Abstract

Background:

HDL (high-density lipoprotein) and its major protein component, apoA-I (apolipoprotein A-I), play a unique role in cholesterol homeostasis and immunity. ApoA-I deficiency in hyperlipidemic, atheroprone mice was shown to drive cholesterol accumulation and inflammatory cell activation/proliferation. The present study was aimed at investigating the impact of apoA-I deficiency on lipid deposition and local/systemic inflammation in normolipidemic conditions.

Methods:

ApoE deficient mice, apoE/apoA-I double deficient (DKO) mice, DKO mice overexpressing human apoA-I, and C57Bl/6J control mice were fed normal laboratory diet until 30 weeks of age. Plasma lipids were quantified, atherosclerosis development at the aortic sinus and coronary arteries was measured, skin ultrastructure was evaluated by electron microscopy. Blood and lymphoid organs were characterized through histological, immunocytofluorimetric, and whole transcriptome analyses.

Results:

DKO were characterized by almost complete HDL deficiency and by plasma total cholesterol levels comparable to control mice. Only DKO showed xanthoma formation and severe inflammation in the skin-draining lymph nodes, whose transcriptome analysis revealed a dramatic impairment in energy metabolism and fatty acid oxidation pathways. An increased presence of CD4+ T effector memory cells was detected in blood, spleen, and skin-draining lymph nodes of DKO. A worsening of atherosclerosis at the aortic sinus and coronary arteries was also observed in DKO versus apoE deficient. Human apoA-I overexpression in the DKO background was able to rescue the skin phenotype and halt atherosclerosis development.

Conclusions:

HDL deficiency, in the absence of hyperlipidemia, is associated with severe alterations of skin morphology, aortic and coronary atherosclerosis, local and systemic inflammation.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, hyperlipidemias, inflammation, lymph nodes, xanthomatosis

HIGHLIGHTS.

ApoA-I (apolipoprotein A-I)/apoE knockout mice are normocholesterolemic and HDL (high-density lipoprotein) deficient.

Skin xanthomas and severe atherosclerosis are the phenotypic features of apoA-I/apoE knockout mice.

ApoA-I/apoE deletion causes severe inflammation in the skin-draining lymph nodes.

RNA-seq of lymph nodes shows alterations in lipid metabolism and fatty acid oxidation pathways.

Overexpression of human apoA-I is able to rescue the apoA-I/apoE knockout phenotype.

See cover image

The pivotal role of HDL (high-density lipoprotein) in regulating cell cholesterol homeostasis is very well recognized. HDL and its main protein component, apoA-I (apolipoprotein A-I), are essential in mediating the removal of excess cholesterol from all the cells of our body.1 This ability has been considered as the main explanation for the inverse correlation between HDL-C (HDL-cholesterol) plasma levels and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease resulting from prospective observational studies.2 In addition, severe HDL deficiency, especially when genetically determined, is frequently associated in the clinic with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.3

While Mendelian randomization studies failed to establish a clear causal role between HDL-C and myocardial infarction or coronary heart disease,4,5 they supported a causal role for HDL in immune regulation.6 More recently, a thorough analysis of the relationship between HDL-C levels and all-cause mortality highlighted a U-shaped association between HDL-C levels and increased mortality risk and also autoimmune diseases for both extremes—very low and very high levels of HDL-C7,8—thus proposing a key role for HDL in infection and sepsis.9

A direct link between low HDL-C levels and immune disorders has been experimentally established. Several animal studies have demonstrated that, beyond the effect on cholesterol efflux,10 HDL possesses a plethora of additional anti-inflammatory,11 antioxidant,12 and antithrombotic properties.13 In particular, HDL is able to influence the cellular activities involved in the innate and adaptive immune response through the fine regulation of the cellular cholesterol content.14 Under reduced plasma HDL levels, peripheral blood mononuclear cells become enriched in cholesterol and display signs of cholesterol imbalance,15 resulting in monocyte adhesion to the endothelium and recruitment in peripheral tissues, including the arterial wall.16 Additionally, it has been demonstrated that the transgenic expression of human apoA-I inhibits foam cell formation in apoE deficient (EKO) mice by promoting macrophage cholesterol efflux via the ABCA1 (ATP-binding cassette transporter A1) and ABCG1 (ATP-binding cassette transporter G1).17

In a mouse model of hyperlipidemia combined to apoA-I deficiency—LDLrKO (low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout)/apoA-IKO mice fed an atherogenic diet for 12 weeks—an expansion and activation of T cells in the skin-draining lymph nodes was observed, and T and B lymphocytes showed an increased cholesteryl ester content compared with LDLrKO mice.18,19 Interestingly, LDLrKO/apoA-IKO mice also showed skin abnormalities, which included dermal cholesterol accumulation.20 It has never been investigated if these alterations may occur when apoA-I deficiency is not associated to a hyperlipidemic condition.

In the present study, the impact of different levels of apoA-I/HDL-C on lipid accumulation in the skin, local, and systemic immunoinflammatory activation, as well as atherosclerosis progression at the aortic sinus and coronary arteries, was evaluated in genetically modified mice fed a normal laboratory diet. Specifically, the following mouse lines were investigated: wild-type (WT) mice as control, apoE and apoA-I double knockout mice with negligible HDL-C levels (apoE/apoA-I double deficient [DKO]); DKO knockout mice expressing human apoA-I (DKO/hA-I), with elevated apoA-I and HDL-C levels; apoE knockout mice (EKO), which display halved apoA-I levels and low HDL-C levels21 compared with WT mice.

The results indicate that HDL deficiency in DKO mice, in the presence of plasma total cholesterol comparable to that of WT mice, is associated with xanthoma formation, accelerated atherosclerosis, both at the aortic sinus and coronary arteries, and increased local and systemic inflammation.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Mice

Procedures involving animals and their care were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines in compliance with national (D.L. No. 26, March 4, 2014, G.U. No. 61 March 14, 2014) and international laws and policies (EEC Council Directive 2010/63, September 22, 2010: Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, United States National Research Council, 2011). The experimental protocol was approved by the Italian Ministry of Health (Protocollo 2012/4).

C57Bl/6J (WT) and apoE knockout (EKO) male mice (strain 002052) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Calco, Italy). ApoE/apoA-I double knockout male mice (DKO) were previously generated in our lab.22 DKO/hA-I were obtained by multiple crosses between DKO mice and hemizygous mice overexpressing human apoA-I.23 The human apoA-I transgene in this model is almost exclusively expressed in the liver, and—at very low amounts—in testis.24 Only male mice were enrolled in the study, to prevent the possible impact of hormonal changes of female mice on the results.

Primers specific for murine apoE (For 5′-GCCTAGCCGAGGGAGAGCCG-3′; Rev1 5′-TGTGACTTGGGAGCTCTGCAGC-3′; Rev2 5-GCCGCCCCGACTGCATCT-3′), murine apoA-I (For 5′-CCTTCTATCGCCTTCTTGACG-3′; Rev1 5′-GTTCATCTTGCTGCCATACG-3′; Rev2 5′-TCTGGTCTTCCTGACAGGTAGG-3′), and human apoA-I (For 5′-GATCGAGTGAAGGACCTGGC-3′; Rev 5′-CCTCCTGCCACTTCTTCTGG-3′) were used to screen genotypes.

Mice were maintained under standard laboratory conditions (12-hour light cycle, temperature 22 °C, humidity 55%), with free access to normal laboratory diet (4RF21, Mucedola, Settimo Milanese, Italy) and tap water from weaning to 30 weeks of age.

Plasma Lipids

After an overnight fast, mice were anaesthetized with 2% isoflurane (Merial Animal Health, Woking, United Kingdom). Blood was collected from the retroorbital plexus into tubes containing 0.1% EDTA (ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid; w/v) and centrifuged in a microcentrifuge for 10 minutes at 5900×g at 4 °C. Plasma total cholesterol was measured with an enzymatic method (CPA11 A01634, ABX Diagnostics, Montpellier, France). Cholesterol distribution among lipoproteins was analyzed by fast protein liquid chromatography as described.23

HDL-C was measured after precipitation of apoB-containing lipoproteins with polyethylene glycol (20%, w/v) in 0.2 mol/L glycine (pH 10).25 Plasma non-HDL-C was measured as the difference between total cholesterol and HDL-C. Plasma human apoA-I concentration was determined by immunoturbidimetric assays, using an antiserum specific for human apoA-I (LTA, Milan, Italy), as previously described.26 Coomassie staining was used to quantify plasma murine apoA-I and to confirm the immunoturbidimetric quantification of human apoA-I.27 Purified apoA-I was used as calibration standard.

Detection of Circulating Cytokines/Chemokines

By using a customized detection MILLIPLEX MAP Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine panel (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA), the following 13 cytokines/chemokines were evaluated in plasma-EDTA samples: eotaxin, G-CSF (granulocyte-colony stimulating factor), IL (interleukin)-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12(p70), IL-15, IL-17, IP-10 (interferon gamma-induced protein 10), KC/CXCL1 (keratinocyte-derived cytokine), LIX/CXCL5 (lipopolysaccharide-inducible CXC chemokine), and MIG/CXCL9 (monokine induced by gamma interferon). These analyses were outsourced to certified laboratories (Department of Experimental Evolutionary Biology, University of Bologna and Labospace Srl).

Tissue Harvesting

Mice were euthanized at 30 weeks of age under general anesthesia with 2% isoflurane and blood was removed by perfusion with 1× PBS. For histological analyses, hearts were harvested, fixed in 10% formalin for 24 hours, then transferred into 1× PBS containing 30% sucrose (w/v) for 24 hours at 4 °C before being embedded in OCT (optimal cutting temperature) compound (Sakura Finetek Europe B.V., Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands) and stored at −80 °C.

