Abstract

BACKGROUND

In Canada, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most frequently occurring liver disease, affecting one in four Canadians. NAFLD can in turn evolve into non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and cirrhosis. No study in Canada has investigated knowledge of NAFLD among physicians.

METHODS

Primary care physicians (PCPs); specialists in internal medicine, gastroenterology, and hepatology; and hepatology nurses who were members of the College of Family Physicians of Canada, Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver, or Canadian Association of Hepatology Nurses were invited to participate in this web-based survey.

RESULTS

Of 650 invited physicians and nurses, 214 (33%) responded and 171 (26%) completed the whole survey. Overall, 51% of the respondents were PCPs, 38% were specialists, and 11% were nurses. Of these, 58% of PCPs, 28% of specialists, and 39% of nurses responded that they were only somewhat familiar or unfamiliar with NAFLD. Moreover, 53% of PCPs, 20% of specialists, and 35% of nurses thought the prevalence of NAFLD in Canada was 15% or less. Also, 42% of respondents thought that NASH could be diagnosed by imaging or blood tests. Finally, more than 40% of PCPs, 22% of specialists, and 33% of nurses thought that metformin and statin were treatments for NASH.

CONCLUSIONS

This survey shows that a significant proportion of Canadian physicians and nurses managing patients with NAFLD are not very familiar with the disease. This study emphasizes the need for further provider education, national practice guidelines, and improved treatment options.

Key Words: Canadian physicians, diagnosis, liver fibrosis, NAFLD, treatment

Introduction

Chronic liver disease is a major health concern in Canada and results in nearly 3,000 deaths per year (1,2). Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represents a disease spectrum that ranges from bland steatosis or non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and significantly contributes to these figures: one in four Canadians has NAFLD (3). Nearly 25% of those with NAFLD develop NASH, which can progress to significant liver fibrosis and to cirrhosis with associated complications, namely liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (4,5). NASH is the second leading indication for liver transplantation in North America, and it is projected to become the first over the next 10 years (6,7). Moreover, NASH is the fastest-rising cause of HCC, the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the world (8).

Our recent modelling on burden of disease in Canada has demonstrated that the frequency of NAFLD will increase by 20% through 2030, with an estimated 9,305,000 cases (3). There will also be an increase of 65% in cases of liver cirrhosis and HCC related to NASH in the next decade (3). These trends are in line with those reported in other Western countries with a similar prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which are the main risk factors for NAFLD (9). Despite these striking figures, a recent study showed that, of 29 countries, none had a national strategy for addressing NAFLD, and only 35% had national guidelines for its management (10). Similarly, Canada has no national strategy or models of care for NAFLD. To build a national strategy around this metabolic disease epidemic, it is essential to have an understanding of the knowledge of and perceived needs pertaining to NAFLD among health care providers. Previous surveys on knowledge of NAFLD in other countries have shown that a significant proportion of physicians do not have sufficient knowledge of how to diagnose and treat the disease (11). Among primary care physicians (PCPs), 58% reported lack of confidence in understanding the disease (12). No such study has been done in Canada. We hypothesized that a significant knowledge gap exists among health care providers regarding best-practice diagnosis and management of NAFLD. Thus, we conducted a web-based survey aimed at investigating knowledge of NAFLD among Canadian physicians (PCPs and specialists) and nurses.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional open survey of Canadian physicians and nurses who manage patients with NAFLD. A comprehensive anonymous survey was developed by GS and distributed among members of the Canadian NASH Network to assess satisfaction and face validity. The Canadian NASH Network is a collaborative organization of health care professionals from across Canada who have a primary interest in enhancing understanding among, care and education of, and research with persons with NAFLD, with a vision of best practices for this disease state (https://cannash.ca). Modifications to the survey were made on the basis of responses and comments to achieve consensus. The final version was six pages long and consisted of 28 items divided into two sections: (1) respondent basic demographics and (2) knowledge of NAFLD. We estimated that 15 minutes would be needed to complete the survey.

