Abstract

Objectives and Methods:

We conducted a population-based study including 19,303 individuals diagnosed with MGUS in Sweden from 1985 to 2013, with the aim to determine whether a prior history of autoimmune disease, a well-described risk factor for MGUS) is a risk factor for progression of MGUS to multiple myeloma (MM) or lymphoproliferative diseases (LPs). Using the nationwide Swedish Patient registry, we identified MGUS cases with versus without an autoimmune disease present at the time of MGUS diagnosis and estimated their risk of progression.

Results:

A total of 5,612 (29.1%) MGUS cases had preceding autoimmune diseases. Using Cox proportional hazards models, we found the risk of progression from MGUS to MM (HR=0.83, 95% CI 0.73–0.94) and LPs (HR=0.84, 95% CI 0.75–0.94) to be significantly lower in MGUS cases with prior autoimmune disease (compared to MGUS cases without).

Conclusions:

In this large population-based study, a history of autoimmune disease was associated with a reduced risk of progression from MGUS to MM/other LPs. Potential underlying reason is that MGUS caused by chronic antigen stimulation is biologically less likely to undergo the genetic events that trigger progression. Our results may have implications in clinical counselling for patients with MGUS and underlying autoimmune disease.

Introduction

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is a plasma cell disorder defined by the presence of serum M-protein less than 3 g/dL, clonal plasma cell proliferation in the bone marrow of less than 10%, and the absence of end-organ damage such as hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia and lytic bone lesions.1,2 Studies in recent years have shown its prevalence to be between 2.1 and 5.8% in the general population, with the highest prevalence in Africans and African-Americans and the lowest in Asians.3–8 MGUS is a premalignant condition that has been shown to consistently precede multiple myeloma (MM), 9,10 with around 1–1.5% progressing to MM or another lymphoproliferative disorder (LP) each year.11 The need to identify prognostic factors to guide follow-up is clear. Current risk models for progression to MM or other LPs include M-protein levels >1.5 g/dL, non-IgG MGUS, and pathological free light chain (FLC) ratio.11–14 Other factors, such as amount of marrow plasma cells, urinary paraprotein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and results of multiparametric flow cytometry, have also been shown to have prognostic value.15,16

Several authors have demonstrated an association of MGUS and MM with autoimmune diseases.17,18 We have previously found a significantly increased risk of MGUS, but not of MM, in those with any prior autoimmune disease. However, risk of MM was found to be increased in those with a personal history of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, polymyalgia rheumatica, and giant cell arteritis.19 The underlying biological mechanisms for these observations are not entirely clear but it has been hypothesized to stem from a mutual genetic susceptibility or chronic antigen stimulation triggering the development of a plasma cell dyscrasias20 as has been reported in lymphomas.21,22

To our knowledge, no large population-based studies have been conducted to estimate the effect of a prior history of autoimmune disease on the rate of progression of MGUS to MM or LPs. We were motivated to design and conduct a population-based study using data from over 19,000 MGUS cases and with almost 30 years of follow-up. The aim of our study was to determine whether a prior history of autoimmune disease is a risk factor for progression of MGUS to MM/related LPs.

Methods

Data collection

Information on patients with MGUS was collected through a national network which included all outpatient units in major hematology and oncology wards in Sweden. Additionally, individuals with MGUS reported in the Swedish Patient Register were identified. The Swedish Patient Register contains information on the discharge diagnoses of inpatient (since 1964) and outpatient (since 2001) care and has been shown to be very accurate and to have good coverage.23,24 Patients diagnosed with MGUS between January 1st 1985 and December 31st 2013 were included in the study.

Data on patients diagnosed with MM and other LPs was acquired through the nationwide Swedish Cancer Register. Since 1958, all pathologists/cytologists and physicians in Sweden have been required to report each case of cancer diagnosed or treated to this Register. It’s accuracy has been found to be over 93% for patients with MM diagnosed between 1964 and 2003, and to be over 95% for LPs.25

Information on any immune related condition for each of the patients with MGUS was acquired through the Swedish Patient Register, which includes patients diagnosed in standard clinical settings. The condition was not required to be the primary diagnosis. Codes for specific autoimmune diseases were retrieved from the 8th, 9th and 10th revisions of the International Classification of Diseases. The conditions included in the analyses were in accordance with previously published studies.22,26 In concurrence with a previous study autoimmune diseases were classified by whether autoantibodies were detectable and by whether diseases were organ specific or systemic (Appendix 1).26

An approval for the study was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm.

