Abstract

Introduction

In India about 95% of individuals who need treatment for common mental disorders like depression, stress and anxiety and substance use are unable to access care. Stigma associated with help seeking and lack of trained mental health professionals are important barriers in accessing mental healthcare. Systematic Medical Appraisal, Referral and Treatment (SMART) Mental Health integrates a community-level stigma reduction campaign and task sharing with the help of a mobile-enabled electronic decision support system (EDSS)—to reduce psychiatric morbidity due to stress, depression and self-harm in high-risk individuals. This paper presents and discusses the protocol for process evaluation of SMART Mental Health.

Methods and analysis

The process evaluation will use mixed quantitative and qualitative methods to evaluate implementation fidelity and identify facilitators of and barriers to implementation of the intervention. Case studies of six intervention and two control clusters will be used. Quantitative data sources will include usage analytics extracted from the mHealth platform for the trial. Qualitative data sources will include focus group discussions and interviews with recruited participants, primary health centre doctors, community health workers (Accredited Social Health Activits) who participated in the project and local community leaders. The design and analysis will be guided by Medical Research Council framework for process evaluations, the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework, and the normalisation process theory.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the ethics committee of the George Institute for Global Health, India and the Institutional Ethics Committee, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi. Findings of the study will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications, stakeholder meetings, digital and social media platforms.

Trial registration number

CTRI/2018/08/015355.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, PRIMARY CARE, Clinical trials, Protocols & guidelines, Suicide & self-harm, Depression & mood disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength of our study is its use of implementation science theories and guidelines for process evaluation to frame the study design.

This study combines data from an open-source medical record system with qualitative methods to understand trends, patterns and differences in outcome.

One limitation could be the overlap between the implementation team and the evaluation team.

Introduction

India has a significant burden of mental disorders with an estimated 115 million people in need of mental healthcare.1 The National Mental Health Survey of India (2015–2016) found substance use, depressive disorders and anxiety disorders to be prevalent in about 10% of the population.1 Despite the significant burden, access to mental health services is severely limited and it is estimated that nearly 95% of individuals with common mental disorders (CMDs) are unable to access care in India2 leading to large treatment gaps. Studies report that in low-income and middle-income countries, the treatment gap for any mental disorder is between 75% and 85%.3 One study found that in low-resource settings such as India, only 1 in every 27 individuals with depression who recognised need for treatment, could access minimally adequate treatment from a trained mental health professional.4

This large treatment gap is due to several factors, on both demand and supply sides. Low awareness about mental health in the community and high level of stigma related to mental illness are key demand side factors for poor help-seeking for CMDs.5 On the supply side, several systemic barriers limit access to mental health services. Among these are the lack of a trained mental health workforce and absent/minimal mental health services at the primary care level, inadequate supply of psychotropic drugs at primary healthcare facilities and limited budget for mental healthcare.6

Our formative research has demonstrated that addressing both supply and demand side factors by conducting a community-based anti-stigma campaign and implementing a technology-enabled mental health services delivery model by primary health workers, has the potential to increase access to mental healthcare for those at risk of CMDs and reduction in depression and anxiety scores.7–10 In this research, task sharing by primary health workers helped facilitate the process, and technology was seen as an enabling factor in streamlining delivery of mental healthcare.10

Based on these findings, we developed Systematic Medical Appraisal, Referral and Treatment (SMART) Mental Health—a hybrid effectiveness-implementation cluster randomised controlled trial (cRCT) that is being implemented in two Indian states. The cRCT protocol is available elsewhere.11 The goal of SMART Mental Health is to reduce psychiatric morbidity due to psychological stress, depression and risk of self-harm (collectively referred to here as CMDs for the project) in individuals identified at high risk of these conditions. The coprimary outcomes are:

(1) The mean difference in Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores at 12 months in people identified at high-risk of CMDs and (2) the difference in mean behaviour scores at 12 months in the total population.

In this paper, we outline the protocol for a process evaluation of the SMART Mental Health. Process evaluations provide important insights into how an intervention is implemented, leading to understanding what strategies either worked or did not work, explaining differences in outcome, and to gain insights into the experience of the target population for whom the intervention was designed. The aims of the process evaluation are to:

Assess implementation fidelity and understand how the intervention was implemented.

Understand perceptions about effectiveness and acceptability of intervention components by different stakeholders.

Identify and explain facilitators of and barriers to implementation of the intervention.

Explain variations in outcomes and unexpected consequences across sites.

