Abstract

A 4.3-kg, 11-month-old, spayed female poodle was presented for treatment of a right radio-ulnar nonunion fracture. Clinical history included failed surgical correction of a radius fracture with internal fixation 1 mo before presentation. Radiographic examination revealed a 1.5-cm lytic lesion on the right distal radius. Surgery was planned with a coccyx autograft and platelet-rich plasma. A 2.8-cm-long bone defect was created, and the lytic lesion was removed. Caudectomy was performed; the 6th and 7th coccygeal bones were harvested, placed into the defect, and fixed to the radius with a locking plate. Remnants of coccygeal bone were ground, mixed with platelet-rich plasma, and used to fill the bone defects. There was no evidence of nonunion or delayed union at the 18-month follow-up examination.

Key clinical message:

Based on the study findings, we inferred that a coccyx autograft and platelet-rich plasma can be used for successful reconstruction of a distal radial defect.

Résumé

Utilisation d’une autogreffe de vertèbre coccygienne et de plasma riche en plaquettes pour le traitement d’une fracture radiale distale avec non-union chez un chien de petite race. Une femelle caniche stérilisée de 4,3 kg, âgée de 11 mois, a été présentée pour le traitement d’une fracture radio-ulnaire droite avec non-union. Les antécédents cliniques comprenaient l’échec de la correction chirurgicale d’une fracture du radius avec fixation interne 1 mois avant la présentation. L’examen radiographique a révélé une lésion lytique de 1,5 cm sur le radius distal droit. La chirurgie était prévue avec une autogreffe de coccyx et du plasma riche en plaquettes. Un défaut osseux de 2,8 cm de long a été créé et la lésion lytique a été retirée. Une caudectomie a été réalisée; les 6e et 7e os coccygiens ont été prélevés, placés dans le défaut et fixés au radius avec une plaque de verrouillage. Les restes d’os coccygien ont été broyés, mélangés avec du plasma riche en plaquettes et utilisés pour combler les défauts osseux. Il n’y avait aucune évidence de non-union ou de retard de consolidation lors de l’examen de suivi à 18 mois.

Message clinique clé :

Sur la base des résultats de l’étude, nous avons déduit qu’une autogreffe de coccyx et du plasma riche en plaquettes peuvent être utilisés pour une reconstruction réussie d’un défaut radial distal.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Nonunion is a major complication in the treatment of radial fractures in small-breed dogs (1). The occurrence rate of nonunion fractures in dogs is 60% in the radius, 25% in the tibia, and 15% in the femur (2). The incidence of distal radial and ulnar fractures is high in small-breed dogs, and these dogs are prone to nonunion. The high risk for nonunion of distal radius fractures in small breeds is attributed to the poor development of vasculature at the distal metaphysis and a medullary cavity, which is very small or non-existent compared to that in large breeds (2–4). Fracture nonunion is diagnosed when there is no radiographic evidence of bone consolidation, including defects between the fracture ends, closed medullary cavity, sclerosis, hypertrophy, or atrophy of bone fragments (1). There are 2 basic types of nonunion fractures: a viable type that is vascular and biologically reactive, and a nonviable type that is poorly vascular and nonreactive (5). Necrotic nonunion is a nonviable type of nonunion fracture that often occurs after infection or excessive motion at the fracture site. Sequestra, defined as fragments of dead bone tissue formed within the surrounding diseased or injured bone, can be detected on radiographs, with increasing sclerotic changes noted over time (5).

Surgery is indicated as a treatment option in all cases of nonunion fractures. A bone graft can be used to promote early formation of a bridging callus, to consolidate delayed union or nonunion, and to fill the bone defect (1). An autograft is considered the gold standard treatment owing to its osteoinductive, osteoconductive, and osteogenic potential, which are considered essential factors in fracture healing (6). However, data on the use of a coccyx autograft to fill a bone defect are lacking in the literature, and it can be challenging to find a suitably shaped bone autograft for reconstruction of a bone defect.

This case report presents a detailed description of the use of a coccyx autograft, corticocancellous bone graft from remaining coccyges, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and a locking plate to promote rapid fracture healing of a distal radial nonunion fracture in a small-breed dog.

