Abstract

Fungal corneal ulcers are an uncommon, yet challenging, cause of vision loss. In the United States, geographic location appears to dictate not only the incidence of fungal ulcers, but also the fungal genera most encountered. These patterns of infection can be linked to environmental factors and individual characteristics of fungal organisms. Successful management of fungal ulcers is dependent on an early diagnosis. New diagnostic modalities like confocal microscopy and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are being increasingly used to detect and identify infectious organisms. Several novel therapies, including crosslinking and light therapy, are currently being tested as alternatives to conventional antifungal medications. We explore the biology of Candida, Fusarium, and Aspergillus, the three most common genera of fungi causing corneal ulcers in the United States and discuss current treatment regimens for the management of fungal keratitis.

Keywords: fungal, yeast, keratitis, confocal microscopy, keratolysis

Introduction

Corneal ulcers are a common cause of ocular morbidity. Infectious ulcers require prompt diagnosis and treatment to minimize structural damage to the cornea and loss of vision. Severe infection can result in endophthalmitis or require corneal transplantation for restoration of vision. Although bacterial ulcers are more common than fungal, the latter present unique diagnostic challenges.1; 2; 3; 4 Empirical therapy of corneal ulcers often do not include coverage for fungal organisms. Fungal ulcers are more common in remote and rural areas.2; 3; 5; 6 Additionally, resistance to commonly used antifungal medications is high among certain genera of fungi.6; 7; 8 These factors may promote spread into deeper layers of the cornea or sclera. The eradication of fungal infections with topical and systemic medication likely diminishes with the greater burden of organisms.

A better understanding of fungal biology, including geographic distribution, life cycle in the eye, and molecular mechanisms of infection, is needed to improve diagnostic accuracy and management strategies. In this review, we describe each of these characteristics within the three genera of fungi that cause keratitis. Our interest in this topic arises from practicing in areas with high incidences of fungal keratitis, University of South Florida in Tampa and in Bogota, Colombia.

Life cycle of most common fungal pathogens

Unlike bacteria, fungi are eukaryotes organisms that are divided into two major groups: molds and yeasts. Molds are characterized by the production of hyphal filaments and spores. As these hyphal filaments coalesce, they form a mycelium.9 Molds are limited to aerobic environments, and often grow in colorful colony formations which can appear fuzzy or woolly. Unlike molds, yeasts remain unicellular and form long chains of cells known as pseudohyphae. They do not form spores. Yeasts tend to produce comparatively colorless or pearlescent colonies. A third category of fungus, dimorphic fungi are characterized by their ability to grow both as molds and as yeasts depending on environmental factors.9

Fusarium, the most common corneal pathogen, has been extensively studied in agriculture as it poses threats to the viability of many important crops.9 While the life cycle of Fusarium in nature has been well described, its life cycle in the cornea is not well known. In agricultural and in vitro settings, Fusarium can exist as a single celled micro- or macroconidia, which represents the spore phase used to spread.10 They can also exist as multicellular septate hyphae. In the human cornea, Fusarium grows in the stroma as multicellular hyphae and can also produce both micro and macroconidia. Like Fusarium, Aspergillus is also a representative of the molds and exists as a multi-cellular septate hypha as well as conidia.11

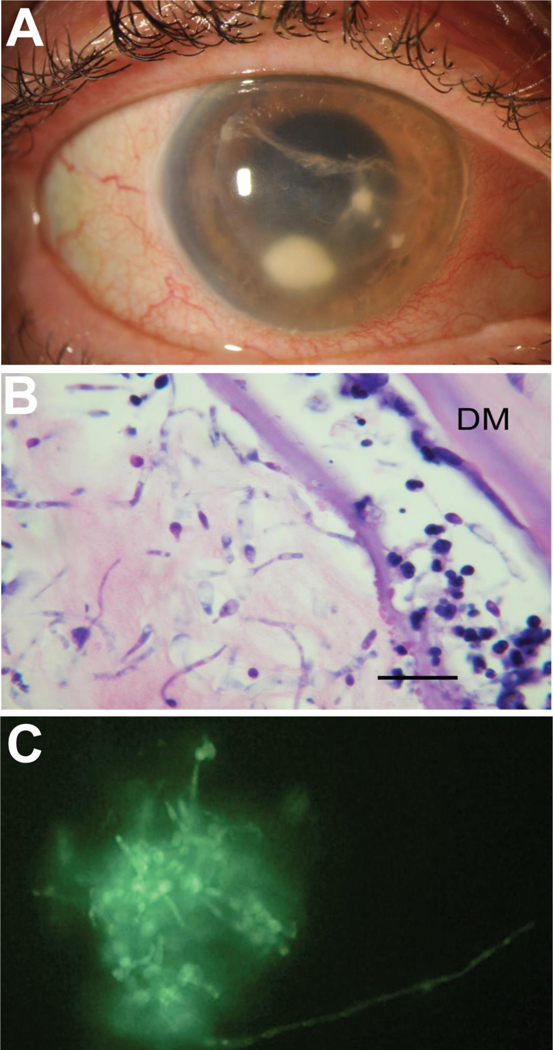

In contrast to Fusarium and Aspergillus, Candida is a dimorphic yeast.7, 12; 13 Depending on a variety of environmental factors, Candida can exist as a unicellular yeast or as a multicellular hyphal filament.13 Formation of filaments is imperative to the pathogenicity of Candida species.14 Knock-out of genes responsible for production of Candida filaments significantly limits its ability to infect.15; 16 In the majority of in vitro environments, Candida exists as a yeast cell that replicates via budding. These budding yeast cells can form pseudohyphae that takes on a more chain-like appearance that can begin to look like the more uniform and tubular hyphal form.12 (Figure 4B and C) Like Fusarium, Candida can also generate a chlamydospore in its pseudohyphal form to survive in harsh environmental conditions.12 While yeast, pseudohyphae, and hyphae can each survive in the human body, it appears that tissue invasion is principally carried out by filamentous forms.7; 12; 15; 16

Figure 4:

Appearance of Candida infection following endothelial keratoplasty. (A) External photograph of a post-operative endophthalmitis secondary to Candida albicans following DSAEK. (B) PAS stain shows candida invading the corneal stroma, and (C) KOH preparation with calcofluor white stain showing yeast cells, pseudohyhae and hyphae, present on the surface of removed IOL. Bar 75μm.

Geographical location

The most common predisposing factors to develop a fungal ulcer are a recent history of corneal injury, particularly microtrauma with contact lenses and with vegetative matter.2; 3; 4; 17; 18 The incidence of corneal ulcers caused by two major division of fungal pathogens, molds, namely Fusarium and Aspergillus, and yeasts, namely Candida, appears to be associated with latitude.19; 20 Molds tend to cause the majority of fungal ulcers in tropical and sub-tropical climates while Candida, a dimorphic yeast, is the more common etiology of fungal ulcers in temperate climates.20 This trend may be changing.21

Owing to fungi’s ability to decompose important agricultural crops, the impact of temperature and humidity on the growth patterns and pathogenicity of various Fusarium species has been well studied.10 While many species of Fusarium exist as ubiquitous saprophytic soil microbes and as endophytes in a commensal or symbiotic relationship with plant roots, some Fusarium strains become pathogenic to crops.10 Fusarium oxysporum, a cause of fungal keratitis and an important agricultural pathogen, grows more rapidly and produce more severe rot in vitro in warmer temperatures.22 Higher temperatures and humidity encourage growth of two other known causes of mycotic ulcers, Fusarium solani and Fusarium proliferatum.23 These studies suggest that Fusarium growth is enhanced in warmer soil with higher moisture content, characteristic of the tropical and subtropical climates in which Fusarium keratitis are commonly found.

