Abstract

We postulated that vascular dysfunction mediates the relationship between amyloid load and white matter hyperintensities (WMH) in cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Thirty-eight cognitively healthy patients with CAA (mean age 70 ± 7.1) were evaluated. WMH was quantified and expressed as percent of total intracranial volume (pWMH) using structural MRI. Mean global cortical Distribution Volume Ratio representing Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) uptake (PiB-DVR) was calculated from PET scans. Time-to-peak [TTP] of blood oxygen level-dependent response to visual stimulation was used as an fMRI measure of vascular dysfunction. Higher PiB-DVR correlated with prolonged TTP (r = 0.373, p = 0.021) and higher pWMH (r = 0.337, p = 0.039). Prolonged TTP also correlated with higher pWMH (r = 0.485, p = 0.002). In a multivariate linear regression model, TTP remained independently associated with pWMH (p = 0.006) while PiB-DVR did not (p = 0.225). In a bootstrapping model, TTP had a significant indirect effect (ab = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.137–2.461), supporting that the association between PiB-DVR and pWMH is mediated by TTP response. There was no longer a direct effect independent of the hypothesized pathway. Our study suggests that the effect of vascular amyloid load on white matter disease is mediated by vascular dysfunction in CAA. Amyloid lowering strategies might prevent pathophysiological processes leading to vascular dysfunction, therefore limiting ischemic brain injury.

Keywords: Amyloid angiopathy, white matter disease, molecular imaging, positron emission tomography, cerebrovascular disease, cerebral autoregulation

Introduction

Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA) is a small vessel disease of older adults pathologically characterized by the deposition of β-amyloid protein in the walls of leptomeningeal and cortical vessels. 1 CAA-related vascular amyloid can be demonstrated in vivo with Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans using amyloid binding ligands such as Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) and Florbetapir.2–4

Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy is mainly known as a major cause of strictly lobar/cortical hemorrhagic lesions [lobar intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), lobar cerebral microbleeds (CMB) and cortical superficial siderosis (cSS)], but it is also associated with ischemic brain injury in the form of white matter hyperintensities (WMH), cortical cerebral microinfarcts (CMI) and lobar lacunes.5–10 The exact mechanism underlying widespread ischemic brain damage in CAA is still uncertain but the accumulation of β-amyloid in the vessel wall might cause impairment in vascular reactivity thereby inducing hypoperfusion and ischemia.7,11 Multiple lines of evidence suggest that CAA causes impaired vascular reactivity to physiologic stimuli and this impairment strongly correlates with WMH burden supporting the notion that impaired vascular dysfunction may at least partly mediate CAA-related global ischemic injury.12–15 A previous PiB-PET/MRI study also demonstrated significant correlation between amyloid and WMH burden in patients with CAA but not in those with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) or healthy elderly participants favoring the direct contribution of vascular but not parenchymal amyloid to WMH. 16 The relationship between amyloid burden and vascular dysfunction has not been studied before and the mechanisms of CAA-related white matter damage are not known.

In this current work, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between vascular amyloid burden, vascular dysfunction and WMH in a cognitively healthy CAA cohort who underwent both PiB-PET and visual task-based fMRI along with high-resolution structural MRI. Based on previous knowledge of CAA-related global ischemic injury, we hypothesized that vascular amyloid deposition would be associated with vascular dysfunction and that vascular dysfunction would mediate the effects of amyloid on WMH in patients with CAA.

Materials and methods

Study participants

Data were obtained from an ongoing single-center prospective longitudinal study of CAA patients without cognitive impairment. Patients who presented with ischemic stroke, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, any other neurodegenerative condition, or non-correctable visual impairment were not included into the study. All participants met criteria for probable CAA according to the Boston criteria. 6 The CAA patients presented either with symptomatic ICH or with transient focal neurological symptoms and/or gait problems and found to have lobar CMBs only. None of the CMB-only patients had ischemic cerebrovascular disease, any neurodegenerative condition or other brain disease outside of CAA that can have clinical implications.

Demographics, vascular risk factors, and clinical data of the participants were collected, as previously described. 16 All patients underwent a high-resolution structural MRI at 1.5 T, PiB-PET imaging and visual task-based fMRI, as described in the sections below.

Image acquisition and analysis

Patients underwent a 1.5 T research MRI (Siemens Healthcare, Magnetom Avanto) in a 12-channel head coil. The MRI protocol included a 3D T1-weighted multi-echo Magnetization-Prepared Rapid Gradient-Echo Sequence (MPRAGE) (slice thickness, 1 mm; repetition time, 2730 ms; voxel size 1 × 1 × 1 mm3), a 3D fluid- attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) scan (slice thickness, 1 mm; repetition time, 6000 ms; echo time, 302 ms; voxel size, 1 × 1 × 1 mm3) and a high-resolution susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) scan (repetition time 48 ms; echo time 40 ms; voxel size 0.8 × 0.7 × 1.3 mm3).

