Key Points

Question

How effective are electronic secure messages and mailings from primary care physicians (PCPs) for COVID-19 vaccination among Black and Latino older adults?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial among 8287 Black and Latino adults aged 65 years and older found that both standard and culturally tailored electronic secure messages and mailings from individuals’ own PCPs led to significantly higher COVID-19 vaccination rates at 8 weeks than usual care. There was no difference in vaccination rates between standard and culturally tailored PCP outreach.

Meaning

These findings suggest that electronic and mail outreach from PCPs increased COVID-19 vaccination rates among Black and Latino older adults. More intensive strategies are also warranted.

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the effect of outreach from primary care physicians on COVID-19 vaccination uptake among Black and Latino older adults

Abstract

Importance

COVID-19 morbidity is highest in Black and Latino older adults. These racial and ethnic groups initially had lower vaccination uptake than others, and rates in Black adults continue to lag.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of outreach via electronic secure messages and mailings from primary care physicians (PCPs) on COVID-19 vaccination uptake among Black and Latino older adults and to compare the effects of culturally tailored and standard PCP messages.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial was conducted from March 29 to May 20, 2021, with follow-up surveys through July 31, 2021. Latino and Black individuals aged 65 years and older from 4 Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) service areas were included. Data were analyzed from May 27, 2021, to September 28, 2021.

Interventions

Individuals who had not received COVID-19 vaccination after previous outreach were randomized to electronic secure message and/or mail outreach from their PCP, similar outreach with additional culturally tailored content, or usual care. Outreach groups were sent a secure message or letter in their PCP’s name, followed by a postcard to those still unvaccinated after 4 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was time to receipt of COVID-19 vaccination during the 8 weeks after initial study outreach. KPNC data were supplemented with state data from external sources. Intervention effects were evaluated via proportional hazards regression.

Results

Of 8287 included individuals (mean [SD] age, 72.6 [7.0] years; 4665 [56.3%] women), 2434 (29.4%) were Black, 3782 (45.6%) were Latino and preferred English-language communications, and 2071 (25.0%) were Latino and preferred Spanish-language communications; 2847 participants (34.4%) had a neighborhood deprivation index at the 75th percentile or higher. A total of 2767 participants were randomized to culturally tailored PCP outreach, 2747 participants were randomized to standard PCP outreach, and 2773 participants were randomized to usual care. Culturally tailored PCP outreach led to higher COVID-19 vaccination rates during follow-up compared with usual care (664 participants [24.0%] vs 603 participants [21.7%]; adjusted hazard ratio (aHR), 1.22; 95% CI, 1.09-1.37), as did standard PCP outreach (635 participants [23.1%]; aHR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04-1.31). Individuals who were Black (aHR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06-1.33), had high neighborhood deprivation (aHR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.03-1.33), and had medium to high comorbidity scores (aHR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.09-1.31) were more likely to be vaccinated during follow-up.

Conclusions and Relevance

This randomized clinical trial found that PCP outreach using electronic and mailed messages increased COVID-19 vaccination rates among Black and Latino older adults.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05096026

Introduction

Vaccination is a crucial tool for controlling COVID-19, which has caused disproportionately high morbidity and mortality among Black and Latino persons in the US.1,2 Vaccination rates among adults in these racial and ethnic groups initially trailed those of Asian and White adults, and uptake in Black adults continues to lag.3 Possible causes of this gap include worse access, skepticism about vaccine effectiveness or safety, and mistrust.4,5

Primary care physicians (PCPs) may potentially play a key role in enhancing COVID-19 vaccination rates, especially for Black and Latino older adults with vaccine hesitancy, because PCPs are trusted sources of information.6,7 However, scant evidence exists about the effectiveness of outreach by PCPs to promote COVID-19 vaccination in these high-risk groups.

We conducted a randomized clinical trial of PCP outreach for COVID-19 vaccination among Black and Latino older adults in a socioeconomically diverse population. This study’s objectives were to evaluate the effects of PCP outreach using electronic secure messages and mailings on COVID-19 vaccination among Black and Latino persons aged 65 years and older and to compare the effects of culturally tailored and standard PCP messages.

Methods

This randomized clinical trial was determined to not meet the regulatory definition of research involving human participants per 45 CFR 46.102(d) by the Research Determination Committee for the Kaiser Permanente Northern California region. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 1. This study follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline for randomized studies.

Study Design and Setting

This 3-arm randomized clinical trial compared electronic secure message and mailed outreach from PCPs (culturally tailored or standard PCP outreach) with usual care for Black and Latino individuals aged 65 years and older who had not responded to earlier nonpersonalized email and mailed outreach for COVID-19 vaccination. The intervention period was March 29 to April 22, 2021, with vaccination outcomes followed through May 20, 2021. Interventions were developed by The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG), associated with Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), an integrated system serving a diverse 4.5 million member population. For this study we selected 4 service areas with relatively low vaccination rates and high proportions of Black and Latino individuals: the California Central Valley, Fresno, South Sacramento, and San Jose.

