Abstract

Twenty different Pseudomonas strains utilizing m-toluate were isolated from oil-contaminated soil samples near Minsk, Belarus. Seventeen of these isolates carried plasmids ranging in size from 78 to about 200 kb (assigned pSVS plasmids) and encoding the meta cleavage pathway for toluene metabolism. Most plasmids were conjugative but of unknown incompatibility groups, except for one, which belonged to the IncP9 group. The organization of the genes for toluene catabolism was determined by restriction analysis and hybridization with xyl gene probes of pWW0. The majority of the plasmids carried xyl-type genes highly homologous to those of pWW53 and organized in a similar manner (M. T. Gallegos, P. A. Williams, and J. L. Ramos, J. Bacteriol. 179:5024–5029, 1997), with two distinguishable meta pathway operons, one upper pathway operon, and three xylS-homologous regions. All of these plasmids also possessed large areas of homologous DNA outside the catabolic genes, suggesting a common ancestry. Two other pSVS plasmids carried only one meta pathway operon, one upper pathway operon, and one copy each of xylS and xylR. The backbones of these two plasmids differed greatly from those of the others. Whereas these parts of the plasmids, carrying the xyl genes, were mostly conserved between plasmids of each group, the noncatabolic parts had undergone intensive DNA rearrangements. DNA sequencing of specific regions near and within the xylTE and xylA genes of the pSVS plasmids confirmed the strong homologies to the xyl genes of pWW53 and pWW0. However, several recombinations were discovered within the upper pathway operons of the pSVS plasmids and pWW0. The main genetic mechanisms which are thought to have resulted in the present-day configuration of the xyl operons are discussed in light of the diversity analysis carried out on the pSVS plasmids.

The pathway for the catabolism of toluene, m-xylene, and p-xylene via aromatic ring meta cleavage is often encoded on plasmids, referred to as TOL plasmids (1, 4 [and references within], 8, 13, 26, 28, 29, 31, 37, 54, 55, 57, 58). TOL plasmids have mostly been found in representatives of the genus Pseudomonas, with one exception, Alcaligenes eutrophus strain 345(pRA1000) (21), isolated from a variety of geographical locations. The plasmids differ in size, restriction pattern, compatibility, and conjugation ability, although the xyl genes for toluene and xylene catabolism are mostly organized in the meta pathway operon (xylXYZLTEGFJQKIH) and an upper pathway operon [xyl(UW)CMAB(N)]. Expression of the xyl genes is under the control of two regulatory genes, xylS and xylR (15, 41). There is a high level of DNA homology among xyl genes on different TOL plasmids, and the gene order within either meta or upper pathway operons is invariable. However, the relative positions of both the operons and the regulatory genes vary (1, 12, 15, 47). In some TOL plasmids, more than one copy of the regulatory genes and/or xyl operons has been found (3, 8, 37, 38, 53).

A number of TOL plasmids have been shown to recombine DNA with other plasmids, such as antibiotic resistance (R) plasmids (23, 26, 37, 47) and a plasmid for salicylate degradation (14), and with the host chromosome (25, 33, 48). Furthermore, on pWW0 the xyl genes are located within a 56-kb transposon (Tn4651), which itself is part of a larger, 73-kb transposon (Tn4653) (51). However, for plasmids pWW53, pDK1, and pWW15, the precise mechanism for xyl gene translocations is not yet established.

Knowledge about the evolution of the xyl genes is mainly based on pWW0. From several studies, it was concluded that (i) the meta pathway operon originated as a fusion product of two independently evolved gene blocks, xylXYZL and xylTEGFJQKIH (19); (ii) the upper and meta pathway operons evolved separately (17); and (iii) the meta pathway operon, in the strict sense (i.e., xylT through xylH), probably resulted from recombination itself (6, 19). However, due to limited sequence information on DNA regions flanking the xyl genes in different TOL plasmids, no solid conclusions can be drawn about the evolution of the xyl genes and the mechanisms leading to their distribution and variation on different plasmid replicons.

The objective of this study was to compare a variety of TOL plasmids in order to establish trends in their evolution and the underlying evolutionary mechanisms. For this purpose, we isolated a number of m-toluate-degrading strains from oil-contaminated sites in Belarus, located the genes for toluene catabolism on plasmids present in those strains, and compared their organization and DNA sequences. Relationships between plasmid replicons and between xyl gene clusters on the different TOL plasmids were established, and evolutionary mechanisms are proposed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and growth conditions.

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and M9 minimal medium (MM) (46) were routinely used. Sodium benzoate, m-toluate, or salicylate was added to MM to a final concentration of 5.0 mM; phenol was used at 2.5 mM, and glucose was used at 20 mM. Toluene and xylene were supplied through the vapor phase to MM agar plates incubated in gas-tight glass jars. When required, the medium was supplemented with ampicillin at 100 μg/ml for Escherichia coli and 500 μg/ml for Pseudomonas; kanamycin at 50 μg/ml; gentamicin at 50 μg/ml; rifampin at 50 μg/ml; streptomycin at 50 μg/ml; tetracycline at 30 μg/ml; nalidixic acid at 50 μg/ml; 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (X-Gal) at 0.004% (wt/vol); or l-histidine at 40 μg/ml. Strains of Pseudomonas were grown at 30°C, and those of E. coli were grown at 37°C.

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Twenty Pseudomonas sp. strains described in this study were isolated from 13 soil samples collected from distant locations (from 3 to 100 km apart) near Minsk (Belarus). All but two sites were near oil transportation routes and have a history of major contamination by oil products (Table 1). Samples were processed under conditions preventing bacterial cross-contamination. Initial enrichments for toluene- and xylene-degrading microorganisms were made in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 30 ml of MM with m-toluate; the flasks were inoculated with 10 g of soil sample and incubated for 24 h at 27°C and 150 rpm on a rotary shaker. The resulting cultures were serially diluted and plated on MM agar plates with m-toluate (TMA). Colonies visible after 48 h were purified by streaking on TMA and were tested for their ability to grow on benzoate, toluene, m-xylene, phenol, or salicylate in liquid medium and on agar plates. Growth was judged by comparison with that on MM without a carbon source. The activity of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase (C2,3O) was tested by using the catechol spray test (12). Pure cultures were stored in LB agar under paraffin oil at +4°C and frozen in MM with m-toluate and 20% glycerol at −80°C. The isolates were identified on the basis of morphological and cultural characteristics according to Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (30) and by sequencing of a 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) fragment amplified by the PCR.

TABLE 1.

Pseudomonas strains isolated in the present study

| Pseudomonas strain | Relevant characteristicsa | Soil sample |

|---|---|---|

| SV1 | Apr Tcr Nalr Cmr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries a 2.3-kb cryptic plasmid | Layer of solidified oil on the surface of a long-distance oil transportation tank; railway station Minsk-South |

| SV2 | Apr Tcr Cmr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+ | Same as SV1 |

| SV3 | Apr Tcr Cmr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries ∼190-kb plasmid pSVS3 | Sandy soil contaminated with heating oil; southwestern part of Minsk |

| SV4 | Tcr Nalr Cmr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries ∼200-kb plasmid pSVS4 | Same as SV3 |

| SV5 | Tcr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries ∼150-kb plasmid pSVS5 and a 2.9-kb cryptic plasmid | Railway bed soil contaminated with mixture of lubricants, diesel fuel, and phenol; town of Smorgon, 100 km northwest of Minsk |

| SV6 | Tcr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+ Sal+; carries 140-kb plasmid pSVS6 and 10- and 80-kb cryptic plasmids | Grass bed bulk soil contaminated with diesel fuel; central part of Minsk |

| SV9 | Apr Tcr Cmr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries 107-kb plasmid pSVS9 | Railway bed soil contaminated with mixture of lubricants, diesel fuel, and phenol; central part of Minsk |

| SV10 | Apr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries 105-kb plasmid pSVS10 | Same as SV9 |

| SV11 | Tcr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries 130-kb plasmid pSVS11 | Railway bed soil contaminated with mixture of lubricants, diesel fuel, and phenol; northwestern part of Minsk |

| SV12 | Apr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries 195-kb plasmid pSVS12 | Park soil with no history of known contamination; northeastern part of Minsk |

| SV13 | Nalr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries 78-kb plasmid pSVS13 | Same as SV12 |

| SV15 | Cmr Hgr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries 90-kb plasmid pSVS15 | Piece of rubber from storage of used car tires; central part of Minsk |

| SV16 | Apr Cmr Hgr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries 123-kb plasmid pSVS16 | Sandy soil contaminated with diesel oil; building area in northeastern part of Minsk |

| SV17 | Apr Tcr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries ∼200-kb plasmid pSVS17 | Sandy washout from a highway contaminated with a mixture of oil products; central part of Minsk |

| SV19 | Apr Tcr Cmr Hgr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+ Sal+; carries 107-kb plasmid pSVS19 | Shoreline sediments contaminated with a mixture of oil products; Swislach River, central part of Minsk |

| SV20 | Apr Hgr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries plasmid pSVS20 (>200 kb) | Same as SV19 |

| SV22 | Apr Kmr Tcr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries 126-kb plasmid pSVS22 | Sandy soil contaminated with a mixture of industrial lubricants and engine oil; local landfill 10 km from the southwestern border of Minsk |

| SV23 | Apr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries 130-kb plasmid pSVS23 | Same as SV22 |

| SV24 | Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries 105-kb plasmid pSVS24 | Same as SV22 |

| SV25 | Cmr Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; carries a 2-kb cryptic plasmid | Piece of road cover material; local landfill 10 km from the southwestern border of Minsk |

