Abstract

Background

In order to End the HIV Epidemic (EHE) and reduce the number of incident HIV infections in the US by 90%, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake and persistence among cisgender women, particularly racial and ethnic minority women, must be increased. Medical providers play a pivotal role across the PrEP care continuum.

Methods

In this qualitative study, guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), we explored healthcare provider perspectives on facilitators and barriers to PrEP implementation strategies for Black cisgender women in the Midwest United States. Data were analyzed using a deductive thematic content analysis approach

Results

A total of 10 medical providers completed individual qualitative interviews. Using the CFIR framework, we identified intervention characteristics (cost, dosing, adherence), individual patient and provider level factors (self-efficacy, knowledge, attitudes), and systematic barriers (inner setting, outer setting) that ultimately lead to PrEP inequalities. Implementation strategies to improve the PrEP care continuum identified include provider training, electronic medical record (EMR) optimization, routine patient education, and PrEP navigation.

Conclusion

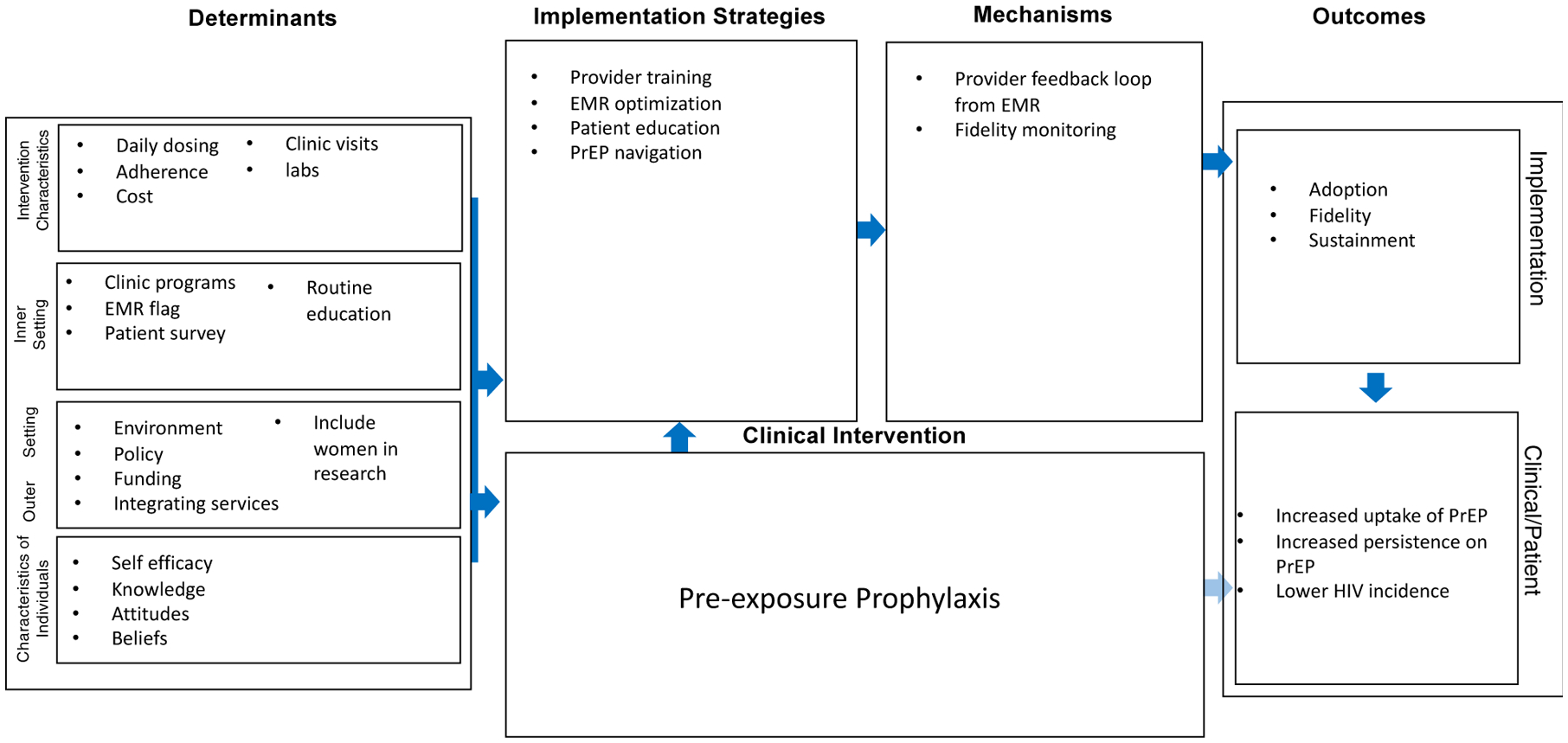

This study provides: (1) medical provider insight into implementation factors that can be modified to improve the PrEP care continuum for Black cisgender women; and (2) an implementation research logic model to guide future studies.

