Abstract

The Vibrio sp. strain XY-214 β-1,3-xylanase gene cloned in Escherichia coli DH5α consisted of an open reading frame of 1,383 nucleotides encoding a protein of 460 amino acids with a molecular mass of 51,323 Da and had a signal peptide of 22 amino acids. The transformant enzyme hydrolyzed β-1,3-xylan to produce several xylooligosaccharides.

β-1,3-Xylan is a homopolymer of β-1,3-linked d-xylose and is a polysaccharide peculiar to marine algae; it is contained in the cell walls of red algae (Porphyra and Bangia) and green algae (Caulerupa, Bryopsis, and Udotea) (9, 13). β-1,3-Xylanase (1,3-β-d-xylan xylanohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.32) is a β-1,3-xylan-hydrolyzing enzyme that is useful for structural analysis of the cell walls of these algae and for protoplast isolation, which is an important technique for cell fusion and gene manipulation of algae. On the other hand, β-1,4-xylan is a major component of hemicelluloses of land plant cell walls (19). β-1,4-Xylanases (1,4-β-d-xylan xylanohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.8) are produced by many kinds of microorganisms, including aerobic and anaerobic mesophiles and thermophiles, and their biochemical and molecular characteristics have been widely studied (6, 14, 15). Compared with β-1,4-xylanase, there have been only a few reports on enzymatic studies of β-1,3-xylanase based on three bacteria, Vibrio sp. strain AX-4 (1), Pseudomonas sp. strain PT-5 (21), and Alcaligenes sp. strain XY-234 (2), as well as one fungus, Aspergillus terreus A-07 (7). Hernandez et al. have only recently entered data on sequencing of the β-1,3-xylanase gene in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database (A. Hernandez, J. C. Lopez, J. L. Copa-Patino, and T. Soliveri, unpublished data. [DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AF121865]).

We have purified β-1,3-xylanase from Vibrio sp. strain XY-214 isolated from a marine environment and characterized its properties (3). In this paper, we describe the cloning and DNA sequencing of the β-1,3-xylanase gene (txyA) of Vibrio sp. strain XY-214 and its expression in Escherichia coli.

Construction of the probe for cloning of the txyA gene.

β-1,3-Xylanase was purified according to a previously described procedure (3). After the purified enzyme was digested with a sequencing grade-modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, Wis.), the tryptic digest was fractionated by high-performance liquid chromatography (μ Bondsphere, 300 Å, C18, 3.9 by 150 mm; Waters). The 16th peak (peptide 16) out of 33 peaks separated was collected and blotted onto a glass filter treated with Bio Brene Plus (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The N-terminal amino acid sequence was determined by automated Edman sequencing on a model 473A gas-phase sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

The degenerate primers (primers F and R) were designed on the basis of the underlined parts of the N-terminal amino acid sequences of the purified β-1,3-xylanase (sequence LDGKLVPDQGILVSVGQDV) and peptide 16 (sequence WAAPYNEGYWGDSR). The alignment of primer F is GAYGGNAARTTIGTNCCNGA, and that of primer R is CCCCARTNACCYTCRTTRTA, where Y, R, I, and N indicate C or T, A or G, inosine, and any nucleotides, respectively. For construction of the probe for cloning of txyA, one specifically amplified oligonucleotide was obtained from a template of genomic DNA of Vibrio sp. strain XY-214 by PCR with the degenerate primers (F and R). The PCR product ligated into pUC19-T vector (12) was composed of 860 bp encoding 286 amino acid residues. The sequences of the first seven N-terminal and the last six C-terminal amino acids of the fragment were confirmed to be identical to the amino acid sequence of native β-1,3-xylanase and peptide 16. Therefore, the DNA insert in pUC19-T vector was considered to be derived from the gene encoding β-1,3-xylanase and was used as the probe for cloning.

Cloning of the txyA gene.

Genomic DNA was conferred by double digestion with two enzymes (BglII and XbaI), and fragments of about 4.4 kbp, which were deemed to be a suitable size considering the molecular mass of the enzyme, were selected as positive on an alkaline phosphatase-labeled probe. When BglII-XbaI fragments were ligated into pBluescript II KS(−) and transformed into E. coli DH5α, 22 of the 860 clones hybridized to the alkaline phosphatase-labeled probe. The recombinant plasmid yielded from 1 of the 22 clones was termed pTXY1.