Like other molds, Aspergillus is ubiquitous in nature and is frequently found in soil samples;11; 24however, while both Fusarium and Aspergillus molds produce conidia that are dispersed by wind, Aspergillus conidia are found in air samples in high concentrations relative to other fungi.24 As a result, Aspergillus is frequently inhaled and is considered a normal inhabitant of healthy lung tissue and mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract. In fact, based on indoor and outdoor air sampling, it is estimated that the average human inhales 100 Aspergillus conidia each day.24; 25 While Fusarium molds appear to be principally located in natural environments, Aspergillus molds have been discovered in a wide array of man-made environments as well, e.g., ventilation systems and ductwork. Aspergillus molds can often be isolated in moist, dark spaces such as home basements and in water sources, particularly those which allow for biofilm production such as in pipes.

Fusarium and, to a lesser extent, Aspergillus are generally considered environmental and soil fungi, Candida is much more widespread. Candida species have been found in a wide variety of environmental settings, and they are also a member of the normal human microbiome.12; 26 Candida is frequently found as a commensal organism living in the human gut, respiratory, and mucous membranes.12; 26 Because of the closer living relationship between humans and Candida, Candida infections tend to fall more into nosocomial or opportunistic categories in comparison to Fusarium. Prevalence of corneal ulcers caused by Candida is likewise higher in patients with preexisting ocular surface disease, recent ocular surface surgery, or topical immunosuppression.27; 28

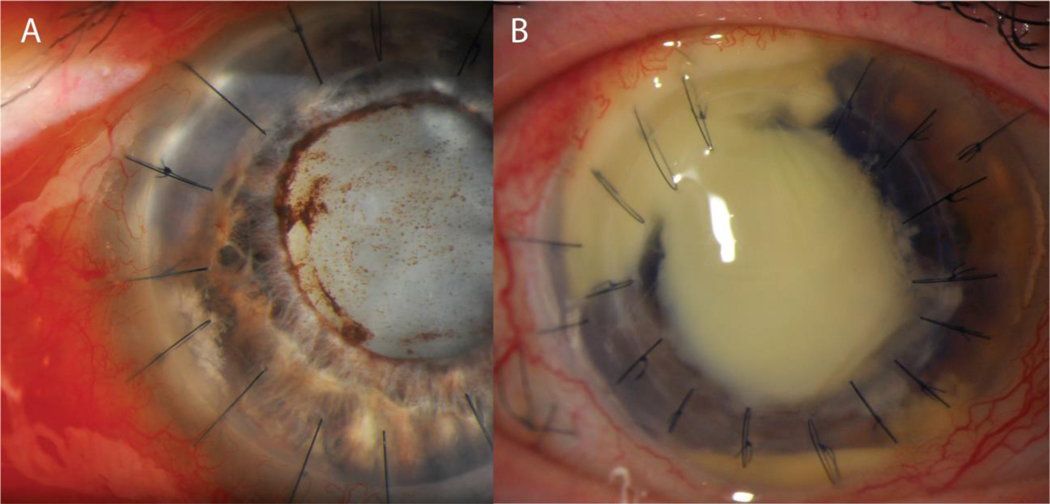

Fungal keratitis following corneal transplantation

Fungal organisms are occasionally detected in donor rim cultures from corneas used for transplantation. (Figures 3 and 4) The majority of positive culture results are ultimately identified as species of Candida.29; 30; 31; 32; 33 In large studies surveying positive culture results in a variety of keratoplasty procedures, 1.3 to 8.6% of transplanted tissue returned with a positive donor rim for fungi.29; 31; 32 Risk factors for increased incidence of positive fungal donor rim cultures still have yet to be identified. Within the Cornea Preservation Time Study, the only statistically significant variable that increased risk of positive fungal cultures was method of preparation of corneal graft tissue: 3.4% of surgeon prepared tissue returned with donor rim cultures positive for fungal organisms, compared with only 1.1% of eye bank prepared tissue. A previous report by the Eye Bank Association America advisory board, however, did not find tissue preparation by the surgeon to be a significant factor.34 Preservation media and time to utilization of corneal tissue have each been identified as potential variables that affect the incidence of infection after corneal transplantation. Interestingly, cold preservation increases the risk of candida contamination compared to corneas preserved in culture conditions.33 In a retrospective review of fungal keratitis or endophthalmitis following endothelial keratoplasty in several European centers, cold preservation was found to increase the risk of Candida contamination compared to corneas preserved in culture conditions.33 By contrast, a retrospective review of endophthalmitis following corneal transplantation in India, a low percentage of fungal organisms (15.8%) was identified compared to bacteria among culture positive infections. The investigators attributed the lower risk of fungal infection to shorter preservation time.35

Figure 3:

Candida infections in corneal transplants. (A) External photograph of an early infection in the graft-host interface of a PKP graft secondary to Candida albicans. (B) External photograph of a severe corneal ulcer secondary to Candida involving the graft tissue as well as the host limbus and sclera.

Positive culture results pose a unique challenge, as only a small minority of positive rim cultures will produce a clinical infection.30; 32; 33 In the Cornea Preservation Time Study, 5.4% of positive donor rim cultures went on to develop fungal keratitis or endophthalmitis.32 In a study produced by the Eye bank Association of America, only 1.4 cases per 10,000 corneal transplants were culture-proven fungal infections.34 Among these infections 55% progressed to develop endophthalmitis, while 45% developed keratitis. Within this study Candida species were the only fungi identified in either the donor or host cultures. Lamellar and endothelial keratoplasty had higher risk of developing a fungal infection with 0.052% of anterior lamellar keratoplasty, 0.022% of endothelial keratoplasty, and 0.012% of penetrating keratoplasty procedures developing infections. These infections were diagnosed at a mean of 49 days after surgery. Given the small percentage of infections that develop, the necessity of prophylaxis and the suggested prophylactic regimen continues to be debated. Despite increases in reported cases of fungal endophthalmitis and keratitis following transplant, the Eye Bank Association of America ultimately concluded that the relatively low incidence of these infections did not warrant addition of antifungal supplementation of donor storage media.34

In the event of fungal infection following lamellar transplantation, prompt initiation of local and systemic antifungal medication is warranted.36 Case reports have described successful treatment of fungal keratitis following keratoplasty with a combination of oral and intrastromal injection of antifungal medications.37; 38 For refractory cases, repeat injections and infusion of medication into the graft-host interface has also found to be effective in treating fungal infections. Intraocular extension of fungal organisms following corneal transplants has also been described in case reports.39 In these instances, aggressive surgical intervention is often warranted, including pars plana vitrectomy with intravitreal injection of antifungal medication and occasionally removal of intraocular implants.39

