Abstract

The Teredinidae (shipworms) are a morphologically diverse group of marine wood-boring bivalves that are responsible each year for millions of dollars of damage to wooden structures in estuarine and marine habitats worldwide. They exist in a symbiosis with cellulolytic nitrogen-fixing bacteria that provide the host with the necessary enzymes for survival on a diet of wood cellulose. These symbiotic bacteria reside in distinct structures lining the interlamellar junctions of the gill. This study investigated the mode by which these nutritionally essential bacterial symbionts are acquired in the teredinid Bankia setacea. Through 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequencing, the symbiont residing within the B. setacea gill was phylogenetically characterized and shown to be distinct from previously described shipworm symbionts. In situ hybridization using symbiont-specific 16S rRNA-directed probes bound to bacterial ribosome targets located within the host gill coincident with the known location of the gill symbionts. These specific probes were then used as primers in a PCR-based assay which consistently detected bacterial rDNA in host gill (symbiont containing), gonad tissue, and recently spawned eggs, demonstrating the presence of symbiont cells in host ovary and offspring. These results suggest that B. setacea ensures successful inoculation of offspring through a vertical mode of symbiont transmission and thereby enables a broad distribution of larval settlement.

Shipworms (family Teredinidae) are a morphologically and physiologically diverse group of marine bivalve mollusks notorious for their wood-boring lifestyle. Their ability to bore into wood results in millions of dollars of damage annually to wooden structures in both marine and estuarine systems worldwide. The amazing diversity of this family is reflected in the wide range of reproductive strategies, ranging from the brooding of young for the entire 4-week larval development period to the broadcast spawning of gametes.

Like nearly all animals, shipworms are unable to metabolize wood cellulose directly but rely on an obligate association with cellulolytic bacteria (22, 34, 35). Electron microscopy has localized the symbionts to the Gland of Deshayes, a specialized region of the host gill corresponding to the interlamellar junction of the right and left demibranches (7, 25, 28, 32). Unlike symbioses of bivalves with chemoautotrophic bacteria, in the shipworm associations the symbionts can be cultured separately from the host. Symbionts isolated from seven shipworm host species are currently maintained in culture (this study and reference 35). In vitro gill isolates synthesize both cellulolytic and proteolytic enzymes for digestion, as well as nitrogenase for atmospheric nitrogen fixation (14, 15, 16). It has been suggested that these microbially derived enzymes provide the bivalve host with the ability to thrive on a diet of wood alone.

A previous phylogenetic analysis of teredinid symbionts demonstrated that four isolates from geographically distinct regions had identical 16S rRNA gene sequences, placing this consensus bacterium (Teredinibacter turnerae) within the gamma subdivision of the Proteobacteria (7). This study also demonstrated that a 16S rRNA isolate-specific probe hybridized with the resident bacteria in teredinid gill tissue (7). Linking the physiological capabilities of these isolates to the symbiotic microbes within the shipworm host further validated the notion that the shipworm's nutritional success on a wood substrate is made possible by a suite of microbially derived enzymes.

The success of the shipworm life strategy hinges on an obligate symbiosis with cellulolytic microbes, but the mode by which this vital association is established in each successive host generation has not been described. The utility of nucleic acid probe technology for studying symbiont transfer has been demonstrated in numerous marine invertebrate systems (4, 5, 6, 17, 20). These studies rely on the sensitivity of nucleic acid hybridization techniques to identify the presence or absence of symbiont genes within the host gonad and eggs, thus inferring a mode of symbiont transfer. Successful gene amplification and in situ hybridization with symbiont 16S rRNA gene-directed probes demonstrated the presence of symbionts in the follicle cells surrounding the primary oocytes of the deep-sea vesicomyid clams (5) and in the eggs and larvae of the Protobranch bivalve Solemya reidi (4). These experiments suggested that the chemoautotrophic endosymbiotic bacteria resident in these bivalves are vertically transmitted. Using a similar approach, the endosymbionts from the hydrothermal vent tube worm Riftia pachyptila have never been detected in host reproductive tissues or eggs, thus implying transmission of the symbionts from the environment rather than through a direct transfer from parent to offspring (6).

Here, we seek to ascertain the mode of symbiont transmission in Bankia setacea (Tryon), a broadcast spawning teredinid species indigenous to the Pacific Northwest coast of the United States. B. setacea causes extensive damage in the Pacific Northwest, where forestry concerns depend on transportation and storage in marine systems (12). In light of data demonstrating that geographically distinct and diverse species of shipworms harbor symbionts that are genetically identical (7), an hypothesis of horizontal (i.e., environmental) transmission was proposed for B. setacea. However, phylogenetic characterization of the B. setacea gill symbiont 16S rRNA and in situ hybridization studies suggested that the symbiont of this species was unique. Symbiont-specific 16S rRNA primers were designed and used in a PCR-based detection strategy for symbiont genes within the host reproductive tissue and freshly spawned eggs to elucidate the mode of symbiont transmission in the shipworm B. setacea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens.

