Abstract

Research with monolingual children has shown that early efficiency in real-time word recognition predicts later language and cognitive outcomes. In parallel research with young bilingual children, processing ability and vocabulary size are closely related within each language, although not across the two languages. For children in dual-language environments, one source of variation in patterns of language learning is differences in the degree to which they are exposed to each of their languages. In a longitudinal study of Spanish/English bilingual children observed at 30 and 36 months, we asked whether the relative amount of exposure to Spanish vs. English in daily interactions predicts children’s relative efficiency in real-time language processing in each language. Moreover, to what extent does early exposure and speed of lexical comprehension predict later expressive and receptive vocabulary outcomes in Spanish vs. English? Results suggest that processing skill and language experience each promote vocabulary development, but also that experience with a particular language provides opportunities for practice in real-time comprehension in that language, sharpening processing skills that are critical for learning.

Keywords: online lexical processing, dual language exposure, language dominance

Preliminary remarks

In the US, approximately three million children are growing up in bilingual homes and, according to the 2004 census of the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), this number is rapidly increasing. However, the course of language development in bilingual children is not well described or understood (McCardle & Hoff, 2006). The available research suggests that general features of bilingual children’s language development are similar to those of monolinguals. Nevertheless, language development in bilinguals, as in monolinguals, is characterized by substantial individual variability (e.g., Marchman & Martínez-Sussmann, 2002; Paradis, Genesee & Crago, 2011). Although accounting for individual differences has not been central to most theories of language development, it is increasingly clear that research on the causes and consequences of variation is vital for clarifying the mechanisms underlying language development (Bates, Bretherton & Snyder, 1988; Fernald & Marchman, 2011). For example, experimental studies with monolingual English and Spanish learners demonstrate that variability in language outcomes is linked to early proficiency in comprehending spoken language in real time (Fernald, Perfors & Marchman, 2006; Hurtado, Marchman & Fernald, 2007). Moreover, an important source of that variation is differences in early linguistic experiences (Hurtado, Marchman & Fernald, 2008). Here, we extend this research to bilinguals, exploring concurrent and developmental relations between variation in learning environments, vocabulary development, and language processing skill in English and Spanish bilinguals.

Variation in bilingual learning environments

Language experience matters, regardless of whether a child is growing up with one, two, or more languages. In monolingual learners, the pioneering longitudinal studies by Hart and Risley (1995, 1999) and Huttenlocher, Haight, Bryk, Seltzer and Lyons (1991) offered dramatic demonstrations that the quantity and quality of speech addressed to children is meaningfully related to linguistic and cognitive outcomes. Subsequent research has highlighted the significance of children’s early experience with language in promoting language development (e.g., Hoff, 2003, 2006; Fernald & Weisleder, 2011; Rodríguez, Tamis-LeMonda, Spellmann, Pan, Raikes, Lugo-Gil & Luze, 2009; Rowe, 2008).

Despite evidence that early language experience is critical for children learning a single language, fewer studies of comparable scope exist for children growing up with more than one language. One source of variation for children in dual-language environments is differences in the degree to which learners are exposed to each of their languages (e.g., Hoff, Core, Place, Rumiche, Señor & Parra, 2012; Patterson & Pearson, 2004). While some bilingual children hear one language much more often than the other, or in more diverse contexts, others may experience more balanced exposure. The languages used by the conversational partners may contribute to variation in outcomes. While some children consistently hear one of their languages from only a single caregiver, others hear both languages from many different people with whom they interact to differing extents (de Houwer, 2009). Given the heterogeneity of dual-language contexts, documenting the language learning environments of bilingual children is a daunting task.

An increasing number of studies have explored the complex interplay of the multiple factors in the learning environments of bilingual children that could support or hinder their language learning (Bedore, Peña, Summers, Boerger, Resendiz, Greene, Bohman & Gillam, 2012; de Houwer, 2007; Place & Hoff, 2011; Song, Tamis-LeMonda, Yoshikawa, Kahana-Kalman & Wu, 2011). Although it is well-established that children’s relative exposure to each language predicts development in those languages (de Houwer, 2009; Elin Thordardottir, 2011; Gathercole & Thomas, 2009; Hoff et al., 2012; Pearson, Fernández, Lewedeg & Oller, 1997), the nature and extent of those links depend on which outcomes are considered and how exposure is measured. In an early seminal study, Pearson et al. (1997) showed that differences in parents’ global estimates of relative exposure to each language were related to children’s vocabulary size in one language versus the other. In their sample of 25 Spanish–English bilinguals aged between eight and 30 months, they found that children who had experienced proportionately more of their overall daily interactions in Spanish had more reported words produced in Spanish than in English. More recently, Elin Thordardottir (2011) also found strong relations between amount exposure and vocabulary outcomes in five-year-old French–English bilinguals, although different relations were observed for expressive than receptive vocabulary. And while some researchers have maintained that relative amount of exposure to each language predicts grammar as well as vocabulary outcomes (Elin Thordardottir, Rothenberg, Rivard & Naves, 2006; Gutiérrez-Clellen & Kreiter, 2003; Hoff et al., 2012; Marchman, Martínez-Sussmann & Dale, 2004), others argue that syntactic development is less influenced by exposure patterns than is vocabulary (e.g., Paradis & Genesee, 1996). Recent work indicates, moreover, that exposure may be differentially related to vocabulary and grammar outcomes depending on whether one defines exposure in terms of children’s opportunities to use each language versus what languages they hear from others (Bedore et al., 2012).

The assessment of bilingual language environments

Estimates of young bilingual children’s exposure to each language are often based on caregiver reports of general features of the child’s language environment, e.g., “What language does the mother use when she speaks to this child?” (Duursma, Romero-Contreras, Szuber, Snow, August & Calderon, 2007). Other approaches enable more comprehensive documentation of the relative contribution of various sources of exposure to each language that bilingual children experience in their daily activities. One technique is a “day-in-the-life” interview in which parents are asked to describe, for each portion of a typical week and weekend day, each person with whom the child interacts and the languages that are used by that person (e.g., Gutiérrez-Clellen & Kreiter, 2003; Marchman & Martínez-Sussmann, 2002; Restrepo, 1998). The number of hours of exposure to each language is then summed across all individuals, and a proportion score is derived which represents the portion of the child’s total daily interactions with others that occur in one vs. the other language. Others have used this type of technique to obtain estimates that capture the cumulative history of exposure to each language, summing across periods of the child’s life since birth (Elin Thordardottir et al., 2006). Still other researchers have sought to move away from parent reports, asking parents instead to complete a language diary over the course of several weeks, indicating for each 30-minute period who is speaking to the child, what language is used, and the context of the interaction (de Houwer, 2007; Place & Hoff, 2011). In all of these techniques, the proportion of children’s total experiences in each language is computed across many different contexts and speakers. While much is left to be learned about their validity, such estimates are likely to provide more nuanced and detailed views of bilingual children’s daily lives than global estimates. Moreover, following studies with adults (e.g., Flege, MacKay & Piske, 2002), these proportions can also be expressed as ratios. For example, a Spanish/English bilingual child hearing equal amounts of both languages would have a Spanish:English (S:E) language exposure ratio of 1 to 1 (or 1:1). For bilinguals with less balanced input, a child who hears twice as much Spanish as English would have an S:E language exposure ratio of 2:1, while a child who hears half as much Spanish as English would have an S:E language exposure ratio of 0.5:1. Since ratio scores are naturally highly positively skewed, they are typically log-transformed prior to statistical analyses, yielding scores that have a midpoint of 0. Here, a child who hears more Spanish than English would have a positive log-transformed ratio, whereas, a child who hears more English than Spanish would have a negative score.

The assessment of language outcomes in bilingual learners

To determine children’s level of skill in each of their languages, many studies of bilingual language development use standardized assessments. While these techniques can provide relevant information, they may also introduce task demands or contextual biases that limit their usefulness in studies of very young learners or children from diverse backgrounds. For these reasons, research on bilingual language development in the toddler period has relied more on parent-report questionnaires such as the English-language MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories (CDIs, Fenson, Marchman, Thal, Dale, Reznick & Bates, 2007) and their Spanish-language analogues, the Inventarios del Desarrollo de Habilidades Comunicativas (Jackson-Maldonado, Thal, Marchman, Newton, Fenson & Conboy, 2003). The CDIs and Inventarios ask caregivers to report on their child’s current level of vocabulary and grammatical skill. Such instruments have a number of inherent advantages and have been shown to have moderate to strong validity in monolingual as well as bilingual English- and Spanish-learning children (e.g., Dale, 1991; Guiberson, Rodríguez & Dale, 2011; Jackson-Maldonado et al., 2003; Marchman & Martínez-Sussmann, 2002). For bilingual learners of English and Spanish, these instruments can be used in tandem to estimate children’s vocabulary knowledge in both languages. A child’s relative vocabulary can then be computed by taking the ratio of the number of words the child is reported to say that are in Spanish relative to the number reported in English (e.g., Pearson et al., 1997). Again, a child who produces more words in Spanish would have an S:E vocabulary log-transformed ratio greater than 0, while a child who knows fewer Spanish than English words would have an S:E vocabulary ratio less than 0.

