Abstract

Using data from the 1967–2009 years of the March Current Population Surveys (CPS), we examine two important resources for children’s well-being: time and money. We document trends in parental employment, from the perspective of children, and show what underlies these trends. We find that increases in family work hours mainly reflect movements into jobs by parents—particularly mothers, who in prior decades would have remained at home. This increase in market work has raised incomes for children in the typical two-parent family but not for those in lone-parent households. Time use data from 1975 and 2003–2008 reveal that working parents spend less time engaged in primary childcare than their counterparts without jobs but more than employed peers in previous cohorts. Analysis of 2004 work schedule data suggests that non-daytime work provides an alternative method of coordinating employment schedules for some dual-earner families.

Keywords: Parental employment, Time use, Tag-team parenting

Introduction

Using data from the 1967–2009 years of the March Current Population Surveys (CPS), we examine two important resources for children’s well-being: time and money. We document trends in parental employment patterns, from the perspective of children, and show what underlies these trends. The analysis indicates that families are more engaged in market employment than ever before. In 1967, two-thirds of children had one parent home full-time, and about one-third had all parents working (in this paper, we use “all parents” to mean both parents in two-parent families or one parent in single-parent families); by 2009, the situation had reversed. This change implies that parents have less time available for other activities, including potentially those spent investing in children, and that nonmarket time may be more pressured (Bianchi and Wight 2010).

Increases in family work hours have not resulted primarily from changes in family composition (i.e., the rise of single-parent families) or longer work hours among the employed, but instead mainly reflect movements into jobs by parents—particularly mothers, who in prior decades would have remained at home. This increase in market work has raised incomes for the typical two-parent family, but for lone-parent households, it has largely been required to mitigate a secular decline in income that would otherwise have occurred. Time use data from 1975 and 2003–2008 reveal that employed parents spend less time engaged in primary childcare than their nonworking counterparts but more than job-holding peers in previous cohorts. Finally, analysis of 2004 work schedule data suggests that non-daytime work provides an alternative method of coordinating employment schedules for some dual-earner families.

Background

The trends underlying recent changes in parental employment patterns are well known (see, e.g., Bianchi 2011; Sandberg and Hofferth 2001; Waldfogel 2006). An increasing share of children live with single parents, and a rising fraction of mothers (in both single-parent and two-parent families) work. Our analyses of March CPS data show that the share of children in single-parent families doubled from 13 % to 26 % over the 40-year period ending in 2009, and the proportion whose mother was employed rose from 36 % to 70 % (from 29 % to 64 % for preschool-age children). As a result, the fraction of children in families in which all parents worked grew from 37 % to 66 % (from 28 % to 60 % for preschool-age children).

This article examines these trends and their implications. Our analysis is explicitly child-based because we are interested in investigating potential effects for children of secular changes in parental employment and income, as well as childcare. Thus, whereas most prior analyses have used the family as the unit of observation, we consider how the experience of the typical child has been transformed over time. From a mechanical perspective, the alternative approaches may yield disparate results because fertility rates differ across groups. For instance, the average number of children in single-parent families in which the mother has less than a high school education was 2.7 in 1969 compared with 2.4 in all lone-parent families. One result is that whereas 55 % of single mothers had these low levels of education in that year, this was the case for 59 % of children raised by single mothers. We show herein how adopting a child-based approach makes a difference for some of our results.

More importantly, our use of a child-based approach is motivated by our interest in how children are affected by changing employment arrangements. Our conceptual approach is one in which child outcomes are produced by purchased inputs, parental time investments, and other (unstudied) factors, such as the quality and cost of nonparental childcare or formal education. For instance, a relevant economic model for such an analysis is one in which parents maximize a utility function whose arguments include child outcomes and other (non-child-related) consumption subject to a budget constraint where income (over a specified period) cannot exceed expenditures on child-related inputs and other consumption.1 It is therefore interesting to examine how employment, incomes, and time investments have changed. To the extent that our data permit, this is what we do.

In addition to its child-centered approach, this study differs from most related research by analyzing recent trends in parental employment for all children rather than just selected groups. For instance, Bianchi and Wight (2010) used data from the March CPS to analyze trends (from 1965 to 2005) in maternal employment and current patterns of time allocation for married-couple families with children; their analysis excluded cohabiting couples, single-parent families, and families in which fathers do not work full-time. Earlier analyses of parental employment trends, which included all types of families (such as Bianchi 2000; Sandberg and Hofferth 2001), focused on data prior to 2000 (and again are not child-based).

We provide new evidence on trends, from 1967 to 2009, in the distribution of children across three mutually exclusive categories: all parents work full-time and full-year; at least one parent is home part-time or part-year; or one or more parents are home full-time and full-year.2 We also decompose the factors leading to these changes.

All else equal, increased employment raises family incomes. However, reductions in wages or income transfers (e.g., because of welfare reform) may have motivated increases in employment, resulting in ambiguous changes to family income. Thus, we also evaluate trends in family income, conditional on employment status, and provide evidence on the extent to which increases in work have been accompanied by income gains.

Finally, we are interested in understanding how changes in employment have affected the time that parents spend with children. Parents play a crucial role in the health and cognitive and socioemotional development of children (Waldfogel 2006), and reduced time investments may have negative effects on child well-being because both the quantity and quality of parental time are likely to be important inputs into a child “production function.” Other inputs into the production function include income, nonparental resources (such as the quality of childcare and schooling inputs), and genetic endowments.

However, increases in parental employment may not necessarily reduce time spent with children. Indeed, as detailed herein, a large literature examining trends in parental time has found that growth in market work by mothers has not resulted in large reductions in primary childcare by parents. There are two main reasons for this. First, more intensive parenting norms have increased the time mothers spend on primary childcare, controlling for employment status. Second, resident fathers have become increasingly involved in childcare.

To be more specific, research using historical time use surveys (Aguiar and Hurst 2007; Bianchi et al. 2006; Ramey and Ramey 2010; Sayer et al. 2004) found that hours spent in primary childcare either slightly declined or remained constant from 1965 to the early 1990s, increased substantially from the mid-1990s to 2000–2003, and have flattened since.3 Controlling for changes in demographics and fertility rates over the entire period, Aguiar and Hurst (2007) found that from 1965 to 2003, both men and women, on average, have experienced an increase of 2 hours per week in time spent in childcare.

Thus, while employed mothers spend less time with children than their non-employed counterparts, both groups have increased the time spent with children in recent years (Bianchi 2000; Bianchi et al. 2006; Gauthier et al. 2004; Sayer et al. 2004; Zick and Bryant 1996). Longer work hours reduce total nonmarket time, but employed women have at least partially protected time with children by reducing hours spent in other activities, as detailed later in this article.

In addition, time use studies document that resident fathers have become increasingly involved in providing childcare (Bianchi et al. 2006; Sayer et al. 2004). These changes in maternal and paternal time with children probably reflect some combination of more intensive parenting norms, changing attitudes about the role of fathers, fears about child safety, and increasing returns to human capital investments in children (see, e.g., Ramey and Ramey 2010; Sayer et al. 2004).

A discussion of parental availability would be incomplete without mentioning trends in child availability. Although an examination of children’s out-of-home activities is beyond the scope of this article, other researchers have found that preschool and school-age children are increasingly involved in activities outside the home, including both childcare and extracurricular activities, such as sports, music, and lessons of various kinds (Blau and Currie 2006; Lareau 2003; Lareau and Weninger 2008; Waldfogel 2006). Although extracurricular activities for older children may increase parental time spent transporting and supervising children (Ramey and Ramey 2010), others (such as increased preschool attendance) may serve to equalize the amount of time children of both employed and nonemployed mothers have available to spend with their parents (Bianchi 2000).

Time use surveys provide a detailed portrait of how much time parents spend with children, but they cannot indicate the quality of that time. When parents are working, child and parental well-being may suffer because of lack of sleep, greater time pressure and stress, and increases in multitasking (particularly if parents are taking care of work tasks while also caring for children). Bianchi et al. (2006) found that employment reduces the number of hours spent on housework by married mothers and the number of hours devoted to sleep and other personal care activities by single mothers, and also that the time spent by parents multitasking doubled between 1975 and 2000. On the other hand, delays in childbearing and reduced family sizes imply that each child may get more individualized attention and have parents who are consciously investing in “quality” time with children (Bryant and Zick 1996). Furthermore, new communication technologies, such as cell phones, may keep families more in touch throughout the day, even when parents are not with their children (Galinksy 1999).

In addition, secular changes in average time use may conceal increasing inequalities across types of families. For instance, primary childcare hours have grown more for college-educated than less-educated mothers (Ramey and Ramey 2010) and for nonemployed than for employed mothers (Bianchi et al. 2006), while the increase in childcare by resident fathers has widened disparities between children in single-parent versus two-parent families.

We explore these issues, from a child-based perspective, using time use data from 1975 and 2003–2008, and we also use information from the Work Schedules and Work at Home Supplement to the May 2004 CPS to investigate the frequency of nonstandard work schedules among two-parent families.

