Abstract

5-HT7 receptors (5-HT7R) are the most recently identified among the family of serotonin receptors. Their role in health and disease, particularly as mediators of, and druggable targets for, neurodegenerative diseases, is incompletely understood. Unlike other serotonin receptors, for which abundant preclinical and clinical data evaluating their effect on neurodegenerative conditions exist, the available information on the role of the 5-HT7R receptor is limited. In this review, we describe the signaling pathways and cellular mechanisms implicated in the activation of the 5-HT7R; also, we analyze different mechanisms of neurodegeneration and the potential therapeutic implications of pharmacological interventions for 5-HT7R signaling.

Keywords: 5-HT7, Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, Dementia, Neurodegeneration, Neuroprotection

Introduction

5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) 7 receptors (5-HT7R) are members of the family of 5-HT receptors identified in 1993, but their functional and pathological implications are incompletely understood (Bard et al. 1993; Lovenberg et al. 1993; Ruat et al. 1993). Like other serotonin receptors, their activation is mediated by G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling pathways. 5-HT7R is broadly expressed in the central nervous system (CNS), gastrointestinal tract, and other organs, where they potentially regulate different physiological functions including the sleep–wake cycle, body temperature, nociception, and gastrointestinal motility, to name a few (Sanger 2008; Ciranna and Catania 2014; Chang-Chien et al. 2015). The 5-HT7R gene is located in the chromosome 10 (q21-124), which contains 3 introns in the coding region, (Gellynck et al. 2013) moreover, 5-HT7R is expressed in four different isoforms, being 5-HT7R(A), 5-HT7R(B) and 5-HT7R(D) the ones isolated in humans, and 5-HT7R(A), 5-HT7R(B) and 5-HT7R(C) in rats, with no apparent functional distinction between each isoform (Heidmann et al. 1997). Of interest, 5-HT7R presents high homology between species (90%) but little homology with other 5-HT receptors (as low as 50%) (Hannon and Hoyer 2008).

Experimental data suggest that 5-HT7R may be an amenable therapeutic target in neurodegenerative disorders. However, no clinical studies have evaluated the role of 5-HT7R in neurodegenerative processes, although targeting other serotonin receptors (with drugs such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) has shown little clinical benefit in neurodegenerative conditions (Hüll et al. 2006; Lalut et al. 2017). Here, we aimed to review the potential role of 5-HT7R in neurodegeneration and their potential therapeutic implications, based on different in vivo and in vitro pre-clinical studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Common agonists and antagonists of 5-HT7R used in preclinical studies

| Name | Action mechanism | Administration route (dose) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| AS-19 | Selective full agonist | s.c (5 mg/kg), i.t. (5 µL at 100 µM), i.p. (10 mg/kg) | McDaid et al. (2020), Fields et al. (2015), Albayrak et al. (2013) |

| LP-12 | Selective full agonist | i.t. (10µL at 0.02–0.2 nM), cultures (300 nM) | Godínez-Chaparro et al. (2012), Samarajeewa et al. (2014) |

| LP-44 | Selective full agonist | i.p. (1,5 and 10 mg/kg) | Demirkaya et al. (2016) |

| LP-211 | Selective full agonist | i.p. (1,5 and 10 mg/kg), i.p. (0.25 mg/kg), i.p. (0.003–0.3 mg/kg),i.c.v. (0.2 µL at 2–6 mM) | Demirkaya et al. (2016), Liu et al. (2021), Norouzi-Javidan et al. (2016), (Monti et al. 2014) |

| Methiothepin maleate | Non-specific 5-HT1/6/7R agonist | Culture (10 µM) | Soga et al. (2007) |

| 8-OH-DPAT | Non-specific 5-HT1A/7R agonist | i.p. (02–0.4 mg/kg and 1.0 mg/kg) | Cassaday and Thur (2019), Odland et al. (2019) |

| SB-269970 | Competitive selective antagonist, quasi-full inverse agonist | i.p. (10 mg/kg) | Perez-García and Meneses (2005), Liu et al. (2021) |

| SB-258741 | Competitive selective antagonist, partial inverse agonist | s.c. (2.3 mg/kg and 3.5 mg/kg) | Pouzet (2002) |

| SB-258719 | Competitive selective antagonist | i.p. (5 mg/kg) | Brenchat et al. (2011) |

| HBK-15 |

Competitive non-selective 5-HT1A/3/7R antagonist |

i.p. (1.25 mg/kg) i.v. (1.25 mg/kg) | Pytka et al. (2018) |

| Lurasidone | Competitive non-selective 5-HT2A/7R antagonist | Microdialsis (3 mg/kg/d) | Okada et al. (2021) |

Methods

We performed a comprehensive search of the PubMed database English language literature to identify all original research and review articles regarding 5-HT7R localization, signaling pathways, effectors, its role in health in the central nervous system, and the pathology of selected neurodegenerative diseases. For that purpose, we included the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and main keywords for searches: 5-HT7, LP-211, LP-44, LP-21, AS-19, SB-269970, SB-656104-A, 5-HT7R mechanism of action, 5-HT7R signaling pathway, 5-HT7R effect, 5-HT7R distribution, 5-HT7R neuroprotection, excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, apoptosis, necrosis, unfolded protein response, endoplasmic reticle stress, amyloid β, tau tangles, tau oligomers, α-synuclein, inflammation, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, Frontotemporal dementia, dementia, and neurodegeneration. We also reviewed the articles cited in the reference lists of the articles identified during the search. The authors independently reviewed the selected articles. The search included articles available from 1993 (when the receptor was originally cloned) to March 2022.

Distribution in the CNS

5-HT7R is broadly expressed in different cell types in the CNS, including neurons, astrocytes, and microglia (Shimizu et al. 1998; Mahé et al. 2005; Guseva et al. 2014). CNS expression of 5-HT7R is not homogeneous; the highest expression occurs in the hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus (Thomas and Hagan 2004), and comparatively lower density occurs in the dorsal raphe, caudate nucleus, putamen, and substantia nigra (Martín-Cora and Pazos 2004). In the amygdala, 5-HT7R are present primordially in GABAergic interneurons; in other structures, their expression in specific neurons is not clear, hence of critical importance for therapeutic purposes (Kusek et al. 2021). Of biological and clinical relevance, the regional expression of 5-HT7R is evolutionarily conserved in mammals (Martín-Cora and Pazos 2004). 5-HT7R are also expressed in the digestive tract, aorta, and other tissues, exerting immunomodulatory effects as well as other organ-specific effects (Quintero-Villegas and Valdés-Ferrer 2019).