Apr, Tcr, Kmr, Nalr, Cmr, and Hgr, resistance to ampicillin, tetracycline, kanamycin, nalidixic acid, chloramphenicol, and HgCl2, respectively, in the concentrations given in Materials and Methods. Tln+, mXln+, mTol+, Ben+, and Sal+, ability to use toluene, m-xylene, m-toluate, benzoate, and salicylate, respectively, as sole carbon and energy sources. C2,3O+, positive for C2,3O activity.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Bacterial strains and plasmids | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | F−supE44 (φ80dlacZΔM15) Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 (Nalr) thi-1 relA deoR | Gibco BRL Life Technologies |

| E. coli ED8654 | supE supF hsdR metB lacY gal trpR; host for propagation of pWW53-3001 and pWW53-3002 | P. A. Williams |

| E. coli LE392(RP1) | Plasmid of IncP1 incompatibility group; Kmr Tcr | S. Harayama |

| P. putida mt-2 | Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; host of pWW0 | P. A. Williams |

| P. putida MT53 | Tln+ mXln+ mTol+ Ben+ C2,3O+; host of pWW53 | P. A. Williams |

| P. putida AC13 | His− Rifr Smr; recipient strain for TOL plasmids | A. Boronin |

| P. putida AC34(pMG18) | Plasmid of IncP9 incompatibility group; Smr Gmr Kmr Hgr | G. Jacoby |

| Plasmids | ||

| pWW53-3001 | HindIII 17.5-kb fragment of pWW53 cloned in pKT230; contains meta pathway operon II | P. A. Williams |

| pWW53-3002 | HindIII 15.6-kb fragment of pWW53 cloned in pKT230; contains meta pathway operon I | P. A. Williams |

| pUC18 | Apr ColE1 replicon; general cloning vector | Promega Corporation |

| pUC28 | Apr ColE1 replicon; general cloning vector | Promega Corporation |

| pGEM-T Easy | Apr ColE1; linearized pGEM-5Zf(+) with single 3′ thymidine overhangs to facilitate cloning of PCR products | Promega Corporation |

| pPL392 | 16.4-kb EcoRI fragment of pWW0; contains complete meta cleavage pathway operon and xylS cloned into pBR322 | 18 |

| pCVS22 | 6.3-kb EcoRI fragment of pSVS11 cloned into pUC18; contains xylW (3′ end) and xylCMABN (5′ end) | This study |

| pCVS31 | 5.3-kb HpaI fragment of pSVS10 cloned into pUC28; contains xylC (3′ end) and xylMABN (5′ end) | This study |

| pCVS32 | 5.3-kb HpaI fragment of pSVS11 cloned into pUC28; contains xylC (3′ end) and xylMABN (5′ end) | This study |

| pCVS42 | 5.5-kb HpaI fragment of pSVS10 cloned into pUC28; contains xylS (5′ end), xylR, interoperonic area, xylU, and xylW (5′ end) | This study |

Rifr, Smr, and Gmr, resistance to rifampin, streptomycin, and gentamicin, respectively. His−, histidine negative. For other abbreviations, see Table 1, footnote a.

Plasmid curing experiments.

Plasmid-free and plasmid deletion derivatives of the toluene-degrading strains were isolated during repeated cultivation on benzoate (31, 56). The catechol spray test was used to distinguish wild-type cells from any mutant cells lacking C2,3O activity. Wild-type colonies turned bright yellow due to the production of 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde by C2,3O, whereas the colonies formed by plasmid-free cells or by those carrying deletions in their plasmid DNAs, resulting in a loss of the gene for C2,3O, remained white. Colonies formed by mutants with a reduced level of C2,3O activity turned pale yellow. The sensitivity of detection of mutants on plates was approximately 1 mutant among 10,000 colonies. Mutants were purified by streaking on LB agar, and the relevant catabolic phenotypes were tested by plating on solid MM supplemented with the appropriate carbon sources. In a few instances, when growth on benzoate did not produce any plasmid mutants, mitomycin C was added to liquid benzoate-containing MM at a concentration of 1.25, 2.5, 5.0, or 7.5 μg/ml.

Filter mating experiments.

Donor and recipient strains were grown overnight at 30°C in 5 ml of LB medium to a cell density of about 109 cells/ml. Cells from 1 ml of each culture were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 1 ml of fresh LB medium, mixed, and incubated for 3 h at 27°C without shaking. The resulting conjugation mixture was harvested by a 5-min spin at 3,000 rpm in a Biofuge 13 microcentrifuge (Hereaus AG, Zurich, Switzerland) and transferred by gentle pipetting onto 0.45-μm-pore-size cellulose nitrate filters (Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany). The filters were placed on LB agar plates, which were incubated for 24 h at room temperature. Cells were then washed from the filters with a 0.9% NaCl solution, serially diluted, and plated on MM or LB agar plates supplemented with the appropriate carbon source, antibiotics, or amino acids. Separate cultures of the donor and recipient strains were treated and plated in the same way to provide negative controls. Colonies of transconjugants were purified by streaking on selective agar plates and tested for the presence of relevant phenotypic markers. Plasmid DNA was isolated and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis directly or after digestion with the appropriate endonucleases.

Plasmid incompatibility test.

Plasmids RP1, belonging to plasmid incompatibility group IncP1 (22), and pMG18, belonging to group IncP9 (25), were introduced into SV strains (Table 1) through the filter mating procedure (see above). Transconjugants were selected on glucose-MM agar plates with the appropriate antibiotics plus 0.05 mM m-toluate to induce C2,3O. Colonies grown for 48 h were checked by the catechol spray test for the presence of C2,3O activity, which was indicative of the presence of plasmids involved in toluene catabolism.

Isolation of plasmid DNA.

Recombinant plasmid DNA molecules were isolated from E. coli DH5α by using the method of Holmes and Quigley (46). If necessary, a neutral phenol-chloroform extraction step was introduced before precipitation of the plasmid DNA. Plasmids obtained from Pseudomonas and used for the restriction analysis were isolated by using a scaled-up variant of the alkaline sodium dodecyl sulfate lysis protocol of Birnboim and Doly (7) with the following modifications. After precipitation with isopropanol, plasmid DNA was dissolved in a solution of 10 mM Tris-HCl–1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) containing 10 μg of proteinase K per ml, incubated at 50°C for 1 h, and treated with a solution of 1% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide–0.7 M NaCl to remove polysaccharides (5). The resulting supernatant was extracted once with an equal volume of neutral phenol-chloroform and once with chloroform. Plasmid DNA was again precipitated with isopropanol, and the pellet was rinsed with 70% ethanol, briefly air dried, and dissolved in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 20 μg of pancreatic DNase-free RNase per ml. Large-scale isolation of highly purified plasmid DNA was performed by using the method of Hansen and Olsen (16), followed by CsCl-ethidium bromide (EtBr) gradient density centrifugation (46). Plasmids refractory to preparative isolation were visualized by using the in-well cell lysis method of Eckhardt (10) as described by Plazinski et al. (40) with minor modifications.

DNA manipulations.

Transformations in E. coli, restriction enzyme digestion, and other DNA manipulations were carried out according to established procedures (46). Restriction enzymes and other DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from Amersham Life Science (Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) and used according to the specifications of the manufacturer.

Southern hybridization.

Southern hybridization was performed essentially as described by Ravatn et al. (43, 44). E. coli strains carrying the cloned xyl genes of pWW0 were used to generate the following probes for hybridization: a 7.4-kb EcoRI fragment containing xylXYZLTEGFJQ, an 0.8-kb BspHI fragment with an internal portion of xylE, a 1.6-kb SmaI fragment with xylK and xylJ, a 3.0-kb SmaI fragment with xylR and xylS, and a 1.5-kb BglII fragment with xylR only. Gene probes for xylUW and xylA were synthesized as described by James and Williams (24) by PCR with the following primers: xylUW-for, 5′-TTC AGA TTG GTT GCT TTC GCC; xylUW-rev, 5′-GCT CTT TTG TTT CCC GCA TAA; xylA-for, 5′-AAG CGA AGA GCG GAA C; and xylA-rev, 5′-TTT TGG CCG CAA GAC GAT. A 20-kb HpaI/XbaI fragment of pSVS13 was used as a probe for testing DNA homologies to the plasmid region outside the xyl catabolic genes.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of plasmid DNA.