Case description

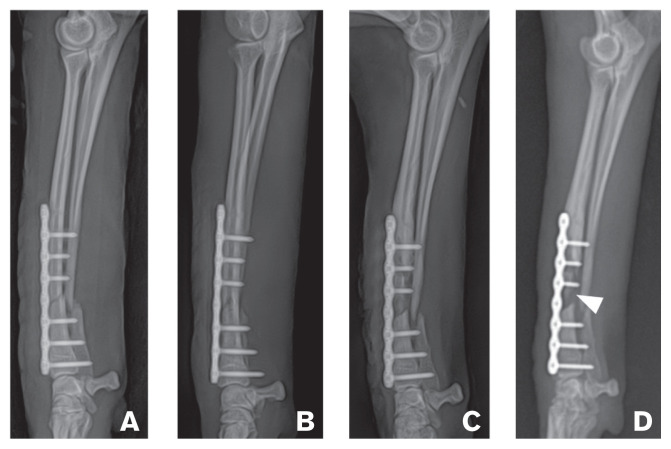

An 11-month-old, 4.3-kg, spayed female poodle was referred for treatment of a right radio-ulnar nonunion fracture. The dog had a history of surgical correction of the radius fracture, with internal fixation performed 1 mo before our initial evaluation. However, that fracture had not healed. Serial radiographic examinations of the fracture area conducted by the primary care veterinarian revealed progressive bone resorption on the right antebrachium (Figure 1). On presentation, the dog had non-weight-bearing lameness of the right forelimb, with pain and swelling of the right forelimb on palpation. Hematology and serum biochemistry findings were unremarkable. Radiographic examination revealed a distal radial defect between the bone fragments, a sequestrum, a closed medullary cavity sealed over with sclerotic bone, and atrophy of bone fragments (Figure 1 D). A diagnosis of a nonunion fracture of the distal diaphyseal radius and ulna was made.

Figure 1.

Mediolateral radiographs of the right antebrachium showing marked progression of bone resorption and signs of nonunion. A — Application of plate fixation for repair of oblique fracture on the distal radius of a dog. B — After 3 wk, continuity of distal cortex is visible, but the gap of proximal dorsal cortex and fracture line is widened. C — At the 4th week, medullary cavity appears closed on the proximal fragment of the radius; the fracture line is present at the 2nd screw on the proximal fragment of the radius. D — At the 5th week, sequestrum (arrowhead), lack of callus formation, closed medullary cavity sealed over with sclerotic bone, and atrophy of end of proximal fragment were present.

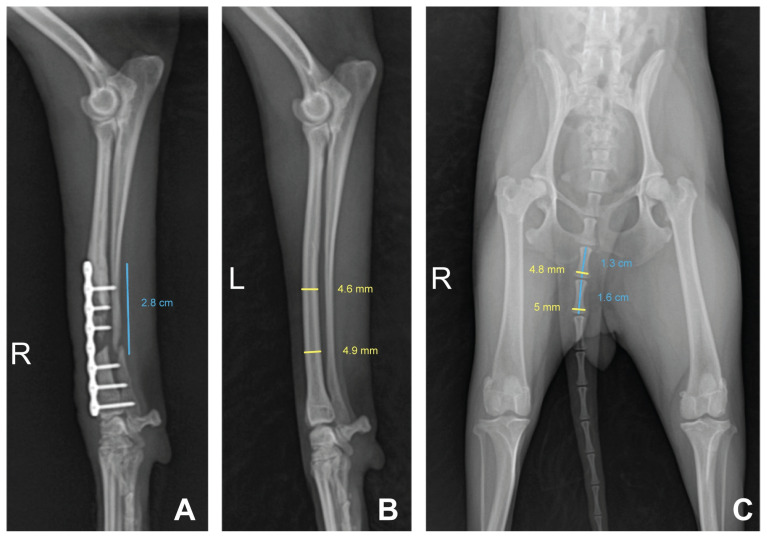

For preoperative surgical planning, the bone defect was estimated using conventional radiography. Medullary cavity covered by the plate was closed up to the middle diaphysis, and bone atrophy was confirmed at the end of the proximal fragment of the radius. Therefore, it was determined that these parts of the radius be removed (Figure 1 D). Consequently, the defect between the radial bone fragments was estimated to be 2.8 cm long (Figure 2 A). Since the 6th and 7th coccygeal vertebrae were similar in diameter as the distal radius, they were chosen as autograft materials (Figure 2 B). To enable good fit and insertion of the autograft bones into the bone defect, we selected a bone that was longer than the actual defect. After caudectomy, the 8th, 9th, and 10th coccygeal vertebrae were saved for use with PRP, as PRP has cytokines and growth factors that promote bone grafting.

Figure 2.