Participants

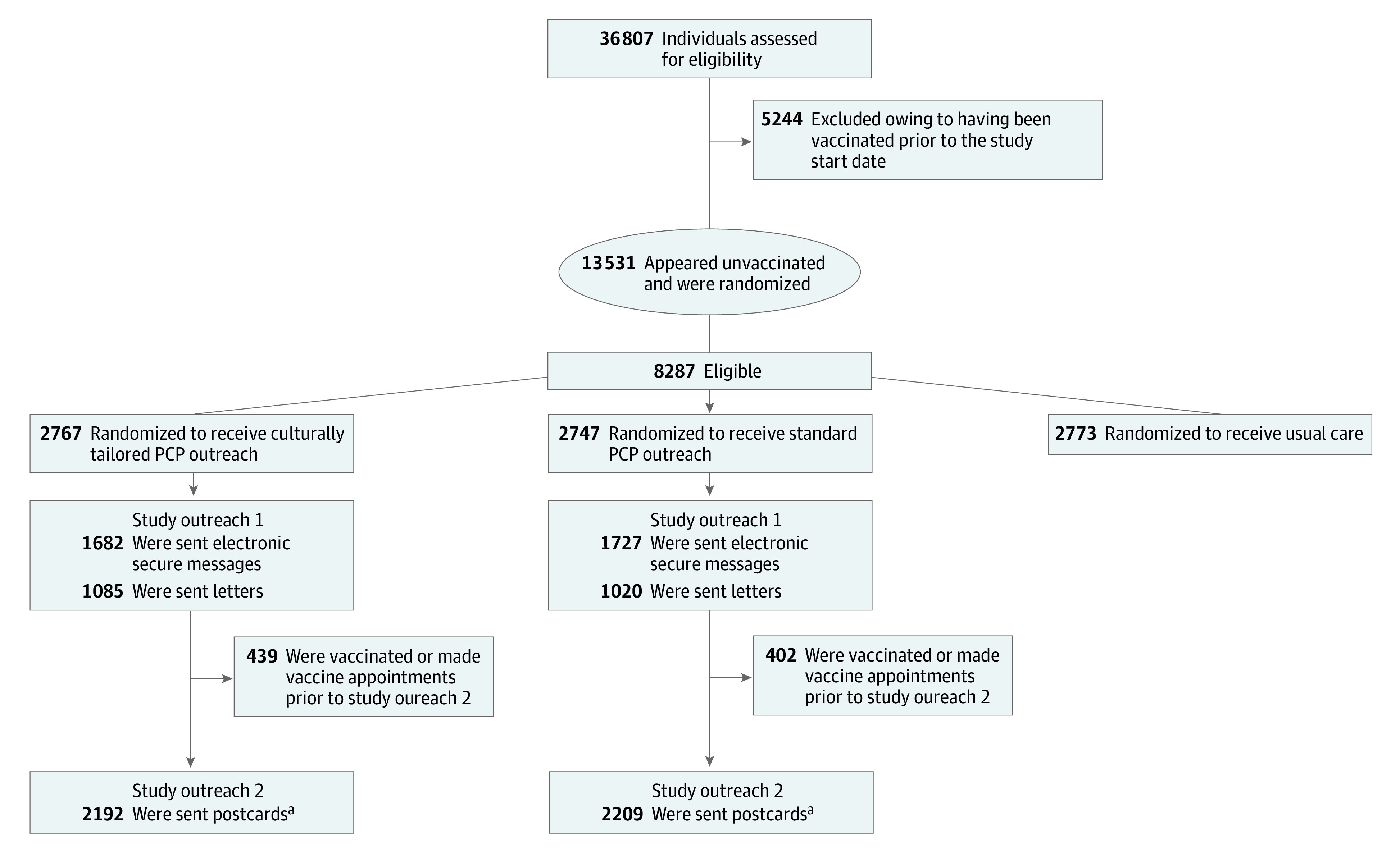

KPNC members aged 65 years and older were eligible if they had been sent prior outreach but had not received a COVID-19 vaccination (in any California location, within or outside KP) or made a vaccination appointment with KP as of March 29, 2021. The prior outreach used emails (or letters when email addresses were not available) from the KP regional COVID-19 vaccination team to invite individuals to book a vaccine appointment online or by telephone. Figure 1 shows the flow of individuals through the study. Individuals were allocated 1:1:1 to the 3 study arms using a random number generator. Randomization was stratified by race, ethnicity, and language group (Black, Latino with English preferred, and Latino with Spanish preferred) and by geographic area.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Individuals Included.

PCP indicates primary care physician.

aIn the culturally tailored outreach group, 439 individuals were vaccinated and 136 were not sent study outreach 2 owing to operational error. In the standard PCP outreach group, 402 were vaccinated and 136 were not sent study outreach 2 owing to operational error.