Statistical analysis

Risk of progression to MM or all LPs for those with MGUS and an autoimmune disease at the time of diagnosis of MGUS was compared to the risk of progression for those with MGUS without prior autoimmune disease. Those with a prior history of LPs, those less than 30 years old at the time of diagnosis of MGUS and those who were deceased at the time of diagnosis of MGUS were excluded from the study. Additionally, if information on age at diagnosis of MGUS was not available, those individuals were excluded from calculations. Those who were diagnosed with MGUS and an autoimmune disease on the same day were treated as if they had autoimmune disease prior to MGUS. To calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for risk of progression we used the Cox proportional hazards model. Results were adjusted for age, sex, and year of MGUS diagnosis. Analyses were made on three subgroups of autoimmune diseases;19,26,27 autoantibodies not detectable, organ involvement and systemic involvement, as well as by concentration and type of M-protein. Risk of progression to both MM and all LPs was calculated and stratified by gender, age (above and below 70 years), M-protein concentration (above and below 1.5 g/dL), and year of diagnosis (before and after 1993) using the Cox proportional hazards model. Risk of progression to MM and all LPs was also adjusted for M-protein type and concentration and these calculations were corrected for age, gender and year of MGUS diagnosis. The predicted survival function of the corrected Cox proportional hazard model was used to estimate the progression risk for those with and without autoimmune disease at the time of diagnosis. These results were corrected for age, gender, and year of diagnosis. as done in a study by Kyle et al. from 2002.11 Those who progressed within two weeks of MGUS diagnosis were excluded from these calculations. Additionally, the Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate the risk of progression for 39 specific autoimmune diseases (Appendix 1). Calculations for autoimmune diseases when fewer than three had progressed from MGUS to MM or other LPs are not shown due to lack of statistical power.

Results

A total of 19,303 patients with MGUS diagnosed between January 1st, 1985 and December 31st, 2013 were included in the study. Median age at the time of diagnosis was 72 years for those who had no autoimmune disease (range 30–101) and 72 for those with any autoimmune disease (range 30–99 years). Demographic data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Characteristics of patients included in the study

| Total (n=19,303) | No autoimmune disease (n=13,691) | Any autoimmune disease (n=5,612) |

Autoantibody not detected✣ (n=2,580) | Organ involvement ✣(n=2,720) | Systemic involvement✣ (n=1,271) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 9,322 | 6,450 | 2,872 | 1,320 | 1,297 | 814 |

| Median age at diagnosis (range) | 72 | 72 (30–101) | 72 (30–99) | 72 (30–97) | 72 (30–97) | 72 (30–93) |

| Age group at diagnosis | ||||||

| 30–60 years | 3,652 | 2,663 | 989 | 448 | 454 | 277 |

| 61–70 years | 4,470 | 3,080 | 1,390 | 647 | 656 | 341 |

| 71–80 years | 6,296 | 4,412 | 1,884 | 841 | 944 | 409 |

| >81 years | 4,885 | 3,536 | 1,349 | 644 | 666 | 244 |

See appendix 1

A total of 5,612 (29.1%) patients had an autoimmune disease at the time of MGUS diagnosis. A total of 2,351 progressed to MM or other LPs. Information on the amount of M-protein was available for 17.9% of patients in the study. Mean level of M-protein was 1.11 g/dL. A significantly lower level of M-protein was found for those with autoimmune disease (0.97 g/dL) compared to those without (1.13 g/dL) (p=0.005). Information on the type of M-protein was available in 21.6% of cases. Patients with prior autoimmune disease had a non-significantly higher prevalence of IgG isotype (65.5%) compared to those without (61.4%).

