Abstract

The rpoS gene of Serratia entomophila BC4B was cloned and used to create rpoS-mutant strain BC4BRS. Larvae of the New Zealand grass grub Costelytra zealandica infected with BC4BRS became amber colored but continued to feed, albeit to a lesser extent than infected larvae. Subsequently, we found that expression of the antifeeding gene anfA1 in trans was substantially reduced in BC4BRS relative to that in the parental strain BC4B. Our data show that a functional rpoS gene is vital for full expression of anfA1 and for development of the antifeeding component of amber disease.

The soil-borne bacterium Serratia entomophila causes amber disease in a major New Zealand pasture pest, the grass grub Costelytra zealandica (White) [Coleoptera: Scarabideae]. Understanding the molecular mechanism of the disease process is an important objective of our research into the biological control of grass grub infection in New Zealand. The disease process, as described by Jackson et al. (6), is multifactorial. As S. entomophila cells adhere to the grass grub crop and propagate around the cardiac valve, larvae cease feeding, clear their gut, and become amber-colored. Eventually the bacteria cross the crop wall and infect the hemolymph, causing general septicemia and death. Recent research has shown that factors responsible for the gut clearance and amber coloration of larvae are encoded by a 105-kb cryptic plasmid named pADAP (5). Additionally, a locus designated amb1 has been implicated in pili-mediated adherence (24) and evidence suggests that a second locus named amb2 encodes an antifeeding toxin (17).

RpoS (ςS) is a class 2 sigma factor that regulates many of the changes necessary for bacterial survival under stress conditions by altering the promoter specificity of RNA polymerase (E) (12). The ability of RpoS to influence disease processes caused by Salmonella (2, 10) and Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 (21) led us to investigate whether RpoS has a role in the regulation of one or more components of the S. entomophila amber disease system.

Identification and characterization of the rpoS gene of S. entomophila.

The rpoS gene of S. entomophila BC4B was cloned by digesting genomic DNA of this strain with restriction endonucleases SalI and EcoRI and ligating all fragments to similarly digested vector pBR322. rpoS-containing clones were isolated by electroporating ligated DNA into Escherichia coli rpoS mutant ZK918 and selecting for restoration of RpoS-regulated low pH survival as described by Zambrano et al. (25). A clone containing a 4.2-kb SalI-EcoRI BC4B genomic DNA fragment containing rpoS was named pSERS1 (Table 1; Fig. 1). ZK918 (Table 1) contains a λ lysogen in which lacZ expression is under the control of the RpoS-dependent E. coli bolA promoter. bolA is responsible for cell morphology changes during entry to stationary phase by E. coli cells (11). Complementation of ZK918 by pSERS1 led to the expression of lacZ and restoration of hydroperoxidase HPII activity due to the rpoS-dependent expression of katE (15), further verifying that pSERS1 contains an rpoS analogue.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used during this investigation

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli ZK918 | ZK126 rpoS(IS insert) λ(bolA::lacZ) lysogena | R. Kolter |

| S. entomophila | ||

| BC4B | EMS-induced phageR derivative of A1MO2; Path+ | 19 |

| BC4BRS | Marker-interrupted rpoS-minus mutant of BC4B | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pADAP | Cryptic plasmid found in pathogenic strains of S. entomophila and S. proteamaculans encoding amber disease determinants | 4 |

| pALC | pLacZ3 containing a chloramphenicol cassette and an anfA1::lacZ fusion | This study |

| pLacZ3 | lacZ translational-fusion vector | 7 |

| pLC | pLacZ3 containing a chloramphenicol cassette | This study |

| pSERS1 | pBR322 with a 4.2-kb EcoRI-SalI genomic DNA fragment with the rpoS gene of BC4B | This study |

| pSERS2 | pACYC184 with a 4.0-kb SalI-AvaI genomic DNA fragment with the rpoS gene of BC4B | This study |

| pSERS3 | Deletion of a 0.6-kb BamHI fragment of pSERS1 and insertion of a BamHI fragment from pNK2859 (10) encoding kanamycin resistance | This study |

| pSERS4 | EcoRI-SalI fragment from pSERS3 cloned into pLAFR3 | This study |

IS, insertion sequence.

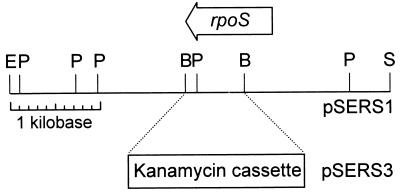

FIG. 1.

