Abstract

Atrazine, a herbicide widely used in corn production, is a frequently detected groundwater contaminant. Fourteen bacterial strains able to use this herbicide as a sole source of nitrogen were isolated from soils obtained from two farms in Canada and two farms in France. These strains were indistinguishable from each other based on repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR genomic fingerprinting performed with primers ERIC1R, ERIC2, and BOXA1R. Based on 16S rRNA sequence analysis of one representative isolate, strain C147, the isolates belong to the genus Pseudaminobacter in the family Rhizobiaceae. Strain C147 did not form nodules on the legumes alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), birdsfoot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus L.), red clover (Trifolium pratense L.), chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), and soybean (Glycine max L.). A number of chloro-substituted s-triazine herbicides were degraded, but methylthio-substituted s-triazine herbicides were not degraded. Based on metabolite identification data, the fact that oxygen was not required, and hybridization of genomic DNA to the atzABC genes, atrazine degradation occurred via a series of hydrolytic reactions initiated by dechlorination and followed by dealkylation. Most strains could mineralize [ring-U-14C]atrazine, and those that could not mineralize atrazine lacked atzB or atzBC. The atzABC genes, which were plasmid borne in every atrazine-degrading isolate examined, were unstable and were not always clustered together on the same plasmid. Loss of atzB was accompanied by loss of a copy of IS1071. Our results indicate that an atrazine-degrading Pseudaminobacter sp. with remarkably little diversity is widely distributed in agricultural soils and that genes of the atrazine degradation pathway carried by independent isolates of this organism are not clustered, can be independently lost, and may be associated with a catabolic transposon. We propose that the widespread distribution of the atrazine-degrading Pseudaminobacter sp. in agricultural soils exposed to atrazine is due to the characteristic ability of this organism to utilize alkylamines, and therefore atrazine, as sole sources of carbon when the atzABC genes are acquired.

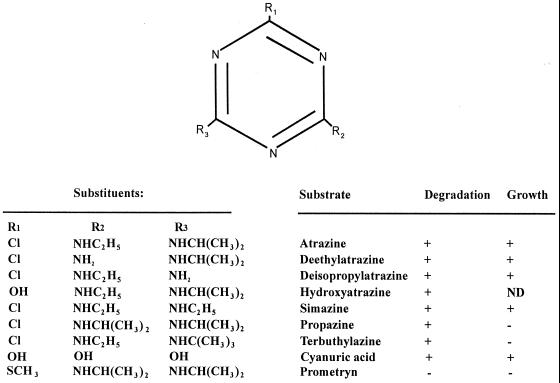

The agricultural herbicide atrazine (2-chloro-4-ethylamino-6-isopropylamino-1,3,5-triazine) (Fig. 1 shows the structure of this compound) is used extensively in many parts of the world to control a variety of weeds, primarily during production of corn (61). There is some evidence which suggests that atrazine may be an endocrine-disrupting chemical (12, 45). Trace levels of atrazine residues are frequently detected in surface and well water samples (24, 25, 29, 47, 57, 60). Once in aquifers, atrazine is persistent (1, 68), and thus there is considerable interest in and need to develop agricultural management practices that minimize atrazine pollution of surface water and groundwater resources.

FIG. 1.

Structures of s-triazine compounds used in this study. These compounds were tested for degradation and the ability to support growth of strain C147 as sole nitrogen sources as described in the text. ND, not determined.

Workers have isolated a variety of fungi (37, 46) and bacteria (4, 21, 44, 48) which dealkylate and dechlorinate atrazine but do not mineralize the s-triazine ring. More recently, however, there have been several reports of rapid atrazine mineralization in agricultural soils (3, 27, 64, 66), and a variety of atrazine-mineralizing bacteria, including members of the genera Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, Acinetobacter, and Agrobacterium, have been isolated from soils that have come in contact with this chemical (2, 7, 43, 44, 54, 58, 70). These bacteria commonly initiate atrazine degradation by a hydrolytic dechlorination reaction. The genes encoding an atrazine chlorohydrolase (atzA) and the enzymes of two amidohydrolytic reactions (atzB and atzC), which together convert atrazine to the ring cleavage substrate cyanuric acid, have been cloned from Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP (6, 16, 55). Cyanuric acid is converted by another set of amidohydrolase enzymes to biuret and then to urea, which is mineralized (10). The genes encoding the enzymes which catalyze these reactions are generally widespread, highly conserved, and plasmid borne (18, 19, 36).

We are interested in agricultural management practices that influence the persistence of pesticides, and we have recently initiated a study to examine the relationship of herbicide treatment history to atrazine persistence and biodegradation pathways in agricultural soils and watersheds (62). Persistence generally declines in response to herbicide use, suggesting that exposure of soil to atrazine enhances the abundance and activity of atrazine-degrading bacteria (3, 50, 53). The objectives of the work reported here were to isolate bacteria from soils which rapidly degrade atrazine and to characterize these bacteria with respect to their diversity, identity, and mechanism of atrazine degradation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling sites.

The bacteria described in this paper were isolated from soils obtained from four farms. Two of the soils were obtained from sites in Canada; one of these soils, the site 1 soil (64), was a loam soil (pH 5.9, 3.0% organic matter) obtained from a site located near Ottawa, Ontario, and the other, the site 2 soil, was a loam soil (pH 6.0, 1.4% organic matter) obtained from a site located near Ste.-Hyacinthe, Québec. Two calcareous soils, the site 3 soil (30) (pH 8.4, 1.6% organic matter) and the site 4 soil (3) (pH 8.2, 1.9% organic matter), were obtained from sites located on the outskirts of Paris, France. All four soils had been used to grow corn and had been treated with atrazine for weed control according to normal farming practice for at least 20 years. Five replicate soil cores were obtained at each sample site, pooled, homogenized, and stored without drying at 4°C for up to 6 months before the soil was used for enrichment and isolation of atrazine-degrading bacteria.

Enrichment, isolation, characterization, and maintenance of atrazine-degrading bacteria.

Enrichment preparations consisting of a mineral salts medium containing 25 mg of atrazine per liter as the sole nitrogen and carbon source were inoculated with soil (25%, wt/vol) and incubated aerobically with shaking at 30°C. The mineral salts medium contained (per liter) 1.6 g of K2HPO4, 0.4 g of KH2PO4, 0.2 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.1 g of NaCl, 0.02 g of CaCl2, and 1 ml of a trace metal solution (40) that had been modified by removing the iron and EDTA. Following autoclaving, the medium was supplemented with 1 ml of a filter-sterilized (pore size, 0.2 μm; Acrodisc; Gelman Sciences) vitamin solution (42) per liter and 5 mg FeSO4 · 6H2O per ml. Atrazine concentrations were monitored by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (see below), and enrichment cultures which degraded the herbicide were streaked onto an agar medium (atrazine mineral salts [AMS]) consisting of the mineral salts medium supplemented with 16 g of agar (Difco) per liter, 1 g of trisodium citrate per liter, 1 ml of methanol (solvent carrier for atrazine) per liter, and 0.5 g of atrazine per liter. This atrazine concentration is greater than the solubility limit, 33 mg/liter, and results in a chalky suspension (43). Colonies which developed cleared zones in the atrazine-containing mineral salts medium agar were purified and routinely maintained on this medium; in some cases the medium was supplemented with 1 g of ethylamine hydrochloride per liter, which supported abundant growth. Isolates were stored frozen in 15% glycerol at −70°C.