Risk of progression by autoimmune disease and subgroups

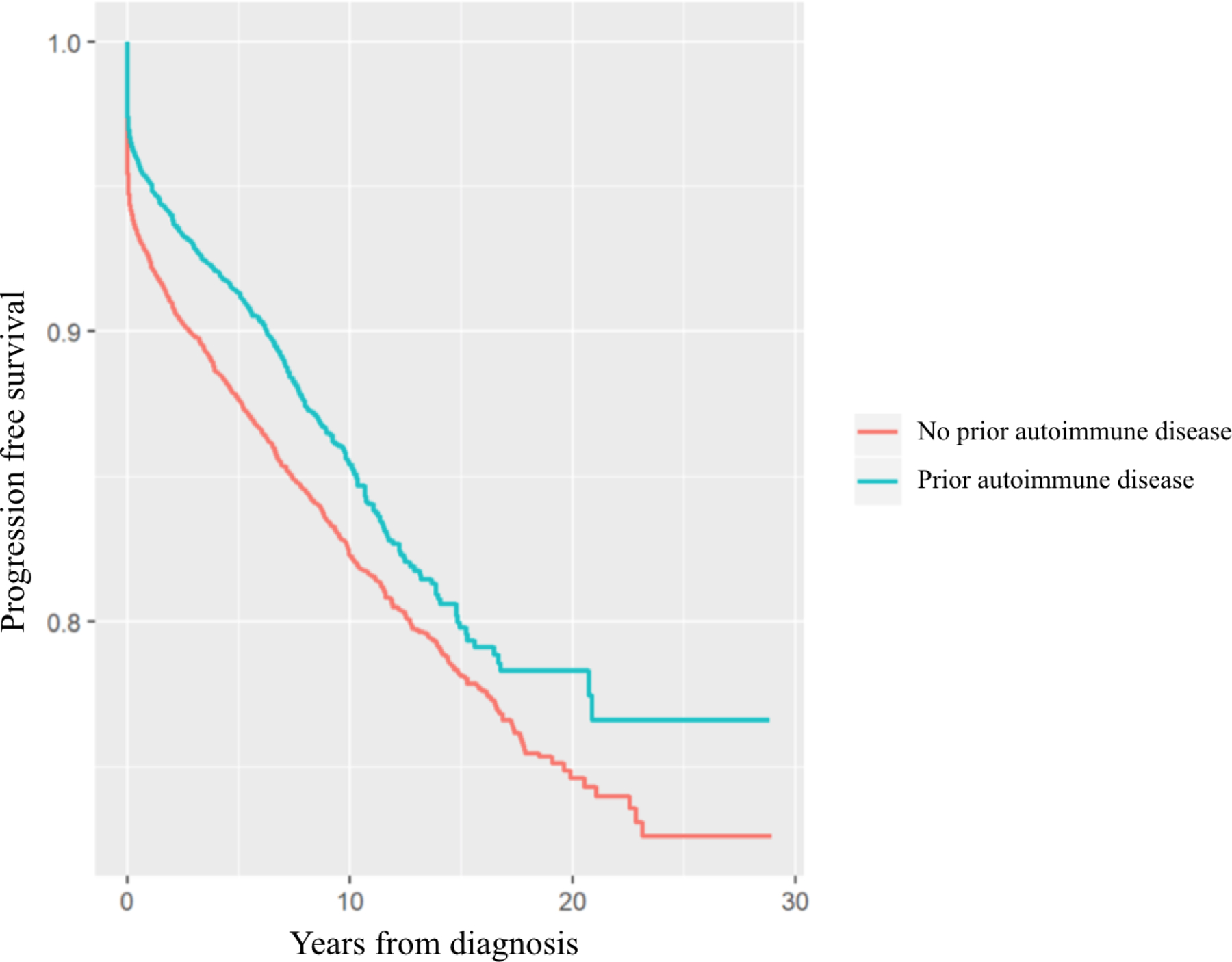

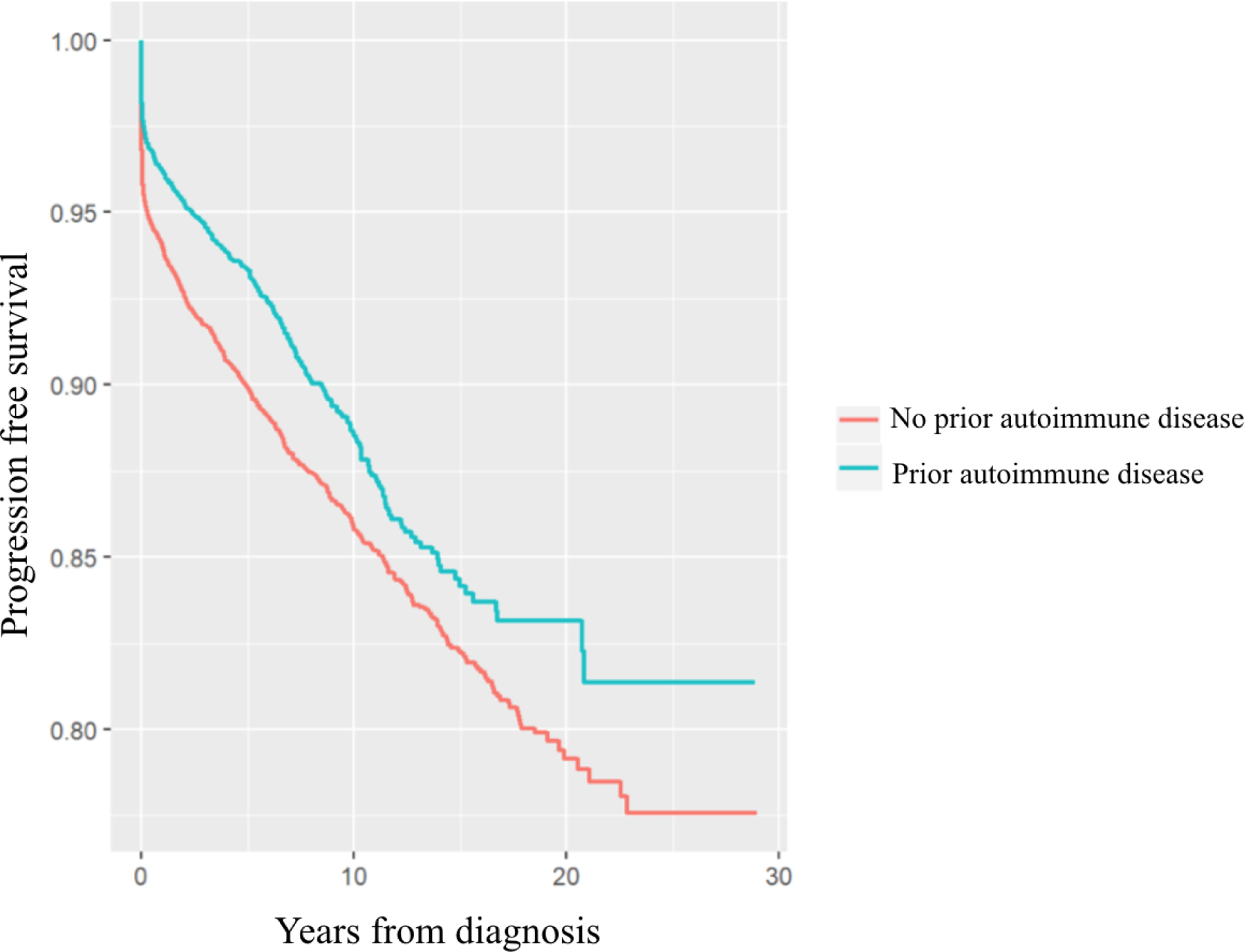

The progression of MGUS to LPs overall in those with prior autoimmune disease was significantly lower compared to those without (HR=0.84, 95% CI 0.75–0.94) (Figure 1 and Table 2). Similarly, progression to MM was significantly lower in those with any autoimmune disease (HR=0.83, 95% CI 0.73–0.94) (Figure 2 and Table 2). A significantly lower rate of progression to MM was found for those with a history of autoimmune diseases without detectable autoantibodies (HR=0.77, 95% CI 0.64–0.91) and for those with systemic involvement (HR= 0.79, 95% CI 0.62–0.996) but not for those with organ involvement (HR=0.87, 95% CI 0.73–1.03) (Table 2). Progression to LPs by subgroups was also significant for those with systemic involvement (HR=0.79, 95% CI 0.64–0.96) and those without detectable autoantibodies (HR=0.81, 95% CI 0.70–0.94) (Table 2) but not for those with organ involvement (HR=0.88, 95% CI 0.76–1.01). Specifically, a reduced risk of progression to LPs was found for MGUS patients with rheumatoid arthritis (HR=0.66, 95% CI 0.48–0.91). A significant difference in risk of progression to MM was not found for any of the other specific autoimmune diseases (Table 3).

Figure 1:

Survival free of progression to LPs

Table 2:

Progression of MGUS to MM and LP for those with autoimmune disease compared to those without by subgroups

| Hazard ratio✣ | 95% CI✣✣ | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progression to LP✣✣✣ | |||