Explain any adaptations to the intervention during the study and their possible impact on the outcomes.

Methods and analysis

Theoretical framework

The process evaluation has been integrated into the cRCT design with an early formative study conducted to understand the feasibility of implementing the project components. It draws on multiple theories and frameworks (table 1). The Medical Research Council guidelines for process evaluation will provide an overall conceptual framework.12 According to this framework, the three broad areas of enquiry in a process evaluation are ‘ implementation’ (what is implemented and how); ‘mechanism of impact’—(how intervention produces change) and ‘context’—(how context affects implementation and outcomes). The framework also emphasises the need to spell out the key causal assumptions made in the programme theory.

Table 1.

Theories to be used in the study

| Theory | About theory | Purpose of using the theory |

| Theory guiding overall design and conceptual framework of the process evaluation | ||

| MRC Framework23 | A framework for designing and carrying out process evaluation of complex interventions. Process evaluation should answer questions related to three components: Implementation (what is delivered and how?) Mechanisms of impact (how does the delivered intervention produce change?) and Context (how does context affect implementation and outcomes?) Along with the context and the mechanism of impact, it emphasises the need to spell out the key causal assumptions or the programme theory. | The framework is used to provide the overall conceptual design of the process evaluation. The three components (implementation, mechanism of impact and context) will be the broad areas of inquiry in the process evaluation. |

| Theories that will inform specific domains of inquiry in the study | ||

| RE-AIM13 | A framework which provides five key dimensions on which a behaviour change intervention can be evaluated. These include Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance of an intervention. | The framework will be used to evaluate the ‘Implementation’ component of the programme. |

| Normalisation Process Theory14 | A theory which focuses on how complex interventions become ‘normalised’ or embedded in routine practice. It helps to understand facilitators and barriers in adoption and routinisation of an intervention. Includes four main components: coherence (sense making), cognitive participation (engagement), collective action (work done for intervention to happen), and reflexive monitoring (taking measure of costs and benefits of the intervention). | The model will be used to explain differences in routinisation of mHealth component in the post-trial maintenance phase. |

MRC, Medical Research Council.

We will also use the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework13 to understand and describe the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance of the intervention. The normalisation process theory (NPT)14 will help to understand the factors that influence integration and routinisation (becoming part of routine practice) of novel interventions in specific settings. NPT is grouped into four broad sub-constructs which influence normalisation or routinisation of novel interventions (coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring). RE-AIM and NPT will be used to evaluate how the programme was implemented to understand barriers to and facilitators of its routine use by primary health centre (PHC) doctors, and community health workers commonly known as ASHAs (abbreviation for Accredited Social Health Activists) and community participants.

Broad thematic areas of inquiry will include the context, implementation and mechanism of impact (table 2). Under the theme ‘context’, social, political, cultural and health system level factors impacting on implementation of the intervention will be explored. Differences between the sites, programme adaptations that were a result of change in context (eg, the COVID-19 pandemic), and site-specific barriers and facilitators that impacted the programme implementation and outcome will be enquired into. Under ‘implementation’ the process evaluation will assess the implementation of the two intervention components—anti-stigma campaign and mHealth based service delivery—using the RE-AIM parameters. It will also investigate the experiences of end users of the intervention. Finally, the process evaluation will explore the ‘mechanism of impact’ by critically examining any variations in outcomes or unexpected outcomes.

Table 2.

Conceptual framework for process evaluation

| Broad area of enquiry | Domains of inquiry | Key questions/process measures | Data source |

| Context | Differences in context |

|

Secondary data; Formative research data Interview with project staff |

| Significant changes in context and programme adaptions |

|

Interview with project staff Project documentation on operational challenges |

|

| Barriers and Facilitators |

|

Interview with project staff | |

| Implementation | Implementation fidelity | Was the intervention delivered as it was planned? | Programme records and documents; Observation and rating Interview with project staff |

| Intervention Reach |

|

Project records and documents Backend data Interview with project staff Interview with ASHAs |

|

| Intervention effectiveness |

|

Community satisfaction survey done at the end of drama performance Outcome survey data; Backend data; FGD with community members Interview with community leaders (like elected village heads, influential village elders and religious leaders), |

|

| Intervention acceptability and adoption |

|

Backend data Interview with ASHAs FGD with ASHAs; Interview with doctors Interview with PHC support staff Interview with health officials (ASHA co-ordinator, Chief Medical Officer) Patient interview |

|

| Post-trial maintenance |

|

Backend data Interview with ASHAs Interview with PHC doctors Interview with PHC support staff Interview with project staff |

|

| Health service use | What are the barriers or facilitators that patient from intervention cluster face while accessing care in the PHC? How many high-risk individuals identified in the intervention arm did not seek care? What are factors which can explain this? What are the factors which explain treatment adherence among high-risk patients who sought care? What are the cluster-wise differences in service utilisation, treatment adherence and number of referrals to specialist centres? What are the factors which can explain this? |