Although early word production is an important indicator, it is also vital to establish what bilingual children can understand in each of their languages. Early receptive and expressive skills tend to be only moderately correlated in monolingual children (e.g., Bates et al., 1988; Jackson-Maldonado et al., 2003). Moreover, recent studies with Spanish-learning bilingual children suggest that their proficiency levels may be underestimated when only productive skills are taken into account (e.g., Elin Thordardottir, 2011; Oller & Eilers, 2002; Song et al., 2011). Assessing early comprehension in infants and toddlers can be exceedingly challenging. Offline behavioral tasks are useful with preschoolers and older children but are more difficult to administer to toddlers younger than two-and-a-half years old. While parent-report instruments are effective in assessing language production, concerns have been raised about their reliability and validity in assessing early comprehension (Tomasello & Mervis, 1994). Moreover, none of these techniques yields an index of children’s skill at understanding language in the context of real-time comprehension. Fortunately, recent refinements in experimental methodologies have yielded measures that monitor the time course of language understanding by very young language learners as they process speech in real time (Fernald, Zangl, Portillo & Marchman, 2008).

Online processing in monolingual and bilingual learners

Real-time language comprehension has long been of central interest in psycholinguistic research with bilingual adults, and there is now growing interest in the development of online language processing skills by young bilingual infants and children as well (Werker & Byers-Heinlein, 2008; Kovács & Mehler, 2009). In research using the “looking-while-listening” (LWL) procedure, children sit on their parent’s lap and look at pictures while they listen to speech naming one of the pictures (e.g., Where’s the doggie? or ¿Dónde está el perro?). Several studies using this method with monolingual English- and Spanish-speaking children have shown that toddlers get faster at identifying the referents of familiar words presented in continuous speech over the second year of life (Fernald, Pinto, Swingley, Weinberg & McRoberts, 1998; Hurtado et al., 2007). Moreover, children’s early efficiency in lexical processing is associated not only with faster vocabulary growth but also with long-term language and cognitive outcomes (Fernald et al., 2006; Marchman & Fernald, 2008; Marchman, Fernald & Hurtado, 2013). The predictive significance of early processing efficiency has been further confirmed with late talkers, who were at or below the 20th percentile in word production at 18 months. English-speaking late talkers who were relatively less skilled in speech processing at 18 months were more likely to remain at risk for language delays by two-and-a-half years, as compared to late-talking peers who were relatively more skilled in speech processing at 18 months (Fernald & Marchman, 2012). Such links demonstrate that efficient real-time processing is an important factor in language learning for children across a range of developmental levels.

Do similar associations exist between early vocabulary skill and language processing in children learning two languages? Marchman, Fernald and Hurtado (2010) extended the investigation of early speech processing to a diverse sample of 30-month-old children learning Spanish and English at the same time. Using identical procedures as in studies with monolingual learners, they found strong relations between lexical processing speed and vocabulary knowledge WITHIN each of the child’s languages. That is, children’s efficiency in processing Spanish words was related to the size of their production vocabulary in Spanish, and children’s efficiency in processing words in English was related to the size of their vocabulary in English. However, vocabulary size and processing efficiency were not related ACROSS the two languages, suggesting that these skills are specific to the language in which they are being used at this early age.

The Marchman et al. (2010) study was the first to look at real-time language comprehension abilities in young simultaneous bilinguals, focusing on relations between processing speed and vocabulary knowledge within English and within Spanish. However, links between processing skill in Spanish and Spanish vocabulary size were analyzed independently of the links between processing skill in English and English vocabulary size. While these analyses were important for identifying similarities in vocabulary-processing associations in monolinguals vs. bilinguals, that study did not examine children’s processing efficiency in one language IN RELATION to the other, i.e., how much faster or slower a bilingual child was at comprehending words in Spanish compared to words in English. Some bilingual children may be equally fast or slow in interpreting familiar words in the two languages. Other children may be more efficient in processing words in Spanish than in English, or show the opposite pattern with relatively faster reaction times to words in English compared to words in Spanish. By computing the ratios of speed of processing in Spanish vs. English, we can examine within-child patterns of RELATIVE ONLINE PROCESSING SKILL, as has been done in earlier studies of relative vocabulary knowledge in bilingual children (e.g., Pearson et al., 1997).

In addition, the Marchman et al. (2010) study did not directly explore whether differences in the amount of English or Spanish the children were experiencing accounted for individual variation in processing or vocabulary skill. While bilingual exposure patterns have been shown to predict vocabulary outcomes (e.g., Pearson et al., 1997), the current study is the first to explore whether bilingual children’s relative exposure also relates to their relative skill in comprehending vocabulary words in real time. Links between amount of language exposure and real-time comprehension using the LWL task were first examined in monolingual Spanish-learning infants by Hurtado et al. (2008), who video-recorded Latino mothers of 18-month-olds as they played with their child for 20 minutes in a laboratory session. Those children whose mothers spoke more during the play session had larger vocabularies and were significantly faster in online comprehension six months later than those who had heard less maternal talk. These results suggested that richer caregiver talk not only provides more new words as models for vocabulary learning, but also sharpens the processing skills used in real-time language comprehension. Improved facility with real-time comprehension may help the young language learner make more efficient use of the information in the language that they hear, leading to larger vocabularies and more flexible language use. More recently, Weisleder and Fernald (in press) further demonstrated, again with monolingual Spanish-learners, that processing efficiency mediates the relation between speech to children and vocabulary outcomes. In other words, the variation in children’s early experiences that is linked to later vocabulary development overlaps with the variation in children’s processing efficiency. These results show that individual differences in processing efficiency may help to explain the robust relation between language experience and vocabulary.

As in other studies with monolingual learners, Hurtado et al. (2008) derived estimates of amount of absolute language exposure from a brief interaction between mother and child in a laboratory-based play session. However, for a bilingual child, it is unlikely that a single laboratory session could provide a valid estimate of the relative exposure to the two languages in that child’s daily life, given that experiences in each language can vary as a function of who is with the child, the time of day, and the context of interaction, among other factors. For this reason, the current study used a version of the “day in the life” interview designed to estimate children’s relative exposure to English vs. Spanish across all speakers who currently interact with the child on a regular basis (e.g., Hoff et al., 2012; Marchman et al., 2004).

While the Marchman et al. (2010) study examined relations between processing skill and vocabulary at only one age, 30 months, the current study provides data on Spanish–English bilinguals at both 30 and 36 months, enabling us to explore both concurrent and developmental relations in these skills. We also extend the assessment of vocabulary knowledge to both the expressive and receptive domains. Parents were asked to report on the words children can say in each language using two parallel parent report questionnaires. These instruments yield estimates of vocabulary production in Spanish and English at 30 and 36 months, allowing us to examine associations between processing skill and expressive vocabulary in ways that are analogous to earlier studies of monolingual and bilingual children. At the 36-month time point, we also incorporated measures of receptive vocabulary knowledge using two similarly-structured standardized assessments in English and Spanish. Other recent studies have contrasted links between relative language exposure and receptive vs. expressive vocabulary in bilingual five-year-olds learning both English and French (Elin Thordardottir, 2011). The current study is the first to examine how relative language exposure relates to relative online processing efficiency as well as to offline vocabulary measures in younger Spanish–English bilinguals.

Overview

In this study, we examined parent-report measures of language exposure and both parent-report and standardized tests of vocabulary knowledge, in conjunction with measures of real-time lexical processing efficiency in both languages. Importantly, all of these measures – exposure, vocabulary size, and processing efficiency – are captured in RELATIVE terms for our analyses here. Our vocabulary measures are derived from the Spanish and English vocabulary tests taken together to provide an index of how many Spanish words a child knows in relation to how many English words she knows. Similarly, our measure of processing efficiency reflects children’s performance on the Spanish and English versions of the processing experiments, yielding an index of children’s speed of accessing Spanish words in relation to their speed of accessing English words. These relative measures are designed specifically to parallel the relative estimate of language exposure commonly used in bilingualism research, namely how much time a child spends in one language in relation to how much time she spends in the other. Casting all measures in relative terms enables us to address three key questions using analogous measures:

Is children’s relative facility in processing English vs. Spanish related CONCURRENTLY to their relative expressive and receptive vocabulary?