| Overall | 0.84 | 0.75–0.94 | 0.0016 |

| Autoantibody not detected | 0.81 | 0.70–0.94 | 0.0043 |

| Organ involvement | 0.88 | 0.76–1.01 | 0.0742 |

| Systemic involvement | 0.79 | 0.64–0.96 | 0.0209 |

| Diagnosis made after 1993 | 0.87 | 0.77–0.98 | 0.0161 |

| Women | 0.90 | 0.78–1.05 | 0.1832 |

| Men | 0.78 | 0.66–0.91 | 0.0016 |

| Progression to MM✣✣✣✣ | |||

| Overall | 0.83 | 0.73–0.94 | 0.0036 |

| Autoantibody not detected | 0.77 | 0.64–0.91 | 0.0030 |

| Organ involvement | 0.87 | 0.74–1.03 | 0.1153 |

| Systemic involvement | 0.79 | 0.62–0.996 | 0.0463 |

| Diagnosis made after 1993 | 0.85 | 0.74–0.98 | 0.0234 |

| Women | 0.81 | 0.68–0.97 | 0.0197 |

| Men | 0.84 | 0.70–1.02 | 0.0746 |

Adjusted for age, gender and year of diagnosis

CI denotes confidence interval

Lymphoproliferative disease

Multiple myeloma

Figure 2:

Survival free of progression to MM

Table 3:

Personal history of autoimmune disease and risk of progression of MGUS to LP and MM

| LP✣ | MM✣✣ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=19,303) |

No progression (n= 16,952) |

Progression (n=2,351) |

HR✣✣✣ | 95% CI✣✣✣✣ | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Autoantibodies detectable | 3,731 | 3,355 | 376 | 0.73 | 0.61–0.86 | 0.0002 | 0.75 | 0.61–0.93 | 0.0079 |

| Systemic involvement | 1,271 | 1,152 | 119 | 0.67 | 0.51–0.88 | 0.0037 | 0.63 | 0.45–0.88 | 0.0077 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 979 | 886 | 93 | 0.66 | 0.48–0.91 | 0.0114 | 0.72 | 0.50–1.05 | 0.0870 |

| Sjögren syndrome | 225 | 198 | 27 | 1.20 | 0.74–1.94 | 0.4581 | 0.70 | 0.33–1.45 | 0.3297 |