From a first set of mice, half of the spleen and the right axillary lymph node were harvested and immediately processed for flow cytometry analysis; the other half of the spleen and the left axillary lymph node were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent RNA-seq and molecular analyses. From a second set of mice, half of the spleen and the right axillary lymph node were immersion-fixed in 10% formalin for 24 hours, dehydrated in a graded scale of ethanol, and paraffin embedded. The other half of the spleen and the contralateral axillary lymph node were immersion-fixed in 10% formalin for 24 hours, then transferred into 1× PBS containing 30% sucrose (w/v) for 24 hours at 4 °C and embedded in OCT compound. Skin biopsies, excised from the thoracic region, were dissected in 2×2 mm fragments and processed for transmission electron microscopy analysis as previously described.22 Additional skin biopsies were excised from the thoracic region, dissected in 5×5 mm fragments, immersion-fixed in 10% formalin for 24 hours, then transferred into 1× PBS containing 30% sucrose (w/v) for 24 hours at 4 °C and embedded in OCT compound.

Histology

Heart

To determine the presence and length of atherosclerotic plaques in coronary arteries, serial transverse cryosections (7 μm thick) of the entire heart from the apex to the ostia of the coronary arteries at the aortic root were cut. Lipid deposition in the coronary arteries was determined through Oil Red O (ORO; Sigma-Aldrich, MO) staining of all slides. To obtain reliable data, the number of coronary lesions has been determined only in coronary arteries with an orthogonal course with respect to the orientation of the sections. Plaque length was determined by summing the sequential sections in which the presence of the ORO signal within arteries was observed, taking into account the thickness of each section. Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections were used to detect atherosclerotic plaque area at the aortic sinus, as previously described.28 Both coronary arteries and aortic sinus histology were performed in accordance with American Heart Association recommendations.29 Macrophages and T lymphocytes were detected using an anti-Mac2 antibody (CL8942, Cedarlane, Ontario, Canada; RRID:AB_10060258) and an anti-CD3 antibody (MAB4841, R&D Systems, MN; RRID:AB_358426), respectively. Detection was performed using an ImmPRESS reagent kit (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, United Kingdom). Diaminobenzidine was used as the chromogen (ImmPACT DAB Substrate, Peroxidase HRP SK-4105, Vector Laboratories), and the sections were counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin (Bio-Optica, Milan, Italy).

Axillary Lymph Node, Spleen, and Skin

Serial sections (5 μm thick) of the axillary lymph node were obtained and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. In addition, in the axillary lymph node, macrophages, B and T lymphocytes were detected using an anti-Iba-1 (019-19741, WAKO, United States; RRID AB_839504), an anti-CD45R/B220 (BD Pharmingen, United States; RRID AB_396673) and an anti-CD3 epsilon (Sc-1127, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States; RRID AB_631128), respectively. Cryosections (7 μm thick) from OCT embedded organs were stained with ORO to detect neutral lipid accumulation. Lipid deposition was measured as the percent of ORO positive area over the total area.30

The Aperio ScanScope GL Slide Scanner (Aperio Technologies, CA) was used to acquire digital images that were subsequently processed with the ImageScope software. Two operators blinded to mouse genotypes quantified all histological parameters.

Skin semithin sections, 2 µm thick, were stained with toluidine blue and observed with a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope equipped with a Nikon digital camera DXM1200 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Ultrathin sections were obtained with an Ultracut ultramicrotome (Reichert Ultracut R-Ultramicrotome, Leika, Wien, Austria) and stained with uranyl acetate/lead citrate before observation by a Jeol CX100 transmission electron microscope (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan).

Flow Cytometry Analysis on Blood and Lymphoid Organs

Analyses were performed with a Calibur Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, Milan, Italy) with 2 lasers was used. The panels consisted of the subsequent cellular surface markers: CD4 (PE YTS 191.1.2, Immunotools, Friesoythe, Germany), CD44 (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC], IM7, BD Pharmingen; RRID AB _2076224), CD45 (FITC, 30-F11, BD Pharmingen; RRID AB_394610), CD62L (antigen-presenting cell, mMEL-14, BD Pharmingen; RRID AB_10895379), Ly-6C (FITC AL-21, BD Pharmingen; RRID AB_394628), CD115 (antigen-presenting cell AF598, eBioscience; RRID AB_2314130), CD11b (PE M1/70.15, Immunotools), CD11c (antigen-presenting cell HL3, BD Pharmingen RRID AB_398460), B220 (PerCP Cy5,5 RA3-6B2, BD Pharmingen; RRID AB_2034009), CD19 (FITC 1D3, BD Pharmingen RRID AB_395049), and CD5 (antigen-presenting cell 53-7.3, BD Pharmingen; RRID: AB_394562). Data were acquired in FCS (flow cytometry standard) format, processed and analyzed using the FCS Express V3 Research edition (De Novo Software, Inc). CD45 was used for the identification of total leukocytes. CD4+CD44−CD62L+ cells are indicated as T naive (TN), CD4+CD44+CD62L− cells are indicated as T effector memory (TEM), and CD4+CD44+CD62L+ cells are indicated as T central memory (TCM). CD11b+CD115+Ly6Clo cells are indicated as patrolling monocytes and CD11b+CD115+Ly6Chi as inflammatory monocytes. CD11chiCD11b+B220lo cells are indicated as myeloid and CD11cloCD11b−B220hi as plasmacytoid dendritic cells. CD19+CD5+ cells are indicated as B1a cells and CD19+CD5− as B1b.

In Vitro T-Cell Proliferation and Cytokine Production

Discoidal reconstituted HDL (rHDL) containing human apoA-I and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl phosphatidylcholine were prepared by cholate dialysis method, as described.31 Lymphocyte suspension from EKO lymph nodes was incubated with 5 µmol/L of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (Merck, Catalog no. 21888) for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark, diluted 10 times in PBS/FBS 2%/2 mmol/L EDTA, washed 3 times and resuspended in TexMACS medium. A total of 0.2×106 cells were plated in 96-well plate (U-bottom wells), coated with 0.5 µg/mL anti-CD3 (Biolegend, Catalog no. 152302; RRID AB_2650621) and 2.5 µg/mL anti-CD28 (Biolegend, Catalog no. 102102; RRID AB_312867), in 200 µL of medium containing 20 U/mL IL-2 (Preprotec, Catalog no. 200-02), with or without rHDL (10, 25, 50, and 100 µg/mL). Cells were incubated for 4 days at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

For cytokine production, at the end of the incubation, cells were pulsed with 0.1 µg/mL PMA (phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate; Merk, Catalog no. P1585) and 1 µg/mL ionomycin (Invitrogen, Catalog no. I24222) for 4 hours at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in the presence of Brefeldin A (1:1000, BD Bioscience, Catalog no. 555028). Cytokine analysis was performed by flow cytometry following the instructions from the fixation/permeabilization kit (BD Bioscience, Catalog no. 555028).

T cells were analyzed for the expression of extracellular markers, intracellular cytokines, proliferation, cellular viability, and lipid abundance by flow cytometry.

Immunophenotyping was performed on resting and activated lymphocytes. For live and dead cells discrimination, cell suspension was stained with 100 μL of a 1:1000 dilution of the LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen, Catalog no. L34965) in PBS at 4 °C for 30 minutes. Single cell suspensions were then incubated with antibody mixtures at 4 °C for 30 minutes and then washed with PBS/FBS 2%/EDTA 2 mmol/L. For intracellular staining, first cells were fixed and permeabilized according to manufacturer instructions and then incubated with specific antibodies at 4 °C for 30 minutes, washed and analyzed as described.32 Antibodies are listed in the Major Resources Table in the Supplemental Material.

For detection of lipid rafts, cells were incubated with 2 μg/mL of Cholera Toxin-FITC (Merck, Catalog no. C1655) conjugated for 30 minutes at 4 °C or with 25 μg/mL 100 filipin (Merck, Catalog no. F9765) for 30 minutes at 30 °C, washed and analyzed.

Samples were acquired with BD LSRII Fortessa and analyzed with Novoexpress 1.3.3 software (Agilent Technologies Inc). Gating strategy was reported in Figure S16.

RNA Extraction

Total RNA was isolated from mouse tissues and extracted as previously described.33 RNA was quantified and checked, and 1 μg RNA was retrotranscribed to cDNA. Possible gDNA contamination was ruled out as described.34

RNA-Seq Analysis

For RNA-seq analysis, the quality of the mRNA was tested using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, CA), and only libraries with RNA integrity number ≥7 were included. RNA samples were processed using the RNA-seq Sample Prep kit from Illumina (Illumina, Inc, CA). Eight to 9 tagged libraries were loaded on one lane of an Illumina flowcell, and clusters were created using the Illumina Cluster Station (Illumina, Inc, CA). Clusters were sequenced on a Genome Analyzer IIx (Illumina, Inc, CA) to produce 50nt single-reads. Data sets can be accessed at NCBI (Gene Expression Omnibus) GSE202237.

Bioinformatics Analysis

Preprocessing of Reads

Raw sequence reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic software35 and applying the leading, trailing, and slidingwindows operations, with the following quality score cutoffs, respectively: Qs ≥15, Qs ≥10, and average Qs ≥15.

Differential Gene Expression

Transcript abundance estimation and differential expression analyses were performed using the standard Bowtie-Tophat-Cuffdiff pipeline on the Refseq annotation of the mm10 mouse reference genome assembly, as obtained from the following: https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/M_musculus/annotation_releases/current/. Transcriptome assembly functions of cufflinks were deactivated and only established transcripts annotations were used.36

Differential expression analyses were executed by performing direct pairwise comparisons between the conditions under study. A false discovery rate cutoff value of 0.05 was applied for the identification of differentially expressed genes. Functional enrichment analyses, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome (KEGG) and reactome pathways, were performed with reString (version 0.1.18).37

Statistical Analyses

Sample size for histological and imunohistochemical analyses was calculated based on previously published data on atherosclerosis in EKO mice and EKO mice overexpressing human apoA-I.38,39 Plaque size in EKO mice was expected to be about 5 times larger than in DKO/hA-I mice. A lack of atherosclerosis development was expected in WT mice, and the development of plaques in DKO mice was hypothesized 2 times larger than in EKO mice. Based on these premises, a sample size of 6 per experimental group achieves 92% power to detect the hypothesized differences among the means using an F test at 5% significance level. A higher number of samples was cautiously used for plasma lipid measurements and for most of the analyses on lymphocyte class distribution.

Analyses were performed with R40 and GraphPad Prism version 9.3.0. Significant differences were determined by ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test or by Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn post hoc test, according to the check of normality of residuals (Shapiro-Wilk test) and homoscedasticity of data (Levene test). Statistical analyses are detailed in each figure or table caption, specifying for which parameters the nonparametric procedure was applied.