The first section included questions on age, sex, primary specialty, years of practice, time dedicated to patient care, practice location and province of practice, and number of patients with NAFLD managed. The second section included questions regarding awareness of NAFLD in terms of epidemiology, risk factors, methods of diagnosis, and treatment options. A link to the web-based survey was sent by email between February and June 2020 to primary care or internal medicine physicians, gastroenterologists, hepatologists, and hepatology nurses who were members of the College of Family Physicians of Canada, Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver, or Canadian Association of Hepatology Nurses. Confidentiality was preserved by the fact that the emails were sent through the Canadian Liver Foundation. All responses were anonymous, and we received no information that would identify the respondents or their site of practice. No incentive was offered to complete the survey.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was sought from the McGill University Health Centre Research Ethics Office, which determined that official research ethics board approval was not required.

Data analysis

Survey items consisted of multiple-choice questions with a single best answer elicited for some questions (eg, prevalence of NAFLD in the Canadian population, most common cause of death among persons with NAFLD) and more than one choice possible for others (eg, diagnostic tests for liver fibrosis, treatment options in NAFLD). Imposed categories were given for questions such as years of practice (<5 y, 5–10 y, 10–20 y, >20 y) or number of NAFLD patients managed monthly (1–0, 10–30, 30–50, >50). Respondents were able to review and change their answers before submitting their final responses. Standard descriptive statistics were used to describe response frequency. Only respondents who completed the whole survey were included in the analysis. Survey responses were tabulated as frequencies and percentages. For discrete data, cross-tabulations and χ2 test were used. For the purpose of the analysis, the term specialists was used to regroup gastroenterologists, hepatologists, and internal medicine physicians. A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 650 invited physicians, 214 (33%) responded, and 171 (26%) completed the whole survey. Of those who completed the whole survey, 88 (51%) were members of College of Family Physicians of Canada; 51 (30%), of the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver; and 18 (11%), of the Canadian Association of Hepatology Nurses; the rest (8%) were part of other professional organizations. Table 1 provides the demographics of the surveyed physicians and nurses. Overall, 49% of respondents were female, 52% were PCPs, 51% were based in a community practice, and 47% had been in practice for more than 20 years. Specialty practices included gastroenterology and hepatology. The majority of respondents were from Ontario (34%) and Alberta (19%).

Table 1:

Characteristics of the surveyed physicians and nurses (N = 171)

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 77 (45) |

| Female | 83 (49) |

| Prefer not to say | 11 (6) |

| Province of practice | |

| Ontario | 58 (34) |

| Alberta | 33 (19) |

| Quebec | 22 (13) |

| British Columbia | 18 (11) |

| Manitoba | 10 (6) |

| Nova Scotia | 10 (6) |

| Saskatchewan | 9 (5) |

| Rest of Canada | 11 (6) |

| Primary specialty | |

| Family medicine | 88 (51) |

| Gastroenterology | 19 (11) |

| Hepatology | 32 (19) |

| Internal medicine | 14 (8) |

| Nurse | 18 (11) |

| Years of practice | |

| <5 | 28 (16) |

| 5–10 | 32 (19) |

| 10–20 | 30 (18) |

| >20 | 81 (47) |

| Practice location | |

| Hospital | 50 (29) |

| Community practice | 87 (51) |

| Private practice | 34 (20) |

| No. of NAFLD patients managed monthly | |

| 1–10 | 84 (49) |

| 10–30 | 51 (30) |

| 30–50 | 17 (10) |

| >50 | 19 (11) |

NAFLD = Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Knowledge of risk factors, progression, and screening