Analysis of DNA sequence.

The pTXY1 was digested singly with three restriction enzymes (EcoRV, HindIII and KpnI), and the fragments were subcloned into pBluescript II KS(−) vector. The subcloned fragments, together with T3 and T7 primers and some synthetic primers, were used to sequence the entire BglII-XbaI fragment (ca. 4.4 kbp). The nucleotide sequences of both strands of the subcloned DNA inserts were determined with an Applied Biosystems model 373A automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The nucleotide sequence data of the fragment appear in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under the accession no. AB029043.

The insert in pTXY1 was found to have one complete open reading frame (ORF-2), which was placed between two incomplete ORFs (ORF-1 of 2,268 bp and ORF-3 of 504 bp). The amino acid sequences of positions 23 (Leu) to 41 (Var) and 300 (Trp) to 313 (Arg) in ORF-2 coincided with the N-terminal amino acid sequences of native β-1,3-xylanase and peptide 16, respectively. Therefore, ORF-2, extending from position 2457 to position 3839, was estimated to code for the txyA gene of Vibrio sp. strain XY-214. The txyA gene was composed of 1,383 bp encoding 460 amino acid residues with a molecular mass of 51,323 Da and was found to contain a signal peptide consisting of 22 amino acids from the first methionine. The signal peptide exhibited the structural features of a signal peptide which is known generally to possess a few positively charged residues, a hydrophobic core of approximately 12 amino acids, and the Ala-X-Ala sequence that is the most frequent sequence preceding signal peptidase cleavage (16, 20). Thus, after processing of the signal peptide, the molecular mass of the mature enzyme seems to be composed of 438 amino acids comprising a molecular mass of 49,050 Da. The 103-nucleotide region between the translation initiation codon (ATG) of ORF-2 and the first palindrome (2,277 to 2,308 bp) structure upstream from it was large enough for the promoter. A putative ribosome-binding site sequence (AGGAAG) is located 13 nucleotides upstream from the initiation codon. Putative promoter sequences of the −10 region (TTTAAT) and −35 region (TTGTTC) were found 28 and 47 bp upstream from the initial codon, respectively. The palindromic sequence located 24 bp downstream of the stop codon could form an mRNA hairpin loop with a ΔG of −15.4 kcal/mol (ca. −64.4 kJ/mol) (11) and might act as a signal for transcription termination of a rho-independent promoter.

ORF-2 was in the opposite orientation to the LacZ promoter of pBluescript, and the transformant E. coli DH5α strain harboring pTXY1 exhibited β-1,3-xylanase activity when grown in culture medium supplemented with or without IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Therefore, the txyA gene in pTXY1 was found to be able to express the enzyme activity by using its own promoter.

Homology.

The deduced amino acid sequence (460 residues) of β-1,3-xylanase from Vibrio sp. strain XY-214 was compared with entries in the Blast sequence databases. The only glycoside hydrolase having high homology with Vibrio sp. strain XY-214 β-1,3-xylanase was the mannosidase from Thermotoga neapolitana, of which the gene consisted of 1,041 bp encoding 346 amino acids (D. A. Yernoal, S. Y. Rani, R. F. Sullivan, and D. E. Eveleigh, unpublished data [DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. U58632]); the homology between both enzymes was 40.6% of their amino acid sequences.

There have been many reports on the amino acid sequences of β-1,4-xylanases, which belong to families 5, 10, 11, and 43 among 77 families of glycoside hydrolase classified on the basis of amino acid sequence similarities (8). Of the amino acid sequences of β-1,3-xylanase, that of Streptomyces has been registered in the database recently (A. Hernandez, J. C. Lopez, J. L. Copa-Patino, and J. Soliveri, unpublished data [DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AF121865]) Streptomyces β-1,3-xylanase (EC 3.2.1.32) exhibited over 80% homology to β-1,4-xylanases of some microorganisms belonging to family 10, which includes β-1,4-xylanase (EC 3.2.1.8) and cellobiohydrolase (EC 3.2.1.91). However, the amino acid sequence of β-1,3-xylanase of Vibrio sp. strain XY-214 had only 17% homology to that of Streptomyces β-1,3-xylanase. We have not obtained information on enzymatic properties other than the sequences entered at the database on the Streptomyces β-1,3-xylanase and the T. neapolitana mannosidase because such data have not been published.

