Abstract

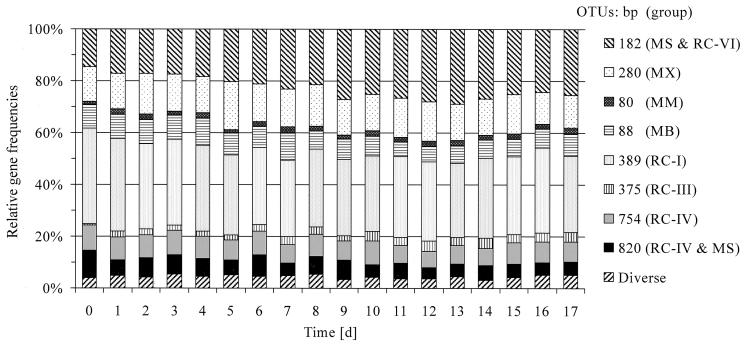

The population dynamics of Archaea after flooding of an Italian rice field soil were studied over 17 days. Anoxically incubated rice field soil slurries exhibited a typical sequence of reduction processes characterized by reduction of nitrate, Fe3+, and sulfate prior to the initiation of methane production. Archaeal population dynamics were followed using a dual approach involving molecular sequence retrieval and fingerprinting of small-subunit (SSU) rRNA genes. We retrieved archaeal sequences from four clone libraries (30 each) constructed for different time points (days 0, 1, 8, and 17) after flooding of the soil. The clones could be assigned to known methanogens (i.e., Methanosarcinaceae, Methanosaetaceae, Methanomicrobiaceae, and Methanobacteriaceae) and to novel euryarchaeotal (rice clusters I, II, and III) and crenarchaeotal (rice clusters IV and VI) lineages previously detected in anoxic rice field soil and on rice roots (R. Grosskopf, S. Stubner, and W. Liesack, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4983–4989, 1998). During the initiation of methanogenesis (days 0 to 17), we detected significant changes in the frequency of individual clones, especially of those affiliated with the Methanosaetaceae and Methanobacteriaceae. However, these findings could not be confirmed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis of SSU rDNA amplicons. Most likely, the fluctuations in sequence composition of clone libraries resulted from cloning bias. Clonal SSU rRNA gene sequences were used to define operational taxonomic units (OTUs) for T-RFLP analysis, which were distinguished by group-specific TaqI restriction sites. Sequence analysis showed a high degree of conservation of TaqI restriction sites within the different archaeal lineages present in Italian rice field soil. Direct T-RFLP analysis of archaeal populations in rice field soil slurries revealed the presence of all archaeal lineages detected by cloning with a predominance of terminal restriction fragments characteristic of rice cluster I (389 bp), Methanosaetaceae (280 bp), and Methanosarcinaceae/rice cluster VI (182 bp). In general, the relative gene frequency of most detected OTUs remained rather constant over time during the first 17 days after flooding of the soil. Most minor OTUs (e.g., Methanomicrobiaceae and rice cluster III) and Methanosaetaceae did not change in relative frequency. Rice cluster I (37 to 30%) and to a lesser extent rice cluster IV as well as Methanobacteriaceae decreased over time. Only the relative abundance of Methanosarcinaceae (182 bp) increased, roughly doubling from 15 to 29% of total archaeal gene frequency within the first 11 days, which was positively correlated to the dynamics of acetate and formate concentrations. Our results indicate that a functionally dynamic ecosystem, a rice field soil after flooding, was linked to a relatively stable archaeal community structure.

In most anaerobic ecosystems, methanogenic Archaea significantly affect carbon cycling, since fermentable substrates are degraded completely to CO2 and CH4 via the anaerobic food chain, with methanogenesis as the predominant terminal respiratory process (41). Important habitats for methane-forming Archaea are wetlands, including rice field soils. The latter are estimated to contribute about 25% to the budget of global methane emissions (36) and therefore have a significant impact on global warming (25).

In periodically submerged wetlands such as rice field soils, CH4 production is initiated shortly after flooding, only after inorganic electron acceptors such as oxygen, nitrate, manganese(IV), iron(III), and sulfate have been reduced sequentially. Although biogeochemical processes after the flooding of rice field soil have been studied in detail, the factors controlling the initiation of methanogenesis are not fully understood (10). The sequence of reduction processes is best described by the thermodynamic theory, which predicts preferential reduction of available electron acceptors with the most positive redox potential (35, 50). For a variety of soils, this sequence of reduction processes has been demonstrated after flooding (1, 32, 33). However, in most soils, initiation of methane production deviates from the predicted concept of sequential reduction. Methane formation, albeit at trace amounts, could be observed directly after flooding of rice field soils despite the presence of oxidants such as nitrate, iron(III), and sulfate (40, 48, 49). Similarly, methane formation was observed at redox potentials of 0 to 70 mV after flooding of oxic soils (33) and in pure cultures of Methanosarcina barkeri (14), although it is generally assumed that methanogens become active only at redox potentials below −150 mV (50). Apparently, methanogenic Archaea in soils are activated much faster than was previously thought (40).

Understanding the function of ecosystems requires comprehension of both biogeochemical processes and microbial community structures (10, 44). With respect to the archaeal populations involved in the initiation of methanogenesis after the flooding of soils, the central questions are which factors control the diversity and abundance of methanogens and how, if at all, populations alter in response to changing environmental conditions.

Few data are available about the population dynamics of methanogens after the flooding of soils. Using most-probable-number counts, it has been shown for geographically diverse rice field soils that the total population size of methanogens remains rather constant even after periods of drainage and aeration (30) and when monitored over 2 years (3). However, the methanogenic activity may undergo a shift from hydrogenotrophy to acetotrophy during the initiation of methane production, as suggested by methyl fluoride inhibition experiments (40). Currently, we can only speculate whether this shift in activity is also reflected in methanogenic population dynamics.

The known limitations of cultivation-dependent approaches (26) have hampered the retrieval of numerically abundant and functionally relevant microorganisms from complex environmental communities (2). The slow-growing or difficult-to-cultivate methanogenic Archaea especially may require extremely long incubation times (>1 year) to obtain most-probable-number cell counts (16). The application of molecular methods (i.e., the analysis of small-subunit [SSU] rRNA genes as universal markers [17, 47]) for community structure analysis facilitates detection and identification of microorganisms that are difficult to cultivate or may be regarded as unculturable from our current knowledge of the growth requirements of these microorganisms. With these methods at hand, the study of population structures becomes feasible for methanogenic ecosystems.

Molecular surveys of SSU rDNA sequences in anoxic rice field soil (9, 16) and on rice roots (15, 24) revealed a high archaeal diversity, including known methanogenic families (Methanosarcinaceae, Methanosaetaceae, Methanomicrobiaceae, and Methanobacteriaceae) as well as phylogenetically novel eury- and crenarchaeotal lineages, termed rice clusters I to VI (RC-I to RC-VI). The phylogenetic positions of only two of these clusters (RC-I and -II) and their presence in methanogenic enrichment cultures (24) suggest an affiliation with methanogenic taxa. The ecophysiology of members of all other clusters (RC-III to RC-VI) is still unknown.