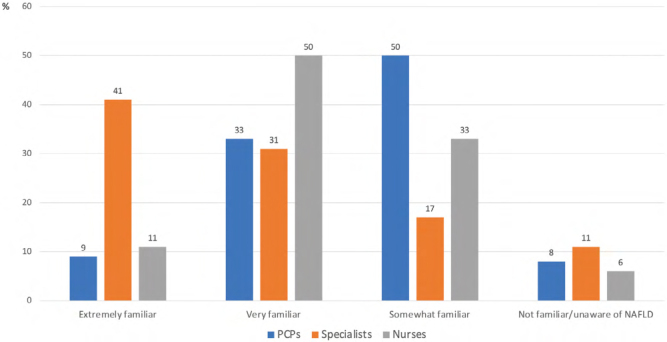

Most specialists (72%) were very familiar or extremely familiar with NAFLD, compared with 42% of PCPs (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1). Similarly, 58% of PCPs were somewhat familiar or unfamiliar with NAFLD compared with 28% of specialists overall and 16% of hepatologists (p < 0.001). The prevalence of NAFLD was correctly reported by 39% of PCPs, compared with 88% of hepatologists. Conversely, 53% of PCPs, 35% of internal medicine specialists, and 35% of nurses thought the prevalence of NAFLD in the general Canadian population was 15% or less. Overall, the reported prevalence was similar among PCPs, gastroenterologists, internal medicine physicians, and nurses, whereas it was significantly different between PCPs and hepatologists (p < 0.001) (Table 2). The respondents who indicated that they were extremely familiar or very familiar with the disease were also more likely to correctly report the prevalence than those with a lower level of familiarity (62% versus 40%; p < 0.001).

Figure 1:

Level of awareness of NAFLD by specialty status

NAFLD = Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PCPs = Primary care physicians

Supplemental Table 1:

Level of awareness of NAFLD, by specialty (N = 171)

| Awareness | Specialty, no. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCPs (n = 88) | Gastroenterology (n = 19) | Hepatology (n = 32) | Internal medicine (n = 14) | Nurses (n = 18) | |

| Extremely familiar | 8 (9) | 6 (32) | 18 (56) | 2 (14) | 2 (11) |

| Very familiar | 29 (33) | 8 (42) | 9 (28) | 4 (29) | 9 (50) |

| Somewhat familiar | 44 (50) | 3 (16) | 4 (13) | 4 (29) | 6 (33) |

| Not familiar/unaware of NAFLD | 7 (8) | 2 (11) | 1 (3) | 4 (28) | 1 (6) |

| p-value* | — | 0.013 | < 0.001 | 0.960 | 0.518 |

Notes: Only one response was allowed

*p-value refers to χ 2 test between PCP column and the other columns

NAFLD = Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PCPs = Primary care physicians

Table 2:

Estimate of the prevalence of NAFLD in the general Canadian population, by specialty (N = 171)

| Prevalence | Specialty, no. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCPs (n = 88) | Gastroenterology (n = 19) | Hepatology (n = 32) | Internal medicine (n = 14) | Nurses (n = 18) | |

| <10% | 21 (24) | 3 (16) | 0 | 3 (21) | 4 (22) |

| 15% | 26 (29) | 3 (16) | 0 | 2 (14) | 2 (11) |

| 25% | 34 (39) | 12 (63) | 28 (88) | 8 (57) | 8 (45) |

| 50% | 7 (8) | 1 (5) | 4 (12) | 1 (7) | 4 (22) |

| p-value* | — | 0.274 | <0.001 | 0.558 | 0.172 |

Notes: Only one response was allowed; the correct answer is in boldface

*p-value refers to χ2 test between PCP column and the other columns

NAFLD = Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PCPs = Primary care physicians

Most of the respondents (90%) considered NASH to be associated with an increased risk of liver disease progression, without differences across specialties. However, only 48% of PCPs, 50% of internal medicine specialists, and 44% of the nurses considered diabetic patients to be at higher risk for NAFLD-associated liver fibrosis, compared with 67% of gastroenterologists and 78% of hepatologists (p = 0.036). When asked about screening for NAFLD, 87% of the respondents indicated that they would initiate screening for NAFLD in patients with type 2 diabetes, with no differences across specialties. Most respondents had knowledge of the classical conditions associated with NAFLD: 80% for dyslipidemia and 86% for obesity. Conversely, they had less knowledge of other associations: 44% for hypertension, 47% for obstructive sleep apnea, 45% for polycystic ovary syndrome, and 31% for hypothyroidism.

