Abstract

A thorough knowledge of variable and complex tooth morphology, detailed exploration of the internal anatomy and underlying pathology, proper interpretation of radiographic images, conservative access to explore all the canals, thorough debridement and disinfection of canal system, three-dimensional seal by obturation, and good coronal seal by final restoration are essential steps in the management for a successful endodontic treatment outcome. Clinical management of rare case with extra canals in the lower anterior teeth and premolars had to undergo root canal therapy has been described. Referring to the hard-tissue repository of the human dental internal morphology, carefully interpreting multiangled radiography/cone-beam computed tomography, using tools such as magnifying loupes with illumination and ultrasonics, thermoplasticized gutta-percha system to obturate, are very helpful to the clinician can achieve this goal. This article describes and illustrates the management of a rare case with Vertucci's Type VIII canal anatomy in lower anterior teeth and premolars.

Keywords: Dental pulp cavities, Kinternal anatomy, intraoral periapical radiograph, magnification; ultrasonics

INTRODUCTION

A thorough understanding of the complexities of the root canal system and a careful interpretation of multiangled radiographs or cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) images, proper conservative access preparation under magnification, and illumination using ultrasonic tips to locate all the canal orifices are essential prerequisites for a successful treatment outcome. Proper glide path followed by systematic approach for thorough debridement, three-dimensional seal by obturation, and coronal restoration is added key factors for the success of endodontic therapy. When clinician has in-depth knowledge of diseases of the pulp and periapical region and three-dimensional morphology of anatomical structures and their variations, there will be less chance for mishaps such as missed canals and perforations to occur during the root canal therapy. Missed canals may harbor pathogenic organisms, which may result in endodontic treatment failure.[1] Perforations, especially at cervical and middle 3rd and of pathological etiology, depend on the location, size, and time from the occurrence can lead to a guarded long-term prognosis for the tooth.[2]

Mandibular anterior and premolar teeth often exhibit complex anatomy that cannot be clearly detected in two-dimensional periapical radiographs.[3,4] Additional radiographs with different horizontal angulations (20°–30° mesial or distal) or CBCT may be required to trace all these canals. The literature on mandibular incisors reveals that 11%–68% of mandibular incisors possess two canals, although in many of these cases, the canals merge into one in the apical 1–3 mm of the root.[5] A literature review by Vertucci reported a wide range of variations regarding the prevalence of a second canal that has been related to methodological and racial differences.[6] A systematic review reported that there is varied root canal morphology that varies with race, sex, and age.[7] Kartal and Yanikoglu studied 100 mandibular anterior teeth and found two new root canal types which had not been previously identified. The first new configuration consists of two separate canals which extend from the pulp chamber to mid root where the lingual canal divides into two; all three canals then join in the apical third and exit as one canal. In their second configuration, one canal leaves the pulp chamber, divides into two in the middle third of the root, rejoins to form one canal which again splits and exits as three separate canals with separate foramina. Lots of variations in the results of studies on incidence in the literature may be attributable to several factors, one of which is the methodology of the study.[8]

Mandibular premolars have been considered enigma to the endodontists because of their extremely complex morphology and presence of anatomical aberrations, make them generally most difficult teeth to manage endodontically. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Jojo Kottoor et al. on the incidence of variations in morphology mandibular premolars and found that about 23.55% of teeth had two canals and the incidence of three or more canals in mandibular first premolars was considerably lower (0%–5%). The mandibular first premolars showed more bifurcation of canals terminating in multiple apical foramina (23%–30%) as compared to the second premolars (15%–20%). Mandibular second bicuspids presented with a higher incidence of single root (99.28%) and Vertucci's Type I canal anatomy (86.9%). The presence of the second root was rare 0.0%–4.4% (average 0.61%) in those teeth. In different studies, analyzed by them, showed varied range of second canal in different populations, ranging from 2.5% to 34.4%. Second premolars presented with a second canal in the Indian population are from 13.5% to 20%. Three or more canals in mandibular second premolars were rarely reported (0%–2%). No teeth were presented with three or more canals in mandibular second premolars in Indian and Hispanic populations. The literature revealed very few cases with the presence of three canals in maxillary anterior incisors and lower premolars.[7,9]