In this investigation, we studied the dynamics of archaeal populations after the flooding of rice field soil to establish a link between structure (which species) and function (metabolic activities) of the archaeal populations involved in the initiation of methanogenesis. Soil slurries were incubated anoxically over 17 days and sampled for chemical and molecular analyses. We followed changes in the archaeal community structure by analyzing SSU ribosomal DNA (rDNA) clone libraries derived from soil DNA extracts. In parallel, we determined relative gene frequencies as analyzed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) (27) analysis of archaeal SSU rDNA PCR fragments (9). Our results indicate a surprisingly stable archaeal community structure as analyzed by T-RFLP, considering the changes associated with the flooding of the soil. Only Methanosarcina-like populations were found to increase significantly in relative gene frequency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Soil samples and slurry experiments.

Soil was sampled in February 1997 from a drained rice field of the Italian Rice Research Institute near Vercelli (Po River valley, Italy). Soil parameters were described previously (8). The soil was air dried and stored at room temperature. Preparation of the soil and sieving (mesh size, 2 mm) were done as previously described (8). Soil slurries (3 g of dry soil and 3 g of sterile double-distilled water) were prepared in triplicate for each time point in 12.5-ml serum vials which were sealed with butyl rubber septa. Anoxic incubations of soil slurries for each time point were started at daily intervals by the addition of anoxic water with a syringe. The headspaces of vials were flushed with N2 for 10 min, and vials were statically incubated at 25°C. At the end of the experiment, the vials were analyzed for gases (CH4, H2, and CO2). Slurry samples were taken, frozen, and stored (−20°C) for analyses of biogeochemical parameters (Fe2+, NO3−, NO2−, SO42−, and fatty acids) and molecular analyses.

Chemical analyses.

Pore water samples were analyzed by ion chromatography for the determination of nitrate and sulfate (5). Acetate and formate were analyzed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (23). Fe2+ was analyzed in slurry samples using the ferrozin reaction method (1). Gas samples (CH4, H2, and CO2) were taken from the headspaces of the flasks and measured by gas chromatography (40). Low H2 concentrations were determined by using a reducing gas detector (RGD2; Trace Analytical, Menlo Park, Calif.) (40).

Extraction of soil DNA and PCR amplification.

Total DNA was extracted from one soil sample for each time point using a direct lysis technique for cell disruption modified from Moré et al. (31) as described previously (19). Briefly, cells in soil samples (300 μl of slurry) were lysed by bead-beating (45 s at 6.5 m s−1) in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate solution. DNA was purified from the supernatant with ammonium acetate, isopropanol, and ethanol precipitation steps. Finally, the DNA extract was further purified using a silica matrix-based purification protocol (Prep-a-gene; Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). Aliquots of DNA extracts were analyzed by standard gel electrophoresis to verify extraction. DNA concentrations were quantified fluorometrically (PicoGreen dsDNA quantitation kit; Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands).

Archaeal SSU rRNA genes were specifically amplified from total soil DNA extracts using the primer combination Ar109f (5′-ACG/T GCT CAG TAA CAC GT-3′) and Ar912r (5′-CTC CCC CGC CAA TTC CTT TA-3′) modified from Grosskopf et al. (16). The reaction mixture contained, in a total volume of 50 μl, 1× PCR buffer II (PE Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 μM each of the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany), 0.5 μM each primer (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany), and 1.25 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (PE Applied Biosystems), and 1 μl of a 1:50 dilution of soil DNA extract was added as the template. All reactions were prepared at 4°C in 0.2-ml reaction tubes to avoid nonspecific priming. Amplification was started by placing the reaction tubes immediately into the preheated (94°C) block of a Gene Amp 9700 Thermocycler (PE Applied Biosystems). The standard thermal profile for the amplification of the partial SSU rRNA gene sequences was as follows: an initial denaturation step (5 min, 94°C) was followed by 28 cycles of denaturation (60 s, 94°C), annealing (60 s, 52°C), and extension (90 s, 72°C). After a terminal extension (6 min, 72°C), the samples were kept at 4°C until further analysis. Aliquots of the SSU rRNA gene amplicons (5 μl) were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and visualized after staining with ethidium bromide using a gel imaging system (MWG Biotech). PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Cloning and sequencing.

Archaeal SSU rDNA amplicons were cloned in Escherichia coli JM109 using the pGEM-T Easy Vector System (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Randomly selected clones were further analyzed and sequenced as described by Rotthauwe et al. (38).

Sequence data analysis and phylogenetic placement.

Raw sequence data were assembled and checked with the Lasergene software package (DNASTAR, Madison, Wis.). The phylogenetic analysis (i.e., alignment and treeing) was performed by using the ARB software package (version 2.5b; O. Strunk and W. Ludwig, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany, http://www.biol.chemie.tu-muenchen.de/pub/ARB/) as described previously in detail (15). Briefly, new sequences were fitted into an alignment of SSU rDNA sequences containing 758 partial (>700 nucleotides) or complete archaeal sequences retrieved from public databases (6) using the automated alignment tools of the ARB software package. When necessary, alignments were corrected manually. Chimera formation has been reported to occur during PCR amplification of mixed SSU rDNA (22, 46). The terminal 400 sequence positions of the 5′ and 3′ ends of the archaeal SSU rDNA sequences were used for fractional treeing to identify possible chimeras based on mismatches of the secondary SSU rRNA structure (28).

For treeing, almost full-length SSU rDNA sequences (>1,400 bases) were selected to construct an archaeal base frequency filter (50 to 100% similarity), which was subsequently used to generate an initial neighbor-joining tree using selected eury- and crenarchaeotal SSU rDNA reference sequences (>1,400 bases). Sequences from rice field soil clone libraries (635 to 770 nucleotides in length) were then added to this tree using the ARB parsimony tool, which allows the addition of short sequences to phylogenetic trees without changing global tree topologies (29). In addition, the tree topology was evaluated using fastDNAml as implemented in ARB. Public databases were screened for close relatives of rice field soil SSU rDNA clones as described previously (15). Rarefaction analysis of SSU rDNA clone libraries was performed using the Analytical Rarefaction software (version 1.2; S. M. Holland, University of Georgia, Athens, http://www.uga.edu/∼strata/Software.html).

T-RFLP analysis.

T-RFLP analysis was performed as described by Chin et al. (9) with minor modifications. PCR assays (100 μl) were used for the amplification of archaeal SSU rDNA genes following the above PCR protocol. From 400 to 800 pg of template DNA was used. PCR products were labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) at the 5′ end using the Ar912r primer. Alternatively, the 5′ FAM-labeled Ar109f primer was used. Prior to digestion, PCR product concentrations were determined photometrically. DNA (50 ng), 3 U of TaqI (Promega), 1 μl of the appropriate 10× incubation buffer (Promega), and 1 μg of bovine serum albumin were combined in a total volume of 10 μl and digested for 2 h at 65°C. Fluorescently labeled terminal restriction fragments (T-RFs) were size separated on an ABI 373A automated sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems). T-RFLP electropherograms were analyzed by peak area integration of the different T-RFs (GeneScan 2.1 software; PE Applied Biosystems). The percent fluorescence intensity represented by single T-RFs was calculated relative to the total fluorescence intensity of all T-RFs to obtain a measure of relative SSU rRNA gene frequency.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of SSU rDNA rice field clones of the four clone libraries (AS 00, AS 01, AS 08, and AS 17) were deposited in the GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ databases under accession numbers AF225574 to AF225693.