Adult B. setacea organisms were collected from Yaquina Bay, Oreg. (44°N, 124°W), between September 1996 and October 1997. Animals were obtained through the deployment of pine collection panels (31) that remained submerged for a 6-month period. Panels were retrieved from Yaquina Bay, wrapped in moist paper towels, and transported to a quarantined recirculating seawater system (10°C) at the University of Delaware College of Marine Studies, Lewes. Adults were removed from the wood by hand, and each was maintained separately in filtered (0.2-μm-pore-size filter) sterile seawater. Gravid adults often spawned spontaneously upon removal from the wood. After release, eggs were immediately collected, washed in sterile seawater, and prepared for nucleic acid extraction. Following a spawning event, the adults were dissected aseptically and processed for either microscopic or molecular studies. Ovarial tissue was always the first tissue to be dissected. To prevent contamination of ovarial tissue with symbiont-containing gill tissue, ovaries were sampled in the ventral region, separated from the dorsally located gill lamellae. All samples were flushed multiple times with sterile seawater to reduce external contaminants.

Symbiont isolation.

The control symbiont T. turnerae strain TBTC was isolated from the shipworm Teredo bartschi, collected from Twin Cays, Belize, Central America (17°N, 88°W), as described by the protocol of Waterbury et al. (35).

Histological preparations.

Gill samples for electron microscopy were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde–1% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (pH 7.6) (60 min at room temperature) and postfixed (3 h) in 1% OsO4 in phosphate buffer. Samples were stained overnight at room temperature in 1% aqueous uranyl acetate. Following ethanol dehydration, specimens were embedded in araldite epoxy resin and heat polymerized (60°C) for 3 days. Ultrathin sections were stained with lead citrate and examined using a Zeiss CEM 902 transmission electron microscope.

In preparation for in situ hybridization with oligonucleotide nucleic acid probes, gill tissue was aldehyde fixed and embedded in a removable plastic methacrylate resin according to the protocol of Warren et al. (33).

Nucleic acid extraction.

Bulk nucleic acids were extracted from aseptically dissected gill (symbiont containing), ovary, eggs, and non-symbiont-containing tissues (siphons) using an IsoQuick nucleic acid extraction kit (ORCA Research Inc., Bothell, Wash.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The nucleic acid yield was quantified spectrophotometrically.

Gene sequencing.

To identify target sites for symbiont-specific PCR primers and in situ hybridization probes, the 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) of the B. setacea symbiont was fully sequenced. Nucleic acids from host gill tissue were used as the template in the PCR with eubacterial universal primers complementary to the termini of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene (27f [AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG] and 1518r [5′ AAG GAG GTG ATC CAN CCR CA 3′]) (13) according to the protocol described by Cary and Giovannoni (5). The amplification product was cloned into the plasmid vector pCR II and transformed into One Shot INVαF′ competent Escherichia coli cells according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.). The entire 16S rRNA genes from four of the clones were amplified with the same eubacterial universal primer set (27f-1518r) as described above. For initial screening, a portion of the resulting amplification product (7 μl) was digested with 2.5 U of the endonuclease HaeIII (Promega, Madison, Wis.) at 37°C for 2 h and resolved on a 3% agarose gel. Since the four clones displayed identical restriction patterns, a single clone was chosen for full sequencing.

Plasmid preparations of the clone to be sequenced were purified from overnight cultures on a Spin Miniprep Column (QIAGEN Inc., Santa Clarita, Calif.) and used directly as the template in sequencing reactions. BigDye (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.) terminator cycle sequencing reactions with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase were primed with pCRII vector-based primers (m13r [5′ GTA AAA CGA CGG CCA G 3′] and m13f [5′ CAG GAA ACA GCT ATG AC 3′]; Invitrogen) and primers specific for conserved regions of the 16S gene (338r [5′ CDC CGC TTG TGC GGG CCC 3′] and 338f [5′ ACT CCT ACG GGA GGC AGC 3′] [1], 907r [5′ CCG TCA ATT CMT TTR AGT TT 3′] and 907f [5′ AAA CTY AAA KGA ATT GAC GG 3′] [21], and 1100r [5′ GGG TTG CGC TCG TTG 3′] and 1100f [5′ YAA CGA GCG CAA CCC 3′] [21]). Sequence data were acquired from an ABI 310 DNA automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). Nucleotide sequences were edited and aligned in AutoAssembler DNA sequence assembly software and Sequence Navigator DNA sequence comparison software (Applied Biosystems, Inc.).

Phylogenetic analysis.

The 16S rDNA gene sequence of the putative B. setacea symbiont was aligned manually in the Genetic Data Environment (29) with a subset of eubacterial 16S rDNA gene sequences obtained from GenBank (2). The percent similarity between sequences was expressed as the number of different nucleotides divided by the total number of bases used in the analysis. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the PHYLIP 3.5c ed. computer software package (11). To calculate evolutionary distances, DNADIST was used with a Kimura two-parameter model, a 2.0 transition/transversion ratio, and one category of substitution rates (19). Neighbor-joining trees were constructed based on evolutionary distance data using the program NEIGHBOR (27), and parsimony trees were constructed using the program DNAPARS. Branching confidence was assessed through 100 replicate resamplings of the data using the SEQBOOT general bootstrapping tool with global rearrangements. Reference 16S rDNA sequences used in these analyses were obtained from GenBank and include accession numbers M11224, M96399, M64338, M64339, M64340, Z31658, M99446, M99445, X56578, J01695, M32020, M11223, M26636, and M59298.