How are these skills shaped by children’s pattern of exposure to English vs. Spanish? Does relative exposure align with children’s relative expressive vocabulary, as found by Pearson et al. (1997)? Does relative exposure also predict vocabulary comprehension assessed in a standardized behavioral task, as found by Elin Thordardottir (2011) in somewhat older English–French bilinguals? Finally, do links between patterns of children’s language experiences and outcomes extend to real-time lexical processing, a question not previously explored?

What are the DEVELOPMENTAL links between exposure patterns, processing efficiency and vocabulary outcomes? Is children’s relative skill in early processing a significant predictor of LATER receptive and expressive vocabulary? Does early processing skill account for variance in outcomes BEYOND that attributable to early exposure patterns? To what extent does variance in early reaction time (RT, the time it takes to initiate a shift to the correct picture) OVERLAP with variance in exposure, offering an explanation for why early experience may facilitate learning?

Method

Participants

The data in this study were gathered as part of a longitudinal study of language development in children with regular exposure to both Spanish and English from birth. Participants were 37 children (19 females) tested at 30 months, for 29 of whom data were also available at 36 months. All children were reported to be typically developing. Sixty percent of the children were first-born and 89% lived with both parents. Based on parent report, 90% of the children were Latino, 5% were Asian, and 5% were Non-Latino White. Nearly half of the mothers and fathers were born in Mexico, about one-third were born in the US, with the rest of the parents born in Central or South America or in Spain. Approximately 70% of the mothers and 54% of the fathers were native speakers of Spanish, although 78% of mothers and 81% of fathers reported native or high proficiency in both Spanish and English.

On average, the sample was middle-class, but a range of SES levels was represented. While 22% of mothers and 24% of fathers had less than a high school education, 62% of mothers and 58% of fathers reported some college, with 6 fathers and 6 mothers reporting advanced degrees. Scores on the Hollingshead Four Factor Index of Social Status (Hollingshead, 1975) spanned nearly the full range of possible values from 18 to 66 (M = 40.6, SD = 16.6).

The study was conducted in a community laboratory located in a family neighborhood a few miles from a university campus. Over 50% of the residents in this community are Latino, many recent immigrants to the US from Mexico. The center is staffed by fully bilingual/bicultural researchers who communicate with the families in their preferred language. Families were recruited through county birth records, community health facilities, preschools, library programs, and word-of-mouth. At each age, testing was conducted in two sessions, one in Spanish and one in English, approximately one week apart. Research assistants (RAs) consistently addressed the child only in Spanish or English, as appropriate for the given session.

Measures

Language exposure

Following Marchman et al. (2004) and others, we conducted a language environment interview in the parent’s preferred language at both ages. The interview began with the RA asking about the child’s typical wakeup, nap, and night time schedules. Then, she inquired about each person in regular contact with the child, asking how much time they spent with him/her, and whether they addressed the child in English, Spanish or both in particular contexts of interaction. A proportion score for Spanish exposure was calculated by dividing the total number of person hours per week in Spanish over the total number of person hours in Spanish and English across all sources (excluding TV). To facilitate comparison with the other measures, this proportion score was then converted to a Spanish:English (S:E) ratio. Thus, a child who experienced 50% of daily interactions in Spanish and 50% in English would have an S:E language-exposure ratio of 1:1. A more Spanish-dominant child who experienced, for example, 75% of daily exposure in Spanish would have a ratio of 3:1, while an English-dominant child who heard 75% English and 25% Spanish would have an S:E language-exposure ratio of 0.33:1. Since the distribution of these ratios is highly skewed, the ratio scores were log-transformed. In these log-transformed scores, a positive S:E ratio greater than 0 reflects a Spanish advantage, whereas, a negative S:E ratio reflects an English advantage.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the proportion of Spanish (vs. English) exposure at each age point, as well the corresponding log-transformed exposure ratios. Consistent with the fact that most of our parents were native speakers of Spanish, mean proportion scores indicate that this sample of children was exposed to somewhat more Spanish than English on average. Mean ratio scores were slightly positive, also reflecting a modest Spanish dominance pattern for the group as a whole. Nevertheless, levels ranged from 85% Spanish, 10% English to 90% Spanish, 10% English. At 36 months, the mean language exposure proportion and ratio scores remained at about the same level as at 30 months on average, but there was again considerable variation across the sample with scores spanning the full possible range. We should note that the exposure patterns at these two ages were highly correlated, r(29) = .57, p < .0001, suggesting that exposure ratios overall were stable over this early time period for these particular children.

Table 1.

Mean, standard deviation (SD) and range of exposure to Spanish at 30 and 36 months.

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Exposurea | ||

| 30 months | ||

| Spanish proportion | 56.8 (20.7) | 10–85 |

| S:E Ratiob | 0.3 (1.0) | −2.2–1.8 |

| 36 months | ||

| Spanish Proportion | 55.1 (21.5) | 10–91 |

| S:E Ratiob | 0.2 (1.1) | −2.0–2.4 |

Proportion of reported hours of Spanish (vs. English) exposure based on “day in the life” interview at 30 and 36 months.

Spanish exposure proportion divided by English exposure proportion (log-transformed).

Vocabulary

At both ages, caregivers completed two vocabulary questionnaires: the MacArthur-Bates CDI Inventario II in Spanish, and Words & Sentences in English. Each instrument was completed by the caregivers who regularly spoke that language with the child. In addition, parents were asked to consult with other adults who frequently spoke either Spanish or English or both with the child when completing the respective questionnaires. Production vocabulary was the number of words reported as “comprende y dice” or “understands and says” (out of 680). A vocabulary ratio was computed by dividing raw vocabulary in Spanish by raw vocabulary in English. Since these ratios were also strongly positively skewed, the values were then log-transformed to normalize the distributions as appropriate for statistical analyses. As with exposure, a positive ratio score indicates that the child was reported to speak more words in Spanish than in English, while those children with negative ratios were those with more English-dominant vocabularies.

Receptive vocabulary scores were also available for a subset of 24 children at 36 months based on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 3rd Edition (PPVT III) in English, and the Test de Vocabulario en Imágenes (TVIP) in Spanish. Standard scores were derived for each language score using monolingual norms (Dunn & Dunn, 1997; Dunn, Padilla, Lugo & Dunn, 1986). To capture children’s relative receptive abilities in Spanish vs. English, ratios were computed by taking the standard score in Spanish and dividing it by the English standard score and then log-transformed. Positive S:E receptive vocabulary ratios indicate relatively better performance in Spanish than English, and negative ratios indicate relatively higher scores in English than Spanish.

Spoken language processing

Children’s efficiency of spoken language understanding was assessed using the LWL procedure, once in Spanish and once in English, during two separate visits. All testing procedures and stimuli were identical at 30 and 36 months. Children sat on their parent’s lap and viewed pairs of pictures on a screen as they listened to speech in either Spanish or English naming one of the pictures (see Fernald et al., 2008). Children’s looking patterns were video-recorded and coded offline later. During testing, the parent wore opaque sunglasses to obstruct their view of the images. The order of the testing sessions at each age was established on an individual basis, with the first visit conducted in the child’s strongest language as reported by the parent.

The target words consisted of translation equivalents for 10 nouns typically familiar to both Spanish- and English-learning children in this age range (la manzana, apple; el globo, balloon; el plátano, banana; el pájaro, bird; el carro, car; la galleta, cookie; la vaca, cow; la rana, frog; el caballo, horse; el jugo, juice; el zapato, shoe; la cuchara, spoon) (Dale & Fenson, 1996; Jackson-Maldonado et al., 2003). To verify that the target words were familiar to each participant, parents completed additional questionnaires at each age indicating whether their child understood and said the stimulus words in English and in Spanish. While some children were reported to not produce some of the words in one or both languages, all children were reported to understand all target words.

