Abstract

Binge drinking is a harmful pattern of alcohol use that is associated with a number of serious health problems. Of particular interest are the rapid alterations in neuroimmune gene expression and the concurrent activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation associated with high intensity drinking. Using a rat model of acute binge-like ethanol exposure, the present studies were designed to assess the role of corticosterone (CORT) in ethanol-induced neuroimmune gene expression changes, particularly those associated with the NFκB signaling pathway, including rapid induction of IL-6 and IκBα, and suppression of IL-1β and TNFα gene expression evident after administration of moderate to high doses of ethanol (1.5-3.5 g/kg ip) during intoxication (3 hr post-injection). Experiment 1 tested whether inhibition of CORT synthesis with metyrapone and aminoglutethimide (100 mg/kg each, sc) would block ethanol-induced changes in neuroimmune gene expression. Results indicated that rapid alterations in IκBα, IL-1β, and TNFα expression were completely blocked by pretreatment with the glucocorticoid synthesis inhibitors, an effect that was reinstated by co-administration of exogenous CORT (3.75 mg/kg) in Experiment 2. Experiment 3 assessed whether these rapid alterations in neuroimmune gene expression would be evident when rats were challenged with a subthreshold dose of ethanol (1.5 g/kg) in combination with 2.5 mg/kg CORT, which showed limited evidence for additive effects of low-dose CORT combined with a moderate dose of ethanol. Acute inhibition of mineralocorticoid (spironolactone) or glucocorticoid (mifepristone) receptors, alone (Experiment 4) or combined (Experiment 5) had no effect on ethanol-induced changes in neuroimmune gene expression, presumably due to poor CNS penetrance of these drugs. Finally, Experiments 6 and 7 showed that dexamethasone (subcutaneous; a GR agonist) recapitulated effects of ethanol. Overall, we conclude that ethanol-induced CORT synthesis and release is responsible for suppression of IL-1β, TNFα, and induction of IκBα in the hippocampus through GR signaling. Interventions designed to curb these changes may reduce drinking, and subdue detrimental neuroimmune activation induced by ethanol.

Introduction

Alcohol use and misuse can have serious negative economic and health consequences for those affected. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), alcohol use disorders (AUDs) affect approximately 15.1 million people in the United States. It is estimated that AUDs contribute to a $200 billion burden on the U.S. economy (Sacks et al., 2015). Binge drinking, defined as consuming 5 or more standard alcoholic drinks for men and 4 or more drinks for women within a 2-hour time period, resulting in blood ethanol concentrations (BECs) of at least 80 mg/dL, is the most common pattern of excessive alcohol use. High-intensity drinking, defined as consumption of two or more times the typical binge and resulting in BECs substantially higher than 100 mg/dL, is a particularly hazardous form of alcohol use (Rosoff et al., 2019). These drinking patterns are associated with long-term problems, as studies show that recurrent episodes of heavy drinking were linked to greater instances of injury and AUD (Jackson, 2008). Heavy drinking is associated with higher instances of liver disease, brain damage, and hospitalization (Rocco, Compare, Angrisani, Sanduzzi Zamparelli, & Nardone, 2014), increasing susceptibility to injury, risk of cancer, and the onset of high blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases, (Ahmed, 2008).

The hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a neuroendocrine system through which glucocorticoid hormones are produced and elicit their inhibitory and homeostatic effects on the body (Monteleone et al., 2011). The HPA axis is activated in response to external stressors (Blandino et al., 2006; Frank et al., 2019; Laroche et al., 2009; Ornelas & Keele, 2018; Staples et al., 2014) as well as ethanol intoxication and subsequent withdrawal (Buck et al., 2011; Richardson et al., 2008; Vore et al., 2017; Walter et al., 2017). The paraventricular nucleus (PVN) acts as the origin of the HPA axis and plays an important role in regulating the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland, which in turn controls the release of corticosterone (cortisol in humans) from the adrenal glands. Other neuronal regions, the dorsal hippocampus (dHPC) and the amygdala in particular, are rich in corticosteroid receptors and contribute to extrinsic regulation of the HPA axis (Jacobson & Sapolsky, 1991; Weidenfeld & Ovadia, 2017). Since binge-like ethanol exposure activates the HPA axis and elicits the release of corticosterone, these sites represent informative targets for studying corticosteroid-mediated transcriptional changes (Spencer & Hutchison, 1999).

The HPA axis and glucocorticoid signaling is an emerging area of interest in preclinical and clinical study of AUD. Ethanol activates the HPA axis, and glucocorticoid function modulates drinking behavior. Several studies have shown that experimenter-administered or self-administration of ethanol increased corticosterone levels in the rat (Buck et al., 2011; Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2014, 2015; Richardson et al., 2008; Richey et al., 2012; Willey et al., 2012). Following repeated ethanol exposures and during ethanol dependence, the activation and expression of glucocorticoid receptors (GR) were changed in a brain region-specific manner (Edwards et al., 2015; McGinn et al., 2021; Somkuwar et al., 2017). These changes are proposed to play a substantial role in a transition from positive reinforcement to negative reinforcement from drinking, and support for this hypothesis has come from studies in rats demonstrating that antagonism of GR signaling with mifepristone or experimental selective GR antagonist compounds during ethanol exposure can curb enhanced dependence-like intake (Edwards et al., 2015; McGinn et al., 2021; Sanna et al., 2016; Vendruscolo et al., 2012). These findings suggest that GR signaling is a promising therapeutic target, because early clinical studies have shown that chronic mifepristone, a GR and progesterone inhibitor, decreased drinking in rats and humans with AUD (Vendruscolo et al., 2015).

Individuals with AUD have expression of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Erickson, Grantham, Warden, & Harris, 2019; Neupane, 2016, Donnadieu-Rigole et al., 2016, 2018). In rodent models, binge-like ethanol exposure activates inflammation-associated transcriptional factors, in particular Nuclear Factor κB (NF-κB). Under normal conditions, NF-κB activation usually leads to downstream expression of genes such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), IκBα, and interleukins IL-1β and IL-6 (Gano et al., 2019; Qin, et al., 2008). Likewise, Quan et al. (2000; 1997) have shown that IκBα enhancement, a marker of NFκB activation, was evident in the brain following a peripheral bacterial challenge and could be attenuated by blockade of glucocorticoid receptors with mifepristone, suggesting that NFκB induction may be partially dependent on a corticosterone signaling mechanism. Given that ethanol produced changes in IκBα expression similar to those of peripheral bacterial challenge, it stands to reason that this induction may be also dependent on corticosterone signaling. Acute ethanol stimulates the HPA axis, increasing circulating corticosterone. Corticosterone has been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects that manifest as reduced expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α, whereas induction of other inflammatory factors may be increased by corticosteroids (Barnum et al., 2008; Whirledge & Cidlowski, 2013). These changes in IL-1β and TNF-α gene expression closely resemble those produced by ethanol during the acute intoxication phase, yet a mechanistic link between ethanol and corticosterone signaling has not been well-defined. Therefore, these experiments tested the hypothesis that corticosterone mediates the NFκB-inducing and IL-1β/TNFα-reducing effects of acute binge-like ethanol.

Our lab has shown that intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of 4 g/kg ethanol increased expression of the cytokine IL-6 and IκBα in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), dorsal hippocampus (dHPC), and amygdala 3 hr post administration during the peak of BECs (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2015). At the same time point, these brain regions showed decreased levels of IL-1β and TNF-α, typical pro-inflammatory factors, suggesting a unique and unconventional transcriptional signature produced by high dose acute ethanol challenge (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2015). Typically, these factors (TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β) are all enhanced following activation of the NF-κB pathway. Likewise, IκBα, an inhibitor of NFκB, is produced in response to the increase in this nuclear factor (Miyamotot et al., 1994), and so high IκBα expression is commonly predictive of high cytokine expression. Cytokines are secreted predominantly by immune cells and coordinate various features of innate immunity, host defense, and recovery from tissue injury (Dunn et al., 2005). Zou & Crews (2010) demonstrated that when exposed to acute ethanol in vitro, hippocampal slice cultures demonstrated robust activation of NF-κB signaling that is linked to the expression of multiple pro-inflammatory factors, including TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β. Overall, it is well documented that NF-κB activity can be driven by ethanol exposure and that in turn NF-κB can promote the expression of neuroimmune factors. However, the unique expression profile of cytokine genes in the brain during intoxication indicates that NF-κB activity may not be the only pathway regulating cytokine gene expression.

Enhancement in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines indicates the onset of sickness-like behaviors and may contribute to the development of alcohol-related brain damage. Even a single high-dose challenge is sufficient to elicit changes in NF-κB related gene expression, therefore activation of NF-κB has been an important target of research in understanding the neuroimmune outcomes of high-dose ethanol exposure (Kent, Bret-Dibat, Kelley, & Dantzer, 1996; Turnbull & Rivier, 1995). Analyses of rat strains with a high preference for alcohol show increased NF-κB expression with drinking (Zou & Crews, 2010). Research has demonstrated that NF-κB changes associated with ethanol is dependent on signaling at the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). However, a cross-species and cross-institution collaboration showed a compelling lack of impact from TLR4 on ethanol consumption; in both mice and rats, TLR4 knockout or inhibition of the pathway had little or no effects on ethanol intake (Harris et al., 2017). These findings together may dissociate TLR4 signaling from drinking behavior, but the activation of TLR4, NF-κB, and proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα) are clearly important in the pathogenesis of AUD-related brain changes. Despite widespread evidence for rapid alterations in neuroimmune gene expression after binge-like acute ethanol challenge, the mechanisms underlying this cytokine modulation remain unclear. The present experiments provide evidence that glucocorticoid signaling is key in transducing the immune effects of binge-like ethanol.