The presence of ICH and cSS were reviewed and lobar CMBs were identified and counted on SWI images, as described previously.17,18 Accordingly, ICH was defined as any hemorrhagic parenchymal lesion larger than 10 mm in diameter that was hypointense on SWI sequences. CMBs were defined as round or ovoid lesions that were at least half surrounded by brain parenchyma, hypointense on SWI sequences while isointense on T1 or T2 sequences. cSS was defined as a linear hypointensity over the cortex that follows the curvilinear shape of the surrounding cerebral gyri on SWI sequences. Lacunes were defined based on the STRIVE criteria as round or ovoid, fluid-filled (T2-hyperintense, T1 hypointense and FLAIR hypointense with a surrounding rim of hyperintensity) lesions with a diameter between 3 mm and 15 mm. 19 Cortical CMIs were manually assessed by using MeVisLab (version 2.17, MeVis Medical Solutions AG, Bremen, Germany) based on previously published criteria. 8 Accordingly, cortical CMIs were defined as lesions hypointense on T1, hyperintense or isointense on FLAIR and isointense on SWI images, ≤3 mm in diameter, restricted to the cortex, perpendicular to the cortical surface and distinct from perivascular spaces and ICH. WMH volume was calculated using a semiautomated algorithm that produced maps of WMH. Briefly, hyperintense white matter regions on FLAIR sequences were segmented using MRIcro software. A first layer of regions of interest (ROIs) corresponding to WMH was created by a semiautomated technique based on intensity thresholding using individually determined intensity thresholds. A second layer of ROIs was then manually outlined on each slice by gross contouring of all WMHs. The intersection of the first and second layers of ROIs was then manually inspected and corrected to serve as a WMH map for volume calculation by MRIcro.16,20 All the maps generated by this algorithm were visually checked to verify their accuracy and manually corrected when needed. In patients with ICH, WMH volume was measured only in non-ICH hemisphere and then multiplied by two. Total intracranial volume (TIV) was calculated as part of the automated surface-based reconstruction in Freesurfer (https://www.surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu), which exploits the relationship between intracranial volume and the linear transform to the standardized MNI305 brain. 21 WMH volume was then expressed as a percentage of TIV (pWMH) to correct for variability in head sizes.

All PiB-PET scans were obtained using a Siemens/CTI (Knoxvile, TN) ECAT HR1 or a GE (Milwaukee, WI) PC4096 scanner at the same center and all procedural steps were described extensively elsewhere. 16 Briefly, 11 C PiB was injected as a bolus (8.5–15 mCi) followed immediately by a 60-minute acquisition. 11 C PiB specific binding was expressed as the distribution volume ratio (DVR) with cerebellar cortex as reference region. Mean PiB-DVR representing global cortical PiB uptake was calculated using a predefined region of interest that included the full thickness of the cortex and immediate subcortical white matter in supratentorial regions, as previously described. 16 In patients with ICH, results from the non-ICH hemisphere were used for the analyses.

A visual task-based fMRI was performed during the research scans at 1.5 T. The fMRI acquisition consisted of a T2*-weighted gradient echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence at 2.5 × 2.5 × 3 mm resolution (TR = 2000 ms, TE = 30 ms, field of view (FOV) = 96 × 96 mm, flip angle = 78). Each functional run acquired 32 partial-brain volumes with 17 oblique-coronal slices oriented over the calcarine sulcus (primary visual cortex, V1). Visual stimuli were projected onto a screen placed in the MRI bore and observed through an angled mirror attached to the head coil. Subjects were given a visual fixation task to indicate via button-press every time a dot at the center of the screen alternated between light and dark red. The visual stimuli consisted of four blocks of an 8-Hz flashing radial black-and-white checkerboard pattern for 20 seconds, followed by 28 seconds of gray screen. Functional runs were repeated four times for analysis.

Visual fMRI data were preprocessed using tools from the FsFAST pipeline (FreeSurfer Functional Analysis Stream Toolbox, http://surfer.nmr.mgh.havard.edu/fswiki/FsFast). Preprocessing included skull-stripping, motion correction, slice-timing correction (interleaved), intensity normalization, and B0 distortion correction using field-maps acquired during the scan. No smoothing was performed to limit partial volume effects between hemorrhagic and healthy tissues. Preprocessed images were analyzed using a general linear model (GLM) with an event-related design for stimulation and baseline regressors. The GLM included a high-pass filter cutoff frequency of 0.01 Hz and the blood-oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal was initialized with the SPM canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF) and its derivative. The Pearson’s r correlation scores were transformed into Fisher Z-scores and mapped to volumetric masks of activation. Regions with ICH were excluded from the fMRI analyses and only voxels in the activation masks that exceeded a stringent significance threshold of p < 0.000001 (false discovery rate corrected) were included in further analyses to exclude potential contribution from hemorrhagic lesions, an approach established in previous studies13,14. Elimination of non-responding voxels (p > 0.000001) allowed us to alleviate any effect that ICH could introduce into fMRI analyses. The significant BOLD time series were averaged across voxels, blocks and then runs to generate a mean HRF for each subject. Visual response parameters were extrapolated by fitting the mean HRFs with trapezoidal functions using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm in Python (scipy_optimize.curve_fit, https://www.python.org). The time to peak (TTP) was defined as the time from the beginning of the mean HRF (t = 0s) to the onset of the model-determined peak. 13 The TTP response represents only viable tissue as this method prevents potential disturbance of BOLD response due to the presence of a lesion in the area.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