Interventions

All individuals assigned to standard or culturally tailored PCP outreach (the intervention groups) were eligible for 2 rounds of study outreach. Outreach messages were crafted using behavioral science principles, including social proof, loss aversion, and authority figures.8,9 Other strategies were to leverage culturally relevant messaging and reduce barriers to action with information to facilitate appointment booking.

Study outreach 1, sent to all individuals in the intervention groups, was an electronic secure message sent individually to each individual who had signed up to use the electronic health record (EHR) patient portal. Messages were sent by the TPMG Consulting Services regional department in the name of the individual’s PCP (internist or family medicine physician). The study outreach was more personalized than prior outreach emails, which were not from individuals’ PCPs and not sent via the EHR portal. Individuals who had not signed up to use the EHR portal were sent letters in their PCP’s name. Individuals were sent information in Spanish if it was their preferred written language.

Message content addressed trust in the vaccine, safety and effectiveness, side effects, and how to book a vaccine appointment at KP. All messages (electronic, letter, and postcard) had the website link and telephone number for vaccine appointments; the letter and postcard had a quick response (QR) code as well. Culturally tailored PCP messages included the standard PCP messages and addressed these additional issues: (1) cost and immigration status: “The vaccine is available at no cost and regardless of your immigration status. We want to reassure you that we never share your personal information with outside agencies” and (2) racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19: “Getting vaccinated protects those who have been most harmed by COVID-19 like Latinos/Latinx, Black/African Americans, and many others.”

Study outreach 2, sent to all individuals in the intervention groups who had not been vaccinated or made an appointment by 4 weeks after study outreach 1, was a postcard with similar content as in study outreach 1. It included vaccine information and a QR code, website, and telephone number to facilitate appointment booking. Individuals in the culturally tailored PCP outreach group received postcards with photos of older adults in their racial and ethnic group as well as the aforementioned culturally tailored content; postcards sent to the standard PCP outreach group had no photo.

The usual care group were not sent any of the PCP outreach messages above. However, local departments in the 4 participating service areas were not restricted from conducting other COVID-19 vaccination outreach. In addition, individuals in the Fresno service area were sent interactive voice response outreach messages several weeks after study outreach 2. Local departments were blind to the group assignment of study participants.

Data Sources

COVID-19 vaccination data were drawn from the KP EHR and California state immunization data, which included COVID-19 vaccines administered at all locations, including mass vaccination clinics and pharmacies. In early 2021, state immunization data lagged actual vaccine administration events by up to 2 months. We excluded from analyses individuals who had actually been vaccinated by the date of study outreach 1. Final analyses were conducted in late July 2021, allowing 2 months for data lag to resolve after observation for the vaccine outcome closed on May 20, 2021. Individuals were counted as vaccinated if they had received at least 1 dose of any vaccine.

Participant characteristics were drawn from KP EHR and geocoded Census block-group data. Race, ethnicity, and language preference were self-reported by participants. Participants were counted as Latino with Spanish preferred if EHR data listed Spanish as their preferred written language. Comorbidities were measured using Comorbidity Point Score, version 2, the validated standard measure used for operational purposes within KPNC.10

Statistical Analysis

Participants in the culturally tailored and standard outreach groups were followed from their first study outreach until first vaccination or until 28 days after their last study outreach. Participants in the usual care group were followed from the date the first study outreach was sent (on March 29, 2021) until first vaccination or until 28 days after the last study outreach was sent on April 22, 2021 (resulting in a maximum observation period of 52 days). The primary analysis used intention-to-treat assignment and compared time to vaccination between each outreach group with usual care using Cox proportional hazards regression. Models included a fixed effect for study group and adjustment for race, ethnicity, and language group and geographic area. For subgroup analyses, we did not use a Bonferroni or other adjustment for type I error; thus, these should be interpreted as exploratory. Analyses were conducted in SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

The sample size was determined by including all eligible KPNC members within the population. The sample size of 2773 in the usual care group, with similar sample sizes in the intervention groups, had 80% power at a 2-tailed α = .05 to detect a hazard ratio of at least 1.17 (intervention vs usual care; assumed rate in usual care = 21.7%).11,12 Data were analyzed from May 27, 2021, to September 28, 2021.

Results

Participant Characteristics

In this study’s 4 service areas, as of March 29, 2021, there were 36 807 KPNC members aged 65 years and older who were Black or Latino. Of these, 13 531 individuals were identified as initially eligible and randomly allocated to 1 of the 3 study groups. In the final analysis, 5244 individuals were excluded owing to subsequent data indicating they had received a COVID-19 vaccine prior to the study start. Therefore, the final study sample included 8287 individuals (mean [SD] age, 72.6 [7.0] years; 4665 [56.3%] women), with 2767 individuals in the culturally tailored PCP outreach group, 2747 individuals in the standard PCP outreach group, and 2773 individuals in the usual care group. Overall, there were 5773 individuals (69.7%) aged 65 to 74 years and 2514 individuals (30.3%) aged 75 years or older; 2434 individuals (29.4%) were Black, 3782 individuals (45.6%) were Latino and preferred English-language communications, and 2071 individuals (25.0%) were Latino and preferred Spanish-language communications. A total of 2847 participants (34.4%) had a neighborhood deprivation index at the 75th percentile or higher (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Individuals by Study Group.