Data

Our primary investigation is of parental employment patterns spanning the 43-year period 1967 to 2009, using data from the March CPS, a nationally representative annual survey of noninstitutionalized households that provides detailed information on income, poverty, and labor force participation.4 Each annual survey contains between 23,000 and 65,000 children, totaling nearly 1.9 million children over the 43 years.

Composition of the cross-sectional March CPS changes over time, along with national demographic characteristics. In particular, educational attainment and racial/ethnic diversity have increased, while the share of children living in married-couple families has declined (see Table 7 in the Appendix).5 Because these factors are likely to be correlated with parental employment patterns, we accounted for these changes using a series of regression-adjusted estimates as detailed herein; however, because they do not materially change the main results, we do not display them in the figures.

We classify parental employment patterns, based on usual weekly work hours, as full-time and full-year (≥35 hours per week and ≥50 weeks per year), part-time or part-year (<35 hours per week or <50 weeks per year), or not working.6 Children are classified as belonging to one of three mutually exclusive parental employment categories: all parents work full-time and full-year (i.e., child lives with two parents, both of whom work full-time and full-year, or a single parent who works full-time and full-year); at least one parent is home part-time or part-year; or at least one parent did not work at all (i.e., is home full-time and full-year). In our pooled sample, covering 1967–2009, these categories constituted 27 %, 35 %, and 38 % of children, respectively. Total annual parental work hours are calculated as usual weekly hours times weeks worked during the previous year, summed over all parents in the household.7 We also often examine children in single-parent and two-parent families separately and refer to this distinction as “family structure.” Two-parent families include both married-couple families and those with unmarried cohabiting opposite-sex couples.8 In some estimates, we distinguish families by maternal education (less than high school, high school only, some college, or college degree or more) or child age (0–4, 5–11, or 12–17 years). In our descriptive analyses, weighted data are used so as to provide nationally representative statistics.

March CPS data are also used to investigate how parental employment status is related to total family income. The latter is defined as the sum of all earned (from wages, salaries, business, and farm self-employment) and unearned (from interest, dividends, retirement, child support, public assistance, disability, Social Security, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), unemployment compensation, and veterans’ or workers’ compensation) income for all adult family members (including unmarried partners), converted to 2009 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers Research Series (CPI-U-RS).9

We provide an (somewhat rudimentary) analysis of time use, as a function of parental employment status. To provide a contemporary portrait of time use, we use the 2003–2008 waves of the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), which provides nationally representative data for U.S. adults (15 and older) from 24-hour time use diaries collected from one randomly selected household member drawn from CPS respondents. This sampling procedure allows the ATUS to be matched to labor market data from the monthly CPS, with a 2- to 5-month lag. The ATUS sample is drawn from households who have completed their eighth and final month of interviews for the CPS. The restriction to one household member limits the analysis of joint time use choices within families.10 This portion of the analysis focuses on primary childcare, defined as time spent caring for and helping children in the household, as well as activities related to their education and health. Daily minutes are converted into weekly hours by dividing total minutes by 60 and then multiplying by 7. We also examine other categories of time use (e.g., paid work, secondary childcare, sleep, housework, eating, grooming, and free time) but do not emphasize these findings. Families are classified into the employment categories using information about usual weekly work hours for the respondent and spouse (if any) obtained from the monthly CPS. We use information about work hours from the CPS file so that we can examine both spouses’ work patterns (because the ATUS respondent file only includes work information on the respondent, not his or her spouse). However, if the respondent’s work status changed between the CPS and the ATUS, we use ATUS-reported work hours. Full-year versus part-year employment is not distinguished here because the required information is unavailable in the monthly CPS, and it is not identified in the 1975–1976 time diary data discussed next.

To provide information on secular changes in primary childcare, conditioning on parental employment status, we use information from the 1975–1976 Time Use in Economic and Social Accounts data, a representative sample of 2,406 adults interviewed October–November 1975. Families were reinterviewed three more times in 1976, but we analyze only the first wave of the 1975 data to maintain comparability with the ATUS in which respondents were interviewed only one time. The 24-hour time diaries also indicate work status and earnings as well as demographic characteristics, such as marital status, education, and age. We categorize types of time use in the 1975 data using adapted versions of STATA programs from Aguiar and Hurst (2007). Unmarried partners are not identified, so we examine children from only single-mother and married-couple families in this portion of the analysis.11 Also, the small number of single-mother households implies that the related estimates are imprecise, so our analysis of secular changes in time use primarily focuses on married-couple families.

Finally, we use data from the Work Schedules and Work at Home Supplement to the May 2004 CPS to investigate how often dual-earner families coordinate work schedules (in the week prior to the survey). Specifically, we distinguish families in which both parents work only daytime hours (between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m.) versus those in which at least one parent works outside daytime hours.12 For the latter group, we further examine the reason the parent worked a nonstandard shift, distinguishing (for ease of exposition) between family/personal reasons (“better arrangements for family or childcare” or “personal preference”) and all other reasons (“better pay,” “could not get any other job,” “nature of the job,” and “other reasons”). Although these data cannot tell us the extent to which parents are providing childcare, working non-daytime hours for family/personal reasons seems most likely to indicate the possibility that parents are engaged in tag-team parenting (in which parents select different work schedules to cover childcare). The unit of analysis is again the child and, as with the ATUS, we divide final CPS May Supplement weights by the number of children in the family so as not to overcount children in large families. We also adjust the standard errors to take account of the clustering of children within families.

Trends in Parental Employment

The increased difficulty that families face in balancing the competing needs of work and home is reflected by dramatic changes in patterns of parental employment over the last four decades. We show this by documenting trends in employment and work hours between 1967 and 2009, using the March CPS data, from the perspective of children. The analysis is primarily descriptive, but we also examine the contributions of changes in family structure and in employment patterns within family structures in accounting for the overall trends. Our results are summarized in Figs. 1 and 2, with additional details provided in Table 1. In the figures, shaded vertical bars show periods of economic recession as defined by the NBER. Unless otherwise noted, all statistics are weighted but are not otherwise adjusted.