Cellular mechanisms and signaling pathways

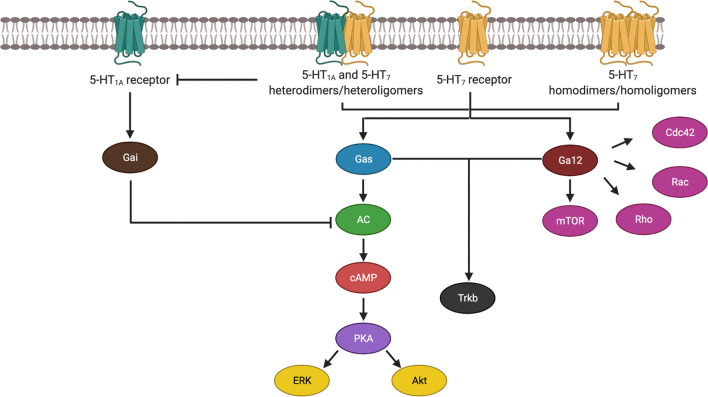

Like other GPCR, 5-HT7R are found in the cell membrane, where they form homodimers and homoligomers, with no known relevant differences between their biological functions (Smith et al. 2011; Guseva et al. 2014). In addition, 5-HT7R can form heterodimers and heterooligomers with 5-HT1A receptors (5-HT1AR), which in turn lead to diminished activity and increased internalization of 5-HT1A receptors without a discernible effect on 5-HT7R signaling or activity (Renner et al. 2005; Prasad et al. 2019). This is of biological relevance, as activation of 5-HT1AR results in activation of Gαi and reducing levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), also known as an extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), hence antagonizing the effects of the 5-HT7R-Gαs signaling cascade (Zhou et al. 2019).

The activation of 5-HT7R leads to the initiation of two possible signaling pathways: the canonical one, described when the receptor was originally cloned (Lovenberg et al. 1983) acts via Gαs (Fig. 1). The activation of this pathway, like in other GPCRs results in the phosphorylation of different adenylyl cyclases (AC) (Baker et al. 1998). This leads to cAMP production, activation of protein kinase A, and, finally, phosphorylation of different proteins, like ERK 1 and ERK 2, Akt, and tropomyosin-related kinase B (Trkb) (Errico et al. 2001; Johnson-Farley et al. 2005; Samarajeewa et al. 2014).

Fig. 1.

5-HT7 and 5-HT1A receptor signaling pathways and oligo/heterodimer formation. 5-HT7 receptor monomers (in yellow) can form homodimers or homoligomers, with the same signaling pathways and cellular effects. 5-HT7 can also form heterodimers or heteroligomers with 5-HT1A (in teal), resulting in the inhibition of the 5-HT1A signaling pathway, with no net effect downstream of 5-HT7. When activated, 5-HT7 activates Gas (canonical pathway) with a subsequent signaling cascade that results in the activation of ERK (also known as MAPK) and Akt; in contrast, the activation of Ga12 activates mTOR and different Rho family small GTPases. As illustrated, the phosphorylation of Trkb is mediated by both G proteins. AC adenylate cyclase, cAMP cyclic adenosine monophosphate, Cdc42 cell division control protein 42 homolog, ERK extracellular signal-regulated kinases, MAPK mitogen-activated protein kinases, mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin, Trkb Tropomyosin receptor kinase B

The Non-canonical signaling pathway of 5-HT7R acts via Gα12 (Guseva et al. 2014). This leads to the activation of Rho, Rac, and cell division control protein 42 (Cdc42) all part of the Rho family of small GTPases, which in neurons promote dendrite sprouting, formation of filopodia, and synaptogenesis (Hart, et al. xxxx; Kobe et al. 2012a; Speranza et al. 2013; Speranza et al. 2015; Marin and Dityatev 2017). Of relevance, Trkb expression (a brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF] receptor) appears to be enhanced by both Gαs and Gα12 (Fig. 1) (Samarajeewa et al. 2014). These signaling pathways may be of therapeutic relevance for neurodegenerative diseases, although few studies have so far evaluated these effects (Hashemi-Firouzi et al. 2017; Costa et al. 2018; Quintero-Villegas et al. 2019).

Biopathology of neurodegeneration

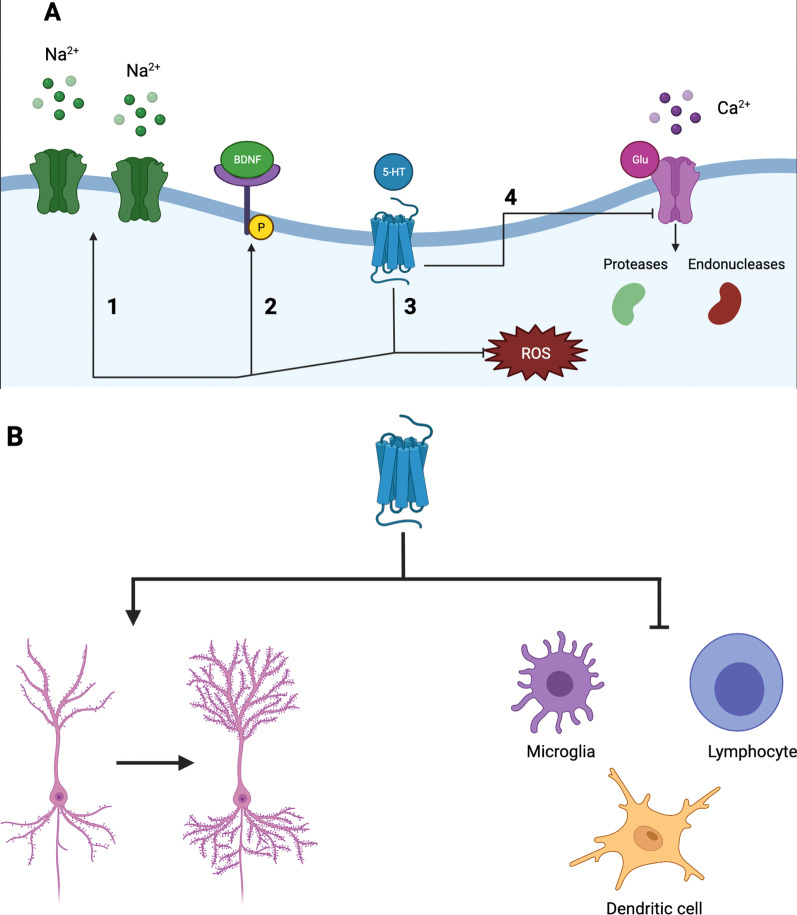

The biological mechanisms leading to neurodegeneration include many neuronal and glial molecular pathways that result in neuronal damage. Below, we briefly summarize the most common mechanisms involved in neurodegeneration and how they might associate with the known 5-HT7R effects (Fig. 2; Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Cellular and molecular effects of 5-HT7 receptors. Molecular effects of 5-HT7 activation. A When activated, 5-HT7 receptors modulate ion transmission through enhancing LTP and LTD (1); these receptors also increase the number of neurotrophins (especially BDNF) and the affinity of its receptor Trkb (2); through ERK and Akt, 5-HT7 decreases neuronal damage mediated by ROS (3); and reduces the excitotoxicity burden mediated by glutamate-NMDA-calcium. Cellular effects of 5-HT7 activation. B When stimulated by serotonin, 5-HT7 enhances dendritic sprouting and synaptogenesis, while regulating (often towards suppression) immune cells. LTD long-term depression, LTP long-term potentiation, NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor, ROS reactive oxygen species, Trkb tropomyosin receptor kinase B

Table 2.

