Abstract

Background

Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) cardiac MRI can be used to detect post-ablation atrial scar (PAAS) but its reproducibility and reliability in clinical scans across different magnetic flux densities and scar detection methods is unknown.

Methods

Patients (n=45) having undergone two consecutive MRIs (three months apart) on 3T and 1.5T scanners were studied. We compared PAAS detection reproducibility using four methods of thresholding: simple thresholding, Otsu thresholding, 3.3 standard deviations (SD) above blood pool (BP) mean intensity, and image intensity ratio (IIR). We performed a texture study by dividing the left atrial wall intensity histogram into deciles and evaluated the correlation of the same decile of the two scans as well as to a randomized distribution of intensities, quantified using Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC).

Results

The choice of scanner did not significantly affect the reproducibility. The scar detection performed by Otsu thresholding (DSC of 71.26±8.34) resulted in better correlation of the two scans compared to the methods of 3.3 SD above BP mean intensity (DSC of 57.78±21.2, p<0.001) and IIR above 1.61 (DSC of 45.76±29.55, p<001). Texture analysis showed that correlation only for voxels with intensities in deciles above the 70th percentile of wall intensity histogram was better than random distribution (p<0.001).

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that clinical LGE-MRI can be reliably used for visualizing PAAS across different magnetic flux densities if the threshold is greater than 70th percentile of the wall intensity distribution. Also, atrial wall based thresholding is better than BP based thresholding for reproducible PAAS detection.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, LGE-MRI, Radiofrequency energy, Catheter ablation, Lesion assessment, Scar Reproducibility

1. Introduction

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is an effective treatment for atrial fibrillation (AF) 1. However, not all targeted areas result in scar formation 2, 3. Re-established electrical connection of pulmonary veins to the atria after pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) is thought to be, at least in part, due to the presence of gaps in ablation lesion sets4. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) cardiovascular MRI can help in non-invasive detection and quantification of ablation scar due to the slow washout kinetics of gadolinium in scar tissue5.

The reproducibility of clinical LGE-MRI detecting atrial scar has not been verified quantitatively in clinical scans. Only recently, we have seen efforts to optimize imaging and test reproducibility under controlled conditions 6. Many factors can affect the scar distribution that is derived from image intensity in LGE-MRI scans 7.

Post atrial ablation scar (PAAS) detection is challenging due to multiple reasons including artifacts related to respiratory and cardiac motion, the spatial resolution of the MRI used for visualizing the relatively thin atrial wall, contrast variations due to inversion time and signal to noise ratio (SNR)7. The threshold level set to define the scar tissue is one of the factors that can highly influence the extent and the pattern of PAAS. Different methods have been proposed by different groups for PAAS detection but the reproducibility of these methods have not been evaluated and compared 8-10.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether LGE-MRI is reproducible over different image intensity values, different scanner magnetic flux densities, and finally to compare four common scar detection methods for reproducible detection of post ablation left atrial scar in clinical LGE-MRI scans. Different threshold levels using different techniques with different magnetic flux density scanners were used to identify scar tissue in two consecutive post-ablation LGE-MRI sessions. A texture study was done to check the correlation of the scans over different image intensity values and to see if there is a cut-off threshold below which LGE-MRI is not reproducible.

Methods

Patient Population

Patients who underwent AF radiofrequency ablation between May 2007 to August 2017 at the University of Utah Hospital with two post ablation cardiac LGE-MRIs three months apart with the first one done three months after ablation were selected for this retrospective study. Exclusion criterion were poor image quality in any of the MRIs or any cardiac intervention between the ablation and the second MRI. We included 45 patients (Male: 34, Female: 11, Age: 69.2±12.0) in our study. The baseline characteristics of all the 45 patients in the study are listed in Table 1 in the supplementary materials. The selected patients had received two consecutive MRIs performed with varying magnetic flux density. Of the 45 patients, 15 had both scans on 3 T, 15 had both scans on 1.5 T and another 15 had a 1.5 T as well as a 3 T MRI. All the patients underwent RFA for PVI with or without additional posterior or anterior wall ablation. The two consecutive MRI scans were approximately three months apart, with the first MRI done three months (120 ±65 days) post-ablation and the second MRI done at least three months after the first scan (162 ±98 days) with no cardiac intervention in between. Patients with bad image quality were excluded from the study (19 out of 64 of the initially selected patients had at least one inferior quality image). Prior studies have shown that post ablation atrial wall changes or remodeling is completed in the first three months and hence the design to compare studies at 3 and 6 months 11, 12 . This retrospective study was done under study protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Utah. No informed consent was required from the patients for this study.

