Abstract

Background:

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) risk has been associated with pesticide use, but evidence on specific pesticides or other agricultural exposures is lacking. We investigated history of pesticide use and risk of SLE and a related disease, Sjögren’s syndrome (SS), in the Agricultural Health Study.

Methods:

The study sample (N=54,419, 52% male, enrolled in 1993–1997) included licensed pesticide applicators from North Carolina and Iowa and spouses who completed any of the follow-up questionnaires (1999–2003, 2005–2010, 2013–2015). Self-reported cases were confirmed by medical records or medication use (total: 107 incident SLE or SS, 79% female). We examined ever use of 31 pesticides and farm tasks and exposures reported at enrollment in association with SLE/SS, using Cox regression to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), with age as the timescale and adjusting for gender, state, and correlated pesticides.

Results:

In older participants (>62 years), SLE/SS was associated with ever use of the herbicide metribuzin (HR 5.33; 95%CI 2.19, 12.96) and applying pesticides 20+ days per year (2.97; 1.20, 7.33). Inverse associations were seen for petroleum oil/distillates (0.39; 0.18, 0.87) and the insecticide carbaryl (0.56; 0.36, 0.87). SLE/SS was inversely associated with having a childhood farm residence (0.59; 0.39, 0.91), but was not associated with other farm tasks/exposures (except welding (HR 2.65; 95%CI 0.96, 7.35).

Conclusions:

These findings suggest that some agricultural pesticides may be associated with higher or lower risk of SLE/SS. However, the overall risk associated with farming appears complex, involving other factors and childhood exposures.

Keywords: Prospective cohort, occupational, environmental, pesticides, systemic autoimmune diseases, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, Epidemiologic study

1.0. Introduction

Growing evidence indicates a role for environmental factors in autoimmune disease etiology, with the strongest evidence for smoking and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and occupational exposure to respirable silica dust, which has been associated with systemic autoimmune diseases, including RA and a related autoimmune disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [1]. Studies have suggested associations of SLE with occupational exposures to solvents, sun exposure, farming, and pesticide use [2–4], as well as current smoking [5, 6]. In the Agricultural Health Study (AHS), we previously investigated factors associated with incident RA in male pesticide applicators (mostly farmers) and their spouses. We saw positive associations with some specific pesticides and other agricultural tasks and exposures, an inverse association with childhood livestock contact in female spouses, and age-dependent associations in overall analyses of spouses and applicators for raising livestock and crops (versus crops alone) and for hay, alfalfa, or field corn [7–9]. Here we extend this work to evaluate these same risk factors for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and a closely related disease, Sjögren’s syndrome (SS).

In SLE, the immune system targets nuclear self-antigens, impacting multiple systems, including skin, joints, and kidneys. SLE affects nearly 1 in 1000 adults in the U.S. [10–12]. Pesticides have been a suspected cause of SLE based on associations of SLE with farm work or non-specific pesticide use [13–19]). Other agricultural risk factors for SLE may include solvents, metals, sunlight, inorganic (e.g., silica) and organic dusts, livestock, and as well as differences in susceptibility due to the developmental effects of immune modifying exposures for those lived or worked on a farm in childhood [2, 20–22]. In SS, the immune system targets the exocrine glands; SS often co-occurs with SLE and RA (i.e., secondary SS), while incidence of primary SS is similar to that of SLE and may be increasing in the U.S. [23, 24]. Shared risk factors for SLE and SS include a family history of systemic autoimmune disease and a female predominance (at least 90% of cases are female) [23, 25]. Few studies have identified non-infectious environmental risk factors for primary SS, but there is limited evidence for smoking and occupational solvent exposure [26–28]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies of SS in relation to farming or pesticide use. Patients with SLE or SS (and also RA) are at increased risk of hematologic cancers, which may share etiologic pathways involving dysregulated innate and adaptive immunity, as well as common risk factors, including genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures such as pesticides [29–32].

Given clinical overlap and shared features of these two systemic autoimmune diseases, there may be shared environmental risk factors [33]. Thus, we examined associations with developing incident SLE or SS in relation to pesticide use, crops, and other agricultural exposures in private pesticide applicators and spouses.

2.0. Methods

2.1. Study Sample

The AHS is a prospective cohort including 52,394 licensed private pesticide applicators and 32,345 spouses who enrolled in 1993–1997 [34]. Questionnaires at enrollment and 3 follow-up surveys (1999–2003, 2005–2010, and 2013–2015) collected data on demographics, lifetime pesticide use, and medical history (https://aghealth.nih.gov/collaboration/questionnaires.html). The study was approved by relevant institutional review boards.

Participants were eligible for the current study sample if they had questionnaire data on lupus at enrollment and lupus or SS on one or more of the follow-up surveys (below). Sample derivation is shown in Supplemental Figure 1; 25,226 participants did not complete the relevant questionnaires and 501 completed the questionnaires but were missing responses on lupus or SS. We also excluded potential cases with inconsistent self-reporting (i.e., reporting a diagnosis in an earlier survey, but not affirming the same diagnosis in a later survey; 90 lupus or SS, and 637 RA), or some prevalent cases who were administratively censored from case confirmation (796 female RA cases.

2.2. Case Ascertainment

Applicators who completed a take-home questionnaire (44% of those enrolled) and spouses were asked whether they had ever been diagnosed with RA or lupus. In the first follow-up (1999–2003), only spouses were asked about being diagnosed with one or more of three systemic autoimmune diseases: RA, lupus, and SS. In the second and third follow-up questionnaire (2005–10 and 2013–15), both applicators and spouses were asked about RA, lupus, and SS. Potential cases with incident SLE or SS diagnoses reported in one or more follow-up questionnaire were evaluated following the same protocol as previously described for RA [7, 8]. Self-reported cases in the first two follow-up periods were re-contacted by telephone or mailed a short questionnaire to collect confirmatory data, ask about diagnosis age, type of lupus (SLE only, cutaneous, other), diagnosis or treatment by a rheumatologist or other specialist, and use of disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and other medications used for SLE or SS (e.g., Cytoxan, pilocarpine). In the third follow-up questionnaire, self-reported cases were asked about these same medications and also recontacted to confirm their diagnosis and type (i.e., SLE). Affirmed cases were asked for consent to contact their physicians for validation by a checklist completed by clinicians or abstracted from medical records.

Of 57,489 potentially AHS eligible participants, there were 385 self-reported lupus or SS. Of these, 164 were excluded for various reasons: 42 could not be contacted, were deceased, or declined participation, 3 refuted their diagnosis, 37 identified as “cutaneous” or “other” type of lupus, 62 lacked information on medication use, and 20 who were missing diagnosis age so incidence could not be determined. Classification of the remaining 221 affirmed cases was based on a consensus review of all available data by two of the study investigators. In those with medical records data, SLE/SS was refuted for 7 cases and confirmed for 75. The remaining 139 (without medical records) were considered clinical cases based on medication use, for a total of 214 confirmed or clinical cases (107 incident). For those with multiple diagnoses, we prioritized incident SLE (i.e., cases with RA and later SLE would be considered incident RA-SLE), and when SS was secondary to RA or SLE, the primary diagnosis determined prevalence or incidence. The primary analysis sample included 54,205 non-cases and 107 incident cases. A sensitivity analysis of organochlorines, 2,4,5-T, and 2,4,5-TP was conducted on the sample of 107 prevalent cases and all 226 confirmed or clinical SLE/SS cases also including 23 for whom incidence could not be determined (3 deceased and 20 missing diagnosis age).