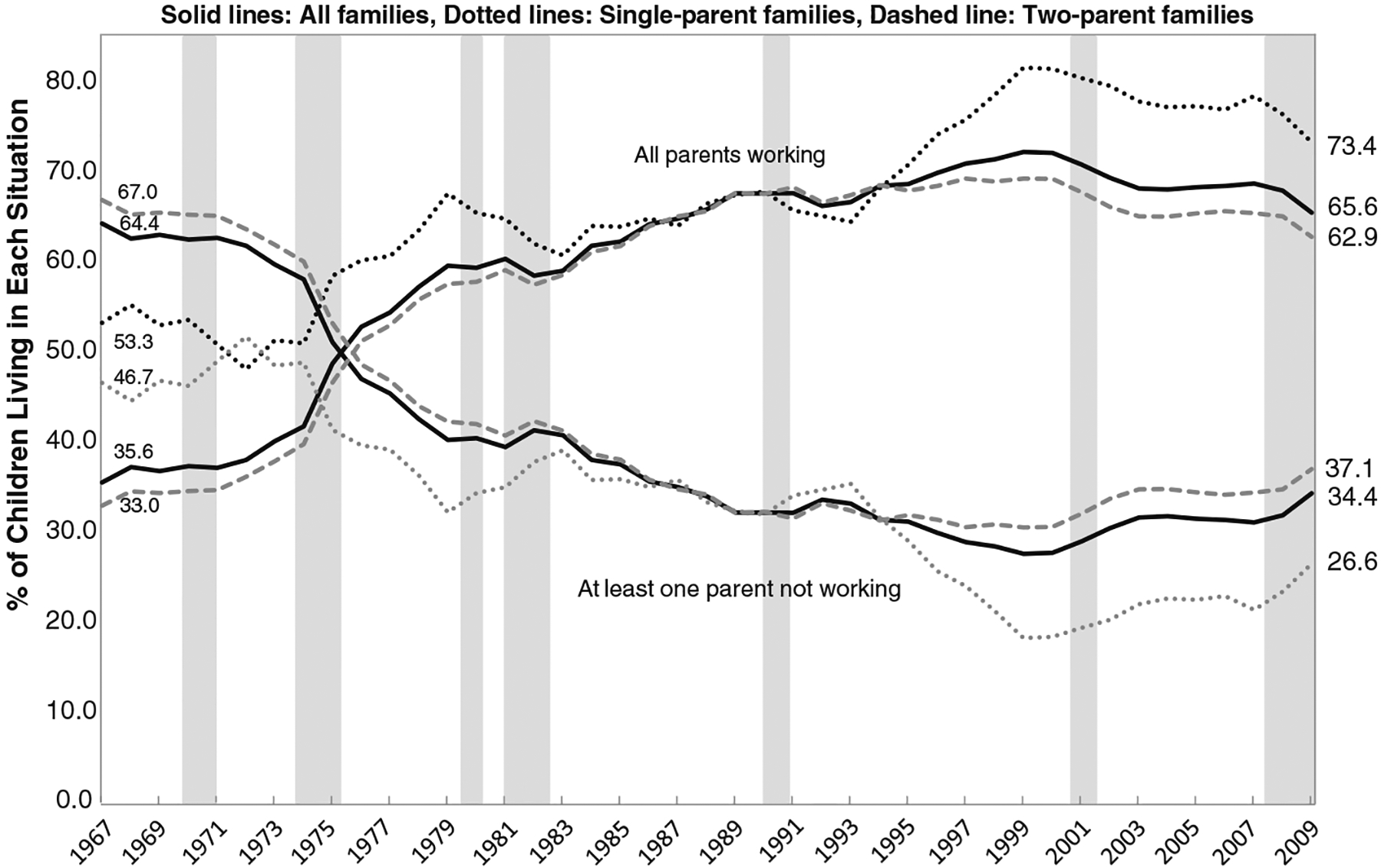

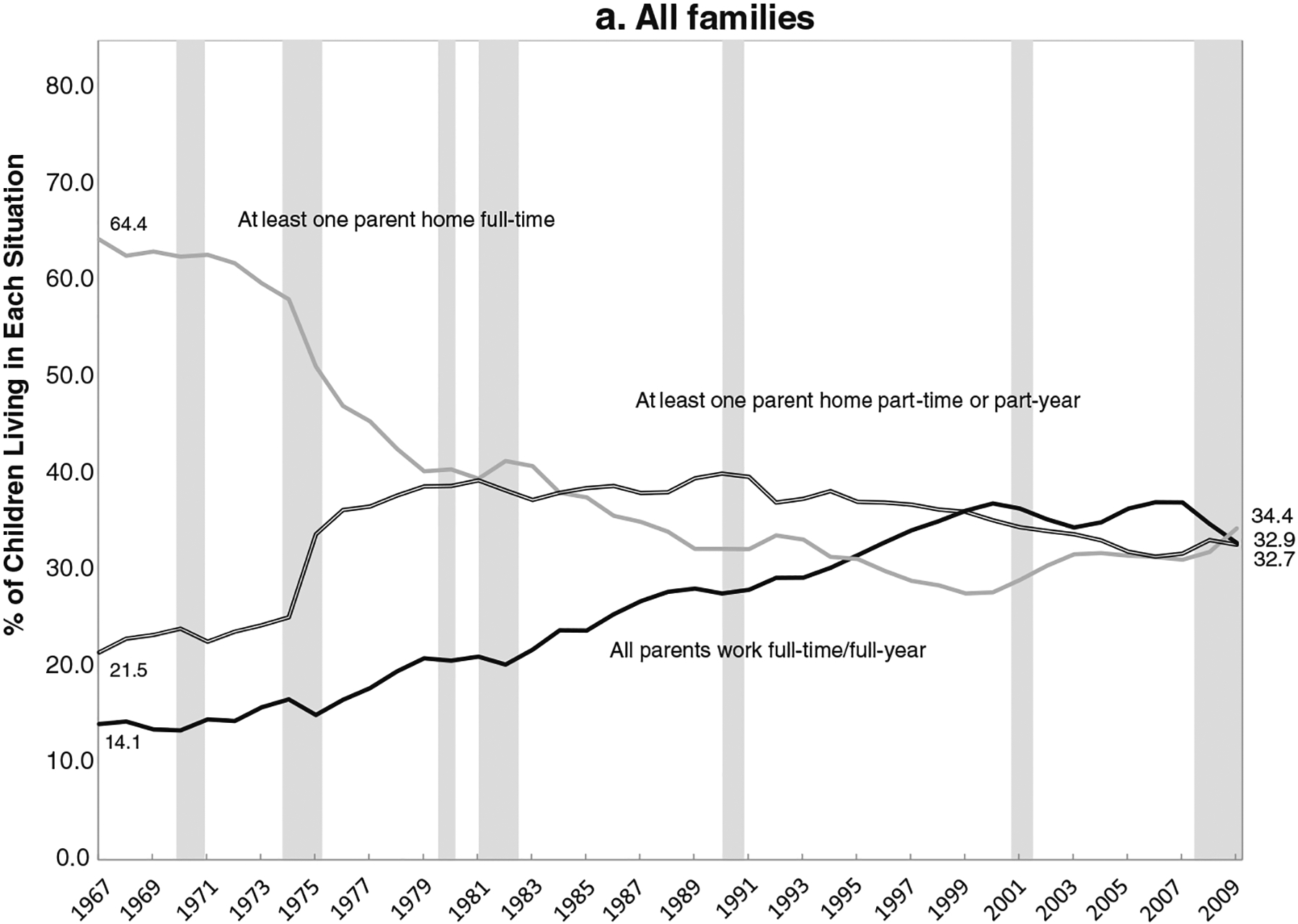

Fig. 1.

Trends in parental employment patterns, 1967–2009. Shaded bars are recessions as defined by the NBER. Source: March Current Population Survey, 1967–2009

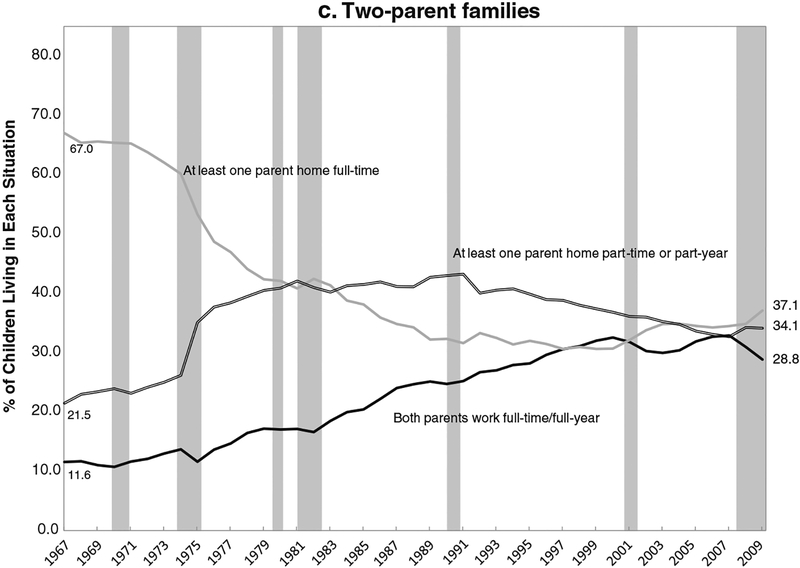

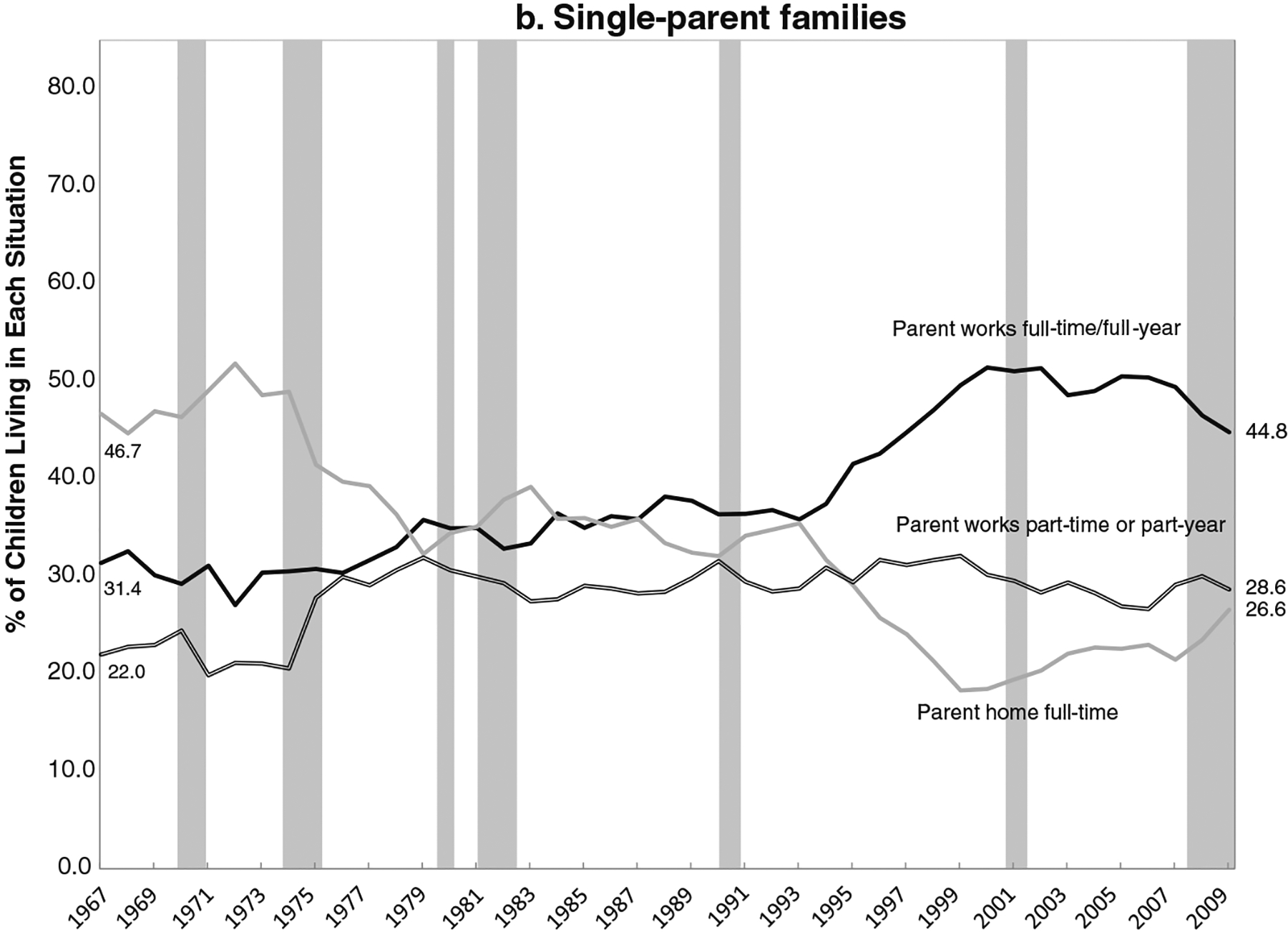

Fig. 2.

