Abstract

Policy Points.

Income is a fundamental cause of health across the life course. To address income‐related health inequities, we need a set of overlapping and complementary policy approaches rather than focusing on a single policy.

During their lives, individuals inhabit different roles with regard to their ability to earn wages, and at any given time, only about 50% of the US population are expected to earn wages, while the rest (e.g., children, older adults, those who are disabled, unemployed, students, and/or caregivers) are not.

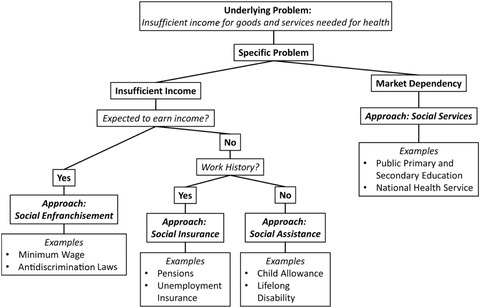

Three key “branch points” for designing policy approaches to address income‐related health inequity are (1) should the needed good or service be obtained on the market? (2) do policy beneficiaries currently earn income? and (3) have policy beneficiaries earned income previously? The responses to these questions suggest one of four policy approaches: social services, social enfranchisement, social insurance, or social assistance.

Social conditions give rise to material realities. the social conditions structuring access to those resources “necessary to lower the risk of developing a disease, or minimize the consequences of a disease once it occurs” can be thought of as the fundamental causes of health. 1 , 2 In this characterization, income is an archetypical example of a fundamental cause.

Though it is by no means the only factor, achieving and maintaining health requires sufficient consumption of particular goods and services across the life course. These goods and services include nutritious food, safe housing, education, and health care. In the United States’ political economy, these goods and services are typically obtained on the market, which has made income a principal driver of health as well as a fundamental cause of many diseases through many mechanisms. Furthermore, racism is a fundamental cause of disease in its own right. 3 A common manifestation of structural racism in the United States is lower income among those persons identifying as Black, Hispanic, or Indigenous. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 This makes income one, though certainly not the only, explanation for the unjust health outcomes often experienced by individuals from minoritized racial and ethnic groups.

Because income is both closely related to health outcomes and eminently modifiable, it is a natural target for policies and programs that seek to improve health equity. Owing to reverse causation—that poor health reduces one's ability to earn income, in addition to low income leading to poor health—the association between income and poor health may be impossible to eliminate fully. There is, however, evidence that the health of those with lower incomes varies considerably across policy contexts, suggesting that this relationship can be modified. For example, whereas the relationship between income and life expectancy is mostly linear in the United States, rising steadily as income rises, in Norway life expectancy rises sharply in the lower range of income before leveling off. 8 This means that persons with lower incomes in Norway have much greater life expectancy than do persons with lower incomes in the United States, approximately three years more at the 20th income percentile. 8

Evidence about the aggregate relationship between income and health, however, may not be very informative when confronting a specific problem. The broad array of health outcomes plausibly influenced by income, coupled with the substantial range of policies that might address these issues, can make it difficult for those concerned about income‐related health inequity to know where to start when seeking solutions.

In this perspective, I propose a cohesive framework that can be used to think through policy approaches to address income‐related health inequity. This framework draws from both a conceptual perspective on the relationship between income and health known as fundamental cause theory and from life course epidemiology to help understand why income security throughout one's life is vital to health equity. This framework also incorporates an empirical understanding of income types and the distinct “roles” that people assume over their lifetime. 9

My proposed framework emphasizes three questions for designing policy approaches to address income‐related health inequity: (1) should the needed good or service be obtained on the market? (2) are those the policy is meant to help expected to be earning income presently? and (3) are those the policy is meant to help likely to have earned income previously? The responses to these questions for the particular situation in which the investigator or policymaker is interested are “branch points” leading to one of four main policy approaches, based on the specific problems that each approach is intended to solve: social services, social enfranchisement, social insurance, and social assistance.

After presenting this framework, I contrast it with common alternative approaches—means‐tested programs and universal basic income—that are not grounded in an understanding of the roles people inhabit and, for this reason, present a number of difficulties. The goal of this paper is to provide a tool for policy analysis, as well as illustrations of specific policies. However, the goal is not to argue for a specific policy, show how to implement it, or review the evidence of a policy's effectiveness for a particular health outcome. Nor is this a review of clinical programs meant to help manage specific conditions among individuals with health‐related social needs borne of low income, such as food insecurity or housing instability. 10 Instead, the goal is to offer an approach for those concerned about income‐related health inequities to consider the many policy options that might be relevant to the specific situation they seek to address.