Mechanisms of neuronal damage, and possible beneficial effects of 5-HT7 receptors agonism

| Neurodegeneration mechanism | 5-HT7 possible role | References |

|---|---|---|

| Excitotoxicity |

Activation of MAPK/ERK and PI3/Akt/GSK3b protects against glutamate-induced damage Decreased expression of NR2B and NR1 subunits of NMDA glutamate receptors Increased expression of superoxide dismutase and glutathione |

Jiang et al. (2000); Pi et al. (2004); Li et al. (2005) Vasefi et al. (2013a) Yuksel et al. (2019) |

| Oxidative stress |

No study evaluated effect in the CNS In a sepsis-induced lung injury, 5-HT7 receptor agonism decreased ROS burden 5-HT7 antagonism decreased oxidative burden in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis 5-HT7 activation enhances microsome stability towards oxidative metabolism (Lacivita et al., 2016a) ERK and Akt protect PC12 cells from oxidative damage |

Cadirci et al. (2013) Tawfik and Makary (2017) Lacivita et al. (2016a) Ong et al. (2016) |

| Apoptosis | 5-HT7 receptor agonism reduces apoptosis in the streptozotocin-induced AD model | Hashemi-Firouzi et al. (2017) |

| Long term depression/ potentiation impairment |

5-HT7 KO mice display LTP impairment 5-HT7 agonism reduces mGluR-dependent LTD |

Roberts et al. (2004) Costa et al. (2012) |

| Synaptic impairment |

5-HT7 agonism increases dendritic density and synaptogenesis in the cortical and striatal forebrain 5-HT7 agonism induces dendritic sprouting and neurite enlargement |

|

| Neurotrophin depletion |

5-HT7 agonism increases PDGF-β 5-HT7 agonism increases the expression and affinity of trk-B |

Vasefi et al. (2013b) Samarajeewa et al. (2014) |

Amyloid β-mediated neurodegeneration

Amyloid β (Aβ) is a key mediator of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), inducing damage through multiple pathways (Querfurth and Laferla 2018), some of which overlap with other mechanisms discussed below. Besides AD, Aβ may also play a role in diseases such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD), cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and cerebral amyloidosis (Miller-Thomas et al. 2016). Aβ is a critical source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species in AD, causing neuronal lipoperoxidation in neurons and thus, neurodegeneration (Bernal-Mondragón et al. 2013). Also, Aβ helps the formation of voltage-independent, cation channels in the lipid membranes, which could lead to excitotoxicity-mediated neurodegeneration (Arispe et al. 1993).

Chronically Aβ-stimulated microglia releases multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which induces pathological changes in the CNS (Heppner et al. 2015). Aβ-stimulated microglia increases neuronal damage and further accumulation of Aβ, an effect mediated by receptors for advanced glycation end products (Fang et al. 2010). Although not directly associated with neuronal death, Aβ impairs synaptic function and synaptogenesis and dysregulates neurotransmitter levels in the synaptic cleft, contributing to the symptoms in AD (Querfurth and Laferla 2018; Cai 2019; Ding et al. 2019).

5-HT7R agonism with LP-211 (a highly selective agonist) reverts neuronal damage and cognitive impairment induced by Aβ (Quintero-Villegas et al. 2019). Aβ induces neurotoxicity through several mechanisms including apoptosis, excitotoxicity, and oxidative stress (Querfurth and Laferla 2018; Bernal-Mondragón et al. 2013). In a streptozotocin-mediated neurodegeneration murine model for AD, the intracerebroventricular (ICV) treatment of AS-19 (a 5-HT7R selective agonist) reduced long-term potentiation (LTP) impairment and apoptosis in hippocampal (Hashemi-Firouzi et al. 2017).

The exact mechanism of 5-HT7R-mediated neuroprotection in Aβ-induced neurodegeneration is currently under investigation, an effect that is likely to be mediated through multiple mechanisms.

Excitotoxicity

This is an important cause of neuronal damage in neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, stroke, Huntington’s disease (HD), and Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Martire et al. 2013; Lai et al. 2014; Iovino et al. 2020). Persistent excitatory -mainly glutamatergic- stimuli lead to altered calcium homeostasis, resulting in oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, disturbances in protein turnover, inflammation, and caspase-mediated apoptosis (Binvignat and Olloquequi 2020). In vitro studies suggest that the MAPK/ERK and phosphatidylinositol-3/Akt/Glycogen synthase kinase 3b pathways are closely associated with protection against glutamate-induced damage (Jiang et al. 2000; Pi et al. 2004; Li et al. 2005); modulation of these kinases via 5-HT7R Gαs could have therapeutic implications. 5-HT7R activation leads to a decrease in the NR2B and NR1 subunits of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors, thus protecting against glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity (Vasefi et al. 2013a). Treatment with LP-44, a 5-HT7R-specific agonist, protects human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells against glutamate-mediated damage in an in-vitro model, also increasing superoxide dismutase and glutathione while decreasing TNF-α, and caspase-3 and -9 (Yuksel et al. 2019). Moreover, 5-HT7R modulate glutamate-NMDA activity in a time-dependent manner; while the acute activation of 5-HT7R by LP-12, a selective agonist of 5-HT7R, enhances NMDA activity, the chronic activation inhibits its activity (Vasefi et al. 2013b).

Oxidative stress

This can lead to membrane damage and neuronal death. (Bernal-Mondragón et al. 2013) Although, oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria produces ROS, reactive nitrogen species, carbon-centered radicals, and sulfur-centered radicals (Pero et al. 1990), and these by-products are considered necessary for neuronal function and development (Salim 2017); increase of their levels, beyond a physiological threshold, are considered deleterious. Multiple in vitro studies have demonstrated that high levels of ROS reduce long-term potentiation, synaptic signaling, and brain plasticity (Salim 2017; O’Dell et al. 1991; Stevens and Wang 1993). Moreover, oxidative stress damages macromolecules, mainly lipid-rich structures such as membranes, via lipoperoxidation (Salim 2017).

