Abstract

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Integrated use of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), a locoregional inducer of immunogenic cell death, with ICI has not been formally assessed for safety and efficacy outcomes.

Methods

From a retrospective multicenter dataset of 323 patients treated with ICI, we identified 31 patients who underwent >1 TACE 60 days before or concurrently, with nivolumab at a single center. We derived a propensity score-matched cohort of 104 patients based on Child-Pugh Score, portal vein thrombosis, extrahepatic metastasis and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) who received nivolumab monotherapy. We described overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), objective responses according to modified RECIST criteria and safety in the multimodal arm in comparison to monotherapy.

Results

Over a median follow-up of 9.3 (IQR 4.0–16.4) months, patients undergoing multimodal immunotherapy with TACE achieved a significantly longer median (95% CI) PFS of 8.8 (6.2–23.2) vs 3.7 (2.7–5.4) months (log-rank 0.15, p<0.01) in the monotherapy group. Multimodal immunotherapy with TACE demonstrated a numerically longer OS compared with ICI monotherapy with a median 35.1 (16.1–Not Evaluable) vs 16.6 (15.7–32.6) months (log-rank 0.41, p=0.12). In the multimodal treatment group, there were three (10%) grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs) attributed to immunotherapy compared with seven (6.7%) in the matched ICI monotherapy arm. There were no AEs grade 3 or higher attributed to TACE in the multimodal treatment arm. At 3 months following each TACE in the multimodal arm, there was an overall objective response rate of 84%. There were no significant changes in liver functional reserve 1 month following each TACE. Four patients undergoing multimodal treatment were successfully bridged to transplant.

Conclusions

TACE can be safely integrated with programmed cell death 1 blockade and may lead to a significant delay in tumor progression and disease downstaging in selected patients.

Keywords: Combined Modality Therapy, Liver Neoplasms, Immunomodulation

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is an effective locoregional treatment in intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and studies show it to be a potent inducer of immunogenic cell death.

Nivolumab, an antiprogrammed cell death 1 monoclonal antibody, is an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) with a favorable safety in HCC, though the majority of patients fail to achieve clinical response.

Combination therapy with ICI and TACE is safe and may synergistically improve overall and progression-free survival (PFS).

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The results of this propensity score-matched study demonstrate that sequential or concurrent multimodal treatment with TACE and ICI compared with ICI monotherapy has an acceptable safety profile and longer PFS.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE AND/OR POLICY

This study found a non-significant safety signal supporting the development of large phase III trials to prospectively assess potential synergistic clinical efficacy.

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide and is estimated to account for over 30 000 deaths in the USA in 2022.1 Despite improved survival from screening of high-risk individuals,2 extent of disease is highly variable at initial diagnosis. In advanced disease, immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy has become a novel standard of care in combination with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors.3 Use of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors as monotherapy, while not superior to standard multitargeted therapy with sorafenib as first-line systemic therapy,4 remains a therapeutic option in patients who have progressed to or are intolerant to sorafenib. The advantage of PD-1 inhibitors such as nivolumab or pembrolizumab is the favorable safety profiles compared with sorafenib while having comparable overall survival (OS)5–7 when used as a monotherapy. Considerable clinical experience has accumulated in the use of ICI in HCC. Outside clinical trials, ICIs are being increasingly integrated with currently available therapies for HCC. This includes therapeutic sequencing with locoregional treatment in patients with unresectable HCC for example, in the context of favorable radiological response to ICI, locoregional approaches may become indicated to further downstage or bridge to transplant.

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is the standard of care for intermediate stage disease2 8 and can be performed safely in those with preserved liver function (Child Pugh A or B7). Often TACE can be performed repeatedly, even in those with prior resection, and can successfully bridge or downstage patients to transplant.9–12 Studies examining the tumor microenvironment following TACE suggest it is an inducer of immunogenic cell death13 14 and, thus, there is an appealing rationale for combination of TACE with an ICI.15 In the setting of advanced disease, for example, in patients with oligometastases and intrahepatic tumor burden, concurrent ICI and TACE could facilitate stage migration.16 Preliminary studies supporting the safety and potential synergy behind sequential use of TACE with ICI have already prompted the design of prospective, randomized trials of TACE combined with ICI.

However, the outcomes of integration from ICI and TACE are not yet known, and there is a lack of data in terms of safety and efficacy of combined or sequential use of these therapies. This retrospective study leverages early experiences with combined TACE and nivolumab at a single institution within an international registry where propensity score (PS) matching with patients undergoing nivolumab monotherapy was performed to examine differences in OS, progression-free survival (PFS) and safety.

Materials and methods

Among a 323-patient international registry from 10 institutions,7 31 consecutive patients were identified between January 1, 2015, and January 1, 2020, who underwent TACE either 60 days prior to or after initiation of nivolumab at a single center. Nivolumab therapy in these patients was administered at standard dosing (3 mg/kg or 240 mg every 2 weeks, or 480 mg every 4 weeks, given the later introduction of flat-dose nivolumab administration) with a single dose held following each TACE. Patients were monitored for toxicity weekly and nivolumab held or discontinued based on the oncologist’s discretion for suspected adverse events (AEs). Patients undergoing transarterial radioembolization (TARE) were excluded. TACE procedures were performed as conventional TACE (cTACE) with emulsion-based formulations using doxorubicin and lipiodol or drug-eluting radiopaque microbeads (DEB-TACE) and performed as selective as possible while including target tumor burden. DEB-TACE is preferentially performed for large tumors and when vascular shunts are identified based on operator discretion. There were four operators with a median of 9 (range 4–10) years of experience performing chemoembolization.