RESULTS

Sequential reduction in rice field soil slurries.

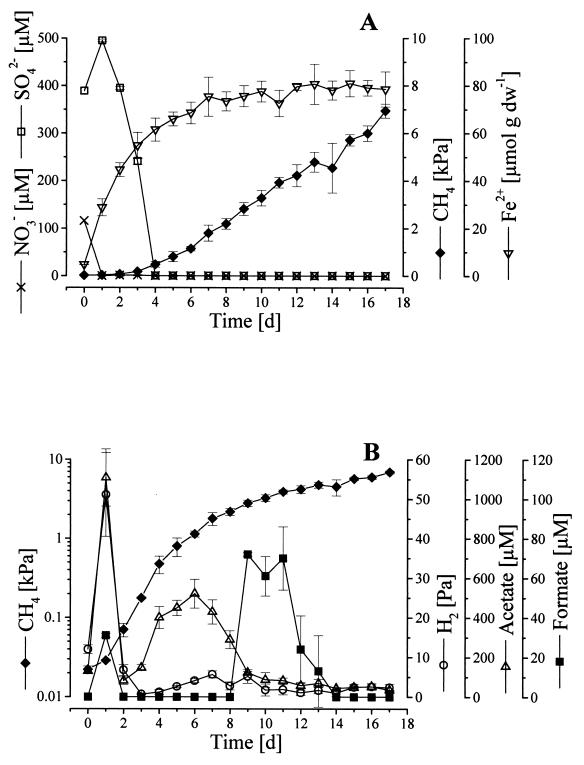

Reduction processes in the rice field soil started immediately after the onset of anoxia. Nitrate was present at a low concentration (116 μM) initially and fell below the detection limit within 24 h (Fig. 1A). Fe2+ increased rapidly after the start of incubation and approached a maximum amount of 80 μM Fe2+ (per gram dry weight [dw] of soil) after 7 days. Sulfate in the pore water increased from 390 to 490 μM during the first day, probably due to HCO3− or Fe3+ reduction-mediated desorption from ferric iron minerals (49), but was rapidly reduced subsequently and could not be detected after 4 days. After only 1 day of incubation, methane formation was detectable, albeit at low methane mixing ratios (40). Within the first 4 days, methane increased exponentially, as revealed by logarithmic plotting (Fig. 1B), although electron acceptors other than CO2 were still present (Fig. 1A). After 6 days of incubation, methane was produced at a constant rate of 0.5 μmol day−1 (g dw)−1.

FIG. 1.

Time course of sequential reduction processes in anoxically incubated rice field soil slurries. (A) Reduction of NO3− and SO42− and accumulation of Fe2+ and CH4. (B) Temporal changes in CH4 (logarithmic), H2, acetate, and formate. Bars, SD (n = 3).

The predominant methanogenic substrates, H2 and acetate, accumulated to high concentrations during the first day (51.1 ± 10.6 Pa and 1,108 ± 144 μM, respectively) (Fig. 1B). Both were then rapidly consumed, but while H2 remained detectable only in low mixing ratios (<6 Pa), acetate accumulated again, with a second concentration maximum on day 6 (521 ± 73 μM). Formate accumulated to concentrations of about 70 μM between days 9 and 11. CO2 mixing ratios increased logarithmically during the experiment, with final amounts reaching 9 kPa (data not shown).

Diversity of Archaea in rice field soil slurries.