This study was performed with the approval of and in accordance with the guidelines of the institutional review board of Massachusetts General Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent.

Data availability

Any data directly relevant to this particular study not published in the article are available by request from a qualified investigator.

Statistical analysis

Discrete variables were presented as count (%) and continuous variables as mean (±standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]), as appropriate based on their distribution. Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test, continuous variables using the independent-samples t test (for normal distributions) and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for non-normal distributions). Bivariate correlations were assessed using Pearson or Spearman correlation tests, as appropriate. To test the mediation hypothesis, a traditional Baron and Kenny method as well as a bootstrapping procedure were used. In mediation analysis, PiB-DVR was considered as predictor/independent variable, TTP response as the mediator and pWMH as outcome/dependent variable. For the mediation analyses using the Baron and Kenny method 22 , separate linear regression models were used to test the associations between PiB-DVR and TTP, PiB-DVR and pWMH and TTP and pWMH, all adjusted for age, sex and presence of ICH. A final linear regression model was built with pWMH as the outcome variable and both PiB-DVR and TTP as predictors along with age, sex, and presence of ICH.

The bootstrapping procedure was performed using the PROCESS macro version 3.5 for SPSS which uses a regression-based approach to mediation and estimates path coefficients. 23 This method makes no assumptions about normality in the sampling distribution and offers better control of type I error compared to other methods of mediation analysis.24,25 Confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using 10,000 replications and indirect effects were considered significant when the 95% bootstrapped CI did not contain zero. An alternative mediation model (PiB-DVR as predictor, pWMH volume as the mediator and TTP response as outcome variable) was also tested to exclude the presence of a spurious path effect in the hypothesized pathway.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 38 patients with a mean age of 70 ± 7.1 and 86.8% were male. Hypertension was present in 24 (63.2%) patients. Imaging characteristics of the study cohort are presented in Table 1. Twenty-five (65.8%) patients had ICH, while the remaining 13 (34.2%) patients had multiple strictly lobar CMBs only. All lacunes were located in lobar regions. CAA patients with versus without ICH did not differ in age, sex, presence of hypertension, PiB-DVR, TTP or pWMH (all p > 0.2). pWMH was not associated with either presence of lacunes (p = 0.300) or cortical CMI (p = 0.959).

Table 1.

Imaging markers of CAA disease severity in all cohort.

| Imaging markers | Patients with CAA (n = 38) |

|---|---|

| Presence of ICH, n (%) | 25 (65.8) |

| Lobar CMB counts, median (IQR) | 31.5 (8-88) |

| Presence of cSS, n (%) | 20 (52.6) |

| pWMH, mean ± SD | 1.93 ± 1.43 |

| Presence of lacunes, n (%) | 12 (31.6) |

| Presence of cortical cerebral microinfarcts, n (%) | 9 (26.3) |

| PiB- DVR, mean ± SD | 1.29 ± 0.23 |

| TTP of BOLD response, mean ± SD | 9.87 ± 2.30 |

ICH: intracerebral hemorrhage; n: number; IQR: interquartile range; CMB: cerebral microbleed; cSS: cortical superficial siderosis; pWMH: white matter hyperintensity volume percentage of estimated intracranial volume; PiB-DVR: distribution volume ratio of Pittsburg Compound B; TTP: time to peak; BOLD: blood oxygen level-dependent; SD: standard deviation.