Initial HCC diagnosis was made based on multiphase contrast-enhanced CT or MRI in accordance with the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines.17 All treatment decisions were made in consultation with a multidisciplinary tumor board. Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, Child-Pugh Score (CPS), albumin–bilirubin (ALBI) grade, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS), laboratory values including alpha fetoprotein (AFP), and clinical visit notes were recorded throughout patients’ nivolumab treatment course as well as demographics, underlying disease etiology, and tumor stage. Duration of nivolumab therapy and relative timing of TACE with respect to nivolumab initiation were collected. Response to treatment on all follow-up cross-sectional MR and CT imaging was determined using modified RECIST (mRECIST) criteria.18 TACE imaging response was typically examined at 1, 3, and 6 months. Clinical events including nivolumab treatment termination, last follow-up, transplant, and death were collected. Death was assigned for patients known to enter hospice and when no other information on death could be found (ie, online obituary or Social Security Death Database).

PS matching of patients undergoing combination nivolumab and TACE was performed using a multinational, multi-institutional registry of patients with HCC receiving nivolumab without concurrent locoregional treatment. PSs were based on portal vein thrombosis (PVT), extrahepatic metastasis (EHM), AFP and CPS at baseline using SAS software PSMATCH procedure.

The outcome measure OS was made according to clinical, laboratory, and imaging follow-up. Additional outcome measures included PFS, AEs attributed to nivolumab therapy, or TACE according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V.5, liver function test changes (alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TB), and albumin (AL)) following TACE, and treatment response. For significance testing of continuous and binary measures between patient groups, Mann-Whitney U test and Fischer’s exact t-test were used, respectively. Differences from baseline to follow-up of continuous measures were analyzed using Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank testing. OS and PFS differences between multimodal and control cohorts were performed using Kaplan-Meier log-rank tests with 95% CIs with censorship of patients transplanted or lost to follow-up. A forest plot of univariate subgroup analyses across baseline characteristics was created to examine effects of multimodal treatment compared with ICI monotherapy on PFS.

Results

Baseline characteristics

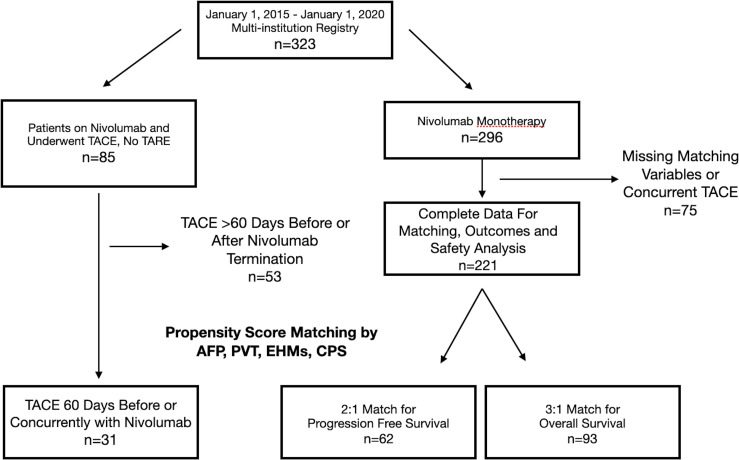

In a multinational registry of 323 patients, 31 underwent multimodal TACE and nivolumab treatment (figure 1) with a mean age of 65 years (SD 13.8 years), 27 of whom were male (87%). The most common underlying liver diseases were hepatitis B and C, comprising 29% of subjects in both groups. At the initiation of immunotherapy, the vast majority were CPS A or B, 80% and 16%, respectively. The majority of patients were classified as BCLC B or C stage, 32% and 58%, respectively. Of the 18 BCLC C patients, 33% were due to ECOG-PS, 44% due to EHM and 22% due to PVT. One patient classified as BCLC D was due to CPS C, with a MELD of 24 at nivolumab initiation. High AFP (>400 ng/mL) at baseline was noted in 16% of patients. The majority of patients had undergone previous cancer-related treatments: 42% had prior surgical resection or ablation, and 42% had prior transarterial locoregional treatment. Only 9.6% had received systemic therapy prior to immunotherapy initiation. Among these 31 patients, 61 TACE procedures were performed, 38 cTACEs and 23 DEB-TACEs, including 25 to a single segment, 23 to two to three segments and 13 to an entire lobe.

Figure 1.

Patient selection combined nivolumab and TACE and nivolumab-only cohorts. AFP, alpha fetoprotein; CPS, Child-Pugh Score; EHM, extrahepatic metastasis; PVT, portal vein thrombosis; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TARE, transarterial radioembolization.

From the same registry, there were 221 patients undergoing nivolumab monotherapy enabling 3:1 matching for OS using 93 control subjects. For PFS analysis, there were limited disease progression data in the full cohort and only 2:1 matching with 62 subjects was possible (figure 1). Of note, CPS could not be successfully used for PFS matching. Variance ratios of all variables after matching were excellent (1.0) for both PFS and OS-matched cohorts. Most, but not all, PFS-matched patients were included in the OS-matched cohort, yielding 104 unique ICI monotherapy patients that were used for either PFS or OS matching. Detailed comparisons of baseline characteristics between each PS-matched group and the multimodal group were analyzed (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics: nivolumab plus TACE versus nivolumab only