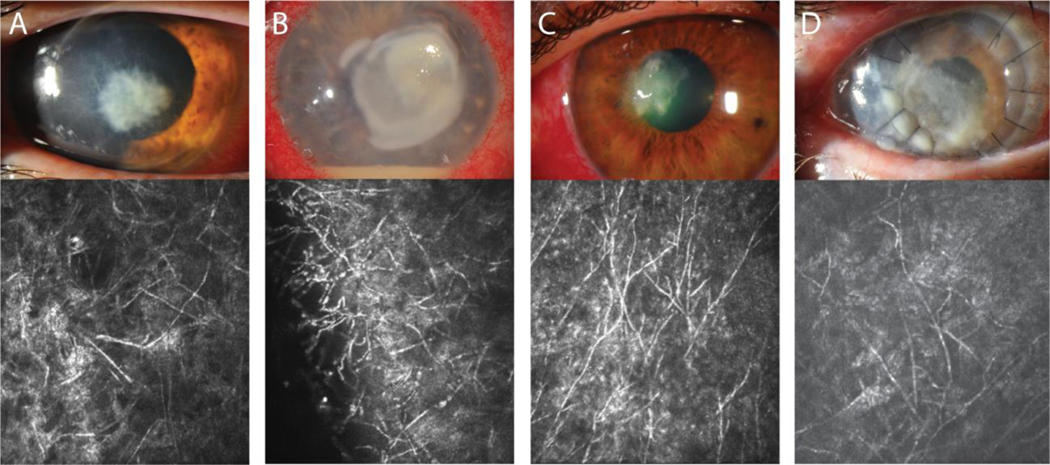

Identification of fungal pathogens

Although infectious ulcers share many similar attributes, there are some clinical features that can be used to distinguish etiologies although differentiating bacterial and fungal ulcers based on clinical examination alone is imprecise.40; 41 Classic fungal ulcers have feathery borders compared to the more distinct borders of bacterial ulcers. Satellite lesions and endothelial plaques have also been more frequently observed with fungi; however, outside of the area of cellular infiltration, the corneal stroma is often less edematous compared to bacterial ulcers. In contrast to the hypopyon that can form in bacterial infections, fungal ulceration may produce a more fibrinous hypopyon. Pigment in corneal ulceration may provide a clue as to fungal etiology. Although pigment production is more commonly seen among molds, yeasts are also capable of producing pigment.42; 43; 44; 45; 46 A heterogenous group of fungi referred to as dematiaceous that includes both yeasts and molds is the most common cause of pigmented ulcers owing to the production of melanin in their cell walls.47; 48 Pseudodematiaceous zygomycetes and pigmented non-dematiaceous fungus due to carotenoids can also appear brown.49 Among the various fungal organisms, molds have been reported to produce a firm, dry, and occasionally elevated infiltrate (Figure 1). Yeasts, unlike molds, tend to produce a smoother and occasionally gelatinous appearing infiltration (Figures 3 and 4). Early in the ulceration process, yeasts can also produce a raised, punctate, superficial infiltrates. This presentation is commonly found in Candida ulcers.

Figure 1:

Clinical appearance of typical fungal ulcer at slit lamp exam paired with confocal images in the same patient. The organism from (A) could not be cultured but was confirmed to be fungal on KOH preparation. Causative organisms were determined to be (B, C) Fusarium and (D) Exserohilum.

Cultures from corneal samples remains the gold standard for diagnosis of fungal pathogens. Many different methods for obtaining corneal specimens have been described. Additionally, multiple media preparations have been used for isolation and identification of specific fungi. Sabouraud dextrose agar is commonly used to isolate fungal pathogens. Aided by a lower pH and occasional addition of antibiotics, this agar can be tailored to selectively grow fungi over bacteria; however, most fungi causing corneal infections can grow on blood and chocolate agar. General-purpose liquid media such as brain-heart infusion and thioglycolate broth can also be used to isolate fungal pathogens; however, unless antibacterial agents are added, these broths are not selective for fungi.

Candida albicans, when grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates appears much like it does in corneal tissue: smooth, glossy, raised, cream-colored colonies that are clumped together in proximity. When grown on agar plates, Fusarium typically grow as flat, spreading, wooly colonies. Like mold growth in the cornea, the borders of these colonies can appear feathery as hyphal projections spread out from the central colony or mycelium. While many mold colonies initially appear white or grey-white in color, some species will go on to produce a variety of colors when grown in culture.

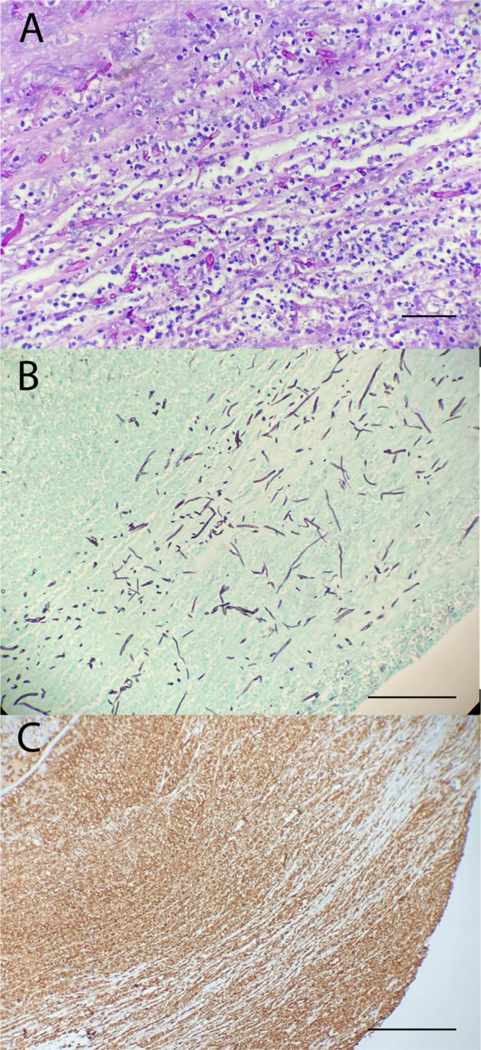

Identification of fungal cells in specimens obtained from corneal scraping and tissue often makes use of specific stains such as Grocott or Gomori methanmine silver (GMS) or periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains. (Figure 2A) Reagents of the GMS stain interact with polysaccharides in the cell wall of fungi, ultimately forming reducing aldehyde groups. These aldehyde groups reduce silver nitrate leading to precipitation of silver ions which make the cell wall appear black against a light blue or green background. (Figure 2B) PAS stains also stain polysaccharides in additional to mucin. This stain also involves the production of aldehyde groups which reach with Schiff reagent to produce a magenta color. Identification of fungi can still be difficult despite use of these stains as background noise can be generated from non-fungal staining such as basement membranes in PAS stains or melanin in GMS stains. Thus, both GMS and PAS stains are often coupled with hematoxylin and eosin to stain nuclei blue and cytoplasm pink.

Figure 2:

Pathology slides obtained from an excised cornea infected with Fusarium spp. (A) PAS and (B) GMS stains show the presence of acute branching hyphae and conidia consistent with Fusarium. (C) CD15 stain showing dense neutrophils infiltration, an immune typical of fungal infections, into the infected tissue. Bar 50μm.

