Abstract

Long-lived proteins (LLPs) are prone to deterioration with time and one prominent breakdown process is scission of peptide bonds. These cleavages can either be enzymatic or spontaneous. In this study, human lens proteins were examined and many were found to have been cleaved on the C-terminal side of Glu and Gln residues. Such cleavages could be reproduced experimentally by in vitro incubation of Glu- or Gln-containing peptides at physiological pHs. Spontaneous cleavage was dependent on pH and amino acid sequence. These model peptide studies suggested that the mechanism involves a cyclic intermediate and is therefore analogous to that characterised for cleavage of peptide bonds adjacent to Asp and Asn residues. An increased amount of some Glu/Gln cleaved peptides in the insoluble fraction of human lenses suggests that cleavage may act to destabilise proteins. Spontaneous cleavage at Glu and Gln, as well as recently described crosslinking at these residues, can therefore be added to the similar processes affecting long-lived proteins that have already been documented for Asn and Asp residues.

Keywords: Protein Cleavage, Human lens, Huntington’s disease, Long-lived proteins, Age

Introduction

Throughout the body, cells that are life-long or long-lived are more common than previously thought [1–3]. From brain to testis, many cells have been discovered to have a long lifespan.[4] Within these cells, a number of LLPs have been found [5]. The lifetimes of these proteins lead to an array of modifications; both enzymatic and spontaneous. Post-translation modifications (PTMs) such as oxidation [6], glycation [7], acylation [8], citrullination [9], deamidation [10], isomerisation [11], racemisation [12, 13] and others have been reported in aged tissues [14]. Some enzymatic modifications have been well-established however mechanisms of spontaneous deterioration are currently not well understood. In the human lens, such processes are likely to be responsible for the formation of cataract and this has been reviewed recently [15, 16].

The lens is an ideal tissue to investigate spontaneous processes that occur to LLPs because the center, or nucleus, of the adult human lens does not contain active enzymes [17, 18]. This is due to the unique growth pattern of the lens [19] whereby during fiber cell maturation organelles are degraded resulting in central lens proteins that are as old as the organism.[20] Current knowledge suggests that five spontaneous processes are prevalent in LLPs during aging: racemisation [13], isomerisation [11, 12], deamidation [10], crosslinking [21–23] and peptide bond cleavage [24]. Under normal physiological conditions, most peptide bonds are stable [25], however spontaneous scission of some peptide bonds, such as those adjacent to Asn, Asp, Ser, Thr, Cys residues have been reported [24, 26, 27]. In some cases, other factors, such as transition metals, can influence these spontaneous cleavage reactions. For example, zinc can catalyse cleavage of peptide bonds on the N-terminal side of Ser and Thr residues [24].

Cleavage of peptide bonds next to Asp has been known to peptide chemists for many years [28]. The mechanism of Asp cleavage appears to involve attack of the ionized carboxyl side chain on the protonated carbonyl group of the peptide bond [29]. In the case of Asn cleavage, the side chain nitrogen atom attacks the carbonyl of the adjacent peptide bond [30]. Such reactions lead to cleavage of lens proteins next to Asp and Asn residues in lens proteins [30, 31]

As part of an ongoing project to determine the main spontaneous processes that occur to LLPs, proteomic techniques were employed to analyse protein modifications in adult human lenses. In this paper, evidence was found for the scission of peptide bonds on the C-terminal side of Gln and Glu residues. Further, the mechanism of spontaneous cleavage was investigated by the use of model peptides.

Results and Discussion

Identification of Gln and Glu cleavage sites in human lenses

Previously it has been reported that LLPs are susceptible to spontaneous cleavage at Asp and Asn residues and that this is mediated via a 5-membered cyclic intermediate [30, 31]. In a similar manner, both Gln and Glu can undergo an intramolecular reaction forming a six-membered cyclic intermediate. To investigate whether this process could cause protein cleavage in biological tissues, we investigated tryptic peptides from human lens proteins for evidence of non-tryptic polypeptide cleavage at Gln and Glu residues. A diverse set of proteins including cytosolic, cytoskeletal and membrane proteins were found to display evidence of cleavage at Gln (Table 1) and Glu (Table 2).

Table 1:

Sites of cleavage at Gln

| Gene Name | Peptide | Cleavage Site | [MH]+Exp | [MH]+Cal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRYAA | 79–90: HFSPEDLTVKVQ | Q90 | 1399.7216 | 1399.7212 |

| CRYAA | 89–104: VQDDFVEIHGKHNERQ | Q104 | 1951.9255 | 1951.9257 |

| CRYAA | 120–126: LPSNVDQ | Q126 | 773.3674 | 773.3676 |

| CRYAB | 93–108: VLGDVIEVHGKHEERQ | Q108 | 1844.9613 | 1844.9613 |

| HSPG2 | 486–501: GMVFGIPDGVLELVPQ | Q501 | 1670.8816 | 1670.8822 |

| CRYBA1 | 197–206: EWGSHAQTSQ | Q206 | 1130.4863 | 1130.4861 |

| CRYBA1 | 197–208: EWGSHAQTSQIQ | Q208 | 1371.6288 | 1371.6287 |

| CRYBA4 | 49–63: VLSGAWVGFEHAGFQ | Q63 | 1604.7854 | 1604.7856 |

| CRYBA4 | 178–189: EWGSHAPTFQVQ | Q189 | 1386.6437 | 1386.6437 |

| CRYBB1 | 61–70: LVVFELENFQ | Q70 | 1237.6480 | 1237.6463 |

| CRYBB1 | 93–106: SIIVSAGPWVAFEQ | Q106 | 1503.7843 | 1503.7842 |

| CRYBB1 | 136–147: LMSFRPIKMDAQ | Q147 | 1436.7382 | 1436.7390 |

| CRYBB1 | 151–167: ISLFEGANFKGNTIEIQ | Q167 | 1882.9435 | 1882.9433 |

| CRYBB1 | 215–223: HWNEWGAFQ | Q223 | 1175.4905 | 1175.4905 |

| CRYBB1 | 215–225: HWNEWGAFQPQ | Q225 | 1399.6178 | 1399.6178 |

| CRYBB1 | 215–227: HWNEWGAFQPQMQ | Q227 | 1674.7118 | 1674.7118 |

| CRYBB2 | 49–55: AGSVLVQ | Q55 | 673.3879 | 673.3879 |

| CRYBB2 | 172–185: DSSDFGAPHPQVQ | Q185 | 1384.6125 | 1384.6128 |

| CRYBB2 | 190–197: IRDMQWHQ | Q197 | 1113.5258 | 1113.5258 |

| BASP1 | 98–106: AEPPKAPEQ | Q106 | 966.4891 | 966.4891 |

| BASP1 | 98–108: AEPPKAPEQEQ | Q108 | 1223.5901 | 1223.5902 |

| BASP1 | 150–160: KTEAPAAPAAQ | Q160 | 1054.5528 | 1054.5527 |

| BFSP1 | 223–238: SQLEEGREVLSHLQAQ | Q238 | 1823.9251 | 1823.9246 |

| BFSP1 | 320–334: LTSAFIETPIPLFTQ | Q334 | 1677.9099 | 1677.9098 |

| ALDOA | 260–275: TVPPAVTGITFLSGGQ | Q275 | 1544.8314 | 1544.8319 |

| CRYGC | 60–67: RGEYPDYQ | Q67 | 1027.4480 | 1027.4479 |

| CRYGC | 60–68: RGEYPDYQQ | Q68 | 1155.5062 | 1155.5065 |

| CRYGC | 143–149: QYLLRPQ | Q149 | 917.5202 | 917.5203 |

| CRYGD | 60–67: RGDYADHQ | Q67 | 961.4121 | 961.4122 |

| CRYGS | 85–93: AVHLPSGGQ | Q93 | 865.4529 | 865.4526 |

| CRYGS | 132–149: VLEGVWIFYELPNYRGRQ | Q149 | 2240.1481 | 2240.1503 |

| CRYGS | 159–171: KPIDWGAASPAVQ | Q171 | 1339.7005 | 1339.7005 |

| GJA3 | 108–114: EREEEEQ | Q114 | 948.3907 | 948.3905 |

| GJA8 | 110–116: EAEELGQ | Q116 | 775.3468 | 775.3468 |

| GJA8 | 110–117: EAEELGQQ | Q117 | 903.4054 | 903.4054 |

| MIP | 239–248: GAKPDVSNGQ | Q248 | 973.4585 | 973.4585 |

| MIP | 239–261: GAKPDVSNGQPEVTGEPVELNTQ | Q261 | 2368.1150 | 2368.1151 |

| BFSP2 | 77–86: ALGISSVFLQ | Q86 | 1034.5882 | 1034.5881 |

Bold and underlined N represents deamidated Asn, Bold and underlined M represents oxidized Met. [MH]+Exp reports measured masses after recalibration by MaxQuant.

