Abstract

The psychosocial needs and experiences of transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people is an understudied area of oncology research. In response to calls to action from past researchers, we conducted a scoping review, which included published and gray literature. From the included articles, the following key themes were identified: (1) lack of coordination between gender-affirming care and cancer care; (2) impact of cancer care on gender affirmation; (3) navigating gendered assumptions; (4) variation in providers' understanding of the needs of TGD patients; and (5) lack of TGD-specific cancer resources. Following this review, we consulted 18 key stakeholders with TGD-relevant personal and/or professional experience to gain further insight into issues that were not encompassed by the original themes. Based on these themes and stakeholder feedback, we offer recommendations for future research and clinical practice to increase awareness of the psychosocial needs of TGD people who have been diagnosed with cancer and to improve patient care.

Keywords: cancer, cancer care, gender diverse, health disparities, scoping review, transgender

Introduction

Along with physical consequences, cancer can have debilitating psychosocial impacts, including mood disturbance, sleep disruption, and persistent fatigue.1–3 Although these psychosocial impacts affect every survivor demographic, they may have a more negative impact on individuals from sexual and gender minority groups, who face unique survivorship challenges due in part to their already precarious social position before cancer diagnosis.4 Much research to date has been conducted on the psychosocial needs and experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) cancer survivors as a whole.5 However, less is known about the unique needs and experiences of transgender (i.e., people whose sex assigned at birth is incongruent with their gender identity) and gender diverse (i.e., people whose gender identity does not conform to traditional binary gender norms) cancer survivors. In this review, we will use “transgender and gender diverse (TGD)” to encompass a range of gender identities and expressions.

TGD individuals are often lumped together with cisgender (i.e., those whose sex assigned at birth is congruent with their gender identity) lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer (LGBQ) people in research. This does not allow for an understanding of their unique experiences. Sexual orientation and gender identity are separate components of a person's identity, and everyone possesses both. However, most of the existing literature has focused on sexual orientation and has not given sufficient attention to the unique experiences of TGD people. For example, TGD people often experience higher levels of psychological distress,6,7 and more negative experiences within the health care system8,9 than their cisgender LGBQ counterparts. In a large-scale Canadian survey of 2873 transgender and nonbinary people, 45% reported one or more unmet medical needs, and 12% reported avoiding emergency room visits during the past year.10 A similar study of 27,715 transgender people conducted in the United States found that one third of participants reported at least one negative experience with a health care provider in the past year.11 Furthermore, 23% did not seek medical treatment when needed due to fear of mistreatment.11

Cancer can be a very gendered experience: for example, breast and gynecologic cancers are often considered “female” cancers, and prostate and testicular cancers are often considered “male” cancers. Therefore, it is important to examine the experiences of TGD people who may not conform to the gender that providers typically associate with a type of cancer (e.g., a man with cervical cancer or a woman with prostate cancer are not scenarios that many researchers or health care providers expect). Considerations such as these are important because they may affect how TGD people who have been diagnosed with cancer are treated by providers, how they experience treatment, and how they may conceptualize their cancer within the context of their gender identity.

To date, much of the existing literature assessing TGD people diagnosed with cancer separately from their cisgender LGBQ counterparts has focused on biomedical aspects of their experiences, particularly relating to aspects of gender-affirming care (e.g., whether patients had to discontinue hormone therapy, change plans for gender-affirming surgeries).12 Although it is important to consider these factors, there are psychosocial aspects of their experiences that must be assessed and addressed. There is an identified knowledge gap in the psychosocial needs and experiences of TGD people diagnosed with cancer, and calls to action for psychosocial oncology researchers have been issued.13,14 Through our scoping review, we aim to answer the following research question: “What are the psychosocial needs and experiences of TGD individuals with cancer?” This will be accomplished by (1) systematically mapping the available literature and identifying key concepts, and (2) highlighting knowledge gaps and providing recommendations for future research and clinical practice.

Methods

To structure our review, we applied the six-step scoping review framework by Levac et al.,15 which is an expansion of the framework by Arksey and O'Malley.16 The first step of this expanded framework was to create the research question outlined above.