MRI Acquisition

MRI scans were acquired on 1.5 or 3 Tesla clinical MRI scanners (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) approximately 15 minutes after injection of contrast agent (0.1 mmol/kg, Multihance, Bracco Diagnostic Inc., Princeton, NJ) using an institutional standard inversion recovery prepared, 3-D gradient echo pulse sequence described previously in detail during sinus rhythm 2. All LGE-MRIs were obtained with acquired voxel size of 1.25 mm x 1.25 mm x 2.5 mm and reconstructed to voxel spacing of 0.625 mm x 0.625 mm x 1.25 mm.

Left Atrial Segmentation

Left atrial segmentations were performed manually by trained raters who processed the LGE-MRIs using Seg3D software (Scientific Computing and Imaging Institute, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT) as described previously 2, 3. The segmentation was edited manually to cover the whole wall in each slice in different areas accounting for atrial wall with varying thickness. The two different scans for each patient were segmented by different raters, each with more than 2 years of experience. All the segmentations were checked at the end by a more experienced rater with more than 7 years of experience to make sure that segmentations were consistent and accurate. The left atrial wall was later masked out on the MRIs for further analysis (Figure 1A-B in supplementary material show the process).

In theory, the intensity histogram of homogenous tissue in an MRI with some noise can be modeled with a Rician distribution 13. Using MATLAB and Statistics Toolbox (Release 2016a, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, United States), we removed the outliers from the wall intensity histograms (lowest and highest 1 percentile) and normalized the intensity values to be in the range of 0 to 1, fitted Rician distributions on the intensity histograms and calculated mean intensity value, skewness and standard deviation (SD) of the distributions.

PAAS Segmentation

Scar thresholding was done by the following four methods:

Simple thresholding (from 60th to 90th percentile in increments of 1 percentile),

A previously reported histology-validated threshold of 3.3 standard deviations (SD) above blood pool (BP) mean intensity 15.

BP based Image intensity ratio (IIR) method with thresholds above 1.61 indicating atrial scarring 16.

The thresholding was done based on the image intensity distribution of the entire segmented left atrial wall (not separately for each slice). Figure 1 in the supplementary material shows the segmentation and thresholding process for one slice.

Reproducibility of pixel intensities for the entire distribution

In order to study the correlation of all the wall voxels with different intensity values, we did a texture analysis. Texture analysis allowed us to determine if voxel intensities are reproducible for the entire distribution ranging from lower (darker) to higher intensities (brighter). It also allowed us to determine if there is a threshold of intensity for scar, only above which the scar is reproducible. We divided the intensity histogram into 10 segments with an equal number of voxels (10 percentile segments or deciles). For each study, the voxels in the same decile were marked as scar in both the first and second scans. Then the correlation of the two scans was checked. This was repeated for all the deciles one decile at a time and different scanner type based groups.

We then set to determine the correlation of intensity deciles on scans with randomized intensity distributions. This helped us to get a quantitative measure of baseline DSC with voxel intensities being randomly distributed or noise. To do this, we randomized the locations of the voxel intensities over the segmented wall and again marked the voxels one decile at a time based on the signal intensity in both the scans and checked their correlation. This was then repeated for each different scanner type based group.

Checking the Correlation of PAAS or Marked Deciles in Two Consecutive MRIs

1. Registration of the 3D Atrial Wall Geometries

Using Matlab, the 3D atrial wall segmentation from the second MRI was registered to the atrial wall segmentation from the first MRI with iterative closest point (ICP) along with affine registration methods. The registration was blinded to the scar location and pattern (Figure 2 in the supplementary material). Minor variations in the two segmentations around the pulmonary veins and the mitral valve were excluded by registering with this method.

For comparing the scar or healthy tissue voxels after registration, we used a cut-off distance of 1.25 mm. If the voxels of the same classification (scar and non-scar) of the first and second scan were closer than 1.25 mm after the registration, we assumed that they matched. We chose 1.25 mm as our threshold because the MRI was acquired with this in-plane resolution.

2. Sorensen Dice Similarity Coefficient as a Comparison Criterion

Sorensen Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) is a well-accepted method of assessing the correlation of images 17. DSC is specifically developed for dealing with issues of high accuracy when there are much lower number of scar voxels, as in this situation 18. DSC was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

Where Nms is the number of matched scar (or marked) pixels in the two scans, Ns1 and Ns2 are the total number of scar (or marked) voxels in the first and second scan respectively.