Income and Health

The literature describing the relationship between income and health is voluminous, and it would be impossible to review it in depth here. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 A striking finding is the existence of a gradient between income and health. 11 This means that lower income is associated not only with worse health below a certain threshold, such as a poverty level, but even at income levels substantially above poverty. Another striking finding is the variety of associations between lower income and poor health. This variety includes both categories of diseases with widely varying pathophysiologic mechanisms (e.g., cardiometabolic conditions, malignancies, mental health) and conditions that occur at different times across the life course (e.g., infancy and childhood, early adulthood, older age). Beyond noting these findings, however, it is worth thinking about why the relationship between income and health outcomes, almost any outcome, is so strong.

The fundamental cause theory of disease offers one explanation. 1 , 2 This theory argues that the fundamental causes of disease lie in the access to, or the lack of, “resources that can be used to avoid risks or to minimize the consequences of disease once it occurs.” 1 The flexibility of income allows one to use it to maintain health in very different situations, no matter the specific health risks or particular mechanisms. For example, at the turn of the 20th century, when infectious respiratory diseases such as tuberculosis were major causes of death in the United States, higher incomes enabled less crowded and better ventilated housing that lowered the risk of being exposed. 17 At the turn of the 21st century, when cardiometabolic conditions are major causes of death, higher incomes can be used for healthier food and exercise opportunities to avoid developing diabetes or hypertension, or better treatments to avoid complications if these conditions do develop. 18 Whatever the major causes of death are at the turn of the 22nd century, higher incomes are likely to help avoid them as well. If there was any doubt about the status of income as a fundamental cause of health, the predictable, and predicted, better outcomes of those with higher incomes during the COVID‐19 pandemic—a novel disease—should provide the needed proof. 19

It is also important to understand the relationship between income and health within a life course perspective. The life course perspective identifies key ways that exposures to health risks at one point in time may influence health outcomes for the rest of an individual's life. 20 These include critical periods (developmental windows during which an individual's experience at that time affects health at a later time, regardless of subsequent experiences), path dependence (health trajectories that are set in motion by a particular experience), and cumulative effects in which experience at one point in time compounds with other experiences to produce a given health outcome. 20 This means that material deprivation at any time in one's life may cause irreversible health effects. Thus, to promote health equity, we must be concerned with income security across the life course. Furthermore, given income's role as a fundamental cause, we cannot rely on single “silver‐bullet” programs to address income‐related health inequities. Instead, we need a set of overlapping and complementary policies to address the varying ways that income can affect health.

Types of Income

When considering policies to address income‐related health inequities, it is helpful to distinguish between two types of income: factor income and transfer income. 21 Factor income refers to income that comes from work (such as wages) or a person's assets (such as land, real estate, or capital investments): the “factors” of production. Transfer income refers to income received without the exchange of goods or services, such as government payments or support within families. Note that both factor and transfer incomes are part of particular policy arrangements and legal structures, and thus both types of income represent ways to distribute the national income via government policy.

For policymakers, an important distinction is whether persons are likely to have access to both factor and transfer income, or only transfer income. We can informally distinguish “workers” (those with at least some factor income) from “nonworkers” (those with only transfer income), but this may be inaccurate because factor income may not come from work, and those without factor income may nevertheless be engaging in unpaid labor.

Understanding that some individuals may have access to both factor and transfer income, whereas others may have access only to transfer income, is important when designing policies. We also must recognize that whether one has access to both factor and transfer income, versus transfer income alone, changes across the course of a person's life. Thus the same person may need different types of policies at different times.

Roles Across the Life Course

At any particular point in our lives, we may inhabit a specific category, or “role,” which relates directly to the type of income to which we have access. Consider the following roles that we may have at particular times.

First are roles based on age. Generally, children and older adults are not expected to have factor income. Currently in the United States, those not expected to have factor income are often those under 18 years of age and those 65 years and older. There are, of course, exceptions to this, and these thresholds represent specific historical labor policy developments, but the underlying idea is that under and over a certain age, one is not expected to have factor income.