Search methods

The second step is selecting relevant studies; to do so, we searched PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBase, and the gray literature. Several terms related to gender identity, cancer, and psychosocial needs and experiences were searched. We limited our search to articles published from January 2000 to December 2020 to obtain the most up-to-date information. An example of the PubMed search string is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample PubMed Search String

| ((“transgender persons”[MeSH Terms] OR (“transgender”[All Fields] AND “persons”[All Fields]) OR “transgender persons”[All Fields] OR “transgender”[All Fields]) OR transsexual[All Fields] OR non-binary[All Fields] OR gender-nonconforming[All Fields]) AND ((“neoplasms”[MeSH Terms] OR “neoplasms”[All Fields] OR “cancer”[All Fields]) OR (“carcinoma”[MeSH Terms] OR “carcinoma”[All Fields]) OR (“neoplasms”[MeSH Terms] OR “neoplasms”[All Fields] OR “neoplasm”[All Fields])) AND (“2000/01/01”[PDAT]: “2020/12/31”[PDAT]) |

Study selection

The third step was study selection, which was completed using predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eligible studies included TGD people who have been diagnosed with cancer, assessed their responses separately from those of their cisgender LGBQ counterparts, and assessed their psychosocial needs and experiences with cancer care (i.e., treatment itself, interactions with care providers and clinic staff, support groups). For the purposes of our review, we allowed for the inclusion of all types of studies (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, cohort). Excluded studies were those that did not include TGD people with cancer or, if this criterion was fulfilled, did not assess their responses separately from their cisgender LGBQ counterparts. Studies were also excluded if their sole focus was on the biomedical cancer experiences of TGD people with no focus on the psychosocial aspects (e.g., subjective thoughts and feelings, mental health, quality of life). Studies identified through our searches were exported to Rayyan17; title/abstract and full-text reviews were completed by two independent reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus or arbitration by a senior review team member.

Data analysis

Included studies were charted and reviewed to assess common themes using thematic analysis, addressing steps four and five of the Levac et al. framework.15 Quotations presented in each of the included articles were extracted and grouped based on the following common themes: lack of coordination between gender-affirming care and cancer care; impact of cancer care on gender affirmation; navigating gendered assumptions; variation in providers' understanding of the needs of patients; and, lack of TGD-specific cancer resources.

Consultation with key stakeholders

Finally, we conducted an online survey-based consultation with key stakeholders, fulfilling the sixth step of the framework. Key stakeholders were those with lived experience as a TGD person with a current or past cancer diagnosis, researchers or clinicians in TGD health, and/or those who work to support and advocate for TGD people. After informed consent was obtained through the online survey platform, stakeholders were presented with demographic questions and invited to answer seven open-ended questions (shown in Table 2) about our identified themes and initial recommendations. Researchers of TGD health were identified through relevant articles in PubMed and recruited through email. Members of stakeholder groups (i.e., TGD people with lived cancer experience and those who work to support/advocate for the TGD community) were recruited through social media posts and emails sent to groups and organizations created to support TGD people and people who have been diagnosed with cancer. All stakeholders were asked to share the survey with eligible people in their network through word of mouth or sharing social media posts about the survey.

Table 2.

Open-Ended Questions Delivered to Key Stakeholders as Part of the Stakeholder Consultation

| (1) Do you believe there are emerging or unaddressed cancer-related issues for individuals who are trans or gender diverse that were not encompassed by the current review? If yes, what are these issues? |

| (2) In your opinion, how feasible are the research and clinical recommendations made in the current review? |

| (3) In your opinion, how do you think the implementation of the research and clinical recommendations will impact future cancer experiences of individuals who are trans or gender diverse? |

| (4) What do you think are the most important areas for future research surrounding the cancer-related needs and experiences of people who are trans and gender diverse (i.e., what do you think future researchers should focus on)? |

| (5) Based on your personal and/or professional experience, what do you think should be done to make people who are trans and gender diverse more comfortable during cancer treatment and beyond? |

| (6) What would you like others to know about the experience of cancer as a person who is trans or gender diverse? |

| (7) Are there any additional comments or points you would like to make that were not captured by the other questions? |

Question 6 was presented only to those stakeholders who indicated that they were a transgender and/or gender diverse person and had been diagnosed with cancer.

Because Levac et al.15 did not provide instructions regarding the implementation of stakeholder feedback in step six of their updated framework, we employed a technique whereby our results and initial recommendations were compared with the feedback of key stakeholders. Where disagreements and criticisms were identified, stakeholder feedback was integrated to improve the recommendations.

Ethics approval

The literature review portion of our study was exempt from review as outlined by Memorial University's Interdisciplinary Committee on Ethics in Human Research (ICEHR) because it did not require data collection from human participants. The stakeholder consultation portion was designed in accordance with the Tri-Council Policy Statement on Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans and was approved by the Memorial University ICEHR.