Table 2:

Sites of cleavage at Glu

| Gene Name | Peptide | Cleavage Site | [MH]+Exp | [MH]+Cal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRYAA | 22–33: LFDQFFGEGLFE | E33 | 1448.6733 | 1448.6733 |

| CRYAA | 71–83: FVIFLDVKHFSPE | E83 | 1577.8361 | 1577.8362 |

| CRYAA | 146–156: IQTGLDATHAE | E156 | 1155.5641 | 1155.5640 |

| CRYAA | 158–164: AIPVSRE | E164 | 771.4359 | 771.4359 |

| CRYAA | 158–165: AIPVSREE | E165 | 900.4785 | 900.4785 |

| CRYAB | 23–30: LFDQFFGE | E30 | 1002.4565 | 1002.4567 |

| CRYAB | 23–34: LFDQFFGEHLLE | E34 | 1494.7264 | 1494.7264 |

| CRYAB | 93–106: VLGDVIEVHGKHEE | E106 | 1560.8083 | 1560.8016 |

| CRYAB | 150–156: KQVSGPE | E156 | 744.3887 | 744.3886 |

| CRYAB | 158–164: TIPITRE | E164 | 829.4778 | 829.4778 |

| CRYAB | 158–165: TIPITREE | E165 | 958.5204 | 958.5204 |

| CRYBA1 | 96–108: WDAWSGSNAYHIE | E108 | 1536.6388 | 1536.6390 |

| CRYBA4 | 26–32: RHEFTAE | E32 | 889.4163 | 889.4163 |

| CRYBB1 | 61–67: LVVFELE | E67 | 848.4765 | 848.4764 |

| CRYBB1 | 73–79: RAEFSGE | E79 | 795.3631 | 795.3632 |

| CRYBB1 | 93–105: SIIVSAGPWVAFE | E105 | 1375.7262 | 1375.7263 |

| CRYBB1 | 232–240: LRDKQWHLE | E240 | 1224.6484 | 1224.6484 |

| CRYBB1 | 236–249: QWHLEGSFPVLATE | E249 | 1613.7958 | 1613.7958 |

| CRYBB2 | 161–167: GLQYLLE | E167 | 835.4559 | 835.4560 |

| BPGM | 63–82: SIHTAWLILEELGQEWVPVE | E82 | 2349.2125 | 2349.2125 |

| BASP1 | 26–33: AEGAATEE | E33 | 777.3267 | 777.3261 |

| BASP1 | 26–34: AEGAATEEE | E34 | 906.3687 | 906.3687 |

| BASP1 | 26–39: AEGAATEEEGTPKE | E39 | 1418.6281 | 1418.6281 |

| BASP1 | 39–53: ESEPQAAAEPAEAKE | E53 | 1556.7078 | 1556.7075 |

| BASP1 | 98–105: AEPPKAPE | E105 | 838.4296 | 838.4305 |

| BASP1 | 98–107: AEPPKAPEQE | E107 | 1095.5316 | 1095.5317 |

| BASP1 | 122–131: AAEAAAAPAE | E131 | 871.4155 | 871.4156 |

| BASP1 | 150–161: KTEAPAAPAAQE | E161 | 1183.5949 | 1183.5953 |

| DBN1 | 187–194: EEELRKEE | E194 | 1061.5110 | 1061.5110 |

| DBN1 | 187–195: EEELRKEEE | E195 | 1190.5535 | 1190.5535 |

| BFSP1 | 312–326: IIEIEGNRLTSAFIE | E326 | 1704.9167 | 1704.9167 |

| BFSP1 | 454–463: SPKEPETPTE | E463 | 1114.5264 | 1114.5263 |

| CRYGS | 37–43: CNSIKVE | E43 | 849.4130 | 849.4135 |

| GJA3 | 110–118: EEEEQLKRE | E118 | 1189.5695 | 1189.5695 |

| GJA8 | 234–241: SALKRPVE | E241 | 899.5309 | 899.5309 |

| GJA8 | 238–249: RPVEQPLGEIPE | E249 | 1363.7215 | 1363.7216 |

| GJA8 | 274–283: IVSHYFPLTE | E283 | 1205.6200 | 1205.6201 |

| GJA8 | 274–288: IVSHYFPLTEVGMVE | E288 | 1720.8613 | 1720.8615 |

| PYGB | 725–731: KGYNARE | E731 | 837.4220 | 837.4213 |

| LCTL | 451–464: GYTSWSLLDKFEWE | E464 | 1760.8176 | 1760.8166 |

| MIP | 239–250: GAKPDVSNGQPE | E250 | 1199.5539 | 1199.5539 |

| MIP | 239–254: GAKPDVSNGQPEVTGE | E254 | 1585.7340 | 1585.7340 |

| MIP | 239–257: GAKPDVSNGQPEVTGEPVE | E257 | 1910.8978 | 1910.8980 |

| NDUFA13 | 69–78: IALLPLLQAE | E78 | 1080.6664 | 1080.6663 |

| BFSP2 | 90–102: SSGLATVPAPGLE | E102 | 1198.6306 | 1198.6314 |

| BFSP2 | 90–109: SSGLATVPAPGLERDHGAVE | E109 | 1962.9881 | 1962.9879 |

| BFSP2 | 282–289: DVEKNRVE | E289 | 989.4897 | 989.4898 |

| BFSP2 | 401–413: DVASYHALLDREE | E413 | 1517.7230 | 1517.7231 |

| EPB41 | 451–460: IRPGEQEQYE | E460 | 1248.5855 | 1248.5855 |

| SPTAN1 | 64–70: LQIASDE | E70 | 775.3832 | 775.3832 |

| WFS1 | 27–34: LNATASLE | E34 | 819.4098 | 819.4094 |

Bold and underlined N represents deamidated Asn. [MH]+Exp reports measured masses after recalibration by MaxQuant.

