop-in outdoor activities of kids.

DKA tended to increase, as well as the severity of the disease at the time of the hospital visit. We could assume that anxiety about presenting to the hospital led to a delay in diagnosis or receiving treatment before getting a critical condition. There has also been speculation that COVID-19 infection itself could trigger the development of DKA via direct damage to pancreatic beta cells, which might increase its actual incidence (104).

Lastly, regarding surgeries, the incidence of acute appendicitis requiring surgical intervention also increased during the SDM period, and the rate of perforated cases was reported to have risen. This might also be a result of the fact that the patients refrained from seeking medical attention until the last minute of the condition. On the contrary, the number of planned surgeries decreased significantly due to the organizational changes in the SDMs. Since a large proportion of pediatric surgical conditions, including congenital heart disease, cannot be performed on a standby basis, this might have had a significant impact on subsequent patient outcomes.

This study had limitations. First, different policies and timings of implementation must have been taken by the countries or regions in SDMs (105) although the measures were overall more strict (including national lockdowns) and similar during the first wave than during subsequent ones. For example, during the first wave, regulations and their compelling force differed from province to province and country to country. For example, in Canada, regulations for wearing masks in schools and indoors were established relatively quickly, but outdoor measures were delayed in some provinces. In some countries, such as Japan, there were no governmental regulations with strong compelling force issued as Canada, but only regulations based on a request basis to the public. Second, the magnitude of the wave of the pandemic varied from country to country, and the size of the effect of SDM itself may have been affected by this. Furthermore, since the seasons are different in the northern and southern hemispheres during the first wave, the impact of SDM on infection, respiratory diseases, and social activities may have been different in each country. Lastly, the historical cohorts to be compared in each study could be heterogeneous, and we believe that we should be cautious in evaluating them.

In conclusion, this review found that acute pediatric hospital care was significantly affected by the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic and related SDMs in a wide range of ways. Overall admissions to PED and PICU significantly decreased. Some diseases, such as infectious diseases, decreased, while others increased in incidence and severity such as DKA. The continual effort and research in the field should be essential for us to better comprehend the effects of this new phenomenon of SDMs, to aim at minimizing possible collateral damage caused by such delays in emergency healthcare utilization, which eventually leads to protecting the well-being of children. These lessons we learned here should count for options for structuring SDMs if needed in response to future local outbreaks or pandemics in our modern society, especially given the potential harm of SDM on children's well-being (106).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

AK and ML conceptualized, designed the review and carried out a systematic review and subsequent analysis, drafted the initial manuscript (method and result part), revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. AK also constructed a search formula and searched. VL assessed all the titles and abstracts that remained in disagreement between the two investigators AK and ML. CS performed the statistical analyses. VL, CS, and PJ reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final version as submitted. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Appendix 1

Each digital database was searched with the following search terms.

i) Population: “pediatrics”, “infant, newborn”, “child”, “adolescent”, “infant” and “newborn”.

ii) Exposures: “social distancing”, “measure”, “policy”, “regulation”, “quarantine”, “isolation”, “non-pharmacological interventions” combined with “COVID-19”, “Novel Coronavirus” or “SARS-COV2”.

iii) Outcomes: “Hospitalization”, “admission”, “incidence”, “occurrence”.