In both Spanish and English stimuli, 24 trials consisted of familiar carrier frames with target nouns occurring in sentence-final position (e.g., ¿Dónde está el carro?, Where’s the car?). On an additional 16 trials, the carrier phrase also included a sentence-initial verb semantically related to the target noun (e.g., Cómete la galleta, Eat the cookie) or a color adjective (e.g., ¿Dónde está el carro azul?, Where’s the blue car?). All target nouns (Spanish M = 735 ms, range = 670–800 ms; English M = 720, 650–875) were presented in yoked pairs matched in duration and syllable length, and in Spanish, grammatical gender, except for eight familiar frame trials in which the target was paired with a noun of a different grammatical gender (e.g., el carro “car”/la pelota “ball”). Three filler trials were interspersed (e.g., ¿Te gustan las fotos? ¡Aquí vienen más!, Do you like the pictures? Here are some more!). A female native Spanish–English bilingual speaker recorded several tokens of each sentence in each language. Final tokens were chosen based on cross-token comparability in duration of the carrier phrase and target word.

Visual stimuli were identical in the Spanish and English sessions, consisting of digitized photographs of objects on gray backgrounds. Four different picture tokens were used for each target word, matched in size and brightness. Pictures were presented in pairs, with each object serving as both target and distracter. Side of target picture was counterbalanced across trials. Trials were presented in one of two pseudo-random orders, counterbalanced across participants. On the critical trials, the pictures were shown in silence for two seconds, continuing for one second after sentence offset, for a total trial duration of five–seven seconds. Each session lasted about five minutes.

Using custom software, children’s eye-movements were coded offline without sound by highly-trained observers blind to side of target picture. On each frame, coders noted whether the child was fixating the right or left picture, between the pictures, or away from both. At each age, a second coder re-coded the entire session for 25% of the participants; half of these sessions were in Spanish and half in English. Inter-coder reliability across languages and ages was 96% overall.

Trials are then categorized based on where the child was looking at the onset of the target word. Trials on which the child was not fixated on one of the pictures were eliminated (approximately 10% of trials) from analyses. All remaining trials were later flagged as target-or distracter-initial depending on where the child was looking at the onset of the informative word in each type of stimulus sentence, i.e., the onset of the first word in the sentence that was potentially sufficient to identify the target picture (noun, adjective, determiner or verb, depending on the trial type). Because the children cannot know in advance which picture will be asked about, approximately half the time they will be looking at the target picture and half the time they will be looking at the distracter picture when hearing the informative word. Mean RT to shift to the correct picture can only be calculated for distracter-initial trials, i.e., approximately half of the picture-initial trials. Moreover, only those distracter-initial trials where the child started on the distracter and shifted to the target picture within 300–1800 ms from informative word onset were included in analyses. Distracter-initial trials where children shifted sooner than 300 ms (approximately 4% of all trials) or later than 1800 ms (approximately 6% of all trials) from critical word onset were excluded from the computation of mean RT, since these early and late shifts are not likely to be in response to the stimulus sentence (see Fernald et al., 2008). Thus, final mean RTs were based on different numbers of trials across participants and sessions, although a comparable number of trials were included in the estimates for the Spanish vs. the English sessions at both age points, on average (Spanish 30 months: M = 10 trials, range = 4–21, 36 months: M = 10, 4–18; English 30 months: M = 9, 3–15, 36 months: M = 10, 4–15).

As with the measures of relative receptive and productive vocabulary, processing speed was calculated as a relative measure of mean RT in Spanish vs. English. An S:E processing speed ratio was calculated by dividing the mean RT in Spanish by the mean RT in English at each age and then log-transformed. Since shorter RTs indicate faster processing, a positive S:E log-transformed ratio for RT indicates that children were relatively SLOWER to interpret Spanish than English words, showing relatively more efficient processing in English compared to Spanish. In contrast, a negative ratio reflects faster processing in Spanish compared to English, a Spanish-dominant pattern. Note that the interpretation of ratio values for processing efficiency is the reverse of those for vocabulary size and exposure, where positive ratios reflect a Spanish-dominant pattern.

Results

We begin by reporting results of the relative S:E vocabulary and processing measures separately, followed by correlational analyses to examine the links between them. We then outline a set of hierarchical regression models designed to assess the respective contributions of language exposure and processing speed to the development of vocabulary.

Receptive and expressive vocabulary

We first examine vocabulary outcomes in these Spanish-and English-learning bilingual children. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for reported vocabulary assessed on the CDIs at 30 and 36 months. At both ages, participants were reported to know somewhat more Spanish than English words, on average, as shown by the somewhat positive S:E ratio score. However, note that there was a considerable range across the sample, with some children reported to produce many more words in Spanish than in English and others producing many more English than Spanish words. Table 2 also presents mean scores on receptive vocabulary assessed on the PPVT and TVIP at 36 months. As with expressive vocabulary, children were slightly stronger in Spanish than English receptive vocabulary, on average. Note though that this difference was considerably less pronounced for lexical comprehension than production, and again, there was considerable range in both raw scores and S:E log ratios. Finally, we report that S:E ratios in expressive vocabulary at 30 months were strongly correlated with S:E receptive vocabulary ratios at 36 months, r(24) = .80, p < .001. That is, those children whose reported vocabulary production on the CDIs was relatively more advanced in Spanish than in English at 30 months were also relatively more advanced in comprehending Spanish than English words on the TVIP and PPVT at 36 months.

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviation (SD) and range of vocabulary in Spanish and English.

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Expressive vocabularya | ||

| 30 months | ||

| Spanish | 301.3 (187.0) | 4–676 |

| English | 292.5 (190.7) | 17–667 |

| S:E Ratiob | 0.1 (1.4) | −3.9–2.5 |

| 36 months | ||

| Spanish | 391.0 (187.2) | 135–679 |

| English | 369.4 (231.5) | 25–673 |

| S:E Ratiob | 0.2 (1.1) | −1.4–3.1 |

| Receptive vocabularyc | ||

| Spanish | 98.8 (9.2) | 87–120 |

| English | 84.9 (23.6) | 47–131 |

| S:E Ratiod | 0.2 (0.3) | −0.2–0.7 |

Number of words reported as “comprende y dice” or “understands and says” on the CDI: Inventario II (Spanish, Jackson-Maldonado et al., 2003) and CDI: Words & Sentences (English, Fenson et al., 2007) (30 months: n = 37; 36 months: n = 29).

Total words in Spanish divided by total words in English (log-transformed).

Standard scores on the TVIP (Spanish, Dunn et al., 1986) and PPVT–III (English, Dunn & Dunn, 1997) (36 months: n = 24).

Standard score on the TVIP divided by PPVT–III standard score (log-transformed).

Processing efficiency

We next explore bilingual children’s speed at processing words in real time. As shown in Table 3, the mean RTs for Spanish were slightly slower in Spanish than in English, on average, at both 30 and 36 months. However, a mean S:E ratio just slightly above 0 indicates that, as a group, children tended to be equally fast at accessing Spanish and English words in real time, similar to the generally balanced pattern we saw on the standardized receptive vocabulary measure. But again, the ranges indicated that there were considerable individual differences among children in their relative facility at processing Spanish vs. English words. Some children responded relatively more quickly to English than Spanish words, whereas, other children were nearly twice as fast at lexical comprehension in Spanish as in English. We next examine whether these individual differences in children’s relative speed of spoken word recognition in Spanish vs. English were related to their relative expressive and receptive vocabulary skill.

Table 3.

Mean, standard deviation (SD) and range in RTa in Spanish and English.

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| 30 months | ||

| Spanish | 884 (191) | 617–1458 |

| English | 852 (186) | 540–1291 |

| S:E Ratiob | 0.04 (0.3) | −0.6–0.7 |

| 36 months | ||

| Spanish | 855 (136) | 542–1130 |

| English | 793 (130) | 546–1020 |

| S:E Ratiob | 0.1 (0.3) | −0.4–0.5 |

Mean latency (RT) to initiate an eye-movement (ms) on distracter-initial trials.

RT in Spanish divided by RT in English (log-transformed).