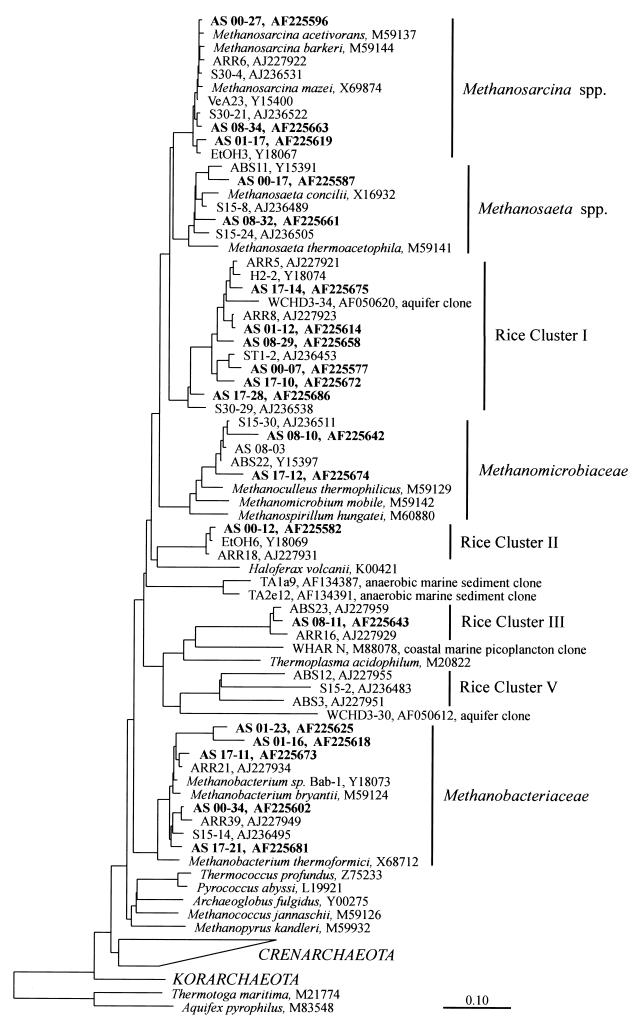

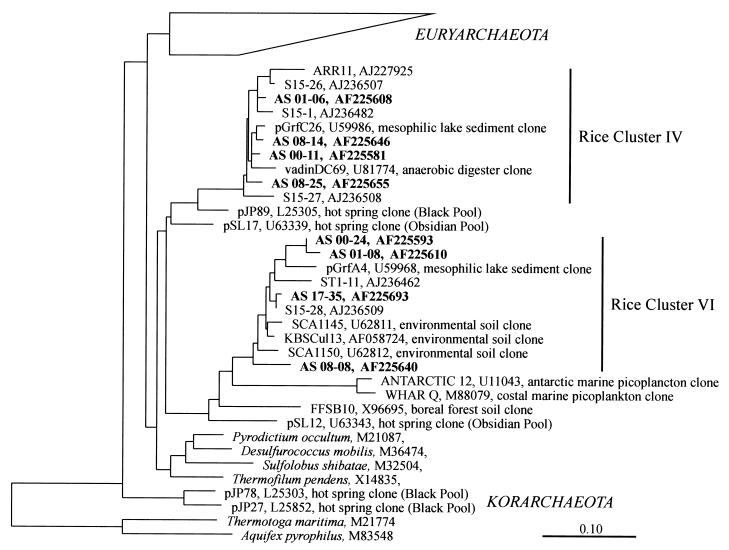

We constructed four clone libraries (days 0, 1, 8, and 17) of archaeal SSU rDNA fragments, which were PCR amplified from soil DNA, to assess the archaeal diversity present, identify dominant populations, and follow population dynamics during sequential reduction processes. More than 30 clones of each library were randomly selected and analyzed by comparative SSU rDNA sequencing. Within a total of 125 clones analyzed, 5 chimeric sequences were detected and excluded from further analyses. Phylogenetic placement of the nonchimeric clones revealed that they all fell within known eury- and crenarchaeotal lineages (Fig. 2 and 3), i.e., major methanogenic groups such as the Methanosarcinaceae, Methanosaetaceae, Methanomicrobiaceae, and Methanobacteriaceae, as well as the as yet uncultured Archaea assigned to RC-I, -II, -III, -IV, and -VI (9, 15, 16). Most clone sequences were closely related to archaeal rice field clones (>97% sequence similarity) reported earlier, but some phylogenetically more distant sequences were also detected. For example, the Methanosaeta-like clone AS 08-32 differed by more than 5% in sequence from its closest relative, S15-24 (9). Clone AS 08-10, grouping with the Methanomicrobiaceae, differed 6% from its closest relative S15-30, and clone AS 01-23 (Methanobacteriaceae) exhibited 6.5% sequence difference from ARR21 (15), an SSU rDNA clone from rice roots.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the placement of selected SSU rDNA clone sequences recovered from slurry samples after flooding of rice field soil (AS clones, days 0, 1, 8, and 17 [boldface]) within the Euryarchaeota. Selected sequences of cultivated representatives (nearly full-length rDNA) from euryarchaeotal lineages as well as environmental sequences (partial sequences) from Vercelli rice field soil (ABS, ARR, EtOH, H2, ST1, S15, and S30 clones) (9, 15, 16, 24) and other environments as indicated were used as references to construct an evolutionary-distance dendrogram. SSU rDNA sequences of A. pyrophilus and T. maritima as well as members of the Cren- and Korarchaeota were used as outgroup references. The scale bar represents 10% sequence difference. GenBank accession numbers of sequences are indicated.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree showing the positions of SSU rDNA clone sequences (AS clones, days 0, 1, 8, and 17 [boldface]) recovered from slurry samples after flooding within the Crenarchaeota. See the legend to Fig. 2 for details.

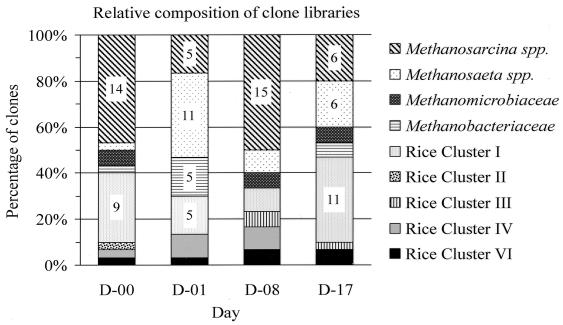

The four clone libraries showed significant differences in relative archaeal population structures over time (Fig. 4). On day 0, immediately after flooding, populations related to Methanosarcina spp. (47%) and RC-I (30%) appeared to be predominant. Other groups were represented by only one or two clones, while no RC-III clone was found at all. On day 1, Methanosaeta spp. accounted for the largest number of clones (37%), Methanosarcina spp., Methanobacteriaceae, and RC-I represented 17% each, and the crenarchaeotal RC-IV represented 10%. One clone could be affiliated with RC-VI, while the remaining groups were not detected. On day 8 Methanosarcina spp. dominated (50%), whereas no other group exceeded a proportion of 10%. Interestingly, two clones of RC-III appeared, while no Methanobacteriaceae clone could be found. Finally, on day 17, a more balanced distribution of the major groups reappeared, 37% RC-I and 20% each Methanosarcina spp. and Methanosaeta spp. clones.

FIG. 4.

Community structure of Archaea in soil samples from four different time points (days 0, 1, 8, and 17) after flooding of rice field soil as analyzed by the abundance of SSU rDNA clones affiliated with major phylogenetic lineages. Each library contained 30 clones.

Phylotype richness.

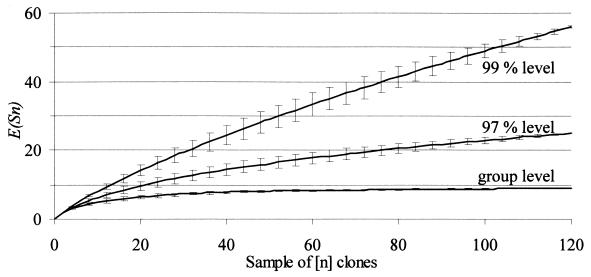

The analysis of total community diversity by cloning approaches may be biased by undersampling (43). Therefore, we determined the diversity coverage of our archaeal SSU rDNA clone libraries by rarefaction analysis (18). This calculation allows the determination of the number of clones necessary to cover the expected number of species E(Sn) in a sample of n individuals selected at random from a community containing N individuals and S species. Since SSU rDNA clones in this study originated from the same soil, we combined all clones sampled at different time points with the rationale of estimating the total archaeal diversity in the soil independent of community structure shifts over time. The expected number of different SSU rDNA sequences was plotted against the number of clones retrieved (Fig. 5). We defined sequences with >99% sequence similarity (<8 different nucleotides per ∼800 bp of SSU rDNA fragment) as belonging to the same species. However, even SSU rDNA sequences differing up to 3% may represent a single species (42). Therefore, rarefaction calculations were performed at both the 99% and 97% sequence similarity levels. Species rarefaction calculations for 120 clones reached saturation at neither 99% (56 different species) nor 97% (25 different species) sequence similarity levels, indicating undetected archaeal diversity. The SSU rDNA sequences detected in our clone libraries fell into nine major clone groups (Fig. 4). By plotting the expected number of groups against the number of SSU rDNA clones retrieved, rarefaction calculations were shown to approach saturation at 120 clones, indicating sufficient diversity coverage at this level of resolution. According to these calculations, a random sample of 30 clones may contain seven to eight of the different major lineages, and in fact we detected six, seven, seven, and eight groups in the four clone libraries.

FIG. 5.

Rarefaction analysis of the 120 archaeal SSU rRNA clones from rice field soil slurry samples (days 0, 1, 8, and 17). Calculations were performed at the species (99 and 97% sequence similarity) and group level. The archaeal groups were identical to those indicated in Fig. 4. Error bars indicate the variance of the expected number of species, E(Sn).

T-RFLP analysis.

It is well known that analysis of the microbial community structure by cloning may be biased (43, 45). Thus, the significant changes in archaeal community structure as detected by clone frequencies during sequential reduction processes may have been subject to cloning biases as well. Therefore, we analyzed PCR-amplified SSU rDNA fragments directly by T-RFLP to monitor archaeal community structure changes.