Construction of strain BC4BRS, a kanamycin-marked rpoS mutant of S. entomophila strain BC4B. Restriction enzyme cleavage sites are as follows: B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; P, PstI; S, SalI. A 0.6-kb BamHI fragment containing part of the S. entomophila rpoS gene was deleted from pSERS1 and replaced with a 1.4-kb BamHI fragment cloned from pNK2859 that encodes kanamycin resistance. The 4.9-kb SalI-EcoRI insert fragment of pSERS3 was cloned into pLAFR3 and used to replace the wild-type rpoS gene in S. entomophila BC4B by allelic exchange. The resulting rpoS mutant strain was named BC4BRS.

To determine the DNA sequence of the S. entomophila rpoS gene, BamHI and BamHI-PstI fragments of pSERS1 were subcloned into vector pBluescript KS(+) and sequenced by using the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (20). Sequencing of double-stranded DNA was performed with a T7 sequencing Kit (Pharmacia) using T3, T7, SK, or specific primers. This procedure yielded 1,176 bp of DNA sequence, including the entire predicted S. entomophila rpoS gene. Analysis of the S. entomophila rpoS nucleotide sequence with the computer program DNASIS (Hitachi Software Engineering Co.) predicted an open reading frame of 999 bp encoding a putative protein with a molecular mass of 38.3 kDa. Nucleotide and predicted protein sequences were aligned with known sequences in the GenBank sequence database by using BLAST (1). The predicted RpoS protein of S. entomophila showed overall identities to the RpoS proteins of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (94%), E. coli (93.7%), Shigella flexneri (90.6%), and P. fluorescens (75%) (respective GenBank EMBL database no. X77752, U29579, P35540, and U34203).

Creation and description of an S. entomophila rpoS mutant.

An rpoS-negative mutant strain of BC4B was created to assess whether RpoS is involved in the amber disease process. A 680-bp BamHI fragment of pSERS1 was replaced with a 1.4-kb BamHI kanamycin marker cassette from pNK2859 (9) to create clone pSERS3 (Fig. 1). Homologous recombination between the interrupted rpoS allele of pSERS3 and the functional rpoS allele of BC4B created strain BC4BRS. Recombination was confirmed by Southern hybridization (data not shown). The presence of pADAP in BC4B and BC4BRS was confirmed by the preparation of plasmid DNA from these strains by the method of Kado and Liu (8).

RpoS is responsible for the expression of numerous proteins in E. coli during the stationary phase (13, 22). Similarly, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of total cell proteins expressed during stationary phase by BC4B and BC4BRS showed many significant differences (data not shown) indicating the pleiotrophic effect of the rpoS mutation in S. entomophila.

Two differences were noted between the S. entomophila rpoS mutant created during this study and rpoS mutants of E. coli. Firstly, E. coli possesses two distinct catalases-hydroperoxidases, HPI(katG) and HPII(katE), of which HPII expression is regulated by rpoS (15, 16). In comparison, S. entomophila appears to possess a single, highly active catalase that is produced in similar amounts by BC4B and BC4BRS. Secondly, the ability of S. flexneri and E. coli to withstand several hours below pH 3 during stationary phase is regulated by rpoS (23). In contrast, viable cell counts of BC4B and BC4BRS dropped away rapidly below pH 4.5, the point at which even log phase E. coli and S. flexneri cells can survive. Therefore, it appears that BC4B does not possess at least two of the known rpoS-regulated stationary phase survival mechanisms of E. coli and S. flexneri.

The role of RpoS in the amber disease process.

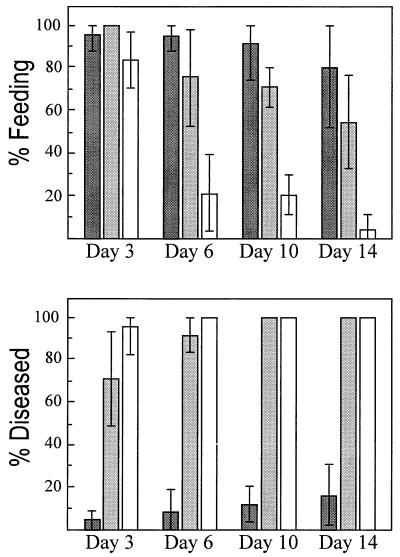

Bioassays were carried out as described previously (4) to compare the ability of BC4B and BC4BRS to cause amber disease in grass grub larvae (Fig. 2). Larvae infected with BC4BRS became amber colored, suggesting that development of this symptom is not affected by the mutation of rpoS in S. entomophila. However, most BC4BRS-infected larvae continued feeding and excreting waste, although not to the same extent as uninfected larvae. In contrast, after day 3 of the bioassay, nearly all larvae infected with BC4B had stopped feeding.

FIG. 2.