Numerical data is shown as box plots, where the upper and lower ends of the boxes indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The length of the box shows the interquartile range within which 50% of the values are located. The solid gray lines denote the median. Precise adjusted P values are shown in Table S1. In most figures, approximate P values are provided to improve readability (ex. P<0.05, P<0.01).

Results

ApoA-I Deficiency in EKO Mice Leads to Normocholesterolemia Associated to Negligible HDL Levels

At the end of the experimental period, body weight was comparable in WT, DKO, and DKO/hA-I mice and significantly higher in EKO mice (Figure S1A).

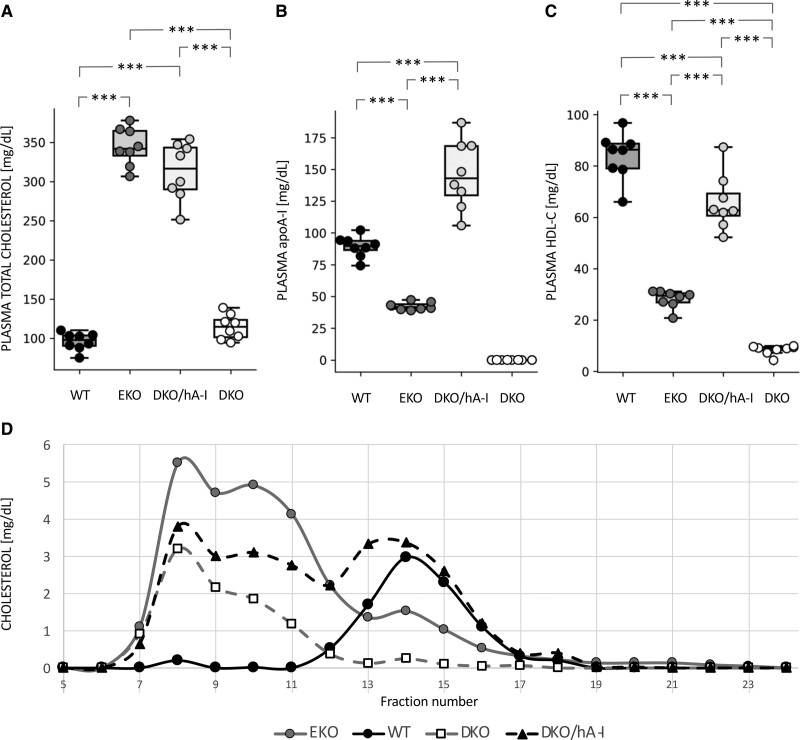

Plasma total cholesterol concentration in DKO and WT mice was comparable, and ≈3-fold lower than the concentration observed in EKO mice and DKO/hA-I mice (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Plasma cholesterol and apoA-I (apolipoprotein A-I) levels. Plasma total cholesterol (A), apoA-I (B), HDL-C (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (C) concentrations, and cholesterol distribution among lipoproteins by fast protein liquid chromatography in the 4 genotypes (n=8). Statistically significant differences were determined by ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc. ***P<0.001. Precise adjusted P values are shown in Table S1.

As expected, apoA-I was absent in plasma of DKO mice. ApoA-I concentration in EKO mice was approximately half of that measured in WT. The overexpression of the human APOA1 transgene strongly increased apoA-I plasma levels of DKO/hA-I (Figure 1B). HDL-C concentration was about 10-fold lower in DKO and 3-fold lower in EKO than in WT mice, whereas DKO/hA-I mice showed higher HDL-C levels than those measured in EKO and DKO (Figure 1C). Non-HDL-C levels were significantly different among all genotypes (Table S1). Specifically, plasma non-HDL-C concentration was 12.2±3.7 mg/dL in WT, 316.3±23.0 mg/dL in EKO, 247.3±31.2 mg/dL in DKO/hA-I, and 106.2±16.4 mg/dL in DKO.

Fast protein liquid chromatography analysis confirmed a dramatic cholesterol accumulation in the VLDL (very-low-density lipoprotein) and LDL fractions of EKO mice and a greatly reduced HDL-C peak compared with that of WT mice (Figure 1D). In DKO mice, the HDL-C peak was almost absent and cholesterol in the VLDL and LDL fractions was much lower than in EKO mice. DKO/hA-I mice displayed an HDL-C peak close to that of WT and a relevant cholesterol accumulation in the VLDL and LDL fractions.

HDL Deficiency Worsens Atherosclerotic Plaque Development at the Aortic Sinus and in Coronary Arteries

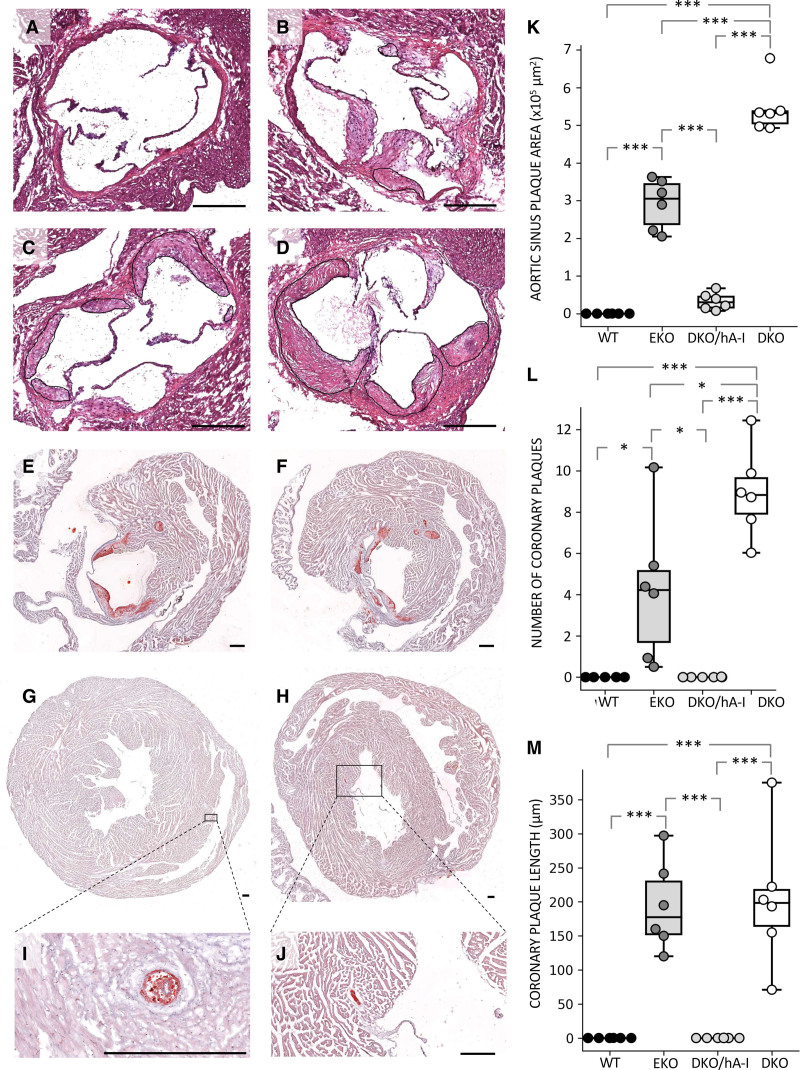

The apoA-I deficiency in the apoEKO background (DKO) caused an increase of plaque extent at the aortic sinus compared with that measured in EKO mice. Conversely, apoA-I overexpression in DKO/hA-I mice dramatically reduced atherosclerotic plaque size at the aortic sinus compared with both DKO and EKO mice. As expected, no plaques developed at the aortic sinus of WT mice (Figure 2A through 2D and 2K).

Figure 2.

Atherosclerosis development at the aortic sinus and coronary arteries. Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained pictures of atherosclerosis development at the aortic sinus of wild type (WT; A), apoE/apoA-I double deficient (DKO) mice overexpressing human apoA-I (DKO/hA-I; B), apoE deficient (EKO; C) and DKO mice (D). Representative oil red O (ORO) stained pictures of plaque development at the left atrioventricular valves of EKO (E) and DKO mice (F), and in the right coronary artery of EKO (G) and DKO mice (H). Magnifications of the same coronary plaques are shown (I and J). Atherosclerotic plaque quantification at the aortic sinus (K), number of plaques in coronary arteries and coronary branches (L), and average plaque length in coronary arteries (M) are also shown (n=6). Bar length: 250 μm. Statistically significant differences were determined by ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; and ***P<0.001. Precise adjusted P values are shown in Table S1.

The area occupied by macrophages in the plaques of DKO/hA-I mice was about ten times lower than in EKO and DKO mice, since DKO/hA-I developed smaller plaques (Figure S2C and S2E). Macrophage area expressed as percentage of total area was instead comparable among DKO/hA-I, DKO, and EKO mice (Figure S2F).

An increased count of CD3+ T lymphocytes was observed in the atherosclerotic plaques of DKO versus DKO/hA-I mice (Figure S3E). However, no differences were observed when CD3+ cell counts were normalized to plaque area (Figure S3F). In addition, the presence of CD3+ cells was evaluated in the myocardial tissue immediately surrounding the aortic sinus: the count of CD3+ cells was significantly increased in EKO and DKO mice compared with that in DKO/hA-I mice (Figure S3G).

A feature observed only in DKO and EKO mice was the presence of lesions at the left atrioventricular valves (Figure 2E and 2F).

The presence of atherosclerotic plaques within the left and right coronary arteries arising from the aortic sinus was detected in 100% of DKO and 30% of EKO mice (Figure 2G through 2J). The average number of atherosclerotic plaques in left and right ventricular coronary branches was more than doubled in DKO mice compared with EKO mice (Figure 2L and Figure S4). The average length of coronary plaques was comparable in DKO and EKO mice (Figure 2M). No plaques developed in the coronary arteries of DKO/hA-I and WT mice (Figure 2L and 2M).