Direct microscopy remains a preferred method for rapid, point-of-care diagnosis of fungal organisms in corneal scrapings. Fungal organisms can be seen on gram stain, although both positive and negative gram staining has been observed in molds and yeasts, which limits its utility; however, fungal organisms can be identified on Gram stain and differentiated from bacteria by differences in morphology. While the bacterial species that commonly cause ulcers are smaller in size, often 0.5–3.0 μm, Candida yeasts are typically larger (3–5 μm), display budding, and are intermingled with pseudohyphae. True hyphae formed by molds such as Aspergillus and Fusarium are 3–12 μm in diameter and can vary in length.50; 51 Corneal scrapings can be prepared in 10–20% potassium hydroxide (KOH) solutions to aid in identification of fungi. This strong alkali digests proteins, lipids, and cellular debris to enhance visualization of the chitin-rich fungal cell wall.52; 53; 54 Additional stains can be used with or without KOH preparation to further highlight fungal organisms such as calcofluor white, lactophenol blue, and trypan blue.52; 55; 56; 57

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing has been offered as a potential alternative to conventional detection methods. Capable of offering relatively rapid results, PCR appears to be an attractive option particularly for earlier infections with a lower fungal load. Zhao and coworkers reported a positive detection rate above 80% for fungal keratitis;58 however, PCR has yet to make inroads into clinical diagnosis of fungal keratitis. In PCR, panfungal primers can be used to identify the presence of fungal DNA in tissue samples while specific primers are needed to characterize the specific fungal agent. The presence of different genes that confer significant morbidity or prognosis can be assessed too.59; 60 Unfortunately, the ubiquitous nature of many fungi on the ocular surface could also lead to frequent false-positive results. Additionally, although PCR testing can detect the presence or absence of antibiotic resistance genes, the significance of this information in clinical context is unclear.

Another tool for fungal detection is in vivo confocal microscopy which is useful in imaging filamentous fungi in the cornea.61; 62 (Figure 1) Noninvasiveness and real-time identification are distinct advantages of confocal microscopy. While traditional scraping-based methods are limited to acquiring surface specimens, confocal microscopy can generate images from deeper layers of the cornea. However, success of confocal microscopy identification is dependent on the practitioner’s level of experience in interpreting the images, as well as patient cooperation.63; 64 Aside from simple detection of fungal specimens in corneal ulcers, confocal microscopy could also offer additional species or genus-specific identification based on cell morphology. Features specific to certain fungi that could be used to differentiate include length and width of hyphal or filamentous structures as well as number and angle of branches and sporulation patterns.63 Aspergillus branches tend to be around 45 degrees while Fusarium branches tend to be 90 degrees. Aspergillus branches can directly bifurcate, known as dichotomous branching, rather than only produce side branches. Finally, Fusarium will produce micro- and macroconidia directly alongside hyphae, a process known as adventitious sporulation, while Aspergillus conidia are located on branching conidiophores;63 (Figure 1B and C) however, despite these differences in morphology practitioners using confocal microscopy have not been shown to be capable of differentiating the two molds.63 In a prospective observational cohort study comparing in vivo confocal microscopy images obtained from culture-positive Fusarium and Aspergillus infections, mean branch angle was 59.7° for Fusarium and 63.3° for Aspergillus, an insignificant difference. Dichotomous branching was identified in both Aspergillus and Fusarium ulcers, and no adventitious sporulation could be identified in Fusarium ulcers.65 A separate prospective study also found that branching angle did not differ between Fusarium and Aspergillus, however Aspergillus was found to produce larger hyphal diameter compared to Fusarium.66 In addition to its diagnostic utility, confocal microscopy has been shown to be useful in monitoring response to treatment. 61; 66; 67

Medical treatment of nonperforating ulcers

Three topical medications are currently offered for treatment of fungal ulcers that have not progressed to involve sclera or intraocular contents. Voriconazole, a member of the azole class of antifungals, along with amphotericin B and natamycin, both of which are polyene-type antifungals, comprise the entirety of topical antifungal options. Topical treatments are further limited as many antifungal compounds are fungistatic, rather than fungicidal, at concentrations used in topical preparation. Voriconazole, as with all members of the azole class, is fungistatic.68 Fungicidal activity for natamycin occurs only with high concentrations, >50 mg/ml, below which it remains only fungistatic.69 Amphotericin B displays fungicidal activity, particularly against Candida albicans, but fungicidal activity is less predictable against molds.70; 71; 72 73; 74; 75 Among these medications, only natamycin is FDA approved and commercially available for treatment of fungal ulcers in the USA. As demonstrated by Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial (MUTT), identification of the infectious fungi does have important connotation in selecting the appropriate antifungal. In this trial, which assessed the efficacy of topical natamycin versus topical voriconazole in treatment of fungal corneal ulcers, visual improvement in ulcers secondary to Fusarium was significantly increased in patients who received topical natamycin.76 Among non-Fusarium ulcers, no difference in visual acuity was found.

Regarding oral treatment options for fungal ulcers, azole class antifungals represent the mainstay. The mechanism of action of azole antifungals involves inhibition of cytochrome P450-dependent 14-alpha-sterole demethylase, an enzyme involved in the production of the critical cell membrane component ergosterol. The absence of ergosterol in the cell membrane and accumulation of this toxic compound increases the permeability of the fungal cell membrane which leads to cell lysis. No difference in the incidence of corneal perforation was found by MUTT when oral voriconazole was added to topical therapy.77 The mechanism of action of polyene antifungals also revolves around manipulation of ergosterol. Both amphotericin and natamycin function through binding and manipulation of ergosterol within the fungal cell membrane, an action that also increases cell membrane permeability and leads to cell lysis;77; 78 however, systemic use of polyene antifungals in treatment of fungal ulcers remains limited by poor ocular penetration.

In case reports, topical caspofungin has shown promise.79 Furthermore, both systemic and topical application of echinocandins have been shown to have good penetration into the eye.80; 81 Use of 5-fluorocytosine to treat fungal ulcers continues to be limited, with rare case reports describing success in treating refractory Candida infections, often in conjunction with amphotericin. Unlike other classes of antifungal medications, 5-fluorocytosine is absorbed into fungal cells where it is converted to 5-fluorodeoxyuridylic acid monophosphate and 5-fluorouracil. These molecules are then incorporated into DNA and RNA strands, respectively, thereby inhibiting synthesis of both DNA and RNA;77 however, limited activity against Aspergillus and Fusarium restricts the usage of this drug mainly to ulcers with positive Candida culture results that are refractory to more conventional antifungals.

In addition to standard antifungal medication, the commonly used antiseptic agent chlorhexidine has been proposed as a potential alternative. Though commonly used in the treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis, chlorhexidine has been shown to inhibit the growth of fungal isolates obtained from corneal ulcers in vitro,82 two clinical trials comparing the efficacy of chlorhexidine gluconate (0.2%) and natamycin in treating filamentous fungal ulcers have suggested that chlorhexidine has greater efficacy than natamycin.83 84 Larger trials, however, are needed to further determine the dose of chlorhexidine needed as well as its efficacy compared to the standard 5% natamycin suspension.85

While the addition of topical corticosteroids to treat bacterial ulcers continues to be debated, the use of topical steroids in the treatment of fungal ulcers is inappropriate. In a retrospective study involving topical steroid use in culture-proven fungal ulcers, patients who received steroids were found to have worse final visual acuity along with high rates of treatment failure and surgical intervention. Initial depth of infiltration was found to be higher in the group receiving steroids, but otherwise no significant differences were noted in initial clinical characteristics.86 While this discrepancy in initial depth of penetration could be secondary to practice patterns that involve initiation of topical steroids in more severe ulcers, a separate study also found that vertical orientation of fungal hyphae (as opposed to the more commonly seen horizontal, inter-lamellar arrangement) was more commonly found in corneal buttons excised from patients who received preoperative topical steroids.87 Deposteroids are contraindicated.88

Multiple studies of fungal ulcers have reported a high cure rate with medical therapy;89; 90; 91. however, several clinical features, namely depth and diameter of infiltration, are correlated with greater risk of treatment failure and corneal perforation.92; 93 For high-risk infections, the use of injectable antifungal medication, structural stabilization with corneal glue, or therapeutic keratoplasty may be necessary to salvage vision.

