Abstract

Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma (DIA) is rare, cystic and solid tumor of infants usually found in superficial cerebral hemispheres. Although DIA is usually benign, uncommon cases bearing malignant histological and aggressive clinical features have been described in the literature. We report a newborn patient who was diagnosed with a DIA and died postresection. Pathologic examination revealed that the main part of the tumor had benign features, but the internal region showed areas with a more aggressive appearance, with higher-proliferative cells, anaplastic GFAP positive cells with cellular polymorphism, necrosis foci, vascular hyperplasia with endothelial proliferation and microtrombosis. Genetic study, performed in both regions of the tumor, showed a BRAF V600E mutation and a homozygous deletion in PTEN, without changes in other relevant genes like EGFR, CDKN2A, TP53, NFKBIA, CDK4, MDM2 and PDGFRA. Although PTEN homozygous deletions are described in gliomas, the present case constitutes the first report of a PTEN mutation in a DIA, and this genetic feature may be related to the malignant behavior of a usually benign tumor. These genetic findings may point at the need of further and deeper genetic characterization of DIAs, in order to better understand the biology of this tumor and to obtain new prognostic approaches, a better clinical management and targeted therapies, especially in malignant cases of DIA.

Keywords: Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma, PTEN, BRAF V600E, Atypical

Introduction

Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma (DIA) is a meningocerebral neuroepithelial tumor of infancy defined by a combination of distinctive clinicopathologic features [1]. DIA was first described as a meningocerebral astrocytoma attached to dura with desmoplastic reaction [2], and later was included in the World Health Organization defined as a desmoplastic cerebral astrocytoma of infancy [1]. DIA is considered a biologically benign neoplasm. The large majority of cases are usually diagnosed in the first two years of life [1, 3]. Despite the fact that DIA has been generally considered as a tumor of infants, it can also be seen in older patients. The non-infantile cases are rare, with few cases reported previously [3–12]. When surgical complete resection is achieved, it is followed by a favorable postoperative course. However, in some cases, atypical, aggressive, and multifocal variants of DIA have been described [11, 13–17].

Here, we report a rare case of DIA in a male newborn, with histological characteristics of malignancy, BRAF V600E mutation and PTEN homozygous deletion. Genetic studies of DIA are very scarce. Since its first description in 1984, only twelve works performed genetic search of DIA mutations, and most of them focused exclusively on the detection of the well characterized BRAF V600E mutation [10–12, 18–26]. To our knowledge, only eleven cases of DIA with this BRAF mutation have been described [10–12, 18–20, 23, 26], and mutations in PTEN have never been reported. Table 1 shows a summary of the existing literature of DIA, highlighting the publications with genetic studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cases of DIA described in literature

| References | Age | Sex | Genetics | BRAF mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taratuto et al. [2] | 6 months | Female | No | – |