| Organ involvement | 2,720 | 2,445 | 275 | 0.73 | 0.59–0.90 | 0.0034 | 0.80 | 0.62–1.03 | 0,0823 |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 125 | 106 | 19 | 1.04 | 0.43–2.51 | 0.9227 | 0.62 | 0.16–2.49 | 0,5005 |

| Chronic rheumatic heart disease | 169 | 153 | 16 | 0.49 | 0.20–1.17 | 0.1084 | 0.76 | 0.32–1.84 | 0.5478 |

| Diabetes type I | 1,621 | 1,461 | 160 | 0.85 | 0.62–1.17 | 0.3226 | 1.01 | 0.70–1.45 | 0.9607 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 70 | 61 | 9 | 0.82 | 0.45–1.48 | 0.4994 | 1.03 | 0.53–1.98 | 0.9307 |

| Pernicious anemia | 144 | 130 | 14 | 0.70 | 0.29–1.69 | 0.4298 | 1.09 | 0.45–2.64 | 0.8410 |

| Autoantibodies not detectable | 2,580 | 2,313 | 267 | 0.78 | 0.64–0.95 | 0.0116 | 0.69 | 0.54–0.89 | 0.0045 |

| Aplastic anemia | 188 | 153 | 35 | 1.21 | 0.50–2.92 | 0.6673 | 1.09 | 0.35–3.40 | 0.8772 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 118 | 105 | 13 | 0.41 | 0.15–1.10 | 0.0756 | 0.63 | 0.24–1.70 | 0.3626 |

| Crohn’s disease | 172 | 156 | 16 | 0.59 | 0.28–1.25 | 0.1693 | 0.64 | 0.27–1.54 | 0.3172 |

| Temporal arteritis | 354 | 310 | 44 | 1.05 | 0.67–1.63 | 0.8331 | 0.86 | 0.47–1.55 | 0.6111 |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 1,052 | 956 | 96 | 0.87 | 0.66–1.15 | 0.3378 | 0.78 | 0.54–1.12 | 0.1735 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 177 | 167 | 10 | 0.79 | 0.35–1.76 | 0.5589 | 0.57 | 0.18–1.78 | 0.3367 |

| Sarcoidosis | 144 | 134 | 10 | 0.52 | 0.25–1.08 | 0.0799 | 0.45 | 0.17–1.21 | 0.1133 |

| Ulcerative cholitis | 256 | 229 | 27 | 0.90 | 0.53–1.52 | 0.6918 | 0.97 | 0.52–1.80 | 0.9153 |

Lymphoproliferative disease

Multiple myeloma

Hazard ratio, adjusted for age, gender and year of diagnosis

CI denotes confidence interval

Yearly risk of progression to MM and other LPs was 0.88% per year for those with autoimmune diseases and 1.00% for those without autoimmune diseases.

Risk of progression by age, gender, and year of diagnosis

A significantly lower risk of progression to both MM (HR=0.85, 95% CI 0.74–0.98) and all LPs (HR= 0.87, 95% CI 0.77–0.98) was seen when only patients diagnosed after the year 1993 were included in the analysis (Table 2). Men (HR=0,78, 95% CI 0.66–0.91) with autoimmune diseases had a significantly reduced risk of progression to LPs compared to those without but women (HR=0.90, 95% CI 0.78–1.05) did not. Risk of progression to MM was lower in women with autoimmune diseases (HR=0.81, 95% CI 0.68–0.97), but the reduction in risk amongst men was not significant (HR=0.84, 95% CI 0.70–1.02) (Table 2). A significant reduction in risk of progression to LPs and MM was observed both in those aged 70 years and under and those aged 71 years and older at MGUS diagnosis, respectively (data not shown).

Risk of progression by M-protein isotype and concentration

Among individuals with IgA MGUS, those with autoimmune diseases were significantly less likely to progress to MM (HR=0.39, 95% CI 0.17–0.88) but no significant difference was found for progression to all LPs (HR=0.51, 95% CI 0.26–1.00). In IgG MGUS, those with autoimmune diseases were significantly less likely to progress to MM (HR=0.60, 95% CI 0.39–0.92) but no significant difference was found for progression to all LPs (HR=0.75, 95% CI 0.52–1.08). Among those with M-protein levels below 1.5 g/dL, a significant reduction in risk of progression to MM was found among those with an autoimmune disease (HR=0.44, 95% CI 0.22–0.86), but no difference was found in risk of progression to all LPs in the same group (HR=0.94, 95% CI 0.65–1.37). For those with M-protein levels higher than or equal to 1.5 g/dL no significant difference was observed (Table 4).