With regard to the question about the most common cause of death among NAFLD patients, almost one-third of PCPs and half of nurses thought it was liver cirrhosis, whereas almost all gastroenterologists and hepatologists agreed that it was cardiovascular disease (Table 3). The respondents who declared that they were extremely familiar or very familiar with the disease were also more likely to correctly report the most common cause of death than those with lower levels of familiarity (79% versus 53%; p < 0.001).

Table 3:

Estimate of the most common cause of death among NAFLD patients, by specialty

| Cause of death | Specialty, no. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCPs (n = 88) | Gastroenterology (n = 19) | Hepatology (n = 32) | Internal medicine (n = 14) | Nurses (n = 18) | |

| Liver cirrhosis, HCC | 28 (32) | 2 (11) | 2 (6) | 3 (22) | 9 (50) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 54 (61) | 17 (89) | 30 (94) | 9 (64) | 9 (50) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 6 (7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (14) | 0 |

| p-value* | — | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.722 | 0.149 |

Notes: Only one response was allowed; the correct answer is in boldface

*p-value refers to χ 2 test between PCP column and the other columns

HCC = Hepatocellular carcinoma; PCPs = Primary care physicians

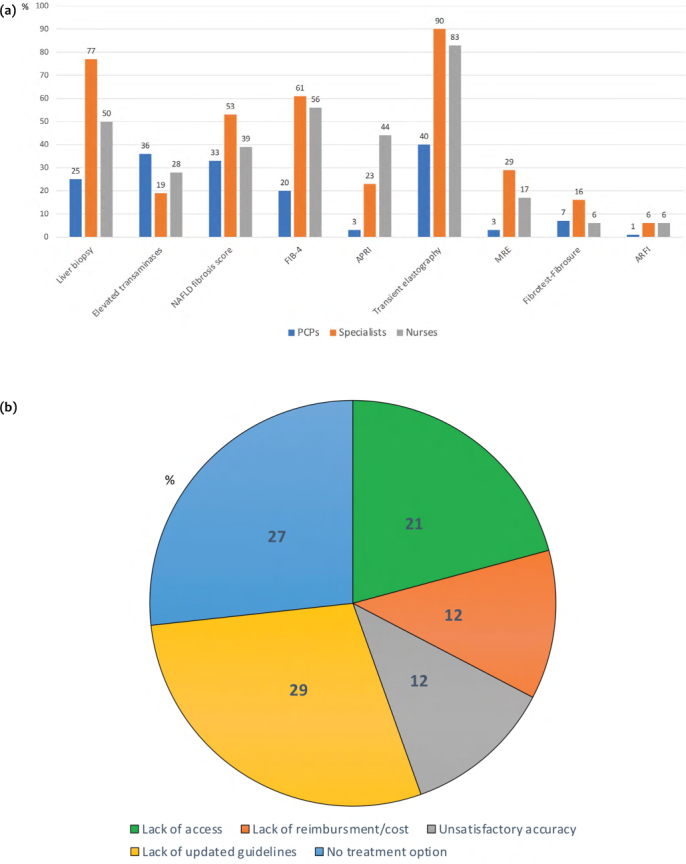

Knowledge about diagnosis

The following methods were used to identify the presence of NASH in patients with NAFLD: liver transaminases (63%), ultrasound (52%), computed tomography scan or MRI (26%), liver biopsy (52%), and transient elastography (64%) (see Supplemental Table 2 for the breakdown by specialty). Only a small proportion of the respondents (13%) considered NASH to always be characterized by elevated liver transaminases, and 42% thought NASH could be diagnosed by imaging or blood tests alone. The gold-standard tool to diagnose NASH, liver biopsy, was selected by 52% of the respondents. With respect to diagnostic tests to stage liver fibrosis in NAFLD, most respondents were using transient elastography, Fibrosis 4 index (FIB-4), and liver biopsy (Figure 2a). All of these tools, including simple serum biomarkers such as FIB-4, were used more often by specialists than by PCPs. Interestingly, the main concerns regarding non-invasive diagnostic methods were lack of updated guidelines, no treatment option for NAFLD, and lack of access to diagnostic tests (Figure 2b).

