Abstract

HIV-1 genetic diversity and resistance profile might change according to the risky sexual behavior of the host. To show this, we recruited 134 individuals between the years 2015 and 2017 identified as transgender women sex workers (TWSW, n = 73) and Heterosexual Military Officers (HET-MO, n = 61). After obtaining informed consent, we collected a blood sample to perform the HIV genotyping, CD4 cell count, and viral load. We used bioinformatics approaches for detecting resistance mutations and recombination events. Epidemiological data showed that both groups reported sexually transmitted diseases and they were widespread among TWSW, especially syphilis and herpes virus (35.6%). Illegal drugs consumption was higher among TWSW (71.2%), whereas condom use was inconsistent for both HET-MO (57.4%) and TWSW (74.0%). TWSW showed the shortest time exposition to antiretroviral therapy (ART) (3.5 years) and the lowest access to ART (34.2%) that conducted treatment failure (>4 logs). HIV-1 sequences from TWSW and HET-MO were analyzed to determine the genetic diversity and antiretroviral drug resistance. Phylogeny analysis revealed 125 (93%) cases of subtype B, 01 subtype A (0.76%), 07 (5.30%) BF recombinants, and 01 (0.76%) AG recombinant. Also, TWSW showed a higher recombination index (9.5%, 7/73) than HET-MO (1.5%, 1/68). HET-MO only showed acquired resistance (26.23%, 16/61), whereas TWSW showed both acquired as transmitted resistance (9.59% for each). In conclusion, TWSW and HET-MO showed significant differences considering the epidemiological characteristics, genetic diversity, recombination events, and HIV resistance profile.

Keywords: HIV, virus evolution/diversity, antiretroviral therapies, molecular biology

Introduction

With close to 37.7 million people living with HIV-1 worldwide,1 the World Health Organization considers HIV-1 an infectious pandemic of global proportions. In Peru, the infection cases are more than 137,000 up to February 2021, with 98.39% of the infections being transmitted sexually. Nowadays, it is calculated that the rate of HIV-1 in Peru is about 1.3 cases per 100,000 people.2 Similar to other countries in Latin America, the HIV-1/AIDS epidemic in Peru is concentrated among individuals who engage in high-risk sexual behavior, including men who have sex with other men (MSM) and sex workers.3

Even though HIV-1 prevalence in MSM has been reported to be high (12.5%)4 in Transgender Women (TW), this index is the highest, whose prevalence in Lima has been estimated near to 30%.5 The main factors that promote HIV-1 transmission are the high social stigma and discrimination that TW are involved in, where job opportunities are scarce, and sex work is the predominant activity.5 Of interest, Operario et al.6 showed that the HIV-1 infection status of transgender women sex workers (TWSW) is higher than those who do not exert commercial sex, suggesting that TWSW might keep the conditions to increase of HIV-1 infection cases. Therefore, if the risk sexual behavior promotes HIV-1 transmission among individuals, this infection dynamic might produce changes into the HIV-1 genetic repertory, promoting its molecular evolution.7

Previous studies have also shown that some HIV-1 subtypes were distributed differently in individuals depending on sexual behavior. Thus, HIV-1 subtype B was predominant in MSM compared with the heterosexual group (HET), where subtype F and recombinant B/F were more frequent.8 Vrancken et al.,7 using the evolutionary model, compared env, gag, and pol simultaneously and showed differences between MSM and HET. Another study revealed that the HIV-1 recombinant CRF01_E was predominant in a group of Thai MSM, including different epidemiological and clinic characteristics related to this genetic subtype.9 As it can be seen, there is evidence that shows that genetic variability of HIV-1 may be affected depending on the risk of sexual behavior.

In Peru, we have identified HIV-1 subtype B, which was 100% prevalent in MSM and HET.10 However, analysis of genetic diversity using the Pi parameter and intragenic recombination of env sequences showed that HIV-1 infecting MSM was more divergent than those infecting HET.11 Our hypothesis for this finding is that the high-risk sexual behavior of MSM compared with HET might have influenced this difference. However, these analyses did not include social and epidemiological data that might be very useful when analyzing molecular information. Therefore, this study compares the viral genetic polymorphism and antiretroviral (ARV) drug resistance in the context of sexual behavior differences between HIV-1 infected TWSW and HET represented by Military Officers (HET-MO) to assess whether sexual behavior differences are involved in HIV-1 molecular evolution.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This work is a prospective, descriptive, and transversal study carried out in Lima, Peru from 73 TWSW treated during 2015 and 2017 at the Specialized Center for Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) “Alberto Barton” and 61 HET-MO recruited from “Hospital Militar Central.” Participants were recruited by convenience through the duration of the study. All subjects accepted voluntarily to participate and signed the informed consent. As a benefit of this study, participants received counseling on their monitoring test results. We did not offer financial or treatment incentives. The selection criteria included participants as minimum age of 18 years old, with or without antiretroviral therapy (ART), with reactive Western Blot or LIA (Line Immunoassay) confirmation test for HIV-1/2. We did not exclude participants from this study.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB): “Comité Institucional de Ética en Investigación” of the Instituto Nacional de Salud de Perú (Research Project Code: OI-089-10). The ethical considerations under which that study was conducted included the option that participating subjects provide consent for their blood samples to be used in potential upcoming studies. Only subjects who accepted the inclusion of their samples for later studies were considered for the purpose of this investigation.

Isolation of genetic material

Total RNA was extracted from 140 μL of plasma and proviral DNA from 200 μL of whole blood according to the manufacturer's recommendations detailed in the handbook of QIAamp® viral RNA kit and QIAamp® DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Briefly, plasma samples were mixed with a lysis buffer containing an RNA carrier, and they were then passed through a spin column. The RNA retained was then washed and removed from the spin column by centrifugation (6,000 g) with elution buffer into sterile RNAse-free microcentrifuge tubes. For DNA extraction, whole blood was mixed with a lysis buffer containing proteinase K, then incubated at 56°C for 10 min, and passed through a spin column by centrifugation. After washing procedures, an elution buffer was used to remove the total DNA in a sterile DNAse-free microcentrifuge tube. RNA and DNA were stored at −80°C and −20°C, respectively, until use.