Backend data Interview with high-risk individuals Interview with ASHAs Interview with doctor Interview with project staff |

|

| Mechanism of impact | Variation in outcomes | What kind of cluster level variation is overserved in in the outcomes? What works, for whom and in what context? | Outcome data Backend data; Interview with ASHAs Interview with doctor Interview with project staff |

| Unexpected outcomes | What are some unexpected outcomes and what factors can be attributed to them? | Outcome data Backend data; Interview with ASHAs Interview with doctor Interview with project staff |

CMDs, common mental disorders; FGD, focus group discussion; GAD7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; IVRS, interactive voice recording system; KAB, Knowledge Attitude Behaviour; PHC, primary health centre; PHQ9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Study setting

SMART Mental health is being implemented in 133 villages serviced by 44 randomly selected PHC in West Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh (South India) and Palwal and Faridabad districts of Haryana (North India).

Study design

The process evaluation will use a mixed-method multiple case study design with PHC clusters constituting a ‘case’. Up to eight case studies will be included. Each case will be selected purposively based on the principle of maximum variation in terms of health service delivery context, implementation challenges and outcomes.

Intervention description

The intervention comprises two key components; an antistigma campaign, and a technology-enabled mental health service intervention delivered through task sharing. The capacities of community health workers known as ASHAs and PHC doctors will be enhanced, by providing training in identifying and managing stress, depression, or suicide risk using a technology enabled electronic decision support system (EDSS).

In the preintervention phase, ASHAs will be trained to use the EDSS to screen individuals at high risk of stress, depression, self-harm or suicide using digital hand-held tablets. The tablets have two preinstalled, standardised screening and assessment tools—the PHQ915 16 and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)16 17 questionnaire. The screening process classifies whether participants are at high risk of CMDs based on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores. Because a substantial proportion of people at risk of CMDs undergo natural remission over a period of time18 a second screening of all people initially identified at high risk is undertaken by the ASHAs within 6 months of the first screening to identify those who remain at ‘high risk’.

Additionally, a Knowledge Attitude Behaviour19 scale is administered to assess levels of stigma associated with mental disorders in the community, a Barrier to Access to Care Evaluation-Treatment Stigma20 questionnaire to assess stigma perceptions related to help-seeking for mental disorders and the EuroQol 5-Dimension-3 Level scale21 to assess quality of life. Questions related to history of psychiatric morbidity, availability of social network/support, treatment history and costs incurred in treatment (which will be used for economic evaluation) are also asked.