| 6 months | Female | No | – | |

| 6 months | Male | No | – | |

| 1.5 month | Male | No | – | |

| 7 months | Male | No | – | |

| 9 months | Female | No | – | |

| Chacko et al. [4] | 7 years | Female | No | – |

| VandenBerg (9 cases) [27] | 1.5 to 14 months | 4 males/5 females | No | – |

| Rushing et al. [28] | 6 months | Female | No | – |

| Al-Sarraj and Bridges [29] | 8 months | Male | No | – |

| Prayson [30] | 3 months | Male | No | – |

| Setty et al. [13] | 4 months | Male | No | – |

| Mallucci et al. [5] | 3.5 years | – | No | – |

| 3 months | – | No | – | |

| 5 months | – | No | – | |

| Sugiyama et al. [31] | 4 months | Female | No | – |

| 2 months | Female | No | – | |

| 5 months | Female | No | – | |

| 4 months | Female | No | – | |

| Kato et al. [6] | 9 years | Male | No | – |

| Darwish et al. [14] | 4 months | Male | No | – |

| Beppu et al. [32] | 1 year | Male | No | – |

| Santhosh et al. [7] | 11 years | Male | No | – |

| Tsuji et al. [33] | 3 months | Male | No | – |

| Ulu et al. [3] | 4 years | Female | No | – |

| Gu et al. [34] | 1 month | Male | No | – |

| Uro-Coste et al. [8] | 5 years | Male | No | – |

| Phi et al. [15] | 7 months | Female | No | – |

| Rasalkar et al. [9] | 18 years | Female | No | – |

| Al-Kharazi et al. [16] | 3 months | Male | No | – |

| Gessi et al. [18] | 2 months | Male | Yes | No |

| 2 years | Male | Yes | BRAF V600E | |

| 3 months | Male | Yes | No | |

| 8 months | Female | Yes | No | |

| Karabagli et al. [10] | 6 years | Male | Yes | BRAF V600E |

| Koelsche et al. [19] | 4 months | Male | Yes | BRAF V600E |

| Abuharbid et al. [20] | 11 months | Female | Yes | BRAF V600E |

| Greer et al. [21] | 3 months | Female | Yes | No |

| 1 month | Male | Yes | No | |

| 11 months | Female | Yes | No | |

| Narayan et al. [17] | 8 months | Female | No | – |

| Samkari et al. [35] | 1.5 years | Male | No | – |

| Wang et al. [11] | 3 months | Female | Yes | No |

| 7 months | Female | Yes | BRAF V600E | |

| 11 years | Female | Yes | No | |

| 6 years | Male | Yes | BRAF V600E | |

| 4 months | Female | Yes | BRAF V600E | |

| Chatterjee et al. [12] | 10 years | Female | Yes | BRAF V600E |

| 10 years | Male | Yes | BRAF V600E | |

| Naylor et al. [22] | 3 months | Female | Yes | No |

| Van Tilburg et al. [23] | 4.5 months | Male | Yes | BRAF V600E |

| Clarke et al. [24] | > 1 year | Female | Yes | No |

| ≤ 1 year | Female | Yes | No | |

| ≤ 1 year | Male | Yes | No | |

| Imperato et al. [25] | 4 months | Female | Yes | No |

| 7 months | Male | Yes | No | |

| 8 months | Male | Yes | No | |

| 1 year | Female | Yes | No | |

| 3 months | Male | Yes | No | |

| 3 months | Female | Yes | No | |

| 3 months | Male | Yes | No | |

| 3 months | Female | Yes | No | |

| 3 months | Male | Yes | No | |

| 11 months | Female | Yes | No | |

| 8 months | Female | Yes | No | |

| 2 months | Female | Yes | No | |

| Chiang et al. [26] | 2 months | Female | Yes | BRAF V600E |

| 1 year | Female | Yes | No | |

| 1 month | Female | Yes | No | |

| Megías et al. (present case) | 1 week | Male | Yes | BRAF V600E |

Genetic studies and presence of BRAF mutation

Case presentation

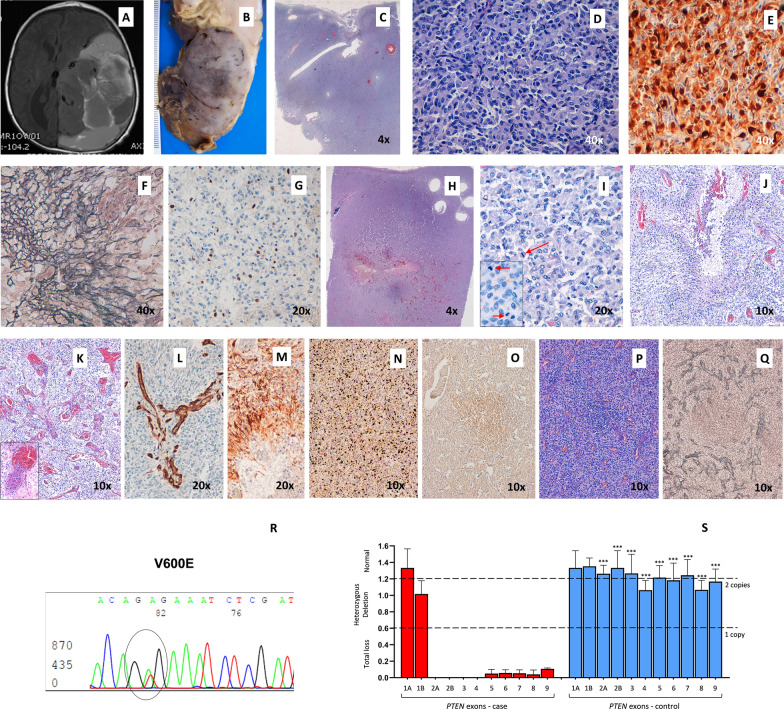