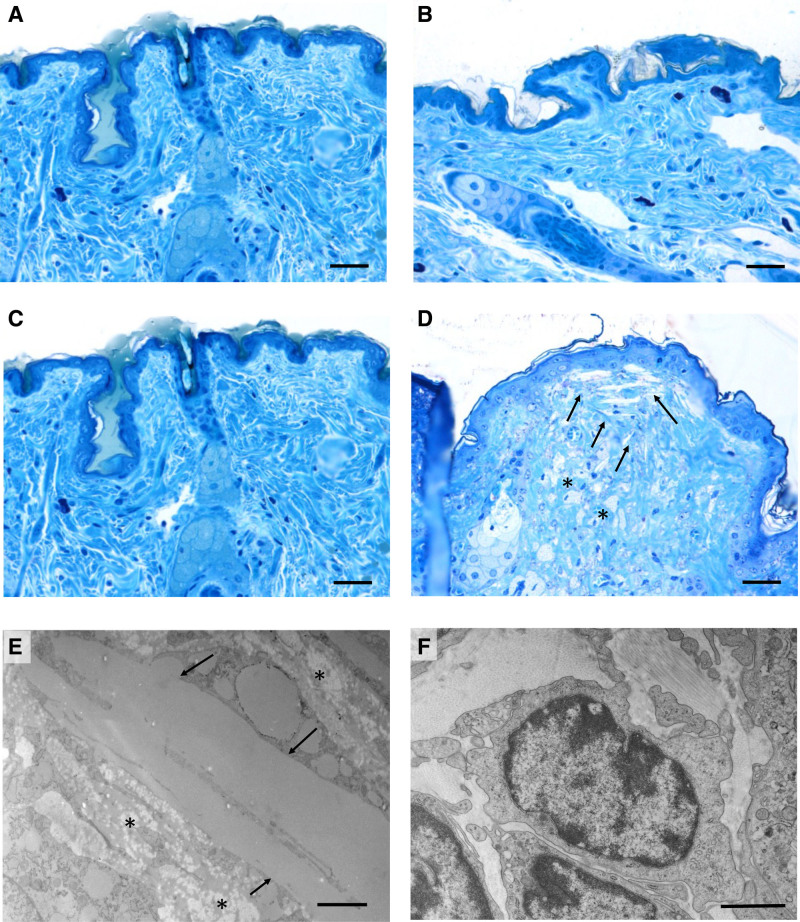

The Pathological Skin Phenotype Determined by HDL Deficiency Is Rescued by hA-I Overexpression

In accordance with our previous findings,22 DKO mice displayed hair loss and a pale color of the skin. These features were not observed in any other genotype. Structural and ultrastructural features of the skin were investigated in semithin and in ultrathin sections stained with toluidine blue, respectively. By light microscopy, the dermal and the epidermal compartment exhibited a normal organization in WT, in EKO, and DKO/hA-I mice (Figure 3A through 3C). In DKO mice, the subpapillary dermis appeared disarranged and filled with cholesterol clefts (Figure 3D and 3E) and foam cells were interspersed in the reticular dermis (Figure 3D and 3E). Infiltrated lymphocytes were present in the dermis of DKO mice (Figure 3F). In addition, neutral lipid deposition was increased in the thickened dermis of DKO mice, compared with the other genotypes (Figure S5).

Figure 3.

Light and transmission electron microscopy of mouse skin. Araldite semithin sections after toluidine blue staining of skin from wild type (WT; A), apoE/apoA-I double deficient (DKO) mice overexpressing human apoA-I (DKO/hA-I; B), apoE deficient (EKO; C), and DKO mice (D). Araldite ultrathin sections of DKO skin (E and F): cholesterol clefts (arrows) and foam cells (asterisks) accumulation in the dermis are shown in D and E; lymphocytes in the dermis of DKO are shown in F. Bars: A–D: 60 μm; E: 2 μm; F: 1 μm.

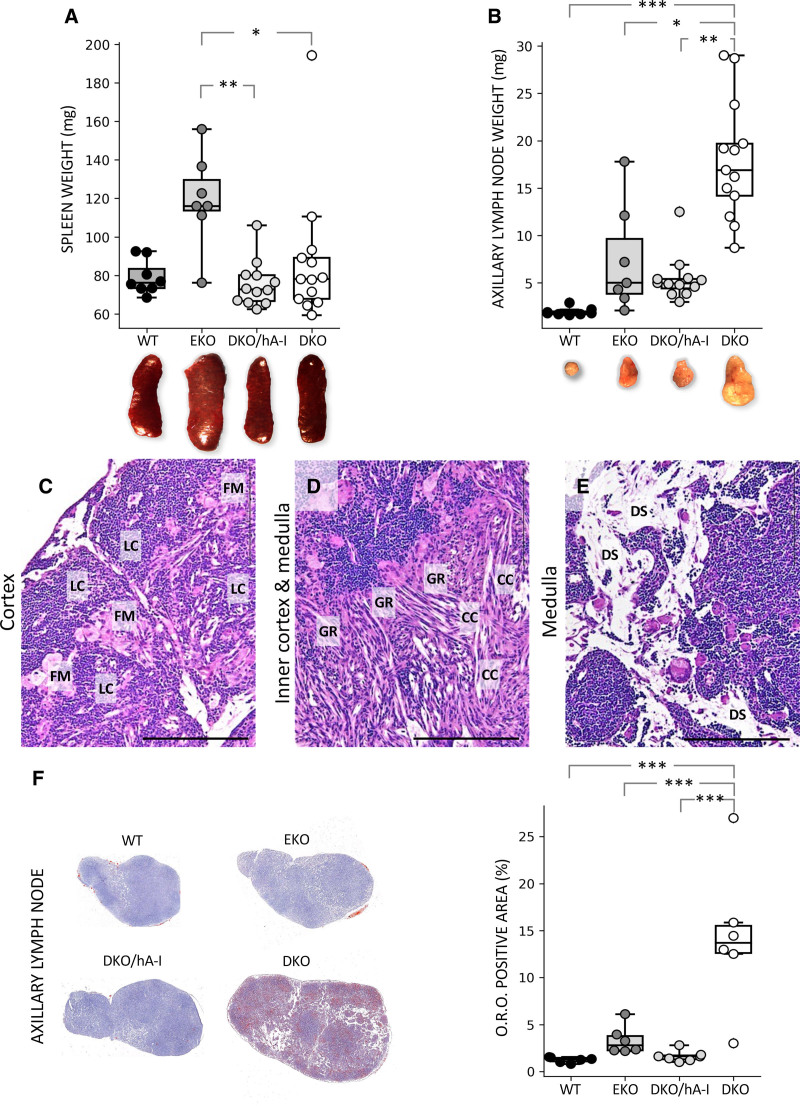

HDL Deficiency Results in Deep Alterations in Skin-Draining Lymph Nodes

The size and weight of the spleen in WT, DKO/hA-I, and DKO were comparable; on the contrary, spleens from EKO mice had an increased weight compared with DKO/hA-I and DKO mice (Figure 4A). Histological analysis did not reveal differences among groups. No lipid deposition was observed in any genotype (Figure S6). When spleen weight was normalized to body weight, no significant differences were observed (Figure S1B).

Figure 4.

Weight of spleen and axillary lymph node in the 4 genotypes and histology of apoE/apoA-I double deficient (DKO) axillary lymph node. Gross anatomic appearance and weights (n=7–13) of the spleen (A) and the axillary lymph node (B). Representative photomicrographs of axillary lymph node from DKO mice. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images show large, foamy macrophages in the cortex, surrounded by lymphoid cells (C), presence of granulomatous reactions around cholesterol crystals in the inner cortex and the medulla (D), dilation of subcapsular, corticomedullary and medullary sinuses (a detail of medullary sinuses is shown in E). Oil Red O (O.R.O.) staining (n=6) of axillary lymph node cryosections (F). Statistically significant differences were determined in A and B by Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn post hoc test and in F by ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc. CC indicates cholesterol crystals; DS, dilated sinuses; EKO, apoE deficient; FM, foamy macrophages; GR, granulomatous reactions; hA-I, human apoA-I; LC, lymphoid cells; and WT, wild type. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; and ***P<0.001. Bar length =100 μm. Precise adjusted P values are shown in Table S1.

DKO mice were characterized by increased size and weight of the skin-draining axillary lymph node, compared with the other genotypes (Figure 4B), a finding further confirmed by the normalization of lymph node weight to body weight (Figure S1C). At the histological level, 3 main features were observed only in DKO mice: (1) the accumulation of large macrophages, often characterized by a foamy cytoplasm, as single cell or in small groups in the cortex, surrounded by lymphoid cells (Figure 4C and Figure S7); (2) the presence of granulomatous reactions in the inner cortex and the medulla, localized around a large number of multinucleated macrophages and cholesterol crystals (Figure 4D and Figure S7); and (3) a dilation of subcapsular, corticomedullary, and medullary sinuses (Figure 4E). Moreover, a moderate deposition of neutral lipids within the lymph node parenchyma was found in WT, EKO, and DKO/hA-I mice, whereas in DKO mice a dramatic lipid accumulation was detected (Figure 4F).

HDL Deficiency Increases the Amount of CD4+ TEM in Blood, Skin-Draining Lymph Nodes and Spleen

Total white blood cells (CD45+) were significantly higher in DKO versus WT mice. Comparable CD45+ counts were observed in the spleen of the 4 genotypes. CD45+ cells were increased in the axillary lymph node of DKO mice versus all the other groups. Total CD4+ counts were not affected by genotype in blood, spleen, and axillary lymph node (Figure S8).