Plasmid DNAs isolated by CsCl-EtBr density gradient centrifugation from each selected Pseudomonas isolate were digested with EcoRI, and the fragments were separated through an 0.85% agarose gel in TAE buffer (0.04 M Tris-acetate, 0.01 M EDTA [pH 8.0]) at 4°C for 14 h at 30 V without EtBr. Gels were stained with EtBr after being run and were photographed. Digitally recorded banding patterns were analyzed with the program RFLPscan (Scanalytics, Billerica, Mass.). Fragment sizes were calculated by comparing their electrophoretic mobilities with those of 1- and 5-kb markers (Bio-Rad Laboratories AG, Glattbrugg, Switzerland) and were inspected manually to avoid data misrepresentation due to any image distortion. The presence (designated 1) or absence (designated 0) of bands of the same size in a digest profile was scored and used to produce a two-dimensional rectangular data matrix of binary codes for each of the plasmid digests; this matrix was subsequently used in cluster analysis. Bootstrapping with the program SEQBOOT from PHYLIP (11) was performed to generate 100 data sets. Clustering analysis was performed on the multiple data sets by using the subroutine DOLLOP from PHYLIP with randomized input order.

ARDRA and REP-PCR genomic fingerprinting.

Amplification of a nearly full-length 16S rDNA was performed by PCR with conserved eubacterial primers 16S 6F (5′-GGA GAG TTA GAT CTT GGC TCA G-3′) and 16S 1510 (5′-GTG CTG GAG GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT-3′) (49). Repetitive sequence-based PCR (REP-PCR) genomic fingerprinting was carried out as described previously (52) with primer pair REP1R-1 (5′-III ICG ICG ICA TCI GGC-3′) and REP2-1 (5′-ICG ICT TAT CIG GCC TAC-3′) and primer pair ERIC1R (5′-ATG TAA GCT CCT GGG GAT TCA C-3′) and ERIC2 (5′-AAG TAA GTG ACT GGG GTG AGC G-3′) on total genomic DNA isolated from each Pseudomonas strain by the method of Marmur (32). REP-PCR products and 16S rDNA PCR copies, the latter digested with DdeI, HaeIII, or HinfI, were separated on a 1 or 2% agarose gel, digitally recorded, and analyzed as described above. For one representative of each amplified 16S rDNA restriction analysis (ARDRA) class, the amplified 16S rDNA fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega Corporation) and sequenced on a single strand only.

Amplification of xylA and xylUW by PCR.

The complete xylA-xylUW area was amplified by using PCR with primers xylA-for–xylA-rev and xylUW-for–xylUW-rev (see above). A new set of primers to amplify xylA from plasmids pSVS11 and pSVS15 was designed in this study based on the sequence of the xylA area of pSVS11: xylA11-for, 5′-CTG AAA AGG CCC AAG GAT AAC T; and xylA11-rev, 5′-CCA GAG CTT TTG CGG GAT GAA CTA. Purified plasmid DNA was used as a template in the PCR, and the reaction conditions were those described by James and Williams (24).

Sequence analysis.

DNA sequencing was performed on an automated DNA sequencer (model 4200IR2; LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, Nebr.) as described elsewhere (43). Databases were searched for homologous gene sequences by using the BLAST program (2). Multiple sequence alignments were created by using the Genetics Computer Group program PILEUP (9) and further refined manually in WORD (Microsoft Corp.). A total of 100 multiple data sets of each alignment were generated by bootstrapping as described above. The clustering of sequences was done by using the programs PARSIMONY and NEIGHBOR from PHYLIP. Phylogenetic inferences were also evaluated by using CLUSTAL V enclosed within the Lasergene package (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, Wis.).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences obtained in this study are available in GenBank under accession numbers AF251321 to AF251332 (xylA), AF251333 to AF251337 (16S rDNA), and AF251338 to AF251343 (xylL and xylT).

RESULTS

Isolation and identification of toluene degraders.

For all soil samples, except for the park soil without a record of oil contamination, enrichments on m-toluate grew to a visible density within 24 h. Fast-growing colony types, which appeared on TMA that had been inoculated with serial dilutions of the enrichments, were selected and further purified. This process resulted in a total of 20 strains (Table 1) consisting mostly of two different strains from each location. All strains were able to grow on toluene, m-xylene, and benzoate and demonstrated inducible C2,3O activity. None of them utilized phenol, whereas two strains utilized salicylate. Growth on salicylate, however, did not induce C2,3O activity. On the basis of morphological and physiological properties (data not shown), all strains were classified as species of the genus Pseudomonas according to Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (30). The classification was further confirmed by ARDRA and by 16S rDNA gene sequencing.

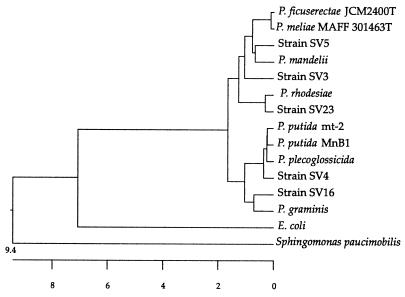

Restriction analysis of the 16S rDNA fragments amplified by PCR with DdeI, HaeIII, and HinfI, including as a reference 16S rDNA derived from Pseudomonas putida strain mt-2 (54), divided the 20 isolates into five subgroups (Fig. 1). DNA sequences determined on one strand of cloned 16S rDNA amplification products derived from one strain of each subgroup were indeed most homologous to those of other Pseudomonas species (Fig. 1). This result indicated that the range of bacterial hosts carrying genes for the catabolism of toluene and xylene via a meta cleavage pathway was limited to species of the genus Pseudomonas belonging to the proposed “P. fluorescens intragenic cluster” (36). Nevertheless, on the strain level, the majority of the strains were not closely related, as judged from the dissimilarity of their REP-PCR and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus-PCR patterns (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on a comparison of 1,499 positions in the 16S rDNA sequences of Pseudomonas sp. SV strains, representative of each ARDRA subgroup, and eight neighboring sequences from the GenBank database (accession numbers are shown in parentheses): P. putida MnB1 (U70977), P. putida mt-2 (L28676), P. plecoglossicida (AB009457), P. mandelii (AF058286), P. graminis sp. nov. (Y11150), P. ficuserectae JCM2400T (AB021378), P. meliae MAFF 301463T (AB021382), and P. rhodesiae (AF064459). The 16S rDNA sequences of Sphingomonas paucimobilis strain UT26 (AF039168) and E. coli (A14565) were used as outgroups. Groups of SV strains determined by ARDRA were as follows: (i) SV1, SV2, SV4, SV20, and SV25; (ii) SV9, SV10, SV11, SV12, SV13, SV15, SV16, SV17, SV19, SV20, SV22, and SV24; (iii) SV3; (iv) SV5; and (v) SV23 (boldface strain names appear in the tree). The tree was constructed by using CLUSTAL V. The scale below the tree indicates the sequence distances as the number of substitutions per 100 nucleotides.

Plasmid location of genes involved in toluene catabolism.

Analysis of plasmid profiles in our Pseudomonas isolates revealed the presence of extrachromosomal circular covalently closed DNA elements of high molecular weight in 17 strains. The plasmids were named pSVS3 through pSVS24, and their sizes were estimated to range from 78 to 200 kb (Table 1). No large plasmids were detected in strains SV1, SV2, and SV25 by any of the plasmid visualization techniques applied. From analogy to the TOL plasmids (4), it seemed reasonable to assume that the genes for toluene catabolism would be located on the pSVS plasmids. Thus, we tested this assumption in a series of plasmid curing and conjugation experiments. Repeated cultivation on benzoate produced derivatives for all strains which were unable to utilize m-toluate, toluene, or m-xylene and which lacked C2,3O activity, except for SV1, SV2, SV22, SV23, and SV25. Of those remaining five, Tol−, C2,3O-negative (C2,3O−) derivatives could be obtained only for strains SV1, SV2, and SV23 and not for strains SV22 and SV25 by using mitomycin C. Both benzoate and mitomycin C are known to be effective in curing plasmids involved in toluene degradation in Pseudomonas (31, 38, 39, 56, 57). Like other strains bearing TOL plasmids, the Tol−, C2,3O− derivatives obtained in our study all demonstrated higher growth rates on benzoate than did their wild-type counterparts and finally displaced these from the benzoate-grown cultures (data not shown).