Reverse transcriptions and polymerase chain reaction

The HIV pol region (length about of 1,700 bp) was amplified by reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) following the Stanford Protocol12 with some modifications. Briefly, RT-PCR was performed in a microcentrifuge tube containing 1X Reaction Mix (0.2 mM of each dNTP and 1.6 mM MgSO4), 0.4 mM Magnesium Sulfate, 0.2 pmol of primers RT-21(-) (5′-CTG TAT TTC TGC TAT TAA GTC TTT TGA TGG G-3′)(positions 2028–2050 HXB-2) and 1243(-) (5′-ACT AAG GGA GGG GTA TTG ACA AAC TC-3′) (positions 3792–3817 HXB-2), 1 pmol of primer MAW-26(+) (5′-TTG GAA ATG TGG AAA GGA AGG AC-3′) (positions 2028–2050), 1 μL of SuperScript® III RT/Platinum® Taq Mix (Invitrogen), and 8.5 μL of RNA; then, it was incubated to 45°C for 30 min.

The enzyme was denatured at 94°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles to 94°C for 15 s, 55°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 2 min, a final extension of 72°C for 10 min, and finally a hold temperature of 16°C. After the run, the samples were maintained at 4°C. A second-round PCR was performed in a tube containing 1 × High Fidelity PCR Buffer Reaction Buffer II (60 mM Tris-SO4, pH 8.9; 18 mM Ammonium Sulfate), 1 mM MgCl2, 0.15 mM of dNTPs, 2 pmol of primer PRO-1(+)(5′-CAG AGC CAA CAG CCC CAC CA-3′)(positions 2147–2166), 1 pmol of primers RT-21(−) (5′-CTG TAT TTC TGC TAT TAA GTC TTT TGA TGG G-3′)(positions 2028–2050 HXB-2) and 1243 (−) (5′-ACT AAG GGA GGG GTA TTG ACA AAC TC-3′) (positions 3792–3817 HXB-2), 0.08 U of Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen), and 1 μL of reaction from the first round (50 μL of final volume).

Cycle conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 94°C for 1 min, followed for 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 63°C for 20 s, 72°C for 2 min, followed for 1 cycle to 72°C for 10 min and a hold temperature of 16°C. In the case of proviral DNA, all PCR conditions were similar except that the reverse transcription step was omitted. The two rounds of amplification were completed by using an Applied Biosystems Thermal Cycler model 9700. Next, the reaction products were separated through horizontal gel electrophoresis (1.5% agarose). After staining with ethidium bromide, the bands were visualized by illumination under ultraviolet light.

Purification of PCR products

PCR products were purified following the recommendations of the Qiaquick Purification Kit (Qiagen). We used a Molecular Weight Marker Low Mass Ladder (Invitrogen) to calculate product concentrations, which performs a visual quantitation comparing the fragment amplified with a reference DNA fragment.

Sequencing the PCR product

Ten nanograms of DNA was used for direct sequencing (BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit), which was mixed with 4 μL of Ready Reaction Premix containing Big Dye, 1X of BigDye Sequencing Buffer, and 0.5 pmol of primers MAW-46, DSPR, PSR-2, RT-a, RT-b, RT-y, HXB2–89, RT-z, B, Brev, HXB2–88, MAW-70; sequencing mix was performed as previously reported.12

Sequencing analysis

The quality of the sequences obtained was assessed by using Sequencing Analysis V2.0, and fragment assemblage was achieved by using SeqScape V3.1. Alternatively, Abi sequence format was submitted to Recall (beta v.3.05) to analyze the sequence quality and to export the FASTA sequences.

To characterize the genetic differences between TWSW and HET-MO populations, the pol nucleotide sequences were compared by using Maximum Composite Likelihood model (Mega v6), which elicits the rate variation among sites modeled with a gamma distribution (shape parameter = 1). Genetic subtypes were identified by using Maximum likelihood method based on the Tamura-Nei model applying 500 boostraping under a General Time-Reversible (GTR) nucleotide substitution model (suggested by ModelTest) with a gamma-distributed rate variation. Genetic clusters were recognized only for HIV-1 species grouped with a bootstrap value of for at least 70%. A set of 47 sequences was obtained from the REGA v3 database to use as reference sequences.

To find recombination events, FASTA sequences of the pol gene were submitted to COMET HIV-1-1 V2.2 to have a quick screen about of recombinant species in the HIV-1 samples. The results were confirmed by using the softwares REGA V3, jpHMM, and RIP v3 software.

All sequences that were identified as recombinant strains were compared with previous reported sequences of each BF (n = 66) and AG (n = 249) HIV strain by using Maximum likelihood method, which was implemented in IQ-TREE web server under the best-fit model GTR. The trees were created after 1,000 replicated bootstrap analysis. The Phylogenetic tree visualizations were possible by using Interactive Tree Of Life.

The ART resistance mutations were identified by submitting the FASTA genetic sequences to the Calibrate Population Resistance Tool (CPR) version 8. The Heatmapper (www.heatmapper.ca/) was designed based on the resistance mutation rate.

Statistical analysis

Epidemiological data were collected in a standardized questionnaire to build a database of participants. All information was stored in an Office Excel data sheet. Using this same program, we calculated averages, percentages, and standard deviations. Qualitative and quantitative variables analysis was performed by using Stata Software version 14. To determine statistical significance, the Student's t-test was used to calculate the media and Z-test. In addition, Linear Regression and multivariable analysis were also included.

Results

Epidemiological data

In this cohort, the population from TWSW were predominately younger (54.8% ranged 18 and 30-year-old), showing positive HIV-1 diagnoses earlier than HET-MO (Table 1). Of interest, TWSW had a higher STD frequency than HET-MO, predominantly syphilis/herpes virus infection (35.6%), and more frequent illegal drug consumption (71.2%). The access to ART was less frequent in TWSW, showing a higher viral load than HET-MO.

Table 1.