Table 4:

Progression for those with autoimmune disease compared to those without by age, M-protein concentration and immunoglobulin type

| Hazard ratio✣ | 95% CI✣✣ | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progression to LP✣✣✣ | |||

| M-protein ≥1,5 g/dL | 0.66 | 0.38–1.13 | 0.1282 |

| M-protein <1,5 g/dL | 0.94 | 0.65–1.37 | 0.7491 |

| IgG M-protein | 0.75 | 0.52–1.08 | 0.1238 |

| IgA M-protein | 0.51 | 0.26–1.00 | 0.0506 |

| IgM M-protein | 0.91 | 0.44–1.88 | 0.7918 |

| Biclonal M-protein | 1.09 | 0.43–2.74 | 0.8579 |

| Progression to MM✣✣✣✣ | |||

| M-protein ≥1,5 g/dL | 0.80 | 0.45–1.44 | 0.4629 |

| M-protein <1,5 g/dL | 0.44 | 0.22–0.86 | 0.0160 |

| IgG M-protein | 0.60 | 0.39–0.92 | 0.0204 |

| IgA M-protein | 0.39 | 0.17–0.88 | 0.0229 |

| IgM M-protein | 7.11 | 0.57–88.10 | 0.1268 |

| Biclonal M-protein | 1.15×10−8 | 0−∞ | 9.98×10−1 |

Adjusted for age, gender and year of diagnosis

CI denotes confidence interval

Lymphoproliferative disease

Multiple myeloma

In analysis adjusted for age, gender, year of diagnosis, M-protein isotype and concentration, the risk of progression was still significantly lower for MM (HR=0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.90) but not for all LPs (HR=0.81, 95% CI 0.59–1.11).

Discussion

In our large, population-based, cohort study, including over 19,000 MGUS patients, whereof 5,612 had prior autoimmune diseases, we are the first to demonstrate that people with MGUS and prior autoimmune disease have a significantly 17% lower risk of progression to MM. This was also true when analyses were adjusted for other known risk factors for progression. When looking at specific autoimmune diseases, rheumatoid arthritis was associated with a significantly lower risk of progression to all LPs. This is an important finding and shows that even though MGUS is more common in individuals with autoimmune diseases, it has a more benign course. Interestingly, we have previously found mortality in MGUS and MM to be increased in those with autoimmune diseases, where those with MGUS and prior autoimmune disease had a significant 1.4-fold increased risk of death.28 However, that study did not specify the cause of death in these individuals. The reasons for this increase in mortality were speculated to be due to common underlying genetic factors, cumulative comorbidity or because individuals with autoimmune diseases developed more severe types of MGUS. Our current results do not support this last hypothesis.

We found that a personal history of any autoimmune disease lowers the risk of progression of MGUS to both MM and all LPs. Additionally, the risk of progression to all LPs was significantly reduced for those with autoimmune diseases without detectable antibodies and for those with systemic involvement. The risk of progression to MM was also significantly lower for those without detectable antibodies and for those with systemic involvement. As it is well established that patients with an autoimmune disease have an increased risk of MGUS it is important to evaluate the natural course of MGUS in these individuals. A retrospective study of US veterans found an elevated risk of both MGUS and MM in those with a prior history of any autoimmune disease17 and a meta-analysis of 32 studies, published in 2014, supported an association between MM and MGUS with “any autoimmune disease”, with that relationship being stronger for MGUS.18 In our previous study, based on 5,403 MGUS patients, 19,112 MM patients and 96,617 matched controls, we also found the association of MGUS and autoimmune diseases to be stronger than that for MM and autoimmune diseases.19 LPs have also been shown to be more prevalent in those with prior autoimmune disease.21,22,29 The reasons for this increased incidence in MGUS, and in some cases MM, have been theorized to stem from chronic antigen stimulation triggering the development of a plasma cell disorder or from a common genetic or environmental susceptibility.19 This indicates that MGUS associated with autoimmune disease is biologically distinct from MGUS in those without autoimmune disease. Our present findings lend further support to that notion. There is some evidence to support this theory, among them a small study from 2012 showing that patients with smoldering MM (SMM) and autoimmune disease to have significantly lower expression of adverse plasma cell markers compared to those with SMM and without autoimmune disease. However, the expression was similar in those with MGUS.30 Notwithstanding that, the increased incidence of MGUS among those with autoimmune disease is still associated with an increased risk of developing MM or other LPs compared to the general population, even though they progress more slowly than those with MGUS without a prior history of autoimmune disease.

We found a history of rheumatoid arthritis to be associated with a statistically significant 34% lower risk of progression to all LPs. In our previous study, rheumatoid arthritis was linked to an increased risk in MGUS but a decreased risk of MM.19 No autoimmune diseases were found to increase the risk of progression compared to those without autoimmune diseases. In our previous study we found that autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), polymyalgia rheumatica, and giant cell arteritis increased the risk of MM.19 In the previously mentioned meta-analysis, risk of both MGUS and MM was elevated only for AIHA and pernicious anemia.18 In the current study, we did not find any significant change in progression to malignancy with any of these conditions. This supports our interpretation that although rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune disease are associated with an increased risk of MGUS, the progression risk seems to be lower.