Plasmid analyses of the wild-type and Tol−, C2,3O− derivative strains (Table 3) clearly indicated large-scale rearrangements in or complete disappearance of the plasmid DNA in the derivatives. This result suggested that the pSVS plasmids were involved in toluene degradation. Interestingly, the 120-kb plasmid of strain SV22 (pSVS22) was stable, and no Tol− derivatives could be produced. However, since pSVS22 demonstrated structural similarity to the other plasmids (see below), we believe that this plasmid encoded toluene catabolism. Since no large plasmid replicons could be detected in strains SV1, SV2, and SV25, since cultivation on benzoate did not lead to the appearance of C2,3O− derivatives, and since the Tol+ phenotype could not be transferred by conjugation, we concluded that in these three strains the genes responsible for toluene degradation are located on the chromosome.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of loss of catabolic function after repeated cultivation of toluene-degrading strains on benzoate and frequencies of conjugational transfer

| Pseudomonas sp. strain | Characteristics of Ben+, Tol− derivatives | Frequency of conjugational transfera |

|---|---|---|

| SV1 and SV2 (no large plasmids detected) | Obtained after mitomycin C treatment | <1.0 × 10−8 |

| SV3(pSVS3) | Loss of the entire plasmid | 5.3 × 10−4 |

| SV4(pSVS4) | Loss of the entire plasmid | 4.2 × 10−7 |

| SV5(pSVS5) | Loss of the entire plasmid or 40-kb deletion | 1.1 × 10−6 |

| SV6(pSVS6) | Loss of the entire plasmid | <1.0 × 10−7 |

| SV9(pSVS9) | Loss of the entire plasmid | 1.0 × 10−4 |

| SV10(pSVS10) | Loss of the entire plasmid or 40-kb deletion | ∼1.0 × 10−7 |

| SV11(pSVS11) | Loss of the entire plasmid or 5-, 20-, or 40-kb deletion | 1.5 × 10−3 |

| SV12(pSVS12) | Loss of the entire plasmid or 35- or 45-kb deletion | 3.3 × 10−4 |

| SV13(pSVS13) | Loss of the entire plasmid or 35- or 60-kb deletion | 1.0 × 10−8 |

| SV15(pSVS15) | Loss of the entire plasmid | 2.0 × 10−3 |

| SV16(pSVS16) | Loss of the entire plasmid or 45-kb deletion | <1.8 × 10−8b,c |

| SV17(pSVS17) | Loss of the entire plasmid | 1.0 × 10−8 |

| SV19(pSVS19) | Loss of the entire plasmid or 35-, 60-, or 70-kb deletion | 3.5 × 10−7 |

| SV20(pSVS20) | 20-kb deletion | 2.9 × 10−7c |

| SV22(pSVS22) | No mutants obtained | <5.5 × 10−9 |

| SV23(pSVS23) | Loss of the entire plasmid after treatment with mitomycin C | <1.0 × 10−8 |

| SV24(pSVS24) | 40-kb deletion | <1.0 × 10−8 |

| SV25 (no large plasmid detected) | No mutants obtained | <1.0 × 10−9 |

The frequency of transfer of pSVS plasmids was calculated as the ratio of the number of transconjugants detected after mating to the number of donor cells (P. putida strain AC13) added to the crossing mixture.

The plasmid was not able to transfer by itself but could be mobilized into a new host by plasmid RP1.

Mercury resistance genes were cotransferred with the pSVS plasmid.

To test the presence of additional markers on the pSVS plasmids, such as resistance to antibiotics or Hg2+, growth of the wild-type strains and that of their plasmid-free derivatives or transconjugants on agar plates supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics or with HgCl2 were compared (35). Although many strains were highly resistant to ampicillin, tetracycline, kanamycin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, or nalidixic acid (Table 1), none of these markers could be associated with the presence of pSVS plasmids. In contrast, two of five strains resistant to Hg2+, i.e., SV16 and SV20, seemed to carry mercury resistance genes on their plasmids, since the mercury resistance marker could be cotransferred together with the genes involved in toluene degradation to a new host (Table 3).

From filter mating experiments with the different Pseudomonas SV strains and a Rifr Smr derivative of P. putida strain AC13 as a recipient, 12 m-toluate-degrading transconjugants were obtained. The transfer frequencies varied greatly: from 1.0 × 10−8 to 2.0 × 10−3 transconjugants per donor cell (Table 3). All the transconjugants possessed the same catabolic phenotype and carried a plasmid of the same size as the respective donor strain, as judged by the electrophoretic mobility of the intact plasmid molecules (data not shown). This result suggested that during plasmid transfer, no substantial plasmid rearrangements took place. No transconjugants were obtained when Pseudomonas sp. strains SV1, SV2, and SV25 were used as donors.

Incompatibility of pSVS plasmids.

All the pSVS plasmids, except for pSVS15, were stably comaintained with pMG18 and RP1, suggesting that they belong to plasmid incompatibility groups different from IncP1 and IncP9. Plasmid pSVS15 was stably comaintained with RP1 but not with pMG18, suggesting that the plasmid replicon of pSVS15 is of the IncP9 type. This notion was further confirmed by sequencing of a PCR-amplified IncP9-specific region from pSVS15 (A. Greated, personal communication). Interestingly, in a few instances, colonies of Pseudomonas sp. strain SV15 to which pMG18 was transferred retained the catabolic phenotype of the parent strain SV15. Analysis of the plasmid content of these colonies indicated restriction fragments of only pMG18, suggesting complete elimination of pSVS15 but an apparent integration of the toluene catabolism genes from pSVS15 into the chromosome.

Organization of toluene catabolism genes on plasmids and their homology to xyl genes of pWW0.

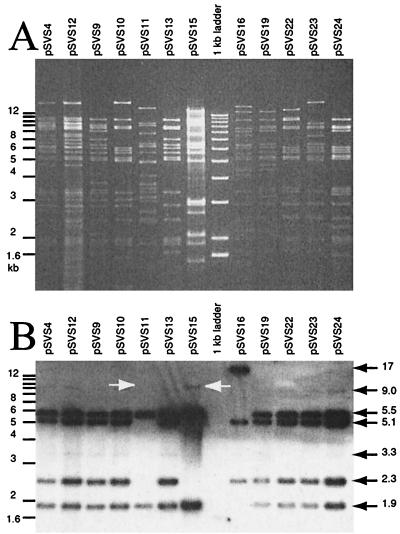

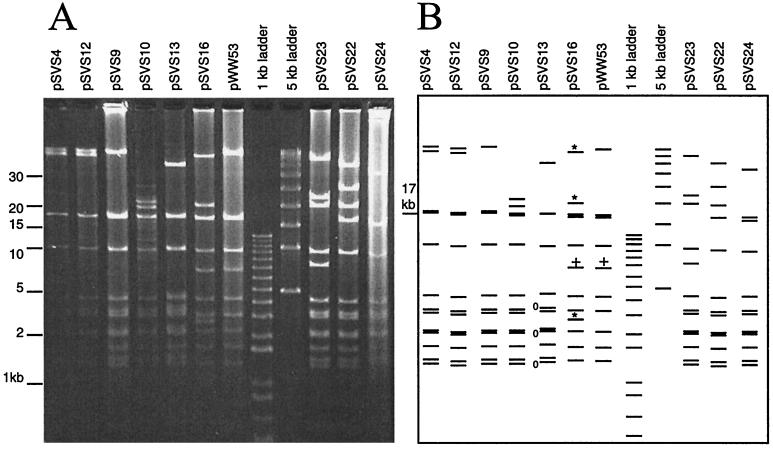

We purified plasmid DNAs from 12 strains and analyzed the plasmids by Southern hybridization for the presence of DNA homologous to the xyl genes of pWW0. Hybridization of the EcoRI-digested DNA of the pSVS plasmids with a 7.4-kb DNA probe containing the xylX through xylQ genes of pWW0 (20) showed clear signals, indicating that indeed xyl-homologous genes were present on the pSVS plasmids. However, we discovered three types of hybridization patterns, one exemplified by pSVS11 and pSVS15, a second by most of the other isolated plasmids, and the third unique for pSVS16 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

(A) Selected pSVS plasmid DNAs digested with EcoRI. (B) Autoradiogram of hybridization with the 7.4-kb EcoRI fragment of pWW0 containing the meta pathway operon genes xylXYZLTEGFJQ. Molecular size markers are indicated on the left in kilobase pairs (kb). Arrows on the right indicate sizes of fragments hybridizing to the probe. Note the absence in the digests of pSVS11 and pSVS15 of the 2.3-, 5.1-, and 3.3-kb fragments, which are characteristic for the presence of a second copy of the meta pathway operon. The 9-kb hybridizing fragments in pSVS11 and pSVS15 were also slightly larger than those in the other pSVS plasmids (marked by the white arrows on the autoradiogram). Note also the absence of the 9.0-, 5.5-, and 1.9-kb fragments from pSVS16 and the appearance of a new fragment of 17 kb. The digital image was recorded on Gel Print 2000I (MWG-Biotech), stored as a TIFF file, and displayed in Canvas 3.5.5 (Deneba Software, Miami, Fla.).