Statistical Analyses

Different variables are expressed as mean ± SD and categorical data as percentiles. For the texture analysis, due to the paired design and approximate normally distributed outcome, a paired student t-test was used to compare the mean values of DSC across the 10 groups of deciles between real and randomized intensity distribution groups. All analysis in this report was performed using R-Studio 3.4.

2. Results

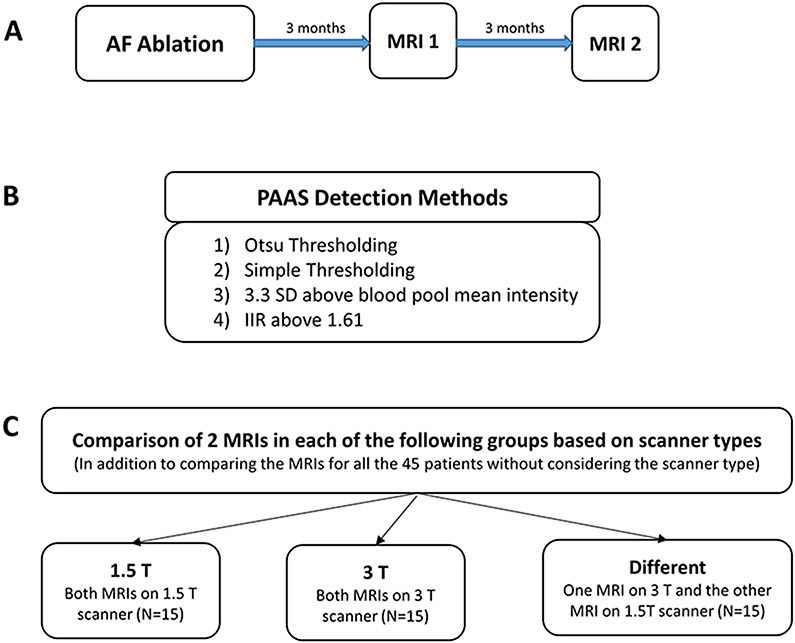

Patients (n=45) with two consecutive post atrial ablation scans were included in this study. The atrial volume was found to be similar in both the scans. The average volume based on first scans was 85.69±27.45 mm3 and it was 84.07±26.33 mm3 based on second scans. The summary of this study including patient selection and implemented PAAS detection methods is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of Patient Selection and implemented PAAS detection Methods. A) MRI acquisition timeline. B) Different PAAS detection Methods. C) Comparison of detected PAAS for selected patients based on scanner magnetic flux density groups.

The image intensity histogram was approximately Gaussian with a skewness towards the higher image intensities for both the scans for all patients. Figure 3 in the supplementary material shows the typical normalized histogram distribution of the two MRIs for a random patient. Table 1 shows the average skewness, mean intensity and standard deviation (SD) for the intensity histograms of both scans for all the patients categorized with the scanner type, which was quite similar for the first and second scans irrespective of the type of scanner. However, the measured differences of the mean intensity values of the first and second scans were significantly larger when both scans were done on a 3T scanner compared to when scans were done on different scanners.

Table 1.

Analysis of signal intensity histograms for all scanner type based groups.

| First Scan | Second Scan | Difference in First and Second Scans |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Skewness | |||

| 1.5 T (N=15) | 0.36 ± 0.22 | 0.51 ± 0.27 | 0.35 ± 0.35 |

| 3 T (N=15) | 0.41 ± 0.31 | 0.24 ± 0.37 | 0.28 ± 0.26 |

| Different Scanners (N=15) | 0.44 ± 0.34 | 0.43 ± 0.29 | 0.20 ± 0.18 |

| Mean of the Distribution | |||

| 1.5 T (N=15) | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 0.04 ± 0.03 |

| 3 T (N=15) | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.06 ± 0.04 |

| Different Scanners (N=15) | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 0.03 ± 0.03 |

| SD of the Distribution | |||

| 1.5 T (N=15) | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| 3 T (N=15) | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| Different Scanners (N=15) | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| P-Value for the differences of measured parameters in first and second scans between the following groups of scanners: | |||

| Skewness | Mean of the Distribution | SD of the Distribution | |

| Both scans on 1.5T vs. both scans on 3T | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.33 |

| Both scans on 3T vs. different scanners used for each patient | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.33 |

| Both scans on 1.5T vs. different scanners used for each patient | 0.74 | 0.41 | 0.93 |