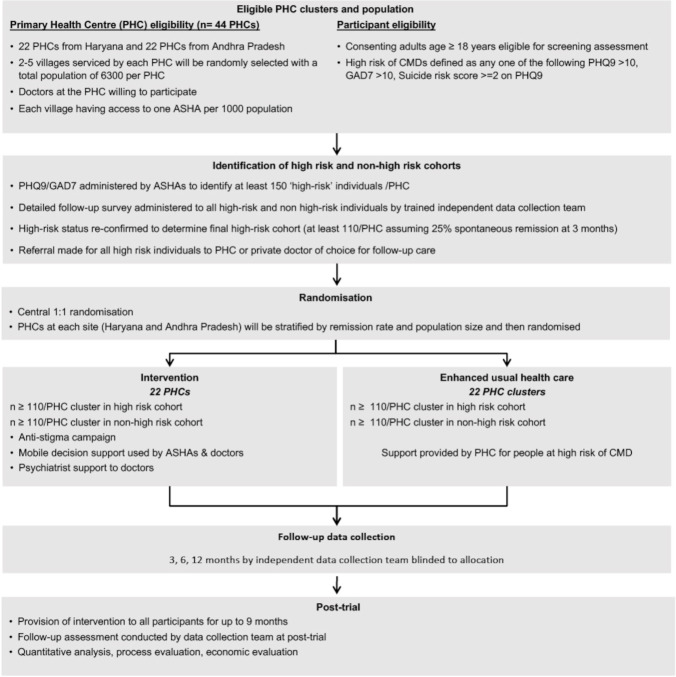

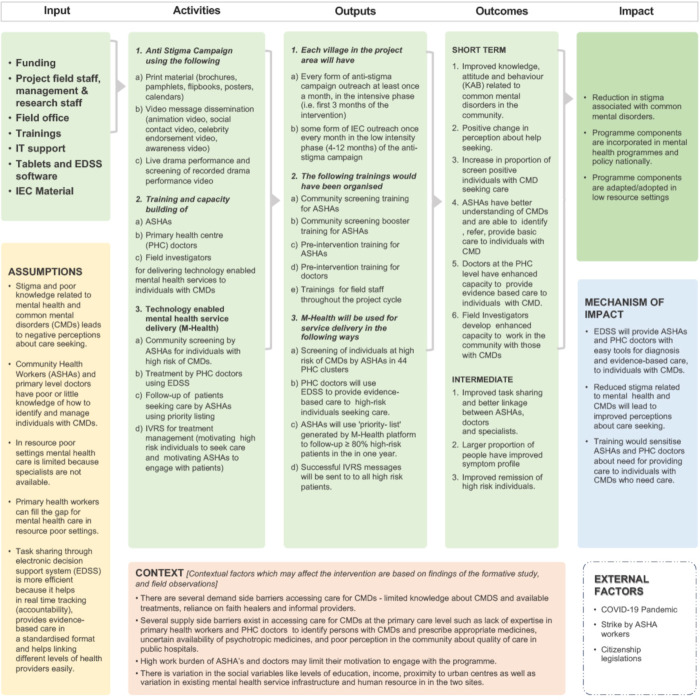

In the intervention phase, the two major intervention components will be implemented to those PHCs randomised to receive SMART Mental Health (figure 1). The logic model for how the intervention strategy is hypothesised to meet its aims has been provided (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Study schema for smart mental health.11 ASHA, Accredited Social Health Activists; CMD, common mental disorder; GAD7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder−7; PHQ9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Figure 2.

Logic model of smart mental health. ASHAs, Accredited Social Health Activists; EDSS, electronic decision support system; IEC, Institutional Ethics Committee; PHCs, primary health centres.

The anti-stigma campaign uses audio-visual and print material tailored to the local community and delivered to both high-risk and non-high-risk individuals, with the aim of reducing negative knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to mental disorders. The second component of the intervention is a technology enabled mental health service delivery model. An mHealth platform will be used for screening, diagnosis, referral and management of CMDs by community level health workers (ASHAs) and PHC doctors. Health workforce capacity building is a crucial input which will be embedded throughout the intervention. The ASHAs will follow-up individuals at high-risk of CMDs to support access to care from the PHC doctors. When the patient reaches the PHC, the doctors will use an EDSS based on WHO’s Mental Health Gap Action Programme Intervention Guide.22 Clinical data will be shared between the ASHAs and doctors using a secure cloud-based server. For follow-up care, the ASHAs will have an algorithm enabled priority listing that will provide them with a traffic-light system to prioritise and track the progress of individuals in her village. They will use this to follow-up patients, paying particular attention to the highest priority individuals and enquiring about their treatment adherence and mental well-being.

Following the intervention, a post-intervention phase up to 9 months will assess the sustainability of the intervention without external influence of the trial team. In this phase, the components of the intervention will be rolled out in the control arm too. Support for ASHAs and doctors by project staff will be minimal. Staff will assist ASHAs and doctors to resolve any technical problems with the tabs and provide initial support and troubleshoot any issues.

Control arm

In the control arm, ASHAs will be provided with the names of individuals at high risk of CMDs and they will support those individuals to seek care and provide them with relevant information of mental healthcare providers. PHC doctors in the control arm will be informed that there may be patients who may seek care for CMDs. The ASHAs and the doctors in the control arm will not be provided with access to the EDSS. The anti-stigma campaign will be delivered in a less extensive manner. Besides pamphlets and brochures, all the other anti-stigma components will be shared with the study participants. The live drama shows however, will not be conducted. Only videos of the drama will be shown. The ASHAs will draw on their existing training and experience on mental health to support individuals as needed.

Data collection

Quantitative data source includes analysis of the usage analytics extracted from the mHealth platform. This includes (1) user metrics from each tablet used by ASHAs and PHC doctors; (2) screening and treatment data about each high-risk individual in the intervention cohort; (3) data from the priority listing application (used by ASHAs) which provide information on treatment status and high-risk individuals who need to be followed up and (4) data from the interactive voice recorded system used to send messages to ASHAs and high-risk individuals (to facilitate treatment adherence and follow-up). These data will be used to assess reach, effectiveness, adoption, maintenance and service utilisation of the intervention.