Feeding and amber coloration assessment of C. zealandica larvae treated with water ( ), BC4BRS (

), BC4BRS ( ), or BC4B (□). Each result is the average of four replicates of six larvae per strain. Error bars represent 99% confidence intervals for those replicates in which variation was observed. Larvae were inoculated on day 1 and assessed for feeding and amber coloration on days 3, 6, 10, and 14. Percentage feeding and diseased represent, respectively, the number of grubs still feeding and the number of grubs that had become amber colored within each replicate.

), or BC4B (□). Each result is the average of four replicates of six larvae per strain. Error bars represent 99% confidence intervals for those replicates in which variation was observed. Larvae were inoculated on day 1 and assessed for feeding and amber coloration on days 3, 6, 10, and 14. Percentage feeding and diseased represent, respectively, the number of grubs still feeding and the number of grubs that had become amber colored within each replicate.

The S. entomophila nonpathogenic mutant UC24 possesses a TnphoA insertion within a 5.3-kb region of DNA containing the locus amb2 (17). Two genes within this locus, anfA1 and anfB, are thought to be essential for the antifeeding effect (18). Because the TnphoA insertion of UC24 is located within or near to the anfA1 gene, we decided to investigate whether the expression of anfA1 is affected by mutation to rpoS in S. entomophila.

A 1,050-bp HindIII fragment from the amb2 region, including the region upstream of the anfA1 translation start site and the first 20 predicted codons of anfA1, was cloned with fusion vectors pLacZ1, pLacZ2, and pLacZ3 (7, 17). Plasmid DNA from blue colonies on media containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (Xg) was assessed by using KpnI digestion to ensure correct orientation of the insert DNA within the vector. The correct reading frame for anfA1::lacZ fusion was provided by pLacZ3. Because S. entomophila has inherent resistance to ampicillin, an omega cassette encoding chloramphenicol resistance (3) was ligated to the EcoRI site of the pLacZ3 multicloning site upstream of the anfA1 fusion fragment to create plasmid pALC. The cassette also provided additional translational and transcriptional stop signals to ensure that expression of lacZ is dependent only on information provided within the anfA1 fusion fragment. An omega cassette encoding chloramphenicol resistance was also introduced to pLacZ3 to create plasmid pLC, which is devoid of the anfA1 fusion fragment and thus served as a control to determine background β-galactosidase activity.

To determine the effect of a rpoS mutation in S. entomophila on the expression of anfA1, both pLC and pALC were introduced to BC4B and BC4BRS by electroporation. Cultures of these strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (30 μg ml−1). Samples were taken when cultures had reached mid-exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.3 to 0.6) and after 24 h (OD600, 3.4 to 3.6). Cells were rinsed three times with minimal A media, and β-galactosidase expression was measured by the method of Miller (14). Viable cell counts on LB agar plates and LB agar plates supplemented with ampicillin and chloramphenicol indicated that plasmid maintenance was approximately 100% for exponential phase cells but dropped after 24 h of culture growth, to 50 to 80% for pLC and to 12 to 20% for pALC. Therefore, β-galactosidase activity was determined as nanomoles of O-nitrophenol/min/106 plasmid-containing cells.

The expression of anfA1 was found to be low during the exponential phase and was induced to a high level after 24 h of growth (Table 2). anfA1 expression in an rpoS mutant, measured as β-galactosidase activity per 106 cells, is approximately 25 times greater in stationary-phase cells than exponential-phase cells. In BC4B, anfA1 expression is approximately four times greater in the stationary phase than in BC4BRS. The data presented in Table 2 indicate that stationary-phase-specific expression of anfA1 is predominantly rpoS dependent, but a residual level of expression is rpoS independent, and this may be due to regulation by other sigma factors. It is therefore proposed that rpoS mediates its influence on the antifeeding potential of S. entomophila, at least in part, via its effect on the expression of anfA1. A residual level of rpoS-independent anfA1 expression would result in low-level production of the antifeeding toxin during stationary phase. A reduced dose of antifeeding toxin may be responsible for the observation that C. zealandica larvae infected with BC4BRS continue to feed, but less actively than untreated larvae (data not shown). Indeed, Nunez-Valdez and Mahanty (17) found that repeated feeding of C. zealandica larvae with E. coli cells containing the amb2 locus on a multicopy plasmid was necessary for the expression of the antifeeding phenotype, indicating that the toxin may act in a dose-dependent manner.

TABLE 2.

lacZ::anfA fusion expression in BC4B and BC4BRSa

| Growth phase | Strain | β-Galactosidase activity

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| pLC | pALC | ||

| Exponential | BC4B | 1 | 36 |

| BC4BRS | 1 | 44 | |

| Stationary | BC4B | 10 | 5,032 |

| BC4BRS | 9 | 1,223 | |

β-galactosidase activity was measured as nanomoles of O-nitrophenol/min/106 plasmid-containing cells by the method of Miller (14). Individual assays were measured in triplicate, and the activity units of three separate assays were averaged for each data point.