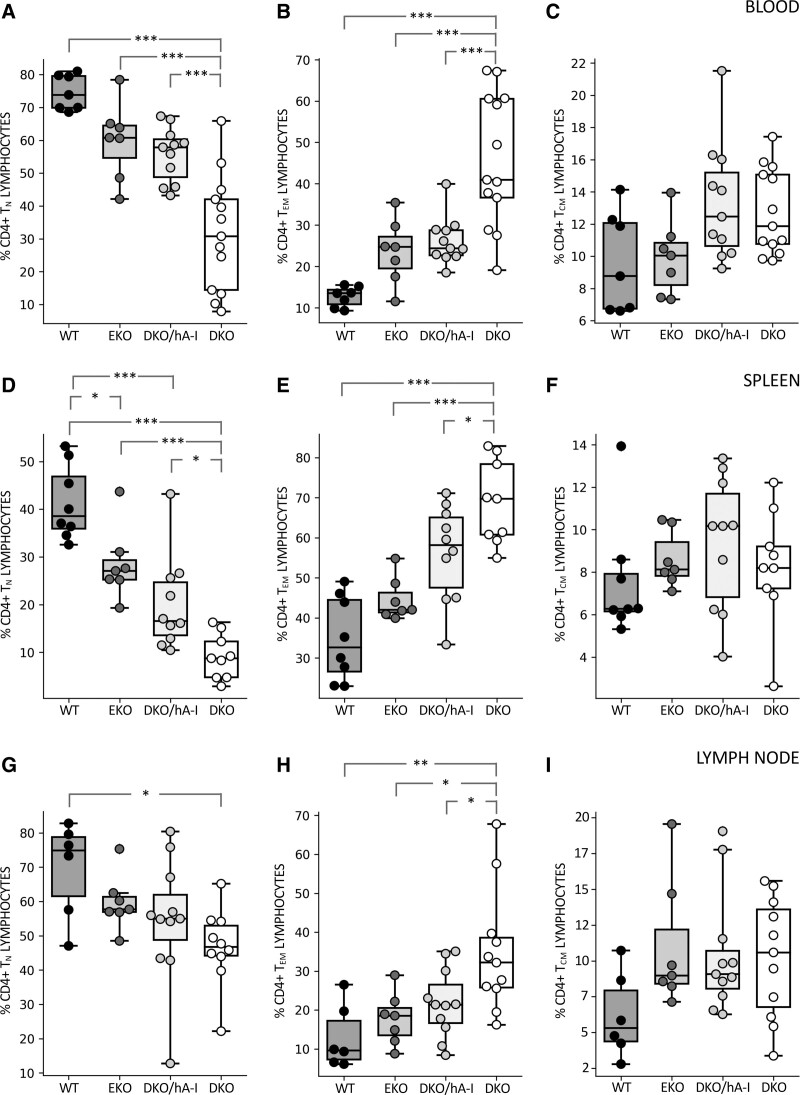

The analysis of CD4+ T-cell subsets (TN, TEM, and TCM) revealed that, in peripheral blood and spleen, DKO mice had an increased percentage of TEM and a concomitant reduced percentage of TN lymphocytes compared with all the other genotypes (Figure 5A and 5B). In the axillary lymph node, DKO mice showed a significantly increased percentage of TEM compared with the other genotypes and a tendency towards a reduced percentage of TN, significant only versus WT mice (Figure 5C). The percentage of TCM cells resulted always unaffected by genotype.

Figure 5.

CD4+ T-cell subsets in blood, spleen, and axillary lymph node. Flow cytofluorimetric evaluation of the percentage composition of CD4+ T-cell subsets is shown in blood (A–C), spleen (D–F), and axillary lymph node (G–I; n=7–13). Statistically significant differences were determined by ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, except for (C) and (I) which were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn post hoc test. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; and ***P<0.001. Precise adjusted P values are shown in Table S1. DKO indicates apoE/apoA-I double deficient; DKO/hA-I, DKO mice overexpressing human apoA-I; EKO, apoE deficient; and WT, wild type.

No differences were found among the 4 genotypes in monocyte subsets distribution (inflammatory Ly6Chi and patrolling Ly6Clo) in peripheral blood. B1a lymphocytes were increase in EKO mice compared with DKO/hA-I and DKO mice, both in spleen and in axillary lymph node (Figure S9).

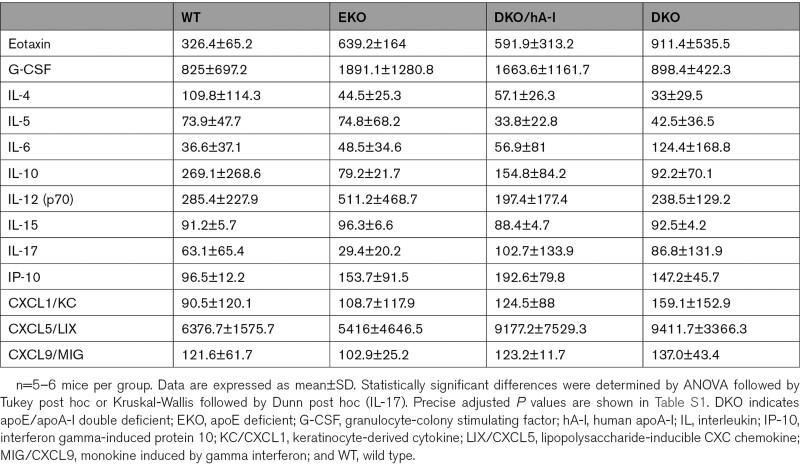

The concentration of plasma cytokines did not show differences among genotypes (Table).

Table.

Plasma Cytokine Concentrations in the 4 Genotypes (pg/mL)

rHDL Influence CD4+ and CD8+ Cells Proliferation In Vitro

To investigate the potential role of apoA-I/HDL in modulating T lymphocyte proliferation/activation, lymphocytes were isolated from lymph nodes of EKO mice to test cell proliferation and cytokine release by polyclonal stimulation (anti-CD3/28 antibodies plus IL-2) in the presence of increasing concentration of rHDL (10, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL) for 4 days. rHDL reduced both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation in a concentration dependent manner (Figure S13A and S13B). Changes in cytokine production were evaluated in activated T cells following stimulation with PMA/ionomycin. IFN (Interferon)-γ and IL-17 production (marking T-cell polarization toward Th1 and Th17, respectively41) was decreased in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells following incubation with rHDL (Figure S13C through S13F). A similar trend was observed for IL-15R and IL-4, despite a statistical significance was appreciated only for CD8+ T cells (Figure S14).

To further investigate the ability of HDL to affect cell membrane lipids, lipid rafts abundance and cholesterol content in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell membrane were evaluated by Cholera Toxin-subunit B staining and filipin staining. HDL significantly reduced, in a concentration dependent manner, both lipid raft abundance and cholesterol content in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figure S15).

The Transcriptional Expression Profile of Skin-Draining Lymph Nodes of HDL-Deficient Mice Reveals Increased Activation of the Immune System and an Unbalanced Expression of Genes Involved in Energy Metabolism

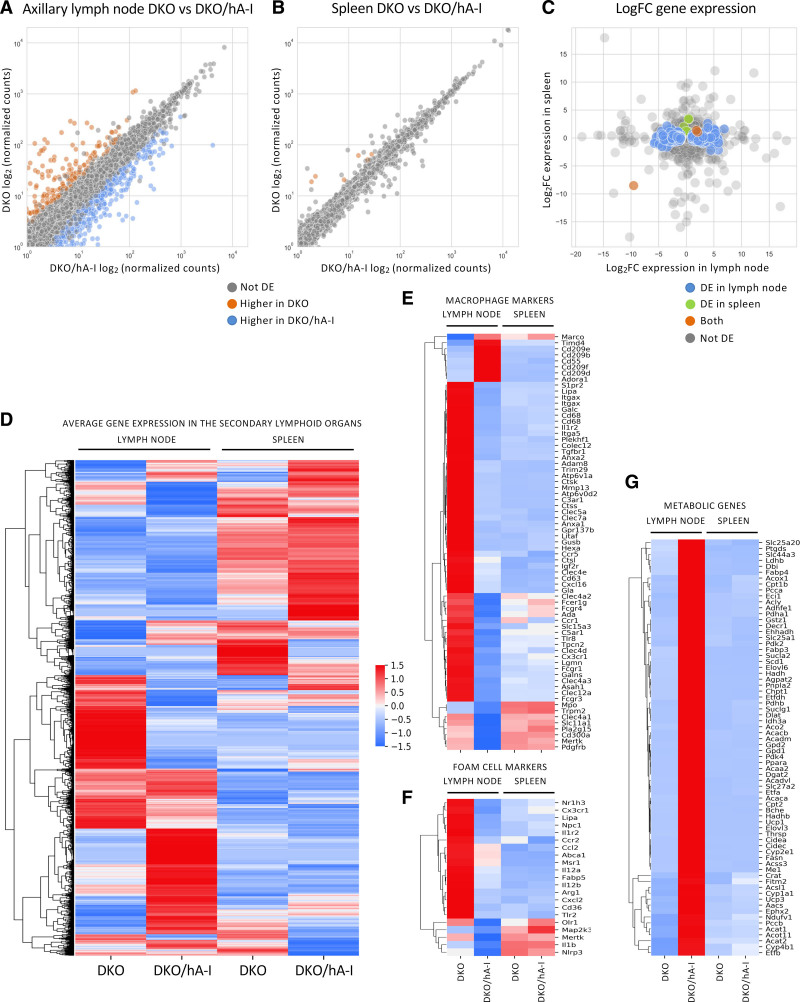

A comparison of the transcriptional expression profiles was performed in the axillary lymph nodes and in the spleen of DKO and DKO/hA-I mice (Figure 6A through 6D).

Figure 6.

Transcriptional expression profiles of axillary lymph node and spleen of apoE/apoA-I double deficient (DKO) and DKO mice overexpressing human apoA-I (DKO/hA-I) mice. The average of normalized counts per gene between DKO/hA-I (x axis) and DKO (y axis) were compared in axillary lymph node (A) and spleen (B). The values spanned several orders of magnitude and were log2-transformed. The log2 fold change (DKO vs DKO/hA-I) is shown for all transcripts in lymph nodes (x axis) and in the spleen (y axis; C). Values greater than 0 denote genes with higher expression in DKO; values lower than 0 denote genes with higher expression in DKO/hA-I. Heatmap with the Z-scored average expression for all genes in the secondary lymphoid organs (D). Heatmaps with the gene expression signature for macrophages (E) and foam cells (F). Heatmap of metabolic genes with significantly increased expression in the axillary lymph node of DKO/hA-I mice (G). n=3 for DKO and DKO/hA-I. DE indicates differentially expressed genes.

A total of 784 genes were identified as differentially expressed genes in the axillary lymph node: 513 were upregulated, whereas 271 were downregulated in DKO compared with DKO/hA-I mice (Figure 6A).