The search strategy used MeSH terms unless indicated otherwise.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2022.874045/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Ouldali N, Yang DD, Madhi F, Levy M, Gaschignard J, Craiu I, et al. Factors associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatrics. (2021) 147:e2020023432. 10.1542/peds.2020-023432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu W, Zhang Q, Chen J, Xiang R, Song H, Shu S, et al. Detection of Covid-19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1370–1. 10.1056/NEJMc2003717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei M, Yuan J, Liu Y, Fu T, Yu X, Zhang ZJ. Novel Coronavirus infection in hospitalized infants under 1 year of age in China. JAMA. (2020) 323:1313–4. 10.1001/jama.2020.2131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xia W, Shao J, Guo Y, Peng X, Li Z, Hu D. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infection: different points from adults. Pediatr Pulmonol. (2020) 55:1169–74. 10.1002/ppul.24718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Litvinova M, Liu QH, Kulikov ES, Ajelli M. Reactive school closure weakens the network of social interactions and reduces the spread of influenza. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2019) 116:13174–81. 10.1073/pnas.1821298116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryu S, Ali ST, Cowling BJ, Lau EHY. Effects of School Holidays on Seasonal Influenza in South Korea, 2014–2016. J Infect Dis. (2020) 222:832–5. 10.1093/infdis/jiaa179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson C, Mangtani P, Hawker J, Olowokure B, Vynnycky E. The effects of school closures on influenza outbreaks and pandemics: systematic review of simulation studies. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e97297. 10.1371/journal.pone.0097297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrlich H, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Strategic planning and recommendations for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. (2020) 38:1446–7. 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.03.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. Available online at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed February 3, 2021).

- 10.Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth. (2020) 18:2127–33. 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akuaake LM, Hendrikse C, Spittal G, Evans K, Van Hoving DJ. Cross-sectional study of paediatric case mix presenting to an emergency centre in Cape Town, South Africa, during COVID-19. BMJ Paediatrics Open. (2020) 4:e000801. 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angoulvant F, Ouldali N, Yang DD, Filser M, Gajdos V, Rybak A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impact caused by school closure and national lockdown on pediatric visits and admissions for viral and non-viral infections, a time series analysis. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 72:319–22. 10.1093/cid/ciaa710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Araujo OR, Almeida CG, Lima-Setta F, Prata-Barbosa A, Colleti Junior J. The impact of the novel coronavirus on Brazilian PICUs. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2020) 21:1059–63. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kishimoto K, Bun S, Shin J, Takada D, Morishita T, Kunisawa S, et al. Early impact of school closure and social distancing for COVID-19 on the number of inpatients with childhood non-COVID-19 acute infections in Japan. Eur J Pediatr. (2021) 180:2871–8. 10.1007/s00431-021-04043-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baxter I, Hancock G, Clark M, Hampton M, Fishlock A, Widnall J, et al. Paediatric orthopaedics in lockdown: a study on the effect of the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic on acute paediatric orthopaedics and trauma. Bone Jt Open. (2020) 1:424–30. 10.1302/2633-1462.17.BJO-2020-0086.R1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bressan S, Gallo E, Tirelli F, Gregori D, Da Dalt L. Lockdown: more domestic accidents than COVID-19 in children. Arch Dis Child. (2021) 106:e3. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trenholme A, Webb R, Lawrence S, Arrol S, Taylor S, Ameratunga S, et al. COVID-19 and infant hospitalizations for seasonal respiratory virus infections, New Zealand, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. (2021) 27:641–3. 10.3201/eid2702.204041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chelo D, Mekone Nkwelle I, Nguefack F, Mbassi Awa HD, Enyama D, Nguefack S, et al. Decrease in hospitalizations and increase in deaths during the Covid-19 epidemic in a pediatric hospital, Yaounde-Cameroon and prediction for the coming months. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. (2021) 40:18–31. 