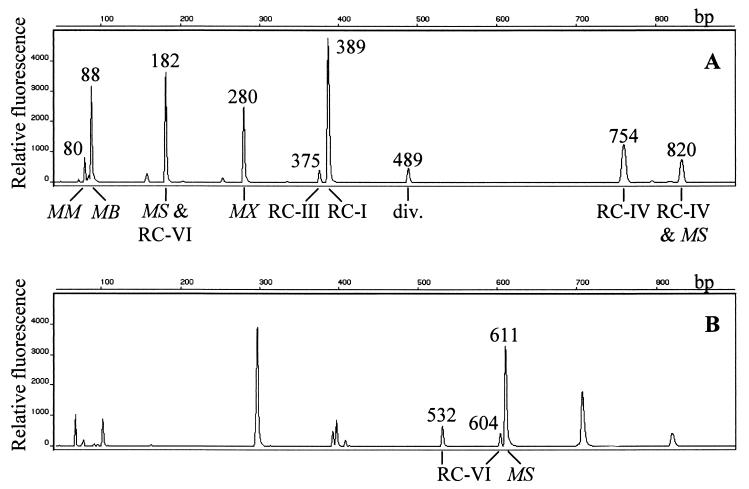

Analysis of community structures by T-RFLP results in a pattern of T-RFs that may be unrelated to the phylogeny of the SSU rDNA sequences studied, i.e., sequences with different group affiliations can be represented in the same operational taxonomic unit (OTU) (27). Therefore, we analyzed 267 archaeal clones obtained from Vercelli rice field samples in this study and in independent previous studies (9, 15, 16, 24) for group-specific TaqI restriction sites by sequence data comparison. The combined data set revealed a high degree of conservation of different group-specific restriction sites within the abundant and also within some of the less abundant clone groups (Table 1). For example, 95% of 77 Methanosarcina-like clones exhibited a 182-bp T-RF, 97% of 35 Methanosaeta-like clones showed a common T-RF of 280 bp, and 89% of 62 RC-I clones exhibited a 389-bp T-RF. Unfortunately, each of the three most frequent clone groups exhibited a common T-RF with one of the less frequent groups. Methanosarcina-like and RC-VI clones mainly shared a T-RF of 182 bp (9), Methanosaeta-like and RC-V clones exhibited a common 280-bp T-RF, and the majority of the RC-I and RC-II clones contributed to the 389-bp OTU. However, of the 120 clones analyzed in this study, only 1 (AS 00-12) fell within RC-II and none fell within RC-V. Thus, the 280-bp and 389-bp OTUs predominantly represented Methanosaeta-like and RC-I SSU rDNA sequences, respectively, and only to a negligible extent RC-II and RC-V sequences. In contrast, although Methanosarcina-like clones were clearly most abundant (40 of 120 clones), small numbers of the crenarchaeotal RC-VI clones were present in all clone libraries (n = 6), and therefore this population was likely to be represented in the 182-bp OTU. A typical archaeal community fingerprint obtained by T-RFLP analysis of SSU rDNA amplicons of slurry DNA is shown in Fig. 6A. All OTUs predicted by sequence data analysis (Table 1) could be detected in the T-RFLP electropherogram and assigned to the corresponding archaeal lineages.

TABLE 1.

Frequency of archaeal SSU rDNA clones retrieved from a methanogenic Italian rice field soil with distinct T-RFs and their association with archaeal lineagesa

| T-RF (bp) | No. of SSU rDNA clones

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanosarcinaceae | Methanosaetaceae | Methanomicrobiaceae | Methanobacteriaceae | RC-I | RC-II | RC-III | RC-IV | RC-V | RC-VI | |

| 34 | 1 | |||||||||

| 45 | 1 | |||||||||

| 74 | 2 | |||||||||

| 80 | 9 | |||||||||

| 88 | 18 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| 182 | 73 | 1 | 1 | 22 | ||||||

| 280 | 34 | 5 | ||||||||

| 366 | 2 | |||||||||

| 375 | 6 | |||||||||

| 389 | 1 | 55 | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| 489 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||

| 754 | 6 | |||||||||

| 820 | 4 | 1 | 12 | |||||||

| Total | 77 | 35 | 10 | 20 | 62 | 5 | 6 | 19 | 8 | 25 |

Sequence data are from this study (120 clones obtained on days 0, 1, 8, and 17; Fig. 4) and from previous studies (9, 15, 16, 24). The lengths of restriction fragments were predicted from aligned sequence data, assuming a labeled Ar912r primer. The numbers of clones within the different phylogenetic lineages exhibiting a certain T-RF are indicated. Conserved group-specific T-RFs are in bold.

FIG. 6.

Typical T-RFLP electropherograms of archaeal SSU rDNA amplicons from a rice field slurry sample on day 1 after flooding. Fingerprints were generated using FAM-labeled primers Ar912r (A) and Ar109f (B). The archaeal lineages represented in different OTUs are Methanobacteriaceae (MB), Methanomicrobiaceae (MM), Methanosarcinaceae (MS), Methanosaetaceae (MX), and RC-I to RC-VI. T-RF lengths of selected peaks (in base pairs) are indicated.

Population dynamics of Archaea.

Direct T-RFLP analysis was performed with PCR amplicons from soil DNA extracts for all time points of our slurry experiment. By integrating the fluorescence intensity of the different OTUs, relative archaeal SSU rRNA gene frequencies were quantified (Fig. 7). The major archaeal groups detected via T-RFLP analysis were identical to the most abundant lineages found in clone libraries, e.g., Methanosarcinaceae, RC-I, and Methanosaetaceae. But while the clone libraries displayed large shifts in relative composition over time (see above, Fig. 4), gene frequencies as determined by T-RFLP were rather constant, indicating a potential bias inherent in the procedure of cloning. Most prominent was the 389-bp OTU assigned to RC-I, but its frequency remained relatively constant over time, varying only between 30 and 35% of total archaeal gene frequency. The 182-bp OTU representing Methanosarcina-like and RC-VI populations was the only OTU which increased significantly in intensity during sequential reduction processes. A steady increase in the 182-bp OTU from 15% on day 0 to 29% of total archaeal gene frequency on day 13 was accompanied by an apparent relative decrease in especially the 88-bp, 389-bp, and 754-bp OTUs.

FIG. 7.

Archaeal population dynamics in rice field soil slurries as determined by T-RFLP analysis. The figure shows the integrated fluorescence of each individual OTU. T-RFLP fingerprints were generated with the Ar912r FAM-labeled primer. Archaeal lineages represented by the different OTUs are abbreviated as in Fig. 6. Data are means of replicate PCR analysis (n = 3). The average SD of single OTUs was below 1%.

Using a novel T-RFLP assay with the fluorescently labeled forward primer Ar109f, we succeeded in differentiating Methanosarcina-like and RC-VI populations. This approach resulted in a different T-RF pattern for the same archaeal community obtained in slurry soil samples (Fig. 6B). Most of the Methanosaeta-like and RC-I clones exhibited a common T-RF of 297 bp and therefore could not be separated, but highly conserved group-specific restriction sites were found within the Methanosarcina-like (611 bp) and RC-VI (532 and 604 bp) clones. Based on this novel T-RFLP assay, we observed that RC-VI gene frequencies equaled 1/3 of the Methanosarcinaceae gene frequencies on day 0, e.g., 25% of all amplicons represented in the 182-bp OTU. Over time, a doubling of the Methanosarcinaceae relative gene frequencies could be detected, while RC-VI frequencies decreased slightly. On day 17, RC-VI gene frequencies were only 1/6 of the Methanosarcinaceae gene frequencies, or 14% of the amplicons represented in the 182-bp OTU (using the Ar912r assay). Therefore, we concluded that the increase in the 182-bp OTU signal intensity was due to increasing Methanosarcinaceae gene frequencies within the first 13 days of incubation.