| Characteristic | Individuals, No. (%)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 8287) | Culturally tailored PCP outreach (n = 2767) | Standard PCP outreach (n = 2747) | Usual care (n = 2773) | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 65-74 | 5773 (69.7) | 1951 (70.5) | 1890 (68.8) | 1932 (69.7) |

| ≥75 | 2514 (30.3) | 816 (29.5) | 857 (31.2) | 841 (30.3) |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 3622 (43.7) | 1225 (44.3) | 1201 (43.7) | 1196 (43.1) |

| Women | 4665 (56.3) | 1542 (55.7) | 1546 (56.3) | 1577 (56.9) |

| Race or ethnicity with preferred language | ||||

| Black | 2434 (29.4) | 818 (29.6) | 809 (29.5) | 807 (29.1) |

| Latino-English preferred | 3782 (45.6) | 1279 (46.2) | 1236 (45.0) | 1267 (45.7) |

| Latino-Spanish preferredb | 2071 (25.0) | 670 (24.2) | 702 (25.6) | 699 (25.2) |

| Neighborhood Deprivation Index, percentile | ||||

| <25th (least deprived) | 1396 (16.8) | 455 (16.4) | 494 (18.0) | 447 (16.1) |

| 25th-74th | 3561 (43.0) | 1207 (43.6) | 1127 (41.0) | 1227 (44.2) |

| 75th-89th | 1566 (18.9) | 504 (18.2) | 543 (19.8) | 519 (18.7) |

| ≥90th (most deprived) | 1281 (15.5) | 435 (15.7) | 428 (15.6) | 418 (15.1) |

| Unknown | 483 (5.8) | 166 (6.0) | 155 (5.6) | 162 (5.8) |

| Comorbidity score | ||||

| Low risk | 4985 (60.2) | 1649 (59.6) | 1652 (60.1) | 1684 (60.7) |

| Medium risk | 2579 (31.1) | 856 (30.9) | 857 (31.2) | 866 (31.2) |

| High risk | 723 (8.7) | 262 (9.5) | 238 (8.7) | 223 (8.0) |

| Service area | ||||

| Central Valley | 3206 (38.7) | 1063 (38.4) | 1066 (38.8) | 1077 (38.8) |

| Fresno | 1757 (21.2) | 564 (20.4) | 586 (21.3) | 607 (21.9) |

| San Jose | 1190 (14.4) | 422 (15.3) | 400 (14.6) | 368 (13.3) |

| South Sacramento | 2134 (25.8) | 718 (25.9) | 695 (25.3) | 721 (26.0) |

| Outreaches before study, No. | ||||

| 1 | 2021 (24.4) | 679 (24.5) | 667 (24.3) | 675 (24.3) |

| 2 | 5383 (65.0) | 1797 (64.9) | 1779 (64.8) | 1807 (65.2) |

| 3-4 | 883 (10.7) | 291 (10.5) | 301 (11.0) | 291 (10.5) |

Abbreviation: PCP, primary care physicians.

Individual characteristics were drawn from electronic health records and from geocoded Census block-group data.

Individuals were counted as Latino with Spanish preferred if electronic health record data listed Spanish as their preferred written language.

