Abstract

The timing of the preovulatory surge of luteinizing hormone (LH), which occurs on the evening of proestrus in female mice, is determined by the circadian system. The identity of cells that control the phase of the LH surge is unclear: evidence supports a role of arginine vasopressin (AVP) cells of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), but it is not known whether vasopressinergic neurons are necessary or sufficient to account for circadian control of ovulation. Among other cell types, evidence also suggests important roles of circadian function of kisspeptin cells of the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AvPV) and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons of the preoptic area (POA), whose discharge is immediately responsible for the discharge of LH from the anterior pituitary. The present studies used an ovariectomized, estradiol-treated preparation to determine critical cell types whose clock function is critical to the timing of LH secretion. As expected, the LH surge occurred at or shortly after ZT12 in control mice. In further confirmation of circadian control, the surge was advanced by 2 h in tau mutant animals. The timing of the surge was altered to varying degrees by conditional deletion of Bmal1 in AVPCre, KissCreBAC, and GnRHCreBAC mice. Excision of the mutant Cnsk1e (tau) allele in AVP neurons resulted in a reversion of the surge to the ZT12. Conditional deletion of Bmal1 in Kiss1 or GnRH neurons had no noticeable effect on locomotor rhythms, but targeting of AVP neurons produced variable effects on circadian period that did not always correspond to changes in the phase of LH secretion. The results indicate that circadian function in multiple cell types is necessary for proper timing of the LH surge.

Keywords: circadian, luteinizing hormone, Bmal1, vasopressin, kisspeptin, GnRH

The timing of the transition of the effects of estradiol (E2) from negative to positive feedback on the afternoon of proestrus critically determines the initiation of ovulation. Perhaps no finding was more important in founding the field of neuroendocrinology than the discovery by Everett and Sawyer (1950) that barbiturates, if administered to rats during a critical period on the day of proestrus, delay ovulation by 24 h. Not only did this implicate neural (specifically GABAergic) control, but it also implied an essential role of a light-regulated clock. Over the intervening decades, the circadian basis of the preovulatory luteinizing hormone (LH) surge has been amply demonstrated. Ovariectomized, estrogen-implanted (OVX+E) rats generate repeated daily LH surges (Legan and Karsch, 1975). Barbiturates delay LH surges by 24 h in this preparation (again, only if administered during a critical period in the early afternoon). Electrolytic lesions of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus (the site of a master circadian pacemaker) arrest the estrous cycle and LH surges (Wiegand and Terasawa, 1982), as do genetic manipulations that compromise the circadian clock (Miller et al., 2004; Chu et al., 2013). Splitting of circadian rhythms, induced by exposure to constant light, causes OVX+E hamsters to generate 2 surges per day (Swann and Turek, 1985), each of which is phase locked to activation of the ipsilateral SCN (de la Iglesia et al., 2003), and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) cells receive appositions from SCN neurons in this species (de la Iglesia et al., 1995). The loci of circadian control remain uncertain, however, with evidence to support critical roles of clocks in several cell types (reviewed by Christian and Moenter, 2010; de la Iglesia and Schwartz 2006; Williams and Kriegsfeld, 2012; Tonsfeldt and Chappel, 2012; Simmoneaux and Bahougne, 2015). Within the SCN, vasopressinergic neurons may play a critical role in determining the timing of the LH surge (Palm et al., 1999, 2001; Kalamatianos et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2006; Smarr et al., 2012). These cells project to a kisspeptinergic population in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AvPV) that plays a critical role in estradiol positive feedback (Smith et al., 2006; Clarkson et al., 2008; Vida et al., 2010; Ronnekleiv et al., 2014; Yip et al. 2015). Nevertheless, it is not clear that vasopressin neurons are necessary or sufficient to ensure circadian control of the LH surge, and other SCN cell types may also make critical contributions. In particular, VIP neurons regulate LH secretion, project directly to GnRH cells, and make preferential synaptic connections with those that are activated at the time of the surge (Vijayan et al., 1979; Samson et al., 1981; Alexander et al., 1985; Kimura et al., 1987; Van der Beek et al., 1994, 1997, 1999; Horvath et al., 1998; Smith et al., 2000; Kriegsfeld et al., 2002; Christian and Moenter, 2008; Piet et al., 2016). Efferent projections of prokineticin 2 neurons may also play an important role (Xiao et al., 2014).

Clock function in cells outside the SCN may also be necessary to ensure proper timing of the LH surge. The interlocked transcriptional-translational feedback loops (TTFLs) that comprise principal components of cell-autonomous circadian clocks are expressed widely in the brain and periphery. This raises the possibility that circadian function not only of cells of the SCN but also of neurons elsewhere in the ovulatory circuit may have an important role in the generation of the LH surge. Evidence has been gathered for control of the timing of ovulation by circadian rhythms in kisspeptin cells of the AvPV (Xu et al., 2011; Smarr et al., 2013; Chassard et al., 2015) and in the GnRH cells themselves (Gillespie et al., 2003; Chao and Kriegsfeld, 2009; Hickok and Tishkau, 2010; Tonsfeldt et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2011).

Conditional knockout of clock genes in specific neuronal types has proven to be a powerful tool in the examination of circadian function (Storch et al., 2007; Husse et al., 2011; Smyllie et al., 2016; Van der Vinne et al., 2018; Weaver et al., 2018). The present experiments targeted Bmal1, a critical constituent of the TTFL, to test the importance for estrogen-induced LH surges of circadian function in arginine vasopressin (AVP), kisspeptin, or GnRH cells. In addition, the effects of altering circadian period (τ) selectively within AVP neurons were examined. The results indicate that circadian rhythmicity of AVP neurons is of particular, but not exclusive, importance in determining the timing of the LH surge. The operation of circadian clocks in kisspeptin and GnRH neurons is also critical. The findings suggest the importance of circadian resonance: the periods of clocks in these cell types must correspond for a normal LH surge to be generated.

METHODS

Mice were maintained in 12L:12D unless noted otherwise and had ad libitum access to Purina chow (#5058) and water throughout these experiments. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Mouse Lines

Several Cre lines were used in these studies. AVP-IRES-Cre mice were obtained from Dr. Brad Lowell (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA; Krashes et al., 2014). Kiss1CreBac mice were kindly provided by Drs. Anne Langjuin and Catherine Dulac (Harvard University, Boston, MA). The Cre cDNA sequences including a bGH polyA tail were recombined after the Kiss1 translational start ATG on BAC RP23-240P23 (Wang, 2012). GnRHCreBac mice, also known as Lhrh strain, were also provided by Dr. Dulac. These mice are available as Tg(Gnrh1-cre)1Dlc/J (Jackson lab stock No. 021207), and bear 1.8 kb of genomic DNA centered arormd the start codon of GnRH, introduced by homologous recombination into BAC RP23-22J8 (Yoon et al., 2005; Hoffmann et al., 2019). Both Kiss1CreBAC and GnRHCreBAC mice were on a C57BL/CBA mixed background.

