Abstract

The gene encoding an α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Thermobacillus xylanilyticus D3, AbfD3, was isolated. Characterization of the purified recombinant α-l-arabinofuranosidase produced in Escherichia coli revealed that it is highly stable with respect to both temperature (up to 90°C) and pH (stable in the pH range 4 to 12). On the basis of amino acid sequence similarities, this 56,071-Da enzyme could be assigned to family 51 of the glycosyl hydrolase classification system. However, substrate specificity analysis revealed that AbfD3, unlike the majority of F51 members, displays high activity in the presence of polysaccharides.

Microorganisms employ a wide variety of enzymes to degrade hemicellulosic material. Backbone-degrading endoxylanases and β-xylosidases are the principal enzymes, but numerous side chain-cleaving enzymes, such as α-l-arabinofuranosidases (8, 12, 33), α-glucuronidases, acetylxylan esterases, and phenolic acid esterases, are also important. One substituent of xylan, l-arabinose, is present in significant amounts in wheat bran and straw in the form of arabinoxylans. Hydrolysis of such important agricultural by-products using a endo-β(1,4)-xylanase has identified substituting l-arabinose as a potential barrier for xylanase action (20), and indeed, a synergistic effect between the activities of an α-l-arabinofuranosidase and a xylanase has been previously reported (1). Despite the obvious potential role for α-l-arabinofuranosidases in the industrial bioconversion of plant material, most of the known enzymes would be unsuitable. Indeed, in addition to their lack of robustness (thermostability and pH tolerance), most α-l-arabinofuranosidases exhibit a narrow substrate specificity range (2, 10), which limits their action towards either oligomeric substrates (13, 16, 19, 21) or polymeric substrates (11, 12). Our work on a novel thermophilic bacterium, Thermobacillus xylanilyticus, has led to the identification of several hemicellulase-encoding genes (3, 4, 7), including one for an α-l-arabinofuranosidase, the products of which may be suitable as biological catalysts for industrial processes (24, 25).

Isolation and characterization of the α-l-arabinofuranosidase-encoding gene, abfD3.

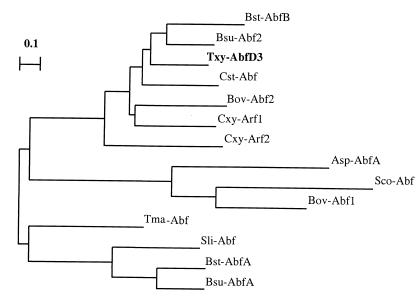

Genetic analysis of ∼9-kb genomic DNA segment revealed the presence of three open reading frames in the same strand (EMBL database accession number Y16849). Of these, one (1,488 bp) encodes a 56-kDa (496-amino-acid) protein which was identified by a database enquiry as a putative family 51 α-l-arabinofuranosidase. Comparison of the sequence of this protein, AbfD3, with members of family 51 (F-51) of the glycosyl hydrolase classification system (9) and the creation of a phylogenetic tree revealed that this enzyme is localized within a distinct phylogenetic cluster which contains three other α-l-arabinofuranosidases from taxonomically related bacterial sources (Bacillus subtilis [14], Clostridium stercorarium [28], and Bacillus stearothermophilus [6]) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree (dendrogram) showing the evolutionary relationships between F-51 α-l-arabinofuranosidases. The tree was generated from an alignment which was performed using the CLUSTAL V option of the MegAlign module of the DNAstar package. Asp-AbfA, Abf A from Aspergillus niger (5); Bov-Abf1 and Bov-Abf2, Abf 1 and 2 from Bacteroides ovatus (EMBL accession no. Q59218 and Q59219), respectively; Bst-AbfB, partial α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Bacillus stearothermophilus (GenBank accession no. AF159625); Bst-AbfA, Abf A from B. stearothermophilus (6); Bsu-AbfA and Bsu-Abf2, Abf A and Abf 2 from Bacillus subtilis (27), respectively; Cst-Abf, Abf B from Clostridium stercorarium (28); Cxy-Arf1 and Cxy-Arf2, α-l-arabinofuranosidase 1 and 2 from Cytophaga xylanolytica (15), respectively; Sco-Abf, the putative secreted arabinosidase from Streptomyces coelicolor (23); Sli-Abf, Abf A from Streptomyces lividans (22); Tma-Abf, Abf from Thermotoga maritima (GenBank accession no. AE 000512); Txy-AbfD3, Abf D3 from Thermobacillus xylanilyticus D3 (EMBL accession no. Y16849).

Expression and purification of recombinant AbfD3.