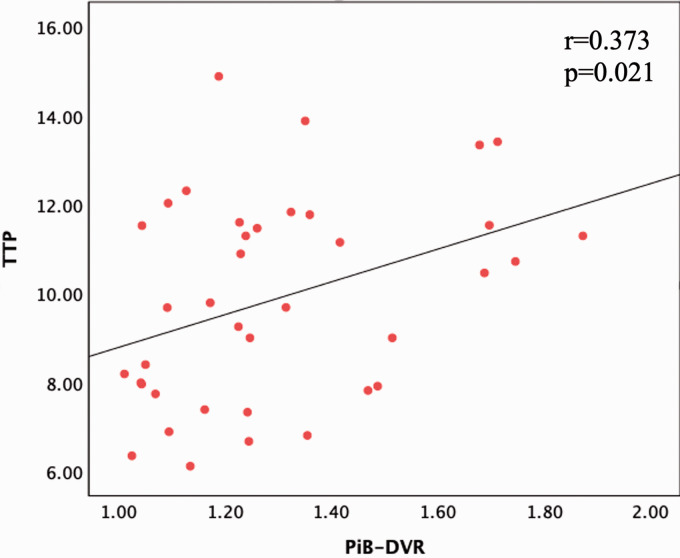

The associations of PiB-DVR and TTP response with demographics and imaging markers of CAA are presented in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Higher pWMH significantly correlated with increased PiB-DVR as well as with prolonged TTP response. Furthermore, higher PiB-DVR correlated with prolonged TTP (r = 0.373, p = 0.021, Figure 1). These correlations did not change in separate regression models corrected for age, sex, and presence of ICH (Table 4). In the regression model including both PiB-DVR and TTP as covariates, PiB-DVR no longer associated with pWMH (p = 0.225) while TTP remained as an independent predictor (p = 0.006), consistent with a mediating role for vascular reactivity in the relationship between PiB-DVR and pWMH (Table 4).

Table 2.

Association of PiB DVR with demographics and imaging markers in CAA.

| Binary variables | PiB DVR, mean ± SD | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male (n = 33) | 1.31 ± 0.23 | 0.167 | |

| Female (n = 5) | 1.16 ± 0.13 | ||

| Hypertension | |||

| Yes (n = 24) | 1.30 ± 0.23 | 0.673 | |

| No(n = 14) | 1.27 ± 0.23 | ||

| Presence of ICH | |||

| Yes (n = 25) | 1.30 ± 0.23 | 0.816 | |

| No(n = 13) | 1.28 ± 0.23 | ||

| Presence of cSS | 0.710 | ||

| Yes (n = 20) | 1.31 ± 0.22 | ||

| No(n = 18) | 1.28 ± 0.24 | ||

| Presence of lacunes | 0.643 | ||

| Yes (n = 12) | 1.27 ± 0.25 | ||

| No(n = 26) | 1.30 ± 0.22 | ||

| Presence of cortical CMIs | |||

| Yes (n = 9) | 1.40 ± 0.31 | 0.107 | |

| No(n = 29) | 1.26 ± 0.19 | ||

|

Correlation of PiB-DVR with continuous variables |

r/rho |

p |

|

| Age | 0.084 | 0.617 | |

| pWMH | 0.337 | 0.039 | |

| Lobar CMB counts | 0.196 | 0.239 | |

ICH: intracerebral hemorrhage; n: number; CMB: cerebral microbleed; CMI: cerebral microinfarcts; cSS: cortical superficial siderosis; pWMH: white matter hyperintensity volume percentage of estimated intracranial volume; PiB: Pittsburgh Compound B; DVR: distribution volume ratio; SD: standard deviation.

Table 3.

Association of time-to-peak with demographics and imaging markers in CAA.

| Binary variables | TTP, mean ± SD | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male (n = 33) | 9.94 ± 2.32 | 0.636 | |

| Female (n = 5) | 9.41 ± 2.40 | ||

| Hypertension | |||

| Yes (n = 24) | 9.95 ± 2.34 | 0.650 | |

| No(n = 14) | 9.74 ± 2.31 | ||

| Presence of ICH | |||

| Yes (n = 25) | 9.80 ± 2.31 | 0.791 | |

| No(n = 13) | 10.0 ± 2.37 | ||

| Presence of cSS | 0.474 | ||

| Yes (n = 20) | 10.1 ± 2.17 | ||

| No(n = 18) | 9.58 ± 2.48 | ||

| Presence of lacunes | 0.742 | ||

| Yes (n = 12) | 9.69 ± 2.28 | ||

| No(n = 26) | 9.96 ± 2.36 | ||

| Presence of cortical CMIs | |||

| Yes (n = 9) | 10.8 ± 2.92 | 0.130 | |

| No(n = 29) | 9.55 ± 2.03 | ||

|

Correlation of TTP with continuous variables |

r/rho |

p |

|

| Age | 0.084 | 0.617 | |

| pWMH | 0.485 | 0.002 | |

| Lobar CMB counts | 0.333 | 0.041 | |

ICH: intracerebral hemorrhage; n: number; CMB: cerebral microbleed; CMI: Cerebral microinfarct; cSS: cortical superficial siderosis; pWMH: white matter hyperintensity volume percentage of estimated intracranial volume; TTP: time to peak; SD: standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot showing the linear association between PiB-DVR and the TTP of blood oxygen level dependent response in cerebral amyloid angiopathy: High DVR indicates high global cortical amyloid load. PiB: Pittsburgh Compound B; DVR: Distribution volume ratio; TTP: Time-to-peak.

Table 4.