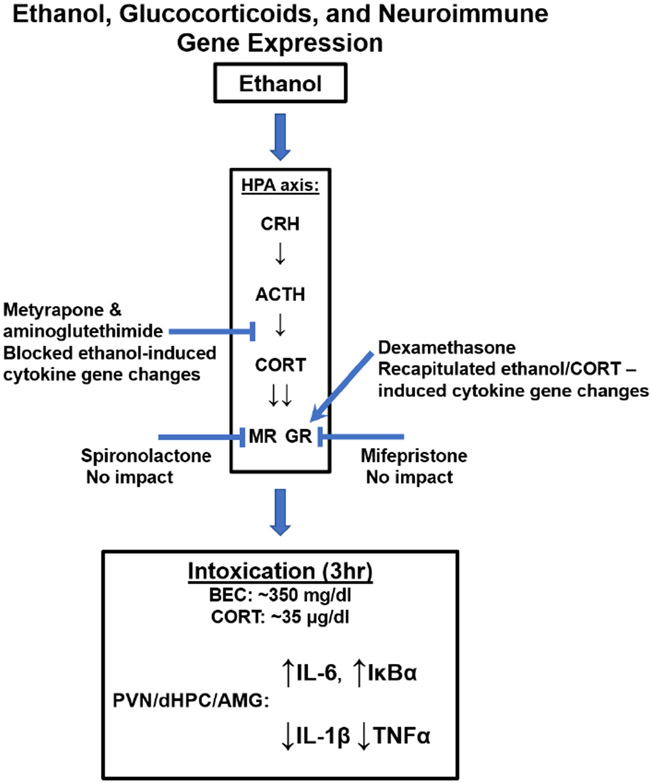

Given the implication of both the neuroimmune and glucocorticoid systems in the pathogenesis of AUD, the interrelation between the two in response to ethanol is of great importance. Therefore, the present experiments were designed to examine whether ethanol-induced corticosterone release mediated the ethanol-induced changes in cytokine gene expression in key brain regions associated both with HPA regulation and negative affect: the hippocampus, PVN, and amygdala (see Figure 1 for a schematic overview). Given that (a) ethanol intoxication increases corticosterone release and that (b) corticosterone affects brain cytokine expression, we reasoned that ethanol could change cytokine gene expression through a corticosterone-dependent mechanism. To test this hypothesis, we performed a series of pharmacological studies involving administration of corticosterone synthesis inhibitors (Experiments 1 & 2), exogenous corticosterone (Experiments 2 & 3), inhibitors of MR (spironolactone) or GR (mifepristone) (Experiments 4 & 5), and administration of dexamethasone (a GR agonist) in the presence or absence of ethanol (Experiments 6 & 7).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of a hypothesized link between ethanol, glucocorticoids, and neuroimmune gene expression based on key findings from the present experiments.

General Methods and Materials

Subjects

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (290-360 g) were either purchased from Envigo (Exp 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 & 7) or bred in-house from breeder rats purchased from Envigo (Exp 4). The day of birth was designated as P0 and litters were culled to a maximum of 10 pups per litter, with approximately equal sex ratios (n=4-6 of each sex in each litter) on P1. Offspring were weaned on P21 and housed with a non-littermate until the time of experimentation. No more than 1-2 pups per litter were assigned to each experimental condition to control for litter effects (Holson & Pearce, 1992). All shipped rats were given two weeks to acclimate to the colony environment (22 ± 1°C; 12:12 light: dark cycle with lights on at 7:00) before the experiment began. Animals were pair-housed in standard clear Plexiglas cages with ad libitum access to food and water. All rats were handled for 3-4 minutes during each of two days prior to injections and tissue collection. Animals were treated in accordance with the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, and this experimental procedure was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Binghamton University, State University of New York.

Tissue Collection and Processing

Rats were injected i.p. with ethanol (1.5-3.5 g/kg) to assess neuroimmune gene expression changes. The i.p. model was chosen for its robust induction of neuroimmune genes observed in prior work (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2014, 2015; Gano et al., 2019). IP injection of ethanol is also a common component of vapor inhalation studies, where ip injection of ethanol is administered as a loading dose at the time for vapor initiation in studies of alcohol dependence (Patel et al., 2019; Varodayan et al., 2017). Importantly, a similar pattern of results has been seen with i.g. administration (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2015), suggesting that route of administration is not critical for ethanol-dependent release of corticosterone. Three hours after ethanol injection (i.p.), rats were quickly decapitated, and trunk blood was collected in EDTA-coated blood collection tubes. Blood was centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C, and plasma supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C until the time of assay. Brains were removed, submerged in ice-cold isopentane for 15 sec, and frozen at −80°C before being sectioned using a cryostat maintained at −20°C. A rat brain atlas was used as reference to obtain 1.0-2.0 mm micro punches of the PVN, amygdala and dorsal hippocampus of each brain. These brain punches were stored at −80°C until RNA extraction.

Assessment of Blood Ethanol Concentration and Corticosterone

Blood ethanol concentrations (BECs) were determined using an Analox AM-1 alcohol analyzer. In preparation for the measurement of total corticosterone (CORT) levels, samples were immersed in a 75°C hot water bath for 60 minutes to denature endogenous corticosteroid binding globulin (CBG). This heat denaturation step was utilized instead of the steroid displacement reagent because our prior work has shown it to be more effective for denaturing CBG. Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits (ENZO) were used to evaluate the total CORT (Spencer & Deak, 2017).

Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Each brain structure was transferred into a 2.0 ml Eppendorf tube containing 500 μL of Trizol RNA reagent and a 5 mm stainless steel bead. A Qiagen Tissue Lyser was then used to shake the tubes for 2 minutes in order to ensure complete homogenization of the tissue. 100 μL of chloroform was added to the Trizol mixture, the tubes were shaken, and then centrifuged at 4°C for 15 min. Then, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, equal volume of 70% ethanol was added to the supernatant and purified using RNeasy mini columns (Qiagen). The columns were washed with buffer and RNA was eluted in 30 μL of RNAase-free water (65°C). A Nanodrop micro-volume spectrophotometer was used to evaluate the amount and quality of RNA. The total yield of RNA was stored at −80°C until time of cDNA synthesis.

Synthesis of cDNA was completed on 0.1-1.0 μg of normalized total RNA from each sample using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit. All cDNA was stored at −20°C until the assay was conducted. RT-PCR was run using a CFX 384 real-time PCR detection system (BioRad Laboratories) to evaluate IL-6, IκBα, IL-1β, TNFα, cFOS and GAPDH expression (see Vore, Barney, Gano, Varlinskaya, & Deak, 2021).

Statistics

Data were analyzed using factorial ANOVAs (p < 0.05) appropriate to each experimental design. Experiments 1, 3, 4 and 5 were analyzed using two-way ANOVAs, whereas Experiments 2, 6, and 7 used one-way ANOVA. For experiment 7, Dunnett’s post-hoc comparison was used to compare each group to the ethanol only group. For all other experiments, Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons was used in post-hoc analyses of any significant effects found in the ANOVAs.

Experimental Design and Procedures

Experiment 1

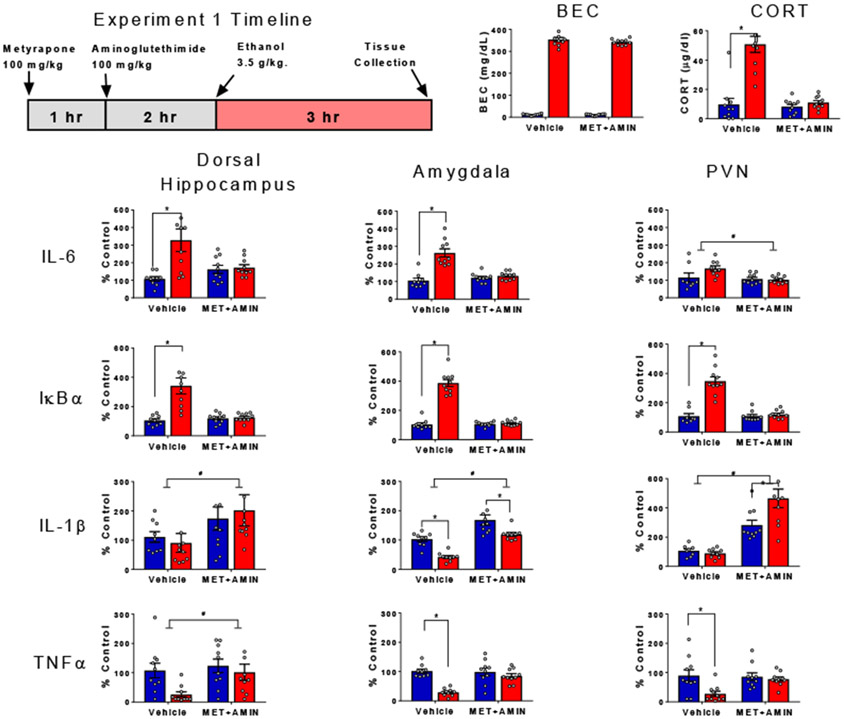

This experiment was designed to test the necessity of endogenous CORT in producing brain cytokine changes following ethanol. To achieve this, we administered metyrapone and aminoglutethimide prior to ethanol administration to ablate CORT synthesis (see Figure 2, timeline). The combination of these drugs produces robust inhibition of CORT synthesis through inhibiting 11β-hydroxylase and cholesterol processing in the adrenals, respectively, without inducing sedative effects of high-dose metyrapone (Plotsky & Sawchenko, 1987). Previous work in our lab has effectively used this dose regimen, further supporting its efficacy in blocking corticosteroid biosynthesis (see Blandino et al., 2009; Hueston et al., 2014a). Rats were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions in a 2 (ethanol challenge: saline or 3.5 g/kg) x 2 (drug pre-treatment: vehicle or metyrapone + aminoglutethimide) experimental design (n=10, N=40). On the test day, synthesis of CORT in half of the rats was suppressed with injection of metyrapone (2-methyl-1,2-di-3-pyridyl-1-propanone) followed by aminoglutethimide. Metyrapone (100 mg/kg) was dissolved in propylene glycol with gentle heating and injected subcutaneously (s.c.) at 0.5 mL/kg. One hour after the metyrapone injection, these rats were injected subcutaneously with aminoglutethimide (100 mg/kg), which was also dissolved in propylene glycol (Blandino, et al., 2009). Two hours after the aminoglutethimide injections, one half of rats received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of ethanol (3.5 g/kg ethanol was diluted from 95% to 20% with pyrogen-free physiological saline (Barney et al., 2019). Between each set of injections, rats were left undisturbed in their home cages. Rats were euthanized 3 hr after ethanol injection and tissue was harvested as described above (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Ethanol-induced cytokine gene expression and blockade of corticosterone synthesis.