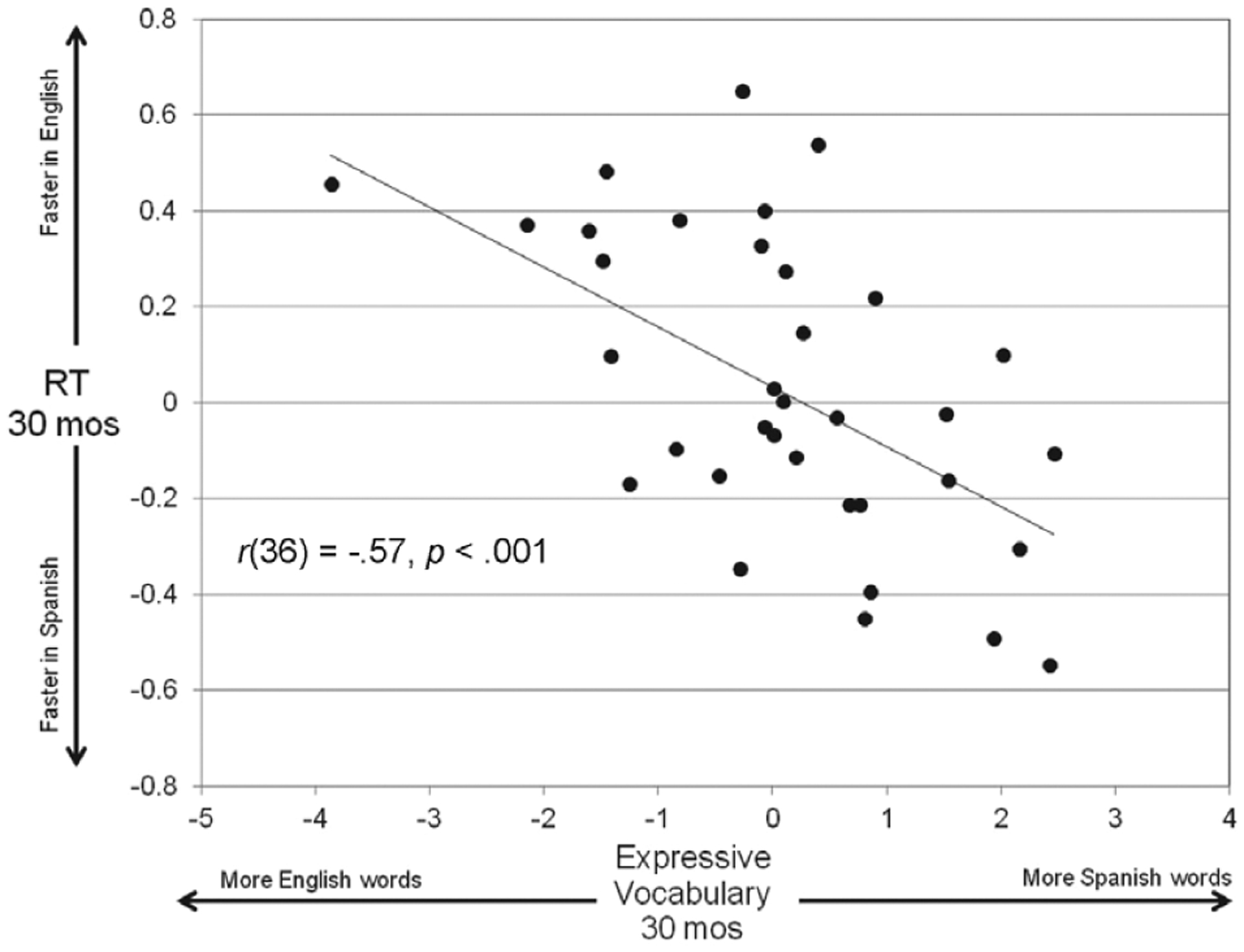

Links between relative vocabulary size and relative processing speed in Spanish vs. English

How did children’s relative skill in online processing align with their relative productive vocabulary? As shown in Figure 1, 30-month-olds who were more skilled in real-time interpretation of words in Spanish as compared to English were also more advanced in producing words in Spanish as compared to English, r(36) = −.54, p < .001. Similar links were found between S:E log ratios in mean RT and in both expressive, r(29) = −.53, p < .003, and receptive vocabulary, r(24) = −.60, p < .002, at 36 months. These findings offer additional evidence that children’s success at building a lexicon is closely tied to their efficiency in accessing words during real-time comprehension, effects that were observed at both 30 and 36 months and with measures of both receptive and expressive vocabulary size.

Figure 1.

Relation between log-transformed S:E ratios in expressive vocabulary and S:E ratios in processing speed in response to Spanish vs. English words at 30 months.

Links between relative vocabulary size and relative language exposure in Spanish vs. English

The results so far indicate that bilingual children’s speed in accessing known words in each of their two languages is associated with their relative vocabulary size in each language. To what extent are these within-child differences in S:E ratios in vocabulary and processing measures associated with differences in their daily experiences in Spanish vs. English? Consistent with Pearson et al. (1997), we find strong relations between S:E ratios in language exposure and S:E ratios in expressive vocabulary at both 30 months, r(36) = .59, p < .001, and 36 months, r(29) = .62, p < .001. S:E exposure ratios were also correlated with ratio of receptive vocabulary based on the PPVT/TVIP at 36 months, r(24) = .59, p < .01. Thus, at two ages and for two measures of vocabulary skill, we found that bilingual children who heard relatively more Spanish than English in their daily interactions with others also tended to be more successful at learning words in Spanish than English, whereas, children who heard more English tended to be more successful in English than Spanish.