Mediolateral radiograph of the right antebrachium showing the estimated length of the defect planned for osteotomy and anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis showing coccygeal vertebrae. A — The defect, including lytic lesion removal and closed medullary cavity, was estimated to be 2.8 cm long. B — The diameter of distal radius on the contralateral antebrachium was estimated. C — The 6th and 7th coccyx vertebrae were similar in diameter to the distal radius; thus, both were chosen as autograft materials. Bones longer than the defect were selected as autografts to enable a good fit and insertion into the defect. After caudectomy, the 8th, 9th, and 10th coccygeal vertebrae were ground, mixed with PRP, and used to fill gaps.

Surgical intervention was performed for repair of the nonunion fracture using a coccygeal vertebra autograft and PRP. Premedication consisted of intravenous injections of the following: 0.02 mg/kg atropine sulfate, 30 mg/kg cefazolin, and 0.1 mg/kg butorphanol. General anesthesia was induced with 4 mg/kg propofol and maintained with isoflurane in oxygen. After induction of anesthesia, partial caudectomy was performed by disarticulating the 5th and 6th coccygeal vertebrae. Both ends of the 2 harvested coccygeal bones — the 6th and 7th — were cleared of all soft tissues using a rongeur, and they were covered with saline-soaked gauze. Samples from the remaining coccygeal bones — the 8th, 9th, and 10th vertebrae — were ground into fine pieces and mixed with 1.5 mL of PRP.

Concurrent with caudectomy, 10 mL of blood was collected via jugular venipuncture for PRP preparation outside the surgical field. The blood samples were processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (PROSYS ACT 10; Prodizen, South Korea). Subsequently, 3 mL of PRP was obtained and divided into volumes for injection (1.5 mL) and mixing (1.5 mL) for use with the ground bones. A surgical approach to the graft site was initiated while the bones were being ground.

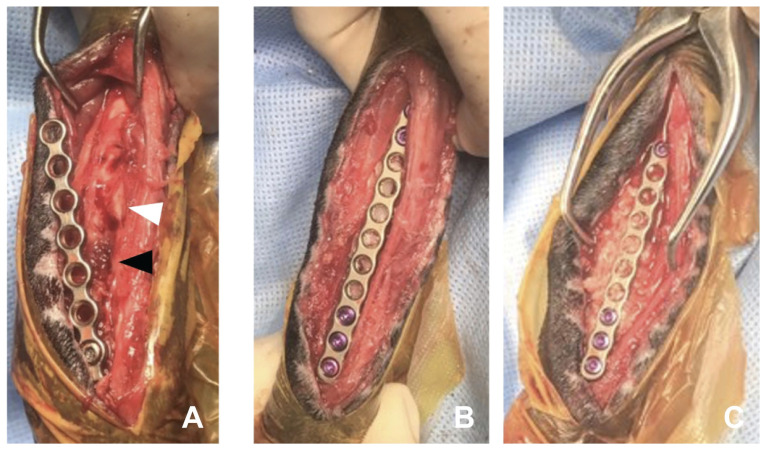

Following a craniomedial approach to the right radius, fracture instability and loosened screws were identified. One of the screws previously applied to the plate was submitted for culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Brown necrotic tissue was visible beneath the bone plate, and a relatively thin-walled delicate callus and sequestra were at the fracture site (Figure 3 A). Both ends of the bone fragments of the radius appeared macroscopically atrophic and devitalized. The directly visible fractured end and medullary cavity were cleared of fibrous scar tissue. The nonunion site was decorticated subperiosteally using an oscillating saw. Then, the medullary cavity of the bone fragments was exposed with a 20-gauge needle. Lavage was performed, and a 2.8-cm bone defect was created on the radius. The whole 6th coccygeal vertebra was inserted into the distal portion of the defect, whereas the whole 7th vertebra was inserted into the proximal portion, given that the diaphysis of the radius was slightly thicker in the distal portion. Both bone fragments were pulled open to prevent the grafted bones from loosening and to fit tightly. Bridging plate fixation using a 1.5-mm locking compression plate, was stabilized with 3 screws on each side (Figure 3 B). The 3 proximal screws were drilled into the intact bony surface of the proximal fragment, but the distal fragment did not have enough space for the new screws; therefore, screws with same diameter as those used in the previous surgery were installed in the same location. To fill the gaps around the vertebral arch of the coccygeal vertebrae bilaterally, previously prepared pieces of the ground bone and PRP were packed around the coccyx graft, and the remaining PRP was injected into the grafted site (Figure 3 C). The muscles were then apposed around the graft, and the subcutaneous tissues and skin were closed routinely. The limb was dressed using the Robert Jones bandage.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative photographs illustrating reconstruction of radial defect using a coccyx autograft with PRP. A — Brown necrotic tissue (black arrowhead) and lytic bone end (white arrowhead) are visible beneath the bone plate. B — Two coccygeal vertebrae were used to fill the defect; a 1.5-locking plate was used for fixation over the newly grafted bones. The 6th coccygeal vertebra was inserted into the distal portion of the defect and the 7th into the proximal portion, as the diaphysis of the radius is slightly thicker in the distal portion. Both grafted bones are immediately under the unscrewed portion of the plate. C — Chopped bone pieces of the coccygeal vertebrae mixed with PRP filled gaps around the graft, and 1.5 mL of PRP was injected into the graft site. The part of the plate directly over the 2 grafted bones has no screws. Two grafted bones lie just below the unscrewed portion of the plate.