Oligonucleotide probe and primer design.

Alignments of the B. setacea gill bacterium 16S rRNA sequence with those of close relatives identified several regions of variability appropriate for the development of probes specific to the teredinid symbionts and an additional probe that would distinguish the B. setacea gill symbiont strain from T. turnerae (Table 1). The 1243–1261 region (based on the E. coli numbering system) provided the variability to design a general shipworm symbiont-directed probe that would not discriminate between the two symbiont strains (ter1243r). The shipworm symbiont nucleotide sequences are identical in this probe region but differ from that of their closest relative by at least four nucleotides. An additional general shipworm symbiont primer (ter637f) was designed based on a modification (shortened length and one base substitution) of a published probe sequence (7). With two closely positioned mismatches between the two target molecules, the 613–632 region was the most suitable target site for the B. setacea-specific probe with capabilities to distinguish between the B. setacea gill bacterium and T. turnerae (bs613r and bs613f). Oligonucleotides were synthesized and high-pressure liquid chromatography purified (Operon Technologies Inc., Alameda, Calif.) for in situ hybridization (bs613r and ter1243r)- and PCR (bs613f, ter1243r, and ter637f)-based assays.

TABLE 1.

Teredinid symbiont probe sequences and targets

| Probe name | Probe sequence (5′–3′) | Probe specificity |

|---|---|---|

| bs613r | AGT TCC AAG GTT GAG CCC TG | B. setacea gill bacterium |

| bs613f | CAG GGC TCA ACC TTG GAA CT | B. setacea gill bacterium |

| ter1243r | GGC AAC CCT TTG TAC AGC C | Teredinid symbiont |

| ter637f | TTA GAA CTG GGT AAC TAG AG | Teredinid symbiont |

The specificity of the bs613r probe was tested by dot blot hybridization according to the protocol of Cary et al. (3). Briefly, denatured plasmids of the 16S gene clones (150 ng) from the putative B. setacea gill symbiont and T. turnerae TBTC were blotted onto positively charged membranes. Hybridizations with digoxigenin-11-dUTP (DIG)-tailed bs613r and bacterial universal probes (eub338r) were performed at 40°C for 12 h in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer (Genius Systems; Boehringer Mannheim Corp.). Unbound probe was removed through a series of stringency washes (2× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate] and 0.2× SSC, 50 min per wash) at 46°C. Stringency washes and colorimetric detection were in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim Corp.). Positive control dot blot hybridizations with eubacterial universal probe 338r were performed using the same protocol to demonstrate the accessibility of the DNA templates for probing.

Clone library screening.

To assess the possible diversity of bacteria within a single shipworm host, a second clone library of 16S amplicons from B. setacea gill DNA extract was constructed for restriction digest screening. Based on sequence data, a diagnostic region of the 16S gene (E. coli numbering 637 to 1243) was identified that would distinguish the symbiont T. turnerae from the B. setacea gill bacterium by a simple restriction analysis. Primers flanking this region (ter637f and ter1243r) were synthesized and used to amplify each of the 48 clones. Amplification reaction conditions were identical to those stated above but with an annealing temperature of 61°C. Amplification products were digested with the endonuclease HaeIII as described above. To verify that identical cut patterns reflected actual gene sequence identity, five clones were sequenced with the universal primer 907r (21).

In situ hybridizations.

To determine the specificity of the teredinid symbiont probes (bs613r and ter1243r) in situ, hybridization reactions were conducted on sections of fixed gill tissue from the shipworm host. Oligonucleotide probes ter1243r, bs613r, eub338r, and 11f were labeled with DIG as described above. The eub338r eubacterial universal probe was used as a positive control to demonstrate the presence and accessibility of the bacterial target. A nonhomologous probe specific for blue mussel collagenous proteins, 11f (5′ AAG CTT TCG CAA CGG AAG AC 3′) (K. Coyne, unpublished data), functioned as a control for nonspecific binding. A no-probe control treatment was included in all experiments to ensure that hybrids were not an artifact of the reaction conditions.

The tissue sectioning and preparation for in situ hybridization were by the methacrylate embedding, acetone de-embedding technique of Warren et al. (33). Each hybridization experiment consisted of five individual treatments with either bs613r, ter1243r, eub338r, 11f, or a no-probe control. A total of 25 to 50 sections from three different embedded tissue samples were represented in each treatment. Prehybridizations were performed in hybridization buffer [2× SSC, 1× Denhardt's solution, 0.5 mg of sheared herring sperm DNA per ml, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg of poly(A) per ml, and 0.1% Tween 20] for 60 min at 40°C. Following the prehybridization, the DIG-labeled probes were added to a final concentration of 1 ng/μl. Hybridization proceeded for 7 to 10 h at 40°C in a humid glass chamber. Posthybridization washes were conducted for 50 min each in 300 ml of wash 1 (2× SSC, 0.1% Tween 20) and 300 ml of wash 2 (0.2× SSC, 0.1% Tween 20).