| Nivolumab and TACE (n=31) | Nivolumab only (n=93) OS-matched |

P value | Nivolumab only (n=62) PFS-matched |

P value | |

| Age (SD) | 65.0 (13.8) | 64.8 (10.4) | 0.08 | 66.4 (10.6) | 0.56 |

| Female (%) | 4 (13) | 19 (20) | 0.35 | 14 (16) | 0.68 |

| Liver disease* | |||||

| HBV (%) | 9 (29) | 36 (39) | 0.39 | 26 (27) | >0.99 |

| HCV (%) | 9 (29) | 31 (33) | 0.83 | 21 (34) | 0.81 |

| EtOH (%) | 6 (19) | 16 (17) | 0.79 | 17 (27) | 0.45 |

| NASH (%) | 5 (16) | 11 (12) | 0.54 | 9 (15) | >0.99 |

| Other (%) | 3 (9.7) | 1 (1.1) | 0.048* | 0 (0) | 0.003* |

| Child-Pugh | 0.92 | 0.10 | |||

| A | 25 (81) | 76 (82) | 39 (61) | ||

| B | 5 (16) | 15 (16) | 20 (34) | ||

| C | 1 (3.2) | 2 (2.0) | 3 (4.8) | ||

| PS ECOG | 0.19 | 0.18 | |||

| 0–1 | 31 (100) | 85 (91) | 62 (93) | ||

| >1 | 0 | 8 (8.6) | 5 (7.5) | ||

| BCLC | 0.05 | 0.006* | |||

| A | 2 (6.4) | 12 (13) | 11 (18) | ||

| B | 10 (32) | 43 (46) | 32 (52) | ||

| C | 18 (58) | 36 (39) | 17 (27) | ||

| D | 1 (3.2) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | ||

| AFP >400 (%) | 5 (16) | 16 (17) | >0.99 | 10 (16) | >0.99 |

| ALBI grade† | 1.7 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.9) | <0.001 | 2.2 (0.9) | 0.008 |

| PVT | 3 (9.7) | 8 (8.6) | >0.99 | 6 (9.7) | >0.99 |

| Metastases | 8 (26) | 24 (26) | >0.99 | 16 (26) | >0.99 |

| Max tumor diameter, median (IQR) | 2.8 (1.7–6.2) | 4.2 (2.2–7.8) | 0.25 | 4.2 (2.4–7.5) | 0.24 |

| Median number of Nodules (IQR) | 3 (2–3) | 2 (1–4) | 0.26 | 1 (1–4) | 0.04* |

| Milan criteria | 8 (26) | 25 (27) | >0.99 | 21 (34) | 0.48 |

| Prior treatments | |||||

| Surgery | 13 (42) | 31 (33) | 0.40 | 19 (31) | 0.36 |

| Ablation | 4 (13) | 29 (31) | 0.06 | 23 (37) | 0.017* |

| TACE | 12 (39) | 52 (56) | 0.10 | 38 (62) | 0.04 |

| TARE | 1 (3.2) | 18 (19) | 0.04* | 12 (19) | 0.05 |

| Sorafenib | 3 (9.7) | 57 (61) | <0.0001* | 32 (52) | <0.0001* |

| RT | 1 (3.2) | 12 (13) | 0.18 | 7 (11) | 0.26 |

*Patients in combined treatment and matched groups could have multiple liver disease etiologies.

†ALBI scores were missing in 20% of the monotherapy cohort.

AFP, alpha fetoprotein; ALBI, albumin–bilirubin; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Classification; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; EtOH, alcoholic cirrhosis; HBC, hepatitis C virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PVT, portal vein thrombosis; RT, radiation therapy; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TARE, transarterial radioembolization.

For all 104 matched subjects undergoing ICI monotherapy, the mean age was 64 years (SD 10.4 years) and 79% were male. Hepatitis B and C were the most common underlying disease etiologies, representing 34% and 38% of subjects, respectively. A majority were CPS A (72%) or B (23%), with a non-significant trend toward more CPS B subjects compared with multimodal therapy (p=0.36). Between multimodal and all matched ICI monotherapy patients, there was a similar number which met Milan’s criteria at time of immunotherapy initiation (26% vs 25%, p>0.99). The percentage of subjects in the combined control cohort with AFP producing tumors (16% vs 16%, p>0.99), PVT (10% vs 10%; p>0.99) and EHM (26% and 26%, p>0.99) were nearly identical to those having multimodal therapy as expected, given PS matching.

There was a statistically non-significant trend toward earlier stage BCLC disease in all the matched ICI monotherapy cohorts (n=104) compared with multimodal therapy (n=31), that was statistically significant when comparing the PFS control group alone (n=62) to the multimodal cohort (p=0.02)(table 1). Significantly fewer subjects in the multimodal cohort received prior sorafenib (9.7% vs 60% in the ICI monotherapy combined cohort, p<0.001). There was a more favorable baseline mean ALBI score in all matched ICI monotherapy patients (2.3 (SD 0.8) vs 1.7 (SD 0.6), p=0.0002); however, ALBI scores were missing in 20% of the monotherapy cohort. There were also trends toward smaller maximum tumor sizes (median 2.8 (IQR 1.7–6.2) cm vs 4.9 (IQR 2.4–8.4) cm, p=0.13) and greater number of nodules (median 3 (IQR 2–3) vs 2 (IQR 1–4), p=0.45) in the ICI combined cohort that were significantly greater when compared with the PFS control group (3 (IQR 2–3) vs 1 (IQR 1–4), p=0.04) (table 1). The median nivolumab duration was significantly longer in the multimodal treatment group with a median of 8.3 (IQR 3.2–18.3) vs 3.5 (IQR 1.9–8.2) (p=0.002) compared with all matched ICI monotherapy patients.