Linear regression models demonstrating mediation with the Baron and Kenny method.

| Predictor(s) of Interest | Dependent variable | Covariates | β (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I | PiB-DVR | TTP | Age, sex, ICH | 3.4 (0.1–6.7) | 0.044 |

| Model II | TTP | pWMH | Age, sex, ICH | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 0.001 |

| Model III | PiB-DVR | pWMH | Age, sex, ICH | 2.1 (0.1–4.2) | 0.039 |

| Model IV | PiB-DVRTTP | pWMH | Age, sex, ICH | 1.1 ([−0.7]−3.1) 0.28 (0.1–0.5) | 0.2250.006 |

pWMH: white matter hyperintensity volume percentage of estimated intracranial volume; TTP: time to peak; PiB: Pittsburgh Compound B; DVR: distribution volume ratio; CI: confidence interval.

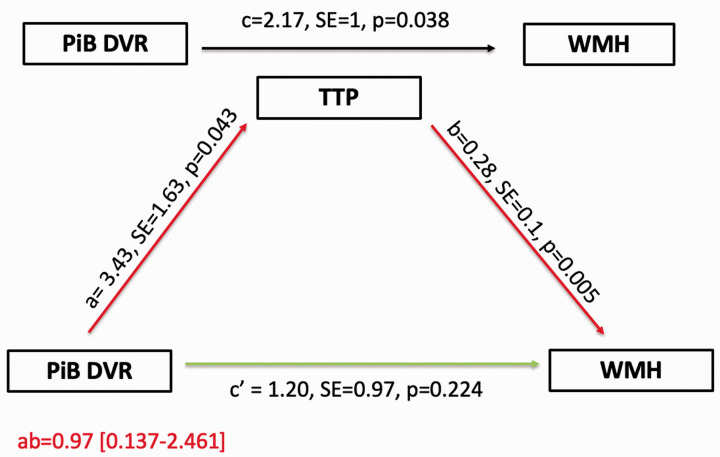

Mediation analysis using the bootstrapping method found that PiB-DVR is indirectly related to pWMH through its relationship with the TTP response, corrected for age, sex, and presence of ICH. The mediation model and path coefficients are shown in Figure 2. In this model, increased PiB-DVR was associated with prolonged TTP (a = 3.43, p = 0.043), and prolonged TTP was subsequently related to higher pWMH (b = 0.28, p = 0.005). A 95% CI based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples of the indirect effect was entirely above zero (0.137–2.461), indicating significance for the hypothesized mediation pathway. There was no direct effect of PiB-DVR on pWMH independent of the hypothesized pathway (c′=1.20, p = 0.224). The alternative mediation model in which pWMH is the mediator between amyloid load and TTP response was insignificant (indirect effect = 1.35 [(−0.015)–(3.097)] indicating that the mediation effect is specific to the originally hypothesized sequential order.

Figure 2.

Summary figure of path model demonstrating the mediating effect of TTP on the relationship between PiB-DVR and WMH. For each connection, the path coefficient (a, b, c and c′), its standard error and significance (p) are shown. a path (red) is the effect of PiB-DVR on TTP; b path (red) is the effect of TTP on WMH; c path (black) is the total effect (direct effect + indirect effect) of PiB-DVR on WMH; c′ path (green) is the direct effect of PiB-DVR on WMH; and ‘ab’ path (a × b, red) is the indirect effect of PiB-DVR on WMH mediated by TTP. Since the 95% CI of ‘ab’ path did not include zero, the mediation effect of the hypothesized pathway was statistically significant. All paths were adjusted for age, sex and presence of intracerebral hemorrhage. SE = standard error; PiB: Pittsburgh Compound B; DVR = Distribution volume ratio; TTP: Time to peak; WMH: White matter hyperintensities.

Discussion

This is the first study that investigated the relationship between vascular amyloid and vascular dysfunction as well as the potential mechanism of ischemic white matter injury in patients with CAA. The main findings of our study are that higher global cortical amyloid deposition is independently associated with an established measure of vascular dysfunction (prolonged TTP); and that the effect of vascular amyloid on WMH is mediated by vascular dysfunction. Our findings might have direct implications on future clinical trials aimed at limiting ischemic brain damage in patients with CAA.

Besides being a well-established cause of hemorrhagic and ischemic brain lesions, CAA is an important contributor to cognitive impairment in elderly.1,5,26 Previous studies indicate that non-demented lobar ICH survivors are at high risk for incident dementia even in the absence of subsequent ICHs.26,27 The risk of dementia has also been found to be high in patients with CAA without lobar ICH. 28 Available evidence suggests that CAA-related global brain damage (WMH, white matter atrophy) and the cumulative effect of smaller lesions on structural networks contribute to the development of cognitive impairment in patients with CAA.29–32 Ischemia is the presumed contributor to the global and many focal lesions associated with CAA pathology. Therefore, a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying ischemic brain injury might help reduce the risk of CAA-related cognitive changes.