Detection of hybrids was accomplished using Enzyme-Labeled Fluorescence (ELF) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) by a protocol modified from that of the manufacturer. Following posthybridization washes, slides were washed twice (5 min each) in 1× wash buffer and then treated with blocking reagent (30 min) in a humid chamber. The alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibody (1:500 in blocking reagent) was applied to sections and incubated (2 h) in a humid chamber. Following three washes (5 min each) in 1× wash buffer, sections were incubated (50 min) in freshly prepared substrate working solution. Sections were washed (5 min) in 1× wash buffer and postfixed (15 min; 2% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline with 20 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml) for signal stabilization. After counterstaining (5 min) with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (1 μg/ml), slides were mounted in ELF mounting medium and visualized on a Zeiss LSM 410 inverted scanning confocal laser microscope equipped with a UV laser. The fluorescence produced by ELF was visualized using a 590-nm long-pass emission filter. DAPI fluorescence was visualized with a 480- to 520-nm band-pass emission filter and assigned a red pseudocolor.

PCR detection of symbiont genes.

The B. setacea gill bacterium-specific primer set (bs613f-ter1243r) was used in a series of PCR experiments to resolve the presence or absence of symbiont 16S rDNA in nucleic acid extracts from B. setacea gill, ovary, and recently spawned eggs. Symbiont-containing gill extract was included as a positive control, as was the plasmid containing the cloned 16S gene amplicon from B. setacea gill. Nucleic acid extracts were also amplified with primers specific for the termini of the eukaryotic small-subunit 18S rRNA gene (EukA, 5′ AAC CTG GTT GAT CCT GCC AGT 3′; EukB, 5′GAT CCW TCT GCA GGT TCA CCT AC 3′) (23) as a positive control. PCR mixtures consisted of 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and dGTP) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), 2.0 μM MgCl2, 1× reaction buffer, 1 μM concentrations of each primer, 25 ng of purified DNA extract as the template, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega) in a final volume of 25 μl. For the bs613f-ter1243r primer set, cycling conditions consisted of 35 cycles each of denaturation at 94°C (1.5 min), annealing at 65°C (2 min), and extensions at 72°C (2 min), with a final extension time of 7 min. Cycling conditions for the 18S rRNA gene primer set were as described above, with the substitution of a 55°C annealing temperature. The authenticity of amplification products was verified by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis with the restriction enzyme HaeIII (as described above) and by DNA sequencing.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The full 16S rDNA sequence of the B. setacea gill symbiont has been deposited in GenBank under accession number AF102866.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to determine the mode by which bacterial symbionts are acquired by successive generations of the shipworm B. setacea. In a previous study, four shipworm species representing three different genera which were collected from varied ocean regions (California, North Carolina, Australia, and Massachusetts) were reported to harbor a phylogenetically common symbiont strain, T. turnerae (7). It was suggested by those authors that it was likely that most shipworm species would harbor the same symbiont. However, the teredinid B. setacea, a primary wood borer in the Pacific Northwest of the United States, was not included in these analyses. Our approach in this study was to systematically characterize the symbiont of B. setacea to develop molecularly based methodologies for the detection of the symbiont in the host reproductive tissues.

Clone library.

Bacterial 16S rRNA genes were successfully amplified from B. setacea gill nucleic acid extract using universal eubacterium-specific primers (13). The amplification product was cloned, and a library consisting of 48 clones was constructed. All of the clones in the library amplified with the teredinid symbiont primer set (ter637f-ter1243r), producing a predictable ∼648-bp product. The digestion of the PCR products from each of the clones with the restriction enzyme HaeIII yielded identical cut patterns. The cut pattern diagnostic for T. turnerae was not represented by any of the clones in the library, suggesting that T. turnerae was not present within B. setacea gill tissue (Fig. 1). Furthermore, five of these clones were sequenced with the 907r primer, yielding identical nucleotide sequences. The results of the clone library screening suggested that the B. setacea gill was colonized by a single microorganism that was distinct from T. turnerae.

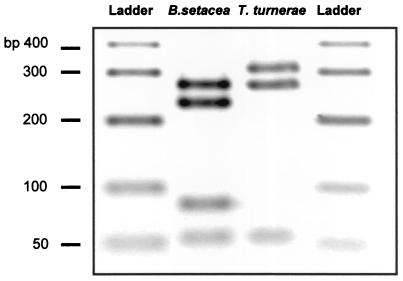

FIG. 1.

RFLP comparison of bs613f-ter1243r PCR amplicons from B. setacea gill and T. turnerae nucleic acid extracts. Amplification products were digested with the endonuclease HaeIII. The T. turnerae amplification product does not share the third restriction site with the B. setacea amplification product, thus providing RFLP discrimination of the two bacterial 16S rRNA templates.