That leaves those whose age is between 18 and 64; they are sometimes called “working‐age adults.” The default expectation for them is that they have factor income. If they do not have assets that can produce income, then the expectation is that they have factor income from paid labor. But there are several further considerations. First, we typically acknowledge that some individuals may be disabled, either temporarily or permanently, in the sense of being unable to work to earn factor income. Next, we acknowledge that some people may be unemployed, that is, looking to earn factor income but not currently able to. Furthermore, we recognize that some persons may be full‐time students, and so their educational requirements preclude earning factor income. Finally, we recognize that some may be carers, that is, performing unpaid labor to care for their family or friends. Each of these roles provides a sufficient reason not to be expected to have factor income, but people can, and often do, inhabit more than one role at the same time. Moreover, they are likely to inhabit more than one role during their lifetime.

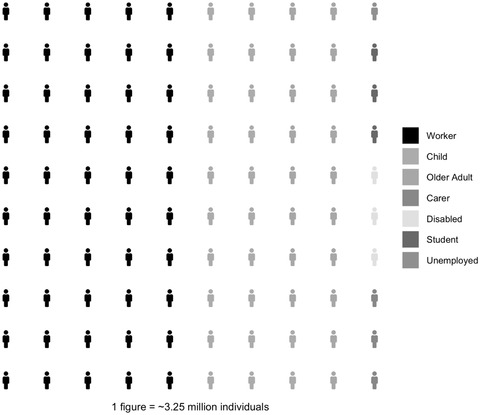

It is important to understand the distribution of these roles in the United States (for details of these calculations, see Figure 1 and the Technical Appendix). Using data from the 2020 American Community Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 22 out of approximately 325 million people in the United States, 73 million (22.5% of the population) are under 18 years of age, and 55 million (16.8% of the population) are age 65 and older. This leaves 197 million (60.7% of the population) between 18 and 64 years of age. Of these, 12 million (3.5% of the population) report being disabled and unable to work, 2 million (0.5% of the population, referring to a period before the COVID‐19 pandemic) report being unemployed, 9 million (2.9% of the population) report being full‐time students, and more than 12 million (3.7% of the population) report being carers without any paid labor. This leaves 163 million (50.1% of the population) who might be expected to have factor income.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Roles in the United States Based on Annual Social and Economic Supplement Data From the 2020 US Census Current Population Survey

As these statistics make clear, only half of all individuals in the United States are likely to have factor income at any given time. Thus, while the problem of income‐related health inequity can be framed as increasing the labor income that individuals can earn, this at best is likely to be only a partial solution.

Individuals and Households

In my foregoing explanation, I focused on people's needs and roles, but for purposes of consumption, people are often aggregated into larger units thought to pool resources: households. For this reason, many measures of income adequacy, such as the Federal Poverty Guideline, and policies to support income, are aimed at the household. But because each individual has consumption needs that affect their health, I think it is important to target policies to individuals rather than their households. Once received, income can still be pooled within a household, but I think it is conceptually clearer to think of policies for each individual in the household, based on the individual's role. Ultimately, a household's risk of inadequate consumption of those goods and services necessary for health (e.g., poverty) is heavily dependent on each of its members’ roles. 9 For example, a household with two adults earning factor income through wages is much less likely to be impoverished than is a household with one adult earning factor income through wages, two dependent children too young to earn income, and one older adult unable to earn factor income owing to disability. 9 , 23

Policy and Program Approaches

Equipped with the distinction between factor and transfer income, as well as a better understanding of individuals’ different roles, we now can turn to policy and programmatic approaches to address income‐related health inequities. Broadly speaking, I see three key decision points for policies addressing an income‐related health inequity, that is, an inequity that can occur when one unjustly does not have sufficient income for adequate consumption of a necessary and existing good or service.

The first question is whether or not to rely on the market to supply what is needed. If one does not wish to rely on the market, then the specific problem to be addressed is “market dependency.” If one does decide to rely on the market, then the problem of insufficient income should be addressed.

The second question is whether those whom the policy is meant to assist are expected to be currently earning factor income. If they are, then the policy might focus on increasing the ability to earn factor income or the level of factor income earned. If the affected people are not expected to be earning factor income, then the policy might consider transfer income.

The third question is whether those whom the policy is meant to assist have previously earned factor income. If they have, then the policy might be organized on the basis of prior earnings. If they have not, then the policy cannot be based on prior earnings. Using these decision points, we can distinguish four main categories of policy design (see Figure 2): social services, social enfranchisement, social insurance, and social assistance, each of which I will describe in more detail.

Figure 2.