Trends in detailed parental employment patterns by family structure, 1967–2009. Shaded bars are recessions as defined by the NBER. Source: March Current Population Survey, 1967–2009

Table 1.

Trends in parental availability in selected years (percentages)

| All Parents Work Full-Time, Full-Year | A Parent Is Home Part-Time or Part-Year | A Parent Is Home Full-Time, Full-Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | 1989 | 2009 | 1969 | 1989 | 2009 | 1969 | 1989 | 2009 | |

| Overall | |||||||||

| Unadjusted | 14 | 28 | 33 | 23 | 40 | 33 | 63 | 32 | 34 |

| Regression-adjusted | 15 | 28 | 34 | 27 | 34 | 40 | 58 | 38 | 25 |

| Age of Child | |||||||||

| 0–4 years | 7 | 21 | 26 | 20 | 40 | 34 | 72 | 38 | 40 |

| 5–11 years | 12 | 27 | 33 | 23 | 41 | 33 | 64 | 32 | 35 |

| 12–17 years | 20 | 36 | 39 | 25 | 37 | 32 | 55 | 26 | 29 |

| Maternal Education | |||||||||

| Less than high school | 11 | 14 | 16 | 21 | 31 | 27 | 68 | 55 | 58 |

| High school | 14 | 28 | 30 | 25 | 42 | 32 | 61 | 31 | 38 |

| Some college | 14 | 30 | 34 | 24 | 43 | 36 | 62 | 27 | 30 |

| Bachelors degree+ | 17 | 34 | 40 | 23 | 42 | 34 | 60 | 24 | 26 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 12 | 26 | 31 | 23 | 42 | 34 | 65 | 32 | 35 |

| Black | 19 | 31 | 38 | 28 | 33 | 28 | 53 | 36 | 34 |

| Other | 13 | 27 | 33 | 19 | 31 | 29 | 68 | 42 | 38 |

Notes: Observations are weighted so as to be nationally representative. No other adjustments are made unless otherwise noted.

Source: March Current Population Survey, 1967–2009.

Regression-adjusted results, presented in Table 1, control for family structure, maternal education, child age, race/ethnicity, number of preschool, school age, older children in the family, annual national unemployment rates, and a vector of state dummy variables, all of which are factors that may affect parental employment decisions. Regression adjustments generally do not much affect the results, and so they are not shown in the figures. The most important change is that controlling for unemployment rates reduces the procyclical variation in employment and work hours. This helps to explain why the regression-adjusted employment rates in 2009 (a recession year), shown in Table 1, are considerably below the unadjusted rates.

Five main findings deserve mention. First, whereas approximately two-thirds of children were in homes with a nonworking parent in the late 1960s, only around one-third were at the beginning of the twenty-first century (Fig. 1). By 2009, there were three distinct and approximately equally sized groups of children: those with at least one parent home full-time and full-year, those with all parents working full-time and full-year, and those whose parents had intermediate work arrangements (Fig. 2a).

Second, the secular reduction in the availability of nonworking parents occurred for virtually all groups of children but with somewhat different starting points and magnitudes of the changes. Children raised in lone-parent families have always been less likely to have a nonworking parent, but the trend decreases have been larger in absolute (albeit similar in percentage) terms for two-parent households: the shares of children with a parent home full-time fell from 47 % to 27 % for the former group and from 67 % to 37 % for the latter (Fig. 2b and c).

Third, young children are most likely to have a nonworking parent in all the periods analyzed, but the secular increase in parental employment is largest for them (in percentage or absolute terms): 72 % of children under the age of 5 had a parent home full-time and full-year in 1969 compared with just 40 % in 2009; the comparable figures for 12- to 17-year-olds were 55 % and 29 % (Table 1). Over the same period, the share of 0- to 4-year-olds with all parents employed full-time and full-year grew from 7 % to 26 % versus an increase from 20 % to 39 % for 12- to 17-year-olds.

Fourth, Table 1 also illustrates dramatically different trends by maternal education. In 1969, for example, children in families in which the mother had not finished high school were just 8 percentage points more likely than their counterparts with college graduate mothers to have a nonworking parent (68 % versus 60 %), but the disparity increased to 32 percentage points in 2009 (58 % versus 26 %). During the same time period, educational attainment increased rapidly (see Table 7), reducing the share of children in families in which the mother had not finished high school from 38 % to 14 %, while the share with college graduate mothers increased from 7 % to 30 %. There has recently been much discussion about whether highly educated mothers have been “opting out” of work (see, e.g., Boushey 2008; Cotter et al. 2010; Stone 2007), and there is some hint in our data of an uptick in parents at home during the last decade that we analyze. However, these statistics illustrate that any such effects are small compared with the long-term trend increase in the labor supply of highly educated mothers. There are also racial disparities in the secular changes, although the pattern is toward convergence in this case, with the parental employment rates of white children catching up to those of their black counterparts.

Fifth, although the overall trends are similar (at least in direction) for all groups of children, the timing of the changes is not (see Fig. 1 and Table 8 in the Appendix). Notably, for children in two-parent families, most of the decline in the availability of a nonworking parent occurred between 1967 and 1989 (falling from 67 % to 32 %), with little change during the last decade of the 1990s and a slight increase toward the end of the sample period (to 37 % in 2009). This last effect probably combines a modest amount of “opting out” behavior, observed during the first few years of the twenty-first century, along with recession-related employment reductions during the last sample years. Conversely, for children in lone-parent families, the share with nonemployed parents fell sharply between 1972 and 1979 (from 52 % to 32 %), was relatively stable through 1993, and then declined precipitously during the next six years (from 35 % to 18 %) before rising toward the end of the analysis period. Although it is beyond the scope of this analysis to precisely identify sources of these trends as well as differential impacts across family structures, much of the shift during the 1970s seems likely to reflect dramatic overall growth in female labor force participation rates, whereas the increase in the employment of single mothers during the middle to late 1990s coincides with the work incentives associated with welfare reform and changes in the Earned Income Tax Credit, combined with a period of robust economic growth. Blank (2002) and Grogger and Karoly (2005) provided evidence that welfare reform and a strong economy increased the employment of single mothers, while Meyer and Rosenbaum (2001) demonstrated positive effects of the EITC reforms.

Our child-based analysis examines parental employment trends from the view-point of the typical child. Table 2 shows that the general trend toward reduced availability of a parent at home holds using either a child-based or family-based analysis but that the secular changes faced by the average child are understated when using the latter approach. For example, the share of single-parent families with a nonemployed parent fell from 42 % to 28 % between 1969 and 2009, but the proportion of children in this type of family decreased more: from 47 % to 27 %. We do not interpret this as indicating that our analysis method is superior for all related issues of interest. For instance, a family-based analysis may be preferred when considering whether parents feel more constrained now than in the past. However, a child-based investigation does seem more relevant when considering how these changes affect the typical child.

Table 2.

Trends in parental availability, child versus family-based analysis for selected years (percentages)

| Child-Based Analysis | Family-Based Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | 1989 | 2009 | 1969 | 1989 | 2009 | |

| Overall | ||||||

| All parents work full-time, full-year | 14 | 28 | 33 | 16 | 31 | 35 |

| A parent is home full-time, full-year | 63 | 32 | 34 | 58 | 30 | 33 |

| Single-Parent Families | ||||||

| Parent works full-time, full-year | 30 | 38 | 45 | 34 | 43 | 46 |

| Parent is home full-time, full-year | 47 | 32 | 27 | 42 | 30 | 28 |

| Two-Parent Families | ||||||

| Both parents work full-time, full-year | 11 | 25 | 29 | 14 | 28 | 31 |

| A parent is home full-time, full-year | 66 | 32 | 37 | 61 | 30 | 35 |

Note: Observations are weighted so as to be nationally representative.