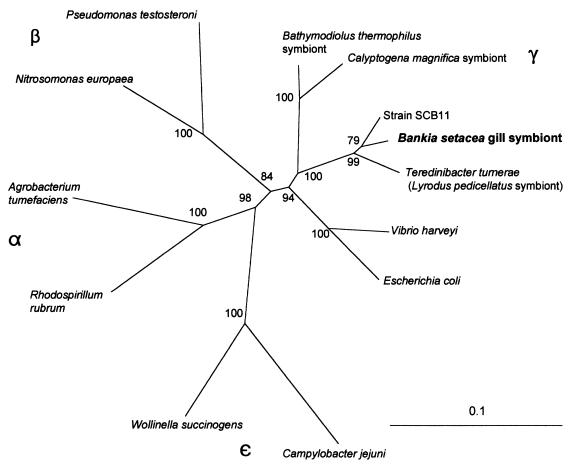

A single 16S rDNA clone was bidirectionally sequenced and aligned with 16S rRNA gene sequences of other representative prokaryotes. Base positions which were of indeterminate identity, insertions and deletions, alignment gaps, and sequence regions of ambiguity were excluded, resulting in a total of 978 of the 1,500 total nucleotide positions for analysis. Phylogenetic trees based on neighbor-joining and parsimony analyses consistently placed the B. setacea gill bacterium among the gamma subdivision of the Proteobacteria (30, 36), closely related yet genetically distinct (95.5% similarity) to T. turnerae (Fig. 2). Evolutionary placement of the teredinid gill symbionts in the gamma subdivision of the Proteobacteria is consistent with previous phylogenetic classifications of several gill symbionts from the bivalve families Lucinidae, Solemyidae, and Vesicomyidae (4, 8, 10, 20). The B. setacea gill bacterium is 96.3% similar to bacterial strain SCB11, an abundant free-living bacterium cultured from seawater along the coast of La Jolla, Calif. (26). Ninety-nine of the 100 replicate resamplings of the data placed the B. setacea gill symbiont within the distinct clade comprised of T. turnerae and strain SCB11 (GenBank accession number Z31658). This phylogenetic topology was supported by both distance (Fig. 2) and parsimony (not shown) analyses. Both trees identified the strong grouping of the teredinid symbionts within a clade among other bacteria in the gamma subdivision of the Proteobacteria.

FIG. 2.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of the evolutionary relatedness of the B. setacea gill symbiont to other members of the Proteobacteria. Analyses are based on 978 bp of aligned nucleotide sequence. Numerical values accompanying branch nodes reflect branching confidence based on a bootstrap of 100 replicate resamplings of the data. The horizontal scale bar corresponds to 0.1 substitutions per nucleotide position.

Detection and localization of the B. setacea symbiont.

Oligodeoxynucleotide probes were designed based on comparative 16S rDNA sequence alignments of the B. setacea gill bacterium with T. turnerae and close relatives. The specificities of the 19-oligomer B. setacea gill bacterium probe (bs613r) and 20-oligomer teredinid symbiont-directed probe (ter1243r) were tested by solid-support dot blot hybridization. Experiments performed on the cloned 16S rRNA gene from the B. setacea gill bacterium and T. turnerae TBTC verified that bs613r bound exclusively to the target of interest and not to the T. turnerae target (data not shown). The experiments demonstrated that the positive control probe eub338r bound with both templates, confirming the accessibility of the DNAs for probing.

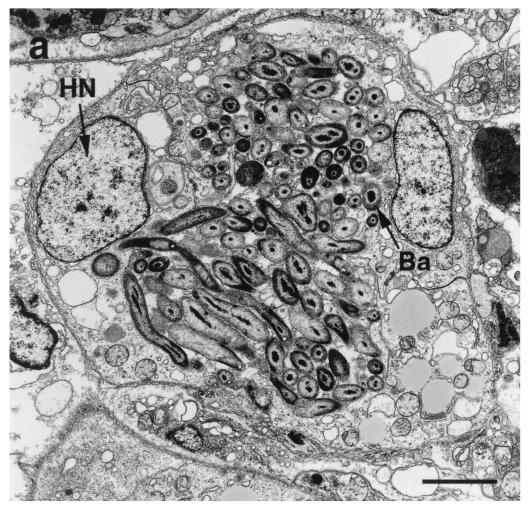

In situ hybridization experiments were essential to demonstrate that the newly designed B. setacea symbiont probe (bs613r) was specific for microbes residing within the host gill and not as external contaminants. Initial electron microscopic analysis of the gill tissue localized the bacterial symbionts to an intracellular location in host cells comprising distinct structures lining the interlamellar junction of the B. setacea gill (Fig. 3a). The eubacterial-universal control probe eub338r hybridized with bacteria within the gill (Fig. 3b). Both teredinid-directed probes (ter1243r and bs613r) hybridized in situ with the bacterial symbionts residing in the shipworm Gland of Deshayes (Fig. 3c and d). Both of the probes hybridized with target nucleic acids located in clusters (symbiont-containing vesicles, or bacteriocytes) along the gill lamellae but not with non-symbiont-containing tissue. As was expected, the nonhomologous probe control (11f) failed to form detectable hybrids (Fig. 3e). A no-probe control treatment demonstrated that the hybrid signal was not an artifact of the reaction conditions (data not shown). These experiments corroborate previous localization of teredinid symbionts within the bacteriocytes lining the gill interlamellar junctions of the other teredinid species (7).