The presence of Vertucci's Type IV canal anatomy in the mandibular teeth has been frequently reported in the literature.[10] However, the presence of Vertucci's Type VIII canal anatomy where three canals in the roots of mandibular premolars and anterior teeth is a rarity. The following case report discusses the diagnosis and management of mandibular anterior and premolars with two and three canals.

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old male patient reported to the dental clinic with a chief complaint of inability to chew normal food because of severe hypersensitivity in lower teeth for 2 weeks before his visit. Cold food exaggerated his symptoms and used to linger for some more minutes. The patient gave a history of enjoying chewing tough food such as bone and tough meat, which gave him lately gnawing pain and fatigue of muscle sometimes, which slowly increased day by day. There was no history of habits of drinking alcohol or aerated drinks. No pan chewing. No history of night grinding or bruxism. No significant medical history.

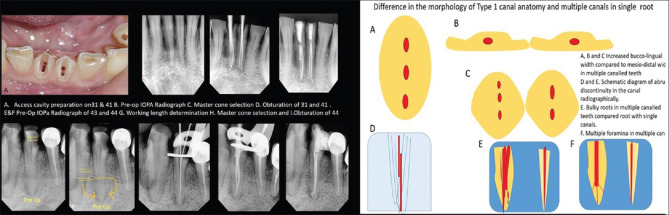

On extraoral examination, the patient has bilateral prominently angled mandible with strong masseter muscles. Intraoral examination revealed generalized attrition with loss of tooth structure on the occlusal surface with dentinal exposure [Figure 1], mild gingival recession on the free gingiva on buccal side of almost all mandibular teeth. Mandibular right canine and first premolar had deep proximal carious lesions, extended subgingivally, and approaching pulp space.

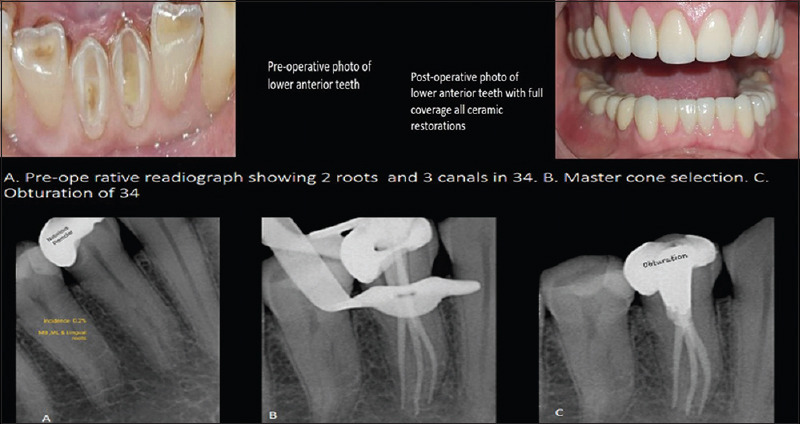

Figure 1.

Preoperative and postoperative photos and showing radiographic images of 34

Both the mandibular central incisors had unusual external morphology. Their labiolingual width was more than their mesiodistal width. Incisal surfaces were attrited; canal anatomy was faintly seen through dentin. Exaggerated response for pulp sensibility tests with respect 31 and 41. IOPA radiographs showed no changes in the periapical region of 31 and 41. Coronal radiolucency was observed indicating deep caries in the proximal aspect of the right mandibular canine (tooth no. 43) and first mandibular premolar (tooth no. 44) [Figure 2]. The second mandibular premolar (tooth no. 45) had been previously root canal treated with the coronal radio-opacity indicating the presence of full-coverage crown. There is pain on probing the incisal and occlusal surfaces of attrited teeth with mild tenderness on percussion in 34. Left mandibular first premolar (tooth no. 34) showed coronal radio-opacity of metallic restoration with radiolucency underneath the restoration, suggesting secondary caries [Figure 1]. On cold stimulus, the patient had lingering pain suggesting chronic irreversible pulpitis. Mild-to-moderate tenderness in all the mandibular 34 suggesting asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis with symptomatic apical periodontitis. Pulp sensibility tests (cold, heat, and EPT) showed no response for 44, exaggerated response for 34, 31, and 41, normal positive response for 43 [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 2.