Framework of Policy Approaches to Address Income‐Related Health Inequities

Social Services

Without relying on the market to supply a needed service, the corresponding policy approach is making the service freely accessible (i.e., without requiring payment at the point of access), or in other words, financing it “socially.” Though the term sometimes has other meanings, I refer to this approach as “social services.” The decision about relying on the market for supply should likely be based on whether the market can provide efficiently what is needed (perhaps with transfer payments for those who would be unable to otherwise afford it) or whether some market failures make public finance and/or production a better option. Social services remove market dependency (in the sense of being dependent on purchasing a service via the market) and break the link between income and access. Thus, public financing and/or production of essential social services is a form of decommodification, meaning that access to the service is no longer contingent on participating in the market. Social services are often structured as “in‐kind” transfers; that is, beneficiaries receive the service itself rather than using cash to purchase the service. In the United States, one important publicly produced social service is primary and secondary education, which is available to all children regardless of income. In other countries, like the United Kingdom, health care is a social service in this sense.

Social services have both advantages and disadvantages. By breaking the link between income and access, social services are powerful tools to reduce income‐related health inequities. Social services can also mean, however, a substantial investment in infrastructure and personnel (e.g., a national health care system). The public financing and/or production of social services does not guarantee uniform quality of the services received. For example, the quality of public school education can vary according to local funding decisions. In addition, if social services remove price signals, the resulting loss of information may lead to inefficiencies. Finally, because income is a fundamental cause of disease, even if one mechanism that links income to poor health is addressed, the overall association can persist as other mechanisms then become more salient. For example, even countries that have successfully decommodified health care sometimes observe an income gradient to health, mediated by factors besides health care. 24 This suggests that targeting a single pathway between income and health is likely to be less effective in ameliorating income‐related health inequities than are approaches that address multiple pathways or that use income distribution directly. Nevertheless, owing to the irremediable market failures of some necessary services, social services are important tools for policymakers to consider.

Social Enfranchisement

Social enfranchisement approaches are useful for addressing the problem of insufficient factor income when markets can efficiently supply the needed good or service. These approaches seek to remedy the maldistribution of factor income that arises from an imbalance of power among those involved in its creation. These policies and programs adjust this distribution of power by enfranchising those with less power in a system of social relations. This is analogous to political enfranchisement, which adjusts power in political contexts (e.g., via the right to vote). Policies can address factor income earned through assets or wages. For example, policies that tax capital gains income at lower rates than those for labor income affect factor income from assets. To remedy income‐related health inequity, however, social enfranchisement policies that address factor income from wages are more likely to be relevant, as those at a higher risk of income‐related health inequities typically receive little factor income from assets.

A variety of policy approaches can be used to adjust the balance of power that determines how factor income is distributed. One way is to provide a wage floor through minimum wage laws. Another way is to redress power imbalances that may drive down wages. Examples include policies that support unionization, wage boards, and sectoral bargaining; regulate at‐will employment; and promote codetermination (including workers’ representation in corporate governance). Furthermore, tax policy programs based on factor income (e.g., the Earned Income Tax Credit [EITC]) can effectively subsidize wages.

Social enfranchisement can also include more substantive efforts to increase social inclusion, such as establishing and enforcing legal rights. A good way of raising wage income along these lines is addressing discrimination. Racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination may lead to situations in which some individuals (in the United States, particularly women and individuals who identify as Black, Hispanic, and/or Indigenous) are not hired or, when they are hired, receive less income for their work than they otherwise would. 25 , 26 , 27 Discriminatory policies leading to poor education and mass incarceration also greatly affect the ability to earn factor income. 28 , 29 Thus policies directed to address discrimination are likely to reduce income‐related health inequity. Examples of such policies are the passage and enforcement of antidiscrimination laws related to hiring, promotion, and compensation; affirmative action programs; and the enforcement of rules and regulations regarding workplace hostility that may be directed to individuals on the basis of their race, ethnicity, gender, or other types of ascriptive identity.

Social Insurance

Transfer income allows people to buy needed goods and services on the market, regardless of the amount of their factor income. Two functions of transfer income policy are to (1) insure against risks and (2) smooth the consumption of the goods and services needed for health during a person's life by distributing transfer income when a person is unable to earn factor income (during childhood, sickness, and older adulthood). Transfer income policy typically takes one of two forms: social insurance or social assistance. The distinction between the two is whether or not the programs are contributory, that is, whether an individual pays into the program in some way. Contributory programs may not be actuarial, in that people may receive more in benefits than they contribute. Indeed, social insurance is often used when actuarial insurance is not feasible. Nevertheless, the contributions made as part of social insurance programs often have important political implications regarding issues of sustainability. Some situations, like pensions for older adults, lend themselves well to a social insurance approach. Because many individuals have a significant work history before they reach old age, it often makes sense to structure transfer income policies for older adults as social insurance. Such a policy in the United States is the Social Security Administration's Old‐Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program. Indeed, this model has successfully reduced poverty and improved health for older adults worldwide. 30