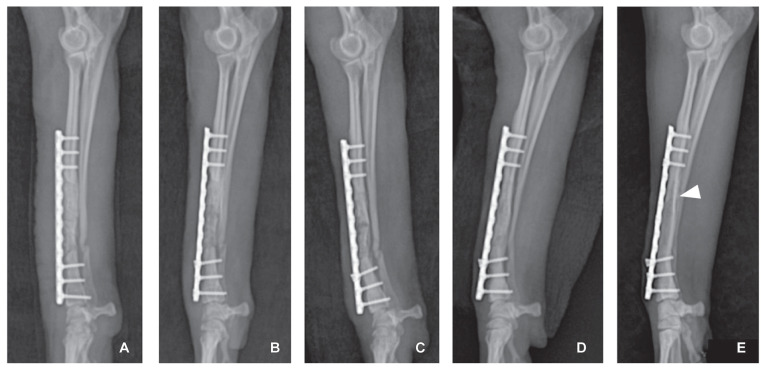

While awaiting sensitivity results, treatment was initiated with the following empirical antibiotics: 30 mg/kg cefazolin, 5 mg/kg enrofloxacin, and 10 mg/kg metronidazole. Bacterial culture from the screw at the fracture nonunion site was positive for Enterobacter cloacae; therefore, the initial antibiotics were discontinued, and 10 mg/kg gentamicin was administered q24h for 4 wk. Because the dog was young and had developed antibiotic resistance, gentamicin was used to prevent any infectious nonunion relapse and to promote cure. Furthermore, the dog was closely monitored for side effects of the drug and recurrence of clinical symptoms through periodic blood and radiological examinations. Fracture healing was monitored by radiography (Figure 4). Continuity of the cortex and absence of the remaining visible fracture line were identified, the medullary cavity was partially reconstituted, and a bone union with the graft was noted in the 13th week after placement of the coccygeal vertebra autograft (Figure 4 D). In the 3rd week, the 4th distal screw head was slightly loosened and cranially migrated (Figure 4 B). This was likely caused by weakening of the holding strength of the screw, as it was inserted into the existing screw hole.

Figure 4.

Postoperative radiographs showing proper alignment after coccyx autograft. A — Immediately after surgery to address fracture nonunion. B — In the 3rd week, bone opacity was reduced in the grafted coccygeal vertebrae. The 4th distal screw head was slightly loosened and had migrated cranially. C — External callus formation on the proximal fragment and the distal fragment confirmed on the 4th week. D — At the 13th week, continuity of medullary cavity and cortex between the bone fragments of the radius were identified, and bone union was visible. E — At 18 mo after the coccyx autograft, there was no remaining visible fracture line. The boundary between the cortical bone and the medullary cavity was markedly visible from the proximal end to the distal third of the radius (arrowhead).

Discussion

In our study, the dog had a nonunion fracture in the distal diaphysis of the radius and was diagnosed with infectious atrophic nonunion. The critical size defect is the smallest osseous defect that does not heal spontaneously, and bone defects exceeding a critical length lead to nonunion. Although the minimum size that renders a defect “critical” is not firmly established, it has been defined as 2 to 2.5 times the diameter of the long bone in human medicine (7,8) and 1.5 times the diameter of the tibia in dogs and cats (9,10). In our study, the length of the bone defect was 28 mm, approximately 6 times the diameter of the distal diaphysis of the opposite intact radius at 4.7 to 5.1 mm; therefore, this critical size defect was not expected to heal spontaneously without surgical intervention.

