Summary

Perioperative hypotension has been repeatedly associated with organ injury and worse outcome, yet many interventions to reduce morbidity by attempting to avoid or reverse hypotension have floundered. In part, this reflects uncertainty as to what threshold of hypotension is relevant in the perioperative setting. Shifting population-based definitions for hypertension, plus uncertainty regarding individualised norms before surgery, both present major challenges in constructing useful clinical guidelines that may help improve clinical outcomes. Aside from these major pragmatic challenges, a wealth of biological mechanisms that underpin the development of higher blood pressure, particularly with increasing age, suggest that hypotension (however defined) or lower blood pressure per se does not account solely for developing organ injury after major surgery. The mosaic theory of hypertension, first proposed more than 60 yr ago, incorporates multiple, complementary mechanistic pathways through which clinical (macrovascular) attempts to minimise perioperative organ injury may unintentionally subvert protective or adaptive pathways that are fundamental in shaping the integrative host response to injury and inflammation. Consideration of the mosaic framework is critical for a more complete understanding of the perioperative response to acute sterile and infectious inflammation. The largely arbitrary treatment of perioperative blood pressure remains rudimentary in the context of multiple complex adaptive hypertensive endotypes, defined by distinct functional or pathobiological mechanisms, including the regulation of reactive oxygen species, autonomic dysfunction, and inflammation. Developing coherent strategies for the management of perioperative hypotension requires smarter, mechanistically solid interventions delivered by RCTs where observer bias is minimised.

Keywords: blood pressure, cardiac, hypertension, inflammation, mosaic theory of hypertension, organ dysfunction, renal

Editor's key points.

-

•

Perioperative hypotension is strongly associated with the development of organ injury, but it is difficult to define on an individualised basis. Interventional trials have not (as yet) demonstrated that avoiding hypotension reduces perioperative morbidity.

-

•

This review considers whether perioperative hypotension is a biomarker, rather than a direct mediator, of perioperative organ injury. Key pathologic mechanisms that contribute to the development of higher blood pressure may also cause perioperative organ injury.

Monitoring arterial blood pressure remains ‘mission central’ in perioperative practice, yet it continues to garner scrutiny and controversy. The capture of patient-specific risks combined with physiological measurements in more than 800 000 patients has unequivocally identified that lower-than-normal arterial blood pressure measured during and after surgery is associated with poorer postoperative outcomes.1 Even transient declines or brief intraoperative periods2 of hypotension appear to have similar time-weighted associations with myocardial injury and mortality as postoperative hypotensive events.3,4 However, because hypotension has been defined so variably in 42 (mostly retrospective) studies involving heterogenous surgery types, both the incidence5 of hypotension and the strength of association with (variably defined) morbidity6 remain unclear.7 Treatments for hypotension that are mechanistically rational require, not only a clinically plausible threshold or indication, but a solid evidence-based outcome that confers benefit to the patient.8

Here, we consider an alternative hypothesis to low blood pressure alone causing organ injury. This hypothesis directly addresses why studies demonstrating such impressively repeatable associations between hypotension and poorer outcomes have failed to find a clearly definable, useful clinical threshold value to guide management of blood pressure. We posit that current perioperative strategies overlook key biological mechanisms underpinning the control of blood pressure9 that, in turn, have a direct impact on the development of organ injury. In other words, the frequently brief and treated occurrence of hypotension (however defined), unless extreme and prolonged, is really a biomarker for injurious pathophysiological substrate(s) underpinning dysregulated blood pressure control. We consider multiple strands of evidence that challenge several aspects of the current perioperative paradigm, ranging from relentless progress in the management of (non-operative) blood pressure through to fundamental cellular mechanisms regulating blood pressure. These strands generate an alternative hypothesis that reconciles apparently disparate perioperative associations with outcome, while providing new, clinically testable lines of enquiry. In short, equipping clinicians with a more sophisticated understanding of both the reasons for, and consequences of, perioperative ‘hypotension’ may help reduce morbidity.

Interventional trials targeting perioperative hypotension have not improved outcome

Profound sustained hypotension results in subclinical or overt organ injury.10 Above extremely low blood pressures, a common perioperative management strategy has centred on the assumption that certain arterial pressure levels may result in residual under-perfusion. However, hypotension does not necessarily lead to organ hypoperfusion and may preserve or even increase organ perfusion differentially, depending on the relative changes in perfusion pressure, the regional vascular resistance, and autoregulation.11 The association between intraoperative blood pressure and organ injury primarily stems from retrospective observational studies, frequently reflecting local practice that – unsurprisingly – is widely variable and inherently biased.

Eight interventional trials in the perioperative and critical care setting have directly sought to explore whether limiting hypotension reduces end-organ injury (Table 1).12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Two large randomised perioperative trials failed to find any impact on mortality of reversing hypotension (using a pre-defined values) by remotely alerting clinicians to take action.13,20 The Intraoperative Norepinephrine to Control Arterial Pressure (INPRESS) study, which aimed to maintain systolic blood pressure within 10% of preoperative values after optimisation of preload, failed to reduce clinically defined cardiovascular complications.15 Data demonstrating the individualised successful achievement of maintaining systolic blood pressure within 10% of preoperative levels were not provided. The unblinded composite primary outcome required SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome) score (an outdated, flawed measure).21 There were no differences noted in clinical cardiorenal outcomes, with only fewer episodes of altered conscious level accounting for the overall (positive) outcome in the ‘normalised’ blood pressure group. Similarly, a semi-blind composite outcome of myocardial injury, infarction, and/or acute kidney injury was similar between patients randomised to an intraoperative MAP target of ≥60 vs ≥75 mm Hg.19 Notably, despite the intervention resulting in both fewer episodes and shorter exposure to MAP <65 mm Hg, longer duration of cumulative intraoperative MAP <65 mm Hg remained associated with a higher rate of cardiorenal complications.19

Table 1.

Interventional perioperative trials in adults. BIS, bispectral index; ITT, intention to treat; MAC, minimum alveolar concentration; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; POCD, postoperative cognitive dysfunction; postop, postoperatively; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

| Trial (first author, year) | Design/allocation | Minimisation | Patients n (centres) | Setting | Inclusion criteria | Hypertension | Intervention | Control | Primary outcome | Masked | ITT | Outcome | Intervention effective? (P) | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McCormick,12 2016 | RCT (1:1) | None | 19092 (1) | Noncardiac | Adults undergoing noncardiac surgery with BIS monitoring | 8275 | Intraoperative alert when MAP <75 and BIS <45. | No alerts | Death (90 days postop) | N | Unclear | 1.4% vs 1.3% | No (P=0.30) | Unclear if intention-to-treat analysis or per-protocol analysis. Non-standardised response to intraoperative alert. |

| Sessler,13 2019 | RCT (1:1) | None | 7569 (1) | Noncardiac | Adults undergoing noncardiac surgery under general anaesthesia with BIS monitoring | 4882 | Intraoperative alert when ‘triple low’ MAP <75, BIS <45 MAC <0.8. | No alerts | Death (90 days postop) | Y | Unclear | 8.3% vs 7.3% | No (P=0.12) | Unclear if intention-to-treat analysis or per-protocol analysis. Non-standardised response to intraoperative alert. |

| Wijnberge,14 2020 | RCT (1:1) | None | 68 (1) | Noncardiac | Adults undergoing elective noncardiac surgery with indication for invasive arterial blood Monitoring |

unclear | Machine learning-derived early warning system with haemodynamic guidance and treatment protocol targeting vasoplegia, hypovolaemia or impaired cardiac contractility. | Standard care | MAP <65 (time-weighted average [TWA]) | N | Unclear | TWA: 0.1 vs 0.44 mm Hg | Yes (P=0.001) | No clinical/patient-centred outcomes. Proprietary hardware for decision-support tool. |

| Futier,15 2017 | RCT (1:1) | None | 298 (9) | Noncardiac | >2 h surgery ↑ AKI risk |

240 | Targeted management of systolic blood pressure within 10% of resting SBP using norepinephrine infusion. | Standard care. Treatment of any decrease in SBP <80 mm Hg or <40% from resting SBP using 6 mg boluses of ephedrine. | SIRS + >1 organ dysfunction within 7 days postop. |