General Characteristics of the Study Population

| TWSW (n = 73) | HET-MO (n = 61) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (range in years) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | |

| 18–33 | 40 | 54.8 | 7 | 11.5 |

| 34–49 | 30 | 41.1 | 26 | 42.6 |

| 50–65 | 3 | 4.1 | 28 | 45.9 |

| Time of HIV-1 positive test (years media) | ||||

| 3.6 | 9.3 | |||

| Sexual contact with foreigners | ||||

| Yes | 7 | 9.6 | 10 | 16.4 |

| No | 63 | 86.3 | 50 | 82 |

| NDa | 3 | 4.1 | 1 | 1.6 |

| STD viral only associated | ||||

| Hepatitis only | 4 | 5.5 | 4 | 6.6 |

| Herpes only | 11 | 15.1 | 5 | 8.2 |

| STD bacterial only associated | ||||

| Syphilis only | 18 | 24.7 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Gonohrrea only | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 |

| STD viral and bacterial associated | ||||

| Syphilis/Herpes | 26 | 35.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Syphilis/HPV | 2 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatitis/Syphilis | 2 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Syphilis/Herpes. HPV | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatitis/Syphilis/Herpes | 2 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Syphilis/Herpes/HPV | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 |

| None STD | 7 | 9.6 | 0 | 0 |

| ND | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Condom use frequency | ||||

| Always | 54 | 74 | 35 | 57.4 |

| Sometimes | 18 | 24.7 | 10 | 16.4 |

| Never | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ND | 1 | 1.4 | 16 | 26.2 |

| Illegal drug user | ||||

| Yes | 52 | 71.2 | 1 | 1.6 |

| No | 20 | 27.4 | 58 | 95.1 |

| ND | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 3.3 |

| Risk sexual behavior | ||||

| Current sexual work | 73 | 100 | NAb | NA |

| Current sexual intercourse with TWSW or FSW | NA | NA | 2 | 3.3 |

| Access to ART | ||||

| Yes | 25 | 34.2 | 59 | 96.7 |

| No | 47 | 64.4 | 1 | 1.6 |

| ART decline | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 |

| ND | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 1.6 |

| ART initiation (range in years) | 3.5 (0–10) | 8.0 (1–26) | ||

| Virological and immunological status | ||||

| CD4 cell count (cells/μL) | 343 | 529 | ||

| Viral load (copies/mL) | 145,303 | 5,239 | ||

“Not determined,” which means that participants did not give any response to the question.

“No apply,” which means that the question was not formulated to the participant.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; FSW, female sex workers; HET-MO, Heterosexual Military Officers; HPV, human papilloma virus; NA, no apply; ND, not determined; STD, sexually transmitted diseases; TWSW, transgender women sex workers.

HIV-1 genetic diversity analysis reveals differences between TWSW and HET-MO

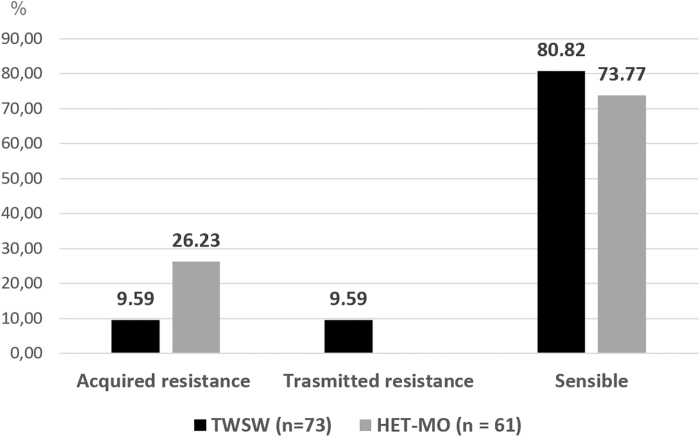

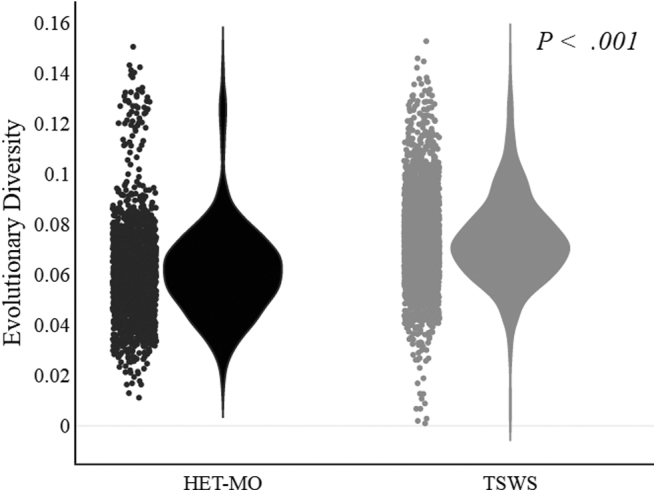

We analyzed the genetic divergences between HIV-1 species circulating among TWSW and HET-MO. The pairwise nucleotide comparison of HIV-1 among the TWSW and HET-MO population revealed significant genetic differences (p < .001, Fig. 1). The nucleotide divergence observed in pol gene among HIV-1 species was also studied through accumulative dS/dN index analysis. This analysis revealed that for both populations from codon positions 1 to 148 (complete protease region and part of reverse transcriptase), the non-synonymous mutations were higher than synonymous mutations. In contrast, from positions 149 to 344, the synonymous changes were higher, especially for TWSW (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Violin plots show the estimates of evolutionary divergence over sequence pairs within groups. Analyses were conducted using the Maximum Composite Likelihood model. The analysis involved 134 nucleotide sequences. All ambiguous positions were removed for each sequence pair. There were a total of 1,059 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted by using MEGA (v6) and visualization by Plotly's online graphing tool. Group comparison statistics was calculated by using Mann–Whitney U test (SPSS).

FIG. 2.

Cumulative dS/dN graph. Cumulative behavior (dS/dN) observed in PM and TST HIV-1-1 Pol sequences. A SNAP plot of the cumulative substitution behavior moving codon by codon across 351 codon positions (amino acid in Pol region corresponding to 56–406 relative to reference sequence HXB2). The software tool Highlighter was used to highlight silent (SYN) and non-silent (NONSYN) in the sequences alignments (n = 134) (https://www.HIV-1.lanl.gov/content/sequence/HIGHLIGHT/highlighter_top.html).