The patient was a newborn male, product of the first pregnancy of a 27-year-old mother. Ultrasonography controls during pregnancy reported an adequate gestational age, with a 88 mm biparietal diameter at week 34. However, a subsequent control at week 39 showed a high biparietal diameter, 109 mm and an intracranial hypoechoic image. An emergency caesarean was performed. External analysis showed a cephalic perimeter of 38 cm, cephalic suture softening and prominent fontanels. A MRI scan on day 1 showed a supratentorial tumor of 75 × 63 × 76 mm with heterogenic signal and cystic areas. The tumor produced a midline deviation, hydrocephaly and subfalcian herniation (Fig. 1A). On day 5, surgery was performed. As a result of a hemorrhagic complication, the patient died 24 h later. The tumor was diagnosed as DIA. Postmortem examination of the brain revealed a large, well-delineated tumor in the right parieto-occipital region attached to the dura. Upon section the tumor showed solid areas with a firm texture and a grayish and pale pink color. Residual hemorrhagic areas of the surgical intervention were observed (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Neuropathological and genetic findings in DIA. Heterogeneous and cystic tumor in a cranial scan (A). A well-delineated tumor in the postmortem examination (B). Histopathological pattern of DIA: general features (C), atypical astrocytes with a gemistocytic pattern (hematoxylin and eosin stain) (D), GFAP-positive neoplastic cells (E), desmoplastic stroma in Gomori samples (F) and low proliferative index (G). Histopathological aggressive pattern in DIA: general features (H), morphological atypical cells with mitosis (I), necrosis with perinecrotic palisading neoplastic cells (J), vascular hyperplasia and microthrombosis (K), CD34-positive expression in microvascular structures (L), GFAP-positive neoplastic cells in perinecrotic areas (M), high proliferative index (N), area with a small-cell population which express CD133 protein (O), that alters the reticulin (P) and vessel distribution (Q). Molecular alterations: BRAF V600E mutation (R) and PTEN deletion in MLPA analysis (S)

Histopathological study revealed that the main part of the tumor was composed of uniform atypical astrocytes with moderate pleomorphic nuclei and large eosinophilic cytoplasms. These had a gemistocytic pattern and spindle-shaped cells with benign appearance, forming irregular fascicles or a storiform pattern (Fig. 1C, D). Neoplastic cells showed GFAP expression (Fig. 1E). A fibrillary network of reticulin Gomori-positive fibers completed the morphology (Fig. 1F). A low proliferative index (< 1 mitosis/HPF; < 1% Ki-67 labeling index) (Fig. 1G) without necrosis or vascular endothelial proliferative features was found in these areas. No ganglionic synaptophysin-positive cells were identified. The astrocytic differentiation with heterogeneity in cellular patterns, absence of ganglionic neuronal cells and desmoplastic stroma, support the diagnosis as DIA. However, the internal part of the tumor showed areas with a more aggressive appearance (Fig. 1H, I), with anaplastic GFAP positive cells with cellular polymorphism. Micronecrosis foci (Fig. 1J) and macronecrosis, vascular hyperplasia with endothelial proliferation and microtrombosis (Fig. 1K, L) were observed. An increased proliferative index (11 mitoses/HPF; ≥ 25% Ki-67) (Fig. 1M, N) completes this aggressive histopathological pattern. Finally, the tumor showed a non-desmoplastic area of small embryonal-like cells with low level of differentiation and CD133 expression (Fig. 1O). These cells altered the distribution of the reticulin network and vessels around it (Fig. 1P, Q).