Procedural Treatments

Aside from systemic and topical antifungal medications, alternative therapies such as crosslinking and photodynamic light treatment have been offered as potential treatment options. Crosslinking for infectious corneal ulcers, also known as photo activated chromophore for keratitis-corneal crosslinking (PACK-CXL) typically consists of corneal deepithelialization, followed by topical 0.1% riboflavin applied in a dropwise manner for 30 minutes, followed by UVA light (365nm) treatment for 30 minutes.94 Variations of this procedure, which was originally based on the Dresden protocol for crosslinking in keratoconus, have also been introduced with the goal of diminishing total treatment time.95 In in vivo studies, addition of corneal crosslinking to standard antifungal medical regimens has been shown to decrease the size of corneal ulceration, number and frequency of antifungal medications used, and time to resolution of ulceration.95 In ex vivo and in vitro studies, crosslinking as monotherapy has been shown to decrease both hyphal and spore volume in Fusarium species.94 In in-vitro mouse models corneal crosslinking with riboflavin and UVA treatment as sole therapy for fungal ulcers has been found to decrease clinical scores of ulcer size and depth of penetration. Histologic analysis of these mouse models furthermore revealed reduced damage to corneal collagen fibers and reduced influx of inflammatory cells.

A novel treatment method involving application of topical rose bengal coupled with photodynamic therapy has shown significant promise in treating refractory cases of Aspergilus and Curvularia keratitis.96; 97 Like corneal crosslinking, this method also requires initial de-epithelialization of the cornea. Topical 0.1% or 0.2% rose bengal is then applied to the corneal surface in a dropwise manner for 30 minutes followed by application of green light (518nm) for 15 minutes. Comparative in vitro studies involving this technique and PACK-CXL have shown that rose bengal-mediated PDT is able to directly inhibit growth of Fusarium, Aspergillus, and Candida, while no direct antifungal effects were found with PACK-CXL treatments.98 Initial case reports and case series describing rose bengal-mediated PDT have shown promising responses when used as adjunct treatment for ulcers caused by Fusarium and Curvularia; 96; 97 however, long term outcomes and prospective randomized studies are needed to better understand their role in management of fungal keratitis.

In addition to topical and systemic preparation, intracameral and intrastromal injection of antifungal drugs can also be performed. Indications for intracameral and intrastromal injections typically include involvement of the deep stromal layers, significant anterior chamber reaction, and ulcers refractory to topical and systemic therapies. Although more invasive compared to conventional treatment, these injection methods not only offer locally targeted drug delivery but are also, at least in theory, able to provide a drug depot which can offer prolonged therapeutic drug levels. Medication options for both intracameral and intrastromal injection include amphotericin, at a dose of 5–10 μg/0.1 ml, and voriconazole at 50 μg/0.1 ml.37; 38 Intrastromal injections of natamycin have been attempted in animal models of Fusarium keratitis, however no benefit was found. In several case reports, the procedure for performing an intrastromal injection involves penetration to midstroma with a 30-gauge needle from more peripheral, healthy-appearing corneal tissue. The needle is then advanced to the ulcer margin and multiple divided doses of drug are given to surround the ulcer margin.99 Intrastromal injections appear to offer improved longevity of therapeutic drug concentration within the target tissue compared to intracameral injection. In one study the half-life of intracameral voriconazole was found to be just 22 minutes. In a case series of 25 patients with fungal ulcers refractory to topical treatments, multiple intracameral injections were required in only 15% of patients. Of note, several large case series have found difficulty in treating Fusarium subgroups despite inclusion of either intrastromal voriconazole or intrastromal amphotericin.

In the case of descemetocele formation or small perforation, cyanoacrylate glue can be used to temporarily provide structural strength. In a case series involving placement of glue in significantly thinned or corneas with small perforations caused by filamentous fungi, 63.6% of cases resolved with scar formation.100 Success rates were predictably higher in infiltrates smaller in diameter. The authors found that frequent dislodgement of tissue glue occurred in fungal ulcers, particularly when the glue was placed for perforation. Additionally, among the cases where a fungal infiltrate resolved, the longevity of the glue treatment was increased, with 61.9% having glue on the eye for more than one month.

Finally, therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty might be needed. Corneas with impending perforation or perforation are a common indication for penetrating keratoplasty; however, these transplants have high rates of recurrent infection and graft failure. Recurrence rates in several case series range from 5% to 14%.101; 102 Higher rates of recurrence were found in cases involving corneal infections involving the limbus as well as cases with preoperative hypopyon and corneal perforation.101 Owing to the deep penetration of fungal hyphae, topical steroids are often delayed in the postoperative period following therapeutic keratoplasty. In one long term case series, medial graft survival length was only 5.9 months.90 Two risk factors for graft failure were identified: size of corneal infiltrate and size of the corneal graft.90 In a separate large study on therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty larger graft size was also found to be a significant risk factor for graft failure and poor visual outcomes.102

Molecular strategies of infection and resistance

Although more commonly described as a product of bacterial pathogens, biofilms are vitally important to the development and maintenance of corneal infections by fungi. Like bacterial biofilms, fungal biofilms are essential in producing environments conductive to fungal growth and propagation, and are important defenses against antifungal agents. These biofilms consist of a complex mixture of carbohydrate polymers, proteins, and extracellular DNA. Fusarium species capable of producing a biofilm have been shown to have significantly higher resistance to antifungal drugs compared to non-biofilm producing isolates.103Fusarium biofilms have furthermore been found to reduce fungal mortality when exposed to UV light.103 Similar results have been found in both Candida and Aspergillus species capable of producing biofilms.104; 105 Among keratitis-causing Fusarium species, biofilm formation does affect resistance to antifungal drugs. Biofilm thickness alone does not correlate with degree of resistance.106 These results suggests that more intricate biochemical properties underlie this imparted resistance. Formation of biofilms has been implicated in infections related to contact lens use.106; 107; 108 Studies on Fusarium isolates from a 2005–2007 outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with a contact lens cleaning solution found that 100% of isolates were capable of forming biofilms on contact lenses;107 however, biofilm formation is not a necessary step in the infection process for all fungal isolates. In a study involving Candida isolates obtained from patients with corneal ulcers, endophthalmitis, and orbital cellulitis (76% of which were isolated from corneal ulcers), only 53.4% were found to be capable of producing a biofilm.109 Similar results have been found in Fusarium models, in which only 52% of Fusarium isolates causing keratitis were able to produce biofilms. While Fusarium biofilms have also been found to offer higher levels of antifungal resistance, almost half of all Fusarium isolates obtained from corneal scrapings were found to be incapable of producing a biofilm.

In addition to biofilms, Fusarium, Candida, and Aspergillus fungi have each been shown to produce a variety of secretory enzymes and proteins that dissolve host tissue and combat host immune responses.12; 26; 109; 110 For both bacterial and fungal infections, production of specific proteases has been correlated with pathogenicity and virulence of individual organisms. Fusarium and Aspergillus isolates obtained from corneal ulcers produce a wide variety of proteases. 110 111 While further characterization of the particular function of each protease still needs to be elucidated, the production of these proteases is undoubtedly important in establishing infections, degrading stromal collagens, and potentially serving as combatants against the host immune system. Future therapeutic agents need to aim not only to destruction of fungal pathogens but to reduction of stromal destruction and release of chemotactic molecules from the degrading stroma.