BECs, CORT levels in plasma, gene expression of IL-6, IκBα, IL-1β, and TNFα in the dorsal hippocampus, amygdala and PVN were assessed in male rats pre-treated with either vehicle or metyrapone + aminoglutethimide prior to i.p. injection of saline or ethanol. Gene expression data were calculated as a relative change in gene expression using the 2−ΔΔC(t) method, with (GAPDH) used as a reference gene and the vehicle – saline group serving as the ultimate control. Bars denote group means ± standard error of the mean (represented by vertical error bars). Asterisks (*) signify significant ethanol-induced changes in CORT and gene expression (p < 0.05), whereas pound signs (#) indicate significant effects of blockade of corticosterone synthesis with metyrapone + aminoglutethimide.

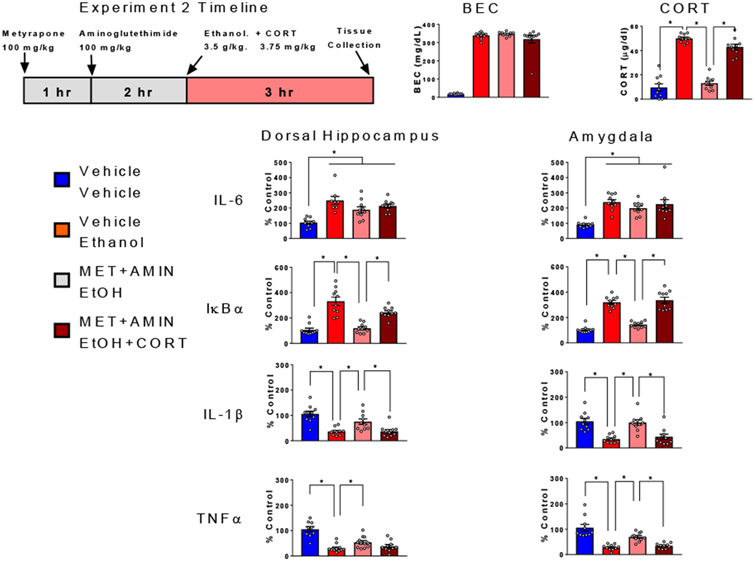

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 was designed to test the hypothesis that circulating CORT levels at time of brain tissue collection may be a powerful determinant of cytokine changes observed in the brain following acute ethanol challenge. Specifically, this experiment tested the ability of exogenous CORT to restore ethanol effects on cytokine expression in rats that had endogenous CORT synthesis blocked. Rats were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions (n=10, N=40): the first group received three s.c. injections of vehicle and an i.p. injection of saline (Veh+Sal control group); the second group also received three s.c. injections of vehicle and an i.p. injection of 3.5 g/kg ethanol (Veh+EtOH group); the third group was injected s.c. with metyrapone and aminoglutethimide, and vehicle and an i.p. injection with ethanol (Met+EtOH); whereas the fourth group was injected s.c. with metyrapone, aminoglutethimide, and CORT (3.75 mg/kg) and an i.p. injection with ethanol (Met+EtOH+CORT). The injection timeline was the same as for Experiment 1, with the addition of a CORT (or vehicle) injection being given immediately after the i.p. injection of ethanol or saline. This CORT dose was predicted to approximate blood CORT concentration induced by a challenge with 3.5 g/kg ethanol at 3 hr post-injection (Barnum et al., 2008). All rats received a total of 3 s.c. injections and 1 i.p. injection (see Figure 3). Rats were euthanized 3 hr after ethanol injection and tissue was harvested as described above (see Figure 3), with the exception that the PVN was not assessed. In Experiment 1, gene expression changes were similar across all three brain regions, and we therefore focused our analyses on the amygdala and hippocampus; regions where ongoing research suggests that cytokine signaling is important in the response to ethanol (Hernandez et al., 2016; Ethanol and Cytokines in the Central Nervous System, 2018).

Figure 3. Ethanol-induced cytokine gene expression altered by blockade of corticosterone synthesis : Impact of exogenous corticosterone.

BECs, CORT levels in plasma, gene expression of IL-6, IκBα, IL-1β, and TNFα in the dorsal hippocampus and amygdala were assessed in male rats randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions: the Veh+Sal group received three s.c. injections of vehicle and an i.p. injection of saline, the Veh+EtOH group also received three s.c. injections of vehicle and an i.p. injection of 3.5 g/kg ethanol, the Met+EtOH group was injected s.c. with metyrapone + aminoglutethimide, and injected with vehicle (s.c.) immediately following an i.p. injection with ethanol, whereas the Met+EtOH+CORT group was pre-treated s.c. with metyrapone + aminoglutethimide, and injected with CORT (3.75 mg/kg, s.c.) immediately following an i.p. injection with ethanol (Met+EtOH+CORT). Gene expression data were calculated as a relative change in gene expression using the 2−ΔΔC(t) method, with (GAPDH) used as a reference gene and the vehicle – saline group serving as the ultimate control. Bars denote group means ± standard error of the mean (represented by vertical error bars). Asterisks (*) signify significant differences in CORT levels and gene expression between Veh+Sal and Veh+EtOH (ethanol effects), Veh+EtOH and Met+EtOH (effects of blockade of CORT synthesis), as well as Met+EtOH and Met+EtOH+CORT (CORT-induced reinstatement of ethanol effects following blockade of CORT synthesis).

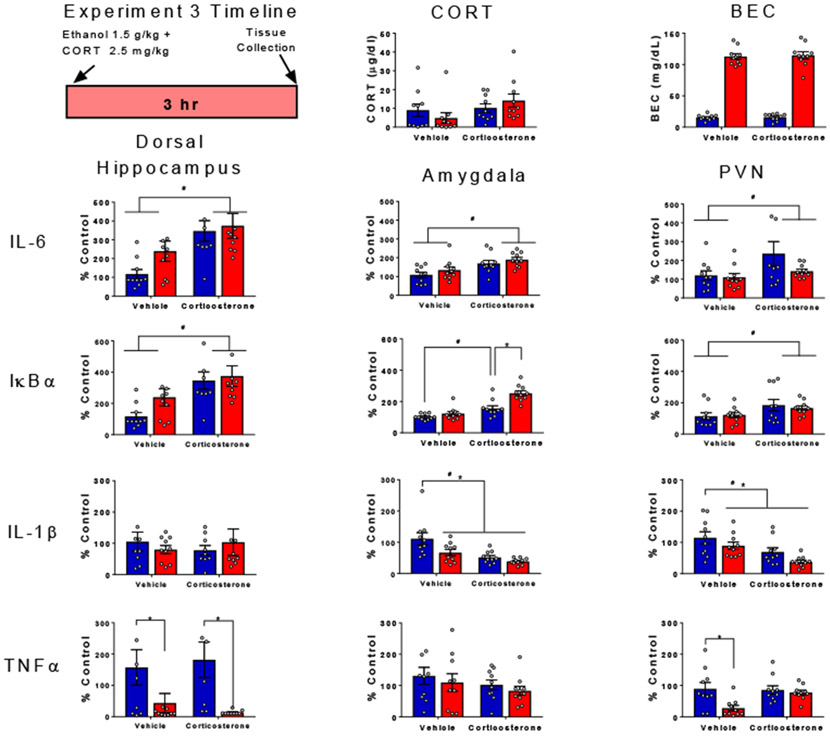

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 was designed to test whether moderate-dose exogenous CORT (2.5 mg/kg, s.c.) interacts with a lower dose of ethanol (1.5 g/kg, i.p.) to produce synergistic or additive alterations of cytokine gene expression. This dose of CORT was used to mimic a natural stress-induced rise in plasma corticosterone (Barnum et al., 2007, 2008). Rats were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions using a using a 2 (ethanol challenge: saline or 1.5 g/kg) x 2 (CORT treatment: vehicle vs. 2.5 mg/kg) factorial design (n=10 per group; N=40). Rats were given i.p. ether 1.5 g/kg ethanol or saline immediately prior to a 2.5 mg/kg subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of CORT or vehicle (40% propylene glycol in PBS) as shown in Figure 4. Rats were euthanized 3 hr after ethanol injection and tissue was harvested as described above (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Cytokine gene expression following co-administration of ethanol and corticosterone in a sub-threshold dose range.

BECs, CORT levels in plasma, gene expression of IL-6, IκBα, IL-1β, and TNFα in the dorsal hippocampus, amygdala and PVN were assessed in male rats given i.p. ether 1.5 g/kg ethanol or saline immediately prior to a 2.5 mg/kg subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of CORT or vehicle). Gene expression data were calculated as a relative change in gene expression using the 2−ΔΔC(t) method, with (GAPDH) used as a reference gene and the vehicle – saline group serving as the ultimate control. Bars denote group means ± standard error of the mean (represented by vertical error bars). Asterisks (*) signify significant ethanol-induced changes in gene expression (p < 0.05), whereas pound signs (#) indicate significant effects of CORT (p <0.05).