Founder Bmal1fl/fl mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (stock No. 007668, B6.129S4[Cg]-Arntltm1Weit/J). Circadian rhythms are eliminated when this conditional allele is excised through the action of Cre recombinase (Storch et al., 2007). CnSK1etau mice, in which loxP sites flank mutant exon 4, were kindly provided by Dr. Andrew Loudon (University of Manchester, Manchester, UK). These mice are available from Jackson laboratories as B6.129-Csnk1etm1Asil/J. They carry a mutation of Csnk1e, which codes for a gain-of-function isoform of casein kinase. This allele becomes nonfunctional upon action of Cre recombinase (Loudon et al., 2007; Meng et al., 2008), causing reversion of the circadian period from approximately 20 h or 22 h (in homozygotes or heterozygotes carrying the floxed allele, respectively) to about 24 h. Combinations of mutant alleles were achieved by crossing mice of appropriate genotypes and verified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Primers for each transgene and cycle parameters are described in the supplementary methods.

Assessment of Locomotor Activity Rhythms

Mice were placed in individual cages in a light-tight cabinet. Each cage contained a running wheel (12-cm diameter) that tripped a magnetic read switch on each revolution. Activity was recorded and analyzed using a Clocklab Actimetrics package. Mice were maintained in 12L:12D for at least 7 days to assess the entrained phase angle and in DD for 10 days to assess the circadian period by fitting a linear regression line to activity onsets.

Assessment of Reproductive Function

Estrous cycles were assessed by vaginal smears taken during the light phase. After at least 12 days, animals were ovariectomized under isoflurane anesthesia. Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) was administered at the time of surgery and used for up to 48 h thereafter as postoperative analgesia. To determine the capacity of each mouse to generate an LH surge, we adopted the 2-step injection procedure described by Ronnekleiv and colleagues (Ronnekleiv et al., 2014; Qiu et al., 2016). At about ZT4 on the fifth day following ovariectomy, females received a priming dose of estradiol benzoate (EB; 0.25 μg in 50 μL sesame oil, subcutaneously). The next day, a surge-inducing dose of EB (1.0 μg/50 μL sesame oil) was given at ZT4. On the following day, mice were restrained at 90-min intervals, and blood samples (1-2 μL) were taken from the tail vein using a GentleSharp probe (Actuated Medical, Bellefonte, PA) beginning at ZT9 and continuing until ZT15.

LH concentrations were determined using the method of Steyn et al. (2013). Whole blood was diluted (1 μL/50 μL assay buffer). The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay used a primary monoclonal anti-LHβ (518B7, 1:1000, Janet Rosner, University of California, Davis), a polyclonal rabbit anti-LH (AFP240580, from the National Hormone and Pituitary Program), and a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Agilent P044801-2). Mouse LH (AFP-5306A, NIDDK-NHPP) was used as standard. Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 9.6% and 5.8%, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

The period and phase of locomotor rhythms were determined by linear regression of activity onsets as previously described (Bittman, 2012). To assess the incidence of LH surges, Chi-squared tests were performed to determine the proportion of wild-type and of each conditional knockout strain showing elevated LH (>5 ng/mL) at each of the 6 sampling times. In addition, LH values of wild-type and Bmal1fl/fl mice carrying AVPCre, KissCreBAC, or GnRHCreBAC were used to assess genotype effects by 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with repeated measures on the ZT factor. Time and strain were main effects. Effects of the tau mutation and its reversal in AVP cells were examined in a separate repeated-measures 2-way ANOVA. The Mann-Whitney test was used to assess differences between LH concentrations of groups of mice at ZT12.

RESULTS

Behavioral Rhythms

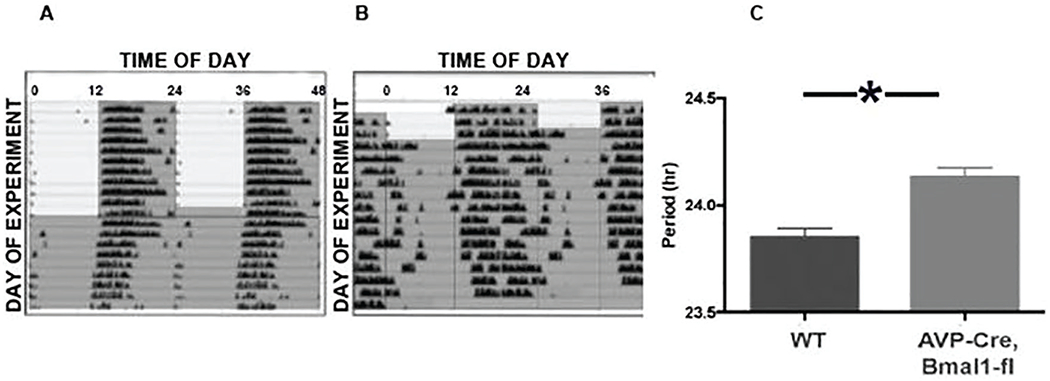

Wild-type mice entrained to 12L:12D with activity onset at approximately the time of lights-off. When released into DD, these animals free ran with the expected period (τDD = 23.77 ± 0.10 h; Fig. 1). In contrast, conditional knockout of Bmal1 in AVP cells lengthened the free-running period, as previously reported by Mieda et al. (2015, 2016). Neither entrainment nor τDD was markedly affected by conditional knockout of Bmal1 in GnRH or Kiss cells (Suppl. Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

A, representative double plotted actogram of a wild type mouse that was initially maintained in 12L:12D (gray shading indicates lights off) before release into constant darkness (DD). B., Actogram of a representative AVPCre,Bmal1fl/fl mouse under the same conditions. C, mean (+SEM) free running period (τDD) of 14 mice studied in this experiment (* indicates p < 0.05).

Additional experiments used tau mutant mice. As previously reported (Meng et al., 2008), mice homozygous for the floxed Cnske1 (tau) allele in the absence of Cre showed a τDD of approximately 20 h. These mice were crossed with Cre animals to induce selective reversion to a wild-type circadian period in particular cell types. Most AVPCre, Cnsk1etau mice became active at about the time of lights-off, although the phase of locomotor onset upon release in DD indicated negative masking (Fig. 2). After transfer to DD, free-running patterns of activity varied: some showed no evidence of a change in τDD, while others experienced a partial lengthening of the free-running period, although none achieved the period of the wild-type. Still other AVPCre, Cnsk1etau mice showed unstable or disrupted locomotor activity (Fig. 2F,G). There was no apparent correlation between the locomotor pattern and homozygosity of the Cre allele.