Quantification Glu and Gln truncation

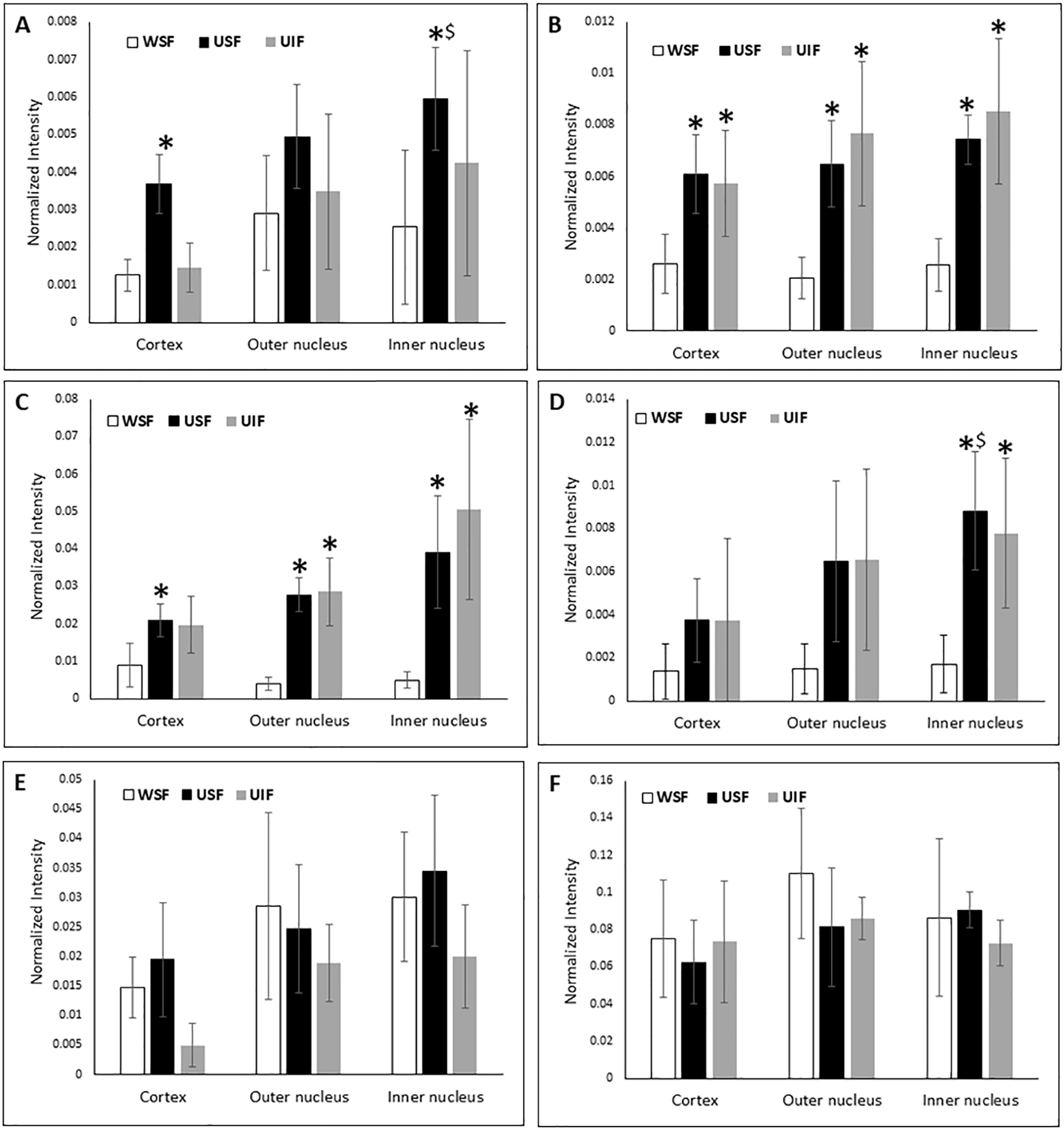

Based on MaxQuant search results and overall peptide intensities, six truncation sites were selected for quantification studies. These six sites include E165 and E156 in αA-crystallin, Q208 in βA3-crystallin, Q189 in βA4-crystallin, E249 in βB1-crystallin and Q197 in βB2-crystallin. Manual verification was performed for these truncated peptides based on accurate mass, retention time, isotopic distribution and tandem mass spectra. Once verified as bona fide truncation products, peak intensities were obtained using the Xcalibur ICIS peak integration algorithm. Peak areas of the truncated peptides were normalized by peak areas of the corresponding tryptic peptide. The levels of truncation were compared between different solubility fractions and lens regions. The results can be found in Figure 1. Since the tryptic peptides used for normalization have different ionization efficiencies, the y-axis in Figure 1 simply provides a measure of the relative degree of truncation.

Figure 1: Relative quantification of truncation at Gln and Glu in middle-aged normal human lenses.

Relative truncation of αA E165 (A), αA E156 (B), βA3 Q208 (C), βA4 Q189 (D), βB1 E249 (E) and βB2 Q197 (F) in different regions of middle-aged normal human lenses. * indicates a statistically significant difference in truncation compared with WSF of the same regions of the lens (p < 0.05). $ indicates a statistically significant difference in truncation compared with cortex region of the lens. The error bars indicate standard deviation of four biological replicates (WSF = Water soluble fraction, USF = Urea soluble fraction and UIF=Urea insoluble fraction.)

Relative truncation at E165 and E156 of αA, Q208 of βA3, and Q189 of βA4 increased in the USF or UIF compared to WSF, indicating truncation at these sites may induce protein insolubilisation. Increased truncation at αA E156, βA3 Q208 in USF and UIF samples was detected in all three regions of the lens (cortex, outer nucleus and inner nucleus). Truncation levels in USF and UIF were also compared and no statistically significant difference was detected for these six truncation sites. Increased truncation in USF was not detected for all crystallin truncation sites. Truncation at E249 of βB1 and Q197 of βB2 in WSF and USF or UIF did not show a significant difference in any lens region.

The above truncation sites at Gln or Glu residues are close to the C-terminus of each protein. Significant levels of truncation can be detected in the cortex region. Only truncation at αA E165 and βA4 Q189 increased significantly in the inner nucleus region in USF compared with cortex region.

Common sites of cleavage

From Tables 1 & 2 it is apparent that cleavage on the C-terminal side of Gln and Glu residues is common, with 38 sites found cleaved next to Gln and 51 next to Glu. To understand the mechanism for the cleavage, model studies were undertaken using synthetic peptides. Two sets of peptides Ac-FAEXA and Ac-FAQXA were examined, where X corresponds to a Pro, Ala or Asp residue. These three amino acid residues were represented at protein cleavage sites for both Glu and Gln (see Supp Fig 3). The α-amino group was blocked by acetylation to avoid unwanted reactions during long incubation times. While fragments arising next to C-terminal Ser residues were common sites from the lens protein data, this residue was excluded from the peptide study since scission of the peptide bond N-terminal to a Ser can occur via other spontaneous mechanisms independent of Glu or Gln [37].