DISCUSSION

After flooding of rice field soils, methane production is typically initiated shortly after the reduction of electron acceptors such as nitrate, Fe3+, and sulfate. The sequence of these biogeochemical processes (metabolic activities) and the initiation of methane production observed in this study were in good agreement with previous reports (1, 39, 48, 49). Here, we focused on establishing a link between the observed changing biogeochemical processes (which ecosystem function) upon soil flooding to changes in archaeal populations, especially the methanogens (which species).

The different molecular approaches used resulted in pronounced differences in community composition determined during the initiation of methanogenesis. Analysis of SSU rDNA clone libraries (Fig. 4) suggested significant shifts in archaeal community compositions, whereas T-RFLP fingerprints exhibited a rather constant population structure when followed closely at daily intervals (Fig. 7). For example, after only 1 day of incubation, Methanosaeta-like and Methanobactericeae clones increased 10- and 5-fold in abundance, respectively. Subsequently, the same populations either decreased fourfold or disappeared completely after 7 days (Fig. 4).

Several lines of evidence suggest that most likely the cloning step was biased, resulting in large apparent fluctuations in the population structure. First, Methanosaeta spp. are characterized by slow growth (20). In fact, enumeration of acetotrophic methanogens in rice field soil required more than 40 weeks of incubation for the detection of these fastidious microorganisms (16). Although the in situ growth rates of these Archaea in soils are largely unknown, it is unlikely that the Methanosaeta-like populations increased 10-fold within 1 day in soil slurry experiments. Moreover, high concentrations of methanogenic substrates, such as acetate, present during the first 8 days of incubation (Fig. 1B) are known to be more favorable for development of the faster-growing Methanosarcina spp., which are adapted to higher acetate concentrations than are Methanosaeta spp. (20).

The strongest argument for a cloning bias, however, results from the comparison of the two methods employed in this study, cloning and T-RFLP analysis of SSU rDNA PCR products. We observed large shifts in community structure only with the cloning approach. Likewise, large fluctuations in archaeal SSU rDNA sequence abundances in clone libraries were observed in a recent study of archaeal communities before and after a temperature shift in methanogenic rice field soil (9). Again, T-RFLP analysis revealed less pronounced differences in community structure than were suggested by cloning analysis. On the other hand, in a study of a bioreactor sample, a combination of cloning and subsequent analysis of clones by ARDRA performed in three replications suggested that cloning appeared to be rather reproducible (12).

Several factors possibly influencing the abundance of sequences in clone libraries have been pinpointed, especially the PCR and the cloning procedure itself (for a review, see reference 45).

We cannot exclude an underlying PCR bias possibly affecting both methods, cloning and T-RFLP, because both methods rely virtually on the same PCR protocol (with the exception that primer Ar912r was fluorescently labeled for T-RFLP). Since the observed large fluctuations in community composition over time were restricted to cloning analysis, we were prompted to conclude that the cloning step in particular was subject to bias.

Possible bias related only to the cloning procedure may be attributed to random error resulting from undersampling of diversity (43), toxicity of vector inserts to the transformed host, or the choice of cloning kit. Rainey et al. (unfortunately, no original data were provided in this short communication [37]) reported differences in SSU rDNA clone library composition depending on the cloning system used, i.e., blunt-end versus sticky-end cloning. In our study we used TA cloning for separating SSU rDNA PCR products amplified from environmental samples. Although widely used (34), the influence of bias related to this cloning protocol has not yet been analyzed with respect to the sequence distribution in SSU rDNA clone libraries.

Despite the principal caveat that clone abundance in libraries does not necessarily reflect population abundance in environmental samples (17), our SSU rDNA clone libraries contained valuable information about the sequence diversity of Archaea in rice field soil at different time points (i.e., days 0, 1, 8, and 17) after flooding. We detected most of the archaeal groups (Methanosarcinaceae, Methanosaetaceae, Methanomicrobiaceae, Methanobacteriaceae, RC-I to -IV, and RC-VI) detected previously in studies of rice field soils from Vercelli focusing either on the diversity (15, 16, 24) or on community structure changes after a temperature shift (9). We failed to detect sequences related to the novel RC-V previously shown to be present in bulk soil of 90-day-old microcosms (15). However, it is still unknown whether RC-V as well as the other as yet uncultured Archaea assigned to RC-I to -VI (15, 16) are methanogenic. Their relevance during the initiation of methanogenesis in rice field soil remains to be elucidated. It is striking that although the soil was sampled in different years and certainly not at exactly the same site near the Vercelli Rice Research Institute, the majority of our SSU rDNA clones were closely related or even identical to previously reported archaeal sequences. Only a few clones were more distantly related, with up to 7% sequence differences from their closest previously reported relatives.

As indicated by rarefaction analysis, our clone libraries (n = 120) did not fully cover the phylotype richness of Archaea in Vercelli rice field soil (Fig. 5). However, rarefaction analysis focusing on the level of lineages detected revealed that it was unlikely to detect sequences representing additional or novel archaeal lineages (Fig. 5). Moreover, the high similarities of our SSU rDNA sequences to those from previous studies on Vercelli rice field soil also suggested that we would not detect novel phylotypes by analyzing additional clones.

By using a large data set comprising 267 clones from our study and those obtained with a similar PCR assay in the previous studies mentioned above, we were able to confirm previously detected restriction sites for the major phylogenetic lineages present in Vercelli rice field soil (Table 1) (9). Moreover, we could show a high degree of conservation of group-specific T-RFs for most of the lineages present (Table 1). For example, 95% of frequently found clones related to Methanosarcina spp. had a T-RF of 182 bp and 89% of all RC-I clones had a T-RF of 389 bp. On the other hand, clones related to Methanosarcina spp. shared the 182-bp T-RF with RC-VI clones. These RC-VI clones were also a frequent group and thus had to be considered for the analysis of relative gene frequency of this OTU.

We emphasize that the group specificity of restriction sites described here is valid only in the context of sequences retrieved from the same environment. Other sequences not detected in Vercelli rice field soil by PCR or cloning and belonging to other taxonomic groups may share common restriction sites with sequences retrieved from rice field soil samples (e.g., Methanospirillum sp. and RC-I) due to the conserved nature of the SSU rRNA gene. Knowing these limitations but equipped with the detected degree of conservation of TaqI restriction sites, we were able to expand the utility of the T-RFLP analysis considerably.

All predicted OTUs were actually found in direct T-RFLP analysis of slurry samples. For analyzing archaeal population dynamics, we extended the T-RFLP analysis from a qualitative assessment of OTUs to a quantitative assessment of relative gene frequencies by integrating peak areas of individual OTUs. T-RFLP analysis was highly reproducible, as indicated by the relatively constant gene frequencies of most OTUs measured at daily intervals over 17 days (Fig. 7). PCR replications (n = 3) were also highly reproducible, as indicated by a low average standard deviation (SD) (<1%) for all T-RFs. A similar approach was used successfully by Suzuki et al. (43) to determine relative gene frequencies of fluorescently labeled SSU rDNA PCR fragments of different lengths.