All the genetic studies were performed in the two areas of the tumor, the part with more benign features and the part with an aggressive histological pattern. For the mutational analysis, BRAF was amplified by PCR and the products were analysed using the ABI-PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer automated sequencer. For the study of deletions, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) was used (MS–MLPA probe sets P105-C2 and PO44-B1, MRCHolland, The Netherlands). Results showed a BRAF mutation that led to a substitution of valine by glutamic acid at position 600 (V600E), in both parts of the tumor (Fig. 1R). Moreover, a homozygous deletion in PTEN (exons 2 to 9) was found in both areas (Fig. 1S). No changes in EGFR, CDKN2A, TP53, NFKBIA, CDK4, MDM2 and PDGFRA were found.

Discussion and conclusions

It is generally accepted that DIA is a low-grade, biologically benign neoplasm [1]. Clinical malignancy is related to the size of the tumor and to a non-successful surgical resection. However, different reports referred to an increase of the proliferative index, histological anaplastic features, endothelial proliferation and necrosis, supporting the existence of an atypical or histologically malignant form of DIA [11, 13–17].

Setty et al. described a case of DIA associated with clusters of malignant cells which expressed GFAP [13]. Darwish et al. also reported a patient with DIA who developed multiple cerebrospinal metastases [14]. Phi and colleagues showed the case of a DIA that recurred eight years after the first surgery and had transformed to overt glioblastoma [15]. Al-Kharazi et al. described a case bearing aggressive clinical and malignant histological features, which continued to grow despite intensive chemotherapy [16]. Narayan et al. reported a case of an infant diagnosed with multifocal, cranial and spinal DIA [17]. In 2018, Wang et al. found a case which recurred ten years after subtotal resection [11]. Finally, we present a case of a DIA with areas with anaplastic GFAP positive cells, necrosis, vascular hyperplasia with endothelial proliferation and increased proliferative index. With this background, it may be concluded that not all tumors with histological features of DIA behave in a benign way, and consequently a close postsurgical follow-up would be required.