Keywords: HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis, women’s health, qualitative research, clinical decision making, patient care

Background

The Midwest United States (US) has an HIV incidence rate of 7.0 per 100,000 and accounts for 13% of new diagnoses nationwide.1 Like the South, Northeast, and the West, rates of HIV diagnoses in the Midwest decreased from 2015 to 2019.1 Despite these overall declines, there remains a need for a comprehensive approach to eliminating racial disparities in HIV infection in the Midwest, particularly among cisgender women as the rate of Black women living with HIV is 18 times that of White women.2 The Midwest region contains several large urban poverty areas sampled by the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System (NHBS), including Chicago, Detroit, and St. Louis, which found high prevalence among cisgender women and an inverse relationship between HIV prevalence rates and socioeconomic status (SES).3

More than a million Americans meet clinical eligibility guidelines for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), yet less than 15% of these individuals have received a prescription.4 Significant disparities in PrEP use exists in the US, with cisgender women making up a disproportionately low percentage of PrEP users compared to men.5 The PrEP-to-need ratio (defined as number of PrEP prescriptions divided by number of new HIV diagnoses) for women was a third of that for men (2.3 for women vs 6.9 for men) in 2019.2,6 Black cisgender women are particularly underrepresented among PrEP users, despite accounting for two thirds of infections among women in the United States in 2018.7 In order to End the HIV Epidemic (EHE) and reduce the number of incident HIV infections in the US by 90%, PrEP uptake and persistence among women must be increased.8 Medical providers play a pivotal role across the PrEP care continuum.9–11 The continuum is divided into three distinct phases: 1) awareness; 2) uptake; 3) adherence and persistence.1,3,12

Optimizing patient access, acceptance, and adherence to PrEP requires further engagement of individuals at the highest risk of HIV infection, which oftentimes relies on healthcare providers.10,13 Several barriers to prescribing PrEP have been reported by medical providers, such as difficulty determining patient eligibility; logistical issues related to implementation, including the challenges of repeated laboratory testing while on PrEP and ample time needed for proper risk and adherence counseling; and concerns about patient ability to adhere to daily medication and follow-up appointments.9,10,14 Medical providers have also recognized that structural barriers, stigma, and interpersonal biases, can interfere with accessing and engaging priority populations.11,15–17 These barriers result in missed opportunities to prescribe PrEP to priority populations, including Black cisgender women.

Few prior studies have focused on provider perspectives of PrEP uptake and persistence among Black cisgender women in the US, and none have focused on the Midwest. Kimmel et al. conducted qualitative interviews with providers to identify barriers and facilitators to PrEP uptake for Black cisgender women, and found time constraints, reluctance, and discomfort with counseling as barriers and leadership support, centralized PrEP coordinators, and alignment of PrEP services with the organizational mission as facilitators.18 A separate study identified barriers and facilitators impacting the PrEP care continuum in Kenya among girls and young women by conducting key informant interviews with staff, providers, and medical leaders, results highlight the importance of using a safe space model, peer mentors, including parents and partners in PrEP education, and active stakeholder involvement.19

Using Implementation Science methods and frameworks can guide investigation and understanding of PrEP implementation, including determinants of success or challenge. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) groups barriers and facilitators for PrEP implementation in five domains: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, individual characteristics, and process.20 Intervention characteristics include aspects of PrEP that may impact uptake and persistence, for example, complexity of taking a daily pill may serve as an intervention barrier.21 Outer setting refers to external influences on PrEP implementation including policy and clinical guidelines.21 Inner setting includes the characteristics of the implementing clinic, such as the programs or staff available to support PrEP uptake and persistence.21 Individual characteristics include individual’s beliefs, knowledge, and other personal attributes that affect PrEP implementation.21 Finally, process of implementation refers to the planning, execution, and evaluation of PrEP implementation.21 Applying the CFIR framework can help identify where key changes can be made and highlight strategies that are effective to improve PrEP implementation. This framework acknowledges health system and provider level elements - both interpersonal factors and factors external to the individual provider within their clinic system - and offers recommendations for improvements along the PrEP care continuum among Black cisgender women across multiple levels. Sales et al. applied CFIR to study PrEP implementation in family planning clinics in the Southern United states via an online quantitative survey.22,23 The CFIR framework is useful to identify and categorize barriers and facilitators that influence implementation outcomes, in this case, Sales et al. highlight that outer (availability of resources) and inner setting characteristics (supportive climate of HIV prevention practices, supportive leadership) rather than individual characteristics (knowledge) were the most salient factors associated with readiness to provide PrEP in family planning settings in the Southern US.23 Identifying CFIR characteristics that impact PrEP implementation outcomes is vital to improving uptake and persistence among Black cisgender women.