In veterinary medicine, the fibula, rib, iliac crest, and coccyx have been used as autograft materials (6,11). In our study, the coccyx was used as the autograft material because of the shape of the lesion, suitable characteristics of the coccyx, good bone strength, ease of surgery, fewer side effects than those reported for other surgeries for harvesting grafts, and shape similar to that of the radius. Moreover, the diameter of both ends of the 6th and 7th coccygeal vertebrae was 5 to 6 mm, similar to that of the radius defect. Contrastingly, the rib is curved, the fibula is very thin, and the iliac crest provides only a small amount of bone, making them less than ideal options for performing an autograft of cortical or cancellous bone in the radius. A previous study demonstrated that the coccyx has a higher ratio of cancellous bone than the tibia, rib, and iliac crest (11). The diameters of the 6th and 7th coccygeal vertebrae were similar to the diameter of the radius defect. With the 5th or other cranial coccygeal vertebrae, there is a possibility of adverse postoperative events such as neuroma, fecal incontinence, and rectocutaneous fistula (12).

Previous reports by Yeh et al (13) and Goto et al (14) have described coccygeal transplantation for long-bone defects in dogs. Yeh et al (13) have reported a vascularized coccyx autograft on the tibial defect, whereas Goto et al (14) have reported a coccyx autograft by overlapping 2 coccygeal bones in parallel, transplanting them in the tibia defect, and fixing them with 2 plates (14). In both these cases, the grafted coccyx bones were remarkably smaller in diameter than the tibia. If bones with different diameters are fixed together, bone alignment could be unstable with increased motion around the fracture site, with potential for delayed bone union. The method described in our case report was a graft of coccygeal bone fragments of the same diameter as that of the fractured radius. Another case report has described the treatment of radio-ulnar nonunion with coccygeal vertebra transfer; however, it lacked a detailed description of the operative procedure (15).

Some anatomical considerations may increase the likelihood of a successful coccygeal autograft in long-bone defects. The dorsal surface of the canine coccygeal vertebrae has articular processes, and traces of the transverse processes remain on the dorsolateral sides. Thus, canine coccyges do not have a uniform cylindrical shape (16). In our case, some of the harvested coccygeal vertebrae were chopped into fine pieces and inserted in the hollows on both sides of the transplanted coccyx body to conform to the cylindrical shape of the radius. Ground bones have both cortical and cancellous bone graft properties. Cancellous bones have mesenchymal stem cells that differentiate into osteogenic cells, thereby promoting bone healing. Cortical bones have more strength than other types of bone-grafting materials (6). Therefore, grinding the entire coccygeal vertebrae increased the bone-healing effects.

Platelet-rich plasma was used to accelerate bone healing in a difficult-to-heal distal radius nonunion fracture of a small-breed dog. Regarding bone transplantation onto the defect area, the bone density and maturation rate were significantly greater when grafts were used in combination with PRP than when used alone (17). The process of bone fracture healing comprises a well-integrated series of biological events initiated by growth factors (18). Most in-vitro preclinical studies have reported that PRP facilitates bone regeneration and provides an angiogenesis effect on bone healing; some clinical studies have reported that PRP hastened bony healing (18).

Radiographic evaluation was conducted to assess for infection and healing of the bone after grafting. In conventional bone healing, fibrin-rich granulation tissues are formed around the ends of the bones, and cartilage is generated through endochondral formation accompanied by bone absorption and mineralization, which later becomes the hard callus (19). At 5 to 10 d after fracture repair, the margins of the fracture site become sharp and demineralized (19), leading to the appearance of wider fracture lines on radiographs. In our study, the opacity of the grafted bone decreased on Day 10, indicating that the bones were resorbed and demineralized, a normal process in the early phases of bone healing.

During the 3rd week, an external callus was generated between the 2 grafted coccyges. The external callus connected the fractured ends of the bone, making it firm and able to support weight. During the 13th week, continuity was established in the cortex between the grafted bones and the proximal bone fragments of the radius, and bone union was observed. The external callus on the outer end and the internal callus on the inner side of the periosteum gradually develop into lamellar bone and a medullary cavity, respectively (19). Consequently, the grafted coccyx bones are connected with the medullary cavity of the radius. Compared to the general bone healing period of 3 mo (20) and the findings of Yeh et al (13), wherein bone union was observed between 16 and 23 wk after coccyx transplant, we observed bone union during the 13th week, suggesting a shortened healing period.