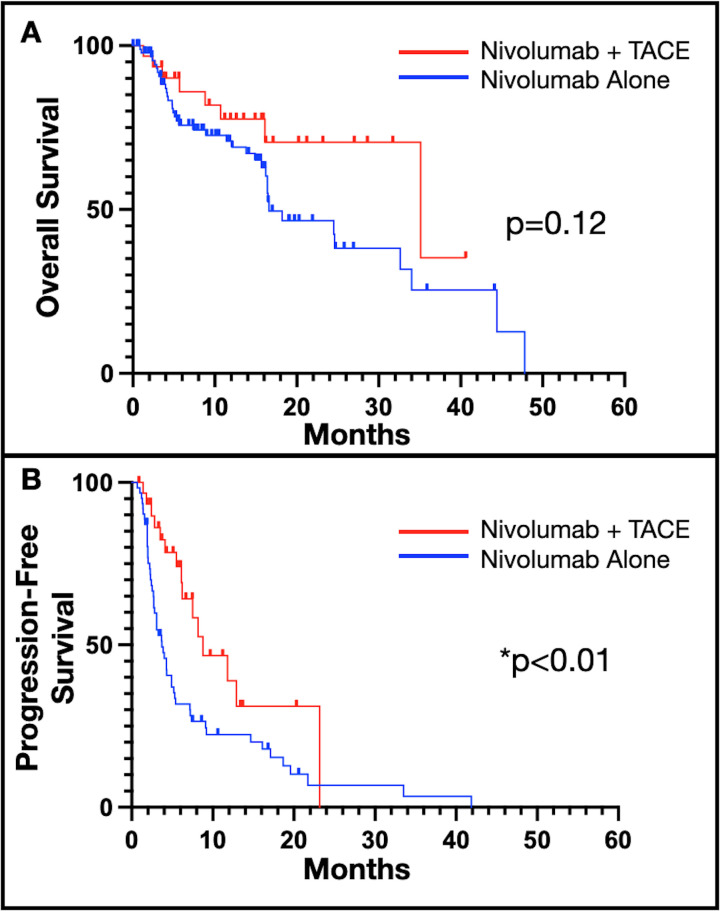

Outcomes

Median overall survival (mOS) in the multimodality treatment was 35.1 months vs 16.6 months in the OS-matched ICI monotherapy cohort, but this was not statistically significant (HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.17; log-rank 0.41; p=0.12) (figure 2A). At 12 months, there was a 69% and 78% survival rate in the ICI monotherapy and multimodal treatment groups, respectively. A significant difference was seen in median PFS between multimodal treatment and PFS-matched ICI monotherapy, 8.8 months vs 3.7 months, respectively (HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.84; log-rank 0.15; p<0.01) (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

OS and PFS combined nivolumab and TACE and nivolumab monotherapy. (A) Trend towards longer OS for multimodal treatment (n=31) versus nivolumab alone (n=93), at a median (95% CI) 35.1 (16.1–NE) compared with 16.6 (15.7–32.6) months (log-rank 0.41, p=0.12) over median 9.7 (IQR 4.1–16.4) months of follow-up, and (B) significantly longer PFS in patients undergoing multimodal treatment (n=31) versus nivolumab alone (n=62), at 8.8 (6.2–23.2) vs 3.7 (2.7–5.4) months (log-rank 0.15, p<0.01) over median 9.3 (IQR 4.0–16.4) months of follow-up. OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

In those with intermediate stage disease (BCLC B), there was a mOS of 35.1 months vs 16.6 months for multimodality treatment compared with ICI monotherapy, respectively, with an HR of 0.47 (95% CI 0.19 to 1.20, p=0.04), while for advanced stage disease (BCLC C), there was a mOS of 16.2 months vs 24.5 months with an HR of 1.23 (95% CI 0.45 to 3.30, p=0.92). For PFS, in intermediate stage disease, the median PFS was 8.8 months vs 3.1 months with an HR of 0.47 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.98, p=0.01), while in advanced disease, it was 8.2 months vs 5.2 months with an HR of 0.55 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.23, p=0.15).

A forest plot of subgroup unadjusted analysis of baseline characteristics as predictors for PFS illustrates that younger age, intermediate stage, and multifocal disease favored multimodal treatment compared with ICI monotherapy (online supplemental figure 1).

jitc-2021-004205supp001.pdf (1,022.7KB, pdf)

Safety

In the multimodal treatment group, 3 (10%) patients experienced grade 3 or higher AEs attributed to immunotherapy, compared with 7 (6.7%) in the ICI monotherapy arm (table 2). There were no AEs grade 3 or higher attributed to TACE. No patients in the multimodal group and 8.7% of patients undergoing ICI monotherapy discontinued immunotherapy due to drug-related toxicity. Abdominal pain attributed to TACE was noted in a third of multimodal treatment patients, consistent with self-resolving postembolization syndrome.

Table 2.

Treatment-related adverse events

| Nivolumab and TACE (N=31) | ||||

| Grade 1 n (%) |

Grade 2 n (%) |

Grade 3–4 n (%) |

Grade 5 n (%) |

|

| Immunotherapy attributed | ||||

| Dermatological | 5 (16) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | – |

| Diarrhea/colitis | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | – | – |

| Fatigue | 4 (13) | 1 (3.2) | – | – |

| Liver toxicity | – | 4 (13) | – | – |

| Thyroid toxicity | 1 (3.2) | 3 (9.7) | – | – |

| Polyarthritis | – | – | 1 (3.2) | – |

| Pneumonitis | – | – | – | – |

| Anorexia/weight loss | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | – | – |

| Fever | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | – | – |

| Pruritus | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | – | – |

| Other toxicities | 3 (9.7)* | 2 (6.5)† | 1 (3.2)‡ | – |

| TACE attributed | ||||

| Abdominal pain | 10 (32) | 1 (3.2) | – | – |

| Fever | 2 (6.5) | – | – | – |

| Fatigue | 3 (9.7) | – | – | – |

| Transaminitis | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | – | – |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2 (6.5) | – | – | – |