Results

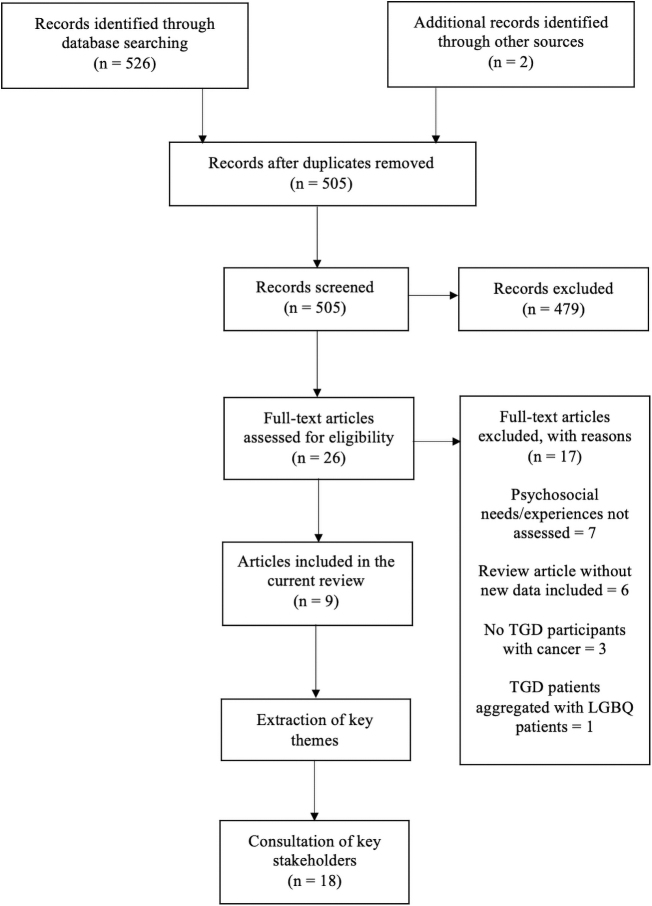

Database and other searches returned 528 unique citations and 26 articles underwent full-text screening, with 9 meeting our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). We identified seven eligible articles through online database searches18–24 and two additional articles through snowball techniques,4,25 including searching the reference lists of included studies and manually searching for relevant studies by the authors of the included studies that were not initially identified. All were qualitative and utilized interviews or open-ended survey questions to better understand participants' thoughts, feelings, and opinions regarding their experiences of cancer.

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram of the scoping literature review study design. LGBQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer; TGD, transgender and gender diverse.

As seen in Table 3, two of the included articles were case studies of transgender women: one diagnosed with breast cancer,20 and another diagnosed with testicular cancer.23 Four articles focused on transgender men and people who were assigned female sex at birth who were gender-nonconforming, genderqueer, or Two-Spirit that had been diagnosed with breast or gynecologic cancers18,19,22,25; three of these articles used data from the same dataset.19,22,25 Two articles included transgender men and women4,21; both used data from an online survey conducted by Margolies and Scout,24 which was also included in our review. All of the included studies were conducted in the United States or Canada. Six articles included cisgender people in addition to TGD people,4,18,19,21,24,25 while the remaining three solely included TGD people.20,22,23 For the purposes of this review, we focused only on the responses given by TGD people who had been diagnosed with cancer in the case of articles in which cisgender people were also included.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Included Articles and Corresponding Themes

| Authors | Publication year | Country | Sample/population gender identity | Type of cancer | Type of study | Corresponding theme(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kamen4 | 2018 | United States | 273 (7 Transgender men; 2 transgender women; 121 cisgender women; 139 cisgender men; 2 other; 2 did not specify) | Any type of cancer | Review article with quotes taken from an online survey to emphasize key points24 | Variation in providers' understanding of the needs of TGD patients |

| Brown and McElroy18 | 2018 | United States | 68 (58 Cisgender women; 10 genderqueer or transgender) | Breast cancer | Cross-sectional survey with open-ended questions | Impact of cancer care on gender affirmation Navigating gendered assumptions Variation in providers' understanding of the needs of TGD patients |

| Bryson et al.19 | 2020 | Canada/United States | 81 (7 Trans; 3 gender-nonconforming; 38 genderqueer; 33 cisgender women) | Breast and gynecologic cancers | Qualitative interview-based study as part of Cancer's Margins project | Impact of cancer care on gender affirmation Navigating gendered assumptions Variation in providers' understanding of the needs of TGD patients |

| Dhand and Dhaliwal20 | 2010 | United States | 58-Year-old African American transgender woman | Breast cancer | Case study | Lack of coordination between cancer care and gender-affirming care |

| Kamen et al.21 | 2019 | United States | 273 (7 Transgender men; 2 transgender women; 121 cisgender women; 139 cisgender men; 2 other; 2 did not specify) | Any type of cancer | Qualitative analysis of two open-ended questions included in an online survey24 | Variation in providers' understanding of the needs of TGD patients |

| Taylor and Bryson22 | 2016 | Canada/United States | 10 (2 Trans men; 2 female-to-male; 1 butch; 1 genderqueer; 1 trans man/trans male; 1 genderqueer/trans/Two-Spirit/butch; 1 butch/gender-nonconforming; 1 genderfluid/transgender) | Breast and gynecologic cancers | Qualitative interview-based study as part of Cancer's Margins project | Lack of coordination between cancer care and gender-affirming care Impact of cancer care on gender affirmation Navigating gendered assumptions Lack of TGD-specific cancer resources |