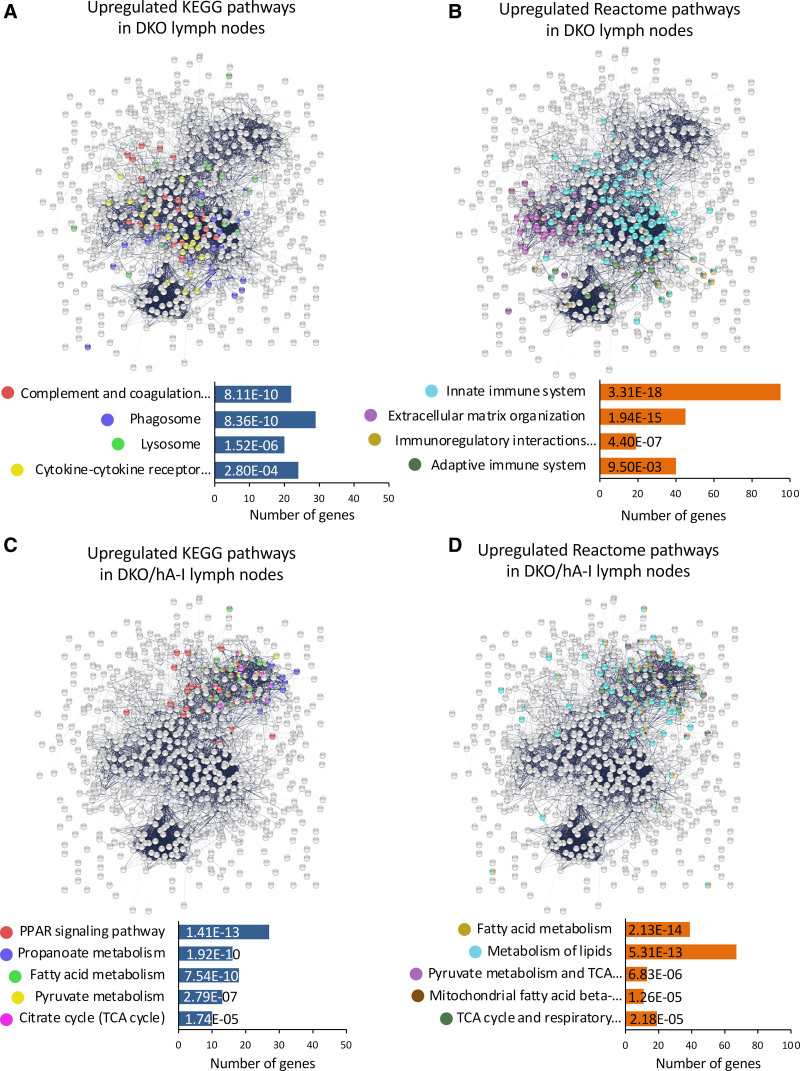

In DKO mice, functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes indicated an increased activation of the immune system, with particular reference to the phagocytic activity (mmu04610 Complement and coagulation cascades, mmu04145 Phagosome, mmu04142 Lysosome, mmu04060 cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction; Figure 7A). The reactome associated to the genes with an increased expression in DKO mice refined this observation: the activation of both the innate (MMU-168249) and adaptive immune system (MMU-1280218) was accompanied by an increased immunoregulatory interaction between lymphoid and nonlymphoid cells (MMU-198933; Figure 7B). In addition, extracellular matrix organization (MMU-1474244) was modulated as well (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Functional enrichment of differentially expressed genes in the axillary lymph nodes of apoE/apoA-I double deficient (DKO) and DKO mice overexpressing human apoA-I (DKO/hA-I) mice. The most relevant KEGG and reactome pathways enriched in DKO (A and B, respectively) and in DKO/hA-I (C and D, respectively) are reported. PPAR indicates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

Interestingly, macrophage-specific markers (Figure 6E and Figure S10), particularly those associated with the differentiation of macrophages to lipid-laden foam cells, displayed and increased expression in DKO mice, the group characterized by exacerbated atherosclerosis (Figure 6F and Figure S11).

In the axillary lymph node of DKO mice a reduced expression of several genes involved in cell metabolism was observed (Figure 6G and Figure S12). Those genes were largely involved in pathways related to energy metabolism (mmu03320 PPAR [peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor] signaling pathway, mmu00640 propanoate metabolism, mmu01212 fatty acid metabolism, mmu00620 pyruvate metabolism, and mmu00020 citrate cycle; Figure 7C). Similarly, the reactome indicated in DKO mice a reduction in metabolism of lipids (MMU-556833), fatty acid metabolism (MMU-8978868), pyruvate metabolism and TCA (tricarboxylic acid) cycle (MMU-71406), TCA cycle and respiratory electron transport (MMU-1428517), and mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation (MMU-77289; Figure 7D).

In the spleen, the comparison between the gene expression profiles of DKO and DKO/hA-I mice did not highlight relevant differences except for a handful of genes. Of those, 7 were upregulated (Apol11b, Cyr61, Dnaja1, Dnajb1, Hspa1a, Hspa1b, and Hsph1) and one was downregulated in DKO mice (Rpl31-ps12; Figure 6B and 6C).

Discussion

DKO mice, almost completely devoid of HDL and with plasma total cholesterol levels comparable to those of WT mice, showed deep alterations in the skin structure, with a massive dermal accumulation of cholesterol clefts, foam cells, and T lymphocytes. The skin features of this mouse model, partially described previously22 were further investigated with the inclusion of DKO/hA-I. The presence of xanthomas in the skin of DKO mice was paralleled by partial hair loss, a thickened dermal layer filled with inflammatory cells and increased neutral lipid deposition. Interestingly, apoA-I expression, both at low (EKO mice) and high (DKO/hA-I mice) levels, was able to reverse these skin abnormalities. The skin and plasma lipid phenotype observed in DKO mice strongly resembles the condition of human subjects affected by genetic apoA-I deficiency, who are similarly characterized by xanthoma formation in the absence of elevated plasma lipid levels.42

DKO/hA-I and EKO mice were both characterized by plasma total and non-HDL-C levels significantly higher than DKO mice. Despite that, atherosclerotic plaque development at the aortic sinus of DKO mice was about twice as high as in EKO. Of note, individuals with apoA-I/HDL deficiency in the absence of other plasma lipid alterations, generally develop premature coronary heart disease.43

In DKO/hA-I, plaque area was dramatically lower compared with DKO and EKO mice. A reduced atherosclerosis development by apoA-I overexpression has been previously described in hyperlipidemic EKO and LDLrKO mice21,38,44 and atherosclerosis worsening by apoA-I deletion has been shown in LDLrKO mice fed a high-fat/high-cholesterol diet,44 where cholesterolemia was not affected by apoA-I ablation. Interestingly, in our study, DKO mice showed a strong exacerbation of atherosclerosis development versus EKO, in spite of much lower non-HDL-C levels. Altogether, apoA-I, in our experimental setting, appeared to be a major determinant of atherosclerosis development, regardless of the lipidemic status. In fact, atherosclerosis extent in the 3 atheroprone genotypes was independent of non-HDL-C levels and it was inversely related to apoA-I plasma concentrations or to HDL-C levels.

Observational studies in humans have established an inverse correlation between HDL-C levels and cardiovascular disease.2 However, a strong elevation of HDL-C levels caused by genetic variants or pharmacological treatments have been associated to a higher cardiovascular mortality.8,45,46 A similar condition has been found in mice double knockout for SR-B1 and apoE, characterized by a considerable elevation of HDL-C levels and by a premature and severe atherosclerosis.47 These evidences clearly indicate that plasma HDL-C concentration may not always reflect HDL functionality, especially at very high levels. To reconcile these observations with our results, we may hypothesize that HDL in both EKO and DKO/hA-I mice are functional and associate to atheroprotection in a dose-dependent manner.

In addition to the aortic sinus, EKO mice develop atherosclerosis in the aorta and in brachiocephalic arteries,48,49 whereas plaques in coronary arteries are less consistently observed.50 Genetically modified mouse models of coronary atherosclerosis have been developed over the years, but they require high-fat/high-cholesterol diets to exhibit coronary lesions.51,52 The only model developing coronary atherosclerosis without any dietary challenge is the EKO/SR-B1KO mouse, characterized by severe hypercholesterolemia and a high rate of mortality by 6 weeks of age.47 In the present study, normal laboratory diet-fed DKO mice showed an exaggerated plaque development also in the coronary arteries, with several lesions observed in coronary branches. This condition did not associate to an increased mortality rate within the time frame considered (up to 30 weeks of age). DKO mice might, therefore, represent a valuable model of coronary atherosclerosis.

As the alteration of the HDL system was shown to affect local and systemic immunoinflammatory responses,9 we deeply characterized tissue and systemic immune profile. Interestingly, DKO mice showed enlarged skin-draining axillary lymph nodes, characterized by the presence of foamy macrophages, granulomatous reactions, cholesterol crystals, dilation of sinuses, and increased lipid deposition. In contrast, WT and EKO mice did not develop any of these alterations and human apoA-I overexpression in DKO/hA-I mice reversed the DKO alterations.

Similarly to our observation, Wilhelm et al18 thoroughly described an enlargement of skin-draining lymph nodes caused by increased lipid accumulation and expansion of macrophages, dendritic cells, T and B lymphocytes in cholesterol-fed LDLrKO/A-IKO mice compared with LDLrKO mice.

Of note, cholesterol accumulation in skin-draining lymph nodes of LDLrKO/A-IKO mice appeared to be mainly triggered by hypercholesterolemia, whereas in our model an overtly altered lymph node histology arose in normocholesterolemic conditions and was possibly triggered by HDL deficiency itself.