Knowledge of genetic alterations in these tumors is limited. Table 1 summarizes the published reports of DIA, indicating whether genetic studies were performed or not. Gessi et al. performed a genome-wide DNA copy number analysis in combination with a multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification in four DIAs. One case presented focal losses in 17q24 and gains in 1q31.1, and other DIA showed gains in KDR/PDGFRA, MET, MDM2 and BRAF, but no specific locus appeared consistently [18]. From the few genetic features described in DIA, BRAF V600E mutation is considered relatively common and the most consistent of all [11, 19]. BRAF V600E mutation is involved in different types of tumors of the central nervous system like pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, ganglioglioma and extra-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma [36], but its relevance in DIA is still controversial. Gessi et al. studied four cases of DIA and described BRAF V600E mutation for the first time in this tumor. They found it only in one case and concluded that this mutation was rare in DIA-DIG [18]. Three independent cases of DIA with BRAF V600E mutation were published in the next two years, one of them being a non-infantile desmoplastic astrocytoma [10, 19, 20]. Greer et al. published three new cases, all of them negative for the mutation [21]. In 2018, Wang and colleagues examined five DIAs using targeted DNA exome sequencing and found BRAF V600E mutations in three of them and ATRX and BCORL1 mutations in one of them, a non-infantile anaplastic tumor [11]. Chaterjee et al. presented two cases of the non-infantile variant of DIA with the canonical V600E mutation, describing this mutation as frequent in DIG-DIA tumors [12]. Two more cases were published in 2018, one negative for BRAF V600E mutation and the other positive [22, 23]. In 2019, Guerreiro Stucklin et al. established the relevance of ALK/ROS1/NTRK/MET alterations in infant gliomas, especially in high-grade gliomas [37]. In 2020, Clarke et al. performed a histologic and genetic study in a collection of 241 gliomas from patients under 4 years of age. Fusions in receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) including those in ALK/ROS1/NTRK/MET were found in 21 cases of infantile hemispheric glioma and four DIGs, but in none of the DIA cases. From this series, only three cases were diagnosed as DIAs, without BRAF mutations, and one of them with losses in chromosomes 2, 9 and 22, and gains in 5 and 10 [24]. Imperato et al. published in 2021 a cohort of 12 DIA/DIG tumors, where no mutations in BRAF were found [25]. Finally, Chiang et al. in 2022, studied separately low-grade and high-grade areas in twelve DIA/DIGs, looking for distinct molecular characteristics [26]. From the twelve cases, only three were DIAs, one of them with the BRAF V600E mutation. The study concluded that no recurrent genetic alterations were identified in the series, and high-grade and low-grade areas did not have significant genetic differences that could explain their distinct morphology or biological behavior.

Taken together, although BRAF V600E mutation is now considered relatively common in DIA [11, 12, 19], it has been more associated with non-infantile cases of DIA [12], and its presence has been related with the absence of histological features of aggressiveness [11, 12, 36].

In the present work, we show a rare case of a DIA from a newborn, with histological features of malignancy, BRAF V600E mutation and a PTEN homozygous deletion. Both mutations were present in the different areas of the tumor, apparently showing a lack of correlation between the aggressiveness of the area and the genetic findings. Interestingly, although PTEN homozygous deletions are found in high-grade gliomas [38], the present case constitutes the first report of a PTEN mutation in a DIA. PTEN is a haploinsufficient gene tumor suppressor which regulates various cellular processes, including genomic stability, survival, proliferation and metabolism. Due to its role, a subtle decline or a partial inactivation of PTEN functions substantially induces susceptibility to cancer and tumorigenesis [39, 40]. Several studies suggest that the successive loss of each PTEN allele contributes to increase the aggressiveness of gliomas, being involved in the transition from the low to the high grade of these tumors [41–43] and the shortening of median life expectancy and survival [44, 45]. Similarly, the loss of PTEN could explain, at least partially, the malignant transformation of a typical benign tumor like DIA. Elucidating the mechanisms underlying tumorigenesis mediated by PTEN loss in gliomas would be important and can reveal its potential role in atypical DIAs with this mutation, like the present case.

Since no previous studies reported data about PTEN alterations in DIA, it is unknown whereas PTEN mutational status may provide useful information for the prognosis of this tumor, and distinguish a new PTEN-deficient category of aggressive DIAs. These genetic findings, concurrent with the anaplastic histological characteristics of the tumor, point at the possibility of analyze the mutational status of PTEN, together with BRAF and other still undiscovered gene mutations in new cases of DIA, in order to better understand the behavior of this rare tumor, provide a new classification of DIAs, achieve a better management of the patients and obtain new targeted molecular therapies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ana Clari for her technical support.