The cellular and colonial morphologies of the atrazine-degrading strains was determined by using conventional methods (28). The abilities of the organisms to nodulate alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), birdsfoot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus L.), red clover (Trifolium pratense L.), chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), and soybean (Glycine max L.) were determined by using a method described by Prévost et al. (52). Legume roots inoculated with the test bacteria were compared with uninoculated negative controls and with the roots of legumes inoculated with the following nodulating rhizobia: Sinorhizobium meliloti A2 Balsac, Mesorhizobium loti L3, Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii TL-5, Mesorhizobium ciceri UPM Ca7T, and Bradyrhizobium japonicum 61 A153 (=532C).

s-Triazine compound degradation.

Degradation of s-triazine substrates was studied by performing an HPLC analysis of supernatants obtained from cultures that were grown for 4 days at 30°C (50-ml portions in 250-ml flasks shaken at 150 rpm with a rotary shaker) in mineral salts medium containing 1 g of glucose per liter and 20 mg of a substrate per liter as the sole nitrogen source. In some cases cell suspensions were incubated anaerobically in serum vials sealed with grey butyl rubber stoppers by repeatedly evacuating the headspace under a vacuum and backfilling with a manifold to atmospheric pressure with nitrogen gas. Growth on these substrates was monitored by determining the absorbance at 600 nm. Degradation of s-triazines by cell extracts was studied by mixing preheated (30°C) aqueous solutions containing a test substrate with preheated cell extract. Cell extracts of batch-grown cells were prepared by sonicating (four times, 2.5 min each, with 30-s rest intervals) the cells in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and then removing the undisrupted cells by centrifugation (12,000 × g, 12 min). The aqueous samples used for HPLC analysis of the parent compound and the metabolites were prepared by adding methanol (final concentration, 50%) to cell suspensions or cell extracts and removing the precipitated debris by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 4 min).

Chemicals and analytical methods.

Analytical grade triazine herbicides and metabolites (Fig. 1) were gifts from Novartis Crop Protection Canada Inc. (Guelph, Ontario, Canada) or were purchased from Chem Service Inc. (West Chester, Pa.). [ring-U-14C]atrazine (specific activity, 4.5 mCi/mmol; radioactive purity, 95%) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). Parent compounds and transformation products were analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC by using a C18 column and an instrument equipped with a UV detector (set at 220 nm) coupled in series with a radioactivity detector (64). The solvent used was 70% methanol–30% 5 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 9.0) (solvent system 1) or 50% methanol–50% 10 mM ammonium acetate (solvent system 2). The radioactivities of the samples were measured by using Universol scintillation cocktail (ICN, Costa Mesa, Calif.) and a model LS5801 liquid scintillation counter (Beckman, Irvine, Calif.); an external standard was used for quench correction. Mass spectra were determined by the electron impact method with a Finnigan-MAT 8230 mass spectrometer at an ionizing voltage of 70 eV. Metabolites were isolated and purified in preparation for the mass spectral analysis by fractionating culture filtrates with HPLC, evaporating the liquid under a stream of nitrogen, and taking up the final sample in methanol. Protein was quantified by the Bradford assay (8).

rep-PCR fingerprinting.

Fingerprints of bacterial genomic DNA were prepared by using repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (rep-PCR) and primers corresponding to the enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus sequence (primers ERIC1R and ERIC2) (31) and the BOX repetitive sequence (primer BOXA1R) (67). DNA amplification was carried out with an Omnigene thermocycler (Hybaid Ltd., Teddington, United Kingdom) by using procedures modified from the procedures described by Pooler et al. (51). The following program was used: denaturation for 3 min at 94°C; 30 cycles consisting of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 3 min; and a final extension step consisting of 72°C for 5 min and 30°C for 1 min. Each 25-μl reaction mixture contained 1× PCR buffer (Promega, Madison, Wis.), 3 mM MgCl2, 2.5 μg of gelatin, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 0.2 mM, 50 pmol of each primer (or 100 pmol of primer BOXA1R), 0.2 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (1 U) (Promega), and 50 ng of template (purified total genomic DNA adjusted to a concentration of 5 ng/μl). The PCR products were electrophoretically separated on 1.5% agarose (Sigma)–Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) gels and stained with ethidium bromide (2 mg/liter) in order to visualize DNA bands (56). Duplicate independent PCR were performed to ensure that the profiles were consistent.

DNA manipulation and hybridization procedures.

Bacterial genomic DNA and plasmid DNA were isolated and purified by using a QIAamp tissue kit and a Qiagen plasmid preparation kit (Qiagen Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), respectively.

Probes for the atzA, atzB, and atzC genes were prepared from plasmids pMD4, pATZ-2, and pTD-2, respectively (6, 16, 55). A probe for IS1071 was prepared from plasmid pBRH4 (69). Purified plasmids were digested with restriction enzymes (pMD4, ApaI plus PstI; pATZ-2, BglII plus EcoRI; pTD-2, ClaI plus HincII; pBRH4, HindIII) by standard procedures (56). After being electrophoretically separated in 1% low-melting-point multipurpose agarose (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Laval, Quebec, Canada), a 0.6-kb internal fragment of the atzA gene, a 1.2-kb internal fragment of the atzB gene, a 0.75-kb internal fragment of the atzC gene, and a 1.2-kb internal fragment of IS1071 were extracted by using an Agarose Gel DNA extraction kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The purified fragments were labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) by random priming by using a DIG High Prime DNA labeling and detection starter kit II (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) as specified by the manufacturer.

The procedures used to prepare dot blots (200 ng of genomic DNA/dot) and Southern blots were the procedures described by Roche Molecular Biochemicals or by Sambrook et al. (56). DNA that was subjected to electrophoresis on agarose gels was transferred to a Hybond N nylon membrane (Amersham, Oakville, Ontario, Canada) by the standard capillary method (56). The DNA then was cross-linked to the membrane with a UV cross-linker (UVP, San Gabriel, Calif.). Hybridized DNA was visualized by exposing the blots to X-OMAT AR film (Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.).

Bacterial plasmid DNA enriched by the method of Kado and Liu (34) was separated from chromosomal DNA by agarose gel electrophoresis in 0.5% agarose–TBE at 32 V/cm for 20 h or by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) as previously described (14). The PFGE conditions used were electrophoresis for 6 h at 250 mA (constant current) and 13°C with a pulse time of 5 s, followed by electrophoresis for 16 h at 175 mA (constant current) with a pulse time of 15 s. The reference plasmids used to determine plasmid sizes were pGS9 (30 kb), pDC3000 (68 kb), and pR1drd19 (93 kb), and the conditions used to prepare Southern blots of the PFGE gels were the conditions described previously (14).