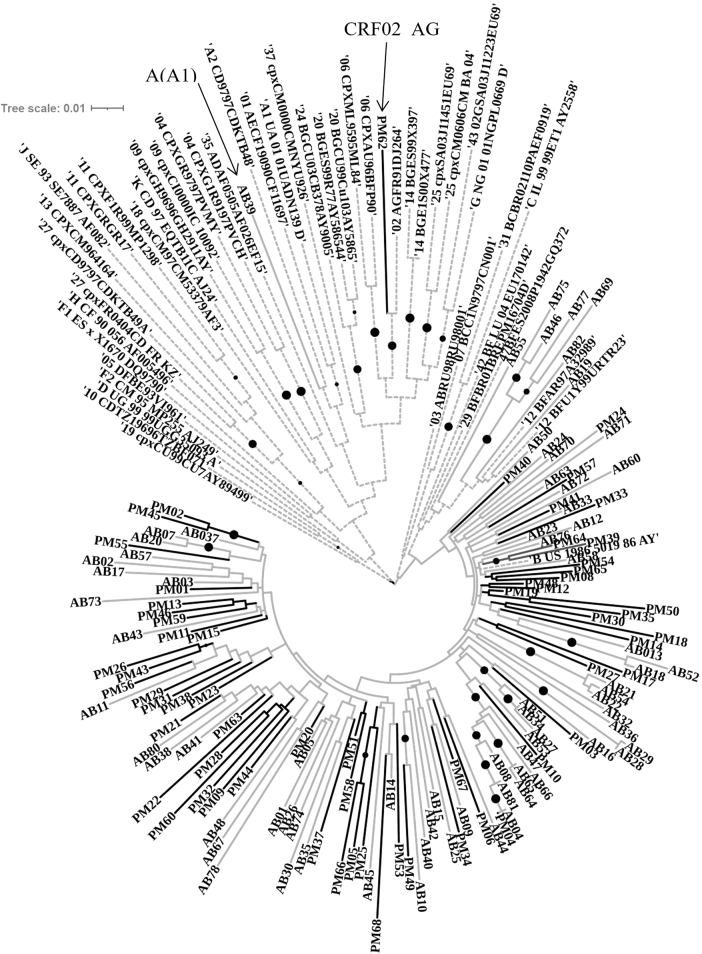

As shown in Figure 3, the analysis indicated that most of the HIV-1 forms are associated with subtypes B (n = 125, 93.3%). Nevertheless, our analysis also detected one case of the subtype A (AB39, group TWSW) and another case that clustered with a recombinant strain AG (PM62, group HET-MO).

FIG. 3.

The phylogenetic evaluation was inferred using the maximum likelihood method based on the GTR model implemented in MEGA v.6. The bootstrap consensus tree was inferred from 500 replicates. The tree involved 181 nucleotide sequences [references = 46, HET-MO (Lab code PM followed by a number) = 61, TSWS (Lab code AB followed by a number) = 73]. Populations groups are indicated as follows: reference strains = broken lines, HET-MO = Black lines, TSWS = gray lines, and the bullets (•) indicate the branch with a bootstrap value >0.70. Visualization was created by using online software tool iTOL v.5. HET-MO, Heterosexual Military Officers; TSWS, Transgender Women Sex Workers; GTR, General Time-Reversible; iTOL, Interactive Tree Of Life.

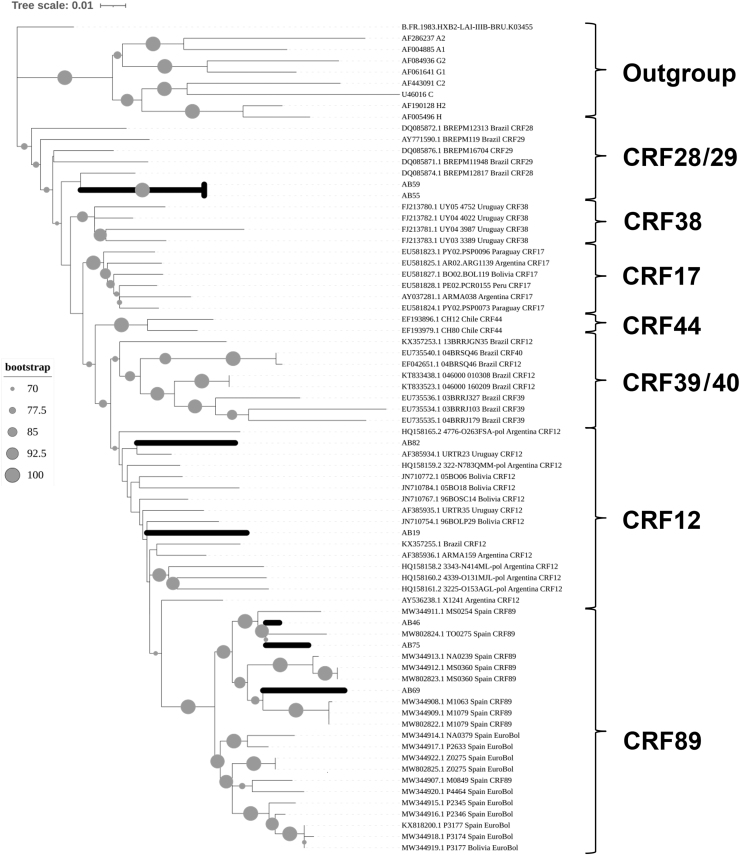

On the other hand, we have compared the recombination events in the pol gene for both groups by using different recombination analysis software. This analysis showed seven BF cases from TWSW and one AG recombinant from HET-MO (Table 2) previously shown by phylogeny analysis. To know the potential origin and spread of this BF recombinants in South America, we have calculated a phylogenetic tree comparing the Peruvian strains from this study and other 57 South American sequences. According to our results (Fig. 4), we have identified three different BF recombinants circulating from this TWSW population: CRF12 (AB19, AB82), CRF89 (samples AB46, AB69, AB75), and the recombinant clade CRF28/29 (samples AB55, AB59). Phylogeny analysis revealed that most of these BF recombinants were related to strains from Bolivia, Argentina, and Uruguay.

Table 2.

Recombination Analysis of Eight HIV-1 Species Detected by Four Different Recombination Methods

| Group risk | Lab codea | Length (bp)b | Assignment according to recombination program results |

Recombination final decision | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMET v2.2 | REGA v3 | jpHMM | RIP | ||||

| TWSW | AB55 | 1,059 | Check for 29_BF | Recombinant of B, F1 | BF1 | CON_B, CON_F1 | BF |

| AB46 | 1,059 | CRF 12_BF | CRF 12_BF-like | B | CON_B, CON_F1 | BF | |

| AB75 | 1,059 | CRF 12_BF | CRF 12_BF | B | CON_B, CON_F1 | BF | |

| AB82 | 1,059 | CRF 12_BF | CRF 12_BF | BF1 | CON_B | BF | |

| AB19 | 1,059 | CRF 12_BF | CRF 12_BF | BF1 | CON_B, CON_F1 | BF | |

| AB69 | 1,059 | Check for 29_BF | Recombinant of B,F1 | B | CON_B, CON_F1 | BF | |

| AB59 | 1,059 | Check for 29_BF | Recombinant of B, F1 | BF1 | CON_B, CON_F1 | BF | |

| HET-MO | PM62 | 1,059 | CRF 02_AG | CRF 02_AG | G | CON_A1, CON_G | AG |

The identification code of the study participant.