Abbreviations

- BRAF

B-Raf gene

- DIA

Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma

- DIG

Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HPF

High-power field

- MLPA

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PTEN

Phosphatase and tensin homolog gene

Author contributions

Conceptualization, JM, MC-N and CL-G; Methodology, LM-H, LN and TS-M; Software, JM, DM, J-MM, MS, MC-N, LN and CL-G; Validation, JM, MS, DM and CL-G; Formal analysis, JM, MS, J-MM, DM, MC-N, LN and CL-G; Investigation, MS, LM-H, TS-M, JM, SC-F, DM and CL-G; Resources, JM, DM, MC-N and CL-G; Data curation, SC-F, J-MM, MS, MC-N and CL-G; Writing—original draft, LM-H, TS-M, JM and CL-G; Writing—review and editing, JM, MC-N and CL-G; Visualization, LM-H, J-MM, TS-M, MS, PR, JM, SC-F, DM, MC-N and CL-G; Supervision, LM-H, J-MM, TS-M, JM, PR, SC-F, DM, MC-N and CL-G; Project administration, JM, MC-N and CL-G; Funding acquisition, TS-M, JM, and MC-N. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The funding sources have no involvement in the research and/or preparation of the article. This work was supported by Generalitat Valenciana-Spain (Grant Numbers: GV/2020/048, GRISOLIAP/2021/119 and IDIFEDER/2021/072), Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación-Spain (Grant Numbers PI14/01669, PID2019-108973RB-C22 and PCIN2017-117), Programa VLC-Bioclínic (Grant Number AP-2021-001) and GUTMOM INTIMIC-085 from the Joint Programming Initiative HDHL. Lisandra Muñoz thanks Generalitat Valenciana-Spain for her Grant (APOST/2020/196).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval for the study herein reported was provided by Institutional Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia and Clinic Hospital of Valencia (Ley 14/2007 de Investigación Biomédica, ethics committee approval on 2015/06/03).

Consent for publication

The tumor was obtained with the child’s parents’ understanding that it might be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Javier Megías and Teresa San-Miguel have contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Javier Megías, Email: javier.megias@uv.es.

Teresa San-Miguel, Email: teresa.miguel@uv.es.

Mirian Sánchez, Email: misanme2@alumni.uv.es.

Lara Navarro, Email: lara.navarro@uv.es.

Daniel Monleón, Email: daniel.monleon@uv.es.

Silvia Calabuig-Fariñas, Email: silvia.calabuig@uv.es.

José Manuel Morales, Email: j.manuel.morales@uv.es.

Lisandra Muñoz-Hidalgo, Email: lisandramh@gmail.com.

Pedro Roldán, Email: pedro.roldan@uv.es.

Miguel Cerdá-Nicolás, Email: jose.m.cerda@uv.es.

Concha López-Ginés, Email: concha.lopez@uv.es.

References

- 1.WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board (2021) World Health Organization classification of tumours of the central nervous system, 5th edn. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