Mechanisms of fungal resistance to antifungal drugs include drug molecule manipulation, drug efflux, alteration of target sites, and upregulation of intracellular enzymes targeted by drugs.77; 78 In biofilm-forming fungi, drug resistance also appears to be tied to the level of maturity of biofilms. Over time, biofilms produced by Candida albicans will alter the level ergosterol composition and efflux pump concentration. In early biofilms, resistance to antifungal drugs is predominantly carried out by efflux pumps. As the biofilm matures and ergosterol composition changes, resistance is instead conferred by decreasing ergosterol concentration.

Drug efflux pumps have been found in a variety of Candida species and appear to be critical in conferring azole resistance.112 These transporters, encoded by a variety of genes, including CDR, MDR, and BENr, allow Candida cells to greatly diminish intracellular concentrations of a variety of azoles and allow for adequate production of ergosterol. Similar efflux pumps have also been discovered in both Apergillus and Fusarium. Further research into these efflux pumps has shown that blocking certain efflux pumps not only improves antifungal susceptibility but impairs cell adhesion and development of biofilms.113

Azole resistance in both Candida and Aspergillus is thought to be secondary to altered expression of the gene encoding 14-alpha-sterole demethylase, CYP51 (also known as ERG11).77 Other Candida and Aspergillus isolates have developed reduced susceptibility to azole drugs simply by upregulating production of 14-alpha-sterole demethylase.77 Candida strains resistant to both azoles and polyenes have also been reported. Mutations in a second gene involved in ergosterol synthesis, ERG3, have been identified as a possible source of resistance. In the absence of ERG3, which encodes sterol C-5 desaturase, blocking of ergosterol production by azoles does not lead to accumulation of toxic 14α-methyl-3,6-diol and instead produces a more tolerated compound 14α-methylfecosterol. Since ergosterol is not present in the cell membrane, these mutants are also resistant to polyene antifungals. Antifungal resistance profiles of Fusarium isolates capable of causing corneal ulcers show widespread resistance to not only azole class drugs, but echinocandins and polyenes as well.

Conclusions

Fungal keratitis continues to pose a substantial challenge. These organisms have adapted to a broad range of environments in nature, in human living spaces, and even in hospitals and care facilities. Thus, fungi capable of causing corneal ulcers can be found in close proximity to potential hosts.

While culturing and direct microscopy remain the gold standard for detection of fungal pathogens, significant headway has been made in developing alternate methods that offer more rapid identification. PCR testing in particular appears well suited to offer both rapid and species-specific identification. PCR offers additional advantages of being able to detect molecular traces of organisms; however, concerns regarding high false-negative and false-positive results exist due to difficulty in cell lysis and ubiquity in both natural and man-made environments. Confocal microscopy can provide real-time, in vivo diagnosis; however, the cost of these instruments, dependence on practitioner experience and patient cooperation, and inability to reliably detect specific species or genera limits their utility. Options for topical antifungal therapy continue to be very limited, with only one commercially available drug. Prescription of additional topical antifungal therapies requires a compounding pharmacy, which incurs not only a cost but often significant travel for patients in rural communities. A wider range of medications exist in systemic form, but evidence regarding ocular penetration and efficacy in treating corneal infections for these is limited. To add an additional challenge, many fungal pathogens have evolved virulence factors that provide antifungal resistance and aid in establishing and disseminating infections. Despite these challenges, advances in our understanding of fungal life cycle, virulence factors, and antifungal susceptibility will hopefully continue.

Methods of literature search.

PubMed search was performed using the search terms: “fungal keratitis” in combination with candida, fusarium, endothelial transplant candida, antifungals. Searches were performed and constantly updated until April 3rd 2021. Articles were excluded if they were not referenced in English due to authors poor knowledge of other languages.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH/NEI grant EY029395 to EE.

Footnotes

The authors report no commercial or proprietary interest in any product or concept discussed in this article