FIG. 3.

Symbiont localization in gills through transmission electron microscopy (a) and in situ hybridizations with DIG-labeled oligonucleotide probes (b to e). In the transmission electron micrograph of a portion of a gill filament, the bacteria (Ba) are localized between two host nuclei (HN). Epifluorescent micrographs (b to e) illustrate gill lamellae containing bacteria interspersed with shipworm host cells indicated by the stained nuclei (Nu). Sp, intralamellar space. Sections were incubated with oligonucleotide probes, and hybrids were visualized with ELF-97 fluorescence (yellow). Sections were counterstained with DAPI and assigned a red pseudocolor. (b) Positive control bacterial universal probe eub338r. (c) Teredinid symbiont probe ter1243r. (d) B. setacea symbiont probe bs613r. (e) Negative control nonhomologous probe 11f. Bars: panel a, 2 μm; panels b to e, 250 μm.

The hybrids formed by the binding of the bs613r probe appear to represent only a fraction of those hybrids formed between the ter1243r probe and the rRNA target. The differential binding of the two symbiont probes with the bacteria within the host gill may have been caused by varied hybridization efficiencies of probes targeting different regions along the rRNA molecule (18). Alternatively, a consortium of closely related bacterial symbionts may co-occur within the shipworm host gill that accepts only the general teredinid probe. However, this does not agree with results from the clone library constructed of 16S rRNA genes within the shipworm host gill, which indicate that the B. setacea gill is populated by a single microorganism.

Evidence for vertical transmission.

The results of the in situ hybridizations demonstrated that the B. setacea gill symbiont identified through cloning and 16S rDNA sequencing efforts resides within the B. setacea host gill. Because both the bs613r and ter1243r probes hybridized with the bacterial rRNA located within bacteriocytes in the host gill, it was concluded that these probes could be used as primers in the PCR to detect the symbiont target genes within the B. setacea gill and other tissues. A reverse complement of the bs613r probe (bs613f) was used in conjunction with the teredinid symbiont-specific probe (ter1243r) as a primer in the PCR to detect the presence of symbiont rDNA within host tissues. Both B. setacea and T. turnerae TBTC DNA templates were found to amplify with these primers. This cross-reactivity, however, was not a concern, since these two amplification products could be easily distinguished based on HaeIII RFLP analysis (Fig. 1). This was also the case with the closely related SCB11 bacterial strain. The published 16S rDNA gene sequence of SCB11 indicates the absence of an HaeIII recognition site at bp 846 (E. coli numbering), where a site exists in the 16S rDNA gene sequence of the gill bacterium in B. setacea. If the SCB11 template were to amplify with the B. setacea symbiont-directed primers, it could also be differentiated from the symbiotic template based on HaeIII digestion.

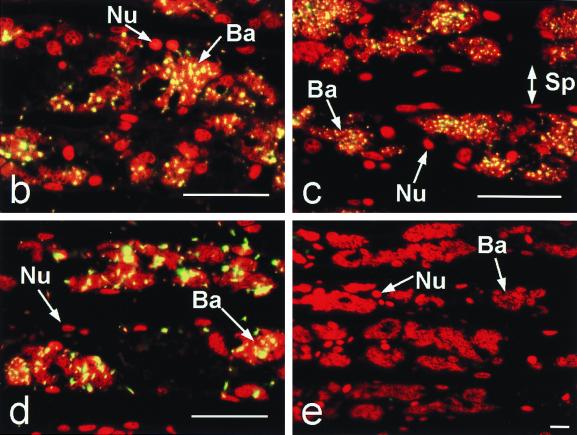

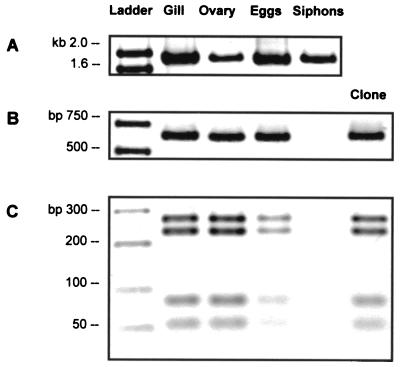

Conceivably, only a single bacterium would be necessary to initiate the symbiosis in a developing host larva. Detection at this level of resolution is not yet possible with conventional biochemical approaches. Nucleic acid amplification technologies based on the PCR provide the sensitivity and reproducibility necessary to identify the presence of extremely low copy numbers of a particular target sequence. This approach has been very successful in studies of symbiont transmission in other bivalve-bacterium associations (4, 5, 8, 9, 20). Bulk nucleic acids extracted and purified from gills, ovaries, eggs, and non-symbiont-containing siphon tissue were used as templates in PCR amplifications using the eukaryotic primer set (EukA-EukB) and the B. setacea symbiont primer set (bs613r-ter1243r). PCR amplification of the eukaryotic 18S ribosomal gene resulted in a band of the appropriate size (∼1,800 bp) in all extracts, verifying the accessibility of the nucleic acid extracts for PCR amplification. The teredinid primer set clearly amplified its specific rDNA target (648 bp) in DNA extracts from gills, ovaries, and eggs. Amplification did not occur in the non-symbiont-containing siphon tissue which served as the negative control (Fig. 4). All positive amplifications were screened by RFLP and sequence analysis. PCR products from gill, ovary, and egg nucleic acid extracts, as well as the product amplified from the B. setacea 16S rRNA gene clone used in the original sequence analysis, all demonstrated identical restriction patterns. Direct sequencing of each purified PCR product further verified that the sequence of the symbiont-specific target amplified from the ovarial tissue and eggs was identical to the 16S rRNA gene sequence obtained from the symbiont-containing gill tissue. It was therefore concluded that the B. setacea gill symbiont was present in the ovary tissue and freshly spawned eggs, suggesting that this bacterium was transmitted vertically. While the presence of the DNA in the eggs and ovary as detected through PCR is highly suggestive of a vertical transmission strategy (4, 5, 8, 9, 20), verification that the bacteria are indeed viable and capable of initiating the symbiosis would require cultivation experiments which were beyond the scope of this investigation.