Not blinded- data collection during surgery. Blinded data collection after surgery. | Modified ITT. | RR: 0.73 (0.56–0.94) | Yes (P=0.02) | Use of ephedrine as first line vasopressor for standard care. Duration of hypotension not recorded. |

| Langer,16 2019 | RCT (1:1) | Age Education Duration of surgery |

101 (1) and 33 age-matched controls | Noncardiac | Age >75 y ASA <4 |

66 | Personalised blood pressure target based on 90% of baseline MAP. | Liberal intraoperative blood pressure management with no target MAP. | POCD (up to 3 months postop) | Anaesthesiologists were unblinded. Research personnel and patients were blinded. | Unclear Differences in risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction were compared using relative risk. | RR: 1.52 (0.41–6.3) | No (P=0.56) | Unclear if intention-to-treat analysis. Presented as a pilot study – may be underpowered to detect a difference in the primary outcome. |

| Wu,17 2017 | RCT (1: 1: 1) | None | 678 (3) | Noncardiac | GI surgery Hypertension (SBP >140 mm Hg, DBP >90 mm Hg, or both) | 678 | Targeted management of mean arterial pressure using vasoactive medications (three group: 65–79, 80–95, and 96–110 mm Hg) | Targeted management of mean arterial pressure using vasoactive medications (three groups: 65–79, 80–95, and 96–110 mm Hg) | Acute kidney injury (50% or 0.3 mg dl−1 increase in creatinine) during first 7 days after surgery. | N | Unclear | 6.3% in MAP 80–95 13.5% MAP 65–79 mm Hg 12.9% in MAP 96–110 mm Hg groups |

Yes (P<0.001) | Unadjusted analysis. Unclear if intention-to-treat analysis or per-protocol analysis. |

| Lamontagne,18 2020 | RCT (1:1). | 2463 (65) | ICU | Age >65 y vasodilatory hypotension | 1187 | Vasopressor therapy targeted to a MAP of 60–65 mm Hg (permissive hypotension) | Vasopressor therapy according to usual care (at the discretion of the treating clinicians) | Death (90 days after randomisation) | Not blinded. | Yes | 41% vs 43.8% | No (P=0.15). | Fisher's exact test used to compare between group differences in the primary outcome. Attributable mortality was not adjudicated | |

| Wanner,19 2021 | RCT (1:1). | >45 yr | 458 (1) | Noncardiac | History of coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, congestive cardiac failure, undergoing major vascular surgery, or fulfilment of any three of the seven Lee criteria | Not stated | Intraoperative MAP >75 mm Hg | Intraoperative MAP >60 mm Hg | Acute myocardial injury on postoperative days 0–3 and/or 30 day MACE/acute kidney injury | Not blinded. | ITT | 48% vs 52% | No risk difference –4.2%; 95% CI, –13%–5% | Composite outcome |

In contrast, in 2600 hypotensive patients requiring critical care for established organ dysfunction, incipient organ dysfunction, or both, relative permissive hypotension targeting a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg defined a priori was associated with lower mortality (adjusted odds ratio=0.82; 95% confidence level [CI], 0.68–0.98).18 Pre-specified subgroup analyses in the 65 trial found that relative permissive hypotension was associated with lower mortality in chronically hypertensive patients, with reduced exposure to vasopressor therapy. Taken together, these data suggest that blood pressures below hypotension thresholds as currently defined may not be harmful. Moreover, the finding that a widely held MAP threshold for harm persists despite intervention19 suggests that hypotension serves as a biomarker for other pathologic processes resulting in organ injury. Moreover, attempts to reverse hypotension through vasopressor therapy may unmask adverse unintended consequences in vulnerable patients, including bacterial overgrowth, biofilm formation,22 and host immunosuppression.23,24 These studies reinforce the notion that most clinicians are unclear as to when, or how, to treat critical hypotension.

Defining perioperative hypotension is impossible without organ and patient-specific norms

No studies examining perioperative management of blood pressure have defined preoperative blood pressure in a systematic manner. It is highly unlikely that the process of preoperative assessment adequately captures an accurate picture of an individual's blood pressure, as evidenced by the myriad of clinically significant endotypes of hypertension (Table 2). This is not intended as a criticism of busy perioperative practitioners, but rather a commentary on the limitations of single clinic measurements of arterial blood pressure, which are rarely reliable. To put this into a contemporary perspective, >80% had a preoperative systolic blood pressure >120 mm Hg in VISION-UK (Supplementary data).

Table 2.

Defining hypertension: estimated prevalence and outcomes. All outcomes compared with normotensive comparator group, unless stated otherwise. ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure measurement; 95% CI, confidence interval; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, hazard ratio; IDHOCO, International Database of HOme blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome; JAMP, Japan Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring Prospective; J-HOP, Japan Morning Surge-Home Blood Pressure; OR, odds ratio; PAMELA, Pressione Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SPRINT, Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial; STEP, Strategy of Blood Pressure Intervention in the Elderly Hypertensive Patients.

| Category | Definition | Measure | Estimate of prevalence (%) | Landmark studies (no. of patients) | CV outcomes OR (95% CI) or HR∗ | Mortality (OR or HR∗) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated systolic | >140 mm Hg SBP | Clinic/ABPM | 1.8–6 | SPRINT (n=9361) STEP (n=8511) |

0.73 (0.63–0.86)∗ 0.72 (0.56–0.93)∗ |

0.75 (0.61–0.92)∗ 0.72 (0.39–1.32)∗ |

| White coat hypertension | >130 mm Hg SBP or >80 mm Hg DBP | ABPM | 10–15 | PAMELA (n=3200)28 | 1.4 [1.03–2.0] | 1.3 [1.1–1.7]∗ |

| Masked hypertension | >140 mm Hg SBP | ABPM | 9–17 | IDHOCO (n=661)29 | 2.0 (1.5–2.7) | 1.4 (1.03–2.0) |

| Isolated nocturnal hypertension | >140 mm Hg systolic | ABPM | 6–11 | J-HOP (n=2545)30 | 1.2 [1.1–1.4]∗ | 1.3 (1.01–1.7) |

| Non-dipping pattern | >140 mm Hg systolic | ABPM | ∼41 (untreated BP) | JAMP (n=6539)31 Spanish Registry (n=8384)32 |

1.48 [1.05–2.08] | – |

∗ indicates hazard ratio rather than odds ratio.

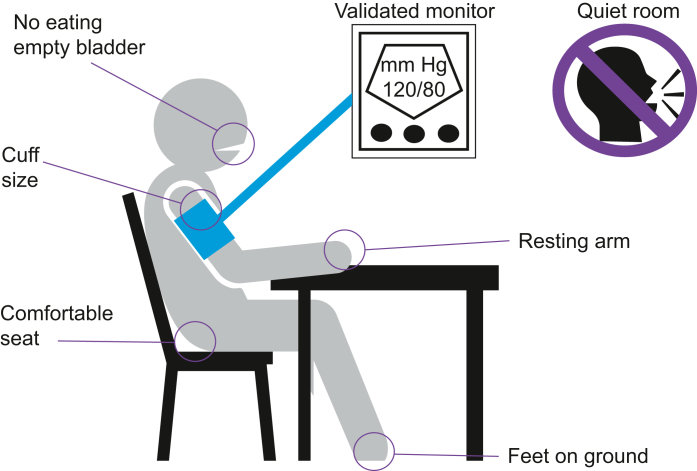

Robust standardised methodology has been developed over many years to remove important clinically relevant confounders from interfering with the accurate assessment of blood pressure, including diurnal variation (Fig. 1).25 Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring predicts fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events and stroke, independently of clinic measurements.26 Consequently, community-based management of essential hypertension is driven by extensively researched, diagnostic guidelines27 that bear little resemblance to usual perioperative practice. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring has identified several endotypes associated with very different cardiometabolic prognoses of particular relevance to the perioperative period (Table 2).28, 29, 30, 31, 32 Masked and isolated nocturnal hypertension are associated with a higher cardiovascular and all-cause mortality risk.29 Taken together, typical preoperative assessment estimation of blood pressure is of limited value. The individual blood pressure readings are not of themselves inaccurate but, with the exception of extreme values, are not of help in identifying patients with poorly controlled blood pressure. This assertion is reinforced by a single perioperative study that concluded pre-induction mean arterial pressure cannot be used as a surrogate for the normal daytime mean arterial pressure derived from ambulatory measurements.33

Fig 1.