16S rRNA gene sequence determination and analysis.

Using a purified genomic DNA template, we amplified the entire 16S rRNA gene by using the universal primers described previously (39). The PCR product was purified and cloned into the pGEM-T vector system as recommended by the manufacturer (Promega Co.), and recombinant plasmids were purified by using a QIAprep miniprep kit (Qiagen Inc.). Both DNA strands of the insert were sequenced twice with an ABI Prism model 377 sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) by using flanking and internal primers (39). Sequences were analyzed and concatenated by using DNASTAR (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.). A multiple-sequence alignment was prepared by using CLUSTAL W (59), and phylogenetic trees were constructed with MEGA (38) by using the neighbor-joining method as calculated by the Jukes and Cantor method. A bootstrap confidence analysis was performed with 1,000 replicates.

The following organisms were included in the phylogenetic analysis (accession numbers are given in parentheses): strain IMB-1 (AF034798), Chelatobacter heintzii (AJ011762), strain ER2 (L20802), Aminobacter aganoensis (AJ011760), Aminobacter niigataensis (AJ011761), Aminobacter aminovorans (AJ011759), strain CC495 (AF107722), Mesorhizobium huakuii (D13431), Mesorhizobium mediterraneum (L38825), Mesorhizobium ciceri (U07934), Mesorhizobium loti (X67229), Phyllobacterium myrsinacearum (AJ011330), Pseudaminobacter sp. strain C147 (AF246220), Sinorhizobium meliloti (X67222), Sinorhizobium fredii (X67231), Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae (U29386), and Bradyrhizobium japonicum (D13430).

RESULTS

Characterization of atrazine-degrading bacteria from Canada and France.

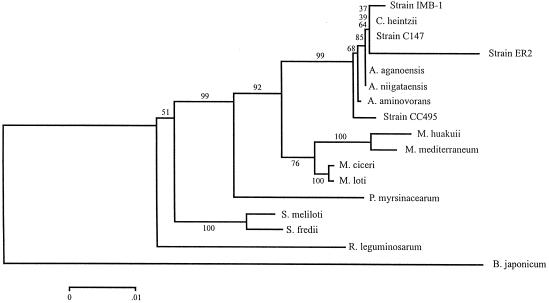

Fourteen atrazine-degrading bacterial strains were isolated from four farms, two in Canada and two in France (Table 1). All of these organisms were nonmotile gram-negative rods which, after 3 weeks of growth on AMS-atrazine medium, formed buff-colored, glistening, opaque, circular, raised colonies (diameter, 2 mm) with entire margins and a butyrous consistency. Their rep-PCR-derived genomic fingerprints, obtained by using primers ERIC1R, ERIC2, and BOXA1R, were identical, indicating that the organisms were very closely related to each other (data not shown). These fingerprints were clearly distinct from those of atrazine-degrading Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP (data not shown). When the sequence of the 16S rRNA gene from a representative isolate, strain C147, was aligned with sequences obtained from the GenBank database, the strain was identified as a Pseudaminobacter sp. (Fig. 2). The genus Pseudaminobacter is a genus in the family Rhizobiaceae, and its members are closely related to root-nodulating bacteria, including M. ciceri and M. loti (32, 35, 49). Strain C147 did not nodulate alfalfa, birdsfoot trefoil, red clover, chickpea, or soybean (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Sources of atrazine-degrading bacterial strains from Canadian and French farms; presence of atzA, atzB, atzC, and IS1071; and identities of the end products of atrazine metabolism by the strains

| Strain | Sourcea | Hybridization with probe forb:

|

End product of atrazine metabolismc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| atzA | atzB | atzC | IS1071 | |||

| C147 | 1 | + | + | + | + | CO2 |

| C151 | 1 | + | + | + | + | CO2 |

| C161 | 1 | + | + | + | + | CO2 |

| C163 | 1 | + | + | + | + | CO2 |

| C185 | 2 | + | + | + | + | CO2 |

| C186 | 2 | + | + | + | + | CO2 |

| C195 | 1 | + | + | + | + | CO2 |

| C197 | 1 | + | + | + | + | CO2 |

| C160 | 1 | + | − | + | + | Hydroxyatrazine |

| C150 | 1 | + | − | + | + | Hydroxyatrazine |

| C155 | 1 | + | − | − | − | Hydroxyatrazine |

| C156 | 1 | + | − | − | − | Hydroxyatrazine |

| C215 | 3 | + | − | − | − | Hydroxyatrazine |

| C218 | 4 | + | − | − | − | Hydroxyatrazine |

1, site 1 loam soil, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; 2, site 2 loam soil, Ste.-Hyacinthe, Quebec, Canada; 3, site 3 calcareous soil, Paris, France; 4, site 4 calcareous soil, Paris, France.

Based on dot-blot hybridization of total genomic DNA.

Based on conversion of [ring-U-14C]atrazine to 14CO2 or to radioactive products resolved by HPLC.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA sequence data, showing the relationship of strain C147 to the most closely related bacteria in the GenBank database. The bar indicates 0.01 substitution per nucleotide position. The numbers at the branch points are bootstrap values based on 1,000 samplings.

Mechanism of atrazine degradation and substrate range.

The atrazine-degrading isolates varied with respect to the end product of atrazine metabolism. Eight of the 14 isolates mineralized [ring-U-14C]atrazine to carbon dioxide in resting cell preparations (Table 1). The genomic DNA of these eight isolates hybridized in dot blots to the atzABC genes of Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP, suggesting that the organisms converted atrazine to the ring cleavage substrate cyanuric acid by using a pathway that has been shown to be highly conserved and widely distributed in other atrazine-degrading gram-negative genera (18). Using PCR primers described by de Souza et al. (18), we amplified and then sequenced a 405-bp conserved region of atzA in 11 of our isolates and Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP and found that the overall level of sequence identity was 99.2% (data not shown).

Six of our isolates did not mineralize atrazine but did accumulate stoichiometric amounts of a product that coeluted with a hydroxyatrazine standard (HPLC retention times, 4.7 min with solvent system 1 and 5.9 min with solvent system 2); none of these strains hybridized to atzB, and only strains C150 and C160 contained the atzC gene (Table 1). This metabolite accumulated transiently with the atrazine-mineralizing isolates. Strain C147, for example, converted [ring-U-14C]atrazine to the metabolite that coeluted with hydroxyatrazine, to a more hydrophilic product which eluted at the HPLC solvent front, and then to 14CO2, which accumulated stoichiometrically (data not shown). The metabolite which coeluted with hydroxyatrazine was recovered and purified by HPLC fractionation and then subjected to solid probe mass spectrometry. The compound had a molecular ion and a mass spectrum identical to the molecular ion and mass spectrum of an analytical-grade hydroxyatrazine standard (data not shown). Strain C147 grew readily with atrazine as the sole carbon and nitrogen source in batch culture, and in glucose-supplemented batch cultures containing equimolar concentrations of ammonium N or atrazine N the yields were comparable, indicating that all five nitrogen atoms in atrazine were utilized for growth (data not shown). The putative alkylamidohydrolase products ethylamine and isopropylamine also supported growth as sole sources of nitrogen or nitrogen and carbon (data not shown). Atrazine degradation did not require oxygen; dense resting cell suspensions of strain C147 adjusted to an A600 of 0.5 degraded atrazine in the presence and in the absence of oxygen at comparable rates, and cell extracts degraded atrazine aerobically with a specific activity of 5.0 ± 1.4 nmol/mg of protein · h (data not shown).