Cleavage at Glu residues

C-terminal Proline residue

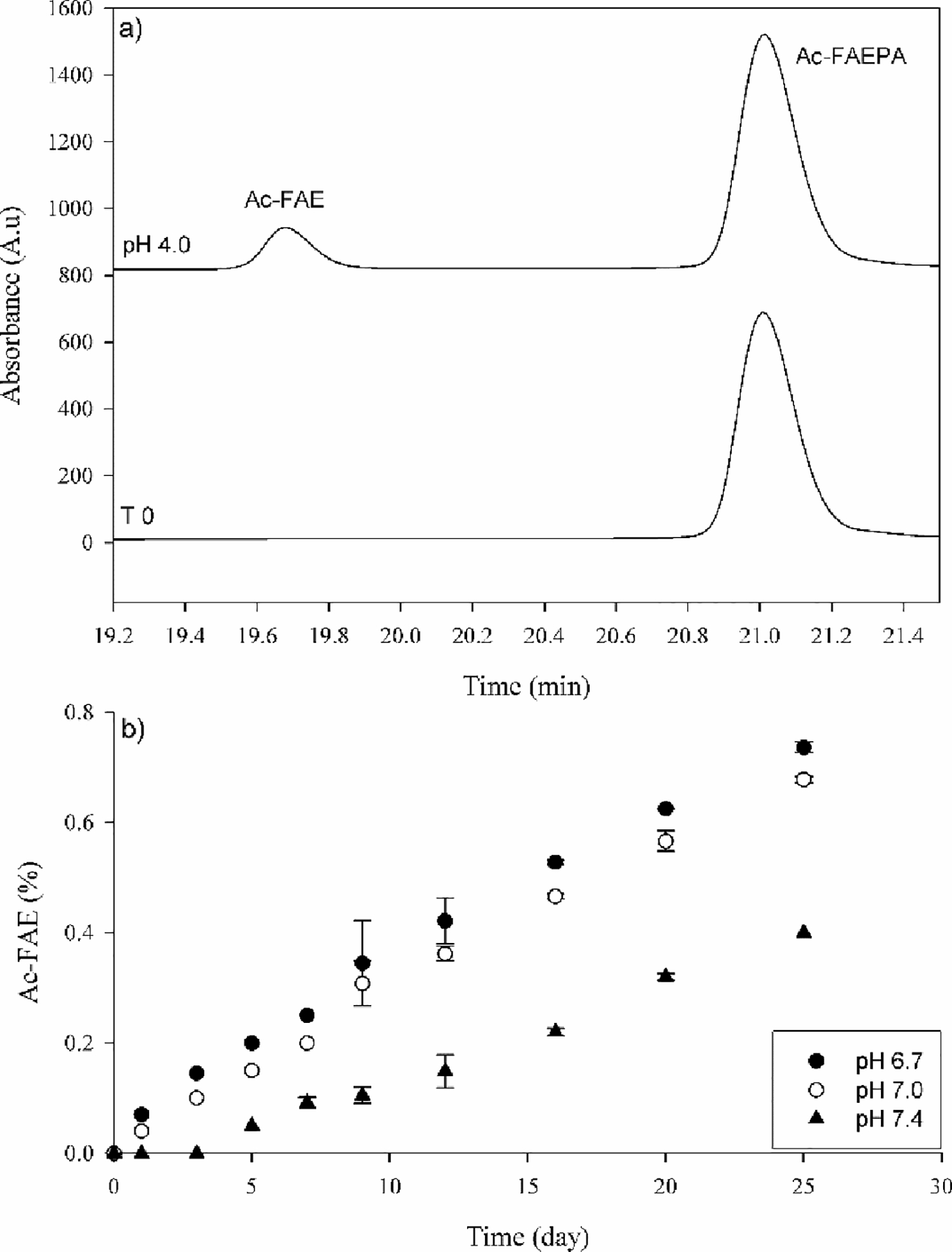

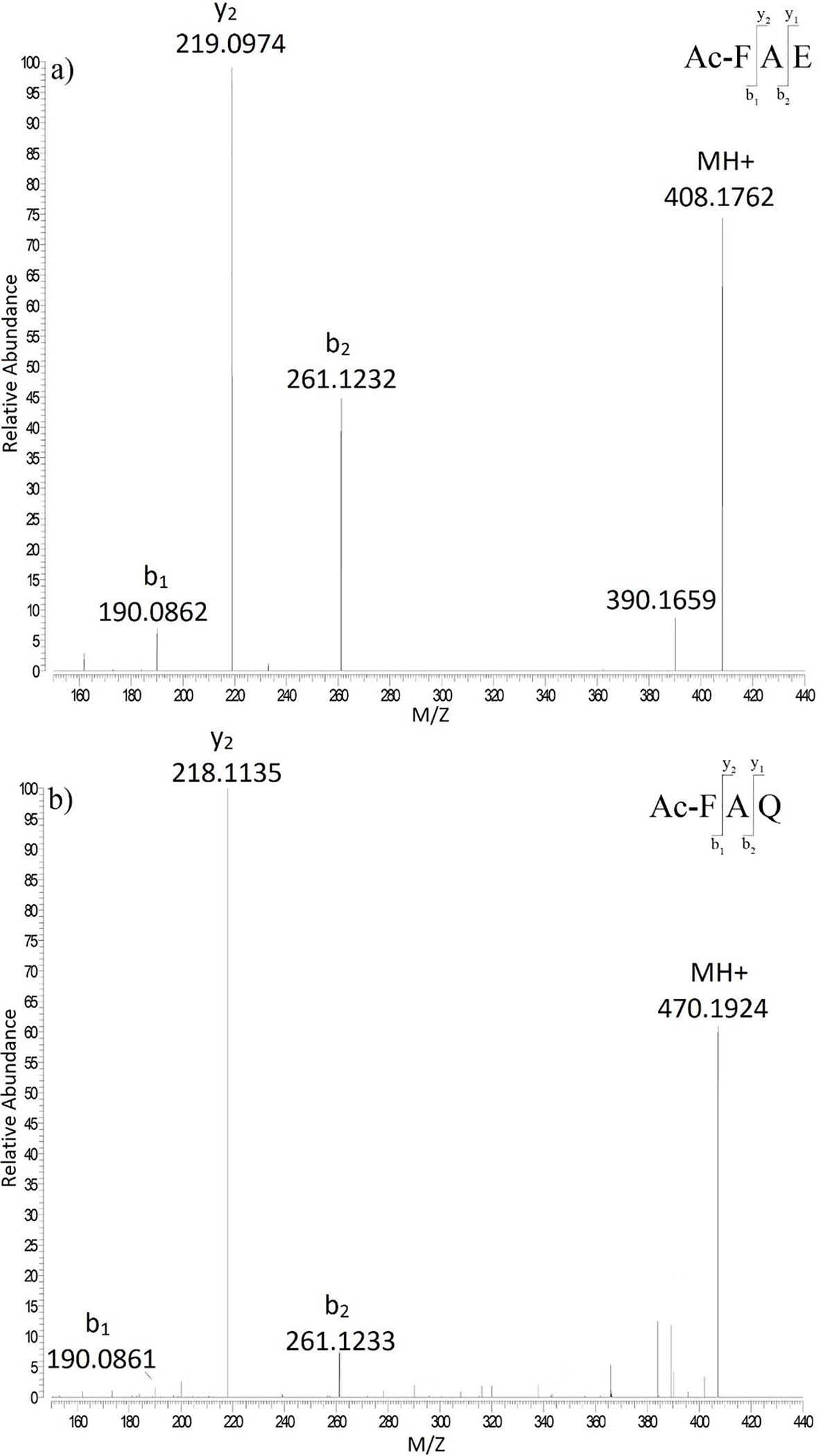

To determine if spontaneous cleavage could be detected using model peptides, Ac-FAEPA was incubated in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.0 and the breakdown of Ac-FAEPA monitored by HPLC (Figure 2). After several days of incubation at 60°C, a peak eluting at 19.7 min was formed. Upon isolation and subsequent analysis by mass spectrometry, it was found to contain Ac-FAE (Figure 3). The identity of this C-terminal Glu cleavage product was confirmed by co-elution and the MS/MS spectrum of synthetic Ac-FAE. While not visible in the HPLC trace, the dipeptide PA was also detected in the void volume and its identity was confirmed by mass spectrometry. After 25 days ~13% of the original Ac-FAEPA peptide had been cleaved.

Figure 2. Cleavage on the C-terminal side of Glu in Ac-FAEPA.

a) HPLC profile of Ac-FAEPA at time zero (bottom) and after incubation for 25 days at 60°C, pH 4.0 (Top). The identification of Ac-FAE was confirmed by mass spectrometry. b) Time course of Ac-FAE formation at pH 6.7, 7.0 and 7.4. Ac-FAE was calculated as a percentage of total HPLC peak area. All samples were run in triplicate. Error bars +/− SD.

Figure 3. MS/MS spectrum of Ac-FAE and Ac-FAQ isolated from the Ac-FAEPA and Ac-FAQPA incubation.

a) Ac-FAE b) Ac-FAQ following incubation at pH 6.7.

The effect of pH on peptide bond scission was then examined using buffers more typical of physiological pHs, i.e. pH 6.7, 7.0 and 7.4 (Figures 2 and 4). Overall, the apparent rate of cleavage decreased considerably as buffer pH was increased. The rates were similar at pH 7.0 and at the pH of the centre of the lens (pH 6.7), however, the rate was significantly lower at pH 7.4. By comparison with pH 4.0, it was estimated that cleavage was approximately 18-fold slower at pH 6.7.