Supplemental Table 2:

Methods used to identify the presence of NASH in NAFLD patients, by specialty

| Methods | Specialty, no. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCPs (n = 88) | Gastroenterology (n = 19) | Hepatology (n = 32) | Internal medicine (n = 14) | Nurses (n = 18) | |

| Liver transaminases | 64 (73) | 11 (58) | 14 (44) | 7 (50) | 11 (61) |

| Ultrasound | 59 (67) | 7 (37) | 3 (9) | 7 (50) | 12 (67) |

| CT scan/MRI | 29 (33) | 5 (26) | 1 (3) | 4 (29) | 5 (28) |

| Liver biopsy | 35 (40) | 10 (53) | 26 (81) | 5 (36) | 13 (72) |

| Transient elastography | 54 (61) | 10 (53) | 20 (63) | 11 (79) | 15 (83) |

Notes: Multiple responses were allowed

NASH = Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; NAFLD = Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PCPs = Primary care physicians; CT = Computed tomography; MRI = Magnetic resonance imaging

Figure 2:

Diagnostic tests used to stage liver fibrosis in NAFLD by specialty (a) and main concern with non-invasive diagnostic tests for liver fibrosis in NAFLD (b)

NAFLD = Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; FIB-4 = Fibrosis-4 index; APRI = Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; MRE = Magnetic resonance elastography; ARFI = Acoustic radiation force impulse

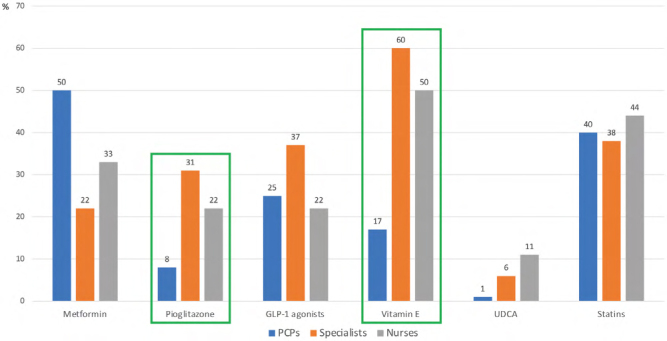

Knowledge about treatment

According to guidelines, at least 10% weight loss is needed to improve the majority of histopathological features of NAFLD, including NASH and liver fibrosis (5). In our survey, 42% of the respondents correctly identified this threshold, whereas the remaining respondents believed lower weight loss would suffice (43% and 15% opted for weight loss targets of 7%–10% and 4%–6%, respectively). As for potential pharmacological treatments, we found significant differences among PCPs, specialists, and nurses (Figure 3). Only 17% and 8% of the PCPs would use vitamin E and pioglitazone, respectively, the treatments currently recommended by guidelines, for patients diagnosed with NASH. A significant proportion of specialists reported that they would consider using pharmacological treatments that are not approved to treat NASH, including metformin (22%) and statins (38%).

Figure 3:

Treatments for NASH by specialty status

NASH = Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; GLP-1= Glucagon-like peptide-1; UDCA = Ursodeoxycholic acid; PCPs = Primary care physicians

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate knowledge and awareness of NAFLD among Canadian physicians and nurses. We found that 58% of PCPs were somewhat familiar or unfamiliar with NAFLD, compared with 28% of specialists and 39% of nurses. Moreover, we found significant differences in knowledge of epidemiology, diagnostic methods, and treatment options among PCPs, specialists, and nurses. Our results suggest the need for a Canadian national strategy for NAFLD, including continuing medical education programs and clinical guidelines.