Unemployment is another situation well suited to the social insurance model. Through a social insurance fund to which employees (and their employers) contribute while working, employees are able to receive income support that permits them to purchase the goods and services needed to maintain health during periods of unemployment. 31 , 32 , 33 Unemployment also offers an example of combining different policy approaches, such as using social insurance together with other approaches like active labor market policies. Active labor market policies include job‐training programs and job placement assistance, public works programs, and employment subsidies paid to either public or private‐sector employers to create a demand for hiring more employees.

Social insurance is also useful during periods of disability, illness, or injury when someone who previously earned factor income is unable do so. In these cases, social insurance programs like worker's compensation, paid sick leave, and disability insurance to replace lost income can work well.

Social Assistance

For those persons who do not have a work history, it may make sense to structure programs as social assistance rather than social insurance. Social assistance programs do not require contributions in order to be eligible. For example, the United States’ Social Security Disability Income program typically requires a work history for eligibility for those who become disabled as adults and thus is a form of social insurance. However, the program waives a work history requirement for those who became disabled before age 22, thereby functioning as social assistance in that case.

Children are a large segment of the population who are not expected to earn factor income and do not have work histories. Therefore, it makes sense to provide transfer income for children as social assistance. Child allowances are common in many countries as a way to prevent childhood poverty. 34 , 35 The temporary Child Tax Credit introduced in 2021 in the United States can be considered a child allowance because it does not require parental income for eligibility (unlike EITC). 36 Note that the logic of these programs is assisting children, based on their specific role, even if the benefits must be paid to their parents or guardians given the children's age. The rationale is that children have needs that must be met, regardless of their parents’ earning ability. A corollary is that even adults without children can benefit from these programs, as the programs would have supported these adults when they were children.

Adult students are often able to work, but temporarily forgo full‐time employment in order to complete their education and training (which may help them earn factor income in the future). The problem here is supporting students during this period. Adult students often do not have significant work histories. Students’ primary source of support is commonly family transfers. But this is unfair because it gives an advantage to students with parents or other family members who can support them. A logical alternative is social assistance. Such programs in the United States include Pell grants, the GI bill, and subsidized student loans. This is not the only approach, however. An alternative, which could be viewed as prospective social insurance, is income‐based repayment of loans to support tuition and living expenses while in school.

The final role to discuss is that of caregiving, which may include raising children or caring for a relative or close friend who is sick or injured. Caregiving is another case for which multiple policy approaches may be useful. A common expectation is that the carers’ income needs will be met by intrahousehold transfers (e.g., one partner earns factor income, on which the household relies, while the other raises their children). This is sometimes helped by policies that encourage such transfers (e.g., the tax code's favorable treatment of marriage). This approach, however, has the inherent trade‐off of increasing dependency within households (i.e., those who do not have factor income become more dependent on those who do). This can be especially problematic when one or more household members would like to leave the household (e.g., owing to interpersonal violence).

Thus different policy approaches should be considered as well. Paid family leave can be structured as either social insurance (a benefit for workers) or social assistance (available to workers regardless of whether they were working just before they needed it). Another social assistance approach is subsidies for child care. Social service approaches, like the government's provision of child care (such as for factory workers during World War II 37 ), can also be used. Other policy approaches have the government pay caregivers for their work. For example, some states have personal care attendant programs that pay family members of older or disabled adults for the care provided, allowing carers to receive income while also fulfilling their caregiving role. 38

Means‐Tested Programs

The framework I have proposed recognizes that we all have times when earning factor income is impossible and that we should try to preempt the negative health consequences that can arise during these times. This type of approach is sometimes called “universalist” because the programs are meant to be used by everyone in a given role (e.g., all children or all older adults). In contrast (and with some important exceptions such as Medicare and OASDI), much of contemporary US social policy views earning factor income, or receiving household transfers, as the default. Programs that take this approach are not meant to be used by everyone inhabiting a particular role, but rather as a last resort: to mitigate the consequences of low income. This is sometimes called a “residualist” approach to social policy, as it seeks to step in only for those with “leftover” needs not met through the market or family resources. 39 For this reason, these programs are “means‐tested,” meaning that having low income and few or no assets are primary eligibility criteria.