In general, the relative gene frequency of most detected OTUs (Fig. 7) remained rather constant over time during the first 17 days after flooding of the soil. Most minor populations (i.e., Methanomicrobiaceae and RC-III) and Methanosaetaceae apparently did not change at all in frequency. Notably RC-I (37 to 30%) and to a lesser extent RC-IV as well as Methanobacteriaceae gene frequencies decreased over time. The remarkable stability of the archaeal populations after the flooding of the soil is in contrast to the changes in environmental parameters such as redox potential (40), availability of electron acceptors (Fig. 1A), and availability of electron donors such as acetate and hydrogen (Fig. 1B). Denitrification intermediates were probably too low in concentration in our slurry experiments to affect methanogenesis by nitrogen oxide inhibition (21), as indicated by the low initial nitrate concentration (<116 μM).

The most striking point was the significant increase in relative gene frequency of the 182-bp OTU comprising Methanosarcinaceae and RC-VI populations from 15 to 29% over 13 days (Fig. 7). By using a novel T-RFLP assay (i.e., with the fluorescently labeled primer Ar109f) (Fig. 6B), which allowed the differentiation of these two groups, we could demonstrate that in fact only the relative gene frequencies of the Methanosarcinaceae increased. Theoretically, we have to consider that an increase in relative gene frequency of the Methanosarcinaceae could be linked to a decrease in the absolute gene frequencies of the other populations, caused, for instance, by predatory protozoa (11) and phages (4). However, it is more likely that growth of Methanosarcina-like populations occurred because of the energetically permissive concentrations of acetate and hydrogen during the initiation of methanogenesis (Fig. 1B). We detected a similar temporal pattern of community structure change in a study analyzing the effect of soil aggregate size on the initiation of methanogenesis (37a). By T-RFLP analysis, Chin et al. (9) also detected an increase in the OTU comprising Methanosarcinaceae and RC-VI upon anoxic incubation of methanogenic rice field soil and an even stronger increase in the RC-I-related OTU. The different incubation temperature (30°C) used in their study as well as other factors (i.e., soil sample, acetate accumulation to higher values, and lower methane production rate) may be responsible for differences in community structure changes from what was found in our study.

After the complete reduction of sulfate (day 4), acetate concentrations accumulated to a second maximum of about 600 μM around day 6, whereas hydrogen concentrations remained below 6 Pa. Apparently, the acetotrophic activity of methanogens was the limiting factor during the initiation of methanogenesis and led to the observed accumulation of acetate. This is in agreement with results from methyl fluoride inhibition experiments in anoxic rice field soil, which suggested that hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis dominates the initial phase of methane production (40). In addition, Chidthaisong and Conrad (7) also reported that acetate utilization by methanogens was slower than acetate production from glucose in rice field soil during the reduction phase (i.e., in the presence of sulfate and Fe3+). The second increase in acetate concentration was well correlated with the steady increase in the Methanosarcinaceae OTU (Fig. 7). From day 6 on, acetate concentrations decreased consistent with acetotrophic methanogenesis, e.g., by Methanosarcina spp.

Another important observation with respect to a link between metabolic activity and population dynamics was that the Methanosarcinaceae still increased (day 13; Fig. 7) when pore water concentrations of acetate (Fig. 1B) were well below the known threshold (>200 to 300 μM) for growth of Methanosarcina spp. Methanosaetaceae populations apparently could not benefit from their lower threshold for acetate and grow, as indicated by constant gene frequencies of the 280-bp T-RF. Most likely, the versatile Methanosarcina spp. switched to other electron donors, such as hydrogen or methanol (not measured). Interestingly, formate was present in a concentration of up to 120 μM between days 9 and 13 (Fig. 1B), and Methanosarcinaceae did not increase further after formate was depleted below the detection limit. Although formate cannot be utilized by the known Methanosarcina spp., formate is probably in equilibrium with H2/CO2 as catalyzed by fermentative bacteria.

Typically, only small amounts of methane are formed, probably from H2/CO2, during the initiation of methanogenesis (40, 48). The small amounts of methane (∼0.56 μmol; Fig. 1B) that we detected during the first 3 days after flooding of the soil are contradicted by a significant increase in gene frequency (∼4%) of Methanosarcina-like populations. The small amounts of methane formed were probably not sufficient to explain the observed increase in Methanosarcina-like populations by de novo growth. Further investigations are necessary to find out which methanogens actually become active during the important phase of initiation of methanogenesis. In a forthcoming study, we will therefore address this question by targeting directly the rRNA of Archaea. The rRNA content of cells is generally accepted as an indicator of the metabolic activity of microbial populations.

In summary, we observed that the population structure of Archaea remained remarkably constant over time after flooding of rice field soil. Only Methanosarcina-like populations increased significantly in gene frequency relative to the other populations. Probably due to a high organic matter content of the soil utilized, fermentation processes were vigorous. This was indicated by the initially high levels of acetate and hydrogen (day 1, Fig. 1). These conditions were obviously favorable for Methanosarcina-like populations. Even the switch from hydrogenotrophic to acetotrophic methanogenesis was apparently not accompanied by a population shift but instead by a shift in activity of the Methanosarcina-like populations, indicating that the same population could manage different ecosystem functions. We conclude that a functionally extremely dynamic ecosystem, a flooded rice field soil, was linked to a relatively stable archaeal community structure. This is in agreement with the temporal stability of the population structure observed in other environments such as cyanobacterial hot spring mats (13) as well as oxic (19) and anoxic rice field soils (9, 37a). On the other hand, ecosystems such as an apparently functionally stable methanogenic bioreactor fed with glucose may exhibit an extremely dynamic community structure (12), indicating that a general principle for microbial community dynamics relative to ecosystem function is not yet feasible.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) within the SFB395 and the Max-Planck-Society.