| Wolf-Gould and Wolf-Gould23 | 2016 | United States | 28-Year-old transgender woman | Testicular cancer | Case study | Impact of cancer care on gender affirmation Variation in providers' understanding of the needs of TGD patients |

| Margolies and Scout24 | 2013 | United States | 311 (10 Transgender; 165 male; 131 female; 5 no response) | Any type of cancer | Correlational survey with two optional open-ended questions | Variation in providers' understanding of the needs of TGD patients |

| Taylor et al.25 | 2019 | Canada/United States | 81 (7 Trans; 3 gender-nonconforming; 38 genderqueer; 33 cisgender women) | Breast and gynecologic cancers | Qualitative interview-based study as part of Cancer's Margins project | Lack of coordination between cancer care and gender-affirming care Lack of TGD-specific cancer resources |

The terms used to describe the gender identities of the people in the study samples/populations are taken from the studies themselves.

TGD, transgender and gender diverse.

The stakeholder survey garnered 26 responses, of which 8 were excluded due to insufficient data (7 with no responses recorded and 1 with responses to demographic questions only), leaving a total of 18 responses. Stakeholder demographic characteristics are presented in Table 4. The majority (44%) of stakeholders resided in the United States, self-identified as White or Caucasian (67%), transgender and/or gender diverse (44%), and as researchers with or without additional advocacy and lived experience (83%).

Table 4.

Demographic Information of Key Stakeholders

| M (SD) | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 18 | |

| Age | 46.2 (11.9) | |

| Gender identity | ||

| Cisgender woman | 4 | |

| Cisgender man | 2 | |

| Cisgender | 2 | |

| Woman | 2 | |

| Transgender man | 2 | |

| Genderqueer | 2 | |

| Transgender woman | 1 | |

| Questioning | 1 | |

| Nonbinary | 1 | |

| Nonbinary woman | 1 | |

| Country of residence | ||

| United States | 8 | |

| Canada | 4 | |

| United Kingdom | 4 | |

| Australia | 2 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White/Caucasian | 12 | |

| Latina | 2 | |

| Mixed Chinese/White | 1 | |

| Arab | 1 | |

| Anglo-Jewish | 1 | |

| No response | 1 | |

| Stakeholder group(s) | ||

| Researchers | 5 | |

| Persons with lived experience | 1 | |

| Advocates | 1 | |

| Other (breast imager radiologist) | 1 | |

| Researchers/advocates | 6 | |

| Researchers/persons with lived experience | 2 | |

| Researchers/advocates/persons with lived experience | 2 | |

The terms used to describe gender identity and race/ethnicity were provided by stakeholders themselves.

M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

Participant responses from the included studies fell into the themes outlined below. Throughout the discussion of relevant themes, when referring to specific participants the gender identity and pronouns they identified in the original articles are used.

Lack of coordination between gender-affirming care and cancer care

Our first theme was the lack of coordination between gender-affirming care and cancer care,20,22 which is a replication of the finding first outlined by Taylor and Bryson22: “Trans* and gender-nonconforming people experience cancer care as disorienting and uncoordinated with their gender-affirming care. Gender-affirming care (e.g., hormone therapy or surgery) is often uncoordinated with cancer care needs (e.g., hormone-related cancers or surgical reconstruction).”22

Participant responses corresponding with this theme described experiencing uncertainty, distress, and a lack of guidance from providers on how aspects of their gender-affirming care could potentially affect cancer treatment and future diagnoses. Three of the included studies were incorporated into this theme.20,22,25 It was particularly evident in the cases of participants who had begun, or intended to begin, hormone treatment for their gender-affirming care, as certain cancers can be exacerbated by increased levels of exogenous hormones.26 As there is still much uncertainty regarding the role of hormone treatment in the development of cancer in TGD people,27 this was a cause of concern for participants. This incongruity may also present itself in patients' beliefs about their cancer and its causes. This is exemplified in a case study of a transgender woman diagnosed with breast cancer, who believed she could not develop breast cancer because she was transgender and was taking injectable estrogen as opposed to pills.20 The extent to which her gender-affirming care providers explained her possible breast cancer risk before starting hormone therapy is unclear.