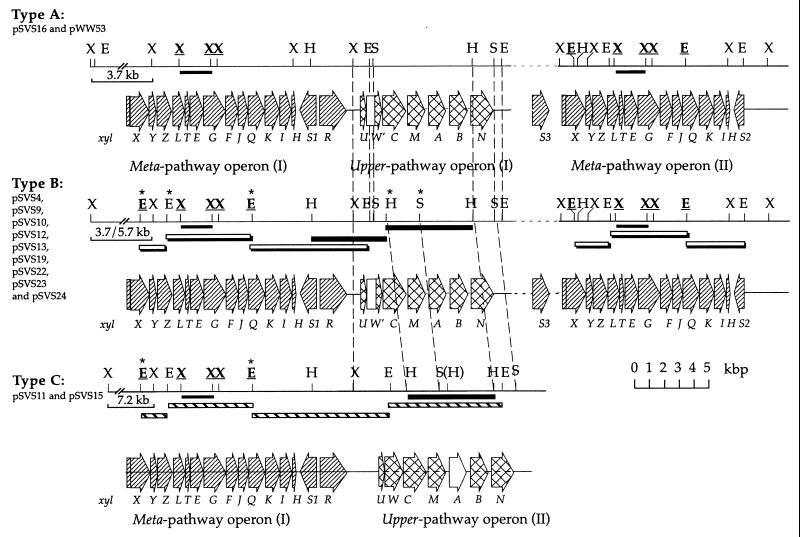

Subsequent hybridization with the other xyl gene probes to plasmid DNAs digested with the restriction enzymes EcoRI, HpaI, and XhoI further refined the presence and localization of xyl-related genes on the pSVS plasmids. From this analysis it became apparent that several pSVS plasmids carried two meta cleavage gene clusters (Fig. 3). The positions of restriction sites within the xyl-homologous regions were verified by cloning into pUC18 the 1.9-, 5.5-, 9.0-, and 10.2-kb EcoRI fragments from both pSVS11 and pSVS13 and the 2.3-, 3.3-, and 5.1-kb EcoRI fragments from pSVS13, covering genes of both meta pathway operons (Fig. 3). Restriction analysis showed that plasmids pSVS11 and pSVS15 (designated type C) carried a similar meta cleavage gene cluster (designated meta operon I), followed by the xylS and xylR genes and by the upper pathway operon (designated upper operon II). The other 10 plasmids, referred to as type A and type B, carried xyl gene clusters similar to those of type C but, in addition, another meta pathway operon (designated meta operon II) and two extra copies of xylS-homologous sequences. One of these, xylS2, was situated at the end of meta operon II, but a second, xylS3, was not directly associated with the other xyl genes (Fig. 3). The organization of xyl genes found in plasmids of type A and type B was very similar to that found in TOL plasmid pWW53, isolated in North Wales, United Kingdom (26). Plasmid pWW53 has been extensively studied; therefore, the organization of the xyl genes and the physical map of the complete plasmid (3, 15, 27, 38) could be compared in detail to those of the pSVS plasmids.

FIG. 3.

Comparative organization of xyl genes on the different pSVS plasmids and pWW53. Locations of individual genes are marked with hatched and cross-hatched arrows, the directions of which indicate the direction of transcription. The abbreviations for restriction enzyme sites are as follows: E, EcoRI; H, HpaI; S, SpeI; and X, XhoI. Only XhoI recognition sites within and close to meta pathway operons are shown. Restriction sites conserved among meta pathway operons are underlined and in boldface, those absent from pSVS16 are marked by asterisks, and the one in parentheses is present only in pSVS15. The area between upper operon I and meta operon II and xylS3 are indicated by horizontal broken lines to indicate longer distances (see Fig. 4 for exact distances). Vertical broken lines connect the identical restriction sites within and close to the upper pathway operons. Note a 1.0-kb longer spacing between upper pathway operon I and meta pathway operon I in pSVS11 and pSVS15 than between those in plasmids of types A and B. Doubly shaded bars below the restriction maps indicate the EcoRI fragments cloned from pSVS13; those from pSVS11 are shown by hatched bars. The 2.1-kb XhoI fragments which were cloned from pSVS11, pSVS15, pSVS13, and pWW53 for sequencing are indicated by thin black bars. Thick black bars indicate the HpaI fragments cloned into pCVS31, pCVS32, and pCVS42 (Table 2). A 370-nucleotide region upstream of xylC in plasmids of types A and B is 99% identical to the ntnW gene of P. putida TW3 (93 and 96% identical to xylW in pWW0 and pDK1, respectively) but is preceded by a region without any homology to xylW (open box). The open arrow for the xylA sequence of pSVS11 and pSVS15 depicts its distinct low homology to the other xylA sequences, as opposed to the surrounding xylC, xylM, xylB, and xylN sequences.

Conservation of xyl gene order among pSVS plasmids of types A and B.

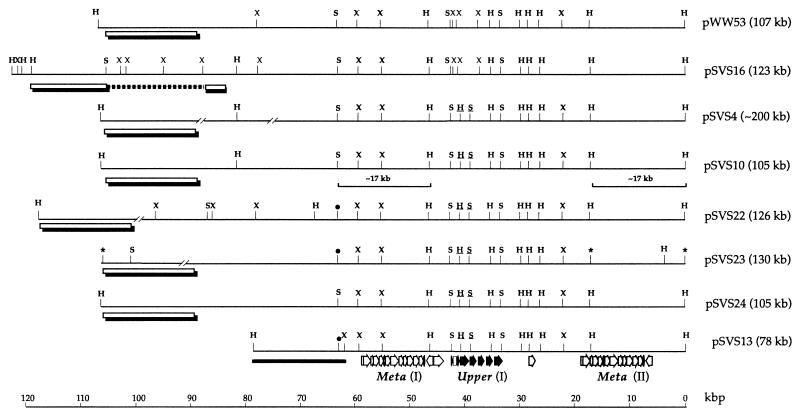

Complete physical maps for plasmids of types A and B (pSVS4, pSVS9, pSVS10, pSVS12, pSVS13, pSVS16, pSVS19, pSVS20, pSVS22, pSVS23, and pSVS24) and pWW53 were generated by digestion with SpeI and XbaI and orientation of those sites with respect to the restriction maps for EcoRI and HpaI. The relative positions of the various xyl-related genes on the pSVS plasmids were confirmed by hybridization with corresponding xyl gene probes.

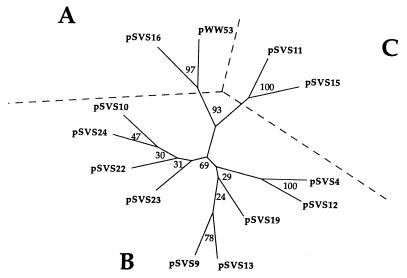

From the sizes and the presence of all HpaI/SpeI restriction fragments smaller than 17 kb, which cover the whole area of the catabolic genes and the interoperonic region (Fig. 4 and 5), we deduced that all plasmids, except for pSVS16, pWW53, and pSVS23, were the same in this area. Displacement of one 17-kb fragment flanking the area of the catabolic genes from pSVS23 (Fig. 5) could be explained by assuming the loss of the single HpaI site from meta operon II and a shifted position of the rightmost HpaI site. Displacement of the other 17-kb fragment could be explained by assuming the absence of the leftmost SpeI site, which is also absent from pSVS13 and pSVS22 (Fig. 4). Plasmid pSVS16 had the same restriction sites as pWW53 in the catabolic gene area, except for one XbaI site (Fig. 4). A total of 22 restriction sites were conserved among the catabolic operons of type B pSVS plasmids (Fig. 3 and 4), which were slightly different in pSVS16 and pWW53. The main other variability among the plasmids of types A and B occurred outside the catabolic gene area (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Aligned restriction maps of selected plasmids of types A and B. Positions of individual xyl genes are depicted as in Fig. 3. Abbreviations: H, HpaI; S, SpeI; X, XbaI. Asterisks depict HpaI restriction sites absent from the catabolic gene area of pSVS23. Underlined are HpaI and SpeI restriction sites absent from the upper pathway operons in pSVS16 and pWW53. Filled circles mark SpeI sites absent from pSVS13, pSVS22, and pSVS23. The black bar indicates the region of pSVS13 used for probing plasmid backbone similarities. Doubly shaded bars indicate DNA areas in other plasmids hybridizing to the backbone probe. A putative 16-kb DNA insertion in pSVS16 (compared to pWW53) is shown as a broken line. Note the size and restriction site variability in the regions outside the catabolic genes.

FIG. 5.