Correlation of PAAS

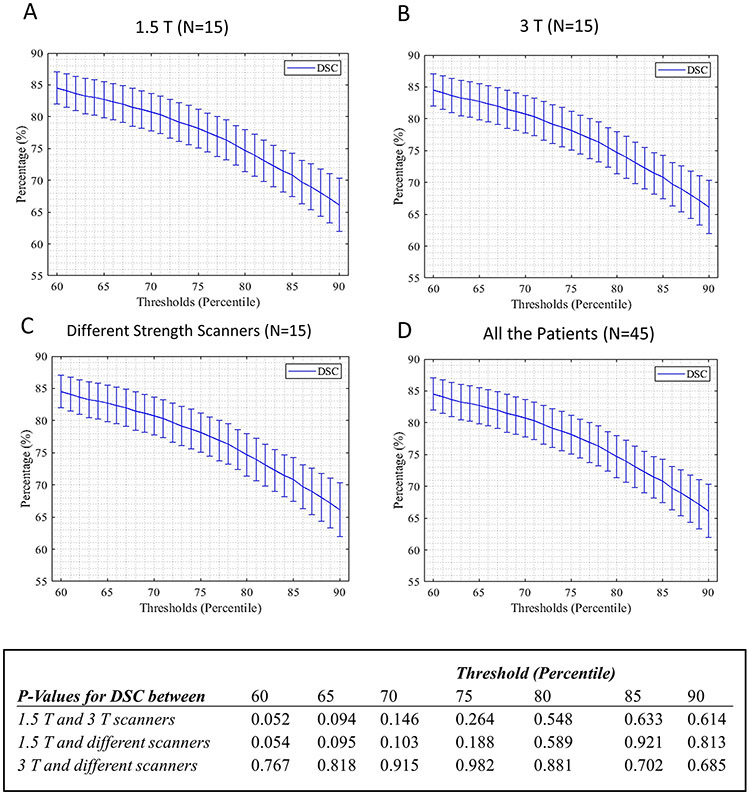

For all scanner type based groups, DSC decreased with corresponding increasing cut-off values (Figure 2A-D). The DSC values for the different PAAS detection methods of Otsu thresholding, 3.3 SD above BP mean intensity value and IIR above 1.61 are reported in Table 2 for all scanner based groups. The mean thresholds for scar detection based on Otsu thresholding for all patients for first and second scans were 75.00±5.89 and 75.53±7.12 percentiles respectively. For the simple thresholding method, the calculated DSC values for the same range of selected thresholds by Otsu method were high and very similar to Otsu thresholding. However, based on the calculated P- values for DSC in Table 2, Otsu thresholding is significantly better than the third and fourth methods of using the threshold of 3.3 SD above BP mean intensity value or IIR above 1.61. The DSC values based on threshold of 3.3 SD above BP mean intensity was also significantly better than DSC values for IIR above 1.61 for all scanner types other than both scans on 1.5 T as shown in table 2. Also, the choice of scanner type did not change the PAAS detection reproducibility as reported by P-values calculated for DSC as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2 for all four PAAS detection methods. Figure 3 shows an example of scar distribution based on the two consecutive MRIs for threshold cut-offs of the 70th, 80th and 90th percentiles, Otsu thresholding and the two BP based PAAS detection methods.

Figure 2.

DSC using simple thresholding method with thresholds in the range of 60th to 90th percentile for different scanner type based groups (A, B, C) and all the patients together (D) along with the calculated P-Values for average DSCs between different scanner type based groups in selected thresholds.

Table 2.

Reported DSC and P values for calculated DSC using the thresholds based on the three PAAS detection methods for the different groups of scanners. The reported thresholds are also an indicator of the amount of scar (“100 minus threshold” being the scar percentile).

| 1.5 T (N=15) | 3 T (N=15) | Different (N=15) | All (N=45) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otsu Thresholding | ||||

| DSC | 73.56±5.22 | 69.43±9.99 | 70.79±9.32 | 71.26±8.34 |

| Scan1 Thresholds (Percentile) | 74.33±6.30 | 74.53±6.47 | 76.13±5.29 | 75.00±5.89 |

| Scan2 Thresholds (Percentile) | 77.60±7.46 | 72.40±7.68 | 76.60±5.67 | 75.53±7.12 |

| P-Values for DSC between | 1.5 T and 3 T | 0.15 | ||

| 1.5 T and different scanners | 0.22 | |||

| 3 T and different scanners | 0.68 | |||

| 3.3 SD above BP mean | ||||

| DSC | 64.03±21.00 | 54.56±24.94 | 54.76±19.08 | 57.78±21.23 |

| Scan1 Thresholds (Percentile) | 77.00±11.63 | 87.27±8.67 | 85.87±10.11 | 83.38±10.86 |