2.3. Exposure and covariate data

At enrollment, participants were asked whether, in their lifetime they had ever personally mixed or applied any pesticides, followed by a checklist on ever-use of 50 specific types. The applicator take-home and spouse questionnaires also asked about years personally mixed or applied any pesticides, and during those years about how many days per year. At enrollment, applicators were asked about income producing crops or animals they were currently raising (and the number raised); data used for this study included livestock (not including poultry, which had too few cases) and field crops related to livestock farming and grains (i.e., alfalfa, field corn, hay, oats, sweet corn, wheat). Since spouses were not asked about crops or livestock, data reported by the applicators was used determine spouse exposures.

The applicator take-home and spouse enrollment questionnaires asked several questions about experiences on a farm, including childhood farm residence (“Before age 18, did you live at least half of your life on a farm?”), tasks in the last growing season (e.g., tilling, planting), and other tasks such as grinding feed and repairing engines. Participants were also asked about hours per week generally spent in the sun during the growing season. In the second follow-up (2005–2010), participants were asked about childhood livestock contact (“As a child, how much time did you spend around farm animals?” Response options (never, less than once per month, monthly, weekly, daily) were dichotomized for analyses as none or monthly versus weekly or daily.

Sociodemographic data collected at enrollment included age, state (Iowa or NC), gender, race/ethnicity (categorized here as white and other), education (categorized here as ≤ high school and >high school), smoking history (never, past, and current), weight and height for calculated body mass index (BMI; <25, 25-<30, and ≥30).

2.4. Analysis

We examined sample characteristics and then evaluated associations of pesticides and other exposures with incident SLE/SS using Cox regression to calculate hazards ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), with age as the time scale, adjusted for gender and state. We stratified by median attained age (62 years) when the assumption of proportionality was not met (p<0.10). We also ran models limited to females only.

We examined 31 specific pesticides with at least 5 exposed cases. Potential confounding by correlated pesticides (rho >0.40) was evaluated by determining whether their inclusion in models yielded >10% change in the HR (Supplemental Table 2). Models for tasks, UV exposure, and general pesticide use were limited to those with available data, with smaller numbers for variables based on the take-home questionnaire and first follow-up. Associations with HRs >1.50 or <0.67 are reported in the text, and are highlighted in the abstract if CIs excluded the null (1.0).

Because of their lasting presence in the body or environment and/or prior evidence in relation to SLE or in animal models [35], we also explored associations of SLE/SS with organochlorine insecticides (those with 5 or more exposed cases) and two herbicides (i.e., 2,4,5-T and 2,4,5-TP), among prevalent cases and in a combined sample including all cases (including incident and unclassifiable cases), using logistic regression to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95%CI, adjusting for age, sex, and state.

Analyses were conducted using AHS data files releases: P1REL201701.00, P2REL201701.00, P3REL201809.00, and AHSREL201706.00, in SAS, version 9.4 (Cary, NC, U.S.).

3.0. Results

3.1. Descriptive analyses

Characteristics of cases and non-cases are shown in Table 1; of the cases, 84 (79%) were female. Median time to diagnosis was 11 years in males and 9 in females, and female cases were younger at diagnosis than males (55.9 vs. 61.3 years; Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics: incident SLE/SS in the Agricultural Health Study

| Non-cases | Incident SLE/SS | |

|---|---|---|

| (N=54,205) | (N=107) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | |

|

| ||

| Enrollment age | ||

| < 40 | 16,538 (31) | 27 (25) |

| 40–49 | 16,300 (30) | 31 (29) |

| 50–59 | 12,751 (24) | 35 (33) |

| 60+ | 8,616 (16) | 14 (13) |

| State | ||

| NC | 17,365 (32) | 38 (36) |

| IA | 36,840 (68) | 69 (64) |

| Gender1 | ||

| Male | 27,956 (52) | 23 (22) |

| Female | 26,249 (48) | 84 (79) |

| Race/ethnicity2 | ||

| White | 51,866 (97) | 103 (97) |

| Other | 1,362 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Missing | 977 | 1 |

| Education | ||

| ≤High school | 24,692 (50) | 45 (46) |

| >High school | 25,186 (51) | 52 (54) |

| Missing | 4327 | 10 |

| Smoking | ||

| Never | 34372 (64) | 65 (61) |

| Past | 13,195 (25) | 28 (26) |

| Current | 6,172 (11) | 13 (12) |

| Missing | 466 | 1 |

| Body Mass Index | ||

| <25 | 18,579 (37) | 44 (46) |

| 25–<30 | 21,041 (42) | 27 (28) |

| ≥30 | 10,284 (21) | 24 (25) |

| Missing | 4301 | 12 |

Most females were spouses: 878 (3%) female non-cases and 4 cases (5%) were applicators.

Other race/ethnicity included 666 African American non-cases and 0 cases.