Experiment 4

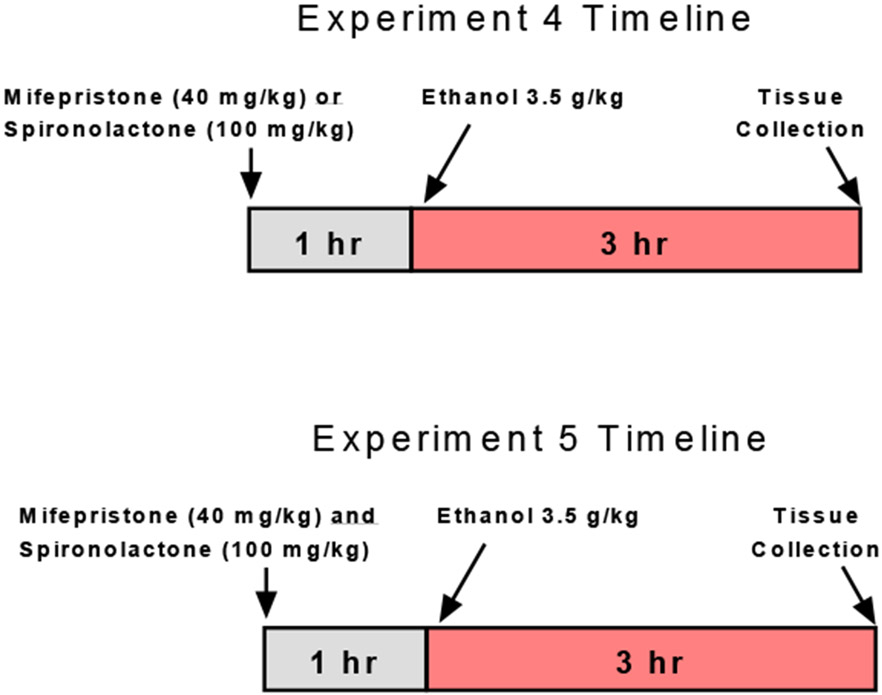

In order to test the specificity of the signaling effects of CORT on brain cytokine mRNA expression observed in the previous experiments to glucocorticoid (GR) or mineralocorticoid receptors (MR), these receptors were pharmacologically blocked prior to ethanol administration. Rats were randomly assigned to one of six experimental conditions in a 2 (ethanol challenge: saline or ethanol) x 3 (drug: vehicle, mifepristone, or spironolactone) experimental design (n=10, N=60). One hr prior to an i.p. injection of saline or 3.5 g/kg ethanol rats received either mifepristone (40 mg/kg) or spironolactone (100 mg/kg) s.c. or the propylene glycol vehicle (Figure 5). Mifepristone was used to block activity at glucocorticoid receptor, while spironolactone was used to antagonize mineralocorticoid receptors. These drugs and similar dose ranges have been used to dissect effects of MR vs.GR activation on ethanol drinking (Koenig & Olive, 2004; Makhijani et al., 2018, 2020; Savarese et al., 2020; Vendruscolo et al., 2015). Rats were euthanized 3 hr after ethanol injection and tissue was harvested as described above. Given the lack of effects in the hippocampus, we performed Experiment 5 instead of expanding to other brain regions.

Figure 5. Schematic illustration of experimental timeline for Experiments 4 & 5.

Experiment 5

Evidence suggests that MR and GR antagonism does regulate the HPA axis in a unique fashion compared to inhibition of either receptor type alone (Spencer et al., 1998). Thus, a ‘superblocker’ approach involving combined injection of spironolactone and mifepristone was used to test this potential synergistic effect of MR and GR activity to produce the NFκB-related changes in gene expression observed following high dose ethanol or CORT. Rats were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions in a 2 x 2 experimental design (n=10, N=40). One hr prior to injection of 3.5 g/kg ethanol i.p. rats received a combined injection of mifepristone (40 mg/kg) and spironolactone (100 mg/kg) s.c. or the propylene glycol vehicle (Figure 5). Rats were euthanized 3 hr after ethanol injection and hippocampus was harvested as described above. Given that effects of ethanol or CORT administration were not region-specific, lack of effects in the hippocampus was compelling evidence that peripheral MR and GR antagonist administration was not sufficient to block ethanol/CORT signaling effects, likely due to moderate CNS penetrance of these drugs.

Experiment 6

In Experiments 4 and 5, we observed no effect of MR or GR antagonists given peripherally on the ethanol-induced neuroimmune gene expression changes. This is potentially explained by poor penetrance of these drugs through the blood brain barrier (Kim et al., 1998). To further test the role of GR, dexamethasone was administered in the absence of ethanol to test whether GR activation was sufficient to recapitulate neuroimmune gene changes seen with high-dose ethanol administration. Rats were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions (n=10 per group, N=40). Rats received a s.c. injection of dexamethasone (0, 50, 500, or 1000 μg/kg) or vehicle (50% propylene glycol in saline) (Figure 6). Rats were euthanized 4 hr after injection to mirror the timeline of exogenous CORT administration performed in prior experiments above and hippocampus and PVN were harvested for later assessment of neuroimmune gene expression.

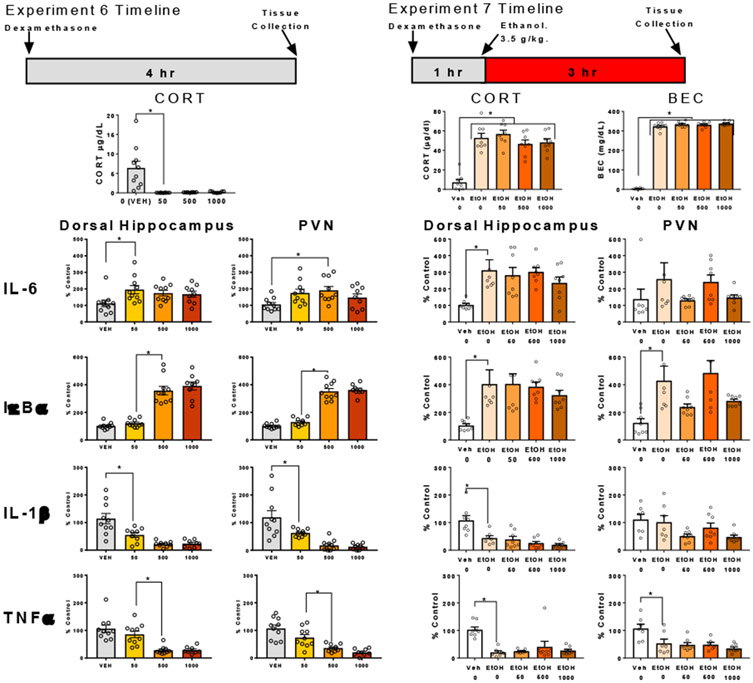

Figure 6. Cytokine gene expression following administration of dexamethasone with or without ethanol.

BECs, CORT levels in plasma, gene expression of IL-6, IκBα, IL-1β, and TNFα in the dorsal hippocampus and PVN were assessed in male rats 4 hr after they were given s.c. dexamethasone or vehicle. In Experiment 7, rats also received either saline or ethanol 3.5 g/kg 3 hr prior to euthanasia. Gene expression data were calculated as a relative change in gene expression using the 2−ΔΔC(t) method, with (GAPDH) used as a reference gene and the vehicle – saline group serving as the ultimate control. Bars denote group means ± standard error of the mean (represented by vertical error bars). Asterisks (*) signify significant changes in gene expression (p < 0.05).

Experiment 7

In Experiment 6, dexamethasone administration produced a pattern of cytokine expression similar to that seen with high-dose ethanol, but the magnitude of the changes produced by ethanol vs. dexamethasone could not be directly compared. Therefore, we applied dexamethasone and ethanol in the same rats to determine whether dexamethasone could produce changes in neuroimmune genes greater than with ethanol alone. We hypothesized that dexamethasone might enhance the cytokine response to ethanol through greater activation of GR. Rats were randomly assigned to one of five experimental conditions (n=8 per group, N=40). One hr prior to injection of 3.5 g/kg ethanol i.p. rats received a s.c. injection of dexamethasone (50, 100, 500, or 1000 μg/kg) or vehicle (50% propylene glycol and 50% saline). An additional control group was included, which received vehicle s.c. and saline i.p. injections instead of ethanol, to reproduce the effects of ethanol on cytokine genes within this experiment (Figure 6). Rats were euthanized 3 hr after ethanol injection and hippocampus and PVN were harvested as described above.

Results

Experiment 1. Ethanol-induced cytokine gene expression and blockade of corticosterone synthesis.

Blood measures of CORT confirmed that the metyrapone and aminoglutethimide pre-treatment effectively blocked corticosterone synthesis and prevented the ethanol-induced rise in corticosterone, as evidenced by a drug pre-treatment by ethanol challenge interaction [F (1, 36) = 28.2, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.2106]. BECs were unaffected by pre-treatment with metyrapone and aminoglutethimide [F (1, 36) = 1.31, p = 0.26, η2 = 0.0003].

IL-6 gene expression was enhanced by ethanol in the hippocampus and amygdala, and this effect was prevented by blocking corticosterone synthesis as evidenced by drug pre-treatment by ethanol challenge interactions [hippocampus: F (1, 35) = 8.29, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.0015; amygdala: F (1, 35) = 25, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.2297]. In the PVN, IL-6 expression was significantly lower in rats that received metyrapone and aminoglutethimide relative to those pre-treated with vehicle as evidenced by main effect of drug pre-treatment [F (1, 33) = 6.25, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.1368], with this effect driven by animals challenged with ethanol. Ethanol challenge also induced large increases in IκBα gene expression in all three brain regions which were prevented by pre-treatment with metyrapone and aminoglutethimide, as evidenced by significant drug pre-treatment by ethanol challenge interactions [hippocampus: F (1, 35) = 15.2, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.1910; amygdala: F (1, 35) = 101, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.2899; PVN: F (1, 34) = 36.9, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.2347). IL-1β gene expression was significantly increased by metyrapone and aminoglutethimide pre-treatment in the hippocampus regardless of ethanol challenge [F (1, 35) = 4.99, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.1233]. In the amygdala, ethanol challenge significantly decreased expression of IL-1β [F (1, 33) = 24.93, p < 0.0001, η2 = 0.2467], while pre-treatment with corticosterone synthesis blockers significantly increased expression of IL-1β regardless of ethanol challenge [F (1, 330 = 41.38, p < 0.0001, η2 = 0.4096]. In the PVN, enhancement of IL-1β gene expression by blockage of corticosterone synthesis with metyrapone and aminoglutethimide was significantly higher in animals challenged with ethanol relative to saline controls [drug pre-treatment by ethanol challenge interaction, F (1, 33) = 6.28, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.676].

In the hippocampus, pre-treatment with corticosterone synthesis blockers increased TNFα gene expression relative to controls pre-treated with vehicle [F (1, 36) = 4.23, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.891], with this effect driven by ethanol-injected animals. In the amygdala and PVN, blocking corticosterone synthesis prevented an ethanol-induced reduction in TNFα [drug pre-treatment by ethanol challenge interaction for amygdala: F(1, 35) = 12, p < 0.05, η2 = 14.34, and PVN: F(1, 36) = 4.136, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.822]. Especially in the ethanol-only group, levels of TNFα dropped below the level of detection. In these cases, a lower-limit substitution of 10% of baseline was used.