Recommended approach for measuring arterial blood pressure in the clinic. The accurate measurement of blood pressure is essential for the diagnosis and management of hypertension. Fully automated oscillometric devices capable of taking multiple readings without an observer being present provide a more accurate measurement of blood pressure (BP) than auscultation. Environmental factors affect the BP readings substantially, necessitating ambulatory BP recordings in the majority of individuals for an accurate reflection of their cardiovascular risk in relation to blood pressure. Adapted from UK (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136/documents/evidence-review) and international evidence-based guidelines.

Defining blood pressure thresholds for risk: a rapidly changing landscape

A meta-analysis of 61 prospective observational studies (totalling >12.7 million person-years at risk) suggested >20 yr ago that progressively higher arterial blood pressure – from middle age onwards – represents a continuum of increasing risk for vascular and all-cause mortality.34 The strength of this associative relationship suggested that a reduction in blood pressure of just 2 mm Hg may lower mortality from cardiovascular disease by 7%.34 The landmark Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) RCT confirmed this hypothesis, showing that a systolic blood pressure <120 mm Hg reduced major adverse cardiovascular events and lower all-cause mortality, compared with targeting 140 mm Hg over a median follow-up duration of ∼3.9 yr.35 Nearly a third of 9361 SPRINT participants were age >75 yr, had chronic kidney disease, or both, which are major risk factors for perioperative complications.36

In strong support of SPRINT, the Strategy of Blood Pressure Intervention in the Elderly Hypertensive Patients (STEP) multicentre trial in 8511 older Han Chinese hypertensive individuals (mean age, 66 yr) reported that intensive treatment (mean blood pressure, 127/76 mm Hg) facilitated by home monitoring resulted in fewer cardiovascular events, compared with the comparator group (136/79 mm Hg). Unlike SPRINT, STEP found no difference in all-cause mortality, but stroke, acute coronary syndrome, and cardiac failure were all reduced by intensive blood pressure lowering. SPRINT and STEP reveal five findings of particular perioperative relevance. First, the benefit of intensive treatment to achieve lower systolic blood pressure emerged faster in STEP (3 months), compared with SPRINT (∼12 months), despite a rapid reduction in both within 1–2 months of commencing therapy. The temporal disconnect between reduced blood pressure and end-organ injury suggests that blood pressure control is multifactorial, with numerous mechanisms at play. Second, at most, <4% of participants sustained adverse renal events, which were solitary, transient, and low-grade acute kidney injury (although SPRINT reported that acute kidney injury or renal failure occurred more often after intensive treatment, in contrast to STEP). Third, intensive blood pressure lowering in both STEP and SPRINT reported similarly higher (∼3.4%) frequency of hypotension, which was only defined a priori in STEP (systolic blood pressure <110 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure <50 mm Hg, or both). However, the overall rates of serious adverse events did not differ between subjects randomised to intensive vs standard blood pressure treatment in either trial. Fourth, there was no clear decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate >50% or end-stage renal disease for participants with chronic kidney disease. Fifth, at least two drugs were required in the majority of participants randomised to intensive blood pressure lowering, with the most common combination of calcium channel blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs)/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) being taken by 42% of participants in STEP.

Two further RCTs, ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes; 4733 patients with type 2 diabetes)37 and HOPE-3 (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation; 12 705 intermediate risk individuals),38 provide further support for lower blood pressure and reduced cardiovascular morbidity/mortality. Taken together, multiple antihypertensive drugs acting through different mechanisms are required to beneficially lower systolic blood pressure targets that are well below frequently cited perioperative systolic targets. Furthermore, STEP and SPRINT herald a new era of perioperative patients presenting with far lower ‘normal’ blood pressure than we have encountered before. These findings not only echo the lack of clear relationship between blood pressure thresholds and perioperative organ injury, but demand a major reappraisal of perioperative blood pressure management in general. However, to formulate such a rationale, a more sophisticated consideration of blood pressure and hypertension is required beyond just macrovascular targets.

Perioperative clues from SPRINT and STEP

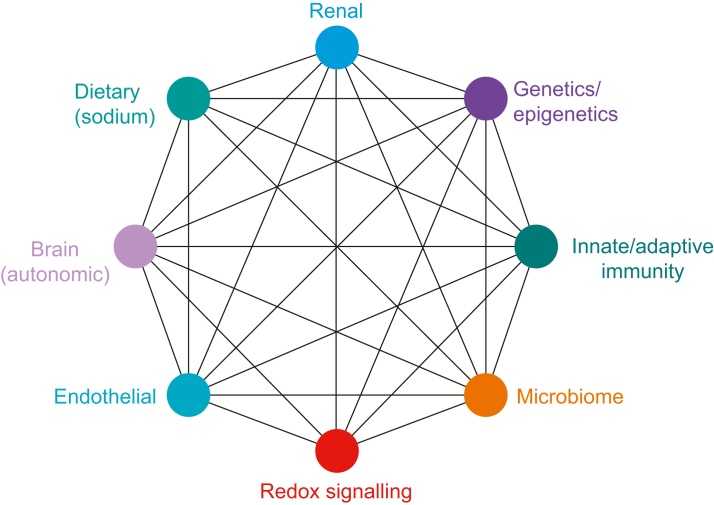

Data from SPRINT and STEP clearly demonstrate that elevated blood pressure as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease should be considered as a continuous variable, rather than a binary categorical variable. In other words, it is misleading to continue to consider hypertension as a dichotomised disease, rather than a spectrum of risk with increasing blood pressure. Moreover, the parallel increase in risk from developing, or progressing, cardiovascular pathology with progressively higher blood pressure can be reversed through the use of multiple anti-hypertensive agents that act through different cellular mechanisms. These observations are consistent with the mosaic theory of hypertension (Fig. 2), first proposed more than 80 yr ago by Page.40 The mosaic theory incorporates multiple pathological mechanisms that are likely to promote the development of perioperative organ injury in individuals with higher blood pressure (although not necessarily ‘hypertensive’), even in the absence of end-organ damage associated with chronic hypertension.

Fig 2.

Mosaic theory of essential hypertension. From the mosaic theory, hypertension is a multifactorial disorder that develops because of multiple interactions between genetic, environmental, anatomical, adaptive neural, endocrine, humoral, and haemodynamic factors. Genome-wide association studies that identified 901 loci linked to hypertension account for only ∼5.7% of variation in blood pressure.39

A synergistic final pathway explains why variable blood pressure thresholds are associated with perioperative organ injury

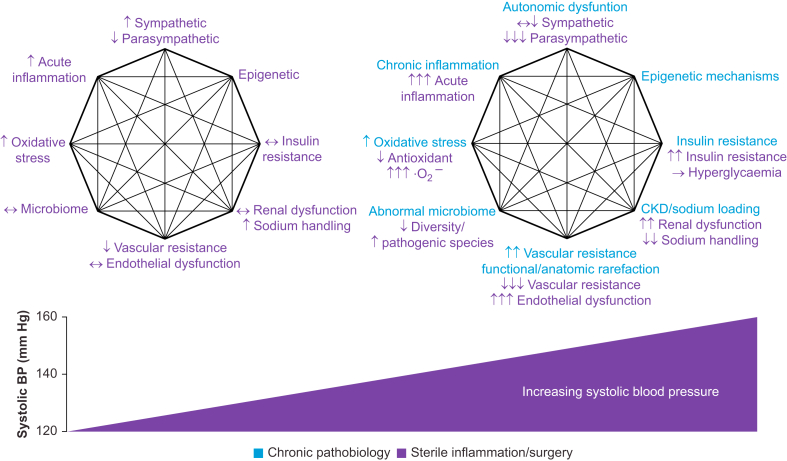

The mosaic theory provides a framework to understand hypertension as a syndrome characterised by the dysregulation of multiple interacting mechanisms, which is of direct relevance to the development of organ injury during the perioperative period. Although apparently common, relatively lower blood pressure alone appears to be insufficient to cause organ injury in the perioperative period, implying that the lack of a reproducible threshold value may be attributable to other pathological mechanisms. Indeed, two fundamental interlinked culprit mechanisms underpinning the development of hypertension from the outset (i.e. even before end-organ damage) promote tissue hypoxia and inflammation, which are established synergistic drivers of acute cellular injury and organ dysfunction (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Interaction between the perioperative period and mosaic theory mechanisms causing higher blood pressure (BP). The diagram compares the response to surgery of normotensive (on the left) and hypertensive (on the right) patients, based on key mosaic theory-based mechanisms. Individuals with higher BP either fail to counteract or augment injurious pathways that are activated after major surgical tissue trauma.