Base pair of nucleotides.

FIG. 4.

Phylogeny was constructed by comparing seven HIV samples from TWSW (Lab code AB followed by a number) with other HIV referential strains by using Maximum likelihood method implemented in IQ-TREE web server under the best-fit model GTR. The tree was created after 1,000 replicated bootstrap analysis. The Phylogenetic trees visualizations were possible by using iTOL. TWSW, transgender women sex workers.

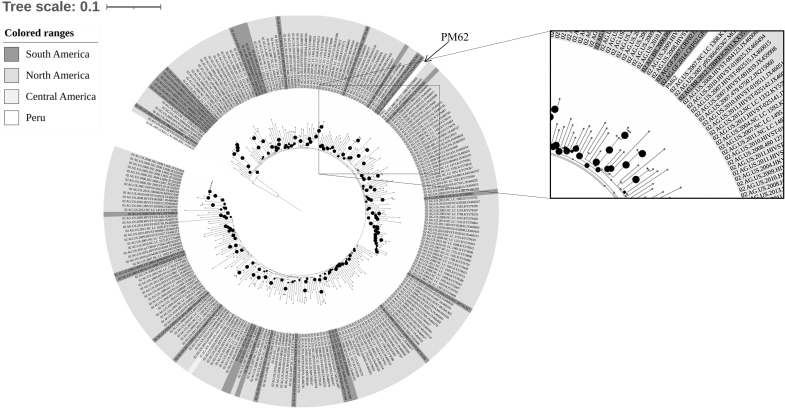

Regarding to AG recombinant found in this study, we have compared this strain with 249 isolates from South, Central, and North America. Phylogeny analysis revealed the Peruvian specimen (PM62) was enclosed into a clade shaped by strains reported in French Guiana (Fig. 5)

FIG. 5.

Phylogeny tree was constructed by analyzing the one HIV sample from HET-MO (Lab Code PM62) with other 249 CRF12_AG nucleotide sequences from South America (French Guiana = 26, Brazil = 5, Ecuador = 2, Peru = 1), Central America (Mexico = 1), and North America (Unites States = 214, Canada = 2). The Maximum Likelihood method was implemented in IQ-TREE web server. The bootstrap consensus tree was inferred from 1,000 replicates. Visualization was created by using online software tool iTOL v.5. The reference B subtype HXB2 was used as outgroup. The black bullets (•) indicate the branches with a bootstrap value above 70%.

Resistance to ART showed divergences between TWSW and HET-MO

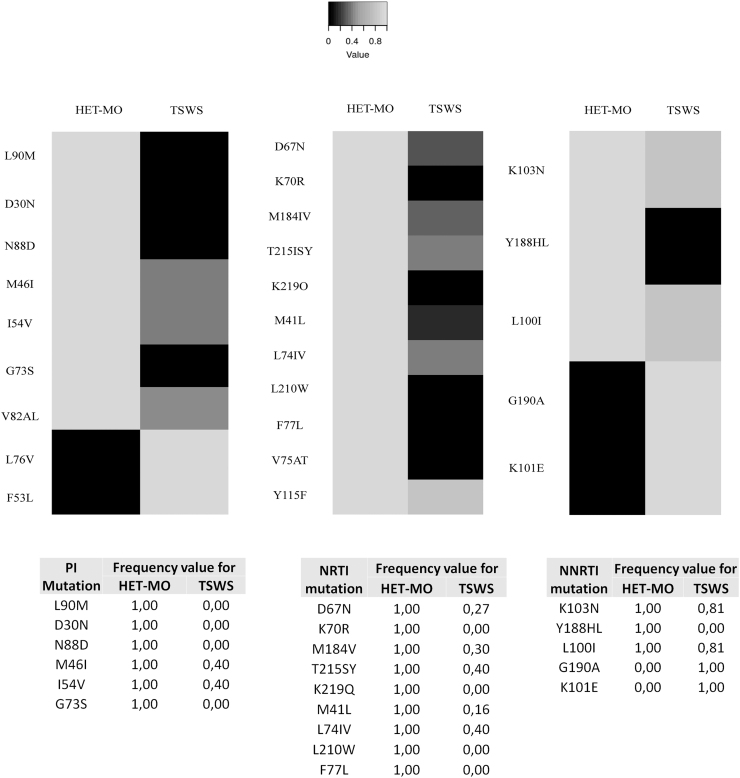

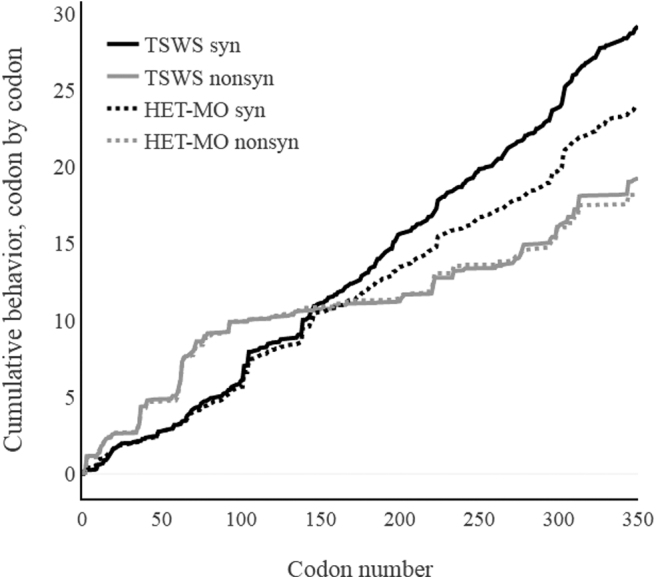

HIV genotyping revealed a group of viral strain that showed drug resistance to ART. Some of these viruses were detected from participants who were not in treatment scheme (naive patients). In this case, we classified the resistance as transmitted drug resistance (TDR). When HIV drug resistance mutations were detected in ART-treated participants, we considered them as acquired drug resistance (ADR). According to genotyping results, 9 mutations were found for PI, 11 for NRTI, and 5 for NNRTI. When we compared each group through a HotPlot graph, the distribution of greyscales evidenced different resistant patterns (Fig. 6). Likewise, we analyzed the HIV-1 resistance profile according to therapy status. Regarding this, our results showed that ADR was higher for HET-MO (26.23%), whereas TDR was detected only among TWSW (9.59) (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

HotPlot showing ART resistance mutations between TSWS and HET-MO. Heat mapper showing ART-related resistance mutations from TSWS and HET-MOT populations. Black square shows the higher mutation frequency value, whereas the light gray square shows the lower frequency value. Frequency value was calculated as follows: Dynamics: Xmut = nmut/ntotal → Xmut = Xmut/max(Xmut). Visualization was obtained by using Heatmapper web server. ART, antiretroviral therapy.