3.2. Pesticides

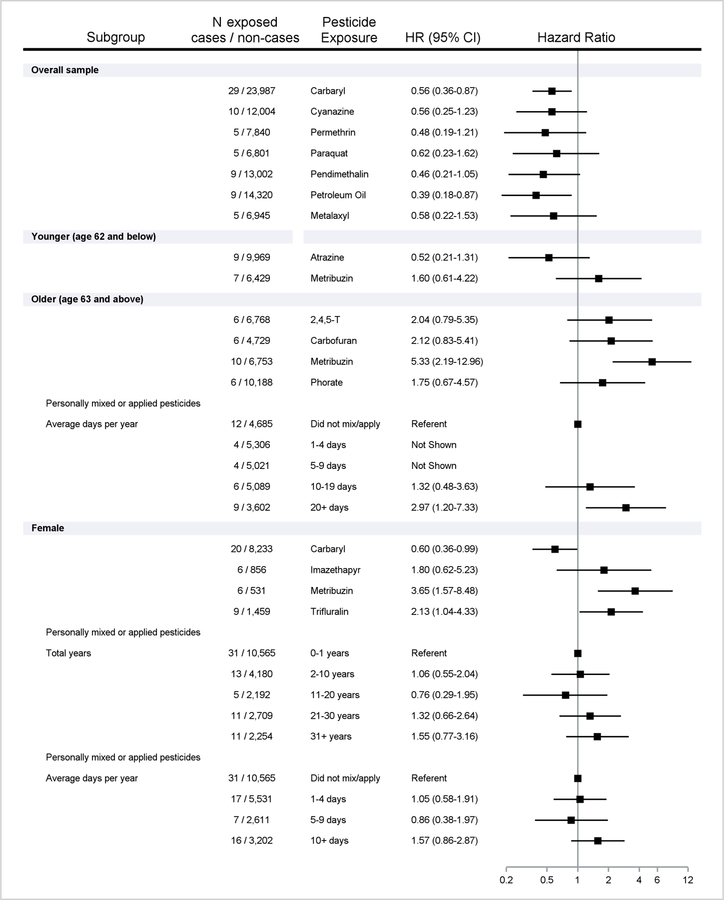

Frequencies for all pesticides in relation to SLE/SS, and adjusted HR and 95%CIs, are shown in Table 2, and potential positive and inverse associations described in Figure 1. Overall, inverse associations were seen for 2 insecticides (carbaryl, permethrin), 4 herbicides (cyanaine, paraquat, pendimethalin, petroleum oil), and 1 fungicide (metalaxyl), with CIs<1.0 for carbaryl and petroleum oil. Age-stratification (because of failure to meet the proportional hazards assumption) was required for 2 insecticides (carbofuran, phorate) and 3 herbicides (atrazine, metribuzin, 2,4,5-T): at younger ages (≤62 years), SLE/SS was inversely associated with one herbicide (atrazine) and positively associated with another (metribuzin), while at older ages positive associations were seen for 2 insecticides (carbofuran and phorate) and 2 herbicides (metribuzin and 2,4,5-TP), with CIs>1.0 for metribuzin. In older participants, SLE/SS was also associated with mixing or applying pesticides 20+ days per year versus no use. In females, models confirmed associations with carbaryl and metribuzin, with positive associations seen for additional 2 herbicides (imazethapyr and trifluralin), and personally mixing/applying pesticides for a long duration (at least 31 years or 10 days per year. Findings for specific pesticides were generally consistent in analyses of males only (carbaryl, pendimethalin, petroleum oil, phorate, metribuzin) and females with a childhood farm history (carbaryl, trifluralin)(Supplemental Table 3).

Table 2.

Ever use of specific pesticides and overall pesticide use in relation to incident SLE/SS

| Overall sample | Females only | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Non-case | Case | Non-case | ||||

| N=107 | N=54,205 | N=84 | N=26,249 | ||||

| Specific pesticides1 | N (%) | N (%) | HR (95%CI)2 | N (%) | N (%) | HR (95% CI)2 | |

|

| |||||||

| Herbicides | |||||||

| Alachlor | 18 (19) | 15,465 (31) | 0.98 (0.49, 1.93) | 7 (9) | 1,156 (5) | 1.05 (0.38, 2.88) | |

| Atrazine | 21 (20) | 20,694 (38) | NS | 5 (6) | 1,310 (5) | 1.13 (0.46, 2.82) | |

| ≤62 years | 9 (14) | 9,969 (38) | 0.52 (0.21, 1.31) | ||||

| >62 years | 12 (32) | 10,725 (44) | 1.43 (0.58, 3.51) | ||||

| Butylate | 10 (10) | 9,560 (19) | 0.82 (0.36, 1.87) | ||||

| Cyanazine | 10 (10) | 12,004 (24) | 0.56 (0.25, 1.23) | ||||

| Dicamba | 14 (14) | 14,967 (30) | 0.99 (0.49, 1.98) | 6 (8) | 1,071 (4) | 1.06 (0.38, 2.97) | |

| Glyphosate | 46 (44) | 30,116 (57) | 0.94 (0.62, 1.42) | 30 (37) | 9,042 (36) | 1.01 (0.64. 1.59) | |

| Imazethapyr | 13 (13) | 12,366 (25) | 1.04 (0.47, 2.26) | 6 (8) | 856 (3) | 1.80 (0.62, 5.23) | |

| Paraquat | 5 (5) | 6,801 (13) | 0.62 (0.23, 1.62) | ||||

| Pendimethalin | 9 (9) | 13,002 (26) | 0.46 (0.21, 1.05) | ||||

| Petroleum Oil | 9 (9) | 14320 (28) | 0.39 (0.18, 0.87) | ||||

| Metolachlor | 12 (12) | 13,320 (26) | 0.86 (0.42, 1.73) | ||||

| Metribuzin | 17 (16) | 13,182 (24) | NS | 6 (8) | 531 (2) | 3.65 (1.57, 8.48) | |

| ≤62 years | 7 (11) | 6,429 (25) | 1.60 (0.61, 4.22) | ||||

| >62 years | 10 (28) | 6,753 (29) | 5.33 (2.19, 12.96) | ||||

| Terbufos | 10 (10) | 11,361 (23) | 0.91 (0.43, 1.94) | ||||

| Trifluralin | 20 (20) | 15,298 (31) | 1.25 (0.61, 2.54) | 9 (11) | 1,459 (6) | 2.13 (1.04, 4.33) | |

| 2,4-D | 31 (30) | 25,332 (49) | 1.01 (0.60, 1.70) | 15 (19) | 3,963 (16) | 1.24 (0.70 2.20) | |

| 2,4,5-T | 8 (8) | 6,768 (12) | NS | ||||

| ≤62 years | 2 (3) | 1,917 (7) | NS | ||||

| >62 years | 6 (16) | 4,851 (20) | 2.04 (0.79, 5.35) | ||||

| Insecticides | |||||||

| Aldrin | 5 (5) | 5,805 (11) | 0.91 (0.34, 2.45) | ||||

| Carbaryl | 29 (28) | 23,987 (46) | 0.56 (0.36, 0.87) | 20 (24) | 8,233 (33) | 0.60 (0.36, 0.99) | |

| Carbofuran | 9 (9) | 7945 (15) | NS | ||||

| ≤62 years | 3 (3) | 3,216 (12) | NS | ||||

| >62 years | 6 (17) | 4,729 (20) | 2.12 (0.83, 5.41) | ||||

| Chlorpyrifos | 14 (14) | 12,969 (25) | 1.10 (0.58, 2.07) | ||||

| Chlordane | 10 (10) | 8,565 (17) | 0.93 (0.47, 1.88) | ||||

| DDT | 10 (10) | 8,118 (16) | 1.02 (0.49, 2.09) | 5 (6) | 931 (4) | 1.48 (0.59, 3.72) | |

| Diazinon | 13 (13) | 11,930 (23) | 0.95 (0.49, 1.85) | 9 (11) | 2,868 (12) | 0.87 (0.43, 1.75) | |

| Lindane | 6 (6) | 6,503 (13) | 0.93 (0.39, 2.24) | ||||

| Malathion | 34 (33) | 25,316 (49) | 0.99 (0.62, 1.57) | 18 (22) | 5,302 (21) | 0.98 (0.58, 1.66) | |

| Parathion | 5 (5) | 4,611 (9) | 1.10 (0.42, 2.86) | ||||

| Permethrin | 5 (5) | 7,840 (15) | 0.48 (0.19, 1.21) | ||||

| Phorate | 8 (8) | 10,188 (19) | NS | ||||

| ≤62 years | 2 (2) | 4,454 (17) | NS | ||||

| >62 years | 6 (17) | 5,734 (23) | 1.75 (0.67, 4.57) | ||||

| Terbufos | 10 (10) | 11,361 (23) | 0.92 (0.43, 1.94) | ||||

| Toxaphene | 5 (5) | 4,263 (8) | 1.18 (0.45, 3.12) | ||||

| Fumigants/fungicides | |||||||

| Methylbromide | 5 (5) | 4,556 (9) | 0.88 (0.33, 2.32) | ||||

| Metalaxyl | 5 (5) | 6,945 (13) | 0.58 (0.22, 1.53) | ||||

| N=93 | N=48,483 | N=71 | N=21,900 | ||||

| Any pesticide use 3 | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Total years | |||||||