Culprit mechanism 1: tissue hypoxia through dysregulated microvascular control

Individuals with higher chronic blood pressure are more likely to sustain tissue hypoxia as a result of microvascular dysfunction driven by functional rarefaction, anatomical rarefaction, or both, which is observed in multiple organs.41 Functional rarefaction describes the dysregulation of vasomotor tone in individuals with higher blood pressure, resulting in vasoconstriction or reduced vasodilatation.42 Arterioles in both clinical and experimental hypertension respond to vasoconstrictors such as norepinephrine in an exaggerated manner, resulting in constriction (or even closure) that further impedes flow resulting in tissue hypoxia.43,44 Reduced bioactivity of endothelium-derived nitric oxide also prevents optimal vasodilatory responses.45 Quantification of ocular capillary blood flow by laser Doppler flowmetry demonstrates that retinal capillary rarefaction is evident in early untreated hypertension, a feature that becomes more marked with longer duration of disease.46 Longer-term microvascular injury through progressive structural and anatomical rarefaction elevates systemic capillary pressure, which results in interstitial oedema and extravasation of plasma proteins and leucocytes47; endothelial-derived inflammation initiates, amplifies, or both, further inflammation.48 Several established antihypertensive drugs not only reduce vasomotor tone, but also improve the structure of the microvascular network.49

Pre-existing microvascular dysfunction is amplified by the frequent loss of haemodynamic coherence perioperatively, when a disconnect between macrovascular parameters and the microcirculation develops.50 Therapeutic interventions to normalise systemic blood pressure do not necessarily correct impaired microcirculatory perfusion and hence oxygen delivery remains compromised.50 Under resting conditions, microvascular networks maintain the potential for increasing flow when challenged with increased metabolic needs, a feature absent even in early hypertension. Even brief episodes of hypotension can lead to prolonged periods of disordered microcirculation and tissue perfusion, resulting in metabolically compromised cells.51 Loss of coherent control between macrovascular and microvascular circulations is therefore likely to promote therapeutic measures targeted towards macrovascular variables that potentially cause unintentional harm, such as the inappropriate administration of fluids, vasopressor drugs, or both. This may explain why correcting macrovascular haemodynamic variables to normalise systemic oxygen delivery may be ineffective once systemic inflammation is established.52, 53, 54 Thus, even though macrovascular (systemic arterial pressure) parameters may appear to be adequate in both acute and chronic pathological states, this does not necessarily reflect intra-organ microvascular blood flow. In other words, adequate blood pressure is necessary to ensure adequate blood flow to meet cellular metabolic demands but does not guarantee end-organ microvascular nutrient blood flow.

Culprit mechanism 2: acute inflammation

The pro-inflammatory Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4), the key extracellular receptor for both bacterial lipopolysaccharide and danger-associated molecules generated by trauma, is ubiquitously expressed across all cell types. Thus, both sterile and infectious inflammation share this ancient, conserved receptor. Unfortunately, TLR4 is upregulated by both hypoxia55 and angiotensin II,56,57 a pivotal player in the development of high blood pressure, in multiple cell types, including renal mesangial,58 cardiac,59 microglial,60 smooth muscle,61 and peripheral immune cells.62 Systemic TLR4 blockade and inherited functional mutations in the TLR4 gene reduce blood pressure and limit end-organ damage in a variety of experimental models of hypertension.63 Beyond laboratory models, the combination of tissue hypoxia and upregulation of TLR4 expression in raised blood pressure explains why TLR4 expression on organs at risk of injury determines outcome after renal ischaemia and reperfusion. The immediate graft function in donor kidneys is better in individuals with a loss-of-function TLR4 allele, compared with donor kidneys that have a functional TLR4 gene.64 Thus, despite the same degree of ischaemic injury in donor kidneys, the degree of renal injury is largely determined by the magnitude of concomitant inflammation. These data are reinforced by the observation that preoperative inflammation is associated with excess postoperative morbidity.65

Key mechanisms underlying mosaic theory that promote tissue hypoxia and exaggerated inflammation

The perioperative implications of primed, pathophysiological mechanisms unveiled by tissue injury and sterile inflammation in individuals with higher blood pressure are broad. These malignant actors cause cellular injury either in combination with acute-on-chronic hypoperfusion or independently of breaching blood pressure thresholds associated with perioperative harm. Several key mosaic theory-based mechanisms that result in higher blood pressure provide multiple pathological processes through which perioperative organ injury may occur. Notably, these mechanisms are in play even in the absence of end-organ damage caused by chronic hypertension.

Renin–angiotensin system

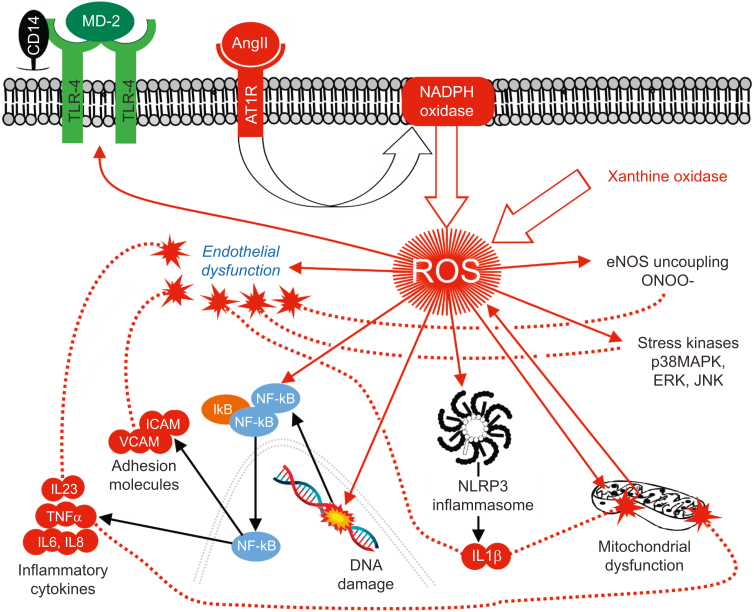

The complexity of the renin–angiotensin system explains why ACEIs/ARBs, which were second-line treatments in SPRINT and STEP, confer clinical benefit beyond just arterial lowering blood pressure. The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) is pivotal for integrating many pathological features of higher blood pressure at the cellular level in both cardiovascular and extravascular organs, including triggering immune dysfunction through to the release of injurious reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Fig. 4). Beyond the injurious angiotensin II/angiotensin 1 receptor (AngII/AT1R) component, this hormonal system also comprises many more enzymes and peptide intermediates including peptide fragments of AngII, which result from cleavage by carboxy- or aminopeptidases. Briefly, multiple enzymes involved in the generation of these angiotensin fragments, including ACE, ACE2 (angiotensin II), neprilysin, and chymase, contribute to the ‘organ-protective’ arm of the renin–angiotensin system,66 which counteracts the injurious actions of AngII via AT1R including the inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity and endothelial dysfunction. Activation of the angiotensin II receptor (AT2R) by AngII triggers vasodilation through the release of nitric oxide from vascular endothelial cells. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 shifts the RAAS towards a vasodilatory, organ-protective axis by enzymatically converting Ang II to angiotensin-(1–7) [Ang-(1–7)], alamandine [derived from Ang-(1–7)], and its receptor, the Mas-related G-coupled receptor.67

Fig 4.