COVID-19 Vaccination Outcome

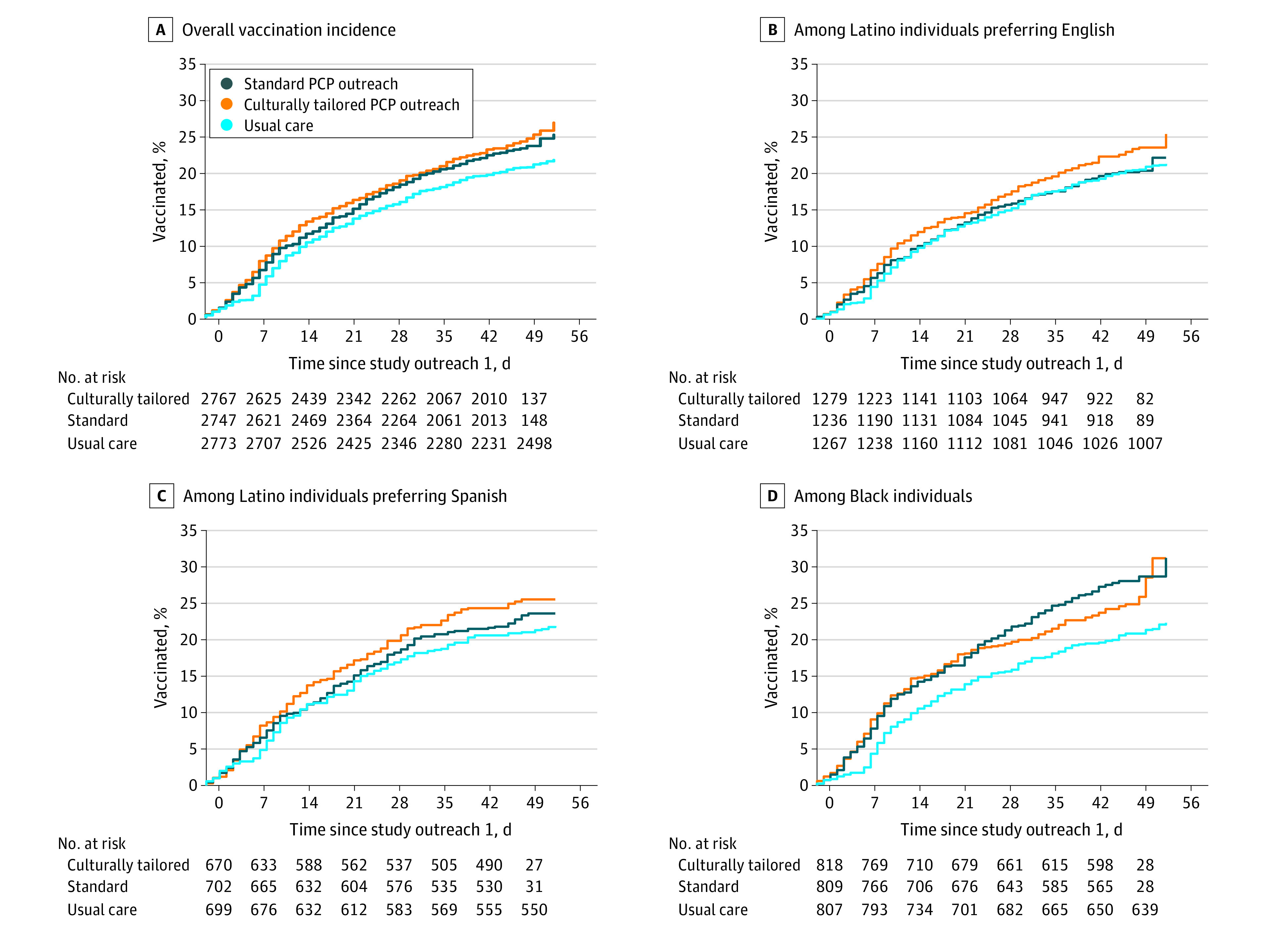

Vaccination rates at 8 weeks after the intervention start were 664 individuals (24.0%) in the culturally tailored PCP outreach group, 635 individuals (23.1%) in the standard PCP outreach group, and 603 individuals (21.7%) in the usual care group. Cumulative incidence curves (Figure 2A) indicate that culturally tailored PCP outreach resulted in a significantly higher rate of vaccination than usual care (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.22; 95% CI, 1.09-1.37; P < .001), as did standard PCP outreach (aHR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04-1.31; P = .007). The difference between culturally tailored and standard PCP outreach was not significant (aHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.94-1.17; P = .42).

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of COVID-19 Vaccination in the Culturally Tailored Primary Care Physician (PCP) Outreach, Standard PCP Outreach, and Usual Care Arms Among Black and Latino Adults Aged 65 Years and Older.

A. Culturally tailored PCP outreach resulted in a significantly higher rate of vaccination than usual care (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.22; 95% CI, 1.09-1.37; P < .001), as did standard PCP outreach (aHR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04-1.31; P = .007). The difference between culturally tailored and standard PCP outreach was not significant (aHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.94-1.17; P = .42). B. Culturally tailored PCP outreach resulted in a higher rate of vaccination than usual care, but the difference was not statistically significant (aHR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.98-1.37; P = .09). The differences between standard PCP outreach and usual care (aHR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.85-1.21; P = .85) and between culturally tailored and standard PCP outreach (aHR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.96-1.35; P = .13) were not significant. C. Culturally tailored PCP outreach resulted in a significantly higher rate of vaccination than usual care (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.00 - 1.56; P = .049). The differences between standard PCP outreach and usual care (aHR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.89-1.40, P = .33) and between culturally tailored and standard PCP outreach was not significant (aHR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.90-1.39, P = .32) were not significant. D. Culturally tailored PCP outreach resulted in a significantly higher rate of vaccination than usual care (aHR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.06-1.59; P = .011), as did standard PCP outreach (aHR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.19-1.77; P < .001). The difference between culturally tailored and standard PCP outreach was not significant (aHR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.74-1.08; P = .25).