Experiment 2. Ethanol-induced cytokine gene expression altered by blockade of corticosterone synthesis: Impact of exogenous corticosterone.

As expected, the Veh+EtOH group demonstrated a significant increase in CORT level relative to the Veh+Sal group (p <0.05), and this ethanol-induced increase in the Veh+EtOH group was blocked by metyrapone and aminoglutethimide pre-treatment in the Met+EtOH group (p < 0.05). Injection of 3.75 mg/kg of CORT resulted in circulating levels of CORT comparable to those evident after 3.5 g/kg ethanol at 3 hr post injection (Veh+EtOH vs. Met+EtOH+CORT, p = 0.11). Thus, the CORT concentration was reinstated in the absence of endogenous synthesis. CORT injections or synthesis blockade did not affect the BECs of rats at the time of euthanasia (n.s. comparisons between all ethanol groups).

In contrast to Experiment 1, ethanol-induced increase in IL-6 gene expression was less affected in the hippocampus or the amygdala by the CORT synthesis blockade, with all experimental groups showing significant ethanol-associated increases relative to the Veh+Sal group (p < 0.05, for all comparisons). However, significant ethanol-induced increases of IκBα gene expression relative to Veh+Sal controls (hippocampus, p < 0.05; amygdala, p < 0.05) were blocked by metyrapone and aminoglutethimide pre-treatment (hippocampus, p < 0.05; amygdala, p < 0.05) and were reinstated with addition of exogenous CORT in both regions (hippocampus, p < 0.05; amygdala, p < 0.05). IL-1β gene expression was significantly suppressed by ethanol in both regions of interest (hippocampus, p < 0.05; amygdala, p < 0.05). This ethanol effect was dependent on CORT synthesis, since it was significantly attenuated in the Met+EtOH group (hippocampus, p < 0.05; amygdala, p < 0.05) and was reinstated by exogenous CORT in the Met+EtOH+CORT group (hippocampus, p < 0.05; amygdala, p < 0.05). The suppression of TNFα gene expression by ethanol (hippocampus, p < 0.05; amygdala, p < 0.05) was only partially attenuated by CORT synthesis inhibition (hippocampus, p = 0.07; amygdala, p < 0.05), but was fully recovered with injection of CORT in the Met+EtOH+CORT group (hippocampus, p < 0.05; amygdala, p < 0.05).

Experiment 3. Cytokine gene expression following co-administration of ethanol and corticosterone in a sub-threshold dose range.

Levels of CORT in the blood were not affected by either CORT administration [F (1, 36) = 3.06, p = 0.089, η2 = 0.75] or ethanol challenge [F (1, 36) = 0.00172, p = 0.97, η2 = 0.00]. These results indicated that the increase in CORT induced by either ethanol or exogenous CORT injection had been mostly resolved by 3 hr after administration. Importantly, BECs were not affected by CORT administration [F (1, 36) = 0.0936, p = 0.76, η2 = 0.0001].

CORT administration elevated IL-6 gene expression in the hippocampus [F (1, 35) = 12.25 p < 0.01, η2 = 0.2433], amygdala [F (1, 36) = 14.38 p < 0.01, η2 = 0.2731], and the PVN [F (1, 36) = 4.21, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.0965], with no effects of ethanol on IL-6 expression evident at this dose and timepoint. CORT administration enhanced IκBα gene expression in the hippocampus [F (1, 35) = 20.7, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.317) and PVN [F (1, 36) = 5.71, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.1536]. In the hippocampus, ethanol administration also increased IκBα expression [F (1, 35) = 8.69, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.133). In the amygdala, CORT administration significantly increased IκBα expression in saline-injected animals, with ethanol further enhancing this effect of CORT [ethanol challenge x CORT interaction, F (1, 36) = 7.5, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.0705]. Ethanol and CORT had no effects on IL-1β gene expression in the hippocampus. However, IL-1β expression in the amygdala was suppressed by CORT [F (1, 36) = 6.3, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.2526] or ethanol [F (1, 36) = 15, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.107], with similar effects of CORT [F (1, 36) = 13.34, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.2463] and ethanol [F (1, 36) = 4.76, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.8787] on IL-1β expression evident in the PVN. TNFα was suppressed by ethanol in the hippocampus [ F (1, 32) = 11.54, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.2635] and PVN [F (1, 36) = 7.113, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.14], but CORT prevented this ethanol-induced suppression in the PVN, as evidenced by an ethanol challenge x CORT interaction [F (1, 36) = 4.136, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.082].

Experiment 4. Ethanol-induced cytokine expression and pharmacological blockade of glucocorticoid or mineralocorticoid receptors.

Corticosterone levels and BECs in this experiment were unaffected by mifepristone or spironolactone injection (see Table 1). Likewise, neither drug modified the ethanol-induced changes in hippocampus gene expression. Ethanol increased IL-6 (F (1, 54) = 45.86, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.4508) and IκBα (F (1, 53) = 153.1, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.7408) and decreased TNFα (F (1, 54) = 147.3, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.7162) and IL-1 β (F (1, 54) = 88.45, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.6075).

Table 1. Ethanol-induced cytokine gene expression and blockade of MR or GR receptors.

BECs, CORT levels in plasma, gene expression of IL-6, IκBα, IL-1β, and TNFα in the dorsal hippocampus were assessed in male rats pre-treated with vehicle, mifepristone (GR antagonist), or spironolactone (MR antagonist) prior to i.p. injection of saline or ethanol. Gene expression data were calculated as a relative change in gene expression using the 2−ΔΔC(t) method, with (GAPDH) used as a reference gene and the vehicle – saline group serving as the ultimate control.

| Mean | SEM | n | Mean | SEM | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORT | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 1.8 | 0.8 | 10 | 34.0 | 1.1 | 10 |

| Spironolactone | 4.2 | 1.0 | 10 | 38.4 | 2.0 | 10 |

| Mifepristone | 0.1 | 0.0 | 10 | 34.5 | 1.6 | 10 |

| BEC | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 13.7 | 2.2 | 10 | 338.7 | 8.2 | 10 |

| Spironolactone | 9.8 | 1.6 | 10 | 346.8 | 10.7 | 10 |

| Mifepristone | 12.1 | 1.4 | 10 | 360.9 | 12.7 | 10 |

| IL-6 | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 108.4 | 15.9 | 10 | 318.3 | 36.7 | 10 |

| Spironolactone | 164.9 | 24.9 | 10 | 362.6 | 66.5 | 10 |

| Mifepristone | 126.0 | 10.6 | 10 | 349.1 | 43.8 | 10 |

| IkBa | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 105.2 | 3.7 | 10 | 407.6 | 13.3 | 10 |

| Spironolactone | 133.3 | 4.0 | 10 | 424.2 | 10.5 | 9 |

| Mifepristone | 122.4 | 3.5 | 10 | 419.7 | 14.2 | 10 |

| IL-1B | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 104.9 | 11.5 | 10 | 40.3 | 6.2 | 10 |

| Spironolactone | 126.1 | 14.1 | 10 | 43.3 | 6.5 | 10 |

| Mifepristone | 109.1 | 7.6 | 10 | 45.1 | 6.0 | 10 |

| TNFa | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 102.8 | 8.0 | 10 | 27.1 | 3.3 | 10 |

| Spironolactone | 85.4 | 10.7 | 10 | 21.4 | 3.5 | 10 |

| Mifepristone | 103.8 | 10.0 | 10 | 26.3 | 4.4 | 10 |

Experiment 5. Ethanol-induced cytokine expression and pharmacological blockade of both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors.

Corticosterone levels in this experiment were similarly unaffected by injection of the mifepristone and spironolactone when administered together (see Table 2). The drug cocktail did enhance BECs slightly at time of euthanasia (interaction F (1, 36) = 4.5, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.0009) but did not modify the ethanol-induced changes in hippocampus gene expression. Ethanol increased IL-6 (F (1, 33) = 76, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.69) and IκBα (F (1, 35) = 122, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.77) and decreased TNFα (F (1, 35) = 29, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.45) and IL-1β (F (1, 35) = 39, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.52).

Table 2. Ethanol-induced cytokine gene expression and simultaneous blockade of MR and GR receptors using a ‘superblocker’ approach.

BECs, CORT levels in plasma, gene expression of IL-6, IκBα, IL-1β, and TNFα in the dorsal hippocampus were assessed in male rats pre-treated with vehicle or a combination of mifepristone (GR antagonist) and spironolactone (MR antagonist), referred to here as ‘superblocker’ prior to i.p. injection of saline or ethanol. Gene expression data were calculated as a relative change in gene expression using the 2−ΔΔC(t) method, with (GAPDH) used as a reference gene and the vehicle – saline group serving as the ultimate control.

| Mean | SEM | n | Mean | SEM | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORT | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 3.1 | 0.9 | 10 | 41.1 | 1.9 | 10 |

| Superblocker | 4.1 | 2.0 | 10 | 44.8 | 1.9 | 10 |

| BEC | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 6.2 | 1.8 | 10 | 332.2 | 6.7 | 10 |

| Superblocker | 7.9 | 0.9 | 10 | 353.6 | 6.0 | 10 |

| IL-6 | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 100.9 | 6.7 | 9 | 267.3 | 15.7 | 10 |

| Superblocker | 118.2 | 12.7 | 10 | 271.3 | 33.3 | 8 |

| IkBa | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 103.3 | 5.1 | 9 | 370.3 | 24.0 | 10 |

| Superblocker | 103.1 | 7.3 | 10 | 323.4 | 34.5 | 10 |

| IL-1B | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 102.9 | 8.6 | 9 | 33.7 | 4.0 | 10 |

| Superblocker | 103.4 | 14.3 | 10 | 49.4 | 9.3 | 10 |

| TNFa | Saline | Ethanol | ||||

| Vehicle | 118.1 | 14.7 | 9 | 33.6 | 6.7 | 10 |

| Superblocker | 118.2 | 21.6 | 10 | 45.1 | 11.7 | 10 |

Experiment 6. Dexamethasone-induced cytokine gene expression resembles changes induced by high-dose ethanol.