Source: March Current Population Survey, 1967–2009.

Although the increase in parental employment rates could theoretically be offset by reductions in work hours for those who are in jobs, this has not occurred in practice. Total annual parental work hours increased by 16 % (from 2,663 to 3,092 hours) between 1967 and 2009 for the average child in a two-parent family and by 35 % (938 to 1,262 hours) for the average child in a single-parent family (Fig. 3). As mentioned earlier, the hours growth is particularly concentrated among children with highly educated parents, consistent with other research showing growing disparities in hours worked (see, e.g., Bianchi 2011; Jacobs and Gerson 2004).13

Fig. 3.

Average annual parental work hours, 1967–2009. Shaded bars are recessions as defined by the NBER. Source: March Current Population Survey, 1967–2009

Decomposing Parental Employment Trends

We next examine the extent to which secular increases in parental employment reflect changes in family structure versus changes in patterns of work within family structures. Consider the following:

| (1) |

where Yj is the share of children with a nonworking parent in year j, for j equal to either 1967 or 2009; β is the share in single-parent families; 1 − β is the share in two-parent families; γ is the share of single-parent families with a nonworking parent; and δ is the share of two-parent families with a nonworking parent.

The share of children who would have a nonworking parent in 2009 if family structure had remained at 1967 values can then be expressed as

| (2) |

and the share with a nonworking parent if employment patterns had remained constant within family structures would be

| (3) |

These counterfactuals can be compared with actual 1967 and 2009 values to indicate the role of changes in family structure or employment patterns within family structures in accounting for the total change in parental employment trends from 1967 to 2009.

Results of this exercise, summarized in Table 3, show that almost none of the reduction in children in households with a nonworking parent resulted from changes in family structure.14 Specifically, whereas the actual share of children with a nonworking parent declined by 30.0 percentage points (from 64.4 % to 34.4 %) between 1967 and 2009, the increase in single parent families accounted for just 1.3 percentage points of this drop, with a 27.4 point reduction being due to changes in work patterns within family structures (5.1 points for single-parent and 22.2 points for two-parent families). The remaining 1.3 percentage point drop represents the interacted effects of changes in family structure and of work patterns within family structures. Thus, changes in work patterns among two-parent families (specifically because of the increase in labor force participation among partnered women) represent the largest source of the decrease in the share of children with a stay-at-home parent.

Table 3.

Decomposition of effect of changing family structure on likelihood of having a nonworking parent

| Share of Children With a Nonworking Parent (%) | % Change | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Value, 1967 (Y1967) | 64.4 | |

| Actual Value, 2009 (Y2009) | 34.4 | |

| Predicted Value in 2009 | 30.0 | |

| Holding constant family structures (Ya) | 35.7 | 1.3 |

| Holding constant work patterns (Yb) | 61.8 | 27.4 |

| Holding constant single-parent work patterns | 39.5 | 5.1 |

| Holding constant two-parent work patterns | 56.6 | 22.2 |

Note: Values may not sum exactly because of rounding.

Source: March Current Population Survey, 1967–2009.

Parental Employment and Family Income

The secular increases in parental employment documented herein presumably reflect trade-offs that parents are making between available nonmarket time and the family income that market work provides. This section examines whether parents are being pushed into the labor force—by which we mean that they are increasingly finding it necessary to work to avoid income declines relative to similar households in past decades—or whether they are being pulled into jobs by the prospect of increased family incomes, again compared with previous cohorts.

Family incomes (in 2009 U.S. dollars) have grown much more markedly for children in two-parent households—from $57,854 during 1967–1976 to $93,348 during 2000–2009—than for those in lone-parent households (for which they increased from $23,949 to $29,157).15 This provides an initial suggestion that the influences of push and pull factors differ depending on family status, but educational attainment, work patterns, and racial composition have changed over time and across groups, requiring a more comprehensive analysis.

To isolate changes in the returns to work, we predict what the incomes of families in alternative employment circumstances and time periods would be, by using standard decomposition procedures to allow for different assumptions about the demographic makeup of the specified groups and the returns to these characteristics.

As a first step, we separately estimated the natural log of annual family incomes for four subgroups of families as

| (4) |

where Yjt is the income of family type j at time t, j distinguishes between single-parent versus two-parent families and those with a parent home full-time versus those in which all parents work full-time and full-year, and t alternatively indicates 1967–1976 or 2000–2009. In this analysis, we omit families in which a parent works part-time to focus on the most sharply contrasting categories. X includes controls for parent’s age (and age squared), education, race/ethnicity, and the number and ages of children in the family. We retransform predicted log incomes to levels by exponentiating Eq. (4) and adjusting for a “smearing” factor, which is the expected value of the exponentiated error term.16 Finally, we construct counterfactual estimates by calculating predicted incomes after assigning the characteristics (Xs) to their average values in the other period (1967–1976 during 2000–2009 and vice versa) and, similarly, by assuming that the returns (%s) take the earlier or later period values.

As shown in Table 4, average family incomes for children with a nonworking parent fell by 46 % (from $14,651 to $7,958) for single-parent families but rose 21 % (from $47,629 to $57,765) for two-parent families. Conditional on all parents working full-time/full-year, family income rose 16 % (from $31,798 to $36,751) for children in single-parent households but by 44 % (from $69,344 to $99,886) for those with two parents present.17

Table 4.

Actual and predicted annual family income (2009$) by family structure, 1967–1976 and 2000–2009

| Single-Parent Families | Two-Parent Families | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual or Predicted Average Income |

A Parent Is Home Full-Time, Full-Year |

Parent Works Full-Time, Full-Year | A Parent Is Home Full-Time, Full-Year |

Both Parents Work Full-Time, Full-Year |

| Actual Income, 1967–1976 ($) | 14,651 | 31,798 | 47,629 | 69,344 |

| Actual Income, 2000–2009 ($) | 7,958 | 36,751 | 57,765 | 99,886 |

| Predicted Income ($) | ||||

| 1967–1976 characteristics, 2000–2009 returns |

9,487 | 30,802 | 42,899 | 78,083 |

| 2000–2009 c7haracteristics, 1967–1976 returns |

12,730 | 35,319 | 55,517 | 80,451 |

| Change in Income (1967–1978 to 2000–2009) (%) | ||||

| Actual | −45.7 | 15.6 | 21.3 | 44.0 |

| At 1967–1976 characteristics | −35.2 | −3.1 | −9.9 | 12.6 |

| At 2000–2009 characteristics | −37.4 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 24.2 |

Source: March Current Population Survey, 1967–2009.

Table 4 provides evidence of striking differences in income patterns across family structures, whether the changes are evaluated holding characteristics constant at 1967–1976 or 2000–2009 values. Family incomes for children in single-parent nonworking families declined by 35 % or more, holding demographic characteristics constant, whereas those for children with employed lone-parents remained approximately constant (falling by 3 % or rising by 4 %, depending on the comparison method). This suggests that single parents were being pushed into the labor force to avoid the large secular decline in incomes that would have otherwise occurred.

The picture is different for children in two-parent households, for which family incomes were predicted to either fall or rise slightly (by –10 % and 4 %) if there was a nonemployed adult but to have increased fairly dramatically (by 13 % to 24 %) if both parents worked full-time and full-year. The precise results are more dependent on the choice of base period characteristics (than for lone-parent families) but suggest that, on average, such adults are being pulled into jobs by the attractive income opportunities that work now provides. The experiences of two-parent families, however, are likely to evidence a good deal of heterogeneity, with families with high-educated earners more likely to have been pulled into the labor market, and those with low-educated earners experiencing more push (and with families in the middle seeing their incomes squeezed) (see, e.g., Bianchi 2011).

It therefore seems likely that children in single-parent households have, on average, become worse off in recent years—their parents are working more to keep family incomes approximately constant. The situation is less clear in two-parent family households, for which higher incomes seem likely to have at least partially offset the reduced availability of parental nonmarket time, at least on average, although likely with considerable variability as noted earlier.

Parental Time With Children

Fewer children now live in households with a nonworking parent than in the past, and having all parents in the family work full-time and full-year is increasingly common (although with a modest reversal of these trends over the last decade). While the lives of families have probably become more hurried and stressed, the time parents spend caring for children has not necessarily fallen because there are numerous ways in which time can be reallocated. We explore these issues next, comparing time use in 1975 and 2003–2008, the earliest and latest years of our analysis period for which comparable data are available. As with the rest of our investigation, we carry out these estimates from the perspective of the child (rather than the family). Several limitations deserve mention. First, we examine only two time periods, constraining our ability to comment comprehensively on long-term trends. Second, the sample for 1975 is small, reducing the precision of these estimates. This restriction is particularly important for single-parent households and, as a consequence, our analysis of this group is quite limited. Third, we focus on primary childcare only because secondary childcare (i.e., total time with children) is harder to define and data on it from the 2003–2008 ATUS was not collected in a manner consistent with the 1975 survey (Allard et al. 2007). Finally, we cannot undertake a careful analysis of joint decision-making among two-parent households because time use information for 2003–2008 is obtained for only one adult in the household. Some examination of this issue is provided, however, when we consider the potential coordination of work schedules.