NAFLD is a global epidemic that affects 25% of the general adult population worldwide (13). Our earlier modelling study demonstrated that, in Canada, the number of NAFLD cases will increase by 20% between 2019 and 2030 (3). The consequences of NAFLD can include NASH, liver cirrhosis, and HCC. Our model shows that the number of NASH and cirrhosis cases will increase by 35% and 95%, respectively, through 2030, totalling 2,630,000 and 195,000 cases, respectively (3). Frequent extra-hepatic associations complicate the clinical picture, including type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease (5). This renders the condition a public health problem requiring urgent attention, awareness, and a national strategy. About 24% and 29% of PCPs thought the prevalence of NAFLD in the general Canadian population was 10% or lower and 15%, respectively, figures that were similar to those reported by internal medicine specialists and nurses. Surveys conducted in other countries have reported low awareness of the disease’s prevalence. Among 100 Australian non-hepatologists, the majority of respondents (75%) believed that the prevalence of NAFLD in the general population was 10% or lower (14). Another survey conducted in the United States among 119 PCPs and internal medicine physicians showed that 84% of PCPs underestimated the prevalence of NAFLD in the general population. A recent survey conducted in Sri Lanka reported that 50% of responding physicians thought the prevalence of NAFLD was lower than 30% (11).

Among our respondents, 90% considered NASH to be associated with an increased risk of liver disease progression. Natural history studies have demonstrated that NASH is associated with a two-fold higher rate of progression to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis compared with simple steatosis (15). However, only half of PCPs, internal medicine specialists, and nurses considered diabetic patients to be at higher risk for liver disease progression. Interestingly, despite this knowledge gap, 87% of the respondents would initiate screening for NAFLD in diabetic patients. Recognizing the impact of type 2 diabetes in the natural history of NAFLD and NASH is crucial for appropriate clinical management. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is the strongest predictor of advanced fibrosis in NAFLD: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2014 reported an odds ratio of 18.2 (95% CI 4.7–70.1) compared with 9.1 (95% CI 2.4–35.0) for obesity and 1.2 (95% CI 0.4–4.2) for hypertension (16). The impact of type 2 diabetes on the natural history of NAFLD is so relevant that recent guidelines recommended, for the first time, screening these patients for NAFLD-associated liver fibrosis (17,18).

Beyond diabetes, most respondents had knowledge of traditional associations with NAFLD: for obesity, 86%, and for dyslipidemia, 80%. Conversely, fewer than 47% of the respondents had knowledge about other associations, including hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, polycystic ovary syndrome, and hypothyroidism. In surveys conducted in the United States and Sri Lanka, the percentages of those with knowledge of an association with hypertension (65%) and polycystic ovary syndrome (61% and 63%, respectively) were higher than our results. This difference may also be due to the different geographical prevalence of some of these conditions (19,20). Conversely, similar low rates of knowledge were reported for obstructive sleep apnea and hypothyroidism. More than one-third of PCPs, internal medicine specialists, and nurses did not recognize cardiovascular disease as the most common cause of death among patients with NAFLD. According to guidelines, cardiovascular complications frequently dictate the outcome of NAFLD, and screening of the cardiovascular system is mandatory for all persons, at least in a detailed risk factor assessment (17).