Dexamethasone suppressed circulating CORT at the time of euthanasia (F(3, 35) = 12.65, p < 0.05; Figure 6). Dexamethasone increased IL-6 gene expression in the hippocampus (F(3, 35) = 3.123, p < 0.05) and PVN (F(3, 35) = 3.419, p < 0.05) , with post-hoc test showing that the 50 μg dose differed significantly from veh (p < 0.05) in hippocampus and the 500 μg dose differed significantly from veh (p < 0.05) in PVN. Dexamethasone produced a dose-dependent increase in IκBα in hippocampus (F(3, 35) = 50.84, p < 0.05) and PVN (F(3, 35) = 114, p < 0.05), with the 500 and 1000 μg doses showing significantly higher levels than vehicle or 50 μg doses (p < 0.05). IL-1β was suppressed in both hippocampus (F(3, 35) = 14.65, p < 0.05) and PVN (F(3, 35) = 14.58, p < 0.05). Each dose of dexamethasone produced a similar decrease in IL-1β (all comparisons vs. veh p < 0.05). Dexamethasone dose-dependently decreased TNFα expression in hippocampus (F(3, 35) = 15.91 p < 0.05) and PVN (F(3, 35) = 18.51, p < 0.05). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that 500 or 1000 μg/kg was sufficient to produce this suppression compared to vehicle and compared to the 50 μg dose (p < 0.05).

Experiment 7. Dexamethasone did not affect cytokine gene expression changes induced by high-dose ethanol.

Ethanol increased CORT (F(4, 35) = 26, p < 0.05; post hoc veh vs. ethanol, p < 0.05) and BECs (F(4, 35) = 1061, p < 0.05; post hoc veh vs. ethanol, p < 0.05), but dexamethasone injections did not affect the CORT or BECs of rats at the time of euthanasia (n.s. comparisons between all ethanol groups; Figure 6).

Ethanol increased IL-6 expression in the hippocampus (F(4, 35) = 4.89, p < 0.05; post hoc veh vs. ethanol, p < 0.05) but not the PVN (F(4, 35) = 1.42, p = 0.25), and dexamethasone did not modulate expression when applied with ethanol (all post-hoc p > 0.05). Ethanol increased IκBα expression in the hippocampus (F(4, 35) = 4.91, p < 0.05; post hoc veh vs. ethanol, p < 0.05) and the PVN (F(4, 35) = 5.70, p < 0.05), and dexamethasone did not modulate expression when applied with ethanol (all post-hoc p > 0.05). Ethanol decreased IL-1β expression in the hippocampus (F(4, 35) = 11.89, p < 0.05; post hoc veh vs. ethanol, p < 0.05) and the PVN (F(4, 35) = 3.41, p < 0.05), but no post hoc differences were observed (all post-hoc p > 0.05). Ethanol decreased TNFα expression in the hippocampus (F(4, 35) = 10.08, p < 0.05; post hoc veh vs. ethanol, p < 0.05) and the PVN (F(4, 35) = 6.53, p < 0.05), and dexamethasone did not modulate expression when applied with ethanol (all post-hoc p > 0.05).

Discussion

The over-arching goal of this series of experiments was to determine the extent to which ethanol-induced corticosterone release and subsequent activation of corticosteroid receptors might contribute to rapid alterations in neuroimmune gene expression evident 3 hr after ethanol administration that include increased IL-6 and IKBα and decreased expression of IL-1β and TNFα mRNA (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2014). A major strength of the present work is yet another demonstration of these systematic and time-dependent alterations in neuroimmune gene expression during acute ethanol intoxication, which replicates our previous findings (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2014, 2015; Gano et al., 2017; Vore et al., 2021). The results now show that ethanol-induced alterations in IκBα, IL-1β, and TNFα gene expression were sensitive to pharmacological manipulations targeting corticosterone signaling. The effects of these manipulations on ethanol-induced IL-6 expression were less consistent than for other neuroimmune genes tested. Surprisingly, peripheral administration of selective mineralocorticoid or glucocorticoid receptor antagonists alone (Exp 4) or in combination (Exp 5) were largely ineffective at modulating ethanol-induced changes in neuroimmune gene expression. This is potentially due to limited access to the brain, which was supported by the results of Exp 6 & 7 showing that dexamethasone, which demonstrates effective CNS distribution only at higher doses (Cole et al., 2000), recapitulated the effects of high-dose ethanol on neuroimmune gene expression.

For the most part, administration of a glucocorticoid synthesis inhibitor was highly effective in mitigating the rapid alterations in neuroimmune gene expression produced by acute ethanol challenge. Yet, the results of these experiments raise the issue of specificity of steroid synthesis blockade. For instance, metyrapone and aminoglutethimide inhibit steroidogenesis broadly, as evidenced by their ability to inhibit progesterone synthesis and release in response to stress, an effect that is likely to occur due to direct action of the drugs in the adrenal glands (Hueston & Deak, 2014b). Of course, the results of Experiment 2 and 3 in which CORT administration mimicked many effects of ethanol would seem to suggest a critical role for CORT (and not progesterone), underscoring the importance of these Experiments as tests of steroid specificity. Yet, it should be noted that CORT itself (as well as mifepristone, used in later studies) binds to progestin receptors, albeit with lower affinity than to corticosteroid receptors (Baker et al., 2013; Pichon & Milgrom, 1977). Second, these steroid synthesis inhibitors likely cross the Blood-Brain Barrier, where they might directly impact local synthesis and release of neurosteroids directly in the hippocampus, amygdala, and PVN, where gene expression measures were taken (Izumi et al., 2015). A potential role for neurosteroids could be evaluated by replicating the effects observed in Experiment 1 with bilateral adrenalectomy. Note, however, that the potential influence of anesthesia, analgesics, and tissue injury/repair processes on the neuroimmune response to ethanol make surgical adrenalectomy less preferable for the hypotheses being tested here. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that local action of metyrapone on neurosteroid synthesis in the CNS might have contributed to the effects of metyrapone observed in this study.

In the brain, CORT can bind to MR or GR receptors, both of which are expressed to varying degrees across the CNS, and particularly rich in the hippocampus. At low or basal levels of CORT, binding occurs primarily at MR, which show a higher affinity for CORT than GR (de Kloet et al., 1998). Once MR become saturated, binding occurs at high levels at the GR, which induces a different cascade of signaling events. This is the underlying mechanism for the well-studied phenomenon of negative feedback in the HPA axis (Joëls et al., 2006). Importantly, the switch from predominantly MR signaling to predominantly GR signaling also modulates the expression of cytokines, in particular IL-1β and IL-6. Specifically, Liu et al. (2018) demonstrated that in cultured microglia-like BV2 cells, low dose CORT primed later IL-1β responses to a bacterial challenge (lipopolysaccharide; LPS), and this effect was dependent on MR signaling, since it was not observed when spironolactone was also present during CORT pre-treatment. On the other hand, high doses of CORT, which presumably activated the GR system, suppressed later responses to LPS: a GR-dependent effect as demonstrated using mifepristone.

To assess receptor specificity, we aimed to test whether selective corticosteroid receptor antagonists would block ethanol-induced changes in neuroimmune gene expression. Despite replicating the effects of ethanol on neuroimmune gene expression, Experiments 4 and 5 showed no effect of MR or GR antagonists when given alone or together. Several explanations for this can be considered. First, it is possible that the doses of both drugs were simply insufficient. Although it was not possible to perform full dose response functions in the current studies, the doses of spironolactone and mifepristone used here are comparable to those that were effective in reducing ethanol self-administration (Makhijani et al., 2018, 2020; Vendruscolo et al., 2012, 2015). However, direct binding studies with peripherally-administered corticosteroid antagonists suggest only modest corticosteroid receptor occupancy in the CNS, often at or below 50% binding (Kim et al., 1998). Consistent with this, dexamethasone administered peripherally in Experiment 6-7 mimicked the effects of high-dose ethanol, with greatest efficacy at high doses that have show superior CNS penetrance (Cole et al., 2000). Dexamethasone is a selective GR agonist, and the lack of a greater magnitude of response in ethanol + dexamethasone groups compared to ethanol alone suggests a shared mechanism of GR activation. If anything, ethanol seemed to disrupt the efficacy of dexamethasone at driving neuroimmune gene expression, though the mechanisms of this disruption remain unclear. Taken together, these experiments support the interpretation that GR binding within the brain is responsible for changes in cytokine gene expression, given that GR blockade in the periphery did not modulate any of these responses.

While GR-mediated transcriptional effects are the most direct mechanistic explanation of CORT-induced changes in neuroimmune gene expression, non-genomic effects of CORT signaling may contribute to downstream transcriptional changes. Broadly speaking, evidence has shown that glucocorticoids affected protein-protein interactions upstream of translocation to the nucleus, modulate intracellular calcium concentrations, and change the function of ion channels (reviewed here: Panettieri et al., 2019). These effects did not require the glucocorticoid-receptor complex to translocate to the nucleus, and in some cases did not require binding of the glucocorticoid to the receptor at all (Yu et al., 2015). Most germane to this set of experiments which showed effects at the transcriptional level are studies which have demonstrated upstream interactions of proteins important for neuroimmune pathway activation. For example, dexamethasone impaired the ubiquitination of an upstream activator (IRAK1) of NFκB, which reduced downstream cytokine expression in human monocytes (Kong et al., 2017). Interestingly, this effect was specific to TLR9 activation of NFκB, and dexamethasone did not impair TLR4 activation of NFκB. Another set of experiments showed that neuronal nitric oxide increases due to ATP administration were potentiated by dexamethasone, likely through a direct interaction with the ATP receptor (Yukawa et al., 2005). Nitric oxide species have well documented neuroinflammatory properties which in high concentrations can contribute to neurodegeneration (reviewed here: Liy, Puzi, Jose, & Vidyadaran, 2021). Furthermore, nitric oxide seems to enhance CORT signaling in the brain as a result of inflammatory challenge, thereby potentially providing a positive feedback loop for nitric oxide signaling (Sandi & Guaza, 1995). Overall, it is clear that interactions between CORT and proteins at the membrane or within the cytosol (with or without receptor binding) could contribute to downstream neuroimmune activation. Indeed, these non-genomic effects may help explain the lack of effects of our inhibition of MR or GR (experiments 4 & 5, discussed below), but the mechanisms involved are not yet clear, especially given the apparent lack of interaction between GR agonists and TLR4 (Kong et al., 2017).