Impact of cancer care on gender affirmation

Participant responses corresponding with this theme outlined how cancer diagnosis/treatment made them feel about their gender identity/expression. Four studies included responses from participants that described these feelings.18,19,22,23 Although not every TGD person with cancer will decide to undergo surgery as part of their transition, there may be an overlap whereby surgical procedures to treat cancer are perceived as congruent with gender-affirming care.18,19,22 Many participants in the included studies had been diagnosed with breast cancer, so for some the overlap with gender-affirming care came in the form of bilateral mastectomies.18 Participants who already planned to receive “top” surgery (a procedure performed to create a masculine-presenting chest) saw bilateral mastectomy without reconstruction as one way to achieve this goal and have it covered by insurance.18 Select participants also reported a greater awareness of their gender identity after receiving mastectomies to treat their breast cancer.18

However, it is important to know that not all TGD people will perceive this overlap. Some gender-nonconforming people, for example, may not wish to receive certain surgical procedures in order not to be perceived as having a binary gender identity.22 Others may also experience discomfort based on how their diagnosis relates to their gender identity. For example, a transgender woman who had been diagnosed with testicular cancer expressed concern about how she is perceived in medical settings because of her diagnosis.23 This discomfort may contribute to further distress, particularly among those who do not wish to disclose their gender identity.

Navigating gendered assumptions

A theme in several of the identified articles was how participants experienced navigating gendered assumptions. Responses that corresponded with this theme described participants who faced assumptions made by health care providers and the system in general (e.g., through gendered clinic spaces) based on their gender or cancer diagnosis. Three of the included studies incorporated participant responses that fit this theme.18,19,22 The gendered assumptions participants experienced came in many forms, notably regarding the unnecessary gendering of cancer treatment centers,22 and providers making assumptions about what surgical options participants would want based on their perceived gender identity.18,19 Even in situations where there was no (reported) direct conflict, some participants reported worrying about how they were perceived while in the waiting rooms of “women's clinics” for treatment for breast and gynecologic cancers.22 Taking it a step further, a trans man with cervical cancer reported being told he was in the wrong place by clinic staff when he arrived for his appointment.22 Another participant quoted in this article reported being told by clinic staff to wait for his appointment in the hallway instead of the waiting room, while his girlfriend was allowed to stay.22

Although the included studies did not discuss navigating gendered assumptions pertaining to insurance coverage, this can be a major stressor for TGD people in countries without single-payer health care systems. One such issue is “sex mismatch” when filing claims for sex-specific procedures with certain automated systems in the United States.28 When this occurs, claims may be rejected outright in cases where a person's gender identity does not match their sex assigned at birth (e.g., a transgender woman seeking coverage for a prostate biopsy). Although it is possible to override this rejection, not all hospitals or systems may have implemented the code needed to do so,28 which can contribute to further distress among TGD people who have been diagnosed with cancer.

Variation in providers' understanding of the needs of TGD patients

Responses in six of the included studies described variations in understanding from providers.4,18,19,21,23,24 Participants reported varying levels of understanding from their cancer care providers regarding their needs, particularly pertaining to decisions surrounding surgical procedures.18,19 TGD people who elected to undergo bilateral mastectomy without reconstruction to treat their breast cancer, for example, reported interactions with providers ranging from a lack of understanding to a blatant lack of support.18 Namely, one provider asked a participant to speak with a psychiatrist about their decision to forego chest reconstruction, saying they would “suffer gender confusion”18 without reconstruction. Participants also reported subtle negative interactions, including providers asking invasive questions, not using their chosen names, or not taking the time to understand their experiences as a TGD person.21,23,24 Distress can also result when people's support systems have to interact with unsupportive providers. One participant reported feeling distressed because the friends they relied on for support, many of whom were TGD themselves, were made to feel unwelcome by staff and providers.4

Although some providers lacked understanding of their patients' needs, others were supportive. In one instance, a participant's surgeon did not question their decision to have a bilateral mastectomy without chest reconstruction once they made it clear that they were not a straight woman.18 Another reported having a surgeon who was a queer woman of color, and aware of sexual orientation and gender identity,18 who understood why they chose a bilateral mastectomy without reconstruction. Although it is important to highlight the negative impacts of a lack of understanding, the positive impacts of understanding providers cannot be overstated.

Lack of TGD-specific cancer resources

Two of the included studies addressed participants' needs/experiences surrounding TGD-specific cancer resources.22,25 Overall, there is a lack of TGD-specific resources available to people throughout their cancer experience.22,25 Participants generally reported a paucity of cancer resources made for TGD people. Many also reported extreme difficulty when trying to locate anything online to help them understand cancer as it pertained to them. Some were able to locate medical research and connect with peers online, but could not find specific websites with reputable, accessible TGD-specific information about cancer.22 Others tried to discuss resources with their providers, but found they often did not know what to recommend.25 Further challenges presented themselves when participants tried to access peer support groups and were offered groups based on sexual orientation or cancer type, which made them feel as if they did not belong.22

Recommendations for Research and Clinical Practices

The following research and clinical recommendations are based on our literature review themes, preliminary recommendations, and stakeholder feedback. Although an important first step, these recommendations are by no means an exhaustive list. In particular, it is important to acknowledge that our clinical recommendations may not currently be feasible within the existing health care system, a point that was made by one of our key stakeholders. Therefore, our clinical recommendations are presented as goals to reach as we strive to eliminate systemic barriers to implementation. The reflections of key stakeholders do not reflect the experiences of every TGD person with lived experiences of cancer or those who work and conduct research in this area.