Our time use analysis yields three main findings, which are apparent in both unadjusted and regression-adjusted estimates (both shown in Table 5). First, consistent with the prior research (reviewed earlier), we find that employed mothers spend significantly less time in primary childcare than their nonemployed counterparts.18 Second, also consistent with prior research, both working and nonworking parents spent more time with children during 2003–2008 than did their 1975 counterparts (although imprecise estimates for single mothers do not allow us to reject the null hypothesis of no secular change for them). Interestingly, employed married mothers during 2003–2008 spent almost as many hours in primary childcare as did their nonworking peers in 1975, and employed fathers spent more time caring for children in the later period, whatever their employment status.19 Conversely, primary childcare hours, conditional on employment status, have changed less for single mothers, suggesting that the substantial increases in their labor supply may have reduced time with children (although again, the small sample size for 1975 limits our ability to test for such trends). Third, parental time in primary childcare decreases with child age and has not changed as much over the four decades for older children as for those of preschool age. For instance, married mothers in households in which both parents work and with a child younger than 5 increased their primary childcare time from 9 to 14 hours per week between 1975 and 2003–2008, compared with an increase from 4 to 6 hours if their children were 5 or older.20

Table 5.

Hours spent by parents in primary childcare

| A Parent is Home Full-Time | All Parents Work Full-Time | Unadjusted Difference | Regression-Adjusted Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Children | ||||

| Married mothers | ||||

| 1975 | 10.6 | 5.3 | 5.2 *** | 4.9 *** |

| (N = 693, 266) | (0.7) | (0.6) | ||

| 2003–2008 | 15.9 | 8.2 | 7.7 *** | 8.0 *** |

| (N = 18,437, 16,120) | (0.4) | (0.2) | ||

| Married fathers | ||||

| 1975 | 2.6 | 3.2 | −0.7 | −0.7 |

| (N = 612, 249) | (0.3) | (0.9) | ||

| 2003–2008 | 6.2 | 5.3 | 0.9 ** | 1.3 ** |

| (N = 17,576, 15,721) | (0.2) | (0.2) | ||

| Single mothers | ||||

| 1975 | 10.6 | 5.7 | 5.0 * | 4.5 * |

| (N = 103, 69) | (1.9) | (1.3) | ||

| 2003–2008 | 12.1 | 6.9 | 5.1 *** | 5.7 *** |

| (N = 2,331, 4,540) | (0.5) | (0.2) | ||

| Children Under Age 5 | ||||

| Married mothers | ||||

| 1975 | 13.9 | 9.1 | 4.8** | 4.6 * |

| (N = 200, 52) | (1.2) | (1.3) | ||

| 2003–2008 | 22.7 | 14.2 | 8.5 *** | 8.7 *** |

| (N = 5,527, 3,445) | (0.6) | (0.5) | ||

| Married fathers | ||||

| 1975 | 3.6 | 6.0 | −2.5 | −1.6 |

| (N = 181, 53) | (0.6) | (2.6) | ||

| 2003–2008 | 8.4 | 9.8 | −1.3 | −0.3 |

| (N = 5,207, 3,355) | (0.4) | (0.6) | ||

| Children Age 5–17 | ||||

| Married mothers | ||||

| 1975 | 8.9 | 3.9 | 5.0 *** | 3.8 *** |

| (N = 493, 214) | (0.7) | (0.5) | ||

| 2003–2008 | 12.2 | 6.1 | 6.1 *** | 5.3 *** |

| (N = 12,910, 12,675) | (0.4) | (0.2) | ||

| Married fathers | ||||

| 1975 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | −0.8 |

| (N = 431, 196) | (0.3) | (0.5) | ||

| 2003–2008 | 4.9 | 3.8 | 1.1 *** | 1.2 * |

| (N = 12,369, 12,366) | (0.2) | (0.2) |

Notes: Numbers in parentheses are clustered standard errors. Regression-adjusted differences are obtained by regressing total hours in primary childcare per week on the mother’s (father’s) age, education, race/ethnicity, number of children in the family, and employment status.

Source: Time Use in Economic and Social Accounts 1975–1976 and American Time Use Survey, 2003–2008.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Finally, we investigate the possibility that two-parent families might engage in “tag-team” parenting, using data from the Work Schedules and Work at Home Supplement to the May 2004 CPS.21 Our analysis is preliminary because the supplement does not explicitly ask about coordination of employment within the household, nor does it provide information about whether parents are providing childcare. Instead, we examine the potential for such behavior by checking whether a parent works nonstandard hours (i.e., some of their employment occurs between 6 p.m. and 6 a.m.) as well as the reasons for doing so. Again, our analysis is child-based, and we provide results for all children as well as separate results for preschool-age and older children.

Our results, shown in Table 6, indicate that at least one parent works during non-daytime hours in about one-quarter of dual-earner families. When one of the parents is employed part-time, the nonstandard hours are worked for family/personal reasons almost half the time (12.4 % of 25.7 %), suggesting that the coordination of employment may be relatively common. Non-daytime hours occur with similar frequency when both parents work full-time, but in only about one-third (7.1 % of 23.1 %) of these cases are they for family/personal reasons. Consistent with prior findings (Presser 2003; Presser and Cox 1997), non-daytime shifts are more common among less-educated mothers, who are also more likely to report working them for family/personal reasons. This indicates that tag-team parenting may be important for a substantial minority of American children, especially those with less-educated parents. A caveat is that non-daytime employment in families with a college-educated mother who works part-time also occurs relatively frequently for family/personal reasons.

Table 6.

Work schedules for dual-earner parents (percentages)

| Work Schedule | Both Parents Work Full-Time | A Parent Is Home Part-Time |

|---|---|---|

| All Dual-Earner Parents | ||

| Both work daytime hours only | 76.9 | 74.4 |

| At least one parent works at non-daytime hours | 23.1 | 25.7 |

| For family/personal reasons | 7.1 | 12.4 |

| For other reasons | 16.0 | 13.3 |

| Maternal Education: Less Than High School | ||

| Both work daytime hours only | 65.5 | 67.8 |

| At least one parent works at non-daytime hours | 34.5 | 32.2 |

| For family/personal reasons | 15.5 | 14.5 |

| For other reasons | 19.0 | 17.8 |

| Maternal Education: High School Graduate | ||

| Both work daytime hours only | 74.4 | 74.1 |

| At least one parent works at non-daytime hours | 25.6 | 25.9 |

| For family/personal reasons | 7.9 | 12.3 |

| For other reasons | 17.7 | 13.6 |

| Maternal Education: Some College | ||

| Both work daytime hours only | 74.6 | 70.9 |

| At least one parent works at non-daytime hours | 25.4 | 29.1 |

| For family/personal reasons | 7.6 | 13.0 |

| For other reasons | 17.9 | 16.1 |

| Maternal Education: College Graduate | ||

| Both work daytime hours only | 83.4 | 78.5 |

| At least one parent works at non-daytime hours | 16.6 | 21.5 |

| For family/personal reasons | 4.3 | 11.5 |

| For other reasons | 12.3 | 9.9 |

Notes: Statistics are weighted to be nationally representative. Family/Personal reasons include “Better arrangements for family” or “Personal preference.” Other reasons include “Better pay,” “Could not get any other job,” “Nature of the job,” or others, such as allows time for school, and local transportation. Sample size is 20,021 for the full sample and 2,103, 5,202, 6,086, and 6,630 for less than high school, high school graduates, some college, and college graduates, respectively.

Source: Work Schedules and Work at Home Supplement to the 2004 May Current Population Survey.

Discussion

The lives of children have altered in fundamental ways during the past 40 years. One of the most important is the change in family arrangements. More children are raised in single-parent families, and regardless of whether they have one or two parents in the home, they are much less likely to have a nonworking parent. In 1967, the first year that we study, approximately two-thirds of children lived with a parent who did not engage in market employment. By 2009, the fraction was only around one-third, with an equal proportion in families in which all parents worked full-time and full-year. Although considerable attention has been paid recently to highly educated mothers opting out of the labor force, such effects are small relative to the longer-term trend toward higher maternal employment.

The implications of this enormous change for children are not entirely clear. Working parents have less time available for nonmarket activities and devote less time to childcare than their nonemployed counterparts. On the other hand, this has been at least partially offset by a secular increase in parental time devoted to primary childcare. Before being too sanguine about this result, we note that there is considerable heterogeneity across groups of children and reason to be concerned that the overall trends may have had negative effects on at least some of them.