Table 2 shows vaccination outcomes after study outreach 1 (secure message or letter) and after study outreach 2 (postcard) compared with usual care during the same time periods. Participants receiving culturally tailored or standard PCP outreach were vaccinated earlier than those receiving usual care (vaccination at 4 weeks: culturally tailored PCP outreach, 439 participants [15.9%]; standard PCP outreach, 402 participants [14.6%]; usual care, 312 participants [11.3%]; P < .001). Among individuals who received vaccinations, approximately two-thirds of those in the intervention arms received a vaccine between study outreach 1 and study outreach 2, compared with 52% of those in usual care (Table 2). In the culturally tailored PCP outreach group, 214 individuals (28.1%) who read the secure messages they were sent and 280 individuals (25.8%) sent a letter were vaccinated, compared with 170 individuals (18.5%) who were sent secure messages that went unread (P < .001). Similar differences were observed in the standard PCP outreach group.

Table 2. Vaccination Rates Among Individuals Assigned to Culturally Tailored PCP Outreach, Standard PCP Outreach, or Usual Care.

| Outreach | No. | Received COVID-19 vaccination, No. (row %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| After study outreach 1 and before study outreach 2a | Within 4 wk after study outreach 2b | At any time during follow-upc | ||

| Culturally tailored PCP outreach | ||||

| Overall | 2767 | 439 (15.9) | 225 (8.1) | 664 (24.0) |

| Study outreach 1 | ||||

| Secure message | ||||

| Read | 763 | 140 (18.4) | 74 (9.7) | 214 (28.1) |

| Unread | 919 | 107 (11.6) | 63 (6.9) | 170 (18.5) |

| Letter | 1085 | 192 (17.7) | 88 (8.1) | 280 (25.8) |

| Study outreach 2: postcard | 2192 | NA | 225 (10.3) | 225 (10.3) |

| Standard PCP outreach | ||||

| Overall | 2747 | 402 (14.6) | 233 (8.5) | 635 (23.1) |

| Study outreach 1 | ||||

| Secure message | ||||

| Read | 792 | 153 (19.3) | 77 (9.7) | 230 (29.0) |

| Unread | 935 | 93 (10.0) | 73 (7.8) | 166 (17.8) |

| Letter | 1020 | 156 (15.3) | 83 (8.1) | 239 (23.4) |

| Study outreach 2: postcard | 2209 | NA | 233 (10.6) | 233 (10.6) |

| Usual care | 2773 | 312 (11.3) | 291 (10.5) | 603 (21.7) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable; PCP, primary care physicians.

March 29 to April 21, 2021.

April 22 to May 20, 2021.

March 29 to May 20, 2021.

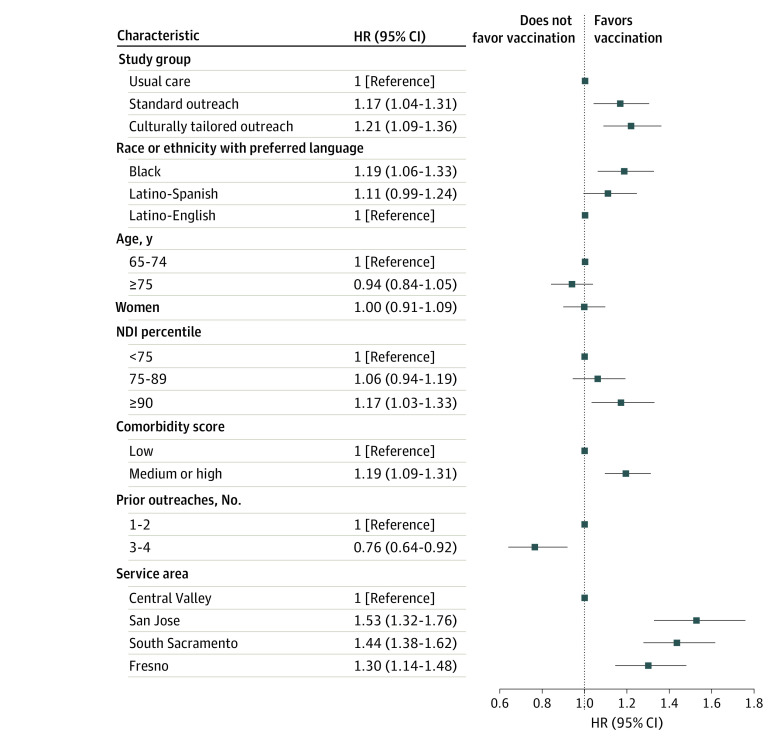

Other Correlates of Vaccination During Follow-up

Figure 3 shows participant characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccination during follow-up, adjusted for study group. Black individuals were significantly more likely than Latino individuals who preferred English to be vaccinated (aHR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06-1.33; P = .004). There was no significant difference between Latino individuals who preferred Spanish compared with those who preferred English (aHR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.99-1.25; P = .08). Individuals with higher neighborhood deprivation (≥90th percentile: aHR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.03-1.33; P = .02) and those with medium or high comorbidity scores (aHR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.09-1.31; P < .001) were more likely than others to be vaccinated. Age and sex were not associated with vaccination. Individuals in San Jose, South Sacramento, and Fresno were more likely to be vaccinated than those in the Central Valley (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Variables Associated with Vaccination During Follow-up.