This condition, possibly deriving from the almost complete HDL deficiency, somehow mimics the impaired cholesterol flow through the lymphatics observed in experimental models with dysfunctional lymphatic drainage. In this regard, it has been demonstrated that atherosclerosis regression secondary to a reduction of plasma cholesterol levels, in ezetimibe-treated EKO mice, is obtained only in the presence of an efficient aortic lymphatic drainage that prevents cholesterol and immune cell accumulation in the aortic adventitia.53

There is considerable evidence from studies in mice demonstrating that apoA-I possesses anti-inflammatory properties54 and immunoregulatory functions15 possibly affecting atherosclerosis development.55 For this reason, we have characterized the presence of TEM, TCM, or TN CD4+ T lymphocytes in the axillary skin-draining lymph node, spleen and blood. The percentage of TEM was significantly higher in DKO mice in the 3 districts analyzed. This increase was counterbalanced by a reduced percentage of TN. The percentage of TCM resulted always unaffected by genotype. Of note, alterations in the distribution of T lymphocytes were not observed in the other genotypes, including EKO mice. That suggests that even low levels of apoA-I are sufficient to switch off the inflammation and T lymphocyte activation consequent to apoA-I deficiency.

The present study was not designed to evaluate the minimal effective level of apoA-I required to correct the phenotype driven by apoA-I/HDL deficiency. However, based on previous evidences,18,56 it can be hypothesized that even extremely low levels of apoA-I can preserve leukocyte homeostasis.

In vitro experiments with rHDL, showed that apoA-I directly affects CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation. HDL also modulated cholesterol and lipid rafts abundance in T cells plasma membrane and this possibly influenced their polarization and activation status. The modulation of lipid raft composition and cholesterol abundance in plasma membrane of T cells has been postulated as a key mechanism affecting T-cell biology57; of note cholesterol/lipid rafts abundance at the immunologic synapse contributes to cluster the signaling receptors involved in the activation of adaptive immune response.58–60

Although several studies have already investigated the transcriptional profile of skin-draining lymph nodes under skin inflammatory conditions,61,62 to our knowledge, this is the first report in which the gene expression profile of skin-draining lymph nodes specifically obtained from dyslipidemic mouse models is described. In accordance with the histological findings, it was not surprising to detect a greater expression of genes attributable to an increased immune response in the lymph node of DKO versus DKO/hA-I mice. It was also interesting to note the enrichment of pathways indicative of increased phagocytic and lysosomal activity, which was reported to be critical in the immune response.63 Consistent with the unchanged accumulation of lipids in the splenic parenchyma, the expression of genes involved in phagocytosis, lysosomal degradation, as well as foam cell formation markers, was also comparable between genotypes.

Beyond the increased immune/inflammatory response, the transcriptome analysis also revealed a reduced enrichment of several lipid-related pathways in the lymph node of DKO versus DKO/hA-I mice. This result is of extreme interest and, once again, most likely caused by the increased presence of foamy macrophages in the lymph node parenchyma.

The PPAR signaling pathway, and in particular the expression of the gene coding for PPAR-α, was significantly reduced in DKO mice. Several studies have provided direct evidence for a critical role of PPAR-α in the regulation of cholesterol and fatty acid homeostasis in macrophages.64

In the present study, several genes involved in fatty acid beta-oxidation had a reduced expression in DKO mice. It has been demonstrated that the impairment of fatty acid beta-oxidation, through the deletion of key mitochondrial enzymes, increases the formation of foam cells in vitro and worsens atherosclerosis development.65

In addition to fatty acid beta-oxidation, the tricarboxylic acid (Krebs) cycle and oxidative phosphorylation were downregulated in the DKO lymph node. This typically occurs in proinflammatory M1 macrophages, characterized by their ability in presenting antigens to T lymphocytes for the initiation of adaptive responses.66

Altogether, our results shed new light on the role of apoA-I/HDL in cholesterol homeostasis, coronary atherosclerosis, and immunoinflammation and could contribute to unravel the clinical condition of HDL deficiency consequent to mutations of the apoA-I gene.

Article Information

Acknowledgments

We are in debt to Elda Desiderio Pinto for administrative assistance. Dr Alice Colombo is supported by the 37th cycle PhD programme in “Scienze farmacologiche sperimentali e cliniche,” Università degli Studi di Milano.

Sources of Funding

This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the ERA-Net Cofund action no. 727565 (OCTOPUS project) and the MIUR (G. Chiesa). This work was also supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) AtheroRemo, grant no. 201668 (G. Chiesa), by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2012–2017) RiskyCAD, grant no. 305739 (G. Chiesa), by Fondazione CARIPLO (2011-0645; G. Chiesa), by grants from MIUR Progetto Eccellenza and by Fondazione Cariplo grant no. 2016-0852 (G.D. Norata); Telethon Foundation grant. No. GGP19146 (G.D. Norata); PRIN 2017K55HLC (G.D. Norata).

Disclosures

None.

Supplemental Material

Figures S1–S16

Tables S1–S2

Major Resources Table

Supplementary Material

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ABCA1

- ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

- ABCG1

- ATP-binding cassette transporter G1

- apoA-I

- apolipoprotein A-I

- DKO

- apoE/apoA-I double deficient

- DKO/hA-I

- DKO mice overexpressing human apoA-I

- EKO

- apoE deficient

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- G-CSF

- granulocyte-colony stimulating factor

- HDL

- high-density lipoprotein

- HDL-C

- HDL-cholesterol

- IFN

- interferon

- IL

- interleukin

- IP-10

- interferon gamma-induced protein 10

- KC/CXCL1

- keratinocyte-derived cytokine

- LDLrKO

- low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout

- LIX/CXCL5

- lipopolysaccharide-inducible CXC chemokine

- MIG/CXCL9

- monokine induced by gamma interferon

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- rHDL

- reconstituted HDL

- TCM

- central memory T lymphocytes

- TEM

- effector memory T lymphocytes

- TN

- naive T lymphocytes

- WT

- wild type

M. Busnelli and S. Manzini contributed equally.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/ATVBAHA.122.317790.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 854.