Importantly, when results were adjusted for concentration and type of M-protein, two of the known risk factors for progression, there was still significant reduction in the risk of progression of MGUS to MM and a non-significant reduction in risk of progression to all LPs. This indicates that there is a true reduction in the rate of progression and that earlier diagnosis due to surveillance and a lower concentration of M-protein do not fully explain the lower rate of progression among those with autoimmune disease.

Our study has several strengths. The most important one is the large number of cases included, based on very reliable sources of data. Our data cover a long study period and are derived from a population that is stable and had access to consistent medical care throughout that period. With our population- and register-based design we were able to rule out any potential recall bias.

Our study has some limitations. The register used to identify diagnoses of autoimmune diseases included outpatients only after the year 2000. Therefore, we are likely to have missed some of the less severe autoimmune conditions and our results thus may mainly apply to the more serious ones. However, we did not require the diagnosis of autoimmune disease to be a primary diagnosis. For many of the autoimmune diseases analyzed, there were few cases in each category resulting in low power. Information on the type, concentration of M-protein and FLC were often not available and therefore our calculations of risk of progression corrected for type and concentration of M-protein had reduced power. The fact that patients with autoimmune disease had a significantly lower level of M-protein at diagnosis indicates that a part of the reason for a higher prevalence in that population might be due to a detection bias. These patients are usually under regular surveillance of a specialist and are more likely to have blood tests done routinely, and therefore be diagnosed earlier, while some might even never have been diagnosed with MGUS at all if they had not been regularly monitored for their autoimmune disease. However, when we adjusted for M-protein concentration and type our overall findings were still significant. Unfortunately, we did not have information on FLC ratio and thus were unable to correct for that.

In conclusion, our results show that progression of MGUS to MM and LPs is significantly lower for those with prior autoimmune disease. Potential underlying causes of the lower risk of progression in this population may be that MGUS in the setting by chronic low-level antigen stimulation is biologically less likely to undergo the genetic events that trigger progression, or it may be reflective of immunosuppressing therapies (e.g., steroid and TNF inhibitors) used to treat autoimmune conditions delay or prevent progression, or a combination. Independent of underlying mechanisms, our results might affect clinical counselling in patients with autoimmune diseases as these patients have a lower than average risk of progression to MM and other LPs. Further prospective screening studies are needed, both to cast light on the underlying process and identify other factors (such as the effect of any ongoing immune-modulating treatment or the effect of diagnostic bias) among those with autoimmune diseases.

Supplementary Material

Novelty statement.

In this large population-based study of MGUS cases, having a history of autoimmune disease was protective against progression from MGUS to multiple myeloma or related lymphoproliferative disorders.

Potential underlying causes of the lower risk of progression in this population may be that MGUS in the setting by chronic low-level antigen stimulation is biologically less likely to undergo the genetic events that trigger progression, or it may be reflective of immunosuppressing therapies used to treat autoimmune conditions, or a combination.

Our results may have implications in clinical counselling for patients with MGUS and underlying autoimmune disorders.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by grants from the University of Iceland Research Fund, Icelandic Centre for Research (RANNIS), Landspitali University Hospital Research Fund, Karolinska Institutet Foundations, Marie Curie CIG, and the Swedish Cancer Society in Stockholm. Dr. Landgren would like to thank funding support by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Core Grant (P30 CA008748).

Disclosures for Dr. Landgren:

•Grant support: NIH, FDA, MMRF, IMF, LLS, Perelman Family Foundation, Rising Tides Foundation, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Takeda, Glenmark, Seattle Genetics, Karyopharm

•Honoraria/ad boards: Adaptive, Amgen, Binding Site, BMS, Celgene, Cellectis, Glenmark, Janssen, Juno, Pfizer

•Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC): Takeda, Merck, Janssen

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data Availability Statement

Due to ethical constraint individual data can not be made publicly available.