Qualitative data will include key informant interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) with PHC doctors, ASHAs, hospital administrators, service users and any other relevant stakeholders such as family members of service users and community leaders. The qualitative study data will explore perceptions of key stakeholders about the effectiveness and acceptability of intervention components and challenges in implementation. A detailed data collection plan has been discussed in table 3.

Table 3.

Qualitative data collection plan

| FGDs | |||

| Type of group/Individual | Some areas of inquiry | Number planned per PHC | Total planned (6 intervention and 2 control PHC clusters will be selected for the case study) |

| ASHAs |

|

1 | 8 |

| Project field staff |

|

3 | |

| Study participants from high-risk cohort in intervention arm who sought treatment (To purposively select individuals who (1) went to PHC (2) Went to camp (3) got treated by psychiatrist (4) started treatment but discontinued) |

|

2 (1 with men one with women) |

12 |

| Study participants from non-high-risk cohort in the intervention arm |

|

2 (One with men and one with women) |

12 |

| Study participants from high-risk cohort in the control arm (including both who sought treatment and who did not seek treatment) |

|

2 (One with men and one with women) |

4 |

| Total FGDs | 39 | ||

| In-depth Interviews | |||

| PHC doctors |

|

1 | 8 |

| Village heads/community leaders of the village |

|

1 | 8 |

| Study participants from high-risk cohort in intervention arm who who did not seek treatment |

|

1 | 12 |

| Government health officials |

|

2 (per district) | 6 |

| Total interviews | 24 | ||

ASHAs, Accredited Social Health Activists; CMD, common mental disorder; EDSS, Electronic decision support system; FGDs, focus group discussions; IVRS, interactive voice recording system; PHC, primary health centre.

At the end of the post-intervention phase, a detailed comparative case study of two PHCs with be undertaken. It will include one PHC with high utilisation of EDSS and one with low utilisation. The case study will provide insights into barriers and facilitators in adoption and routinisation of EDSS and explain differences in levels of utilisation of mHealth in different PHC clusters. Interviews with all key stakeholders (including PHC doctors, ASHAs, supervisors associated with the PHC) will be used to develop the case study.

Data analysis

For quantitative data, basic descriptive analyses will be conducted. For qualitative data analysis interview transcripts will be read independently by two persons. A priori codes based on the conceptual framework (table 2) will be used to code the data. Additional thematic findings emerging through the data will be added to the coding framework. Data will be coded using NVivo V.12.0. Both qualitative and quantitative data across case studies will be triangulated to arrive at the findings.

Patient and public involvement

In the formative phase, community feedback was sought through FGDs, to make antistigma content culturally and contextually relevant. The study findings will be shared with the public. Findings will be disseminated through publication in peer reviewed journals, meetings, digital and social media platforms.

Ethics and dissemination

SMART Mental Health cRCT was approved by the George Institute for Global Health, India and the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC), All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi. The trial has been registered (CTRI/2018/08/015355) with the Clinical Trial Registry-India, National Institute of Medical Statistics, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). The project has received requisite approval the Health Ministry’s Screening Committee (HMSC), ICMR.

Trial status

At the time of writing this paper, the intervention phase of the trial had begun in both sites. Clinical Trials Registration was completed on 16 August 2020. Randomisation of clusters in Haryana was done on 21 September 2020 and in Andhra Pradesh on 4 December 2020. Key intervention components were being delivered in Andhra Pradesh and postintervention activities and follow-up surveys were being planned in Haryana.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @drpraveend

Contributors: DPe, PKM and AP conceptualised the SMART Mental Health Trial with a process evaluation in mind. AM developed this process evaluation protocol with extensive and significant inputs from PKM and DPe. PKM and DPe commented on multiple drafts before sending a prefinal version to everyone listed as authors. The manuscript was reviewed and critical comments were provided by MD, SKl, AK, SD, UR, GT, BME, DPr, RS, SK, SS and AP. All authors provided critical intellectual inputs and comments to the draft. PKM leads the implementation of the trial in India along with MD, SD, SKl, AK and AM. All authors contribute to science or operationalising of the project as coinvestigators, or as steering committee members or researchers helping in the implementation of the trial. All authors have critically reviewed, commented and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Global Alliances for Chronic Disease Grant (APP1143911).