In this qualitative study, guided by CFIR, we explored provider perspectives on facilitators and barriers to PrEP implementation among Black cisgender women in the Midwest US. Medical providers who prescribe PrEP at community health clinics were interviewed about the successes and challenges with strategies currently implemented at their institution to increase PrEP initiation for Black cisgender women, with the goal of creating an implementation research logic model to organize determinants which may require new or expanded interventions, align implementation strategies, and propose outcomes to monitor and assess impact.

Methods

Potential participants were selected using electronic medical record data to identify medical providers who had prescribed PrEP and had a patient panel that included Black cisgender women. Providers were eligible to participate if they were also: 1) employed as a prescribing provider at an AllianceChicago affiliated clinic; 2) willing and able to provide consent. Prior to participation informed consent was obtained; the IRBs from University of Chicago, Lurie Children’s Hospital and Howard Brown Health reviewed and approved all study procedures.

A semi-structured interview guide was adapted from the CFIRguide.org qualitative tool and designed to capture providers’ perspectives and experiences for each CFIR domain across the PrEP care continuum. Table 1 provides sample questions for each CFIR domain.

Table 1.

Qualitative Interview Guide Sample Questions by CFIR Domain

| CFIR domain | Sample question |

|---|---|

| Intervention Characteristics |

|

| Individual Characteristics |

|

| Inner Setting |

|

| Outer setting |

|

Interviews were digitally audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using a deductive thematic content analysis approach.24,25 Dedoose, an online mixed-methods software, was used to analyze the data.26 A preliminary code book was created based on the interview guide, CFIR domains, and a transcript selected at random, all coders (N=3) reviewed and revised the preliminary codes. Next, the codebook was applied by the primary coder to two transcripts, secondary coders coded a subset of excerpts selected at random using the ‘test’ feature in Dedoose and achieved reliability measured by Cohen’s Kappa at >.80. Most divergences occurred due to omission and upon review were quickly rectified to 100% agreement. Codes were then applied to all 10 transcripts and were reviewed by all 3 coders for consensus of code application. Finally, themes were defined based on CFIR levels and clustering of code application. Patterns in themes, including consistent repetition and limited new topics, ensured saturation was achieved.

Results

Between December 2019 and February 2020, a total of 10 medical providers representing 3 different agencies and 7 clinic sites completed individual qualitative interviews (Table 2). All participants had prescribing ability and were actively seeing patients. Patient loads per month varied from 48 to 500, with a mean of 206.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Job title | |

| Physician | 40% (4) |

| Nurse Practitioner | 50% (5) |

| Physician Assistant | 10% (1) |

| Length of time employed at clinic | |

| 0–2 years | 40% (4) |

| 3–4 years | 40% (4) |

| 5 + years | 20% (2) |

| Percent of patients who are Black cisgender women | |

| 5–10% | 30% (3) |

| 11–15% | 40% (4) |

| 16–20% | 20% (2) |

| more than 20% | 10% (1) |

| Determination of PrEP eligibility for Black cisgender women | |

| standardized risk assessment | 30% (3) |

| personalized sexual behavior questions | 60% (6) |

| discuss HIV prevention and PrEP only if prompted by patient | 10% (1) |

| Percent of Black Cisgender women prescribed PrEP | |

| less than 5% | 90% (9) |

| 5% or more | 10% (1) |

PrEP (CFIR: Intervention characteristics)

Participants identified several intervention characteristics that impact uptake and persistence among Black cisgender women. Although alternate delivery modes and schedules are on the horizon, current guidelines require prescribing daily dosing of PrEP in a tablet form. Daily dosing and need to adhere was highlighted as an intervention characteristic that was a barrier to uptake and persistence:

In general, I think people just don’t always like to follow up. They just don’t wanna take their pills every day… people just forget

(P3)

Trying to take a daily pill is hard. It’s the same reason why people do poorly with daily oral contraception.