- 2.Taratuto AL, Monges J, Lylyk P, Leiguarda R. Superficial cerebral astrocytoma attached to dura. Report of six cases in infants. Cancer. 1984;54:2505–2512. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841201)54:11<2505::AID-CNCR2820541132>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulu MO, Tanriöver N, Biçeroğlu H, Oz B, Canbaz B. A case report: a noninfantile desmoplastic astrocytoma. Turk Neurosurg. 2008;18:42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chacko G, Chandi SM, Chandy MJ. Desmoplastic low grade astrocytoma: a case report and review of literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1995;97:32–35. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(94)00051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mallucci C, Lellouch-Tubiana A, Salazar C, Cinalli G, Renier D, Sainte-Rose C, et al. The management of desmoplastic neuroepithelial tumours in childhood. Child’s Nerv Syst. 2000;16:8–14. doi: 10.1007/PL00007280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato M, Yano H, Okumura A, Shinoda J, Sakai N, Shimokawa K. A non-infantile case of desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:499–501. doi: 10.1007/s00381-003-0888-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santhosh K, Kesavadas C, Radhakrishnan VV, Abraham M, Gupta AK. Multifocal desmoplastic noninfantile astrocytoma. J Neuroradiol. 2008;35:286–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uro-Coste E, Ssi-Yan-Kai G, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Boetto S, Bertozzi AI, Sevely A, et al. Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma with benign histological phenotype and multiple intracranial localizations at presentation. J Neurooncol. 2010;98:143–149. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasalkar DD, Paunipagar BK, Ng A. Primary spinal cord desmoplastic astrocytoma in an adolescent: a rare tumour at rare site and rare age. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18:253–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karabagli P, Karabagli H, Kose D, Kocak N, Etus V, Koksal Y. Desmoplastic non-infantile astrocytic tumor with BRAF V600E mutation. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2014;31:282–288. doi: 10.1007/s10014-014-0179-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang AC, Jones DTW, Abecassis IJ, Cole BL, Leary SES, Lockwood CM, et al. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma/astrocytoma (DIG/DIA) are distinct entities with frequent BRAFV600 mutations. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16:1491–1498. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatterjee D, Garg C, Singla N, Radotra BD. Desmoplastic non-infantile astrocytoma/ganglioglioma: rare low-grade tumor with frequent BRAF V600E mutation. Hum Pathol. 2018;80:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Setty SN, Miller DC, Camras L, Charbel F, Schmidt ML. Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma with metastases at presentation. Mod Pathol. 1997;10:945–951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darwish B, Arbuckle S, Kellie S, Besser M, Chaseling R. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma/astrocytoma with cerebrospinal metastasis. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:498–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phi JH, Koh EJ, Kim S-K, Park S-H, Cho B-K, Wang K-C. Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma: recurrence with malignant transformation into glioblastoma: a case report. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011;27:2177–2181. doi: 10.1007/s00381-011-1587-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Kharazi K, Gillis C, Steinbok P, Dunham C. Malignant desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma? A case report and review of the literature. Clin Neuropathol. 2013;32:100–106. doi: 10.5414/NP300548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narayan V, Savardekar AR, Mahadevan A, Arivazhagan A, Appaji L. Unusual occurrence of multifocal desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma: a case report and review of the literature. PNE. 2017;52:173–180. doi: 10.1159/000455926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gessi M, zur Mühlen A, Hammes J, Waha A, Denkhaus D, Pietsch T. Genome-wide DNA copy number analysis of desmoplastic infantile astrocytomas and desmoplastic infantile gangliogliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:807–815. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182a033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koelsche C, Sahm F, Paulus W, Mittelbronn M, Giangaspero F, Antonelli M, et al. BRAF V600E expression and distribution in desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma/ganglioglioma. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2014;40:337–344. doi: 10.1111/nan.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abuharbid G, Esmaeilzadeh M, Hartmann C, Hermann EJ, Krauss JK. Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma with multiple intracranial and intraspinal localizations at presentation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2015;31:959–964. doi: 10.1007/s00381-015-2715-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greer A, Foreman NK, Donson A, Davies KD, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma/ganglioglioma with rare BRAF V600D mutation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017 doi: 10.1002/pbc.26350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naylor RM, Wohl A, Raghunathan A, Eckel LJ, Keating GF, Daniels DJ. Novel suprasellar location of desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma and ganglioglioma: a single institution’s experience. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2018;22:397–403. doi: 10.3171/2018.4.PEDS17638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Tilburg CM, Selt F, Sahm F, Bächli H, Pfister SM, Witt O, et al. Response in a child with a BRAF V600E mutated desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma upon retreatment with vemurafenib. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65:e26893. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke M, Mackay A, Ismer B, Pickles JC, Tatevossian RG, Newman S, et al. Infant high grade gliomas comprise multiple subgroups characterized by novel targetable gene fusions and favorable outcomes. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:942–963. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imperato A, Spennato P, Mazio F, Arcas E, Ozgural O, Quaglietta L, et al. Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma and ganglioglioma: a series of 12 patients treated at a single institution. Childs Nerv Syst. 2021;37:2187–2195. doi: 10.1007/s00381-021-05057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiang J, Li X, Jin H, Wu G, Lin T, Ellison DW. The molecular characteristics of low-grade and high-grade areas in desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma/ganglioglioma. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2022;48:e12801. doi: 10.1111/nan.12801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.VandenBerg SR. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma and desmoplastic cerebral astrocytoma of infancy. Brain Pathol. 1993;3:275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1993.tb00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rushing EJ, Rorke LB, Sutton L. Problems in the nosology of desmoplastic tumors of childhood. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1993;19:57–62. doi: 10.1159/000120701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Sarraj ST, Bridges LR. Desmoplastic cerebral glioblastoma of infancy. Br J Neurosurg. 1996;10:215–219. doi: 10.1080/02688699650040412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prayson RA. Gliofibroma: A distinct entity or a subtype of desmoplastic astrocytoma? Hum Pathol. 1996;27:610–613. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(96)90171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugiyama K, Arita K, Shima T, Nakaoka M, Matsuoka T, Taniguchi E, et al. Good clinical course in infants with desmoplastic cerebral neuroepithelial tumor treated by surgery alone. J Neuro-oncol. 2002;59:63–69. doi: 10.1023/A:1016309813752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beppu T, Sato Y, Uesugi N, Kuzu Y, Ogasawara K, Ogawa A. Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma and characteristics of the accompanying cyst: case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:148–151. doi: 10.3171/PED/2008/1/2/148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuji K, Nakasu S, Tsuji A, Fukami T, Nozaki K. Postoperative regression of desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma. No Shinkei Geka. 2008;36:1035–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu S, Bao N, Yin M-Z. Combined fontanelle puncture and surgical operation in treatment of desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma: case report and a review of the literature. J Child Neurol. 2010;25:216–221. doi: 10.1177/0883073809333542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samkari A, Alzahrani F, Almehdar A, Algahtani H. Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma and ganglioglioma: case report and review of the literature. NP. 2017;36:31–40. doi: 10.5414/NP300945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schindler G, Capper D, Meyer J, Janzarik W, Omran H, Herold-Mende C, et al. Analysis of BRAF V600E mutation in 1,320 nervous system tumors reveals high mutation frequencies in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, ganglioglioma and extra-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guerreiro Stucklin AS, Ryall S, Fukuoka K, Zapotocky M, Lassaletta A, Li C, et al. Alterations in ALK/ROS1/NTRK/MET drive a group of infantile hemispheric gliomas. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4343. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12187-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Genetic alterations and signaling pathways in the evolution of gliomas. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:2235–2241. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alimonti A, Carracedo A, Clohessy JG, Trotman LC, Nardella C, Egia A, et al. Subtle variations in Pten dose determine cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2010;42:454–458. doi: 10.1038/ng.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carracedo A, Alimonti A, Pandolfi PP. PTEN level in tumor suppression: How much is too little? Cancer Res. 2011;71:629–633. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ali IU, Schriml LM, Dean M. Mutational spectra of PTEN/MMAC1 gene: a tumor suppressor with lipid phosphatase activity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1922–1932. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.22.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwon C-H, Zhao D, Chen J, Alcantara S, Li Y, Burns DK, et al. Pten haploinsufficiency accelerates formation of high-grade astrocytomas. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3286–3294. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Navarro L, Gil-Benso R, Megías J, Muñoz-Hidalgo L, San-Miguel T, Callaghan RC, et al. Alteration of major vault protein in human glioblastoma and its relation with EGFR and PTEN status. Neuroscience. 2015;297:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ermoian RP, Furniss CS, Lamborn KR, Basila D, Berger MS, Gottschalk AR, et al. Dysregulation of PTEN and protein kinase B is associated with glioma histology and patient survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1100–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaichana KL, Chaichana KK, Olivi A, Weingart JD, Bennett R, Brem H, et al. Surgical outcomes for older patients with glioblastoma multiforme: preoperative factors associated with decreased survival. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:587–594. doi: 10.3171/2010.8.JNS1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.