Figure 2.

Actograms of AVPCre/+, Cnsk1etau/tau mice that were maintained in 12L:12D (gray shading indicates dark phase) and then released into DD. In some cases (A-C), free running rhythms were similar to mice not bearing a Cre allele (τDD approximately 20h). (D, E), Other AVPCre mice showed a partial reversion to a longer period, although none of these mice free ran with as long a period as WT mice. Several mice (F, G) showed nocturnal activity in 12L:12D but unstable patterns of running wheel activity in DD.

Estrous Cycles and the LH Surge

Before ovariectomy, control mice showed regular 4-day estrous cycles. Estrous cycles were irregular in AVPCre, Bmal1fl/fl and GnRHCreBAC, Bmalfl/fl animals as the time spent in estrus was extended (Suppl. Fig. S2). KissCreBac, Bmal1fl/fl mice showed regular estrous cycles (Suppl. Fig. S3).

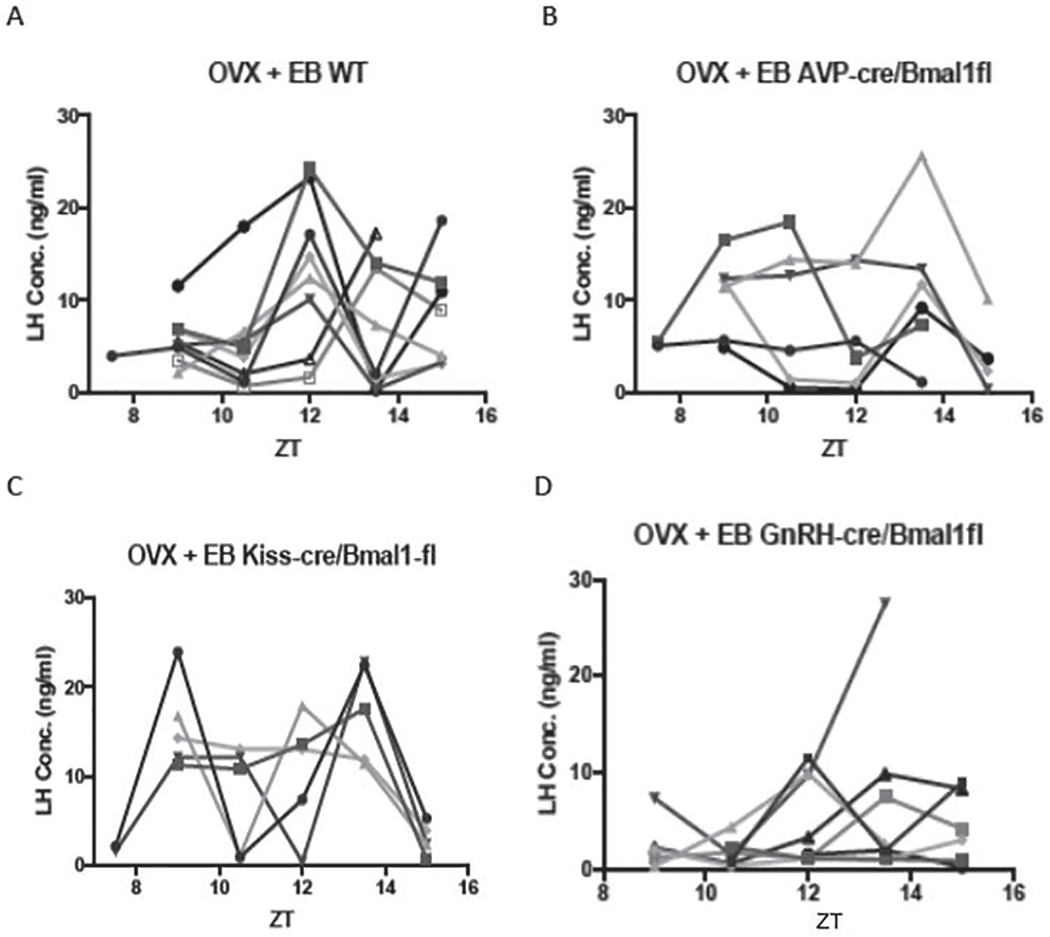

After ovariectomy, control mice showed a clear surge of LH either at dusk (ZT12, n = 6) or shortly thereafter (ZT13.5, n = 2) at the end of the light phase (Fig. 3A). In all but 1 of these mice, basal LH levels observed at ZT10 were at or below 5 ng/mL, indicating that the estrogen injection regimen effectively activated the negative feedback response in ovariectomized animals. There were no consistent differences between the LH patterns of wild-type females, Bmal1fl/fl and Bmalfl/+ animals lacking Cre, or Cre animals lacking a floxed allele.

Figure 3.

A, LH concentrations (ng/ml) in individual ovariectomized control mice given priming followed by surge-inducing doses of estradiol benzoate. B, C, D., LH values in similarly treated AVPCre/+,Bmal1fl/fl, KissCreBAC,Bmalfl/fl, and GnRHCreBAC,Bmalfl/fl mice, respectively.

Both genetic construct and ZT had significant effects on LH concentration (F = 4.07, p = 0.02 and F = 3.0, p = 0.03, respectively; Suppl. Fig. S4). The interaction between group and ZT did not reach significance (F = 1.99, p = 0.056), but LH concentration and the incidence of LH surges at ZT12 in each of the Cre groups was significantly altered from the wild-type controls (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test, and p < 0.001, χ2 test, respectively). None of the 6 AVPCre/+, Bmal1fl/fl mice showed an LH surge at ZT12 (Fig. 3B). Two mice in this group showed a low-amplitude rise at ZT13.5, and LH peaked at this point in 1 animal but from a high baseline. This was 1 of 3 cases in which basal LH was elevated at ZT9, indicating a defect in negative feedback.

Conditional deletion of Bmal1 in Kiss cells also altered the pattern of LH secretion (Fig. 3C). Several of these mice showed a bimodal pattern of LH concentrations, and only 1 showed a surge at ZT12. This animal, and 2 others that experienced a peak at ZT13.5, had high LH levels at ZT9 as well, suggesting an abnormality in negative feedback that affected baseline concentrations.