| Nivolumab alone (N=104) | ||||

| Grade 1 n (%) |

Grade 2 n (%) |

Grades 3 and 4 n (%) |

Grade 5 n (%) |

|

| Dermatological | 15 (14) | 5 (4.8) | 2 (1.9) | – |

| Diarrhea/colitis | 4 (3.8) | – | 1 (1.0) | – |

| Fatigue | 13 (13) | 2 (1.9) | – | – |

| Liver toxicity | 9 (8.7) | – | – | – |

| Thyroid toxicity | 4 (3.8) | – | – | – |

| Polyarthritis | 1 (1.0) | – | 1 (1.0) | – |

| Pneumonitis | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.9) | – | – |

| Anorexia/weight loss | 1 (1.0) | – | 1 (1.0) | – |

| Fever | – | 2 (1.9) | – | – |

| Pruritus | – | – | – | – |

| Other toxicities | 4 (3.8)§ | 3 (2.9)¶ | 1 (1.0)** | 1 (1.0)†† |

*Balanitis, hair loss, infusion reaction.

†Epigastric pain, nephritis.

‡Shortness of breath

§Pituitary, double vision, anemia, constipation

¶Hepatic coma, visual changes and constipation

**Amylase/lipase

††Myocarditis

TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

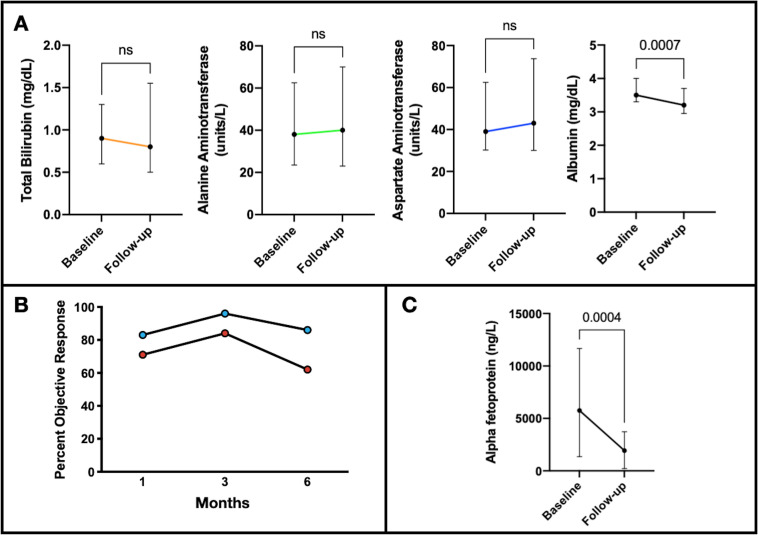

Imaging and laboratory response to TACE

There was a median of 3 (range 2–7) TACEs performed per patient in the multimodal treatment group, a median of −7.5 (IQR −23 to –22) days from nivolumab initiation to the first TACE (online supplemental table 1). Baseline imaging within 3 weeks of TACE was available in 82% (50/61) of interventions, demonstrating a median cumulative tumor size of 6.3 (IQR 3.4–12.0) cm and multifocal and bilobar disease in 86% and 47% of patients, respectively. Imaging follow-up was available at 1, 3, and 6 months following the first TACE in 75%, 78%, and 66% of patients. There was no significant change in ALT, AST, or TB) in patients with available labs at 1 month (84%, 51/61). There was a negligible, statistically significant decrease in AL of 0.2 mg/dL at 1 month after TACE with a median (IQR) follow-up AL of 3.2 (3.0–3.7) mg/dL (figure 3A). The respective target and overall mRECIST response rates were 83, 96% and 86%, and 71, 84, and 62% (figure 3B) at 1, 3 and 6 months following TACE, respectively. In those subjects with baseline AFP greater than 400 ng/dL (n=16), the median percent decrease 1 month after TACE was 31% (IQR 9.8%–70%) (figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Laboratory changes and treatment response individual TACE treatments. (A) Median changes of liver function tests from baseline to follow-up after each TACE with available 1-month follow-up labs (n=57) were 0 (IQR −0.3 to 0.6) mg/dL (p=0.40), 5 (IQR −11 to –19) units/L (p=0.21), 2 (IQR −6.8 to –14) units/L (p=0.15), and −0.2 (IQR −0.5 to −0.05) mg/dL (p<0.01), for bilirubin, ALT, AST and albumin, respectively. Treatment response according to imaging mRECIST and AFP response after TACE included (B) overall ORR of 71%, 84%, and 62, and target ORR of 83%, 96%, and 86% at 1, 3, and 6 months, respectively, after the patient’s first TACE. (C) Median change AFP from baseline to follow-up in patients with baseline AFP >400 ng/mL (n=16) was −2749 (IQR −6318 to −599) (p<0.001). AFP, alpha fetoprotein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; mRECIST, modified RECIST; ORR, objective response rate; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

jitc-2021-004205supp004.pdf (30.4KB, pdf)

Multimodal treatment course outcomes

All three subjects who discontinued nivolumab due to declining performance status or hepatic decompensation had BCLC C disease at treatment initiation—due to metastatic disease, PVT, and performance status, respectively—yet nivolumab was initially well-tolerated for 12, 12, and 31 weeks, respectively (online supplemental figure 2). No subjects discontinued nivolumab due to AEs (table 3).

Table 3.