The follow-up period spanned March 29 to May 20, 2021, which included 28 days after both waves of study outreach were complete. HR indicates hazard ratio.

Subgroup Analyses

Vaccination rates by study group in the Black, Latino with English preferred, and Latino with Spanish preferred subgroups are presented in Figure 2B-D. Among Latino individuals, culturally tailored PCP outreach led to higher rates than usual care among those who preferred Spanish (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.00-1.56; P = .05), but not among those who English (aHR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.98-1.37, P = .09). Among Black individuals, standard PCP outreach (aHR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.19-1.77; P < .001) and culturally tailored PCP outreach (aHR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.06-1.59; P = .01) both led to higher vaccination rates than usual care. However, an analysis of interaction terms in the multivariable model did not find significant heterogeneity in study group effects across race, ethnicity, and language groups.

Prestudy Vaccination Rates

To provide context for these results, we conducted a retrospective analysis to estimate the actual vaccination rate among all older Black and Latino KPNC members in the 4 service areas as of this study’s start date, March 29, 2021. This analysis was conducted in October 2021, which allowed ample time for data lag to resolve. Overall, the starting vaccination rate was 74.1%. Subgroup vaccination rates were 71.1% among Black individuals, 76.4% among Latino individuals who preferred English, and 71.7% among Latino individuals who preferred Spanish.

Discussion

This randomized clinical trial found that secure messages and mail outreach sent on behalf of individuals’ own PCPs led to a significant increase in COVID-19 vaccination rates among Black and Latino older adults who had not responded to earlier, less personalized outreach. If this culturally tailored PCP outreach were conducted for all unvaccinated US Black and Latino adults aged 65 years and older, assuming the same additional 2.2% vaccination rate were gained, an additional 238 000 persons nationally may have been vaccinated. This suggests that PCP outreach should not be overlooked as a potentially effective approach for Black and Latino older adults.

Our study was unique in its focus on Black and Latino older adults. Very few randomized clinical trials of outreach to promote COVID-19 vaccination have been reported.13,14 A previous trial in a university-based health system of individuals of all ages and racial and ethnic groups13 found that text messages increased vaccination rates by 1% among those who had not responded to an earlier text message outreach. In comparison, our trial of PCP outreach using electronic and mailed messages found up to a 2.2% increase in Black and Latino older adults who had not responded to earlier, less personalized outreach.

One notable aspect of our study was that electronic messages and mailings were sent in the name of each individual’s own PCP. The increases in COVID-19 vaccination rates we observed aligns with surveys and expert opinion suggesting that physicians are key influencers with their patients.5,6,7 Our finding that electronic reminders for COVID-19 vaccination had significant effects aligns with trials of patient portal or text reminders for influenza vaccination and with other studies of vaccination reminders.15,16,17

In this study, standard PCP outreach messages had similar effects as culturally tailored PCP outreach messages. The standard messages were carefully crafted based on principles from social and behavioral science, and included key topics, such as prompting recipients to commit to action, highlighting risks from COVID-19, and addressing concerns related to vaccine hesitancy.8,9,18 Relative to these well-developed messages, the culturally tailored messages did not lead to significantly higher vaccination rates, possibly because their incremental amount of content was limited.

These findings lend credence to the suggestion that PCP outreach may particularly benefit Black and Latino adults,6 who tend to have higher rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy than others.19,20,21,22,23 Still, this intervention’s effects were relatively modest. Increasing COVID-19 vaccination rates for these groups likely will require more intensive approaches, including real-time conversations and community-based outreach, as well as behavioral nudges.24,25,26,27,28 Language-concordant telephone outreach may warrant evaluation in future studies. Once a person has developed openness to being vaccinated, outreach approaches like those studied here may be important catalysts to following through.29

Limitations

This study has some limitations. The study population was highly diverse, although individuals with low income were somewhat underrepresented. As an integrated system, KPNC is well-positioned to support PCP outreach for COVID-19 vaccination and other preventive services via regional systems. Virtually all individuals in this setting have PCPs; similar results may not be possible for persons without primary care access. Still, the outreach strategies described here could be adopted by many other organizations at smaller or similar scales.

During the study period, other interventions to promote COVID-19 vaccination were undertaken within the health care system by individual physicians and service areas, and at the community level by counties. However, such interventions were likely not applied differentially across the groups assessed in this randomized trial. In addition, these findings should be interpreted in the context of the evolving nature of COVID-19 vaccine intentions30 and the US vaccination campaign.

This study included older adults who were Black or Latino; the findings may not be generalizable to other racial and ethnic groups or to younger adults. A contemporaneous randomized clinical trial we conducted of older adults who were Asian, White, or other races found no significant difference in vaccination rates between the standard PCP outreach and usual care groups.