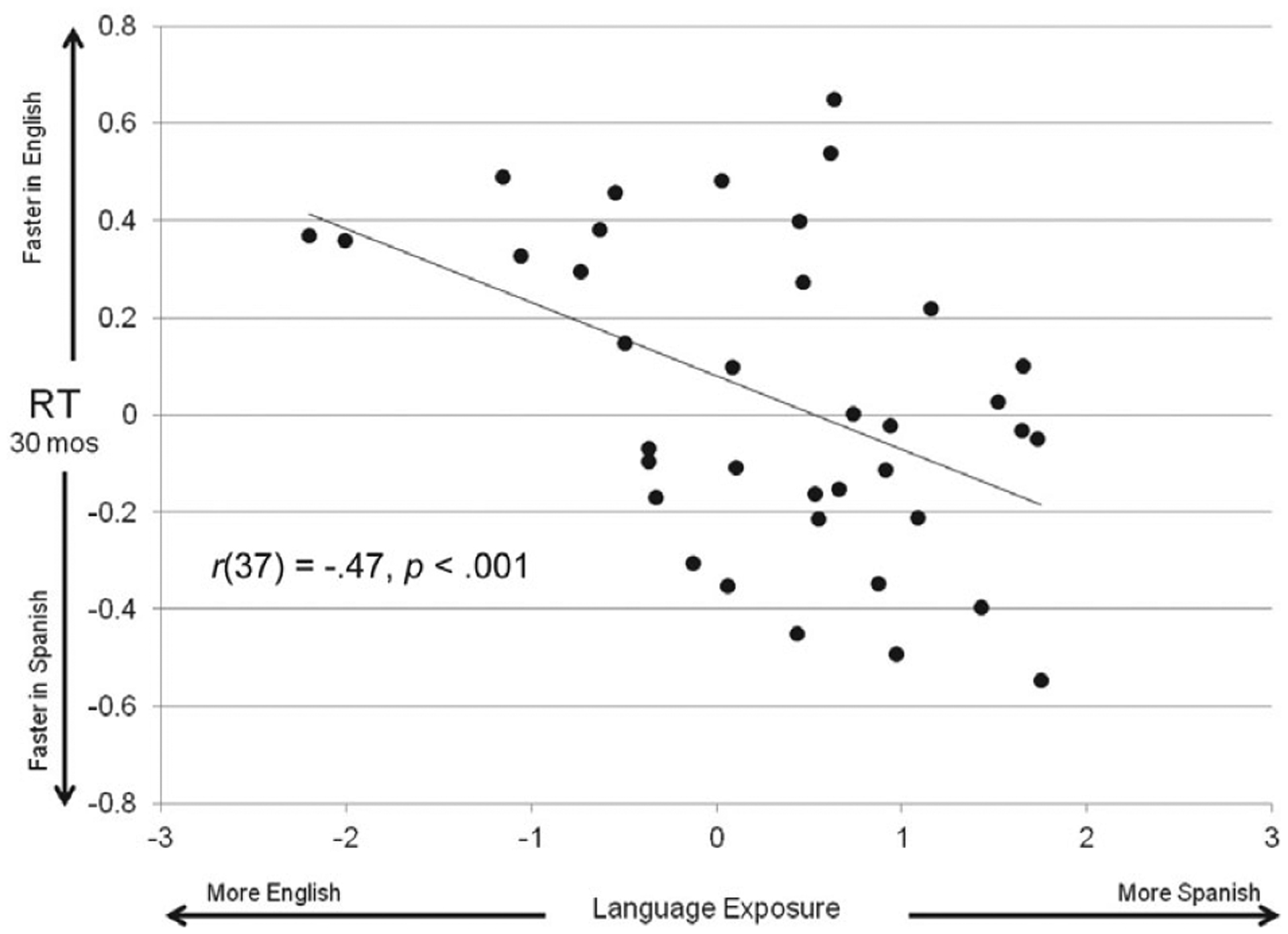

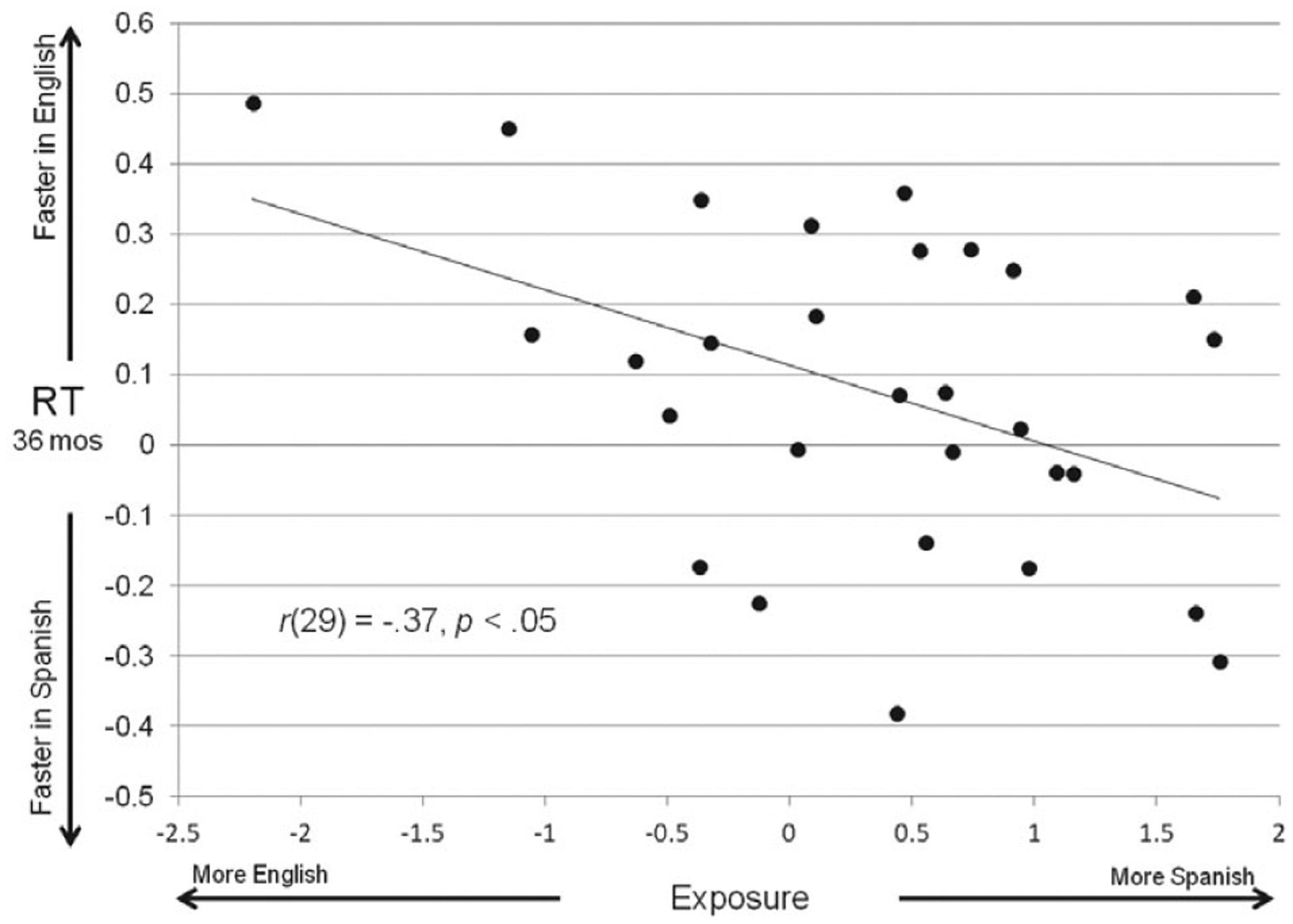

Links between relative processing speed and relative language exposure in Spanish vs. English

Was relative amount of exposure to Spanish vs. English also associated with children’s relative efficiency in real-time processing of familiar words in each language? Again, we found significant correlations between S:E language exposure ratios and S:E ratios in mean RT at 30 months, r(37) = −.47, p < .001, and 36 months, r(29) = −.37, p < .05. To illustrate, Figures 2 and 3 plot children’s S:E ratios in language exposure against their mean S:E ratios of RT in response to Spanish vs. English words at 30 and 36 months, respectively. As with vocabulary, these results show that bilingual children’s language-learning experiences are also linked to their across-language pattern of processing skills, a relation that has not been previously documented. That is, at both 30 and 36 months, the variability in how much Spanish vs. English children heard in daily interactions at home was associated with variation in children’s relative speed of processing of Spanish and English words.

Figure 2.

Relation between log-transformed S:E ratios in language exposure patterns and S:E ratios in processing speed in response to Spanish vs. English words at 30 months.

Figure 3.

Relation between log-transformed S:E ratios in language exposure patterns and S:E ratios in processing speed in response to Spanish vs. English words at 36 months.

Developmental relations between S:E ratios in language exposure, online processing speed and vocabulary

Our final goal was to explore the extent to which variation among children in their relative processing efficiency in Spanish vs. English is a significant predictor of later vocabulary outcomes in these young bilinguals, in relation to the patterns of relative exposure to Spanish and English they experience in daily interactions. Table 4 presents a series of hierarchical multiple regression models. Looking first at links to relative expressive vocabulary at 36 months, Model 1 shows that S:E language exposure ratio at 30 months was a significant predictor of S:E vocabulary ratio six months later. That is, the degree to which the children had relatively more exposure to Spanish at 30 months was associated with relatively larger Spanish vocabularies at 36 months, compared to children with less exposure to Spanish. Those children who experienced relatively more English tended to know more English than Spanish words, compared to those children with relatively less English exposure. This is perhaps not surprising given the strength of the concurrent link between exposure and vocabulary ratios at 30 months and the stability of the exposure measure reported earlier.

Table 4.

Multiple regression models (standardized Betas) with S:E ratios in language exposure patterns and S:E ratios in processing speed in response to Spanish vs. English words at 30 months as predictors of S:E ratios in expressive (n = 29) and receptive (n = 24) vocabulary at 36 months.

| 36 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative expressive vocabulary | Relative receptive vocabulary | |||

| 30-month predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| Relative language exposure | .58** | .45* | .43* | .20 |

| Relative processing speed (RT) | — | −.33* | — | −.49* |

| Total R 2 | .33 ** | .42 ** | .19 * | .37 ** |

p < .05;

p < .01

Model 2 asks whether relative processing skill at 30 months added significant predictive variance, over and above exposure. Exposure ratio remained a significant predictor, but knowing children’s relative processing speed at 30 months accounted for 9% unique variance in expressive vocabulary ratio at 36 months, a significant r2-change, F(1,26) = 6.5, p < .02. Thus, the degree to which children heard Spanish in their daily lives as well as how efficiently they were able to access familiar Spanish vs. English words in real time were both important determinants of relative productive vocabulary skill at three years in these bilingual children.

The next two models explore the predictors of S:E ratios in receptive vocabulary based on the TVIP and PPVT. Here, Model 3 again shows that relative amount of exposure to Spanish vs. English at 30 months is a significant predictor of relative skill in understanding Spanish vs. English words at 36 months. However, if the S:E ratio of processing speed at 30 months is added to the model (Model 4), the overall variance accounted for is nearly doubled, F(1,21) = 6.5, p < .02, with relative RT remaining the only significant predictor. Those children who had relatively higher scores on a test of receptive vocabulary in Spanish at 36 months were also more efficient in real-time understanding of Spanish words at 30 months, even beyond what their relative exposure would predict. Moreover, the fact that variation in children’s skill in processing Spanish vs. English words overlapped with that attributable to exposure suggests that children’s experience with a particular language provides critical opportunities for real-time practice in that language that have important implications for outcomes. In sum, these findings revealed that bilingual children’s relative skill at processing words in real time was linked to their subsequent vocabulary outcomes, both accounting for and adding to the role of experience in the two languages they are learning.