Interplay between renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Angiotensin II, a pivotal mediator of developing higher blood pressure, directly activates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, which directly generates reactive oxygen species (ROS). Additional ROS release induced by damaged mitochondria, plus uncoupled nitric oxide synthase and xanthine oxidase, also contributes to injury in multiple cell types, including endothelial, vascular smooth muscle, neuronal, and renal tubular cells. Upregulation of pro-inflammatory TLR4 receptors, which detect pathogen and danger-associated molecules predispose individuals with higher blood pressure to an exaggerated innate immune response. CD14, cluster of differentiation 14; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinases; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; iκB, inhibitor of κb; IL23, interleukin 23; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinases; MD-2, myeloid differentiation factor 2; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NLRP3, NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3; ONOO–, peroxynitrite; p38 MAPK, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase; TLR4, Toll-like 4 receptor; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor alpha; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1.

The release of central nervous system AngII or AngIII (angiotensin III) activates AT1R within brain autonomic centres, resulting in raised blood pressure via stimulation of sympathetic outflow and vasopressin secretion.68 Remarkably, modulating CNS RAAS alone ameliorates the peripheral, end-organ consequences of increased activation of the sympathetic nervous system.69 Sustained activation of brain AT1R induces neuroinflammation, chronic sympathoexcitation, leading to resistant hypertension of neurogenic origin.70 By contrast, activation of neuronal AT2R within the brain lowers blood pressure.71

Blocking the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: perioperative implications

The direct impact of starting/continuing these drugs in the perioperative period remains controversial, largely because their variable pharmacokinetics cloud the interpretation of studies which have failed to account for an adequate washout period before surgery.72 The pluripotent properties of ACEIs/ARBs extend beyond just lowering blood pressure, including antioxidant,73 G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) recycling,74 and anti-inflammatory actions.75 Nevertheless, failing to administer these drugs soon after cardiac76 and noncardiac77,78 surgery is associated with worse outcome, suggesting that ‘rebound’ inflammatory and oxidative stress in the face of high circulating levels of angiotensin II and upregulated AT1R may plausibly contribute to ongoing organ injury. In patients hospitalised for acute heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, withdrawal of ACEI/ARB during hospitalisation is associated with higher rates of post-discharge mortality and readmission, even after adjustment for severity of heart failure.79 Perioperative trials therefore need to account for organ injury that is plausibly accounted for by sudden AngII excess and/or absence of organ-protective, anti-inflammatory ACEIs/ARBs80 beyond gross macrovascular perturbation, including hypotension.

Oxidative stress: a pivotal feature of developing higher blood pressure

Increased cellular production of ROS through the RAAS is pivotal to the development of high blood pressure.81 The pathological effects of sustained ROS generation, involving crosstalk between nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and mitochondrial ROS82 are widespread and complex, leading to the activation of multiple pro-inflammatory pathways by activating redox-sensitive transcription factors, nuclear factor kappa B and the NLRP3 inflammasome (Fig. 4). The consequent reduction in nitric oxide bioavailability impairs endothelial function,83 promotes adhesion of leucocytes to the endothelium and increased vascular permeability,84 increases central sympathetic neuronal activity/outflow,69 and impairs renal tubular sodium transport.85 Limited data suggest that an impaired capacity to buffer oxidative stress is a feature of human and experimental hypertension, implying that a diminished defence in individuals with raised blood pressure against perioperative ROS is likely.86

Oxidative stress – perioperative implications

Proteomic characterisation of skin after major surgery suggests that oxidative stress may be ameliorated by ensuring adequate systemic oxygen delivery,87 supporting a role for ensuring adequate cardiac output via monitoring.88 Although 97 perioperative trials have explored N-acetylcysteine (36 trials) and other antioxidant therapies, the poor quality of studies conducted thus far (largely in cardiac surgery) precludes any role for this approach.89 The case for limiting ROS by minimising exposure to hyperoxia90,91 looks increasingly tenuous given that targeting lower arterial oxygen did not alter mortality in critical illness.92

Autonomic dysfunction: an early pathogenic feature of raised blood pressure

Both adrenergic and vagal dysfunction promote, amplify, or both, higher blood pressure.93 Abnormal increases in circulating plasma levels of norepinephrine and epinephrine have repeatedly been demonstrated in normotensive individuals with a family history of hypertension.94, 95, 96 Moreover, pressor responses to standardised stressors and microneurographic studies quantifying postganglionic sympathetic nerve traffic predict the subsequent development of hypertension in at-risk normotensive individuals.97,98 In parallel, normotensive offspring of hypertensive parents have lower vagal modulation of heart rate variability.99 Thus, aberrant autonomic regulation is common and precedes the development of higher blood pressure and altered adrenoceptor sensitivity, suggesting a causative role of autonomic dysfunction in the development of hypertension. Reduced baroreflex sensitivity74,100 and cardiac vagal function before101, 102, 103 and after surgery104 are common in higher-risk patients (of whom ∼55% are treated for hypertension)102 and are linked mechanistically to worse outcomes.100

Autonomic dysfunction – perioperative implications

The relative reliance on higher sympathetic drive in higher risk, older individuals before surgery may explain the common occurrence of post-induction hypotension, which is autonomically akin to the hypovolaemic young patient. Similarly, recurrent hypotension after surgery is more likely to occur in individuals who experience intraoperative hypotension, suggesting that the perioperative period reveals an autonomic endotype that predisposes to hypotension.105 Anaesthetic agents further impair baroreflex sensitivity in these patients, removing a key defence mechanism that helps ensure integrative blood pressure control.106 Loss of the arterial baroreflex is manifest by both low and high extreme swings in blood pressure. The common use of pressors under these circumstances may correct hypotension, but at the expense of multi-organ cellular injury. Acute hypertensive episodes for ∼1 h after phenylephrine infusion in anaesthetised pigs lead to elevated plasma troponin, possibly secondary to calpain-mediated proteolysis of troponin triggered by cardiomyocyte stretch in the absence of ischaemia.107 β-Adrenergic catecholamines, acting through β-arrestin-mediated recycling pathways, trigger DNA damage and suppress p53 levels leading to the accumulation of further DNA damage and inflammation.108 Persistent sympathoexcitation reduces recycling of critical GPCRs required for efficient inotropy, and calcium overload and consequent bioenergetic compromise. Beyond direct cellular injury, phenylephrine24 and norepinephrine23 promote infection and bacterial outgrowth by inducing immunosuppression. Conversely, reduced vagal activity augments both the acute109 and chronic110 inflammatory response; vagal loss may be an unavoidable or unintended consequence of various perioperative interventions including anaesthetic agents,111 withdrawal of ACEIs,112 and upper limb blocks.113 Thus, the clinical management of hypotension may inadvertently generate organ dysfunction through direct and indirect pathological mechanisms, independent of hypoperfusion.

Immune dysregulation: a pivotal mechanism underpinning raised blood pressure that also shapes the acute inflammatory response

In highly reproducible translational rodent laboratory models of hypertension, specific leucocyte subsets have either promoted or reversed elevated blood pressure.114 Monocytes and macrophages play a temporal and site-specific role in models of salt-sensitive hypertension, through the early promotion of high blood pressure by generating pro-inflammatory cytokines in the skin.115 However, pivotal trials examining the role of inflammation in cardiovascular disease have reduced cardiovascular events without any clear effect on lowering blood pressure.116,117 These data suggest that although early, critical inflammatory processes are pivotal for the development of higher blood pressure, attempts to reverse established chronic inflammation are ineffective. However, how the chronic inflammatory phenotype of hypertensive individuals shapes superimposed acute inflammatory insults is largely unknown, which is surprising given that clinical hypertension is clearly associated with distinct innate and adaptive immune activation.118 Hypertensive individuals exhibit marked increases in activated CD8+ T cells119 and ‘primed’ monocytes, which produce more pro-inflammatory cytokines when stimulated ex vivo with angiotensin II or lipopolysaccharide, compared with monocytes from healthy controls.120 Angiotensin-II upregulates TLR4 expression in several tissues62; TLR4 is a key receptor for both sterile (danger-associated molecular patterns [DAMPs]) and microbial (pathogen-associated molecular patterns [PAMPs]) sources of inflammation that drive organ dysfunction after surgery. The increased CD14++CD16+ monocyte population121 seen in individuals with higher blood pressure and surgical patients with poor cardiopulmonary reserve122 independently predicts cardiovascular events.123