RpoS has been shown to have a role in the transcription of the plasmid-carried virulence operon spvRABCD, which is common to many Salmonella serovars (2, 10). In addition, the production of antifungal compounds and the suppression of fungal pests are influenced by RpoS in the potential biological control bacterium P. fluorescens Pf-5 (21). The present study has determined that RpoS influences the antifeeding component of amber disease and the expression of the antifeeding gene anfA1, which is required by S. entomophila BC4B for full biological control of C. zealandica.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence data for the S. entomophila rpoS gene described in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. U35777.

Acknowledgments

An equipment grant from the New Zealand Lottery Board is gratefully acknowledged.

We thank R. Kolter for the generous gift of strain ZK918, Mark Silby for helpful discussions, and AgResearch, Lincoln, for providing insect larvae and for carrying out a number of bioassays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang F C, Libby S J, Buchmeier N A, Loewen P C, Switala J, Harwood J, Guiney D G. The alternative ς factor KatF (RpoS) regulates Salmonella virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11978–11982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fellay R, Frey J, Krisch H. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA fragments designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1987;52:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glare T R, Corbett G E, Sadler T J. Association of a large plasmid with amber disease of the New Zealand grass grub, Costelytra zealandica, caused by Serratia entomophila and S. proteamaculans. J Invertebr Pathol. 1993;62:165–170. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grkovic S, Glare T R, Jackson T A, Corbett G E. Genes essential for amber disease in grass grubs are located on the large plasmid found in Serratia entomophila and Serratia proteamaculans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2218–2223. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2218-2223.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson T A, Huger A M, Glare T R. Pathology of amber disease in the New Zealand grass grub, Costelytra zealandica (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) J Invertebr Pathol. 1993;61:123–130. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain C. New improved lacZ gene fusion vectors. Gene. 1993;133:99–102. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90231-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kado C I, Liu S T. Rapid procedure for the detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1365-1373.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleckner N, Bender J, Gottesman S. Uses of transposons with emphasis on Tn10. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:139–179. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04009-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kowarz L, Coynault C, Robbe-Saule V, Norel F. The Salmonella typhimurium katF (rpoS) gene: cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of spvV and spvABCD virulence plasmid genes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6852–6860. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6852-6860.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. Growth phase-regulated expression of bolA and morphology of stationary-phase Escherichia coli cells are controlled by the novel sigma factor ςS. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4474–4481. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4474-4481.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loewen P C, Hengge-Aronis R. The role of the sigma factor ςS (KatF) in bacterial global regulation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:53–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCann M P, Kidwell J P, Matin A. The putative ςS factor KatF has a central role in development of starvation-mediated general resistance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4188–4194. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4188-4194.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulvey M R, Sorby P A, Triggs-Raine B L, Loewen P C. Cloning and physical characterisation of katE and katF required for catalase HPII expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1988;73:337–345. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulvey M R, Loewen P C. Nucleotide sequence of katF of Escherichia coli suggests KatF protein is a novel ς transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9979–9991. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.23.9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nunez-Valdez M E, Mahanty H K. The amb2 locus from Serratia entomophila confers anti-feeding effect on larvae of Costelytra zealandica (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) Gene. 1996;172:75–79. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nunez-Valdez M E. Identification and analysis of the virulence factors in Serratia entomophila causing amber disease to the grass grub Costelytra zealandica. A molecular genetics approach. Ph.D. thesis. Christchurch, New Zealand: University of Canterbury; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Callaghan M, Jackson T A, Mahanty H K. Selection, development and testing of phage-resistant strains of Serratia entomophila for grass grub control. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 1992;2:297–305. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarniguet A, Kraus J, Henkels M D, Muehlchen A M, Loper J E. The sigma factor ςS affects antibiotic production and biological control activity of Pseudomonas fluorescens PF-5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12255–12259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schellhorn H E, Audia J P, Wei L I C, Chang L. Identification of conserved, RpoS-dependent stationary-phase genes of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6283–6291. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6283-6291.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Small P, Blankenhorn D, Welty D, Zinser E, Slonczewski J I. Acid and base resistance in Escherichia coli and Shigella flexneri: role of rpoS and growth pH. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1729–1737. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1729-1737.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Upadhyaya N M, Glare T R, Mahanty H K. Identification of a Serratia entomophila genetic locus encoding amber disease in New Zealand grass grub (Costelytra zealandica) J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1020–1028. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.1020-1028.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zambrano M M, Siegele D A, Almirón M, Tormo A, Kolter R. Microbial competition: Escherichia coli mutants that take over stationary phase cultures. Science. 1993;259:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.7681219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]