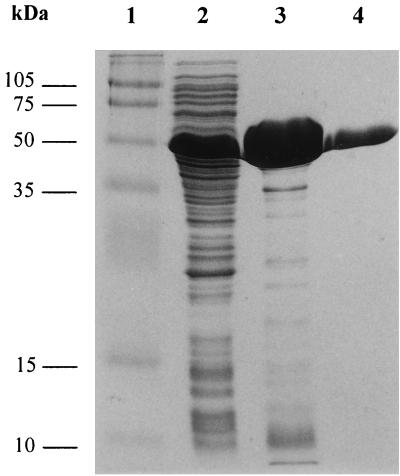

The insertion of the abfD3 reading frame into the pET24 E. coli expression vector (29) allowed the production of large amounts of recombinant AbfD3. Preliminary analysis of this protein using sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2) and N-terminal sequence analysis confirmed that AbfD3 was produced as a single species which exhibits an apparent molecular weight of 56,000 and the N-terminal sequence MNVAS. These data are consistent with those predicted for the protein encoded by abfD3. After host cell lysis, recombinant AbfD3 was purified by an initial heat treatment step (75°C, 30 min) followed by hydrophobic interaction chromatography. After this simple but efficient purification procedure (75.9% yield), the AbfD3 was highly pure.

FIG. 2.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of recombinant AbfD3. Lane 1, protein molecular mass standards; lanes 2 to 4, E. coli extract after sonication (lane 2) heat precipitation (lane 3), and passage through Phenyl-Sepharose column (lane 4). The numbers to the left indicate the molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of the standards. Proteins are stained with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Characterization of AbfD3.

Mass spectral analysis of purified AbfD3 revealed a mass of 56,094 ± 28 Da, which is in agreement with the theoretical value of 56,071 Da. Kinetic studies using AbfD3 in the presence of para-nitrophenyl-α-l-arabinose as the substrate allowed the determination of Michaelis-Menten parameters (Table 1). These results indicate that AbfD3 is highly active and exhibits an optimum temperature for activity which is superior to that of any other α-l-arabinofuranosidase so far reported (6, 28). In addition, the stability of AbfD3 with respect to temperature and pH were measured. Temperature stability measurements, performed by measuring residual activity after various incubation periods at three different temperatures (pH 8.0), revealed that AbfD3 conserved 50% of its maximum activity after a 2-h incubation period at 90°C. In addition, while the optimum activity of AbfD3 was observed at 75°C and in the pH range 5.6 to 6.2, the enzyme remained active after prolonged incubation periods in the pH range 4 to 11. The effects of different metal ions and other additives on AbfD3 activity were also evaluated. The addition of EDTA (2 mM) or divalent cations, such as Ca2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, and Ni2+, did not modify activity, suggesting that AbfD3 does not require metal cofactors. Cu2+ and Co2+ (2 mM) partially inhibited enzyme activity, while HgCl2 treatment induced a 72% inhibition of AbfD3 activity. AbfD3 was unaffected by dithiothreitol up to 0.5 M or β-mercaptoethanol, suggesting the absence of disulfide links. Guanidine-HCl (10 mM) had no effect on the activity. At low concentrations, the ionic detergent SDS activated the enzyme (1 to 2 mM), while at higher concentrations, it had a detrimental effect (up to 20 mM). The nonionic detergent Triton X-100 (0.02 to 0.1%) had a mild stimulatory effect.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters of AbfD3 measured at two different temperatures using para-nitrophenyl-α-l-arabinose as the substrate

| Temp (°C) | Km (mM) | Vmax (μmol of pNPa min−1 mg−1) | Sp act (IU/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 0.72 | 456 | 350 |

| 75 | 0.5 | 555 | 490 |

pNP, para-nitrophenol.

Substrate specificity.

