Abstract

This cohort study examines the demographic characteristics associated with the incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma from 2000 to 2018 in Louisiana.

Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) was estimated as 6.4 cases per million individuals per year.1 Previous reports have documented a worldwide increase in CTCL incidence.2 We assessed the incidence and demographic patterns of CTCL in Louisiana.

Methods

Tulane Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived informed consent because deidentified data were used. Data sources were a Louisiana tumor registry and electronic health records from 2 New Orleans clinics. Sex; age; race and ethnicity; age at diagnosis; year of diagnosis; and CTCL primary site, histologic codes, and grade and behavior data were collected. Census data from 2000 and 2010 were used for all population analyses.

Mean annual CTCL incidence was reported as cases per million persons, and incidence rate over time was calculated using linear regression. Multivariate ordinal regression was used to test whether demographic characteristics and primary residency (urban vs rural) were factors in disease stage, a clinical severity surrogate. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess whether age, race and ethnicity, and sex were factors in CTCL subtype. R was used for statistical analysis.

Results

We identified 774 patients (mean [SD] age, 59.14 [15.28] years; 415 women [53.6%]) (Table). Of these patients, 356 (46.0%) had mycosis fungoides. African American patients vs White patients, had an earlier mean (SD) age at diagnosis (54.4 [14.9] years vs 61.8 [14.9] years; P < .001) and were more likely to be diagnosed before age 40 years (16.1% vs 9.1%; odds ratio [OR], 2.85; 95% CI, 1.76-4.63) and between 40 and 59 years (47.2% vs 30.4%; OR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.89-3.69). Among African American patients, men were significantly less likely than women to be diagnosed with CTCL (OR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.49-0.92). Compared with White patients, African American patients exhibited later disease stage (≥II) at time of diagnosis (7.9% vs 3.6%; OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.26-2.99).

Table. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With CTCL in Louisiana.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) (n = 774) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Mean (SD) | 59.14 (15.28) |

| Median (IQR) | 60 (49-70) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 415 (53.6) |

| Male | 359 (46.3) |

| Race and ethnicitya | |

| African American | 267 (34.5) |

| Chinese | 2 (0.3) |

| Native American | 2 (0.3) |

| Vietnamese | 1 (0.1) |

| White | 496 (64.1) |

| Otherb | 6 (0.8) |

| CTCL subtype | |

| MF | 356 (46.0) |

| Primary CTCL, NOS | 414 (53.5) |

| Sezary syndrome | 4 (0.5) |

| CTCL clinical stage | |

| I | 392 (50.7) |

| II | 39 (5.0) |

| III | 16 (2.1) |

| IV | 67 (8.7) |

| Unstageable | 260 (33.6) |

Abbreviations: CTCL, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; MF, mycosis fungoides; NOS, not otherwise specified.

Race and ethnicity were indicated in data sources.

Other category included Filipino, and South Asian individuals.

Multivariate ordinal regression showed that African American patients with CTCL had 1.9 greater odds of higher disease stage (III-IV) than White patients (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.26-3.04); regional differences were not factors in disease stage. Age and race and ethnicity were not significantly associated with CTCL subtypes. Annual incidence was 8.66 per million persons, and this rate was highest among those aged 60 to 69 years. We found no significant difference in incidence rates among African American patients vs White patients (9.4 vs 8.8 per million persons; P = .97). Compared with recent national CTCL incidence (6.4 per million persons) and using a 2-sample t test, we found no significant difference from incidence in Louisiana.

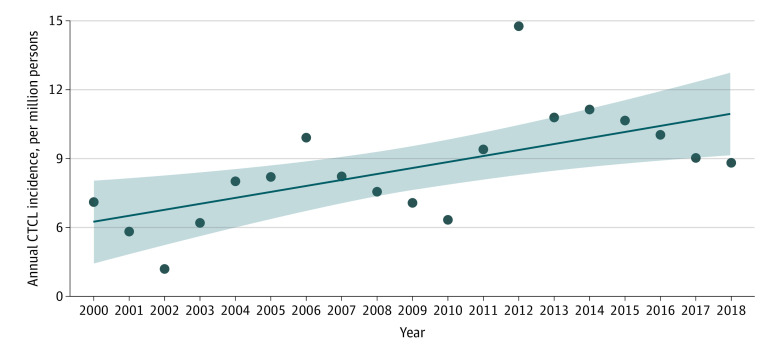

Linear regression analysis showed a significant increase in CTCL incidence over time (R2 = 0.35; coefficient of year, 0.26; P = .005) (Figure). These results suggest the 35% rate variance was associated with time, with a 0.26 annual incidence increase.

Figure. Pattern of Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma (CTCL) Incidence From 2000 to 2018.

Discussion

From 2000 to 2018, CTCL incidence in Louisiana increased by a mean 0.26 per million persons per year. Similar increasing incidence patterns have been reported in Texas, Georgia, Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania), and Sweden.3 Although the cause of this pattern is unclear, CTCL clustering in multiple regions suggests environmental triggers.

Existing data support the finding that African American patients had earlier age and later disease stage at diagnosis.4 Even when adjusted for multiple variables, African American race and ethnicity was an independent factor in higher disease stage. No association was found between primary residency and disease stage; age and race and ethnicity were not associated with CTCL subtypes. Later-stage diagnosis could be associated with heterogeneous CTCL presentation (eg, as mimickers of atopic dermatitis or psoriasis).

Study limitations were potential CTCL misclassification as peripheral T-cell lymphoma, absence of confounder data, and county-level instead of Census tract–level data analysis. Improvement in physician detection of CTCL may be a factor in the increasing incidence pattern. Disproportionate burden of disease among African American patients is concerning and merits investigation.

References

- 1.Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973-2002. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(7):854-859. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.7.854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghazawi FM, Alghazawi N, Le M, et al. Environmental and other extrinsic risk factors contributing to the pathogenesis of cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL). Front Oncol. 2019;9:300. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghazawi FM, Netchiporouk E, Rahme E, et al. Comprehensive analysis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) incidence and mortality in Canada reveals changing trends and geographic clustering for this malignancy. Cancer. 2017;123(18):3550-3567. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nath SK, Yu JB, Wilson LD. Poorer prognosis of African-American patients with mycosis fungoides: an analysis of the SEER dataset, 1988 to 2008. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14(5):419-423. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2013.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]