FIG. 7.

Comparison of ADR and TDR frequency (%) between TWSW and HET-MO population. ADR, acquired drug resistance; TDR, transmitted drug resistance.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the genetic divergence and drug resistance profile of HIV-1 infecting two human groups that show different sexual behavior. According to epidemiological characteristics, TWSW showed high frequency of the lower median age participants, early HIV-1 infection status, higher STD infection frequency, high frequency of illegal drug consumption, and inadequate access to ART in comparison to HET-MO. Regarding reduced ART access, probably the barriers of gender identity were the cause of discrimination and the main obstacle to having a registration, admission procedure, and access to ART from health care providers, such as was previously reported in Indian transgender.13 The findings here support the hypothesis that HIV infecting TWSW, and HET-MO have different evolutionary processes according to their group epidemiological characteristics.

According to HIV sequencing analysis we have shown that the evolutionary divergence index of virus infecting TWSW was higher than HET-MO (p < .001). It is important to mention that genetic divergence calculates nucleotide mismatch rates that occur either within or between different hosts. Various factors are also involved within the host, such as viral (rapid viral turnover, high virus burden, and the error-prone nature of the reverse transcriptase enzyme) and host factors (immune response, ART).14 These selective forces contribute to non-conservative and conservative changes, which always is higher within than between hosts, including during a prolonged infection course.15

In this study, we analyzed only the molecular divergence between hosts. Other forces related to the transmission speed are also involved. One example of this phenomenon is the Intravenous Drug Users (IDU) population. The transmission rate is too fast and does not give enough time to drive the HIV-1 evolution by the host immune system.16 Thus, various natural barriers to the host play an essential role in increasing the evolutionary rate of HIV-1. In the case of our study, we found that TWSW showed more evolutionary divergence than HET-MO (Fig. 2), suggesting that some epidemiological factors related to this group might be involved in this significant difference.

In TWSW, they are potential recipients of new HIV-1 particles transmitted by various clients (donors) because of the sexual work. Still, in contrast to the transmission speed in IDUs, in TWSW all these new viral particles have enough time to establish a new genetic population, which gives a chance for selection to new genetic variants by the bottleneck,17 thus promoting the genetic divergence. According to the experiments conducted in this study, we cannot show that evolutionary divergence is a direct result of multiple sexual partners infecting every TWSW. However, this first evidence can be helpful to perform additional studies focused on showing HIV superinfection or mixed infections such as previously reported by other studies.18,19

Regarding the accumulative dS/dN index, the higher index of non-synonymous changes observed in protease could be related to the high diversity of this gene because of selective factors such as ART.20 Despite this, it has shown that protease diversity does not affect the HIV-1 replication capacity,21 explaining why this phenomenon occurred indistinguishably either HET-MO as TWSW.

On the other hand, we found that the predominant HIV-1 genetic variant was subtype B (93%), in concordance with a previous study performed in the general population.12 Subtype B is the primary strain circulating in South America, and it has been associated with MSM.8,22 Although its origin is still unclear, phylogenic approaches revealed that Brazil, Argentina, and Venezuela are the key countries where subtype B began to expand to other regions, probably due to the constant migrations.23

Of interest, we detected a case of HIV-1 subtype A from a TWSW. Similarly, one case of this subtype was also found in the Peruvian general population according to a previous study,12 suggesting that HIV subtype A is circulating in Peru, although at a low prevalence. Since this variant is now circulating in individuals engaging high-risk sexual behavior, this suggests that it might increase in the following years because of the sexual work activity. However, some viral factors such as replication capacity, transmission, or pathogenesis of this variant could also increase the prevalence.

According to our data, we have identified eight different recombination forms from HIV-1 samples. It is important to mention that the recombination events lead to increased HIV-1 diversity and contribute to its evolution,24 resulting in improved replicative capacity,25 evasion of the immune system,26 and increased ARV drug resistance.27 Some studies have shown that HIV-1 recombination is the result of simultaneous superinfection of different HIV-1 genetic variants producing intra- and inter-subtype recombination in vitro28,29 and in vivo.18,19

Considering this evidence, BF recombination cases found in TWSW might result from B and F subtypes co-infecting different patients in Peru. However, since pure subtype F strains have never been reported in Peru, it is more feasible that a recombinant strain BF has arrived in Peru, likely from other countries. For this issue, we have performed a phylogeny analysis comparing either BF as AG virus with other viral strains previously reported. Regarding of BF virus, we have found at least three different recombinants: CRF012_BF, CRF89_BF and CRF_BF28/29 circulating in Lima and Callao cities. In the case of CRF012_BF, it has been previously reported for us until now.12

According to our phylogeny analysis, Peruvian viruses were related to Argentinian, Uruguayan, and Bolivian strains. This is concordant with the Argentinian origin of CRF012_BF, which probably originated almost immediately after the F/BF epidemic.30 Of interest, we have also found three samples that were grouped into a new clade recently described as “Peruvian Sub-cluster” CRF89_BF.31 An important issue is that this recombinant virus was transmitted to Spanish individuals by homosexual contact with Peruvian immigrants.31 Contrasting this information with the sexual behavior of participants from our study, it is possible that “Peruvian CRF89_BF” might have been transmitted by a sexual network integrated by MSM and establishing a new transmission route from South America to Europe.

However, more molecular epidemiological studies are required to show this. Since the Peruvian sub-cluster is different than Bolivian and Euro-Bolivian strains, this suggests that some non-virological factors that are country-dependent might be playing an important role on diversification of the recombinant virus. Therefore, further molecular epidemiology studies will be required to determine whether “Peruvian sub-cluster” introduction into European countries will follow the same diversification.

It is noteworthy that we have found two virus strains in the clade CRF28/29, which might be the first report of new recombinant viruses circulating in Lima, Peru. According to previous reports, the CRF28/29 clade originated in the southeastern region of Brazil between 1985 and 1990 with high association with subtype B circulating in that country.32,33 CRF28 and CRF29 are grouped into a monophyletic group, which suggests that they originated from a common antecessor.34 Of importance, CRF28/29 clade was responsible for more than 6.4% of total infections in Brazil during the 1980s and early 1990s, showing high fitness and transmissibility.32,34

These data suggest that the presence of this variant could be relevant in the AIDS epidemics in Peru, especially if this clade shows differences among resistance profiles, responses to antiviral interventions, and other biological properties. Therefore, a national surveillance of genetic variants is required to identify the real prevalence of this recombinant virus in Peru.