GnRHCreBAC, Bmal1fl/fl mice showed the most consistent disruption of the LH surge of all experimental groups (Fig. 3D). LH surges failed to occur at ZT12 in most cases, and elevations of LH observed at lights-off or at ZT13.5 were of lower amplitude than in controls.

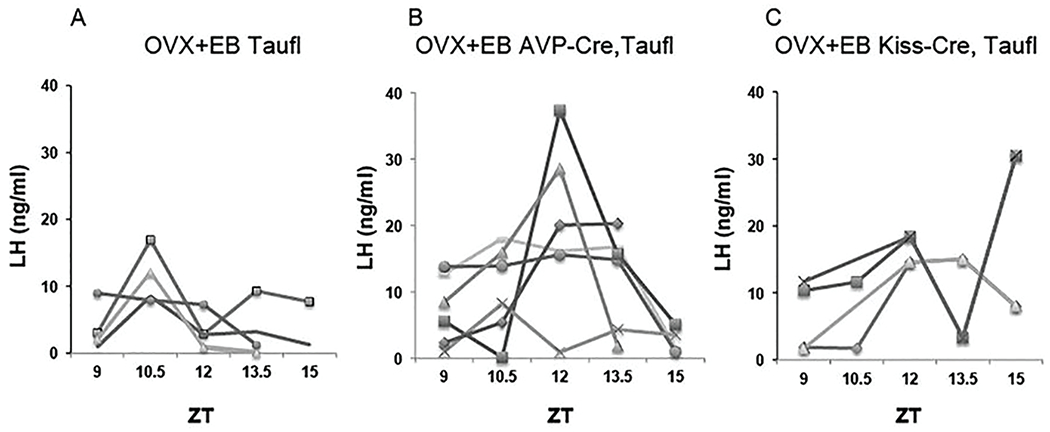

To assess further the role of circadian function of AVP cells in determining the phase of the LH surge, Cnsk1etau females were compared with controls that lacked the Cnsk1etau allele and with AVPCre, Cnsk1etau animals (Fig. 4). Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures showed significant effects of genotype (F = 4.48, p = 0.03) and ZT (p = 0.001) and an interaction between these main factors (F = 26, p = 0.03; Suppl. Fig. S5). LH surges in Cnsk1etau mice tended to be advanced relative to lights-off, with 3 animals showing a clear surge at ZT10.5. This pattern was altered in Cnsk1etau mice bearing the AVPCre/+ allele. Three such animals experienced a reversion of the timing of the surge to the wild-type phase, with a peak at ZT12. Three others showed no discrete surge; 2 of these animals had continuously elevated LH concentrations between ZT9 and 13.5, suggestive of a disruption of negative feedback. Overall, LH concentrations at ZT12 did not differ between AVPCre, Cnsk1etau mice and controls that lacked the tau allele (Mann-Whitney test, UA = 27, p > 0.05). We did not observe any consistent correlation between the reversion of locomotor rhythms (Fig. 2) and the pattern of LH secretion (Suppl. Fig. S6). A small experiment involving 4 KissCreBac, Cnsk1etau mice indicated an effect of deleting the tau allele in kisspeptin cells as well, but this manipulation produced high baseline LH levels that complicated the assessment of the timing of the LH surge (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

A, Circulating LH (ng/ml) in individual CnSK1etau ovariectomized control mice given priming followed by surge-inducing doses of estradiol benzoate. B, LH concentrations in identically treated AVPCre/+,Cnsk1etau/tau mice. C. LH concentrations in identically treated KissCreBAC,CnSK1etau/tau mice.

DISCUSSION

The LH surge is disrupted by conditional knockout of Bmal1 not only in vasopressin cells, which may provide a critical output of the pacemaker, but also in Kiss or GnRH cells. Thus, proper timing of the LH surge requires operation of circadian clocks at 3 or more points in the circuit, including cells that are direct or indirect targets of SCN efferents. The importance of circadian function in Kiss and GnRH cells may be explained by their function as subordinate oscillators, which need SCN input to maintain phase coherence (Xu et al., 2011; Smarr et al., 2013; Chassard et al., 2015; Hickok and Tishkau, 2010; Williams et al., 2011). The traditional view is that SCN signals are critical to the generation of the LH surge because they acutely activate such targets. The present results support the alternative interpretation that the LH surge depends on the function of the circadian pacemaker to entrain them. Significantly, the effect of the conditional deletion of Bmal1 in any one of these cell types was not to eliminate the surge but to alter its timing. This may reflect loss of phase coherence within Kiss and/or GnRH cell populations. Such desynchronization may progress gradually in uncoupled neuronal populations, as cell-autonomous oscillations may differ only slightly in period so that they drift out of phase only after several cycles when deprived of critical input from vasopressinergic (and perhaps other) cells of the SCN. It is possible that disruption of circadian function in AVP, Kisspeptin, and/or GnRH cells would compromise the LH surge more severely in mice kept in constant conditions; the light:dark cycle to which mice were exposed in the present experiments may have provided a masking influence. The abrogation of LH surges upon destruction of the SCN (Wiegand and Terasawa, 1982) or global knockout of Bmal1 (Chu et al., 2013) may indicate redundancy in this multioscillatory system, in that ablation of the pacemaker or cessation of clock function in all cell types has more devastating effects than interruption of circadian rhythms of any single component of the circuit.

The finding that Bmal1 expression in AVP cells is necessary for a normally timed surge is consistent with evidence that vasopressinergic outputs from the dorsal SCN “shell” play an important role in circadian timing of behavioral and endocrine outputs (Kalsbeek et al., 2006; Evans et al., 2015; Mieda et al., 2015, 2016). The role of vasopressin in generation of the LH surge is supported by demonstrations that disruption of estrous cycles in Clock mutant mice is accompanied by reduced AVP expression in SCN and lower AVP1a receptor mRNA in hypothalamus (Miller et al., 2006), and with the finding that injection of AVP into this region can restore LH surges to SCN-lesioned rats (Palm et al., 1999, 2001). The present results indicate that baseline LH is elevated in these conditional knockout animals, suggesting that clock function of vasopressin neurons may also have a role in negative feedback actions of estradiol. Disruption of the tonic mode of LH secretion may contribute to the action of Bmal1 deletion to compromise the surge. It is important to note that these experiments do not exclude a role of vasopressin neurons outside the SCN in control of the LH surge, as the conditional knockout procedure used in these studies is expected to eliminate clock function in all AVP cells, including not only parvicellular neurons elsewhere in the forebrain but also magnocellular neurons in supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei. Evidence that conditional deletion of the mutant tau allele in vasopressin cells normalizes the timing of the LH surge, however, supports the results from the AVPCre/+, Bmal1fl/fl mice and suggests that the relevant site is the circadian pacemaker. This result supports a model in which the output of vasopressin cells is sufficient to entrain cell-autonomous oscillations in kisspeptin, GnRH, and perhaps other populations to determine the timing of the LH surge. This role of AVP in the surge circuit may be specific, as the altered pattern of the LH surge in AVPCre/+, Bmal1fl/fl mice could not be explained by a change in the entrained phase angle of locomotor activity rhythms. It will be necessary to restrict Bmal1 knockout, and/or conditional deletion of the tau allele, to vasopressin cells of the SCN to establish unequivocally the role of this particular population in surge generation. This may be achieved through strategies in which Bmal1 expression is compromised only in specific cell types of the circadian pacemaker (Atasoy et al., 2012; Tso et al., 2017).