| ≤ 1 | 31 (33) | 10,702 (22) | Referent | 31 (44) | 10,565 (48) | Referent | |

| 2–10 | 23 (25) | 13,193 (27) | 1.00 (0.58, 1.74) | 13 (18) | 4,180 (13) | 1.06 (0.55, 2.04) | |

| 11–20 | 20 (22) | 11,807 (24) | 1.50 (0.82, 2.74) | 5 (7) | 2,192 (10) | 0.76 (0.29, 1.95) | |

| 21–30 | 13 (14) | 8,323 (17) | 1.34 (0.65, 2.78) | 11 (15) | 2,709 (12) | 1.32 (0.66, 2.64) | |

| >30 | 6 (6) | 4,458 (9) | 0.91 (0.35, 2.35) | 11 (15) | 2,254 (10) | 1.55 (0.77. 3.16) | |

| Days per year (≤62 years of age) | Overall (females) | ||||||

| 0 | 19 (33) | 6,121 (25) | Referent | 0 | 31 (44) | 10,565 (48) | Referent |

| 1–4 | 17 (30) | 4,903 (20) | 1.40 (0.72, 2.72) | 1–4 | 17 (24) | 5,531 (25) | 1.05 (0.58, 1.91) |

| 5–9 | 6 (11) | 3,953 (16) | 0.83 (0.33, 2.12) | 5–9 | 7 (10) | 2,611 (12) | 0.86 (0.38, 1.97) |

| 10–19 | 10 (18) | 5,090 (21) | 1.43 (0.64, 3.22) | 10+ | 16 (23) | 3,202 (15) | 1.57 (0.86, 2.87) |

| 20+ | 5 (9) | 4,685 (19) | 0.92 (0.33, 2.60) | ||||

| Average days per year (>62 years of age) | |||||||

| 0 | 12 (34) | 4,581 (19) | Referent | ||||

| 1–4 | 4 (11) | 5,306 (22) | NS | ||||

| 5–9 | 4 (11) | 5,021 (21) | NS | ||||

| 10–19 | 6 (17) | 5,089 (22) | 1.32 (0.48, 3.63) | ||||

| 20+ | 9 (26) | 3,602 (15) | 2.97 (1.20, 7.33) | ||||

| Total lifetime days | |||||||

| 0–7 | 31 (34) | 10,702 (22) | Referent | 0 | 31 (44) | 10,565 (48) | Referent |

| 8–64 | 25 (27) | 13,510 (28) | 1.01 (0.59, 1.73) | 1–20 | 11 (15) | 3,941 (18) | 0.97 (0.48, 1.93) |

| 65–236 | 19 (21) | 11,821 (25) | 1.41 (0.77, 2.61) | 21–105 | 11 (15) | 3,397 (16) | 1.07 (0.54, 2.14) |

| 237+ | 17 (18) | 12,189 (25) | 1.37 (0.69, 2.69) | 106+ | 18 (25) | 3,935 (18) | 1.44 (0.80, 2.58) |

Limited to pesticides with at least 5 exposed cases.

Cox proportional hazard models used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) with age as the time scale; models included gender (overall), state, and correlated pesticides (Supplemental Table 2); stratified by median attained age (62 years) and overall HRs are not shown (NS) when proportional hazards assumption not met or for strata with fewer than 5 exposed cases.

Missing on 11% of non-cases and 13% of cases, primarily due to non-response in 15% of spouses.

Figure 1.

Ever use of specific pesticides and overall pesticide use associated with incident SLE/SS. Includes number cases/non-cases exposed, with adjusted Hazard Ratios (HR) and 95%Confidence Intervals (CI). Results shown for positive (HR > 1.5) and inverse associations (HR <0.67), overall or stratified by median attained age (62 years) when the proportional hazards assumption was violated (interaction p<0.10), and in females only.

3.3. Other exposures

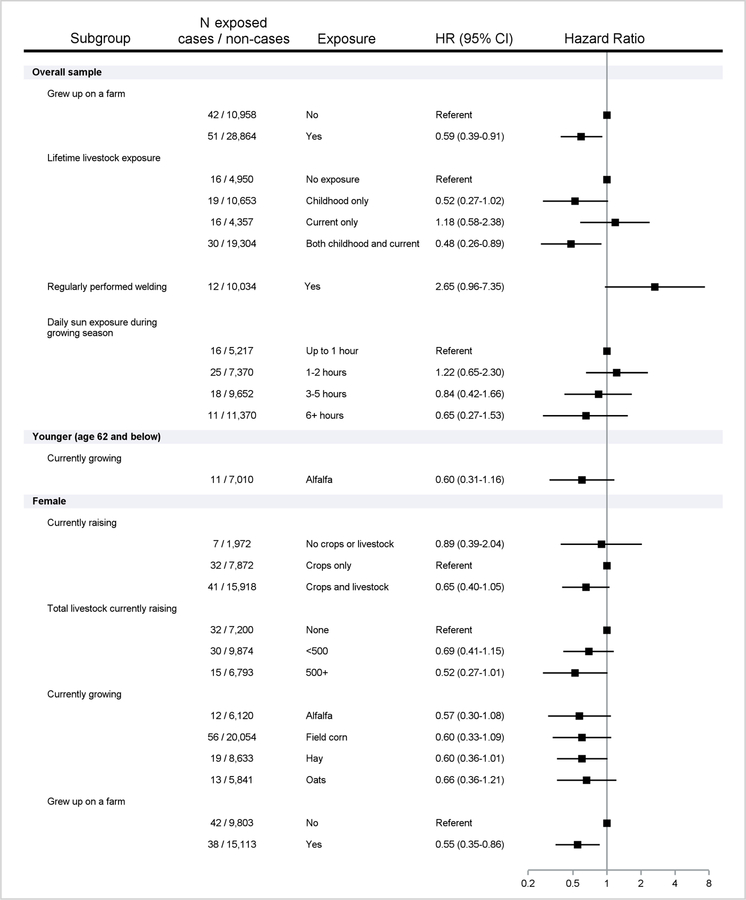

Overall, SLE/SS was inversely associated with having a childhood farm residence, and livestock contact in childhood only or together with raising livestock at enrollment (Table 3; Figure 2). In younger participants, SLE/SS was inversely associated with currently raising alfalfa and hay. In females, SLE/SS was inversely associated with raising livestock and crops (versus crops alone), raising livestock (500+ versus none), alfalfa, field corn, hay, and oats, and with childhood farm residence. SLE/SS was not associated with most regular tasks reported at enrollment (Table 4), except for welding (HR 2.65), and was inversely associated with more sun exposure during the growing season (HR 0.57 for >6 vs. ≤ 2 hours per day).

Table 3.