Of interest, one sample from HET-MO showed recombination type CRF02_AG. This genetic variant is dominant in West Africa35 and probably arrived first in Brazil. It is then disseminated throughout Rio de Janeiro state by vertical and horizontal transmission.36 Prior to this report, CRF02_AG has been found from punctual cases in Ecuador,37 Venezuela,38 and Argentina.39 These pieces of evidence suggest that CRF02_AG probably appeared recently because of its continuous transmission reported to date.

Phylogeny analysis revealed that the Peruvian strain was related to a recombinant virus identified in French Guiana. According to the epidemiological questionnaire, the participant infected with this variant was revealed not to have traveled to another country or have had sexual contact with a foreigner partner (Data not shown). These data suggest that CRF02_AG would have already been circulating in Peru, although the precise date from the first case remains unknown. Therefore, more molecular epidemiological studies are required to identify the origin and transmission of this recombinant virus in Peru and South America.

Our findings revealed evidence of ARV drug resistance in TWSW as HET-MO; however, both groups showed substantial differences. According to our results, only TDR was identified from TWSW (8.64%), which is consistent with the fact that TDR is mainly associated with sexual intercourse.40 A similar study that recruited 62 Argentinian TWSW described a high TDR frequency (19%).41 These data suggest that TDR is frequent in TWSW, which might increase the risk of ART failure in their recently infected clients.

A study from 140 Peruvian TW recently revealed a TDR prevalence of 11.4% (16/140).42 Although there is no information on the employment situation of this risk group, it is likely that most of them were involved in sex work, due to the diminished socioeconomic status frequently reported in this vulnerable group.43 Consequently, more effort focused on the TDR surveillance should be performed in this risk group to monitor the drug resistance status and HIV-1 transmission.

On the other hand, we have identified that TWSW were younger than HET-MO. Thirteen of 15 TWSW were between 20 and 31 years old and showed TDR (data not shown). Youth status might also be an important factor in TDR transmission since it has been previously demonstrated that unprotected sexual intercourse was associated with age <35 (OR = 7.5; p = .009).44 Lower condom use has also been associated with stigma (coercive partners and clients) and inadequate HIV knowledge, which was very frequent from the younger TWSW population.45

Finally, it has been reported that TWSW clients take ART in Peru,46 which could be an important risk since a percent of them might be infected with an HIV drug-resistant strain, which increases the probability to transmit resistant genotypes to this vulnerable group.

Conclusion

We showed that sexual behavior in some human groups alters the genetic diversity, recombination, and resistance profile of HIV, making it one phenomenon that is able to promote the virus evolution. This study also reflects the lack of health care access and formal work that the HIV-positive TWSW population must face to survive. Therefore, it is imperative to begin new studies focused on developing strategies that are needed to minimize the risk and harm that sexual work exerts on TWSW.

The tactic implemented might help decrease the transmission and viral fitness and reduce disparities. This study also showed consistent evidence that HIV-1 follows different evolution directions depending on sexual behavior. Despite this, the study's main weakness is the low number of participants. In the context of this pandemic, sexual transmission is the primary mechanism in the world and the more challenging to fight.

Sequence Data

The Genbank accession numbers for the HIV-1 sequences that were submitted are MW616278—MW616343 (for TWSW), and MW616344—MW616409 (for HET-MO)

Authors' Contributions

C.A.Y., research conception. G.V., S.E., F.L., A.V., M.A., D.S., E.M., P.L., and V.R.-A. acquisition of data. C.A.Y., R.R., J.S., S.R., and F.C. analyzed and interpreted the data. C.A.Y., G.V., S.E., F.L., A.V., M.A., D.S., E.M., R.R., J.S., G.O., S.R., F.C., P.L., and V.R.-A. Critical revision of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the Instituto Nacional de Salud de Perú (Peruvian National Institute of Health) and the National Institutes of Minority Health and Health Disparities (U54MD007579).

Correction added on December 23, 2021 after first online publication November 22, 2021: The funding number has been changed from MD007579 to U54MD007579.

References

- 1. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV-1/AIDS (UNAIDS): Global AIDS update. Confronting inequalities. Lessons for pandemic responses from 40 years of AIDS, 2021. Available at https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2021-global-aids-update_en.pdf, accessed November 12, 2021.

- 2. Situación epidemiológica del VIH-Sida en el Perú: Boletín Mensual. Available at: https://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/vih/Boletin_2021/febrero.pdf (2021), accessed August 12, 2021.