Immunotherapy duration, clinical follow-up, immunotherapy termination

| Nivolumab+TACE (n=31) |

Nivolumab only (All matched n=104) |

||

| Number (%) or median (Range) | P value | ||

| Duration immunotherapy (months) | 8.3 (0.5–40.1) | 3.3 (0.4–35.9) | 0.009* |

| Clinical follow-up after nivolumab initiation (months) | 12.6 (1.3–40.6) | 7.5 (0.5–47.8) | 0.26 |

| Ongoing nivolumab at last follow-up | 13 (42) | 23 (22) | 0.04 |

| Discontinued treatment | 18 (58) | 80 (77) | 0.07 |

| Disease progression | 3 (9.7) | 39 (38) | 0.004* |

| Study drug toxicity | 0 (0) | 9 (8.7) | 0.12 |

| Complete Response | 1 (3.2) | 1 (1.0) | 0.41 |

| Clinical deterioration | 4 (13) | 2 (1.9) | 0.03† |

| Death | 5 (16)‡ | 3 (2.9) | 0.02† |

| Other | 5 (16)§ | 14 (13)* | 0.77 |

*Statistically significant p-value <0.01

†Statistically significant p-value <0.05

‡2/5 deaths in setting of progression of disease

§4 patients successfully bridged to transplant.

TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

jitc-2021-004205supp002.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

Of the five patients who died while on nivolumab, four were within 7 months of initiation, with the remaining patient succumbing to their disease after 108 weeks on nivolumab, and having tolerated multiple tyrosine-kinase inhibitors, stereotactic radiation treatment and TACE treatments concurrently without significant AEs.

Twelve patients were undergoing ongoing nivolumab therapy when reviewed, 4 BCLC B and 8 BCLC C, for a median duration of 105 (IQR 68–206) and 55 (15–91) weeks, respectively. Only one BCLC B and C patient each experienced an immunotherapy attributed grade 2 AE, and two BCLC C patients experienced TACE attributed grade 2 AEs. No treatment-related grade 3 or higher AEs occurred in the 12 patients with ongoing nivolumab treatment.

Discussion

HCC is a moderately immunotherapy-sensitive malignancy, with radiological response rates from PD-1 inhibition documented in <20% of patients. The favorable therapeutic index of forerunner PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have paved the way to combination therapies with other checkpoint inhibitors, VEGF-inhibitor agents and locoregional therapies to augment therapeutic benefit from immunotherapy.

This study retrospectively documents how TACE can integrate with therapeutic inhibition of the PD-1 pathway with nivolumab, aiming to formally compare the efficacy and safety of multimodal therapy with TACE and nivolumab to nivolumab monotherapy using PS matching. There was a significantly longer PFS, a trend toward greater OS, and the percentage of grade 3 or higher AEs in the multimodal treatment cohort is comparable to that reported elsewhere for ICI monotherapy.

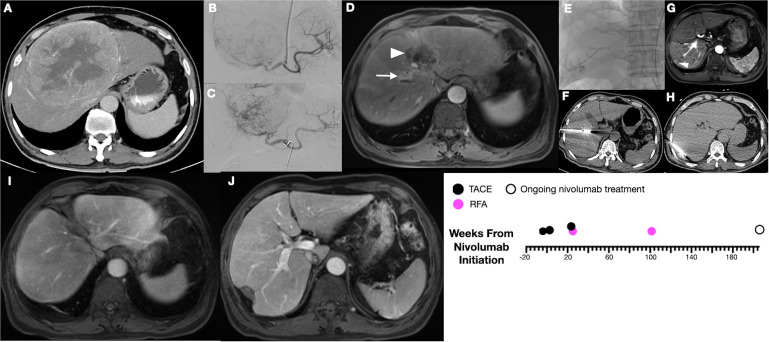

Response rates to ICI monotherapy remain modest, and the majority of patients who undergo these therapies do not achieve significant clinical response; hence, combination therapy of emerging ICIs with locoregional interventions has been of keen interest to the oncology community. Studies showing mobilization of cytotoxic CD8 T cells and diminished T regulatory cells after TACE and radiofrequency ablation suggest the possibility of a synergistic therapeutic benefit.13 14 19 The ischemic and cytotoxic damage imposed by TACE to the tumor may facilitate priming of de novo T-cell responses against tumor-associated antigens, potentially enabling an enhanced activity of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. The role of other immune-based therapies, such as allogenic natural killer cell infusions, are also being explored to as adjuvant treatment after TACE.20 Antigen priming in the tumor microenvironment following TACE may explain occasional, dramatic response to ICIs, as was seen in one multimodal subject with a duration of complete response for 206 weeks (figure 4). Unfortunately, these types of responses are rare and we lack biomarkers to predict who will benefit from ICI therapy. Immunoassays, whole exome sequencing and mutation panels from tumor and peritumorous liver tissue prior to and at multiple points during ICI are likely needed to fully elucidate the immunopotentiation of locoregional therapy prior to ICI and identify candidate radiographic and biological biomarkers.

Figure 4.

Exemplary treatment response to combined TACE and nivolumab combined therapy. Longitudinal imaging in a 57 year-old with history of hepatitis B viral infection. Initially with 15 cm segment 8/4A lesion (A), underwent two TACEs (B, C) and began nivolumab within 4 weeks. At 23 weeks from nivolumab initiation, there was complete response of this tumor (white arrowhead), but a new segment 8 lesion (white arrow) (D), subsequently treated with TACE andmicrowave ablation (E, F). New segment 7 lesions at 101 weeks underwent RFA (G, H). Currently with overall complete response at 206 weeks (I, J) and ongoing nivolumab. TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Retrospective reviews of treatment with nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and ipilimumab combined with either TACE or TARE have reported acceptable safety profiles21 22 with rates of grade 3/4 AEs comparable to or less than seen with sorafenib, and prospective trials of ICIs combined with TARE or TACE are under way.23–26 The grade 3/4 AE rate in the multimodal treatment cohort studied here was 10%, and despite being relatively higher compared with the monotherapy group (5.7%), this is lower than what was found in trials of single agent ICI in sorafenib-resistant or sorafenib-intolerant patients with advanced disease where treatment-related grade 3/4 AE rates for nivolumab (CheckMate-040)5 and pembrolizumab (KEYNOTE-224)27 were 19% and 24%, respectively. Importantly, there were no TACE-attributed grade 3/4 AEs found in the multimodal treatment group. For patients with chronic hepatitis B, there have been reports of reactivation in a setting of ICI28; however, that was not seen in any of the nine patients from the multimodal cohort who were all on nucleoside analog therapy. Longitudinal DNA titers for hepatitis B were not available in the monotherapy group.