At a follow-up examination 18 mo after coccyx transplantation, there were no remaining fracture lines or boundary lines between the bones, and the medullary cavity extended to the distal third of the radius on radiography. In conclusion, combining a coccyx graft, corticocancellous bone from the remaining caudal coccyges, and PRP promoted bone union of the large bone defect. CVJ

Footnotes

Ethics statement: Ethical review and approval were not required for the animal study because this is a case report. Written informed consent was obtained from the owner for participation of the animal in this study.

Author contributions: JYC: assisted in the operation, collected data, and wrote the manuscript; HYY: operated, contributed to the final version of the manuscript, and supervised the case; both the authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the manuscript.

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.dos Santos JF, Ferrigno CRA, dos Dal-Bó IS, Caquías DFI. Nonunion fractures in small animals — A literature review. Semina: Ciências Agrárias. 2016;37:3223–3230. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munakata S, Nagahiro Y, Katori D, et al. Clinical efficacy of bone reconstruction surgery with frozen cortical bone allografts for nonunion of radial and ulnar fractures in toy breed dogs. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2018;31:159–169. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1631878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch JA, Boudrieau RJ, DeJardin LM, Spodnick GJ. The intraosseous blood supply of the canine radius: Implications for healing of distal fractures in small dogs. Vet Surg. 1997;26:57–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1997.tb01463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aikawa T, Miyazaki Y, Shimatsu T, Iizuka K, Nishimura M. Clinical outcomes and complications after open reduction and internal fixation utilizing conventional plates in 65 distal radial and ulnar fractures of miniature-and toy-breed dogs. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2018;31:214–217. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1639485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeCamp CE, Johnston SA, Dejardin LM, Schaefer SL. Delayed union and nonunion. In: Brinker Piermattei, Flo, editors. Handbook of Small Animal Orthopedics and Fracture Repair. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Saunders, Elsevier; 2016. pp. 167–168. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston SA, Tobias KM. Bone grafts and substitutes In: Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal Expert Consult. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Saunders, Elsevier; 2012. pp. 676–684.pp. 719pp. 783–794. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsey RW, Gugala Z, Milne E, Sun M, Gannon FH, Latta LL. The efficacy of cylindrical titanium mesh cage for the reconstruction of a critical-size canine segmental femoral diaphyseal defect. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1438–1453. doi: 10.1002/jor.20154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang W, Yeung KWK. Bone grafts and biomaterials substitutes for bone defect repair: A review. Bioact Mater. 2017;2:224–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraus KH, Kadiyala S, Wotton H, et al. Critically sized osteo-periosteal femoral defects: A dog model. J Invest Surg. 1999;12:115–124. doi: 10.1080/089419399272674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toombs JP, Wallace LJ, Bjorling DE, Rowland GN. Evaluation of Key’s hypothesis in the feline tibia: An experimental model for augmented bone healing studies. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serafini GMC, Pippi NL, Libardoni RdN, et al. Vértebra coccígea como alternativa a autoenxertia óssea tradicional avaliação tomográfica e biomecânica em cães ex vivo. Braz J Vet Med. 2017;39:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knight SM, Radlinsky MG, Cornell KK. Postoperative complications associated with caudectomy in brachycephalic dogs with ingrown tails. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2013;49:237–242. doi: 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeh LS, Hou SM, Lin AC. Vascularized autogenous canine coccygeal bone transfer. Microsurgery. 1991;12:326–331. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920120503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goto M, Katayama M, Miyazaki A, Shimamura S, Okamura Y, Uzuka Y. Use of a coccyx autograft for repair of tibial fracture nonunion in a dog. Anim Clin Med. 2014;23:119–123. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piccionello AP, Salvaggio A, Volta A. Caudal vertebra transfer: Treatment of radio-ulnar nonunion and severe bone shortening in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2017;1:56. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermanson JW, de Lahunta A. Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Saunders, Elsevier; 2018. pp. 287–290. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oryan A, Alidadi S, Moshiri A. Platelet-rich plasma for bone healing and regeneration. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2016;16:213–232. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2016.1118458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Xing F, Luo R, Duan X. Platelet-rich plasma for bone fracture treatment: A systematic review of current evidence in preclinical and clinical studies. Front Med. 2021;8:676033. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.676033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marsell R, Einhorn TA. The biology of fracture healing. Injury. 2011;42:551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henry GA, Cole R. Fracture healing and complications in dogs. In: Thrall DE, editor. Textbook of Veterinary Diagnostic Radiology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Saunders, Elsevier; 2018. pp. 376–381. [Google Scholar]