Conditional knockout of Bmal1 in Kisspeptin neurons also altered the timing and amplitude of the LH surge. The results suggest that circadian clock function in Kiss neurons plays an important role in the regulation of LH secretion, which may extend to both negative and positive feedback actions of E2. As is the case with the AVPCre/+, Bmal1fl/fl mice, it is possible that disruption of clock function in Kiss neurons in multiple areas contributes to changes in the pattern of LH secretion. Although the vasopressinergic projection of the SCN to the AvPV drives the activation of Kiss cells to trigger the surge, the arcuate population of Kiss cells controls the tonic pulsatile mode of LH secretion and steroidal negative feedback (Han et al., 2015; Dubois et al., 2016). In a model of pulsatile stimulation using a luciferase reporter, the activation of GnRH cells by kisspeptin was reduced in Bmal1-deficient mice (Choe et al., 2013). Coordination of relaxation of negative feedback with activation of positive feedback systems may be important to mounting a normal LH surge (Russo et al., 2015). Thus, Kiss neurons in the arcuate nucleus may also participate in circadian regulation of the LH surge and could contribute to the finding that timing of the LH surge is altered in KissCreBAC, Bmalfl/fl mice (Helena et al., 2015; Mittelman-Smith et al., 2016). Again, targeted deletion of Bmal1 in Kiss cells of AvPV versus arcuate will help to determine the important sites of clock function in kisspeptinergic control of the LH surge. Inhibitory effects of the arcuate Kiss population on GnRH secretion likely occur through the release of dynorphin from KnDY cells (Lehman et al., 2010). For both the Kiss and the AVP cells, peptides are co-released with GABA and possibly other small classical neurotransmitters. Manipulation of circadian function in either or both cell types may alter LH secretion through effects on the release of either the peptide, the co-released signal, or both.

The LH surge is most profoundly compromised in GnRHCreBAC, Bmal1fl/fl mice. This is consistent with findings of antiphase Per1 and Bmal1 expression in GnRH cells (Hickok and Tischkau, 2010) and with evidence from hamsters that the efficacy of Kiss administration to the preoptic area (POA) to activate GnRH cells varies with time of day (Williams et al., 2011) . As is the case for AVP and Kiss neurons, GnRH cells may be heterogeneous in distribution and function: they are found in a continuum running from the diagonal band to the anterior hypothalamus, may produce different isoforms of this decapeptide, and may not all be activated at the time of the LH surge (Lee et al., 1992; Herbison, 2014). Thus, circadian function in a particular subset of GnRH neurons may be of particular importance to surge generation. In light of noncircadian functions of Bmal1 in development, we cannot exclude the possibility that effects of Bmal1 deficiency in Kiss, GnRH, or perhaps AVP cells reflects disruption of sexual differentiation (Yang et al., 2016). It will be interesting to restrict conditional deletion of Bmal1 in these cell types to adulthood and/or to use chemogenetics or optogenetics to acutely silence AVP or Kiss cells to define a critical period for their depolarization.

Circadian function in cell types other than those examined in this study may also be important in determining the phase of the LH surge. A principal candidate is the VIP population of the SCN (Ohtsuka et al, 1988; van der Beek et al., 1993; Weick and Stobie 1995; Harney et al. 1996; Gerhold et al., 2005; Loh et al. 2014; Piet et al., 2015). These neurons project directly to GnRH cells and are thus positioned to regulate their discharge. Although conditional deletion of Bmal1 in VIP neurons may well affect the surge, it would be unclear whether such an effect arose from a change in their function as an SCN output or because of their role in entrainment to light and coupling of cell autonomous oscillators within the SCN (Aton et al., 2005). In addition to its function as an SCN output, vasopressin likely has intra-SCN functions (Mieda et al., 2015, 2016), and these could also contribute to the changes in the timing of the LH surge in AVPCre, Bmal1fl/fl mice described above. It is possible that direct (VIP) and indirect (AVP-kisspeptin) pathways from the SCN to the GnRH cells complement one another, perhaps having different roles in entraining subordinate oscillators versus triggering their depolarization. SCN projections to the subparaventricular region may also regulate the timing of the LH surge, as vasopressinergic projections to the dorsomedial subparaventricular zone may regulate neurons that in turn project to the medial preoptic area (Vujovic et al., 2015). The phase of LH secretion may also be regulated by circadian function of any of multiple peptidergic cell types including GnIH, hypocretin, melanin concentrating hormone (MCH), cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART), ß-Klotho, β-endorphin, and prokineticin 2 and be influenced by the timing of GABAergic and glutamatergic input to GnRH neurons (Christian and Moenter, 2010).

These experiments were restricted to the interval between ZT9 and ZT15, the time window in which LH surges occur in wild-type mice. It will be necessary to examine LH secretion at other times in order to determine whether LH surges occur in these Cre lines earlier in the day or later in the night. Despite the effects of these genetic constructs on the timing and pattern of the LH surge, all are fertile. Indeed, even mice with a global knockout of Bmal1 experience relatively subtle disruptions of the estrous cycle and ovulate, despite the absence of LH surges (Chu et al., 2013). Likewise, estrous cycles continue in mice in which kisspeptin neurons are eliminated by Kiss-Cre–driven diphtheria toxin (Mayer and Boehm, 2011). This may be attributable to compensation during development, as acute ablation of Kiss neurons in adulthood results in constant estrus. It is also important to recognize that the present experiments were restricted to ovariectomized animals in which the only gonadal steroid available to control LH secretion was estradiol. Circadian function in any or all of the cell types studied here may be less important when preovulatory progesterone is available to influence the timing and amplitude of the LH surge (DePaolo and Barraclough, 1979; Stephens et al., 2015; Leite et al., 2016). Finally, circadian rhythms in the ovary (Mereness et al., 2016), if not the pituitary (Chu et al., 2013), may contribute to the timing of ovulation. Despite this possible redundancy in the neural systems that regulate the LH surge, the present data indicate that circadian control of its timing is distributed among several cell types.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

These experiments were performed by Mr. Ajay Kumar. I thank Drs. Catherine Dulac, Michael Hastings, Andrew S. I. Loudon, and Bradley L. Lowell for generous supply of transgenic lines; Amanda Hageman for expert animal care; and Kevin Shen, Emma Sisson, and Yahaira Bermudez for assistance with PCR genotyping. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R21HD078863, R21NS099473, and RO1HL138551 to E.L.B.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author has no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary material is available for this article online.