Vascular amyloid which is the key protein in CAA pathology can be detected and quantified by amyloid PET imaging. 33 Several PET studies have shown increases in PiB uptake globally with an occipital preference as well as at foci of past and future hemorrhagic lesions in patients with CAA.34,35 Increased PiB uptake was also demonstrated to independently correlate with greater burden of WMH in patients with CAA, but not in healthy controls or patients with AD, findings supporting the view that vascular but not parenchymal amyloid is contributing to WMH. 16 Results from the current study confirm the previously reported associations between increased global PiB uptake and WMH burden in patients with CAA. We also studied the potential mechanisms of this association for the first time.

Vascular dysfunction is a potential mechanism of CAA-related widespread ischemic brain injury. The assessment of vascular reactivity using fMRI based on a visual task is currently the best-established method to quantify vascular reactivity. This method has been validated in several separate CAA cohorts in different countries, one also validating it against functional Transcranial Doppler (TCD).13–15 The study that used fMRI and visual evoked potential (VEP) data along with the transcranial doppler (TCD) demonstrated impaired BOLD response to visual stimulus in patients with CAA as compared to healthy controls while there was no difference in VEP P100 amplitudes between the groups, suggesting that CAA-related structural changes may not significantly influence the propagation of the neuronal signal resulting from a visual stimulus. 14 Nonetheless, without simultaneous measurements of neuronal electrical activity by visual evoked responses, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that decreased neuronal activity contributed to the observed decreased vascular reactivity.

The same method was also used in one early phase clinical trial where the data suggested that it is feasible to use this fMRI technique in a consistent manner even across multiple study timepoints and sites. 36 TCD remains as a relevant method to assess vascular reactivity changes but its operator dependence and the lack of adequate transtemporal windows in about 20% of the population limit its use. 37 Finally, more advanced methods that involve gas challenge, acetazolamide administration and others to map different features of the cerebral arterial responses including reactivity and compliance are being developed and used by our and other research groups. The application of these even more sophisticated methods can provide a more detailed account of physiopathological alterations in brain vessels related to CAA. Several studies demonstrated that CAA is associated with vascular dysfunction measured by fMRI BOLD response to visual stimulation, not only in patients with sporadic CAA diagnosed with Boston criteria but also in presymptomatic stages of hereditary CAA.13–15 In this study, we confirmed previous reports showing an independent association between BOLD response and WMH burden in CAA.13,14

The most plausible hypothetical model of CAA-related ischemic global brain injury depends on the observations that amyloid beta is cleared out via perivascular pathways and reduced perivascular clearance could cause accumulation of amyloid beta in the vessel wall. 38 Based on available data from both experimental animal and human studies that used advanced imaging methods, this amyloid deposition results in loss of vascular smooth muscle cells, vessel narrowing and/or and vascular dysfunction that is then hypothesized to cause ischemia, although the exact pathophysiological mechanisms linking these two remain to be elucidated.7,11 An important part of this hypothesis relies on the presence of an association between vascular amyloid and vascular dysfunction, an issue that has not been tested in humans before, despite availability of preclinical studies supporting such a relationship.39,40 Our study demonstrates an independent association between cortical amyloid load and vascular dysfunction in CAA patients. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the previously shown effects of vascular amyloid on WMH are mediated by vascular dysfunction. We used 2 different mediation analyses and the results were consistent. These results add to our understanding of mechanisms of CAA-related WMH, building on a recent study indicating that the effect of CAA on cortical atrophy was mediated by vascular dysfunction. 20 The causal relationship between amyloid burden and vascular dysfunction has been shown in an animal study that also reported an improvement of vascular reactivity with the administration of an anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody. 41 Although one trial of an amyloid-lowering therapy failed to show improvement in vascular reactivity measured by fMRI in a recent small phase II randomized clinical trial of CAA patients 36 , future trials targeting better amyloid clearance at possibly earlier stages of the disease process remain a high priority. Based on the current results and available evidence, both WMH and cortical atrophy may be appropriate imaging outcome markers of studies aimed at proving the potential benefits of interventions that can improve vascular reactivity. The fMRI-based measure of vascular reactivity, TTP of BOLD response itself can be used as a direct imaging proxy for efficacy of interventions aimed at improving vascular response such as amyloid lowering.

Our study did not show any association between the presence of focal ischemic lesions (lacunes and cortical CMIs) and vascular dysfunction, suggesting a potential difference between the mechanisms of focal and global brain lesions in CAA patients, as previously proposed.33,42 This hypothesis needs to be tested in larger studies that primarily aim to understand mechanisms of focal ischemic lesions in patients with CAA.