Research recommendations

Include psychosocial outcome measures in case studies

Case studies comprise a large portion of the research focused on TGD people diagnosed with cancer. However, few case studies assessed for this review asked the person involved about their feelings and experiences.20,23 It is essential for researchers conducting case studies to include qualitative methods to assess the feelings and experiences of TGD people to add important information and nuance.

Cancer and gender-affirming medical care

As outlined by several stakeholders, TGD people of all ages wishing to access gender-affirming medical care have questions and concerns about what it may mean for future cancer risk and how best to conduct screenings and treatment with it in mind. However, there is little conclusive evidence reported in the current literature that clinicians can use to answer their questions.12 An increased focus on this area would not only make it easier to screen, treat, and have meaningful conversations with TGD people about their gender-affirming medical treatments and their cancer treatments, it could also alleviate any worry and distress they and their families may experience. This could then lead to informed shared decision making among providers, TGD people, and their families pertaining to both gender-affirming care and cancer care.

Need for cross-institutional collaborations

In the case of larger quantitative studies, including measures assessing quality of life, social support, or feelings of distress would provide estimates of the psychosocial burden that TGD people diagnosed with cancer experience. However, recruiting adequate samples to demonstrate psychosocial aspects of the cancer experience for TGD people on a large scale has been difficult for several reasons (e.g., clinic intake procedures not asking about gender identity, mistrust in academic and health care systems). As such, there is a need for cross-institutional collaborations and close stakeholder partnerships. Connecting and collaborating with other researchers and institutions may allow for pooling of quantitative data to provide a more comprehensive picture of what the psychosocial experience is for TGD people during cancer treatment and beyond.

Proper consultation and collaboration with community members

Recruiting TGD participants with lived cancer experience has been difficult due in large part to mistrust. A first step to building and maintaining trust is proper consultation and collaboration with community members. Consulting and building strong relationships with community members may also serve to improve the legitimacy of research projects, which could then improve participation. To this end, it is strongly recommended that all researchers consult the Ethical Guidelines for Research Involving Transgender Communities set out by the Canadian Professional Association for Transgender Health,29 ethical guidelines for recruitment and collaboration with transgender research participants outlined by Vincent,30 or similar ethical guidelines.

Disaggregation of data

Many psychosocial oncology studies are conducted with the LGBTQ community as a whole. In these scenarios it would be beneficial to disaggregate data where possible and assess the responses of TGD participants separately, as their experiences are often very different from those of their cisgender LGBQ counterparts in terms of reported discrimination and psychological distress.31

Include intersectional questions and discussions

Another point outlined by stakeholders was that the current review did not assess the cancer experiences of racial, ethnic, or cultural minority individuals, such as Indigenous people who are transgender or Two-Spirit. When assessing people's experiences within the health care system, it is important to consider how all identities (e.g., race, gender identity, sexual orientation, ability) interact to influence treatment and potential challenges. For example, a recent qualitative study of the health care experiences of transgender people of color found that both race and gender identity influenced how participants were treated by health care providers and the care they received.32 We recommend that researchers assess other facets of participant identities in conjunction with their gender identity. In qualitative studies, for example, this may include asking explicit questions about race, class, ability, etc. In quantitative studies, this may include oversampling individuals from different minority groups, or stratifying samples based on relevant intersectional identities to ensure that all voices are heard.

Clinical recommendations

Create a welcoming environment

Given the close relationship between people with cancer and the clinical teams responsible for their care, it is essential that clinicians understand how to respectfully care for TGD people. This includes making it clear to all patients and their support systems that clinic spaces are welcoming of everyone of any gender identity or expression (e.g., through clearly visible signage). However, some stakeholders noted that indicators of a welcoming environment are not the only considerations needed: additional attention must be paid to tangible improvements to clinic procedures and availability of resources. This includes but is not limited to asking for people's pronouns, and if there is a name they go by other than the name on their medical information, because the name or gender marker on a person's health card, for example, may not correspond with the name and pronouns they use.

It is also important for all oncology providers to understand that feelings of distress and distrust will not disappear with improved intake procedures alone due to past negative experiences within the health care system. TGD people diagnosed with cancer will ultimately require access to resources and supports that reflect their experiences, an area that stakeholders also identified as needing improvement. This includes access to TGD-specific support groups, resources, and transgender patient navigators in the clinic itself.