Crops/livestock raised, childhood farm residence, livestock contact in relation to incident SLE/SS

| Overall | Females only | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Non-case | Case | Non-case | |||

| N=107 | N=54,205 | N=84 | N=26,249 | |||

| N (%) | N (%) | HR (95% CI)2 | N (%) | N (%) | HR (95% CI)2 | |

|

| ||||||

| At enrollment1: Currently raising | ||||||

| Crops only | 39 (36) | 16,451 (30) | Referent | 32 (38) | 7,872 (30) | Referent |

| Crops & Livestock | 56 (52) | 32,628 (60) | 0.74 (0.49, 1.14) | 41 (49) | 15,918 (61) | 0.65 (0.40, 1.05) |

| No crops/livestock | 8 (7) | 4,081 (8) | 0.83 (0.38, 1.81) | 7 (8) | 1,972 (8) | 0.89 (0.39, 2.04) |

| Livestock on farm last year | ||||||

| None | 36 (37) | 14,942 (30) | Referent | 32 (42) | 7,200 (30) | Referent |

| <500 | 41 (42) | 20,653 (42) | 0.84 (0.53, 1.32) | 30 (39) | 9,874 (41) | 0.69 (0.41, 1.15) |

| 500+ | 21 (21) | 13,565 (28) | 0.67 (0.38, 1.19) | 15 (19) | 6,793 (28) | 0.52 (0.27, 1.01) |

| Type of livestock | ||||||

| Beef | 41 (38) | 21,478 (40) | 0.97 (0.65, 1.44) | 30 (36) | 10,396 (40) | 0.88 (0.56, 1.38) |

| Hogs | 5 (5) | 3,403 (6) | 0.76 (0.48, 1.20) | |||

| Dairy | 30 (28) | 18,856 (35) | 0.76 (0.31, 1.87) | 21 (25) | 9,288 (35) | 0.77 (0.28, 2.10) |

| Livestock-related field crops and grains | ||||||

| Alfalfa | 18 (17) | 12,578 (23) | NS | 12 (14) | 6,120 (23) | 0.57 (0.30, 1.08) |

| ≤62 years | 11 (16) | 7,010 (25) | 0.60 (0.31, 1.16) | |||

| >62 years | 7 (18) | 5,568 (21) | 0.88 (0.38, 2.03) | |||

| Field corn | 76 (71) | 41,121 (76) | 0.80 (0.46, 1.37) | 56 (67) | 20,054 (76) | 0.60 (0.33, 1.09) |

| Hay | 28 (26) | 17,949 (33) | NS | 19 (23) | 8,633 (33) | 0.60 (0.36, 1.01) |

| ≤62 years | 15 (22) | 9,332 (34) | 0.56 (0.32, 1.00) | |||

| >62 years | 13 (33) | 8,617 (32) | 1.07 (0.55, 2.09) | |||

| Oats | 20 (19) | 12,093 (22) | 0.82 (0.50, 1.4) | 13 (15) | 5841 (22) | 0.66 (0.36, 1.20) |

| Sweet corn | 7 (7) | 4355 (8) | 0.80 (0.37, 1.7) | |||

| Wheat | 10 (9) | 5327 (10) | 0.86 (0.43, 1.7) | 8 (10) | 2510 (10) | 0.83 (0.38, 1.81) |

| N=93 | N=39,822 | N=80 | N=24,916 | |||

| Grew up on farm3 | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| No | 42 (45) | 10,958 (28) | Referent | 42 (52) | 9,803 (39) | Referent |

| Yes | 51 (55) | 28,864 (72) | 0.59 (0.39, 0.91) | 38 (48) | 15,113 (61) | 0.55 (0.35, 0.86) |

| N=81 | N=39,264 | N=64 | N=17,841 | |||

| Livestock4 | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| None | 16 (19) | 4,950 (13) | Referent | 15 (23) | 3,526 (20) | Referent |

| Childhood Only | 19 (23) | 10,653 (27) | 0.52 (0.52, 1.02) | 14 (22) | 4,025 (23) | 0.80 (0.38, 1.65) |

| Adult Only | 16 (20) | 4,357 (11) | 1.18 (0.58, 2.38) | 15 (23) | 3,656 (20) | 1.01 (0.49, 2.08) |

| Childhood & Adult | 30 (37) | 19,304 (49) | 0.48 (0.26, 0.89) | 20 (31) | 6,634 (37) | 0.73 (0.37, 1.43) |

Crops reported by private applicator (for spouse as well). Does not show exposures with fewer than 5 exposed cases: 1045 (2%) non-cases and 4 cases (4%) reported raising animals only. Number of livestock raised last year missing for 5045 (9%) non-cases and 9 (8%) of cases

Cox proportional hazard models used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) with age as the time scale; models included gender (overall) and state; stratified by median attained age (62 years) and overall HRs are not shown (NS) when proportional hazards assumption not met.

Question was asked of all spouses and on the applicator take-home questionnaire.

Question asked on second follow-up survey on childhood livestock contact, combined with currently raising livestock as an adult at enrollment.

Figure 2.

Crops/livestock raised, childhood farm residence/livestock contact, and welding associated with incident SLE/SS. Includes number of cases/non-cases exposed, with adjusted Hazard Ratios (HR) and 95%Confidence Intervals (CI). Results shown for positive (HR > 1.5) and inverse associations (HR <0.67), overall or stratified by median attained age (62 years) when the proportional hazards assumption was violated (interaction p<0.10), and in females only.

Table 4.

Regular farm tasks, field work, and sun exposure at enrollment in relation to incident SLE/SS

| Overall | Females only | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Non-cases | Cases | Non-cases | |||

| N=96 | N=40824 | N=83 | N=25786 | |||

| N (%) | N (%) | HR (95% CI)2 | N (%) | N (%) | HR (95% CI)2 | |

|

| ||||||

| Regular tasks 1 | ||||||

| Drive trucks | 41 (45) | 19629 (50) | 1.10 (0.72, 1.69) | 33 (42) | 9561 (39) | 1.12 (0.71, 1.75) |

| Use a diesel tractor | 34 (37) | 22083 (56) | 0.79 (0.49, 1.27) | 24 (30) | 8287 (34) | 0.85 (0.52, 1.39) |

| Use a gas tractor | 32 (35) | 16965 (44) | 1.14 (0.72, 1.81) | 22 (28) | 6376 (26) | 1.08 (0.65, 1.77) |

| Welding | 12(13) | 10034 (26) | 2.65 (0.96, 7.35) | |||

| Repairing engines | 5 (5) | 6665 (17) | 0.73 (0.26, 2.05) | |||

| Grind metal | 10 (11) | 10715 (28) | 1.22 (0.43, 3.45) | |||

| Grind animal feed | 10 (11) | 7833 (20) | 1.09 (0.53, 2.27) | 5 (6) | 1417 (6) | 1.16 (0.47, 2.90) |

| Clean with gasoline | 18 (20) | 9462 (24) | 1.15 (0.67, 1.96) | 13 (17) | 3661 (15) | 1.19 (0.65, 2.18) |

| Clean with other solvents | 17 (19) | 8658 (22) | 0.90 (0.54, 1.53) | 13 (17) | 4792 (20) | 0.83 (0.46, 1.52) |