Children with single-parents, for example, are much less likely to have a non-working parent now than in the past, and although primary childcare time has trended upward for both working and nonworking single mothers, the increase for those who are employed has been modest (from 5.7 to 6.9 hours per week). The average child in a single-mother family receives fewer hours of primary childcare from the mother than the average child in a two-parent family; and, of course, the shortfall is even greater if one adds in the childcare provided by fathers in two-parent families (which has been increasing over time). Nor has the extra employment increased family incomes for the single-parent group. Similarly, although employed mothers in two-parent families now spend about the same amount of time caring for young (0- to 4-year-old) children as their nonworking peers did in the 1970s, the same is not true for employed mothers of 5- to 17-year-olds. Moreover, time in primary childcare by two-parent families with a nonemployed parent has also increased, such that children with two working parents still receive less care time than their peers with a nonworking parent. And even when child time is protected, the lives of working parents are likely to have become more stressed and hurried (Galinksy 1999). On the other hand, for children in two-parent families, increased parental employment has been accompanied by substantial growth in family incomes as well as the other benefits that employment provides.s

Many questions remain unanswered. For instance, we do not know how the time crunch associated with more parental employment has affected the quality of time spent between parents and children. We provide evidence that roughly one-quarter of dual-earner families had at least one parent working a non-daytime schedule in 2004, lending credence to the possibility that some families engage in tag-team parenting. However, we have not investigated whether this has changed over time, and lacking data on childcare activities in such families, we do not have direct evidence on the extent to which nonstandard schedules are used for this purpose. Nor have we been able to examine the role of market work taking place at home; this is an important point for future research.

Although the overall pattern of increased parental employment holds for virtually all children, the implications are likely to be most pronounced for the youngest among them. Those of preschool age are still more likely than their older counterparts to have a parent at home, but the growth in working parents has been largest for them. We cannot say whether these age disparities are socially optimal, but it is noteworthy that parents with infants and toddlers are less likely to work in most other industrialized countries (partly because they generally have rights to lengthy periods of paid leave when their children are young) and that part-time work (particularly for mothers) when they do return is relatively common (Ruhm 2011).

Finally, changes in parental employment prompt and, in turn, respond to modifications of other institutional and cultural arrangements, the effects of which have not been examined here. Over the time period that we consider, parents and policymakers have placed increased emphasis on early childhood care and education and other supports for working families (Smolensky and Gootman 2003; Waldfogel 2006). Over the same period, attitudes toward fathers and their roles have been transformed (Coltrane 1996; Sayer et al. 2004). These associated changes likely reinforce, but also may compensate for, the striking changes in parental employment documented here.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) through R01HD047215 as well as R24HD058486. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD or the National Institutes of Health. We are also grateful for helpful comments from seminar participants at the Population Association of America Annual Meeting and the University of Virginia.

Appendix

Table 7.

Family demographics for selected years (percentages)

| All Children | Children in Single-Parent Families | Children in Two-Parent Families | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | 1989 | 2009 | 1969 | 1989 | 2009 | 1969 | 1989 | 2009 | |

| Family Structure | |||||||||

| Two-parent families | 87 | 76 | 74 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Married families | 87 | 73 | 69 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Unmarried cohabiting | 0 | 3 | 6 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Single-parent families | 13 | 24 | 26 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Age of Child | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| 0–4 years | 25 | 30 | 29 | 22 | 31 | 27 | 26 | 30 | 30 |

| 5–11 years | 42 | 40 | 39 | 39 | 38 | 38 | 42 | 40 | 39 |

| 12–17 years | 33 | 30 | 32 | 39 | 30 | 35 | 32 | 30 | 32 |

| Maternal Education | |||||||||

| Less than high school | 38 | 19 | 14 | 59 | 32 | 19 | 35 | 15 | 13 |

| High school | 44 | 40 | 26 | 32 | 38 | 33 | 46 | 40 | 24 |

| Some college | 10 | 24 | 30 | 7 | 22 | 34 | 11 | 25 | 28 |

| Bachelors degree+ | 7 | 17 | 30 | 3 | 8 | 14 | 8 | 20 | 35 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 84 | 81 | 78 | 59 | 63 | 64 | 88 | 87 | 82 |

| Black | 15 | 15 | 15 | 41 | 33 | 31 | 11 | 9 | 10 |

| Other | 1 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

Source: March Current Population Survey, 1967–2009.

Table 8.

Trends in work patterns, 1967–2009 (percentages)

| 1967 | 1973 | 1979 | 1985 | 1991 | 1997 | 2003 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At Least One Parent Not Working | ||||||||

| Overall | 64 | 60 | 40 | 38 | 32 | 29 | 32 | 34 |

| Single-parent families | 47 | 49 | 32 | 36 | 34 | 24 | 22 | 27 |

| Two-parent families | 67 | 62 | 42 | 38 | 32 | 31 | 35 | 37 |

| All Parents Working | ||||||||

| Overall | 36 | 40 | 60 | 62 | 68 | 71 | 68 | 66 |

| Single-parent families | 53 | 51 | 68 | 64 | 66 | 76 | 78 | 73 |

| Two-parent families | 33 | 38 | 58 | 62 | 68 | 69 | 65 | 63 |

Source: March Current Population Survey, 1967–2009.

Table 9.

Average hours per week in selected activities, by marital and employment status

| 1975 | 2003–2008 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Parent is Home Full-Time | All Parents Work Full-Time | A Parent is Home Full-Time | All Parents Work Full-Time | |

| Single Mothers | ||||

| Paid work | 0.9 (0.9) |

40.4 (6.8) |

0.3 (0.1) |

39.7 (0.7) |

| Primary childcare | 10.6 (1.9) |

5.7 (1.3) |

12.1 (0.5) |

6.9 (0.2) |

| Housework | 25.9 (2.8) |

14.6 (2.6) |

19.0 (0.6) |

12.3 (0.3) |

| Shopping/services | 5.2 (1.4) |

4.2 (0.8) |

6.8 (0.4) |

5.9 (0.2) |

| Sleep | 62.3 (2.3) |

59.9 (3.1) |

67.0 (0.8) |

58.3 (0.4) |

| Eating and grooming | 15.4 (2.0) |

14.4 (1.9) |

11.6 (0.4) |

13.3 (0.2) |

| Free time | 47.3 (3.9) |

26.5 (2.9) |

44.5 (0.9) |

27.3 (0.5) |

| N | 103 | 69 | 2,331 | 4,540 |

| Married Mothers | ||||

| Paid work | 3.7 (0.9) |

39.6 (3.0) |

5.2 (0.4) |

39.6 (0.7) |

| Primary childcare | 10.6 (0.7) |

5.3 (0.6) |

15.9 (0.4) |

8.2 (0.2) |

| Housework | 28.8 (1.2) |

17.6 (1.6) |

23.9 (0.4) |

14.3 (0.3) |

| Shopping/services | 7.6 (0.6) |

5.0 (0.8) |

8.3 (0.3) |

6.3 (0.2) |

| Sleep | 59.6 (0.8) |

54.6 (1.7) |

60.8 (0.3) |

57.2 (0.3) |

| Eating and grooming | 15.3 (0.7) |

19.1 (3.9) |

13.2 (0.2) |

13.7 (0.2) |

| Free time | 41.3 (1.3) |

26.3 (1.7) |

35.5 (0.5) |

24.8 (0.4) |

| N | 693 | 266 | 18,437 | 16,120 |

| Married Fathers | ||||

| Paid work | 44.1 (2.4) |

50.2 (3.7) |

39.2 (1.0) |

46.1 (0.8) |

| Primary childcare | 2.6 (0.3) |

3.2 (0.9) |

6.2 (0.2) |

5.3 (0.2) |

| Housework | 6.5 (0.8) |

5.8 (1.3) |

9.1 (0.4) |

10.0 (0.3) |

| Shopping/services | 3.9 (0.6) |

3.9 (0.8) |

4.9 (0.3) |

4.4 (0.2) |

| Sleep | 56.6 (1.0) |

53.8 (1.6) |

58.0 (0.4) |

56.0 (0.4) |

| Eating and grooming | 14.9 (0.6) |

17.8 (2.0) |

13.0 (0.2) |

12.7 (0.2) |

| Free time | 38.6 (1.9) |

32.3 (2.4) |

34.1 (0.7) |

30.3 (0.6) |

| N | 612 | 189 | 17,576 | 15,721 |

Note: Numbers in parentheses are clustered standard errors.

Source: Time Use in Economic and Social Accounts 1975–1976 and American Time Use Survey, 2003–2008.

Footnotes

For examples of such models, see Blau et al. (1996) or Ruhm (2004). For a broader introduction to the economics of the family, see Becker (1981).

Children are grouped into the category that represents the maximum amount of time they could be spending with their parents. For example, a child in a family with one parent home full-time and one parent home part-time would fall into the third category of “one or more parents home full-time and full-year.”

Sayer et al. (2004) found that the time spent by mothers in routine childcare declined between 1965 and 1975 and then rebounded between 1975 and 1998. Aguiar and Hurst (2007) uncovered a slight decrease in childcare between 1965 and 1993, followed by an increase between 1993 and 2003. Bianchi et al. (2006) provided evidence that time in childcare was relatively flat between 1965 and 1995 and then increased for both mothers and fathers from 1995 to 2000. Conversely, Ramey and Ramey (2010) indicated that childcare time declined from 1965 to 1995, increased dramatically through 2000–2003, and flattened out between 2000–2003 and 2008. The somewhat disparate results occur primarily because of differences in survey years examined and the small sample sizes in early surveys (which reduce precision of the estimated effects).