(P5)

I always ask about pills missed in the last seven and 30 days and most of the time it’s, you know, maybe one or two… occasionally I’ll have the person who’s like, “Oh, I missed 15 in the last month.”

(P4)

Further, drug side effects and cost of the medication were brought up as barriers to PrEP implementation. Participants spoke about Black cisgender women seeing information about side effects on social media:

Yeah, we’ve actually done a lot of internal dialogue around that about like bringing this up proactively with our patients, just like because so many have seen it [information about side effects] in terms of Truvada on Facebook about kidney issues and stone issues.

(P8)

Participants also talked about the duration and intensity of side effects, stating for most people side effects are mild and resolve in the first two weeks of PrEP use:

Next is the side effects. Some people have some GI upset. Upset stomach for, like, ten days.

(P6)

Despite this fact, the threat of experiencing side effects is a barrier to uptake. Perceived and actual cost of the intervention is also a barrier to uptake:

…cost would maybe be one [barrier]. But because we have all of these assistance programs and then, even for people who have a very low income and are not on Medicaid, we have sliding scale at the clinic as well.

(P9)

also, everyone believes that it’s very expensive. A lot of misconception around the cost.

(P3)

And then there is an issue – there is an issue with paying for labs because they do need to do quarterly or every four months lab, which can get kinda pricey, depending on patient’s insurance companies.

(P4)

Further, visit length, labs required, and return visit frequency were highlighted as barriers to persisting on PrEP:

… it’s sort of the timing of getting the refill and scheduling all the clinic visits. I know that sometimes comes up where they’re like, “Oh, yeah, I tried to get this visit with you and then, my schedule was difficult,” and it was hard …

(P10)

Self-efficacy, knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs (CFIR: Individual characteristics)

Providers reported several perceived patient-level barriers across the PrEP care continuum that are categorized as individual characteristics. Impacting PrEP awareness and uptake, providers reported perceived low patient PrEP knowledge, lack of disclosure during sexual history taking, and a low HIV risk self-perception. For example, one provider stated that although male patients have asked about PrEP and often know what PrEP is this contrasts with their experience with Black cisgender women,

I don’t think I’ve ever had a cis female patient come in and know what PrEP is.

(P6)

Another participant stated that although some of their patients who are Black cisgender women do know about PrEP, it’s less than half and much lower awareness compared to other subpopulations:

Maybe it’s like more 40% actually know or have heard about it before. I mean most of my MSM and trans women have 100% heard about PrEP by this point. The messaging is put in pretty good for those communities.

(P2)

Providers discussed that they believe some patients do not disclose behaviors or circumstances that may increase their HIV risk and they perceive patients have a low personal HIV risk perception.

It’s a difficult conversation to have when some cis women really don’t perceive any sort of risk of HIV acquisition. And it’s difficult to move that needle to discuss, actually, that there is inherent risks out there.

(P8)

The barriers come in as what they perceive their risk to be. So, that is my biggest barrier is that the cis women do not feel that they’re possibly at risk for it [HIV].

(P6)

I think there’s an education in terms of what people’s risk factors are that they don’t know about. I think MSM have a very good idea of what their risk factors are or have a better idea. Whereas, maybe people who are not in that group aren’t aware that certain things are risk factors for them.

(P4)

Providers also mentioned they believe that medical mistrust, patient reported changes in partner status, and pregnancy impact PrEP uptake and persistence among Black cisgender women.

I think there is a lot, I think a lot of medical mistrust…like Tuskegee…I would say medical mistrust

(P5)

I think when you have a white male come in in a lab coat and tell you to take this pill, with African American hesitancy to trust the medical field that is another underlying issue.

(P6)

Sometimes, it’s that they no longer need PrEP. Sometimes, people will be like- their relationship status will change and they will say I don’t need this anymore.

(P10)

I did have one that became pregnant, and she stopped [PrEP].

(P6)

In contrast, participants did highlight several perceived individual level facilitators of PrEP uptake among Black cisgender women, including being open to learning about PrEP, seeking sexual and reproductive health services, and high levels of self-advocacy and self-efficacy. For example, one participant mentioned that some Black cisgender women come in and directly ask about PrEP:

So, the best … is a woman who comes in and says, “I’m interested in PrEP,” or, “Can you tell me more about PrEP?”