Showing photo of anterior teeth and radiographic images of 31,41, and 44. On the right sided image, differences in the morphology of Type 1 canal anatomy and multiple canals in single root. (A-C) Increase in buccolingual width compared to mesiodistal width in multiple canalled teeth (D and E) Schematic diagram of abrupt discontinuity in the canal radiographically (E) Bulky roots in multiple canalled teeth compared root with single canals F-Multiple foramina in multiple root canals

External morphology of 31 and 41 was unusual with increased labiolingual width indicating the presence of additional canals [Figure 2]. Root morphology in IOPA radiographs showed sudden break in continuity of canals and root outline, tortuous roots suggesting the presence of additional roots and canals [Figures 1 and 2]. Table 1 shows teeth needed endodontic therapy with the number of root, canals, classification of canals they come under, and pulpal and periapical diagnosis treatment planning is done with the informed consent from the patient.

Table 1.

Enlisting number of roots, foramina of mandibularanterior and premolars, and classification of their canal anatomy

| Tooth No. | No. of roots | Root canal anatomy | Vertucci’s classification | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | 2 roots fused to one single root | 2 canals | Type IV | Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with symptomatic apical periodontitis with respect to 31 and 41 |

| 41 | 2 roots fused to one single root | 3 canals | Type VIII | Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with symptomatic apical periodontitis with respect to 31 and 41 |

| 34 | Large pulp chamber trifurcated into 3 canals at midroot level (Hypotaurodontism) | 3 canals | Type VIII | Asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis with symptomatic apical periodontitis |

| 44 | 2 roots fused into single root | 2 canals trifurcated at the apex and exited as 3 apical foramina | Type IV with additional apical foramen | Pulpal necrosis with symptomatic apical periodontitis |

Following local anesthesia using lidocaine 2% with epinephrine 1:50,000, access cavities were prepared through occlusal surfaces of teeth using Endo Access bur (Dentsply) for all four teeth. Rubber dam isolation was not possible because the patient was a mouth breather, and patient had severe discomfort every time rubber dam was tried to be placed. Hence, teeth were isolated with sterile cotton rolls with floss tied to instruments. Canal orifices were located using DG 16 probe. Chamber floor troughing was done with ultrasonic instrument (ET18D, Satelec, Acteon) to explore all the canals 41 had three canals. Thirty-one had two roots fused into single root and two canals, 34 had single large pulp chamber (hypotaurodontism), and canals trifurcated at mid root level into three canals with three apical foramina. (Vertucci's Type VIII). Forty-one had single root with three canals (Vertucci's Type VIII), and 44 had two roots fused into single root with two canals and three apical foramina [Figure 2]. Thirty-four showed single root with three canals [Figure 1]. The working length was determined using Root ZX electronic apex locator (J Morita Corp., Kyoto, Japan) and then verified radiographically.[Figure 2]. Glide path was achieved using #10 K-File (Mani, Japan) for all the teeth; coronal preflaring was done with Gates Glidden burs up to size 3 (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland).