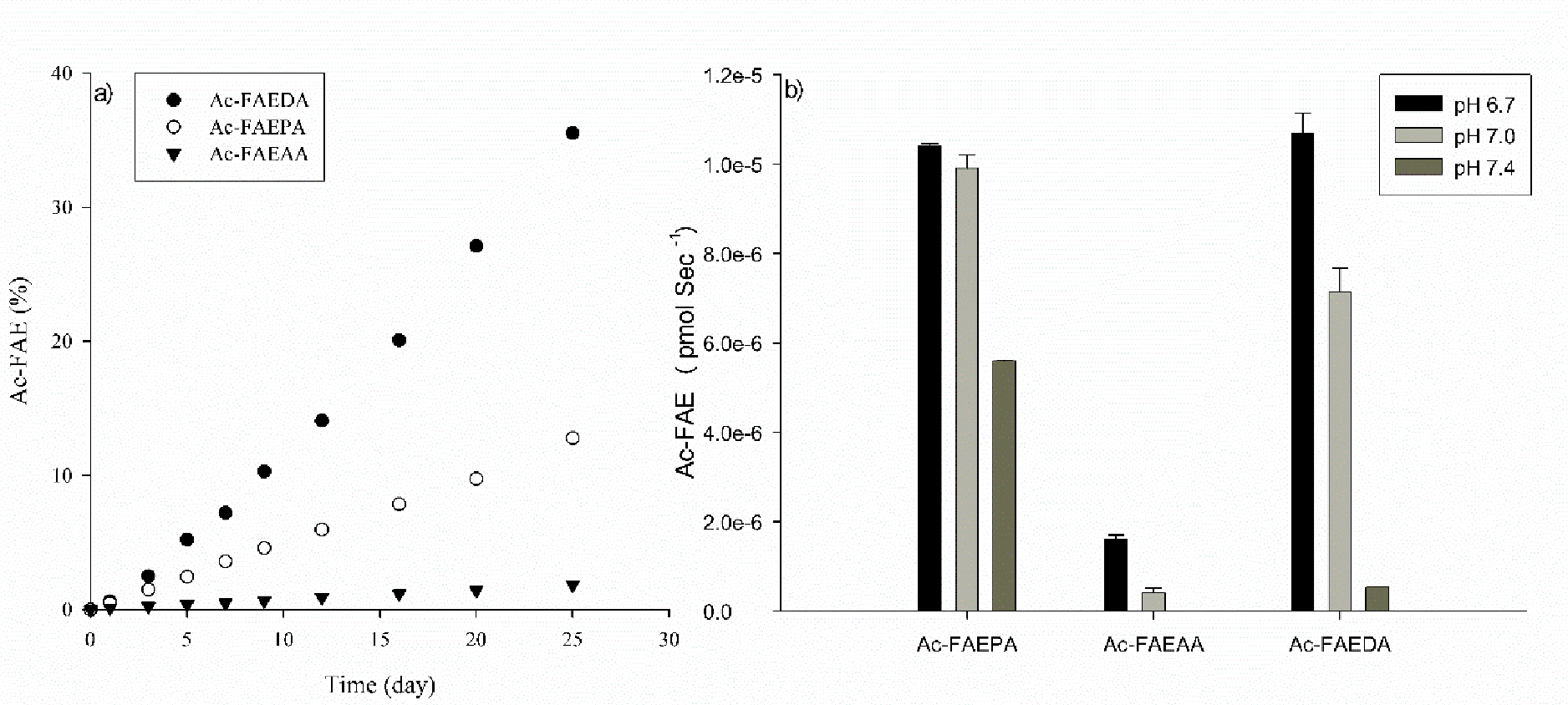

Figure 4. Cleavage on the C-terminal side of Glu in Ac-FAEDA, Ac-FAEPA and Ac-FAEAA.

a) Time course of Ac-FAE from the three peptides at pH 4.0. Ac-FAE formation was calculated as a percentage of total HPLC peak area b) Apparent rate of Glu cleavage in Ac-FAEDA Ac-FAEPA and Ac-FAEAA incubated at pH 6.7, 7.0 and 7.4. Cleavage rate was determined by the slope of the curve over a 25 day incubation period. All samples were run in triplicate at 60°C. Error bars +/− SD.

The above experiments were repeated at 37°C. While not visible by HPLC, Ac-FAE was detectable by mass spectrometry in the pH 4.0 and 6.7 incubations after 40 days. No evidence of Ac-FAE was found in the pH 7.0 and 7.4 incubations.

C-terminal Aspartate residue

Using the same incubation conditions as Ac-FAEPA, the HPLC profile of Ac-FAEDA after 25 days incubation at pH 4.0 was more complex than that of Ac-FAEPA. This is presumably due to the presence of an Asp residue in the sequence, since spontaneous cleavage next to Asp has been documented [31] and L-Asp residues can also convert to D-Asp as well as to D- isoAsp and L- isoAsp via a succinimide (Asu) intermediate [38].

Two early eluting HPLC peaks were found to be cleavage products of Ac-FAEDA. A peak eluting at 77 min was confirmed by mass spectrometry to be Ac-FAE. A second peak at 79 min was identified by MS/MS as the Asp cleavage product Ac-FAED, which is consistent with previous studies showing cleavage at Asp [31]. Cleavage at both Glu and Asp decreased as buffer pH was increased, and at pH 7.4 little cleavage was observed (Figure 4). A peak at approximately 86 min was shown by mass spectrometry to have the same mass as Ac-FAEDA and is likely due to the formation of Ac-FAE(isoAsp)A. Detection of a component corresponding in mass and MS/MS to Ac-FAE(Asu)A at 98 min supported this assignment.

Similar to the previous incubation of Ac-FAEPA, when Ac-FAEDA was incubated at 37°C for 40 days, Ac-FAE was detected by mass spectrometry in both the pH 4.0 and 6.7 samples.

C-terminal Alanine residue

In contrast to Ac-FAEPA and Ac-FAEDA, Ac-FAEAA showed considerably less spontaneous cleavage next to Glu (Figure 4). At pH 4.0, little cleavage was observed in the case of Ac-FAEAA and this decreased at higher pHs, with none detected at pH 7.4.

Cleavage at Gln residues

The above experiments were repeated using the homologous Gln peptides.

C-terminal Proline residue

Unlike the case of Ac-FAEPA, where the formation of Ac-FAE was readily observed, Ac-FAQPA displayed little breakdown even after 25 days incubation at pH 4.0 (Figure 5a). A small peak was observed by HPLC following 25 days of incubation and was confirmed by mass spectrometry and the use of synthetic standards to be Ac-FAQ (Figure 3b). No Ac-FAQ was detected in incubations at pH 6.7, 7.0 and 7.4 after 25 days.

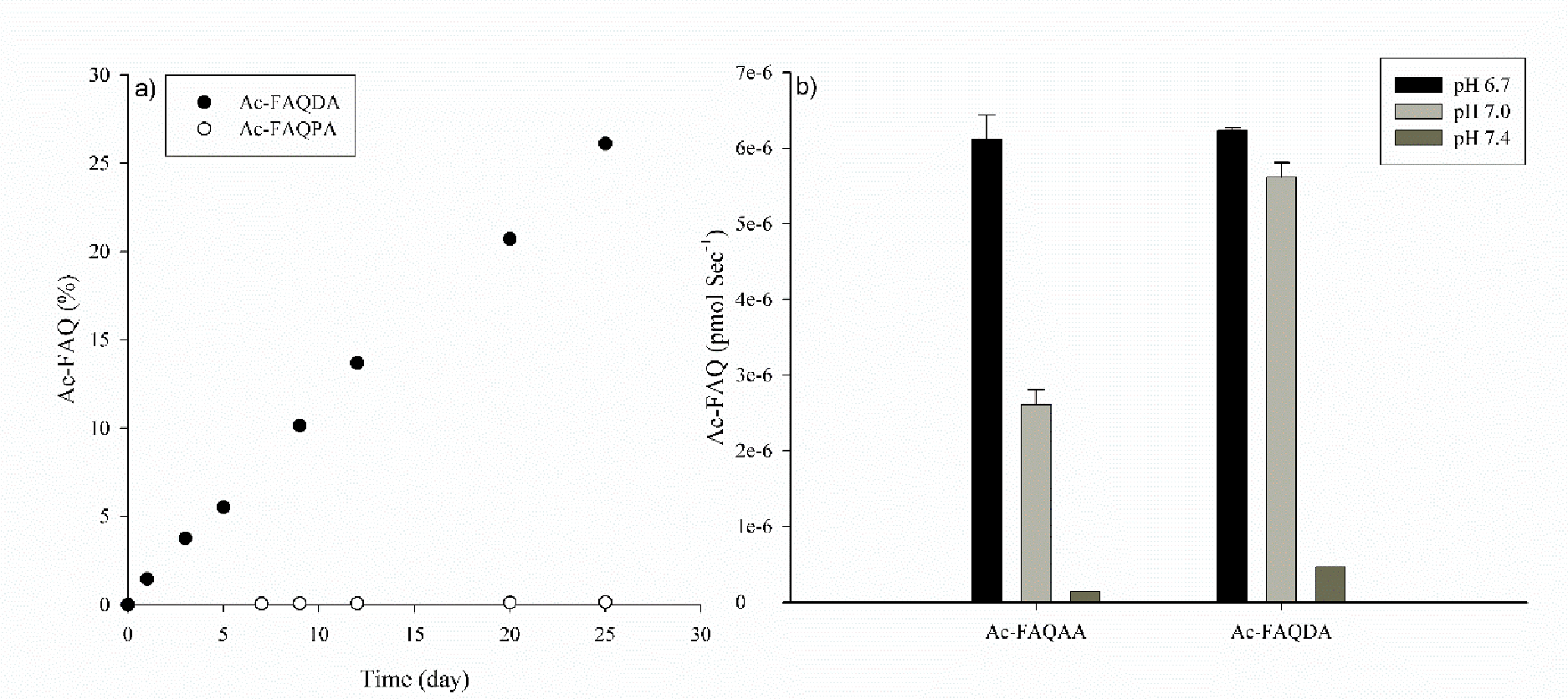

Figure 5. Cleavage on the C-terminal side of Gln in Ac-FAQDA, Ac-FAQPA and Ac-FAQAA.

a) Time course of formation of Ac-FAQ from Ac-FAQDA and Ac-FAQPA following incubation at pH 4.0, 60°C. No cleavage of Ac-FAQAA was observed at pH 4.0. b) Apparent rate of formation of Ac-FAQ from Ac-FAQDA and Ac-FAQAA incubated at pH 6.7, 7.0 and 7.4. No cleavage of Ac-FAQPA was observed at these pHs. Cleavage rate was determined by the slope of the line over 25 days at 60°C. All samples were run in triplicate. Error bars +/− SD.