10.1080/15513815.2020.1831664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bram JT, Johnson MA, Magee LC, Mehta NN, Fazal FZ, Baldwin KD, et al. Where have all the fractures gone? The epidemiology of pediatric fractures during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pediatr Orthop. (2020) 40:373–9. 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciofi Degli Atti ML, Campana A, Muda AO, Concato C, Rav L, Ricotta L, et al. Facing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic at a COVID-19 regional children's hospital in Italy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2020) 39:e221–5. 10.1097/INF.0000000000002811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Claudet I. March, -Tonel C, Ricco L, HouzRicco L, C-H, Lang T, Br-H, C. During the COVID-19 quarantine, home has been more harmful than the virus for children! Pediatr Emerg Care. (2020) 36:e538–40. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clavenna A, Nardelli S, Sala D, Fontana M, Biondi A, Bonati M. Impact of COVID-19 on the pattern of access to a pediatric emergency department in the Lombardy region, Italy. Pediatr Emerg Care. (2020) 36:e597–8. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dann L, Fitzsimons J, Gorman KM, Hourihane J, Okafor I. Disappearing act: COVID-19 and pediatric emergency department attendances. Arch Dis Child. (2020) 105:810–1. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davico C, Marcotulli D, Lux C, Calderoni D, Terrinoni A, Di Santo F, et al. Where have the children with epilepsy gone? An observational study of seizure-related accesses to emergency department at the time of COVID-19. Seizure. (2020) 83:38–40. 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.09.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dean P, Zhang Y, Frey M, Shah A, Edmunds K, Boyd S, et al. The impact of public health interventions on critical illness in the pediatric emergency department during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. (2020) 1:1542–51. 10.1002/emp2.12220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Degiorgio S, Grech S, Dimech Y, Xuereb J, Grech V. COVID-19 related acute decline in paediatric admissions in Malta, a population-based study. Early Hum Dev. (2020) 12:105251. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christey G, Amey J, Campbell A, Smith A. Variation in volumes and characteristics of trauma patients admitted to a level one trauma centre during national level 4 lockdown for COVID-19 in New Zealand. N Z Med J. (2020) 133:81–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dopfer C, Wetzke M, Zychlinsky Scharff A, Mueller F, Dressler F, Baumann U, et al. COVID-19 related reduction in pediatric emergency healthcare utilization - a concerning trend. BMC Pediatr. (2020) 20:427. 10.1186/s12887-020-02303-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong FL, Antoniou G, Williams N, Cundy PJ. Disruption of paediatric orthopaedic hospital services due to the COVID-19 pandemic in a region with minimal COVID-19 illness. J Child Orthop. (2020) 14:245–51. 10.1302/1863-2548.14.200140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrero F, Ossorio MF, Torres FA, Debaisi G. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the paediatric emergency department attendances in Argentina. Arch Dis Child. (2021) 106:e5. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamrath C MC Mth CK Biester T Rohrer TR Warncke K et al. Ketoacidosis in children and adolescents with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. JAMA. (2020) 324:801n Ge 10.1001/jama.2020.13445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Britton PN, Hu N, Saravanos G, Shrapnel J, Davis J, Snelling T, et al. COVID-19 public health measures and respiratory syncytial virus. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2020) 4:e42–3. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30307-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher JC, Tomita SS, Ginsburg HB, Gordon A, Walker D, Kuenzler KA. Increase in pediatric perforated appendicitis in the New York City metropolitan region at the epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann Surg. (2021) 273:410VID- 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi G Huang J Pi M Chen X Li X Ding Y Zhang H National National Association of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery Working Group . Impact of early COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric cardiac surgery in China. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. (2020) 161:1605–14. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.11.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldman RD, Grafstein E, Barclay N, Irvine MA, Portales-Casamar E. Paediatric patients seen in 18 emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg Med J. (2020) 37:773–7. 