Stained agarose gel (A) and graphic interpretation (B) of the HpaI/SpeI double digest of selected pSVS and pWW53 plasmid DNAs. Molecular size markers are indicated on the left in kilobase pairs (kb). Note the similarities in restriction fragments smaller than 17 kb, which are representative of the xyl operons. The 17-kb fragment is missing from pSVS23. Displacement of three fragments (depicted by 0) by a single 7.8-kb fragment (depicted by +) in pSVS16 and pWW53 is the result of the loss of the single HpaI and SpeI sites from their upper pathway operons (see also Fig. 4). The presence of three new fragments in pSVS16 (indicated by asterisks) displacing the largest HpaI/SpeI fragment in pWW53 is thought to be due to an extra 16 kb of DNA in the plasmid backbone of pSVS16 (compare with Fig. 4). The digital image was recorded on Gel Print 2000I, stored as a TIFF file, and displayed in Canvas 3.5.5.

Specific features of pSVS11 and pSVS15.

In contrast to the type A and B plasmids, pSVS11 and pSVS15 carried single upper and meta pathway gene clusters (Fig. 3). These resembled the operons of the type A and B plasmids, although the upper pathway operon was located about 1.0 kb farther from xylR than in the type A and B plasmids (Fig. 3). The positions of restriction sites within the upper pathway operons of both pSVS11 and pSVS15 were also slightly different from those in the type A and B plasmids (Fig. 3). However, the meta pathway operons of pSVS11 and pSVS15 were indistinguishable in the physical map from meta operon I of the type B plasmids (Fig. 3).

It is noteworthy that the area of homology in pSVS11 and pSVS15 seemed to be extended at least 5 kb beyond the beginning of the meta pathway operon, as judged from the presence of a similar XhoI fragment of 7.2 kb (Fig. 3). Outside the catabolic gene region, however, pSVS11 and pSVS15 did not share similar restriction sites and seemed to differ extensively from one another and from the type A and B plasmids (Fig. 2 and 6).

FIG. 6.

Dendrogram illustrating the relationships among pSVS plasmids and pWW53 based on their RFLP patterns, generated by cutting with EcoRI. Clustering analysis was performed on the multiple data set by using DOLLOP. Bootstrapping values are shown in the nodes. Note that the plasmids are clustered in a manner similar to the arrangement based on the restriction analysis of their catabolic genes (Fig. 3).

Relationships among type A, B, and C plasmids.

According to the RFLP patterns of the complete plasmids generated by EcoRI digestion (Fig. 2), the pSVS plasmids and pWW53 were classified into three groups (Fig. 6). This clustering was entirely consistent with the three groups based on the organization of the xyl genes and the positions of the restriction sites within the area of the catabolic genes (Fig. 3). However, even within the largest group of plasmids (type B), two subclusters could be distinguished (Fig. 6).

Similarities among the plasmids outside the xyl gene regions were further tested by Southern hybridization of SpeI/XbaI-digested plasmids with the 18-kb HpaI/XbaI fragment of pSVS13 (Fig. 4). We assumed that this fragment encoded plasmid maintenance and conjugation functions, since pSVS13 was conjugative and this fragment covered the smallest contiguous region among pSVS plasmids outside the catabolic gene area (Fig. 4). All the plasmids of types A and B but not of type C showed strong hybridization under high-stringency conditions with the pSVS13 fragment (Fig. 4). Still, the overall sizes of the complete plasmids were substantially different (for example, 78 kb for pSVS13 and ca. 200 kb for pSVS4 and pSVS12). Furthermore, large DNA areas did not hybridize with either xyl or pSVS13 gene probes and had different restriction sites (Fig. 4 and 5). From these results we concluded that the type A and B plasmids have a common plasmid backbone but that large DNA rearrangements, e.g., additions and deletions, outside the xyl gene regions must have occurred. The type C plasmids showed no strong homology in their backbones with those of types A and B, since they did not hybridize to the pSVS13 probe. In addition, pSVS15 belonged to a distinct incompatibility group, as shown above.

Comparison of DNA sequences of the meta pathway operons of pSVS11, pSVS13, pSVS15, pWW53, and pWW0.

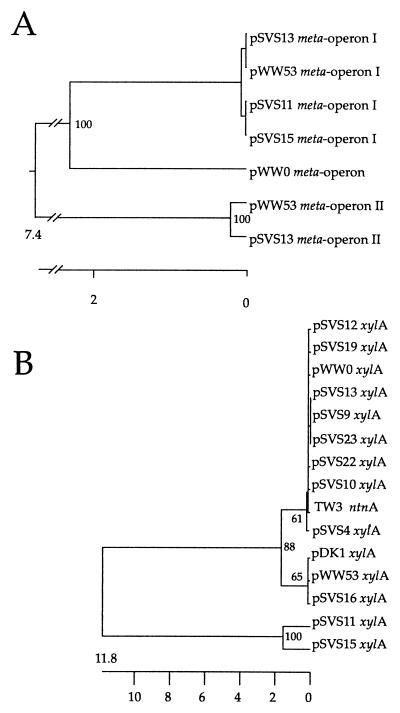

In order to evaluate the degree of sequence similarity among the different meta cleavage gene clusters, we cloned into pUC28 and partly sequenced the conserved 2.1-kb XhoI fragments from pSVS13 (as an example for the type B plasmids), pSVS11, pSVS15, pWW53-3001, and pWW53-3002 (Table 2). All the fragments invariably contained DNA homologous to the xyl genes of pWW0 and in the following gene order: xylL (3′ end), xylT, xylE, and xylG (5′ end) (Fig. 3). The 730-nucleotide 5′-end sequences were aligned together with the homologous sequence of pWW0 (GenBank accession no. M64747; positions 3844 to 4604), encoding the last 127 amino acid residues of the C-terminal end of XylL (257 amino acids; accession no. S23485) and 64 amino acids of the N-terminal end of XylT separated by a noncoding intergenic region. Maximum-parsimony analysis statistically divided the sequences into three groups, with four sequences of meta operon I clustering together (Fig. 7A) but separated from the sequences of meta operon II and the pWW0 sequence. Estimated phylogenetic distances among the four type I sequences were negligibly short (0.0 to 0.1% sequence divergence), indicating that meta cleavage gene clusters of type I, although present on different plasmids, are virtually identical. However, this group of sequences was quite distant from the pWW0 sequence (4.6 to 4.7% divergence) and even more distant from the meta operon II sequences (14.8 to 15.4% divergence). The level of divergence within sequences of the meta operon II was about 0.4%.

FIG. 7.

Phylogenetic comparison of selected DNAs from the different meta pathway operons and upper pathway operons of several pSVS plasmids of types A, B, and C and corresponding sequences of other TOL plasmids. (A) Alignment based on 730 nucleotides within xylL and xylT (Fig. 3). (B) Alignment based on 395 nucleotides at the 3′ end of xylA. From the pWW0 sequence of the xylLT region, 36 nucleotides (positions 4229 to 4265) were left out, apparently introduced by mistake (P. Golyshin, personal communication). Trees were constructed by using CLUSTAL V. The scales below the trees indicate the sequence distances as the number of substitutions per 100 nucleotides. Only bootstrapping values above 50% occurring in 100 replicate trees, obtained by using the PARSIMONY program, are shown in the nodes.

Comparison of xylA sequences.

By using PCR with purified plasmid DNAs, we amplified xylA gene fragments of 11 pSVS plasmids (omitting pSVS24) and pWW53. Sequences of 395 nucleotides from the 3′ end of each xylA open reading frame were compared with the corresponding DNA sequences of pWW0 (accession no. D63341), pDK1 (accession no. AF019635), and ntnA (accession no. AF043544). Phylogenetic analysis divided all sequences into three groups (Fig. 7B), similar to those based on the restriction analysis. The xylA sequences of all pSVS plasmids of type B appeared to be 99.5 to 100% identical to each other, to xylA of pWW0, and to ntnA from the chromosome of P. putida strain TW3 (24). In contrast to the differences between the meta pathway operon sequences of pWW0 and type A and B plasmids, xylA of pWW0 was virtually indistinguishable from that of the type B plasmids (Fig. 7B). The xylA sequences of pWW53, pSVS16, and pDK1 formed another cluster, characterized by 3.0 to 3.5% sequence divergence from the first xylA group and by 0.0 to 0.3% divergence within the group. Plasmids of type C, pSVS11 and pSVS15, carried xylA sequences sharing only 71.9 to 73.7% nucleotide identity to the other xylA sequences, although at the predicted amino acid level the degree of similarity was higher. For example, XylA of pWW0 shared 84% and 83% amino acid residues with XylA of pSVS11 and XylA of pSVS15, respectively. The copies of xylA found in pSVS11 and pSVS15 were 3.5% different from each other (Fig. 7B).