FIG. 4.

PCR amplification of gill, ovary, egg, and siphon nucleic acid extracts with two primer sets. (A) Positive amplification with 18S ribosomal gene primers visualized on a 1% SeaKem LE agarose gel. (B) PCR detection of symbiont rDNA with the bs613f-ter1243r primer set in shipworm gill (positive control), ovary, egg, siphon extracts (negative control), and the cloned 16S rDNA from B. setacea gill. (C) HaeIII digestion of bs613f-ter1243r PCR products. RFLP patterns from ovary and egg PCR products correspond to those from shipworm gill control tissue and the cloned 16S rDNA from the B. setacea gill, thus verifying the authenticity of PCR amplifications. No signal was detected in the siphon tissue (negative control). Reaction products were visualized on a 3% NuSieve GTG-SeaKem (3:1) gel.

Both the detection of the symbiont 16S rRNA gene within gonads and eggs of B. setacea and this first report of symbiont diversity among host species in the family Teredinidae strongly support the notion that symbiont acquisition in this shipworm species occurs vertically. Furthermore, the strong evolutionary grouping of the Teredinidae symbionts suggests a relatively recent common ancestry, perhaps with subtle genetic distinctions arising after the vertically transmitted symbiont populations became isolated from the genetic pool. B. setacea is an invertebrate host with planktotrophic larvae and a specialized lifestyle relying on symbiont-derived enzymes for nutrition. It is therefore not surprising that the host shipworm has evolved a strategy to package its young with this vital symbiotic microbe, ensuring continuity of the association in the progeny. Equipped with the symbiont required for survival, this strategy eliminates the need for larvae to encounter the symbiont at another point during the recruitment process. Vertical transmission provides the means for the offspring to settle freely in uncolonized wood and may also be favorable to the shipworm parent's success by eliminating competition for wood between parent and progeny.

Conclusions and implications.

Although the present study indicates that the teredinid B. setacea harbors a unique symbiont that is transmitted vertically, previous work has shown that four different shipworm species representing different genera share a common symbiont strain (7). Clearly, the symbiotic relationships between teredinids and their bacterial counterparts are not as constrained as in other systems (8, 9, 20). This scenario is similar to another highly specific symbiosis between a single bacterial species (Vibrio fischeri) and several sepiolid squid host species (24). Given the great diversity of life history patterns, reproductive strategies, morphologies, and geographical distributions of species within the Teredinidae, varied strategies of symbiont acquisition among the species would not be surprising. Conceivably, teredinids may have the ability to acquire symbionts both vertically and from the environment. The diverse nature of the Teredinidae makes this family a model system for examining the mechanism of symbiont acquisition associated with clearly different life histories between closely related organisms.

The basis of this research is the hypothesis that the symbionts represent the weak link in the teredinid host life strategy and may be targeted in attempts to curb biodegradation of marine timber. Research is under way to characterize shipworm antifoulants derived from tropical wood species that demonstrate superior resistance to wood borers. Once characterized, these antifoulant compounds will be tested for their ability to inhibit the growth of the teredinid bacterial symbionts and thereby prevent teredinids from digesting the cellulose of treated wood.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants to S.C.C. from The Delaware Sea Grant Program (R/B 32) and the Smithsonian Institute Caribbean Coral Reef Ecosystem (CCRE) program.