Discussion

For all bilingual children, vocabulary knowledge is distributed across two languages, yet the relative knowledge of the two languages varies substantially from child to child. Some children may be able to speak many more words in one language than in the other, whereas others may have more balanced vocabulary across their two languages. The first goal of this study was to ask whether relative vocabulary knowledge in Spanish vs. English was linked to children’s relative skill at processing words in these two languages. Relative vocabulary knowledge aligned closely with relative online processing efficiency. That is, those bilingual children who knew relatively more words in Spanish vs. English were also relatively more skilled at accessing Spanish vs. English words during real-time comprehension. We observed such links both with parent report measures of expressive vocabulary, as in earlier studies, and with standardized behavioral measures of receptive vocabulary. Thus, extending earlier results with monolinguals, these results indicate that regardless of whether a child is learning one language or two, receptive and expressive vocabulary knowledge are closely linked to lexical processing efficiency.

Our second goal was to explore the extent to which bilingual children’s relative skill in vocabulary and processing paralleled their relative exposure to Spanish vs. English. Indeed, those children who experienced relatively more Spanish in their daily lives tended to have relatively larger production vocabularies in Spanish than in English, while those children who heard more English tended to produce more English than Spanish words. Analogous findings were reported for assessments of lexical comprehension at 36 months using the PPVT and TVIP. Such results replicate earlier findings that relative exposure patterns align with parent report measures of lexical production in young Spanish learners (Pearson et al., 1997), extending the results to standardized measures of receptive vocabulary as in recent studies with French–English bilinguals (Elin Thordardottir, 2011).

In addition, the current study demonstrated that the influence of relative experience with two languages goes beyond how many words bilingual children can say or understand in each language. Patterns of exposure also help shape the relative facility with which these young bilingual children access words during a test of real-time lexical comprehension. This is the first study to document relations between patterns of language exposure and relative efficiency in lexical processing in young bilinguals that parallel those previously found between relative exposure and vocabulary. As in Hurtado et al. (2008) and Weisleder and Fernald (in press), our results provide further evidence that children’s experience interacting with caregivers in a particular language not only supports vocabulary learning, but also sharpens the skills that children employ when interpreting speech in real time.

Our third question focused on the nature of the developmental relations between these factors and later outcomes from 30 to 36 months. For vocabulary production, the results of hierarchical regression models showed that early exposure patterns and processing skill combine to work together to support later outcomes in young Spanish–English bilinguals, each contributing significant independent variance. It is perhaps not surprising that exposure to relatively more Spanish in children’s daily lives supports vocabulary learning by providing children with more opportunities to learn Spanish words. What the current study further demonstrates is that those children who are more efficient at processing Spanish than English words know relatively more words in Spanish, beyond what their exposure levels would predict. Thus, increased processing efficiency enables children to more effectively take advantage of whatever amount of Spanish they hear to gain expressive vocabulary knowledge in Spanish.

When predicting to receptive vocabulary at three years, individual variation in processing speed was also a significant predictor above and beyond exposure, adding 18% additional variance. However, these results revealed a slightly different pattern than with expressive vocabulary. In particular, including RT in the model reduced the effect of exposure, and RT remained the only significant predictor. This pattern of results suggests that it was specifically the variance in RT associated with different relative exposure which helped to drive children’s receptive vocabulary learning. On interpretation of this finding is that those children with relatively more exposure to Spanish than English had relatively higher scores on a test of Spanish vs. English receptive vocabulary precisely because of the benefits exposure offered them in strengthening their skill at processing words quickly and efficiently. While further research is necessary to fully explore the implications of these different patterns, our results are consistent with other studies that find differences in the links between learning environments and receptive vs. expressive outcomes (e.g., Elin Thordardottir, 2011; Gibson, Oller, Jarmulowicz & Ethington, 2012. Our findings also suggest that early processing efficiency might support receptive vs. expressive outcomes in different ways in young bilingual children.

These findings are consistent with Marchman et al. (2010), who demonstrated that processing efficiency and vocabulary outcomes in bilinguals are tightly linked, and add to the mounting evidence that skill in online processing is fundamental to children’s vocabulary learning, for both bilingual and monolingual learners. More significantly, these results mirror those of Hurtado et al. (2008) and Weisleder & Fernald (in press), but now with a bilingual population, in demonstrating that both language experience and processing efficiency are strongly associated to variation in vocabulary outcomes. As has been found for monolinguals then, the development of a working lexicon for young bilingual children is guided by children’s access to the information in the input that they hear (Hoff, 2006). We present here the first evidence that for bilinguals, as for monolinguals, more advanced processing skills may be the mechanism through which children learn through their environment. Practice with a particular language supports children’s early processing of that language which in turn, enables children to more efficiently access and make use of the cues to language structure and meaning. In other words, children with more efficient processing skills learn language more effectively because they are able to “do more with less” input than those children who are less efficient in early language comprehension.

While this was the first study to explore these links longitudinally, these children were only followed until the age of 36 months. Further studies should explore relations across a longer developmental time frame, examining the strength of links between early processing skill and language outcomes in bilingual children beyond the early preschool period. It remains an open question whether early processing efficiency is a strong predictor of outcomes in school-age for these bilingual children, as has been demonstrated in English- and Spanish-speaking monolinguals (e.g., Marchman & Fernald, 2008; Marchman et al., 2013).

Note that the measures of exposure that we have presented here seek to assess the amount of children’s daily experiences in English vs. Spanish based on a detailed parental interview. Although we expect that this technique provides a more accurate view of children’s exposure patterns than less comprehensive techniques, these estimates are nevertheless based on parents’ reports rather than our direct observations. It is possible that a different picture of the relations between exposure and outcomes would be obtained if we had the opportunity to directly survey children’s actual daily experiences. One goal of our ongoing research program is to compare estimates of exposure patterns across several different methods and to establish their concurrent and predictive validity.

Note also that the “day in the life” interviews provide information about the relative number of hours that a child spends in daily interactions with others in Spanish vs. English, not the absolute number of words or utterances that that child hears in each language. To illustrate this point, imagine a child who experiences about half of her daily interactions with speakers of Spanish and half with speakers of English. However, the nature of the interactions she has with her caregivers who speak Spanish is very different than what she experiences with her caregivers who speak English. It so happens that this child hears Spanish from very engaged caregivers who provide language-rich interactions for several hours each day. In contrast, the caregivers in her life who speak English tend to interact with her in a much less engaged way, resulting in fewer opportunities for exposure to rich vocabulary and varied grammatical structures in English. Thus, even though this child has bilingual exposure that is similar in terms of the number of hours that she hears Spanish vs. English, the absolute number of Spanish vs. English words and sentences that she hears, as well as the overall quality of the learning environment in those two languages, are very different. In studies of monolingual children, it is well-established that interactions with caregivers can vary in many ways that have a substantial influence on children’s outcomes (e.g., Hoff, 2006). Recent studies that have explored learning environments in bilingual children have shown that children’s outcomes are influenced by qualitative features of the input as well, for example, whether the child is hearing the language from a native vs. non-native speaker (Fernald, 2006; Place & Hoff, 2011). The extent to which caregivers engage in intersentential code mixing is also a feature of the input that may negatively influence children’s outcomes (Byers-Heinlein, 2012), although some studies find weak or no influence of the extent of code-switching (e.g., Genesee, 1989; Goodz, 1989).

Dissociations between estimates of hours of exposure and the quantity and quality of the speech that bilingual children actually experience could account for the moderate, albeit statistically reliable, correlations between exposure and outcomes seen in the current study These questions should be explored more deeply in studies examining features of the language learning environment that might influence bilingual children’s processing and vocabulary outcomes, adopting naturalistic and direct observation methods as much as possible. In our ongoing studies, we are gathering extensive natural language samples which enable day-long home recordings that capture speech to or near the child. Our goal is to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the daily experiences of these English- and Spanish-learning children and learn more about which quantitative and qualitative features of those experiences may impact language processing abilities in each language and which have implications for children’s developing linguistic knowledge.

In conclusion, this study is the first to present evidence in a bilingual population of the close associations between three critical aspects of language development: language exposure, processing efficiency and vocabulary knowledge. Our findings suggest that efficiency at processing language in real time reflects those mechanisms that enable a child to learn from the multiple cues to linguistic form, structure and meaning that are available in the talk that they hear. We demonstrated here that, for the bilingual child, the more exposure she receives to a given language, the faster she becomes at processing that language in real time, which in turn will lead to greater gains in vocabulary in that particular language. The fact that we find this evidence in bilingual children, as we do in monolinguals, further supports the view that language outcomes at this early age are intimately tied to the opportunities for practice in real-time processing that occur during interactions with others.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the children and parents who participated in this research. Special thanks to the reviewers and editors of this journal for their thoughtful comments and suggestions. Thanks to Adriana Weisleder, Lucía Rodríguez Mata, Ana Luz Portillo, Amber MacMillan, Renate Zangl, Lucia Martinez, Araceli Arroyo, and the staff of the Center for Infant Studies at Stanford University. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to Anne Fernald (HD 42235, DC 008838) with a Postdoctoral Research Supplement for Underrepresented Minorities to Nereyda Hurtado and a National Research Service Award (NRSA) to Theres Grüter (F32 DC010129-01).