Canal disinfection was done using 5.25% NaOCl, 17% EDTA, and finally, normal saline as irrigants and instrumentation was done using EdgeEndo and Ni-Ti files. Apical preparation was done up to 30 sizes (4% taper.) The canals were dried and dressed with Ca (OH) 2 and sealed coronally with sterile cotton plug and temporary cement (Cavit). The patient was asymptomatic after the first appointment. Every 4th day, dressings were changed and Ca (OH)2 was placed as intracanal medicament for 2 weeks. Master cones were selected and obturation done by Touch n Heat (Sybron endo) by warm vertical compaction technique and Backfill using Denjoy. Postendo restoration was done using GIC barrier and resin composite core. Finally, full coverage of all ceramic crowns (E-Max) was placed. The patient was recalled after 1 week for check-up and follow-ups are going on.

DISCUSSION

The importance of careful and thorough preoperative evaluation of the internal anatomy of teeth cannot be overemphasized. In the present case, all the canals were evaluated using the help of multiangled radiography, magnifying loupes and surgical microscopes with added LED light and ultrasonic tips.[11] In the present case, the patient had symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, having severe sensitivity in tooth due to pulpal inflammation in 31 and 41. Exaggerated response to stimulus, lingering pain for pulp sensibility tests, referred pain confirm the diagnosis according to AAE Consensus for pulpal diagnosis.[12] Thirty-one and 41 had increased labiolingual width indication additional canals [Figure 1]. Thirty-four had lingering pain for pulp sensibility tests showed secondary caries involving pulp diagnosed as asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis, and 44 showed pulpal necrosis with symptomatic apical periodontitis [Figures 1 and 2].

Clinician noticed an unusual morphology of the root canals in the intraoral radiography and suspected extra roots and canals in the incisors as well as premolars. A mesially angulated (20°–30°-mesial angle) IOPA radiographs were taken to identify the presence of extra canals. This emphasizes the importance of preoperative radiographs in root canal therapy and cannot be overlooked. In the present case, nonavailability of CBCT was a disadvantage. CBCT would have been an ideal tool to explore the canals by means of accuracy, and three-dimensional data acquisition of multiple teeth would offer maximum information.

The presence of three canals in mandibular central incisors has rarely been reported in the literature.[6,7,8] A study found the presence of Types I (65.2%), III (2.6%), V (22.6%), and VII (0.9%) in mandibular first premolar along with 14.8% of 2 canalled roots with three apical foramina.[13] None of the studies showed Type VIII canal anatomy. In the present case, teeth number 41 has three orifices on the floor and three canals with three apical foramina (Vertucci's; Type VIII). According to Vertucci, if the separation of the orifices was more than 3 mm, the canals will separate throughout their entire course.[6] There are additional morphological features to suggest additional canals in a root. Clinically, lower anterior have thinner buccolingually compared to their mesiodistal width. Abrupt break in the canal pathways in radiograph suggests multiple canals or branching of root canal. Usually in such cases, roots will be bulky root instead of slender. In such situation, multiple apical foramina instead of single apical foramen are expected sometimes appreciated radiographically [Figure 2].

One of the reasons for the failure of root canal therapy is missed canals due to inadequate access preparation. In the present case, the access cavity was extended on lingual side to explore all the canal orifices. Since no articles mentioned about three canals in mandibular incisors, this third canal in the present case would have been missed if access cavity was not prepared properly. Moreover, ultrasonic troughing magnifications suspected the presence of extra canals.

Systematic reviews have shown variations in the incidence of the number of canals and roots, mainly attributed to the difference in methodology of the study.[6,8,14] Studies have shown that higher prevalence (30%61.5%) of two-canaled incisors were reported when multiangled radiographs or radio-opacifiers were used.[3,8,15,16]