NASH remains a histologic diagnosis, requiring identification of specific features such as ballooning and lobular inflammation (17). In our survey, 52% of the respondents recognized liver biopsy as the correct diagnostic tool for NASH. However, 42% thought that NASH could be diagnosed by imaging or blood tests. More important, only a small proportion (13%) of those surveyed considered NASH to always be characterized by elevated liver transaminases. This is important because normal liver transaminases have commonly been demonstrated among people with the entire spectrum of NAFLD (21). As for liver fibrosis staging, the most used tests were transient elastography, FIB-4, and liver biopsy. Current guidelines suggest using simple biomarkers or imaging techniques, such as NAFLD fibrosis score, FIB-4, and transient elastography, particularly in combination (5,17). An interesting finding was that the main concerns regarding non-invasive diagnostic methods were lack of updated guidelines, no treatment option for NAFLD, and lack of access. Indeed, provincial differences regarding reimbursement and cost of non-invasive tests, such as transient elastography, or availability of aspartate aminotransferase may lead to reduced implementation (22,23).

Regarding knowledge about treatment of NAFLD, we found significant differences among PCPs, specialists, and nurses. Only 17% and 8% of the PCPs would use vitamin E and pioglitazone, respectively, the treatments currently recommended by guidelines, compared with, respectively, 60% and 31% of the specialists and 50% and 22% of the nurses (5). However, pharmacological treatments not approved to specifically treat NASH, such as metformin, statins, and glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists, were proposed by a significant proportion of PCPs, specialists, and nurses. In the current clinical scenario characterized by few therapeutic options, it is important to be reminded of the treatment interventions that have proved effective in appropriately designed studies, including weight loss (lifestyle modification, bariatric surgery), vitamin E, and pioglitazone (5). Nevertheless, global clinical trials for multiple NASH targets are ongoing, and the future will, we hope, offer more pharmacotherapeutic options.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. The first was the low response rate, which could potentially bias the results, because non-responders might hold divergent views on some aspects of NAFLD or have lower levels of overall interest in it. Second, the limited absolute number of respondents may not reflect the actual number of health care professionals involved in treating patients with NAFLD in Canada. Third, the majority of respondents came from four provinces. The opinions and practices of physicians in the rest of Canada are therefore underrepresented. Nonetheless, we did not observe significant differences in response patterns across provinces (data not shown). Fourth, nurses were underrepresented compared with PCPs and specialists, although this may reflect that only a small proportion of nurses are involved in the care of patients with NASH.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this survey shows that more than half of PCPs, one-quarter of specialists, and one-third of nurses consider themselves to be only somewhat familiar or unfamiliar with NAFLD. We have proposed that potential knowledge gaps exist among PCPs regarding epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of this epidemic condition in Canada. We advocate for a better understanding of and a national plan for the diagnosis and management of NAFLD. We believe, as does the Canadian NASH Network, that this strategy should be based on the development of national NAFLD guidelines and of a dedicated continuing medical education program. We are currently working to develop a policy strategy for NAFLD prevention, including training courses for health care professionals, an awareness campaign for affected communities, and a uniform model of care.

Supplementary Information

Funding Statement

The study was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Intercept. GS is supported by a Junior 1 and 2 Salary Award from Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Quebéc (Nos. 27127 and 267806).

Ethics Approval:

N/A

Informed Consent:

N/A

Registry and Registration No. of the Study/Trial:

N/A

Funding:

The study was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Intercept. GS is supported by a Junior 1 and 2 Salary Award from Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Quebéc (Nos. 27127 and 267806).

Disclosures:

GS has acted as speaker for Merck, Gilead, AbbVie, Novonordisk, Novartis, and Pfizer; served as an advisory board member for Pfizer, Merck, Novartis, Gilead, Allergan, and Intercept; and received unrestricted research funding from Merck and Theratec. AR served on advisory boards and speakers bureaus for Gilead, Intercept, AbbVie, Celgene, Merck, and Novartis and received clinical trial funding from AbbVie, Assembly, Gilead, Intercept, Galmed, Janssen, Springbanks, Allergan, and Novartis. MGS served on advisory boards and speakers bureaus for Gilead, Intercept, Abbott, and Novartis and received clinical trial funding from Gilead, Intercept, CymaBay, Genkyotex, GSK, and Novartis. KP is a speaker for Gilead Sciences, Intercept, and Abbott; is advisory board/consultant for Gilead Sciences, Intercept, Novartis, and Allergan; and received research funding from Gilead Sciences.