Conclusions

This randomized clinical trial found that electronic secure message and mail outreach by PCPs increased COVID-19 vaccination rates among Black and Latino older adults. As many adults remain unvaccinated, information and invitations from PCPs and others may continue to play an important role in optimizing vaccination rates.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Escobar GJ, Adams AS, Liu VX, et al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 testing and outcomes : retrospective cohort study in an integrated health system. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(6):786-793. doi: 10.7326/M20-6979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossen LM, Ahmad FB, Anderson RN, et al. Disparities in excess mortality associated with COVID-19—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(33):1114-1119. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7033a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Demographic characteristics of people receiving COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Accessed October 9, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-demographic

- 4.Brunson EK, Buttenheim A, Omer S, Quinn SC; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Strategies for Building Confidence in the COVID-19 Vaccines. National Academies Press; 2021. doi: 10.17226/26068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Opel DJ, Lo B, Peek ME. Addressing mistrust about COVID-19 vaccines among patients of color. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(5):698-700. doi: 10.7326/M21-0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein S, Hostetter M. The room where it happens: the role of primary care in the next phase of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. Commonweath Fund. July 7, 2021. Accessed October 9, 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/jul/room-where-it-happens

- 7.Bogart LM, Ojikutu BO, Tyagi K, et al. COVID-19 related medical mistrust, health impacts, and potential vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86(2):200-207. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cialdini RB. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. Collins Business; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263-291. doi: 10.2307/1914185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escobar GJ, Gardner MN, Greene JD, Draper D, Kipnis P. Risk-adjusting hospital mortality using a comprehensive electronic record in an integrated health care delivery system. Med Care. 2013;51(5):446-453. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182881c8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirsch RM, DeCicco L. EGRET SIZ Reference Manual: Manual Revision 10. Statistics and Epidemiology Research Corporation; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Self SG, Mauritzen RH, Ohara J. Power calculations for likelihood ratio tests in generalized linear models. Biometrics. 1992;48:31-39. doi: 10.2307/2532736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dai H, Saccardo S, Han MA, et al. Behavioural nudges increase COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature. 2021;597(7876):404-409. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03843-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos HC, Goren A, Chabris CF, Meyer MN. Effect of targeted behavioral science messages on COVID-19 vaccination registration among employees of a large health system: a randomized trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2118702. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.18702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stockwell MS, Kharbanda EO, Martinez RA, Vargas CY, Vawdrey DK, Camargo S. Effect of a text messaging intervention on influenza vaccination in an urban, low-income pediatric and adolescent population: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307(16):1702-1708. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szilagyi PG, Albertin C, Casillas A, et al. Effect of patient portal reminders sent by a health care system on influenza vaccination rates: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):962-970. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobson Vann JC, Jacobson RM, Coyne-Beasley T, Asafu-Adjei JK, Szilagyi PG. Patient reminder and recall interventions to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:CD003941. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003941.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischhoff B, Northington Gamble V, Schoch Spana M; National Academies of Sciences Engineering, and Medicine . Understanding and Communicating About COVID-19 Vaccine Efficacy, Effectiveness, and Equity. National Academies Press; 2021. doi: 10.17226/26154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daly M, Jones A, Robinson E. Public trust and willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 in the US from October 14, 2020, to March 29, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325(23):2397-2399. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.8246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamel L, Lopes L, Sparks G, et al. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: September 2021. KFF. September 28, 2021. Accessed October 9, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-september-2021/

- 21.Kricorian K, Turner K. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and beliefs among Black and Hispanic Americans. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0256122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Momplaisir FM, Kuter BJ, Ghadimi F, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in 2 large academic hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2121931. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson HS, Manning M, Mitchell J, et al. Factors associated with racial/ethnic group-based medical mistrust and perspectives on COVID-19 vaccine trial participation and vaccine uptake in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2111629. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferdinand KC, Nedunchezhian S, Reddy TK. The COVID-19 and influenza “twindemic”: barriers to influenza vaccination and potential acceptance of SARS-CoV2 vaccination in African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(6):681-687. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fields J, Gutierrez JR, Marquez C, et al. Community-academic partnerships to address COVID-19 inequities: lessons from the San Francisco Bay Area. NEJM Catalyst. June 23, 2021. Accessed October 9, 2021. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/CAT.21.0135

- 26.Quinn SC, Andrasik MP. Addressing vaccine hesitancy in BIPOC communities—toward trustworthiness, partnership, and reciprocity. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(2):97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2103104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thaler RH, Sunstein C. Nudge: The Final Edition. Penguin; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volpp KG, Loewenstein G, Buttenheim AM. Behaviorally informed strategies for a national COVID-19 vaccine promotion program. JAMA. 2021;325(2):125-126. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.24036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Rothman AJ, Leask J, Kempe A. Increasing vaccination: putting psychological science into action. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2017;18(3):149-207. doi: 10.1177/1529100618760521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szilagyi PG, Thomas K, Shah MD, et al. Changes in COVID-19 vaccine intent from April/May to June/July 2021. JAMA. 2021;326(19):1971-1974. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.18761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

Data Sharing Statement