REFERENCES

- Alexander MJ, Clifton DK, and Steiner RA (1985) Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide effects a central inhibition of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology 117:2134–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy D, Betley JN, Su HH, and Sternson SM (2012) Deconstruction of a neural circuit for hunger. Nature 488:172–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aton SJ, Colwell CS, Harmar AJ, Waschek J, and Herzog ED (2005) Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide mediates circadian rhythmicity and synchrony in mammalian clock neurons. Nat Neurosci 8(4):476–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittman EL (2012) Does the precision of a biological clock depend upon its period? Effects of the duper and tau mutations in Syrian hamsters. PLoS One 7:e36119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao S and Kriegsfeld LJ (2009) Daily changes in GT1-7 cell sensitivity to GnRH secretagogues that trigger ovulation. Neuroendocrinology 89:448–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassard D, Bu I, Poirel VK, Mendoza J, and Simonneaux V 2015. Evidence for a putative circadian Kiss-Clock in the hypothalamic AVPV in female mice. Endocrinol 156:2999–3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe HK, Kim H-D, Park SH, et al. (2013) Synchronous activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone gene transcription and secretion by pulsatile kisspeptin stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110:5677–5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian CA and Moenter SM (2008) Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide can excite gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in a manner dependent on estradiol and gated by time of day. Endocrinology 149:3130–3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian CA and Moenter SM (2010) The neurobiology of preovulatory and estradiol-induced gonadotropin-releasing hormone surges. Endocr Rev 31:544–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu A, Zhu L, Blum ID, Mai O, Leliavski A, Fahrenkrug J, Oster H, Boehm U, and Storch KF (2013) Global but not gonadotrope-specific disruption of Bmal1 abolishes the luteinizing hormone surge without affecting ovulation. Endocrinology 154:2924–2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson J, d’Anglemont de Tassigny X, Moreno AS, Colledge WH, and Herbison AE (2008) Kisspeptin-GPR54 signaling is essential for preovulatory gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron activation and the luteinizing hormone surge. J Neurosci 28:8691–8697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Iglesia HO, Blaustein JD, and Bittman EL (1995) The suprachiasmatic area in the female hamster projects to neurons containing estrogen receptors and GnRH. NeuroReport 6:1715–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Iglesia HO, Meyer J, and Schwartz WJ (2003) Lateralization of circadian pacemaker output: activation of left- and right-sided luteinizing releasing hormone neurons involves a neural rather than a humoral pathway. J Neurosci 23:7412–7414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Iglesia HO and Schwartz WJ (2006). Minireview: timely ovulation: circadian regulation of the female hypothalalmo-pituitary-gonadal axis. Endocrinology 147:1148–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePaolo LV and Barraclough CA (1979) Dose dependent effects of progesterone on the facilitation and inhibition of spontaneous gonadotropin surges in estrogen treated ovariectomized rats. Biol Reprod 21:1015–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois SL, Wolfe A, Radovick S, Boehm U, and Levine JE (2016) Estradiol restrains prepubertal gonadotropin secretion in female mice via activation of ERα in kisspeptin neurons. Endocrinol 157:1546–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JA, Suen T-C, Callif BL, et al. (2015) Shell neurons of the master circadian clock coordinate the phase of tissue clocks throughout the brain and body. BMC Biology 13:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett JW and Sawyer CH (1950) A 24-hour periodicity in the “LH-release apparatus” of female rats, disclosed by barbiturate sedation. Endocrinology 47:198–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhold LM, Rosewell KL, Wise PM (2005) Suppression of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in the suprachiasmatic nucleus leads to aging-like alterations in cAMP rhythms and activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Neurosci 25:62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JMA, Chan BPK, Roy D, Cai F, and Belsham DD (2003) Expression of circadian rhythms genes in gonadotropin releasing hormone-secreting GT1-7 neurons. Endocrinol 144:5285–5292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SY, McLennan T, Czieselsky K, and Herbison AE (2015) Selective optogenetic activation of arcuate kisspeptin neurons generates pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:13109–13114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harney JP, Scarbrough K, Rosewell KL, and Wise PM (1996) In vivo antisense antagonism of vasoactive intestinal peptide in the suprachiasmatic nuclei causes aging-like changes in the estradiol-induced luteinizing hormone and prolactin surges. Endocrinology 137:3696–3701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helena CV, Toprorikoba N, Kalil B, Stathopoulos AM, Porgrbna VV, Carolino RO, Anselmo-Franci JA, and Bertram R (2015) KNDy neurons modulate the magnitude of the steroid-induced luteinizing hormone surge in ovariectomied rats. Endocrinol 156:4200–4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE (2014) Physiology of the adult gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal network. In: Plant T and Zeleznik AJ, editors. Knobil and Neill’s Physiology of Reproduction. 4th ed. San Diego (CA): Academic Press. p. 399–467. [Google Scholar]