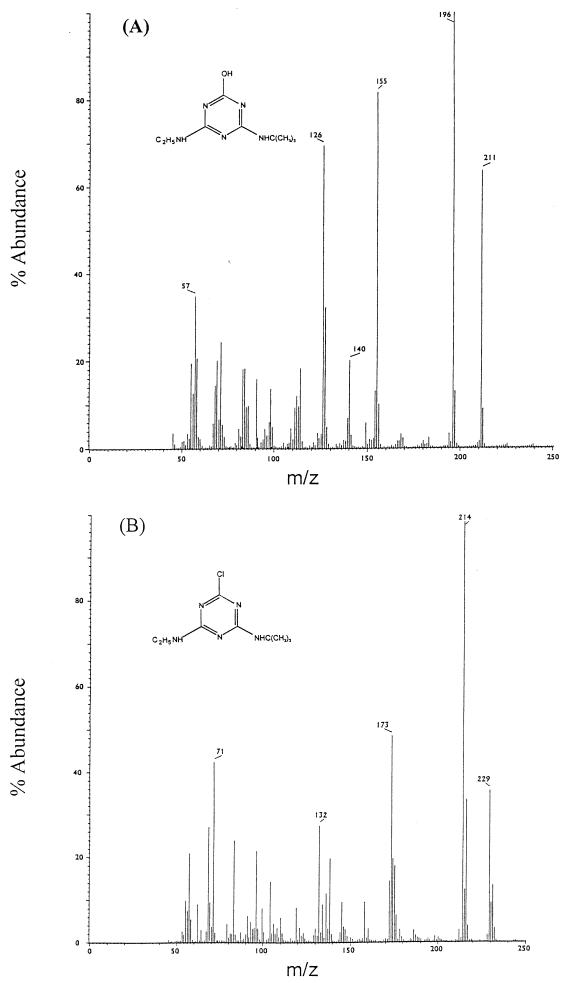

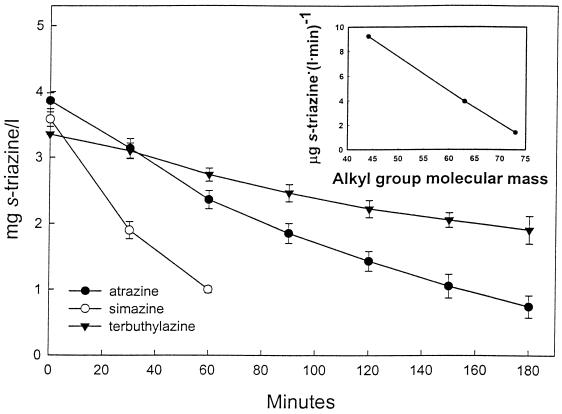

The s-triazine substrate range was tested by using strain C147. A number of chlorine-substituted triazines were degraded and supported growth as sole nitrogen sources (Fig. 1). The methylthio-substituted triazine herbicide prometryn was not degraded by either whole cells or cell extracts, which indicated that an inability to degrade the substrate was not solely due to a permeability barrier. HPLC analyses of filtrates prepared from cultures of strain C147 that were grown overnight in the presence of the herbicides simazine, propazine, and terbuthylazine revealed products that were more hydrophilic than the parent compounds. The retention times, determined with solvent system 1, were consistent with conversion of the s-triazine substrates to the corresponding hydroxytriazine products and were in the order anticipated based on the molecular masses of the parent compounds, as follows: simazine product (retention time, 4.2 min) < hydroxyatrazine (retention time, 4.5 min) < propazine product with a retention time of 5.4 min < terbuthylazine product with a retention time of 5.6 min. Enough product was obtained from the supernatant of a suspension of strain C147 supplemented with terbuthylazine that it could be isolated, purified, and subjected to a mass spectral analysis. The metabolite had a molecular ion (M+, base peak) at m/z 211 and major peaks at m/z 196, 169, 155, 126, 112, and 58. When this mass spectrum was compared with the mass spectrum of a terbuthylazine standard (Fig. 3), the molecular mass and fragmentation pattern of the metabolite were consistent with the structure of the expected product of hydrolytic dechlorination of terbuthylazine (loss of Cl with 35.45 mass units; acquisition of OH with 17 mass units), 6-hydroxy-N-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-N′-ethyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,-diamine. Taken together, the results suggest that degradation of the s-triazine herbicides was generally initiated by hydrolytic dechlorination of the parent compound to the corresponding 6-hydroxy products. The order for the degradation rates of simazine, atrazine, and terbuthylazine by resting cell suspensions of strain C147 was as follows: simazine > atrazine > terbuthylazine (Fig. 4). The structures of these three herbicides are identical except for one of the alkyl side chains, which is an ethylamino group (NC2H6) in simazine, an isopropylamino group (NC3H8) in atrazine, and a tert-isobutylamino group (NC4H10) in terbuthylazine (Fig. 1). The initial rate of degradation was correlated closely (r2 = 0.9995) with the molecular weight of the alkyl group (Fig. 4, inset).

FIG. 3.

Mass spectra of a terbuthylazine transformation product (A) obtained from culture extracts of strain C147 incubated in the presence of this herbicide and a terbuthylazine analytical standard (B). The mass spectrum of the transformation product is consistent with the hydroxytriazine structure indicated.

FIG. 4.

Degradation of the herbicides simazine, atrazine, and turbuthylazine by resting cell suspensions of strain C147. The inset shows the relationship between the molecular weight of the variable-length side chain (simazine, ethylamino; atrazine, isopropylamino; terbuthylazine, t-butylamino [Fig. 1]) and the initial rate of degradation.

Location and instability of atrazine degradation genes.

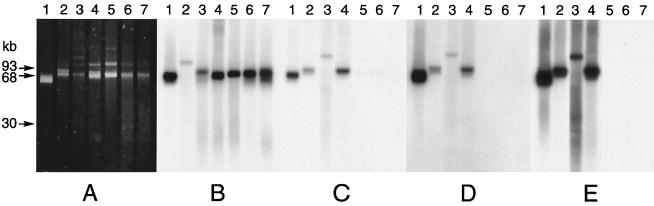

The atzABC genes were plasmid borne in all of the isolates examined. At least four patterns of gene distribution were evident based on our Southern blot analysis of purified plasmid DNA (Fig. 5). In Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP, all three genes were present in a single plasmid band, which is in agreement with the results of Sadowsky et al. (55), who reported that the three genes are on a 96-kb plasmid and that about 8.7 kb of DNA separates atzA and atzB. In strain C147, the atzA probe hybridized to a plasmid that had a higher molecular weight than the plasmid carrying atzBC, and in strain C185 the reverse was true. In strain C195, the atzB and atzC probes hybridized to a slightly smaller band than the band hybridized to atzA. There was no correlation between strain origin and the plasmid distribution of atzABC.