(P5)

Further, one provider mentioned some Black cis women are experienced taking daily birth control and use reminder apps to assist in adherence to daily PrEP:

I think patients who do [persist on PrEP] use the [birth control] pill or the reminder apps… that helps them adhere

(P7)

In terms of provider-level individual characteristics that are barriers to uptake, participants reported lack of training on PrEP prescription, discomfort in talking about PrEP, and their own judgement and perceptions of patients. Providers mentioned that sexual history taking is an important tool for understanding HIV risk and acts as a pathway to discussing PrEP, however, many participants felt as though they needed additional training and support to take a comprehensive sexual history for Black cisgender women. While four of the study participants reported high levels of comfort and familiarity with PrEP, six reported lower levels of comfort with discussing PrEP with Black cisgender women:

I would rate my comfort [discussing PrEP] as low. Only because I just don’t know it very well. Not because– I have no problems talking about sex

(P1)

I think my comfort level is pretty poor. A lot of the men who have sex with men who come in asking for PrEP, they already know about it. And I feel really comfortable with that conversation. I just don’t have it too often with cisgender women, so I think, my comfort level, being part of the LGBT community, like I feel a little bit more comfortable having that conversation with those patients, whereas, I don’t want to make that person, a cisgender woman, feel uncomfortable.

(P4)

Further, providers in our study discussed how their judgement and perception of patients impact PrEP uptake. For example, one provider stated they really didn’t discuss PrEP with Black cisgender women unless there were extenuating circumstances:

I’m not really pushing it unless there’s extenuating circumstances, and frankly I’ve only had one ciswoman where I really felt like- well, she wanted it, so that doesn’t really help, but I haven’t had a ciswoman who like- came in and then we started talking and I’m like; you really need to be on PrEP

(P5)

A different provider stated that visit attendance in the past would influence their discussion of PrEP:

If I wasn’t sure that she was going to be able to follow up in clinic […] if I saw someone with a track record of like probably six no shows in the last year, I probably wouldn’t recommend PrEP to that person because I don’t think they would be able to come back every three months to monitor everything

(P10)

Participants reported providers can establish trust with Black cisgender women as a way to support uptake and persistence, emphasizing that a strong relationship builds open communication and ongoing dialogue about HIV prevention. Finally, providers also suggested additional training on sexual history taking and PrEP would be beneficial and a facilitator to improve PrEP uptake.

Clinic, programs, organization (CFIR: Inner setting)

The inner setting in the CFIR framework includes the clinics and clinic programs. Participants discussed current programs at their clinics as well as suggested programs that could be implemented to support PrEP uptake and persistence for Black cisgender women. Many of the current programs were seen to have universal impact on uptake and persistence among patients and were not specific to Black cisgender women. Current programs included PrEP navigation, same day starts, routine PrEP education, and co-located pharmacies. Programs to implement in the future included a risk assessment survey or screening tool to assist in identifying PrEP-eligible women, a flag in the electronic medical record (EMR), and an ability to view STI history in the EMR. Programs to implement in the future were discussed as tailored specifically to increase uptake and persistence among Black cisgender women.

The majority of participants emphasized the strength of PrEP navigation services as a facilitator to PrEP engagement among Black cisgender women. PrEP navigators are staff members at clinics who assist patients in accessing PrEP, from navigating pharmacy pick-up, assisting with co-pay and reimbursement programs, to scheduling appointments and answering questions. Navigators provide much needed support to patients and alleviate the time burden of managing PrEP on clinicians. Providers emphasized the important role navigators play in uptake and persistence.

So utilizing the PrEP navigator is super helpful…they have more time to sit with patients and take them through the logistics, going through adherence. They’ll go through ways to remember to take the pills and strategies that are important

(P8)

The PrEP navigator helps get [insurance] coverage… also PrEP retention, so they make calls to try to get them [patients] to come back.

(P3)

So, I literally am so- we’re so lucky here- all I have to do is prescribe it. Someone else [PrEP navigators] is going to figure out the roadblocks and hurdles

(P4)

In addition to being supported by PrEP navigators, providers in our study emphasized the importance of nursing staff and health educators in providing routine PrEP education to all patients, inclusive of Black cisgender women.

I think actually, I’ve witnessed some of the conversations, just because I do have some oversight capacity with the walk-in services. And I’ve been very impressed with how nursing and health educators present PrEP to every patient, just so that people are aware. Creating that awareness, I think, is really key. And then, people can decide if it’s something that’s good for them and their bodies and their health. Get the messaging out is super important.

(P8)

A few participants mentioned the availability of walk-in services and same day starts for PrEP as a way to increase uptake and support persistence.

We do see patients on a walk-in service. It provides, STI screening and reproductive health services for contraception. And we do offer same day PrEP. And then, we do have primary care patients who also have access to PrEP

(P8)

Several participants in our study mentioned the idea of an assessment or screening survey to identify Black cisgender women as PrEP eligible patients. This was an idea that had not yet been implemented in the clinics.