Expression of the recombinant β-1,3-xylanase from a transformant.

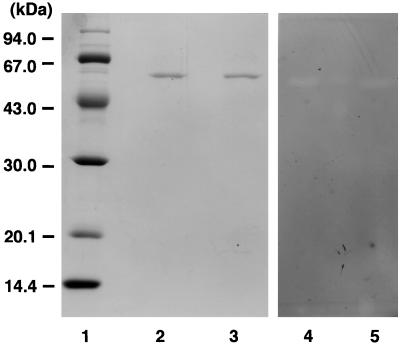

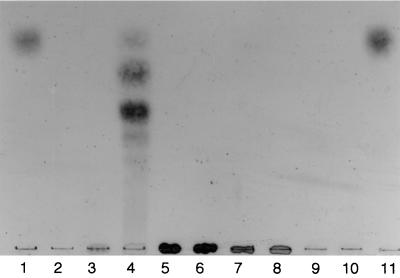

The activity of the enzyme toward β-1,3-xylan was measured by the release of reducing sugar equivalent (18). β-1,3-Xylan was prepared from a green alga, Caulerpa racemosa var. laetevirens according to the method of Iriki et al. (9). The transformant was grown in Luria-Bertani medium containing ampicillin (3,000 ml). The cells collected by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min) were suspended in 70 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and disrupted by a sonicator. The β-1,3-xylanase activity of the supernatant collected by centrifugation was 8.5 U, though the extracellular enzyme of Vibrio sp. strain XY-214 exhibited 400 U per 3 liters of culture fluid. The supernatant was purified by a combination of Q Sepharose (3), β-1,3-xylan-affinity (1), and Mono Q (3) column chromatographies. As shown in Fig. 1, the final enzyme preparation was ascertained to be homogeneous by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and exhibited β-1,3-xylanase activity by zymography. SDS-PAGE was performed in 12.5% polyacrylamide gel by using the buffer system of Laemmli (10). Zymography was achieved by using glycol β-1,3-xylan (17) according to the method of Beguin (5). The active band coincided in position with the native enzyme. The molecular mass of the purified enzyme from the transformant was 52 kDa, the same as the value determined by SDS-PAGE for the native β-1,3-xylanase from Vibrio sp. strain XY-214, but a little larger than the value (49,050 Da) estimated from the deduced amino acid sequence of β-1,3-xylanase. However, the molecular masses of the recombinant txyA enzyme and the native enzyme were estimated to be 48.0 and 46.4 kDa by Superdex 200 fast-protein liquid chromatography with gel filtration, respectively, and these values were found to be a little smaller than the value of the deduced amino acid sequence. The recombinant enzyme band separated by SDS-PAGE was transferred onto a Clear Blot Membrane-p AE-6660 (Atto, Japan). The sequences of the first five N-terminal amino acids were determined. The sequence (LDGKL) was in a good agreement with that of the native enzyme. As shown in Fig. 2, the recombinant enzyme hydrolyzed β-1,3-xylan to produce several xylooligosaccharides, but did not act on β-1,4-xylan, curdlan (which is a polymer of the repeating units of β-1,3-xylan-linked d-glucose), or carboxymethylcellulose. The latter three polysaccharides were purchased from Sigma Co., Ltd. β-1,3-Xylan used as the substrate was not cleaved by a commercial enzyme (Macerozyme R-10 from Tricoderma; Yakult Co., Ltd.) capable of hydrolyzing β-1,4-xylan. The β-1,3-xylanase from Vibrio sp. strain XY-214 exhibited 40.6% homology with the mannosidase from T. neapolitana (D. A. Yernool, S. Y. Rani, R. F. Sullivan, and D. E. Eveleigh, unpublished data [DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. U58632]). However, neither β-1,3-xylanases from Vibrio sp. strain XY-214 nor the recombinant E. coli showed the α- and β-mannosidase activities (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE (A) and zymography (B) of the native and recombinant β-1,3-xylanases. (A) SDS-PAGE. Proteins (20 μg) were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. (B) Zymography. Both purified enzymes were applied to an SDS-PAGE gel, followed by activity staining with glycol β-1,3-xylan as the substrate. Numbers on the left are molecular masses of the markers. Lanes: 1, molecular mass markers; 2 and 4, native β-1,3-xylanase; 3 and 5, recombinant β-1,3-xylanase.