Bibliography

- 1.Kyle RA, Durie BG, Rajkumar SV, Landgren O, Blade J, Merlini G, et al. , Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma: IMWG consensus perspectives risk factors for progression and guidelines for monitoring and management. Leukemia 2010; 24(6): 1121–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, Merlini G, Mateos MV, et al. , International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15(12): e538–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Larson DR, Plevak MF, Offord JR, et al. , Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(13): 1362–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwanaga M, Tagawa M, Tsukasaki K, Kamihira S,Tomonaga M, Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: study of 52,802 persons in Nagasaki City, Japan. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82(12): 1474–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landgren O, Katzmann JA, Hsing AW, Pfeiffer RM, Kyle RA, Yeboah ED, et al. , Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among men in Ghana. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82(12): 1468–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, Larson DR, Melton LJ 3rd, Colby CL, et al. , Prevalence and risk of progression of light-chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet 2010; 375(9727): 1721–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.La Raja M, Barcobello M, Bet N, Dolfini P, Florean M, Tomasella F, et al. , Incidental finding of monoclonal gammopathy in blood donors: a follow-up study. Blood Transfus 2012; 10(3): 338–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanaboonyongcharoen P, Nakorn TN, Rojnuckarin P, Lawasut P,Intragumtornchai T, Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance in Thailand. Int J Hematol 2012; 95(2): 176–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landgren O, Kyle RA, Pfeiffer RM, Katzmann JA, Caporaso NE, Hayes RB, et al. , Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Blood 2009; 113(22): 5412–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss BM, Abadie J, Verma P, Howard RS,Kuehl WM, A monoclonal gammopathy precedes multiple myeloma in most patients. Blood 2009; 113(22): 5418–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Offord JR, Larson DR, Plevak MF, et al. , A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med 2002; 346(8): 564–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Melton LJ 3rd, Bradwell AR, Clark RJ, et al. , Serum free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood 2005; 106(3): 812–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turesson I, Kovalchik SA, Pfeiffer RM, Kristinsson SY, Goldin LR, Drayson MT, et al. , Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and risk of lymphoid and myeloid malignancies: 728 cases followed up to 30 years in Sweden. Blood 2014; 123(3): 338–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyle RA, Larson DR, Therneau TM, Dispenzieri A, Kumar S, Cerhan JR, et al. , Long-Term Follow-up of Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(3): 241–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cesana C, Klersy C, Barbarano L, Nosari AM, Crugnola M, Pungolino E, et al. , Prognostic factors for malignant transformation in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20(6): 1625–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez-Persona E, Mateo G, Garcia-Sanz R, Mateos MV, de Las Heras N, de Coca AG, et al. , Risk of progression in smouldering myeloma and monoclonal gammopathies of unknown significance: comparative analysis of the evolution of monoclonal component and multiparameter flow cytometry of bone marrow plasma cells. Br J Haematol 2010; 148(1): 110–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown LM, Gridley G, Check D,Landgren O, Risk of multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among white and black male United States veterans with prior autoimmune, infectious, inflammatory, and allergic disorders. Blood 2008; 111(7): 3388–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McShane CM, Murray LJ, Landgren O, O’Rorke MA, Korde N, Kunzmann AT, et al. , Prior autoimmune disease and risk of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and multiple myeloma: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014; 23(2): 332–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindqvist EK, Goldin LR, Landgren O, Blimark C, Mellqvist UH, Turesson I, et al. , Personal and family history of immune-related conditions increase the risk of plasma cell disorders: a population-based study. Blood 2011; 118(24): 6284–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristinsson SY, Goldin LR, Bjorkholm M, Koshiol J, Turesson I,Landgren O, Genetic and immune-related factors in the pathogenesis of lymphoproliferative and plasma cell malignancies. Haematologica 2009; 94(11): 1581–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kristinsson SY, Landgren O, Sjoberg J, Turesson I, Bjorkholm M,Goldin LR, Autoimmunity and risk for Hodgkin’s lymphoma by subtype. Haematologica 2009; 94(10): 1468–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kristinsson SY, Koshiol J, Bjorkholm M, Goldin LR, McMaster ML, Turesson I, et al. , Immune-related and inflammatory conditions and risk of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma or Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010; 102(8): 557–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nilsson AC, Spetz CL, Carsjo K, Nightingale R,Smedby B, [Reliability of the hospital registry. The diagnostic data are better than their reputation]. Lakartidningen 1994; 91(7): 598, 603–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swedish national board of health. Patientregistret Stockholm, Sweden. Socialstyrelsen; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turesson I, Linet MS, Bjorkholm M, Kristinsson SY, Goldin LR, Caporaso NE, et al. , Ascertainment and diagnostic accuracy for hematopoietic lymphoproliferative malignancies in Sweden 1964–2003. Int J Cancer 2007; 121(10): 2260–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landgren O, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Gridley G, Mellemkjaer L, Olsen JH, et al. , Autoimmunity and susceptibility to Hodgkin lymphoma: a population-based case-control study in Scandinavia. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98(18): 1321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landgren O, Linet MS, McMaster ML, Gridley G, Hemminki K,Goldin LR, Familial characteristics of autoimmune and hematologic disorders in 8,406 multiple myeloma patients: a population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer 2006; 118(12): 3095–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindqvist EK, Landgren O, Lund SH, Turesson I, Hultcrantz M, Goldin L, et al. , History of autoimmune disease is associated with impaired survival in multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a population-based study. Ann Hematol 2017; 96(2): 261–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smedby KE, Hjalgrim H, Askling J, Chang ET, Gregersen H, Porwit-MacDonald A, et al. , Autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma by subtype. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98(1): 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwok M, Korde N, Manasanch EE, Bhutani M, Maric I, Calvo KR, et al. , Role of immune-related conditions in smoldering myeloma and MGUS. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2012; 30(15_suppl): 8104–8104. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Due to ethical constraint individual data can not be made publicly available.