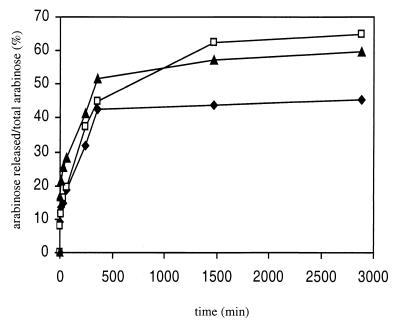

AbfD3 did not hydrolyze para-nitrophenyl-α-l-arabinopyranoside or gum arabic, indicating that AbfD3 is specifically active towards the furanosidic conformation and α linkages. AbfD3 was found to be extremely active on wheat arabinoxylan, larchwood xylan, and oat spelt xylan (Fig. 3). This finding is rather surprising, since as a member of F51, AbfD3 would be expected to present a low activity towards arabinoxylans. The rate of arabinose liberation was highest for wheat arabinoxylan (30 μg of arabinose liberated per ml after 30 min compared to 12.94 and 6.75 μg of larchwood and oat spelt xylan per ml, respectively). In contrast, the total amount of arabinose liberated from wheat arabinoxylan (45%) was lower than that for larchwood xylan (57%) or for oat spelt xylan (64%). The higher initial reaction rate of AbfD3 with wheat arabinoxylan is almost certainly due to the higher degree of arabino-substitution in this substrate compared to the two others. However, an explanation for the difference in the initial reaction rates for larchwood xylan and oat spelt xylan, in which there is a similar degree of arabino-monosubstitution and - disubstitution, might be the linkage preference of AbfD3. Indeed, in larchwood xylan, arabinose is mainly O-2 linked to xylose, whereas in oat spelt xylan, it is O-3 linked (17). Interestingly, the yield of arabinose from wheat arabinoxylan hydrolysis could not be improved by increasing enzyme concentrations, indicating that the remaining arabinose was not available to hydrolysis. Several reasons might explain this phenomenon. Linkage preference (see above) may intervene (17, 31, 32), although our results with larchwood and oat spelt xylan suggest that AbfD3 possesses an ability, albeit biased, to hydrolyze both O-2 and O-3 linkages. Alternatively, arabino-disubstituted xylose may constitute a limiting factor, especially since this type of residue is well represented in xylans from the family Graminaceae. This hypothesis seems likely because limitation of arabinosidase action by arabino-disubstituted xylose in wheat xylan has been reported previously (18), and only one enzyme known to be able to release arabinosyl residues from disubstituted xylose has been isolated to date (31). Finally, it is important to note that the progressive loss of arabinose substituents increases the insolubility of the substrate, which may also contribute to a decreased hydrolysis rate (19).

FIG. 3.

Time course study of arabinose liberation from different arabinoxylans by AbfD3 at the first stage of hydrolysis. A 0.1% (wt/vol) solution of polysaccharide (larchwood xylan [▴], oat spelt xylan [□], and wheat flour arabinoxylan [⧫]) was incubated at 60°C with 10 IU of AbfD3 per ml (28 μg/ml). The amount of arabinose released is expressed as a percentage of the total amount of arabinose linked to the xylan backbone.

Concluding remarks.

AbfD3 is a highly stable, highly active α-l-arabinofuranosidase which, based upon sequence similarities, would appear to belong to F51 of the glycosyl hydrolase classification system. The high activity of this enzyme towards arabinoxylans suggests that this enzyme may prove to be a useful accessory enzyme for the bioconversion of economically important agricultural resources. However, our results also underline the fact that a detailed understanding of the structures of complex hemicellulosic material should constitute a prerequisite to the efficient use of any hemicellulases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Europol'agro consortium.