Contributor Information

NEREYDA HURTADO, Stanford University.

THERES GRÜTER, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa.

VIRGINIA A. MARCHMAN, Stanford University

ANNE FERNALD, Stanford University.

References

- Bates E, Bretherton I, & Snyder L (1988). From first words to grammar: Individual differences and dissociable mechanisms. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bedore LM, Peña ED, Summers CL, Boerger KM, Resendiz MD, Greene K, Bohman TM, & Gillam RB (2012). The measure matters: Language dominance profiles across measures in Spanish–English bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15, 616–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers-Heinlein K (2012). Parental language mixing: Its measurement and the relation of mixed input to young bilingual children’s vocabulary size. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 16, 32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dale PS (1991). The validity of a parent report measure of vocabulary and syntax at 24 months. Journal of Speech and Hearing Sciences, 34, 565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale PS, & Fenson L (1996). Lexical development norms for young children. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 28, 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- de Houwer A (2007). Parental language input patterns and children’s bilingual use. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 411–424. [Google Scholar]

- de Houwer A (2009). Bilingual first language acquisition. Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, & Dunn LM (1997). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Third Edition (PPVT–III). Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Padilla E, Lugo D, & Dunn LM (1986). Test de Vocabulario en Imágenes Peabody (TVIP). Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Duursma S, Romero-Contreras A, Szuber PP, Snow C, August D, & Calderon M (2007). The role of home literacy and language environment on bilinguals’ English and Spanish vocabulary development. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Thordardottir Elin (2011). The relationship between bilingual exposure and vocabulary development. International Journal of Bilingualism, 15, 426–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordardottir Elin, Rothenberg A, Rivard M-E, & Naves R (2006). Bilingual assessment: Can overall proficiency be estimated from separate measurement of two languages? Journal of Multilingual Communication Disorders, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Marchman VA, Thal D, Dale PS, Reznick JS, & Bates E (2007). MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories: User’s guide and technical manual (2nd edn.). Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A (2006). When infants hear two languages: Interpreting research on early speech perception by bilingual children. In McCardle & Hoff; (eds.), pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, & Marchman VA (2011). Causes and consequences of variability in early language learning. In Arnon I & Clark EV (eds.), Experience, variation, and generalization: Learning a first language (Trends in Language Acquisition Research), pp. 181–202. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, & Marchman VA (2012). Individual differences in lexical processing at 18 months predict vocabulary growth in typically-developing and late-talking toddlers. Child Development, 83, 203–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Perfors A, & Marchman VA (2006). Picking up speed in understanding: Speech processing efficiency and vocabulary growth across the second year. Developmental Psychology, 42, 98–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Pinto JP, Swingley D, Weinberg A, & McRoberts GW (1998). Rapid gains in speed of verbal processing by infants in the second year. Psychological Science, 9, 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, & Weisleder A (2011). Early language experience is vital to developing fluency in understanding. In Neuman S & Dickinson D (eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (vol. 3), pp. 3–19. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Zangl R, Portillo AL, & Marchman VA (2008). Looking while listening: Using eye movements to monitor spoken language comprehension by infants and young children. In Sekerina I, Fernández EM & Clahsen H (eds.), Developmental psycholinguistics: On-line methods in children’s language processing, pp. 97–135. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Flege JE, MacKay IRA, & Piske T (2002). Assessing bilingual dominance. Applied Psycholinguistics, 23, 567–598. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole VCM, & Thomas EM (2009). Bilingual first-language development: Dominant language takeover, threatened minority language take-up. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 12, 213–237. [Google Scholar]

- Genesee F (1989). Early bilingual development: One language or two? Journal of Child Language, 16, 161–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson TA, Oller DK, Jarmulowicz L, & Ethington CA (2012). The receptive–expressive gap in the vocabulary of second-language learners: Robustness and possible mechanisms. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15, 102–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodz N (1989). Parental language mixing in bilingual families. Infant Mental Health Journal, 10, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Guiberson M, Rodríguez BL, & Dale PS (2011). Classification accuracy of brief parent report measures of language development in Spanish-speaking toddlers. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in School, 42, 536–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen VF, & Kreiter J (2003). Understanding child bilingual acquisition using parent and teacher reports. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, & Risley TR (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, & Risley TR (1999). The social world of children: Learning to talk. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E (2003). The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Development, 74, 1368–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E (2006). How social contexts support and shape language development. Developmental Review, 26, 55–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E, Core C, Place S, Rumiche R, Señor M, & Parra M (2012). Dual language exposure and early bilingual development. Journal of Child Language, 39, 1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB (1975). Four factor index of social status. Ms., Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado N, Marchman VA, & Fernald A (2007). Spoken word recognition by Latino children learning Spanish as their first language. Journal of Child Language, 33, 27–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado N, Marchman VA, & Fernald A (2008). Does input influence uptake? Links between maternal talk, processing speed and vocabulary size in Spanish-learning children. Developmental Science, 11, F31–F39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher J, Haight W, Bryk A, Seltzer M, & Lyons T (1991). Vocabulary growth: Relation to language input and gender. Developmental Psychology, 27, 236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson-Maldonado D, Thal DJ, Marchman VA, Newton T, Fenson L, & Conboy B (2003). MacArthur Inventarios del Desarrollo de Habilidades Comunicativas: User’s guide and technical manual. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács AM, & Mehler J (2009). Flexible learning of multiple speech structures in bilingual infants. Science, 325 (5940), 611–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchman VA, & Fernald A (2008). Speed of word recognition and vocabulary knowledge in infancy predict cognitive and language outcomes in later childhood. Developmental Science, 11, F9–F16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchman VA, Fernald A, & Hurtado N (2010). How vocabulary size in two languages relates to efficiency in spoken word recognition by young Spanish–English bilinguals. Journal of Child Language, 37, 817–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchman VA, Fernald A, & Hurtado N (2013). Early spoken language understanding predicts language and cognitive outcomes in Spanish-speaking toddlers. Ms., Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Marchman VA, & Martínez-Sussmann C (2002). Concurrent validity of caregiver/parent report measures of language for children who are learning both English and Spanish. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 45, 993–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchman VA, Martínez-Sussmann C, & Dale PS (2004). The language-specific nature of grammatical development: Evidence from bilingual language learners. Developmental Science, 7, 212–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCardle P, & Hoff E (eds.) (2006). Childhood bilingualism: Research on infancy through school age. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Oller DK, & Eilers RE (eds.) (2002). Language and literacy in bilingual children. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis J, & Genesee F (1996). Syntactic acquisition in bilingual children: Autonomous or interdependent? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis J, Genesee F, & Crago MB (2011). Dual language development and disorders: A handbook on bilingualism and second language learning (2nd edn.) Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson J, & Pearson BZ (2004). Bilingual lexical development: Influences, contexts and processes. In Goldstein BA (ed.), Bilingual language development and disorders in Spanish–English speakers, pp. 77–104. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson BZ, Fernández SC, Lewedeg V, & Oller DK (1997). The relation of input factors to lexical learning by bilingual infants. Applied Psycholinguistics, 18, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Place S, & Hoff E (2011). Properties of dual language exposure that influence 2-year-olds’ bilingual proficiency. Child Development, 82, 1834–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo MA (1998). Identifiers of predominantly Spanish-speaking children with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41, 1398–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez ET, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Spellmann ME, Pan BA, Raikes H, Lugo-Gil J, & Luze G (2009). The formative role of home literacy experiences across the first three years of life in children from low-income families. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30, 677–694. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe ML (2008). Child-directed speech: Relation to socioeconomic status, knowledge of child development, and child vocabulary skill. Journal of Child Language, 35, 185–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Yoshikawa H, Kahana-Kalman R, & Wu I (2011). Language experiences and vocabulary development in Dominican and Mexican infants across the first 2 years. Developmental Psychology, 48, 1106–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, & Mervis C (1994). The instrument is great, but measuring comprehension is still a problem. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 174–179. [Google Scholar]

- Weisleder A, & Fernald A (in press). Talking to children matters: Early language experience strengthens processing and builds vocabulary. Psychological Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werker JF, & Byers-Heinlein K (2008). Bilingualism in infancy: First steps in perception and comprehension. Trends in Cognitive Science, 12, 144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]