Although additional work is necessary in order to determine the mechanism of ethanol-induced and CORT-dependent alterations in neuroimmune gene expression, activation of MR by CORT has been shown to enhance NFκB signaling as measured by translocation to the nucleus of the cell (Liu et al., 2018), and NFκB signaling is thought to be implicated in many of the changes in inflammatory factors in the CNS and periphery. Our data suggest that both CORT and ethanol increase expression of IκBα which is a commonly used marker of NFκB activation, since it is transcribed early after binding of NFκB subunits to their promotor regions. However, IκBα has an anti-inflammatory effect through its masking of NFκB dimers. CORT can also act in an anti-inflammatory fashion through trans-suppression NFκB signaling (Morsink et al., 2006). One mechanism of anti-inflammatory effects of CORT is via suppression of IL-1β (Goujon et al., 1997), and our findings are in agreement with previous research demonstrating that exogenous CORT suppressed IL-1β gene expression. This was especially remarkable given that a lower dose of ethanol in Experiment 3 was sufficient to suppress IL-1β in the amygdala and PVN. This suggests that even at more typical binge-levels achieved in non-dependent individuals (80-120 mg/dl), ethanol induced CORT may reduce IL-1β signaling. On the other hand, in the experiments presented here, the most robust effects of ethanol or CORT were on IκBα gene expression, seen with much higher doses of ethanol (resulting in BEC of >300 mg/dl) akin to high intensity drinking in humans. Furthermore, IκBα expression in the amygdala was a singular instance in which low-dose ethanol and low-dose CORT created a statistically significant potentiation. Together, these data suggest that ethanol-related induction of IκBα during intoxication from high intensity drinking may be due to both NFκB activation through MR and anti-inflammatory processes set in motion by higher concentrations of CORT acting at the GR. The specificity of the IκBα and IL-6 induction to these higher doses suggests that IL-6 and other cytokines downstream of NFκB may be important for producing hypnotic and sedative effects of ethanol.

The pattern of cytokine changes observed in the current studies and in our prior work is similar to alterations in brain cytokine expression that are seen with chronic stress or glucocorticoid treatment. Research has shown that chronic stress or chronic glucocorticoid exposure enhances expression of NFκB-related genes in the brain, and current work suggests that microglial activation mediates this change in cytokine expression (Frank et al., 2019; Frank, Hershman, Weber, Watkins, & Maier, 2014; Munhoz, Sorrells, Caso, Scavone, & Sapolsky, 2010). Although effects of prior stress or glucocorticoid activation can be mild when microglia are measured in a basal state, responses to subsequent or concomitant challenges are often potentiated. This potentiated response has been termed ‘microglial priming’, which underscores the role of microglia which survive chronic challenges with stressors but change in morphology and cytokine expression profile to respond to further challenges more aggressively. Microglia in a quiescent, monitoring state are highly ramified and only express low levels of proinflammatory cytokines. With activation, they become less ramified and more amoeboid, enhance cytokine expression, and engage in more phagocytic activity. Some recent work has been done to illuminate the mechanisms of microglial priming. Frank et al (2014) demonstrated that chronic CORT upregulation resulted in enhanced activation of NFκB and the NLRP3 inflammasome in hippocampal microglia, and that these microglia were primed to respond to an ex-vivo challenge with LPS as measured by increases in IL-1β expression. The NLRP3 inflammasome is a necessary mediator of IL-1β expression, and Busillo et al. (2011) demonstrated that glucocorticoid exposure upregulated the NLRP3 inflammasome. In the case of microglial priming following glucocorticoid activation, it appears that NLRP3 upregulation is a result of disinhibition of microglia through a high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and CD200R1 mechanism. Frank et al. (2019) were able to bi-directionally modulate induction of HMGB1 with administration of mifepristone or CORT in vivo and in ex vivo microglia cultures, such that higher CORT binding to GR was found to enhance HMGB1 expression. In ex vivo microglia CORT suppressed levels of CD200R1, which is expressed on microglia and is responsible for maintaining a quiescent state. Therefore, it is likely that GR activation disinhibits microglia through downregulation of CD200R1 and leads to downstream activation of HMGB1 and NLRP3. Interestingly, priming of the immune response to stress may have divergent mechanisms in male and female rats; the microglial priming mechanism described above held true for males but not females exposed to stress (Fonken et al., 2018). This sex-specific effect of microglial priming in males makes the interpretation of the current work more straightforward, but also raises the question of how females respond differently to CORT and ethanol challenges. This question merits additional exploration especially given the fact that similar induction of cytokines is seen in both sexes in our ethanol paradigms and in priming paradigms, yet clearly different mechanisms are involved.

Microglial priming of the immune response has also been observed in various ethanol exposure paradigms. Long-lasting priming effects have been observed with neonatal ethanol exposure for example, where pups exposed to ethanol had microglia that were more responsive to LPS in terms of IL-6 and TNFα expression in adulthood (Chastain et al., 2019). This effect may be due to epigenetic effects in the promotor regions of proinflammatory genes through enhancement of H3K9ac, although the ability of this priming to transcend generations has not yet been tested. Studies in the Nixon lab, among others, have shown that binge-like ethanol exposure produces surprisingly mild morphological and activational changes in microglia (Simon Alex Marshall, Geil, & Nixon, 2016; Peng, Nickell, Chen, Mcclain, & Nixon, 2017). However, these mild but observable effects were more pronounced when the ethanol binge was given during adolescence (McClain et al., 2011), and still produce a remarkable priming effect to later challenge (Marshall et al., 2016). The response to a second ethanol binge of 4 days a week after the first 4-day binge was marked by enhanced TNFα expression and an enhancement of microglial proliferation (Marshall et al., 2016). In the case of ethanol exposure, the number of newborn microglia may contribute to the priming of the neuroimmune system, as microglia proliferated more after a binge exposure in adolescence, and these microglia survived into adulthood (McClain et al., 2011). This idea is supported by data showing that there were robust changes in morphology and number of microglia accompanied by mild changes in phenotypic protein markers of activation after binge (Peng et al., 2017); therefore it may be possible that microglia generated as a result of binge ethanol have a more activated M1 or M2 phenotype, but this discrimination has yet to be tested. In any case, it is clear that even acute binge-like exposures to ethanol can have immediate effects on neuroimmune gene expression that may belie priming of microglia in male rats to further immune insults and stressors. Our evidence that these neuroimmune effects rely at least partially on CORT signaling may accelerate progress in delineating mechanisms responsible for such priming. The extent to which a single high dose of ethanol primes the immune response when given in adulthood vs. adolescence and the dependence on the aforementioned pathways are promising avenues of further study.

The ability of ethanol to prime the immune system through activation of the glucocorticoid system may help explain the therapeutic effects on AUD of drugs like mifepristone which inhibit glucocorticoid signaling. Briefly, chronic inhibition of GR by mifepristone in rats during chronic intermittent exposure ethanol prevented escalations in drinking (Vendruscolo et al., 2012, 2015). Recently, other variations of specific GR receptor antagonists were shown to curb drinking in rodents as well (McGinn et al., 2021). Although some of these more specific GR antagonists have shown greater effects in suppressing drinking (Vendruscolo et al., 2015), mifepristone has been approved for human trials and has been effective in treating drinking in AUD (Vendruscolo et al., 2015). Our results in these experiments suggest that perhaps more than previously expected, CORT effects on drinking and AUD may be more intimately linked to the literature which shows that immune activation modulates drinking in rodents. For example, infusion of IL-1 receptor antagonist into the basolateral amygdala was sufficient to reduce ethanol consumption in a drinking in the dark paradigm in mice (Marshall et al., 2016). On the other hand, global deletion of the IL-1 receptor antagonist in mice greatly reduced drinking and ethanol preference, and similar but less profound effects were seen with deletion of other immune genes such as IL-6 (Blednov et al., 2012). Obviously, the modulation of drinking by cytokines can have site-specific effects that may differ as a function of dose (of gene or cytokine), duration of change, and of course exposure to repeated cycles of ethanol. Ethanol consumption and the neuroimmune response to it must be understood as a bidirectional relationship that may change with every ethanol exposure, considering the profound priming effects discussed above.