In this small, heterogenous subset of patients from an international registry treated with multimodal therapy, most had predominantly BCLC B and C disease and would meet the selection criteria for ongoing prospective trials investigating combination ICI with TACE.29 Outcomes in the small number of BCLC B patients (n=10) were favorable to a recent prospective single-cohort study of patients with intermediate stage disease undergoing TACE combined with PD-1 inhibition (IMMUNOTACE).30 The cohort reported here had a mOS of 35.1 months with grade 3 or higher AEs of 33.3%, compared with 28.3 months and 34.7% in the IMMUNOTACE trial. This is also comparable to a prospective study in patients with intermediate and advanced diseases comparing a combination of TACE and sorafenib with TACE, sorafenib and an ICI, where the latter group achieved a mOS of 23.3 months. Impressively, the median PFS in this triple combination cohort was 16.3 months, and, perhaps, this signifies further therapeutic potential in the addition of a multikinase inhibitor along locoregional treatment and ICI. Twelve-month OS rate in the studied multimodal treatment cohort for BCLC B and C patients were 100% and 68%, respectively. Comparison with prospective trials is limited, given this study’s retrospective nature; however, these outcomes are encouraging, given a meta-analysis31 of retrospective studies of TACE for intermediate disease reported a mOS of survival of 16.5 and 12 months of 63%, and burgeoning first-line therapy atezolizumab–bevacizumab, a combination ICI and VEGF-inhibition regimen, for advanced disease has shown a comparable 12-month OS rate of 67%.3

As response rates have become key metrics for evaluating clinical efficacy of emerging ICIs, it is worth highlighting that the multimodal treatment cohort demonstrated an objective response rate at 3 months of 84% following each TACE, achieving excellent control of tumor burden. This is in line with the established role of TACE to promote PFS through high treatment response rates, even if the consequential translation of response to OS remains controversial.32 Exemplifying how multimodal treatment can achieve clinically meaningful response rates, of the eight patients meeting the Milan criteria at treatment initiation, durable disease control was attained in four patients (two BCLC B, one BCLC C, and one BCLC D), allowing successful bridge to transplant. These bridged patients all underwent neoadjuvant TACE prior to nivolumab initiation, then subsequent TACE (median 2, range 0–2) for new or growing existing lesions and provided a median bridge duration of 14 months. While TARE has become a preferred modality for bridging to transplant at the institution performing multimodal treatment in this study,33 it can often be contraindicated due to small liver size following prior resections.

There are limitations of this study, including imperfect matching for the PFS where only 2:1 matching was possible and CPS could not be used. The multimodal cohort is a small, heterogeneous sample of patients, and collective outcomes must be extrapolated to patients with specific disease stages cautiously. Additionally, there were significantly more subjects previously treated with sorafenib in the ICI monotherapy cohort compared with multimodal therapy. As with any retrospective investigation, another major limitation is selection bias. The multimodal group represents treatment decision-making by a multidisciplinary tumor board accustomed to high-volume use of locoregional therapies, and operator procedural experience may exceed that of other centers. Additionally, the multimodal patients were commonly referred directly by hepatologists at a transplant hospital, whereas patients presenting to dedicated cancer centers without transplant services, as partially represented in the monotherapy group, may have longer times from diagnosis to initial ICI treatment.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a favorable safety profile when TACE is integrated into PD-1 blockade and can lead to a significantly increased PFS and disease downstaging in select patients.

jitc-2021-004205supp003.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the biostatistics support of John Doucette with the Department of Environmental Medicine and Public Health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Footnotes

Twitter: @uqbakhan, @thenasheffect

Contributors: BM, TUM, DJP and EK conceived and designed the study, participated in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of work or revising it critically for important intellectual content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of work. ND and MC participated in acquisition and analysis of data. AD'A, RP, AF, VB, MK, NN, AS, HH, AOK, YIA, AP, Y-HH, UK, MM, ARN, DB, MSu, CA, IS and MSc participated in analysis and interpretation of data, revising it critically important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. BM is responsible for the overall content as the guarantor for this work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: EK is a consultant for Koninklijke Philips Electronics (Amsterdam, Netherlands) and is on the advisory board for Onyx Pharmaceuticals (South San Francisco, California) and the speaker’s bureau for BTG International (West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania). RP is a consultant for Sirtex Medical (North Sydney, Australia) and Arstasis (Fremont, California). AF is a consultant for Surefire Medical (Westminster, Colorado) and Terumo Medical Corporation (Somerset, New Jersey) and is on the advisory board for Terumo Medical Corporation. DB is a consultant for Bayer Healthcare, Boston Scientific and Shionogi and lecturer for Falk Foundation. YH has research grants from Gilead Sciences and Bristol Myers Squibb and honoraria from Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Ipsen and Roche, and serves as advisor for Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Ipsen, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Roche. AS has research grants from AstraZeneca, Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, Exelixis and Clovis and receives advisory board/consultant fees from AstraZeneca, Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, Exelixis and Pfizer. AP is on the medical advisory board for Exelixis, Eisai, AstraZeneca and Genentech, safety review committee for Replimune and on the speaking bureau for Simply Speaking Hepatitis. MK is a consultant for Eisai, Ono Pharmaceutical Co, Merck Sharpe & Dohme Corp, Bristol Meyer Squibb and Roche; research contracts grants from Ono Pharmaceutical Co; grants from Eisai, Takeda, Otsuka, Taiho, EQ pharma, Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Chugai, Ono Pharmaceutical; and is an honorary lecturer for Eisai, Bayer, Merck Sharpe & Dohme Corp, Bristol Meyer Squibb, EA Pharma, Eli Lilly and Chugai. TUM has served as an advisor and/or data-safety boards for Regeneron, Boehringer Ingelheim, Atara, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Chimeric Therapeutics, Riboscience, Celldex and Rockefeller University, and has research grants from Regeneron, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Boehringer Ingelheim. None of the other authors have identified a conflict of interest.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board, and the need for informed consent was waived, given the retrospective, observational nature of this study.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer statistics center. Available: http://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org [Accessed 23 Mar 2022].