FIG. 5.

Southern blot analysis of plasmid DNA from atrazine-degrading bacteria. (A) Purified plasmids subjected to horizontal agarose electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. A blot of the gel was hybridized with DIG-labeled atzA (B), atzB (C), atzC (D), or IS1071 (E). Lanes 1, strain ADP; lanes 2, strain C147; lanes 3, strain C185; lanes 4, strain C195; lanes 5, strain C155; lanes 6, strain C215; lanes 7, strain C218.

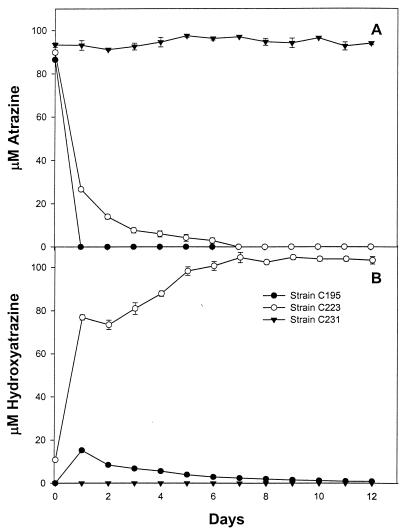

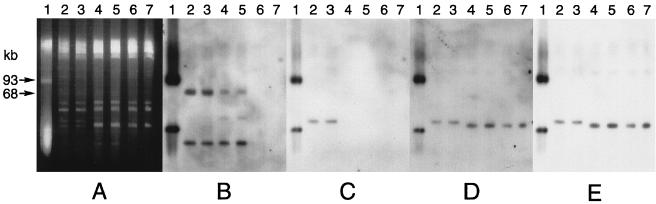

With some of our isolates we observed that the atrazine-degrading phenotype was lost when the isolate was subcultured, and this phenomenon was explored in more detail with strain C195. This isolate contained several plasmids, as determined by ethidium bromide staining of PFGE gels (Fig. 5A). The organism also carried a plasmid that was detectable only by DNA hybridization (Fig. 5B through E). The plasmids in the lower bands in Fig. 5C and in all of the Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP lanes were most likely open circular forms of the plasmids (14). When strain C195 was subcultured twice at weekly intervals on tryptone soy agar, we obtained a spontaneous mutant which cleared AMS medium but produced a crystalline precipitate on the agar surface. After this mutant, which was designated strain C223, was subcultured five more times on tryptone soy agar, we obtained another mutant, designated strain C231, which was not able to clear the agar medium. Strains C223 and C231 grew very slowly on atrazine mineral salts agar, but their growth rates were comparable to the growth rate of strain C195 when this medium was also supplemented with 1 g of ethylamine hydrochloride per liter. In liquid medium strains C195 and C223 metabolized atrazine at comparable initial rates, but the rate of atrazine degradation by the mutant decreased as the incubation progressed (Fig. 6A). Strain C231 did not metabolize atrazine at all. Strain C195 transiently produced a small amount of hydroxyatrazine, strain C223 accumulated a stoichiometric amount, and strain C231 did not produce any of this compound (Fig. 6B). In PFGE gels containing strain C195 total genomic DNA, atzB and atzC hybridized with a single plasmid band that was distinct from the band that hybridized with atzA (Fig. 7). The plasmid band that hybridized with atzBC also hybridized with IS1071. The loss of atzB in strain C223 was due to a deletion, which was detectable by a decrease in the size of the plasmid as revealed by hybridization with atzC or IS1071. Because the plasmid carrying atzA was not visible on ethidium bromide-stained gels, we do not know if the absence of this gene in strain C231 was due to a deletion or plasmid loss. Probes for atzA and atzB did not hybridize with strain C231 chromosomal DNA in PFGE gels or with total genomic DNA in dot blots, which indicated that these genes were completely lost from the genome.

FIG. 6.

Metabolism of atrazine by cell suspensions of atrazine-mineralizing wild-type strain C195 and spontaneous blocked mutant strains C223 and C231.

FIG. 7.

Distribution of atzABC and IS1071 on plasmids carried by atrazine-mineralizing strain C195 and the spontaneous mutant strains C223 and C231. (A) Plasmids separated by PFGE and stained with ethidium bromide. A blot of the gel was hybridized with DIG-labeled atzA (B), atzB (C), atzC (D), or IS1071 (E). Lanes 1, Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP; lanes 2 and 3, strain C195 (atzA+ atzB+); lanes 4 and 5, strain C223 (atzA+ atzB); lanes 6 and 7, strain C231 (atzA atzB).

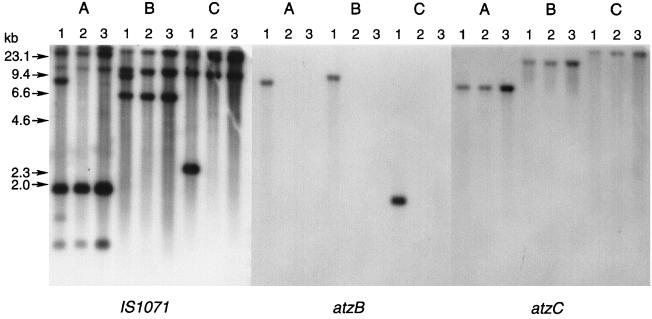

The loss of atzB in strain C195 was associated with the loss of a copy of IS1071 (Fig. 8). There were six bands that hybridized with IS1071 in EcoRI-digested total genomic DNA of strain C195. One of the fragments, which was 7 kb long, was the only fragment that hybridized with atzB. The loss of atzB in spontaneous mutant strain C223 was accompanied by the loss of this band without the appearance of a new IS1071-hybridizing band. A 9-kb band of BamHI-digested genomic DNA of strain C195 likewise hybridized with both genes and was absent in strains C223 and C231. The loss of atzA, which was carried on a plasmid which did not hybridize with IS1071 in strains C195 and C223, was not accompanied by a change in the IS1071 hybridization pattern compared with strain C231. A single IS1071-hybridizing BglII fragment and a separate atzB-hybridizing BglII fragment were not found in strain C223. atzC, which was present in all three strains, was present on a large IS1071-hybridizing BglII fragment and on large BamHI and EcoRI fragments which did not contain IS1071-hybridizing sequences.

FIG. 8.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of wild-type strain C195 and spontaneous mutant strains C223 and C231. Restriction digests (lanes A, EcoRI; lanes B, BamHI; lanes C, BglII) were probed with DIG-labeled IS1071, atzB, or atzC as indicated. Lanes 1, strain C195 (atzA+ atzB+); lanes 2, strain C223 (atzA+ atzB); lanes 3, strain C231 (atzA atzB). Members of the Rhizobiaceae have previously been shown to degrade some pesticides, including glyphosate (41).