| Scan2 Thresholds (Percentile) | 76.60±23.02 | 91.27±5.59 | 89.93±5.01 | 85.93±15.04 |

| P-Values for DSC between | 1.5 T and 3 T | 0.34 | ||

| 1.5 T and different scanners | 0.19 | |||

| 3 T and different scanners | 0.98 | |||

| IIR more than 1.61 | ||||

| DSC | 56.11±30.97 | 35.07±27.52 | 43.04± 27.49 | 45.76±29.55 |

| Scan1 Thresholds (Percentile) | 72.84±21.54 | 90.01±9.12 | 86.53±15.61 | 83.13±17.84 |

| Scan2 Thresholds (Percentile) | 76.00±23.54 | 93.19±8.33 | 91.91±7.91 | 87.03±17.02 |

| P-Values for DSC between | 1.5 T and 3 T | 0.06 | ||

| 1.5 T and different scanners | 0.22 | |||

| 3 T and different scanners | 0.48 | |||

| P-Values for Otsu and 3.3SD above BP mean | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| P-Values for Otsu and IIR above 1.61 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| P-Values for IIR based and 3.3SD above BP mean | 0.38 | 0.008 | 0.02 | <0.001 |

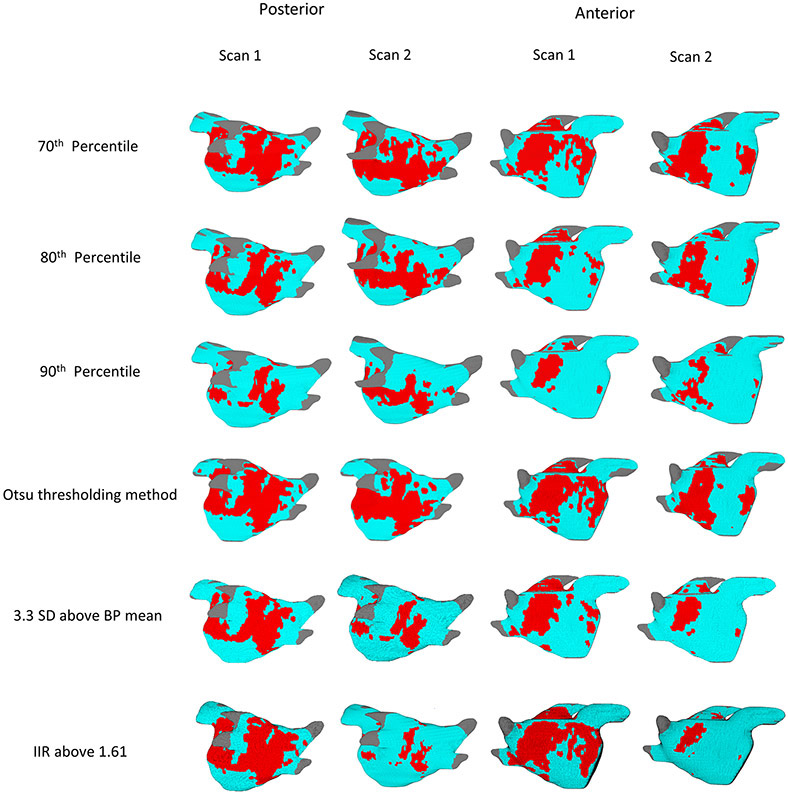

Figure 3.

Posterior and anterior views of both the first and second scans of a patient with the scar patterns generated with 70th, 80th and 90th percentile threshold levels, Otsu thresholding and BP based PAAS detection methods. Scar (voxels with image intensity values higher than the selected threshold) is shown in red.