I think if there were some way for them to identify themselves as high risk before they got into the room, it might be a little bit easier to start them on PrEP. So, for example, if there was like a survey that they did as they were waiting for any women’s visit – women’s health visit, you know, like oh, you’re getting your PAP smear today. Oh, you’re coming in for STD testing or vaginal discharge or dysuria. Fantastic. Here’s a quick survey you could fill out that has four questions. And like bring it in to your healthcare provider and we’ll discuss it.

(P3)

And if that was sort of like a process that happened before they came in the room so that I could review the survey then, maybe that might start the conversation in a way that might identify more people who would benefit from PrEP but it also might help convince them that they could benefit from it.

(P10)

Providers also suggested using the EMR to alert them of a potential candidate for PrEP.

“I think it would be really great to have some sort of flag in the electronic health record, some sort of way to prompt me when I have someone with chlamydia or someone with gonorrhea, or anything[…]to remind me to think about PrEP or to help guide m on how to do that”

(P1)

In addition to EMR alerts, some participants mentioned it would be helpful to be able to easily see STD history of patients in the EMR. This would be a way to not only determine PrEP eligibility for Black cisgender women, but also to understand a patient’s sexual health history.

“Maybe if there was a way for me to easily see how many times somebody’s been treated for an STI”

(P5)

Environment, policy (CFIR: Outer setting)

In terms of the outer setting which encompasses the broader environment and policy, participants brought up lack of inclusion in clinical research, lack of funding to support HIV prevention services, and the missed opportunity of not co-locating services with either on-site pharmacies or by embedding PrEP into women’s health centers and family planning clinics.

One participant expressed that clinical research doesn’t always include cisgender women, which impacts the uptake of PrEP.

I think this is further perpetuated by the DISCOVER trial, you know, that we recently released for the TAF regimen or the Descovy, in which case, cis women were not included in the research. It sort of further perpetuates the idea that this is not something that is meant for them- like as the target population.

(P2)

Further, a participant brought up the lack of funding and resources allocated to HIV prevention services contrasting it with funding available for HIV treatment.

We have all those resources available for HIV positive patients. But we don’t have any for HIV negative.

(P6)

Finally, participants highlighted the importance of co-locating services to reduce patient burden.

I think there is a lot of missed opportunities at places where traditionally women are getting services…that maybe PrEP isn’t their main focus. I think there can be a lot of missed opportunities in those contacts where it can be at least part of like the dialogue, even if it’s not prescribed, that people are getting the information about, is this right for you, and here’s where you can go to receive those services.

(P8)

Implementation Research Logic Model

Through analyzing the information gained in the qualitative interviews with providers, our study team developed an implementation research logic model (IRLM) to guide implementation and evaluation of strategies to improve PrEP uptake and persistence among Black cisgender women. The CFIR determinants are reported above by level and in the IRLM (Figure 1). Implementation strategies identified include provider training, EMR optimization, patient education and PrEP navigation. Mechanisms to support strategies include establishing a provider feedback loop using EMR data, which would allow providers to reflect on their PrEP identification and prescription patterns and fidelity monitoring will ensure implementation strategies are being implemented as indicated. We hypothesize these strategies would increase key implementation outcomes including adoption, fidelity, and sustainment; and result in improvement in clinical outcomes including an increased uptake of PrEP, increased persistence on PrEP, and overall lower HIV incidence. The IRLM can inform and guide future research in this area.

Figure 1.

Implementation Science Research Logic Model to Improve PrEP Uptake and Persistence among Black Cisgender Women

Discussion

Guided by CFIR, we explored barriers and facilitators to PrEP uptake and persistence among Black cisgender women from the perspective of medical providers in community health clinics. CHCs are the primary source of healthcare for many women who are vulnerable to HIV, and studies have shown that many women prefer to receive PrEP care from their trusted primary care providers.27 However, rates of PrEP prescription to Black cisgender women at community health centers remain low, even in settings where implementation strategies for PrEP are already in place. While others have investigated providers’ perspectives regarding barriers and facilitators to prescribing PrEP in general, our study is unique in that it specifically focuses on prescription of PrEP for Black cisgender women, a group that is disproportionately under-represented among PrEP users, and provides perspectives of providers who are embedded in a supportive environment in the Midwest US yet still face challenges to implementation.