Some of the means‐tested programs operating on a residualist logic in the United States are the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides a near‐cash transfer for food; the Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF); the Housing Choice Voucher Program (“Section 8”), which provides rental assistance; and LIHEAP (Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program). These are important programs that help many people. SNAP especially has been shown repeatedly to reduce the depth and breadth of food insecurity, and a burgeoning literature explores its association with better health. 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 WIC has a similar evidence base. 48 The logic of means‐tested programs is very different from the framework I have proposed, however, and this alternative logic presents a number of disadvantages.

First, programs that reach people only once income is low may be less effective for income‐related health inequities because the ill effects of low income can accrue before people become eligible or receive benefits. The life course perspective makes clear that these effects may have long‐lasting impacts on health. Next, the need to establish eligibility through means testing is burdensome for participants, entails transaction costs that limit uptake by eligible individuals, and may contribute to stigma. 49 , 50

Means‐tested programs often impose frequent recertifications and adjustments to benefit levels. This makes planning difficult, particularly as benefit reductions resulting from income fluctuations often represent high marginal tax rates (e.g., the SNAP benefit is reduced by approximately 30% for every dollar earned, a very high marginal tax rate for the income level of a SNAP beneficiary). 51

Finally, the residualist approach inherently creates a two‐tiered system in which the well‐off use mainstream programs, while “safety net” programs are used only by individuals with no other options. This may contribute to the perception that the programs are being used by those refusing to work, when instead they are mostly used by people who are working and/or those who have valid reasons not to work, such as children and older adults. 52 This can undermine support for the program and encourage insufficient benefit levels and punitive administration.

Universal Basic Income

A policy approach that is rapidly gaining recognition is universal basic income (UBI). 53 , 54 It may be regarded as an alternative to the approach I have proposed in that it does not consider its beneficiaries’ specific roles. But not doing this may have drawbacks.

Although the evidence is still being collected, studies have found positive health impacts for UBI, including improved mental health and birth weight. 54 In addition, UBI is attractive because it offers an income floor to all individuals and prevents health inequities caused by income levels below that floor. Nonetheless, UBI may have disadvantages as well. For individuals able to earn sufficient factor income, UBI may have no effect on their health. Furthermore, the cost of providing UBI to all individuals regardless of their role means lower per‐person benefits for a given cost compared with those of a policy that provides transfer income to only, say, those not expected to earn factor income. 53 If this lower benefit level means that those not expected to earn factor income are still unable to access needed goods and services, and those able to earn factor income receive no health benefit, then this approach may have little effect on reducing income‐related health inequity. These problems might be addressed through combination approaches (i.e., setting a relatively low UBI floor for everyone and supplementing that with other policies suited to an individual's role), though this would forgo the simplicity (i.e., having a single program to replace many) that many UBI advocates support, and would return to a role‐based approach. Although I cannot consider UBI in more detail here owing to space limitations, an examination of UBI compared, or in combination, with the proposed framework is an important future direction.

Limitations

In this perspective, I have described a conceptual framework for thinking through policy approaches to addressing income‐related health inequities. My framework is intended to be general rather than specific to a particular problem or policy. To design a policy using this framework, additional and case‐specific information would, of course, be needed. Such a policy should include clear empirical evidence about the relationship of income, a particular health outcome, and the effects of intervention; an understanding of the relevant stakeholders and political factors at play; a plan for financing the policy; and principles of successful policy implementation.

Conclusions

The general problem underlying the association between lower income and poor health is insufficient consumption of the goods and services necessary to achieve and maintain health across the life course. Throughout our lives, all of us will sometimes be unable to earn factor income. Indeed, at any particular point in time, only about 50% of the US population is able to do so. Therefore, policymakers should use social services, social enfranchisement, social insurance, and social assistance approaches, preferably arranged as complementary and overlapping programs, to address income as a fundamental cause of poor health.

Funding/Support: Funding for SAB's role on this work was provided by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award no. K23DK109200. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments: I thank Samuel T. Edwards, MD, MPH, for helpful comments on this manuscript. He was not compensated for his efforts.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: SAB reports receiving personal fees from the Aspen Institute outside the submitted work.

The distribution of roles in the United States was based on data from the 2020 US Census Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC). This covers calendar year 2019.