| Painting | 31 (34) | 13658 (35) | 1.06 (0.68, 1.65) | 27 (34) | 7684 (32) | 1.15 (0.72, 1.85) |

| Veterinary procedures | 15 (16) | 9200 (24) | 1.04 (0.58, 1.86) | 9 (11) | 3144 (13) | 0.91 (0.45, 1.86) |

| Field work 1 | ||||||

| Tilling soil | 32 (34) | 21092 (53) | 0.93 (0.56, 1.54) | 20 (24) | 6390 (26) | 0.94 (0.56, 1.56) |

| Planting | 37 (39) | 20856 (53) | 1.25 (0.76, 2.04) | 25 (30) | 6201 (25) | 1.20 (0.73, 1.96) |

| Apply natural fertilizer | 26 (28) | 17710 (45) | 1.27 (0.71, 2.26) | 14 (17) | 3233 (13) | 1.24 (0.69, 2.21) |

| Apply chemical fertilizer | 23 (25) | 17622 (45) | 1.03 (0.54, 1.96) | 11(14) | 3063 (12) | 0.98 (0.51, 1.89) |

| Machine harvest crops | 21 (22) | 17574 (45) | 0.88 (0.44, 1.76) | 10 (12) | 3053 (12) | 1.00 (0.51, 1.94) |

| Hand harvest crops | 33 (35) | 21042 (54) | 0.88 (0.53, 1.46) | 22 (27) | 6577 (27) | 0.90 (0.54, 1.49) |

| N=70 | N=33,609 | N=58 | N=18,800 | |||

| Daily sun exposure 1.3 | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| ≤2 hours | 41 (59) | 12,587 (37) | Referent | 38 (65) | 11,012(59) | Referent |

| 3–5 hours | 18 (26) | 9652 (29) | 0.74 (0.27, 1.31) | 14 (24) | 5395 (29) | 0.75 (0.41, 1.40) |

| 6+ hours | 11 (16) | 11370 (34) | 0.57 (0.27, 1.22) | 6 (10) | 2393 (13) | 0.72 (0.30, 1.70) |

Questions asked of all spouses and on the applicator take-home questionnaire; Regular tasks were at least once per month (during the growing season or not in the growing season), while field work and daily sun exposure were asked for the growing season; not shown for exposures with fewer than 5 cases.

Cox proportional hazard models used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) with age as the time scale, models include gender (overall) and state.

Missing 16% of non-cases and 25% of cases, primarily due to spouses’ non-response: 25% non-cases, 31% cases.

3.4. Supplemental analyses

We explored associations of organochlorines and herbicides 2,4,5-T and 2,4,5-TP with prevalent and overall SLE/SS (Supplemental Table 4). Prevalent SLE/SS was significantly associated with 2,4,5-TP (Odds Ratio, OR 3.62; 95% CI 1.32, 9.97) and DDT (OR 2.22; 1.16, 4.24), and a positive albeit non-statistically significant OR for 2,4,5-T. However, these associations were attenuated when all other (incident and indeterminant) cases were included.

4.0. Discussion

Our findings provide novel evidence on associations of pesticides and other agricultural risk factors for SLE and SS. Using prospective data from a large cohort of licensed private pesticide applicators and their spouses, we noted 6 positive and 8 inverse associations for pesticides (out of 31 examined), as well as an inverse association with childhood farm residence. These results support the idea that certain pesticides may impact risk of SS/SLE, but also suggest a complex picture including other risk and protective factors in the agricultural environment.

4.1. Specific pesticides

Herbicides:

We saw a strong positive association of SLE/SS with the herbicide metribuzin in older adults and in females, consistent with prior AHS evidence of potential immune effects based on findings for lymphohematopoetic cancers [36]. Despite potential effects on the liver and thyroid, metribuzin is considered non-hazardous to humans and immunotoxicity has not been described [37–39]. The elevated HR for 2,4,5-T seen in older participants is notable, given potential for immune effects due to contamination with dioxin during production [40, 41]. The related herbicide 2,4,5-TP, shares this potential [35], but was used by fewer than 5 incident cases; an association of prevalent SLE and 2,4,5-TP was seen in a supplemental analysis, but was attenuated when all cases were included in the model. Considered a xenoestrogen, dioxin attenuated disease in a female lupus mouse model, but exacerbated the effects of prenatal exposure in another experimental study [42, 43]. Dioxin has a strong affinity for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, which may also play a role in SLE [44–48]. The inverse association with petroleum oil/distillates contrasts prior findings in a sub-study of 668 male AHS applicators showing a positive association of petroleum oil/distillates with antinuclear antibodies (ANA), a potential intermediate marker in the development of SLE [2, 49].

Insecticides:

The widely used insecticide carbaryl was inversely associated with SLE/SS, contrasting prior positive associations with RA in male applicators [7] and follicular B-cell lymphoma [31]. Interestingly, carbaryl may suppress humoral immunity [50, 51], while carbofuran, which showed an elevated albeit non-statistically significant HR in older participants, may decrease T-cell mediated immunity [52]. Carbofuran was used by almost all participants with disease-associated ANA in AHS applicators [49]. We saw limited evidence of associations between organochlorine insecticides with incident SLE/SS, except for a positive association with DDT use in prevalent (and overall) cases. Experimental findings suggest organochlorines might increase disease risk and activity of female lupus-prone mice [42, 53, 54]. In previous AHS analyses, DDT was associated with RA in female spouses [8]; but in male applicators, DDT was not associated with RA [7], and was inversely associated with ANA [49]. Sex-specific effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals such as DDT may be influenced by dose, timing, and other contextual factors [55].

4.2. Other farming exposures

SLE/SS cases were less likely to grow-up on a farm and have childhood livestock contact, though the later association was less apparent in females. In female spouses, we previously noted an inverse association of RA with childhood livestock exposure but not with childhood farm residence [8]. SLE was inversely associated with childhood livestock exposure in a population-based case-control study in North Carolina, while another nested case-cohort analysis showed a positive association of SLE with having an early childhood farm residence [20, 22]. In younger participants, SLE/SS was also inversely associated with raising alfalfa or hay at enrollment, similar to our prior findings for RA for hay [9]. Raising livestock and handling feed or grains confers elevated exposures to endotoxins, organic dusts and microbial factors, with inflammatory and immune modulating effects that may impact the development of autoimmune disease [56, 57]. Livestock contact is only one of many potential exposures among children growing up on a farm, including very early life experiences that may influence the development of the infant microbiome and later immune-related conditions such as asthma [58]. A nested case-control study of adult asthma in the AHS also suggests timing may be critical, as several maternal farming activities were associated with reduced atopy (based on specific IgE-levels), while childhood animal exposures alone were not associated in the absence of in utero exposure [59]. Taken together, our findings argue for further examination of early life agricultural exposures in relation to systemic autoimmunity and adult diseases.

Frequent pesticide use was associated with SLE/SS in older applicators and could indicate potential for greater use of different types of pesticides or other unmeasured characteristics. However, SLE/SS was not associated with different types of field work and other tasks or exposures, except welding, which was also associated with RA [9] and is supported by evidence on immune effects of metal fumes [60, 61]. Solvent use was not associated with SLE/SS, contrasting findings for RA in spouses [8, 9] and a retrospective study of SS [27].