We are indebted to K. Rützler and I. Feller for providing the unique opportunity to collect shipworm specimens in Belize. We thank R. Turner for encouragement and assistance early in this project. We thank K. Czymmek for technical assistance with confocal microscopy and R. Rhatigan for shipworm collection in Oregon. We also thank B. Campbell, K. Coyne, and A. Hacker for critically reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R I, Binder B J, Olsen R J, Chisholm S W, Devereux R, Stahl D A. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1919–1925. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1919-1925.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson D A, Boguski M S, Lipman D J, Ostell J, Ouelloette B F. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cary S C, Cottrell M T, Stein J L, Camacho F, Desbruyéres D. Molecular identification and localization of filamentous symbiotic bacteria associated with the hydrothermal vent annelid Alvinella pompejana. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1124–1130. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1124-1130.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cary S C. Vertical transmission of a chemoautotrophic symbiont in the protobranch bivalve, Solemya reidi. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994;3:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cary S C, Giovannoni S J. Transovarial inheritance of endosymbiotic bacteria in clams inhabiting deep-sea hydrothermal vents and cold seeps. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5695–5699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cary S C, Warren W, Anderson E, Giovannoni S J. Identification and localization of bacterial endosymbionts in hydrothermal vent taxa with species-specific PCR amplification and in situ hybridization techniques. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1993;2:51–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Distel D L, DeLong E F, Waterbury J B. Phylogenetic characterization and in situ localization of the bacterial symbiont of shipworms (Teredinidae: Bivalvia) by using 16S rRNA sequence analysis and oligodeoxynucleotide probe hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2376–2382. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.8.2376-2382.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Distel D L, Lane D J, Olsen G J, Giovannoni S J, Pace B, Pace N R, Stahl D A, Felbeck H. Sulfur-oxidizing bacterial endosymbionts: analysis of phylogeny and specificity by 16S rRNA sequences. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2506–2510. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2506-2510.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durand P, Gros O, Frenkiel L, Prieur D. Phylogenetic characterization of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria endosymbionts in three tropical Lucinidae by using 16S rDNA sequence. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1996;5:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisen J A, Smith S W, Cavanaugh C M. Phylogenetic relationships of chemoautotrophic bacterial symbionts of Solemya velum Say (Mollusca: Bivalvia) determined by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3416–3421. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3416-3421.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package), 3.5c ed. Seattle: Department of Genetics, University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gara R I, Greulich F E. Shipworm (Bankia setacea) activity within the Port of Everett and the Snohomish River Estuary: defining the problem. For Chron. 1995;71:186–191. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giovannoni S J. The polymerase chain reaction. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.; 1991. pp. 177–203. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene R V. A novel, symbiotic bacterium isolated from marine shipworm secretes proteolytic activity. Curr Microbiol. 1989;19:353–356. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greene R V, Griffin H L, Freer S N. Purification and characterization of an extracellular endoglucanase from the marine shipworm bacterium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;1:334–341. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greene R V, Freer S N. Growth characteristics of a novel nitrogen-fixing cellulolytic bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:982–986. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.5.982-986.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gros O, De Wulf-Durand P, Frenkiel L, Mouëza M. Putative environmental transmission of sulfur-oxidizing bacterial symbionts in tropical lucinid bivalves inhabiting various environments. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;160:257–262. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill W E, Weller J, Gluick T, Merryman C, Marconi R T, Tassanakajohn A, Tapprich W E. Probing ribosome structure and function by using short complementary DNA oligomers. In: Hill W E, Dahlberg A, Garrett R A, Moore P B, Schlessinger D, Warner J R, editors. The ribosome. Washington, D.C.: American Society of Microbiology; 1990. pp. 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura M. A simple model for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krueger D M, Cavanaugh C M. Phylogenetic diversity of bacterial symbionts of Solemya hosts based on comparative sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:91–98. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.91-98.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lane D J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackenbrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.; 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin M M. Cellulose digestion in insects. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1983;75:313–324. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medlin L, Elwood H J, Stickel S, Sogin M L. The characterization of enzymatically amplified eukaryotic 16S-like rRNA-coding regions. Gene. 1988;71:491–499. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishiguchi M K, Ruby E G, McFall-Ngai M J. Competitive dominance among strains of luminous bacteria provides an unusual form of evidence for parallel evolution in Sepiolid squid-vibrio symbioses. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3209–3213. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3209-3213.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popham J D, Dickson M R. Bacterial associations in the teredo Bankia australis (Lamellibranchia, Mollusca) Mar Biol. 1973;19:338–340. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rehnstam A-S, Bäckman S, Smith D C, Azam F, Hagström Å. Blooms of sequence-specific culturable bacteria in the sea. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1993;102:161–166. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sigerfoos C P. Natural history, organization and late development of the Teredinidae or shipworms. Bull Bur Fish. 1908;37:191–231. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith S W, Overbeek R, Olsen G, Woese C, Gillevet P M, Gilbert W. Genetic data environment and the Harvard genome database, genome mapping and sequencing. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stackebrandt E, Murray R G E, Trüper H G. Proteobacteria classi nov., a name for the phylogenetic taxon that includes the purple bacteria and their relatives. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;40:213–216. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner R D. Collecting shipworms. 1947. Limnological Society of America, Special Publication no. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner R D. A survey and illustrated catalogue of the Teredinidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia). Cambridge, Mass: The Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren K C, Coyne K J, Waite J H, Cary S C. Use of methacrylate de-embedding protocols for in situ hybridizations on semi-thin sections with multiple detection strategies. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:149–155. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watanabe H, Noda H, Tokuda G, Lo N. A cellulase gene of termite origin. Nature. 1998;394:330–331. doi: 10.1038/28527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waterbury J B, Calloway C B, Turner R D. A cellulolytic nitrogen-fixing bacterium cultured from the Gland of Deshayes in shipworms (Bivalvia: Teredinidae) Science. 1983;221:1401–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.221.4618.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woese C R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]