- Hickok JR and Tischkau SA (2010) In vivo circadian rhythms in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Neuroendocrinol 91:110–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann H, Larder R, Lee JS, Hu RJ, Trang C, Devries BM, Clark DD, and Mellon PL (2019) Differential CRE expression in Lhrh-cre and GnRH-cre alleles and the impact on fertility in Otx2-flox mice. Neuroendocrinology 108:328–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath TL, Cela V, and Van der Beek EM (1998) Gender-specific apposition between vasoactive intestinal peptide-containing axons and gonadotrophin-releasing hormone-producing neurons in the rat. Brain Res 1998;795:277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husse J, Zhou X, Shostak A, Oster H, and Eichele G (2011) Synaptotagmin10-Cre, a driver to disrupt clock genes in the SCN. J Biol Rhythms 26:379–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamatianos T, Kalló I, Goubillon ML, and Coen CW (2004) Cellular expression of V1a vasopressin receptor mRNA in the female rat preoptic area: effects of oestrogen. J Neuroendocrinol 16:525–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsbeek A, Palm IF, LaFleur SE, Scheer FAJL, Perreau-Lenz S, Ritter M, Kreier F, Cailotto C, and Buijs RM (2006) SCN outputs and the hypothalamic balance of life. J Biol Rhythms 21:458–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura F, Mitsugi N, Arita J, Akema T, and Yoshida K (1987) Effects of pre-optic injections of gastrin, cholecystokinin, secretin, vasoactive intestinal peptide and PHI on the secretion of luteinizing hormone and prolactin in ovariectomized estrogen-primed rats. Brain Res 410:315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krashes MJ, Shah P, Madara JC, Olson DP, Strochlic DE, Garfield AS, Vong L, Pei H, Watabe-Uchida M, Uchida N, et al. (2014) An excitatory paraventricular nucleus to AfRP neuron circuit that drives hunger. Nature 507:238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegsfeld LJ, Silver R, Gore AC, and Crews D (2002) Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide contacts on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons increase following puberty in female rats. J Neuroendocrinol 14:685–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WS, Smith MS, and Hoffman GE (1992) cFos activity identifies recruitment of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons during the ascending phase of the proestrous luteinizing hormone surge. J Neuroendocrinol 4:161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legan SJ and Karsch FJ (1975) A daily signal for the LH surge in the rat. Endocrinology 96:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman MN, Coolen LM, and Goodman RL. (2010) Minireview: kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) cells of the arcuate nucleus: a central node in the control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology 151:3479–3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite CM, Kalil B, Uchoa ET, Antunes-Rodrigues J, Elias LKL, Levine JE, and Anselmo-Franci JA (2016) Progesterone-induced amplification and advancement of GnRH/LH surges are associated with changes in kisspeptin system in preoptic area of estradiol-primed female rats. Brain Res 1650:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh DH, Kuljis DA, Azuma L, Wu Y, Truong D, Wang HB, and Colwell CS (2014) Disrupted reproduction, estrous cycle, and circadian rhythms in female mice deficient in vasoactive intestinal peptide. J Biol Rhythms 29:355–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudon ASI, Meng QJ, Maywood ES, Bechtold DA, Boot-Handford RP, and Hastings MH (2007) The biology of the circadian Ck1e tau mutation in mice and Syrian hamsters: a tale of two species. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol 72:261–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer C and Boehm U (2011) Female reproductive maturation in the absence of kisspeptin/GPR54 signaling. Nat Neurosci 14:704–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q-J, Logunova L, Maywood ES, Gallego M 3, Lebiecki J 1, Brown TM 1, Sládek M 2, Semikhodskii AS 1, Glossop NRJ 1, Piggins HD 1, et al. (2008) Setting clock speed in mammals: the CK1e tau mutation in mice accelerates circadian pacemakers by selectively destabilizing PERIOD proteins. Neuron 58:78–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereness AL, Murphy ZC, Forrestel AC, Butler S, Ko C, Richards JS, and Sellix MT (2016) Conditional deletion of Bmal1 in ovarian theca cells disrupts ovulation in female mice. Endocrinol 157:913–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieda M, Okamoto H, and Sakurai T (2016) Manipulating the cellular circadian period of arginine vasopressin neurons alters the behavioral circadian period. Curr Biol 26:2535–2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieda M, Ono D, Hasegawa E, Okamoto H, Honma K-I, Honma S, and Sakurai T (2015). Cellular clocks in AVP neurons of the SCN are critical for interneuronal coupling regulating circadian behavior rhythm. Neuron 85:1103–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BH, Olson S, Turek FW, Levine JE, Horton TH, and Takahashi JS (2004) Circadian clock mutation disrupts estrous cyclicity and maintenance of pregnancy. Curr Biol 14:1367–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BH, Olson SL, Levine JE, Turek FW, Horton TH, and Takahashi JS (2006) Vasopressin regulation of the proestrous luteinizing hormone surge in wild-type and Clock mutant mice. Biol Reprod 75:778–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman-Smith MA, Krajewski-Hall SJ, McMullen NT, and Rance NE (2016) Ablation of KNDy Neurons Results in Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism and Amplifies the Steroid-Induced LH Surge in Female Rats. Endocrinology. 157:2015–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka S, Miyake A, Nishizaki T, Tasaka K, and Tanizawa O (1988) Vasoactive intestinal peptide stimulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone release from rat hypothalamus in vitro. Acta Endocrinol 117:399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm IF, Van Der Beek EM, Wiegant VM, Buijs RM, and Kalsbeek A (1999) Vasopressin induces a luteinizing hormone surge in ovariectomized, estradiol-treated rats with lesions of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience 93:659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm IF, Van der Beek EM, Wiegant VM, Buijs RM, and Kalsbeek A (2001) The stimulatory effect of vasopressin on the luteinizing hormone surge in ovariectomized, estradiol-treated rats is time-dependent. Brain Res 901:109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piet R, Dinckley H, Lee K, and Herbison AE (2016) Vasoactive Intestinal peptide excites GnRH neurons in male and female mice. Endocrinology 157:3621–3630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piet R, Fraissenon, Boehm U, and Herbison AE (2015) Estrogen permits vasopressin signaling in preoptic kisspeptin neurons in the female mouse. J Neurosci 35:6881–6892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Nestor CC, Zhang C, Padilla SL, Palmiter RD, Kelly MJ, and Ronnekleiv OK (2016). High-frequency stimulation-induced peptide release synchronizes arcuate kisspeptin neurons and excites GnRH neurons. eLife 5:e16246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnekleiv OK, Zhang C, Bosch MA, and Kelly MJ (2014) Kisspeptin and GnRH neuronal excitability: molecular mechanisms driven by 17b-estradiol. Neuroendocrinology 102:184–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo KA, La JL, Stephens SBZ, Poling MC, Padgaonkar NA, Jennings KJ, Piekarski DJ, Kauffman AS, and Kriegsfeld LJ (2015). Circadian control of the female reproductive axis through gated responsiveness of the RFRP-3 system to VIP signaling. Endocrinol 156:2608–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson WK, Burton KP, Reeves JP, and McCann SM (1981) Vasoactive intestinal peptide stimulates luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone release from median eminence synaptosomes. Regul Pept 2:253–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmoneaux V and Bahougne T (2015) A multi-oscillatory circadian system times female reproduction. Front Endocrinol 6:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smarr