Proprietary interests: None of the authors has any proprietary interests in devices, medications or other topics discussed in this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gower EW, Keay LJ, Oechsler RA, et al. : Trends in fungal keratitis in the United States, 2001 to 2007. Ophthalmology. 2010; 117:2263–2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuli SS: Fungal keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011; 5:275–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg P, Roy A, Roy S: Update on fungal keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016; 27:333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J: Update on the Management of Infectious Keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017; 124:1678–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kredics L, Narendran V, Shobana CS, et al. : Filamentous fungal infections of the cornea: a global overview of epidemiology and drug sensitivity. Mycoses. 2015; 58:243–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahmoudi S, Masoomi A, Ahmadikia K, et al. : Fungal keratitis: An overview of clinical and laboratory aspects. Mycoses. 2018; 61:916–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, Lass-Florl C: Antifungal drug resistance among Candida species: mechanisms and clinical impact. Mycoses. 2015; 58 Suppl 2:2–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiederhold NP: Antifungal resistance: current trends and future strategies to combat. Infect Drug Resist. 2017; 10:249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray P: Medical Microbiology, Elsevier, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuen GY, Schoneweis SD: Strategies for managing Fusarium head blight and deoxynivalenol accumulation in wheat. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007; 119:126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagenais TR, Keller NP: Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in Invasive Aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009; 22:447–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer FL, Wilson D, Hube B: Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence. 2013; 4:119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallen RM, Perlin MH: An Overview of the Function and Maintenance of Sexual Reproduction in Dikaryotic Fungi. Front Microbiol. 2018; 9:503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo HJ, Kohler JR, DiDomenico B, et al. : Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell. 1997; 90:939–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson BE, Mitchell BM, Wilhelmus KR: Corneal virulence of Candida albicans strains deficient in Tup1-regulated genes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48:2535–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson BE, Wilhelmus KR, Hube B: The role of secreted aspartyl proteinases in Candida albicans keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48:3559–3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown L, Leck AK, Gichangi M, et al. : The global incidence and diagnosis of fungal keratitis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021; 21:e49–e57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alfonso EC, Cantu-Dibildox J, Munir WM, et al. : Insurgence of Fusarium keratitis associated with contact lens wear. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006; 124:941–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritterband DC, Seedor JA, Shah MK, et al. : Fungal keratitis at the new york eye and ear infirmary. Cornea. 2006; 25:264–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keay LJ, Gower EW, Iovieno A, et al. : Clinical and microbiological characteristics of fungal keratitis in the United States, 2001–2007: a multicenter study. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:920–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jurkunas U, Behlau I, Colby K: Fungal keratitis: changing pathogens and risk factors. Cornea. 2009; 28:638–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barran LR, Miller RW: Temperature-induced alterations in phospholipids of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Can J Microbiol. 1976; 22:557–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scruggs AC, Quesada-Ocampo LM: Etiology and Epidemiological Conditions Promoting Fusarium Root Rot in Sweetpotato. Phytopathology. 2016; 106:909–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwon-Chung KJ, Sugui JA: Aspergillus fumigatus--what makes the species a ubiquitous human fungal pathogen? PLoS Pathog. 2013; 9:e1003743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brakhage AA, Langfelder K: Menacing mold: the molecular biology of Aspergillus fumigatus. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2002; 56:433–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talapko J, Juzbasic M, Matijevic T, et al. : Candida albicans-The Virulence Factors and Clinical Manifestations of Infection. J Fungi (Basel). 2021; 7: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun RL, Jones DB, Wilhelmus KR: Clinical characteristics and outcome of Candida keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007; 143:1043–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiao GL, Ling J, Wong T, et al. : Candida Keratitis: Epidemiology, Management, and Clinical Outcomes. Cornea. 2020; 39:801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keyhani K, Seedor JA, Shah MK, et al. : The incidence of fungal keratitis and endophthalmitis following penetrating keratoplasty. Cornea. 2005; 24:288–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilhelmus KR, Hassan SS: The prognostic role of donor corneoscleral rim cultures in corneal transplantation. Ophthalmology. 2007; 114:440–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vislisel JM, Goins KM, Wagoner MD, et al. : Incidence and Outcomes of Positive Donor Corneoscleral Rim Fungal Cultures after Keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 2017; 124:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mian SI, Aldave AJ, Tu EY, et al. : Incidence and Outcomes of Positive Donor Rim Cultures and Infections in the Cornea Preservation Time Study. Cornea. 2018; 37:1102–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau N, Hajjar Sese A, Augustin VA, et al. : Fungal infection after endothelial keratoplasty: association with hypothermic corneal storage. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019; 103:1487–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aldave AJ, DeMatteo J, Glasser DB, et al. : Report of the Eye Bank Association of America medical advisory board subcommittee on fungal infection after corneal transplantation. Cornea. 2013; 32:149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das S, Ramappa M, Mohamed A, et al. : Acute endophthalmitis after penetrating and endothelial keratoplasty at a tertiary eye care center over a 13-year period. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020; 68:2445–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma N, Kaur M, Titiyal JS, Aldave A: Infectious keratitis after lamellar keratoplasty. Surv Ophthalmol. 2020; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Tu EY, Hou J: Intrastromal antifungal injection with secondary lamellar interface infusion for late-onset infectious keratitis after DSAEK. Cornea. 2014; 33:990–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tu EY, Majmudar PA: Adjuvant Stromal Amphotericin B Injection for Late-Onset DMEK Infection. Cornea. 2017; 36:1556–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palioura S, Sivaraman K, Joag M, et al. : Candida Endophthalmitis After Descemet Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty With Grafts From Both Eyes of a Donor With Possible Systemic Candidiasis. Cornea. 2018; 37:515–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dahlgren MA, Lingappan A, Wilhelmus KR: The clinical diagnosis of microbial keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007; 143:940–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dalmon C, Porco TC, Lietman TM, et al. : The clinical differentiation of bacterial and fungal keratitis: a photographic survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53:1787–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forster RK, Rebell G, Wilson LA: Dematiaceous fungal keratitis. Clinical isolates and management. Br J Ophthalmol. 1975; 59:372–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berger ST, Katsev DA, Mondino BJ, Pettit TH: Macroscopic pigmentation in a dematiaceous fungal keratitis. Cornea. 1991; 10:272–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barton K, Miller D, Pflugfelder SC: Corneal chromoblastomycosis. Cornea. 1997; 16:235–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vicente A, Pedrosa Domellof F, Bystrom B: Exophiala phaeomuriformis keratitis in a subarctic climate region: a case report. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018; 96:425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bui AQ, Espana EM, Margo CE: Chromoblastomycosis of the conjunctiva mimicking melanoma of the ciliary body. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012; 130:1615–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brandt ME, Warnock DW: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and therapy of infections caused by dematiaceous fungi. J Chemother. 2003; 15 Suppl 2:36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dixon DM, Polak-Wyss A: The medically important dematiaceous fungi and their identification. Mycoses. 1991; 34:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oddo D, Cisternas D, Mendez GP: Pseudodematiaceous Fungi in Rhinosinusal Biopsies: Report of 2 Cases With Light and Electron Microscopy Analysis. Clin Pathol. 2019; 12:2632010X19874766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guarner J, Brandt ME: Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011; 24:247–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gajjar DU, Pal AK, Ghodadra BK, Vasavada AR: Microscopic evaluation, molecular identification, antifungal susceptibility, and clinical outcomes in fusarium, Aspergillus and, dematiaceous keratitis. Biomed Res Int. 2013; 2013:605308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang W, Yang H, Jiang L, et al. : Use of potassium hydroxide, Giemsa and calcofluor white staining techniques in the microscopic evaluation of corneal scrapings for diagnosis of fungal keratitis. J Int Med Res. 2010; 38:1961–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rathi VM, Thakur M, Sharma S, et al. : KOH mount as an aid in the management of infectious keratitis at secondary eye care centre. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017; 101:1447–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Afshar P, Larijani LV, Rouhanizadeh H: A comparison of conventional rapid methods in diagnosis of superficial and cutaneous mycoses based on KOH, Chicago sky blue 6B and calcofluor white stains. Iran J Microbiol. 2018; 10:433–440. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas PA, Kuriakose T, Kirupashanker MP, Maharajan VS: Use of lactophenol cotton blue mounts of corneal scrapings as an aid to the diagnosis of mycotic keratitis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991; 14:219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chander J, Chakrabarti A, Sharma A, et al. : Evaluation of Calcofluor staining in the diagnosis of fungal corneal ulcer. Mycoses. 1993; 36:243–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharma S, Rathi VM, Murthy SI, et al. : Application of Trypan Blue Stain in the Microbiological Diagnosis of Infectious Keratitis-A Case Series. Cornea. 2021; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Zhao G, Zhai H, Yuan Q, et al. : Rapid and sensitive diagnosis of fungal keratitis with direct PCR without template DNA extraction. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014; 20:O776–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oechsler RA, Feilmeier MR, Miller D, et al. : Fusarium keratitis: genotyping, in vitro susceptibility and clinical outcomes. Cornea. 2013; 32:667–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anutarapongpan O, Maestre-Mesa J, Alfonso EC, et al. : Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for Screening of Mycotoxin Genes From Ocular Isolates of Fusarium species. Cornea. 