Magnification plays a vital role in the visualization of the pulp chamber and identifies extra orifices. In this case, the clinician worked with magnifying loupes (×3) with illumination. Magnification and ultrasonics made the identification of orifices easy. In the present case, the ET18D tip (Satelec, Acteon) is a diamond-coated tip was used for access preparation, finishing the access cavity, removing dentine overhangs, and calcification, if any. The root canals were enlarged using EdgeEndo (EdgeEn-do; Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States), 4% taper Ni-Ti instruments. Manufacturers claim that these files cause less friction and stress on the instrument and allow for more controlled canal preparation. It enhances disinfection and extrudes less debris beyond the apex. Postinstrumentation follow-up after 24 h showed no symptoms. Canals were not shifted and 4% taper removed dentin judiciously. Ca (OH)2 as an intracanal dressing has proven to be the gold standard antimicrobial agent for chronic cases. All the canals were obturated by Touch n Heat (Sybron Endo), a warm vertical compaction technique, and Backfill using Freefile (Denjoy). Follow-up appointments at 1 week and 1 month, all teeth were asymptomatic.

CONCLUSION

This clinical report presented the endodontic management of a very rare case of two and three canalled mandibular anterior and premolar teeth. Highly variable structural morphology of roots and canals influence the outcomes of both nonsurgical and surgical endodontic therapy. Good preoperative radiographic images, higher magnification, and though knowledge on internal anatomy are necessary for successful treatment outcome.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoen MM, Pink FE. Contemporary endodontic retreatments: An analysis based on clinical treatment findings. J Endod. 2002;28:834–6. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200212000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsesis I, Rosenberg E, Faivishevsky V, Kfir A, Katz M, Rosen E. Prevalence and associated periodontal status of teeth with root perforation: A retrospective study of 2,002 patients’ medical records. J Endod. 2010;36:797–800. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rankine-Wilson RW, Henry P. The bifurcated root canal in lower anterior teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1965;70:1162–5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1965.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin KA, Dowson J. Incidence of two root canals in human mandibular incisor teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974;38:122–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(74)90323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boruah LC, Bhuyan AC. Morphologic characteristics of root canal of mandibular incisors in North-East Indian population: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2011;14:346–50. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.87195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vertucci FJ. Root canal morphology and its relationship to endodontic procedures. Endod Top. 2005;10:3–29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kottoor J, Albuquerque D, Velmurugan N, Kuruvilla J. Root anatomy and root canal configuration of human permanent mandibular premolars: A systematic review. Anat Res Int. 2013;2013:254250. doi: 10.1155/2013/254250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kartal N, Yanikoğlu FC. Root canal morphology of mandibular incisors. J Endod. 1992;18:562–4. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81215-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monardes H, Herrera K, Vargas J, Steinfort K, Zaror C, Abarca J. Root anatomy and canal configuration of maxillary premolars: A cone-beam computed tomography study. Int J Morphol. 2021;39:463–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukhaimer RH. Evaluation of root canal configuration of mandibular first molars in a Palestinian population by using cone-beam computed tomography: An ex vivo study. Int Sch Res Notices. 2014;2014:583621. doi: 10.1155/2014/583621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nattress BR, Martin DM. Predictability of radiographic diagnosis of variations in root canal anatomy in mandibular incisor and premolar teeth. Int Endod J. 1991;24:58–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1991.tb00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohammadi Z, Asgary S, Shalavi S, V Abbott P. A clinical update on the different methods to decrease the occurrence of missed root canals. Iran Endod J. 2016;11:208–13. doi: 10.7508/iej.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu N, Li X, Liu N, Ye L, An J, Nie X, et al. A micro-computed tomography study of the root canal morphology of the mandibular first premolar in a population from Southwestern China. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:999–1007. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0778-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dallak AE, Moafa WM, Malhan SM, Shami AO, Ageeli OA, Alhaj WS, et al. A root and canal morphology of permanent maxillary and mandibular incisors teeth: A systematic review and comparison with Saudi Arabian population. Biosci Biotechnol Res Commun. 2020;13:1723–33. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hession RW. Endodontic morphology. II. A radiographic analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;44:610–20. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(77)90306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calişkan MK, Pehlivan Y, Sepetçioğlu F, Türkün M, Tuncer SS. Root canal morphology of human permanent teeth in a Turkish population. J Endod. 1995;21:200–4. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80566-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]