Overall, it is well understood that the interaction between glucocorticoids (stress), ethanol, and the neuroimmune system is critical in producing drinking behavior and the adverse neurological consequences of long-term ethanol exposure. Yet, until now, to our best knowledge, there was no experimental evidence of the involvement of CORT in ethanol-associated alterations in neuroimmune gene expression. We view the results of this series of experiments as a first step in defining the intricate relationship between the neuroimmune alterations and ethanol-induced CORT signaling. We highlight the role of GR signaling in producing these effects, but the involvement of MR and the non-genomic vs. genomic effects of GR signaling remain to be determined. Overall, more work is needed for understanding the exact mechanism of CORT-dependent cytokine changes following acute ethanol challenge, and how cytokine responses change with repeated administration, in order to illuminate specific molecular targets for therapeutic intervention.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants P50AA017823 (TD) and T32AA025606 (TMB). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the above stated funding agencies. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Baker ME, Funder JW, & Kattoula SR (2013). Evolution of hormone selectivity in glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 137, 57–70. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barney TM, Vore AS, Gano A, Mondello JE, & Deak T (2019). The influence of central interleukin-6 on behavioral changes associated with acute alcohol intoxication in adult male rats. Alcohol, 79. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnum CJ, Blandino P, & Deak T (2007). Adaptation in the corticosterone and hyperthermic responses to stress following repeated stressor exposure. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 19(8), 632–642. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01571.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnum CJ, Eskow KL, Dupre K, Blandino P, Deak T, & Bishop C (2008). Exogenous corticosterone reduces l-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in the hemi-parkinsonian rat: Role for interleukin-1β. Neuroscience, 156(1), 30–41. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandino P, Barnum CJ, & Deak T (2006). The involvement of norepinephrine and microglia in hypothalamic and splenic IL-1β responses to stress. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 173(1–2), 87–95. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandino P, Barnum CJ, Solomon LG, Larish Y, Lankow BS, & Deak T (2009). Gene expression changes in the hypothalamus provide evidence for regionally-selective changes in IL-1 and microglial markers after acute stress. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 23(7), 958–968. 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck HM, Hueston CM, Bishop CMC, & Deak T (2011). Enhancement of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis but not cytokine responses to stress challenges imposed during withdrawal from acute alcohol exposure in Sprague-Dawley rats. Psychopharmacology, 218(1), 203–215. 10.1007/s00213-011-2388-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MA, Kim PJ, Kalman BA, & Spencer RL (2000). Dexamethasone suppression of corticosteroid secretion: Evaluation of the site of action by receptor measures and functional studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 10.1016/S0306-4530(99)00045-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Vreugdenhil E, Oitzl MS, & Joëls M (1998). Brain Corticosteroid Receptor Balance in Health and Disease*. Endocrine Reviews, 19(3), 269–301. 10.1210/edrv.19.3.0331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnadieu-Rigole H, Mura T, Portales P, Duroux-Richard I, Bouthier M, Eliaou J-F, Perney P, & Apparailly F (2016). Effects of alcohol withdrawal on monocyte subset defects in chronic alcohol users. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 100(5), 1191–1199. 10.1189/jlb.5a0216-060rr [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnadieu-Rigole H, Pansu N, Mura T, Pelletier S, Alarcon R, Gamon L, Perney P, Apparailly F, Lavigne JP, & Dunyach-Remy C (2018). Beneficial Effect of Alcohol Withdrawal on Gut Permeability and Microbial Translocation in Patients with Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 42(1), 32–40. 10.1111/acer.13527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doremus-Fitzwater, Buck HM, Bordner K, Richey L, Jones ME, & Deak T (2014). Intoxication- and Withdrawal-Dependent Expression of Central and Peripheral Cytokines Following Initial Ethanol Exposure. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38(8), 2186–2198. 10.1111/acer.12481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doremus-Fitzwater, Gano A, Paniccia JE, & Deak T (2015). Male adolescent rats display blunted cytokine responses in the CNS after acute ethanol or lipopolysaccharide exposure. Physiology and Behavior, 148, 131–144. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.02.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AJ, Swiergiel AH, & De Beaurepaire R (2005). Cytokines as mediators of depression: What can we learn from animal studies? In Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S, Little HJ, Richardson HN, & Vendruscolo LF (2015). Divergent regulation of distinct glucocorticoid systems in alcohol dependence. Alcohol, 49(8), 811–816. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson EK, Grantham EK, Warden AS, & Harris RA (2019). Neuroimmune signaling in alcohol use disorder. In Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior (Vol. 177, pp. 34–60). Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 10.1016/j.pbb.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MG, Annis JL, Watkins LR, & Maier SF (2019). Glucocorticoids mediate stress induction of the alarmin HMGB1 and reduction of the microglia checkpoint receptor CD200R1 in limbic brain structures. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 80, 678–687. 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gano, Doremus-Fitzwater, & Deak. (2017). A cross-sectional comparison of ethanol-related cytokine expression in the hippocampus of young and aged Fischer 344 rats. Neurobiology of Aging, 54, 40–53. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gano, Pautassi RM, Doremus-Fitzwater TL, Barney TM, Vore AS, & Deak T (2019). Conditioning the neuroimmune response to ethanol using taste and environmental cues in adolescent and adult rats. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 10.1177/1535370219831709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goujon E, Layé S, Parnet P, & Dantzer R (1997). Regulation of cytokine gene expression in the central nervous system by glucocorticoids: Mechanisms and functional consequences. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 22(SUPPL. 1). 10.1016/S0306-4530(97)00009-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RA, Bajo M, Bell RL, Blednov YA, Varodayan FP, Truitt JM, de Guglielmo G, Lasek AW, Logrip ML, Vendruscolo LF, Roberts AJ, Roberts E, George O, Mayfield J, Billiar TR, Hackam DJ, Mayfield RD, Koob GF, Roberto M, & Homanics GE (2017). Genetic and Pharmacologic Manipulation of TLR4 Has Minimal Impact on Ethanol Consumption in Rodents. The Journal of Neuroscience, 37(5), 1139–1155. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2002-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez RV, Puro AC, Manos JC, Huitron-Resendiz S, Reyes KC, Liu K, Vo K, Roberts AJ, & Gruol DL (2016). Transgenic mice with increased astrocyte expression of IL-6 show altered effects of acute ethanol on synaptic function. Neuropharmacology, 103, 27–43. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi Y, O’Dell KA, & Zorumski CF (2015). Corticosterone enhances the potency of ethanol against hippocampal long-term potentiation via local neurosteroid synthesis. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 9(JULY). 10.3389/FNCEL.2015.00254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM (2008). Heavy Episodic Drinking: Determining the Predictive Utility of Five or More Drinks. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson L, & Sapolsky R (1991). The role of the hippocampus in feedback regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Endocrine Reviews. 10.1210/edrv-12-2-118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joëls M, Pu Z, Wiegert O, Oitzl MS, & Krugers HJ (2006). Learning under stress: how does it work? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(4), 152–158. 10.1016/j.tics.2006.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PJ, Cole MA, Kalman BA, & Spencer RL (1998). Evaluation of RU28318 and RU40555 as selective mineralocorticoid receptor and glucocorticoid receptor antagonists, respectively: Receptor measures and functional studies. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 67(3), 213–222. 10.1016/S0960-0760(98)00095-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HN, & Olive MF (2004). The glucocorticoid receptor antagonist mifepristone reduces ethanol intake in rats under limited access conditions. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(8), 999–1003. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F, Liu Z, Jain VG, Shima K, Suzuki T, Muglia LJ, Starczynowski DT, Pasare C, & Bhattacharyya S (2017). Inhibition of IRAK1 Ubiquitination Determines Glucocorticoid Sensitivity for TLR9-Induced Inflammation in Macrophages. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950), 199(10), 3654–3667. 10.4049/JIMMUNOL.1700443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche J, Gasbarro L, Herman JP, & Blaustein JD (2009). Reduced behavioral response to gonadal hormones in mice shipped during the peripubertal/adolescent period. Endocrinology, 150(5), 2351–2358. 10.1210/en.2008-1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JJ, Mustafa S, Barratt DT, & Hutchinson MR (2018). Corticosterone preexposure increases NF-κB translocation and sensitizes IL-1β responses in BV2 microglia-like cells. Frontiers in Immunology, 9(JAN). 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liy PM, Puzi NNA, Jose S, & Vidyadaran S (2021). Nitric oxide modulation in neuroinflammation and the role of mesenchymal stem cells. Experimental Biology and Medicine (Maywood, N.J.), 246(22), 2399–2406. 10.1177/1535370221997052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhijani VH, Irukulapati P, Van Voorhies K, Fortino B, & Besheer J (2020). Central amygdala mineralocorticoid receptors modulate alcohol self-administration. Neuropharmacology, 181(May), 108337. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhijani VH, Van Voorhies K, Besheer J, Biochem P, & Author B (2018). The mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone reduces alcohol self-administration in female and male rats HHS Public Access Author manuscript. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 175, 10–18. 10.1016/j.pbb.2018.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn MA, Tunstall BJ, Schlosburg JE, Gregory-Flores A, George O, de Guglielmo G, Mason BJ, Hunt HJ, Koob GF, & Vendruscolo LF (2021). Glucocorticoid receptor modulators decrease alcohol self-administration in male rats. Neuropharmacology, 188. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamotot S, Makit M, Schmittt MJ, Hatanakat M, & Vermat IM (1994). Tumor necrosis factor a-induced phosphorylation of IKBa is a signal for its degradation but not dissociation from NF-KB (signal transduction/proteases/regulation/transcription). Biochemistry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone P, Scognamiglio P, Canestrelli B, Serino I, Monteleone AM, & Maj M (2011). Asymmetry of salivary cortisol and α-amylase responses to psychosocial stress in anorexia nervosa but not in bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine. 10.1017/S0033291711000092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsink MC, Steenbergen PJ, Vos JB, Karst H, Joëls M, De Kloet ER, & Datson NA (2006). Acute activation of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors results in different waves of gene expression throughout time. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 18(4), 239–252. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupane SP (2016). Neuroimmune interface in the comorbidity between alcohol use disorder and major depression. In Frontiers in Immunology (Vol. 7, Issue DEC, p. 1). 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornelas LC, & Keele NB (2018). Sex Differences in the Physiological Response to Ethanol of Rat Basolateral Amygdala Neurons Following Single-Prolonged Stress. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 12, 219. 10.3389/fncel.2018.00219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panettieri RA, Schaafsma D, Amrani Y, Koziol-White C, Ostrom R, & Tliba O (2019). Non-genomic Effects of Glucocorticoids: An Updated View. In Trends in Pharmacological Sciences (Vol. 40, Issue 1, pp. 38–49). NIH Public Access. 10.1016/j.tips.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RR, Khom S, Steinman MQ, Varodayan FP, Kiosses WB, Hedges DM, Vlkolinsky R, Nadav T, Polis I, Bajo M, Roberts AJ, & Roberto M (2019). IL-1β expression is increased and regulates GABA transmission following chronic ethanol in mouse central amygdala. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 75, 208–219. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichon MF, & Milgrom E (1977). Characterization and Assay of Progesterone Receptor in Human Mammary Carcinoma. Cancer Research, 37(2), 464–471. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/832270/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotsky PM, & Sawchenko PE (1987). Hypophysial-portal plasma levels, median eminence content, and immunohistochemical staining of corticotropin-releasing factor, arginine vasopressin, and oxytocin after pharmacological adrenalectomy. Endocrinology, 120(4), 1361–1369. 10.1210/endo-120-4-1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan N, He L, Lai W, Shen T, & Herkenham M (2000). Induction of IκBα mRNA expression in the brain by glucocorticoids: A negative feedback mechanism for immune-to-brain signaling. Journal of Neuroscience, 20(17), 6473–6477. 10.1523/jneurosci.20-17-06473.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]