Individuals were categorized into mutually exclusive roles using the following method: Age < 18 years (“child”) or ≥ 65 years (“older adult”) was assigned using the variable “A_AGE.” Individuals aged 18 to 64 years, inclusive, were considered carers if they reported that their main reason for not working in 2019 was “taking care of home” (variable RSNNOTW = 3). Individuals aged 18 to 64 years were considered disabled if they reported that their main reason for not working in 2019 was their being “ill or disabled” (variable RSNNOTW = 1). Individuals aged 18 to 64 years were considered students if they reported that their main reason for not working in 2019 was “going to school” (variable RSNNOTW = 4). Individuals aged 18 to 64 years were considered unemployed if they reported that their main reason for not working in 2019 was “unable to find work” (variable RSNNOTW = 5). This definition is different from the Bureau of Labor Statistics definition of unemployment. If none of these categories applied, such individuals were considered to be workers (i.e., persons expected to earn factor income), regardless of whether they were currently working.

References

- 1. Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;Spec no:80‐94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(Suppl.):S28‐S40. 10.1177/0022146510383498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Phelan JC, Link BG. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annu Rev Sociol. 2015;41(1):311‐330. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105‐125. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453‐1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl.1):S186‐S196. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35(4):407‐411. 10.1037/hea0000242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kinge JM, Modalsli JH, Øverland S, et al. Association of household income with life expectancy and cause‐specific mortality in Norway, 2005‐2015. JAMA. 2019;321(19):1916‐1925. 10.1001/jama.2019.4329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruenig M. The best way to eradicate poverty: welfare not jobs. People's Policy Project website. https://www.peoplespolicyproject.org/2018/09/18/the‐best‐way‐to‐eradicate‐poverty‐welfare‐not‐jobs/. Published September 18, 2018. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- 10. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Integrating Social Care Into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation's Health. New York, NY: National Academies Press; 2019. 10.17226/25467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. Income inequality and health: a causal review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:316‐326. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muennig P, Franks P, Jia H, Lubetkin E, Gold MR. The income‐associated burden of disease in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(9):2018‐2026. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levesque AR, MacDonald S, Berg SA, Reka R. Assessing the impact of changes in household socioeconomic status on the health of children and adolescents: a systematic review. Adolesc Res Rev. February 2, 2021:6(2):91‐123. 10.1007/s40894-021-00151-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Courtin E, Kim S, Song S, Yu W, Muennig P. Can social policies improve health? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of 38 randomized trials. Milbank Q. 2020;98(2):297‐371. 10.1111/1468-0009.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khullar D, Chokshi DA. Health, income, & poverty: where we are & what could help. Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20180817.901935/full/. Published October 4, 2018. Accessed March 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rigby E, Hatch ME. Incorporating economic policy into a “health‐in‐all‐policies” agenda. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(11):2044‐2052. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Armstrong GL, Conn LA, Pinner RW. Trends in infectious disease mortality in the United States during the 20th century. JAMA. 1999;281(1):61‐66. 10.1001/jama.281.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moy E, Garcia MC, Bastian B, et al. Leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan areas—United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(1):1‐8. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6601a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liao TF, De Maio F. Association of social and economic inequality with coronavirus disease 2019 incidence and mortality across US counties. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034578. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Almeida‐Filho N. A glossary for health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(9):647‐652. 10.1136/jech.56.9.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rolph ER. The concept of transfers in national income estimates. Q J Econ. 1948;62(3):327‐361. 10.2307/1882835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. US Census Bureau . Annual social and economic supplements. https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time‐series/demo/cps/cps‐asec.html. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- 23. Bruenig M. The success sequence has found its latest mark. People's Policy Project website. https://www.peoplespolicyproject.org/2021/03/01/the‐success‐sequence‐has‐found‐its‐latest‐mark/. Published March 1, 2021. Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 24. Martinson ML. Income inequality in health at all ages: a comparison of the United States and England. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(11):2049‐2056. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bertrand M, Mullainathan S. Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. Am Econ Rev. 2004;94(4):991‐1013. 10.1257/0002828042002561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Experiences Versus American Expectations. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. https://www.eeoc.gov/special‐report/american‐experiences‐versus‐american‐expectations. Accessed March 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Graf N, Brown A, Patten E. The narrowing, but persistent, gender gap in pay. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact‐tank/2019/03/22/gender‐pay‐gap‐facts/. Published March 22, 2019. Accessed March 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bayer P, Charles KK. Divergent paths: a new perspective on earnings differences between black and white men since 1940. Q J Econ. 2018;133(3):1459‐1501. 10.1093/qje/qjy003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brennan Center for Justice Conviction, imprisonment, and lost earnings: how involvement with the criminal justice system deepens inequality. https://www.brennancenter.org/our‐work/research‐reports/conviction‐imprisonment‐and‐lost‐earnings‐how‐involvement‐criminal. Published September 15, 2020. Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 30. Jacques P, Leroux M‐L, Stevanovic D. Poverty among the elderly: the role of public pension systems. Int Tax Public Finance. 2021;28(1):24‐67. 10.1007/s10797-020-09617-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berkowitz SA, Basu S. Unemployment insurance, health‐related social needs, health care access, and mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(5):699–702. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raifman J, Bor J, Venkataramani A. Association between receipt of unemployment insurance and food insecurity among people who lost employment during the COVID‐19 pandemic in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2035884. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Berkowitz SA, Basu S. Unmet social needs and worse mental health after expiration of COVID‐19 federal pandemic unemployment compensation. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(3):426‐434. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34. Smeeding T, Thévenot C. Addressing child poverty: how does the United States compare with other nations? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(Suppl.3):S67‐S75. 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bruenig M Family fun pack. People's Policy Project website. https://peoplespolicyproject.org/projects/family‐fun‐pack. Published 2019. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- 36. Marr C, Cox K, Hingtgen S, Windham K, Sherman A. House COVID relief bill includes critical expansions of child tax credit and EITC. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities website. https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal‐tax/house‐covid‐relief‐bill‐includes‐critical‐expansions‐of‐child‐tax‐credit‐and. Updated March 2, 2021. Accessed March 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Riley SE. Caring for Rosie's children: federal child care policies in the World War II era. Polity. 1994;26(4):655‐675. 10.2307/3235099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MassHealth Personal Care Attendant (PCA) Program. Mass.gov website. https://www.mass.gov/masshealth‐personal‐care‐attendant‐pca‐program. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- 39. Jacques O, Noël A. Targeting within universalism. J Eur Soc Policy. 2021;31(1):15‐29. 10.1177/0958928720918973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gregory CA, Smith TA. Salience, food security, and SNAP receipt. J Policy Anal Manage. 2019;38(1):124‐154. 10.1002/pam.22093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ratcliffe C, McKernan S.‐M. How much does SNAP reduce food insecurity? Economic Research Service, US Department of Agriculture. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=84335. Published April 2010. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- 42. Ettinger de Cuba SA, Bovell‐Ammon AR, Cook JT, et al. SNAP, young children's health, and family food security and healthcare access. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(4):525‐532. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Rigdon J, Meigs JB, Basu S. Supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) participation and health care expenditures among low‐income adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(11):1642‐1649. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gregory CA, Ver Ploeg M, Andrews M, Coleman‐Jensen A. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participation leads to modest changes in diet quality. Economic Research Report No. (ERR‐147). Economic Research Service, US Department of Agriculture. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub‐details/?pubid=45062. Published April 2013. Accessed February 9, 2021.