Incomes, work hours, and employment status refer to the preceding year (e.g., results in the 2010 March CPS are for 2009). For simplicity, we refer to the data year (i.e., 2009) throughout, not the calendar year (i.e., 2010).

Hispanic ethnicity was not collected by the CPS until 1971, so the only race categories examined are black, white, and other. However, in years when Hispanic ethnicity was available, we found no noticeable differences in our regression-adjusted results by including Hispanic ethnicity.

The March CPS records usual hours worked per week in the preceding year. The monthly CPS separately asks about hours on primary and secondary jobs but contains smaller samples and less detail on child and family characteristics. We experimented with merging the monthly and March CPS and found that work estimates from the latter were systematically an hour or two lower per week less than those from the former; however, this slight discrepancy did not differ over time or across demographic groups.

Prior to 1975, respondents were asked about actual hours worked last week, not usual weekly hours. However, they were also separately asked whether they worked full-time, part-time, or not at all in the previous year. For classification into an employment category, we used the latter variable for 1967–1974. For analyses that required annual hours worked, we imputed usual hours from actual hours, weeks per year worked, education, number of children, marital status, and age.

Prior to 1995, we identify unmarried partners based on census recommendations for persons of opposite sex sharing living quarters (adjusted POSSLQ), defined to include unrelated, unmarried, opposite-sex individuals living together in a household without other adults, other than related adult children (Casper et al. 1999). After 1995, the CPS contains an explicit category identifying unmarried partners. This change in definition creates a break in the data, with 1.5 million unmarried parent families in 1994 using the adjusted POSSLQ and 1.1 million in 1995 using the explicit “unmarried partner” designation. However, in a weighted sample of 35 million families annually, this difference was not noticeable in the results.

The CPI-U-RS is the price deflator used by the Census Bureau to adjust historical income statistics (Steward and Reed 1999), and the series begins in 1977. For earlier years, we created predicted CPI-U-RS series by regressing the CPI-U-RS on the CPI-U, for 1977–2009, and then backcasting values of the CPI-U-RS based on CPI-U changes between the specified year and 1977.

http://www.bls.gov/tus/ for further information on the ATUS. The ATUS sampled more than 20,000 individuals in 2003, its first year; it was reduced (for budgetary reasons) to between 12,000 and 14,000 in subsequent years but remains nationally representative.

General information on this survey is available online (http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACDA/studies/7580).

Both parents work non-daytime shifts in around approximately 2 % of families. Additional information on the supplement is available online (http://www.census.gov/apsd/techdoc/cps/cpsmay04.pdf).

In results not shown, we found that after controlling for family structure and parental employment status, there was virtually no change over the past 40 years in average or median weekly work hours.

We also conducted this decomposition in the reverse way—predicting 1967 values using 2009 data—and obtained consistent findings.

We use multiple years to reduce the effects of economic conditions in a single year. Both time periods experienced similar economic cycles, with 27 recession months occurring during 1967–1976 and 26 months occurring during 2000–2009.

When transforming logged values obtained from a regression back into nonlogged values, a smearing factor is necessary to correct for the nonnormal distribution of residuals (as would likely be the case with log-normally distributed income) (Duan 1983). Specifically, the expected value of the error term in the log-linear regressions does not equal 0, and the smearing factor adjusts for this by adding to the predicted values the expected value of the exponentiated error term.

Table 4 also displays counterfactual estimates that account for changes in family characteristics. These results do not change the overall story. For example, for children in single-parent families with a nonworking parent, if characteristics had remained at their 1967–1978 levels, 2000–2009 income would have averaged $9,487, which is a 35 % decline from the actual value in 1967–1978 ($14,651). Alternatively, actual incomes in 2000–2009 were 37 % lower than they would have been in 1967–1976 had family characteristics remained constant at 2000–2009 values ($7,958 vs. $12,730).

Employed mothers also spend less time doing housework and sleeping and have less free time than their nonemployed counterparts, and married fathers sleep less and have less free time when their wives work (see Table 9 in the Appendix details).

About 20 % of married families with one parent home full-time in 2003–2008 had “reversed” gender roles, with mothers working full-time and fathers not working; this represents approximately 7 % of all children in married families.

Age-specific results are not shown for single mothers because of the very small sample sizes in 1975, but the trends are consistent with those displayed on the table. We also do not show results disaggregated by parental education because of the small sample sizes in 1975, but prior research has found that hours in childcare have increased more over time for more-educated mothers than for their less-educated peers.

Work schedule supplements have been conducted in 1985, 1991, 1997, 2001, and 2004, but the survey questions have frequently changed, making it difficult to provide comparisons over time. An in-depth analysis that attempts to do so would be an interesting topic for future research.

Contributor Information

Liana Fox, School of Social Work, Columbia University, 1255 Amsterdam Ave, New York, NY 10027, USA.

Wen-Jui Han, Silver School of Social Work, New York University, New York, NY, USA.

Christopher Ruhm, Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Jane Waldfogel, School of Social Work, Columbia University, 1255 Amsterdam Ave, New York, NY 10027, USA.

References

- Aguiar M, & Hurst E (2007). Measuring trends in leisure: The allocation of time over five decades. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122, 969–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Allard MD, Bianchi S, Stewart J, White VR (2007). Comparing childcare measures in the ATUS and earlier time diary studies. Monthly Labor Review, May, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM (2000). Maternal employment and time with children: Dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography, 37, 401–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM (2011). Changing families, changing workplaces. The Future of Children, 21(2), 15–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, & Wight VR (2010). The long reach of the job: Employment and time for family life. In Christensen K & Schneider B (Eds.), Workplace flexibility: Realigning 20th-century jobs for a 21st-century workforce (pp. 17–42). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Robinson JP, & Milkie MA (2006). Changing rhythms of American family life. New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Blank R (2002). Evaluating welfare reform in the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 40, 1105–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Blau DM, & Currie J (2006). Pre-school, day care, and after school care: Who’s minding the kids? In Hanushek E & Welch F (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Education (pp. 1163–1278). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Blau DM, Guilkey DK, & Popkin BM (1996). Infant health and the labor supply of mothers. Journal of Human Resources, 31, 90–139. [Google Scholar]

- Boushey H (2008). “Opting out?” The effect of children on women’s employment in the United States. Feminist Economics, 14, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant WK, & Zick CD (1996). Are we investing less in the next generation? Historical trends in time spent caring for children. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 17, 365–391. [Google Scholar]

- Casper LM, Cohen PN, & Simmons T (1999). How does POSSLQ measure up? Historical estimates of cohabitation (Census Bureau Population Division Working Paper No. 36). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S (1996). Family man: Fatherhood, housework and gender equity. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cotter DA, Hermsen JM, & Vanneman R (2010). The end of the gender revolution? Gender role attitudes from 1977 to 2008. The American Journal of Sociology, 116, 1–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan N (1983). Smearing estimate: A nonparametric retransformation method. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 78, 605–610. [Google Scholar]

- Galinksy E (1999). Ask the children: What America’s children really think about working parents. New York: William Morrow & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier AH, Smeeding TM, & Furstenberg FF (2004). Are parents investing less time in children? Trends in selected industrialized countries. Population and Development Review, 30, 647–671. [Google Scholar]

- Grogger J, & Karoly LA (2005). Welfare reform: Effects of a decade of change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JA, & Gerson K (2004). The time divide: Work, family, and gender inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A (2003). Unequal childhoods: Class, race and family life. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A, & Weninger EB (2008). Time, work and family life: Reconceptualizing gendered time patterns through the case of children’s organized activities. Sociological Forum, 23, 419–454. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer BD, & Rosenbaum DT (2001). Welfare, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the labor supply of single mothers. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 1063–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Presser HB (2003). Working in a 24/7 economy: Challenges for American families. New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Presser HB, & Cox AG (1997). The work schedules of low-educated American women and welfare reform. Monthly Labor Review, April, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey G, & Ramey VA (2010). The rug rat race. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 129–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm CJ (2004). Parental employment and child cognitive development. Journal of Human Resources, 39, 155–192. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm CJ (2011). Policies to assist parents with young children. The Future of Children, 21(2), 37–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg JF, & Hofferth SL (2001). Changes in children’s time with parents: United States, 1981–1997. Demography, 38, 423–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer L, Bianchi S, & Robinson J (2004). Are parents investing less in children? Trends in mothers’ and fathers’ time with children. The American Journal of Sociology, 110, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Smolensky E, & Gootman JA (Eds.). (2003). Working families and growing kids: Caring for children and adolescents. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steward KJ, & Reed SB (1999). CPI research series using current methods, 1978–98. Monthly Labor Review, June, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Stone P (2007). Opting out? Why women really quit careers and head home. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J (2006). What children need. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zick CD, & Bryant WK (1996). A new look at parents’ time spent in child care: Primary and secondary time use. Social Science Research, 25, 260–280. [Google Scholar]