- 2.Lo C-M, Ngan H, Tso W-K, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2002;35:1164–71. 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1894–905. 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, et al. CheckMate 459: a randomized, multi-center phase III study of nivolumab (NIVO) vs sorafenib (SOR) as first-line (1L) treatment in patients (PTS) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC). Annals of Oncology 2019;30:v874–5. 10.1093/annonc/mdz394.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 2017;389:2492–502. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sangro B, Park J, Finn R, et al. LBA-3 CheckMate 459: long-term (minimum follow-up 33.6 months) survival outcomes with nivolumab versus sorafenib as first-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2020;31:S241–2. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fessas P, Kaseb A, Wang Y, et al. Post-registration experience of nivolumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: an international study. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e001033. 10.1136/jitc-2020-001033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;359:1734–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouchard-Fortier A, Lapointe R, Perreault P, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma as a bridge to liver transplantation: a retrospective study. Int J Hepatol 2011;2011:1–7. 10.4061/2011/974514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nugent FW, Qamar A, Stuart KE, et al. A randomized phase II study of individualized stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) versus transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) with DEBDOX beads as a bridge to transplant in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). JCO 2017;35:223. 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.4_suppl.223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu C-Y, Ou H-Y, Weng C-C, et al. Drug-Eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization as bridge therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma before living-donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2016;48:1045–8. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.12.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzaferro V, Citterio D, Bhoori S, et al. Liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma after tumour downstaging (XXL): a randomised, controlled, phase 2B/3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:947–56. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30224-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffy AG, Ulahannan SV, Makorova-Rusher O, et al. Tremelimumab in combination with ablation in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017;66:545–51. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinato DJ, Murray SM, Forner A, et al. Trans-arterial chemoembolization as a loco-regional inducer of immunogenic cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9:e003311. 10.1136/jitc-2021-003311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llovet JM, De Baere T, Kulik L, et al. Locoregional therapies in the era of molecular and immune treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;18:293–313. 10.1038/s41575-020-00395-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitale A, Trevisani F, Farinati F, et al. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in the precision medicine era: from treatment stage migration to therapeutic hierarchy. Hepatology 2020;72:2206–18. 10.1002/hep.31187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, et al. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American association for the study of liver diseases and the American Society of transplantation. Hepatology 2014;59:1144–65. 10.1002/hep.26972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2010;30:052–60. 10.1055/s-0030-1247132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi X, Yang M, Ma L, et al. Synergizing sunitinib and radiofrequency ablation to treat hepatocellular cancer by triggering the antitumor immune response. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e001038. 10.1136/jitc-2020-001038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Library of Medicine (U.S) . A study of MG4101 (allogeneic natural killer cell) for Intermediate-stage of hepatocellular carcinoma, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marinelli B, Cedillo M, Pasik SD, et al. Safety and efficacy of locoregional treatment during immunotherapy with nivolumab for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 41 interventions in 29 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2020;31:1729–38. 10.1016/j.jvir.2020.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhan C, Ruohoniemi D, Shanbhogue KP, et al. Safety of combined yttrium-90 radioembolization and immune checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2020;31:25-34. 10.1016/j.jvir.2019.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Library of Medicine (U.S) . Pembrolizumab plus Y90 radioembolization in HCC subjects, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Library of Medicine (U.S) . Safety and efficacy study of radioembolization in combination with Durvalumab in locally advanced and unresectable HCC (solid, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Library of Medicine (U.S) . Cabozantinib combined with Ipilimumab/Nivolumab and TACE in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Library of Medicine (U.S) . Study of pembrolizumab following TACE in primary liver carcinoma (petal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:940–52. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30351-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee P-C, Chao Y, Chen M-H, et al. Risk of HBV reactivation in patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-treated unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e001072. 10.1136/jitc-2020-001072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carroll HK, Aleem U, Varghese P, et al. Trial-in-progress: a pilot study of combined immune checkpoint inhibition in combination with ablative therapies in subjects with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2021;39:TPS355. 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.3_suppl.TPS355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogel A, Saborowski A, Hinrichs J, et al. LBA37 IMMUTACE: a biomarker-orientated, multi center phase II AIO study of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in combination with nivolumab performed for intermediate stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Annals of Oncology 2021;32:S1312. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.2114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raoul J-L, Sangro B, Forner A, et al. Evolving strategies for the management of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: available evidence and expert opinion on the use of transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer Treat Rev 2011;37:212–20. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forner A, Da Fonseca LG, Díaz-González Álvaro, et al. Controversies in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. JHEP Rep 2019;1:17–29. 10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Titano J, Voutsinas N, Kim E. The role of radioembolization in bridging and downstaging hepatocellular carcinoma to curative therapy. Semin Nucl Med 2019;49:189–96. 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2019.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2021-004205supp001.pdf (1,022.7KB, pdf)

jitc-2021-004205supp004.pdf (30.4KB, pdf)

jitc-2021-004205supp002.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

jitc-2021-004205supp003.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.