- 3. Bastos FI, Cáceres C, Galvão J, Veras MA, Castilho EA: AIDS in Latin America: Assessing the current status of the epidemic and the ongoing response. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cárcamo CP, Campos PE, García PJ, et al. : Prevalences of sexually transmitted infections in young adults and female sex workers in Peru: A national population-based survey. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:765–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Silva-Santisteban A, Raymond HF, Salazar X, et al. : Understanding the HIV/AIDS epidemic in transgender women of Lima, Peru: Results from a sero-epidemiologic study using respondent driven sampling. AIDS Behav 2012;16:872–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Operario D, Soma T, Underhill K: Sex work and HIV-1 status among transgender women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;48:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vrancken B, Baele G, Vandamme AM, van Laethem K, Suchard MA, Lemey P: Disentangling the impact of within-host evolution and transmission dynamics on the tempo of HIV-1-1 evolution. AIDS 2015;29:1549–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Avila MM, Pando MA, Carrion G, et al. : Two HIV-1 epidemics in Argentina: Different genetic subtypes associated with different risk groups. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2002;29:422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lam CR, Holtz TH, Leelawiwat W, et al. : Subtypes and risk behaviors among incident HIV-1 cases in the Bangkok men who have sex with men cohort study, Thailand, 2006–2014. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2017;33:1004–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yabar CA, Salvatierra J, Quijano E: Polymorphism, recombination, and mutations in HIV type 1 gag-infecting Peruvian male sex workers. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2008;24:1405–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yabar C, Salvatierra J, Quijano E: Variabilidad del gen de la envoltura del VIH-1 en tres grupos humanos con diferentes conductas sexuales de riesgo para adquirir ITS-VIH. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica 2007;24:202–210. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yabar CA, Acuña M, Gazzo C, et al. : New subtypes and genetic recombination in HIV-1 type 1-infecting patients with highly active antiretroviral therapy in Peru (2008–2010). AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2012;28:1712–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Shunmugam M, Dubrow R: Barriers to free antiretroviral treatment access among kothi-identified men who have sex with men and aravanis (transgender women) in Chennai, India. AIDS Care 2011;23:1687–1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tebit DM, Nankya I, Arts EJ, Gao Y: HIV-1 diversity, recombination and disease progression: How does fitness “fit” into the puzzle? AIDS Rev 2007;9:75–87. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lythgoe KA, Fraser C: New insights into the evolutionary rate of HIV-1-1 at the within-host and epidemiological levels. Proc Biol Sci 2012;279:3367–3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maljkovic Berry I, Ribeiro R, Kothari M, et al. : Unequal evolutionary rates in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1-1) pandemic: The evolutionary rate of HIV-1-1 slows down when the epidemic rate increases. J Virol 2007;81:10625–10635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boeras DI, Hraber PT, Hurlston M, et al. : Role of donor genital tract HIV-1 diversity in the transmission bottleneck. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:E1156–E1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koning FA, Badhan A, Shaw S, Fisher M, Mbisa JL, Cane PA: Dynamics of HIV-1 type 1 recombination following superinfection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013;29:963–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fang G, Weiser B, Kuiken C, et al. : Recombination following superinfection by HIV-1. AIDS 2004;18:153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pennings PS, Kryazhimskiy S, Wakeley J: Loss and recovery of genetic diversity in adapting populations of HIV. PLoS Genet 2014;10:e1004000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Capel E, Martrus G, Parera M, Clotet B, Martínez MA: Evolution of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease: Effects on viral replication capacity and protease robustness. J Gen Virol 2012;93(Pt12):2625–2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Montano SM, Sanchez JL, Laguna-Torres A, et al. : Prevalences, genotypes, and risk factors for HIV transmission in South America. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005;40:57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Junqueira DM, de Medeiros RM, Gräf T, Almeida SE: Short-term dynamic and local epidemiological trends in the South American HIV-1-1B epidemic. PLoS One 2016;11:e0156712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rambaut A, Posada D, Crandall KA, Holmes EC: The causes and consequences of HIV-1 evolution. Nat Rev Genet 2004;5:52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buzón MJ, Wrin T, Codoñer FM, et al. : Combined antiretroviral therapy and immune pressure lead to in vivo HIV-1 recombination with ancestral viral genomes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;57:109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mostowy R, Kouyos RD, Fouchet D, Bonhoeffer S: The role of recombination for the coevolutionary dynamics of HIV-1 and the immune response. PLoS One 2011;6:e16052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang M, Foley B, Schultz AK, et al. : The role of recombination in the emergence of a complex and dynamic HIV epidemic. Retrovirology 2010;7:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Steain MC, Wang B, Saksena NK: The possible contribution of HIV-1-induced syncytia to the generation of intersubtype recombinants in vitro. AIDS 2008;22:1009–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kuwata T, Miyazaki Y, Igarashi T, Takehisa J, Hayami M: The rapid spread of recombinants during a natural in vitro infection with two human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains. J Virol 1997;71:7088–7091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dilernia DA, Jones LR, Pando MA, et al. : Analysis of HIV type 1 BF recombinant sequences from South America dates the origin of CRF12_BF to a recombination event in the 1970s. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2011;27:569–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Delgado E, Fernández-García A, Pérez-Losada M, et al. : Identification of CRF89_BF, a new member of an HIV-1 circulating BF intersubtype recombinant form family widely spread in South America. Sci Rep 2021;11:11442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Sá Filho DJ, Sucupira MC, Caseiro MM, Sabino EC, Diaz RS, Janini LM: Identification of two HIV type 1 circulating recombinant forms in Brazil. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2006;22:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Melo FL, Jamal LF, Zanotto PM: Characterization of primary isolates of HIV type 1 CRF28_BF, CRF29_BF, and unique BF recombinants circulating in São Paulo, Brazil. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2012;28:1082–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ristic N, Zukurov J, Alkmim W, Diaz RS, Janini LM, Chin MP: Analysis of the origin and evolutionary history of HIV-1 CRF28_BF and CRF29_BF reveals a decreasing prevalence in the AIDS epidemic of Brazil. PLoS One 2011;6:e17485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bbosa N, Kaleebu P, Ssemwanga D: HIV-1 subtype diversity worldwide. Curr Opin HIV-1 AIDS 2019;14:153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Delatorre EO, Bello G, Eyer-Silva WA, Chequer-Fernandez SL, Morgado MG, Couto-Fernandez JC: Evidence of multiple introductions and autochthonous transmission of the HIV-1 type 1 CRF02_AG clade in Brazil. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2012;28:1369–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Carrion G, Hierholzer J, Montano S, et al. : Circulating recombinant form CRF02_AG in South America. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2003;19:329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rangel HR, Garzaro D, Gutiérrez CR, et al. : HIV diversity in Venezuela: Predominance of HIV type 1 subtype B and genomic characterization of non-B variants. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2009;25:347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fernández MF, Golemba MD, Terrones C, et al. : Short communication: Emergence of novel A/G recombinant HIV-1 strains in Argentina. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2015;31:293–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Drumright LN, Frost SD: Sexual networks and the transmission of drug-resistant HIV-1. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2008;21:644–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carobene M, Bolcic F, Farías MS, Quarleri J, Avila MM: HIV-1, HBV, and HCV molecular epidemiology among trans (transvestites, transsexuals, and transgender) sex workers in Argentina. J Med Virol 2014;86:64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Trebelcock WL, Lama JR, Duerr A, et al. : HIV pretreatment drug resistance among cisgender MSM and transgender women from Lima, Peru. J Int AIDS Soc 2019;22:e25411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, et al. : Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: A review. Lancet 2016;388:412–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chin-Hong PV, Deeks SG, Liegler T, et al. : High-risk sexual behavior in adults with genotypically proven antiretroviral-resistant HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005;40:463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Budhwani H, Hearld KR, Hasbun J, et al. : Transgender female sex workers' HIV knowledge, experienced stigma, and condom use in the Dominican Republic. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Degtyar A, George PE, Mallma P, Diaz DA, Cárcamo C, Garcia PJ: Sexual risk, behavior, and HIV-1 testing and status among male and transgender women sex workers and their clients in Lima, Peru. Int J Sex Health 2018;30:81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]