10.1136/emermed-2020-210273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerall CD, DeFazio JR, Kahan AM, Fan W, Fallon EM, Middlesworth W, et al. Delayed presentation and sub-optimal outcomes of pediatric patients with acute appendicitis during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pediatr Surg. (2021) 56:905Surgr 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hampton M, Clark M, Baxter I, Stevens R, Flatt E, Murray J, et al. The effects of a UK lockdown on orthopaedic trauma admissions and surgical cases: a multi-centre comparative study. Bone Jt Open. (2020) 1:137–43. 10.1302/2633-1462.15.BJO-2020-0028.R1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, Coletta MA, Boehmer TK, Adjemian J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits - United States, January 1, 2019-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2020) 69699–704. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes HE, Hughes TC, Morbey R, Challen K, Oliver I, Smith GE, et al. Emergency department use during COVID-19 as described by syndromic surveillance. Emerg Med J. (2020) 37:600–4. 10.1136/emermed-2020-209980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iozzi L, Brambilla I, Foiadelli T, Marseglia GL, Cipr IG. Paediatric emergency department visits fell by more than 70% during the COVID-19 lockdown in Northern Italy. Acta Paediatr. (2020) 109:2137–8. 10.1111/apa.15458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rose K, Zyl KV, Cotton R, Wallace S, Cleugh F. Paediatric attendances and acuity in the emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. (2020) 2020:8666. 10.1101/2020.08.05.2016866633127743 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korun O, Yurdakök O, Arslan A, Çiçek M, Selçuk A, Kiliç Y, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on congenital heart surgery practice: An alarming change in demographics. J Card Surg. (2020) 35:2908–12. 10.1111/jocs.14914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krivec U, Kofol Seliger A, Tursic J. COVID-19 lockdown dropped the rate of paediatric asthma admissions. Arch Dis Child. (2020) 105:809–10. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kruchevsky D, Arraf M, Levanon S, Capucha T, Ramon Y, Ullmann Y. Trends in burn injuries in Northern Israel during the COVID-19 lockdown. J Burn Care Res. (2021) 42:135–40. 10.1093/jbcr/iraa154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kvasnovsky CL, Shi Y, Rich BS, Glick RD, Soffer SZ, Lipskar AM, et al. Limiting hospital resources for acute appendicitis in children: lessons learned from the US epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pediatr Surg. (2021) 56:900Surg 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lalarukh ARJDS. 468 Presentation of vulnerable children in Finland during earla. Emerg Med J : EMJ. (2020) 37:852–52. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lawrence C, Seckold R, Smart C, King BR, Howley P, Feltrin R, et al. Increased paediatric presentations of severe diabetic ketoacidosis in an Australian tertiary centre during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabet Med. (2021) 38:e14417. 10.1111/dme.14417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee L, Mannix R, Guedj R, Chong SL, Sunwoo S, Woodward T, et al. Paediatric ED utilisation in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg Med J. (2021) 38:100–2. 10.1136/emermed-2020-210124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee-Archer P, Blackall S, Campbell H, Boyd D, Patel B, McBride C. Increased incidence of complicated appendicitis during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Paediatr Child Health. (2020) 56:1313–313:0iatr C1111/jpc.15058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dyson EW, Craven CL, Tisdall MM, James GA. The impact of social distancing on pediatric neurosurgical emergency referrals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective observational cohort study. Childs Nerv Syst. (2020) 36:1821–3. 10.1007/s00381-020-04783-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lv H, Zhang Q, Yin Y, Zhu Y, Wang J, Hou Z, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of traumatic fractures during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A retrospective & comparative multi-center study. Injury. (2020) 51:1698–704. 10.1016/j.injury.2020.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manzoni P, Militello MA, Fiorica L, Cappiello AR, Manzionna M. Impact of COVID-19 epidemics in pediatric morbidity and utilization of hospital pediatric services in Italy. Acta Paediatr. (2021) 110:1369–70. 10.1111/apa.15435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McDonnell T, Nicholson E, Conlon C, Barrett M, Cummins F, Hensey C, et al. Assessing the impact of COVID-19 public health stages on paediatric emergency attendance. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:6719. 