Although no study so far has evaluated the potential effect of 5-HT7R in oxidative stress damage in the CNS, a study evaluating sepsis-induced lung injury demonstrated that 5-HT7R agonism decreased ROS burden (Cadirci et al. 2013). In contrast, the antagonism of the 5-HT7R by SB-269970 decreased oxidative burden in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis (Tawfik and Makary 2017). Also, 5-HT7R activation by LP-44 enhances microsome stability towards oxidative metabolism (Lacivita et al. 2016a). As mentioned before, 5-HT7R regulates the activation of ERK and Akt, and these kinases have biological effects on oxidative stress injury protection in PC12 cells (Ong et al. 2016). Thus, 5-HT7R may have therapeutic implications in ROS-induced neurodegeneration, something that needs to be experimentally assessed.

Apoptosis

Neuronal cell death is a major pathological characteristic of every neurodegenerative disease, whether via apoptosis or necrosis. In AD, both phosphorylated tau protein and Aβ aggregates induce apoptosis in vitro studies, with contradictory effects in tissular studies. Other proteins, including α-Synuclein (in PD or Lewy body dementia), or mutant huntingtin protein (in HD) also induce neuronal cell death via multiple mechanisms, including apoptosis (Chi et al. 2018).

It is also important to note, that apoptosis is closely related to excitotoxicity and oxidative stress; thus, these pathological effects are somewhat overlapped (Yuksel et al. 2019; Loh et al. 2006; Nicholls et al. 2007). The 5-HT7R agonist AS-19 reduces apoptosis in the streptozotocin-induced AD model (Hashemi-Firouzi et al. 2017). While no other study has yet evaluated this effect in the CNS, methiothepin maleate (a non-specific 5-HT1/6/7R agonist) prevents monocyte activation via ERK 1/2 and Nuclear factor-κB (Soga et al. 2007).

Long-term potentiation and long-term depression (LTD) impairment

Impairment in LTP and LTD have been extensively described in many types of dementia, such as AD (Skaper et al. 2017), PD (Marinelli et al. 2017), and HD (Filippo et al. 2007), to name a few, with a strong correlation with the cognitive symptoms in each disease. LTP and LTD are crucial for memory formation, and impairment in these are associated with amnesic and psychiatric symptoms (Loprinzi 2020).

Like other CNS effects, the role of 5-HT7R in LTP is controversial. Because chronically stimulated neurons by 5-HT7R agonists show a reduction in the expression of NMDA glutamate receptors, 5-HT7R has been associated with a reduction in LTP (Kobe et al. 2012b), however, 5-HT7R knock-out mice also display an impairment in LTP, suggesting that 5-HT7R receptors at a baseline state are necessary for LTP (Roberts et al. 2004). Regarding LTD, 5-HT7R agonism by 8-OH-DPAT (a 5-HT1A/7R agonist) reduced mGluR mediated LTD (Costa et al. 2012). Finally, LP-211 induces LTD on the parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapse via Protein kinase C-MAPK pathway while impairing LTP, and pharmacological antagonism with SB-269970 decreases LTD (Lippiello et al. 2016).

Synaptogenesis and brain plasticity reduction

In many neurodegenerative diseases, reductions in synaptogenesis, brain plasticity, and dendritic sprouting are hallmarks of severity and progression (Querfurth and LaFerla 2010). So far, no treatment strategies have been shown to reverse that.

In vitro, activation of 5-HT7R in cortical and striatal forebrain neurons using LP-211 increases dendritic spine density and synaptogenesis, an effect that is abrogated by the genetical or pharmacological blockade of 5-HT7R (Speranza et al. 2013; Speranza et al. 2015; Speranza et al. 2017). 5-HT7R stimulation induces dendritic sprouting and neurite enlargement (Kvachnina et al. 2005; Rojas et al. 2014; Canese et al. 2015), an effect probably mediated by effectors of both, Gas and Ga12 signaling pathways (Volpicelli et al. 2014).

Neurotrophin depletion

Neurotrophins like BDNF and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-β are necessary for the development and correct function of the CNS. Depletion or altered signaling occurs in neurodegenerative diseases (Kashyap et al. 2018) AD, PD, HD, and FTD are associated with a reduction in the expression of BDNF and other neurotrophins, where the modulation of BDNF could have a potential therapeutic role (Palasz et al. 2020; Schulte-Herbrüggen et al. 2008; Alberch et al. 2002; Huey et al. 2020). Interestingly, 5-HT7R modulates both neurotrophins and their receptors. 5-HT7R activation by LP-12 leads to an increase in PDGF-β, with increased protection against glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity (Vasefi et al. 2013a). In addition, 5-HT7R agonism by LP-12 increases the expression and affinity of the tropomyosin-related kinase B receptor, one of the receptors for BDNF (Samarajeewa et al. 2014).

Immune-mediated damage

The specific role of 5-HT7R as neuro-immune mediators is still debated. 5-HT7R is expressed broadly by different immune cells, including monocytes, lymphocytes, and dendritic cells, but its anti-inflammatory potential has been shown in some but not all studies (Quintero-Villegas and Valdés-Ferrer 2019).

Potential disease-specific role of 5-HT7R in neuropsychiatric illness

Neuronal hyperexcitability and seizures

Epilepsy-induced neuronal damage shares pathophysiological neurodegenerative features with dementias and other CNS diseases, such as increased inflammation and excitotoxicity (Nikiforuk 2015). Epilepsy is prevalent in sufferers of CNS diseases, including AD, PD, or HD, and, when present, indicates a higher burden of neurodegeneration (Cano et al. 2021).

5-HT7R manipulation has shown controversial results in pre-clinical studies of epilepsy. Non-specific pharmacological blockade of 5-HT7R reduces the prevalence of audiogenic seizures in a DBA/2J rat model (Bourson et al. 1997).

Additionally, SB-258719, an antagonist of 5-HT7R showed a benefit in reducing spontaneous epileptic activity in a WAG/Rij rat model of absence seizures (Graf et al. 2004). Finally, in a pilocarpine-induced rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy, AS-19 increased epileptic activity, whereas SB-269970, an antagonist of 5-HT7R reduced seizure activity. Interestingly, the expression of 5-HT7R was higher in the epilepsy group, compared to the control group (Yang et al. 2012). However, in a pilocarpine-induced model of epilepsy, the density of 5-HT7R decreased in the hippocampus, especially in the dentate gyrus (Núñez-Ochoa et al. 2021). Hence, the role of 5-HT7R in epilepsy is still unclear but avidly explored. The controversial finding may represent that 5-HT7R plays different roles in different models of epilepsy. Evaluation of 5-HT7R tissue expression in specimens obtained from patients undergoing surgical excision of epileptic foci may help to clarify this controversy.

Mood disorders

The relationship between mood disorders and cognitive disorders is a topic of continuous research. The prevalence of depression and anxiety is higher among patients with dementia, and patients with depression have a higher prevalence of dementia (Lyketsos et al. 2002). Of therapeutic relevance, even mild levels of depression can impact substantially the functionality and quality of life of patients with dementia. Thus, treating these symptoms may be crucial in the management of dementia (Gutzmann and Qazi 2015).