References

- 1.Ouimet M, Barrett TJ, Fisher EA. HDL and reverse cholesterol transport. Circ Res. 2019;124:1505–1518. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.312617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toth PP, Barter PJ, Rosenson RS, Boden WE, Chapman MJ, Cuchel M, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Davidson MH, Davidson WS, Heinecke JW, et al. High-density lipoproteins: a consensus statement from the national lipid association. J Clin Lipidol. 2013;7:484–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geller AS, Polisecki EY, Diffenderfer MR, Asztalos BF, Karathanasis SK, Hegele RA, Schaefer EJ. Genetic and secondary causes of severe HDL deficiency and cardiovascular disease. J Lipid Res. 2018;59:2421–2435. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M088203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haase CL, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Qayyum AA, Schou J, Nordestgaard BG, Frikke-Schmidt R. LCAT, HDL cholesterol and ischemic cardiovascular disease: a Mendelian randomization study of HDL cholesterol in 54,500 individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E248–E256. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmes MV, Asselbergs FW, Palmer TM, Drenos F, Lanktree MB, Nelson CP, Dale CE, Padmanabhan S, Finan C, Swerdlow DI, et al. ; UCLEB consortium. Mendelian randomization of blood lipids for coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:539–550. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trinder M, Walley KR, Boyd JH, Brunham LR. Causal inference for genetically determined levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and risk of infectious disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:267–278. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madsen CM, Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG. Low HDL cholesterol and high risk of autoimmune disease: two population-based cohort studies including 117341 individuals. Clin Chem. 2019;65:644–652. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.299636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madsen CM, Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG. Extreme high high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is paradoxically associated with high mortality in men and women: two prospective cohort studies. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2478–2486. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pirillo A, Catapano AL, Norata GD. HDL in infectious diseases and sepsis. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;224:483–508. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-09665-0_15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parolini C, Adorni MP, Busnelli M, Manzini S, Cipollari E, Favari E, Lorenzon P, Ganzetti GS, Fingerle J, Bernini F, Chiesa G. Infusions of large synthetic HDL containing trimeric apoA-i stabilize atherosclerotic plaques in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35:1400–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potì F, Simoni M, Nofer JR. Atheroprotective role of High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL)-associated Sphingosine-1-Phosphate (S1P). Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:395–404. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soran H, Schofield JD, Durrington PN. Antioxidant properties of HDL. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:222. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Stoep M, Korporaal SJ, Van Eck M. High-density lipoprotein as a modulator of platelet and coagulation responses. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:362–371. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonacina F, Pirillo A, Catapano AL, Norata GD. Cholesterol membrane content has a ubiquitous evolutionary function in immune cell activation: the role of HDL. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2019;30:462–469. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yvan-Charvet L, Bonacina F, Guinamard RR, Norata GD. Immunometabolic function of cholesterol in cardiovascular disease and beyond. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115:1393–1407. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorci-Thomas MG, Thomas MJ. Microdomains, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:679–691. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dansky HM, Charlton SA, Barlow CB, Tamminen M, Smith JD, Frank JS, Breslow JL. Apo A-I inhibits foam cell formation in Apo E-deficient mice after monocyte adherence to endothelium. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:31–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI6577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilhelm AJ, Zabalawi M, Owen JS, Shah D, Grayson JM, Major AS, Bhat S, Gibbs DP, Jr, Thomas MJ, Sorci-Thomas MG. Apolipoprotein A-I modulates regulatory T cells in autoimmune LDLr-/-, ApoA-I-/- mice. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:36158–36169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.134130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilhelm AJ, Zabalawi M, Grayson JM, Weant AE, Major AS, Owen J, Bharadwaj M, Walzem R, Chan L, Oka K, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I and its role in lymphocyte cholesterol homeostasis and autoimmunity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:843–849. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.183442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zabalawi M, Bhat S, Loughlin T, Thomas MJ, Alexander E, Cline M, Bullock B, Willingham M, Sorci-Thomas MG. Induction of fatal inflammation in LDL receptor and ApoA-I double-knockout mice fed dietary fat and cholesterol. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63480-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pászty C, Maeda N, Verstuyft J, Rubin EM. Apolipoprotein AI transgene corrects apolipoprotein E deficiency-induced atherosclerosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:899–903. doi: 10.1172/JCI117412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnaboldi F, Busnelli M, Cornaghi L, Manzini S, Parolini C, Dellera F, Ganzetti GS, Sirtori CR, Donetti E, Chiesa G. High-density lipoprotein deficiency in genetically modified mice deeply affects skin morphology: a structural and ultrastructural study. Exp Cell Res. 2015;338:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchesi M, Parolini C, Caligari S, Gilio D, Manzini S, Busnelli M, Cinquanta P, Camera M, Brambilla M, Sirtori CR, Chiesa G. Rosuvastatin does not affect human apolipoprotein A-I expression in genetically modified mice: a clue to the disputed effect of statins on HDL. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:1460–1468. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01429.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin EM, Ishida BY, Clift SM, Krauss RM. Expression of human apolipoprotein A-I in transgenic mice results in reduced plasma levels of murine apolipoprotein A-I and the appearance of two new high density lipoprotein size subclasses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:434–438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Busnelli M, Manzini S, Jablaoui A, Bruneau A, Kriaa A, Philippe C, et al. Fat-shaped microbiota affects lipid metabolism, liver steatosis, and intestinal homeostasis in mice fed a low-protein diet. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2020:e1900835. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parolini C, Caligari S, Gilio D, Manzini S, Busnelli M, Montagnani M, Locatelli M, Diani E, Giavarini F, Caruso D, et al. Reduced biliary sterol output with no change in total faecal excretion in mice expressing a human apolipoprotein A-I variant. Liver Int. 2012;32:1363–1371. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2012.02855.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.France DS, Hughes TE, Miserendino R, Spirito JA, Babiak J, Eskesen JB, Tapparelli C, Paterniti JR, Jr. Nonimmunochemical quantitation of mammalian apolipoprotein A-I in whole serum or plasma by nonreducing gel electrophoresis. J Lipid Res. 1989;30:1997–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busnelli M, Manzini S, Bonacina F, Soldati S, Barbieri SS, Amadio P, Sandrini L, Arnaboldi F, Donetti E, Laaksonen R, et al. Fenretinide treatment accelerates atherosclerosis development in apoE-deficient mice in spite of beneficial metabolic effects. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:328–345. doi: 10.1111/bph.14869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daugherty A, Tall AR, Daemen MJAP, Falk E, Fisher EA, García-Cardeña G, Lusis AJ, Owens AP, 3rd, Rosenfeld ME, Virmani R; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; and Council on Basic Cardiovascular Sciences. Recommendation on design, execution, and reporting of animal atherosclerosis studies: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:e131–e157. doi: 10.1161/ATV.0000000000000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Busnelli M, Manzini S, Hilvo M, Parolini C, Ganzetti GS, Dellera F, Ekroos K, Jänis M, Escalante-Alcalde D, Sirtori CR, et al. Liver-specific deletion of the Plpp3 gene alters plasma lipid composition and worsens atherosclerosis in apoE-/- mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44503. doi: 10.1038/srep44503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonas A. Reconstitution of high-density lipoproteins. Methods Enzymol. 1986;128:553–582. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)28092-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonacina F, Martini E, Svecla M, Nour J, Cremonesi M, Beretta G, Moregola A, Pellegatta F, Zampoleri V, Catapano AL, et al. Adoptive transfer of CX3CR1 transduced-T regulatory cells improves homing to the atherosclerotic plaques and dampens atherosclerosis progression. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;117:2069–2082. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manzini S, Pinna C, Busnelli M, Cinquanta P, Rigamonti E, Ganzetti GS, Dellera F, Sala A, Calabresi L, Franceschini G, et al. Beta2-adrenergic activity modulates vascular tone regulation in lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase knockout mice. Vascul Pharmacol. 2015;74:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manzini S, Busnelli M, Parolini C, Minoli L, Ossoli A, Brambilla E, Simonelli S, Lekka E, Persidis A, Scanziani E, Chiesa G. Topiramate protects apoE-deficient mice from kidney damage without affecting plasma lipids. Pharmacol Res. 2019;141:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manzini S, Busnelli M, Colombo A, Franchi E, Grossano P, Chiesa G. reString: an open-source python software to perform automatic functional enrichment retrieval, results aggregation and data visualization. Sci Rep. 2021;11:23458. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02528-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plump AS, Scott CJ, Breslow JL. Human apolipoprotein A-I gene expression increases high density lipoprotein and suppresses atherosclerosis in the apolipoprotein E-deficient mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9607–9611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Busnelli M, Manzini S, Chiara M, Colombo A, Fontana F, Oleari R, Potì F, Horner D, Bellosta S, Chiesa G. Aortic gene expression profiles show how ApoA-I levels modulate inflammation, lysosomal activity, and sphingolipid metabolism in murine atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:651–667. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; 2020. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tuzlak S, Dejean AS, Iannacone M, Quintana FJ, Waisman A, Ginhoux F, Korn T, Becher B. Repositioning TH cell polarization from single cytokines to complex help. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:1210–1217. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01009-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lackner KJ, Dieplinger H, Nowicka G, Schmitz G. High density lipoprotein deficiency with xanthomas. A defect in reverse cholesterol transport caused by a point mutation in the apolipoprotein A-I gene. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2262–2273. doi: 10.1172/JCI116830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaefer EJ, Santos RD, Asztalos BF. Marked HDL deficiency and premature coronary heart disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:289–297. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32833c1ef6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valenta DT, Bulgrien JJ, Banka CL, Curtiss LK. Overexpression of human ApoAI transgene provides long-term atheroprotection in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJ, Komajda M, Lopez-Sendon J, Mosca L, Tardif JC, Waters DD, et al. ; ILLUMINATE Investigators. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2109–2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, Francis DP. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braun A, Trigatti BL, Post MJ, Sato K, Simons M, Edelberg JM, Rosenberg RD, Schrenzel M, Krieger M. Loss of SR-BI expression leads to the early onset of occlusive atherosclerotic coronary artery disease, spontaneous myocardial infarctions, severe cardiac dysfunction, and premature death in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2002;90:270–276. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.104462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakashima Y, Plump AS, Raines EW, Breslow JL, Ross R. ApoE-deficient mice develop lesions of all phases of atherosclerosis throughout the arterial tree. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:133–140. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.1.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parolini C, Busnelli M, Ganzetti GS, Dellera F, Manzini S, Scanziani E, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging visualization of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques at the brachiocephalic artery of apolipoprotein E knockout mice by the blood-pool contrast agent B22956/1. Mol Imaging. 2014;13. doi: 10.2310/7290.2014.00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plump AS, Smith JD, Hayek T, Aalto-Setälä K, Walsh A, Verstuyft JG, Rubin EM, Breslow JL. Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell. 1992;71:343–353. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90362-g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Covey SD, Krieger M, Wang W, Penman M, Trigatti BL. Scavenger receptor class B type I-mediated protection against atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-negative mice involves its expression in bone marrow-derived cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1589–1594. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000083343.19940.A0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yesilaltay A, Daniels K, Pal R, Krieger M, Kocher O. Loss of PDZK1 causes coronary artery occlusion and myocardial infarction in Paigen diet-fed apolipoprotein E deficient mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yeo KP, Lim HY, Thiam CH, Azhar SH, Tan C, Tang Y, See WQ, Koh XH, Zhao MH, Phua ML, et al. Efficient aortic lymphatic drainage is necessary for atherosclerosis regression induced by ezetimibe. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabc2697. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc2697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Black LL, Srivastava R, Schoeb TR, Moore RD, Barnes S, Kabarowski JH. Cholesterol-independent suppression of lymphocyte activation, autoimmunity, and glomerulonephritis by apolipoprotein A-I in normocholesterolemic lupus-prone mice. J Immunol. 2015;195:4685–4698. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tavori H, Su YR, Yancey PG, Giunzioni I, Wilhelm AJ, Blakemore JL, Zabalawi M, Linton MF, Sorci-Thomas MG, Fazio S. Macrophage apoAI protects against dyslipidemia-induced dermatitis and atherosclerosis without affecting HDL. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:635–643. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M056408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaul S, Xu H, Zabalawi M, Maruko E, Fulp BE, Bluemn T, Brzoza-Lewis KL, Gerelus M, Weerasekera R, Kallinger R, James R, et al. Lipid-free apolipoprotein A-I reduces progression of atherosclerosis by mobilizing microdomain cholesterol and attenuating the number of CD131 expressing cells: monitoring cholesterol homeostasis using the cellular ester to total cholesterol ratio. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e004401. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bonacina F, Pirillo A, Catapano AL, Norata GD. HDL in immune-inflammatory responses: implications beyond cardiovascular diseases. Cells. 2021;10:1061. doi: 10.3390/cells10051061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Westerterp M, Gautier EL, Ganda A, Molusky MM, Wang W, Fotakis P, Wang N, Randolph GJ, D’Agati VD, Yvan-Charvet L, Tall AR. Cholesterol accumulation in dendritic cells links the inflammasome to acquired immunity. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1294–1304.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ito A, Hong C, Oka K, Salazar JV, Diehl C, Witztum JL, Diaz M, Castrillo A, Bensinger SJ, Chan L, Tontonoz P. Cholesterol accumulation in CD11c+ immune cells is a causal and targetable factor in autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2016;45:1311–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bonacina F, Coe D, Wang G, Longhi MP, Baragetti A, Moregola A, Garlaschelli K, Uboldi P, Pellegatta F, Grigore L, et al. Myeloid apolipoprotein E controls dendritic cell antigen presentation and T cell activation. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3083. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05322-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hartmann B, Staedtler F, Hartmann N, Meingassner J, Firat H. Gene expression profiling of skin and draining lymph nodes of rats affected with cutaneous contact hypersensitivity. Inflamm Res. 2006;55:322–334. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-5141-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ku HO, Jeong SH, Kang HG, Pyo HM, Cho JH, Son SW, Yun SM, Ryu DY. Gene expression profiles and pathways in skin inflammation induced by three different sensitizers and an irritant. Toxicol Lett. 2009;190:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gomaraschi M, Bonacina F, Norata GD. Lysosomal acid lipase: from cellular lipid handler to immunometabolic target. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019;40:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2018.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rigamonti E, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, Staels B. Regulation of macrophage functions by PPAR-alpha, PPAR-gamma, and LXRs in mice and men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1050–1059. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.158998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nomura M, Liu J, Yu ZX, Yamazaki T, Yan Y, Kawagishi H, Rovira II, Liu C, Wolfgang MJ, Mukouyama YS, Finkel T. Macrophage fatty acid oxidation inhibits atherosclerosis progression. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019;127:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Diskin C, Pålsson-McDermott EM. Metabolic modulation in macrophage effector function. Front Immunol. 2018;9:270. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.