Interestingly, the lower degree of homology of the upper pathway operons of type C plasmids was restricted only to the xylA gene. Nucleotide sequence homologies upstream of xylA, as determined from pSVS10 (type B) and pSVS11 (type C), approached 99% identity with each other and with ntnC (accession AF043544) and about 95% identity with either pWW0 (accession no. D63341), pDK1 (accession no. AF019635), or tmbC (accession no. U41301). Downstream of xylA, the sequences of pSVS10 and pSVS11 were about 95% identical to one another and shared 99 and 96% nucleotide identities with ntnB, respectively. These results suggested that the xylA sequences of the type C plasmids had an origin different from that of the surrounding upper pathway operon sequences.

Interestingly, the upper pathway operon of pWW0 itself seemed to be a mosaic-like structure, too, when compared to the upper pathway operons of type A and B plasmids. Nucleotide sequences of the xylWCMA genes of pWW0 were about 95% identical to the corresponding regions of type A and B pSVS plasmids, of pWW53 and pDK1, and of the ntnWCMA genes. However, downstream of xylA, the pWW0 sequence shared only 73 to 75% nucleotide identity with the other upper pathway operon sequences. Therefore, we propose that the different existing upper pathway operons have undergone several clear DNA recombinations, much more pronounced than those in the meta pathway operons.

DISCUSSION

The present study describes the molecular diversity of plasmids involved in toluene and xylene catabolism via the meta cleavage pathway in Pseudomonas strains (mostly) isolated from oil-contaminated sites near Minsk, Belarus. On all the isolated plasmids, the presence of xyl genes with different degrees of homology to xyl genes of other, previously described TOL plasmids could be demonstrated (1, 4 [and references within], 8, 13, 26, 28, 29, 31, 37, 54, 55, 57, 58). Two main types of gene organization of the xyl meta cleavage and upper pathway operons could be distinguished on the different pSVS plasmids which, however, were similar to those of some TOL plasmids isolated from other geographical regions, i.e., pWW53 in North Wales (26) and pWW102 in The Netherlands (1).

Our data suggest that xyl-type genes occur exclusively in members of the genus Pseudomonas, as was noted by others previously (4). From all contaminated soil samples but also from samples of soil with no record of oil contamination, Pseudomonas strains carrying xyl-type genes grew fastest on plates with m-toluate as the sole carbon source. We did not investigate the potential bias of selecting for particular types of xyl gene organization introduced by plating the bacteria from the soil samples on m-toluate. It can be expected that the conjugative plasmids on which the xyl genes reside will travel to hosts other than Pseudomonas, as was previously suggested by others (23, 42). The reason that other host bacteria carrying TOL plasmids were not retrieved in our study might be that the expression of the xyl genes in those bacteria is poor. A comparison of host and plasmid specificities in our study did not indicate any preferences for host-plasmid combinations, suggesting at least an “unlimited” distribution of the pSVS plasmids among the P. fluorescens subgroup.

A second general notion which can be drawn from our work is that the evolution of xyl-type genes proceeds almost exclusively in association with plasmids. Only in one strain (SV25) and perhaps in two others (SV1 and SV2) could the genes involved in toluene and xylene catabolism be located on the chromosome. The main types of evolutionary mechanisms which might have contributed to the present-day configuration of xyl genes in the pSVS plasmids seem to be the following: (i) recombination of complete xyl operons, (ii) interoperonic recombinations, and (iii) genetic drift within xyl coding sequences.

On all our plasmids, we found only complete copies of the meta cleavage operon and the upper pathway operon. Incomplete copies or physically separated xyl gene units smaller than the known operons were not present among the pSVS plasmids and have not been reported for other naturally occurring TOL plasmids, except for pWW15 (37). One exception is plasmid pNL1 of Sphingomonas strain F199, on which several xyl-homologous genes were detected in rather different configurations (45). Interestingly, most pSVS plasmids carried two meta cleavage pathway operons, which were similar but not identical to one another. This type of configuration also has been detected previously in other TOL plasmids, such as pWW53. The configuration of two meta operon copies is essentially unstable, since the presence of large homologous DNA regions in direct orientation must provoke deletions via legitimate recombination. Indeed, deletion mutants of this type were detected during growth of the SV strains on benzoate (data not shown), as for pWW0 (34), pWW53 (38), pWW15 (37), and pDK1 (31). On the other hand, recombination between the two meta operons would lead to a loss of the upper pathway operon and of xylS and xylR, a result which is clearly disadvantageous for cells growing on hydrocarbons or m-toluate. It is not clear if the presence of two meta operon copies per se will have a selective advantage for cells, such as higher expression of the meta pathway enzymes or formation of heteromultimeric enzymes.

The finding of structurally dissimilar plasmid backbones and different incompatibility groups among the pSVS plasmids but still similar xyl operons argues for independent “movement” of the xyl operons and independent acquisition of the xyl genes by different plasmid vehicles. In several TOL plasmids, such as pWW0, pDK1, pWW53, and pWW15, the xyl operons are enclosed within a large transposable element (27, 37, 47, 50, 51), which might be the main mechanistic element for distributing the xyl genes to other plasmid replicons. However, transposable elements have not yet been described for the pSVS plasmids. The fact that the xyl operons on type C plasmids (pSVS11 and pSVS15) and those on type A and B plasmids were so alike argues for their relatively recent acquisition and/or distribution, even though smaller insertions (such as within the xylUW region in type B plasmids) seem to have taken place since then. Upper and meta cleavage pathway operons are not necessarily distributed or acquired together. This notion became apparent from the high percentage of identity between the ntn genes involved in nitrotoluene degradation in P. putida strain TW3 and the xyl upper pathway operon genes but an apparent lack of the meta pathway operon genes in strain TW3 (24).

On a smaller scale, we found evidence that insertions, deletions, and recombinations occur within xyl operons. This conclusion was obvious from a comparison of upper pathway operons. The xylA gene in plasmids pSVS11 and pSVS15 had clearly lower sequence homology to other known upper pathway operons with respect to its surrounding sequences. This finding indicates insertion of or recombination with an upper pathway operon containing a different xylA gene. Strangely enough, the borders of this aberrant DNA sequence enclose the xylA open reading frame quite exactly. The origin of this xylA sequence is undefined, since it had only moderate sequence identity to xylA sequences of pWW0, pDK1, and pWW53, and to ntnA. We also concluded that the upper pathway operon in pWW0 represents a hybrid structure in comparison to those in pWW53, pDK1, and the pSVS plasmids.

Finally, a small insertion seemed to have occurred in the xylW open reading frame in type A and B plasmids (Fig. 3). Despite our hypothesis that the xyl operons were distributed among the pSVS plasmids relatively recently, the DNA sequences indicated some genetic drift (Fig. 7). Most coherent were plasmids of type B, which was clearly distinguishable from the other types and, therefore, may be endemic for the Minsk area. In contrast, pSVS16 was more similar to pWW53 and thus may have originated from an area in which pWW53 is endemic and been transported to Belarus.