DISCUSSION

Several lines of evidence indicated that our isolates degrade atrazine via a series of hydrolytic reactions catalyzed by a chlorohydrolase and alkylamidohydrolase enzymes. Atrazine was degraded in the presence or in the absence of oxygen, the major detectable metabolite was hydroxyatrazine, sequences that hybridized to atzA, atzB, and atzC were detected, a spontaneous cured mutant lacking atzA (strain C223) was not able to degrade atrazine, and cells were able to grow with the alkylaminohydrolase products ethylamine and isopropylamine as sole sources of carbon and nitrogen. Other s-triazine herbicides yielded metabolites whose HPLC elution times were consistent with the expected chlorohydrolase products, and, in the case of terbuthylazine, the mass spectrum of the isolated major metabolite was in agreement with this. The high level of sequence identity in a 405-bp conserved region of atzA is consistent with the levels of sequence identity previously found in atrazine-degrading Alcaligenes, Ralstonia, and Agrobacterium isolates, and these results extend the observation that the atzA-encoded chlorohydrolase is highly conserved and widely distributed in gram-negative atrazine-degrading bacteria (18). The widespread distribution is consistent with the frequent detection of hydroxyatrazine as a dominant atrazine transformation product in soils and with the anaerobic degradation of the herbicide in natural environmental samples when nitrate is present as the terminal electron acceptor (13).

It is remarkable that four farms, two in Canada and two in France, yielded 14 gram-negative atrazine-degrading bacteria which were siblings as determined by rep-PCR, a genomic fingerprinting method with a high level of taxonomic resolution (15). This result was unanticipated since the atrazine-degrading atzABC genes are plasmid borne in our isolates, are on a self-transmissible plasmid in Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP, are widely distributed in other atrazine-degrading bacteria belonging to a number of genera, including the genera Alcaligenes, Ralstonia, and Agrobacterium (18, 19), and therefore could be expected to be carried by a variety of bacteria in our soils. In our experiments, atrazine-degrading populations were enriched by several rounds of serial dilution in a medium which contained the herbicide as the sole carbon and nitrogen source. The cultures were subsequently plated onto an isolation medium that contained methanol, citrate, and atrazine as carbon sources and atrazine as the sole nitrogen source. All of our enrichment cultures yielded a member of the genus Pseudaminobacter, a recently described genus in the family Rhizobiaceae (35). Members of this genus characteristically are able to grow at the expense of alkylamines (9, 11, 63, 65). The ability to utilize either ethylamine or isopropylamine in combination with the “upper” atzABC atrazine degradation pathway could result in a catabolic pathway which would permit growth on the herbicide as the sole carbon source. In other studies workers have generally used enrichment cultures containing atrazine as the sole nitrogen source and other carbon sources, such as glucose or citrate. In some cases, these studies have yielded bacteria that are able to use alkylamino groups as both carbon and nitrogen sources (e.g., Clavibacter sp. strain ATZ1), and in other cases the workers have obtained bacteria that can use these side chains only as a nitrogen source (e.g., Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP) (17, 19, 43). Enrichment cultures are inherently biased and select for individuals that have a competitive advantage under the conditions employed. For example, populations of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-degrading bacteria isolated from enrichment cultures grossly underrepresented the diversity of populations which were isolated directly from soil (22). It may be that the atrazine degradation pathway of the Pseudaminobacter sp. was fully assembled only during the enrichment phase of our experiments. However, the ability to utilize the herbicide as a carbon source should be a significant selective advantage in atrazine-treated soil. Our results and the results of other recent studies indicate that atrazine-mineralizing bacteria are now widespread in soils that are subjected to conventional agricultural management practices and that the activity and abundance of these organisms may be enhanced by repeated application of the herbicide or by simple soil management practices, such as manure application (3, 50, 53, 64).

Several of our isolates, all of which contained atzABC, completely mineralized atrazine and converted ring 14C to 14CO2. Furthermore, all five nitrogen atoms in atrazine were used for growth, as shown by the growth yield experiments (data not shown). This finding is consistent with the finding that under carbon-limited conditions, Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP and Agrobacterium radiobacter incorporated ring 15N into biomass (5). Six of our isolates converted atrazine to hydroxyatrazine but were not able to further metabolize this intermediate. All of these isolates lacked atzB, and four of them also lacked atzC. We speculate that these genes were lost during early laboratory subculturing, since all isolates initially cleared atrazine-containing plates without production of a hydroxyatrazine precipitate. The instability of these genes was shown by the independent and sequential loss of atzB and then atzA in strain C195 (Fig. 7).

The ring cleavage substrate cyanuric acid is commonly metabolized through the actions of amidohydrolases, the genes for which are widely distributed and plasmid borne in bacteria that can use this compound as a nitrogen source (10, 23, 36). Presumably, these enzymes are present in strain C147, which mineralizes triazine ring carbon and utilizes triazine ring nitrogen for growth.

The range of triazine substrates hydrolyzed by our isolates is apparently different from the range of triazine substrates hydrolyzed by the purified chlorohydrolase of Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP, which reportedly does not hydrolyze the herbicide terbuthylazine (16). There may have been differences in the chlorohydrolase enzymes that were not revealed by the sequence variation in the conserved atzA region or by hybridization with an atzA probe and which changed the substrate specificity. We speculate that the inverse relationship between alkyl chain molecular mass and hydrolysis rate could be due to slower diffusion or transport of the substrate into cells, lower affinity for the active site of the s-triazine chlorohydrolase as the mass of the substrate increases, or more pronounced product inhibition by the larger hydroxylated s-triazine chlorohydrolase reaction products. Possible feedback inhibition by hydroxyatrazine was observed with strain C223, a blocked mutant which accumulates hydroxyatrazine, when it was compared to wild-type strain C195, which does not accumulate hydroxyatrazine (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the relative rates of s-triazine herbicide degradation by strain C147 (simazine > atrazine > terbuthylazine) are consistent with the relative levels of persistence of these herbicides in soils (26).

In our isolates the atzABC genes were frequently located on different plasmids that were different sizes. This genomic plasticity may be due at least in part to association of atzB and atzC with a transposable element. Several lines of evidence indicate that IS1071 is linked with atzB and atzC but not with atzA in our isolates. First, the presence of atzB or atzC, but not atzA, as revealed in dot blot hybridizations of total genomic DNA, was positively correlated with the presence of IS1071. Second, plasmids which carried atzA did not hybridize with IS1071, whereas bands which hybridized with atzB or atzC did. Third, restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses of total genomic DNA of wild-type strain C195 and spontaneous mutants that shed atzB and then atzA revealed linkage and simultaneous loss of the IS1071-hybridizing sequence and atzB but not atzA. Finally, in a cosmid library of plasmid-enriched DNA from strain C195 which we prepared, 25 of 26 clones that hybridized with atzB, 42 of 48 clones that hybridized with atzC, and none of 13 clones that hybridized with atzA also hybridized with IS1071 (data not shown). This variable distribution of genes on various plasmids is in contrast to the situation in Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP; in this strain the atzABC genes are not clustered but are carried on a single apparently stable 96-kb plasmid in which there is about 8.7 kb of DNA between atzA and atzB and atzC is located at least 25 kb away (55). The atzA gene is flanked by DNA that exhibits more than 95% sequence identity to IS1071 (55; B. M. Martinez-Zayas, M. L. de Souza, L. P. Wackett, and M. J. Sadowsky, Abstr. 99th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1999, abstr. Q-352, 1999). The association of the atz genes with IS1071, a component of transposons that mobilizes various pollutant-degrading catabolic pathways, including the p-sulfobenzoate and chlorinated benzoate pathways (20, 33), the high frequency of isolates with truncated pathways, the demonstrated instability of intermediate genes in the pathway, and the independent localization of atz genes on separate plasmids support the hypothesis that atrazine mineralization pathways in these organisms may be assembled from disparate genetic elements in microbial communities rather than from acquisition through horizontal transfer of a genetic “cassette” encoding the entire pathway.