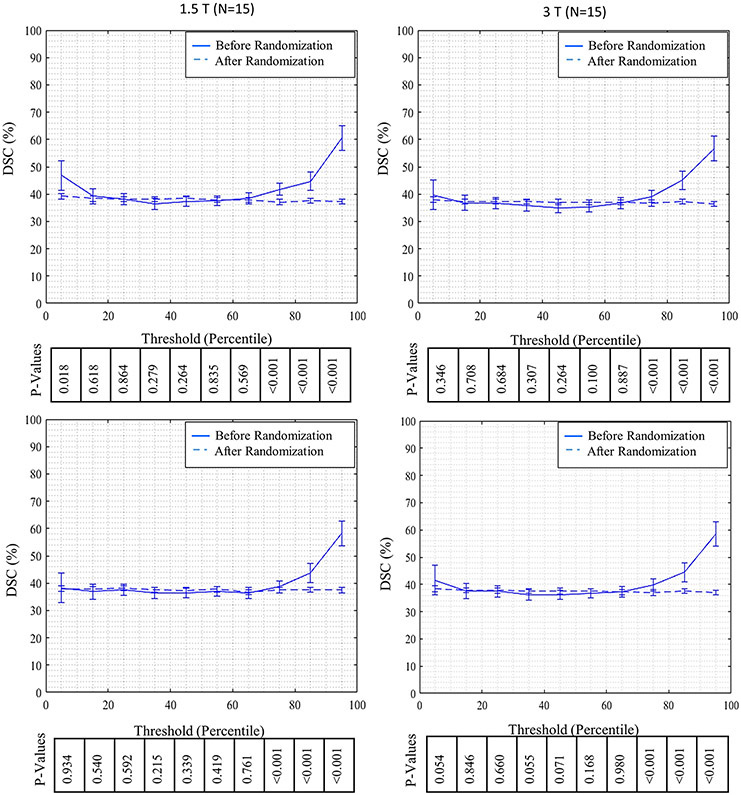

Reproducibility of the Atrial Wall Imaging without Thresholding for Scar Detection

The calculated DSC over different deciles of wall intensity histogram for real and randomized distribution of intensities are shown in Figure 4. For all scanner type based groups, DSC for the real intensity distribution is mostly flat until the 70th percentile and then increases progressively for higher deciles. For randomized intensity distribution, DSC is similar for the entire range of deciles. The mean values for DSC in real distributions are significantly better than mean values for DSC in randomized distribution for deciles staring at the 70th percentile and above as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of DSC for real and randomly distributed wall pixel intensities per decile for all the patients over ten decile segments of image intensity distribution along with reported P-values based on different scanner type groups (A to C), and for all the patients together (D).

3. Discussion

Main Findings

Scar formation after ablation has been demonstrated to have an important role in predicting the recurrence of AF 3. Noninvasive detection of PAAS using LGE-MRI is a recent advancement 5, 7. Different labs have developed different algorithms for scar segmentation 20, and compared their accuracy and efficiency with each other or with voltage mapping. However, these comparisons are based on the same LGE-MRI scans. Also, thresholds used for scar determination continue to be quite variable among different groups with no measure of how the different thresholds affect reproducibility.

In this study, we examined the reproducibility of post ablation clinical LGE-MRI scans performed three months apart with the additional goal of quantitatively assessing the reproducibility using different scar determination algorithms. The main findings are: (1) post RF ablation, atrial scar detection is highly reproducible from one scan to the next over a three month span (2) the reproducibility of LGE-MRI for thresholds less than the 70th percentile of the wall intensity distribution is no better than the reproducibility of a random distribution and (3) using only wall intensity based PAAS detection methods result in better correlation and reproducibility than using BP based methods.

Atrial wall based thresholding methods (same percentiles, Otsu thresholding) generated scar maps in our study that were reproducible with high DSC values. However, Otsu might be a better PAAS detection method because of the singular unique threshold that it detects compared to simple thresholding.

There are many explanations that account for the small differences in the scar pattern in the two scans. An important consideration is image quality. LGE-MRI helps to identify scar by displaying the accumulation of gadolinium-based contrast agent in the scarred regions. The scarred regions appear bright (increased signal intensity) on T1-weighted images compared to normal atrial tissue 7. Thus, as with all LGE-MRI studies, choice of inversion time is critical to image quality, which may have an effect on the appearance of scars 21. If the inversion time is shorter than optimal, as there are still some contrast residuals, normal myocardium appears grey. This may make it difficult to tell contrast residuals from scar. If the inversion time is longer than the optimal inversion time, the image contrast is reduced. In both cases, assessment of scar size and pattern may be inaccurate. Furthermore, the image quality of LGE-MRI is inherently affected by cardiac and respiratory motion. Motion can cause image blurring. In addition, the incorporated noise during image acquisition will influence the scar patterns. The atrial wall is a relatively thin structure and we acquire these images at 1.25 mm resolution. Some of the pixels are bound to include the BP and affect the signal intensity leading to small discrepancies.

Another reason for small differences in scar pattern in serial cardiac MRI exams may be the volumetric changes associated with structural remodeling of left atrium (LA) after restoration of sinus rhythm22. This may make both the scar pattern and the 3D atrial wall geometries reconstructed from the two consecutive scans slightly different. Most of the atrial wall remodeling after ablation happens during the first three months of the blanking period 11 and changes in scar after that are small12. To establish the best possible correspondence between the two wall segmentations, we performed a non-rigid ICP registration, which helped in minimizing the effect of structural remodeling on our calculation of the scar areas.