Population-based studies have suggested occupational sun exposure may be associated with SLE [19, 21], but we observed an inverse association at higher levels of daily sun exposure during the growing season at enrollment, similar to our prior findings for RA in female spouses [8].

Immune effects of sun exposure may include direct triggering effects on cutaneous symptoms or indirect pathways such as vitamin D level, yielding differences in associations depending on the duration, intensity, and timing of exposure [62]. Given that UV exposure has appeared protective for other autoimmune diseases in other populations [62, 63], further investigation of sun exposure is warranted in SLE/SS.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

Self-reported SLE is sensitive but non-specific; therefore, we confirmed cases based on medical records or reported use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, which increases specificity [64]. We identified no studies on the accuracy of self-reported SS. Case ascertainment was incomplete due to loss to follow-up and non-response to disease confirmation efforts. We ascertained three related autoimmune diseases; most had SLE (39% SLE, 12% SLE with RA, 6% SLE with SS, and 2% with all 3), while the remainder were primary or secondary SS (24% SS only, 16% SS with RA), similar to standard patient populations [25, 33]. As a whole, the number of cases identified in this study sample is within range of published rates [10–12, 23, 24]

SLE and SS are uncommon diseases, especially in males, who comprise the majority of pesticide users in the AHS. Conversely, in females, who comprise the majority of SLE/SS cases, pesticide use was less common. This limited our ability to examine pesticide associations in males only, and uncommon pesticides in women. Some results may be due to chance, however most can be considered hypothesis generating. We adjusted for correlated pesticides, but cannot rule out unmeasured confounders. AHS participants have greater pesticide exposures than the general population, so findings may not be generalizable to non-farming populations. Most males and about half of the females grew up on a farm and lived/worked on a farm as adults, limiting comparisons with population-based studies showing associations of SLE with farming [13, 15].

SLE and SS are complex diseases, with diverse etiologic pathways, reflected in shared and distinctive metabolic, genetic, and epigenetic characteristics [65–67]. We examined multiple pesticide active ingredients, and other immune modifying exposures in the farm environment, but lacked the sample size and temporal precision to examine potential mixtures or combined effects of realistic exposure scenarios. Such questions may best be addressed in experimental or biomarker studies, considering both direct (e.g., immunotoxic) and indirect (e.g., neuroendocrine, microbiomic, metabolomic) mechanisms, leveraging ‘omics’ technologies to examine microbial and metabolic profiles or changes to the epigenome associated with pesticides and SLE/SS [68–71].

In sum, our findings highlight several plausible agricultural risk factors for SLE/SS, but also reveal a complex picture, with inverse associations for some pesticides as well as childhood farm residence, warranting further investigation in other populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Z01-ES049030) and National Cancer Institute (Z01-CP010119).

Footnotes

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interests

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Miller FW, et al. , Epidemiology of environmental exposures and human autoimmune diseases: findings from a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Expert Panel Workshop. J Autoimmun, 2012. 39(4): p. 259–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parks CG and De Roos AJ, Pesticides, chemical and industrial exposures in relation to systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus, 2014. 23(6): p. 527–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parks CG, et al. , Understanding the role of environmental factors in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, 2017. 31(3): p. 306–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prisco LC, Martin LW, and Sparks JA, Inhalants other than personal cigarette smoking and risk for developing rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol, 2020. 32(3): p. 279–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chua MHY, et al. , Association Between Cigarette Smoking and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: An Updated Multivariate Bayesian Metaanalysis. J Rheumatol, 2020. 47(10): p. 1514–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbhaiya M, et al. , Cigarette smoking and the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus, overall and by anti-double stranded DNA antibody subtype, in the Nurses’ Health Study cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis, 2018. 77(2): p. 196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer A, et al. , Pesticide Exposure and Risk of Rheumatoid Arthritis among Licensed Male Pesticide Applicators in the Agricultural Health Study. Environ Health Perspect, 2017. 125(7): p. 077010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parks CG, et al. , Rheumatoid Arthritis in Agricultural Health Study Spouses: Associations with Pesticides and Other Farm Exposures. Environ Health Perspect, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parks CG, et al. , Farming tasks and the development of rheumatoid arthritis in the agricultural health study. Occup Environ Med, 2019. 76(4): p. 243–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarukitsopa S, et al. , Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus and cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a predominantly white population in the United States. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2015. 67(6): p. 817–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stojan G and Petri M, Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol, 2018. 30(2): p. 144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izmirly PM, et al. , Prevalence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in the United States: Estimates From a Meta-Analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registries. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2021. 73(6): p. 991–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parks CG, et al. , Occupational exposure to crystalline silica and risk of systemic lupus erythematosus: a population-based, case-control study in the southeastern United States. Arthritis Rheum, 2002. 46(7): p. 1840–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parks CG, et al. , Insecticide use and risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2011. 63(2): p. 184–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold LS, et al. , Systemic autoimmune disease mortality and occupational exposures. Arthritis Rheum, 2007. 56(10): p. 3189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsson AR, et al. , Occupations and exposures in the work environment as determinants for rheumatoid arthritis. Occup Environ Med, 2004. 61(3): p. 233–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khuder SA, Peshimam AZ, and Agraharam S, Environmental risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis. Rev Environ Health, 2002. 17(4): p. 307–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Sundquist J, and Sundquist K, Socioeconomic and occupational risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide study based on hospitalizations in Sweden. J Rheumatol, 2008. 35(6): p. 986–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper GS, et al. , Occupational risk factors for the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol, 2004. 31(10): p. 1928–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parks CG, et al. , Childhood agricultural and adult occupational exposures to organic dusts in a population-based case-control study of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus, 2008. 17(8): p. 711–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper GS, et al. , Occupational and environmental exposures and risk of systemic lupus erythematosus: silica, sunlight, solvents. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2010. 49(11): p. 2172–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parks CG, D’Aloisio AA, and Sandler DP, Early Life Factors Associated with Adult-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Women. Front Immunol, 2016. 7: p. 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maciel G, et al. , Incidence and Mortality of Physician-Diagnosed Primary Sjogren Syndrome: Time Trends Over a 40-Year Period in a Population-Based US Cohort. Mayo Clin Proc, 2017. 92(5): p. 734–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maciel G, et al. , Prevalence of Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome in a US Population-Based Cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2017. 69(10): p. 1612–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo CF, et al. , Familial Risk of Sjogren’s Syndrome and Co-aggregation of Autoimmune Diseases in Affected Families: A Nationwide Population Study. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2015. 67(7): p. 1904–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bjork A, Mofors J, and Wahren-Herlenius M, Environmental factors in the pathogenesis of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. J Intern Med, 2020. 287(5): p. 475–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaigne B, et al. , Primary Sjogren’s syndrome and occupational risk factors: A case-control study. J Autoimmun, 2015. 60: p. 80–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mofors J, et al. , Infections increase the risk of developing Sjogren’s syndrome. J Intern Med, 2019. 285(6): p. 670–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomi AL, et al. , Brief Report: Monoclonal Gammopathy and Risk of Lymphoma and Multiple Myeloma in Patients With Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2016. 68(5): p. 1245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones RR, et al. , Farm residence and lymphohematopoietic cancers in the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Environ Res, 2014. 133: p. 353–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alavanja MC, et al. , Non-hodgkin lymphoma risk and insecticide, fungicide and fumigant use in the agricultural health study. PLoS One, 2014. 9(10): p. e109332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hemminki K, et al. , Autoimmune diseases and hematological malignancies: Exploring the underlying mechanisms from epidemiological evidence. Semin Cancer Biol, 2020. 64: p. 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theander E and Jacobsson LT, Relationship of Sjogren’s syndrome to other connective tissue and autoimmune disorders. Rheum Dis Clin North Am, 2008. 34(4): p. 935–47, viii-ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alavanja MC, et al. , The Agricultural Health Study. Environ Health Perspect, 1996. 104(4): p. 362–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silvex (2,4,5-TP). Rev Environ Contam Toxicol, 1988. 104: p. 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delancey JO, et al. , Occupational exposure to metribuzin and the incidence of cancer in the Agricultural Health Study. Ann Epidemiol, 2009. 19(6): p. 388–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bomann W, et al. , Metribuzin-induced non-adverse liver changes result in rodent-specific non-adverse thyroid effects via uridine 5’-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase (UDPGT, UGT) modulation. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol, 2021. 122: p. 104884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Environmental Protection Agency O.o.W., Health Effects Support Document for Metribuzin 2003.