Overall, our data revealed remarkable variability with respect to the location and stability of the atzA, atzB, and atzC genes in the genomes of atrazine-degrading bacteria. Furthermore, our data suggest that acquisition of these genes by members of the genus Pseudaminobacter, a genus that is widespread in soil and characteristically is able to use alkylamines, created a catabolic pathway that gave these organisms a selective advantage since they were able to use the herbicide as a carbon source.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Novartis Crop Protection.

We are grateful to J. Purdy and H.-P. Buser. We thank M. de Souza, M. Sadowsky, and L. P. Wackett for providing Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP, pMD4, and pATZ-2 and C. Wyndham for suggesting that we should test for IS1071 and providing the probe. We thank H. Bork for excellent technical assistance, D. Prévost for providing the rhizobia, and C. F. Drury, R. Lalande, and E. G. Gregorich for providing soil samples. Comments of R. Lalande and K. Leung on the manuscript are appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agertved J, Rugge K, Barker J F. Transformation of the herbicides MCPP and atrazine under natural aquifer conditions. Ground Water. 1992;30:500–506. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assaf N A, Turco R F. Accelerated biodegradation of atrazine by a microbial consortium is possible in culture and soil. Biodegradation. 1994;5:29–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00695211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barriuso E, Houot S. Rapid mineralization of the S-triazine ring of atrazine in soils in relation to soil management. Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28:1341–1348. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behki R M, Topp E, Dick W, Germon P. Metabolism of the herbicide atrazine by Rhodococcus strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1955–1959. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.6.1955-1959.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bichat F, Sims G K, Mulvaney R L. Microbial utilization of heterocyclic nitrogen from atrazine. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1999;63:100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boundy-Mills K L, de Souza M L, Mandelbaum R T, Wackett L P, Sadowsky M J. The atzB gene of Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP encodes the second enzyme of a novel atrazine degradation pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:916–923. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.916-923.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouquard C, Ouazzani J, Promé J-C, Michel-Briand Y, Plésiat P. Dechlorination of atrazine by a Rhizobium sp. isolate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:862–866. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.862-866.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein using the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connell Hancock T L, Costello A M, Lidstrom M E, Oremland R S. Strain IMB-1, a novel bacterium for the removal of methyl bromide in fumigated agricultural soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2899–2905. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.2899-2905.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook A M, Beilstein P, Grossenbacker H, Hutter R. Ring cleavage and degradative pathway of cyanuric acid in bacteria. Biochem J. 1985;231:25–30. doi: 10.1042/bj2310025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulter C J, Hamilton T G, McRoberts W C, Kulakov L, Larkin M J, Harper D B. Halomethane:bisulfide/halide ion methyltransferase, an unusual corrinoid enzyme of environmental significance isolated from an aerobic methylotroph using chloromethane as the sole carbon source. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4301–4312. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4301-4312.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crain A D, Guillette L J, Rooney A A, Pickford D B. Alterations in steroidogenesis in alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) exposed naturally and experimentally to environmental contaminants. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105:528–533. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawford J J, Sims G K, Mulvaney R L, Radosevich M. Biodegradation of atrazine under denitrifying conditions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;49:618–623. doi: 10.1007/s002530051223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuppels D A, Ainsworth T. Molecular and physiological characterization of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato and Pseudomonas syringae pv. maculicola strains that produce the phytotoxin coronatine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3530–3536. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3530-3536.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Bruijn F J. Use of repetitive (repetitive extragenic palindromic and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus) sequences and the polymerase chain reaction to fingerprint the genomes of Rhizobium meliloti isolates and other soil bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2180–2187. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.7.2180-2187.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Souza M L, Sadowsky M J, Wackett L P. Atrazine chlorohydrolase from Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP: gene sequence, enzyme purification, and protein characterization. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4894–4900. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4894-4900.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Souza M L, Newcombe D, Alvey S, Crowley D E, Hay A, Sadowsky A M J, Wackett L P. Molecular basis of a bacterial consortium: interspecies catabolism of atrazine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:178–184. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.178-184.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Souza M L, Seffernick J, Martinez B, Sadowski M, Wackett L P. The atrazine catabolism genes atzABC are widespread and highly conserved. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1951–1954. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1951-1954.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Souza M L, Wackett L P, Sadowsky M J. The atzABC genes encoding atrazine catabolism are located on a self-transmissible plasmid in Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2323–2326. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.6.2323-2326.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.di Gioia D, Peel M, Fava F, Wyndham R C. Structures of homologous composite transposons carrying cbaABC genes from Europe and North America. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1940–1946. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1940-1946.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donnelly P K, Entry J A, Crawford D L. Degradation of atrazine and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid by mycorrhizal fungi at three nitrogen concentrations in vitro. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2642–2647. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2642-2647.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunbar J, White S, Forney L. Genetic diversity through the looking glass: effect of enrichment bias. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1326–1331. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1326-1331.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eaton R W, Karns J S. Cloning and analysis of the s-triazine catabolic genes from Pseudomonas sp. strain NRRLB-12227. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1215–1222. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1215-1222.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erickson E L, Lee K H. Degradation of atrazine and related s-triazines. Crit Rev Environ Contam. 1989;19:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esser H O, Dupuis G, Ebert E, Marco G J, Vogel C. S-Triazines. In: Kearney P C, Kaufman D D, editors. Herbicides. Chemistry, degradation and mode of action. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1975. pp. 129–208. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Funari E, Barbieri L, Bottoni P, Del-Carlo G, Forti S, Giuliano G, Marinelli A, Santini C, Zavatti A. Comparison of the leaching properties of alachlor, metolachlor, triazines and some of their metabolites in an experimental field. Chemosphere. 1998;36:1759–1773. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gan J, Becker R L, Koskinen W C, Buhler D D. Degradation of atrazine in two soils as a function of concentration. J Environ Qual. 1996;25:1064–1072. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Wood W A, Krieg N R. Methods for general and molecular microbiology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodrich J A, Lykins B W, Clark R M. Drinking water from agriculturally contaminated ground water. J Environ Qual. 1991;20:707–717. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Houot S, Chaussod R. Impact of agricultural practices on the size and activity of the microbial biomass in a long-term field experiment. Biol Fertil Soil. 1995;19:309–316. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hulton C S J, Higgins C F, Sharp P M. ERIC sequences: a novel family of repetitive elements in the genomes of Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium and other enteric bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:825–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarvis B D W, Van-Berkum P, Chen W X, Nour S M, Fernandez M P, Cleyet-Marel J C, Gillis M. Transfer of Rhizobium loti, Rhizobium huakuii, Rhizobium ciceri, Rhizobium mediterraneum, and Rhizobium tianshanense to Mesorhizobium gen. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:895–898. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Junker F, Cook A M. Conjugative plasmids and the degradation of arylsulfonates in Comomonas testosteroni. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2403–2410. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2403-2410.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kado C I, Liu S T. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1365-1373.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kampfer P, Muller C, Mau M, Neef A, Auling G, Busse H J, Osborn A M, Stolz A. Description of Pseudaminobacter gen. nov. with two new species, Pseudaminobacter salicylatoxidans sp. nov. and Pseudaminobacter defluvii sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:887–897. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karns J S, Eaton R W. Genes encoding s-triazine degradation are plasmid-borne in Klebsiella pneumoniae strain 99. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45:1017–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaufman D D, Blake J. Degradation of atrazine by soil fungi. Soil Biol Biochem. 1970;2:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis, version 1.0. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lane D J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1991. pp. 114–143. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lapage S P, Shelton J E, Mitchell T G. Media for the maintenance and preservation of bacteria. Methods Microbiol. 1970;3A:1–134. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu C-M, McLean P A, Sookdeo C C, Cannon F C. Degradation of the herbicide glyphosate by members of the family Rhizobiaceae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1799–1804. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.6.1799-1804.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lynch M J, Wopat A E, O'Connor M L. Characterization of two new facultative methanotrophs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;40:400–407. doi: 10.1128/aem.40.2.400-407.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mandelbaum R T, Allan D L, Wackett L P. Isolation and characterization of a Pseudomonas sp. that mineralizes the s-triazine herbicide atrazine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1451–1457. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1451-1457.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mirgain I, Green G A, Monteil H. Degradation of atrazine in laboratory microcosms—isolation and identification of the biodegrading bacteria. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1993;12:1627–1634. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore A, Waring C P. Mechanistic effects of a triazine pesticide on reproductive endocrine function in mature male Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Parr. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1998;62:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mougin C, Laugero C, Asther M, Chaplain V. Biotransformation of s-triazine herbicides and related degradation products in liquid cultures by the white rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Pestic Sci. 1997;49:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muller S R, Berg M, Ulrich M M, Schwarzenbach R P. Atrazine and its primary metabolites in Swiss lakes: input characteristics and long-term behavior in the water column. Environ Sci Technol. 1997;31:2104–2113. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagy I, Compernolle R, Ghys K, Vanderleyden J, Demot R. A single cytochrome P-450 system is involved in degradation of the herbicides EPTC (S-ethyl dipropylthiocarbamate) and atrazine by Rhodococcus sp. strain NI86/21. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2056–2060. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.2056-2060.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nour S M, Fernandez M P, Normand P, Cleyet-Mael J C. Rhizobium ciceri sp. nov., consisting of strains that nodulate chickpeas (Cicer arietinum L.) Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:511–522. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-3-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ostrofsky E B, Traina S J, Tuovinen O H. Variation in atrazine mineralization rates in relation to agricultural management practice. J Environ Qual. 1997;26:647–657. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pooler M R, Ritchie D F, Hartung J S. Genetic relationships among strains of Xanthomonas fragariae based on random amplified polymorphic DNA PCR, repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR, and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR data and generation of multiplexed PCR primers useful for the identification of this phytopathogen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3121–3127. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3121-3127.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prévost D, Bordeleau L M, Caudry-Reznick S, Schulman H M, Antoun H. Characteristics of rhizobia isolated from three legumes indigenous to the Canadian high arctic: Astragalus alpinus, Oxytropis maydelliana, and Oxytropis arctobia. Plant Soil. 1987;98:313–324. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pussemier L, Goux S, Vanderheyden V, Debongnie P, Tresinie I, Foucart G. Rapid dissipation of atrazine in soils taken from various maize fields. Weed Res. 1997;37:171–179. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Radosevich M, Traina S J, Hao Y L, Tuovinen O H. Degradation and mineralization of atrazine by a soil bacterial isolate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:297–302. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.297-302.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sadowsky M J, Tong Z, de Souza M, Wackett L P. atzC is a new member of the amidohydrolase protein superfamily and is homologous to other atrazine-metabolizing enzymes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:152–158. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.152-158.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Solomon K R, Baker D B, Richards R P, Dixon K R, Klaine S J, La Point T W, Kendall R J, Weisskopf C P, Giddings J M, Giesy J P, et al. Ecological risk assessment of atrazine in North American surface waters. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1996;15:31–76. doi: 10.1002/etc.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Struthers J K, Jayachandran K, Moorman T B. Biodegradation of atrazine by Agrobacterium radiobacter J14a and use of this strain in bioremediation of contaminated soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3368–3375. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3368-3375.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thurman E M, Goolsby D A, Meyer M T, Mills M S, Pomes M I, Kolpin D W. A reconnaissance study of herbicides and their metabolites in surface water on the midwestern United States using immunoassay and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Environ Sci Technol. 1992;26:2440–2447. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomlin C. The pesticide manual. 10th ed. Farnham, United Kingdom: British Crop Protection Council; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Topp E, Gutzman D W, Bourgoin B, Millette J, Gamble D S. Rapid mineralization of the herbicide atrazine in alluvial sediments and enrichment cultures. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1995;14:743–747. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Topp E, Hanson R S, Ringerberg D B, White D C, Wheatcroft R. Isolation and characterization of an N-methylcarbamate insecticide-degrading methylotrophic bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3339–3349. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3339-3349.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Topp E, Tessier L, Gregorich E G. Dairy manure incorporation stimulates rapid atrazine mineralization in an agricultural soil. Can J Soil Sci. 1996;76:403–409. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Urakami T, Araki H, Oyanagi H, Suzuki K I, Komagata K. Transfer of Pseudomonas aminovorans (den Dooren de Jong 1926) to Aminobacter gen. nov. as Aminobacter aminovorans comb. nov. and description of Aminobacter aganoensis sp. nov. and Aminobacter niigataensis sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:84–92. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vanderheyden V, Debongnie P, Puissemier L. Accelerated degradation and mineralization of atrazine in surface and subsurface soil materials. Pestic Sci. 1997;49:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Versalovic J, Schneider M, de Bruijn F J, Lupski J R. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction. Methods Mol Cell Biol. 1994;5:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Widmer S K, Spalding R F. A natural gradient transport study of selected herbicides. J Environ Qual. 1995;24:445–453. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wyndham R C, Singh R K, Straus N A. Catabolic instability, plasmid gene deletion and recombination in Alcaligenes sp. BR 60. Arch Microbiol. 1988;150:237–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00407786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yanze-Kontchou C, Gschwind N. Mineralization of the herbicide atrazine as a carbon source by a Pseudomonas strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4297–4302. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4297-4302.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]