10.3390/ijerph17186719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matthay ZA, Kornblith AE, Matthay EC, Sedaghati M, Peterson S, Boeck M, et al. The distance study: determining the impact of social distancing on trauma epidemiology during the COVID-19 epidemic-an interrupted time-series analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. (2021) 90:700–7. 10.1097/TA.0000000000003044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mekaoui N, Razine R, Bassat Q, Benjelloun BS, Karboubi L. The effect of COVID-19 on paediatric emergencies and admissions in Morocco: cannot see the forest for the trees? J Trop Pediatr. (2021) 67:fmaa046. 10.1093/tropej/fmaa046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Memeo A Priano D Caldarini C Trezza P Laquidara M Montanari L R elli P. How the pandemic spread of COVID-19 affected children's traumatology in Italy: changes of numbers, anatomical locations, and severity. Minerva Pediatr. (2020) 10.23736/S0026-4946.20.05910-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Montalva L, Haffreingue A, Ali L, Clariot S, Julien-Marsollier F, Ghoneimi AE, et al. The role of a pediatric tertiary care center in avoiding collateral damage for children with acute appendicitis during the COVID-19 outbreak. Pediatr Surg Int. (2020) 36:1397–397:0r Surg I1007/s00383-020-04759-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vásquez-Hoyos P, Diaz-Rubio F, Monteverde-Fern N, Jaramillo-Bustamante JC, Carvajal C, Serra A, et al. Reduced PICU respiratory admissions during COVID-19. Arch Dis Child. (2020) 106:808–11. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Molina Gutiérrez M, Ruiz Domínguez JA, Bueno Barriocanal M, de Miguel Lavisier B, López López R, Martín Sánchez J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department: Early findings from a hospital in Madrid. An Pediatr. (2020) 93:313–22. 10.1016/j.anpede.2020.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nelson CP, Kurtz MP, Logvinenko T, Venna A, McNamara ER. Timing and outcomes of testicular torsion during the COVID-19 crisis. J Pediatr Urol. (2020) 16:841. 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nourazari S, Davis SR, Granovsky R, Austin R, Straff DJ, Joseph JW, et al. Decreased hospital admissions through emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. (2021) 42:203–10. 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.11.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nabian MH, Vosoughi F, Najafi F, Khabiri SS, Nafisi M, Veisi J, et al. Epidemiological pattern of pediatric trauma in COVID-19 outbreak: data from a tertiary trauma center in Iran. Injury. (2020) 51:2811–5. 10.1016/j.injury.2020.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park C, Sug K, Nathwani D, Bhattacharya R, Sarraf KM. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on orthopedic trauma workload in a London level 1 trauma center: the golden month. Acta Orthop. (2020) 91:556–61. 10.1080/17453674.2020.1783621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Palladino F, Merolla E, Solimeno M, de Leva MF, Lenta S, Di Mita O, et al. Is Covid-19 lockdown related to an increase of accesses for seizures in the emergency department? An observational analysis of a paediatric cohort in the Southern Italy. Neurol Sci. (2020) 41:3475–83. 10.1007/s10072-020-04824-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pines JM, Zocchi MS, Black BS, Carlson JN, Celedon P, Moghtaderi A, et al. Characterizing pediatric emergency department visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. (2021) 41:201–4. 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.11.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peiro-Garcia A, Corominas L, Coelho A, DeSena-DeCabo L, Torner-Rubies F, Fontecha CG. How the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting paediatric orthopaedics practice: a preliminary report. J Child Orthop. (2020) 14:154–60. 10.1302/1863-2548.14.200099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qasim Z, Sjoholm LO, Volgraf J, Sailes S, Nance ML, Perks DH, et al. Trauma center activity and surge response during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic-the Philadelphia story. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. (2020) 89:821–8. 10.1097/TA.0000000000002859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Place R, Lee J, Howell J. Rate of Pediatric Appendiceal perforation at a children's hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the previous year. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2027948. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raitio A, Ahonen M, Jääskelä M, Jalkanen J, Luoto TT, Haara M, et al. Reduced number of pediatric orthopedic trauma requiring operative treatment during COVID-19 restrictions: a nationwide cohort study. Scand J Surg. (2021) 110:254–7. 