- 45. Szanton SL, Samuel LJ, Cahill R, et al. Food assistance is associated with decreased nursing home admissions for Maryland's dually eligible older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):162. 10.1186/s12877-017-0553-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Samuel LJ, Szanton SL, Cahill R, et al. Does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program affect hospital utilization among older adults? The case of Maryland. Popul Health Manage. 2018;21(2):88‐95. 10.1089/pop.2017.0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47. Berkowitz SA, Palakshappa D, Rigdon J, Seligman HK, Basu S. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation and health care use in older adults: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(12):1674–1682. 10.7326/M21-1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. About WIC—how WIC helps . USDA Food and Nutrition Service website. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about‐wic‐how‐wic‐helps. Published October 10, 2013. Accessed August 2, 2018.

- 49.Reaching those in need: estimates of state SNAP participation rates in FY 2016. USDA Food and Nutrition Service website. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/reaching‐those‐need‐estimates‐state‐supplemental‐nutrition‐assistance‐program‐participation‐rates‐fy. Published March 13, 2019. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- 50. Herd P, Moynihan DP. Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Maag E, Steuerle CE, Chakravarti R, Quakenbush C. How marginal tax rates affect families at various levels of poverty. Natl Tax J. 2012;65(4):759‐783. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Loveless TA. Most families that received SNAP benefits in 2018 had at least one person working. US Census Bureau website. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/07/most‐families‐that‐received‐snap‐benefits‐in‐2018‐had‐at‐least‐one‐person‐working.html. Published July 21, 2020. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- 53. Hoynes H, Rothstein J. Universal basic income in the United States and advanced countries. Annu Rev Econ. 2019;11(1):929‐958. 10.1146/annurev-economics-080218-030237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gibson M, Hearty W, Craig P. The public health effects of interventions similar to basic income: a scoping review. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(3):e165‐e176. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]