Taken together, the molecular diversity of the xyl genes on the pSVS and other TOL plasmids indicates a dynamic evolution even for such an established pathway as toluene and xylene degradation, involving various mechanisms. Because of such different mechanisms, it becomes practically impossible to trace the evolutionary history of individual xyl operons. Since substantial variability in the plasmid backbones of pSVS plasmids was observed as well, we can conclude that plasmid vectors act as recipients for various kinds of “junk” and useful DNA. Due to permanent oil-related human activities, selective environments are created in which bacteria with various different combinations of xyl operons can proliferate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. Jacoby (Lahey Hitchcock Clinic, Burlington, Mass.) for plasmid pMG18 and A. Boronin (Institute of Biochemistry and Physiology of Microorganisms, Russian Academy of Sciences, Pushchino, Moscow Oblast, Russia) for P. putida strain AC13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aemprapa S, Williams P A. Implications of the xylQ gene of TOL plasmid pWW102 for the evolution of aromatic catabolic pathways. Microbiology. 1998;144:1387–1396. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-5-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Lipman D J. Protein database searches for multiple alignments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5509–5513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assinder S J, De Marco P, Osborne D J, Poh C L, Shaw L E, Winson M K, Williams P A. A comparison of the multiple alleles of xylS carried by TOL plasmids pWW53 and pDK1 and its implications for their evolutionary relationship. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:557–568. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-3-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assinder S J, Williams P A. The TOL plasmids: determinants of the catabolism of toluene and the xylenes. Adv Microb Physiol. 1990;31:1–69. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamin R C, Voss J A, Kunz D A. Nucleotide sequence of xylE from the TOL pDK1 plasmid and structural comparison with isofunctional catechol-2,3-dioxygenase genes from TOL, pWW0, and NAH7. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2724–2728. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2724-2728.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatfield L K, Williams P A. Naturally occurring TOL plasmids in Pseudomonas strains carry either two homologous or two nonhomologous catechol 2,3-oxygenase genes. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:878–885. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.878-885.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckhardt T. A rapid method for the identification of plasmid desoxyribonucleic acid in bacteria. Plasmid. 1978;1:584–588. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(78)90016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filsenstein J. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Interface Package), 3.5p ed. Seattle: University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franklin F C, Bagdasarian M, Bagdasarian M M, Timmis K N. Molecular and functional analysis of the TOL plasmid pWWO from Pseudomonas putida and cloning of genes for the entire regulated aromatic ring meta cleavage pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7458–7462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friello D A, Mylroie J R, Gibson D T, Rogers J E, Chakrabarty A M. XYL, a nonconjugative xylene-degradative plasmid in Pseudomonas Pxy. J Bacteriol. 1976;127:1217–1224. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.3.1217-1224.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furukawa K, Miyazaki T, Tomizuka N. SAL-TOL in vivo recombinant plasmid pKF439. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:1325–1328. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.3.1325-1328.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallegos M T, Williams P A, Ramos J L. Transcriptional control of the multiple catabolic pathways encoded on the TOL plasmid pWW53 of Pseudomonas putida MT53. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5024–5029. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5024-5029.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen J B, Olsen R H. Isolation of large bacterial plasmids and characterization of the P2 incompatibility group plasmids pMG1 and pMG5. J Bacteriol. 1978;135:227–238. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.1.227-238.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harayama S. Codon usage patterns suggest independent evolution of two catabolic operons on toluene-degradative plasmid TOL pWW0 of Pseudomonas putida. J Mol Evol. 1994;38:328–335. doi: 10.1007/BF00163150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harayama S, Lehrbach P R, Timmis K N. Transposon mutagenesis analysis of meta-cleavage pathway operon genes of the TOL plasmid of Pseudomonas putida mt-2. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:251–255. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.1.251-255.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harayama S, Rekik M. Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the meta-cleavage pathway genes of TOL plasmid pWW0 from Pseudomonas putida with other meta-cleavage genes suggests that both single and multiple nucleotide substitutions contribute to enzyme evolution. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;239:81–89. doi: 10.1007/BF00281605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harayama S, Rekik M. The meta-cleavage operon of TOL degradative plasmid pWW0 comprises 13 genes. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;221:113–120. doi: 10.1007/BF00280375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes E J, Bayly R C, Skurray R A. Characterization of a TOL-like plasmid from Alcaligenes eutrophus that controls expression of a chromosomally encoded p-cresol pathway. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:73–78. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.1.73-78.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacoby G A, Jacob A E, Hedges R W. Recombination between plasmids of incompatibility groups P-1 and P-2. J Bacteriol. 1976;127:1278–1285. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.3.1278-1285.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacoby G A, Rogers J E, Jacob A E, Hedges R W. Transposition of Pseudomonas toluene-degrading genes and expression in Escherichia coli. Nature (London) 1978;274:179–180. doi: 10.1038/274179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.James K D, Williams P A. ntn genes determining the early steps in the divergent catabolism of 4-nitrotoluene and toluene in Pseudomonas sp. strain TW3. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2043–2049. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2043-2049.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeenes D J, Williams P A. Excision and integration of degradative pathway genes from TOL plasmid pWW0. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:188–194. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.1.188-194.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keil H, Keil S, Pickup R W, Williams P A. Evolutionary conservation of genes coding for meta-pathway enzymes within TOL plasmids pWW0 and pWW53. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:887–895. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.887-895.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keil H, Keil S, Williams P A. Molecular analysis of regulatory and structural xyl genes of the TOL plasmid pWW53-4. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:1149–1158. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-5-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keil H, Lebens M R, Williams P A. TOL plasmid pWW15 contains two nonhomologous, independently regulated catechol 2,3-oxygenase genes. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:248–255. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.1.248-255.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kivisaar M A, Habicht J K, Heinaru A L. Degradation of phenol and m-toluate in Pseudomonas sp. strain EST1001 and its Pseudomonas putida transconjugants is determined by a multiplasmid system. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5111–5116. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5111-5116.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krieg N J, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunz D A, Chapman P J. Isolation and characterization of spontaneously occurring TOL plasmid mutants of Pseudomonas putida HS1. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:952–964. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.3.952-964.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from micro-organisms. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meulien P, Broda P. Identification of chromosomally integrated TOL DNA in cured derivatives of Pseudomonas putida PAW1. J Bacteriol. 1982;152:911–914. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.2.911-914.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meulien P, Downing R G, Broda P. Excision of the 40kb segment of the TOL plasmid from Pseudomonas putida mt-2 involves direct repeats. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;184:97–101. doi: 10.1007/BF00271202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore E R, Mau M, Arnscheidt A, Böttger E C, Hutson R A, Collins M D, van de Peer Y, de Wachter R, Timmis K N. The determination and comparison of the 16S rRNA gene sequences of species of the genus Pseudomonas (sensu stricto) and estimation of the natural intrageneric relationships. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:478–492. [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Donnell K J, Williams P A. Duplication of both xyl catabolic operons on TOL plasmid pWW15. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2831–2838. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-12-2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osborne D J, Pickup R W, Williams P A. The presence of two complete homologous meta pathway operons on TOL plasmid pWW53. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:2965–2975. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-11-2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pickup R W, Williams P A. Spontaneous deletions in the TOL plasmid pWW20 which give rise to the B3 regulatory mutants of Pseudomonas putida MT20. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:1385–1390. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-7-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plazinski J, Dart P J, Rolfe B G. Plasmid visualization and nif gene location in nitrogen-fixing Azospirillum strains. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:1429–1433. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.3.1429-1433.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramos J L, Marques S, Timmis K N. Transcriptional control of the Pseudomonas TOL plasmid catabolic operons is achieved through an interplay of host factors and plasmid-encoded regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:341–371. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramos-Gonzalez M I, Duque E, Ramos J L. Conjugational transfer of recombinant DNA in cultures and in soils: host range of Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3020–3027. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.10.3020-3027.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ravatn R, Studer S, Springael D, Zehnder A J, van der Meer J R. Chromosomal integration, tandem amplification, and deamplification in Pseudomonas putida F1 of a 105-kilobase genetic element containing the chlorocatechol degradative genes from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4360–4369. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4360-4369.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ravatn R, Zehnder A J B, van der Meer J R. Low-frequency horizontal transfer of an element containing the chlorocatechol degradation genes from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 to Pseudomonas putida F1 and to indigenous bacteria in laboratory-scale activated-sludge microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2126–2132. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.6.2126-2132.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romine M F, Stillwell L C, Wong K K, Thurston S J, Sisk E C, Sensen C, Gaasterland T, Fredrickson J K, Saffer J D. Complete sequence of a 184-kilobase catabolic plasmid from Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1585–1602. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1585-1602.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaw L E, Williams P A. Physical and functional mapping of two cointegrate plasmids derived from RP4 and TOL plasmid pDK1. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:2463–2474. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-9-2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sinclair M I, Maxwell P C, Lyon B R, Holloway B W. Chromosomal location of TOL plasmid DNA in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1302–1308. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1302-1308.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tchelet R, Meckenstock R, Steinle P, van der Meer J R. Population dynamics of an introduced bacterium degrading chlorinated benzenes in a soil column and in sewage sludge. Biodegradation. 1999;10:113–125. doi: 10.1023/a:1008368006917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsuda M, Iino T. Genetic analysis of a transposon carrying toluene degrading genes on a TOL plasmid pWW0. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;210:270–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00325693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsuda M, Iino T. Identification and characterization of Tn4653, a transposon covering the toluene transposon Tn4651 on TOL plasmid pWW0. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;213:72–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00333400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Versalovic J, Schneider M, de Bruijn F J, Lupski J R. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction. Methods Mol Cell Biol. 1994;5:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams P A, Assinder S J, De Marco P, O'Donnell K J, Poh C L, Shaw L E, Winson M K. Catabolic gene duplications in TOL plasmids. In: Galli E, Silver S, Witholt B, editors. Pseudomonas: molecular biology and biotechnology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 341–353. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams P A, Murray K. Metabolism of benzoate and the methylbenzoates by Pseudomonas putida (arvilla) mt-2: evidence for the existence of a TOL plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1974;120:416–423. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.1.416-423.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams P A, Sayers J R. The evolution of pathways for aromatic hydrocarbon oxidation in Pseudomonas. Biodegradation. 1994;5:195–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00696460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams P A, Taylor S D, Gibb L E. Loss of the toluene-xylene catabolic genes of TOL plasmid pWW0 during growth of Pseudomonas putida on benzoate is due to a selective growth advantage of ‘cured’ segregants. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:2039–2048. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-7-2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams P A, Worsey M J. Ubiquity of plasmids in coding for toluene and xylene metabolism in soil bacteria: evidence for the existence of new TOL plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1976;125:818–828. doi: 10.1128/jb.125.3.818-828.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yano K, Nishi T. pKJ1, a naturally occurring conjugative plasmid coding for toluene degradation and resistance to streptomycin and sulfonamides. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:552–560. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.552-560.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]