C-terminal Aspartate residue

By contrast to Ac-FAQPA, the HPLC traces of Ac-FAQDA incubations displayed multiple breakdown products. At pH 4.0, the two major products generated were Ac-FAQ and Ac-FAQD and there was no evidence of deamidation of Gln occurring or the generation of Ac-FAE (Supplemental Figure 2). Each product was identified by mass spectrometry.

At pH 6.7, Ac-FAQ was detected in low amounts, together with the major breakdown products resulting from isomerisation and cleavage at Asp i.e. the formation of Ac-FAQ(isoAsp)A and Ac-FAQD. As the pH of incubation increased from 7.0 to 7.4, the amount of Ac-FAQ formed decreased (Figure 5b).

C-terminal Alanine residue

For Ac-FAQAA, cleavage was very pH dependent (Figure 5). At pH 4.0 no cleavage was observed, however as the pH rose to 6.7, Ac-FAQ was detected but the rate of formation decreased thereafter as pH increased to 7 and 7.4. By comparison with Ac-FAEAA, cleavage of Ac-FAQAA occurred 3-fold and 2.5-fold faster at pH 6.7 and 7.0 respectively.

N-terminal Cleavage at Glu

In addition to Ac-FAE production from the Glu peptide incubations described above, other peptide samples displayed evidence of N-terminal cleavage that was detectable via mass spectrometry. In samples of Ac-FAEPA and Ac-FAEDA that had been incubated at pH 4.0 and 6.7, EPA and EDA were found. In addition, the N-terminal fragment, Ac-FA, was also detected, although these cleavage products were present only in trace amounts. No similar cleavages were observed in the case of the Gln containing peptides.

Discussion

This study has shown that Glu and Gln residues can act as sites for spontaneous cleavage in LLPs. Further, truncation at Glu or Gln was more pronounced in some crystallins in the insoluble protein fractions (figure. 1) suggesting that truncation at Glu or Gln could induce protein insolubilization. In this paper, a mechanism by which the side chains of these residues can function to cleave adjacent peptide bonds is proposed.

In general, cleavage observed at Glu and Gln was dependent on pH and was slower than that observed at Asp/Asn. At approximately neutral pH, cleavage at Glu was comparable to Gln, however Glu cleavage displayed a marked decline in going from the pH in the lens center (pH 6.7) to pH of blood (pH 7.4). At acidic pH, cleavage occurred more readily at Glu. To illustrate this point, at the pH of lysozomes (pH 4.0) no spontaneous cleavage next to Gln was detected in Ac-FAQAA in comparison to Ac-FAEAA. Cleavage was also dependent on the nature of the amino acid C-terminal to the Glu or Gln as illustrated in Supp Fig 3

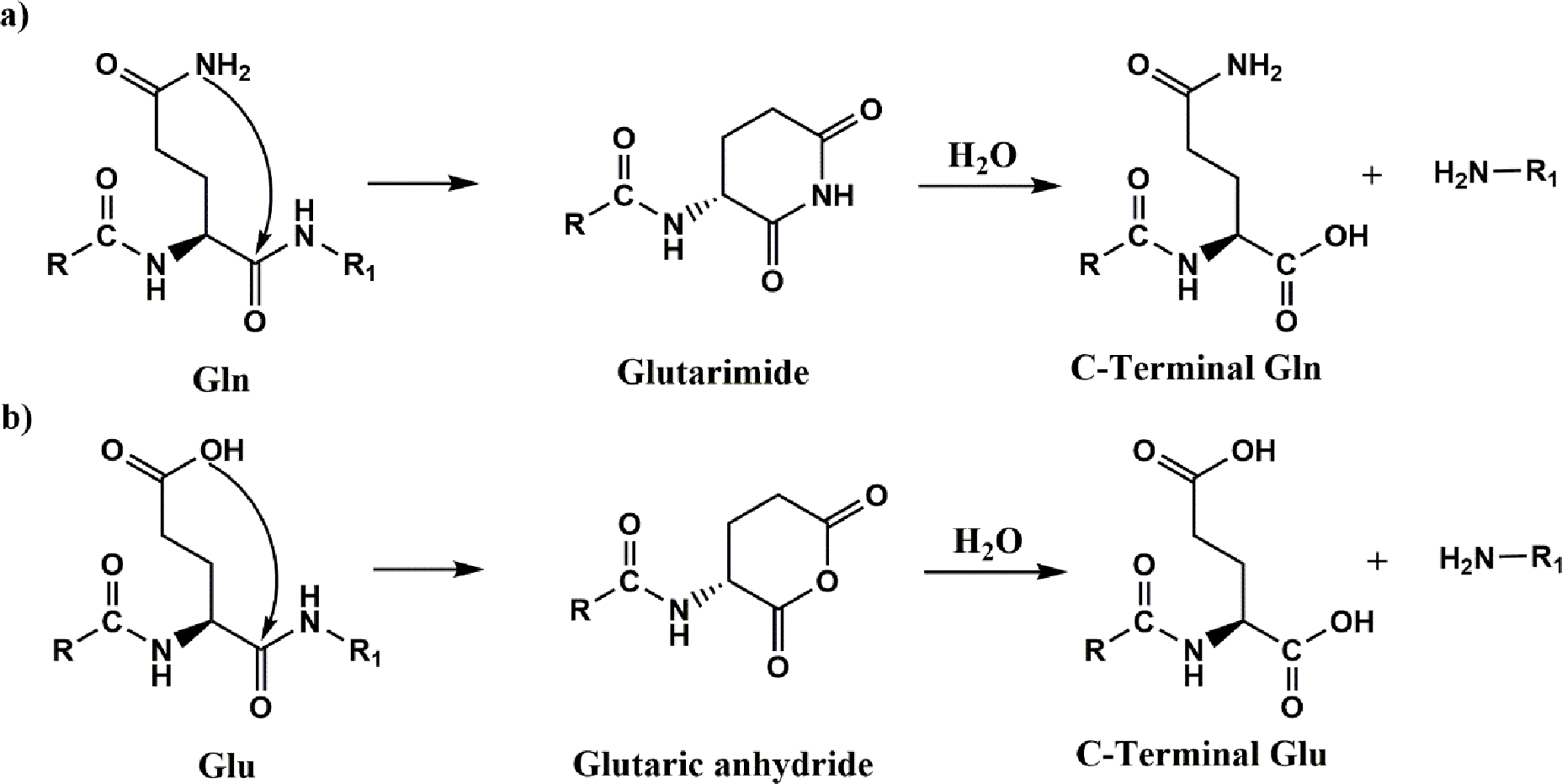

Data from human lenses revealed numerous sites of peptide bond scission at Gln and Glu resides and these cleavages were predominantly localised on the C-terminal side of these amino acids. Such reactions could be replicated using peptides, demonstrating that the reactions can occur spontaneously. Although not investigated in detail, the mechanism seems to involve the formation of a cyclic intermediate, as found with the homologous Asp and Asn residues [30, 31]. In the case of Gln and Glu residues, cyclisation results in either the formation of a C-terminal glutarimide (GSU) or a glutaric anhydride respectively. Hydrolysis of these intermediates leads to scission of the peptide bond.

It is hypothesised that cleavage at Gln residues occurs when the peptide backbone carbonyl group is attacked by the nitrogen atom of the side chain amide (Figure 6). The formation of a GSU ring has been shown to be important in the deamidation of glutamine residues [39]. In addition, identification of isoGlu residues confirmed the involvement of GSU in studies of glutamine deamidation [40]. Hydrolysis of the resulting cyclic GSU yields a C-terminal Gln residue. Similarly, with Glu residues, the side chain carboxyl oxygen atom attacks the peptide backbone carbonyl group resulting in the formation of a cyclic anhydride. It was apparent from the model studies, that the rates of peptide bond scission at Gln/Glu residues are significantly lower than those found with Asp and Asn. This was clearly seen in the peptides that contained Asp as well as Glu/Gln, such as Ac-FAEDA and Ac-FAQDA, where cleavage at Asp was more prominent than that at Glu or Gln.