Our study has some limitations. First, our sample size was relatively small, but nonetheless yielded strong and independent relationships. Another limitation is the possible confounding effect of Alzheimer’s pathology on PET results due to the inability of PiB-PET to distinguish between vascular and parenchymal amyloid. Although parenchymal amyloid cannot be completely excluded in these subjects without histopathologic evaluation, we excluded patients with cognitive impairment or dementia at study enrollment at least to minimize confounding effects from Alzheimer’s pathology. Previously reported associations of PiB retention with CAA-specific markers such as lobar CMBs suggest that amyloid PET imaging in CAA patients is a reasonably good measure of cerebrovascular amyloid. 34 Our cohort included not only patients with CAA-related ICH but also patients who had lobar CMBs only. This might cause heterogeneity in the study cohort, but we did not find any significant differences in demographics, PiB-DVR, TTP, or pWMH between patients with ICH and those without. We also included presence of ICH as a covariate along with age and sex into all regression and mediation analyses. The current sample size does not allow us to perform separate mediation analyses within groups of CAA patients with and without ICH, but future larger studies should look into these important questions especially in non-ICH CAA patients. Future studies should also use a longitudinal design to test the hypothesis that vascular dysfunction mediates the association between vascular amyloid and white matter disease. Such a study requires a relatively large number of patients and follow up imaging after many years as white matter disease is a relatively slow growing process but this important work is ongoing.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that cortical amyloid load correlates with the degree of worsening in vascular reactivity and that such vascular dysfunction mediates the relationship between amyloid burden and global ischemic white matter damage in patients with CAA. These results suggest that vascular amyloid deposition causes vascular dysfunction thereby inducing global ischemic brain injury in CAA. Amyloid lowering therapies might therefore improve vascular dysfunction and prevent at least part of the resultant chronic ischemic brain injury. Our results also support the view that amyloid load assessed by PET imaging, WMH volume and measures of vascular dysfunction are important imaging markers that can be used in CAA clinical trials.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was made by possible through NIH grants. Dr. Gurol reports funding from NIH (R01NS11452, NS083711). Dr. Greenberg reports funding from NIH (R01NS096730, RO1AG26484).

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Elif Gokcal reports no disclosure.

Mitchell J. Horn reports no disclosure.

J. Alex Becker reports no disclosure.

Alvin S Das reports no disclosure.

Kristin Schwab reports no disclosure.

Alessandro Biffi reports no disclosure.

Natalia Rost reports no disclosure.

Jonathan Rosand reports no disclosure.

Anand Viswanathan reports no disclosure.

Jonathan R. Polimeni reports no disclosure.

Keith A. Johnson reports no disclosure.

Steven M. Greenberg reports funding from NIH (R01NS096730, RO1AG26484).

M. Edip Gurol reports funding from NIH (R01NS11452, NS083711). Dr. Gurol also reports research grants to his hospital from AVID, Pfizer and Boston Scientific, all unrelated to the current research article.

| Elif Gokcal | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | literature search, study design, data collection, imaging data analysis, statistical analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing |

| Mitchell J. Horn | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | literature search, data collection, imaging data analysis, critical review of the manuscript |

| J. Alex Becker | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | imaging data analysis, critical review of the manuscript |

| Alvin S Das | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | data collection, critical review of the manuscript |

| Kristin Schwab | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | data collection, critical review of the manuscript |

| Alessandro Biffi | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | data collection, critical review of the manuscript |

| Natalia Rost | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | data collection, critical review of the manuscript |

| Jonathan Rosand | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | data collection, critical review of the manuscript |

| Anand Viswanathan | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | data collection, critical review of the manuscript |

| Jonathan R. Polimeni | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | imaging data analysis, critical review of the manuscript |

| Keith A. Johnson | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | imaging data analysis, critical review of the manuscript |

| Steven M. Greenberg | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | data collection, data interpretation, manuscript writing |

| M. Edip Gurol | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, US | literature search, study design, data collection, imaging data analysis, statistical analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing |

ORCID iD: Alvin S Das https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2313-977X

References

- 1.Banerjee G, Carare R, Cordonnier C, et al. The increasing impact of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: essential new insights for clinical practice. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017; 88: 982–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurol ME, Becker JA, Fotiadis P, et al. Florbetapir-PET to diagnose cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a prospective study. Neurology 2016; 87: 2043–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ly JV, Donnan GA, Villemagne VL, et al. 11C-PIB binding is increased in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related hemorrhage. Neurology 2010; 74: 487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg SM, Grabowski T, Gurol ME, et al. Detection of isolated cerebrovascular beta-amyloid with pittsburgh compound B. Ann Neurol 2008; 64: 587–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurol ME and Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathies. In: Caplan LR, Biller J, (eds) Uncommon Causes of Stroke. 3rd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018. pp. 534–544.