In a rat model of stress using forced swim and tail suspension, pharmacological and genetic blockade of 5-HT7R reduced depressive symptoms and improved REM sleep (Hedlund et al. 2005). 5-HT7R KO mice show improved mobility in the Porsolt swim test; however, the pharmacological blockade by SB-258719 only had the same results when rats were tested in the dark (Guscott et al. 2005). Similar results were observed with SB-269970 in depression and anxiety, with an effect similar to the one observed with imipramine (Wesołowska et al. 2006). In experimental depression, pharmacological blockade of 5-HT7R seems to have a rapid effect in reducing depressive symptoms (Mnie-Filali et al. 2011). Altogether, while more data is needed before moving to the clinical trial setting, these experimental models suggest that 5-HT7R may be a druggable target for depression.

The calcium-binding protein S100B interacts with 5-HT7R and negatively regulates inducible cAMP accumulation; its overexpression in transgenic mice is associated with depressive-like symptoms, which are reversed by the administration of SB269970 (Stroth and Svenningsson 2015).

The non-specific blockade of 5-HT7R with HBK-15 (5-HT7R, 5-HT1AR, and 5-HT3R antagonist) (Pytka et al. 2018), aryl sulfonamide derivatives of dihydro benzofuran oxy)ethyl piperidines (a2 and 5-HT7R antagonist) (Canale et al. 2021), and lurasidone (5-HT2AR and 5-HT7R antagonist) (Woo et al. 2013), to name a few, have similar effects regarding depression and anxiety.

The contradictory memory effect of 5-HT7R

Evidence about the effect of 5-HT7R on learning and memory is still contradictory. Systemic administration of LP-211 and AS-19 revert scopolamine-induced amnesia and enhanced auto-shaping training learning respectively in rats; whereas pharmacologic blockade with SB-269970 has the opposite effect (Perez-García and Meneses 2005). Accordingly, LP-211 administrated intraperitoneally improves long-term memory, with conditioned responses up to 80%, compared to 20–30% in the control groups, with no effect on short-term memory, and reverts scopolamine-induced memory impairment, something associated with increased cAMP levels (Meneses et al. 2015). Moreover, 5-HT7R agonism appears to revert the memory impairment mediated by 5-HT1AR, based on the fact that the co-administration of SB-269970 and 8-OH-DPAT (a 5-HT7R/5-HT1AR agonist) caused greater performance impairment in contextual learning than the administration of 8-OH-DPAT alone (Eriksson et al. 2008).

On the other hand, SB-269970 improved reference memory in a radial arm maze task (Gasbarri et al. 2008). In agreement, the administration of SB-656104-A (a 5-HT7R-specific antagonist) reverses dizocilpine-induced memory impairment induced, with significant differences in thigmotaxic swimming in the Morris water maze test (Horisawa et al. 2011). We have observed that intracerebroventricular injection of LP-211 reverts memory impairment induced by Aβ without a discernible effect on healthy rats (Quintero-Villegas et al. 2019). The answer to this paradox is inconclusive with the current evidence (Meneses 2014; Stiedl et al. 2015; Zareifopoulos and Papatheodoropoulos 2016), suggesting a memory type-specific role of 5-HT7R.

Lack of clinical trial-derived data

No clinical trials with 5-HT7R-specific modulation for neurodegenerative studies have been performed. However, the potential effect of non-specific serotonin activation in neurodegenerative diseases is a highly studied topic and the outflow of human data may start shortly. Interestingly, lurasidone, a 5-HT7R antagonist, with an effect on other serotonin receptors and D2 dopamine receptor (Meltzer et al. 2020), has been FDA approved for the treatment of schizophrenia (Okubo et al. 2021).

Conclusion

At this point, no 5-HT7R-specific drugs have been evaluated for neurodegenerative diseases, and few studies have experimentally evaluated their potential therapeutic effects. Hence, elucidating the effect of 5-HT7R in health and (predominantly neurodegenerative) diseases may have vast translational and therapeutic implications. 5-HT7R agonists may be neuroprotective by acting at multiple levels, including the reduction of excitotoxicity and oxidative stress, synaptic remodeling, regulation of neurotrophic factors, or immunomodulation, to name a few. The need for more studies, both experimental and clinical, before reaching conclusions about a therapeutic role for this serotonin receptor cannot be overemphasized.

Acknowledgements

The figures on this manuscript were created with biorender.com.

Abbreviations

- 5-HT

5-Hydroxytryptamine/serotonin

- 5-HT1AR

5-HT1A receptor

- 5-HT7R

5-HT7 receptor

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

Amyloid β

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- Cdc42

Cell division control protein 42

- CNS

Central nervous system

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FTD

Frontotemporal dementia

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- ICV

Intracerebroventricular

- IL

Interleukin

- LTD

Long-term depression

- LTP

Long-term potentiation

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PDGF

Platelet-derived growth factor

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- Trkb

Tropomyosin-related kinase B

Author contributions

Both SIVF and AQV contributed in an equal manner to the making of this article. Both the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author's information

AQV: Medical resident and Assistant Investigator, Laboratory of Neurobiology of Systemic Illness, Department of Neurology Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, Mexico City. SIVF: Head and Principal Investigator, Laboratory of Neurobiology of Systemic Illness, Department of Neurology Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, Mexico City, and Institute of Bioelectronic Medicine, Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY.

Funding

This manuscript was supported by Grants 289788 and A1-S-18342 from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT), Mexico (to SIVF).

Availability of data and materials

All data were extracted from the PubMed database using the MeSH established in the “Methods” section.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All the authors gave their approval for submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest while making this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Albayrak A, et al. Inflammation and peripheral 5-HT7 receptors: the role of 5-HT7 receptors in carrageenan induced inflammation in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;715:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberch J, Pérez-Navarro E, Canals JM. Neuroprotection by neurotrophins and GDNF family members in the excitotoxic model of Huntington’s disease. Brain Res Bull. 2002;57:817–822. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00775-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arispe N, Pollard HB, Rojas E. Giant multilevel cation channels formed by Alzheimer disease amyloid β- protein [AβP-(1–40)] in bilayer membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10573–10577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LP, et al. Stimulation of type 1 and type 8 Ca2+/calmodulin-sensitive adenylyl cyclases by the G(s)-coupled 5-hydroxytryptamine subtype 5-HT(7A) receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17469–17476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard JA et al. Cloning of a novel human serotonin receptor (5-HT7) positively linked to adenylate cyclase. 1993;268: 23422–23426. [PubMed]