Figure 6. Proposed mechanism of spontaneous cleavage at Gln and Glu in polypeptides.

a) The side chain nitrogen atom of Gln attacks the peptide carbonyl on the C-terminal side of Gln. A glutarimide is formed which is accompanied by cleavage of the peptide bond leading ultimately, after hydrolysis, to the formation of a C-terminal Gln. b) The side chain oxygen atom of Glu attacks the peptide carbonyl on the C-terminal side of Gln. A glutaric anhydride is formed accompanied by cleavage of the peptide bond ultimately leading to the formation of a C-terminal Glu residue.

In addition to C-terminal cleavage at Glu residues, cleavage was detected N-terminally to Glu in model peptides. This was not observed in peptides containing Gln, nor was it observed in tryptic peptides from the human lens samples. Interestingly cleavage N-terminal to Glu can be facilitated by bromination of the Glu side chain, encouraging the formation of a five -membered ring [41].

In previous studies it was found that long-lived lens proteins are cleaved and that the amount of hydrolysis increases with age [42]. In these endogenous peptides, some residues such as Ser occur more commonly on the N-termini and this was explained by a spontaneous process of peptide bond hydrolysis in lens crystallins. In the case of Ser, cleavage of the N-terminal peptide bond was facilitated by zinc [24]. When these same data were examined for the frequency of Glu and Gln termini, Gln residues occurred more frequently on the C-terminal side, however this was not the case for Glu. Recently we discovered that Glu and Gln can act as sites of covalent crosslinking [43]. In these cases, sites of crosslinking within intermediate filament proteins such as phakinin and filensin were relatively more abundant than in crystallins, for reasons that are at present unknown. While not examined in this study, if cleavage at Gln or Glu occurred via a cyclic glutarimide or glutaric anhydride a potential crosslink could form analogous to what has been observed at Asn and Asp [30, 31]. Evidence of a C-terminal Glu crosslink occurring in peptide models has been previously reported [43].

In this study only lens proteins were examined. Proteins within other tissues may also show evidence of spontaneous cleavage at Glu or Gln, such as polypeptides containing large polyQ tracts. For example, known polyglutamine disorders (Huntingtons disease [44], spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy [44], dentatorubro-pallidolysian atrophy [44], spinocerebellar ataxias [44],) are characterised by expanded polyQ sequences within their respective disease-causing proteins. Little is known about cleavages within these polyQ regions and this will be investigated in the next phase of this research.

In conclusion, this study has revealed that cleavage next to Gln and Glu occurs in a diverse set of proteins in the human lens. Recently we discovered that Glu and Gln residues can also act as sites of novel covalent crosslinking [43]. There are therefore parallels between the Asp/Asn pair and the homologous Glu/Gln amino acids, in terms of their propensity to act as sites for spontaneous crosslinking, as well as sites of cleavage, in long-lived proteins.

Methods:

Lens protein extraction

Frozen human lenses were obtained from NDRI (Philadelphia, PA). All lenses were isolated from donors no later than 8 hours post mortem and shipped on dry ice. Human lens work was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All lenses received were stored at −80°C until use. Four normal human lenses were used (48 yr, 56 yr and two 53 yr).

Lenses were individually dissected into three regions: cortex, outer nucleus and inner nucleus. As the lens grows continuously throughout life with no turnover of protein, the centre of the lens corresponds to the oldest crystallins, the outer nucleus is of intermediate age and the cortex contains the youngest crystallins [32].

Samples corresponding to different regions of the lenses and different solubilities were prepared as described previously [33]. Briefly, human lenses were equatorially sectioned to a thickness of 30 μm in a cryostat (LEICA CM 3050S, Leica Microsystems Inc., Bannockburn, IL) and sections were collected on pieces of parafilm. Three different regions of the lens were separated by sequentially punching the sections using AcuPunch trephines (Acuderm Inc, Ft. Lauderdale, FL) with diameters of 4.5 mm, 6 mm to generate the inner nucleus and the outer nucleus regions. The rest of the tissue was collected as the cortex. Lens sections on parafilm rings were prepared by five sequential washes with 100 μL of 25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4. The samples were passed through a 25G needle five times and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was collected as the water soluble fraction (WSF). The pellets were vortexed in 100 μL of 8 M urea in 25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4 and centrifuged at 20,000g for 30 min. This 8M urea extraction was repeated and both urea extracts were pooled as the urea soluble fraction (USF). The remaining pellets were collected as the urea insoluble fraction (UIF). The protein concentration in each fraction was measured by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Samples were reduced and alkylated as described previously [33]. WSF and USF proteins were precipitated by chloroform/methanol as previously described [34]. All samples were digested by trypsin in 50mM Tris containing 10% acetonitrile, pH 8.0 with an enzyme-to-protein ratio of 1:100. The digestion was done overnight at 37°C. After digestion, all samples were dried in a speedvac and peptides in each sample were reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid for further analysis.

LC-MS/MS

For LC-MS/MS analysis, tryptic peptides were separated on a one-dimensional fused silica capillary column (250 mm × 100 μm) packed with Phenomenex Jupiter resin (3 μm, 300 Å pore size) coupled with an Easy-nLC system (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA ). A 70-minute gradient was performed, consisting of the following: 0–60 min, 2–45% ACN (0.1% formic acid); 60–70 min, 45–95% ACN (0.1% formic acid) balanced with 0.1% formic acid. The eluate was directly infused into a Q Exactive instrument (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ionization source. The data-dependent instrument method consisted of MS1 acquisition (R=70,000), using an MS AGC target value of 1e6, followed by up to 15 MS/MS scans (R=17,500) of the most abundant ions detected in the preceding MS scan. The MS2 AGC target value was set to 2e5, with a maximum ion time of 200 ms, and a 5% underfill ratio, and an intensity threshold of 5e4. HCD collision energy was set to 27, dynamic exclusion was set to 5 s, and peptide match and isotope exclusion were enabled.

Incubation of Glu and Gln peptides

Peptides Ac-FAEDA, Ac-FAEPA, Ac-FAEAA, Ac-FAQDA, Ac-FAQPA and Ac-FAQAA (1 mg/mL) were incubated at either 37 °C or 60 °C in 50mM MOPS buffer at pH 6.7, 7.0 and 7.4 or 50mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 4.0. Aliquots were collected at various time intervals and were injected onto an Agilent 1100 HPLC using an Aeris RP-HPLC column (2.6 μ, XB-C18, 100 × 2.1 mm, Phenomenex). Breakdown products of peptides Ac-FAQDA and Ac-FAEDA were eluted with the following gradient 2% ACN, 0.1% TFA 0–40 min, 5% ACN, 0.1% TFA 40–60 mins, 10% ACN, 0.1%TFA 60–80 min, 15% ACN, 0.1% TFA 80–100min, 25% ACN, 0.1% TFA 100–120 min, 80 % ACN, 0.1%TFA, 135 min 2% ACN, 0.1%TFA 145min. All other peptides used the following elution gradient: 2% ACN, 0.1% TFA 5 min, 20% ACN, 0.1% TFA 15 mins, 40% ACN, 0.1%TFA 20 min, 25 min 80%ACN, 0.1% TFA, 35 min 80% ACN, 0.1% TFA, 30.1 min 2% ACN, 0.1%TFA, 40 min 2% ACN, 0.1%TFA.

Breakdown of all peptides was monitored at 216nm and 280nm. Peaks were collected and identified by tandem mass spectrometry on an LTQ Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid with a nanoelectrospray ionisation source (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA). Data were manually acquired with HCD collision energy set to 15.