Immune dysregulation – perioperative implications

Even before the macrovascular pathological features of essential hypertension occur, higher blood pressure is clearly linked to disruption of pathways involved in dampening and resolving inflammation. Hypertensive, genetically distinct rats express different patterns of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels, response to antibiotics, and survival after experimental polymicrobial sepsis.124 Primed, pro-inflammatory monocytes typically promote an exaggerated systemic inflammatory response, suggesting that individuals with higher blood pressure may generate more organ injury as a result of prolonged – or non-resolving – inflammation. The combination of cellular dysoxia (precipitated by hypotensive hypoperfusion) plus excessive, sustained inflammation125 has been demonstrated repeatedly to cause more severe organ injury relevant to the perioperative period.126, 127, 128 Given that biomarkers for higher levels of preoperative inflammation are associated with multi-organ injury/dysfunction,65 an exaggerated inflammatory response accompanying even brief episodes of tissue hypoxia may provide the ‘missing link’ between highly variable blood pressure thresholds and poorer outcomes. Several antihypertensive drugs, including third-generation β-blockers and calcium channel antagonists, also exert pleiotropic anti-inflammatory effects.129

The microbiome shapes blood pressure

The transformation of food by the gut microbiome generates small metabolites that directly, or indirectly via immune dysregulation, promote higher blood pressure.130 Laboratory studies provide proof of concept data that transplanting the dysbiotic gut contents of spontaneously hypertensive rats increases systolic blood pressure in Wistar–Kyoto (otherwise) normotensive rats.131 High salt treatment in both mice and humans reduced Lactobacillus species and increased blood pressure.132 Similarly, increased consumption of dietary fibre leads to the production of short-chain fatty acids, expansion of anti-inflammatory immune cells and slower progression of hypertension.133 In humans, Gram-negative microbiota and reduced alpha diversity are more common in individuals with higher blood pressure.134 The loss of gut microbiota-derived short chain fatty acids after antibiotic administration impairs host immunity and reparative mechanisms after experimental myocardial infarction.135 Taken together, these proofs of concept support the idea that the microbiome phenotype associated with higher blood pressure contributes to the severity of organ injury.

Microbiome – perioperative implications

Alterations in the gut microbiome described in several models of hypertension are likely to increase susceptibility to postoperative infections and organ injury through several mechanisms, including expansion of pathogenic intestinal bacteria and priming an exaggerated pro-inflammatory immune response.136

Salt intake and storage

High dietary salt intake137 is a key driver in elevating blood pressure. Population data from the UK Biobank suggest that lifestyle factors account for at least up to 5 mm Hg higher blood pressure.138 A large RCT in rural China recently confirmed that reduced dietary sodium and high potassium intake results in lower blood pressure and an associated increase in major cardiovascular events and mortality.139 Although renal handling of salt is critical, other organs including skin and muscle play a role in storing sodium. Experimental models of chronic intracellular sodium elevation in the heart lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and cardiac injury.140 Salt activates myeloid and T cells to adopt a pro-inflammatory state, with dysregulation of the gut microbiome, skin resident monocyte/macrophages, regulatory T cells, natural killer T cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells contributing to blood pressure.141

Salt – perioperative implications

Substantial gains in body weight through fluid retention after surgery are consistently associated with poorer outcomes, which appear likely to be attributable to several pathological mechanisms. The salt load typically associated with major surgery (assuming 10 ml kg h−1 intravenous fluid is administered for 24 h) equates to ≥40 g additional sodium chloride in a 70 kg person.142 Cells in individuals with higher blood pressure are unlikely to be equipped to handle this extraordinary perioperative salt challenge, given the impairment of Na/K-ATPase signalling that has been described in salt-sensitive models of hypertension.143 There are deleterious consequences for two reasons relevant to the perioperative period. First, extracellular water retention was observed in healthy males randomised to just 6 g extra daily salt intake, which was accompanied by mineralocorticoid-coupled increases in free water reabsorption counterbalanced by glucocorticoid release.144 This water-conserving mechanism of dietary salt excretion relies on urea recycling by the kidneys and on urea production by liver and skeletal muscle. Hepatic and extrahepatic urea osmolyte production for renal water conservation requires energy-intense metabolism in liver and skeletal muscle. This results in hepatic ketogenesis and glucocorticoid-driven muscle catabolism, recapitulating several cardinal features of the postoperative patient who fails to thrive. Second, acute high-salt exposure causes morphological signs of renal injury within 3 days in young Dahl salt-sensitive rats, mediated by increased leucocyte adhesion (without any change in blood pressure).145

Hyperinsulinaemia/insulin resistance

Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia are well-established correlates of increased blood pressure.146 Compression of the kidneys by visceral/peri-renal fat, activation of RAAS and sympathetic neurones by insulin and serum and glucocorticoid kinase-1 (which regulates vascular and renal sodium Na+ channel activity) provide mechanistic links between excess visceral adiposity with vascular stiffening, increased blood pressure, or both.147

Hyperglycaemia – perioperative implications

Predisposition to insulin resistance increases the risk of perioperative hyperglycaemia; a progressive increase in unadjusted fasting glucose concentration is associated with myocardial injury and a higher risk of death within 30 days of surgery.148 Notably, these findings were particularly prominent in non-diabetic individuals, which is consistent with laboratory findings that acute hyperglycaemia in healthy cells directly causes excess production of ROS by fragmentation of mitochondrial tubules.149 Because the higher blood pressure phenotype is characterised by chronic oxidative stress, acute-on-chronic hyperglycaemic injury drives pro-oxidant advanced glycation end products and alternative metabolic pathways that further suppress antioxidant enzymes and pathways.150 Rapid, deleterious changes in mitochondrial quality control can occur in acute hyperglycaemia and therefore may plausibly contribute to perioperative cardiorenal injury.151

In summary, given the lack of clarity on specific thresholds and the results of recent interventional trials, hypotension – however defined – appears unlikely to be a sole mechanism for sustaining organ injury. The presence of subclinical pathological mechanisms in at-risk patients may transform an apparently innocuous lower intraoperative blood pressure into a life-changing injury, even in the absence of chronic hypertension-related end-organ damage. Interventional trials in this area suggest there are no easy answers, with the distinct possibility that the off-target effects of various pharmacological interventions may be unavoidable. Given the inherent biases embedded in open-label clinical studies, there is an urgent need for smart, mechanistic, blinded RCTs (which are undoubtedly challenging to design). At a holistic level, a fundamental role for perioperative medicine appears now to encompass helping identify – and treat – the rapidly expanding population of patients identified by SPRINT and STEP in whom lower blood pressure will be beneficial. Blood pressure can no longer be merely treated as a dichotomised number to treat. Perioperative medicine is ideally placed to help unravel several of the enigmas of blood pressure biology in acute illness and injury.

Authors' contributions

Study concept: GLA

Writing of the first draft of the manuscript: GLA, TEFA

Declarations of interest

GLA: editor and editorial board of the British Journal of Anaesthesia; consultancy work for GlaxoSmithKline, unrelated to this work. TEFA: editorial board of the British Journal of Anaesthesia; consultancy work for MSD, unrelated to this work.

Funding

British Oxygen Company research chair in anaesthesia, administered by National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia; NIHR Advanced Fellowship (NIHR 300097 to GLA). NIHR Clinical Lectureship (to TEFA).