We thank Bianca Wagner for excellent technical assistance, Peter F. Dunfield for English language suggestions, and Ralf Conrad for continuing support. We are indebted to Steven M. Holland for providing the Analytical Rarefaction 1.2 software, available at http://www.uga.edu/∼strata/Software.html.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtnich C, Bak F, Conrad R. Competition for electron donors among nitrate reducers, ferric iron reducers, sulfate reducers, and methanogens in anoxic paddy soil. Biol Fertil Soils. 1995;19:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asakawa S, Hayano K. Populations of methanogenic bacteria in paddy field soil under double cropping conditions (rice-wheat) Biol Fertil Soils. 1995;20:113–117. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashelford K E, Day M J, Bailey M J, Lilley A K, Fry J C. In situ population dynamics of bacterial viruses in a terrestrial environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:169–174. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.1.169-174.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bak F, Scheff G, Jansen K H. A rapid and sensitive ion chromatographic technique for the determination of sulfate and sulfate reduction rates in fresh-water lake-sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1991;85:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson D A, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman D J, Ostell J, Rapp B A, Wheeler D L. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:15–18. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chidthaisong A, Rosenstock B, Conrad R. Measurement of monosaccharides and conversion of glucose to acetate in anoxic rice field soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2350–2355. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2350-2355.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin K J, Conrad R. Intermediary metabolism in methanogenic paddy soil and the influence of temperature. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1995;18:85–102. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin K J, Lukow T, Conrad R. Effect of temperature on structure and function of the methanogenic archaeal community in an anoxic rice field soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2341–2349. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2341-2349.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conrad R. Soil microorganisms as controllers of atmospheric trace gases (H2, CO, CH4, OCS, N2O, and NO) Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:609–640. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.4.609-640.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couteaux M M, Darbyshire J F. Functional diversity amongst soil protozoa. Appl Soil Ecol. 1998;10:229–237. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez A, Huang S Y, Seston S, Xing J, Hickey R, Criddle C, Tiedje J M. How stable is stable? Function versus community composition. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3697–3704. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3697-3704.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferris M J, Ward D M. Seasonal distributions of dominant 16S rRNA-defined populations in a hot spring microbial mat examined by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1375–1381. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1375-1381.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fetzer S, Conrad R. Effect of redox potential on methanogenesis by Methanosarcina barkeri. Arch Microbiol. 1993;160:108–113. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grosskopf R, Stubner S, Liesack W. Novel euryarchaeotal lineages detected on rice roots and in the anoxic bulk soil of flooded rice microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4983–4989. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4983-4989.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grosskopf R, Janssen P H, Liesack W. Diversity and structure of the methanogenic community in anoxic rice paddy soil microcosms as examined by cultivation and direct 16S rRNA gene sequence retrieval. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:960–969. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.960-969.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Head I M, Saunders J R, Pickup R W. Microbial evolution, diversity, and ecology: a decade of ribosomal RNA analysis of uncultivated microorganisms. Microb Ecol. 1998;35:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s002489900056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heck K L, Jr, Van Belle G, Simberloff D. Explicit calculation of the rarefaction diversity measurement and the determination of sufficient sample size. Ecology. 1975;56:1459–1461. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henckel T, Friedrich M, Conrad R. Molecular analyses of the methane-oxidizing microbial community in rice field soil by targeting the genes of the 16S rRNA, particulate methane monooxygenase, and methanol dehydrogenase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1980–1990. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1980-1990.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jetten M S M, Stams A J M, Zehnder A J B. Methanogenesis from acetate—a comparison of the acetate metabolism in Methanothrix soehngenii and Methanosarcina spp. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;88:181–197. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klüber H D, Conrad R. Inhibitory effects of nitrate, nitrite, NO and N2O on methanogenesis by Methanosarcina barkeri and Methanobacterium bryantii. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;25:331–339. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kopczynski E D, Bateson M M, Ward D M. Recognition of chimeric small-subunit ribosomal DNAs composed of genes from uncultivated microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:746–748. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.746-748.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krumbock M, Conrad R. Metabolism of position-labelled glucose in anoxic methanogenic paddy soil and lake sediment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1991;85:247–256. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehmann-Richter S, Grosskopf R, Liesack W, Frenzel P, Conrad R. Methanogenic Archaea and CO2-dependent methanogenesis on washed rice roots. Environ Microbiol. 1999;1:159–166. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lelieveld J, Crutzen P J, Dentener F J. Changing concentration, lifetime and climate forcing of atmospheric methane. Tellus Ser B Chem Phys Meteorol. 1998;50:128–150. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liesack W, Janssen P H, Rainey F A, Ward-Rainey N L, Stackebrandt E. Microbial diversity in soil: the need for a combined approach using molecular and cultivation techniques. In: van Elsas J D, Trevors J T, Wellington E M H, editors. Modern soil microbiology. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1997. pp. 375–439. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W T, Marsh T L, Cheng H, Forney L J. Characterization of microbial diversity by determining terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms of genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4516–4522. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4516-4522.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludwig W, Bauer S H, Bauer M, Held I, Kirchhof G, Schulze R, Huber I, Spring S, Hartmann A, Schleifer K H. Detection and in situ identification of representatives of a widely distributed new bacterial phylum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;153:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludwig W, Strunk O, Klugbauer S, Klugbauer N, Weizenegger M, Neumaier J, Bachleitner M, Schleifer K H. Bacterial phylogeny based on comparative sequence analysis. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:554–568. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayer H P, Conrad R. Factors influencing the population of methanogenic bacteria and the initiation of methane production upon flooding of paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1990;73:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moré M I, Herrick J B, Silva M C, Ghiorse W C, Madsen E L. Quantitative cell lysis of indigenous microorganisms and rapid extraction of microbial DNA from sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1572–1580. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1572-1580.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patrick W H, Jr, Reddy C N. Chemical changes in rice soils. Los Banos, Phillipines: International Rice Research Institute; 1978. pp. 361–379. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters V, Conrad R. Sequential reduction processes and initiation of CH4 production upon flooding of oxic upland soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28:371–382. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pitulle C, Pace N R. T-cloning vector for plasmid-based 16S rDNA analysis. Biotechniques. 1999;26:222–224. doi: 10.2144/99262bm08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ponnamperuma F N. The chemistry of submerged soils. Adv Agron. 1972;24:29–96. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prinn R G, editor. Global atmospheric-biospheric chemistry. New York, N.Y: Plenum; 1994. Global atmospheric-biospheric chemistry; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rainey F A, Ward N, Sly I, Stackebrandt E. Dependence on the taxon composition of clone libraries for PCR amplified, naturally occurring 16S rDNA, on the primer pair and the cloning system used. Experientia. 1994;50:796–797. [Google Scholar]

- 37a.Ramakrishnan, B., T. Lueders, R. Conrad, and M. Friedrich. Effect of soil aggregate size on methanogenesis and archaeal community structure in anoxic rice field soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Rotthauwe J H, Witzel K P, Liesack W. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4704–4712. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4704-4712.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy R, Conrad R. Effect of methanogenic precursors (acetate, hydrogen, propionate) on the suppression of methane production by nitrate in anoxic rice field soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1999;28:49–61. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy R, Klüber H D, Conrad R. Early initiation of methane production in anoxic rice soil despite the presence of oxidants. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;24:311–320. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schink B. Syntrophism among prokaryotes. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K-H, editors. The prokaryotes. New York, N.Y: Springer; 1992. pp. 276–299. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stackebrandt E, Goebel B M. Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:846–849. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki M T, Rappe M S, Giovannoni S J. Kinetic bias in estimates of coastal picoplankton community structure obtained by measurements of small-subunit rRNA gene PCR amplicon length heterogeneity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4522–4529. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4522-4529.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tiedje J M, Asuming-Brempong S, Nusslein K, Marsh T L, Flynn S J. Opening the black box of soil microbial diversity. Appl Soil Ecol. 1999;13:109–122. [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Wintzingerode F, Goebel U B, Stackebrandt E. Determination of microbial diversity in environmental samples—pitfalls of PCR-based rRNA analysis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;21:213–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang G C Y, Wang Y. Frequency of formation of chimeric molecules is a consequence of PCR coamplification of 16S rRNA genes from mixed bacterial genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4645–4650. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4645-4650.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward D M, Bateson M M, Weller R, Ruff-Roberts A L. Ribosomal rRNA analysis of microorganisms as they occur in nature. Adv Microb Ecol. 1992;12:219–286. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao H, Conrad R. Thermodynamics of methane production in different rice paddy soils from China, the Philippines and Italy. Soil Biol Biochem. 1999;31:463–473. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao H, Conrad R, Wassmann R, Neue H U. Effect of soil characteristics on sequential reduction and methane production in sixteen rice paddy soils from China, the Philippines, and Italy. Biogeochemistry. 1999;47:269–295. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zehnder A J B, Stumm W. Geochemistry and biogeochemistry of anaerobic habitats. In: Zehnder A J B, editor. Biology of anaerobic microorganisms. New York, N.Y: Wiley; 1988. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]