- 6.Knudsen KA, Rosand J, Karluk D, et al. Clinical diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: validation of the Boston criteria. Neurology 2001; 56: 537–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reijmer YD, van Veluw SJ, Greenberg SM. Ischemic brain injury in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 40–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Veluw SJ, Shih AY, Smith EE, et al. Detection, risk factors, and functional consequences of cerebral microinfarcts. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 730–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasi M, Boulouis G, Fotiadis P, et al. Distribution of lacunes in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive small vessel disease. Neurology 2017; 88: 2162–2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai HH, Pasi M, Tsai LK, et al. Distribution of lacunar infarcts in Asians with intracerebral hemorrhage: a magnetic resonance imaging and amyloid positron emission tomography study. Stroke 2018; 49: 1515–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith EE. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy as a cause of neurodegeneration. J Neurochem 2018; 144: 651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith EE, Vijayappa M, Lima F, et al. Impaired visual evoked flow velocity response in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 2008; 71: 1424–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumas A, Dierksen GA, Gurol ME, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging detection of vascular reactivity in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol 2012; 72: 76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peca S, McCreary CR, Donaldson E, et al. Neurovascular decoupling is associated with severity of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 2013; 81: 1659–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Opstal AM, van Rooden S, van Harten T, et al. Cerebrovascular function in presymptomatic and symptomatic individuals with hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurol ME, Viswanathan A, Gidicsin C, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy burden associated with leukoaraiosis: a positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging study. Ann Neurol 2013; 73: 529–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg SM, Vernooij MW, Cordonnier C, et al. Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 165–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charidimou A, Linn J, Vernooij MW, et al. Cortical superficial siderosis: detection and clinical significance in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and related conditions. Brain 2015; 138: 2126–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 822–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fotiadis P, van Rooden S, van der Grond J, et al. Cortical atrophy in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol 2016; 15: 811–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckner RL, Head D, Parker J, et al. A unified approach for morphometric and functional data analysis in young, old, and demented adults using automated atlas-based head size normalization: reliability and validation against manual measurement of total intracranial volume. Neuroimage 2004; 23: 724–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 51: 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes AF. Statistical methods for communication science. New York, Routledge, 2020.

- 24.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 2004; 36: 717–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 2008; 40: 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moulin S, Labreuche J, Bombois S, et al. Dementia risk after spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2016; 15: 820–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biffi A, Bailey D, Anderson CD, et al. Risk factors associated with early vs delayed dementia after intracerebral hemorrhage. JAMA Neurol 2016; 73: 969–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiong L, Boulouis G, Charidimou A, et al. Dementia incidence and predictors in cerebral amyloid angiopathy patients without intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018; 38: 241–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reijmer YD, Fotiadis P, Martinez-Ramirez S, et al. Structural network alterations and neurological dysfunction in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain 2015; 138: 179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim HJ, Im K, Kwon H, et al. Clinical effect of white matter network disruption related to amyloid and small vessel disease. Neurology 2015; 85: 63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith EE, Gurol ME, Eng JA, et al. White matter lesions, cognition, and recurrent hemorrhage in lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 2004; 63: 1606–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fotiadis P, Reijmer YD, Van Veluw SJ, on behalf of the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study group et al. White matter atrophy in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 2020; 95: e554–e562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurol ME, Biessels GJ, Polimeni JR. Advanced neuroimaging to unravel mechanisms of cerebral small vessel diseases. Stroke 2020; 51: 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dierksen GA, Skehan ME, Khan MA, et al. Spatial relation between microbleeds and amyloid deposits in amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol 2010; 68: 545–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurol ME, Dierksen G, Betensky R, et al. Predicting sites of new hemorrhage with amyloid imaging in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 2012; 79: 320–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leurent C, Goodman JA, Zhang Y, Ponezumab Trial Study Group et al. Immunotherapy with ponezumab for probable cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2019; 6: 795–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Topcuoglu MA. Transcranial doppler ultrasound in neurovascular diseases: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. J Neurochem 2012; 123 Suppl 2: 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenberg SM, Bacskai BJ, Hernandez-Guillamon M, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and alzheimer disease - one peptide, two pathways. Nat Rev Neurol 2020; 16: 30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas T, Thomas G, McLendon C, et al. beta-Amyloid-mediated vasoactivity and vascular endothelial damage. Nature 1996; 380: 168–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niwa K, Younkin L, Ebeling C, et al. Abeta 1-40-related reduction in functional hyperemia in mouse neocortex during somatosensory activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000; 97: 9735–9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bales KR, O'Neill SM, Pozdnyakov N, et al. Passive immunotherapy targeting amyloid-beta reduces cerebral amyloid angiopathy and improves vascular reactivity. Brain 2016; 139: 563–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gokcal E, Horn MJ, van Veluw SJ, et al. Lacunes, microinfarcts, and vascular dysfunction in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 2021; 96: e1646–e1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Any data directly relevant to this particular study not published in the article are available by request from a qualified investigator.