Data analysis

For identifying sites of truncation, the raw data were loaded into MaxQuant software (http://maxquant.org/, version 1.6.6.0) [35] and searched against a custom human lens database [36]. The search was performed with semi-tryptic specificity with a maximum of 2 missed cleavage sites. Methionine oxidation, asparagine deamidation and protein N-terminal acetylation were variable modifications (up to 2 modifications allowed per peptide); cysteine was assigned a fixed carbamidomethyl modification. Precursor mass tolerance was set at 5 ppm. A false discovery rate (FDR) of 1% was applied for both peptide and protein filtering. To quantify the levels of truncation, selected ion chromatograms were generated for truncated peptides and peak areas were calculated within Xcalibur software 4.0.27.19 (ThermoFisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). The peak areas of the truncated peptides were normalized by the peak intensities of corresponding tryptic peptides. The peak areas of the tryptic peptides were obtained from MaxQuant search result. Statistical analysis was performed by Student’s t-test and results were considered as statistically significant when p<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge the use of the UOW Mass Spectrometry User Resource and Research Facility (MSURRF), University of Wollongong and the Proteomics Core Facility of the Vanderbilt University Mass Spectrometry Research Center.

Footnotes

Funding sources and disclosure of conflicts of interest Funding for this study was provided by National Institutes of Health by grants R01 EY024258 and P30 EY008126. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fornasiero EF, et al. , Precisely measured protein lifetimes in the mouse brain reveal differences across tissues and subcellular fractions. Nature Communications, 2018. 9(1): p. 4230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toyama BH, et al. , Visualization of long-lived proteins reveals age mosaicism within nuclei of postmitotic cells. J Cell Biol, 2019. 218(2): p. 433–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Truscott RJW, Schey KL, and Friedrich MG, Old Proteins in Man: A Field in its Infancy. Trends in biochemical sciences, 2016. 41(8): p. 654–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truscott RJW, Long-Lived Cells and Long-Lived Proteins in the Human Body, in Long-lived Proteins in Human Aging and Disease. 2021. p. 5–42. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toyama BH and Hetzer MW, Protein homeostasis: live long, won’t prosper. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2013. 14(1): p. 55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorisse L, et al. , Protein carbamylation is a hallmark of aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2016. 113(5): p. 1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sivan SS, et al. , Age-related accumulation of pentosidine in aggrecan and collagen from normal and degenerate human intervertebral discs. The Biochemical journal, 2006. 399(1): p. 29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu J-Y, et al. , Protein acetylation and aging. Aging, 2011. 3(10): p. 911–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JK, et al. , Multiple sclerosis: an important role for post-translational modifications of myelin basic protein in pathogenesis. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2003. 2(7): p. 453–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hains PG and Truscott RJW, Age-Dependent Deamidation of Lifelong Proteins in the Human Lens. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 2010. 51(6): p. 3107–3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooi MYS, Raftery MJ, and Truscott RJW, Racemization of Two Proteins over Our Lifespan: Deamidation of Asparagine 76 in γS Crystallin Is Greater in Cataract than in Normal Lenses across the Age RangeRacemization and Cataract Formation. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 2012. 53(7): p. 3554–3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedrich MG, et al. , Isoaspartic acid is present at specific sites in myelin basic protein from multiple sclerosis patients: could this represent a trigger for disease onset? Acta Neuropathologica Communications, 2016. 4(1): p. 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooi M and Truscott R, Racemisation and human cataract. d-Ser, d-Asp/Asn and d-Thr are higher in the lifelong proteins of cataract lenses than in age-matched normal lenses. AGE, 2011. 33(2): p. 131–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldensperger T, et al. , Comprehensive analysis of posttranslational protein modifications in aging of subcellular compartments. Scientific Reports, 2020. 10(1): p. 7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schey KL, et al. , Spatiotemporal changes in the human lens proteome: Critical insights into long-lived proteins. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 2019: p. 100802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truscott RJW and Friedrich MG, Molecular Processes Implicated in Human Age-Related Nuclear Cataract. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 2019. 60(15): p. 5007–5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu X, Korlimbinis A, and Truscott RJ, Age-dependent denaturation of enzymes in the human lens: a paradigm for organismic aging? Rejuvenation Res, 2010. 13(5): p. 553–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dovrat A, Scharf J, and Gershon D, Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in rat and human lenses and the fate of enzyme molecules in the aging lens. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 1984. 28(2): p. 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Augusteyn RC, On the growth and internal structure of the human lens. Experimental eye research, 2010. 90(6): p. 643–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynnerup N, et al. , Radiocarbon Dating of the Human Eye Lens Crystallines Reveal Proteins without Carbon Turnover throughout Life. PLoS ONE, 2008. 3(1): p. e1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linetsky M, et al. , Dehydroalanine crosslinks in human lens. Exp Eye Res, 2004. 79(4): p. 499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, et al. , Human protein aging: modification and crosslinking through dehydroalanine and dehydrobutyrine intermediates. Aging Cell, 2014. 13(2): p. 226–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedrich MG, et al. , Spontaneous cross-linking of proteins at aspartate and asparagine residues is mediated via a succinimide intermediate. Biochem J, 2018. 475(20): p. 3189–3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyons B, Kwan AH, and Truscott RJ, Spontaneous cleavage of proteins at serine and threonine is facilitated by zinc. Aging Cell, 2016. 15(2): p. 237–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radzicka A and Wolfenden R, Rates of Uncatalyzed Peptide Bond Hydrolysis in Neutral Solution and the Transition State Affinities of Proteases. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1996. 118(26): p. 6105–6109. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voorter CE, et al. , Spontaneous peptide bond cleavage in aging alpha-crystallin through a succinimide intermediate. J Biol Chem, 1988. 263(35): p. 19020–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadeh T and Patchornik A, Nonenzymatic Cleavages of Peptide Chains at the Cysteine and Serine Residues through Their Conversion to Dehydroalanine (DHAL). II. The Specific Chemical Cleavage of Cysteinyl Peptides. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1964. 86(6): p. 1212–1217. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inglis AS, Cleavage at aspartic acid. Methods Enzymol, 1983. 91: p. 324–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joshi AB, et al. , Studies on the Mechanism of Aspartic Acid Cleavage and Glutamine Deamidation in the Acidic Degradation of Glucagon. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2005. 94(9): p. 1912–1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedrich MG, et al. , Mechanism of protein cleavage at asparagine leading to protein–protein cross-links. Biochemical Journal, 2019. 476(24): p. 3817–3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z, et al. , Cleavage C-terminal to Asp leads to covalent crosslinking of long-lived human proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics, 2019. 1867(9): p. 831–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koretz JF, Cook CA, and Kuszak JR, The zones of discontinuity in the human lens: development and distribution with age. Vision Res, 1994. 34(22): p. 2955–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Z and Schey KL, Quantification of thioether-linked glutathione modifications in human lens proteins. Exp Eye Res, 2018. 175: p. 83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wessel D and Flügge UI, A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Analytical Biochemistry, 1984. 138(1): p. 141–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox J, et al. , Accurate proteome-wide label-free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2014. 13(9): p. 2513–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z, et al. , Proteomics and phosphoproteomics analysis of human lens fiber cell membranes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2013. 54(2): p. 1135–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyons B, Kwan AH, and Truscott RJW, Spontaneous cleavage of proteins at serine and threonine is facilitated by zinc. Aging cell, 2016. 15(2): p. 237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geiger T and Clarke S, Deamidation, isomerization, and racemization at asparaginyl and aspartyl residues in peptides. Succinimide-linked reactions that contribute to protein degradation. J Biol Chem, 1987. 262(2): p. 785–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Capasso S, et al. , First evidence of spontaneous deamidation of glutamine residue via cyclic imide to α- and γ-glutamic residue under physiological conditions. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications, 1991(23): p. 1667–1668. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riggs DL, et al. , Analysis of Glutamine Deamidation: Products, Pathways, and Kinetics. Analytical Chemistry, 2019. 91(20): p. 13032–13038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nalbone JM, et al. , Glutamic Acid Selective Chemical Cleavage of Peptide Bonds. Organic Letters, 2016. 18(5): p. 1186–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korlimbinis A, et al. , Protein aging: Truncation of aquaporin 0 in human lens regions is a continuous age-dependent process. Experimental Eye Research, 2009. 88(5): p. 966–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friedrich MG, et al. , Spontaneous protein–protein crosslinking at glutamine and glutamic acid residues in long-lived proteins. Biochemical Journal, 2021. 478(2): p. 327–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lieberman AP, Shakkottai VG, and Albin RL, Polyglutamine Repeats in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease, 2019. 14(1): p. 1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.