10.1177/1457496920968014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sheridan GA, Nagle M, Russell S, Varghese S, O'Loughlin PF, Boran S, et al. Pediatric trauma and the COVID-19 pandemic: a 12-year comparison in a level-1 trauma center. HSS J. (2020) 16:92–6. 10.1007/s11420-020-09807-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Graciano AL, Bhutta AT, Custer JW. Reduction in paediatric intensive care admissions during COVID-19 lockdown in Maryland, USA. BMJ Paediatr Open. (2020) 4:e000876. 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scaramuzza A, Tagliaferri F, Bonetti L, Soliani M, Morotti F, Bellone S, et al. Changing admission patterns in paediatric emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dis Child. (2020) 105:704–6. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Turgut A, Arli H, Altundag Ü, Hancioglu S, Egeli E, Kalenderer Ö. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the fracture demographics: Data from a tertiary care hospital in Turkey. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. (2020) 54:355–63. 10.5152/j.aott.2020.20209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Valitutti F, Zenzeri L, Mauro A, Pacifico R, Borrelli M, Muzzica S, et al. Effect of population lockdown on pediatric emergency room demands in the era of COVID-19. Front Pediatr. (2020) 8:521. 10.3389/fped.2020.00521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Velayos M, Muñoz-Serrano AJ, Estefanía-Fernández K, Sarmiento Caldas MC, Moratilla Lapeña L, López-Santamaría M, et al. Influence of the coronavirus 2 (SARS-Cov-2) pandemic on acute appendicitis. An Pediatr. (2020) 93:118–22. 10.1016/j.anpede.2020.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vierucci F, Bacci C, Mucaria C, Dini F, Federico G, Maielli M, et al. How COVID-19 pandemic changed children and adolescents use of the emergency department: the experience of a secondary care pediatric unit in central Italy. SN Compr Clin Med. (2020) 2:1959–69. 10.1007/s42399-020-00532-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wei Y, Yu C, Zhao TX, Lin T, Dawei HE, Wu SD, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric operations: a retrospective study of Chinese children. Ital J Pediatr. (2020) 46:155. 10.1186/s13052-020-00915-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.D .0000 F, Choong J, Thomas C, Adamson J, Wilson Y, Wilson D, et al. Paediatric burns epidemiology during COVID-19 pandemic and demic and d on tBurns. (2020) 46:1471–2. 10.1016/j.burns.2020.06.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Isba R, Edge R, Auerbach M, Cicero MX, Jenner R, Setzer E, et al. COVID-19: transatlantic declines in pediatric emergency admissions. Pediatr Emerg Care. (2020) 36:551–3. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuitunen I Artama M MM Ma L Backman K Heiskanen-Kosma T Renko M. Effect of social distancing due to the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of viral respiratory tract infections in children in Finland during early 2020. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2020) 39:e423–7. 10.1097/INF.0000000000002845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Raman R, Madhusudan M. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on admissions to the pediatric emergency department in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pediatr. (2021) 88:392. 10.1007/s12098-020-03562-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams T, MacRae C, Swann O, Haseeb H, Cunningham C, Davies P, et al. Indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric health-care use and severe disease: a retrospective national cohort study. Arch Dis Child. (2021) 106:911Childects of1136/archdischild-2020-321008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sperotto F, Wolfler A, Biban P, Montagnini L, Ocagli H, Comoretto R, et al. Unplanned and medical admissions to pediatric intensive care units significantly decreased during COVID-19 outbreak in Northern Italy. Eur J Pediatr. (2021) 180:643–8. 10.1007/s00431-020-03832-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nolen LD, Seeman S, Bruden D, Klejka J, Desnoyers C, Tiesinga J, et al. Impact of social distancing and travel restrictions on non-COVID-19 respiratory hospital admissions in young children in rural Alaska. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 72:2196–8. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Friedrich F, Ongaratto R, Scotta MC, Veras TN, Stein R, Lumertz MS, et al. Early Impact of social distancing in response to COVID-19 on hospitalizations for acute bronchiolitis in infants in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 72:2071–5. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chavasse R, Almario A, Christopher A, Kappos A, Shankar A. The indirect impact of COVID-19 on children with Asthma. Arch Bronconeumol. (2020) 56:768–9. 