- Bernal-Mondragón C, Rivas-Arancibia S, Kendrick KM, Guevara-Guzmán R. Estradiol prevents olfactory dysfunction induced by A-β 25–35 injection in hippocampus. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Binvignat O, Olloquequi J. Excitotoxicity as a target against neurodegenerative processes. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26:1251–1262. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666200113162641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourson A, et al. Correlation between 5-HT7 receptor affinity and protection against sound-induced seizures in DBA/2J mice. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1997;356:820–826. doi: 10.1007/PL00005123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenchat A, Ejarque M, Zamanillo D, Vela JM, Romero L. Potentiation of morphine analgesia by adjuvant activation of 5-HT7 receptors. J Pharmacol Sci. 2011;116:388–391. doi: 10.1254/jphs.11039SC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadirci E, et al. Peripheral 5-HT7 receptors as a new target for prevention of lung injury and mortality in septic rats. Immunobiology. 2013;218:1271–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M et al. Spinosin attenuates Alzheimer’ s disease-associated synaptic dysfunction via regulation of plasmin activity. 2019;6: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Canale V, et al. Design, sustainable synthesis and biological evaluation of a novel dual α2A/5-HT7 receptor antagonist with antidepressant-like properties. Molecules. 2021;26:828. doi: 10.3390/molecules26040828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canese R, et al. Persistent modification of forebrain networks and metabolism in rats following adolescent exposure to a 5-HT7 receptor agonist. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:75–89. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3639-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, et al. Epilepsy in neurodegenerative diseases: related drugs and molecular pathways. Pharmaceuticals (basel) 2021;14:1057. doi: 10.3390/ph14101057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassaday HJ, Thur KE. Intraperitoneal 8-OH-DPAT reduces competition from contextual but not discrete conditioning cues. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2019;187:172797. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2019.172797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang-Chien CC, Hsin LW, Su MJ. Activation of serotonin 5-HT7 receptor induces coronary flow increase in isolated rat heart. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;748:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H, Chang H-Y, Sang T-K. Neuronal cell death mechanisms in major neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3082. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciranna L, Catania MV. 5-HT7 receptors as modulators of neuronal excitability, synaptic transmission and plasticity: physiological role and possible implications in autism spectrum disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:1–17. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa L, et al. Activation of 5-HT7 serotonin receptors reverses metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated synaptic plasticity in wild-type and fmr1 knockout mice, a model of fragile X syndrome. Biol Psychiat. 2012;72:924–933. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa L, et al. Activation of serotonin 5-HT7 receptors modulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity by stimulation of adenylate cyclases and rescues learning and behavior in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirkaya K, et al. Selective 5-HT7 receptor agonists LP 44 and LP 211 elicit an analgesic effect on formalin-induced orofacial pain in mice. J Appl Oral Sci. 2016;24:218–222. doi: 10.1590/1678-775720150563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Filippo M, Tozzi A, Picconi B, Ghiglieri V, Calabresi P. Plastic abnormalities in experimental Huntington’s disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, et al. Amyloid beta oligomers target to extracellular and intracellular neuronal synaptic proteins in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson TM, Golkar A, Ekström JC, Svenningsson P, Ögren SO. 5-HT7 receptor stimulation by 8-OH-DPAT counteracts the impairing effect of 5-HT1A receptor stimulation on contextual learning in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;596:107–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errico M, Crozier RA, Plummer MR, Cowen DS. 5-HT7 receptors activate the mitogen activated protein kinase extracellular signal related kinase in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 2001;102:361–367. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang, et al. RAGE-dependent signaling in microglia contributes to neuroinflammation, Aβ accumulation, and impaired learning/memory in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2010;24:1043–1055. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-139634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields DP, Springborn SR, Mitchell GS. Spinal 5-HT7 receptors induce phrenic motor facilitation via EPAC-mTORC1 signaling. J Neurophysiol. 2015;114:2015–2022. doi: 10.1152/jn.00374.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasbarri A, Cifariello A, Pompili A, Meneses A. Effect of 5-HT 7 antagonist SB-269970 in the modulation of working and reference memory in the rat. 2008; 195: 164–170. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gellynck E, et al. The serotonin 5-HT7 receptors: two decades of research. Exp Brain Res. 2013;230:555–568. doi: 10.1007/s00221-013-3694-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godínez-Chaparro B, López-Santillán FJ, Orduña P, Granados-Soto V. Secondary mechanical allodynia and hyperalgesia depend on descending facilitation mediated by spinal 5-HT4, 5-HT6 and 5-HT7 receptors. Neuroscience. 2012;222:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf M, Jakus R, Kantor S, Levay G, Bagdy G. Selective 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 antagonists decrease epileptic activity in the WAG/Rij rat model of absence epilepsy. Neurosci Lett. 2004;359:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guscott M, et al. Genetic knockout and pharmacological blockade studies of the 5-HT7 receptor suggest therapeutic potential in depression. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:492–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guseva D, Wirth A, Ponimaskin E. Cellular mechanisms of the 5-HT 7 receptor-mediated signaling. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutzmann H, Qazi A. Depression associated with dementia. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;48:305–311. doi: 10.1007/s00391-015-0898-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon J, Hoyer D. Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2008;195:198–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart MJ et al. Exchange activity of p115 RhoGEF by Ga. 1998;280: 0–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hashemi-Firouzi N, Komaki A, Soleimani Asl S, Shahidi S. The effects of the 5-HT7 receptor on hippocampal long-term potentiation and apoptosis in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Bull. 2017;135:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund PB, Huitron-Resendiz S, Henriksen SJ, Sutcliffe JG. 5-HT7 receptor inhibition and inactivation induce antidepressantlike behavior and sleep pattern. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidmann DE, Metcalf MA, Kohen R, Hamblin MW. Four 5-hydroxytryptamine7 (5-HT7) receptor isoforms in human and rat produced by alternative splicing: species differences due to altered intron–exon organization. J Neurochem. 1997;68:1372–1381. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68041372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner FL, Ransohoff RM, Becher B. Immune attack: the role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:358–372. doi: 10.1038/nrn3880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horisawa T, et al. The effects of selective antagonists of serotonin 5-HT7 and 5-HT1A receptors on MK-801-induced impairment of learning and memory in the passive avoidance and Morris water maze tests in rats: mechanistic implications for the beneficial effects of the novel. Behav Brain Res. 2011;220:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey ED, et al. Effect of functional BDNF and COMT polymorphisms on symptoms and regional brain volume in frontotemporal dementia and corticobasal syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;32:362–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19100211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hüll M, Berger M, Heneka M. Disease-modifying therapies in Alzheimer’s disease: how far have we come? Drugs. 2006;66:2075–2093. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iovino L, Tremblay ME, Civiero L. Glutamate-induced excitotoxicity in Parkinson’s disease: the role of glial cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2020;144:151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Gu Z, Zhang G, Jing G. Diphosphorylation and involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2) in glutamate-induced apoptotic-like death in cultured rat cortical neurons. Brain Res. 2000;857:71–77. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)02364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Farley NN, Kertesy SB, Dubyak GR, Cowen DS. Enhanced activation of Akt and extracellular-regulated kinase pathways by simultaneous occupancy of Gq-coupled 5-HT2A receptors and Gs-coupled 5-HT7A receptors in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 2005;92:72–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap MP, Roberts C, Waseem M, Tyagi P. Drug targets in neurotrophin signaling in the central and peripheral nervous system. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:6939–6955. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-0885-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe F, et al. 5-HT7R/G12 signaling regulates neuronal morphology and function in an age-dependent manner. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2915–2930. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2765-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe F, et al. 5-HT 7R/G 12 signaling regulates neuronal morphology and function in an age-dependent manner. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2915–2930. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2765-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusek M, et al. 5-HT7 receptors enhance inhibitory synaptic input to principal neurons in the mouse basal amygdala. Neuropharmacology. 2021;198:108779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvachnina E, et al. 5-HT7 receptor is coupled to Gα subunits of heterotrimeric G12-protein to regulate gene transcription and neuronal morphology. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7821–7830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1790-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacivita E, et al. Structural modifications of the serotonin 5-HT7 receptor agonist N-(4-cyanophenylmethyl)-4-(2-biphenyl)-1-piperazinehexanamide (LP-211) to improve in vitro microsomal stability: a case study. Eur J Med Chem. 2016;120:363. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai TW, Zhang S, Wang YT. Excitotoxicity and stroke: identifying novel targets for neuroprotection. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;115:157–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalut J, Karila D, Dallemagne P, Rochais C. Modulating 5-HT4 and 5-HT6 receptors in Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Future Med Chem. 2017;9:781–795. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2017-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, et al. Novel dimeric acetylcholinesterase inhibitor bis(7)-tacrine, but not donepezil, prevents glutamate-induced neuronal apoptosis by blocking N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18179–18188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippiello P, et al. The 5-HT7 receptor triggers cerebellar long-term synaptic depression via PKC-MAPK. Neuropharmacology. 2016;101:426–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, et al. Effects of 5-HT7 receptors on circadian rhythm of mice anesthetized with isoflurane. Chronobiol Int. 2021;38:38–45. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1832111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh KP, Huang SH, Silva RD, Tan BKH, Zhu YZ. Oxidative stress: apoptosis in neuronal injury. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3:327–337. doi: 10.2174/156720506778249515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loprinzi PD. Effects of exercise on long-term potentiation in neuropsychiatric disorders. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1228:439–451. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-1792-1_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovenberg TW et al. A novel adenylyl cyclase-activating serotonin receptor (5-HT7) implicated in the regulation of mammalian circadian rhythms. 1993;11: 449–458. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lyketsos CG, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288:1475–1483. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahé C, et al. Serotonin 5-HT7 receptors coupled to induction of interleukin-6 in human microglial MC-3 cells. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin P, Dityatev A. 5-HT7 receptor shapes spinogenesis in cortical and striatal neurons: an editorial highlight for ‘Serotonin 5-HT7 receptor increases the density of dendritic spines and facilitates synaptogenesis in forebrain neurons’. J Neurochem. 2017;141:644–646. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli L, Quartarone A, Hallett M, Frazzitta G, Ghilardi MF. The many facets of motor learning and their relevance for Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neurophysiol off J Int Fed Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128:1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2017.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Cora FJ, Pazos A. Autoradiographic distribution of 5-HT 7 receptors in the human brain using [3H]mesulergine: comparison to other mammalian species. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:92–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire A, et al. BDNF prevents NMDA-induced toxicity in models of Huntington’s disease: the effects are genotype specific and adenosine A2A receptor is involved. J Neurochem. 2013;125:225–235. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaid J, Mustaly-Kalimi S, Stutzmann GE. Ca2+ dyshomeostasis disrupts neuronal and synaptic function in Alzheimer’s disease. Cells. 2020;9(12):1–25. doi: 10.3390/cells9122655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Share DB, Jayathilake K, Salomon RM, Lee MA. Lurasidone improves psychopathology and cognition in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40:240–249. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses A. Memory formation and memory alterations: 5-HT6and 5-HT7receptors, novel alternative. Rev Neurosci. 2014;25:325–356. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2014-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses A, et al. 5-HT7 receptor activation: procognitive and antiamnesic effects. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:595–603. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Thomas MM, et al. Multimodality review of amyloid-related diseases of the central nervous system. Radiographics. 2016;36:1147–1163. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnie-Filali O, et al. Pharmacological blockade of 5-HT7 receptors as a putative fast acting antidepressant strategy. Neuropsychopharmacol off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;36:1275–1288. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti JM, Leopoldo M, Jantos H. Systemic administration and local microinjection into the central nervous system of the 5-HT(7) receptor agonist LP-211 modify the sleep-wake cycle in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2014;259:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls DG, Johnson-Cadwell L, Vesce S, Jekabsons M, Yadava N. Bioenergetics of mitochondria in cultured neurons and their role in glutamate excitotoxicity. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:3206–3212. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforuk A. Targeting the serotonin 5-HT7 receptor in the search for treatments for CNS disorders: Rationale and progress to date. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:265–275. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0236-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi-Javidan A, et al. Effect of 5-HT7 receptor agonist, LP-211, on micturition following spinal cord injury in male rats. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:2525–2533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Ochoa MA, Chiprés-Tinajero GA, Medina-Ceja L. Evaluation of the hippocampal immunoreactivity of the serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2 and 5-HT7 receptors in a pilocarpine temporal lobe epilepsy rat model with fast ripples. NeuroReport. 2021;32:306–311. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell TJ, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER, Arancio O. Tests of the roles of two diffusible substances in long-term potentiation: evidence for nitric oxide as a possible early retrograde messenger. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11285–11289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odland AU, Jessen L, Fitzpatrick CM, Andreasen JT. 8-OH-DPAT induces compulsive-like deficit in spontaneous alternation behavior: reversal by MDMA but not citalopram. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2019;10:3094–3100. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Matsumoto R, Yamamoto Y, Fukuyama K. Effects of subchronic administrations of vortioxetine, lurasidone, and escitalopram on thalamocortical glutamatergic transmission associated with serotonin 5-HT7 receptor. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:1351. doi: 10.3390/ijms22031351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo R, Hasegawa T, Fukuyama K, Shiroyama T, Okada M. Current limitations and candidate potential of 5-HT7 receptor antagonism in psychiatric pharmacotherapy. Front Psych. 2021;12:623684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.623684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong Q, et al. The timing of Raf/ERK and AKT activation in protecting PC12 cells against oxidative stress. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0153487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palasz E, et al. BDNF as a promising therapeutic agent in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1170. doi: 10.3390/ijms21031170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-García GS, Meneses A. Effects of the potential 5-HT7 receptor agonist AS 19 in an autoshaping learning task. Behav Brain Res. 2005;163:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pero RW, Roush GC, Markowitz MM, Miller DG. Oxidative stress, DNA repair, and cancer susceptibility. Cancer Detect Prev. 1990;14:555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi R, et al. Minocycline prevents glutamate-induced apoptosis of cerebellar granule neurons by differential regulation of p38 and Akt pathways. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1219–1230. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouzet B. SB-258741: a 5-HT7 receptor antagonist of potential clinical interest. CNS Drug Rev. 2002;8:90–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2002.tb00217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad S, Ponimaskin E, Zeug A. Serotonin receptor oligomerization regulates cAMP-based signaling. J Cell Sci. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pytka K, et al. Single administration of HBK-15-a triple 5-HT(1A), 5-HT(7), and 5-HT(3) receptor antagonist-reverses depressive-like behaviors in mouse model of depression induced by corticosterone. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:3931–3945. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0605-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querfurth HW, Laferla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero-Villegas A, Valdés-Ferrer SI. Role of 5-HT7 receptors in the immune system in health and disease. Mol Med. 2019;26:4–11. doi: 10.1186/s10020-019-0126-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero-Villegas A, Manzo-Alvarez HS, Valenzuela Almada MO, Bernal-Mondragón C, Guevara-Guzmán R. Procognitive and neuroprotector effect of 5-HT7 agonists in an animal model by intracerebroventricular amyloid-B injection. SciFed J Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2019;2019(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Renner U, et al. Heterodimerization of serotonin receptors 5-HT 1A and 5-HT 7 differentially regulates receptor signalling and trafficking. J Cell Sci. 2005;2:2486–2499. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, et al. Mice lacking 5-HT7 receptors show specific impairments in contextual learning. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1913–1922. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas PS, Neira D, Muñoz M, Lavandero S, Fiedler JL. Serotonin (5-HT) regulates neurite outgrowth through 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 receptors in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2014;92:1000–1009. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruat M, Traiffort E, Leurs ROB, Tardivel-lacombe J, Diazt J. Molecular cloning, characterization, and localization of a high-affinity serotonin receptor (5-HT7) activating cAMP formation. 1993;90: 8547–8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Salim S. Oxidative stress and the central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;360:201–205. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.237503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarajeewa A, et al. 5-HT7 receptor activation promotes an increase in TrkB receptor expression and phosphorylation. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger GJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine and the gastrointestinal tract: Where next? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:465–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Herbrüggen O, Jockers-Scherübl MC, Hellweg R. Neurotrophins: from pathophysiology to treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:38–44. doi: 10.2174/156720508783884620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M, Nishida A, Zensho H, Miyata M, Yamawaki S. Agonist-induced desensitization of adenylyl cyclase activity mediated by 5-hydroxytryptamine7 receptors in rat frontocortical astrocytes. Brain Res. 1998;784:57–62. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)01185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaper SD, Facci L, Zusso M, Giusti P. Synaptic plasticity, dementia and Alzheimer disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2017;16:220–233. doi: 10.2174/1871527316666170113120853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Toohey N, Knight JA, Klein MT, Teitler M. Risperidone-induced inactivation and clozapine-induced reactivation of rat cortical astrocyte 5-hydroxytryptamine 7 receptors : evidence for in situ g protein-coupled receptor homodimer protomer cross-talk. 2011; 79:318–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Soga F, Katoh N, Inoue T, Kishimoto S. Serotonin activates human monocytes and prevents apoptosis. J Investig Dermatol. 2007;127:1947–1955. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speranza L, et al. The serotonin receptor 7 promotes neurite outgrowth via ERK and Cdk5 signaling pathways. Neuropharmacology. 2013;67:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speranza L, et al. Activation of 5-HT7 receptor stimulates neurite elongation through mTOR, Cdc42 and actin filaments dynamics. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speranza L, et al. Serotonin 5-HT7 receptor increases the density of dendritic spines and facilitates synaptogenesis in forebrain neurons. J Neurochem. 2017;141:647–661. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CF, Wang Y. Reversal of long-term potentiation by inhibitors of haem oxygenase. Nature. 1993;364:147–149. doi: 10.1038/364147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiedl O, Pappa E, Konradsson-Geuken Å, Ögren SO. The role of the serotonin receptor subtypes 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 and its interaction in emotional learning and memory. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:162. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroth N, Svenningsson P. S100B interacts with the serotonin 5-HT7 receptor to regulate a depressive-like behavior. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol J Eur Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:2372–2380. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik MK, Makary S. 5-HT7 receptor antagonism (SB-269970) attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats via downregulating oxidative burden and inflammatory cascades and ameliorating collagen deposition: Comparison to terguride. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;814:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, Hagan J. 5-HT7 receptors. Curr Drug Target-CNS Neurol Disord. 2004;3:81–90. doi: 10.2174/1568007043482633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasefi MS, Kruk JS, Heikkila JJ, Beazely MA. 5-Hydroxytryptamine type 7 receptor neuroprotection against NMDA-induced excitotoxicity is PDGFβ receptor dependent. J Neurochem. 2013;125:26–36. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasefi MS, et al. Acute 5-HT7 receptor activation increases NMDA-evoked currents and differentially alters NMDA receptor subunit phosphorylation and trafficking in hippocampal neurons. Mol Brain. 2013;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli F, Speranza L, di Porzio U, Crispino M, Perrone-Capano C. The serotonin receptor 7 and the structural plasticity of brain circuits. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:318. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesołowska A, Nikiforuk A, Stachowicz K. Potential anxiolytic and antidepressant effects of the selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist SB 269970 after intrahippocampal administration to rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;553:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo YS, Wang HR, Bahk W-M. Lurasidone as a potential therapy for bipolar disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1521–1529. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S51910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Liu X, Yin Y, Sun S, Deng X. Involvement of 5-HT7 receptors in the pathogenesis of temporal lobe epilepsy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;685:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuksel TN, et al. Protective effect of 5-HT7 receptor activation against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells via antioxidative and antiapoptotic pathways. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2019;72:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zareifopoulos N, Papatheodoropoulos C. Effects of 5-HT-7 receptor ligands on memory and cognition. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016;136:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Zhang R, Zhang S, Wu J, Sun X. Activation of 5-HT1A receptors promotes retinal ganglion cell function by inhibiting the cAMP-PKA pathway to modulate presynaptic GABA release in Chronic Glaucoma. J Neurosci. 2019;39:1484–1504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1685-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data were extracted from the PubMed database using the MeSH established in the “Methods” section.