Prioritize TGD-specific education for health care providers

As outlined by our stakeholders, current and future health care providers must receive education and training that moves beyond simply building awareness to give them the knowledge needed to create a real change. In doing so, cisgender providers will not only have the tools to provide care that is TGD knowledgeable and gender affirming, they will also have the tools to address transphobia in clinic spaces. The need for mandated education is also of particular importance because many health care providers may unknowingly approach interactions with TGD people with assumptions that can be harmful.

Discussion

It is evident from the articles included in our literature review and feedback from key stakeholders that cancer care has the potential to be both at odds, and consistent, with gender-affirming care. Participants in the included studies experienced varying levels of understanding from providers, and some had difficulties navigating gendered assumptions from individuals and institutions. There was consensus that there is a lack of resources specific to TGD people diagnosed with cancer. Although our review provides important information about the psychosocial needs and experiences of TGD people with cancer, our stakeholder consultation identified recommendations for further research and clinical care to close the knowledge gap and improve the experiences of TGD people after a cancer diagnosis.

Ultimately, researchers and clinicians need to understand the diversity within the TGD community and avoid assumptions about what people may want or need based on their gender identity. This is particularly important for those who do not identify with a binary gender identity (e.g., genderqueer or nonbinary people), as providers may make harmful assumptions about their needs based on those of binary transgender people. For example, a study by Lykens et al.33 of 10 genderqueer and nonbinary young adults found that participants often felt misunderstood by health care providers. Even in clinics that provided gender-affirming care, many reported feeling disrespected due to providers' lack of understanding of nonbinary gender identities. Both researchers and clinicians must understand that while TGD people diagnosed with cancer may have needs and experiences that are different from those of their cisgender counterparts, needs and experiences still vary among individual patients.

For the recommendations outlined in this review to have an impact, change must be made at the policy level. As outlined in a recent study by Jackson et al.,34 transgender people may be more likely to be diagnosed with cancer at later stages, have poorer survival, and may be less likely to receive treatment for certain cancers. This is not surprising given that TGD people may avoid cancer screenings because of fears about misunderstanding and/or mistreatment.35 To address this disparity and improve overall outcomes, the psychosocial needs of TGD people who have been diagnosed with cancer must be adequately addressed.

Limitations

Although the recommendations in their current form represent a more comprehensive picture of needed improvements, they represent a fraction of what are systemic issues within health care systems globally. The present review is a critical starting point, but more must be done to make meaningful systemic changes in the treatment of TGD people diagnosed with cancer. Currently, the literature is too limited and heterogeneous to allow for systematic comparisons (e.g., meta-analysis). More research in this area is needed to provide further evidence-based recommendations.

Conclusion

There is an evident need for further research exploring the unique psychosocial needs and experiences of TGD people diagnosed with cancer. The current review outlined five key themes from which we made several research and clinical recommendations to improve the psychosocial care of TGD people throughout cancer treatment and beyond.

Authors' Contributions

L.R.S. contributed to the project's conceptualization, literature search and review, project administration, creation of survey materials, stakeholder recruitment, data analysis, writing of the original draft, reviewing and editing the article, revising the work for important intellectual content, and provided final approval of the version to be published. T.B. contributed to the project's conceptualization, provided resources to the study team, provided consultation based on his professional expertise and personal experience, assisted with the writing of the original draft, revised the work for important intellectual content, and provided final approval of the version to be published. C.S.K. provided resources to the study team and consultation based on his professional expertise in the area of LGBTQ+ psychosocial oncology. He assisted with the writing of the original draft, revised the work for important intellectual content, and provided final approval of the version to be published. S.N.G. contributed to the project's conceptualization, project administration, provided resources to the study team and consultation based on her expertise in the area of psychosocial oncology. She contributed to the writing of the original draft, reviewed and edited the article, revised the work for important intellectual content, and provided final approval of the version to be published. All co-authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and will ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kathryn Dalton for her assistance when screening for eligible articles, and all of the stakeholders who provided the feedback that helped to shape our recommendations.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist. This work is authored by a scientific team diverse in sexual orientations, gender identities, and experiences.

Funding Information

No funding was sought or obtained for this project.