FIG. 2.

Thin-layer chromatogram of hydrolysis products obtained from several polysaccharides with the recombinant β-1,3-xylanase. Fifty microliters of enzyme solution (0.05 U of β-1,3-xylanase) was added to 50 μl of 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 1% polysaccharide and incubated at 37°C overnight. The hydrolysis products were developed on a silica gel 60 plastic sheet in a solvent of n-butanol–acetic acid–water (10:5:1), and the oligosaccharides were visualized by spraying the plate with a diphenylamine-aniline-phosphate reagent (4). Lanes: 1 and 11, d-xylose; 2, β-1,3-xylanase; 3, β-1,3-xylan; 5, β-1,4-xylan; 7, curdlan; 9, carboxymethylcellulose; 4, 6, 8, and 10, the enzyme plus β-1,3-xylan, β-1,4-xylan, curdlan, and carboxymethylcellulose, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shuichi Karita, Center for Molecular Biology and Genetics, Mie University, for performing sequencing procedures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki T, Araki T, Kitamikado M. Purification and characterization of an endo-β-1,3-xylanase from Vibrio sp. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi. 1988;54:277–281. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araki T, Inoue N, Morishita T. Purification and characterization of β-1,3-xylanase from a marine bacterium, Alcaligenes sp. XY-234. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1998;44:269–274. doi: 10.2323/jgam.44.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araki T, Tani S, Maeda K, Hashikawa S, Nakagawa H, Morishita T. Purification and characterization of β-1,3-xylanase from a marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. XY-214. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1999;63:2017–2019. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey R W, Bourne E J. Colour reagents given by sugars and diphenylamineaniline spray reagents on paper chromatograms. J Chromatogr. 1960;4:206–213. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beguin P. Detection of cellulase activity in polyacrylamide gels using Congo red-stained agar replicas. Anal Biochem. 1983;131:333–336. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biely P. Microbial xylanolytic systems. Trends Biotechnol. 1985;3:286–290. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W P, Matsuo M, Yasui T. Purification and some properties of β-1,3-xylanase from Aspergillus terreus A-07. Agric Biol Chem. 1986;50:1183–1194. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henrissat B, Bairoch A. Updating the sequence-based classification of glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem J. 1996;316:695–696. doi: 10.1042/bj3160695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iriki Y, Suzuki T, Nisizawa K, Miwa T. Xylan of Siphonaceous green algae. Nature. 1960;187:82–83. doi: 10.1038/187082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewin B. Nucleic acid structure. In: Lewin B, editor. Genes VI. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marchuk D, Drumm M, Saulino A, Collins F S. Construction of T-vectors, a rapid and general system for direct cloning of unmodified PCR products. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;19:1154. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDowell R H. Chemistry and enzymology of marine algal polysaccharides. 1967. pp. 88–96. , 134–137. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mong K K Y, Tan L U L, Saddler J N. Multiplicity of β-1,4-xylanase in microorganisms: functions and applications. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:305–317. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.3.305-317.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohmiya K, Sakka K, Karita S, Kimura T. Structure of cellulase and their application. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 1997;14:365–414. doi: 10.1080/02648725.1997.10647949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perlman D, Halvorson H O. A putative signal peptidase recognition site and sequence in eukaryotic and prokaryotic signal peptides. J Mol Biol. 1983;167:391–409. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senju R, Okimasu S. Studies on chitin. Part I. On the glycolation of chitin and the chemical structure of glycol chitin. Nippon Nogeikagaku Kaishi. 1950;23:432–437. . (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Somogyi M. Notes on sugar determination. J Biol Chem. 1952;195:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timell T E. Recent progress in the chemistry of wood hemicelluloses. Wood Sci Technol. 1967;1:47–76. [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Heijne G. A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaura I, Matumoto T, Funatsu M, Murai E. Purification and some properties of endo-β-1,3-xylanase from Pseudomonas sp. PT-5. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:921–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]