BL, Gile JJ, and de la Iglesia HO (2013) Oestrogen-independent circadian clock gene expression in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus in female rats: possible role as an integrator for circadian and ovarian signals timing the luteinising hormone surge. J Neuroendocrinol 25:1273–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smarr BL, Morris E, and de la Iglesia HO (2012) The dorsomedial suprachiasmatic nucleus times circadian expression of Kiss1 and the luteinizing hormone surge. Endocrinology 153:2839–2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Popa SM, Clifton DK, Hoffman GE, and Steiner RA (2006) Kiss1 neurons in the forebrain as central processors for generating the preovulatory luteinizing hormone surge. J Neurosci 26:6687–6694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Jennes L, and Wise PM ( 2000) Localization of the VIP2 receptor protein on GnRH neurons in the female rat. Endocrinology 141:4317–4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyllie NJ, Chesham JE, Hamnett R, Maywood ES, and Hastings MH (2016) Temporally chimeric mice reveal flexibility of circadian period-setting in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(13): 3657–3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens SBZ, Tolson DP, Rouse ML, Poling MC, Hashimoto-Partyka MK, Mellon PL, and Kauffman AS (2015) Absent progesterone signaling in kisspeptin neurons disrupts the LH surge and impairs fertility in female mice. Endocrinology 156:3091–3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyn FJ, Wan Y, Clarkson J, Veldhuis JD, Herbison AE, and Chen C (2013) Development of a methodology for and assessment of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in juvenile and adult male mice. Endocrinology 154:4939–4945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch K-F, Paz C, Signorovitch J, Raviola E, Pawlyk B, Li T, and Weitz CJ (2007) Intrinsic circadian clock of the mammalian retina: importance for retinal processing of visual information. Cell 130:730–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann JM and Turek FW (1985) Multiple circadian oscillators regulate the timing of behavioral and endocrine rhythms in female golden hamsters. Science 228:898–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonsfeldt KJ and Chappel PE (2012) Clocks on top: the role of the circadian clock in the hypothalamic and pituitary regulation of endocrine physiology. Mol Cell Endocrinol 349:3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonsfeldt KJ, Goodell CP, Latham KL, Chappell PE 2011. Oestrogen induces rhythmic expression of the kisspeptin-1 receptor GPR54 in hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone-secreting GT1-7 cells. J Neuroendocrinol 23:823–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tso CF, Simon T, Greenlaw AC, Puri T, Mieda M, and Herzog ED (2017) Astrocytes regulate daily rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and behavior. Curr Biol 27:1055–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Beek EM, Horvath TL, Wiegant VM, Van den Hurk R, and Buijs RM (1997) Evidence for a direct neuronal pathway from the suprachiasmatic nucleus to the gonadotropin-releasing hormone system: combined tracing and light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical studies.J Comp Neurol 384: 569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Beek EM, Swarts HJ, and Wiegant VM (1999) Central administration of antiserum to VIP delays and reduces LH and prolactin surges in ovariectomized, estrogen-treated rats. Neuroendocrinology 69: 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Beek EM, van Oudheusden HJ, Buijs RM, van der Donk HA, van den Hurk R, and Wiegant VM (1994) Preferential induction of c-fos immunoreactivity in vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-innervated gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons during a steroid-induced luteinizing hormone surge in the female rat. Endocrinology 134:2636–2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Beek EM, Wiegant VM, van der Donk HA, van den Hurk R, and Buijs RM (1993) Lesions of the supra-chiasmatic nucleus indicate the presence of a direct VIP-containing projection to gonadotrophin-releasing hormone neurons in the female rat. J Neurodocrinol 5:137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vinne V, Swoap SJ, Vajtay TJ, and Weaver DR (2018) Desynchrony between brain and peripheral clocks caused by CK1d/e disruption in GABA neurons does not lead to adverse metabolic outcomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E2437–E2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vida B, Deli L, Hrabovszky E, Kalamatianos T, Caraty A, Coen CW, Liposits Z, and Kalló I (2010) Evidence for suprachiasmatic vasopressin neurons innervating kisspeptin neurones in the rostral periventricular area of the mouse brain: regulation by oestrogen. J Neuroendocrinol 22:1032–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan E, Samson W, Said S, and McCann SM (1979) Vasoactive intestinal peptide: evidence for a hypothalamic site of action to release growth hormone, luteinizing hormone and prolactin in conscious ovariectomized rats. Endocrinol 104:53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujovic N, Gooley JJ, Jhou TC, and Saper CB (2015) Projections from the subparaventricular zone define four channels of output from the circadian timing system. J Comp Neurol 523:2714–2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang O (2012) Glucocorticoids regulate kisspeptin neurons during stress and contribute to infertility and obesity in leptin-deficient mice [dissertation]. Boston (MA): Harvard University. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9453704. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver DR, van der Vinne V, Giannaris EL, Vajtay TJ, Holloway KL, and Ancelet C (2018) Functionally complete excision of conditional alleles in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus by Vgat-ires–Cre. J Biol Rhythms 33:179–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weick RF and Stobie KM (1995) Role of VIP in the regulation of LH secretion in the female rat. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 19:251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand SJ and Terasawa E (1982) Discrete lesions reveal functional heterogeneity of suprachiasmatic structures in regulation of gonadotropin secretion in the female rat. Neuroendocrinology 34:395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams WP III, Jarjisian SG, Mikkelsen JD, and Kriegsfeld LJ (2011) Circadian control of kisspeptin and a gated GnRH response mediate the preovulatory luteinizing hormone surge. Endocrinology 152:595–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams WP III and Kriegsfeld LJ (2012) Circadian control of neuroendocrine circuits regulating female reproductive function. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 3:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Zhang C, Li X, Gong S, Hu R, Balasubramanian R, Crowley WF, Hastings MH, and Zhou QY (2014). Signaling role of prokineticin 2 on the estrous cycle of female mice. PLoS One 9(3):e90860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Kaga S, Tsubomizu J, Fujisaki J, Mochiduki A, Sakai T, Tsukamura H, Maeda K, Inoue K, and Adachi AA (2011) Circadian transcriptional factor DBP regulates expression of Kiss1 in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus. Mol Cell Endocrinol 339:90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Chen L, Grant GR, Paschos G, Song WL, Musiek ES, Lee V, McLoughlin SC, Grosser T, Cotsarelis G, et al. (2016) Timing of expression of the core clock gene Bmal1 influences its effects on aging and survival. Science Transl Med 8:324ra16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip SH, Boehm U, Herbison AE, and Campbell RE (2015) Conditional viral tract tracing delineates the projections of distinct kisspeptin neuronal populations to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons in the mouse. Endocrinology 156:2582–2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H, Enquist LW, and Dulac C (2005) Olfactory inputs to hypothalamic neurons controlling reproduction and fertility. Cell 123:669–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.