Different research groups use various approaches to define the scar detection threshold. These approaches include manually defining a threshold, defining a threshold relative to the BP, or defining a threshold relative to the normal myocardium 20. All of these methods have limitations. Otsu thresholding or simple thresholding based on just wall intensity histogram are not prone to BP intensity or the selected inversion time. These two methods showed high DSC, even higher than using the 3.3 SD above the mean BP intensity cut-off and IIR above 1.61.

LGE-MRI by definition shows higher signal intensity in areas of dense scarring where there is accumulation of gadolinium. In order to check the correlation of voxels with different intensity values over the segmented atrial wall, we divided the wall intensity histogram into deciles and checked the correlation of same marked deciles in the two scans. Also, in order to determine the lower limit of signal intensity below which the pixels cannot be reliably classified as a scar, or to see if that limit even existed, we also checked the correlation of deciles after randomizing the locations of different intensity values over the segmented walls. We found that in these images there was a very clear cut-off at the 70th percentile of signal intensity. This result suggests that thresholds below the 70th percentile of signal intensity should not be used for scar determination after left atrial ablation because pixels below that threshold show random variations in signal intensities due to inherent noise in the signal acquisition. More importantly, above the 70th percentile cut-off, signal intensity is very distinct from noise and hence can be reliably attributed to the presence of gadolinium in the scarred region. This to some extent depends on the amount of left atrial scar and if there is more than 30% scar in the LA then the cut off might be lower. In general, 30% scar in the LA seems to be a generous amount after percutaneous left atrial ablation.

Study Limitations

One of the limitations of our study is the small sample size (45 subjects). The second limitation is that we did not include LGE-MRI scans with inferior quality. This was done to eliminate significant noise artifact. We were looking for the best case scenario to determine the degree of reliability of scar determination and limits of thresholding. This might make our results less applicable to images with worse image quality that might be affected by cardiac and respiratory motion. Image intensity is more inhomogeneous at 3T than at 1.5T and that can also affect comparisons across field strengths. Variability in segmentation can also affect these measurements but they are expected to be small and distributed across the scans.

4. Conclusion

Generally, lesion assessment using post ablation LGE-MRI is shown to be relatively reproducible. However, it is only reliable for detection of regions with high intensity values. Of the four scar detection methods that we used in this study, Otsu thresholding and simple thresholding methods that use only wall intensity histogram resulted in the better correlation of the scans compared to the other methods that rely on the intensity histogram of BP. Otsu thresholding may be a better PAAS detection method for the unique threshold that it offers for reproducible scar detection. The choice of clinical scanner (1.5 T or 3 T) does not affect the reproducibility of PAAS detection making it possible to compare studies done with different scanners.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This study was partly funded by NIH grant K23 HL115084 to Ravi Ranjan. Ravi Ranjan is currently supported by NIH grant R01HL142913 and is a consultant to Medtronic, Biosense Webster and Abbott. He has or has recently had research grants from Medtronic, St Jude and Biosense Webster.

Abbreviations:

- LGE

Late gadolinium enhancement

- PAAS

Post-ablation atrial scar

- DSC

Dice Similarity Coefficient

- BP

Blood pool

- RFA

Radiofrequency ablation

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- PVI

Pulmonary vein isolation

- SD

Standard deviation

- SNR

Signal to noise ratio

- LA

Left atrium

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, Garrigue S, Le Mouroux A, Le Metayer P and Clementy J. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parmar BR, Jarrett TR, Burgon NS, Kholmovski EG, Akoum NW, Hu N, Macleod RS, Marrouche NF and Ranjan R. Comparison of left atrial area marked ablated in electroanatomical maps with scar in MRI. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2014;25:457–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parmar BR, Jarrett TR, Kholmovski EG, Hu N, Parker D, MacLeod RS, Marrouche NF and Ranjan R. Poor scar formation after ablation is associated with atrial fibrillation recurrence. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2015;44:247–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma A, Kilicaslan F, Pisano E, Marrouche NF, Fanelli R, Brachmann J, Geunther J, Potenza D, Martin DO, Cummings J, Burkhardt JD, Saliba W, Schweikert RA and Natale A. Response of atrial fibrillation to pulmonary vein antrum isolation is directly related to resumption and delay of pulmonary vein conduction. Circulation. 2005;112:627–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGann CJ, Kholmovski EG, Oakes RS, Blauer JJ, Daccarett M, Segerson N, Airey KJ, Akoum N, Fish E, Badger TJ, DiBella EV, Parker D, MacLeod RS and Marrouche NF. New magnetic resonance imaging-based method for defining the extent of left atrial wall injury after the ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chubb H, Karim R, Roujol S, Nuñez-Garcia M, Williams SE, Whitaker J, Harrison J, Butakoff C, Camara O and Chiribiri A. The reproducibility of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging of post-ablation atrial scar: a cross-over study. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2018;20:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters DC, Wylie JV, Hauser TH, Kissinger KV, Botnar RM, Essebag V, Josephson ME and Manning WJ. Detection of pulmonary vein and left atrial scar after catheter ablation with three-dimensional navigator-gated delayed enhancement mr imaging: initial experience 1. Radiology. 2007;243:690–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao Q, Milles J, Zeppenfeld K, Lamb HJ, Bax JJ, Reiber JH and van der Geest RJ. Automated segmentation of myocardial scar in late enhancement MRI using combined intensity and spatial information. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2010;64:586–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oakes RS, Badger TJ, Kholmovski EG, Akoum N, Burgon NS, Fish EN, Blauer JJ, Rao SN, DiBella EV and Segerson NM. Detection and quantification of left atrial structural remodeling with delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2009;119:1758–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennemuth A, Seeger A, Friman O, Miller S, Klumpp B, Oeltze S and Peitgen H-O. A comprehensive approach to the analysis of contrast enhanced cardiac MR images. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2008;27:1592–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamashita K, Kwan E, Kamali R, Ghafoori E, Steinberg BA, MacLeod RS, Dosdall DJ and Ranjan R. Blanking period after radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation guided by ablation lesion maturation based on serial MR imaging. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2020;31:450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badger TJ, Oakes RS, Daccarett M, Burgon NS, Akoum N, Fish EN, Blauer JJ, Rao SN, Adjei-Poku Y, Kholmovski EG, Vijayakumar S, Di Bella EV, MacLeod RS and Marrouche NF. Temporal left atrial lesion formation after ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gudbjartsson H and Patz S. The Rician distribution of noisy MRI data. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 1995;34:910–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Level Otsu N A threshold selection method from gray-level histogram. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1979;9:62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison JL, Jensen HK, Peel SA, Chiribiri A, Grøndal AK, Bloch LØ, Pedersen SF, Bentzon JF, Kolbitsch C and Karim R. Cardiac magnetic resonance and electroanatomical mapping of acute and chronic atrial ablation injury: a histological validation study. European heart journal. 2014;35:1486–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khurram IM, Beinart R, Zipunnikov V, Dewire J, Yarmohammadi H, Sasaki T, Spragg DD, Marine JE, Berger RD and Halperin HR. Magnetic resonance image intensity ratio, a normalized measure to enable interpatient comparability of left atrial fibrosis. Heart rhythm. 2014;11:85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crum WR, Camara O and Hill DL. Generalized overlap measures for evaluation and validation in medical image analysis. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2006;25:1451–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajchl M, Yuan J, White JA, Ukwatta E, Stirrat J, Nambakhsh CM, Li FP and Peters TM. Interactive hierarchical-flow segmentation of scar tissue from late-enhancement cardiac MR images. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2014;33:159–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landis JR and Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. biometrics. 1977:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karim R, Housden RJ, Balasubramaniam M, Chen Z, Perry D, Uddin A, Al-Beyatti Y, Palkhi E, Acheampong P, Obom S, Hennemuth A, Lu Y, Bai W, Shi W, Gao Y, Peitgen HO, Radau P, Razavi R, Tannenbaum A, Rueckert D, Cates J, Schaeffter T, Peters D, MacLeod R and Rhode K. Evaluation of current algorithms for segmentation of scar tissue from late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance of the left atrium: an open-access grand challenge. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taclas JE, Nezafat R, Wylie JV, Josephson ME, Hsing J, Manning WJ and Peters DC. Relationship between intended sites of RF ablation and post-procedural scar in AF patients, using late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:489–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsan NA, Tops LF, Holman ER, Van de Veire NR, Zeppenfeld K, Boersma E, van der Wall EE, Schalij MJ and Bax JJ. Comparison of left atrial volumes and function by real-time three-dimensional echocardiography in patients having catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with persistence of sinus rhythm versus recurrent atrial fibrillation three months later. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:847–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.