References

- 1. Goedendorp MM, Gielissen MFM, Verhagen CAHHVM, Bleijenberg G: Development of fatigue in cancer survivors: A prospective follow-up study from diagnosis into the year after treatment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kuhnt S, Brähler E, Faller H, et al. : Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in cancer patients. Psychother Psychosom 2016;85:289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Palesh OG, Roscoe JA, Mustian KM, et al. : Prevalence, demographics, and psychological associations of sleep disruption in patients with cancer: University of Rochester Cancer Center-Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:292–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kamen C: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) survivorship. Semin Oncol Nurs 2018;34:52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kamen CS, Smith-Stoner M, Heckler CE, et al. : Social support, self-rated health, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identity disclosure to cancer care providers. Oncol Nurs Forum 2015;42:44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smalley KB, Warren JC, Barefoot KN: Variations in psychological distress between gender and sexual minority groups. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health 2016;20:99–115. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Warren JC, Smalley KB, Barefoot KN: Psychological well-being among transgender and genderqueer individuals. Int J Transgend 2016;17:114–123. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bauer GR, Scheim AI, Deutsch MB, Massarella C: Reported emergency department avoidance, use, and experiences of transgender persons in Ontario, Canada: Results from a respondent-driven sampling survey. Ann Emerg Med 2014;63:713..e1–720.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Macapagal K, Bhatia R, Greene GJ: Differences in healthcare access, use, and experiences within a community sample of racially diverse lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning emerging adults. LGBT Health 2016;3:434–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. The Trans PULSE Canada Team. Health and health care access for trans and non-binary people in Canada. 2020. Available at https://transpulsecanada.ca/results/report-1 Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 11. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, et al. The Report of the 2015 US Transgender Survey. 2016. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality. [Google Scholar]

- 12. McFarlane T, Zajac JD, Cheung AS: Gender-affirming hormone therapy and the risk of sex hormone-dependent tumours in transgender individuals—A systematic review. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2018;89:700–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scime S: Inequities in cancer care among transgender people: Recommendations for change. Can Oncol Nurs J 2019;29:87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Watters Y, Harsh J, Corbett C: Cancer care for transgender patients: Systematic literature review. Int J Transgend 2014;15:136–145. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK: Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arksey H, O'Malley L: Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A: Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown MT, McElroy JA: Sexual and gender minority breast cancer patients choosing bilateral mastectomy without reconstruction: “I now have a body that fits me”. Women Health 2018;58:403–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bryson MK, Taylor ET, Boschman L, et al. : Awkward choreographies from Cancer's Margins: Incommensurabilities of biographical and biomedical knowledge in sexual and/or gender minority cancer patients' treatment. J Med Humanit 2020;41:341–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dhand A, Dhaliwal G: Examining patient conceptions: A case of metastatic breast cancer in an African American male to female transgender patient. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:158–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kamen CS, Alpert A, Margolies L, et al. : “Treat us with dignity”: A qualitative study of the experiences and recommendations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer 2019;27:2525–2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taylor ET, Bryson MK: Cancer's Margins: Trans* and gender nonconforming people's access to knowledge, experiences of cancer health, and decision-making. LGBT Health 2016;3:79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wolf-Gould CS, Wolf-Gould CH: A transgender woman with testicular cancer: A new twist on an old problem. LGBT Health 2016;3:90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Margolies L, Scout NFN: LGBT patient-centered outcomes: Cancer survivors teach us how to improve care for all. 2013. Providence, RI: National LGBT Cancer Network. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taylor ET, Bryson MK, Boschman L, et al. : The Cancer's Margins project: Access to knowledge and its mobilization by LGBQ/T cancer patients. Media Commun 2019;7:102–113. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen WY: Exogenous and endogenous hormones and breast cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;22:573–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Braun H, Nash R, Tangpricha V, et al. : Cancer in transgender people: Evidence and methodological considerations. Epidemiol Rev 2017;39:93–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Deutsch, MB, ed.; University of California San Francisco Transgender Care. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. 2016. Available at https://transcare.ucsf.edu/sites/transcare.ucsf.edu/files/Transgender-PGACG-6-17-16.pdf Accessed April 21, 2021.

- 29. Bauer G, Devor A, Heinz M, et al. : CPATH Ethical Guidelines for Research Involving Transgender People & Communities. 2019. Canada: Canadian Professional Association for Transgender Health. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vincent BW: Studying trans: Recommendations for ethical recruitment and collaboration with transgender participants in academic research. Psychol Sex 2018;9:102–116. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Su D, Irwin JA, Fisher C, et al. : Mental health disparities within the LGBT population: A comparison between transgender and nontransgender individuals. Transgend Health 2016;1:12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Howard SD, Lee KL, Nathan AG, et al. : Healthcare experiences of transgender people of color. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:2068–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lykens JE, LeBlanc AJ, Bockting WO: Healthcare experiences among young adults who identify as genderqueer or nonbinary. LGBT Health 2018;5:191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jackson SS, Han X, Mao Z, et al. : Cancer stage, treatment, and survival among transgender patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021 [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1093/jnci/djab028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dhillon N, Oliffe JL, Kelly MT, Krist J: Bridging barriers to cervical cancer screening in transgender men: A scoping review. Am J Mens Health 2020;14:1557988320925691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]