In addition to identifying barriers and facilitators to PrEP provision and care, providers have offered several training recommendations for improving equity in PrEP uptake and persistence. As there is growing evidence that unconscious stereotypes impact PrEP provision, it is important to engage providers in ongoing cultural competence and anti-racism training to increase their comfort and capability taking culturally sensitive sexual histories.11,15,28,29 Hull et al., established providers willingness to prescribe PrEP to Black women was contingent on their racial attitudes.30 Thus it is important that future standardize provider trainings contain anti-racism content alongside content such as how to take a comprehensive sexual history.

Along with individual patient and provider level factors, providers also experienced intervention-specific challenges and systematic barriers (inner, outer setting) that ultimately lead to PrEP inequalities. In congruence with previous studies, participants in our study encountered obstacles in identifying PrEP eligible women and in supporting patients on PrEP in terms of tracking and scheduling appointments.28 Medical providers in our study discussed the need for increased support with routine PrEP education, as well as support in navigating costs, subsequent visits, and adherence counseling to support PrEP persistence.9,28,31 As an implementation solution, providers have identified specific staff members, such as PrEP navigators and health educators, as facilitators for PrEP uptake and persistence.32,33 Little is known about how the combination of these implementation strategies proposed by medical providers would ultimately impact PrEP outcomes among Black cisgender women. Future studies are needed to evaluate implementation strategies on the uptake and persistence of PrEP.

The strengths of this study include the inclusion of multiple community health clinics, various frontline healthcare providers, the rigorous nature in which it was conducted by recording data objectively through audio and professional third party transcription, and using a documented coding scheme for analysis.34 However, the results need to be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. This qualitative study was conducted in a single urban jurisdiction, primarily from a sexual-health focused clinic system with extensive PrEP navigation services, thus results may not generalize to other settings. Finally, providers who decided to take part in the study may have been different than those who opted not to take part, however, we are unable to assess this difference. To reduce the likelihood of volunteer bias, the study team ensured anonymity of participants and offered flexible interview times including nights and weekends.

This study is the first to apply the CFIR framework to exploring barriers and facilitators to PrEP implementation, inclusive of uptake and retention, among Black cisgender women in the Midwest. Compared to prior studies among providers that included those who never prescribed PrEP, participants in this study were experienced with prescribing PrEP and provided unique insights into implementation among Black cisgender women. Our results advance the literature on implementation and scale up of PrEP for Black cisgender women.

Conclusion

To improve PrEP uptake and retention among Black cisgender women at greatest risk of HIV infection, key interventions are needed to address provider-level barriers as well as to support patient-level intervention. Based on our results, we highlight provider education, PrEP navigation, and EMR flags as intervention to better support providers, along with patient education. Subsequent research is needed to develop, implement, and evaluate these strategies to improve the PrEP care continuum for Black cisgender women.

Evidence-based innovation: Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

Innovation recipients: HIV-negative Black cisgender women

Setting: Community health clinics in the Midwest United States

Implementation gap: PrEP uptake and persistence among Black cisgender women has been slow; medical providers play a key role in supporting the PrEP care continuum.

Primary research goal: Identify determinants of implementation

Implementation strategies: Conduct ongoing training (for providers and patients); Develop and organize quality monitoring systems; Prepare patients to be active participants; Intervene with patients to enhance uptake and adherence.

Funding

This work was supported by an administrative supplement to the Third Coast Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH-funded program (P30 AI117943).

References

- 1.Control CfD, Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2019. Vol. 32. 2019. HIV surveillance report. Published May 2021. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PS, Woodyatt C, Koski C, et al. A Data Visualization and Dissemination Resource to Support HIV Prevention and Care at the Local Level: Analysis and Uses of the AIDSVu Public Data Resource. J Med Internet Res. Oct 23 2020;22(10):e23173. doi: 10.2196/23173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denning P, DiNenno E. Communities in crisis: is there a generalized HIV epidemic in impoverished urban areas of the United States. 2010:

- 4.Smith DKVHM, Grey J. Estimates of adults with indications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by jurisdiction, transmission risk group, and race/ethnicity, United States, 2015. Annals of Epidemiology. 2018;28(12):850–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirschhorn LBR, Friedman E, Christeller C, Greene G, Bender A, Bouris A, Modali L, Johnson AK, Pickett J, Ridgway J. Women’s PrEP Knowledge, attitudes, preferences, and experience in Chicago. presented at: 2019 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2019; Seattle, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegler A, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, Weis K, Pembleton E, Guest J, Jones J, Castel A, Yeung H, Kramer M, McCallister S, Sullivan PS. The Prevalence of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis use and the Pre-exposure Prophylaxis-to-Need Ratio in the Fourth Quarter of 2017, United States. Annals of Epidemiology. 2018;28:841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.HIV Surveillance Report, 2017 (Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; ) (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. Jama. 2019;321(9):844–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.St. Vil NM, Przybyla S, LaValley S. Barriers and facilitators to initiating PrEP conversations: Perspectives and experiences of health care providers. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services. 2019/April/03 2019;18(2):166–179. doi: 10.1080/15381501.2019.1616027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pleuhs B, Quinn KG, Walsh JL, Petroll AE, John SA. Health care provider barriers to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2020;34(3):111–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calabrese SK, Tekeste M, Mayer KH, et al. Considering Stigma in the Provision of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: Reflections from Current Prescribers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. Feb 2019;33(2):79–88. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunn AS, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Oldenburg CE, et al. Defining the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care continuum. AIDS (London, England). 2017;31(5):731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pyra M, Johnson AK, Devlin S, et al. HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Use and Persistence among Black Ciswomen:“Women Need to Protect Themselves, Period”. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2021:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agovi AM-A, Anikpo I, Cvitanovich MJ, Craten KJ, Asuelime EO, Ojha RP. Knowledge needs for implementing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among primary care providers in a safety-net health system. Preventive medicine reports. 2020;20:101266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calabrese SK, Magnus M, Mayer KH, et al. Putting PrEP into Practice: Lessons Learned from Early-Adopting U.S. Providers’ Firsthand Experiences Providing HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis and Associated Care. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer KH, Agwu A, Malebranche D. Barriers to the wider use of pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States: a narrative review. Advances in therapy. 2020;37(5):1778–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold EA, Hazelton P, Lane T, et al. A qualitative study of provider thoughts on implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in clinical settings to prevent HIV infection. PloS one. 2012;7(7):e40603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimmel AL, Messersmith LJ, Bazzi AR, Sullivan MM, Boudreau J, Drainoni M-L. Implementation of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for women of color: Perspectives from healthcare providers and staff from three clinical settings. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services. 2020;19(4):299–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson-Gibson M, Ezema AU, Orero W, et al. Facilitators and barriers to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake through a community-based intervention strategy among adolescent girls and young women in Seme Sub-County, Kisumu, Kenya. BMC public health. 2021;21(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation science. 2009;4(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Safaeinili N, Brown‐Johnson C, Shaw JG, Mahoney M, Winget M. CFIR simplified: Pragmatic application of and adaptations to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) for evaluation of a patient‐centered care transformation within a learning health system. Learning health systems. 2020;4(1):e10201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coleman C, Sales J, Escoffery C, Piper K, Powell L, Sheth A. Primary Care and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Services in Publicly Funded Family Planning Clinics in the Southern United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sales JM, Escoffery C, Hussen SA, et al. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Implementation in Family Planning Services Across the Southern United States: Findings from a Survey Among Staff, Providers and Administrators Working in Title X-Funded Clinics. AIDS and Behavior. 2021;25(6):1901–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernard HR. Qualitative data analysis I: text analysis. Research methods of anthropology. 2002;440448 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padgett DK. Qualitative and mixed methods in public health. Sage publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dedoose Version 8.0.35, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. 2021. www.dedoose.com

- 27.Hirschhorn LR, Brown RN, Friedman EE, et al. Black Cisgender Women’s PrEP Knowledge, Attitudes, Preferences, and Experience in Chicago. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Aug 15 2020;84(5):497–507. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000002377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laborde ND, Kinley PM, Spinelli M, et al. Understanding PrEP Persistence: Provider and Patient Perspectives. AIDS Behav. Sep 2020;24(9):2509–2519. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02807-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Hansen NB, Dovidio JF. The impact of patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): assumptions about sexual risk compensation and implications for access. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(2):226–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hull SJ, Tessema H, Thuku J, Scott RK. Providers PrEP: Identifying Primary Health care Providers’ Biases as Barriers to Provision of Equitable PrEP Services. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2021;88(2):165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Przybyla S, LaValley S, St Vil N. Health Care Provider Perspectives on Pre-exposure Prophylaxis: A Qualitative Study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. Nov-Dec 2019;30(6):630–638. doi: 10.1097/jnc.0000000000000073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, et al. The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis-to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol. Dec 2018;28(12):841–849. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calabrese SK, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. Integrating HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) into routine preventive health care to avoid exacerbating disparities. American journal of public health. 2017;107(12):1883–1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seale C, Silverman D. Ensuring rigour in qualitative research. The European journal of public health. 1997;7(4):379–384. [Google Scholar]