10.1016/j.arbres.2020.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bun S, Kishimoto K, Shin J. -h, Takada D, Morishita T, Kunisawa S, Imanaka Y. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on infant and pediatric asthma: a multi-center survey using an administrative database in Japan. Allergol Int. (2021) 70:489–91. 10.1101/2020.11.29.20240374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dhillon MS, Kumar D, Saini UC, Bhayana H, Gopinathan NR, Aggarwal S. Changing pattern of orthopaedic trauma admissions during COVID-19 pandemic: experience at a tertiary trauma centre in India. Indian J Orthop. (2020) 54:1–6. 10.1007/s43465-020-00241-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sherman WF, Khadra HS, Kale NN, Wu VJ, Gladden PB, Lee OC. How did the number and type of injuries in patients presenting to a regional level i trauma center change during the COVID-19 pandemic with a stay-at-home order? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2021) 479:266–75. 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mann JA, Patel N, Bragg J. Rol, D. Did children “stay safe”? Evaluation of burns presentations to a children's emergency department during the period of COVID-19 school closures. Arch Dis Child. (2021) 106:e18. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Basatemur E, Jones A, Peters M, Ramnarayan P. Paediatric critical care referrals of children with diabetic ketoacidosis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dis Child. (2021) 106:e21. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gunadi Idham Y Paramita VMW Fauzi AR Dwihantoro A Makhmudi A. The Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric surgery practice: a cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg. (2020) 59:96–100. 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Okonkwo INC, Howie A, Parry C, Shelton CL, Cobley S, Craig R, et al. The safety of paediatric surgery between COVID-19 surges: an observational study. Anaesthesia. (2020) 75:1605–605:0hesiay 1111/anae.15264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Research Network PST, Arthur F, Harwood R, Allin B, Bethell GS, Boam T, et al. Lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic: impact on infants with pyloric stenosis. Arch Dis Child. (2020) 106:e32. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zampieri N, Cinquetti M, Murri V, Camoglio FS. Incidence of appendicitis during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic quarantine: report of a single area experience. Minerva Pediatr. (2020) 56. 10.23736/S0026-4946.20.05901-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Giamberti A, Varrica A, Agati S, Gargiulo G, Luciani GB, Marianeschi SM, et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the Italian congenital cardiac surgery system: a national survey. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2020) 58:1254–60. 10.1093/ejcts/ezaa352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Viner RM, Russell SJ, Croker H, Packer J, Ward J, Stansfield C, et al. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2020) 4:397–404. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30095-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zee-Cheng JE, McCluskey CK, Klein MJ, Scanlon MC, Rotta AT, Shein SL, et al. Changes in pediatric ICU utilization and clinical trends during the coronavirus pandemic. Chest. (2021) 160:529–37. 10.1016/j.chest.2021.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Breinig S, Mortamet G, Brossier D, Amadieu R, Claudet I, Javouhey E, et al. Impact of the french national lockdown on admissions to 14 pediatric intensive care units during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic-a retrospective multicenter study. Front Pediatr. (2021) 9:764583. 10.3389/fped.2021.764583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maddux AB, Campbell K, Woodruff AG, LaVelle J, Lutmer J, Kennedy CE, et al. The impact of strict public health restrictions on pediatric critical illness. Crit Care Med. (2021) 49:2033–41. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chadi N, Ryan NC, Geoffroy MC. COVID-19 and the impacts on youth mental health: emerging evidence from longitudinal studies. Can J Public Health. (2022) 113:44–52. 10.17269/s41997-021-00567-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Elharake JA, Akbar F, Malik AA, Gilliam W, Omer SB. Mental health impact of COVID-19 among children and college students: a systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2022) 11:1–13. 10.1007/s10578-021-01297-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schultz BRE, Hoffmann JA, Clancy C, Ramgopal S. Hospital encounters for pediatric ingestions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Toxicol (Phila). (2022) 60:269–71. 10.1080/15563650.2021.1925687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]