- 39.Porter WP, et al. , Groundwater pesticides: interactive effects of low concentrations of carbamates aldicarb and methomyl and the triazine metribuzin on thyroxine and somatotropin levels in white rats. J Toxicol Environ Health, 1993. 40(1): p. 15–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saberi Hosnijeh F, et al. , Changes in lymphocyte subsets in workers exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Occup Environ Med, 2012. 69(11): p. 781–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holsapple MP, et al. , A review of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced changes in immunocompetence: 1991 update. Toxicology, 1991. 69(3): p. 219–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J and McMurray RW, Effects of chronic exposure to DDT and TCDD on disease activity in murine systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus, 2009. 18(11): p. 941–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mustafa A, et al. , Prenatal TCDD causes persistent modulation of the postnatal immune response, and exacerbates inflammatory disease, in 36-week-old lupus-like autoimmune SNF1 mice. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol, 2011. 92(1): p. 82–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schurman SH, et al. , Transethnic associations among immune-mediated diseases and single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the aryl hydrocarbon response gene ARNT and the PTPN22 immune regulatory gene. J Autoimmun, 2020. 107: p. 102363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen NT, et al. , The roles of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in immune responses. Int Immunol, 2013. 25(6): p. 335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ehrlich AK, et al. , TCDD, FICZ, and Other High Affinity AhR Ligands Dose-Dependently Determine the Fate of CD4+ T Cell Differentiation. Toxicol Sci, 2018. 161(2): p. 310–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curran CS, et al. , PD-1 immunobiology in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun, 2019. 97: p. 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shinde R, et al. , Apoptotic cell-induced AhR activity is required for immunological tolerance and suppression of systemic lupus erythematosus in mice and humans. Nat Immunol, 2018. 19(6): p. 571–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parks CG, et al. , Lifetime Pesticide Use and Antinuclear Antibodies in Male Farmers From the Agricultural Health Study. Front Immunol, 2019. 10: p. 1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ladics GS, et al. , Evaluation of the humoral immune response of CD rats following a 2-week exposure to the pesticide carbaryl by the oral, dermal, or inhalation routes. J Toxicol Environ Health, 1994. 42(2): p. 143–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Jesus Andino F, Lawrence BP, and Robert J, Long term effects of carbaryl exposure on antiviral immune responses in Xenopus laevis. Chemosphere, 2017. 170: p. 169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeon SD, Lim JS, and Moon CK, Carbofuran suppresses T-cell-mediated immune responses by the suppression of T-cell responsiveness, the differential inhibition of cytokine production, and NO production in macrophages. Toxicol Lett, 2001. 119(2): p. 143–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang F, et al. , Acceleration of autoimmunity by organochlorine pesticides: a comparison of splenic B-cell effects of chlordecone and estradiol in (NZBxNZW)F1 mice. Toxicol Sci, 2007. 99(1): p. 141–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sobel ES, et al. , Acceleration of autoimmunity by organochlorine pesticides in (NZB x NZW)F1 mice. Environ Health Perspect, 2005. 113(3): p. 323–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edwards M, Dai R, and Ahmed SA, Our Environment Shapes Us: The Importance of Environment and Sex Differences in Regulation of Autoantibody Production. Front Immunol, 2018. 9: p. 478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bach JF, The hygiene hypothesis in autoimmunity: the role of pathogens and commensals. Nat Rev Immunol, 2018. 18(2): p. 105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poole JA and Romberger DJ, Immunological and inflammatory responses to organic dust in agriculture. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 2012. 12(2): p. 126–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Depner M, et al. , Maturation of the gut microbiome during the first year of life contributes to the protective farm effect on childhood asthma. Nat Med, 2020. 26(11): p. 1766–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.House JS, et al. , Early-life farm exposures and adult asthma and atopy in the Agricultural Lung Health Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2017. 140(1): p. 249–256.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Torén K, et al. , Occupational exposure to dust and to fumes, work as a welder and invasive pneumococcal disease risk. Occup Environ Med, 2020. 77(2): p. 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zeidler-Erdely PC, Erdely A, and Antonini JM, Immunotoxicology of arc welding fume: worker and experimental animal studies. J Immunotoxicol, 2012. 9(4): p. 411–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tremlett H, et al. , Sun exposure over the life course and associations with multiple sclerosis. Neurology, 2018. 90(14): p. e1191–e1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arkema EV, et al. , Exposure to ultraviolet-B and risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis among women in the Nurses’ Health Study. Ann Rheum Dis, 2013. 72(4): p. 506–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walitt BT, et al. , Validation of self-report of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus: The Women’s Health Initiative. J Rheumatol, 2008. 35(5): p. 811–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bellocchi C, et al. , Identification of a Shared Microbiomic and Metabolomic Profile in Systemic Autoimmune Diseases. J Clin Med, 2019. 8(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bengtsson AA, et al. , Metabolic Profiling of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Comparison with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome and Systemic Sclerosis. PLoS One, 2016. 11(7): p. e0159384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Imgenberg-Kreuz J, et al. , Shared and Unique Patterns of DNA Methylation in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Front Immunol, 2019. 10: p. 1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoang TT, et al. , Epigenome-Wide DNA Methylation and Pesticide Use in the Agricultural Lung Health Study. Environ Health Perspect, 2021. 129(9): p. 97008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moser VC, et al. , Assessment of serum biomarkers in rats after exposure to pesticides of different chemical classes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2015. 282(2): p. 161–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Silverman GJ, The microbiome in SLE pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 2019. 15(2): p. 72–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou M and Zhao J, A Review on the Health Effects of Pesticides Based on Host Gut Microbiome and Metabolomics. Front Mol Biosci, 2021. 8: p. 632955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.