Disclaimer: There is no role of the funding body in the design of the study and the conceptualisation and writing of the manuscript. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: The George Institute has a part-owned social enterprise, George Health Enterprises, which has commercial relationships involving digital health innovations. PKM is partially supported through NHMRC/GACD grant (SMART Mental Health-APP1143911) and UKRI/MRC grant MR/S023224/1-Adolescents' Resilience and Treatment nEeds for Mental health in Indian Slums (ARTEMIS). MD, SD, SKl, AK, AM and DPe are partially or wholly supported through the SMART Mental Health NHMRC/GACD grant. DPe is supported by fellowships from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (1143904) and the Heart Foundation of Australia (101890). AK is partially supported by Indigo Partnership (MR/R023697/1) award. GT is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London at King’s College London NHS Foundation Trust, and by the NIHR Asset Global Health Unit award. GT is also supported by the Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity for the On Trac project (EFT151101), and by the UK Medical Research Council (UKRI) in relation to the Emilia (MR/S001255/1) and Indigo Partnership (MR/R023697/1) awards.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V. National health survey of India 2015-16: prevalence, patterns and outcomes. Bangalore, 2016. Available: http://indianmhs.nimhans.ac.in/Docs/Report2.pdf

- 2.Sagar R, Pattanayak RD, Chandrasekaran R, et al. Twelve-month prevalence and treatment gap for common mental disorders: findings from a large-scale epidemiological survey in India. Indian J Psychiatry 2017;59:46–55. 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_333_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, et al. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:858–66. doi:/S0042-96862004001100011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thornicroft G, Chatterji S, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br J Psychiatry 2017;210:119–24. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.188078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sweetland AC, Oquendo MA, Sidat M, et al. Closing the mental health gap in low-income settings by building research capacity: perspectives from Mozambique. Ann Glob Health 2014;80:126–33. 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen I, Marais D, Abdulmalik J. Pneumonia’s second wind? A case study of the global health network for childhood pneumonia. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:699–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maulik PK, Devarapalli S, Kallakuri S, et al. Evaluation of an anti-stigma campaign related to common mental disorders in rural India: a mixed methods approach. Psychol Med 2017;47:565–75. 10.1017/S0033291716002804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maulik PK, Kallakuri S, Devarapalli S, et al. Increasing use of mental health services in remote areas using mobile technology: a pre-post evaluation of the SMART mental health project in rural India. J Glob Health 2017;7:010408. 10.7189/jogh.07.010408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maulik PK, Devarapalli S, Kallakuri S, et al. The systematic medical appraisal referral and treatment mental health project: quasi-experimental study to evaluate a Technology-Enabled mental health services delivery model implemented in rural India. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e15553. 10.2196/15553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tewari A, Kallakuri S, Devarapalli S, et al. SMART mental health project: process evaluation to understand the barriers and facilitators for implementation of multifaceted intervention in rural India. Int J Ment Health Syst 2021;15:15. 10.1186/s13033-021-00438-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniel M, Maulik PK, Kallakuri S, et al. An integrated community and primary healthcare worker intervention to reduce stigma and improve management of common mental disorders in rural India: protocol for the SMART mental health programme. Trials 2021;22:179. 10.1186/s13063-021-05136-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258. 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1322–7. 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, et al. Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med 2010;8:63. 10.1186/1741-7015-8-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfizer.Inc . PHQ and GAD-7 instructions instruction manual Instructions for patient health questionnaire (PHQ) and GAD-7 measures. Available: https://phqscreeners.pfizer.edrupalgardens.com/sites/g/files/g10016261/f/201412/instructions.pdf [Accessed 24 Jul 2020].

- 17.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whiteford HA, Harris MG, McKeon G, et al. Estimating remission from untreated major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2013;43:1569–85. 10.1017/S0033291712001717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lund C, Tomlinson M, De Silva M, et al. PRIME: a programme to reduce the treatment gap for mental disorders in five low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001359. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King’s College London . Barriers to access to care evaluation. London, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.EuroQol Research Foundation . EQ-5D-3L – EQ-5D, 2021. Available: https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-3l-about/ [Accessed 26 Jul 2021].

- 22.WHO . mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non- specialized health settings (version 1.0). Geneva, 2010. Available: www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap [Accessed 11 Jun 2020]. [PubMed]

- 23.Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M. Process evaluation of complex interventions UK medical Research Council (MRC) guidance, 2016. Available: https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/mrc-phsrn-process-evaluation-guidance-final/ [Accessed 2 Aug 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.