Handling editor: Jonathan Hardman

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2022.01.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Wesselink E.M., Kappen T.H., Torn H.M., Slooter A.J.C., van Klei W.A. Intraoperative hypotension and the risk of postoperative adverse outcomes: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:706–721. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh M., Devereaux P.J., Garg A.X., et al. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:507–515. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a10e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sessler D.I., Bloomstone J.A., Aronson S., et al. Perioperative quality initiative consensus statement on intraoperative blood pressure, risk and outcomes for elective surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:563–574. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McEvoy M.D., Gupta R., Koepke E.J., et al. Perioperative quality initiative consensus statement on postoperative blood pressure, risk and outcomes for elective surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:575–586. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bijker J.B., van Klei W.A., Kappen T.H., van Wolfswinkel L., Moons K.G., Kalkman C.J. Incidence of intraoperative hypotension as a function of the chosen definition: literature definitions applied to a retrospective cohort using automated data collection. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:213–220. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000270724.40897.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vernooij L.M., van Klei W.A., Machina M., Pasma W., Beattie W.S., Peelen L.M. Different methods of modelling intraoperative hypotension and their association with postoperative complications in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:1080–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ke J.X.C., George R.B., Beattie W.S. Making sense of the impact of intraoperative hypotension: from populations to the individual patient. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:689–691. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kappen T., Beattie W.S. Perioperative hypotension 2021: a contrarian view. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127:167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ackland G.L., Brudney C.S., Cecconi M., et al. Perioperative quality initiative consensus statement on the physiology of arterial blood pressure control in perioperative medicine. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Idowu T.O., Etzrodt V., Pape T., et al. Flow-dependent regulation of endothelial Tie2 by GATA3 in vivo. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2021;9:38. doi: 10.1186/s40635-021-00402-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng L. Heterogeneous impact of hypotension on organ perfusion and outcomes: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127:845–861. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCormick P.J., Levin M.A., Lin H.M., Sessler D.I., Reich D.L. Effectiveness of an electronic alert for hypotension and low bispectral index on 90-day postoperative mortality: a prospective, randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:1113–1120. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sessler D.I., Turan A., Stapelfeldt W.H., et al. Triple-low alerts do not reduce mortality: a real-time randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2019;130:72–82. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wijnberge M., Geerts B.F., Hol L., et al. Effect of a machine learning-derived early warning system for intraoperative hypotension vs standard care on depth and duration of intraoperative hypotension during elective noncardiac surgery: the HYPE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323:1052–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Futier E., Lefrant J.Y., Guinot P.G., et al. Effect of individualized vs standard blood pressure management strategies on postoperative organ dysfunction among high-risk patients undergoing major surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1346–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.14172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langer T., Santini A., Zadek F., et al. Intraoperative hypotension is not associated with postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia for surgery: results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Clin Anesth. 2019;52:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2018.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu X., Jiang Z., Ying J., Han Y., Chen Z. Optimal blood pressure decreases acute kidney injury after gastrointestinal surgery in elderly hypertensive patients: a randomized study: optimal blood pressure reduces acute kidney injury. J Clin Anesth. 2017;43:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamontagne F., Richards-Belle A., Thomas K., et al. Effect of reduced exposure to vasopressors on 90-day mortality in older critically ill patients with vasodilatory hypotension: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323:938–949. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wanner P.M., Wulff D.U., Djurdjevic M., Korte W., Schnider T.W., Filipovic M. Targeting higher intraoperative blood pressures does not reduce adverse cardiovascular events following noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:1753–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panjasawatwong K., Sessler D.I., Stapelfeldt W.H., et al. A randomized trial of a supplemental alarm for critically low systolic blood pressure. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:1500–1507. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaukonen K.M., Bailey M., Pilcher D., Cooper D.J., Bellomo R. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1629–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyte M., Freestone P.P., Neal C.P., et al. Stimulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis growth and biofilm formation by catecholamine inotropes. Lancet. 2003;361:130–135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stolk R.F., Kox M., Pickkers P. Noradrenaline drives immunosuppression in sepsis: clinical consequences. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1246–1248. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06025-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stolk R.F., Naumann F., van der Pasch E., et al. Phenylephrine impairs host defence mechanisms to infection: a combined laboratory study in mice and translational human study. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:652–664. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brouwers S., Sudano I., Kokubo Y., Sulaica E.M. Arterial hypertension. Lancet. 2021;398:249–261. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00221-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piper M.A., Evans C.V., Burda B.U., Margolis K.L., O'Connor E., Whitlock E.P. Diagnostic and predictive accuracy of blood pressure screening methods with consideration of rescreening intervals: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:192–204. doi: 10.7326/M14-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Institute for Clinical Excellence UK . NICE guideline [NG136] National Institute for Clinical Excellence; UK: 2019. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management | guidance and guidelines.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG127 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sega R., Trocino G., Lanzarotti A., et al. Alterations of cardiac structure in patients with isolated office, ambulatory, or home hypertension: data from the general population (Pressione Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni [PAMELA] Study) Circulation. 2001;104:1385–1392. doi: 10.1161/hc3701.096100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stergiou G.S., Asayama K., Thijs L., et al. Prognosis of white-coat and masked hypertension: International Database of HOme blood pressure in relation to cardiovascular outcome. Hypertension. 2014;63:675–682. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoshide S., Yano Y., Mizuno H., Kanegae H., Kario K. Day-by-day variability of home blood pressure and incident cardiovascular disease in clinical practice: the J-HOP study (Japan Morning Surge-Home Blood Pressure) Hypertension. 2018;71:177–184. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kario K., Hoshide S., Mizuno H., et al. Nighttime blood pressure phenotype and cardiovascular prognosis: practitioner-based nationwide JAMP Study. Circulation. 2020;142:1810–1820. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.049730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de la Sierra A., Redon J., Banegas J.R., et al. Prevalence and factors associated with circadian blood pressure patterns in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2009;53:466–472. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.124008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saugel B., Reese P.C., Sessler D.I., et al. Automated ambulatory blood pressure measurements and intraoperative hypotension in patients having noncardiac surgery with general anesthesia: a prospective observational study. Anesthesiology. 2019;131:74–83. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewington S., Clarke R., Qizilbash N., Peto R., Collins R., Prospective Studies Collaboration Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Group S.R., Lewis C.E., Fine L.J., et al. Final report of a trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1921–1930. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ackland G.L., Moran N., Cone S., Grocott M.P.W., Mythen M.G. Chronic kidney disease and postoperative morbidity after elective orthopedic surgery. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:1375–1381. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181ee8456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Group A.S., Cushman W.C., Evans G.W., et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lonn E.M., Bosch J., Lopez-Jaramillo P., et al. Blood-pressure lowering in intermediate-risk persons without cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2009–2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evangelou E., Warren H.R., Mosen-Ansorena D., et al. Genetic analysis of over 1 million people identifies 535 new loci associated with blood pressure traits. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1412–1425. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0205-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Page I.H. The mosaic theory of arterial hypertension—its interpretation. Perspect Biol Med. 1967;10:325–333. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1967.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feihl F., Liaudet L., Waeber B., Levy B.I. Hypertension: a disease of the microcirculation? Hypertension. 2006;48:1012–1017. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000249510.20326.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levy B.I., Ambrosio G., Pries A.R., Struijker-Boudier H.A. Microcirculation in hypertension: a new target for treatment? Circulation. 2001;104:735–740. doi: 10.1161/hc3101.091158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bohlen H.G. Arteriolar closure mediated by hyperresponsiveness to norepinephrine in hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1979;236:H157–H164. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.1.H157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vicaut E., Hou X. Local renin-angiotensin system in the microcirculation of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1994;24:70–76. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.24.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrison D.G. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of endothelial cell dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2153–2157. doi: 10.1172/JCI119751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bosch A.J., Harazny J.M., Kistner I., Friedrich S., Wojtkiewicz J., Schmieder R.E. Retinal capillary rarefaction in patients with untreated mild-moderate hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17:300. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0732-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takase S., Lerond L., Bergan J.J., Schmid-Schonbein G.W. Enhancement of reperfusion injury by elevation of microvascular pressures. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1387–H1394. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01003.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao L., Harrison D.G. Inflammation in hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antonios T.F. Microvascular rarefaction in hypertension—reversal or over-correction by treatment? Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:484–485. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ince C. Hemodynamic coherence and the rationale for monitoring the microcirculation. Crit Care. 2015;19:S8. doi: 10.1186/cc14726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamilton-Davies C., Mythen M.G., Salmon J.B., Jacobson D., Shukla A., Webb A.R. Comparison of commonly used clinical indicators of hypovolaemia with gastrointestinal tonometry. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:276–281. doi: 10.1007/s001340050328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Investigators P., Rowan K.M., Angus D.C., et al. Early, goal-directed therapy for septic shock — a patient-level meta-analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2223–2234. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ackland G.L., Iqbal S., Paredes L.G., et al. Individualised oxygen delivery targeted haemodynamic therapy in high-risk surgical patients: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled, mechanistic trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:33–41. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70205-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayes M.A., Timmins A.C., Yau E.H., Palazzo M., Hinds C.J., Watson D. Elevation of systemic oxygen delivery in the treatment of critically ill patients. New Engl J Med. 1994;330:1717–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406163302404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eltzschig H.K., Carmeliet P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:656–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bomfim G.F., Dos Santos R.A., Oliveira M.A., et al. Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to blood pressure regulation and vascular contraction in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122:535–543. doi: 10.1042/CS20110523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sollinger D., Eissler R., Lorenz S., et al. Damage-associated molecular pattern activated Toll-like receptor 4 signalling modulates blood pressure in L-NAME-induced hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;101:464–472. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wolf G., Bohlender J., Bondeva T., Roger T., Thaiss F., Wenzel U.O. Angiotensin II upregulates toll-like receptor 4 on mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1585–1593. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eissler R., Schmaderer C., Rusai K., et al. Hypertension augments cardiac Toll-like receptor 4 expression and activity. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:551–558. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Biancardi V.C., Stranahan A.M., Krause E.G., de Kloet A.D., Stern J.E. Cross talk between AT1 receptors and Toll-like receptor 4 in microglia contributes to angiotensin II-derived ROS production in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;310:H404–H415. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00247.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruiz-Ortega M., Lorenzo O., Ruperez M., Konig S., Wittig B., Egido J. Angiotensin II activates nuclear transcription factor kappaB through AT(1) and AT(2) in vascular smooth muscle cells: molecular mechanisms. Circ Res. 2000;86:1266–1272. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.12.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Biancardi V.C., Bomfim G.F., Reis W.L., Al-Gassimi S., Nunes K.P. The interplay between angiotensin II, TLR4 and hypertension. Pharmacol Res. 2017;120:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nunes K.P., de Oliveira A.A., Lima V.V., Webb R.C. Toll-like receptor 4 and blood pressure: lessons from animal studies. Front Physiol. 2019;10:655. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kruger B., Krick S., Dhillon N., et al. Donor Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to ischemia and reperfusion injury following human kidney transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3390–3395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810169106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ackland G.L., Abbott T.E.F., Cain D., et al. Preoperative systemic inflammation and perioperative myocardial injury: prospective observational multicentre cohort study of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meng W., Zhao W., Zhao T., et al. Autocrine and paracrine function of Angiotensin 1–7 in tissue repair during hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:775–782. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpt270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Villela D.C., Passos-Silva D.G., Santos R.A. Alamandine: a new member of the angiotensin family. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23:130–134. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000441052.44406.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miller A.J., Arnold A.C. The renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular autonomic control: recent developments and clinical implications. Clin Auton Res. 2019;29:231–243. doi: 10.1007/s10286-018-0572-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gao L., Wang W., Li Y.L., et al. Superoxide mediates sympathoexcitation in heart failure: roles of angiotensin II and NAD(P)H oxidase. Circ Res. 2004;95:937–944. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146676.04359.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Head G.A. Role of AT1 receptors in the central control of sympathetic vasomotor function. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1996;23:S93–S98. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb02820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gao L., Zucker I.H. AT2 receptor signaling and sympathetic regulation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roshanov P.S., Rochwerg B., Patel A., et al. Withholding versus continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers before noncardiac surgery: an analysis of the vascular events in noncardiac surgery patients cohort evaluation prospective cohort. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:16–27. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Honjo T., Yamaoka-Tojo M., Inoue N. Pleiotropic effects of ARB in vascular metabolism—focusing on atherosclerosis-based cardiovascular disease. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2011;9:145–152. doi: 10.2174/157016111794519273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ackland G.L., Whittle J., Toner A., et al. Molecular mechanisms linking autonomic dysfunction and impaired cardiac contractility in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:e614–e624. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dandona P., Dhindsa S., Ghanim H., Chaudhuri A. Angiotensin II and inflammation: the effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockade. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:20–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Antoniak D.T., Walters R.W., Alla V.M. Impact of renin-angiotensin system blockers on mortality in veterans undergoing cardiac surgery. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e019731. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.019731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee S.M., Takemoto S., Wallace A.W. Association between withholding angiotensin receptor blockers in the early postoperative period and 30-day mortality: a cohort study of the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:288–306. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mudumbai S.C., Takemoto S., Cason B.A., Au S., Upadhyay A., Wallace A.W. Thirty-day mortality risk associated with the postoperative nonresumption of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a retrospective study of the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:289–296. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gilstrap L.G., Fonarow G.C., Desai A.S., et al. Initiation, continuation, or withdrawal of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers and outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004675. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pinter M., Jain R.K. Targeting the renin-angiotensin system to improve cancer treatment: implications for immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan5616. eaan5616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Touyz R.M. Molecular and cellular mechanisms in vascular injury in hypertension: role of angiotensin II. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2005;14:125–131. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200503000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dikalov S.I., Ungvari Z. Role of mitochondrial oxidative stress in hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H1417–H1427. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00089.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schiffrin E.L. Oxidative stress, nitric oxide synthase, and superoxide dismutase: a matter of imbalance underlies endothelial dysfunction in the human coronary circulation. Hypertension. 2008;51:31–32. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Scioli M.G., Storti G., D'Amico F., et al. Oxidative stress and new pathogenetic mechanisms in endothelial dysfunction: potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1995. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gonzalez-Vicente A., Garvin J.L. Effects of reactive oxygen species on tubular transport along the nephron. Antioxidants (Basel) 2017;6:23. doi: 10.3390/antiox6020023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rodrigo R., Gonzalez J., Paoletto F. The role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:431–440. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Heywood W.E., Bliss E., Bahelil F., et al. Proteomic signatures for perioperative oxygen delivery in skin after major elective surgery: mechanistic sub-study of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127:511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pearse R.M., Harrison D.A., MacDonald N., et al. Effect of a perioperative, cardiac output-guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm on outcomes following major gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized clinical trial and systematic review. JAMA. 2014;311:2181–2190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pedersen S.S., Fabritius M.L., Kongebro E.K., Meyhoff C.S. Antioxidant treatment to reduce mortality and serious adverse events in adult surgical patients: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2020;65:438–450. doi: 10.1111/aas.13752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oldman A.H., Martin D.S., Feelisch M., Grocott M.P.W., Cumpstey A.F. Effects of perioperative oxygen concentration on oxidative stress in adult surgical patients: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:622–632. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schjorring O.L., Jensen A.K.G., Nielsen C.G., et al. Arterial oxygen tensions in mechanically ventilated ICU patients and mortality: a retrospective, multicentre, observational cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schjorring O.L., Klitgaard T.L., Perner A., et al. Lower or higher oxygenation targets for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1301–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mancia G., Grassi G. The autonomic nervous system and hypertension. Circ Res. 2014;114:1804–1814. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McCrory W.W., Klein A.A., Rosenthal R.A. Blood pressure, heart rate, and plasma catecholamines in normal and hypertensive children and their siblings at rest and after standing. Hypertension. 1982;4:507–513. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bianchetti M.G., Weidmann P., Beretta-Piccoli C., et al. Disturbed noradrenergic blood pressure control in normotensive members of hypertensive families. Br Heart J. 1984;51:306–311. doi: 10.1136/hrt.51.3.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ferrier C., Cox H., Esler M. Elevated total body noradrenaline spillover in normotensive members of hypertensive families. Clin Sci (Lond) 1993;84:225–230. doi: 10.1042/cs0840225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Smith P.A., Graham L.N., Mackintosh A.F., Stoker J.B., Mary D.A. Relationship between central sympathetic activity and stages of human hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Grassi G., Seravalle G., Trevano F.Q., et al. Neurogenic abnormalities in masked hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;50:537–542. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.092528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maver J., Strucl M., Accetto R. Autonomic nervous system activity in normotensive subjects with a family history of hypertension. Clin Auton Res. 2004;14:369–375. doi: 10.1007/s10286-004-0185-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Toner A., Jenkins N., Ackland G.L., POM-O Study Investigators Baroreflex impairment and morbidity after major surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:324–331. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ackland G.L., Abbott T.E.F., Minto G., et al. Heart rate recovery and morbidity after noncardiac surgery: planned secondary analysis of two prospective, multi-centre, blinded observational studies. PLos One. 2019;14:e0221277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Abbott T.E.F., Pearse R.M., Cuthbertson B.H., Wijeysundera D.N., Ackland G.L. METS study investigators. Cardiac vagal dysfunction and myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery: a planned secondary analysis of the measurement of exercise tolerance before surgery study. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.10.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]