Peer Review:

This article has been peer reviewed.

Data Sharing:

According to legal restrictions imposed by Canadian law regarding clinical research and trials, anonymized data are available on request. Please send data access requests to Canadian NASH Network, Alnoor Ramji, Division of Gastroenterology, University of British Columbia, 770–1190 Hornby Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V6Z 2K5, Canada.

References

- 1.Sebastiani G, Ghali P, Deschenes M, Wong P. Noninvasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis: the importance of being reimbursed. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29(4):219–220. 10.1155/2015/943410. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanabria AJ, Dion R, Lucar E, Soto JC. Evolution of the determinants of chronic liver disease in Quebec. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2013;33(3):137–45. 10.24095/hpcdp.33.3.04. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swain MG, Ramji A, Patel K, et al. Burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Canada, 2019-2030: a modelling study. CMAJ Open. 2020;8(2):E429–E436. 10.9778/cmajo.20190212. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratziu V, Bellentani S, Cortez-Pinto H, Day C, Marchesini G. A position statement on NAFLD/NASH based on the EASL 2009 special conference. J Hepatol. 2010;53(2):372–84. 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.008. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328–57. 10.1002/hep.29367. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlton MR, Burns JM, Pedersen RA, Watt KD, Heimbach JK, Dierkhising RA. Frequency and outcomes of liver transplantation for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(4):1249–53. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.061. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the U.S. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):547–55 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.039. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. 10.3322/caac.20107. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016-2030. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):P896–P904. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.036. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazarus JV, Ekstedt M, Marchesini G, et al. A cross-sectional study of the public health response to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Europe. J Hepatol. 2020;72(1):P14–P24. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.08.027. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthias AT, Fernandopulle ANR, Seneviratne SL. Survey on knowledge of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) among doctors in Sri Lanka: a multicenter study. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:556. 10.1186/s13104-018-3673-2. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Said A, Gagovic V, Malecki K, Givens ML, Nieto FJ. Primary care practitioners survey of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12(5):758–65. 10.1016/S1665-2681(19)31317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73–84. 10.1002/hep.28431. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergqvist CJ, Skoien R, Horsfall L, Clouston AD, Jonsson JR, Powell EE. Awareness and opinions of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by hospital specialists. Intern Med J. 2013;43(3):247–53. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02848.x. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Loomba R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(4):643–54.E9. 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.014. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong RJ, Liu B, Bhuket T. Significant burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis in the US: a cross-sectional analysis of 2011-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(10):974–80. 10.1111/apt.14327. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Association for the Study of the Liver, European Association for the Study of Diabetes, European Association for the Study of Obesity. EASL-EASD-EASO clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016; 64(6):1388–402. 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Introduction: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care 2019;42 (Supplement 1):S1–S2. 10.2337/dc19-Sint01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mills KT, Stefanescu A, He J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:223–37. 10.1038/s41581-019-0244-2. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf WM, Wattick RA, Kinkade ON, Olfert MD. Geographical prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome as determined by region and race/ethnicity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2589. 10.3390/ijerph15112589. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunde SS, Lazenby AJ, Clements RH, Abrams GA. Spectrum of NAFLD and diagnostic implications of the proposed new normal range for serum ALT in obese women. Hepatology. 2005;42(3):650–56. 10.1002/hep.20818. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sebastiani G, Ghali P, Wong P, Klein MB, Deschenes M, Myers RP. Physicians' practices for diagnosing liver fibrosis in chronic liver diseases: a nationwide, Canadian survey. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28: 23–30. 10.1155/2014/675409. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kan VY, Marquez Azalgara V, Ford JA, Kwan WCP, Erb SR, Yoshida EM. Patient preference and willingness to pay for transient elastography versus liver biopsy: a perspective from British Columbia. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29:72–76. 10.1155/2015/169190. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.