We thank Christelle Breton for the preliminary sequencing work which led to the isolation of the abfD3 gene.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachmann S L, McCarthy A J. Purification and cooperative activity of enzymes constituting the xylan-degrading system of Thermomonospora fusca. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2121–2130. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.8.2121-2130.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beldman G, Schols H A, Pitson S M, Searl-van Leeuwen M J F, Voragen A G J. Arabinans and arabinan degrading enzymes. Adv Macromol Carbohydr Res. 1997;1:1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connerton I, Cummings N, Harris G W, Debeire P, Breton C. A single domain thermophilic xylanase can bind insoluble xylan: evidence for surface aromatic clusters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1433:110–121. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debeire-Gosselin M, Loonis M, Samain E, Debeire P. Purification and properties of a 22kDa endoxylanase excreted by a new strain of thermophilic bacterium. In: Visser J, Beldman G, Kusters-van Someren M A, Voragen A G J, editors. Xylans and xylanases. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.; 1992. pp. 463–466. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flipphi M J A, Visser J, Van der Veen P, De Graaff L H. Arabinase gene expression in Aspergillus niger: indications for coordinated regulation. Microbiology. 1994;140:2673–2682. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-10-2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilead S, Shoham Y. Purification and characterization of α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Bacillus stearothermophilus T-6. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:170–174. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.170-174.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris G W, Pickersgill R W, Connerton I, Debeire P, Touzel J P, Breton C, Perez S. Structural basis of the properties of an industrially relevant thermophilic xylanase. Proteins. 1997;1:77–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hata K, Tanaka M, Tsumuraya Y, Hashimoto Y. α-l-Arabinofuranosidase from radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seeds. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:388–396. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.1.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henrissat B, Bairoch A. Updating the sequence-based classification of glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem J. 1996;316:695–696. doi: 10.1042/bj3160695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaji A. L-arabinosidases. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem. 1984;42:382–394. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaji A, Tagawa K. Purification, crystallisation, and amino acid composition of α-L-arabinofuranosidase from Aspergillus niger. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;207:456–464. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2795(70)80008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaji A, Tagawa K, Ichimi T. Properties of purified α-L-arabinofuranosidase from Aspergillus niger. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;171:186–188. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaneko S, Arimoto M, Ohba M, Kobayashi H, Ishii T, Kusakabe I. Purification and substrate specificities of two α-l-arabinofuranosidases from Aspergillus awamori IFO 4033. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4021–4027. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.4021-4027.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaneko S, Sano M, Kusakabe I. Purification and some properties of α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Bacillus subtilis 3-6. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3425–3428. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3425-3428.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim K S, Lilburn T G, Renner M J, Breznak J A. arfI and arfII, two genes encoding α-l-arabinofuranosidase in Cytophaga xylanolytica. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1919–1923. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1919-1923.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komae K, Kaji A, Sato M. An α-L-arabinofuranosidase from Streptomyces purpurascens IFO 3389. Agric Biol Chem. 1982;46:1899–1905. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kormelink F J M, Voragen A G J. Degradation of different [(glucurono)arabino]xylans by a combination of purified xylan-degrading enzymes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;38:688–695. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kormelink F J M, Gruppen H, Voragen A G J. Mode of action of (1,4)-β-D-arabinoxylan arabinofuranohydrolase (AXH) and α-L-arabinofuranosidases on alkali-extractable wheat flour arabinoxylan. Carbohydr Res. 1993;249:345–353. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(93)84099-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kormelink F J M, Searle-Van Leewen M J F, Wood T M, Voragen A G J. Purification and characterization of a (1,4)-β-D-arabinoxylan arabinofuranohydrolase from Aspergillus awamori. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;35:753–758. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lequart C, Nuzillard J M, Kurek B, Debeire P. Hydrolysis of wheat bran and straw by an endoxylanase: production and structural characterisation of cinnamoyl-oligosaccharides. Carbohydr Res. 1999;319:102–111. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(99)00110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luonteri E, Beldman G, Tenkanen M. Substrate specificities of Aspergillus terreus α-arabinofuranosidases. Carbohydr Polym. 1998;37:131–141. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manin C, Shareek F, Morosoli R, Kluepfel D. Purification and characterisation of an α-L-arabinofuranosidase from Streptomyces lividans sequence of the gene abfA. Biochem J. 1994;302:443–449. doi: 10.1042/bj3020443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Redenbach M, Kieser H M, Denapaite D, Eichner A, Cullum J, Kinashi H, Hopwood D A. A set of ordered cosmids and a detailed genetic and physical map for the 8 Mb Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:77–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6191336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rouau X. Investigations into the effects of an enzyme preparation for baking on wheat flour dough pentosans. J Cereal Sci. 1993;37:337–340. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saha B C, Bothast R J. Effect of carbon source on production of α-L-arabinofuranosidase by Aureobasidium pullulans. Curr Microbiol. 1998;37:337–340. doi: 10.1007/s002849900388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samain E, Touzel J P, Brodel B, Debeire P. Isolation of a thermophilic bacterium producing high levels of xylanase. In: Visser J, Beldman G, Kusters-van Someren M A, Voragen A G J, editors. Xylans and xylanases. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.; 1992. pp. 467–470. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sa-Nogueira I, Nogueira T V, Soares S, De Lencastre H. The Bacillus subtilis L-arabinose (ara) operon: nucleotide sequence, genetic organization and expression. Microbiology. 1997;143:957–969. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz W H, Bronnenmeir K, Krause B, Lottspeich F, Staudenbauer W L. Debranching of arabinoxylan: properties of the thermoactive recombinant α-L-arabinofuranosidase from Clostridium stercorarium (ArfB) Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;43:856–860. doi: 10.1007/BF02431919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Studier F W. Use of bacteriophage T7 lysozyme to improve an inducible T7 expression system. J Mol Biol. 1991;219:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90855-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Touzel J P, O'Donohue M, Debeire P, Samain E, Breton C. Thermobacillus xylanilyticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a new aerobic thermophilic xylan-degrading bacterium isolated from farm soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:315–320. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-1-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Laere K M J, Beldman G, Voragen A G J. A new arabinofuranohydrolase from Bifidobacterium adolescentis able to remove arabinosyl residues from double-substituted xylose units in arabinoxylan. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;47:231–235. doi: 10.1007/s002530050918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Laere K M J, Voragen C H L, Kroef T, Van den Broek L A M, Beldman G, Voragen A G J. Purification and mode of action of two arabinoxylan arabinofuranohydrolases from Bifidobacterium adolescentis DSM 20083. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;51:606–613. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinstein L, Albersheim P. Structure of plant cell walls. IX. Purification and partial characterisation of a wall degrading endo-arabanase and an arabinosidase from Bacillus subtilis. Plant Physiol. 1979;63:425–432. doi: 10.1104/pp.63.3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]