2018; 37:1042–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Labbe A, Khammari C, Dupas B, et al. : Contribution of in vivo confocal microscopy to the diagnosis and management of infectious keratitis. Ocul Surf. 2009; 7:41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumar RL, Cruzat A, Hamrah P: Current state of in vivo confocal microscopy in management of microbial keratitis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2010; 25:166–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chidambaram JD, Prajna NV, Larke NL, et al. : Prospective Study of the Diagnostic Accuracy of the In Vivo Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope for Severe Microbial Keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2016; 123:2285–2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kheirkhah A, Syed ZA, Satitpitakul V, et al. : Sensitivity and Specificity of Laser-Scanning In Vivo Confocal Microscopy for Filamentous Fungal Keratitis: Role of Observer Experience. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017; 179:81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chidambaram JD, Prajna NV, Larke N, et al. : In vivo confocal microscopy appearance of Fusarium and Aspergillus species in fungal keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017; 101:1119–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tabatabaei SA, Soleimani M, Tabatabaei SM, et al. : The use of in vivo confocal microscopy to track treatment success in fungal keratitis and to differentiate between Fusarium and Aspergillus keratitis. Int Ophthalmol. 2020; 40:483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shi W, Li S, Liu M, et al. : Antifungal chemotherapy for fungal keratitis guided by in vivo confocal microscopy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008; 246:581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kyle AA, Dahl MV: Topical therapy for fungal infections. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004; 5:443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Betbeze CM, Wu CC, Krohne SG, Stiles J: In vitro fungistatic and fungicidal activities of silver sulfadiazine and natamycin on pathogenic fungi isolated from horses with keratomycosis. Am J Vet Res. 2006; 67:1788–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meletiadis J, Antachopoulos C, Stergiopoulou T, et al. : Differential fungicidal activities of amphotericin B and voriconazole against Aspergillus species determined by microbroth methodology. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007; 51:3329–3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lewis RE, Lund BC, Klepser ME, et al. : Assessment of antifungal activities of fluconazole and amphotericin B administered alone and in combination against Candida albicans by using a dynamic in vitro mycotic infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998; 42:1382–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumar A, Zarychanski R, Pisipati A, et al. : Fungicidal versus fungistatic therapy of invasive Candida infection in non-neutropenic adults: a meta-analysis. Mycology. 2018; 9:116–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vendetti N, Bryan M, Zaoutis TE, et al. : Comparative effectiveness of fungicidal vs. fungistatic therapies for the treatment of paediatric candidaemia. Mycoses. 2016; 59:173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Espinel-Ingroff A: In vitro antifungal activities of anidulafungin and micafungin, licensed agents and the investigational triazole posaconazole as determined by NCCLS methods for 12,052 fungal isolates: review of the literature. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2003; 20:121–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Klepser ME, Wolfe EJ, Jones RN, et al. : Antifungal pharmacodynamic characteristics of fluconazole and amphotericin B tested against Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997; 41:1392–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, et al. : The mycotic ulcer treatment trial: a randomized trial comparing natamycin vs voriconazole. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013; 131:422–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kanafani ZA, Perfect JR: Antimicrobial resistance: resistance to antifungal agents: mechanisms and clinical impact. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 46:120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ghannoum MA, Rice LB: Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999; 12:501–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hurtado-Sarrio M, Duch-Samper A, Cisneros-Lanuza A, et al. : Successful topical application of caspofungin in the treatment of fungal keratitis refractory to voriconazole. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010; 128:941–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mochizuki K, Sawada A, Suemori S, et al. : Intraocular penetration of intravenous micafungin in inflamed human eyes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013; 57:4027–4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vorwerk CK, Tuchen S, Streit F, et al. : Aqueous humor concentrations of topically administered caspofungin in rabbits. Ophthalmic Res. 2009; 41:102–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martin MJ, Rahman MR, Johnson GJ, et al. : Mycotic keratitis: susceptibility to antiseptic agents. Int Ophthalmol. 1995; 19:299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rahman MR, Johnson GJ, Husain R, et al. : Randomised trial of 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate and 2.5% natamycin for fungal keratitis in Bangladesh. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998; 82:919–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rahman MR, Minassian DC, Srinivasan M, et al. : Trial of chlorhexidine gluconate for fungal corneal ulcers. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1997; 4:141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hoffman JJ, Yadav R, Das Sanyam S, et al. : Topical chlorhexidine 0.2% versus topical natamycin 5% for fungal keratitis in Nepal: rationale and design of a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ Open. 2020; 10:e038066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cho CH, Lee SB: Clinical analysis of microbiologically proven fungal keratitis according to prior topical steroid use: a retrospective study in South Korea. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019; 19:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Panda A, Mohan M, Mukherjee G: Mycotic keratitis in Indian patients (a histopathological study of corneal buttons). Indian J Ophthalmol. 1984; 32:311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jeang LJ, Davis A, Madow B, et al. : Occult Fungal Scleritis. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2017; 3:41–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.FlorCruz NV, Evans JR: Medical interventions for fungal keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; CD004241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Mundra J, Dhakal R, Mohamed A, et al. : Outcomes of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty in 198 eyes with fungal keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019; 67:1599–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Rajaraman R, et al. : Effect of Oral Voriconazole on Fungal Keratitis in the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial II (MUTT II): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016; 134:1365–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Rajaraman R, et al. : Predictors of Corneal Perforation or Need for Therapeutic Keratoplasty in Severe Fungal Keratitis: A Secondary Analysis of the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial II. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017; 135:987–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Murphy-Ullrich JE, Sage EH: Revisiting the matricellular concept. Matrix Biol. 2014; 37:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Alshehri JM, Caballero-Lima D, Hillarby MC, et al. : Evaluation of Corneal Cross-Linking for Treatment of Fungal Keratitis: Using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy on an Ex Vivo Human Corneal Model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016; 57:6367–6373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Knyazer B, Krakauer Y, Baumfeld Y, et al. : Accelerated Corneal Cross-Linking With Photoactivated Chromophore for Moderate Therapy-Resistant Infectious Keratitis. Cornea. 2018; 37:528–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Amescua G, Arboleda A, Nikpoor N, et al. : Rose Bengal Photodynamic Antimicrobial Therapy: A Novel Treatment for Resistant Fusarium Keratitis. Cornea. 2017; 36:1141–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Naranjo A, Arboleda A, Martinez JD, et al. : Rose Bengal Photodynamic Antimicrobial Therapy for Patients With Progressive Infectious Keratitis: A Pilot Clinical Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019; 208:387–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Arboleda A, Miller D, Cabot F, et al. : Assessment of rose bengal versus riboflavin photodynamic therapy for inhibition of fungal keratitis isolates. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014; 158:64–70 e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tu EY: Alternaria keratitis: clinical presentation and resolution with topical fluconazole or intrastromal voriconazole and topical caspofungin. Cornea. 2009; 28:116–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Garg P, Gopinathan U, Nutheti R, Rao GN: Clinical experience with N-butyl cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive in fungal keratitis. Cornea. 2003; 22:405–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shi W, Wang T, Xie L, et al. : Risk factors, clinical features, and outcomes of recurrent fungal keratitis after corneal transplantation. Ophthalmology. 2010; 117:890–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sharma N, Jain M, Sehra SV, et al. : Outcomes of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty from a tertiary eye care centre in northern India. Cornea. 2014; 33:114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cordova-Alcantara IM, Venegas-Cortes DL, Martinez-Rivera MA, et al. : Biofilm characterization of Fusarium solani keratitis isolate: increased resistance to antifungals and UV light. J Microbiol. 2019; 57:485–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chandra J, Mukherjee PK: Candida Biofilms: Development, Architecture, and Resistance. Microbiol Spectr. 2015; 3: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kaur S, Singh S: Biofilm formation by Aspergillus fumigatus. Med Mycol. 2014; 52:2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mukherjee PK, Chandra J, Yu C, et al. : Characterization of fusarium keratitis outbreak isolates: contribution of biofilms to antimicrobial resistance and pathogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53:4450–4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dyavaiah M, Ramani R, Chu DS, et al. : Molecular characterization, biofilm analysis and experimental biofouling study of Fusarium isolates from recent cases of fungal keratitis in New York State. BMC Ophthalmol. 2007; 7:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Abou Shousha M, Santos AR, Oechsler RA, et al. : A novel rat contact lens model for Fusarium keratitis. Mol Vis. 2013; 19:2596–2605. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ranjith K, Sontam B, Sharma S, et al. : Candida Species From Eye Infections: Drug Susceptibility, Virulence Factors, and Molecular Characterization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017; 58:4201–4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhu WS, Wojdyla K, Donlon K, et al. : Extracellular proteases of Aspergillus flavus. Fungal keratitis, proteases, and pathogenesis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990; 13:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.de Paulo LF, Coelho AC, Svidzinski TI, et al. : Crude extract of Fusarium oxysporum induces apoptosis and structural alterations in the skin of healthy rats. J Biomed Opt. 2013; 18:095004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Holmes AR, Cardno TS, Strouse JJ, et al. : Targeting efflux pumps to overcome antifungal drug resistance. Future Med Chem. 2016; 8:1485–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.R AC, Portela FV, Pereira LM, et al. : Efflux pump inhibition controls growth and enhances antifungal susceptibility of Fusarium solani species complex. Future Microbiol. 2020; 15:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]